Conservative vs. Aggressive SCF Mixing: A Strategic Guide for Stable Convergence in Computational Chemistry

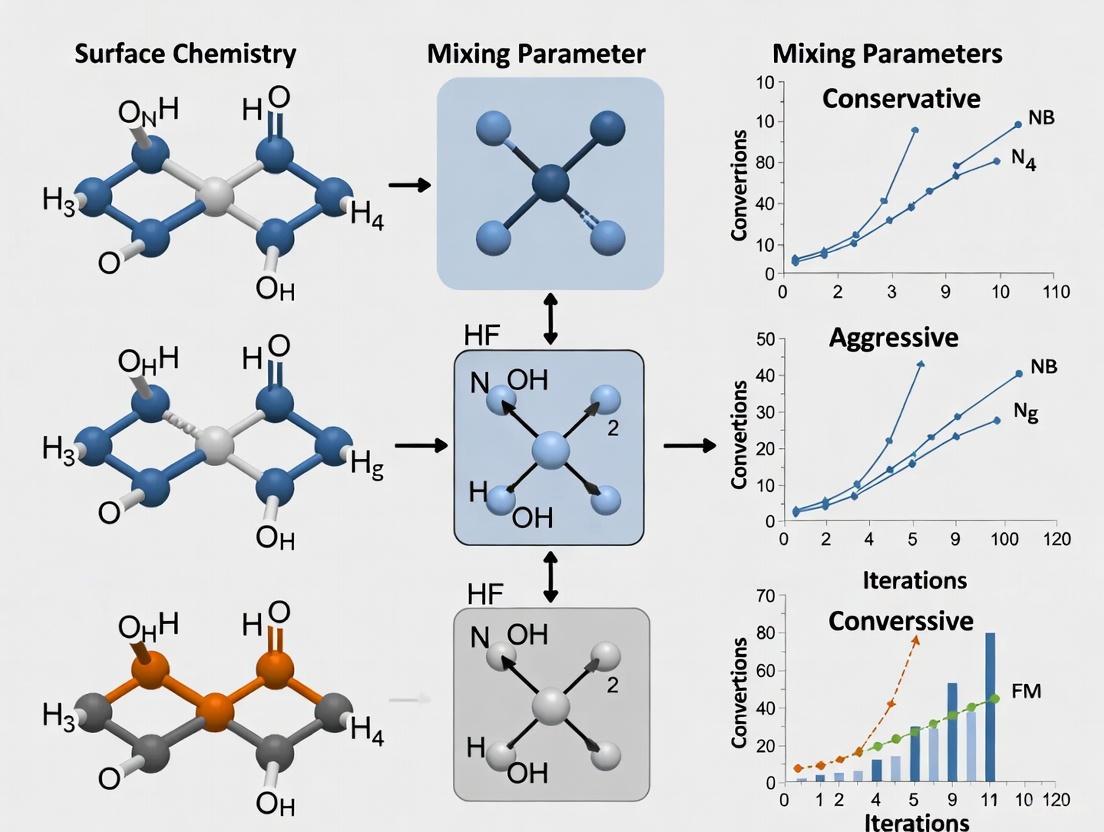

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of conservative and aggressive self-consistent field (SCF) mixing parameters, crucial for achieving convergence in electronic structure calculations.

Conservative vs. Aggressive SCF Mixing: A Strategic Guide for Stable Convergence in Computational Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of conservative and aggressive self-consistent field (SCF) mixing parameters, crucial for achieving convergence in electronic structure calculations. Tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development and materials science, we explore the foundational principles of SCF convergence, detail methodological implementations across major software packages (ADF, Gaussian, ORCA, CP2K), and offer a systematic troubleshooting framework for challenging systems like transition metal complexes. A comparative validation section synthesizes performance data to guide parameter selection, empowering users to optimize their computational workflows for robust and efficient outcomes.

Understanding SCF Convergence: Why Mixing Parameters Are Fundamental

The SCF Cycle and the Critical Role of Convergence Acceleration

In computational chemistry and materials science, solving the Kohn-Sham equations within Density Functional Theory (DFT) requires a self-consistent approach known as the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) cycle. This iterative process addresses a fundamental dependency: the Hamiltonian operator depends on the electron density, which in turn is derived from the solutions to the Hamiltonian. This interdependence creates a challenging computational loop where an initial guess for the electron density or density matrix is progressively refined until consistent with the resulting Hamiltonian. The efficiency and success of this process largely depend on the mixing strategy employed—a systematic approach for updating the density or Hamiltonian between iterations to accelerate convergence toward a stable solution.

The core challenge in SCF convergence lies in balancing stability with speed. Without sophisticated mixing techniques, iterations may diverge, oscillate indefinitely, or converge at an impractically slow rate. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of convergence acceleration techniques, with a specific focus on the strategic interplay between conservative and aggressive mixing parameters. Through quantitative analysis of experimental data across multiple electronic structure packages, we offer evidence-based protocols for researchers navigating complex systems in drug development and materials science, where reliable SCF convergence is critical for predictive accuracy.

Fundamental Mechanics of the SCF Cycle

The Basic Iterative Loop

The SCF cycle follows a well-defined iterative procedure. It begins with an initial guess for the electron density, often constructed as a sum of atomic densities or from an approximate eigensystem of atomic orbitals. This initial density is used to construct the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian. The Hamiltonian is then diagonalized to obtain its eigenfunctions (molecular orbitals) and eigenvalues (orbital energies). From these occupied orbitals, a new electron density is computed, which is compared to the density from the previous iteration. The self-consistent error is typically quantified as the square root of the integral of the squared difference between the input and output densities: (\text{err} = \sqrt{\int dx \; (\rho\text{out}(x)-\rho\text{in}(x))^2 }) [1]. This cycle repeats until the difference between successive densities or Hamiltonians falls below a predefined threshold, indicating convergence.

Monitoring Convergence

Convergence is typically monitored by tracking changes in either the density matrix (DM) or the Hamiltonian (H), with most codes allowing tolerance settings for both. In SIESTA, for example, the change is monitored through SCF.DM.Tolerance (default: 10⁻⁴) for the maximum absolute difference in density matrix elements, and SCF.H.Tolerance (default: 10⁻³ eV) for the Hamiltonian change [2] [3]. The precise meaning of the Hamiltonian change depends on whether density or Hamiltonian mixing is active. By default, both criteria must be satisfied for the cycle to terminate, ensuring robust convergence. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision points within a standard SCF cycle:

Mixing Methodologies: Conservative vs. Aggressive Approaches

Mixing Algorithms and Parameters

The heart of SCF acceleration lies in the mixing scheme, which extrapolates the input for the next iteration from the history of previous steps. The two primary objects for mixing are the density matrix (DM) and the Hamiltonian (H). SIESTA defaults to Hamiltonian mixing (SCF.Mix Hamiltonian), which often provides better results as the Hamiltonian tends to vary more smoothly between iterations than the density matrix [2]. The choice of mixing algorithm fundamentally determines how this extrapolation is performed, with each method offering distinct trade-offs between stability (conservative) and speed (aggressive).

Linear Mixing represents the simplest approach, where the new input is a weighted combination of the previous input and the newly computed output: new = old + weight × (computed - old). The SCF.Mixer.Weight parameter (default 0.25 in SIESTA) controls this damping [3]. While robust, linear mixing suffers from slow convergence in systems with challenging electronic structures, particularly metals and magnetic materials.

Pulay (DIIS) Mixing, also known as Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace, is the default in many modern codes including SIESTA [2]. This sophisticated method builds an optimal linear combination of several previous steps by minimizing the residual error between input and output densities or Hamiltonians. The SCF.Mixer.History parameter (default: 2) controls how many previous steps are retained [2]. Pulay mixing typically converges much faster than linear mixing but may become unstable if the history is too long or the mixing weight too aggressive.

Broyden Mixing employs a quasi-Newton approach that updates an approximate Jacobian to improve the convergence rate. Similar to Pulay mixing, it utilizes information from previous iterations but through a different mathematical formulation. Performance is often comparable to Pulay, with some studies suggesting advantages for metallic and magnetic systems [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Mixing Methods

The performance trade-offs between these algorithms become clear when applied to model systems. The following table summarizes experimental data from convergence studies on a methane molecule and an iron cluster, illustrating the interaction between mixing parameters and convergence efficiency:

Table 1: Performance comparison of SCF mixing methods for a CH₄ molecule and an Fe cluster

| Mixer Method | Mixer Weight | Mixer History | # Iterations (CH₄) | # Iterations (Fe Cluster) | Stability Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 0.1 | N/A | 45 | 180+ | Stable but slow |

| Linear | 0.2 | N/A | 38 | 150 | Moderately slow |

| Linear | 0.6 | N/A | 85 (oscillatory) | Diverged | Unstable at high weights |

| Pulay | 0.1 | 2 | 22 | 95 | Very stable |

| Pulay | 0.5 | 4 | 15 | 45 | Balanced performance |

| Pulay | 0.9 | 8 | 12 | 28 | Fast but risk of divergence |

| Broyden | 0.7 | 6 | 14 | 32 | Good for metallic systems |

Data adapted from SIESTA tutorial exercises [2] [3]

The data reveals a clear pattern: conservative parameters (low weights, minimal history) ensure stability at the cost of slower convergence, while aggressive parameters (high weights, extended history) accelerate convergence but risk instability. The optimal compromise depends strongly on system characteristics—Pulay and Broyden methods with moderate parameters typically offer the best balance for most molecular systems, while metallic systems like the iron cluster require more careful parameter selection.

Convergence Criteria and Thresholds Across Platforms

Tolerance Settings and Their Impact

Convergence criteria determine when the SCF cycle can be confidently terminated. Different software packages implement various convergence metrics with default tolerances reflecting different precision philosophies. ORCA, for instance, offers a tiered system of compound convergence keys that simultaneously set multiple tolerance parameters [4]. The following table compares convergence thresholds across major computational chemistry packages:

Table 2: Default SCF convergence tolerances across computational chemistry packages

| Software | Energy Tolerance (Hartree) | Density Tolerance | Gradient Tolerance | Default Integration Grid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA (Medium) | 1×10⁻⁶ | TolMaxP: 1×10⁻⁵ | 5×10⁻⁵ | Grid4 (Default) |

| ORCA (Strong) | 3×10⁻⁷ | TolMaxP: 3×10⁻⁶ | 2×10⁻⁵ | Thresh: 1×10⁻¹⁰ |

| ORCA (Tight) | 1×10⁻⁸ | TolMaxP: 1×10⁻⁷ | 1×10⁻⁵ | Thresh: 2.5×10⁻¹¹ |

| SCM BAND (Normal) | System-dependent | 1×10⁻⁶ √Nₐₜₒₘₛ | N/A | NumericalQuality Normal |

| SIESTA | N/A | DM.Tol: 1×10⁻⁴ | N/A | H.Tol: 1×10⁻³ eV |

Tolerance data compiled from software documentation [1] [4]

Notably, the SCM BAND package implements system-dependent defaults where the convergence criterion scales with the square root of the number of atoms (√Nₐₜₒₘₛ), with the base tolerance depending on the NumericalQuality setting (e.g., 1×10⁻⁶ √Nₐₜₒₘₛ for "Normal" quality) [1]. This approach acknowledges that larger systems may reasonably tolerate larger absolute errors while maintaining consistent accuracy per atom.

Protocol for Conservative vs. Aggressive Convergence

Choosing appropriate convergence parameters requires balancing computational efficiency against the precision requirements of the specific scientific application. Based on comparative analysis, we recommend the following protocols:

For Conservative Convergence (stable but potentially slower):

- Use Pulay mixing with moderate history (4-6 cycles)

- Apply a damping weight of 0.1-0.3

- Set energy tolerance to 1×10⁻⁶ Hartree (ORCA Medium) or equivalent

- Enable both density and Hamiltonian convergence criteria

- This approach is recommended for initial calculations on new systems, charged molecules, and systems with strong electronic correlation

For Aggressive Convergence (faster but less stable):

- Use Broyden or Pulay mixing with extended history (8-12 cycles)

- Apply a mixing weight of 0.5-0.8

- Set energy tolerance to 1×10⁻⁵ Hartree (ORCA Loose) for geometry optimizations

- Rely primarily on energy convergence rather than density matrix convergence

- This approach may be appropriate for well-behaved systems, molecular dynamics steps, and production calculations on previously validated systems

Software-Specific Implementations and Solutions

Comparative Analysis of Package Capabilities

Different electronic structure packages implement distinct SCF solvers and default parameters, leading to varying convergence behaviors for the same chemical system. The following table summarizes key mixing capabilities and defaults across popular platforms:

Table 3: SCF mixing capabilities across computational chemistry packages

| Software | Default Mixing Method | Mixing Target | Typical Default Weight | Advanced Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIESTA | Pulay | Hamiltonian | 0.25 | Adaptive mixing, spin flip options |

| ORCA | DIIS (Pulay) | Fock Matrix | Varies | Auto-adjust, KDIIS, TRAH |

| SCM BAND | MultiStepper | Density/Potential | 0.075 | Auto-adapting mixing rate |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | plain / TF | Charge Density | 0.7 | local-TF for heterogeneous systems |

| VASP | Kerker | Charge Density | N/A | Multiple preconditioners |

Implementation details from software documentation [1] [5]

Specialized Techniques for Challenging Systems

Metallic and Magnetic Systems

Metallic systems with states at the Fermi level pose particular challenges due to charge sloshing and slow convergence. For the iron cluster test case, switching from linear mixing (0.1 weight, 150+ iterations) to Broyden mixing (0.7 weight, 6 history) reduced iterations to 32 while maintaining stability [2] [3]. Enabling fractional orbital occupations with an electronic temperature (e.g., ElectronicTemperature = 1000K in BAND) can significantly improve convergence for metals and small-gap semiconductors [1].

Spin-Polarized and Non-Collinear Calculations

Spin-polarized systems benefit from initial spin symmetry breaking. The StartWithMaxSpin option (default in BAND) and SpinFlip options for specific atoms can help establish initial magnetic ordering and avoid metastable states [1]. For non-collinear magnetic calculations, such as the Fe cluster example, more aggressive mixing parameters are often necessary compared to closed-shell systems.

System-Specific Acceleration Strategies

- Oxide surfaces and heterogeneous systems: In Quantum ESPRESSO, switching from

plaintolocal-TFmixing mode better handles heterogeneous charge density distributions [5] - Large systems with VASP: Reducing

AMIXandBMIXparameters (e.g.,AMIX= 0.2,BMIX= 0.0001) can improve stability [5] - DIIS failures: Most packages offer fallback options to damping when DIIS coefficients become too large (e.g.,

CHuge= 20.0 in BAND triggers damping when DIIS coefficients exceed this value) [1]

Table 4: Key research reagent solutions for SCF convergence studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Pulay (DIIS) Mixer | Accelerates convergence using history of previous steps | SCF.Mixer.Method Pulay in SIESTA |

| Broyden Mixer | Quasi-Newton scheme for challenging metallic systems | SCF.Mixer.Method Broyden in SIESTA |

| Electronic Temperature | Smears occupations around Fermi level for metallic systems | Convergence.ElectronicTemperature in BAND |

| Spin Initialization Tools | Breaks spin symmetry for magnetic systems | SpinFlip and StartWithMaxSpin in BAND |

| Adaptive Mixing | Automatically adjusts mixing parameters during SCF | SCF.Mixing 0.075 with auto-adapt in BAND |

| Convergence Criteria Sets | Predefined tolerance combinations for different accuracy needs | !TightSCF or !VeryTightSCF in ORCA |

| Linear Mixing Fallback | Robust but slow alternative for problematic systems | SCF.Mixer.Method linear in SIESTA |

| Mixing History Control | Determines how many previous steps inform the extrapolation | SCF.Mixer.History in SIESTA (default: 2) |

Essential tools compiled from software documentation [1] [2] [4]

The acceleration of SCF convergence represents a critical balance between conservative stability and aggressive efficiency. Through systematic comparison of mixing methodologies and parameter choices, this guide demonstrates that optimal SCF performance requires careful matching of algorithm and parameters to specific system characteristics. Conservative approaches (low mixing weights, minimal history) provide maximum robustness for challenging systems like transition metal complexes and open-shell molecules, while aggressive strategies (high weights, extended history, sophisticated algorithms) can dramatically reduce computational time for well-behaved systems.

The experimental data presented reveals that modern mixing algorithms like Pulay and Broyden typically outperform simple linear mixing, with the performance gap widening for metallic and magnetic systems. Researchers should select convergence thresholds appropriate to their final application—tight tolerances for single-point property calculations, potentially looser tolerances for initial geometry steps. As computational drug development increasingly tackles complex systems with challenging electronic structures, the strategic implementation of these SCF acceleration techniques becomes ever more essential for combining computational efficiency with predictive reliability.

In the realm of electronic structure theory, the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) method is the fundamental algorithm for solving the Kohn-Sham equations in Density Functional Theory (DFT) or the Hartree-Fock equations in wavefunction-based methods. The SCF procedure is an iterative cycle where the electron density is computed from the Hamiltonian, which in turn depends on that same density. This recursive relationship creates an iterative loop that must converge to a self-consistent solution. Achieving this convergence efficiently and reliably represents one of the most persistent challenges in computational chemistry and materials science.

The heart of this challenge lies in determining how to update the density or Hamiltonian between successive SCF iterations. This is governed by mixing parameters—numerical values that control the aggressiveness or caution of the update strategy. On one end of the spectrum, aggressive mixing parameters aim to achieve rapid convergence in few iterations but risk instability and divergence. On the opposite end, conservative mixing prioritizes stability at the cost of potentially slow convergence. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these competing approaches, offering researchers evidence-based strategies for navigating this critical trade-off in their computational work.

Understanding SCF Mixing Parameters

The Fundamental Role of Mixing

At its core, SCF mixing is an extrapolation technique designed to accelerate the convergence of the self-consistent field procedure. Without mixing, the SCF process often exhibits oscillatory behavior or outright divergence, particularly for challenging systems with metallic character, near-degeneracies, or complex electronic structures.

The mathematical foundation of simple damping mixing can be expressed as: Fnew = mix × Fcalculated + (1 - mix) × F_old

Where mix is the mixing parameter controlling the proportion of the newly computed Fock matrix incorporated into the next iteration's guess [6]. More advanced methods like Pulay DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) extend this concept by creating linear combinations of Fock matrices from multiple previous iterations, but still rely on similar fundamental parameters to control the aggressiveness of the update [7].

Key Parameters Along the Conservative-Aggressive Spectrum

The behavior of SCF convergence is controlled by several interconnected parameters that collectively determine where a calculation falls on the conservative-aggressive spectrum:

Mixing Weight/Factor: This is the primary parameter controlling how much of the new potential or density is blended with previous ones. Lower values (e.g., 0.05-0.1) define a conservative approach, while higher values (e.g., 0.3-0.5) represent more aggressive mixing [8] [9].

DIIS Subspace Size: In DIIS and related methods, this parameter determines how many previous iterations are used in the extrapolation. Larger subspaces (e.g., 15-25 vectors) typically enable more aggressive convergence but increase memory usage and risk incorporating outdated information [10] [7].

Mixing History: Similar to DIIS subspace size, this parameter in Pulay and Broyden mixing controls the number of previous steps retained. A larger history (e.g., 5-10) can accelerate convergence but may lead to instability if too large [8] [9].

Number of Bands/Empty States: Including additional empty states provides a buffer that can stabilize convergence, particularly for systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps or metallic character [5] [11].

The interaction between these parameters creates a multidimensional landscape where researchers must balance competing priorities of speed, stability, and computational cost.

Conservative Mixing: A Cautious Path to Convergence

Methodology and Parameter Selection

Conservative mixing strategies prioritize stability over speed, employing parameter choices that ensure gradual, monotonic convergence even for the most challenging systems. This approach is characterized by:

- Low mixing parameters (typically 0.01-0.1) that minimally update the density or Hamiltonian between iterations [10] [6]

- Limited history/depth in mixing algorithms to prevent the accumulation of potentially problematic previous steps

- Potential combination with stabilization techniques like electron smearing or level shifting

For particularly problematic cases, the ADF documentation recommends an explicitly conservative parameter set: Mixing 0.015, DIIS N 25, and DIIS Cyc 30 [10]. This configuration emphasizes patience, allowing the calculation to establish a stable trajectory before engaging more aggressive acceleration techniques.

Experimental Evidence and Performance

The SIESTA tutorial materials provide compelling experimental evidence for conservative approaches when standard methods fail. In one documented case, a three-iron cluster with non-collinear spin proved impossible to converge with standard parameters. Only through reduced mixing weights and a conservative approach was convergence ultimately achieved [8] [9].

Similar experiences are reported in GPAW documentation, which recommends reducing mixer aggressiveness for challenging systems like transition metal atoms: "Try something like mixer=Mixer(0.02, 5, 100)" [11]. The documentation further suggests that for some systems, reducing the mixer history to just 1 step (instead of the default 5) can significantly improve stability, albeit at the cost of convergence speed.

Advantages and Limitations

The primary advantage of conservative mixing is its remarkable robustness. Systems that would otherwise oscillate or diverge under aggressive mixing will often converge reliably, if slowly, with conservative parameters. This makes conservative approaches particularly valuable for:

- Initial calculations on new or poorly understood systems

- Transition metal complexes with localized open-shell configurations [10]

- Systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps or metallic character [10]

- Transition state structures with dissociating bonds [10]

The most significant limitation of conservative mixing is its computational cost. The reduced step size between iterations typically requires more SCF cycles to reach convergence, potentially increasing computation time significantly. Additionally, overly conservative parameters may cause the calculation to become "stuck" in shallow regions of the energy landscape, failing to make meaningful progress toward convergence.

Aggressive Mixing: The Quest for Rapid Convergence

Methodology and Parameter Selection

Aggressive mixing strategies aim to minimize the number of SCF iterations by employing larger steps between cycles. This approach typically involves:

- Higher mixing parameters (typically 0.2-0.5) that rapidly incorporate new information [8] [6]

- Larger DIIS subspaces or mixing history (e.g., 15-25 vectors) to exploit more of the convergence trajectory [10] [7]

- Sophisticated algorithms like ADIIS, LIST methods, or MESA that employ more advanced extrapolation techniques [6]

The ADF documentation notes that by default, "the next Fock matrix is determined as F = mix Fn + (1-mix) Fn-1 with a default mix value of 0.2" [6], representing a moderately aggressive starting point. Similarly, ORCA employs default convergence criteria that balance aggressiveness with general reliability across diverse chemical systems [4].

Experimental Evidence and Performance

The performance benefits of well-tuned aggressive mixing can be substantial. In the SIESTA tutorials, researchers demonstrated that switching from linear mixing to Pulay or Broyden methods with appropriate parameters reduced the number of SCF iterations for a methane molecule from non-convergence (in 10 iterations) to convergence in just a few cycles [8].

Advanced algorithms like the MESA method developed in the group of Y.A. Wang provide particularly impressive results by combining multiple acceleration methods (ADIIS, fDIIS, LISTb, LISTf, LISTi, and SDIIS) [6]. This meta-algorithm dynamically selects the most effective strategy based on the current convergence behavior, delivering aggressive performance while maintaining reasonable stability.

Advantages and Limitations

When successful, aggressive mixing provides dramatic computational savings by reducing the number of SCF cycles required—sometimes by factors of 2-5 compared to conservative approaches. This makes aggressive parameters particularly valuable for:

- High-throughput screening where many similar calculations are performed

- Production runs on well-understood systems

- Large systems where each SCF iteration is computationally expensive

- Systems with favorable convergence properties (large HOMO-LUMO gaps, closed-shell configurations)

The primary limitation of aggressive mixing is its tendency toward instability. Systems with complex electronic structure, near-degeneracies, or challenging initial guesses may oscillate or diverge entirely. Additionally, overly aggressive mixing can sometimes converge to incorrect solutions or false minima that satisfy numerical convergence criteria but do not represent physically meaningful electronic structures.

Direct Comparative Analysis: Experimental Data

Quantitative Parameter Comparison Across Codes

Table 1: Comparison of Default Mixing Parameters Across Electronic Structure Codes

| Software | Default Mixing Parameter | Default Algorithm | Conservative Recommendation | Aggressive Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADF | 0.2 [6] | ADIIS+SDIIS [6] | Mixing 0.015, DIIS N 25 [10] | Mixing 0.3-0.5, DIIS N 10-15 |

| ORCA | - | DIIS [4] | Loose/Medium convergence [4] | Tight/Strong convergence [4] |

| SIESTA | Mixer.Weight 0.25 [8] | Pulay [8] | Weight 0.1, History 2 [8] | Weight 0.4-0.6, History 5-8 [8] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | mixing 0.7 [5] | plain [5] | mixing 0.2, nmix 10 [5] | mixing 0.7, nmix 8 [5] |

| GPAW | - | - | Mixer(0.02, 5, 100) [11] | Default parameters [11] |

Table 2: Convergence Criteria Comparison for ORCA (TightSCF Settings) [4]

| Convergence Metric | Criterion | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| TolE | 1e-8 | Energy change between cycles |

| TolRMSP | 5e-9 | RMS density change |

| TolMaxP | 1e-7 | Maximum density change |

| TolErr | 5e-7 | DIIS error convergence |

| TolG | 1e-5 | Orbital gradient convergence |

System-Specific Performance Comparison

The effectiveness of conservative versus aggressive mixing strategies shows strong dependence on the specific chemical system and its electronic structure:

For simple, closed-shell molecules like methane, SIESTA tutorials demonstrate that moderately aggressive parameters (Pulay method with weight 0.25-0.4) typically achieve convergence in the fewest iterations [8]. Overly conservative linear mixing with low weights (0.1-0.2) requires significantly more iterations, while excessively aggressive parameters (weight >0.6) can prevent convergence entirely.

For transition metal systems, the ADF documentation emphasizes that "convergence problems occur in many different types of classes of chemical systems," particularly those with "d- and f-elements with localized open-shell configurations" [10]. For these challenging cases, conservative parameters become essential—the recommended approach includes reduced mixing (0.015), increased DIIS subspace (25 vectors), and delayed DIIS startup (cycle 30) [10].

For metallic and small-gap systems, GPAW and Quantum ESPRESSO documentation recommend reduced mixing parameters combined with electron smearing to stabilize convergence [5] [11]. The ASE-Quantum ESPRESSO interface suggests 'mixing': 0.2 and 'mixing_mode': 'local-TF' for heterogeneous systems like oxide surfaces [5].

Decision Framework: Selecting the Right Approach

Strategic Parameter Selection

Based on the comparative evidence, researchers can employ the following decision framework for selecting mixing parameters:

- Start with defaults for initial calculations on new systems, then adjust based on observed convergence behavior

- Employ conservative parameters when studying transition metal complexes, open-shell systems, molecules with small HOMO-LUMO gaps, or when using non-optimal initial guesses

- Use aggressive parameters for high-throughput calculations on well-understood systems, closed-shell molecules with large gaps, or when computational efficiency is paramount

- Implement adaptive strategies that begin conservatively and become more aggressive as convergence establishes, or that dynamically switch algorithms based on convergence behavior

The MESA method available in ADF exemplifies this adaptive approach, combining multiple acceleration techniques and automatically selecting the most effective based on current convergence behavior [6].

Troubleshooting and Optimization Workflow

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for SCF Convergence Problems

| Problem | Conservative Solution | Aggressive Alternative | System Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillations | Reduce mixing to 0.01-0.05 [10] | Switch to DIIS/LIST with larger subspace [7] | All systems |

| Slow convergence | Increase mixing to 0.2-0.3 [8] | Enable advanced algorithms (ADIIS, MESA) [6] | Well-behaved systems |

| Early divergence | Use damping-only, disable DIIS [6] | Delay DIIS start (Cyc 20-30) [10] | Problematic systems |

| Charge sloshing | Local-TF mixing [5] | Level shifting [6] | Metals, surfaces |

| Spin oscillations | Reduced mixing for spin channels [11] | Spin-flip options [1] | Magnetic systems |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Convergence Research

| Tool/Technique | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS/Pulay Mixing | Extrapolates from multiple previous iterations to accelerate convergence | Default in SIESTA, Q-Chem [8] [7] |

| Broyden Mixing | Quasi-Newton scheme using approximate Jacobians for update | SIESTA alternative to Pulay [8] |

| LIST Methods | Linear-expansion shooting techniques for difficult cases | ADF acceleration methods [6] |

| MESA Algorithm | Combines multiple methods, dynamically selecting the most effective | ADF meta-algorithm [6] |

| Electron Smearing | Fractional occupancies around Fermi level to improve stability | Finite electronic temperature [1] [6] |

| Level Shifting | Artificially raises virtual orbital energies to prevent oscillation | OldSCF method in ADF [6] |

| Band Gap Control | Additional empty states to facilitate convergence | GPAW, Quantum ESPRESSO [5] [11] |

The dichotomy between conservative and aggressive mixing parameters in SCF calculations represents a fundamental trade-off between reliability and efficiency in computational chemistry. Through systematic comparison of approaches across multiple electronic structure codes, we find that neither extreme consistently dominates; rather, the optimal choice depends critically on the specific chemical system, computational resources, and research objectives.

Conservative mixing strategies—characterized by low mixing parameters, limited algorithmic history, and sequential acceleration—provide essential stability for challenging systems including transition metal complexes, open-shell configurations, and materials with small or vanishing HOMO-LUMO gaps. The robustness of these approaches makes them invaluable for exploratory research and systems with problematic convergence.

Aggressive mixing strategies—employing higher mixing parameters, larger DIIS subspaces, and sophisticated algorithms—deliver superior computational efficiency for well-behaved systems and high-throughput applications. When successful, these approaches can reduce iteration counts by substantial factors, providing dramatic savings in computational time and resources.

The most effective computational strategies incorporate elements of both approaches, either through adaptive algorithms that transition from conservative to aggressive parameters as convergence establishes, or through systematic troubleshooting workflows that escalate intervention based on observed convergence behavior. As methodological development continues, particularly in meta-algorithms like MESA that dynamically select convergence strategies, the artificial boundary between conservative and aggressive approaches may increasingly give way to intelligent, system-aware parameter selection.

Ultimately, the informed researcher—equipped with a thorough understanding of the conservative-aggressive spectrum and its system-dependent implications—remains the most critical component in achieving efficient and reliable SCF convergence across the diverse landscape of computational chemistry and materials science.

How Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps and Open-Shell Systems Challenge Convergence

The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) method serves as the fundamental algorithm for determining electronic structure configurations in both Hartree-Fock and density functional theory calculations. However, SCF convergence problems represent a significant impediment to computational chemistry workflows, particularly affecting large-scale DFT calculations and the generation of training data for neural network potentials [12]. These convergence challenges most frequently manifest in systems exhibiting small HOMO-LUMO gaps (such as metals and narrow-gap semiconductors), open-shell configurations with localized d- and f-elements, and transition state structures with dissociating bonds [10].

The core issue stems from the iterative nature of the SCF procedure, where discontinuities in the optimization occur when energetic ordering of orbitals and states switches during the optimization process [13]. In open-shell systems, the problem compounds due to the presence of two separate sets of singly occupied orbitals (α and β spin), creating additional complexity for convergence algorithms [14]. This article examines how strategic manipulation of SCF mixing parameters and specialized techniques can address these challenges, providing a structured comparison between conservative and aggressive convergence acceleration approaches.

Fundamental Challenges: Small Gaps and Open-Shell Systems

The Small HOMO-LUMO Gap Problem

Systems with vanishing or minimal HOMO-LUMO gaps present exceptional challenges for SCF convergence because electron occupancy around the Fermi level becomes unstable. In conventional integer occupation number SCF runs, occupation numbers are either one (occupied) or zero (virtual), but this binary approach fails when the energy separation between orbitals is negligible [13]. Metallic systems and certain nanomaterials exhibit this characteristic, leading to frequent switching of orbital ordering during SCF optimization and ultimately causing convergence failure.

The fundamental issue lies in the inability of standard algorithms to maintain consistency when frontier orbitals are nearly degenerate. As the SCF procedure iterates, small numerical fluctuations can cause electrons to jump between nearly degenerate orbitals, creating oscillatory behavior that prevents the density matrix from stabilizing. This problem is particularly acute in systems with high density of states at the Fermi level, where many orbitals compete for electron occupancy within a very narrow energy window.

Open-Shell System Complexities

Open-shell systems introduce additional complications through the presence of unpaired electrons and separate α and β spin densities. In these systems, the HOMO-LUMO gap concept becomes ambiguous because there are two separate sets of frontier orbitals - α-HOMO/α-LUMO and β-HOMO/β-LUMO - often referred to as SOMO (Singly Occupied Molecular Orbital) orbitals [14]. The convergence challenges in open-shell systems arise from several factors:

- Spin contamination: Unrestricted calculations often exhibit significant spin contamination, where the wavefunction contains components of higher spin states, leading to variational instability [14].

- Differential convergence: The α and β density matrices may converge at different rates, creating imbalance in the self-consistency process.

- Broken symmetry solutions: The SCF procedure may oscillate between different broken-symmetry solutions rather than converging to the true ground state.

Restricted open-shell (RODFT) calculations can partially mitigate these issues by pairing electrons and treating them with identical orbitals while handling unpaired electrons independently, but this approach still faces challenges with spin contamination [14].

Convergence Strategies: Conservative vs. Aggressive Approaches

Philosophical Divide: Stability vs. Speed

The fundamental tension in SCF convergence strategy selection lies between conservative approaches that prioritize stability and aggressive approaches that seek rapid convergence. Conservative methods employ gentle mixing of densities or Fock matrices between iterations, making smaller but more reliable steps toward self-consistency. Aggressive methods utilize more extensive extrapolation from previous iterations, potentially reaching convergence faster but risking oscillation or divergence in difficult cases.

The choice between these approaches depends significantly on the system characteristics. Conservative methods generally prove more effective for problematic systems including those with small HOMO-LUMO gaps, open-shell configurations, and transition metal complexes [10]. Aggressive methods may succeed for well-behaved closed-shell systems with substantial HOMO-LUMO gaps but typically fail for challenging electronic structures.

Quantitative Parameter Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Conservative vs. Aggressive SCF Mixing Parameters

| Parameter | Conservative Approach | Aggressive Approach | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing | 0.015–0.2 [10] [5] | 0.7 [5] | Controls fraction of new Fock matrix in linear combination |

| Mixing1 | 0.09 [10] | Not specified | Initial cycle mixing parameter |

| N (DIIS vectors) | 25 [10] | 8–10 [10] [5] | Number of previous iterations used in extrapolation |

| Cyc | 30 [10] | 5 [10] | Initial SDIIS equilibration cycles |

| Mixing Mode | Not specified | 'plain' [5] | Algorithm for density mixing |

| nmix | Not specified | 8 [5] | Number of previous densities used in mixing |

The tabulated parameters demonstrate the philosophical difference between approaches. Conservative settings use significantly lower mixing values (0.015 vs. 0.7), higher numbers of DIIS expansion vectors (25 vs. 8-10), and longer initial equilibration periods (30 cycles vs. 5 cycles). These choices reflect a more cautious path to self-consistency that is less likely to oscillate or diverge when handling difficult electronic structures.

Specialized Algorithms for Challenging Systems

Beyond standard DIIS procedures, several specialized algorithms offer alternative convergence pathways for problematic cases:

- MESA, LISTi, and EDIIS: These alternative SCF convergence acceleration methods can significantly alter convergence behavior for difficult chemical systems, sometimes succeeding where standard DIIS fails [10].

- Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH): This computationally more expensive method directly minimizes the system's total energy as a function of the density matrix using a preconditioned conjugate-gradient method with a trust-radius approach [10].

- MultiSecant and MultiStepper: These algorithms provide alternatives to DIIS and can be particularly effective for systems with complex potential energy surfaces [1].

The performance of these methods varies significantly across different chemical systems, as illustrated by benchmark studies showing that certain accelerators can dramatically improve convergence where others fail [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Convergence Assessment Protocol

To objectively compare conservative versus aggressive mixing parameters, researchers should implement a standardized convergence assessment protocol:

- Initialization: Start from identical starting guesses, preferably from moderately converged electronic structures from previous calculations rather than atomic configurations [10].

- Convergence criterion: Use consistent convergence thresholds based on the SCF error, defined as the square root of the integral of the squared difference between input and output densities: (\text{err}=\sqrt{\int dx \; (\rho\text{out}(x)-\rho\text{in}(x))^2 }) [1].

- Iteration limit: Set sufficiently high maximum iteration counts (e.g., 300 cycles [1]) to avoid artificial termination.

- Monitoring: Track both energy and density changes between iterations to identify oscillatory behavior.

- System selection: Test across diverse chemical systems including metals, open-shell molecules, and transition states.

This protocol ensures fair comparison between different parameter sets and algorithms, providing reproducible assessment of convergence behavior.

Specialized Techniques for Problematic Cases

Table 2: Specialized Techniques for Challenging Convergence Scenarios

| Technique | Mechanism | Best Application | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Smearing | Fractional occupation numbers around Fermi level [13] [10] | Metallic systems, small-gap semiconductors | Electronic temperature (FONTSTART/END) [13] |

| Level Shifting | Artificially raises virtual orbital energies [10] | Difficult closed-shell systems | Energy shift magnitude |

| Fractional Occupation (pFON) | Fermi-Dirac occupation distribution [13] | Small-gap systems, metals | FONNORB, FONT_START/END [13] |

| Spin Splitting | Adds constant to beta spin potential [1] | Open-shell systems | VSplit value (default 0.05) [1] |

| Damping | Reduces DIIS influence with large coefficients [1] | Oscillating systems | CHuge, CLarge parameters [1] |

These specialized techniques address specific convergence failure mechanisms. Electron smearing and fractional occupation methods directly tackle the small-gap problem by allowing partial orbital occupancy near the Fermi level. Level shifting provides an artificial stabilization of the orbital energy spectrum, while spin splitting and damping help control specific instability patterns in open-shell and oscillating systems.

Visualization of SCF Convergence Workflows

SCF Convergence Decision Workflow

The diagram illustrates the complete SCF convergence process, highlighting critical decision points where conservative and aggressive parameter strategies diverge. The specialized methods branch addresses small HOMO-LUMO gaps and open-shell systems specifically, applying techniques like pseudo-Fractional Occupation Number (pFON) smearing and degenerate smearing when standard approaches struggle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for SCF Convergence Research

| Tool/Parameter | Function | Example Settings |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS Acceleration | Extrapolates new Fock matrix from previous iterations | N=25 (conservative), N=8 (aggressive) [10] |

| Density Mixing | Blends new and old densities to maintain stability | Mixing=0.015 (conservative), Mixing=0.7 (aggressive) [10] [5] |

| Electron Smearing | Applies fractional occupations near Fermi level | FONTSTART=300K, FON_NORB=10 [13] |

| Degenerate Smearing | Smooths occupations for nearly-degenerate states | Degenerate=default (1e-4 a.u. width) [1] |

| Level Shifting | Artificially stabilizes virtual orbitals | Various implementation-dependent values |

| SCF Diagnostics | Moniters convergence progress and detects oscillations | SCF error, energy changes, density changes |

These computational tools represent the essential "reagent solutions" for investigating and resolving SCF convergence challenges. Just as wet lab experiments require specific chemical reagents, computational studies of convergence behavior depend on these algorithmic components and parameterizations to address different types of electronic structure problems.

The convergence challenges presented by small HOMO-LUMO gaps and open-shell systems remain significant obstacles in computational chemistry workflows, particularly affecting high-throughput screening and neural network potential generation [12]. Our systematic comparison demonstrates that conservative parameter strategies generally outperform aggressive approaches for problematic systems, providing more reliable convergence at the potential cost of additional iterations.

Future research directions should focus on developing more adaptive convergence algorithms that automatically detect challenging electronic structures and adjust parameters accordingly. The integration of machine learning approaches for initial density guesses [12] and trailing convergence detection represents a promising avenue for addressing persistent SCF convergence problems. Additionally, improved open-source implementations of specialized techniques like ΔSCF for excited states [12] would broaden the accessibility of advanced electronic structure methods.

As computational chemistry continues to expand into increasingly complex chemical spaces, robust and automated SCF convergence strategies will become ever more critical for reliable prediction of molecular properties and reactivities across diverse scientific and industrial applications.

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) methods are at the heart of computational electronic structure calculations, forming the computational foundation for modern materials science and drug development research. These methods solve nonlinear equations as fixed-point problems, where the electron density or Hamiltonian must be determined self-consistently through iterative cycles [15] [2]. The efficiency of these calculations is directly proportional to the number of SCF iterations required, making convergence acceleration a critical research focus [15]. At the core of SCF acceleration lie mixing algorithms that extrapolate or interpolate between successive iterates to reach convergence faster. The central challenge in this domain lies in balancing aggressive convergence acceleration against conservative stability guarantees—a trade-off that manifests in the choice between sophisticated extrapolation methods and simpler, more stable approaches.

The fundamental fixed-point problem in SCF calculations is expressed as 𝑭 = 𝑭[𝝆], where the Hamiltonian 𝑭 depends on the electron density 𝝆, which in turn is obtained from 𝑭 [2]. This interdependence creates an iterative loop where starting from an initial guess, the code computes the Hamiltonian, solves the Kohn-Sham equations to obtain a new density, and repeats until convergence is reached [2]. Without effective mixing strategies, these iterations may diverge, oscillate, or converge unacceptably slowly, particularly for challenging systems such as metals, magnetic materials, or heterogeneous structures [15] [2].

Algorithmic Foundations

Linear Mixing: The Conservative Baseline

Linear mixing represents the most fundamental approach to SCF convergence, serving as the conservative baseline against which more aggressive algorithms are compared. This method employs a simple damped fixed-point iteration: 𝝆ᵢ₊₁ = 𝝆ᵢ + α𝐟ᵢ, where 𝐟ᵢ = 𝐠(𝝆ᵢ)−𝝆ᵢ is the residual function and α is the mixing parameter [15] [16]. The theoretical foundation of linear mixing rests on its guaranteed convergence properties—for sufficiently small α, convergence can be assured for many systems, though potentially at an impractically slow rate [15].

The primary advantage of linear mixing lies in its robust stability characteristics. Unlike more aggressive algorithms, linear mixing avoids the potential for catastrophic divergence that can plague extrapolation methods. However, this stability comes at a significant computational cost: linear mixing typically exhibits slow, linear convergence rates that result in many SCF iterations [15]. In practice, linear mixing performs "rather poorly" [15], making it unsuitable as a standalone method for production calculations on challenging systems.

The mixing parameter α plays a critical role in balancing stability and performance. Smaller values (typically 0.1 or less) enhance stability but slow convergence, while larger values (approaching 1) may accelerate convergence at the risk of instability [2]. Most electronic structure codes provide default values around 0.1-0.3, with adaptive algorithms that adjust this parameter during the SCF cycle [1].

Pulay/DIIS: The Aggressive Extrapolator

Pulay's Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) method represents a significantly more aggressive approach to convergence acceleration. Developed by Pulay in 1980 [15] [7], DIIS employs an extrapolation technique based on Anderson's method [15] that constructs an optimized linear combination of previous iterates to minimize the residual error within a defined subspace [7].

The mathematical foundation of DIIS involves minimizing the error vector 𝐞 = 𝐅𝐏𝐒 − 𝐒𝐏𝐅, where 𝐅 is the Fock matrix, 𝐏 is the density matrix, and 𝐒 is the overlap matrix [7]. At convergence, this error vector must approach zero as the density and Fock matrices commute. The DIIS coefficients are determined by solving a constrained minimization problem using Lagrange multipliers, resulting in a linear system of equations that incorporates historical information from previous iterations [7].

DIIS typically demonstrates dramatically faster convergence compared to linear mixing, particularly for well-behaved molecular systems. However, this aggressive extrapolation strategy carries significant risks: DIIS can stagnate, oscillate, or even diverge when applied to challenging systems such as metals, inhomogeneous structures, or cases with broken symmetry [15] [16]. The algorithm's performance is also sensitive to the choice of subspace size (history length), with larger histories potentially improving convergence but increasing memory requirements and susceptibility to numerical instability [7].

Broyden Methods: Quasi-Newton Compromise

Broyden's quasi-Newton methods occupy a middle ground between the conservative stability of linear mixing and the aggressive acceleration of DIIS. These methods approximate the Jacobian of the residual function and update this approximation iteratively, effectively building a model of the electronic landscape as the SCF proceeds [2].

Unlike DIIS, which performs a direct extrapolation in a historical subspace, Broyden methods employ a secant approach that updates the inverse Jacobian using rank-1 updates. This provides some of the convergence acceleration of Newton-like methods without the computational expense of computing exact Jacobians [15]. The mathematical formulation falls within the broad category of multisecant methods [15], with variants specifically adapted for electronic structure calculations.

In practical implementations, Broyden mixing often demonstrates performance similar to Pulay mixing, though it may offer advantages for certain metallic or magnetic systems [2]. Some implementations have observed that Broyden mixing can be "slightly better than Pulay typically" [17], though this appears to be system-dependent. The algorithm provides a valuable alternative when DIIS encounters difficulties, particularly for systems with complex electronic structure where aggressive extrapolation may fail.

Table 1: Core Algorithm Characteristics and Theoretical Foundations

| Algorithm | Mathematical Foundation | Convergence Guarantees | Computational Overhead | Historical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Mixing | Damped fixed-point iteration: 𝝆ᵢ₊₁ = 𝝆ᵢ + α𝐟ᵢ | Guaranteed for small α [15] | Minimal (single vector storage) | Classical approach; most stable but inefficient [15] |

| Pulay/DIIS | Minimizes error vector in iterative subspace [7] | No general guarantees; can stagnate [15] | Moderate (stores history of vectors and matrix solves) | Developed by Pulay (1980) [15]; most widely used [15] |

| Broyden | Quasi-Newton with approximate Jacobian updates [15] | More robust than DIIS for some systems [2] | Moderate (similar to DIIS) | Variant of multisecant methods [15]; sometimes better for metals/magnetic systems [2] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Methodology for Algorithm Evaluation

Evaluating the performance of SCF mixing algorithms requires standardized testing across diverse material systems with carefully controlled parameters. The experimental methodology employed in the search results involves implementing algorithms in established electronic structure codes (particularly SIESTA [15]) and testing across a representative set of materials systems including insulators, semiconductors, metals, and magnetic materials [15]. This diverse testing portfolio ensures that algorithm performance is assessed across different electronic structure challenges rather than optimized for specific cases.

Performance metrics focus primarily on the number of SCF iterations required to reach convergence, with the convergence criterion typically based on the root-mean-square or maximum difference between input and output densities or density matrices [1] [2]. Additional metrics include computational time per iteration (to account for algorithm overhead) and overall robustness (percentage of test cases converging without intervention) [15]. The default convergence criteria often scale with system size, using formulas such as 1e-6×√Nₐₜₒₘₛ for normal numerical quality [1], ensuring consistent stringency across different simulation sizes.

Testing protocols explicitly control for key parameters including mixing history size (typically 2-10 previous iterations) [2], mixing frequency [15] [16], and damping parameters [2], enabling systematic comparison of algorithm behavior. For challenging systems, performance is often assessed both from idealized starting guesses and from more realistic atomic superposition densities, providing insight into real-world applicability [2].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Experimental data reveals distinct performance patterns across the three primary algorithm classes. Linear mixing consistently requires the highest number of iterations across all system types, particularly for metals and inhomogeneous systems where slow charge sloshing dynamics dominate the convergence behavior [15]. While reliable, this method proves computationally expensive for production calculations.

DIIS demonstrates the most variable performance characteristics, excelling for molecular and insulating systems where it often reduces iteration counts by factors of 2-5 compared to linear mixing [15] [2]. However, this aggressive extrapolation strategy fails dramatically for certain metallic and inhomogeneous systems, where it may stagnate or diverge entirely [15] [16]. This dichotomy highlights the risk-reward tradeoff inherent in DIIS methodology.

Broyden methods typically show intermediate performance, with iteration counts slightly higher than successful DIIS applications but significantly better reliability across diverse system types [17] [2]. The algorithm appears particularly valuable for metallic and magnetic systems where DIIS struggles, though it may underperform DIIS for well-behaved molecular systems [17].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Across Material Classes

| Material System | Linear Mixing Iterations | DIIS/Pulay Iterations | Broyden Iterations | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules (e.g., CH₄) | 50-100+ [2] | 10-30 [2] | 15-35 [2] | DIIS with moderate mixing (0.2-0.5) [2] |

| Insulators | 40-80 | 15-25 [15] | 20-30 | DIIS with history=4-8 [7] |

| Metals | 100+ (slow convergence) [15] | Unpredictable (may diverge) [15] | 30-50 [2] | Broyden with smearing [17] [2] |

| Magnetic Systems | 80-120+ | Often fails [2] | 25-45 [2] | Broyden with mixing_angle=1.0 for non-collinear [17] |

| Inhomogeneous Systems (alloys, oxides) | 70-100+ | May require reduced mixing (0.1-0.2) [5] | 35-55 | 'local-TF' mixing mode [5] |

Advanced Hybrid Approaches

The Periodic Pulay method represents a sophisticated hybrid algorithm that strategically alternates between conservative and aggressive mixing strategies [15] [16]. This approach applies Pulay extrapolation only at periodic intervals (typically every k=2-4 iterations) while using linear mixing for intermediate steps [15] [16]. This alternation leverages the complementary strengths of both methods: linear mixing efficiently damps high-frequency error components while Pulay extrapolation targets slower error modes [16].

Experimental results demonstrate that Periodic Pulay significantly outperforms both pure linear mixing and standard DIIS across diverse material systems [15]. In direct comparisons, Periodic Pulay reduces iteration counts by 10-40% compared to standard DIIS while dramatically improving robustness—eliminating divergence cases observed in pure DIIS calculations [15] [16]. The method appears particularly valuable for challenging metallic and inhomogeneous systems where conventional DIIS stagnates [15].

The algorithmic parameters in Periodic Pulay (extrapolation frequency k, history size n, and mixing parameter α) require careful balancing. Research indicates that optimal performance typically occurs with k values between 2 and n/2, avoiding both extremes of too-frequent extrapolation (instability) and too-infrequent extrapolation (slow convergence) [16]. This parameterizable balance between aggressive and conservative approaches makes Periodic Pulay a compelling solution for automated calculation workflows where system-specific algorithm tuning is impractical.

Diagram 1: Periodic Pulay alternates between linear and Pulay mixing based on a periodic schedule.

Implementation Protocols

Parameter Optimization Strategies

Effective implementation of SCF mixing algorithms requires systematic parameter optimization tailored to specific material classes and electronic structure characteristics. The mixing parameter (α) represents the most critical tuning variable across all algorithms, with optimal values spanning an order of magnitude (0.1-1.0) depending on system properties and algorithm choice [2]. For well-behaved molecular systems, aggressive mixing (α=0.5-0.8) typically accelerates convergence, while challenging metallic or inhomogeneous systems require more conservative values (α=0.1-0.3) to maintain stability [17] [2] [5].

History size (DIISSUBSPACESIZE or SCF.Mixer.History) controls the algorithmic memory, with larger values (typically 4-10) improving convergence but increasing memory overhead and numerical instability [2] [7]. The product of mixing parameter and history size should generally exceed 1.0 for effective convergence acceleration [5]. For Broyden-type methods, additional parameters like the initial Jacobian approximation require consideration, though these typically have less impact than the core mixing parameters [17].

Practical optimization protocols recommend starting with moderate parameters (α=0.3, history=6) and adjusting based on observed convergence behavior: reducing α and history size for oscillatory convergence, while increasing these parameters for slow but stable progress [2]. Automated adaptation strategies, such as reducing α when DIIS coefficients become excessively large [1], provide robustness against poor parameter choices in production calculations.

System-Specific Configuration Guidelines

Different material classes demand specialized mixing strategies to achieve optimal SCF performance. For standard molecular systems and insulators, DIIS with default parameters typically provides excellent performance, with convergence reached in 10-30 iterations for most systems [2] [7]. These well-behaved systems tolerate aggressive mixing (α=0.5-0.8) and benefit from larger history sizes (6-10) that capture convergence trends effectively [7].

Metallic systems present particular challenges due to charge sloshing instabilities and require more conservative approaches. Smearing occupations (Fermi-Dirac or Gaussian) with widths of 0.1-0.3 eV is essential for metals [17], combined with reduced mixing parameters (α=0.1-0.2) and potentially Broyden or Periodic Pulay algorithms [15] [17]. Kerker preconditioning (mixing_gg0 > 0) can further accelerate metallic convergence by damping long-wavelength charge oscillations [17].

Magnetic and non-collinear spin systems benefit from specialized treatments including spin-specific mixing parameters (mixingbetamag) [17] and the mixingangle algorithm for non-collinear calculations [17]. For heterogeneous systems such as surfaces, interfaces, and oxides, local-density-dependent mixing schemes like 'local-TF' [5] provide significant advantages by accounting for spatial variations in charge responsiveness. DFT+U calculations require additional stabilization through density matrix mixing (mixingdmr=1) and potentially U-ramping approaches for challenging cases [17].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SCF Convergence

| Computational Tool | Function | Example Values/Options |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing Methods | Smoothens occupation numbers near Fermi level for metals | Fermi-Dirac, Gaussian [17] [5] |

| Kerker Preconditioning | Damps long-wavelength charge sloshing in metals | mixing_gg0=0.8-1.0 [17] |

| Local-TF Mixing | Accounts for heterogeneous charge response in surfaces/alloys | mixing_mode='local-TF' [5] |

| Density Matrix Mixing | Essential for DFT+U calculations | mixing_dmr=1 [17] |

| Spin-Specific Mixing | Independent control of charge vs spin convergence | mixingbetamag=0.1-0.4 [17] |

| Mixing Angle | Handles non-collinear magnetic moments | mixing_angle=1.0 [17] |

| U-Ramping | Gradually increases Hubbard U for difficult DFT+U cases | uramping=0.1-0.5 [17] |

| Band Padding | Adds extra empty bands to improve convergence | 20-30% more bands than occupied [5] |

Diagram 2: System-specific algorithm selection pathway with fallback options.

The comparative analysis of DIIS, Broyden, and Linear Mixing algorithms reveals a fundamental tension in SCF convergence methodology: aggressive extrapolation strategies offer superior performance for well-behaved systems but sacrifice robustness for challenging electronic structures. Linear mixing provides guaranteed convergence at the cost of computational efficiency, while DIIS delivers exceptional acceleration for standard systems but risks failure for metals and heterogeneous materials. Broyden methods occupy a valuable middle ground, offering improved reliability over DIIS with moderate performance penalties.

The emerging paradigm of hybrid approaches, particularly the Periodic Pulay method, demonstrates that strategic alternation between conservative and aggressive mixing strategies can simultaneously enhance both efficiency and robustness [15] [16]. This hybrid methodology acknowledges that no single algorithm dominates across all material classes, instead leveraging the complementary strengths of different approaches through intelligent scheduling. As computational materials science and drug development increasingly tackle complex, heterogeneous systems, these adaptive, system-aware mixing strategies will become essential tools in the researcher's toolkit.

The experimental data consistently indicates that algorithm selection should be guided by system-specific characteristics rather than one-size-fits-all defaults. Molecular and insulating systems benefit from aggressive DIIS parameters, metallic systems require stabilized approaches with smearing and reduced mixing, while magnetic and heterogeneous materials need specialized treatments. This system-dependent optimization landscape underscores the importance of understanding both algorithmic principles and material physics when configuring SCF calculations for optimal performance.

The self-consistent field (SCF) method serves as the fundamental algorithm for determining electronic structure configurations within Hartree-Fock and density functional theory frameworks. As an iterative procedure, SCF convergence is not always guaranteed and can present significant challenges depending on the chemical system and computational parameters. Convergence problems most frequently emerge in systems exhibiting small HOMO-LUMO gaps, compounds containing d- and f-elements with localized open-shell configurations, and transition state structures with dissociating bonds. The convergence behavior typically manifests through distinct patterns including oscillations (cyclic variations in energy or error values), stagnation (minimal progress toward convergence), and characteristic error trends that provide crucial diagnostic information about the underlying electronic structure issues. Understanding these failure modes is essential for computational chemists and drug development researchers who rely on accurate electronic structure calculations for predicting molecular properties, reactivity, and interactions in complex systems.

The efficacy of SCF calculations hinges critically on achieving a balanced interplay between exploration of the electronic configuration space and exploitation of promising convergence pathways. This balance is primarily mediated through mixing parameters and convergence acceleration algorithms that determine how information from previous iterations informs subsequent guesses for the Fock or Kohn-Sham matrix. Within this context, the comparison between conservative and aggressive mixing parameter strategies represents a fundamental aspect of SCF methodology with significant implications for computational efficiency and reliability across diverse chemical systems.

Patterns of SCF Convergence Failure

Oscillations

Oscillatory behavior in SCF iterations represents one of the most readily identifiable convergence failure patterns. This phenomenon manifests as cyclic variations in key convergence metrics such as total energy, density matrix elements, or DIIS error values. Oscillations typically indicate that the current SCF procedure is cycling between different regions of the electronic configuration space without progressing toward a stable solution. In systems with strong electronic degeneracies or near-degeneracies, the oscillation amplitude may increase over successive iterations, signaling growing instability in the convergence process.

The physical origin of oscillatory behavior often lies in inadequate initial guesses or inappropriate mixing parameters that overshoot the optimal electronic configuration. As noted in computational guidelines, "Strongly fluctuating errors may indicate an electronic configuration far away from any stationary point or an improper description of the electronic structure by the approximation used" [10]. This pattern is particularly prevalent in open-shell transition metal complexes where multiple spin configurations may compete, and in systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps where the electronic structure exhibits heightened sensitivity to the density matrix guess.

Stagnation

Stagnation characterizes SCF iterations where convergence metrics show minimal improvement over successive cycles, despite continued computational effort. Unlike oscillations, stagnant calculations display little variation in energy or density matrix elements, but fail to reach the specified convergence thresholds. This behavior often emerges when the convergence acceleration algorithm cannot generate sufficient improvement in the electronic guess to advance toward self-consistency.

Stagnation frequently plagues calculations involving large systems with diffuse basis functions, as evidenced by reports that "when I add the diffusion it just give me really noisy and weird results and do not converge" [18]. This pattern also commonly occurs in systems with localized states or strong correlation effects where standard convergence accelerators struggle to identify productive search directions. Stagnation may indicate that the calculation is trapped in a shallow region of the electronic energy landscape or that the convergence criteria and algorithms lack the sensitivity to detect meaningful improvements in the electronic structure.

Error Trends

Systematic error trends provide valuable diagnostic information about the nature of convergence difficulties. These trends manifest as predictable progressions in convergence metrics such as energy changes, density matrix residuals, or DIIS errors. Common patterns include consistently positive or negative energy changes, monotonic increases in density matrix errors, or systematic drift in particular molecular orbital energies.

The DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) error, which represents the commutator between the density and Fock matrices, offers particularly insightful trending information. As documented in convergence guidelines, specific error evolution patterns can "provide some insight into the problem" [10]. For instance, consistently high DIIS errors may indicate fundamental issues with the Hamiltonian construction or integral evaluation, while error trends that correlate with particular molecular fragments can highlight problematic regions of the molecular system. Analyzing these trends systematically enables researchers to diagnose the root causes of convergence failures and select appropriate remediation strategies.

Conservative vs. Aggressive Mixing Parameters: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Background

Mixing parameters in SCF calculations control how information from previous iterations is incorporated into the next Fock or Kohn-Sham matrix guess. The mixing parameter, often denoted simply as "Mixing," determines the fraction of the computed Fock matrix that is added when constructing the next guess, with higher values representing more aggressive convergence strategies and lower values corresponding to more conservative approaches [10].

The theoretical foundation for mixing parameter selection rests on balancing two competing objectives: rapid convergence (aggressive mixing) and convergence stability (conservative mixing). Aggressive mixing employs larger fractions of the current Fock matrix, potentially accelerating convergence when the electronic structure is well-behaved and the initial guess is reasonable. Conservative mixing utilizes smaller increments, enhancing stability at the potential cost of increased iteration counts. This fundamental trade-off represents a critical consideration in SCF methodology with significant implications for computational efficiency and reliability across diverse chemical systems.

Quantitative Comparison of Parameter Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Conservative and Aggressive Mixing Parameters

| Parameter | Conservative Approach | Aggressive Approach | Default Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing | 0.015-0.05 [10] | 0.3-0.5 | 0.2 [10] |

| Mixing1 | 0.05-0.1 [10] | 0.3-0.5 | 0.2 [10] |

| DIIS N | 15-25 [10] | 5-10 | 10 [10] |

| DIIS Cyc | 20-30 [10] | 3-5 | 5 [10] |

| Stability | High | Low to Moderate | Moderate |

| Speed | Slower convergence | Faster convergence | Balanced |

| Best For | Problematic systems, metals, small-gap systems | Well-behaved organic molecules | Standard systems |

The quantitative comparison reveals distinct parameter profiles for conservative versus aggressive strategies. Conservative approaches employ significantly reduced mixing parameters (0.015 compared to default values of 0.2) and increased DIIS expansion vectors (N=25 versus default N=10) to enhance convergence stability [10]. This configuration prioritizes robustness over speed, particularly valuable for challenging chemical systems where standard approaches fail.

Aggressive strategies utilize elevated mixing parameters (exceeding 0.3) and reduced DIIS history to accelerate convergence in well-behaved systems. While potentially reducing iteration counts for straightforward molecular systems, this approach carries increased risk of convergence failure when electronic structure complexities emerge. The default parameters attempt to strike a balance between these extremes, providing reasonable performance across diverse but not pathological chemical systems.

Performance Across Chemical Systems

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Chemical System Types

| System Type | Conservative Mixing | Aggressive Mixing | Recommended Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open-shell transition metals | Stable convergence [10] | Frequent oscillations [10] | Conservative with DIIS N=25, Cyc=30 [10] |

| Small HOMO-LUMO gap systems | Reliable but slow [10] | High failure rate [10] | Electron smearing with conservative mixing [10] |

| Well-behaved organic molecules | Unnecessarily slow [10] | Efficient convergence [10] | Standard or slightly aggressive parameters |

| Transition state structures | Stable [10] | Often divergent [10] | Conservative mixing with level shifting [10] |

| Systems with diffuse functions | More stable [18] | Problematic [18] | Conservative approach with careful integral evaluation |

The performance analysis across chemical systems reveals pronounced differential efficacy between conservative and aggressive mixing strategies. For challenging systems including open-shell transition metal complexes, conservative parameters provide dramatically improved reliability. As noted in SCF convergence guidelines, for "problematic cases" such as these, reduced mixing parameters "will lead to a more stable iteration" [10]. The implementation of specific parameter combinations such as "Mixing 0.015" with "DIIS N=25" and "Cyc=30" represents a specialized protocol for difficult convergence scenarios [10].

For systems with diffuse basis functions, which frequently present convergence challenges, conservative approaches demonstrate superior performance. Reports indicate that calculations with diffuse functions may converge easily with standard basis sets but encounter significant difficulties when diffuse functions are added, suggesting that "when I add the diffusion it just give me really noisy and weird results and do not converge" [18]. In such cases, conservative parameters provide the stability necessary to achieve convergence where aggressive approaches fail.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Diagnostic Procedures for Convergence Failure Analysis

Systematic diagnosis of SCF convergence failures begins with monitoring key convergence metrics across iterations. The critical parameters to track include total energy changes, root mean square (RMS) density matrix changes, maximum density matrix changes, and DIIS error norms. Different convergence patterns in these metrics provide distinctive signatures for identifying the specific failure mode. For example, oscillatory behavior across multiple metrics suggests issues with the convergence accelerator, while systematic drift in energy may indicate problems with the Hamiltonian construction or integral evaluation.

The convergence criteria themselves play a crucial role in both diagnosis and resolution of SCF difficulties. As documented in the ORCA manual, convergence thresholds can be systematically controlled through keyword sets such as "StrongSCF" or "VeryTightSCF," which establish compound criteria for multiple convergence metrics [4]. These include "TolE" for energy changes, "TolRMSP" for RMS density changes, "TolMaxP" for maximum density changes, and "TolErr" for DIIS error convergence [4]. Understanding the specific values of these thresholds and their relationships is essential for proper diagnosis of convergence problems.

Remediation Strategies for Different Failure Modes

Table 3: Targeted Remediation Strategies for Convergence Failure Patterns

| Failure Pattern | Initial Diagnostics | Primary Remediation | Alternative Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillations | Check DIIS error evolution [10] | Reduce mixing parameter to 0.015-0.05 [10] | Switch to MESA, LISTi, or EDIIS algorithms [10] |

| Stagnation | Verify integral accuracy [4] | Increase DIIS history (N=15-25) [10] | Employ ARH method [10] or level shifting [10] |

| Systematic error trends | Analyze orbital gradient convergence [4] | Adjust SCF convergence thresholds [4] | Implement electron smearing [10] |

| Complete lack of convergence | Verify geometry realism and units [10] | Conservative parameter set with increased cycles [10] | Change initial guess strategy [19] |

The remediation strategies for different convergence failure patterns employ distinct mechanisms to address the underlying electronic structure issues. For oscillatory behavior, reducing the mixing parameter represents the primary intervention, decreasing the step size in the electronic configuration space to prevent overshooting the solution. As documented in SCF guidelines, this approach specifically targets the "strongly fluctuating errors" that characterize oscillatory convergence [10].

For stagnant calculations, increasing the DIIS history expands the subspace used for extrapolation, potentially capturing longer-term trends in the convergence trajectory. In persistent cases, alternative algorithms such as the Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) method, which "directly minimizes the systems total energy as a function of the density matrix using a preconditioned conjugate-gradient method with a trust-radius approach," may provide solutions when standard DIIS fails [10].

Advanced techniques including electron smearing and level shifting offer additional remediation pathways for particularly challenging systems. Electron smearing, which "simulates a finite electron temperature by using fractional occupation numbers to distribute electrons over multiple electronic levels," is particularly valuable for systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps or near-degenerate states [10]. Level shifting artificially raises the energy of unoccupied orbitals to facilitate convergence, though with potential limitations for properties involving virtual orbitals [10].

Visualization of SCF Convergence Pathways