Beyond the Spacer: How Surface Ligand Engineering Dictates Charge Transport in Quantum Dot Solids

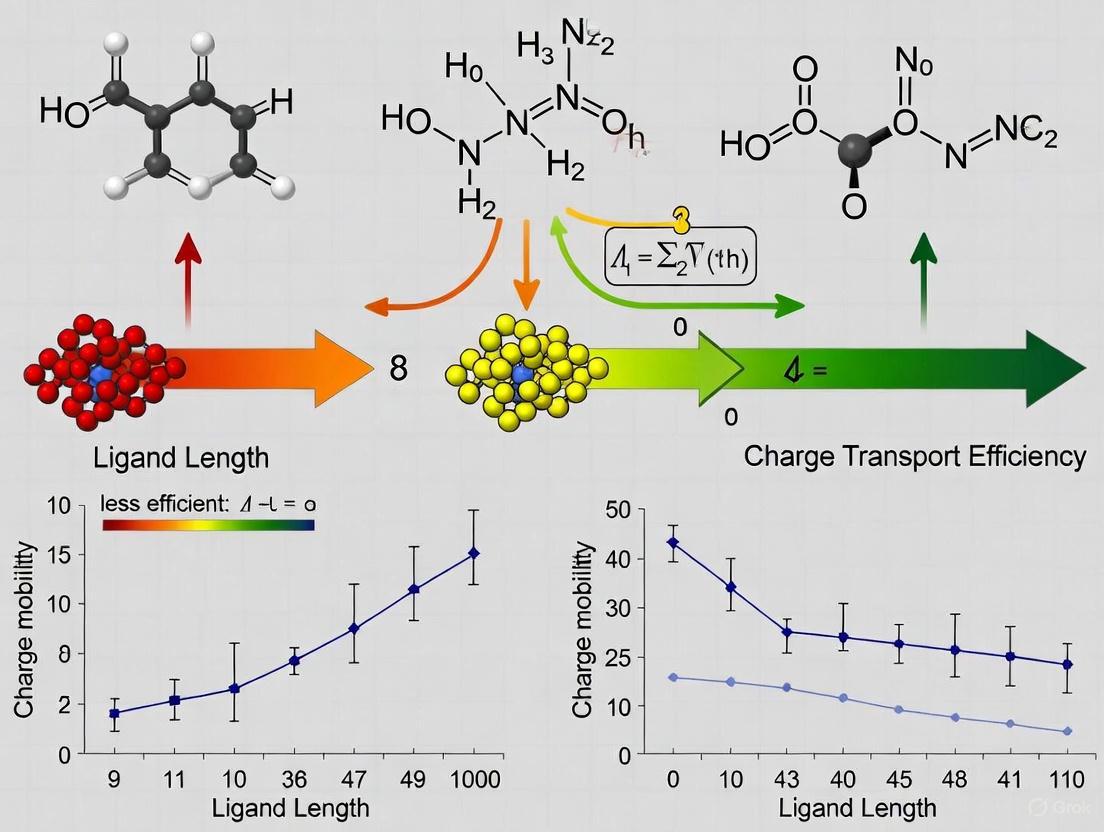

This article comprehensively explores the critical role of surface ligand engineering in controlling charge transport within quantum dot (QD) solids, a key parameter for developing high-performance optoelectronic and biomedical devices.

Beyond the Spacer: How Surface Ligand Engineering Dictates Charge Transport in Quantum Dot Solids

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the critical role of surface ligand engineering in controlling charge transport within quantum dot (QD) solids, a key parameter for developing high-performance optoelectronic and biomedical devices. We first establish the foundational principles, explaining how ligand length influences quantum confinement, inter-dot coupling, and the transition from insulating to conductive behavior. The discussion then progresses to methodological strategies, including ligand exchange processes and the innovative use of redox-active and hybrid ligands to actively participate in charge transport. Furthermore, we address central challenges such as managing energetic disorder, mitigating surface defects, and optimizing solid-state packing. Finally, the article covers advanced validation techniques, from ultrafast spectroscopy to electrochemical and device-level characterization, that correlate ligand structure with device performance. This review serves as a strategic guide for researchers aiming to rationally design QD solids with tailored charge transport properties for advanced applications.

The Fundamental Principles: How Ligand Length Governs Inter-Dot Coupling and Confinement

Quantum dot (QD) solids are materials formed through the assembly of individual nanocrystals into dense, solid films. These materials exhibit unique electronic properties that arise not only from the quantum confinement effect within each dot but also from the interparticle coupling between them [1]. When QD size is reduced to or below the Bohr exciton radius, charge carriers become confined within the structural boundaries, leading to size-tunable optical and electronic properties [2]. This tunability makes QD solids promising building blocks for next-generation technologies including photovoltaics, photodetectors, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and thermoelectrics [2] [1]. The surface chemistry of these quantum dots, governed by their ligand shells, plays a critical role in determining the charge transport properties of the resulting solids. Through careful engineering of surface ligands, researchers can modulate everything from interparticle spacing to electronic structure, enabling precise control over material performance in energy applications [3].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Charge Transport in QD Solids

Electronic Transport Mechanisms

Charge transport in QD solids occurs through several distinct mechanisms, with the dominant pathway heavily influenced by surface ligand chemistry:

- Band-like conduction occurs when strong electronic coupling between neighboring QDs allows carriers to delocalize across multiple dots, resembling transport in bulk semiconductors. This requires very short interparticle distances typically achieved with minimal ligand barriers [1].

- Hopping transport represents the more common mechanism where carriers tunnel between localized states on individual QDs. This process is highly sensitive to interdot distance, following an exponential relationship: shorter ligands reduce tunneling barriers and significantly increase hopping rates [4] [1].

- Tunneling through ligand barriers represents another pathway where carriers penetrate through the energy barrier presented by the organic ligand shell [1].

A groundbreaking shift from traditional thinking has emerged with the concept of "active" versus "passive" ligand roles. Most conventional ligands act as passive spacers whose primary function is to modulate interparticle distance. In contrast, redox-active ligands introduce electronic states that provide an additional pathway for charge transport via self-exchange chain reactions [4]. This represents a paradigm shift in ligand design, where ligands no longer merely get "out of the way" of charge transport but actively participate in the process.

Table 1: Charge Transport Mechanisms in Quantum Dot Solids

| Mechanism | Description | Key Influencing Factors | Role of Ligands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band-like Conduction | Delocalized carriers moving through strongly coupled QDs | Interdot electronic coupling, energetic disorder | Minimize barrier thickness to enable wavefunction overlap |

| Hopping Transport | Thermal-assisted tunneling between localized states | Interparticle distance, temperature, energy level alignment | Determine tunneling distance and barrier height |

| Tunneling | Quantum mechanical penetration through barriers | Barrier height and width | Act as the potential barrier carriers must tunnel through |

| Redox-Mediated Transport | Charge transfer via active ligand states | Ligand redox potential, coverage density, ion transport | Provide active electronic states for charge hopping |

The Critical Role of Surface Ligands

Surface ligands fundamentally determine charge transport efficiency in QD solids through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

- Interparticle Spacing: Ligands form physical barriers between QDs. Longer aliphatic chains (e.g., oleic acid) maintain large separations (>2 nm) that severely limit electronic coupling, while shorter ligands (e.g., halides, pyridine) reduce this distance to <1 nm, dramatically increasing carrier mobility [5] [1].

- Trap State Passivation: Undercoordinated atoms on QD surfaces create electronic trap states that non-radiatively recombine charge carriers. Properly matched ligands (e.g., halides for Pb atoms) coordinate with these sites, reducing trap density and increasing photoluminescence quantum yield [5] [3].

- Electronic Coupling: Certain ligands, particularly conjugated molecules and redox-active species, actively mediate electronic interactions between QDs by providing orbital pathways for charge delocalization [4] [1].

- Doping and Band Alignment: Ligands can introduce doping effects by altering surface stoichiometry or introducing charge impurities. For instance, specific ligands can shift the Fermi level position, enabling n-type or p-type behavior [3] [6].

Diagram 1: Ligand Engineering Workflow for Quantum Dot Solids. This flowchart illustrates the decision process for selecting ligand types based on desired material properties.

Experimental Methods for Probing Charge Transport

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques

Understanding charge dynamics in QD solids requires specialized characterization methods capable of probing ultrafast processes:

Resonant Auger Spectroscopy (RAS) and Core-Hole Clock Spectroscopy (CHCS) employ the core-hole lifetime as an internal clock to measure attosecond-scale electron transfer dynamics [2]. When X-ray excitation creates a transient core-hole state, the resonantly excited electron can either remain localized (Raman decay) or delocalize (Auger decay) within the core-hole lifetime (0.26 fs for Pb 3d). The intensity ratio between these decay channels provides quantitative charge transfer times, revealing that larger PbS QDs and bulk samples exhibit faster charge transfer compared to smaller dots [2].

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) spatially maps charge transfer rates at QD-microbe interfaces by tracking photoluminescence decay [7]. This technique revealed two distinct electron transfer mechanisms in CdSe QD-microbe systems: a faster pathway (1.5×10⁹ s⁻¹) with fewer acceptors and a slower pathway (4.1×10⁸ s⁻¹) with more acceptors, assigned to indirect and direct transfer mechanisms respectively [7].

Electrochemical Spectroscopy using cyclic voltammetry characterizes charge transfer processes in QD/redox ligand assemblies by scanning the Fermi level while monitoring current [4]. This approach identifies distinct signals corresponding to charge injection into the QD conduction band and electron transfer through redox ligand states.

Device-Level Characterization

Field-effect transistors (FETs) provide a platform for evaluating charge transport properties under controlled conditions. Studies on InP QDs with hybrid S²⁻/N³⁻ ligand exchange demonstrated electron mobilities of 0.45 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹, approximately 10 times higher than previous reports [6]. This improvement resulted from enhanced interdot coupling and reduced trap-state densities.

Photovoltaic device characterization reveals how ligand engineering impacts solar cell performance. PbS QD solar cells employing hybrid halide/pyridine passivation achieved power conversion efficiencies of 6.8% compared to 5.3% for halide-only treated cells, with improvements in all device parameters (Jsc, Voc, FF) due to better surface passivation and charge extraction [5].

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Studying Charge Transport in QD Solids

| Technique | Physical Principle | Timescale Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core-Hole Clock Spectroscopy | Core-hole lifetime as internal clock | Attoseconds (10⁻¹⁸ s) | Charge transfer times, electron delocalization rates |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging | Photoluminescence decay dynamics | Picoseconds to nanoseconds (10⁻¹²-10⁻⁹ s) | Charge transfer rates, acceptor densities, spatial heterogeneity |

| Cyclic Voltammetry | Current response to potential sweep | Milliseconds to seconds (10⁻³-10⁰ s) | Redox potentials, charge injection rates, transport mechanisms |

| Field-Effect Transistor | Gate-modulated conductivity | Steady-state to microseconds | Carrier mobility, carrier density, trap states |

| Transient Absorption | Pump-probe carrier dynamics | Femtoseconds to nanoseconds (10⁻¹⁵-10⁻⁹ s) | Carrier lifetimes, recombination rates, trap states |

Ligand Engineering Strategies and Protocols

Ligand Exchange Methodologies

Successful ligand engineering requires precise control over the replacement of native synthetic ligands with functional counterparts:

Solution-Phase Exchange involves exposing QDs to excess new ligands in solution before film formation. This approach typically achieves more complete exchange but risks colloidal instability. For InP QDs, solution-based exchange with S²⁻ enabled effective removal of native ligands while controlling n-doping [6].

Solid-State Exchange employs ligand solutions to treat pre-formed QD films, preserving film integrity while modifying surface chemistry. Sequential treatment with tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI) and pyridine on PbS QD films created hybrid-passivated systems with improved morphology and reduced cracking [5].

Hybrid Multistep Exchanges combine both approaches for optimal results. For InP QDs, researchers developed a strategy with solution-based S²⁻ exchange followed by solid-state N³⁻ treatment, further enhanced by selenium capping to achieve record mobilities [6].

Ligand Classification and Selection

- Short Organic Ligands: Molecules like pyridine and ethanedithiol reduce interparticle distance while providing moderate passivation. Their small size enables tight QD packing but may offer incomplete surface coverage [5].

- Inorganic Ligands: Halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻) and chalcogenides (S²⁻, Se²⁻) provide strong metal coordination and excellent electronic passivation. In PbS QDs, iodine ions effectively coordinate with Pb atoms, reducing trap states and enhancing conductivity [5] [6].

- Redox-Active Ligands: Molecules like ferrocene carboxylate introduce accessible electronic states that actively mediate charge transport through self-exchange reactions [4]. In ZnO-FcCOO⁻ assemblies, this created two complementary transport pathways: QD band conduction and ligand-mediated hopping.

- Hybrid Ligand Systems: Combinations of different ligand types address multiple requirements simultaneously. The TBAI-pyridine hybrid on PbS QDs enabled both excellent passivation (from pyridine) and high charge mobility (from iodide) [5].

Diagram 2: Charge Transport Pathways Mediated by Different Ligand Types. This diagram illustrates how various ligand classes facilitate or hinder electron transfer between quantum dots.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Ligand Engineering

Table 3: Key Reagents for Quantum Dot Surface Engineering

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Example | Effect on Charge Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrabutylammonium Iodide (TBAI) | Halide source for inorganic passivation | PbS QD solar cells [5] | Enhances carrier mobility, reduces trap states |

| Pyridine | Short organic ligand for distance reduction | Hybrid passivation of PbS QDs [5] | Decreases interdot distance, improves packing |

| Ferrocene Carboxylic Acid | Redox-active ligand for active transport | ZnO QD assemblies [4] | Enables self-exchange chain reaction transport |

| Ammonium Sulfide | Inorganic sulfide source for passivation | InP QD field-effect transistors [6] | Enhances interdot coupling, controls doping |

| Sodium Azide | Nitrogen source for surface modification | InP QD thin films [6] | Further reduces trap states, improves mobility |

| Selenium Powder | Chalcogenide source for surface capping | InP QD device optimization [6] | Increases carrier diffusion length, reduces traps |

Impact on Device Performance and Applications

Photovoltaic Devices

In quantum dot solar cells, ligand engineering directly impacts all key performance parameters. PbS QD solar cells employing hybrid TBAI-pyridine passivation demonstrated remarkable improvements: power conversion efficiency increased from 5.3% to 6.8%, attributed to better surface passivation, reduced trap-assisted recombination, and enhanced charge extraction [5]. The ligand exchange process critically influences the open-circuit voltage (Voc) deficit relative to the bandgap, with insufficient passivation leading to sub-bandgap states that limit Voc [5].

For CsPbI3 perovskite QD solar cells, a innovative "solvent-mediated ligand exchange" approach enabled exceptional 16.53% efficiency - a record for inorganic QD photovoltaics at the time [8]. By optimizing the solvent environment for ligand substitution, researchers achieved more complete replacement of insulating native ligands while maintaining QD structural integrity, significantly reducing defect density and improving carrier mobility.

Electronic and Optoelectronic Devices

Field-effect transistors serve as sensitive probes of charge transport in QD solids. InP QD FETs with hybrid S²⁻/N³⁻ ligand exchange and Se capping demonstrated electron mobilities of 0.45 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹, approximately 10× higher than previous reports, with on-off current ratios of 10³-10⁴ [6]. These improvements stemmed from lower trap-state densities and longer carrier lifetimes, yielding a four-fold increase in carrier diffusion length.

In nano-bio hybrid systems, ligand engineering enables charge transfer between QDs and biological entities. CdSe QDs with BF4⁻ surface moieties transferred electrons to Shewanella oneidensis microbes at rates of 10⁸ to 10¹⁰ s⁻¹, with the ligand shell determining the proximity requirements for direct versus indirect electron transfer mechanisms [7].

Surface chemistry represents the defining frontier in quantum dot solids research, transitioning from a peripheral consideration to a central design parameter. The traditional view of ligands as passive spacers has evolved to encompass their roles as active mediators of charge transport, structural directors, and electronic modifiers. The correlation between ligand properties (length, functionality, binding group) and charge transport parameters (mobility, recombination, conductivity) provides a rational foundation for materials design.

Future developments will likely explore increasingly sophisticated ligand architectures including multi-functional systems, stimuli-responsive ligands, and hierarchically structured shells that address multiple challenges simultaneously. The integration of computational screening with high-throughput experimental synthesis will accelerate the discovery of optimal ligand chemistries for specific applications. As these advances mature, quantum dot solids with engineered surface chemistry will enable new generations of efficient, solution-processable electronic and energy conversion devices that leverage the unique properties of nanoscale materials.

The pursuit of high-performance quantum dot (QD) solids for optoelectronic devices represents a central theme in modern materials science. These solids, which are dense films of semiconductor nanocrystals, form the active layer in a new generation of solar cells, photodetectors, light-emitting diodes, and memory devices [9] [10]. A critical and often determining factor in their performance is the efficiency of charge transport between individual quantum dots. This transport is governed not by the intrinsic properties of the nanocrystals alone, but predominantly by the molecular-scale environment surrounding them—specifically, the organic surface ligands [11].

Surface ligands are molecular chains that passivate the QD surface, preventing aggregation and ensuring colloidal stability during synthesis. However, when QDs are assembled into a solid film, these same ligands become the medium through which charges must travel to hop from one dot to the next. Long-chain, aliphatic ligands—such as oleic acid (OA) and trioctylphosphine (TOP)—which are ubiquitous in colloidal synthesis, create a significant physical and electronic barrier to this process. They act as insulating spacers, forcing charge carriers to undergo quantum mechanical tunneling through a potential barrier, thereby rendering the QD solid an electrical insulator [11].

This article provides an in-depth technical examination of the insulator-conductor transition in quantum dot solids, focusing on the fundamental role of long-chain ligands in creating a tunneling barrier. We will explore the underlying mechanisms, quantify the impact of various ligand treatments, and detail the experimental methodologies that enable researchers to actively engineer charge transport properties, thereby transforming an insulating QD solid into a conductive functional material.

The Fundamental Mechanism: Ligands as Tunneling Barriers

The electronic structure of a single quantum dot is characterized by discrete, atom-like energy levels due to quantum confinement. When QDs are brought into close proximity to form a solid, their wavefunctions can overlap, allowing for the possibility of band-like transport. However, this ideal scenario is disrupted by the presence of surface ligands.

The Tunneling Barrier Model

Long-chain aliphatic ligands, typically with 8 to 18 carbon atoms, function as passive spacers between the conductive inorganic cores of the QDs [4] [11]. The charge transport mechanism in such a system is dominated by thermally activated hopping. The rate of electron hopping between two adjacent QDs is exponentially dependent on the center-to-center distance, which is the sum of the QD diameter and the ligand barrier length.

The tunneling probability through such a barrier can be described by the simplified relationship: [ T \propto e^{-\beta d} ] where ( T ) is the tunneling probability, ( d ) is the tunneling distance (dictated by the ligand chain length), and ( \beta ) is a decay constant that depends on the height of the potential barrier. The potential barrier height is directly related to the energy difference between the conductive states of the QD and the molecular orbitals of the ligand. For saturated hydrocarbons, this barrier is large, making them excellent insulators [11]. Consequently, the macroscopic conductivity ( \sigma ) of the QD solid follows a similar exponential decay: [ \sigma \propto e^{-\beta d} ] This exponential dependence means that even small reductions in the inter-dot spacing can lead to dramatic, orders-of-magnitude increases in film conductivity.

Consequences for Device Performance

The insulating nature of long-chain ligands has profound implications for QD-based devices. In photovoltaics, low conductivity leads to high series resistance, reducing the fill factor and overall power conversion efficiency. The charges photogenerated within the film must travel through a network of QDs interconnected by these tunneling barriers to be collected at the electrodes. If the hopping probability is too low, carriers recombine before they can be extracted, resulting in lost photocurrent [12]. Similarly, in memory devices and transistors, low carrier mobility impedes switching speeds and overall device performance [10]. Therefore, overcoming the insulating barrier presented by native long-chain ligands is a critical first step in realizing functional QD electronic devices.

Quantitative Evidence: Measuring the Ligand Impact

The influence of surface ligands on the electronic properties of QD solids is not merely qualitative; it can be directly measured and quantified through structural and optoelectronic characterization.

Ligand-Dependent Inter-Dot Spacing

Direct evidence of the spacer function of ligands comes from transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Studies on PbS QD films have precisely measured the reduction in interparticle distance following exchanges of long ligands for shorter ones.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Treatments on Inter-Dot Spacing in PbS QD Films

| Ligand Treatment | Backbone Description | Average Inter-Dot Distance (nm) | Change vs. Oleic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Long aliphatic (C18) | 10.2 ± 0.8 | Reference |

| 1,3-Benzenedithiol (1,3-BDT) | Conjugated aromatic | 9.3 ± 0.8 | -0.9 nm |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Short aliphatic (C2) | 7.8 ± 0.8 | -2.4 nm |

| Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short aliphatic (C3) | 7.6 ± 0.8 | -2.6 nm |

| Ammonium Sulfide ((NH₄)₂S) | Atomic sulfide | 6.7 ± 0.8 | -3.5 nm |

Data adapted from [11].

The data in Table 1 clearly demonstrates that ligand exchange directly modulates the physical separation between QDs. The replacement of oleic acid with shorter molecules like EDT and MPA reduces the inter-dot distance by approximately 25%, significantly lowering the tunneling barrier. The minimal spacing achieved with atomic ligands like sulfide illustrates the ultimate limit of this approach, bringing the QDs into near-contact [11].

Correlation with Optoelectronic Properties

The structural changes induced by ligand exchange have a direct and measurable impact on the optoelectronic properties of the film. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements reveal how ligand treatments alter charge carrier dynamics.

Films with long, insulating ligands exhibit longer photoluminescence (PL) lifetimes. This is because the excited electron-hole pair (exciton) is spatially confined to a single dot, as the probability of tunneling apart is low. When shorter, conductive ligands are introduced, the PL lifetime typically decreases dramatically. This PL quenching is a signature of enhanced charge transfer between QDs; the exciton can now dissociate, with the electron and hole hopping to neighboring dots, where they may encounter non-radiative recombination centers or be extracted as current [11].

Furthermore, the performance of working devices validates this trend. Solar cells based on PbS QDs consistently show that exchanging oleic acid for shorter thiols like EDT or MPA leads to a substantial increase in photocurrent and overall efficiency, a direct consequence of improved charge carrier collection [12] [13].

Beyond Passive Spacers: Active and Hybrid Ligand Systems

The prevailing strategy to overcome the tunneling barrier has been to shorten the ligand or replace it with an inorganic atom. However, a paradigm shift is emerging, moving from viewing ligands as passive spacers to using them as active components in the charge transport process.

Redox-Active Ligands

A groundbreaking approach involves the use of redox-active ligands, which introduce distinct electronic states within the bandgap that can actively mediate charge transport. As demonstrated in ZnO quantum dot systems, ligands like ferrocene carboxylate (FcCOO⁻) provide an alternative pathway for charge movement [4].

In this model, illustrated in the diagram below, charge transport occurs via two complementary mechanisms:

- Direct Hopping: Electron transfer through the conduction band of the QDs.

- Self-Exchange: Charge transfer via the immobilized redox ligands, where a charge on one ligand site hops to an adjacent, unoccupied ligand site through a chain reaction.

This dual-pathway model was experimentally confirmed using an electrochemical gating technique, which showed that the rate of the self-exchange process could be rationally controlled by modulating the Fermi level and the surface coverage of the redox ligands [4]. This represents a shift from passive barrier reduction to active transport pathway engineering.

The Mobility-Invariant Regime and Trap Limitation

A critical insight from recent research is that simply improving the theoretical mobility by shortening ligands is not always sufficient. In many practical CQD films, the diffusion length (LD) of charge carriers is not limited by mobility but by the presence of a low density of severe trap states [12].

In this trap-limited regime, the diffusion length is governed by the average distance a carrier can travel before encountering a trap, not by how fast it can move. The relationship is given by ( LD \approx d \times \sqrt{N{hops}} ), where ( d ) is the dot-to-dot distance and ( N_{hops} ) is the number of hops a carrier can make before being trapped [12]. In this scenario, increasing the mobility (e.g., by shortening ligands) only brings the carrier to the trap faster, without extending the diffusion length. This explains why some high-mobility CQD solids do not yield high-efficiency photovoltaic devices. The focus, therefore, must expand to include defect passivation in addition to inter-dot coupling.

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange and Characterization

Engineering the insulator-conductor transition requires reliable and reproducible experimental protocols. The following sections detail standard methodologies for ligand exchange and subsequent characterization.

Solid-State Ligand Exchange

This is the most common method for fabricating conductive QD films and involves a two-step process: film deposition with native ligands, followed by in-situ ligand exchange.

Detailed Protocol:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the substrate (e.g., ITO-glass, SiO₂/Si) with oxygen plasma or UV-ozone treatment to ensure a hydrophilic, clean surface.

- QD Film Deposition: Spin-coat a concentrated solution of QDs (capped with oleic acid or similar long ligands) in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene, octane) onto the substrate. Multiple layers may be spun to achieve the desired thickness, with mild annealing (e.g., 70°C for 5-10 minutes) between layers to remove solvent.

- Ligand Exchange Immersion: Immerse the film in a 0.01 - 0.1 M solution of the new, short ligand in a polar solvent (e.g., acetonitrile for EDT, methanol for MPA). The immersion time can vary from a few seconds to several minutes, depending on the ligand and film thickness.

- Rinsing and Drying: Immediately after immersion, rinse the film thoroughly with the same polar solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) to remove unbound ligand and reaction byproducts. Dry the film under a stream of nitrogen or with a brief anneal (e.g., 80-100°C for 1-5 minutes).

In-Solution Ligand Exchange

This method involves performing the ligand exchange on the QDs while they are still in solution, prior to film deposition. This can lead to more uniform ligand coverage and higher quality films.

Detailed Protocol:

- Precipitation and Redispersion: Precipitate the pristine QDs from their native solution by adding a non-solvent (e.g., ethanol or acetone). Centrifuge the mixture to obtain a pellet, and decant the supernatant.

- Ligand Exchange: Redisperse the QD pellet in a solution containing the new ligand (e.g., a chlorothiol in toluene). The concentration of the ligand is typically in large excess compared to the estimated number of surface sites on the QDs.

- Incubation: Stir or shake the mixture for a period ranging from hours to days to allow for complete ligand exchange.

- Purification: Precipitate and centrifuge the QDs again to remove the displaced native ligands and excess free ligands. Redisperse the final product in a suitable solvent for film deposition.

This method, particularly with robust ligands like chlorothiols, has been shown to produce films with lower trap densities, as the QDs are never exposed to a bare, unprotected surface during processing [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Ligand Engineering Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Native long-chain (C18) insulating ligand; provides colloidal stability. | Standard ligand from synthesis; reference point for insulating behavior [11]. |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Short-chain (C2) dithiol ligand; significantly reduces inter-dot distance. | Common solid-state exchange ligand; induces conductivity in PbS films [11] [12]. |

| Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short-chain (C3) ligand with thiol and carboxylic acid groups. | Used in PV devices; can bind in a bidentate fashion to PbS QDs [11] [12]. |

| Ferrocene Carboxylic Acid | Redox-active ligand; provides active charge transport states. | Enables self-exchange charge transport pathway in ZnO QD films [4]. |

| Ammonium Sulfide ((NH₄)₂S) | Inorganic atomic ligand; minimizes inter-dot spacing. | Creates inorganically interconnected QD solids with minimal tunneling barrier [11]. |

| Chlorothiols (e.g., 2-Chloroethanethiol) | In-solution passivation ligand; forms strong bond with QD surface. | Provides robust passivation from solution to film, reducing trap states [12]. |

| Acetonitrile & Methanol | Polar solvents for ligand exchange solutions and rinsing. | Used to process EDT and MPA solutions, respectively; do not dissolve the QD film. |

The transition of a quantum dot solid from an insulator to a conductor is a process meticulously engineered at the molecular level, primarily through the strategic manipulation of surface ligands. Long-chain, aliphatic ligands unequivocally create a formidable tunneling barrier that impedes charge transport, defining the insulating state. The primary strategy to overcome this has been ligand exchange with shorter molecules or atomic species, which reduces the inter-dot spacing and lowers the tunneling barrier.

However, contemporary research has revealed a more nuanced picture. The emergence of redox-active ligands introduces a paradigm where the ligand shell is not an obstacle to be minimized but an active medium for charge transport. Furthermore, the understanding of trap-limited transport highlights that maximizing mobility is insufficient without concurrently passivating mid-gap states that act as recombination centers. The future of high-performance QD solids lies in integrated optimization strategies that combine ligand engineering, interface engineering, and defect passivation to simultaneously enhance electronic coupling and maximize carrier lifetime. This holistic approach, potentially guided by machine learning for materials discovery, will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of quantum dot solids in next-generation optoelectronic devices.

The electronic and optical properties of semiconducting nanocrystals, or quantum dots (QDs), deviate significantly from their bulk counterparts due to quantum confinement. When the physical size of a semiconductor particle becomes comparable to or smaller than the Bohr exciton radius, the motion of charge carriers (electrons and holes) is spatially confined. This confinement quantizes the energy levels, leading to size-dependent properties, a phenomenon central to their application in optoelectronics and biomedicine. This whitepaper details the fundamental principles of quantum confinement and the Bohr exciton radius, framing them within the critical context of charge transport in quantum dot solids, where surface ligand engineering is a key determinant of device performance.

Core Principles: The Bohr Exciton Radius

The Bohr exciton radius ((a_B)) is the natural length scale for quantifying the onset of quantum confinement. It represents the average physical separation between the electron and hole in a bound electron-hole pair (an exciton) in the bulk semiconductor material.

The Bohr exciton radius is given by: [ aB = \frac{4\pi\epsilon \hbar^2}{\mu e^2} ] where (\epsilon) is the dielectric constant of the semiconductor, (\hbar) is the reduced Planck's constant, (\mu) is the reduced mass of the exciton ((\frac{1}{\mu} = \frac{1}{me^} + \frac{1}{m_h^})), and (e) is the electron charge.

When the radius ((R)) of the QD is less than (aB), strong confinement occurs, where both the electron and hole are independently confined. This results in a discretization of the energy states and a widening of the band gap ((Eg)) with decreasing particle size. The relationship is often approximated by the Brus equation for spherical QDs: [ E{QD} = Eg + \frac{\hbar^2 \pi^2}{2R^2} \left( \frac{1}{me^*} + \frac{1}{mh^*} \right) - \frac{1.8e^2}{4\pi\epsilon R} ] where the second term represents the quantum localization energy and the third term accounts for the Coulomb attraction.

Table 1: Bohr Exciton Radii and Confinement Regimes for Common Quantum Dot Materials

| Semiconductor Material | Bulk Band Gap (eV) | Bohr Exciton Radius, (a_B) (nm) | Strong Confinement Regime (R < (a_B)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe | 1.74 | ~5.6 | R < ~5.6 nm |

| PbS | 0.41 | ~18 | R < ~18 nm |

| CdTe | 1.49 | ~7.5 | R < ~7.5 nm |

| ZnO | 3.37 | ~2.0 | R < ~2.0 nm |

| Perovskite (MAPbI(_3)) | ~1.6 | ~2-5 | R < ~2-5 nm |

The Ligand-Transport Nexus in Quantum Dot Solids

In a QD solid film, individual dots are passivated by organic surface ligands. The length and chemical nature of these ligands are not merely a synthetic detail; they are critical design parameters that directly influence inter-dot coupling and charge transport, which is the thesis context of this guide.

- Short Ligands: Promote closer inter-dot spacing, enhancing electronic coupling and wavefunction overlap. This leads to higher charge carrier mobility but can also increase the probability of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), potentially competing with charge transport.

- Long Ligands: Act as thicker insulating barriers between QDs. While they provide excellent colloidal stability and passivation, they severely hinder charge transport by increasing the tunneling distance, thereby reducing mobility.

Table 2: Impact of Surface Ligand Chain Length on QD Solid Properties

| Ligand Type (Example) | Approx. Length | Inter-dot Spacing | Electronic Coupling | Charge Mobility | Stability & Processability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | ~1.8 nm | Medium | Medium | Medium | High |

| Butylamine (BA) | ~0.7 nm | Small | High | High | Medium |

| Octadecylphosphonic Acid (ODPA) | ~2.3 nm | Large | Low | Low | Very High |

| Ligand Exchange (e.g., SCN⁻) | Atomic/Ionic | Minimal | Very High | Very High | Requires matrix support |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesizing Size-Tuned CdSe Quantum Dots (Hot-Injection Method)

Objective: To produce a series of CdSe QDs with diameters from 2-6 nm to demonstrate quantum confinement.

Materials: Cadmium oxide (CdO), Selenium (Se) shot, Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), Hexadecylamine (HDA), Trioctylphosphine (TOP), Oleic acid (OA), 1-Octadecene (ODE).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Load a mixture of CdO (0.0128 mmol), OA (0.2 mL), and ODE (5 mL) into a 25 mL three-neck flask. Heat to 150°C under argon until a clear solution forms.

- Selenium Stock: In a glove box, dissolve Se shot (0.1 mmol) in TOP (0.5 mL) and ODE (1.5 mL) to form a TOP-Se solution.

- Injection & Growth: Raise the temperature of the cadmium solution to 300°C under vigorous stirring. Rapidly inject the TOP-Se solution. The growth temperature and time control the final size.

- For 2 nm dots: Inject at 240°C, quench immediately.

- For 4 nm dots: Inject at 300°C, grow for 60 seconds.

- For 6 nm dots: Inject at 300°C, grow for 10 minutes.

- Purification: Cool the reaction flask to 60°C. Add toluene and precipitate the QDs with ethanol. Centrifuge and redisperse in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane).

Protocol: Ligand Exchange and Solid Film Fabrication

Objective: To create QD solid films with controlled inter-dot spacing using ligands of varying chain lengths.

Materials: As-synthesized QDs (e.g., CdSe-OA), Ligand solutions (e.g., Butylamine, Octadecylamine, 0.1 M Potassium Thiocyanate in methanol), Solvents (Methanol, Butanol, Toluene).

Procedure:

- Ligand Exchange: Precipitate 1 mL of the purified QD solution with methanol. Centrifuge and discard the supernatant.

- Redisperse the QD pellet in 2 mL of a solution containing the new ligand (e.g., 50 µL butylamine in 2 mL methanol). Vortex and shake for 1 hour.

- Precipitate the ligand-exchanged QDs with a non-solvent (e.g., butanol), centrifuge, and redisperse in an appropriate solvent (e.g., butanol for short ligands, toluene for long ligands).

- Film Fabrication: Deposit the QD solution onto a pre-cleaned substrate (e.g., glass/ITO) via spin-coating (e.g., 2000 rpm for 30 seconds) or drop-casting. Anneal the film at 80-100°C for 10 minutes to remove residual solvent.

Protocol: Characterizing Confinement and Charge Transport

Objective: To measure the optical properties and electrical performance of the QD films.

Materials: UV-Vis-NIR Spectrophotometer, Photoluminescence (PL) Spectrometer, Field-Effect Transistor (FET) test structure with pre-patterned electrodes, Semiconductor Parameter Analyzer.

Procedure:

- Optical Characterization:

- Dilute a sample of each QD size in toluene and record the UV-Vis absorption spectrum. The position of the first excitonic peak is used to determine the QD size using established calibration curves.

- Record the PL spectrum to determine the emission maximum and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), which indicates size distribution.

- Structural Characterization: Use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to verify QD size, shape, and monodispersity.

- Charge Transport Measurement:

- Fabricate a bottom-gate, top-contact FET using the ligand-exchanged QD film as the channel.

- Using a semiconductor parameter analyzer, sweep the gate voltage ((VG)) at a fixed drain-source voltage ((V{DS})).

- Extract the field-effect mobility ((\mu{FET})) from the slope of the transfer curve ((I{DS}) vs (VG)) in the saturation regime using the standard MOSFET equation: (I{DS} = (\frac{W}{2L}) Ci \mu{FET} (VG - VT)^2), where (C_i) is the gate dielectric capacitance, and (W/L) is the channel width-to-length ratio.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Quantum Confinement Effect (77 chars)

Diagram 2: Ligand Length Impact on Transport (75 chars)

Diagram 3: QD Solid Fabrication Workflow (73 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for QD Synthesis and Fabrication

| Item | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| Cadmium Oxide (CdO) | Cadmium precursor for high-temperature synthesis of Cd-based QDs. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | A common coordinating solvent and surfactant that controls QD growth and passivates the surface. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | A non-coordinating, high-boiling-point solvent used in place of traditional coordinating solvents. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | A common ligand that binds to the QD surface, providing colloidal stability and size control. |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | A strong coordinating solvent used to prepare precursor stocks (e.g., TOP-Se, TOP-S). |

| Potassium Thiocyanate (KSCN) | A source of short, inorganic SCN⁻ ligands for ligand exchange to create strongly coupled QD solids. |

| Butylamine / Octadecylamine | Short- and long-chain amine ligands used to systematically study the effect of ligand length on transport. |

| Zinc Acetate / Zinc Oleate | Precursors for the fabrication of a ZnS or ZnO shell in core/shell QDs to enhance photoluminescence quantum yield. |

Colloidal nanocrystal quantum dots (QDs) assembled into solid-state films represent a promising class of semiconductors for next-generation, solution-processed electronic and optoelectronic devices. Their potential has been demonstrated in transistors, light-emitting diodes, solar cells, and photodetectors. Unlike bulk semiconductors, QD solids offer a multi-dimensional design space where electronic properties can be tuned by controlling quantum dot size, shape, composition, surface termination, and packing geometry [14]. Despite the commercial success of QDs as optical absorbers and emitters, applications relying on efficient charge transport have faced significant challenges due to the inability to predictively control their electronic properties [14]. The fundamental mechanism governing charge transport in these materials has remained elusive, hindering the development of predictive models for device design.

Central to understanding charge transport in QD solids is the recognition that charge carriers (electrons and holes) significantly interact with the atomic lattice of the nanocrystals and their surface environments. When a charge carrier localizes on an individual QD, it induces structural distortions through electrostatic interactions—primarily with the surface ligands. This coupled entity of charge carrier and lattice distortion forms what is known as a polaron [14]. The energy required to rearrange the atomic structure during charge transfer between neighboring QDs, termed the reorganization energy (λ), is substantial (tens to hundreds of meV) [14]. This polaron formation, combined with relatively weak electronic coupling between quantum dots, dictates that charge transport in typical QD solids does not occur through conventional band-like transport but rather through a phonon-assisted hopping process [14]. This whitepaper explores the physical principles of the polaron hopping model and examines how surface ligand engineering serves as a powerful tool to manipulate this charge transport mechanism.

The Physical Basis of Polaron Hopping

Polaron Formation and Reorganization Energy

The journey of a charge through a QD solid begins with its localization on an individual nanocrystal. Large-scale ab initio calculations on lead sulfide (PbS) QDs with iodine ligands have revealed that introducing an extra electron or hole induces measurable structural changes. Specifically, the Pb-ligand bonds on the (111) surfaces expand or contract, while the Pb-S bond lengths in the core remain largely unaffected [14]. Although these bond length changes are small (up to 0.2% of the nominal bond length), the collective reorganization energy λ is significant.

The reorganization energy λ decreases with increasing QD size due to two key factors: a reduced carrier density across the nanocrystal and an increased number of ligands sharing the structural distortion [14]. This size-dependent reorganization energy plays a critical role in determining charge transfer rates between quantum dots.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Polaron Hopping Transport

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Impact on Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganization Energy | λ | Energy for structural rearrangement during charge transfer | Large λ (10s-100s meV) inhibits transfer; decreases with QD size |

| Electronic Coupling | Vct | Quantum mechanical overlap between neighboring QD states | Small Vct compared to λ leads to localized polarons |

| Transfer Rate | kct | Speed of charge hopping between QDs | Dictated by Marcus non-adiabatic model; peaks when ΔE ≈ -λ |

Electronic Coupling Between Quantum Dots

The electronic coupling, Vct, between neighboring QDs determines the degree of wavefunction overlap and thus the probability of charge transfer. In assembled PbS QD superlattices, the coupling strength depends strongly on the relative orientation of adjacent nanocrystals. Calculations show that coupling in the [100] direction is approximately an order of magnitude larger than in the [111] direction, as quantum confinement strongly localizes charge carriers away from the ligand-rich [111] facets [14].

Crucially, across a wide range of QD sizes and inter-dot spacings, Vct remains more than an order of magnitude smaller than the reorganization energy λ [14]. This relationship confirms that charge carriers exist as polarons localized on individual QDs and that transport occurs through phonon-assisted hopping between these localized states rather than through delocalized band transport.

The Phonon-Assisted Charge Transfer Mechanism

The significant disparity between Vct and λ places polaron hopping firmly in the non-adiabatic regime described by Marcus electron transfer theory. In this framework, charge transfer requires thermal activation to overcome the reorganization energy barrier. The atomic vibrations (phonons) of the Pb-ligand bonds, which occur at energies below ~15 meV, provide the necessary thermal energy to drive this process [14].

At temperatures above approximately 175 K, the charge transfer rate kct follows a Marcus-type expression [14]:

Where NP represents the number of degenerate product states, ΔE is the energy difference between initial and final states (including contributions from an applied electric field or energetic disorder), kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature. This model predicts room-temperature charge transfer times on the order of 10-100 picoseconds for PbS QD solids, consistent with experimental measurements [14].

Surface Ligands as a Control Parameter for Charge Transport

Ligand Engineering Fundamentals

Surface ligands play a dual role in QD solids: they passivate surface states to prevent charge trapping and mediate electronic coupling between neighboring nanocrystals. The nature of the ligand-QD bond and the physical properties of the ligand itself directly influence the charge transport mechanism. Ligands are typically classified as X-type (anionic, e.g., halides, thiols, carboxylates) or L-type (Lewis bases, e.g., amines, phosphines) [14].

In PbS QD systems, the use of X-type ligands leads to polaron formation through electrostatic interaction of the charge carrier with the negatively charged functional groups of the ligands [14]. The structural reorganization associated with polaron formation primarily occurs in the metal-ligand bonds, making the ligand identity and bonding geometry crucial determinants of the reorganization energy λ.

Ligand Chain Length and Electronic Coupling

The length of the surface ligand alkyl chain directly impacts the electronic coupling Vct between quantum dots by determining the inter-dot separation. Studies on InP/ZnSe/ZnS QDs with systematically varied ligand chain lengths (oleic acid [OA], decanoic acid [DA], and hexanoic acid [HA]) demonstrate that shorter ligands significantly enhance charge injection efficiency [15]. Chronoamperometry measurements reveal that decreasing the carbon atom count in the capping ligand from 18 (OA) to 6 (HA) increases the integrated current density by a factor of 1.5 [15]. This enhancement is attributed to the reduced energy barrier for charge transport with shorter ligand chains.

Table 2: Ligand-Dependent Charge Transport Properties

| QD Material | Ligand Type | Chain Length/Type | Transport Property | Effect vs Long Chain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InP/ZnSe/ZnS | Carboxylic acids | C18 vs C6 | Current density | 1.5× increase [15] |

| PbS | n-butylamine | ~0.6 nm | Conductivity | 180× vs. drop-cast films [16] |

| ZnO | Ferrocene carboxylate | Redox active | Transport mode | Adds self-exchange pathway [4] |

| PbS | Iodine | X-type inorganic | Reorganization energy | Polaronic transport [14] |

Furthermore, ligand chain length affects inter-QD energy transfer dynamics, which competes with charge transport in optoelectronic devices. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) of InP/ZnSe/ZnS QD solids reveals that energy transfer population and efficiency between neighboring QDs are proportional to surface ligand chain lengths [15]. X-ray diffraction analysis confirms that shorter alkyl ligands result in weaker interligand van der Waals interactions, reducing Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and potentially favoring charge transport over energy transfer [15].

Advanced Ligand Strategies

Beyond simple alkyl chains, researchers have developed sophisticated ligand engineering strategies to enhance charge transport in QD solids:

Hybrid Ligand Exchange: Combining solution-based exchange with S²⁻ and solid-state exchange with N³⁻ for InP QDs enhances interdot coupling and controls n-doping, resulting in electron mobilities of 0.45 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹—approximately 10 times higher than previously reported devices [6].

Redox-Active Ligands: Incorporating ferrocene carboxylate ligands on ZnO QDs introduces an alternative charge transport pathway through self-exchange reactions between immobilized redox centers [4]. This approach represents a shift from using ligands as passive spacers to employing them as active electronic components that directly participate in charge transport.

Inorganic Ligands: Replacing organic ligands with shorter inorganic ligands (e.g., halides, chalcogenides) significantly reduces inter-dot spacing and enhances electronic coupling. Surface modification of InP QDs with thin Se overlayers lowers trap-state densities and extends carrier diffusion lengths [6].

Experimental Evidence and Characterization Techniques

Nano-patterning for Reduced Disorder

Understanding the intrinsic charge transport properties of QD solids requires minimizing structural disorder that often obscures the fundamental mechanisms. Nano-patterning techniques have been developed to fabricate QD solids free of cracking, clustering, and grain boundaries [16]. These structurally optimized arrays exhibit conductivities 180 times higher than drop-cast films of the same QD material [16].

In narrow (70 nm) nano-patterned PbS QD solids with n-butylamine ligands, researchers have observed exceptionally large conductance noise exceeding 100% of the average current [16]. This noise displays a power-law spectral density rather than characteristic 1/f behavior, indicating complex dynamics of charge trapping and release rather than simple shot noise. The noise magnitude grows with increasing conductance under applied bias, gate voltage, and temperature, suggesting that the transport occurs through stochastic quasi-one-dimensional percolation paths [16].

Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Characterization

Multiple experimental techniques provide insights into the polaron hopping mechanism and ligand effects:

Chronoamperometry: This electrochemical technique monitors current from Faradaic processes at electrodes over time, revealing that shorter ligand chains significantly enhance charge injection efficiency into InP/ZnSe/ZnS QDs [15].

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM): By mapping spatial variations in photoluminescence lifetimes, FLIM quantifies inter-QD energy transfer efficiency, which competes with charge transport and is strongly influenced by ligand chain length [15].

Single-QD Electrophoresis: Advanced laser scanning microscopy combined with high-field electrophoresis enables measurement of elementary charges on individual QDs in their native liquid environment, providing unprecedented insight into charging heterogeneity at the single-particle level [17].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for QD Charge Transport Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| QD Core Materials | PbS, InP, ZnO, CdSe/CdS | Base semiconductor determining band structure and quantum confinement [14] [4] [17] |

| Short Alkyl Ligands | n-butylamine, hexanoic acid | Reduce inter-dot distance, enhance electronic coupling V_ct [16] [15] |

| Inorganic Ligands | Iodine, sulfide, selenide | Maximize electronic coupling through minimal spacing and covalent bonding [14] [6] |

| Redox-Active Ligands | Ferrocene carboxylate | Introduce alternative charge transport via self-exchange reactions [4] |

| Solvents | Acetonitrile, dichloromethane, dodecane | Medium for ligand exchange and assembly; affects film morphology [4] [17] |

| Stabilizers | Polyisobutylene succinic anhydride | Maintain colloidal stability during single-QD measurements [17] |

The polaron hopping model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding charge transport in quantum dot solids as a phonon-assisted process. The critical relationship Vct << λ establishes that charge carriers form polarons localized on individual QDs, requiring thermal activation for inter-dot transfer. Surface ligand engineering emerges as a powerful strategy for controlling this transport mechanism, primarily through tuning both the reorganization energy λ (via the ligand-QD bond properties) and the electronic coupling Vct (via inter-dot spacing and chemical functionality).

Future research directions will likely focus on sophisticated ligand design that goes beyond simple spacing functions. Redox-active ligands that provide alternative charge transport pathways [4], hybrid exchange strategies that enhance coupling while minimizing disorder [6], and precise nano-patterning techniques that eliminate structural defects [16] represent promising approaches to achieving more predictable and efficient charge transport in QD solids. A fundamental understanding of the polaron hopping mechanism and its dependence on surface chemistry will accelerate the development of next-generation QD-based electronic devices with tailored performance characteristics.

Soft and Hard Acid-Base (HSAB) Theory as a Guide for Ligand Selection and Exchange

The Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory, introduced by Ralph Pearson, provides a powerful conceptual framework for predicting the stability and reactivity of Lewis acid-base pairs [18]. This principle classifies chemical species based on their polarizability, not their strength, dividing them into "hard" or "soft" categories [19]. In quantum dot (QD) science, this translates to a critical design rule: metal centers (acids) interact most strongly and form more stable complexes with ligands (bases) of matching character—hard with hard, soft with soft [18] [20]. This selective affinity is the cornerstone of rational ligand design for controlling surface chemistry in quantum dot solids, a factor that directly governs their charge transport properties [1] [21].

The surface of a QD is a dynamic interface where the inorganic core meets its organic ligand environment. The nature of this interface dictates the electronic coupling between neighboring dots in a solid film, influencing everything from carrier mobility to environmental stability [3] [1]. Applying HSAB theory allows researchers to move beyond trial-and-error approaches. By rationally selecting ligands based on the hardness or softness of the surface metal atoms (e.g., Pb²⁺ in PbS QDs), one can predict bonding stability, anticipate the kinetics of ligand exchange, and ultimately tailor materials for enhanced performance in devices like photovoltaics and photodetectors [2] [21].

Fundamental Principles of HSAB Theory

The classification of a species as "hard" or "soft" depends on its intrinsic electronic properties, primarily its polarizability—that is, the ease with which its electron cloud can be distorted [19] [18].

Defining Characteristics

Hard acids and bases are typically small in ionic radius, have high charge states, and exhibit low polarizability. They form bonds that are predominantly ionic in nature [19] [18]. Their electron density is tightly held, making them less susceptible to deformation.

Soft acids and bases, in contrast, are generally larger, have lower charge states, and are highly polarizable. They tend to form bonds with significant covalent character [19] [18]. Their diffuse electron clouds are easily distorted, facilitating orbital overlap that leads to covalent bonding.

Table 1: Key Properties of Hard and Soft Acids and Bases

| Property | Hard Acids/Bases | Soft Acids/Bases |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic/Ionic Radius | Small | Large |

| Charge Density | High | Low |

| Polarizability | Low | High |

| Preferred Bonding | Ionic | Covalent |

| Electronegativity (Bases) | High | Low |

Classification of Common Species in QD Chemistry

Understanding the classification of specific metal ions and ligands is essential for applying HSAB theory [18].

Hard Acids: Characteristic hard acids include small, highly charged metal ions such as H⁺, Li⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, and Al³⁺. In the context of QDs, early transition metal ions in high oxidation states also fall into this category [19].

Soft Acids: These include metal ions with a low charge density and high polarizability. Notably, many metals used in QDs are soft or borderline acids. For example, Pb²⁺ is classified as a borderline acid, while Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺, and Au⁺ are typical soft acids [18]. The bulk metal atoms (M⁰) at a QD's surface also exhibit soft character [18].

Hard Bases: These feature small donor atoms with high electronegativity, such as oxygen or fluorine. Common examples are hydroxide (OH⁻), fluoride (F⁻), carbonate (CO₃²⁻), and carboxylate groups (RCOO⁻) like acetate [19] [18]. Water and ammonia are also hard bases.

Soft Bases: Soft bases contain large, highly polarizable donor atoms like sulfur, phosphorus, or iodine. Key examples are thiolate (RS⁻), iodide (I⁻), thiocyanate (SCN⁻), and phosphines (PR₃) [19] [18].

Table 2: Common Acids and Bases in Quantum Dot Surface Chemistry

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hard Acids | H⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Al³⁺ |

| Borderline Acids | Fe²⁺, Co²⁺, Pb²⁺, Zn²⁺ |

| Soft Acids | Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺, Ag⁺, Au⁺, Pt²⁺, Pd²⁺ |

| Hard Bases | H₂O, NH₃, OH⁻, F⁻, CH₃COO⁻, R-OH |

| Soft Bases | I⁻, R-S⁻ (Thiolates), SCN⁻, CO, PR₃ |

HSAB Theory in Quantum Dot Surface Chemistry

The surface of a quantum dot is composed of under-coordinated metal and chalcogenide ions, which act as Lewis acid and base sites, respectively. For lead chalcogenide QDs like PbS, the Pb²⁺ sites are borderline Lewis acids, while the S²⁻ sites are soft Lewis bases [18] [21]. This fundamental characteristic dictates the optimal ligand chemistry for effective passivation and property control.

Ligand Selection for Surface Passivation

Effective surface passivation requires satisfying the bonding preferences of both ionic constituents. According to HSAB theory, the borderline acidic Pb²⁺ sites show a strong thermodynamic preference for bonding with soft bases [18]. This explains the widespread effectiveness of soft thiolate-based ligands (R-S⁻) and iodide (I⁻) for passivating PbS QD surfaces [21]. These soft ligands form stable, covalent-like bonds with the lead atoms, reducing surface trap states and enhancing photoluminescence.

Conversely, the soft basic S²⁻ sites can be passivated by borderline or soft acids. In a practice known as Z-type passivation, metal halides like PbI₂ or CdI₂ are used, where the soft Pb²⁺ or Cd²⁺ ions bind to the sulfur sites [1] [21]. This co-passivation strategy—using a soft base for the metal sites and a soft acid for the chalcogen sites—creates a more robustly passivated and electronically stable QD surface.

Impact of Ligand Character on Charge Transport

The HSAB-driven selection of ligands directly impacts charge transport in QD solids through two primary mechanisms: trap state passivation and inter-dot coupling.

Trap State Passivation: An improperly passivated surface contains "dangling bonds" that act as electronic trap states, capturing charge carriers and impeding transport. Hard-soft mismatches (e.g., a hard base on a soft acid site) result in weak, labile bonds that readily desorb, creating traps. Using HSAB-predicted, complementary ligands ensures strong, stable bonding, which minimizes trap state density and reduces charge carrier recombination [3] [21]. This leads to longer carrier diffusion lengths, which is critical for high-performance devices like solar cells [2] [22].

Inter-Dot Coupling: The ligand shell acts as a physical and electronic barrier between QDs. Short, compact ligands chosen via HSAB principles allow for closer packing of QDs. This decreases the tunneling barrier width and enhances the electronic coupling between adjacent dots, facilitating band-like transport or more efficient hopping conduction [1]. For instance, replacing long, insulating oleic acid (a relatively harder base) with compact iodide (a soft base) on PbS QDs dramatically improves electron mobility in the solid state [1] [21].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Exchange

Ligand exchange is a critical process for replacing long-chain, insulating native ligands with shorter, charge-transport-enhancing ligands. The following protocols, grounded in HSAB principles, are standard in the field.

Solid-State Ligand Exchange Using Metal Iodides

This protocol describes the conversion of oleic acid-capped PbS QDs to iodide-capped QDs for high-mobility solids [2] [21].

Principle: The soft character of the I⁻ ion provides a strong thermodynamic driving force to displace the harder carboxylate group (oleate) from the borderline acidic Pb²⁺ surface sites.

Materials:

- PbS-OA QDs: Oleic acid-capped PbS quantum dots in toluene (e.g., 50 mg/mL).

- Lead Iodide (PbI₂): Serves as the source of I⁻ ligands and Z-type passivant.

- Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Butylamine: Polar solvent to dissolve PbI₂ and facilitate exchange.

- Toluene, Methanol, Acetone: Solvents for washing and precipitation.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 100 mg of PbI₂ in 5 mL of DMF or butylamine under vigorous stirring and mild heating (~50°C) until fully dissolved.

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat a thin film of PbS-OA QDs onto the desired substrate (e.g., glass/ITO).

- Exchange Reaction: Gently drop-cast the PbI₂ solution onto the QD film and allow it to stand for 30-60 seconds. The film color will change, indicating the exchange.

- Washing: Rinse the film thoroughly with pure DMF to remove excess PbI₂ and displaced oleic acid, followed by a rinse with methanol or acetone.

- Drying: Dry the film under a stream of nitrogen or with a brief anneal on a hotplate (~70°C).

Notes: The concentration of PbI₂, solvent choice, and reaction time are key optimization parameters. Butylamine can act as a co-ligand and may accelerate the exchange process.

Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange with Short-Chain Organic Ligands

This protocol replaces native ligands with short, conductive organic molecules in solution, prior to film deposition [3] [21].

Principle: A large excess of the incoming ligand (e.g., a soft thiol) shifts the equilibrium to favor displacement of the native ligand, forming a QD ink ready for processing.

Materials:

- PbS-OA QDs: In toluene or hexane.

- Incoming Ligand: e.g., 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT), 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), or tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI).

- Solvents: Acetonitrile, methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate (as non-solvents for precipitation).

Procedure:

- Precipitation: Add a non-solvent (e.g., acetone or methanol) to the pristine QD solution to precipitate the QDs. Centrifuge and discard the supernatant.

- Redispersion: Redisperse the QD pellet in a minimal amount of a solvent that is compatible with both the QDs and the incoming ligand (e.g., octane for EDT exchange).

- Ligand Addition: Add a large excess (e.g., 100-1000x molar relative to QDs) of the incoming ligand to the QD solution.

- Reaction: Stir the mixture for 1-24 hours at room temperature or with mild heating.

- Purification: Precipitate the ligand-exchanged QDs by adding a non-solvent, centrifuge, and discard the supernatant containing the displaced ligands.

- Final Ink: Redisperse the purified QD pellet in an appropriate solvent for film deposition (e.g., octane for EDT-capped QDs).

Notes: This method offers excellent control over the QD-to-ligand ratio. The choice of solvent for the final ink is crucial for achieving high-quality, crack-free films during deposition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful ligand engineering requires a set of well-defined reagents and materials. The following table details key components for a typical HSAB-guided research workflow in QD science.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function & HSAB Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Native surfactant (hard base); provides colloidal stability after synthesis. | Standard initial capping ligand for PbS, CdSe QD synthesis [21]. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Source of I⁻ (soft base) and Pb²⁺ for Z-type passivation. | Solid-state ligand exchange on PbS QD films for photovoltaics [2] [21]. |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Short-chain dithiol ligand (soft base). | Solution-phase exchange to create conductive PbS QD solids for FETs [21]. |

| Tetrabutylammonium Iodide (TBAI) | Source of "naked" I⁻ ions (soft base) in solution. | Halide anion exchange for QDs, improving electron transport [21]. |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short bifunctional ligand; thiol (soft base) binds QD, carboxylate aids solubility. | Creating water-soluble QDs or tuning surface polarity [21]. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Polar aprotic solvent (borderline base); dissolves metal halides. | Solvent for PbI₂ during solid-state ligand exchange [21]. |

| Butylamine | Polar solvent and L-type ligand (hard base); can coordinate to metal sites. | Accelerates ligand exchange processes [21]. |

Quantitative Data and Case Studies

The application of HSAB theory yields quantifiable improvements in QD device performance. Advanced spectroscopic techniques confirm the fundamental mechanisms at play.

Charge Transfer Dynamics

A 2025 study used Resonant Auger Spectroscopy (RAS) to probe ultrafast charge transfer dynamics in PbS QDs of different sizes and with different surface treatments [2]. The technique uses the core-hole lifetime as an internal clock to measure the rate at which an excited electron delocalizes from a Pb atom. The findings confirmed that larger QDs and those with optimized ligand environments (e.g., treated with PbI₂) exhibited faster charge transfer rates compared to smaller dots or poorly passivated references [2]. This directly links appropriate surface chemistry, guided by HSAB principles, to superior charge transport properties on the most fundamental timescales.

Photovoltaic Device Performance

The impact of HSAB-driven ligand selection is clearly demonstrated in the performance metrics of quantum dot solar cells (QDSCs). Devices utilizing inorganic ligands consistently outperform those with long-chain organic ligands.

Table 4: Impact of Ligand Choice on PbS Quantum Dot Solar Cell Performance

| Ligand Type | HSAB Classification | Typical Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Key Effect on Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Hard Base | <5% | High inter-dot resistance, insulating film [21]. |

| Lead Iodide (PbI₂) | Soft Base / Z-type | >10% | Excellent passivation, high electron mobility [2] [21]. |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Soft Base | ~8-10% | Good hole conduction, short ligand length [21]. |

| Combined Halide/Organic | Mixed | >11% (Record devices) | Balanced charge transport, superior passivation [21] [22]. |

HSAB theory provides an indispensable, predictive framework for navigating the complex landscape of quantum dot surface chemistry. By guiding the rational selection of ligands based on the hard/soft character of the QD surface atoms, researchers can directly control critical outcomes: bonding stability, trap state density, and electronic coupling. The experimental protocols and quantitative data summarized herein demonstrate that moving from hard-hard or hard-soft mismatches to thermodynamically favored soft-soft pairs—such as employing iodide or thiolates for PbS QDs—is a decisive strategy for achieving high-performance electronic and optoelectronic devices. As QD research progresses toward more complex architectures and integration, the principles of HSAB will remain a cornerstone for the rational design of advanced functional materials.

Ligand Engineering in Action: Strategies for Enhanced Charge Transport

In quantum dot (QD) solids, the organic ligand shell surrounding the inorganic core is not merely a passive stabilizer but a critical component determining charge transport efficiency. These surface ligands dictate interparticle spacing, passivate surface states, and ultimately govern electronic coupling between adjacent QDs. Conventional ligand exchange strategies strategically replace long, insulating native ligands with shorter organic or inorganic counterparts to "shorten the bridge" between quantum dots, thereby enhancing charge carrier mobility while maintaining colloidal stability. This process is fundamental to developing high-performance QD-based electronic devices, including photodetectors, solar cells, and light-emitting diodes. The following sections provide a technical examination of ligand exchange methodologies, quantitative performance comparisons, and practical protocols for implementation.

Core Principles: How Ligand Engineering Modulates Charge Transport

The Interparticle Distance Mechanism

The most direct impact of ligand exchange is on the physical separation between adjacent quantum dots. Long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) create substantial tunnel barriers that impede charge carrier hopping. Replacing them with shorter ligands dramatically reduces the interparticle distance, leading to an exponential increase in the wavefunction overlap between neighboring QDs. For instance, replacing oleylamine (approximately 5.0 nm interparticle distance) with sulfide ligands on InSb QDs shortened the interparticle distance to 1.5 ± 0.5 nm, significantly enhancing carrier mobility [23]. This reduction directly decreases the tunneling barrier height and width, facilitating more efficient electron hopping between quantum dots.

Electronic Coupling and Trap State Passivation

Beyond mere physical proximity, the chemical nature of the replacement ligands determines their ability to mediate electronic coupling and passivate surface states. Different ligand classes exhibit distinct functionalities:

- Inorganic Ligands: Materials like sulfide (S²⁻) or halides (Br⁻, I⁻) provide atomic-scale bridging and effective passivation of anionic surface sites. On InSb QDs, sulfide capping yielded better carrier mobility and lower trap density compared to bromine capping [23].

- Short-Chain Organic Ligands: Molecules like butylamine (BA) and ethanedithiol (EDT) reduce distance while maintaining some organic character for processing.

- Conjugated Organic Ligands: Ligands with π-conjugated systems (e.g., oligo-(phenylene vinylene)) can actively mediate charge transport through electronic delocalization [24].

- Redox-Active Ligands: Molecular species like ferrocene carboxylate introduce electronic states that provide an additional pathway for charge transport via self-exchange reactions [4].

Proper ligand selection must balance multiple factors: achieving close-packed QD solids, maintaining sufficient surface passivation to reduce trap-assisted recombination, and providing favorable energy level alignment for specific device applications.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Ligand Systems

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Different Ligand Classes in QD Solids

| Ligand Type | Specific Example | Interparticle Distance | Carrier Mobility Enhancement | Key Performance Metrics | Application Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic | Sulfide (S²⁻) | 1.5 ± 0.5 nm (from 5.0 ± 0.5 nm) | Precedence over Br⁻ capping | EQE: 18.5%; Low dark current (~nA cm⁻²) | InSb SWIR photodiodes [23] |

| Short Organic | Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Significant reduction | ~90% ligand exchange in ≤60 s | Rapid processing; Compatible with printing | PbS QD microstructures [25] |

| Redox Active | Ferrocene carboxylate | Not specified | Enables self-exchange transport | Two complementary charge transport pathways | ZnO QD assemblies [4] |

| Short Organic | Butylamine (BA) | Intermediate reduction | Improved morphology preservation | Prevents void defects in polymer:QD blends | PTB1:Pbs solar cells [26] |

Table 2: Impact of Ligand Exchange on Photovoltaic Device Parameters

| Ligand System | QD Material | Dark Current Density | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Response Speed | Stability Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfide-capped | InSb | ~nA cm⁻² at 0 V | 18.5% | Enhanced (vs. bromide-capped) | Not specified [23] |

| Bromide-capped | InSb | Higher than sulfide | Lower than sulfide | Slower (second-scale) | Not specified [23] |

| OA to MPA direct | PTB1:PbS | Not specified | Not specified | Severe film morphology changes | Non-ideal morphology [26] |

| OA to BA to MPA | PTB1:PbS | Not specified | Not specified | Preserved morphology | Maintained BHJ structure [26] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Ligand Exchange

Solid-State Ligand Exchange (SSLE) for PbS QD Microstructures

This protocol enables efficient ligand exchange on pre-deposited QD films, particularly suitable for patterned structures [25]:

- QD Film Preparation: Fabricate PbS QD microstructures via electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing using tetradecane as solvent for optimal spatial resolution. Achieve varying thicknesses (125-750 nm) through controlled printing loops.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Prepare a 0.2% (v/v) solution of ethanedithiol (EDT) in acetonitrile as the exchange medium.

- Exchange Process: Apply EDT solution to the printed QD microstructures for 60 seconds. This duration achieves approximately 90% replacement of native oleic acid ligands without structural damage.

- Rinsing and Drying: Rinse thoroughly with pure acetonitrile to remove displaced ligands and residual exchange solution. Dry under nitrogen flow. Critical Note: Prolonged exposures (>1 hour) cause systematic degradation of microstructures through QD removal, regulated by surface-to-bulk ratios and solvent interactions [25].

Sequential Ligand Exchange for Polymer:QD Bulk Heterojunctions

This method preserves film morphology while enhancing electronic coupling in polymer-QD blends for photovoltaic applications [26]:

- Initial Solution-Phase Exchange: Synthesize OA-capped PbS QDs following the Hines and Scholes method. Perform first ligand exchange by treating QD solution with butylamine (BA) to replace OA partially.

- Film Deposition: Blend BA-capped PbS QDs with PTB1 polymer in 1:9 weight ratio and deposit via solution casting to form a bulk heterojunction film.

- Solid-State Secondary Exchange: Treat the deposited film with 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) solution to replace remaining long ligands with short thiols.

- Morphological Validation: Use scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and tomographic reconstruction to verify preservation of nanoscale phase separation without void formation. Advantage: This sequential approach prevents the severe morphological changes and void defects observed when directly exchanging OA with MPA in solid films [26].

Sulfide Capping for InSb Quantum Dot Photodiodes

This protocol enhances carrier mobility in III-V QD-based short-wavelength infrared photodiodes [23]:

- QD Synthesis: Synthesize InSb CQDs using oleylamine as solvent and super hydride as reducing agent, with optimized In/Sb precursor ratio and SH concentration to suppress oxidation.

- Size Selection: Perform four-step centrifugation with incremental methanol addition to narrow size distribution, collecting fractions A-D for optimal monodispersity.

- Sulfide Ligand Exchange: Replace native oleylamine ligands with sulfide ions using appropriate sulfur precursors.

- Film Characterization: Confirm reduced interparticle distance (1.5 ± 0.5 nm vs. 5.0 ± 0.5 nm for OLA-capped) through HR-TEM and GI-XRD.

- Device Fabrication: Assemble photodiode architecture with sulfide-capped InSb CQDs as photoactive layer. Measure electrical properties showing low dark current density (~nA cm⁻²) and improved EQE (18.5%) at 0V bias.

Visualization of Ligand Exchange Processes

Diagram 1: Ligand exchange process showing the transition from long insulating ligands to short conducting ligands, resulting in reduced interparticle distance and enhanced carrier mobility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Conventional Ligand Exchange Processes

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Compatible QD Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Ligands | Sulfide salts, Indium chloride (InCl₃), Halide salts (Br⁻, I⁻) | Atomic-scale bridging; Anionic site passivation; Z-type ligand exchange | InSb, InP, PbS, CdSe [23] [27] |

| Short-Chain Thiols | Ethanedithiol (EDT), 3-Mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) | Strong covalent binding to metal sites; Radical-mediated exchange processes | PbS, CdSe, ZnO [25] [26] |