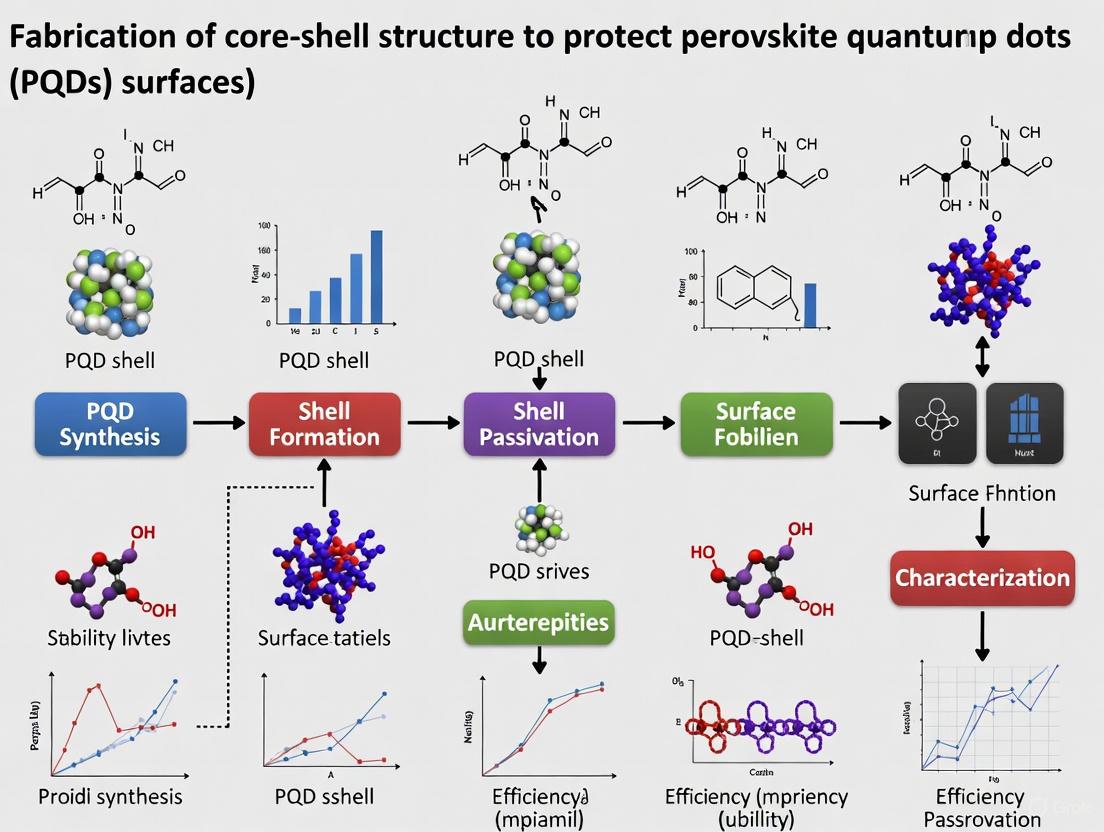

Core-Shell Structures for Perovskite Quantum Dot Surface Protection: Synthesis, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of core-shell structure fabrication strategies designed to enhance the stability and performance of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) for biomedical applications.

Core-Shell Structures for Perovskite Quantum Dot Surface Protection: Synthesis, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of core-shell structure fabrication strategies designed to enhance the stability and performance of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) for biomedical applications. It explores the fundamental mechanisms by which inorganic and organic-inorganic hybrid shells, such as SiO₂, mitigate PQD degradation caused by environmental factors and intrinsic defects. The scope covers advanced synthesis methodologies including sol-gel techniques and ligand engineering, performance optimization to address aqueous instability and lead leaching, and rigorous validation through comparative analysis with other nanomaterials. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review serves as a critical resource for leveraging the superior optoelectronic properties of stabilized PQDs in biosensing, diagnostics, and other clinical platforms.

Understanding PQD Instability and the Core-Shell Protection Principle

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), particularly inorganic halide perovskites such as CsPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I), have emerged as pivotal materials for next-generation optoelectronic technologies due to their exceptional optical properties, including tunable bandgaps, high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), and defect-tolerant structures [1]. Despite their promising characteristics, the widespread commercialization of PQDs is severely hampered by their intrinsic vulnerabilities to environmental factors and operational stresses. The fundamental instability arises primarily from two interconnected mechanisms: the migration of ions within the crystal lattice and the detachment of surface-bound ligands [2]. These vulnerabilities are inherent to the ionic nature of perovskite materials and the dynamic nature of their surface chemistry, leading to rapid degradation under realistic operating conditions.

Understanding these degradation pathways is crucial for developing effective stabilization strategies, particularly core-shell architectures that provide a physical barrier against environmental stressors while passivating surface defects. This application note provides a comprehensive analysis of these intrinsic vulnerabilities, supported by quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols for assessing and mitigating these critical failure modes, specifically within the context of core-shell structure fabrication for PQD surface protection.

Fundamental Degradation Mechanisms

Ion Migration and Vacancy Formation

Ion migration constitutes one of the most critical intrinsic vulnerabilities of PQDs. The ionic crystal lattice of perovskites, while enabling excellent optoelectronic properties, also facilitates the mobility of halide ions (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) and vacancies under external stimuli such as electric fields, light, or heat.

- Low Migration Energy Barriers: Halide ions exhibit relatively low activation energy for migration within the perovskite lattice [2]. This low energy barrier facilitates the easy formation and movement of halide vacancies, acting as trapping sites for charge carriers.

- Vacancy-Mediated Degradation: The migration process is primarily vacancy-mediated. Under operational stress, halide ions leave their lattice sites, creating vacancies that propagate through the crystal structure. These vacancies serve as non-radiative recombination centers, reducing PLQY and accelerating material degradation [2].

- Phase Segregation and Structural Collapse: The accumulation of ion vacancies and their migration leads to phase segregation in mixed-halide PQDs and ultimately initiates the collapse of the crystalline structure, resulting in irreversible damage to the optical properties of the material [2].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and consequences of ion migration in PQDs:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Ion Migration on PQD Properties

| Aspect | Effect on PQDs | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Halide Vacancy Formation Energy | Relatively low, facilitating defect formation | Theoretical calculations showing low migration energy barriers [2] |

| PLQY Reduction | Significant decrease due to non-radiative recombination | PLQY drops from >80% to below 50% under electrical stress [3] |

| Operational Lifetime Impact | Accelerated device failure | T50 lifetime of blue-emitting Cd-free QLEDs only 442 h at 650 cd/m² [3] |

| Color Purity Degradation | Emission spectrum broadening and peak shift | FWHM increase and peak wavelength shift under continuous illumination [2] |

Ligand Detachment and Surface Defects

The surface chemistry of PQDs plays an equally crucial role in their stability. PQDs are typically synthesized with organic ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) that coordinate to surface atoms to provide colloidal stability and passivate surface defects. However, this passivation is inherently unstable.

- Dynamic Binding Equilibrium: Ligands such as OA and OAm bind to the PQD surface through relatively weak coordinate bonds, establishing a dynamic equilibrium where ligands continuously attach and detach from the surface [2] [4]. This dynamic process creates temporary unpassivated surface sites that act as traps for charge carriers.

- Steric Hindrance: The molecular structures of commonly used ligands like OA and OAm contain double bonds that create kinks in their alkyl chains, resulting in significant steric hindrance that reduces ligand packing density on the PQD surface [2]. This inefficient coverage leaves substantial portions of the surface vulnerable to environmental attacks.

- Purification-Induced Detachment: Standard purification processes involving polar antisolvents like methyl acetate or butanol accelerate ligand detachment, creating surface defects that become initiation points for further degradation [2]. This manifests experimentally as a significant drop in PLQY after purification cycles.

The relationship between ligand detachment and subsequent degradation pathways can be visualized through the following mechanistic diagram:

Diagram 1: Ligand Detachment Impact Pathway

Quantitative Analysis of PQD Vulnerabilities

The vulnerabilities of PQDs can be quantitatively assessed through specific experimental measurements. The following table compiles key stability metrics reported in recent literature, highlighting the dramatic improvements possible through effective stabilization strategies, particularly core-shell architectures:

Table 2: Comparative Stability Metrics of PQDs with Different Stabilization Approaches

| Stabilization Method | PLQY Retention (%) | Test Conditions | Timeframe | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpassivated CsPbBr₃ QDs | <50% | Ambient conditions, 60% RH | 7 days | [5] |

| Core-Shell (CsPbBr₃/CdS) | >88% initial, high retention | Ambient conditions | 30 days | [5] |

| Ligand Exchange (AET) | >95% | Water exposure & UV light | 60-120 min | [2] |

| Advanced Encapsulation | >95% | 60% RH, 100 W cm⁻² UV | 30 days | [1] |

| In Situ Epitaxial PQD Passivation | >92% device PCE | Ambient conditions | 900 hours | [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Vulnerability Assessment

Protocol: Quantifying Ion Migration Through Thermal Stress Testing

Objective: To evaluate the intrinsic thermal stability of PQDs and quantify ion migration kinetics under controlled temperature conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- PQD sample in solution or film form

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with temperature-controlled stage

- Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy system

- Thermal chamber or hot plate

- Quartz cuvettes or substrates

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- For solution samples, dilute the PQD solution to an optical density of approximately 0.1 at the first excitonic peak in an inert atmosphere glovebox.

- For film samples, spin-coat PQDs onto clean quartz substrates at optimized parameters to form uniform films.

Initial Characterization:

- Record UV-Vis absorption spectrum from 300-800 nm.

- Measure PL spectrum, noting peak position, full width at half maximum (FWHM), and integrated intensity.

- Calculate initial PLQY using an integrating sphere attachment.

Thermal Stress Application:

- Place samples in a temperature-controlled environment at predetermined temperatures (e.g., 50°C, 75°C, 100°C).

- For each temperature condition, expose samples for set time intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- After each interval, remove samples and allow to cool to room temperature before characterization.

Post-Stress Characterization:

- Repeat UV-Vis and PL measurements after each thermal stress interval.

- Note any changes in absorption edge, PL peak position, FWHM, and intensity.

- For advanced analysis, perform X-ray diffraction (XRD) to detect phase changes or crystal structure degradation.

Data Analysis:

- Plot normalized PL intensity versus time for each temperature to determine degradation kinetics.

- Calculate activation energy for thermal degradation using Arrhenius analysis.

- Correlate PL peak shifts with halide migration using established models.

Expected Outcomes: Unstable PQDs will exhibit significant PL quenching, peak shifts, and absorption changes proportional to temperature and exposure duration. Stable core-shell structures will maintain optical properties with minimal degradation.

Protocol: Assessing Ligand Stability Through Purification Cycles

Objective: To evaluate the binding strength of surface ligands and their resistance to detachment during purification processes.

Materials and Equipment:

- As-synthesized PQD solution

- Purification solvent (typically methyl acetate, butanol, or acetone)

- Centrifuge

- FTIR spectrometer

- NMR spectrometer (for ligand quantification)

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement:

- Characterize initial PQD sample using PL spectroscopy to determine starting PLQY.

- Perform FTIR spectroscopy to identify characteristic ligand peaks (e.g., C=O stretch for OA, N-H for OAm).

- For quantitative analysis, use NMR to determine initial ligand density.

Purification Cycle:

- Add purification solvent (typically 3-5 times volume of PQD solution) to precipitate PQDs.

- Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 8,000-10,000 rpm) for 5-10 minutes.

- Carefully decant the supernatant containing excess ligands and reaction byproducts.

- Redisperse the precipitate in original solvent (e.g., toluene, hexane).

Post-Purification Analysis:

- Measure PLQY after each purification cycle.

- Monitor changes in FTIR spectra to track ligand coverage.

- For advanced analysis, use XPS to quantify elemental ratios at the surface.

Multiple Cycle Testing:

- Repeat the purification cycle 3-5 times, analyzing optical properties and ligand coverage after each cycle.

- Plot PLQY versus purification cycle number to quantify ligand stability.

Ligand Exchange Evaluation:

- Compare traditional OA/OAm ligands with alternative ligands (e.g., 2-aminoethanethiol) with stronger binding groups.

- Evaluate the purification stability of these alternative ligand systems.

Expected Outcomes: Weakly bound ligands will show rapid PLQY decline with successive purification cycles, while strongly bound or cross-linked ligands will maintain high PLQY through multiple cycles.

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive vulnerability assessment integrating both protocols is as follows:

Diagram 2: Vulnerability Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Vulnerability Research and Core-Shell Fabrication

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium precursor for inorganic PQD synthesis | Requires complete dissolution in OA/ODE at elevated temperatures [5] |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead precursor for perovskite formation | Must be thoroughly dried and stored in inert atmosphere [5] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand, acid precursor | Purification recommended; dynamic binding to PQD surface [2] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligand, amine precursor | Often used with OA; steric hindrance limits packing density [2] |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) | Strong-binding alternative ligand | Thiol group coordinates strongly with Pb²⁺; improves stability [2] |

| Cadmium Oleate | Shell precursor for CdS formation | Requires precise concentration control for uniform shell growth [5] |

| Sulfur-ODE Solution | Sulfur source for sulfide shells | Injection rate critical for controlled shell growth [5] |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide | Shell precursor for perovskite shells | Enables formation of core-shell perovskite structures [6] |

| Methyl Acetate | Purification solvent | Polar solvent precipitates PQDs; causes ligand detachment [2] |

Core-Shell Fabrication as a Protection Strategy

The implementation of core-shell structures represents the most promising approach to address both ion migration and ligand detachment simultaneously. The shell material serves as a physical diffusion barrier against environmental factors while providing a new surface for more stable ligand binding.

Protocol: CdS Shell Growth on CsPbBr₃ Core PQDs

Objective: To synthesize CsPbBr₃/CdS core-shell quantum dots with enhanced stability against ion migration and ligand detachment.

Materials: Refer to Table 3 for key reagents.

Procedure:

- Core Synthesis:

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs following the hot-injection method by Protesescu et al. [5].

- Heat 5 mL ODE and 69 mg PbBr₂ in a 100 mL flask to 120°C under N₂ for 1 hour.

- Inject 0.5 mL OAm and 0.5 mL OA at 120°C under N₂.

- Once PbBr₂ is dissolved, raise temperature to 150°C and quickly inject 0.4 mL Cs-oleate solution (0.125 M in ODE).

- React for 5 seconds to form CsPbBr₃ core QDs.

Shell Precursor Preparation:

- Prepare Cd-oleate solution by dissolving 383 mg CdO in 3.9 mL OA and 3.9 mL ODE at 280°C under N₂ flow until clear.

- Prepare sulfur precursor by dissolving sulfur in OAm (1 M concentration).

Shell Growth:

- After core synthesis, maintain temperature at 150°C.

- Slowly add a mixture of 4 mL ODE, 1 mL Cd-oleate solution, and 0.4 mL sulfur-ODE solution dropwise over 20 minutes.

- Allow reaction to proceed for additional 20 minutes at 150°C.

Purification and Characterization:

- Cool reaction mixture rapidly in ice-water bath.

- Purify by centrifugation with toluene multiple times.

- Characterize using TEM, XRD, PL spectroscopy, and EDX to confirm core-shell structure.

Expected Outcomes: Successful core-shell formation demonstrated by increased particle size (e.g., from 12.7 nm to 22.1 nm), maintained high PLQY (>88%), and characteristic XRD patterns showing both perovskite and CdS phases [5].

The architecture of a core-shell structure and its protective mechanisms can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 3: Core-Shell Protection Mechanism

The intrinsic vulnerabilities of PQDs - ion migration and ligand detachment - present significant challenges for their commercial application in optoelectronic devices. However, as demonstrated through the protocols and data presented herein, these vulnerabilities can be quantitatively assessed and effectively mitigated through rational material design, particularly through core-shell architectures. The implementation of core-shell structures addresses both degradation pathways simultaneously by providing a physical diffusion barrier against ion migration while stabilizing the surface chemistry against ligand detachment. Continued research in optimizing shell composition, thickness, and interface quality will be essential for realizing the full potential of PQDs in commercial applications, particularly in the demanding environments of display technologies and lighting applications where operational stability is paramount.

The core-shell paradigm represents a foundational design principle in materials science, enabling the creation of sophisticated nanostructures with enhanced stability and functionality. This architecture involves encapsulating a core material within a protective shell, creating a physical barrier that mitigates degradation from environmental factors such as oxygen, moisture, heat, and chemical reactants [7]. The protective efficacy of the shell layer operates through multiple mechanisms: it physically isolates the core from corrosive environments, provides a chemically stable interface, and can be functionally engineered for specific protective requirements [7] [8]. For researchers developing perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and other sensitive nanomaterials, implementing core-shell structures is a critical strategy for improving material longevity and performance under operational conditions. These Application Notes provide detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for designing, synthesizing, and characterizing core-shell materials with optimized protective properties.

Fundamental Protective Mechanisms of Core-Shell Structures

The degradation mitigation offered by core-shell structures stems from several interconnected physical and chemical mechanisms:

Physical Barrier Protection: The shell layer creates a continuous physical barrier that prevents direct contact between the core material and external degrading agents. For instance, a dense SiO2 shell can effectively shield a magnetic Fe3O4 core from atmospheric oxygen, thereby preventing oxidation and consequent loss of magnetic properties [7]. Similarly, in inorganic metal oxides, the shell protects the core from thermal oxidative degradation when incorporated into polymer and resin compositions [8].

Chemical Passivation: Shell materials can terminate reactive surface sites on the core material, reducing its susceptibility to chemical reactions. This is particularly relevant for PQDs, where surface defects act as non-radiative recombination centers and degradation initiation points.

Interfacial Stabilization: The core-shell interface can be engineered to minimize lattice mismatch and associated strain, which contributes to long-term structural integrity. This is critical for maintaining optical properties in semiconductor nanocrystals.

Matrix Isolation: In complex matrices such as foods or polymer resins, the shell can shield the core from interacting with incompatible components, as demonstrated by metal oxide core-shell composites that prevent thermal oxidative degradation in plastics [8].

Synthesis Protocols for Protective Core-Shell Architectures

Coprecipitation Method for Magnetic Core-Shell Nanomaterials

The coprecipitation method offers an environmentally friendly and cost-effective approach for synthesizing core-shell structures, particularly suitable for food safety and biomedical applications [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Magnetic Core Synthesis (Fe3O4):

- Prepare an aqueous solution containing 1:2 molar ratio of FeCl₂ to FeCl₃ in deoxygenated water under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Heat the solution to 70°C with vigorous mechanical stirring at 1000 rpm.

- Add ammonium hydroxide (25% w/w) dropwise until pH reaches 10-11.

- Continue reaction for 1 hour until black magnetite precipitate forms.

- Separate nanoparticles using magnetic decantation and wash with deoxygenated water until neutral pH.

- Shell Formation (SiO₂ Coating):

- Redisperse purified Fe3O4 nanoparticles in a mixture of ethanol (200 mL), deionized water (50 mL), and concentrated ammonia (2 mL).

- Add tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) dropwise (1-5 mmol depending on desired shell thickness) with continuous sonication.

- React for 6-24 hours at room temperature with gentle stirring.

- Recover core-shell nanoparticles via magnetic separation and wash three times with ethanol.

Key Parameters: Precise control of pH, temperature, and reagent addition rate is critical for uniform shell formation. The shell thickness can be tuned by varying the TEOS concentration and reaction time [7].

Gram-Scale Synthesis of Pt-Co@Pt Core-Shell Catalysts

This protocol demonstrates a scalable approach for creating metallic core-shell structures with enhanced durability, adaptable for precious metal coatings on sensitive nanocrystals.

Experimental Protocol:

- Core Formation (Pt-Co/C):

- Mix 3.00 g carbon black (XC-72) with 200 mL deionized water.

- Sonicate for 60 minutes to achieve homogeneous dispersion.

- Add 4.10 g H₂PtCl₆·6H₂O and 2.30 mg Co(NO₃)₂ to the suspension.

- Adjust pH to 10 using NaHCO₃ solution (1M) with continuous stirring.

- Add 1 mol/L HCHO solution (10 mL) as reducing agent and stir for 1 hour.

- Transfer mixture to Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 160°C for 8 hours.

- Recover catalyst by filtration, washing, and vacuum drying at 80°C for 12 hours.

- Shell Formation and Optimization:

- Acid Treatment: Disperse Pt-Co/C catalyst in 0.5M H₂SO₄ at 60°C for 4 hours to remove surface Co atoms and initiate Pt shell formation.

- Heat Treatment: Following acid treatment, anneal catalyst at 500°C under H₂/Ar atmosphere (5%/95%) for 2 hours to consolidate core-shell structure.

- Characterize resulting Pt-Co@Pt/C core-shell structure with TEM and XRD to confirm ~1.5 nm Pt shell formation [9].

Key Parameters: The acid treatment duration and thermal annealing conditions determine the final shell thickness and structural integrity, with optimal performance achieved with 1-1.5 nm Pt shells [9].

"Dragon Fruit" vs "Peach" Morphology Control

The spatial distribution of active sites within core-shell structures significantly impacts their catalytic performance and durability. The "dragon fruit" morphology, with active sites distributed throughout the mesoporous silica shell, accommodates higher Pt loading compared to the "peach" morphology where active sites are concentrated in the core [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Core Synthesis (SiO₂@Pt):

- Synthesize silica cores via Stöber method with tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) precursor.

- Functionalize silica surface with amine groups using (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES).

- Immerse functionalized cores in Pt nanoparticle suspension for 2 hours with sonication.

- Shell Formation with Controlled Morphology:

- For "peach" morphology: Add TEOS slowly with minimal agitation to allow preferential deposition around core.

- For "dragon fruit" morphology: Pre-mix Pt nanoparticles with TEOS before addition, with vigorous stirring to ensure uniform distribution throughout growing shell.

- Recover by centrifugation and characterize morphology by TEM and nitrogen adsorption [10].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Core-Shell vs. Unprotected Materials

| Material System | Protection Mechanism | Performance Metric | Unprotected Core | Core-Shell Structure | Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe₃O₄@SiO₂ | Oxidation barrier | Magnetic stability (cycles) | 5-10 cycles | 50+ cycles | >500% | [7] |

| Pt-Co@Pt/C | Leaching prevention | ORR activity retention after ADT | 47 mV shift | 6 mV shift | 87% improvement | [9] |

| Polymer/Metal Oxide composites | Thermal oxidative barrier | Degradation temperature | 200-250°C | 300-350°C | ~50% increase | [8] |

| "Dragon Fruit" catalyst | Spatial distribution | Benzene yield (mg/mg catalyst) | Baseline | 2.1x higher | 110% increase | [10] |

Table 2: Core-Shell Synthesis Methods Comparison for Degradation Mitigation

| Synthesis Method | Typical Shell Materials | Shell Uniformity Control | Scalability | Best Applications | Protective Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coprecipitation | SiO₂, ZnO, polymers | Moderate | High | Food safety, biomedical | Good for chemical barrier |

| In-situ Synthesis | MOFs, molecularly imprinted polymers | High | Moderate | Sensing, catalysis | Excellent for selective protection |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition | Pyrolytic carbon, inorganic oxides | Very high | Low | High-temperature applications | Superior for thermal/oxidative protection |

| Self-assembly | Polymers, graphene, biomolecules | Variable | Moderate to low | Specialized applications | Tunable based on building blocks |

| Sacrificial Template | Hollow structures, porous shells | High | Low | Catalysis, drug delivery | Excellent for compartmentalization |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Core-Shell Synthesis for Surface Protection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | SiO₂ shell precursor | Hydrolyzes to form dense silica barrier; concentration controls shell thickness | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America |

| Metal acetylacetonates (e.g., Pt(acac)₂) | Metal oxide shell precursors | Thermal decomposition creates uniform crystalline shells | Strem Chemicals, Alfa Aesar |

| (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Surface functionalization | Provides amine groups for subsequent shell growth | Gelest, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Oleylamine/Oleic acid | Surfactant & stabilizing agent | Controls nanoparticle size and prevents aggregation during shell growth | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America |

| Molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) precursors | Functional shell formation | Creates selective recognition sites while providing protection | Custom synthesis |

| Metal-organic framework (MOF) precursors | Porous shell formation | Provides ultrahigh surface area with molecular sieving capabilities | Sigma-Aldrich, BASF |

Analytical Techniques for Characterizing Protective Efficacy

Validating the degradation mitigation in core-shell structures requires multidisciplinary characterization approaches:

Electron Microscopy: TEM and SEM provide direct visualization of core-shell morphology, shell thickness, uniformity, and structural integrity before and after environmental exposure.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Confirms crystallographic structure and can detect phase changes in core material indicating degradation.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Surface-sensitive technique that verifies shell completeness and identifies chemical states at core-shell interface.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Quantifies thermal stability improvement by measuring decomposition temperature shifts.

Accelerated Durability Testing (ADT): Subjecting materials to extreme conditions (temperature, pH, mechanical stress) to simulate long-term degradation.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Core-Shell Synthesis and Evaluation Workflow

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The core-shell paradigm continues to evolve with several emerging applications that leverage its protective capabilities:

Perovskite Quantum Dot Displays: Core-shell architectures protect sensitive PQDs from moisture and oxygen degradation while maintaining high quantum yield, enabling commercial display applications.

Fuel Cell Catalysts: As demonstrated by Pt-Co@Pt/C systems, core-shell structures prevent dissolution of non-precious metal cores while maintaining high catalytic activity, addressing durability challenges in energy conversion devices [9].

Nuclear Materials: Isotropic pyrolytic carbon with core-shell structures serves as coating for radioactive fuel particles, providing exceptional thermal and structural stability under extreme conditions [11].

Future developments will focus on multi-shell architectures, stimuli-responsive shells that adapt to environmental changes, and computational materials design for predicting optimal core-shell combinations for specific degradation challenges.

Core-shell structures represent a cornerstone of advanced material design, where a functional core is encapsulated by a protective shell to enhance stability and performance. Within this domain, silicon dioxide (SiO₂) has emerged as a premier inorganic shell material, particularly for safeguarding sensitive cores against harsh thermal and environmental conditions. The application of a SiO₂ barrier layer is a critical strategy in diverse fields, including the stabilization of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), where it mitigates susceptibility to environmental degradation. This document provides a comprehensive overview of SiO₂'s protective capabilities, supported by quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols, to serve as a practical resource for researchers and scientists engaged in material fabrication and drug development.

Application Notes: Protective Functions of SiO₂ Shells

SiO₂ shells confer enhanced stability through multiple mechanisms, including diffusion barrier formation, chemical passivation, and structural reinforcement. The following applications highlight its efficacy.

Thermal Stability for High-Temperature Processes: SiO₂ coatings significantly improve the high-temperature performance of composite materials. In ceramic environmental barrier coatings (EBCs), the incorporation of SiO₂ into matrices like AlTaO₄ reduces thermal conductivity by 26.9% and lowers the coefficient of thermal expansion (TEC) to 4.65 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹, thereby minimizing interfacial thermal stress and enhancing service life at temperatures exceeding 1400 °C [12]. Similarly, composite aerogels reinforced with fumed SiO₂ exhibit a low thermal conductivity of 0.02864 W/(m·K) and maintain structural integrity under high-temperature conditions [13].

Environmental and Chemical Barrier: The dense, amorphous network of SiO₂ acts as an effective barrier against corrosive species. In magnetorheological polishing, a 20 nm thick SiO₂ shell on carbonyl iron particles (CIPs) prevents oxidation of the magnetic core, thereby improving the chemical stability of the composite abrasive and enabling a superior surface finish with a roughness (Ra) of 1.03 nm [14]. Furthermore, in catalytic applications, SiO₂ shells prevent the agglomeration and leaching of noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Pt, Pd), maintaining catalytic activity over repeated cycles [15].

Enhancing Mechanical Integrity: SiO₂ shells contribute to the mechanical robustness of core-shell structures. In SiO₂/polymer composite microspheres synthesized via miniemulsion polymerization, the SiO₂ core forms a rigid scaffold within a poly(St-BA) matrix, significantly improving the mechanical properties and thermal stability of the resulting damping material [16].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Data of SiO₂ Shells in Various Applications

| Core Material | SiO₂ Shell Function | Key Performance Metric | Result with SiO₂ Shell | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlTaO₄ Ceramics | Thermal Insulation & TEC Matching | Thermal Conductivity (@ 900°C) | Reduced by 26.9% to 1.65 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹ | [12] |

| AlTaO₄ Ceramics | Thermal Insulation & TEC Matching | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (@ 1200°C) | 4.65 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹ | [12] |

| GA/PI Aerogel | Thermo-Mechanical Reinforcement | Compressive Strength (at 75% strain) | >3.50 MPa | [13] |

| GA/PI Aerogel | Thermo-Mechanical Reinforcement | Thermal Conductivity | 0.02864 W/(m·K) | [13] |

| CIP (Carbonyl Iron Powder) | Oxidation Barrier & Abrasive | Surface Roughness (Ra) on Fused Silica | 1.03 nm (20.16% improvement) | [14] |

| CeO₂ Abrasive | Chemical Activity Mediator | Material Removal Rate (MRR) | Up to 300 nm/min | [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sol-Gel Synthesis of a Tunable Thickness SiO₂ Shell on Silica Cores

This protocol, adapted from chromatographic silica sphere coating, details the formation of a SiO₂ shell with controllable thickness between 70–300 nm [18].

Primary Reagents and Materials:

- Core Material: Monodisperse solid SiO₂ microspheres (diameter: 1.9–3.2 µm).

- Silica Precursors: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), 1,2-bis(triethoxysilyl)ethane (BTEE), or 1,6-bis(triethoxysilyl)hexane (BTMSH).

- Surfactant/Template: Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB).

- Catalyst: Aqueous ammonia (NH₄OH, 25 wt%).

- Solvents: Anhydrous ethanol, isopropanol.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Core Dispersion: Disperse 1.0 g of solid SiO₂ microspheres in a mixture of 80 mL ethanol, 20 mL deionized water, and 0.2 g CTAB. Stir vigorously in a sealed container.

- Catalyst Addition: Add 1.0 mL of aqueous ammonia (25 wt%) to the mixture to initiate the base-catalyzed reaction.

- Shell Growth: Slowly add a mixture of the silica precursor (e.g., 1.0 mL TEOS) in 20 mL ethanol dropwise into the reaction vessel under continuous stirring.

- Reaction Control: Maintain the reaction at 30 °C for 2 hours. The shell thickness can be tailored by precisely controlling the stirring rate, solvent selection, and the type/amount of silica precursor.

- Product Isolation: Recover the core-shell particles via centrifugation, wash thoroughly with ethanol and water to remove residual reactants, and dry at 60 °C.

- Calcination (Optional): To remove the CTAB template and create mesopores, calcine the product at 550 °C for 5 hours in a muffle furnace.

Protocol: Surfactant-Free Ultrasonication Synthesis of SiO₂/ZnO Core-Shell Particles

This rapid, surfactant-free method is ideal for creating agglomeration-free core-shell particles for optical applications [19].

Primary Reagents and Materials:

- Core Material: Hydrophilic SiO₂ nanoparticles (synthesized via the Stöber method).

- Shell Precursor: Zinc acetate dihydrate.

- Solvent: Anhydrous ethanol.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Core Dispersion: Disperse a controlled molar ratio (e.g., 0.25 to 1.00 relative to SiO₂) of zinc acetate dihydrate in ethanol.

- Ultrasonication: Subject the mixture to ultrasonication using a probe sonicator (e.g., 50% power, 5 min in pulse mode: work for 1 s, stop for 2 s). This process facilitates the direct deposition of ZnO onto the SiO₂ surface.

- Shell Size Control: Control the final ZnO shell size by varying the initial molar ratio of the silica core to the zinc precursor.

- Product Isolation: Recover the SiO₂/ZnO core-shell particles by centrifugation, wash, and dry. The entire synthesis process is 75% faster than conventional sol-gel methods.

Workflow and Relationship Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and fabricating a SiO₂ shell for surface protection, integrating the protocols above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for SiO₂ Shell Fabrication

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function | Brief Rationale | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Silica Precursor | Hydrolyzes to form Si-OH, condensing into a SiO₂ network. The most common SiO₂ source. | Core-shell silica for HPLC [18], CeO₂@SiO₂ abrasives [17]. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Structure-Directing Agent (SDA) | Forms micelles that act as co-templates for mesoporous shell formation. | Creating tunable pore sizes in shell [18] [15]. |

| Aqueous Ammonia (NH₄OH) | Base Catalyst | Catalyzes the hydrolysis and condensation of silica precursors. | Standard catalyst in Stöber and sol-gel processes [18] [16]. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Coupling Agent | Provides functional -NH₂ groups on SiO₂ surface for improved core-shell bonding. | Surface modification for enhanced compatibility [14]. |

| Zinc Acetate Dihydrate | Zinc Oxide Precursor | Decomposes to form ZnO shell in non-aqueous or surfactant-free systems. | Surfactant-free SiO₂/ZnO synthesis [19]. |

| Vinyltrimethoxysilane (VTMS) | Functionalization Agent | Introduces polymerizable vinyl groups for subsequent shell modification. | Preparing HILIC stationary phases [18]. |

The integration of organic-inorganic hybrid layers represents a frontier in enhancing the structural and operational stability of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). These materials suffer from intrinsic and surface defects that facilitate non-radiative recombination and accelerate degradation under environmental stressors [20]. A promising strategy to mitigate these issues involves the engineering of core-shell architectures, where a protective layer passivates the PQD surface. This application note details the use of organic ligands, specifically didodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB), as a critical component for effective defect passivation within such structures. We contextualize this within a broader research thesis on core-shell fabrication for PQD surface protection, providing validated protocols and data for the research community [21].

Background and Principle

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of PQDs, including near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and tunable bandgaps, are often compromised by a high density of defects [22] [23]. These defects primarily consist of uncoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) ions and halide (Br⁻/I⁻) vacancies at the nanocrystal surface, which act as traps for charge carriers, reducing efficiency and stability [23] [20].

The core-shell concept addresses this by encapsulating the PQD (core) with a stabilizing layer (shell). Organic ammonium salts like DDAB are ideal shell precursors due to their molecular structure: the ammonium head group strongly coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface, while the long alkyl chains create a hydrophobic barrier against moisture and oxygen [21]. This dual action simultaneously passivates defects and enhances environmental stability, forming a robust organic-inorganic hybrid layer.

Key Experimental Data and Performance

The implementation of a bilateral passivation strategy using phosphine oxide molecules (e.g., TSPO1) and ammonium salts has demonstrated remarkable improvements in device performance. The table below summarizes key quantitative data from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Enhancement from Defect Passivation Strategies

| Performance Metric | Control Device (Unpassivated) | Passivated Device (DDAB/TSPO1) | Improvement Factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | ~7.7% | 18.7% | 2.4x | [21] |

| Current Efficiency | 20 cd A⁻¹ | 75 cd A⁻¹ | 3.75x | [21] |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) of Film | 43% | 79% | 1.8x | [21] |

| Operational Lifetime (T₅₀) | 0.8 hours | 15.8 hours | 20x | [21] |

| PLQY (Dual-Ligand Strategy) | Baseline | 98.56% | Near-unity | [24] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs via the hot-injection method, followed by a post-synthesis ligand exchange and bilateral passivation procedure for device integration, adapted from established methodologies [21] [23].

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Role in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium (A-site) precursor | Forms Cs-oleate for reaction stoichiometry. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead (B-site) and halide precursor | Forms the perovskite crystal framework. |

| Didodecyl Dimethyl Ammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Organic passivating ligand | Passivates surface defects; enhances film PLQY. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard surface ligands | Control nucleation/growth during synthesis. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent | High-booint solvent for hot-injection synthesis. |

| Toluene, Methyl Acetate | Polar solvents | Used for purification and precipitation of PQDs. |

| Diphenylphosphine Oxide-4-(triphenylsilyl)phenyl (TSPO1) | Electron-transport/Passivation molecule | Evaporated layer for bilateral interface passivation. |

Essential Equipment: Three-neck flask, Schlenk line, syringe pump, thermocouple, centrifuge, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, fluorometer, glovebox.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs via Hot-Injection

- Cs-oleate Precursor: Load 0.3258 g Cs₂CO₃ and 10 mL OA into a 20 mL vial. Stir at room temperature until dissolved, then heat to 120°C under N₂ until the solution is clear.

- PbBr₂ Precursor: In a 50 mL three-neck flask, combine 0.276 g PbBr₂, 10 mL ODE, 1 mL OA, and 1 mL OAm. Dry under vacuum for 30 minutes at 100°C to remove residual water and oxygen.

- Injection and Reaction: Under a nitrogen atmosphere, raise the temperature of the Pb-precursor flask to 150°C. Rapidly inject 1 mL of the preheated Cs-oleate precursor solution.

- Quenching: Allow the reaction to proceed for 10-30 seconds, then immediately cool the reaction flask in an ice-water bath to terminate crystal growth.

Part B: Purification and Ligand Exchange with DDAB

- Precipitation: Transfer the crude solution to a centrifuge tube. Add a 1:1 volume mixture of toluene and methyl acetate, then centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Washing and Ligand Exchange: Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in 5 mL of toluene. To this dispersion, add a calculated volume of DDAB solution (e.g., 0.1 M in toluene) to achieve a target molar ratio (e.g., PbBr₂:DDAB = 1:1.5). Sonicate for 5 minutes and stir for 30 minutes.

- Re-precipitation and Storage: Add methyl acetate to the mixture and centrifuge again. The final purified PQD pellet should be stored in an inert atmosphere in 2-3 mL of anhydrous toluene or hexane.

Part C: Bilateral Interfacial Passivation for QLED Devices [21]

- Film Fabrication: Spin-coat the purified DDAB-PQD ink onto a pre-cleaned substrate (e.g., ITO/PEDOT:PSS) to form the emissive layer.

- Bottom Interface Passivation: Prior to PQD deposition, thermally evaporate a thin layer (~5-10 nm) of TSPO1 molecules onto the hole transport layer.

- Top Interface Passivation: After depositing the PQD layer, thermally evaporate a second layer of TSPO1 directly onto the PQD film.

- Device Completion: Complete the device stack by sequentially depositing the electron transport layer (e.g., TPBi) and the cathode (e.g., LiF/Al).

Underlying Mechanisms and Pathway Analysis

The efficacy of organic ligands like DDAB stems from their synergistic interaction with the PQD surface, which can be understood through a defect passivation pathway.

The process involves two key steps, as shown in Diagram 2:

- Electrostatic Interaction & Defect Passivation: The positively charged ammonium headgroup (N⁺) in DDAB has a strong electrostatic affinity for negatively charged bromine vacancies. Concurrently, the bromide counterion (Br⁻) from DDAB can fill these halide vacancies on the PQD surface [21]. This direct ionic interaction effectively neutralizes dominant surface trap states.

- Protective Shell Formation: The long alkyl chains (dodecyl groups) of DDAB assemble into a dense, hydrophobic shell around the PQD core. This shell acts as a physical barrier, shielding the ionic perovskite lattice from polar solvents (e.g., during photolithography) and environmental factors like moisture and oxygen [23] [20]. The bilateral use of DDAB with other molecules like TSPO1 ensures both top and bottom interfaces of the PQD film are protected, crucial for device longevity [21].

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

- Solvent Compatibility: The DDAB-passivated shell significantly improves stability in moderately polar solvents. However, aggressive polar solvents should still be avoided to prevent ligand desorption.

- Ligand Ratio Optimization: The molar ratio of DDAB to PQDs is critical. Insufficient DDAB leads to incomplete passivation, while excess DDAB can form insulating aggregates, hindering charge transport in electroluminescent devices. Perform a titration experiment to find the optimal ratio for your system.

- Storage and Handling: Always store purified DDAB-PQD inks in an inert atmosphere (glovebox) to prevent oxidation of the ligands and degradation of the PQD core.

Lead-free perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly cesium bismuth bromide (Cs₃Bi₂Br₉), have emerged as promising environmentally friendly alternatives to their lead-based counterparts for optoelectronic applications. Despite their non-toxic profile and reasonable optical properties, these materials face significant challenges in stability and performance that hinder their commercial implementation. The inherent structural instability, susceptibility to environmental degradation, and rapid recombination of photogenerated carriers pose substantial limitations.

Core-shell architecture fabrication has recently demonstrated remarkable potential for PQD surface protection, significantly enhancing both stability and functionality. This application note details recent advancements in stabilizing Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ through innovative core-shell designs, heterojunction construction, and eco-friendly synthesis protocols. We provide comprehensive experimental methodologies, characterization data, and practical implementation guidelines to facilitate research and development in this rapidly evolving field, with particular emphasis on scalable and sustainable approaches suitable for industrial translation.

Stabilization Strategies and Performance Metrics

Core-Shell and Heterojunction Architectures

Recent research has established multiple effective strategies for stabilizing Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ through heterostructure formation. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different architectural approaches.

Table 1: Performance characteristics of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ stabilization architectures

| Architecture Type | Synthesis Method | Key Performance Metrics | Application Potential | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/W₁₈O₄₉ S-scheme heterojunction | In-situ growth via thermal injection | CO production: 177.4 µmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹; Toluene oxidation: 1702.3 µmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ with 81% benzaldehyde selectivity | Photocatalytic CO₂ reduction coupled with selective organic oxidation | [25] |

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/FeS₂ hollow core-shell Z-scheme | Electrostatic self-assembly | H₂ evolution: 31.5 mmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ (112.6× higher than FeS₂ alone); AQY: 29.5% at 420 nm | Photothermal-photocatalytic H₂ production | [26] |

| Castor oil-passivated Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs | Solution processing in castor oil | PLQY: 21.2% (up to 53% with linoleic acid); Retention: 97.3% after 72 h environmental exposure | Leather anti-counterfeiting via fluorescent patterning | [27] |

| Fe-doped Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ | Facile solution doping | Bandgap reduction: 2.54 eV (pristine) to 1.78 eV (70% Fe doping); Structural transformation to Cs₂(Bi,Fe)Br₅ at 50% Fe | Bandgap-tunable optoelectronics | [28] |

Advanced Characterization Data

Comprehensive characterization of stabilized Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ structures reveals enhanced optical and electronic properties essential for application development.

Table 2: Characterization parameters of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉-based materials

| Material System | Bandgap (eV) | PL Emission | PLQY (%) | Stability Performance | Structural Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ | 2.54 (single crystal) | N/A | N/A | Resistivity: 1.79×10¹¹ Ω·cm; μτ = 5.12×10⁻⁴ cm²/V | 2D bilayered "defect" perovskite structure | [29] |

| CO-Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs | N/A | 430 nm (blue) | 21.2 (up to 53.0) | 97.3% FL intensity after 72 h | Surface passivation by castor oil fatty acids | [27] |

| Fe-doped Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ | 1.78 (70% Fe) | N/A | N/A | Phase transformation at high doping | Orthorhombic Cs₂(Bi,Fe)Br₅ at 50% Fe; CsFeBr₄ at 100% Fe | [28] |

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/W₁₈O₄₉ | Staggered alignment | N/A | N/A | Enhanced charge separation | S-scheme heterojunction with internal electric field | [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs Using Castor Oil

Principle: This protocol utilizes castor oil as both solvent and ligand source, replacing conventional organic solvents like octadecene, DMF, or DMSO. The fatty acid components (ricinoleic, oleic, and linoleic acids) act as effective passivating ligands, while the triglyceride structure provides a protective coating [27].

Materials:

- Cesium bromide (CsBr, 99.5%)

- Bismuth bromide (BiBr₃, ≥98%)

- Castor oil (CP grade)

- Octylamine (99%)

- Standard laboratory glassware

- Magnetic stirrer with heating capability

- Centrifuge

- UV-vis spectrophotometer

- Fluorometer

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 0.0426 g of CsBr and 0.0601 g of BiBr₃ in 10 mL of castor oil.

- Ligand Addition: Add 50 µL of octylamine to the solution as a co-ligand.

- Reaction: Stir the mixture at 25°C for 30-60 minutes until complete dissolution occurs.

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting solution at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove any undissolved aggregates.

- Storage: Collect the supernatant containing the Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs for immediate use or store in airtight containers protected from light.

Optimization Notes:

- The presence of conjugated double bonds in linoleic acid enhances PLQY up to 53%.

- Adjust reaction time and temperature to control particle size.

- For higher stability, consider post-synthetic cross-linking of the castor oil matrix.

Fabrication of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/FeS₂ Hollow Core-Shell Z-Scheme Heterojunctions

Principle: This protocol creates a Z-scheme heterojunction between Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ QDs and FeS₂ hollow nanospheres, enabling efficient charge separation while maintaining strong redox potentials. The hollow structure enhances light absorption through multiple reflections, and the FeS₂ component acts as a "heat island" for photothermal enhancement [26].

Materials:

- Pre-synthesized Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs

- FeS₂ hollow nanospheres (3-5 µm diameter)

- Ethanol (anhydrous)

- Toluene

- Electrostatic assembly chamber

- Ultrasonic bath

- Vacuum filtration setup

- SEM/TEM for characterization

Procedure:

- FeS₂ Activation: Treat FeS₂ hollow nanospheres with oxygen plasma for 10 minutes to enhance surface reactivity.

- Suspension Preparation: Create separate suspensions of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs (1 mg/mL in toluene) and activated FeS₂ (2 mg/mL in ethanol).

- Electrostatic Assembly: Combine the suspensions in a 5:1 volume ratio (PQDs:FeS₂) under continuous sonication for 30 minutes.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to stand for 2 hours to facilitate self-assembly through electrostatic interactions.

- Collection: Recover the heterostructures by vacuum filtration through a 0.2 µm PTFE membrane.

- Washing: Rinse three times with anhydrous ethanol to remove unbound PQDs.

- Drying: Dry under vacuum at 60°C for 6 hours before characterization or application.

Optimization Notes:

- The optimal loading ratio of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ to FeS₂ is approximately 5% by mass.

- Z-scheme charge transfer enhances separation efficiency while preserving redox capability.

- The hollow structure enables multiple light reflections, enhancing photothermal conversion.

Construction of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/W₁₈O₄₉ S-Scheme Heterojunctions

Principle: This protocol develops an S-scheme heterojunction through in-situ growth of Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ QDs on W₁₈O₄₉ nanobelts, creating an internal electric field that drives charge separation and enhances photocatalytic performance for coupled redox reactions [25].

Materials:

- Tungsten hexachloride (WCl₆)

- Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ precursor solution (from Protocol 3.1)

- Oleylamine

- 1-Octadecene

- High-temperature reaction flask

- Schlenk line

- Syringe pump

- Thermal injection apparatus

Procedure:

- W₁₈O₄₉ Nanobelt Synthesis: Heat WCl₆ (0.2 mmol) in a mixture of oleylamine (5 mL) and 1-octadecene (15 mL) at 300°C for 1 hour under argon atmosphere.

- Purification: Precipitate the formed W₁₈O₄₉ nanobelts with ethanol, centrifuge at 9000 rpm for 15 minutes, and redisperse in toluene.

- In-situ Growth: Inject Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ precursor solution (2 mL) into the W₁₈O₄₉ nanobelt suspension (5 mg/mL in toluene) at 180°C under vigorous stirring.

- Reaction: Maintain temperature at 180°C for 5 minutes to facilitate heterojunction formation.

- Collection: Cool the reaction mixture to room temperature, precipitate with ethyl acetate, and centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Washing: Wash twice with ethanol/ethyl acetate (1:1 v/v) mixture to remove unreacted precursors.

Optimization Notes:

- The S-scheme mechanism preserves strong redox potentials while enhancing charge separation.

- Oxygen vacancies in W₁₈O₄₉ promote visible light absorption through LSPR effects.

- Heterojunction exhibits bifunctional capability for simultaneous CO₂ reduction and toluene oxidation.

Visualization of Core-Shell Architectures and Charge Transfer Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Stabilization architecture strategies for Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ perovskites

Diagram 2: Eco-friendly synthesis workflow for Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents for Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ core-shell structure fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications | Alternative Options | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castor oil | Green solvent and ligand source | CP grade; High ricinoleic acid content | Olive oil (alternative green solvent) | [27] |

| Cesium bromide (CsBr) | Cesium precursor for perovskite structure | 99.5% purity; Anhydrous | Cs₂CO₃ (requires conversion to bromide) | [27] [29] |

| Bismuth bromide (BiBr₃) | Bismuth source for lead-free perovskite | ≥98% purity; Moisture-sensitive | Bi₂O₃ (with HBr conversion) | [27] [29] |

| Octylamine | Co-ligand for surface passivation | 99% purity; Acts as coordination ligand | Oleylamine (longer chain alternative) | [27] |

| FeS₂ hollow nanospheres | Photothermal core material | 3-5 µm diameter; Raspberry-like morphology | Other metal sulfides (CuS, ZnS) | [26] |

| W₁₈O₄₉ nanobelts | Semiconductor for heterojunctions | Ultra-thin; Oxygen vacancy-rich | Other WOₓ phases | [25] |

| Linoleic acid | High-performance ligand | Conjugated double bonds; Enhances PLQY | Oleic acid (standard ligand) | [27] |

Application Protocols

Leather Anti-Counterfeiting Implementation

Principle: Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs incorporated into leather matrices provide fluorescent patterning for authentication under UV excitation. The castor oil-based synthesis is particularly advantageous as it simultaneously lubricates collagen fibers while imparting anti-counterfeiting functionality [27].

Procedure:

- PQD Dispersion: Prepare a concentrated dispersion of CO-Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs in ethanol (5 mg/mL).

- Leather Pretreatment: Clean leather substrates with isopropanol and air-dry.

- Application: Apply PQD dispersion to leather using layer-by-layer self-assembly or patterned deposition.

- Fixation: Heat-treated at 60°C for 30 minutes to ensure adhesion.

- Verification: Examine under UV light (365 nm) to confirm bright blue fluorescent patterning.

Performance Metrics: Fluorescence retention >97% after 72 hours; visible patterning under UV excitation; minimal impact on leather physical properties.

Photocatalytic CO₂ Reduction Coupled with Toluene Oxidation

Principle: The S-scheme heterojunction in Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/W₁₈O₄₉ enables simultaneous CO₂ reduction to CO and selective toluene oxidation to benzaldehyde, creating a synergistic photoredox system that eliminates the need for sacrificial agents [25].

Procedure:

- Photocatalyst Preparation: Synthesize Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/W₁₈O₄₉ heterojunctions following Protocol 3.3.

- Reactor Setup: Place catalyst (20 mg) in a gas-tight photocatalytic reactor with quartz window.

- Gas Mixture: Introduce CO₂ (99.99%) to 0.5 atm pressure, then add toluene vapor (0.5 mmol) as electron donor.

- Irradiation: Illuminate with simulated solar light (AM 1.5G, 100 mW/cm²) for 4 hours.

- Product Analysis: Quantify CO formation by gas chromatography; analyze liquid products for benzaldehyde by HPLC.

Performance Metrics: CO production rate: 177.4 µmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹; Benzaldehyde selectivity: 81%; Stable performance over multiple cycles.

The strategic implementation of core-shell architectures and heterojunction designs represents a transformative approach for stabilizing lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ perovskites and enhancing their functional performance. The protocols detailed in this application note demonstrate that through eco-friendly synthesis routes, precise heterostructure control, and appropriate application-specific implementations, researchers can overcome the inherent limitations of these promising materials.

The combination of enhanced stability, tunable optoelectronic properties, and multifunctional capabilities positions these engineered perovskite systems as viable candidates for commercial applications ranging from anti-counterfeiting to energy conversion and environmental remediation. Continued refinement of these strategies, particularly focusing on scalability and long-term operational stability, will accelerate the adoption of lead-free perovskite technologies across diverse industrial sectors.

Fabrication Techniques and Emerging Biomedical Applications

Halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting materials for optoelectronic devices, notably light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Their appeal lies in exceptional properties including high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), narrow emission profiles, and readily tunable bandgaps, which collectively surpass the performance of conventional quantum dots (e.g., CdSe) in color purity and efficiency [2]. However, the widespread commercial application of PQDs is critically hindered by their intrinsic structural instability. The ionic nature of perovskite crystals makes them susceptible to rapid degradation under external stimuli such as moisture, oxygen, and heat [2].

The degradation primarily occurs through two mechanisms:

- Defect Formation via Ligand Dissociation: The organic ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) passivating the PQD surface are often weakly bound and can detach during purification or under ambient exposure. This creates unsaturated "dangling bonds" that act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching photoluminescence and initiating surface degradation [2].

- Vacancy Formation via Halide Migration: Due to low migration energy, halide ions within the perovskite lattice are highly mobile, leading to the formation of vacancies and interstitials. These defects facilitate irreversible decomposition and phase segregation [2].

Encapsulating individual PQDs within a robust silicon dioxide (SiO₂) shell to form a core/shell structure presents a highly promising strategy to mitigate these instabilities. The SiO₂ shell acts as a physical barrier, shielding the sensitive perovskite core from moisture and oxygen. Furthermore, a properly engineered shell can passivate surface defects, thereby preserving or even enhancing the optical properties of the PQDs [30] [31]. The sol-gel process, employing tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as the silica precursor, is the predominant method for constructing this protective architecture. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol and framework for achieving controlled, conformal SiO₂ shell growth on PQDs using TEOS, directly supporting thesis research on advanced core-shell nanostructures for PQD stabilization.

Scientific Principles: The Sol-Gel Chemistry of TEOS

The sol-gel process is a versatile wet-chemical technique for synthesing inorganic networks like silica at mild temperatures. The formation of a SiO₂ shell from TEOS proceeds through two fundamental reaction steps:

Hydrolysis: The alkoxide groups (OC₂H₅) in TEOS are replaced with hydroxyl groups (OH) in the presence of water, often facilitated by a catalyst (e.g., ammonia).

Reaction:

Si(OC₂H₅)₄ + 4H₂O → Si(OH)₄ + 4C₂H₅OHCondensation: The hydrolyzed monomers subsequently link together via dehydration or dealcoholation reactions, forming Si-O-Si bonds that constitute the silica network.

Reactions:

- Water-forming:

Si-OH + HO-Si → Si-O-Si + H₂O - Alcohol-forming:

Si-OH + (C₂H₅O)-Si → Si-O-Si + C₂H₅OH

- Water-forming:

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic pathway from TEOS to a solid silica network encapsulating a PQD core.

Controlling Shell Growth: The kinetics of hydrolysis and condensation are paramount for achieving a uniform, conformal shell rather than uncontrolled silica precipitation or particle aggregation. Key parameters influencing this control include:

- Catalyst Concentration (e.g., NH₄OH): Accelerates both reactions.

- Water-to-TEOS Molar Ratio: Governs the extent of hydrolysis.

- Reaction Temperature: Affects the reaction rates.

- PQD Surface Chemistry: Functional ligands on the PQD surface can mediate the initial condensation step, promoting heterogeneous nucleation of silica on the PQD core over homogeneous nucleation in the solution bulk [30] [31].

Experimental Protocol: A Standardized Procedure

This protocol outlines the synthesis of MAPbBr₃ (Methylammonium Lead Bromide) PQDs and their subsequent encapsulation via a modified Stöber method, suitable for hydrophobic PQDs.

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function/Significance | Example & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | PQD core precursor | ≥99.99% purity |

| Methylammonium Bromide (MABr) | PQD core precursor | ≥99.99% purity |

| n-Octylamine, Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligands for PQD synthesis & stabilization | Technical grade, 90% |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | SiO₂ shell precursor; forms Si-O-Si network via sol-gel | ≥99.0%, pure |

| (3-Aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTMS) | Silane coupling agent; mediates adhesion between PQD and SiO₂ | ≥97% |

| Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH) | Catalyst for TEOS hydrolysis and condensation | 28-30% NH₃ basis |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Solvent for PQD precursor dissolution | Anhydrous, 99.8% |

| Toluene | Solvent for PQD synthesis and silica coating | Anhydrous, 99.8% |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The synthesis and encapsulation process follows the workflow below, integrating both PQD formation and silica shell growth.

Part A: Synthesis of MAPbBr₃ PQD Cores [31]

- Dissolve 0.1 mmol MABr and 0.1 mmol PbBr₂ in 1 mL of DMF.

- Add 15 μL of n-octylamine and 10 μL of OA as ligands. Stir until completely dissolved.

- In a separate vial, add 1.7 mL of OA to 10 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring.

- Rapidly inject the precursor solution from Step 2 into the toluene/OA mixture.

- Stir the reaction for 30 seconds to 1 minute. The immediate appearance of a green emission under UV light indicates the formation of MAPbBr₃ PQDs.

Part B: Purification of PQDs

- Precipitate the PQDs by adding a polar anti-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate or acetone) and centrifuging at 8,000 RPM for 5 minutes.

- Decant the supernatant and redisperse the pellet in 5 mL of anhydrous toluene. Repeat this purification step once more.

Part C-D: Surface Priming with Silane Coupling Agent

- To the purified PQD solution, add a controlled amount of APTMS (e.g., 10-20 μL). The amine group of APTMS coordinates with the Pb²⁺ on the PQD surface, while the methoxysilane groups are available for reaction with TEOS.

- Stir the mixture for 1 hour to allow for complete ligand exchange/surface interaction.

Part E-F: Controlled TEOS Hydrolysis and Shell Growth

- Dilute a calculated volume of TEOS (e.g., 50-100 μL) in 1 mL of toluene and add it dropwise to the PQD reaction flask.

- Initiate the sol-gel process by injecting a small, controlled amount of ammonium hydroxide catalyst (e.g., 20-50 μL). The amount of water in the ammonium hydroxide solution is typically sufficient for the hydrolysis reaction.

- Allow the reaction to proceed with constant stirring for 2 to 6 hours at a temperature between 25°C and 40°C. Critical Insight: This step requires precise control. Slower growth at lower temperatures and catalyst concentrations favors the formation of a uniform, conformal shell.

Part G-H: Purification and Characterization

- Precipitate the resulting PQD@SiO₂ core/shell nanoparticles by adding acetone and centrifuging.

- Redisperse the purified product in toluene or ethanol for further characterization.

Optimization and Critical Parameter Analysis

Successful encapsulation is evidenced by high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) retention and stability in polar solvents. The following table synthesizes key optimization parameters based on experimental data.

Table 2: Optimization of Sol-Gel Synthesis Parameters for SiO₂ Shell Growth on PQDs

| Parameter | Impact/Effect on Shell Growth & PQD Stability | Optimal Range / Target |

|---|---|---|

| Molar Ratio (H₂O:TEOS) | Determines hydrolysis rate; low ratio leads to incomplete reaction, high ratio causes fast/uneven condensation [32]. | 4:1 to 10:1 |

| Catalyst (NH₄OH) Concentration | Increases hydrolysis & condensation rates; high concentration causes rapid silica particle formation instead of shell growth [30]. | 5-20 mM (in final reaction) |

| Reaction Temperature | Higher temperatures accelerate kinetics, potentially leading to rough, non-conformal shells; lower temperatures favor controlled growth [30]. | 25°C - 40°C |

| Silane Coupling Agent | Mediates interfacial bonding; improves shell uniformity and adhesion, preventing aggregation [30] [31]. | APTMS or APDEMS, 10-20 μL/mL |

| PQD Core Surface Ligands | Short, dense ligands improve silica nucleation density; long, bulky ligands (OA/OAm) hinder it and require exchange [2]. | Short-chain ligands (e.g., AET) or post-synthetic treatment |

| Target Performance Metric: PLQY Retention | Indicator of successful surface passivation and minimal defect introduction during shelling [31]. | >90% of initial PQD PLQY |

| Target Performance Metric: Stability in Polar Solvent | Direct measure of the shell's protective barrier function [31]. | >95% PL intensity maintained after 1 hour in water/ethanol |

Advanced Applications and Material Characterization

The PQD@SiO₂ core/shell structures fabricated via this protocol exhibit markedly enhanced performance characteristics crucial for practical applications:

- Stability Enhancement: Silica-encapsulated MAPbBr₃ PQDs maintain over 95% of their initial photoluminescence (PL) intensity after 60 minutes of water exposure or 120 minutes of UV exposure, whereas unprotected PQDs degrade significantly [2] [31]. The hydrophobic shell formed by using specific silanes like APDEMS further enhances stability in polar environments [31].

- Optoelectronic Properties: The SiO₂ shell effectively passivates surface defects, leading to high PLQY. Core/shell structures have been reported with a narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM) and a PLQY as high as 96.5% [31].

- Application in Devices: The improved robustness and retained high efficiency make these materials ideal emitters for next-generation displays (PeLEDs) and other optoelectronic devices [2] [30].

The sol-gel synthesis using TEOS provides a robust and controllable pathway for constructing protective SiO₂ shells on fragile PQDs. The critical success factors are the precise management of reaction kinetics and the use of silane coupling agents to ensure homogeneous, conformal shell growth. The resultant core/shell structures address the primary limitation of PQDs—their instability—while preserving their exceptional emissive properties, thereby directly enabling their integration into commercial devices.

Future research directions for thesis work should explore:

- Advanced Silane Chemistry: Investigating a wider library of silane coupling agents (e.g., mercapto-, vinyl-functionalized) to achieve finer interfacial control and novel surface functionalities.

- Doped Silica Matrices: Exploring the incorporation of other metal cations into the silica matrix to modify its refractive index or add new functionalities [33].

- Automated High-Throughput Synthesis: Implementing platforms like the Science-Jubilee system [32] to rapidly explore the vast multi-parameter synthesis space and identify optimal conditions with unprecedented efficiency.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation and Surface Engineering for Core-Shell PQDs

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly lead halide perovskites (ABX3, where A = Cs+, MA+, FA+; B = Pb2+; X = Br-, Cl-, I-), have emerged as promising semiconductor nanomaterials for advanced optoelectronic applications due to their exceptional photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs up to 97.64%), tunable emission across the visible spectrum (360–710 nm), high color purity with narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM ~20 nm), and facile synthesis processing [34] [35]. Despite these advantageous properties, their practical implementation has been limited by intrinsic instability under environmental stressors including moisture, heat, and polar solvents, along with potential lead toxicity concerns [34] [31].

Core-shell nanostructure engineering has proven to be an effective strategy for enhancing PQD stability while maintaining their exceptional optical properties. This approach involves encapsulating the perovskite core within a protective shell, typically composed of materials like silica (SiO2), which creates a physical barrier against degrading elements [31] [36]. The development of ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) synthesis methods has enabled efficient one-step formation of these core-shell structures, significantly advancing the commercial viability of PQDs for applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), displays, and biomedical technologies [31] [37].

Core-Shell PQD Synthesis: Principles and Methodologies

Fundamentals of Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation

Ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) is a solution-phase synthesis technique that operates at room temperature and utilizes solvent miscibility to induce instantaneous crystallization of PQDs. The method capitalizes on the solubility disparity of perovskite precursors in polar versus non-polar solvents. In standard LARP procedures, perovskite precursors dissolved in a polar solvent (typically N,N-dimethylformamide, DMF) are rapidly injected into a vigorously stirring non-polar solvent (typically toluene) containing stabilizing ligands [37] [38].

This abrupt change in solvent environment reduces the solubility of the perovskite material, triggering rapid nucleation and growth of quantum-confined nanocrystals. Surface-bound ligands, including oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA), simultaneously coordinate with emerging crystal surfaces to control growth, provide colloidal stability, and passivate surface defects [37]. The LARP technique has been successfully adapted for synthesizing various PQD architectures including quantum dots, nanorods, and nanoplatelets with precise control over composition and optical properties [38].

Advanced LARP Techniques for Core-Shell Structures

Recent innovations have extended conventional LARP methodology to enable single-step formation of core-shell PQDs through modified approaches:

Split-Ligand Mediated Reprecipitation (S-LMRP): This technique utilizes amine-functionalized silane precursors (e.g., APDEMS - 3-aminopropyl(diethoxy)methylsilane) that serve dual roles as surface ligands and silica shell precursors. During PQD formation, these silane ligands hydrolyze and condense to form a protective SiO2 shell simultaneously with perovskite core crystallization [31]. This one-pot process eliminates the need for post-synthetic ligand exchange and protects the sensitive perovskite core from degradation during shell formation.

Modified LARP with Etching Inhibition: For all-inorganic CsPbBr3 PQDs, introducing oleic acid into the anti-solvent toluene effectively inhibits the surface etching effect commonly caused by aminosilane precursors like APTES (3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane). This modification enables the synthesis of CsPbBr3@SiO2 nanoparticles with enhanced photoluminescence quantum yields (90-100%) and significantly improved stability in thermal and polar solvent environments [36].

Table 1: Comparison of LARP-Based Core-Shell Synthesis Methods

| Method | Key Innovation | PQD System | PLQY | Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-LMRP | One-step core/shell formation using functionalized silanes | MAPbBr3@SiO2 | 96.5% | Enhanced dispersibility; stability in polar solvents, heat, and light [31] |

| Modified LARP with Etching Inhibition | OA introduction to prevent APTES etching | CsPbBr3@SiO2 | 90-100% | Superior thermal and polar solvent stability [36] |

| Standard LARP | Basic solvent-induced crystallization | MAPbX3 QDs | ~92.7% | Moderate stability requiring further encapsulation [37] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: One-Step Core/Shell MAPbBr3@SiO2 QDs via S-LMRP

Principle: This protocol utilizes APDEMS as a multifunctional ligand that controls PQD growth while simultaneously undergoing hydrolysis and condensation to form a protective silica shell, creating core/shell structures in a single step without additional ligand treatment [31].

Materials:

- Methylammonium bromide (MABr, 99.99%)

- Lead bromide (PbBr2, 99.99%)

- n-octylamine (99%)

- 3-aminopropyl(diethoxy)methylsilane (APDEMS, 97%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, ≥99.9%)

- Toluene (99.8%)

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve MABr (0.1 mmol), PbBr2 (0.1 mmol), and n-octylamine (15 μL) in 1 mL of DMF. Add APDEMS (50 μL) as the silica precursor to the mixture.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Transfer toluene (10 mL) containing OA (1.7 mL) to a clean vial under vigorous stirring at room temperature.

- Nanocrystal Formation: Rapidly inject the precursor solution (200 μL) into the toluene/OA mixture. Immediate color development indicates PQD formation.

- Shell Formation: Allow the reaction to proceed under continuous stirring for 10 minutes to complete silica shell formation through hydrolysis and condensation of APDEMS.

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting dispersion at 4,500 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant and redisperse the core/shell QDs in fresh toluene for characterization and application.

Key Parameters:

- APDEMS quantity critically determines shell thickness and optical properties

- Reaction must be conducted under ambient atmosphere without base conditions

- OA concentration in toluene prevents aggregation and ensures monodisperse QDs

Protocol 2: CsPbBr3@SiO2 Nanoparticles via Modified LARP

Principle: This method introduces oleic acid into the anti-solvent to suppress the etching effect of APTES on CsPbBr3 nanocrystals, enabling formation of stable core/shell structures with near-unity PLQY [36].

Materials:

- Cesium bromide (CsBr)

- Lead bromide (PbBr2)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- Oleylamine (OLA, 90%)

- (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, 97%)

- 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- DMF (≥99.9%)

- Toluene (99.8%)

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve CsBr (0.1 mmol) and PbBr2 (0.1 mmol) in 1 mL of DMF with OLA (50 μL) and OA (50 μL) as coordinating ligands.

- Anti-Solvent Preparation: Mix toluene (10 mL) with OA (1.0 mL) and APTES (50 μL) in a reaction vial under vigorous stirring.

- Injection and Nucleation: Rapidly inject the precursor solution (200 μL) into the anti-solvent mixture. Immediate green photoluminescence under UV light indicates CsPbBr3 nanocrystal formation.

- Silica Shell Growth: Continue stirring for 30 minutes to facilitate complete silica coating through APTES hydrolysis and condensation.

- Purification and Collection: Centrifuge the resulting nanoparticles at 5,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Redisperse the purified CsPbBr3@SiO2 nanoparticles in non-polar solvents (toluene or hexane) for further use.

Optimization Notes:

- OA:APTES ratio must be optimized to balance etching inhibition and shell growth

- In situ time-dependent photoluminescence measurements can monitor formation kinetics

- Optimal ligand ratios yield uniform nanocrystals with size around 10.17 ± 1.6 nm [36]

Surface Engineering and Stabilization Strategies

Surface Chemistry and Ligand Interactions

The large surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs makes surface chemistry a critical determinant of their optoelectronic properties and environmental stability. Surface engineering approaches for core-shell PQDs primarily focus on:

Defect Passivation: Coordinating ligands including oleic acid, oleylamine, and alkylammonium halides bind to surface sites, reducing non-radiative recombination centers and enhancing PLQY. In core-shell structures, these ligands additionally facilitate interfacial compatibility between the perovskite core and silica shell [35] [31].

Surface Functionalization: Aminosilane ligands (APDEMS, APTES) serve dual purposes as surface modifiers and silica precursors. Their amine groups coordinate with perovskite surfaces while alkoxy silane groups undergo hydrolysis and condensation to form protective SiO2 shells [31] [36].

Hydrophobic Engineering: Silica shells derived from methyl-functionalized silanes (e.g., APDEMS) create hydrophobic surfaces with CH3 groups, significantly enhancing dispersibility in non-polar matrices and providing resistance to moisture-induced degradation [31].

Compositional Engineering for Enhanced Stability