Electron vs. Ion Spectroscopy: A Comparative Guide to Surface Analysis Techniques for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of electron and ion spectroscopy techniques for surface analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences.

Electron vs. Ion Spectroscopy: A Comparative Guide to Surface Analysis Techniques for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of electron and ion spectroscopy techniques for surface analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences. It covers the foundational principles of key methods like XPS, AES, and SIMS, explores their specific applications in characterizing biomaterials and nanoparticles, addresses common troubleshooting and data interpretation challenges, and delivers a direct, validated comparison of their analytical capabilities. The goal is to offer a decisive guide for selecting the optimal surface analysis technique to solve complex problems in biomedical research and development.

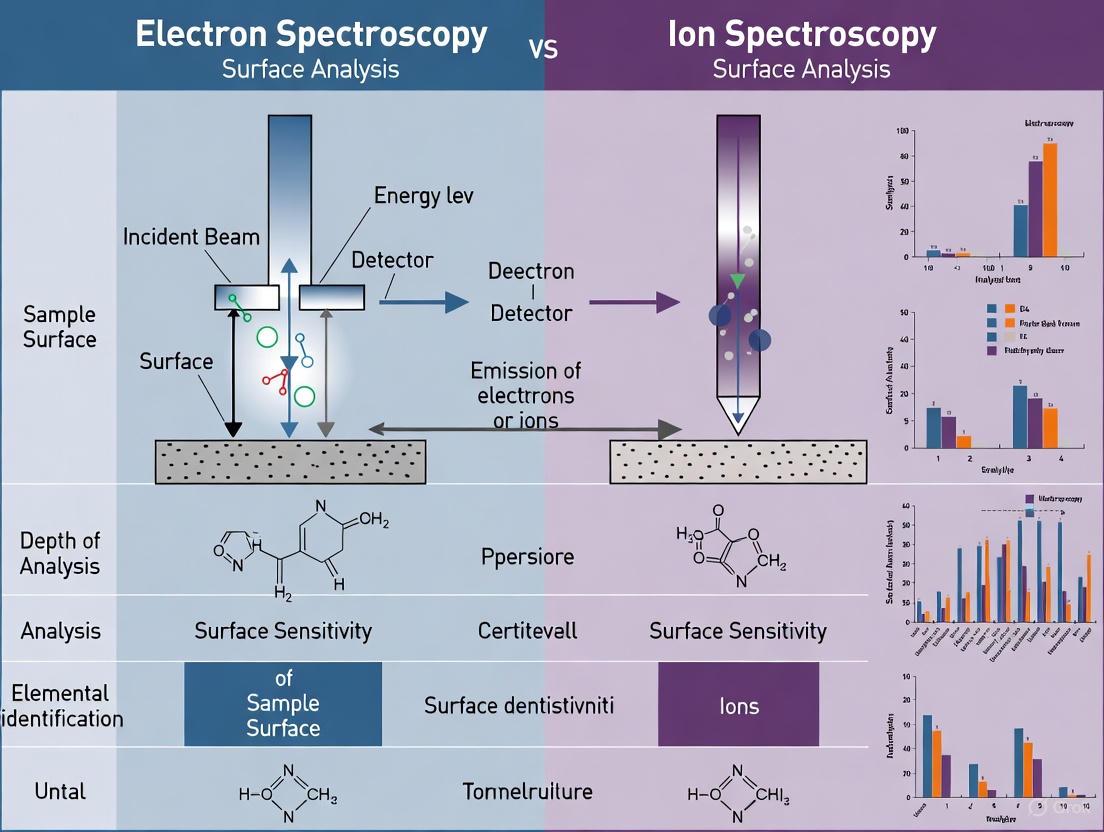

Core Principles: How Electron and Ion Beams Interrogate Surface Chemistry

Surface analysis is a critical discipline in analytical science, providing insights into the outermost layers of materials where many chemical and physical processes originate. For researchers in fields ranging from drug development to nanotechnology, understanding the composition and chemistry of surfaces is essential. The techniques designed for this purpose primarily use either electron or ion probes to investigate surface characteristics. This guide provides an objective comparison of the major surface analysis techniques, with a specific focus on the divide between electron and ion spectroscopy methods. We will explore the fundamental principles, analytical capabilities, and practical applications of these techniques, supported by current experimental data and protocols to inform your research decisions.

The three most widely applied surface analysis techniques are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) [1]. XPS and AES fall under the category of electron spectroscopy, while SIMS represents ion spectroscopy. Each technique offers unique advantages and suffers from specific limitations, making them complementary rather than competitive for comprehensive surface characterization.

Fundamental Principles: Electron vs. Ion Spectroscopy

Electron Spectroscopy Techniques

Electron spectroscopy techniques utilize incident particles (X-rays or electrons) to eject electrons from the sample surface, which are then analyzed to determine surface composition and chemical state.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), operates on the photoelectric effect. When a material is irradiated with X-rays, electrons are ejected from core levels. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is measured, allowing calculation of their binding energy, which is element-specific and sensitive to chemical environment [1]. XPS provides excellent quantitative information and chemical state identification, making it the most commonly used surface analysis technique [1].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) uses a focused electron beam to create core holes in atoms. The subsequent relaxation process leads to emission of Auger electrons, whose energies are characteristic of the elements present [1]. AES typically offers superior spatial resolution compared to XPS (can be below 10 nm) and can in some cases provide better chemical state information, particularly for carbon on metal surfaces [1].

Ion Spectroscopy Techniques

Ion spectroscopy techniques use energetic primary ions to sputter material from the sample surface, then analyze the ejected particles.

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) bombards the surface with primary ions (typically O₂⁺, Cs⁺, Ga⁺, or Bi₃⁺), causing the ejection (sputtering) of neutral atoms and molecules, as well as positively and negatively charged secondary ions. These secondary ions are then analyzed by mass spectrometry [1]. SIMS offers exceptional sensitivity (parts-per-billion to parts-per-million range), the ability to detect all elements including hydrogen and isotopes, and high spatial resolution imaging capabilities.

A variation of SIMS, sputtered neutral mass spectrometry (SNMS), measures the mass spectrum of the neutral species emitted, which are ionized after leaving the surface [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Major Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Primary Probe | Detected Signal | Information Obtained | Vacuum Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS | X-rays | Photoelectrons | Elemental composition, chemical state, oxidation state | Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) |

| AES | Electrons | Auger electrons | Elemental composition, chemical state (for some elements) | UHV |

| SIMS | Ions | Secondary ions | Elemental and isotopic composition, molecular structure, trace impurities | UHV |

Technical Comparison of Capabilities

Detection Capabilities and Limitations

Each surface analysis technique has distinct strengths and limitations in terms of what it can detect and quantify.

XPS does not directly detect hydrogen (H) or helium (He), though the effect of hydrogen on other elements can sometimes be observed indirectly [1]. It provides relatively straightforward quantification with detection limits typically around 0.1-1 at%. Modern XPS instruments achieve spatial resolution in the 1-10 μm range, with synchrotron-based systems reaching approximately 150 nm [1].

AES similarly cannot directly detect H or He [1]. Its major advantage lies in superior spatial resolution, as electron beams can be focused to small areas, enabling nanoscale analysis. AES detection limits are similar to XPS but with better spatial resolution for mapping applications.

SIMS excels in detection capabilities, able to identify all elements including hydrogen and distinguish between isotopes [1]. This isotopic discrimination is particularly useful when an oxygen beam is used for analysis, where oxygen from the surface can be distinguished from the oxygen in the beam [1]. SIMS offers exceptional sensitivity with detection limits in the parts-per-billion to parts-per-million range, though quantification is more challenging than for XPS.

Spectral Complexity and Interpretation

The complexity of data interpretation varies significantly between techniques.

XPS spectra are generally the simplest to interpret, with well-resolved peaks corresponding to specific elemental transitions and chemical states [1]. This relative simplicity contributes to its widespread use and makes quantification more straightforward.

AES spectra can be more complex due to the involvement of three energy levels in the Auger process, but still generally provide interpretable elemental and some chemical information.

SIMS produces the most complex spectra, as large molecular fragments from the material are formed in addition to elemental ions [1]. While this provides rich molecular information, it complicates interpretation and quantification. The complexity is particularly pronounced when analyzing organic materials or complex molecular structures.

Table 2: Analytical Performance Comparison of Surface Analysis Techniques

| Parameter | XPS | AES | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elements Detected | All except H and He | All except H and He | All elements, including H and He |

| Detection Limit | 0.1-1 at% | 0.1-1 at% | ppb-ppm range |

| Spatial Resolution | 1-10 μm (150 nm with synchrotron) | <10 nm | 50-100 nm (with Ga⁺ LMIG) |

| Chemical Information | Excellent (oxidation states, functional groups) | Good for some elements | Molecular structure, fragments |

| Quantification | Excellent (relative accuracy 5-10%) | Good (relative accuracy 10-15%) | Difficult (requires standards) |

| Depth Resolution | 2-5 nm (angle-resolved) | 2-5 nm | 1-3 nm (static SIMS) |

| Isotopic Detection | No | No | Yes |

Recent Technological Advances

Instrumental Developments

Surface analysis techniques continue to evolve with significant improvements in capability and accessibility.

XPS has seen remarkable advancements, including Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES), which uses higher energy X-rays (from silver, chromium, or gallium sources instead of conventional aluminum or magnesium sources) to probe deeper interfaces and reduce surface contamination effects [1]. Near Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) represents another major advancement, allowing chemical analysis of surfaces in reactive environments rather than requiring ultra-high vacuum [1]. This enables studies of corrosion, microorganisms, and catalytic processes under more realistic conditions.

AES and SIMS instruments have achieved higher spatial resolutions through improved focusing of electron and ion beams [1]. While the number of manufacturers of commercial AES and SIMS instruments has decreased over recent decades, there remains healthy competition in the XPS instrument market, driving continued innovation [1].

Miniaturization and Specialized Applications

The field has witnessed significant progress in miniaturization, similar to trends in related analytical techniques. While not directly applied to XPS, AES, or SIMS in the search results, developments in Drift Tube Ion Mobility Spectrometry (DT-IMS) demonstrate the broader trend toward portability and field deployment through miniaturization, improved ion shutters, drift tubes, and integrated chip-based pre-separation methods [2].

In pharmaceutical and forensic applications, novel approaches like Extractive-Liquid Sampling Electron Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (E-LEI-MS) combine ambient sampling with the high identification power of electron ionization, enabling rapid analysis of drugs and contaminants with minimal sample preparation [3]. This technique has been successfully applied to detect active pharmaceutical ingredients and excipients in various drug formulations, as well as benzodiazepines in simulated forensic scenarios involving adulterated cocktails [3].

Experimental Protocols

Representative Workflow: Surface Analysis of Pharmaceutical Compounds

The following dot code provides a workflow for surface analysis of pharmaceutical compounds using E-LEI-MS, based on published methodologies [3]:

Figure 1: Workflow for surface analysis of pharmaceutical compounds using E-LEI-MS.

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Analysis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) using E-LEI-MS [3]

- Sample Preparation: Twenty commercially available pharmaceuticals containing 16 different APIs were analyzed without any pre-treatment. Samples included tablets, lozenges, and gels.

- Instrument Configuration: E-LEI-MS system coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an EI source. The system includes a solvent-release mechanism with a syringe pump and a sampling tip consisting of two coaxial tubes.

- Solvent Delivery: Acetonitrile was pumped through the outer tubing onto the sample surface at a controlled rate.

- Liquid Extraction: Analytes were directly extracted from the sample surface wetted by solvent droplets.

- Vacuum Aspiration: The liquid extract was immediately aspirated by the high vacuum of the EI source through the inner capillary.

- Vaporization and Ionization: The extract passed through a vaporization microchannel (VMC) heated to 300°C, then into the EI source where ionization occurred at 70 eV.

- Mass Analysis: Ions were analyzed by the triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in full scan mode (m/z 50-500).

- Data Analysis: Spectra were compared against commercial EI spectral libraries for compound identification.

Protocol 2: Analysis of Benzodiazepines in Fortified Cocktails (Simulating DFSA Scenarios) [3]

- Sample Preparation: Six benzodiazepines (clobazam, clonazepam, diazepam, flunitrazepam, lorazepam, and oxazepam) were used to fortify a gin tonic cocktail at concentrations of 20 mg/L and 100 mg/L.

- Spot Preparation: 20 μL of adulterated cocktails were spotted on a watch glass surface and analyzed as dried spots.

- Analysis Conditions: Similar to Protocol 1, but using high-resolution accurate-mass quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-ToF) mass spectrometry for confident compound identification.

- Identification Criteria: Accurate mass measurement with mass error < 5 ppm and isotopic pattern matching.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (HPLC grade) | Extraction solvent | Dissolving and extracting analytes from sample surfaces in E-LEI-MS [3] |

| Standard solutions | Calibration and quantification | Preparing reference standards for benzodiazepines at concentrations of 20, 100, and 1000 mg/L [3] |

| Silica capillaries | Liquid transport | Inner capillary (40-50 μm I.D.) for transporting liquid extract to MS [3] |

| Peek tubing | Solvent delivery | Outer tubing (450 μm I.D.) for delivering solvent to sample surface [3] |

| Vaporization microchannel (VMC) | Sample vaporization | Facilitating vaporization and transport of liquid extract into ion source [3] |

| Syringe pump | Solvent delivery control | Precisely controlling solvent flow rate (typically 1-10 μL/min) [3] |

| Manual microfluid valve | Flow control | Regulating liquid flow into the mass spectrometer [3] |

Comparative Performance in Practical Applications

Application-Specific Considerations

The choice of surface analysis technique depends heavily on the specific application requirements:

For chemical state analysis and quantitative composition, XPS is generally preferred due to its straightforward interpretation and reliable quantification [1]. Applications include surface contamination analysis, coating characterization, and failure analysis.

For high-spatial resolution elemental mapping, AES provides superior performance with its finely focused electron beam [1]. This makes it valuable for semiconductor device analysis, grain boundary studies, and microelectronic failure analysis.

For trace detection and molecular identification, SIMS offers unparalleled sensitivity and molecular information [1]. Applications include dopant profiling in semiconductors, organic contaminant identification, and biological surface characterization.

For atmospheric or semi-atmospheric pressure studies, NAP-XPS enables investigation of surfaces under realistic environmental conditions, unlike traditional UHV techniques [1]. This is particularly valuable for catalytic studies, corrosion science, and biological surface analysis.

Data Analysis Challenges and Solutions

Data interpretation remains a significant challenge across all surface analysis techniques, particularly for non-experts.

In XPS, peak fitting is one of the most commonly used procedures, yet approximately 40% of papers show incorrect fitting of peaks [1]. Common errors include using symmetrical peaks for asymmetrical metal peaks, not applying appropriate constraints for doublet relative intensities and separations, and incorrectly setting full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) parameters [1]. For example, the Ti 2p₁/₂ FWHM is typically about 20% larger than the FWHM of the Ti 2p₃/₂ peak, a detail often overlooked in improper peak fitting [1].

SIMS data interpretation is challenged by spectral complexity, with numerous peaks corresponding to molecular fragments in addition to elemental ions. Multivariate analysis techniques are often required for comprehensive data interpretation.

Software solutions continue to evolve, but fully automated analysis and interpretation remain problematic. Manufacturers' claims of completely automated analysis and reporting often fall short in practice, frequently generating reports with errors [1]. Organizations such as ISO continue to work on methods for improving data analysis standardization.

Surface analysis techniques provide indispensable tools for characterizing the outermost layers of materials, with XPS, AES, and SIMS representing the three most widely applied methods. Each technique offers unique capabilities: XPS excels in quantitative analysis and chemical state determination; AES provides superior spatial resolution for elemental mapping; while SIMS offers exceptional sensitivity and isotopic discrimination.

The choice between electron spectroscopy (XPS, AES) and ion spectroscopy (SIMS) depends on specific analytical requirements including detection sensitivity, spatial resolution, need for chemical state information, and whether isotopic or molecular information is required. Recent advancements such as HAXPES, NAP-XPS, and hybrid techniques like E-LEI-MS continue to expand application possibilities across pharmaceutical, forensic, materials, and biological research.

As these techniques evolve, challenges remain in data interpretation, particularly in peak fitting for XPS and spectral complexity in SIMS. Ongoing developments in instrumentation, data processing software, and standardization efforts promise to address these challenges, further enhancing the value of surface analysis across scientific disciplines.

Surface analysis is critical for understanding material properties in fields ranging from drug development to nanotechnology. Among the most prominent techniques are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), both belonging to the electron spectroscopy family. These techniques probe the topmost 1-10 nanometers of a material, providing invaluable information about elemental composition and chemical state [4] [5]. While they share the common principle of analyzing ejected electrons to characterize surfaces, their excitation mechanisms and the specific information they deliver differ significantly. This guide provides a detailed comparison of XPS and AES, outlining their fundamental mechanisms, experimental protocols, and appropriate applications within the broader context of surface science research.

The fundamental physical process for both techniques begins with the creation of a core-hole in an atom. Where they differ is in the initial excitation mechanism and the subsequent relaxation process that produces the detected electron. XPS relies on the photoelectric effect, where an incident X-ray photon is absorbed, directly ejecting a photoelectron. In contrast, AES uses a focusedelectron beam to create the initial core hole, and the detected signal comes from a secondary electron emitted during the relaxation process that follows [1]. This fundamental distinction in excitation and emission mechanisms dictates their relative strengths, weaknesses, and ideal application areas.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Theoretical Background

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Mechanism

XPS, also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), operates on the principle of the photoelectric effect. When a material is irradiated with X-rays of known energy, photons are absorbed by atoms, ejecting core-level electrons known as photoelectrons. The kinetic energy (KE) of these ejected photoelectrons is measured by the instrument, and the electron binding energy (BE) is calculated using the fundamental equation [6] [5]:

Binding Energy (BE) = Photon Energy (hν) – Kinetic Energy (KE) – Work Function (φ) [5]

The binding energy is a characteristic value for each element and electronic shell, enabling qualitative analysis. Furthermore, because the binding energy is sensitive to the chemical environment of the atom, XPS provides chemical state information. For example, the binding energy for carbon in a C-C bond is different from that in a C-O bond [4] [5]. The average depth of analysis for XPS is very shallow, typically less than 10 nm, making it exceptionally surface-sensitive [4]. Its detection limits are generally in the parts per thousand range, though parts per million (ppm) can be achieved with long collection times and surface concentration [5].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) Mechanism

The AES process is a three-step phenomenon initiated by a high-energy electron beam (typically 3-20 keV). First, the incident electron collides with an atom, ejecting a core-level electron and creating a core-hole. Second, an electron from a higher energy level fills this vacancy. Third, the energy released from this relaxation is transferred to another electron, which is then ejected from the atom; this ejected electron is called an Auger electron (named after Pierre Auger) [1]. The kinetic energy of the Auger electron is characteristic of the element from which it was emitted but is generally independent of the incident beam energy.

The kinetic energy of an Auger electron is determined by the energy levels of the three orbitals involved in the process (the initial core-hole, the filling electron, and the ejected electron). For a transition involving the K, L₁, and L₂₃ levels, the kinetic energy is approximately EKinetic ≈ EK – EL₁ – EL₂₃, where E denotes the binding energy of the respective levels [7]. Unlike XPS, the Auger process does not directly provide the same detailed chemical state information, though chemical shifts in Auger peaks can still occur and are sometimes used in specialized Auger parameter studies for additional chemical information.

Conceptual Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms and comparative workflows of XPS and AES analysis.

Figure 1: Comparative mechanisms and workflows of XPS and AES surface analysis techniques.

Comparative Technical Specifications

For researchers selecting the appropriate technique, a direct comparison of key technical parameters is essential. The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of XPS and AES.

Table 1: Technical comparison of XPS and AES

| Parameter | XPS (ESCA) | AES |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | X-ray photons (e.g., Al Kα, Mg Kα) [4] | High-energy electron beam (3-20 keV) [1] |

| Detected Particle | Photoelectrons [5] | Auger electrons [1] |

| Primary Information | Elemental identity, chemical state, and oxidation state [4] [5] | Elemental identity and lateral distribution [1] |

| Spatial Resolution | ~10 µm (lab source); can be < 150 nm with synchrotrons [1] | Higher than XPS; can be focused to nanometers [1] |

| Detection Limits | ~0.1-1.0 at% (1000 ppm); can reach ppm with long acquisition [5] | Similar to XPS, but highly dependent on element and matrix [7] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Excellent (90-95% for major peaks) with relative sensitivity factors [5] | Good, but can be more complex than XPS due to background [7] |

| Chemical State Sensitivity | Excellent, a key strength of the technique [4] [5] | Moderate; chemical shifts are smaller and more complex to interpret [1] |

| Sample Damage | Generally low for most solids; can degrade some polymers [5] | Higher potential for damage due to focused electron beam [1] |

| Vacuum Requirement | High vacuum (HV) or ultra-high vacuum (UHV) [5] | Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) is essential [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard XPS Analysis Protocol

1. Sample Preparation: Samples must be solid and compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV ~10⁻⁹ mbar). Conducting samples can be mounted directly, while insulating samples may require charge neutralization with a low-energy electron flood gun. Sample size is variable, with modern instruments accepting samples from millimeters to several centimeters in size [5].

2. Instrument Calibration and Setup: The energy scale of the spectrometer is calibrated using standard reference samples like clean gold or copper foil. The analyst selects an appropriate X-ray source (typically monochromatic Al Kα at 1486.6 eV for high resolution), and the analyzer pass energy is set to achieve the desired balance between energy resolution and signal-to-noise ratio [7] [6].

3. Data Acquisition:

- Survey Scan: A wide energy range scan (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) is first acquired to identify all elements present on the surface. Acquisition time is typically 1-20 minutes [5].

- High-Resolution Regional Scans: Narrow energy windows covering the core-level peaks of identified elements are scanned with higher energy resolution to determine chemical states. Acquisition times range from 1-15 minutes per region, and multiple sweeps are often used to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [5].

4. Data Processing and Quantification:

- Background Subtraction: A suitable algorithm (e.g., Shirley or Tougaard background) is applied to remove the inelastically scattered electron background [7] [8].

- Peak Fitting: High-resolution spectra are deconvoluted using curve-fitting with appropriate peak shapes (e.g., mixed Gaussian-Lorentzian functions) and constraints based on known chemical states and spin-orbit splitting [1] [6].

- Quantification: The area under each photoelectron peak is calculated and divided by an element-specific relative sensitivity factor (RSF) to determine atomic concentrations [7] [5]. The formula for the atomic concentration of element A is: at% A = (I_A / RSF_A) / Σ(I_n / RSF_n), where I is the measured peak area.

Standard AES Analysis Protocol

1. Sample Preparation: Similar to XPS, samples must be UHV-compatible. Due to the use of an electron beam, sample charging of insulators can be more challenging to manage than in XPS.

2. Instrument Setup: The electron gun is configured with a specific beam energy (e.g., 10 keV) and current. The electron optic column is aligned to achieve the smallest possible spot size for high-spatial-resolution analysis. The analyzer is set to a constant pass energy for consistent resolution [7].

3. Data Acquisition: AES data can be acquired in two primary modes:

- Direct Spectrum Mode (N(E) vs. E): This mode provides the true electron energy distribution and is required for accurate quantitative analysis. Peak areas are integrated after background removal [7].

- Differential Spectrum Mode (dN(E)/dE vs. E): This was the traditional, more rapid mode where the peak-to-peak height in the differentiated spectrum is used as a semi-quantitative measure of elemental concentration. However, this method is strongly influenced by chemical state changes and peak shape, making it less reliable for quantification than the direct spectrum method [7].

4. Data Processing and Quantification:

- For quantification from direct spectra, the background is carefully removed, often using methods like the Tougaard algorithm [7].

- The peak area for a specific Auger transition is measured. Quantitative analysis involves complex calculations or sensitivity factors that account for the ionization cross-section, backscattering factor, and inelastic mean free path. The total intensity from all transitions originating from an ionized shell often provides the best correlation with theory [7].

Depth Profiling Methodology

Both techniques can be used for depth profiling by combining analysis with sequential material removal via sputtering by an ion beam (e.g., Ar⁺) [9] [8].

1. Protocol: A cycle consists of (1) acquiring spectra from the fresh surface, (2) etching the surface for a fixed time using a rastered ion beam, and (3) repeating until the desired depth is reached [9].

2. Optimization Considerations:

- Ion Beam Parameters: Lower ion energies and larger primary ion species (e.g., Xe⁺) improve depth resolution by reducing atomic mixing [9].

- Incidence Angle: Shallow (grazing) angles improve depth resolution by reducing the ion penetration depth [9].

- Crater Quality: The sputtered crater must be large and flat, with the analysis area well-centered to avoid crater wall effects [9].

- Sample Rotation: Azimuthal rotation during sputtering significantly reduces induced roughness, leading to higher resolution profiles, especially for polycrystalline materials [9].

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for electron spectroscopy

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Monochromatic Al Kα X-ray Source | Standard laboratory X-ray source for XPS (1486.6 eV); provides narrow linewidth for high-resolution chemical state analysis [6] [5]. |

| High-Energy Electron Gun | Source of primary electrons for AES excitation; can be focused to a fine probe for high-spatial-resolution mapping [1]. |

| Argon Gas Cluster Ion Source | Advanced sputtering source for depth profiling organic and polymeric materials; minimizes damage compared to monatomic ions [8] [10]. |

| Charge Neutralization Flood Gun | Source of low-energy electrons and ions to compensate for surface charging on insulating samples during analysis, essential for accurate data [9] [5]. |

| Certified Standard Reference Samples | Samples with known composition (e.g., Au, Cu, Si) for quantitative calibration of the spectrometer's intensity/energy response function [7]. |

| High-Purity Sputter Gases (Ar, Xe) | Inert gases for ion guns used in sample cleaning and depth profiling; high purity is critical to avoid surface contamination [9]. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Quantitative Analysis and Sensitivity Factors

The foundation of quantification in both XPS and AES is the scaling of measured peak intensities with element-specific relative sensitivity factors (RSFs). In XPS, the process is relatively straightforward: the integrated area of a photoelectron peak is divided by its RSF, and the results are normalized to 100% to obtain atomic percentages [5]. These RSFs account for the photoionization cross-section (typically from Scofield's calculations) and the energy-dependent transmission of the electron analyzer [7].

Quantification in AES is inherently more complex. The Auger current depends not only on the ionization cross-section but also on the backscattering factor (the contribution of incident electrons that are backscattered and cause additional ionizations) and complex core-hole relaxation dynamics, including Coster-Kronig transitions [7]. Studies show that the best quantitative correlations are achieved by considering the total intensity for all Auger transitions originating from an ionized shell, using the Casnati et al. ionization cross-section and specific inelastic mean free path calculations [7].

Spectral Features and Chemical State Information

XPS: Chemical state identification is a principal strength. A shift in the binding energy of a photoelectron peak indicates a change in the chemical environment of the atom. For example, the Si 2p peak will have a distinct, higher binding energy in SiO₂ compared to pure Si. Peak fitting of high-resolution spectra is used to deconvolve these different chemical states [1] [6]. A common challenge, however, is that in about 40% of published papers, peak fitting is performed incorrectly, for instance, by using symmetrical peaks for inherently asymmetrical metallic peaks or misapplying constraints on doublet separations and intensities [1].

AES: While the primary Auger peak energy is used for elemental identification, the Auger line shape can also be sensitive to chemical environment. For instance, the carbon KLL spectrum is markedly different between graphite, carbide, and hydrocarbon states. However, interpreting these shape changes is often less intuitive than interpreting XPS chemical shifts [1].

Current Trends and Advancements

The field of electron spectroscopy is continuously evolving. Key trends shaping its future include:

- Democratization and Automation: Instrumentation is becoming more user-friendly and automated, extending access beyond specialist operators. Intelligent software is being developed to improve data reproducibility and integrity, though fully automated interpretation remains a challenge [1] [10].

- Advanced Light Sources: The use of Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES) with laboratory Cr or Ga sources or synchrotrons allows probing of deeper bulk regions and interfaces (tens of nanometers), reducing surface sensitivity issues [1] [6].

- Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS): This advancement enables the study of surfaces in the presence of gases or vapors, opening new frontiers in catalysis, environmental science, and electrochemistry [1].

- Improved Sputtering: The development of gas cluster ion beams (e.g., Arₙ⁺, n>1000) has revolutionized depth profiling of organic materials, polymers, and pharmaceuticals by significantly reducing the ion beam damage associated with traditional monatomic ions [9] [8] [10].

XPS and AES are powerful, complementary techniques in the surface scientist's toolkit. The choice between them depends heavily on the specific analytical question.

- Choose XPS when the primary requirements are excellent chemical state information, straightforward quantitative analysis of homogeneous surfaces, and minimal risk of beam-induced damage for sensitive materials. It is the more universally applied technique for general surface chemical characterization.

- Choose AES when the analysis demands very high lateral spatial resolution (down to the nanometer scale) for mapping elemental distributions on the micro- to nano-scale, and when the sample is conductive and robust enough to withstand electron beam exposure.

Within the broader thesis comparing electron and ion spectroscopy techniques, this guide establishes that electron-based spectroscopies like XPS and AES excel in providing direct information on elemental composition and chemical bonding from the outermost surface layers. Their integration with ion beam sputtering for depth profiling creates a powerful, hybrid approach for three-dimensional material characterization, bridging the information gap between pure electron and pure ion spectroscopy methods.

Surface compositional analysis is critical in fields ranging from materials science to pharmaceutical development, where understanding the outermost layers of a material is essential for predicting its performance and stability. Ion spectroscopy techniques, particularly Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) and Sputtered Neutral Mass Spectrometry (SNMS), represent two powerful approaches for obtaining detailed chemical information from surfaces. These techniques operate on the principle of surface erosion by ion beam sputtering but differ fundamentally in the species they detect and their resulting analytical capabilities. Within the broader context of surface analysis techniques, which include electron spectroscopies like XPS and AES, SIMS and SNMS offer unique advantages for elemental and molecular characterization with excellent depth resolution and sensitivity. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of SIMS and SNMS methodologies, presenting their fundamental mechanisms, comparative performance data, and practical experimental considerations to assist researchers in selecting the appropriate technique for their specific analytical challenges.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS)

The SIMS technique operates through a focused primary ion beam (typically Cs+, O2+, or Ga+) that bombards the sample surface, causing the ejection (sputtering) of atoms and molecules from the uppermost layers. A critical fraction of these sputtered particles become ionized (forming secondary ions) and are subsequently extracted into a mass analyzer for identification. The process involves multiple sequential steps: primary ion impact, energy transfer through collision cascades, sputtering of material, ionization of a fraction of the sputtered particles, and finally mass analysis of the secondary ions. The detected secondary ion intensities provide information about the elemental, isotopic, and molecular composition of the analyzed surface volume.

SIMS is particularly renowned for its exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting elements present at trace levels (parts-per-billion to parts-per-million range). However, this sensitivity comes with a significant analytical challenge known as the matrix effect, where the ionization probability of sputtered particles—and thus the measured signal intensity—depends strongly on the chemical environment of the element within the sample. This effect complicates quantitative analysis as relative sensitivity factors can vary by orders of magnitude between different matrices, requiring careful calibration with matrix-matched standards for accurate quantification [11].

Sputtered Neutral Mass Spectrometry (SNMS)

SNMS was developed to overcome the matrix effects that plague quantitative analysis in SIMS. While the initial sputtering process in SNMS is similar to SIMS, the fundamental difference lies in the detection scheme. In SNMS, the majority sputtered neutral atoms and molecules (which constitute over 99% of the total sputtered flux) are selectively ionized after leaving the sample surface using a dedicated post-ionization mechanism. This physical separation of the sputtering and ionization processes effectively decouples the emission and ionization events, dramatically reducing matrix dependence [12] [13].

Various post-ionization methods have been implemented in SNMS instruments. The electron gas SNMS approach utilizes a dense, confined electron gas maintained at low pressures (∼10⁻³ Pa) through which the sputtered neutrals pass and undergo electron impact ionization. Alternative implementations employ electron beams or high-power lasers for post-ionization. The use of Cs+ primary ions in SNMS has been shown to improve depth resolution compared to Ar+ bombardment without altering the relative sensitivity factors used for quantification, making it advantageous for depth profiling of layered structures [12]. Additionally, SNMS spectra are notably cleaner than SIMS spectra as they contain "no significant amount of molecules," reducing spectral interferences [12].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Technical Comparison of SIMS and SNMS

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics and comparative performance of SIMS and SNMS

| Parameter | SIMS | SNMS |

|---|---|---|

| Detected Species | Secondary ions | Post-ionized sputtered neutrals |

| Ionization Process | Occurs during sputtering | Post-ionization after sputtering |

| Matrix Effects | Strong (major limitation) | Minimal (key advantage) |

| Useful Yield | ~0.1-10% (varies greatly with matrix) | Can approach >50% for electron gas SNMS |

| Quantification | Requires matrix-matched standards | Direct quantification with relative sensitivity factors |

| Molecular Information | Yes (detects molecular ions) | Limited (primarily atomic species) |

| Detection Limits | Excellent (ppb-ppm range) | Good (ppm range typically) |

| Depth Resolution | Good, but can be degraded by atomic mixing | Superior, improved with Cs+ primary ions and sample biasing [12] |

| Dynamic Range | Good | High (improved in combined instruments) [13] |

Quantitative Analysis Capabilities

The comparative studies between MCs+-SIMS and electron-beam SNMS reveal critical differences in their quantitative capabilities. In SNMS, the relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) show minimal matrix dependence, enabling more straightforward quantification of heterostructure depth profiles. In contrast, MCs+-SIMS demonstrates matrix-dependent RSFs that complicate quantitative analysis, despite its improved depth resolution compared to conventional SIMS modes [12]. The fundamental reason for this difference lies in the ionization mechanism: since SNMS detects neutrals that are ionized in a controlled environment after sputtering, the ionization probability becomes largely independent of the sample matrix.

For depth profiling applications, SNMS offers advantages in depth resolution through technical implementations such as biasing the sample against the primary ion beam, which reduces the net energy of primary ions and creates a more grazing impact angle [12]. Combined SNMS/SIMS instruments have been developed to leverage the strengths of both techniques, providing high dynamic range and improved detection limits for comprehensive trace and depth profile analysis [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SIMS Experimental Protocol for Surface Analysis

Instrument Setup and Parameters: Time-of-Flight (ToF) SIMS instruments are widely used for surface analysis due to their high mass resolution and sensitivity. The experimental protocol begins with sample preparation, which typically involves mounting the specimen on a conductive substrate to mitigate charging effects during analysis. For insulating samples, electron flood guns are employed for charge compensation. The primary ion source (commonly liquid metal ion guns like Ga+ or Bi3+ for high spatial resolution, or Cs+ for enhanced negative secondary ion yield) is tuned to optimal parameters, with typical primary ion energies ranging from 10-30 keV. The mass spectrometer is mass-calibrated using known reference peaks prior to analysis [14] [15].

Data Acquisition and Analysis: Surface spectra are acquired in static SIMS mode using a low primary ion dose (<10¹³ ions/cm²) to ensure the analysis remains surface-specific. For depth profiling, dynamic SIMS employs higher primary ion doses with continuous sputtering to progressively reveal subsurface information. The secondary ions are extracted into the time-of-flight analyzer, separated by their mass-to-charge ratios, and detected using microchannel plate detectors. Data interpretation involves identifying elemental and molecular peaks through exact mass assignment, often supplemented by multivariate analysis techniques for complex organic and biological samples [14].

SNMS Experimental Protocol for Quantitative Depth Profiling

Instrument Configuration: SNMS instrumentation incorporates additional components compared to SIMS, primarily the post-ionization source situated between the sample and mass analyzer. In electron gas SNMS systems, a confined electron gas is maintained in a Wien filter configuration, where the sputtered neutrals pass through and undergo electron impact ionization. The electron beam SNMS variant employs a focused electron beam directed across the path of the sputtered neutral flux. Primary ion sources for SNMS commonly use Cs+ ions, which have been shown to improve depth resolution without affecting quantification relative to Ar+ bombardment [12] [13].

Measurement Procedure: Samples are typically mounted on conducting holders with the surface normal aligned at a specific angle (often 45°) relative to both the primary ion gun and the extraction optics. The post-ionization source parameters (electron energy and density for electron gas SNMS) are optimized to maximize ionization efficiency while minimizing energy broadening of the detected ions. During depth profiling, the primary ion beam is rastered over the analysis area while continuously sputtering the sample. The detected ion signals are recorded as a function of sputtering time, which is subsequently converted to depth scale using pre-calibrated sputter rates for the specific material system. Quantitative composition is determined using relative sensitivity factors derived from standard reference materials [12] [13].

Cryogenic Sample Preparation for Nanomedicine Characterization

Advanced applications in pharmaceutical nanomedicine characterization require specialized sample preparation protocols. For analyzing temperature-sensitive materials like PEGylated liposomal nanomedicines, a cryogenic protocol has been developed for ToF-SIMS analysis. This methodology involves rapid freezing of the nanoparticle suspension in liquid nitrogen slush to preserve the native structure and surface organization of the nanoparticles. The frozen hydrate sample is then transferred under vacuum to the SIMS analysis chamber using a specialized cryo-transfer system, maintaining temperatures below -120°C throughout the process. This approach prevents dehydration-induced reorganization of surface functional groups and enables accurate characterization of critical quality attributes such as PEG coating density on liposomal surfaces [14].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for SIMS and SNMS experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Ion Sources | Sputtering and particle ejection from sample surface | Cs+, O2+, Ga+, Bi3+ liquid metal ion guns; Energy range: 0.5-30 keV |

| Conductive Substrates | Sample mounting and charge dissipation | Silicon wafers, indium foil, gold-coated substrates |

| Charge Compensation Systems | Neutralizing surface charge on insulating samples | Low-energy electron flood guns, pulsed electron sources |

| Cryogenic Transfer Systems | Preserving native structure of biological/soft materials | Liquid nitrogen slush, vacuum transfer stages, temperature control <-120°C |

| Standard Reference Materials | Quantification calibration and instrument performance verification | Certified ion implant standards, homogeneous alloy standards, organic thin films |

| Mass Resolution Calibrants | Mass scale calibration and resolution verification | Known molecular ions (e.g., CH3+, C2H5+, C3H7+ for low mass range) |

| Ultra-high Vacuum Components | Maintaining required operational pressure | Ion pumps, turbomolecular pumps, pressure < 10⁻⁸ Pa |

Application Scenarios and Technique Selection

Pharmaceutical and Nanomedicine Development

In pharmaceutical development, particularly for nanomedicine formulations like PEGylated liposomes, SIMS has emerged as a powerful characterization tool. The cryo-ToF-SIMS methodology enables precise characterization of critical quality attributes such as PEG coating density on liposomal surfaces, which directly influences biological stability and pharmacokinetics. This application demonstrates how SIMS can distinguish between liposome formulations with varying PEG-lipid contents (3.0 to 15.5 mol%) in their outer membranes, providing essential quality control for drug manufacturing processes. The ability to probe surface functionality densities without resorting to large-scale facilities like neutron beamlines makes SIMS particularly valuable for pharmaceutical R&D and regulatory studies [14].

Materials Science and Semiconductor Applications

Both SIMS and SNMS find extensive applications in materials science, particularly for semiconductor device characterization and thin film analysis. SIMS dominates applications requiring high sensitivity for dopant profiling and contaminant detection at trace levels, leveraging its exceptional detection limits for most elements. The magnetic sector and time-of-flight SIMS instruments are widely employed for these applications, with the time-of-flight segment accounting for a significant market share [15]. SNMS excels in applications demanding precise quantitative depth profiling of multilayer structures and thin film interfaces where matrix effects would compromise SIMS quantification. The combined SNMS/SIMS instruments are particularly valuable for comprehensive analysis requiring both high sensitivity and accurate quantification across multiple elements [13].

Technique Selection Guidelines

Selecting between SIMS and SNMS depends primarily on the specific analytical requirements:

Choose SIMS when: Ultimate detection sensitivity (ppb-ppm) is required; molecular or chemical state information is needed; analysis of insulating materials without conducting coatings; or when mapping trace element distributions with high spatial resolution.

Choose SNMS when: Accurate quantification without matrix-matched standards is essential; analyzing complex multilayer structures with changing matrix composition; primarily interested in atomic composition rather than molecular information; or when high useful yield and dynamic range are prioritized.

Consider combined approaches when: Both extreme sensitivity and accurate quantification are needed across different elements; analyzing unknown samples with potentially varying matrix effects; or when comprehensive characterization justifies the instrumental complexity.

SIMS and SNMS represent complementary approaches in the ion spectroscopy toolkit for surface compositional analysis. While SIMS offers superior sensitivity and molecular detection capabilities, SNMS provides more reliable quantification with minimal matrix effects. The continuing development of both techniques, including cryogenic preparation methods for biological samples and combined instrument platforms, expands their applicability across diverse fields from semiconductor technology to pharmaceutical development. Understanding their fundamental mechanisms, performance characteristics, and implementation requirements enables researchers to strategically deploy these powerful surface analysis techniques to address specific analytical challenges in both fundamental research and industrial applications.

Electron Kinetic Energies vs. Ion Mass-to-Charge Ratios

In the realm of analytical spectroscopy, two fundamental measured outputs form the cornerstone of a wide array of surface analysis and material characterization techniques: electron kinetic energies and ion mass-to-charge ratios. These measurements provide distinct yet complementary windows into the composition, structure, and properties of materials at the molecular and atomic levels. Techniques measuring electron kinetic energies, such as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), probe the electronic structure and chemical state of surface atoms. In contrast, techniques measuring ion mass-to-charge ratios, including various forms of Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS), provide information about elemental composition, molecular structure, and isotopic distribution. This guide provides an objective comparison of these fundamental approaches, their operating principles, applications, and performance characteristics within the context of surface science research, particularly for researchers and professionals in drug development and pharmaceutical sciences.

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Background

Techniques Measuring Electron Kinetic Energies

Techniques based on measuring electron kinetic energies derive their analytical power from the photoelectric effect and related electron emission phenomena. When materials absorb photons or electrons with sufficient energy, they emit electrons whose kinetic energies carry specific information about their atomic and chemical origins.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) operates by irradiating a sample with X-rays, causing the emission of photoelectrons from core electron orbitals. The kinetic energy (EK) of these photoelectrons is measured and related to their binding energy (EB) through the fundamental equation: [ EB = h\nu - EK - \Phi ] where ( h\nu ) is the energy of the incident X-ray photon and ( \Phi ) is the work function of the spectrometer [5]. This binding energy serves as a unique fingerprint for elemental identification and provides chemical state information, as the precise binding energy shifts slightly depending on the chemical environment of the atom.

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) employs a different mechanism involving a three-step process. First, a high-energy electron beam creates a core-level vacancy. Second, an electron from a higher energy level fills this vacancy. Third, the energy released from this transition causes the emission of another electron—the Auger electron—whose kinetic energy is characteristic of the element and largely independent of the incident beam energy [16]. For AES, the kinetic energy of the Auger electron is typically described by: [ E{KL1L2} = EK - E{L1} - E{L2} ] where ( EK ), ( E{L1} ), and ( E{L_2} ) are the binding energies of electrons in the K, L₁, and L₂ shells, respectively [16].

Techniques Measuring Ion Mass-to-Charge Ratios

Techniques measuring ion mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) separate ions based on their motion in electromagnetic fields. The fundamental relationship governing these techniques stems from Newton's second law applied to charged particles in these fields.

In Mass Spectrometry (MS), the mass-to-charge ratio forms the primary measured parameter [17]. The basic principle involves converting sample molecules into gas-phase ions, separating them based on their m/z ratios, and detecting them quantitatively. Different mass analyzers achieve separation through different physical principles:

Time-of-Flight (TOF) analyzers separate ions based on the time they take to travel a fixed distance after being accelerated by a fixed electrical potential, following the relationship: [ t = L \times \sqrt{\frac{m/z}{2eV}} ] where ( t ) is the flight time, ( L ) is the flight path length, ( m/z ) is the mass-to-charge ratio, ( e ) is the elementary charge, and ( V ) is the acceleration voltage [18].

Dynamic Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) uses a focused primary ion beam to sputter material from the sample surface, with a fraction of the sputtered material being ionized (secondary ions). These secondary ions are then extracted into a mass spectrometer (typically a double-focusing mass spectrometer using electrostatic and magnetic fields) that separates them according to their mass-to-charge ratio [19].

Technical Comparison and Performance Metrics

The following tables provide a detailed comparison of the key performance metrics and characteristics for representative techniques from both categories.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Performance Metrics for Surface Analysis Techniques

| Parameter | XPS | AES | Dynamic SIMS | TOF-MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Measured Output | Electron Kinetic Energy | Electron Kinetic Energy | Ion Mass-to-Charge Ratio | Ion Mass-to-Charge Ratio |

| Information Obtained | Elemental identity, chemical state, electronic structure | Elemental identity, chemical state (limited) | Elemental/isotopic composition, trace impurities | Molecular mass, structural information |

| Detection Limits | 0.1-1 at% (1000 ppm) [5] | ~1 at% | ppm to ppb range [19] | Variable (depends on ionization) |

| Depth Resolution | 5-10 nm [5] | <5 nm [20] | <10 nm [19] | Not surface-specific |

| Lateral Resolution | 10-200 μm [5] | ~8 nm [20] | Raster scanning or direct imaging capability [19] | Not surface-specific |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Excellent (90-95% for major elements) [5] | Good with standards | Quantitative with standards [19] | Good with internal standards |

Table 2: Applications and Limitations in Pharmaceutical Research Context

| Aspect | Electron Kinetic Energy Techniques | Ion Mass-to-Charge Ratio Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strengths | Surface-sensitive, chemical state information, quantitative without standards, minimal damage (XPS) | Extreme sensitivity, isotopic discrimination, depth profiling, molecular identification |

| Common Pharmaceutical Applications | Surface composition of drug formulations, coating analysis, impurity identification | Drug metabolite identification, trace impurity analysis, protein characterization, drug delivery system studies |

| Sample Requirements | Solid surfaces, vacuum compatible, limited to ~1 cm size typically | Varied (solid, liquid, gas), specific preparation for different MS modes |

| Key Limitations | Limited sensitivity (ppm range), cannot detect H or He (XPS), potential sample damage | Destructive (SIMS), complex spectra for mixtures, matrix effects, requires calibration |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Experimental Workflow for Electron Kinetic Energy Techniques

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for techniques measuring electron kinetic energies, such as XPS and AES:

Sample Preparation Protocol for XPS/AES:

- Sample Cleaning: Remove surface contaminants using appropriate solvents (e.g., high-purity ethanol, acetone) or mild plasma cleaning

- Mounting: Secure sample on appropriate holder using conductive tape or clips to minimize charging

- Charge Neutralization: For insulating samples, apply low-energy electron flood gun for charge compensation (XPS)

- Surface Preservation: Maintain ultra-high vacuum conditions (10⁻⁷ to 10⁻⁹ Pa) to prevent surface contamination [5]

Data Collection Parameters for XPS:

- X-ray Source: Typically Al Kα (1486.7 eV) or Mg Kα (1253.7 eV)

- Analysis Area: 10 μm to 1 mm diameter, depending on instrument capabilities

- Pass Energy: 20-160 eV for survey scans, 10-50 eV for high-resolution regions

- Step Size: 1.0 eV for survey, 0.05-0.1 eV for high-resolution scans

- Acquisition Time: 2-5 minutes for survey, 5-20 minutes per high-resolution region [5]

Standard Experimental Workflow for Ion Mass-to-Charge Techniques

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for techniques measuring ion mass-to-charge ratios, such as Dynamic SIMS and TOF-MS:

Dynamic SIMS Depth Profiling Protocol:

- Primary Ion Source Selection: Choose between oxygen (Cs⁺) for electropositive elements or cesium (O₂⁺) for electronegative elements to enhance ionization yields [19]

- Sputtering Conditions: Optimize primary ion energy (typically 1-15 keV) and current to balance depth resolution and detection sensitivity

- Analysis Area Definition: Use electronic gating or physical apertures to select analysis area and exclude crater edge effects

- Data Acquisition: Continuously monitor secondary ion signals as function of sputtering time, converting to depth using calibrated sputtering rates

- Quantification: Apply relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) derived from matrix-matched standards to convert ion intensities to concentrations [19]

Mass Spectrometry Parameters for Drug Analysis:

- Ionization Method: Electrospray ionization (ESI) for polar compounds, atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) for low-to-medium polarity compounds [21]

- Mass Analyzer: Selection based on required resolution and application (Q-TOF for accurate mass, Orbitrap for high resolution)

- LC-MS Conditions: Reverse-phase C18 columns, water/acetonitrile gradients with 0.1% formic acid modifier

- Calibration: External calibration or internal standardization with stable isotope-labeled analogs [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Electron and Ion Spectroscopy

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Certified XPS reference samples (Au, Ag, Cu), ISO 15472 CRM | Energy scale calibration, instrument performance verification |

| Sample Preparation | Conductive tapes (Cu, C), sample holders, ultrasonic cleaner, plasma cleaner | Sample mounting, surface cleaning, charge reduction |

| Ion Source Materials | Cesium, oxygen, gallium primary ion sources | Primary ion beams for SIMS analysis [19] |

| MS Standards | Tuning and calibration solutions (e.g., NaI, CsI), PEG standards | Mass accuracy calibration, instrument performance verification |

| Chromatography | HPLC-grade solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol), volatile buffers (ammonium acetate, formate) | Mobile phases for LC-MS applications [21] |

Applications in Drug Development and Pharmaceutical Research

Electron Spectroscopy Applications

XPS finds important applications in pharmaceutical research for characterizing the surface composition of drug formulations and delivery systems. The technique provides quantitative information about elemental composition and chemical states at the surface of solid dosage forms, which is critical for understanding coating uniformity, contamination, and surface segregation of excipients. For example, XPS can detect the presence of surface lubricants (e.g., magnesium stearate) on tablets, analyze the composition of multi-layer coatings, and identify surface contaminants that may affect drug performance or stability [5].

AES, with its superior lateral resolution, is particularly valuable for investigating small-scale surface features and inclusions in drug formulations. The technique can map the distribution of elements across tablet surfaces with sub-micrometer resolution, providing insights into mixing homogeneity and potential segregation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) or excipients during processing [20].

Mass Spectrometry Applications

Mass spectrometry techniques, particularly those measuring ion mass-to-charge ratios, play indispensable roles throughout drug discovery and development. During early discovery, MS is used for high-throughput characterization of synthetic compounds, confirmation of chemical structures, and purity assessment [21]. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) becomes the workhorse technique for metabolite identification, pharmacokinetic studies, and impurity profiling during preclinical and clinical development.

Dynamic SIMS offers unique capabilities for elemental and isotopic imaging in pharmaceutical research. The technique can generate three-dimensional maps of elemental distributions within drug delivery systems with excellent sensitivity (ppm to ppb) and spatial resolution (down to nanometers). This is particularly valuable for studying the distribution of APIs and excipients in controlled-release formulations, investigating cross-layer diffusion in multi-layer tablets, and analyzing the incorporation of trace elements in drug crystals [19].

Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry (CD-MS) and Orbitrap Individual Ion Mass Spectrometry (I²MS) represent recent advances for analyzing heterogeneous and high-mass samples that challenge conventional MS approaches. These single-ion MS methods determine the mass of each individual ion from simultaneous measurement of both m/z and charge, enabling accurate mass measurements for samples ranging from kilo-Daltons to giga-Daltons. This capability opens new possibilities for characterizing viruses, gene therapies, vaccines, and other large biological assemblies relevant to modern pharmaceutical development [22].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The convergence of techniques measuring electron kinetic energies and ion mass-to-charge ratios represents an important trend in analytical science. Hybrid approaches that combine multiple spectroscopic techniques within a single instrument platform are becoming increasingly common, providing complementary data from the same sample region. For instance, combined XPS-SIMS instruments offer simultaneous elemental/chemical state information from XPS with high-sensitivity elemental and molecular information from SIMS.

Another significant development is the advancement of ambient pressure XPS, which enables analysis of samples under more realistic environmental conditions rather than requiring ultra-high vacuum. This capability is particularly relevant for pharmaceutical applications where hydrated states or atmospheric exposure conditions need to be preserved during analysis [5].

In the mass spectrometry domain, continued improvements in mass resolution, detection sensitivity, and data acquisition speeds are expanding the application space for pharmaceutical analysis. The development of higher-resolution CD-MS instruments promises to enable direct analysis of highly complex mixtures such as cell lysates and to facilitate studies of small ligand binding to large biological assemblies, including drug molecule interactions with viruses and other therapeutic targets [22].

Inherent Strengths and Fundamental Limitations of Each Approach

Surface analysis is a critical component of materials science, playing a pivotal role in characterizing material properties, investigating failure mechanisms, and driving innovation in fields ranging from semiconductor manufacturing to pharmaceutical development. These techniques enable researchers to determine the elemental composition, chemical state, and structure of the outermost layers of a material, which often dictate its performance and interaction with the environment. Among the diverse array of analytical methods available, electron and ion spectroscopy represent two foundational approaches that operate on different physical principles and offer complementary information.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of two prominent surface analysis techniques: Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) as a representative electron spectroscopy method, and Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS) as a representative ion spectroscopy technique. We will objectively examine their fundamental principles, inherent strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications through structured data presentation, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to assist researchers in selecting the optimal technique for their specific analytical challenges.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

AES is a surface-sensitive analytical technique that utilizes a high-energy electron beam (typically 2-10 kV) as an excitation source. When this electron beam strikes a sample surface, it ejects core-level electrons from atoms, creating excited ions. These ions relax through a radiative or non-radiative process. In the Auger process, an electron from a higher energy level fills the core hole, and the excess energy causes the emission of a third electron—the Auger electron. The kinetic energy of these emitted Auger electrons is characteristic of elements within the top 3-10 nm of the sample surface, providing elemental identification and compositional data [23] [24] [25].

Modern AES instruments incorporate several key components: an electron gun (often with field emission sources enabling spatial resolution down to <10 nm), an energy analyzer for detecting ejected electrons, an ion sputter gun for depth profiling, and an ultra-high vacuum chamber to prevent surface contamination and allow mean-free path for electrons. The ability to focus the electron beam to diameters of 10-20 nm makes AES exceptionally powerful for elemental analysis of small surface features [26] [27] [25].

Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS)

ISS is an analytical technique that provides direct structural, topographical, and atomic compositional information at interfaces using ions as projectiles. In ISS, a beam of noble gas ions (typically He+, Ne+, or Ar+) with known energy is directed at the sample surface. When these primary ions collide with surface atoms, they lose energy through elastic binary collisions. The energy of the scattered ions is measured at a specific angle, and this energy loss is characteristic of the mass of the target atoms, following classical scattering laws [28].

The technique is particularly surface-sensitive, with information coming primarily from the outermost atomic layer. A variant called Neutral Impact Collision Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (NICISS) is especially useful for probing liquid interfaces. ISS achieves exceptional depth resolution of approximately 1-2 Å, depending on experimental parameters, making it ideal for studying atomic layer composition and structure [28].

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Technical Capabilities and Performance Parameters

Table 1: Comparison of Key Technical Parameters between AES and ISS

| Parameter | Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) | Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS) |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Beam | High-energy electrons (2-10 keV) | Noble gas ions (He+, Ne+, Ar+) |

| Detected Signal | Auger electrons | Scattered ions/neutral atoms |

| Information Depth | 3-10 nm [23] [25] | Top atomic layer (∼1-2 Å) [28] |

| Lateral Resolution | ≥10 nm [27] [25] | Typically hundreds of µm to mm |

| Detectable Elements | Li to U (all except H and He) [26] [25] | All elements, dependent on projectile mass |

| Detection Sensitivity | 0.1-1 atomic % [25] | Varies by element, typically <1% monolayer |

| Depth Profiling | Yes (with sputter ion gun) [24] [26] | Limited capability |

| Quantitative Analysis | Semi-quantitative (standards improve accuracy) [25] | Quantitative with appropriate models |

| Typical Analysis Time | 30 minutes to several hours [23] | Minutes to hours |

Strengths and Limitations

Table 2: Inherent Strengths and Limitations of AES and ISS

| Aspect | Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) | Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Strengths | • High spatial resolution (<10 nm) [27]• Elemental mapping capability [26]• Depth profiling with high resolution (2-20 nm) [25]• Sensitivity to light elements (Li onwards) [25]• Well-established quantification protocols | • Exceptional surface sensitivity (top monolayer) [28]• Direct structural and topographical information [28]• Capability to probe liquid interfaces [28]• Quantitative atomic composition• High depth resolution (1-2 Å) [28] |

| Fundamental Limitations | • Requires conductive/semiconducting samples [23] [26]• Potential for electron beam damage [23]• Ultra-high vacuum compatibility required [25]• Relative error rate of 10-20% in quantification [23]• Cannot detect hydrogen or helium [26] | • Limited lateral resolution [28]• Challenging for high-vapor pressure liquids [28]• Limited access to buried interfaces [28]• Potential for ion beam damage• Complex data interpretation for rough surfaces |

| Optimal Applications | • Defect and particle analysis [25]• Small-area depth profiling [25]• Semiconductor failure analysis [26]• Thin film composition analysis [25]• Metallurgical research [25] | • Molecular orientation at interfaces [28]• Composition and distribution of atoms as function of depth [28]• Vapor-liquid interface studies [28]• Environmental pollutant tracking [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard AES Analysis Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Samples must be vacuum-compatible and ideally conductive or semi-conductive. Insulating samples may require special preparation such as coating with a thin carbon or metal layer, though this may obscure the original surface chemistry [23] [26].

- Sample dimensions typically limited to instrument stage specifications (usually several cm in diameter).

- Surface cleaning may be performed in situ using ion sputtering to remove adventitious carbon contamination [26].

Data Acquisition:

- The sample is transferred to an ultra-high vacuum chamber (typically ≤10⁻⁸ Pa) [29].

- A primary electron beam is focused on the area of interest with accelerating voltages typically between 2-10 kV and beam currents from pA to nA range [24].

- Auger electrons are collected by a hemispherical energy analyzer, which measures their kinetic energy distribution [29].

- For depth profiling, an ion sputter gun (typically Ar⁺ with 0.5-5 keV energy) is used to sequentially remove material while performing AES analysis [24] [26].

- Elemental maps are acquired by scanning the electron beam across the surface and recording specific Auger transitions at each pixel [27].

Data Analysis:

- Peak identification based on characteristic Auger energies for each element.

- Quantitative analysis using sensitivity factors derived from standard materials [25].

- Depth profiles are reconstructed by plotting elemental concentrations as a function of sputtering time, which can be converted to depth using calibration standards [24].

Standard ISS Analysis Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Samples must be compatible with vacuum environment.

- Liquid samples require special handling to minimize evaporation, particularly for high-vapor pressure liquids [28].

- Solid surfaces should be clean; in situ cleaning with ion sputtering may be employed.

Data Acquisition:

- A beam of noble gas ions (typically ⁴He⁺, ²⁰Ne⁺, or ⁴⁰Ar⁺) with well-defined energy (usually 0.5-3 keV) is directed at the sample surface [28].

- Scattered ions are energy-analyzed at a specific scattering angle (typically 90°-180°) using an electrostatic analyzer.

- For NICISS, both ions and neutral atoms are detected, extending the capability to buried interfaces and liquid surfaces [28].

- Time-of-flight measurements may be employed for energy analysis of neutrals.

Data Analysis:

- Energy spectra are converted to mass scale using classical scattering equations.

- Concentration depth profiles are extracted from the energy spectrum of scattered particles using appropriate deconvolution algorithms [28].

- Structural information is derived from shadowing and focusing effects observed in angular distributions.

Visualization of Technique Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Substrates (Gold, Silicon wafer, HOPG) | Provides suitable surface for analysis of non-conductive materials | For AES analysis of insulating samples, thin coating (≤10 nm) may be applied [23] [26] |

| Argon Gas Supply (High purity, 99.999%) | Source for ion sputter gun for depth profiling | Used in both AES and ISS for surface cleaning and depth profiling [24] [28] |

| Standard Reference Materials (Elemental standards, thin film standards) | Quantification and instrument calibration | Critical for accurate quantitative analysis in AES [25] |

| UHV-Compatible Mounting (Specialized holders, clips) | Secure sample positioning in vacuum | Ensures stability during analysis and thermal management |

| Surface Cleaning Supplies (Solvents, plasma cleaners) | Removal of adventitious contamination | Essential for reproducible surface-sensitive measurements |

| Noble Gases (He, Ne, Ar - high purity) | Projectile sources for ISS | Selection depends on target elements and required mass resolution [28] |

Application Case Studies

AES in Semiconductor Failure Analysis

AES has made significant contributions to very-large-scale integration (VLSI) technology, which involves ion implanting high dopant quantities into devices with minimal layer depths. In one application, AES was used to analyze self-assembled monolayer (SAM) films in semiconductor manufacturing. The analysis successfully identified fluorine KLL Auger electrons at 648 eV in specific patterned regions, with concentrations of 11.7% and 10.3% in the SAM-coated areas compared to 0.36% in silicon dioxide regions. This demonstrated the technique's capability for quantitative mapping of elemental distributions at the nanoscale, confirming the uniformity of vapor-deposited SAM films critical for advanced chip manufacturing [26].

ISS at Liquid Interfaces

ISS has emerged as a valuable technique for probing vapor-liquid interfaces, providing direct information about molecular orientation, composition, and distribution of atoms as a function of depth. In studies of ionic liquids and aqueous solutions, ISS has revealed how ions and solute molecules arrange themselves at interfaces with depth resolution of ∼1-2 Å. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding specific ion effects, atmospheric reactions in aerosol and seawater droplets, and the behavior of environmental pollutants like heavy metal ions and per-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) at interfaces [28].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that AES and ISS offer complementary capabilities for surface characterization, each with distinct strengths and limitations. AES excels in high spatial resolution elemental mapping and depth profiling of conductive materials, making it indispensable for semiconductor, metallurgical, and thin film applications. Its ability to focus electron beams to nanometer-scale spots enables analysis of tiny features and defects that would be inaccessible to many other techniques.

ISS provides unparalleled sensitivity to the outermost atomic layer and unique capability for probing liquid interfaces, offering insights into molecular orientation and surface structure that complement the elemental information from AES. Its quantitative nature and exceptional depth resolution make it valuable for fundamental studies of interfacial phenomena.

The selection between these techniques should be guided by specific analytical needs: AES for nanoscale elemental analysis of solid surfaces, and ISS for ultimate surface sensitivity and liquid interface studies. As surface analysis continues to evolve, integration of these techniques with complementary methods and emerging technologies like machine learning promises to further expand their capabilities and applications in scientific research and industrial development.

Techniques in Action: Applying Electron and Ion Spectroscopy to Solve Biomedical Problems

Surface Chemistry and Contamination Analysis with XPS and AES

The performance and reliability of modern materials, from pharmaceutical devices to semiconductor chips, are profoundly influenced by their outermost atomic layers. Surface chemistry dictates critical properties including adhesion, corrosion resistance, biocompatibility, and catalytic activity. Consequently, analyzing surface composition and contamination is a cornerstone of materials research and development. Among the most powerful techniques for this purpose are X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), both electron spectroscopies that provide elemental and chemical information from the top 1-10 nanometers of a material [30].