Beyond Insulation: Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies for High-Performance Perovskite Quantum Dots in Biomedicine

The inherent insulating nature of surface ligands on Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) presents a significant bottleneck for their application in sensitive biomedical devices, limiting charge transfer and diagnostic sensitivity.

Beyond Insulation: Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies for High-Performance Perovskite Quantum Dots in Biomedicine

Abstract

The inherent insulating nature of surface ligands on Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) presents a significant bottleneck for their application in sensitive biomedical devices, limiting charge transfer and diagnostic sensitivity. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative surface chemistry strategies designed to overcome this challenge. We explore the foundational principles of PQD instability and ligand dynamics, detail cutting-edge methodological advances in ligand exchange and surface engineering, and offer troubleshooting insights for optimizing film conductivity and stability. Furthermore, we validate these approaches through a comparative review of recent breakthroughs that enhance photoluminescence quantum yield and facilitate femtomolar-level biomarker detection, outlining a clear pathway for integrating high-performance PQDs into next-generation bioimaging and diagnostic platforms.

The Insulating Ligand Problem: Understanding Surface Chemistry and Stability Challenges in PQDs

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Charge Transport in PQD Solar Cells

Problem: Low power conversion efficiency in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) solar cells due to insufficient charge carrier mobility.

Explanation: The dynamically bound pristine long-chain oleate (OA⁻) ligands on the PQD surface are inefficiently substituted during standard ester antisolvent rinsing under ambient conditions. This results in a low density of conductive capping ligands, creating a high tunneling barrier between QDs and leaving extensive surface vacancy defects that trap charge carriers [1].

Solution: Implement an Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy.

- Method: Create an alkaline environment by adding potassium hydroxide (KOH) to methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent for interlayer rinsing of PQD solids [1].

- Mechanism: The alkaline environment renders ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous and lowers the reaction activation energy by approximately 9-fold, facilitating rapid substitution of insulating oleate ligands with conductive hydrolyzed counterparts [1].

- Outcome: This treatment can load up to twice the conventional amount of conductive ligands, leading to fewer trap-states, homogeneous orientations, and minimal particle agglomerations in the light-absorbing layer [1].

Quantum Dot Aggregation During Processing

Problem: QDs aggregate during film deposition or storage, leading to non-uniform films and defective charge transport pathways.

Explanation: The native ligands OA and OAm provide colloidal stability in solution but can desorb or provide insufficient steric hindrance during processing, especially when using polar solvents. This destabilizes the QD surfaces, causing irreversible aggregation [2] [3].

Solution: Employ a mixed-ligand engineering strategy to fine-tune surface energy and steric stabilization.

- Method: Synthesize QDs using different combinations of carboxylic acids and amines. For example, combine branched octanoic acid (OcA) with long-chain oleylamine (OAm) [3].

- Mechanism: The branched nature of OcA and OAm enhances steric stabilization. This combination results in higher surface energy (theoretically up to 2.14 eV for CsPbBr₃ QDs), which reduces particle migration and aggregation during solvent evaporation [3].

- Outcome: Superior dispersibility and optimized inkjet printability, effectively suppressing the "coffee ring effect" and enabling the fabrication of high-quality, uniform QD patterns on flexible substrates [3].

Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and Stability

Problem: Synthesized QDs exhibit low PLQY and degrade under thermal stress, indicating a high density of non-radiative recombination traps.

Explanation: The binding energy of OA/OAm ligands to the QD surface is composition-dependent. Weaker binding fails to effectively passivate surface defects, which act as traps. Furthermore, these ligands can desorb under thermal stress, leading to rapid degradation [4].

Solution: Select A-site cation compositions and ligand systems that maximize ligand binding energy.

- Method: For CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ PQDs, FA-rich QDs with appropriate ligands exhibit stronger ligand binding energy [4].

- Mechanism: Stronger ligand binding ensures robust surface passivation and improves thermal tolerance. The degradation pathway shifts; FA-rich QDs with higher ligand binding energy directly decompose into PbI₂ at higher temperatures, whereas Cs-rich QDs with weaker ligand binding undergo a detrimental phase transition at lower temperatures [4].

- Outcome: Improved PLQY and enhanced thermal stability of the QDs, which is critical for device operation and longevity [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are oleic acid and oleylamine so commonly used in QD synthesis if they hinder charge transport?

A1: OA and OAm are excellent ligands for the colloidal synthesis of QDs. They effectively control nucleation and growth, resulting in monodisperse QDs with high crystallinity and excellent solution stability [5]. Their shortcomings are primarily related to solid-state electronic properties. Therefore, the common strategy is to use OA/OAm for high-quality synthesis and then perform a post-synthetic ligand exchange to replace them with shorter or more conductive ligands for device integration [1] [6].

Q2: Besides shorter ligands, what are alternative ligand strategies to improve charge transport?

A2: Research is exploring "active" ligands that do more than just reduce distance:

- Redox-Active Ligands: Ligands like ferrocene carboxylate introduce electronic states that provide an additional pathway for charge transport via a self-exchange chain reaction, complementing direct hopping between QDs [6].

- Dipole-Modifying Ligands: Ligands such as 4-fluorophenethylammonium iodide (FPEAI) can tune the interfacial energy level alignment at the QD/charge transport layer interface. This increases the interfacial energy gap, which can lead to a higher open-circuit voltage (VOC) in solar cells [7].

Q3: My ligand-exchanged QD film has become insoluble and aggregated. What went wrong?

A3: This is a common challenge. If the new ligands are too short or polar, they can drastically reduce the interparticle repulsion, causing QDs to aggregate and precipitate. The key is to:

- Control Solvent Polarity: Use solvents with appropriate polarity to balance ligand solubility and QD stability.

- Optimize Ligand Concentration: Ensure sufficient ligand coverage to prevent direct QD-QD fusion.

- Consider Sequential Processing: Techniques like liquid-state ligand exchange allow for the creation of stable, concentrated inks with conductive ligands before film deposition [1].

The table below summarizes key experimental data from recent studies on mitigating the charge transport issues caused by native ligands.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Ligand Engineering Strategies for Improved Charge Transport

| Ligand System / Strategy | Material System | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Treatment (KOH+MeBz) | FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs | Solar Cell Certified PCE | 18.30% (highest for hybrid PQDSCs at time of publication) | [1] |

| Mixed Ligand (OcA/OAm) | CsPbBr₃ QDs | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | 92% | [3] |

| Redox Ligand (FcCOO⁻) | ZnO QDs | Charge Transport Mechanism | Enabled long-range transport via self-exchange in addition to QD hopping | [6] |

| Dipole Ligand (FPEAI) | MAPbI₃/C₆₀ | Interfacial Energy Gap | Increased from 1.19 eV (PEAI) to 1.50 eV | [7] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Engineering

| Reagent Category | Example Compounds | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Ligands | Acetate (Ac⁻), Octanoic Acid (OcA), Octylamine (OcAm) | Reduce interparticle distance, lower tunneling barrier for hopping. | May compromise colloidal stability; requires careful solvent selection [1] [3]. |

| Redox-Active Ligands | Ferrocene carboxylate (FcCOO⁻) | Provide active sites for charge transport via self-exchange reactions. | Introduces an alternative charge pathway; kinetics depend on ligand coverage [6]. |

| Dipole-Modifying Ligands | 4-fluorophenethylammonium iodide (FPEAI) | Modulate energy level alignment at interfaces to improve VOC. | Directly impacts interfacial energetics rather than bulk conductivity [7]. |

| Alkaline Additives | Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Catalyze hydrolysis of ester antisolvents to generate conductive ligands in situ. | Must be carefully regulated to avoid damaging the ionic perovskite core [1]. |

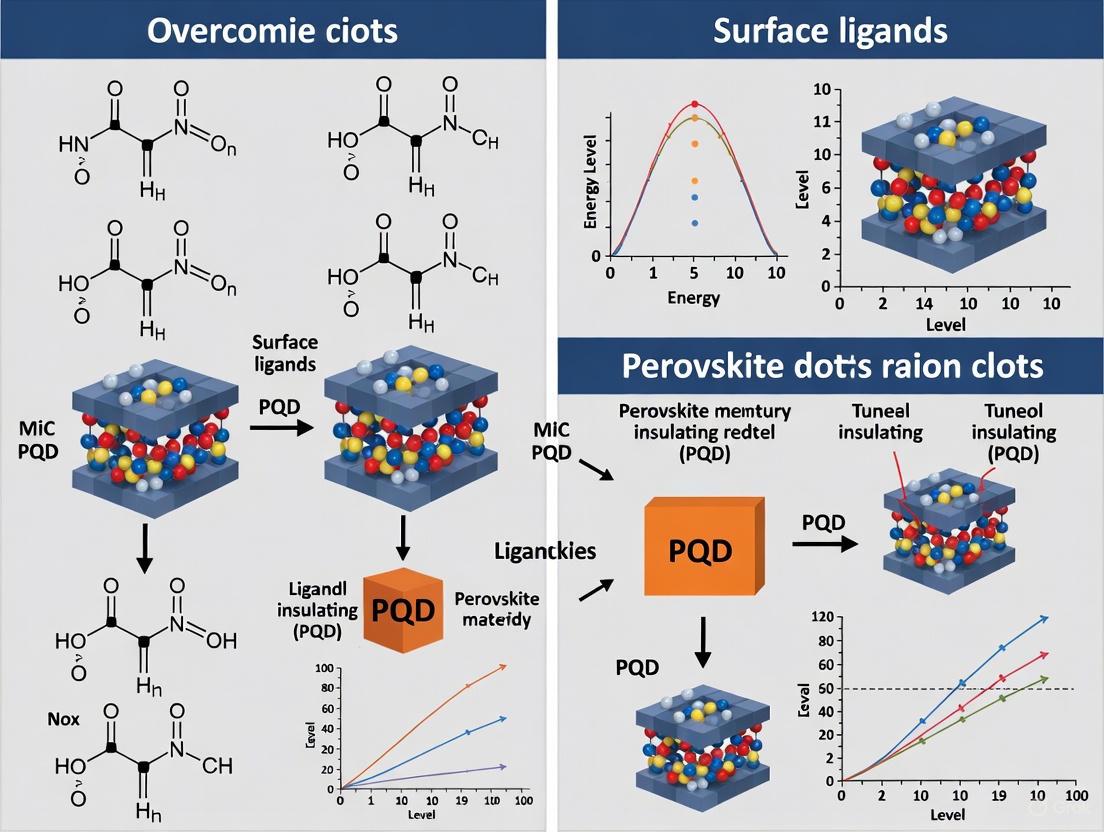

Conceptual Diagrams

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions in PQD Surface Engineering

| Problem Phenomenon | Root Cause | Diagnostic Method | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Surface defects from detached ligands acting as non-radiative recombination centers [8] [9] | Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy, PL lifetime measurements [8] | Implement hybrid passivation with ligands like DDAB combined with inorganic SiO₂ coating [8]. |

| Poor Charge Transport in Films | Insulating nature of long-chain alkyl ligands (e.g., OA, OAm) creating barriers between PQDs [9] [10] | Electrical conductivity measurement, Film morphology analysis (TEM) [10] | Perform solid-state ligand exchange with short-chain conductive ligands (e.g., acetate, benzoate) or conjugated polymers [1] [10]. |

| Rapid Degradation under Ambient Conditions | Ligand detachment during purification/exposure, allowing moisture and oxygen ingress [8] [9] | Long-term stability testing under controlled humidity/temperature [8] | Apply a dense inorganic shell (e.g., SiO₂ from TEOS) to encapsulate and protect surface-passivated PQDs [8]. |

| Phase Instability & Halide Migration | Low formation energy for halide vacancies and surface defects promoting ion migration [9] | Temperature-dependent PL analysis, X-ray Diffraction (XRD) [8] | Employ pseudohalogen ligands or metal doping to strengthen the lattice and suppress ion migration [11]. |

| Low Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) in Solar Cells | Inefficient charge extraction due to surface traps and poor inter-dot coupling [1] | Current-Voltage (J-V) characterization, Trap-density measurement [1] | Use an alkaline-augmented antisolvent hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy with KOH/MeBz to enrich conductive capping [1]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Advanced Stabilization Strategies

| Stabilization Method | Key Reagent/Parameter | Performance Improvement | Stability Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Passivation [8] | DDAB (10 mg) + SiO₂ (from TEOS) | PLQY enhancement; PCE increase from 14.48% to 14.85% in solar cells [8] | Retained >90% initial solar cell efficiency after 8 hours [8] |

| Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) [1] | Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) + KOH | Certified PCE of 18.3% in PQD solar cells [1] | Improved storage and operational stability [1] |

| Conjugated Polymer Ligands [10] | Th-BDT or O-BDT polymers | PCE increased to >15% from a baseline of 12.7% [10] | >85% initial efficiency retained after 850 hours [10] |

| Pseudohalogen Surface Treatment [11] | DDASCN (organic pseudohalide) | Suppressed halide migration, enhanced film conductivity [11] | Improved operational stability of red PeLEDs [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are the native ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) problematic for PQD optoelectronics?

These standard long-chain ligands create two major issues: Insulating Nature and Weak Binding. Their long alkyl chains act as insulating barriers, severely hampering charge transport between PQDs in a film [9] [10]. Furthermore, their "kinked" molecular structure due to cis-configured double bonds leads to low surface packing density, making them dynamically bound and prone to detach during purification or upon exposure to ambient stimuli. This detachment leaves behind unprotected surfaces and defects [8] [9].

Q2: What is the fundamental mechanism behind ion migration and defect formation in PQDs?

The primary mechanism involves two interconnected processes:

- Ligand Dissociation: Weakly bound ligands detach from the PQD surface, creating surface vacancies and defects [9].

- Halide Vacancy Formation: The perovskite lattice has low ion migration energy, particularly for halide ions. This allows halide vacancies to form easily and migrate through the lattice, especially when surface defects are present [9]. These processes are accelerated by external stimuli like heat, light, and moisture, leading to irreversible structural degradation.

Q3: How does ligand exchange with short-chain molecules like acetates or benzoates improve performance?

Short-chain ligands like acetate (Ac⁻) or benzoate hydrolyzed from ester antisolvents (e.g., MeOAc, MeBz) provide a dual advantage. They possess a stronger binding affinity to the PQD surface metal sites (e.g., Pb²⁺), which improves stability. More importantly, their shorter chain length reduces the inter-particle distance in PQD films. This closer packing dramatically enhances electronic coupling and charge transport between adjacent PQDs, which is crucial for efficient solar cells and LEDs [1].

Q4: Our PQD films show good initial photoluminescence but degrade rapidly during device fabrication. What strategies can prevent this?

This is a common issue when subsequent solution-processing steps damage the PQD layer. Strategies include:

- Robust Surface Capping: Use a combination of strong-binding organic ligands (e.g., DDAB, pseudohalides) and a protective inorganic shell (e.g., SiO₂) to create a resilient barrier before further processing [8] [11].

- Cross-linking: Introduce cross-linkable ligands that can be polymerized via light or heat to form a stable, networked layer that resists detachment [9].

- Solid-State Ligand Exchange: Perform ligand exchange on pre-deposited solid films rather than in solution, which offers better morphological control [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Passivation for Enhanced Stability

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of stable Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB/SiO₂ PQDs [8].

Materials:

- Precursor salts: CsBr, BiBr₃

- Solvents: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), anhydrous ethanol

- Ligands: Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm), Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB)

- Inorganic shell precursor: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS)

Methodology:

- PQD Synthesis: Dissolve CsBr and BiBr₃ in DMSO with OA and OAm as initial capping ligands. Use an antisolvent (e.g., ethanol) to precipitate the Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs.

- Organic Passivation: Re-disperse the purified PQDs in a solvent and add DDAB. The DDA⁺ cations have a strong affinity for halide anions, effectively passivating surface defects and enhancing the PLQY [8].

- Inorganic Encapsulation: Add TEOS to the DDAB-treated PQD solution under controlled conditions to hydrolyze and form a dense, amorphous SiO₂ shell around each PQD. This shell provides a robust physical barrier against environmental stimuli [8].

- Characterization: Use Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to confirm core-shell morphology. Monitor optical properties and environmental stability via UV-Vis/PL spectroscopy and long-term PLQY tracking under ambient conditions.

Protocol 2: Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) for Conductive Capping

This protocol describes the process to achieve high ligand surface coverage with conductive short-chain ligands [1].

Materials:

- Ester Antisolvent: Methyl Benzoate (MeBz)

- Alkali Source: Potassium Hydroxide (KOH)

- PQD Solid Films: FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs deposited via layer-by-layer spin-coating.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Add a carefully regulated amount of KOH to the MeBz antisolvent to create an alkaline environment.

- Interlayer Rinsing: After depositing each layer of PQDs, rinse the film with the KOH/MeBz solution. The alkaline environment facilitates the rapid hydrolysis of MeBz into conductive benzoate ligands and makes this reaction thermodynamically spontaneous [1].

- Ligand Exchange: The generated benzoate ligands instantly substitute the pristine, insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands on the PQD surface. This process results in up to twice the conventional amount of conductive capping, passivating defects and enhancing inter-dot charge transport [1].

- Post-Treatment: After achieving the desired film thickness, a final post-treatment with short cationic ligands (e.g., FAI in 2-pentanol) can be applied to exchange the A-site cations for further performance enhancement [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Surface Engineering

| Reagent Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | Organic passivator; strong affinity for halide anions, improves surface coverage and PLQY [8]. | Enhancing environmental stability and optical properties of PQDs. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for inorganic SiO₂ shell; forms a dense, amorphous protective layer [8]. | Encapsulating PQDs to shield against moisture, oxygen, and heat. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester antisolvent; hydrolyzes into conductive benzoate ligands for X-site exchange [1]. | Replacing long-chain OA ligands in film deposition to boost conductivity. |

| Conjugated Polymers (e.g., Th-BDT) | Dual-function ligand; provides defect passivation and enhances charge transport via π-π stacking [10]. | Simultaneously improving film stability and charge carrier mobility. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkali additive; catalyzes ester hydrolysis in antisolvent, enabling rapid ligand exchange [1]. | Used in AAAH strategy to enrich conductive ligand capping on PQDs. |

Visualized Workflows

Surface Degradation and Stabilization in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Experimental Workflow for PQD Film Processing and Passivation

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental issue with native insulating ligands on PQDs? Native long-chain insulating ligands, such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), are essential for stabilizing colloidal PQDs during synthesis. However, their highly dynamic binding nature and long insulating carbon chains create a significant physical barrier between quantum dots. This barrier drastically reduces inter-dot charge carrier mobility and facilitates non-radiative recombination at surface defects, leading to reduced photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) in films and lower device efficiency [13] [14] [15].

What are the primary symptoms of insufficient ligand passivation? Researchers can identify inadequate ligand passivation through several experimental observations:

- Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): A significant drop in PLQY from solution to solid film indicates rampant non-radiative recombination at surface traps [13] [15].

- Poor Charge Transport: Measured as low conductivity in the PQD film, this results in high turn-on voltages in LEDs and reduced fill factor in solar cells [15] [1].

- Short Photoluminescence Lifetime: Time-resolved photoluminescence (TR-PL) shows a short decay time, confirming the presence of unpassivated surface defects that quench excitons [13] [15].

Which ligand engineering strategies can mitigate these issues? Advanced strategies focus on replacing native ligands with shorter or more tightly bound molecules:

- Short Conductive Ligands: Replacing long OA/OAm with short ligands like acetate or formate reduces inter-dot distance, enhancing film conductivity [1].

- Bidentate Ligands: Molecules like formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN) can bind to the PQD surface with two atoms, offering a binding energy several times higher than native ligands, which minimizes ligand desorption and ensures robust passivation [15].

- Multifunctional Treatments: Strategies like bilateral affinity ligands (e.g., Ag-TOP) can simultaneously passivate metal site defects and improve surface halide stability [13].

Quantitative Data: Ligand Engineering Impact on PQD Performance

The following table summarizes performance metrics achieved by different ligand engineering strategies, highlighting the direct correlation between surface treatment and enhanced optoelectronic properties.

| Ligand Engineering Strategy | Performance Metric | Control / Baseline Value | Treated / Improved Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag-TOP (Bilateral Affinity) | PLQY | ~50% | 93.7% | [13] |

| LED External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Not Specified | 9.43% | [13] | |

| LED Luminance | Not Specified | 3820 cd cm⁻² | [13] | |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Binding Energy (Calculated) | OA: -0.22 eV, OAm: -0.18 eV | -0.91 eV | [15] |

| Film Conductivity | Baseline | 8x higher | [15] | |

| NIR-LED EQE | ~11.5% (Control) | ~23% (Champion) | [15] | |

| Alkaline-Augmented Hydrolysis (MeBz+KOH) | Solar Cell Certified PCE | Conventional Ester Rinsing | 18.3% (Champion) | [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange with FASCN

This protocol details the treatment of FAPbI₃ PQDs with Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) to achieve high surface coverage and performance in near-infrared light-emitting diodes (NIR-LEDs), as reported in the research [15].

1. Principle FASCN is a bidentate liquid ligand. Its short carbon chain (length <3) minimizes insulating effects, while its sulfur and nitrogen atoms form a tight, coordinated bond with uncoordinated lead atoms (Pb²⁺) on the PQD surface. This results in full surface coverage, effective defect passivation, and enhanced charge transport.

2. Materials

- PQD Solution: Pre-synthesized FAPbI₃ quantum dots capped with oleic acid (OA) and oleylammonium (OAm+).

- Ligand Solution: Formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN).

- Solvent: Anhydrous toluene or hexane.

- Equipment: Centrifuge, vortex mixer, and nitrogen glovebox.

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Precipitate the pristine FAPbI₃ PQDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) to the crude solution, followed by centrifugation.

- Step 2: Re-disperse the PQD pellet in a small volume of anhydrous toluene to create a concentrated stock solution.

- Step 3: Add the FASCN ligand solution directly to the PQD stock solution. The typical concentration of FASCN should be optimized but is often used in excess to ensure complete exchange.

- Step 4: Vortex the mixture vigorously to ensure homogeneous interaction and let it react for 5-10 minutes.

- Step 5: Precipitate the ligand-exchanged PQDs by adding a non-solvent, then centrifuge to remove the supernatant containing displaced OA/OAm ligands and excess FASCN.

- Step 6: Re-disperse the final, treated PQDs in an appropriate solvent (e.g., octane) for film deposition.

4. Validation

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure the PLQY of the solution and resulting films. A significant increase confirms effective trap passivation [15].

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TR-PL): A prolonged PL lifetime indicates reduced non-radiative recombination pathways [15].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): A shift in the Pb 4f peak to higher binding energy confirms successful coordination of FASCN with the Pb²⁺ on the PQD surface [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential reagents used in advanced ligand engineering for overcoming the insulating nature of surface ligands.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Ligand Engineering |

|---|---|

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | A bidentate liquid ligand that provides tight binding and full surface coverage, dramatically improving conductivity and PLQY [15]. |

| Silver-Trioctylphosphine (Ag-TOP) | A bilateral affinity ligand that passivates surface defects and stabilizes bromide ions, enhancing optical properties and device performance [13]. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) with KOH | An ester antisolvent used in an alkaline environment to facilitate rapid hydrolysis and substitution of insulating ligands with short conductive benzoate ligands [1]. |

| Di-dodecyl dimethyl ammonium bromide (DDAB) | A common short halide alkyl ligand used in early ligand exchange processes to diminish the insulating effect from long-chain ligands [13]. |

Logic of Ligand Engineering for Enhanced Optoelectronic Properties

The diagram below illustrates the cause-effect relationships and strategic interventions in ligand engineering.

Workflow for Developing a Ligand-Engineered PQD Film

This workflow outlines the key steps and decision points for preparing a high-quality PQD film via ligand exchange.

Technical FAQ: Addressing Core Challenges

FAQ 1: Why do my perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films have poor electrical conductivity even after solid-state ligand exchange?

The poor conductivity often stems from a fundamental trade-off. Long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid/OA and oleylamine/OAm) are essential for colloidal stability and preventing aggregation during synthesis [16] [17]. However, their insulating nature creates a barrier that blocks efficient charge transport between individual QDs in a film [17]. While ligand exchange processes replace these long-chain ligands with shorter ones to improve charge mobility, this process can be inefficient. Incomplete exchange leaves residual insulating ligands, and the process itself can create new surface defects that trap charges, degrading both performance and environmental resilience [18].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the stability of my PQD films against moisture without compromising their luminescence?

The key is targeted surface passivation that does not inhibit charge transport. Strategies include:

- Ligand Engineering: Exchanging dynamically bound, insulating ligands (OA/OAm) with shorter, conjugated ligands or multidentate ligands that bind more strongly to the PQD surface [12] [16] [17]. For example, using conjugated ligands like 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-amine (PPA) provides a pathway for electron cloud overlapping, enhancing conductivity while maintaining stability [17].

- Structural Integration: Incorporating dimensionally engineered organic semiconductors, such as 3D star-shaped molecules, can form a robust, hydrophobic barrier around the PQDs. This passivates surface defects and physically prevents moisture ingress, thereby enhancing environmental resilience without sacrificing, and sometimes even improving, photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [18].

FAQ 3: My PQD solution aggregates during purification. How can I prevent this?

Aggregation during purification is typically caused by the detachment of surface ligands. A modified synthesis protocol like the Split-Ligand Mediated Re-Precipitation (Split-LMRP) method can significantly enhance colloidal stability [19]. This technique involves separately dissolving rich oleic acid (OA) and amine ligands. OA acts both as a stabilizer and to control the polarity of the nucleation environment, allowing for a more stable precipitation and purification process. This method enables purification under ambient conditions and helps maintain colloidal integrity by preventing excessive ligand loss [19].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Setbacks

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for PQD Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low PLQY in films | High surface defect density from inefficient ligand exchange or ligand loss [16]. | Implement post-synthesis passivation with strongly-binding ligands (e.g., thiols like AET) [16] or incorporate a passivating organic semiconductor [18]. | Heals surface traps (vacancies) that cause non-radiative recombination, directly linking colloidal integrity to optoelectronic performance. |

| Poor film conductivity | Insulating barrier from long-chain ligands (OA/OAm) [17]. | Perform ligand exchange with conjugated short-chain ligands (e.g., PPA) [17] or short-chain ionic ligands (e.g., acetate) [18]. | Reduces inter-dot distance and enables electron wavefunction delocalization, boosting charge mobility while trying to retain stability. |

| Rapid degradation in ambient | Surface defects act as entry points for moisture and oxygen; weak ligand binding [16] [18]. | Apply cross-linking ligands or embed PQDs in a stabilizing matrix (e.g., a 3D star-shaped molecule like Star-TrCN) [16] [18]. | Creates a physical hydrophobic barrier and strengthens the surface ligand shell, enhancing environmental resilience. |

| Phase instability (CsPbI₃) | Transformation from photoactive cubic (α) to non-photoactive orthorhombic (δ) phase [18]. | Use surface engineering to induce strain or passivate surface vacancies that trigger phase transition [18]. | Surface ligands and passivators stabilize the high-energy cubic phase at the nanoscale. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ligand Exchange with Conjugated Molecules for Enhanced Charge Transport [17]

This protocol outlines the exchange of native insulating ligands with conjugated 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-amine (PPA) to improve charge mobility.

- Step 1 – Synthesis: Synthesize MAPbBr₃ QDs using standard hot-injection or LARP methods with OA and OAm as initial capping ligands.

- Step 2 – Ligand Exchange: Add a controlled molar excess of PPA ligand directly to the purified PQD solution. Stir the mixture for a specific duration (e.g., 1-2 hours) to allow the dynamic binding equilibrium to favor the new, conjugated ligand.

- Step 3 – Purification: Precipitate the PPA-capped QDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate or toluene/acetonitrile mixture). Recover the QDs via centrifugation and re-disperse them in an appropriate solvent for film fabrication.

- Key Validation: The success of the exchange can be confirmed through Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) showing the new binding modes, and a significant increase in the conductivity and carrier mobility of the resultant film, as measured by space-charge-limited current (SCLC) analysis [17].

Protocol 2: Enhancing Stability via Hybrid PQD-Organic Semiconductor Films [18]

This protocol describes the incorporation of a 3D star-shaped organic semiconductor (Star-TrCN) to improve both stability and device performance.

- Step 1 – PQD Synthesis: Prepare a solution of CsPbI₃ PQDs using the standard hot-injection method, followed by purification to remove excess precursors and ligands.

- Step 2 – Hybrid Solution Preparation: Dissolve the synthesized Star-TrCN molecule in a solvent compatible with the PQD solution (e.g., chlorobenzene). Blend this solution with the purified PQD dispersion at an optimized ratio.

- Step 3 – Film Fabrication: Spin-coat the hybrid Star-TrCN:PQD solution onto the target substrate (e.g., an electron transport layer). Anneal at a mild temperature (e.g., 70-90°C) to remove residual solvent.

- Key Validation: The robust chemical interaction between Star-TrCN and the PQD surface can be demonstrated by theoretical modeling (DFT) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). The enhanced cubic-phase stability is confirmed by X-ray Diffraction (XRD) tracking over time under ambient humidity (20-30% RH) [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for PQD Surface Engineering

| Reagent Name | Function / Role | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands for colloidal synthesis; control nucleation and growth [19] [18]. | Provide initial colloidal integrity but are insulating and dynamically bound, creating a trilemma with mobility and stability [16]. |

| 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-amine (PPA) | Conjugated short-chain ligand for ligand exchange [17]. | Improves charge mobility via electron delocalization while maintaining solubility/stability. Addresses the insulating ligand problem directly. |

| 2-aminoethanethiol (AET) | Short-chain, bidentate ligand for post-synthesis defect passivation [16]. | Strong Pb-S binding heals surface defects, improving PLQY and environmental resilience against water and UV light. |

| Star-TrCN | 3D star-shaped organic semiconductor for hybrid films [18]. | Passivates surface defects, provides a hydrophobic barrier for environmental resilience, and creates a cascade energy band for improved charge extraction. |

| Sodium Acetate (NaOAc) | Short-chain ionic ligand for solid-state ligand exchange [18]. | Replaces long-chain ligands to enhance inter-dot coupling and charge mobility in films. Risk of introducing defects if not optimized. |

Visualizing Strategies and Workflows

The Stability Trilemma in PQDs

Diagram 1: The PQD Stability Trilemma and Solutions Map

Surface Ligand Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Surface Ligand Engineering Pathways

Engineering Conductive Surfaces: Cutting-Edge Ligand Exchange and Functionalization Techniques

Workflow Diagram

Sequential Multiligand Exchange Process

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Ligand Exchange Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Verification Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Poor ligand exchange efficiency | Insufficient antisolvent polarity; inadequate rinsing time; low humidity for ester hydrolysis | Use MeOAc or MeBz antisolvents; optimize rinsing duration (typically 30-60s); consider alkaline-augmented hydrolysis [1] |

| PQD degradation during purification | Excessive antisolvent polarity; harsh mechanical forces; ligand detachment creating defects | Use moderate polarity esters (MeOAc, MeBz); minimize centrifugation force/time; employ low steric hindrance ligands (e.g., OTAI) to reduce detachment [20] |

| Low thin-film conductivity | Residual long-chain ligands; large inter-dot spacing; incomplete surface passivation | Implement sequential multiligand exchange with MPA/FAI; confirm ~85% ligand removal via 1H NMR; use short-chain conductive ligands [21] [22] |

| Phase instability | Surface defects from ligand loss; incomplete coordination of Pb²⁺ ions | Ensure proper passivation with hybrid MPA/FAI ligands; create rich halogen environment with OTAI; reduce surface defects [20] |

| Film cracking or poor morphology | Rapid antisolvent evaporation; excessive ligand removal causing aggregation | Control rinsing and drying conditions; optimize antisolvent volume (e.g., 1-5 mL MeOAc); achieve dense packing without cracks [22] |

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Table 2: Performance Enhancement Techniques

| Technique | Implementation | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) | Add KOH to methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent [1] | ~2x increase in conductive ligands; higher PCE (certified 18.3%); improved stability |

| Low Steric Hindrance (LSH) Ligands | Use octylammonium iodide (OTAI) instead of oleylamine [20] | 73% higher PLQY after purification; reduced ligand detachment; better device performance |

| Hybrid Anionic/Cationic Exchange | Sequential treatment with MPA (anionic) then FAI (cationic) [21] [22] | 28% PCE improvement; reduced hysteresis; enhanced JSC by ~2 mA cm⁻² |

| Controlled Equilibration Kinetics | Overnight equilibration after simultaneous DFe/SA addition [23] | Improved reproducibility (50% duplicates within 10% RSD); better ligand quantification |

Experimental Protocols

Core Methodology: Sequential Solid-State Multiligand Exchange

Synthesis of FAPbI3 Colloidal Quantum Dots

- Prepare PbI₂ solution: Dissolve 0.1 mmol PbI₂ in 2 mL anhydrous ACN with 200 μL OA and 20 μL OctAm

- Prepare FAI solution: Mix 0.08 mmol FAI with 40 μL OA, 6 μL OctAm, and 0.5 mL ACN

- Add FAI solution dropwise to PbI₂ solution with continuous stirring

- Inject mixture into preheated toluene (10 mL, 70°C) under rapid stirring

- Quench immediately in ice/water bath

- Collect precipitate via ultracentrifugation at 9000 rpm for 15 minutes

- Redisperse in hexane (1 mL) and centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove aggregates [22]

Liquid Purification Process

- Add methyl acetate (MeOAc) to colloidal solution in varying volumes (1, 3, or 5 mL)

- Centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 15 minutes

- Discard supernatant containing residual precursors and free ligands

- Redisperse sediment in chloroform (1 mL)

- Centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove large particles

- Confirm ~85% ligand removal via 1H NMR spectroscopy [22]

Sequential Solid-State Multiligand Exchange

- Prepare exchange solution: 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) in MeOAc

- Apply exchange solution to spin-coated PQD films

- Execute sequential exchange: First replace long-chain OctAm and OA with short-chain MPA

- Follow with FAI passivation to complete the multiligand exchange

- Characterize via 1H NMR to confirm surface passivation with MPA and FAI [21] [22]

Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis Protocol

Enhanced Ester Hydrolysis for Improved Ligand Exchange

- Select methyl benzoate (MeBz) as antisolvent for its suitable polarity

- Establish alkaline environment with potassium hydroxide (KOH)

- Add KOH to MeBz antisolvent for interlayer rinsing of PQD solids

- Utilize alkaline conditions to render ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous

- Achieve approximately 9-fold reduction in reaction activation energy

- Substitute pristine insulating oleate ligands with hydrolyzed conductive counterparts

- Obtain up to double the conventional amount of conductive ligands [1]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Sequential Multiligand Exchange

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Precursors | Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.9%); Formamidinium iodide (FAI, 99.9%) | Core PQD synthesis; ensures high purity and optimal crystal formation [22] |

| Long-Chain Ligands | Oleic acid (OA); Octylamine (OctAm) | Initial surface stabilization during synthesis; provide colloidal stability but limit conductivity [21] [22] |

| Short-Chain Exchange Ligands | 3-Mercaptopropionic acid (MPA); Formamidinium iodide (FAI) | Replace long-chain insulators; improve inter-dot charge transport; MPA binds as X-type ligand [21] [22] |

| Solvents & Antisolvents | Methyl acetate (MeOAc); Methyl benzoate (MeBz); Toluene; Acetonitrile (ACN) | MeOAc/MeBz facilitate ligand exchange and purification; ACN and toluene for synthesis [22] [1] |

| Alkaline Enhancers | Potassium hydroxide (KOH) | Accelerates ester hydrolysis in AAAH strategy; enables spontaneous ligand substitution [1] |

| Device Fabrication | SnO₂ colloidal precursor; Spiro-OMeTAD; Li-TFSI; 4-tert-butylpyridine (TBP) | Electron and hole transport layers for complete solar cell devices [22] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Methodology Optimization

Q: What is the optimal MeOAc volume for liquid purification, and how does it affect ligand removal? A: The research tested 1, 3, and 5 mL MeOAc volumes (labeled LP1, LP3, LP5). While all volumes achieved approximately 85% ligand removal confirmed by 1H NMR, intermediate volumes (3 mL) typically provide the best balance between effective ligand removal and preservation of PQD structural integrity. Excessive antisolvent may cause unnecessary ligand detachment leading to surface defects [22].

Q: Why use a sequential approach rather than simultaneous multiligand exchange? A: Sequential exchange allows controlled replacement of different ligand types. The demonstrated process first addresses the anionic ligands (replacing OA with MPA) followed by cationic ligands (replacing OctAm with FAI). This stepwise approach prevents uncontrolled ligand stripping and ensures proper surface passivation at each step, reducing defect formation and improving final film quality [21] [22].

Q: How does the alkaline treatment enhance ester hydrolysis for ligand exchange? A: The alkaline environment (achieved with KOH) addresses both thermodynamic and kinetic limitations. Theoretically, it renders ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous and lowers the reaction activation energy by approximately 9-fold. Practically, this enables rapid substitution of pristine insulating oleate ligands with up to twice the conventional amount of hydrolyzed conductive counterparts during interlayer rinsing [1].

Problem Resolution

Q: How can I prevent PQD aggregation during the purification process? A: Employ low steric hindrance ligands like those provided by octylammonium iodide (OTAI). These short-chain ligands (8 carbon atoms) have a smaller "force-receiving area" compared to conventional oleylamine (18 carbon atoms), making them less likely to desorb during purification. This approach maintained a 73% higher photoluminescence quantum yield after purification compared to control QDs [20].

Q: What characterization methods confirm successful ligand exchange? A: 1H NMR spectroscopy is the primary technique for quantifying ligand removal (~85%) and confirming surface passivation with new ligands. Additional verification methods include: photoluminescence spectroscopy (to assess defect reduction), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (to measure improved conductivity), UV-Vis spectroscopy, and TEM for morphological analysis [21] [22].

Q: How can I improve reproducibility in ligand exchange experiments? A: The competitive ligand exchange approach used in metallurgical studies demonstrates that overnight equilibration after simultaneous addition of competing ligands improves reproducibility, with 50% of duplicate analyses agreeing within 10% relative standard deviation. Controlling equilibration kinetics and using standardized quantification methods like ProMCC software also enhance reproducibility [23].

Performance & Applications

Q: What performance improvements can I expect from successful multiligand exchange? A: The sequential multiligand exchange with MPA/FAI delivers approximately 28% improvement in power conversion efficiency, enhanced current density by ~2 mA cm⁻², reduced hysteresis, and improved operational stability. These improvements stem from reduced inter-dot spacing, enhanced thin-film conductivity, and minimized vacancy-assisted ion migration [21] [22].

Q: Is this approach applicable to other perovskite compositions beyond FAPbI₃? A: Yes, the alkaline treatment strategy has demonstrated broad compatibility with diverse PQD compositions, including CsPbI₃ and mixed-cation systems like FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃. The fundamental principles of replacing long-chain insulating ligands with short-chain conductors apply across different perovskite quantum dot systems [1].

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) hold great promise for next-generation photovoltaics due to their tunable bandgap, high light absorption coefficients, and defect tolerance [1]. However, their surfaces are typically capped with long-chain insulating ligands like oleate (OA⁻) and oleylammonium (OAm⁺), which severely impede charge transfer between adjacent QDs, compromising the performance of solar cells [14]. The Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy is a transformative thermodynamic approach designed to overcome this fundamental limitation. By creating an alkaline environment, this method facilitates the rapid and extensive substitution of insulating ligands with dense, conductive capping, leading to record-breaking photovoltaic efficiency [1] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details the key materials and their functions for implementing the AAAH strategy.

| Reagent/Material | Function in AAAH Strategy |

|---|---|

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Preferred antisolvent of moderate polarity; its hydrolyzed product (benzoate) provides robust binding to the PQD surface for superior charge transfer [1]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkaline source that creates the necessary environment to render ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous and lower the reaction activation energy [1]. |

| FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs | Representative hybrid A-site lead iodide perovskite quantum dots used as the light-absorbing material [1]. |

| Oleate (OA⁻)/Oleylammonium (OAm⁺) | Pristine long-chain insulating ligands that are replaced during the AAAH process [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the AAAH Strategy

This section provides a detailed methodology for applying the AAAH strategy to fabricate PQD solar cell light-absorbing layers.

1. PQD Solid Film Deposition:

- Begin by spin-coating a layer of synthesized hybrid FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs (capped with pristine OA⁻ and OAm⁺ ligands) onto your substrate to form an "as-cast" solid film [1].

2. Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Rinsing:

- Prepare the antisolvent solution by coupling methyl benzoate (MeBz) with a carefully regulated concentration of potassium hydroxide (KOH). The KOH establishes the critical alkaline environment [1].

- Rinse the as-cast PQD solid film with the KOH/MeBz solution under ambient conditions (approximately 30% relative humidity). This step initiates the hydrolysis of the ester antisolvent, generating short-chain conductive ligands in situ which rapidly substitute the insulating OA⁻ ligands [1].

3. Layer-by-Layer Assembly:

- Repeat the deposition and alkaline antisolvent rinsing steps in a layer-by-layer fashion until the desired film thickness is achieved. Each rinsing step ensures the removal of pristine ligands and the establishment of a conductive capping on the newly deposited layer [1].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: During the antisolvent rinsing step, my PQD film completely dissolves or degrades. What is the likely cause?

- A: This is often caused by using an antisolvent with excessive polarity. Esters like methyl formate (MeFo) or ethyl formate (EtFo), or sulfonate-based esters, are too aggressive and disrupt the ionic perovskite core [1].

- Solution: Use an antisolvent with moderate polarity, such as methyl benzoate (MeBz) or methyl acetate (MeOAc), which effectively remove ligands without attacking the perovskite structure [1].

Q2: My final device efficiency is low, and characterization suggests poor charge transport. Has the ligand exchange been ineffective?

- A: This is the core problem AAAH is designed to solve. Conventional neat ester rinsing often only removes pristine OA⁻ ligands without sufficiently replacing them, creating surface vacancy defects that trap charge carriers [1].

- Solution:

- Verify Alkaline Environment: Ensure the KOH is properly dissolved and mixed in the MeBz antisolvent to create the essential alkaline conditions.

- Confirm Humidity: The hydrolysis reaction requires ambient moisture. Perform the rinsing step at a relative humidity of around 30% [1].

- Characterize the Output: A successful AAAH treatment should result in a film with fewer trap-states, homogeneous crystallographic orientations, and minimal particle agglomerations, leading to a certified efficiency approaching 18.3% [1] [24].

Q3: Why is methyl benzoate (MeBz) the preferred antisolvent in this protocol over the more common methyl acetate (MeOAc)?

- A: The hydrolyzed product of MeBz (benzoate) offers superior binding to the PQD surface compared to the acetate from MeOAc. This robust binding provides a more durable conductive capping, which enhances charge transfer and overall device stability [1].

Q4: The AAAH process seems to focus on anionic (X-site) ligand exchange. How are the cationic (A-site) ligands managed?

- A: The AAAH strategy specifically targets the exchange of pristine anionic OA⁻ ligands on the X-site. A subsequent post-treatment step is typically required to substitute the pristine OAm⁺ ligands on the A-site. This is often done using protic solvents like 2-pentanol (2-PeOH) as the medium for cationic salt solutions (e.g., FAI, CsOAc) to mediate efficient A-site ligand exchange [1].

AAAH Workflow and Ligand Exchange Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow and the chemical process of the AAAH strategy.

The implementation of the AAAH strategy leads to a significant leap in device performance, as summarized below.

| Performance Metric | Value Achieved with AAAH | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 18.30% [1] [24] | Highest certified efficiency reported for perovskite quantum dot solar cells. |

| Best Lab PCE | 18.37% [1] | Champion device efficiency measured in the laboratory. |

| Steady-State Efficiency | 17.85% [1] [24] | Stabilized power output under continuous illumination. |

| Average PCE (over 20 devices) | 17.68% [1] | Demonstrates high reproducibility of the method. |

| Large-Area (1 cm²) Champion PCE | 15.60% [24] | Highlights the promising scalability of the AAAH strategy. |

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) are at the forefront of next-generation optoelectronic materials due to their excellent properties, including tunable bandgaps and high photoluminescence quantum yields. However, their performance is inherently limited by the insulating nature of the long-chain organic ligands (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine) used in their synthesis. These ligands create charge transport barriers in quantum dot films, severely hindering the efficiency of devices like solar cells and light-emitting diodes (QLEDs). This technical support center is dedicated to overcoming this challenge through the application of advanced short-chain ligands, providing researchers with practical troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to integrate these solutions into their experimental workflows.

Core Ligand Profiles and Quantitative Performance

The following table summarizes the key short-chain ligands, their distinct roles in mitigating the insulating ligand problem, and their documented impact on device performance.

| Ligand Name | Chemical Profile | Primary Function & Mechanism | Key Performance Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercaptopropionic Acid (3-MPA) [25] [26] | Bifunctional organosulfur compound (HSCH₂CH₂CO₂H) with thiol (-SH) and carboxylic acid (-COOH) groups. | Surface Anchor & Passivation: Thiol group binds strongly to PQD surface (via Pb-S bonds); carboxylic acid can passivate surface defects or facilitate further functionalization. | Enhanced stability of QD dispersions; used in sensor applications for selective ion detection (e.g., Cr(III)) [26]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) [27] | CH(NH₂)₂⁺ I⁻ - A cationic component for the perovskite "A-site". |

Perovskite Stabilizer & Bandgap Tuner: Stabilizes the photoactive black phase (α-FAPbI₃) and achieves a narrower, more ideal bandgap (~1.48 eV) than MAPbI₃. | Certified PSC efficiencies now exceed 25% [27]. Improved thermal stability and charge-carrier mobility compared to MA-based counterparts [27]. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) Derivatives [1] | Ester compound that hydrolyzes into benzoate ligands. | Conductive Capping Agent: Serves as an antisolvent that hydrolyzes to replace insulating oleate ligands with short, conductive benzoate ligands, enhancing inter-dot charge transfer. | A certified quantum dot solar cell (QDSC) efficiency of 18.3% [1]. Improved film quality with fewer traps and minimal agglomeration [1]. |

| Conjugated Ligands (e.g., PPABr) [28] | Short-chain amines with conjugated backbones (e.g., 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-amine bromide). | Carrier Transport Booster: The delocalized π-electron system and π-π stacking between ligands create efficient pathways for charge transport across the QD film. | QLEDs achieved an External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) of 18.67%, which could be further elevated to 23.88% with advanced light extraction structures [28]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why are my PQD films still highly resistive after ligand exchange with short-chain molecules?

Potential Cause: Incomplete ligand exchange or re-adsorption of insulating ligands.

- Solution: Implement a competitive rinsing strategy. When using methyl benzoate antisolvent, create an alkaline environment (e.g., with KOH) to facilitate rapid and spontaneous hydrolysis of the ester. This "Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis" (AAAH) strategy can double the amount of conductive ligands capping the PQD surface compared to using neat ester antisolvents [1].

- Prevention: Ensure your antisolvent is free of contaminants and has suitable polarity. MeBz and MeOAc are preferred due to their moderate polarity, which prevents perovskite core degradation while effectively removing OA [1].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the charge transport in my QLED devices without sacrificing photoluminescence?

Potential Cause: Imbalanced carrier injection and transport within the device.

- Solution: Utilize functionalized short-chain conjugated ligands like 4-CH3 PPABr. The delocalized electron cloud along the conjugated backbone enhances carrier mobility through π-π stacking, while the short chain length reduces insulating effects. This approach can significantly boost device efficiency with only a minimal change in PLQY [28].

- Experimental Tip: To tailor transport, select conjugated ligands with specific substituents. Electron-donating groups (e.g., -CH₃) can enhance hole transport, while electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -F) can improve electron transport [28].

FAQ 3: My FAPbI3 films are converting to the non-perovskite yellow phase. How can I stabilize the black phase?

Potential Cause: The photoactive black α-FAPbI3 phase is metastable at room temperature.

- Solution A (Compositional Engineering): Introduce a small percentage of cesium (Cs⁺) or methylammonium (MA⁺) cations into the A-site to form a mixed-cation perovskite (e.g., FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃), which entropically stabilizes the black phase [1] [27].

- Solution B (Nanoconfinement): Leverage quantum dot structures. The high surface energy and strain in nanoscale crystals can inherently stabilize the α-FAPbI3 phase. Ensure your synthesis yields monodisperse PQDs with sizes around or below the exciton Bohr radius [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol describes the interlayer rinsing of PQD solid films to replace pristine insulating oleate ligands with conductive benzoate ligands.

- Objective: To achieve a dense, conductive capping on PQD surfaces, leading to enhanced charge transport in the assembled film.

- Materials:

- PQD solid film (e.g., FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃) deposited on a substrate.

- Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent.

- Potassium Hydroxide (KOH).

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare Alkaline Antisolvent: Add a carefully regulated amount of KOH to the methyl benzoate antisolvent. The alkalinity must be optimized to promote hydrolysis without damaging the PQDs.

- Rinse PQD Film: Immediately after spin-coating a layer of PQDs, pipette the alkaline methyl benzoate antisolvent onto the film surface. Ensure complete and uniform coverage.

- Incubate and React: Allow the antisolvent to sit on the film for a short, controlled time (typically 20-40 seconds). During this time, the alkaline environment facilitates the hydrolysis of MeBz, generating benzoate ions that substitute the pristine oleate ligands.

- Spin-dry: Spin the substrate at high speed to remove the antisolvent and any displaced ligand residues.

- Repeat: Repeat the spin-coating and rinsing steps for each subsequent layer in the layer-by-layer deposition until the desired film thickness is achieved.

- Troubleshooting Notes:

- Film Dissolution: If the film dissolves, the antisolvent polarity is too high, or the rinsing time is too long. Confirm the use of esters with moderate polarity like MeBz [1].

- Ineffective Exchange: If conductivity does not improve, the KOH concentration may be too low, or the ambient humidity might be insufficient to drive hydrolysis. The AAAH strategy is designed to overcome these kinetic and thermodynamic barriers [1].

This protocol outlines the post-treatment of synthesized CsPbBr₃ QDs to exchange long-chain ligands with short conjugated amines for improved carrier transport in QLEDs.

- Objective: To enhance the carrier mobility of the QD film by introducing conjugated ligands that facilitate charge transport via π-π stacking.

- Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbBr₃ QDs in non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane or toluene).

- Conjugated ligand solution (e.g., 4-CH3 PPABr or 4-F PPABr) in a polar solvent (e.g., 2-PeOH).

- Centrifuge and tubes.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precipitate QDs: Add a polar antisolvent (like ethanol or acetone) to the QD solution and centrifuge to precipitate the QDs. Discard the supernatant containing excess original ligands.

- Redisperse and Mix: Redisperse the QD pellet in a small volume of non-polar solvent. In a separate tube, prepare a solution of the conjugated ligand (e.g., 5 mg in 1 mL of 2-pentanol).

- Initiate Ligand Exchange: Combine the QD solution with the conjugated ligand solution. Vortex or stir the mixture for a period (e.g., 1-2 minutes) to allow the dynamic exchange of OAm⁺ with the short-chain conjugated ammonium cation.

- Purify: Add a non-solvent to trigger precipitation of the ligand-exchanged QDs. Centrifuge and discard the supernatant.

- Final Dispersion: Redisperse the final QD pellet in an appropriate solvent for film deposition (e.g., octane for spin-coating).

- Troubleshooting Notes:

- Aggregation: If the QDs aggregate heavily after exchange, the ligand concentration may be too low, or the purification may be too harsh. The conjugated ligands with rigid backbones can help maintain colloidal stability [28].

- PLQY Drop: A slight drop is possible, but a significant decrease indicates overly aggressive exchange or surface degradation. Optimize the ligand concentration and reaction time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Hydrolyzable Antisolvent: A key ester-based antisolvent for interlayer rinsing. Hydrolyzes to form benzoate ions, which replace insulating oleate ligands on the PQD surface, boosting conductivity [1]. | [1] |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkalinity Catalyst: Used to create an alkaline environment during antisolvent rinsing, which dramatically enhances the hydrolysis rate and spontaneity of esters like methyl benzoate [1]. | [1] |

| 3-Phenyl-2-propen-1-amine Bromide (PPABr) | Conjugated Short Ligand: A short-chain, conjugated ligand. Its delocalized π-system enhances carrier transport between QDs via π-π stacking, directly addressing the insulating ligand problem in QLEDs [28]. | [28] |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Narrow-Bandgap A-Site Cation: The cationic precursor for forming FAPbI₃, which has a more ideal bandgap (~1.48 eV) and better thermal stability than MAPbI₃, making it superior for high-efficiency solar cells [27]. | [27] |

| Cesium Lead Halide (CsPbX₃) QDs | Base PQD Material: The foundational, all-inorganic PQD system. Serves as a stable platform for subsequent A-site cation exchange (e.g., with FAI) to create hybrid PQDs with tailored properties [1] [28]. | [1] [28] |

Process Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: Conductive Capping Process

Diagram Title: Conductive Capping via Alkali-Augmented Ligand Exchange

Diagram 2: Charge Transport Enhancement

Diagram Title: Charge Transport Enhancement via Conjugated Ligands

In the development of biomedical-grade perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), surface ligands are indispensable for stabilizing the nanocrystal core and determining its biological interactions. However, the long-chain, insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine) used in standard PQD synthesis present a significant challenge. While they ensure colloidal stability, their insulating nature severely impedes charge transfer and functional performance, which is critical for applications like biosensing and bioimaging. Furthermore, their dynamic binding character leads to easy detachment, causing nanoparticle aggregation and potential toxicity, thereby hindering clinical translation. Ligand engineering—the strategic modification of these surface molecules—is thus essential to overcome these limitations. This technical support center outlines the core protocols for in-situ and post-synthesis ligand engineering, providing researchers with clear guidelines to navigate this complex landscape.

Core Concepts: Ligand Engineering Pathways

Ligand engineering strategies can be fundamentally categorized into two approaches, each with distinct advantages and challenges.

- In-situ Ligand Engineering: This approach involves introducing functional ligands directly during the synthesis of the PQDs. The ligands become incorporated as the nanocrystal forms.

- Post-Synthesis Ligand Engineering: This approach involves modifying the ligand shell after the PQDs have been synthesized and purified. This typically occurs through a ligand exchange process, where original insulating ligands are replaced with more desirable ones.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and implementing these strategies.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing the two main ligand engineering pathways.

Detailed Protocol: In-situ Ligand Engineering

The in-situ approach focuses on incorporating improved ligands directly during the hot-injection or ligand-assisted re-precipitation (LARP) synthesis of PQDs [14]. This method aims to produce PQDs with a more stable and inherently functional surface.

Key Workflow for In-Situ Ligand Engineering:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Precursor and Ligand Preparation:

- Prepare standard perovskite precursors (e.g., lead iodide and cesium carbonate) in suitable solvents.

- Select and add alternative ligands to the precursor mixtures. Common choices include:

Synthesis Execution:

- Proceed with the standard hot-injection or LARP method. The functional ligands will compete with and partially replace the standard OA/OAm molecules during crystal growth, becoming directly incorporated into the evolving ligand shell.

Purification and Isolation:

- Upon synthesis completion, purify the PQDs using anti-solvents like methyl acetate or butanol to remove excess reactants and unbound ligands [9].

- Isolate the PQDs via centrifugation and re-disperse them in an appropriate solvent for storage or further use.

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: The PQDs precipitate immediately after synthesis. What went wrong?

- A: This indicates poor colloidal stability. The new ligands may not be providing sufficient steric hindrance. Ensure the ligands have appropriate anchoring groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂, -SH) and consider adjusting the ligand-to-precursor ratio to optimize surface coverage.

Detailed Protocol: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange

Post-synthesis ligand exchange is a powerful and widely used strategy to replace the native long-chain insulating ligands with shorter, conductive, or more biocompatible ones after the PQDs have been synthesized [14].

Key Workflow for Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

PQD and Exchange Solution Preparation:

- Synthesize and purify standard OA/OAm-capped PQDs (e.g., CsPbI₃) to create a clean starting material.

- Prepare the ligand exchange solution. This typically involves dissolving the new, short-chain ligands in a solvent. A key advanced method is the Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis (AAAH) [1]:

- Ligand Source: Use an ester like methyl benzoate (MeBz) as the antisolvent.

- Alkaline Environment: Add a mild base like potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the MeBz. This facilitates the rapid hydrolysis of the ester into conductive benzoate ligands, making the substitution of pristine OA ligands thermodynamically spontaneous.

Ligand Exchange Reaction:

- For solid-state film exchange, rinse the spin-coated PQD film with the prepared exchange solution (e.g., MeBz with KOH).

- For solution-phase exchange, incubate the PQD dispersion with the exchange solution for a designated time, often with stirring.

Purification:

- After exchange, purify the PQDs to remove the displaced OA/OAm ligands and reaction by-products. This often involves repeated precipitation and centrifugation steps.

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: The PQDs lose their luminescence or degrade during the exchange process. Why?

- A: This is often due to the polar solvent damaging the ionic perovskite core [14]. The use of ester-based antisolvents like methyl benzoate, which have neither protonicity nor nucleophilicity, can help preserve the PQD structure [1]. Always ensure the solvent and reaction conditions are mild enough to maintain PQD integrity.

- Q: The ligand exchange seems incomplete, and device performance is poor.

- A: Incomplete exchange is common with neat ester antisolvents. The AAAH strategy, which uses an alkaline environment to boost hydrolysis and ligand substitution, can achieve a near 2-fold increase in the amount of conductive ligands capping the PQD surface, leading to significantly improved charge transport [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents used in the ligand engineering of biomedical PQDs, along with their critical functions.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent Name | Function in Protocol | Key Property / Rationale for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard pristine ligands used in initial synthesis. | Provide colloidal stability during synthesis but are highly insulating and dynamically bound [9] [14]. |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Antisolvent for post-synthesis rinsing of PQD solid films. | Moderate polarity preserves PQD structure; hydrolyzes into conductive benzoate ligands [1]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Additive to ester antisolvents (e.g., MeBz). | Creates an alkaline environment that dramatically accelerates ester hydrolysis into target ligands [1]. |

| 2-Aminoethanethiol (AET) | Bi-functional ligand for in-situ or post-synthesis exchange. | Thiol group has strong affinity for Pb²⁺, forming a dense passivation layer that improves stability [9]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Cationic ligand for A-site post-treatment. | Substitutes OAm⁺; enhances electronic coupling between PQDs and passivates surface defects [14]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Standard polar antisolvent for purification and ligand exchange. | Hydrolyzes weakly into acetate ligands; can be used for initial ligand removal but is less effective than alkaline-augmented methods [1] [9]. |

Decision Support: Comparing Ligand Engineering Strategies

Selecting the appropriate ligand engineering strategy depends on the specific requirements of the target biomedical application. The table below provides a direct comparison to guide this decision.

Table 2: In-situ vs. Post-Synthesis Ligand Engineering Comparison

| Parameter | In-situ Engineering | Post-Synthesis Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Achieve a homogeneous, stable ligand shell directly from synthesis. | Maximize ligand substitution efficiency to create a highly conductive shell. |

| Typical Ligands Used | Short-chain acids/amines, bi-functional passivating ligands [9] [14]. | Conductive anions (e.g., benzoate), cationic salts (e.g., FAI), dense passivators (e.g., AET) [1] [14]. |

| Impact on Conductivity | Moderate improvement. | Can achieve high improvement via near-complete replacement of insulators [1]. |

| Structural Integrity | High, as no harsh post-treatment is required. | At risk; polar solvents during exchange can damage the ionic PQD core [14]. |

| Process Complexity | Lower; integrated into a single synthesis step. | Higher; requires additional steps and careful control of exchange conditions. |

| Best Suited For | Applications prioritizing high stability and simplified workflow. | Applications where maximizing charge transport and performance is critical. |

Advanced Topic: Application-Oriented Ligand Design

Moving beyond basic conductivity, the ultimate goal for biomedical PQDs is to engineer ligands that confer advanced functionality and biocompatibility.

- Biocompatibility and Toxicity Reduction: A primary strategy is the development of carbon-based QDs and the use of hydrophilic ligands to improve water solubility and reduce toxicity concerns associated with heavy metal cores [30]. Ligand engineering is key to making PQDs safer for in vivo applications.

- Targeting and Specificity: For drug delivery or specific imaging, ligands can be engineered to include functional groups (e.g., peptides, antibodies) that actively target specific cell types or biomarkers [31]. This transforms the PQD from a simple probe into a targeted theranostic agent.

By integrating these protocols and principles, researchers can systematically overcome the challenge of insulating ligands and advance the development of high-performance, biomedical-grade perovskite quantum dots.

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) have emerged as a revolutionary class of materials for optoelectronic applications, including biosensing and bioimaging. Their superior photophysical properties—such as near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield, tunable emission, and high extinction coefficients—make them ideal fluorescent probes for visualizing biological processes and detecting biomarkers [32]. However, a significant inherent obstacle impedes their performance: the insulating nature of their native surface ligands.

Colloidal PQDs are typically capped with long-chain organic ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). These ligands are essential for stabilizing the nanocrystals during synthesis and preventing aggregation. Unfortunately, they also act as insulating barriers, severely impeding charge transfer and inter-particle electronic coupling [14] [12]. This compromised charge carrier mobility results in diminished signal intensity and slower response times, which is detrimental for applications requiring high sensitivity and speed, such as detecting low-abundance biomarkers or real-time cellular imaging. Consequently, overcoming this insulating capping is a central theme in advancing PQD-based biomedical technologies. The following sections provide a technical troubleshooting guide to help researchers diagnose, address, and overcome these challenges in their experiments.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

FAQ 1: Why does my PQD-based biosensor exhibit low signal-to-noise ratio and poor sensitivity?

- Problem: The primary culprit is often the residual long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., OA/OAm) on the PQD surface. These ligands create a physical barrier that hinders efficient charge or energy transfer between the PQD and the target analyte, leading to a weak signal.

- Solution: Implement a ligand exchange strategy to replace insulating ligands with shorter, conductive ones.

- Recommended Protocol (Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis):

- Prepare your PQD solid film via spin-coating.

- For the interlayer rinsing step, use a methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent containing a small, optimized concentration of Potassium Hydroxide (KOH). The alkaline environment drastically accelerates the hydrolysis of the ester into conductive benzoate ligands and facilitates the substitution of the pristine insulating oleate ligands [1].

- This treatment can load up to twice the conventional amount of conductive ligands, leading to fewer trap-states, minimal particle agglomeration, and significantly enhanced charge transport [1].

- Recommended Protocol (Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis):

FAQ 2: How can I prevent my PQD probes from aggregating or decomposing in aqueous biological media?

- Problem: Ligand exchange with short ligands can destabilize the PQDs, making them susceptible to aggregation, ion release, and rapid degradation when exposed to water or polar solvents found in biological buffers.

- Solution: Employ a surface passivation and encapsulation approach.

- Recommended Protocol (Silica Coating):

- After conducting ligand exchange to ensure conductivity, grow a dense, conformal SiO₂ layer around each PQD.

- This inorganic shell effectively mitigates water permeation and prevents the release of toxic Pb²⁺ ions, ensuring long-term stability and biocompatibility [32].

- The silica coating also provides a chemically inert surface that can be further functionalized with biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, peptides) for targeted biosensing and bioimaging [32].

- Recommended Protocol (Silica Coating):

FAQ 3: My PQD bioimaging agent shows reduced fluorescence quantum yield after surface modification. What went wrong?

- Problem: The ligand exchange process can create surface defects (e.g., lead or halide vacancies) that act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching the photoluminescence.

- Solution: Combine conductive ligand exchange with defect passivation.

- Action: After the initial ligand exchange with short-chain ligands, introduce specific passivating molecules. Formamidinium iodide (FAI), cesium acetate (CsAc), or guanidinium thiocyanate have been shown to effectively passivate surface defects, prolong charge carrier lifetime, and recover high photoluminescence quantum yield [14].

Performance Data and Material Comparisons

The table below summarizes quantitative data on how different ligand engineering strategies impact key performance metrics for PQDs in optoelectronic devices, which directly correlate with biosensing and bioimaging performance.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Engineering Strategies on PQD Performance Metrics

| Strategy | Key Reagents | Reported Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) in Solar Cells | Key Improvements Relevant to Biosensing/Bioimaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-situ Ligand Engineering | Various alternative ligands during synthesis | N/A (Focus on synthesis) | Improved colloidal stability and initial optoelectronic properties [14]. |

| Conventional Ester Rinsing | Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Up to ~16.6% (for context) | Partial replacement of insulating ligands; moderate conductivity improvement [14] [1]. |

| Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange | Formamidinium Iodide / Cesium Acetate | ~16.6% (certified) | Enhanced dot-to-dot electronic coupling and prolonged charge carrier lifetime [14]. |

| Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis | Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) + KOH | 18.3% (certified) | Fewer trap-states, homogeneous film, superior conductive capping, and enhanced charge extraction [1]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Toolkit for Enhancing PQD Conductivity and Stability

| Reagent Category | Example Reagents | Primary Function | Considerations for Bio-Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Anionic Ligands | Acetate (from MeOAc), Benzoate (from MeBz) | Replace insulating OA; enhance inter-particle charge transport [1]. | Short chains improve conductivity but may reduce stability in water. |

| Conductive Cationic Ligands | Formamidinium (FA+), Phenethylammonium (PEA+) | Replace insulating OAm+; improve A-site surface coverage and charge transport [14] [1]. | Can stabilize the perovskite lattice structure. |

| Passivation Agents | Guanidinium Thiocyanate | Passivate surface defects to reduce charge recombination and boost PL intensity [14]. | Crucial for maintaining high fluorescence in imaging. |

| Encapsulation Agents | SiO₂ precursors (e.g., Tetraethyl orthosilicate) | Form a protective shell to ensure stability and biocompatibility in aqueous media [32]. | Essential for any in vitro or in vivo application. |

| Alkaline Additives | Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Catalyze ester hydrolysis during ligand exchange, maximizing conductive ligand loading [1]. | Concentration must be optimized to avoid degrading the perovskite core. |

Experimental Protocol: Alkali-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis for Conductive PQD Films

This protocol is adapted from recent high-impact research to create highly conductive and stable PQD films ideal for device integration [1].

Objective: To effectively replace pristine long-chain insulating ligands (OA/OAm) with short, conductive benzoate ligands on FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQD surfaces.

Materials:

- Synthesized FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs in toluene (~25 mg/mL)

- Methyl Benzoate (MeBz)

- Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) pellets

- Anhydrous ethanol

- Substrates (e.g., glass, ITO)

Procedure:

- PQD Film Deposition: Spin-coat the PQD colloidal solution onto a pre-cleaned substrate to form an "as-cast" solid film.

- Prepare Alkaline Antisolvent: Dissolve a precise, low concentration of KOH (e.g., 0.2 mg/mL) into neat MeBz. The solution must be prepared fresh and used immediately to prevent absorption of atmospheric CO₂.

- Interlayer Rinsing: While the PQD film is still wet, dynamically rinse it by dripping the KOH/MeBz solution onto the spinning film. This step facilitates the rapid hydrolysis of MeBz and the substitution of OA⁻ with benzoate.