Analytical vs Numerical Stress Calculations: A Roadmap for Optimized Surface Lattices in Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the integrated use of analytical and numerical methods for stress analysis in surface lattice optimization.

Analytical vs Numerical Stress Calculations: A Roadmap for Optimized Surface Lattices in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the integrated use of analytical and numerical methods for stress analysis in surface lattice optimization. It covers foundational principles, from mass balance in forced degradation to advanced machine-learned force fields, alongside practical methodologies for designing and simulating bio-inspired lattice structures. The content further details troubleshooting strategies for poor mass balance and optimization techniques, concluding with rigorous validation protocols and a comparative analysis of method performance to ensure accuracy, efficiency, and regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical applications.

Core Principles: From Pharmaceutical Stress Testing to Lattice Mechanics

The Critical Role of Mass Balance in Pharmaceutical Stress Testing

In the realm of pharmaceutical development, stress testing serves as a cornerstone practice for understanding drug stability and developing robust analytical methods. At the heart of this practice lies mass balance, a fundamental concept ensuring that all degradation products are accurately identified and quantified. Mass balance represents the practical application of the Law of Conservation of Mass to pharmaceutical degradation, providing scientists with critical insights into the completeness of their stability-indicating methods [1].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) defines mass balance as "the process of adding together the assay value and levels of degradation products to see how closely these add up to 100% of the initial value, with due consideration of the margin of analytical error" [1]. While this definition appears straightforward, its practical implementation presents significant challenges that vary considerably across pharmaceutical companies. These disparities can pose difficulties for health authorities reviewing drug applications, potentially delaying approvals [2]. This article explores the critical role of mass balance in pharmaceutical stress testing, examining its theoretical foundations, practical applications, calculation methodologies, and experimental protocols.

Theoretical Foundations of Mass Balance

Fundamental Principles

Mass balance rests upon the fundamental principle that matter cannot be created or destroyed during chemical reactions. When a drug substance degrades, the mass of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) lost must theoretically equal the total mass of degradation products formed [1]. This simple concept becomes complex in practice due to several factors affecting analytical measurements.

Two primary considerations impact mass balance assessments:

- Detection variability: Reactants and degradation products are not necessarily detected with the same sensitivity (response factors), if detected at all

- Multiple reactants: The API is not necessarily the only reactant in formulated drug products, where excipients and other components may participate in degradation reactions [1]

Mass Balance Calculations and Metrics

To standardize the assessment of mass balance, scientists employ specific calculation methods. Two particularly useful constructs are Absolute Mass Balance Deficit (AMBD) and Relative Mass Balance Deficit (RMBD), which can be either positive or negative [1]:

Absolute Mass Balance Deficit (AMBD) = (Mp,0 - Mp,x) - (Md,x - Md,0)

Relative Mass Balance Deficit (RMBD) = [AMBD / (Mp,0 - Mp,x)] × 100%

Where:

- Mp,0 = initial mass of API

- Mp,x = final mass of API

- Md,x = final mass of degradation products

- Md,0 = initial mass of degradation products

These metrics provide quantitative measures of mass balance performance, with RMBD being particularly valuable as it expresses relative inaccuracy independent of the extent of degradation [1].

Table 1: Mass Balance Performance Classification Based on Relative Mass Balance Deficit (RMBD)

| RMBD Range | Mass Balance Classification | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| -10% to +10% | Excellent | Near-perfect mass balance |

| -15% to -10% or +10% to +15% | Acceptable | Minor analytical variance |

| < -15% or > +15% | Poor | Significant mass imbalance requiring investigation |

Mass Balance in Pharmaceutical Stress Testing: Practical Applications

Role in Analytical Method Development

Mass balance assessments play a critical role in validating stability-indicating methods (SIMs), which are required by ICH guidelines for testing attributes susceptible to change during storage [1]. These methods must demonstrate they can accurately detect and quantify pharmaceutically relevant degradation products that might be observed during manufacturing, long-term storage, distribution, and use [2].

For synthetic peptides and polypeptides, mass balance assessments address two fundamental questions about analytical method suitability:

- Across all release testing methods, is the entirety of the drug substance mass (including impurities) detected and accounted for?

- Do stability-indicating purity methods demonstrate mass balance when comparing the decrease in assay to the increase in total impurities during stability studies? [3]

Regulatory Significance

Regulatory agencies place significant emphasis on mass balance assessments during drug application reviews. The 2024 review by Marden et al. noted that disparities in how different pharmaceutical companies approach mass balance can create challenges for health authorities, potentially delaying drug application approvals [2]. This has led to initiatives to develop science-based approaches and technical details for assessing and interpreting mass balance results.

For therapeutic peptides, draft regulatory guidance from the European Medicines Agency lists mass balance as an attribute to be included in drug substance specifications [3]. However, the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) 〈1503〉 does not mandate mass balance as a routine quality control test but recognizes its value for determining net peptide content in reference standards [3].

Experimental Protocols for Mass Balance Assessment

Stress Testing Methodologies

Stress testing, also known as forced degradation, involves exposing drug substances and products to severe conditions to deliberately cause degradation. These studies aim to identify likely degradation products, establish degradation pathways, and validate stability-indicating methods [2]. Common stress conditions include:

- Acidic and basic hydrolysis: Using solutions like 0.1M HCl or 0.1M NaOH

- Oxidative stress: Using hydrogen peroxide or other oxidizers

- Thermal degradation: Exposure to elevated temperatures

- Photolytic degradation: Exposure to UV or visible light

Table 2: Typical Stress Testing Conditions for Small Molecule Drug Substances

| Stress Condition | Typical Parameters | Primary Degradation Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Acidic Hydrolysis | 0.1M HCl, 40-60°C, several days | Hydrolysis, rearrangement |

| Basic Hydrolysis | 0.1M NaOH, 40-60°C, several days | Hydrolysis, dehalogenation |

| Oxidative Stress | 0.3-3% H2O2, room temperature, 24 hours | Oxidation, N-oxide formation |

| Thermal Stress | 70-80°C, solid state, several weeks | Dehydration, pyrolysis |

| Photolytic Stress | UV/Vis light, ICH conditions | Photolysis, radical formation |

Analytical Techniques for Mass Balance Assessment

Multiple analytical techniques are employed to achieve comprehensive mass balance assessments:

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV Detection

- Primary technique for assay and related substances determination

- Typically uses C18 stationary phases with gradient elution

- UV detection at appropriate wavelengths (often 214 nm for peptides) [3]

Advanced Detection Techniques

- Charged aerosol detection (CAD): Provides more uniform response factors for non-UV absorbing compounds

- Chemiluminescent nitrogen-specific detection: Enables response factor determination based on nitrogen content

- LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry): Critical for identifying unknown degradation products [1]

Mass Balance Workflow for Pharmaceutical Stress Testing

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for conducting mass balance assessments in pharmaceutical stress testing:

Mass Balance Assessment Workflow

Causes and Investigation of Mass Imbalance

Common Causes of Mass Imbalance

Mass imbalance can arise from multiple sources, which Baertschi et al. categorized in a modified Ishikawa "fishbone" diagram [1]. The primary causes include:

A. Undetected or Uneluted Degradants

- Volatile degradation products lost during sample preparation

- Highly polar or non-retained compounds not captured in chromatographic methods

- Compounds that co-elute with the API or other peaks

B. Response Factor Differences

- Degradation products with significantly different UV molar absorptivity than the API

- Non-UV absorbing compounds when using UV detection

- Differences in detector response for charged aerosol or other detection methods

C. Stoichiometric Mass Deficit

- Loss of small molecules (water, CO₂, HCl) during degradation

- Degradation pathways involving multiple steps with different stoichiometries

D. Recovery Issues

- Incomplete extraction of degradation products from the matrix

- Adsorption to container surfaces or filtration losses

- Degradation during sample preparation or analysis

E. Other Reactants

- Excipients in drug products participating in reactions

- Counterions contributing to mass changes

- Residual solvents or water affecting total mass

Investigation Protocols for Poor Mass Balance

When mass balance falls outside acceptable limits (typically ±10-15%), systematic investigation is required. The 2024 review by Marden et al. provides practical approaches using real-world case studies [2]:

Step 1: Method Suitability Assessment

- Verify detector linearity for API and available degradation standards

- Confirm chromatographic resolution between known degradation products

- Evaluate sample stability during analysis

Step 2: Response Factor Determination

- Synthesize or isolate key degradation products

- Determine relative response factors using authentic standards

- Apply correction factors or develop new methods if significant differences exist

Step 3: Comprehensive Peak Tracking

- Employ LC-MS with multiple ionization techniques to detect unknown degradants

- Use orthogonal separation methods (different stationary phases, HILIC, etc.)

- Implement high-resolution MS for structural elucidation of unknown peaks

Step 4: Recovery Studies

- Perform standard addition experiments with known degradation products

- Evaluate extraction efficiency and sample preparation losses

- Assess filtration and adsorption effects

Case Studies and Applications

Small Molecule Drug Substances

For small molecule pharmaceuticals, mass balance assessments during stress testing have revealed critical insights into degradation pathways. In one case study, a drug substance subjected to oxidative stress showed only 85% mass balance using standard HPLC-UV methods. Further investigation using LC-MS identified two polar degradation products that were poorly retained and not adequately detected in the original method. Method modification to include a polar-embedded stationary phase and gradient elution improved mass balance to 98% [2].

Therapeutic Peptides and Polypeptides

Mass balance presents unique challenges for peptide and polypeptide therapeutics due to their complex structure and potential for multiple degradation pathways. A case study on a synthetic peptide demonstrated excellent mass balance (98-102%) at drug substance release when accounting for the active peptide, related substances, water, residual solvents, and counterions [3].

For stability studies of therapeutic peptides, mass balance assessments have proven valuable in validating stability-indicating methods. When degraded samples showed a 15% decrease in assay value, the increase in total impurities accounted for 14.2% of the original mass, resulting in an RMBD of -5.3%, well within acceptable limits [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Mass Balance Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Mass Balance Assessment | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC Grade Solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Mobile phase components for chromatographic separation | Reversed-phase HPLC analysis of APIs and degradants |

| Buffer Salts (Ammonium formate, phosphate salts) | Mobile phase modifiers for pH control and ionization | Improving chromatographic separation and peak shape |

| Forced Degradation Reagents (HCl, NaOH, H₂O₂) | Inducing degradation under stress conditions | Hydrolytic and oxidative stress testing |

| Authentic Standards (API, known impurities) | Method qualification and response factor determination | Quantifying degradation products relative to API |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample cleanup and concentration | Isolating degradation products for identification |

| LC-MS Compatible Mobile Phase Additives (Formic acid, TFA) | Enhancing ionization for mass spectrometric detection | Identifying unknown degradation products |

Mass balance remains a critical component of pharmaceutical stress testing, serving as a key indicator of analytical method suitability and comprehensive degradation pathway understanding. While the concept is simple in theory, its practical application requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including detection capabilities, response factors, stoichiometry, and recovery. The recent collaborative efforts to standardize mass balance assessments across pharmaceutical companies represent a significant step toward harmonized practices that will benefit both industry and regulatory agencies.

As demonstrated through case studies and experimental protocols, thorough mass balance assessments during pharmaceutical development build confidence in analytical methods and overall product control strategies. For complex molecules like therapeutic peptides, mass balance provides particularly valuable insights that support robust control strategies throughout the product lifecycle. By adhering to science-based approaches and investigating mass imbalances when they occur, pharmaceutical scientists can ensure the development of reliable stability-indicating methods that protect patient safety and drug product quality.

Fundamentals of Force Fields and Interatomic Potentials in Molecular Modeling

In the context of analytical versus numerical stress calculations for surface lattice optimization research, the selection of an interatomic potential is foundational. These mathematical models define the energy of a system as a function of atomic coordinates, thereby determining the forces acting on atoms and the resulting stress distributions within lattice structures. The accuracy of subsequent simulations—whether predicting the mechanical strength of a meta-material or optimizing a pharmaceutical crystal structure—depends critically on the fidelity of the underlying potential. Modern computational chemistry employs a hierarchy of approaches, from empirical force fields to quantum-mechanically informed machine learning potentials, each with characteristic trade-offs between computational efficiency, transferability, and accuracy. This guide objectively compares these methodologies, supported by recent experimental benchmarking data, to inform researchers' selection of appropriate models for lattice-focused investigations.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Comparison

Interatomic potentials aim to approximate the Born-Oppenheimer potential energy surface (PES), which is the universal solution to the electronic Schrödinger equation with nuclear positions as parameters [4]. The fundamental challenge lies in capturing the complex, many-body interactions that govern atomic behavior with sufficient accuracy for scientific prediction.

Traditional Empirical Force Fields utilize fixed mathematical forms with parameters derived from experimental data or quantum chemical calculations. Their functional forms are relatively simple, describing bonding interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics) through harmonic, Lennard-Jones, and Coulombic terms. While computationally efficient, their pre-defined forms limit their ability to describe systems or configurations far from their parameterization domain.

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (ML-IAPs) represent a paradigm shift. Instead of using a fixed functional form, they employ flexible neural network architectures to learn the PES directly from large, high-fidelity quantum mechanical datasets [5]. Models like Deep Potential (DeePMD) and MACE achieve near ab initio accuracy by representing the total potential energy as a sum of atomic contributions, each a complex function of the local atomic environment within a cutoff radius [5]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with geometric equivariance are particularly impactful, as they explicitly embed physical symmetries (E(3) group actions: translation, rotation, and reflection) into the model architecture. This ensures that scalar outputs like energy are invariant, and vector outputs like forces transform correctly, leading to superior data efficiency and physical consistency [5].

Machine Learning Hamiltonian (ML-Ham) approaches go a step further by learning the electronic Hamiltonian itself, enabling the prediction of electronic properties such as band structures and electron-phonon couplings, in addition to atomic forces and energies [5]. These "structure-physics-property" models offer enhanced explainability and a clearer physical picture compared to direct structure-property mapping of ML-IAPs.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Interatomic Potential Types

| Potential Type | Theoretical Basis | Representative Methods | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Force Fields | Pre-defined analytical forms | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS | Computational efficiency; suitability for large systems and long timescales. | Limited transferability and accuracy; inability to describe bond formation/breaking. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (ML-IAPs) | Data-driven fit to quantum mechanical data | DeePMD [5], MACE [4], NequIP [5] | Near ab initio accuracy; high computational efficiency (compared to DFT); no fixed functional form. | Dependence on quality/quantity of training data; risk of non-physical behavior outside training domain. |

| Machine Learning Hamiltonian (ML-Ham) | Data-driven approximation of the electronic Hamiltonian | Deep Hamiltonian NN [5], Hamiltonian GNN [5] | Prediction of electronic properties; enhanced physical interpretability. | Higher computational cost than ML-IAPs; increased complexity of model training. |

| Quantum Chemistry Methods | First-principles electronic structure | Density Functional Theory (DFT) [6], Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) [7] | High accuracy; no empirical parameters; can describe bond breaking/formation. | Extremely high computational cost (O(N³) or worse); limits system size and simulation time. |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

The development of benchmarks like LAMBench has enabled rigorous, large-scale comparison of modern Large Atomistic Models (LAMs), a category encompassing extensively pre-trained ML-IAPs [4]. Performance is evaluated across three critical axes: generalizability (accuracy on out-of-distribution chemical systems), adaptability (efficacy after fine-tuning for specific tasks), and applicability (stability and efficiency in real-world simulations like Molecular Dynamics) [4].

Accuracy on Lattice Energy and Force Predictions

The accuracy of a potential in predicting lattice energies is a critical metric, especially for crystal structure prediction and optimization. High-level quantum methods like Diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) are now establishing themselves as reference-quality data, sometimes surpassing the consistency of experimentally derived lattice energies [7].

Table 2: Benchmarking Lattice Energy and Force Prediction Accuracy

| Method / Model | System Type | Reported Accuracy (Lattice Energy) | Reported Accuracy (Forces) | Key Benchmark/Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMC (Diffusion Monte Carlo) | Molecular Crystals (X23 set) | Sub-chemical accuracy (~1-4 kJ/mol vs. CCSD(T)) [7] | - | Direct high-accuracy computation; serves as a reference [7]. |

| CCSD(T) | Small Molecules & Crystals | "Gold Standard" | - | Considered the quantum chemical benchmark for molecular systems [7]. |

| ML-IAPs (DeePMD) | Water | MAE ~1 meV/atom [5] | MAE < 20 meV/Å [5] | Trained on ~1 million DFT water configurations [5]. |

| DFT (with dispersion corrections) | Molecular Crystals | Varies significantly with functional; can achieve ~4 kJ/mol with best functionals vs. DMC [7] | - | Highly dependent on the exchange-correlation functional used [7]. |

Performance in Mechanical Property Prediction

For lattice optimization, the accurate prediction of mechanical properties is paramount. Top-down approaches that train potentials directly on experimental mechanical data are emerging as a powerful alternative when highly accurate ab initio data is unavailable [8].

Diagram 1: Top-down training workflow for experimental data.

A notable example is the use of the Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) method to learn a state-of-the-art graph neural network potential (DimeNet++) for diamond solely from its experimental stiffness tensor [8]. This method bypasses the need to differentiate through the entire MD simulation, avoiding exploding gradients and achieving a 100-fold speed-up in gradient computation [8]. The resulting NN potential successfully reproduced the experimental mechanical property, demonstrating a direct pathway to creating experimentally informed potentials for materials where quantum mechanical data is insufficient.

Research Reagents: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Software and Dataset "Reagents" for Force Field Development and Testing

| Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Lattice Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD-kit [5] | Software Package | Implements the Deep Potential ML-IAP framework for MD simulation. | Enables large-scale MD of lattice materials with near-DFT accuracy. |

| LAMBench [4] | Benchmarking System | Evaluates Large Atomistic Models on generalizability, adaptability, and applicability. | Provides a standardized platform for objectively comparing new and existing potentials. |

| MPtrj Dataset [4] | Training Dataset | A large dataset of inorganic materials from the Materials Project. | Used for pre-training domain-specific LAMs for inorganic material lattice simulations. |

| QM9, MD17, MD22 [5] | Benchmark Datasets | Datasets of small organic molecules and molecular dynamics trajectories. | Benchmarks model performance on organic molecules and biomolecular fragments. |

| X23 Dataset [7] | Benchmark Dataset | 23 molecular crystals with reference lattice energies. | Used for rigorous validation of lattice energy prediction accuracy. |

Application to Lattice Stress Analysis and Optimization

The choice of interatomic potential directly influences the outcome of stress analysis and topology optimization in lattice structures. In a study on additive manufacturing, a heterogeneous face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice structure was designed by replacing finite element mesh units with lattice units of different strut diameters, guided by a quasi-static stress field from an initial simulation [9]. The accuracy of the initial stress calculation, which dictates the final lattice design, is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the interatomic potential used to model the base material.

Furthermore, analytical models for predicting the compressive strength of micro-lattice structures (e.g., made from AlSi10Mg or WE43 alloys) rely on an accurate understanding of material yield behavior and deformation modes (bending- vs. stretching-dominated) [10]. Numerical finite element simulations used to validate these analytical models require constitutive laws that are ultimately derived from atomistic simulations using reliable interatomic potentials [10]. The integration of these scales—from atomistic potential to continuum mechanics—is crucial for the reliable design of optimized lattice structures.

The field of interatomic potentials is undergoing a rapid transformation driven by machine learning. While traditional force fields remain useful for specific, well-parameterized systems, ML-IAPs have demonstrated superior accuracy for a growing range of materials. Benchmarking reveals that the path toward a universal potential requires incorporating cross-domain training data and ensuring model conservativeness [4].

Future development will focus on active learning strategies to improve data efficiency, multi-fidelity frameworks that integrate data from different levels of theory, and enhanced interpretability of ML models [5]. For researchers engaged in analytical and numerical stress calculations for lattice optimization, the strategic selection of an interatomic potential—be it a highly specialized traditional force field or a broadly pre-trained ML-IAP—is no longer a mere preliminary step but a central determinant of the simulation's predictive power.

Fundamental Principles and Classifications

Lattice structures, characterized by periodic arrangements of unit cells with interconnected struts, plates, or sheets, represent a revolutionary class of materials renowned for their exceptional strength-to-weight ratios and structural efficiency [11]. Their mechanical behavior is fundamentally governed by two distinct deformation modes: stretching-dominated and bending-dominated mechanisms [12]. This classification stems from the Maxwell stability criterion, a foundational framework in structural analysis that predicts the rigidity of frameworks based on nodal connectivity [13] [14].

Stretching-dominated lattices exhibit superior stiffness and strength because applied loads are primarily carried as axial tensions and compressions along the struts [15] [12]. This efficient load transfer mechanism allows their mechanical properties to scale favorably with relative density. In contrast, bending-dominated lattices deform primarily through the bending of their individual struts [12]. This results in more compliant structures that excel at energy absorption, as they can undergo large deformations while maintaining a steady stress level [12].

The determinant factor for this behavior is the nodal connectivity within the unit cell. Stretching-dominated behavior typically requires a higher number of connections per node, making the structure statically indeterminate or overdetermined (Maxwell parameter M ≥ 0) [13]. Bending-dominated structures have lower nodal connectivity, often functioning as non-rigid mechanisms (Maxwell parameter M < 0) [13].

Figure 1: Fundamental classification and characteristics of lattice structure deformation mechanisms.

Comparative Mechanical Performance

The mechanical performance of stretching-dominated and bending-dominated lattices differs significantly across multiple properties, as quantified by experimental and simulation studies. The table below summarizes key comparative data.

| Mechanical Property | Stretching-Dominated Lattices | Bending-Dominated Lattices |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Stiffness | Up to 100× higher than bending-dominated lattices [12] | Significantly lower relative to stretching-dominated [12] |

| Yield Strength | High strength, scales linearly with relative density (σ ∝ ρ) [15] | Lower strength, scales with ρ^1.5 [14] |

| Energy Absorption | High but can exhibit sudden failure [12] | Excellent due to large deformations and steady stress [12] |

| Post-Yield Behavior | Prone to catastrophic failure (buckling, shear bands) [12] | Ductile-like, maintains structural integrity [12] |

| Relative Density Scaling | Stiffness and strength scale linearly with relative density [15] | Stiffness and strength scale non-linearly [15] |

| Typical Topologies | Cubic, Octet, Cuboctahedron [15] | BCC, AFCC, Diamond [15] |

Table 1: Comparative mechanical properties of stretching-dominated versus bending-dominated lattice structures.

Post-Yield Softening Phenomenon

Post-yield softening (PYS), once thought to be exclusive to stretching-dominated lattices, has been observed in bending-dominated lattices at high relative densities [14]. In Ti-6Al-4V BCC lattices, PYS occurred at relative densities of 0.13, 0.17, and 0.25, but not at lower densities of 0.02 and 0.06 [14]. This phenomenon is attributed to increased contributions of stretching and shear deformation at higher relative densities, explained by Timoshenko beam theory, which considers all three deformation modes concurrently [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Quasi-Static Compression Testing for Lattice Classification

Objective: To characterize the mechanical behavior of lattice structures and classify their deformation mode through uniaxial compression testing.

Materials and Equipment:

- Specimens: Lattice structures fabricated via additive manufacturing (e.g., LPBF, LCD) [16] [14]

- Universal testing machine

- Digital image correlation system for strain measurement

- μ-CT scanner for defect analysis

Procedure:

- Fabrication: Fabricate lattice specimens with controlled relative densities using appropriate AM technology.

- Metrology: Characterize as-built geometry and defects using μ-CT scanning [14].

- Mounting: Place specimen on compression plate ensuring parallel alignment.

- Pre-load: Apply minimal pre-load to ensure contact.

- Compression: Conduct displacement-controlled compression at quasi-static strain rate.

- Data Acquisition: Record load-displacement data at high frequency.

- Post-test Imaging: Document failure modes via photography and microscopy.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate engineering stress (applied force/original cross-sectional area) and strain (displacement/original height).

- Identify initial peak stress and analyze post-yield behavior for PYS.

- Classify deformation mode based on stress-strain curve morphology and failure mechanisms.

Protocol: Finite Element Analysis for Mechanoregulation Studies

Objective: To simulate bone ingrowth potential in orthopedic implants using mechanoregulatory algorithms.

Workflow:

- Model Generation: Create 3D solid models in ANSYS SpaceClaim using Python scripts based on unit cell nodes and strut connections [15].

- Biphasic Domain: Use Boolean operations to create a granulation tissue domain representing the initial healing environment [15].

- Meshing: Apply appropriate mesh refinement to capture stress concentrations.

- Boundary Conditions: Apply physiological pressure loads simulating spinal fusion implant conditions [15].

- Simulation: Implement mechanoregulatory algorithm to compute mechanical stimuli (fluid shear stress and strain) sensed by cells.

- Tissue Differentiation: Apply differentiation rules based on biophysical stimulus to predict tissue type formation.

- Analysis: Quantify percentage of void space receiving optimal stimulation for mature bone growth [15].

Figure 2: Experimental and computational workflows for lattice analysis.

Advanced Hybrid and Programmable Lattices

Hybrid Lattice Designs

Hybrid strategies combine stretching and bending-dominated unit cells to achieve superior mechanical performance. Research demonstrates two effective approaches:

- Multi-cell Hybrids: The "FRB" structure arranges FCC (stretching-dominated) and BCC (bending-dominated) unit cells in a chessboard pattern, increasing compressive strength by 15.71% and volumetric energy absorption by 103.75% compared to pure BCC [16].

- Hybrid Unit Cells: The "Multifunctional" unit cell connects FCC and BCC central nodes, creating a novel topology that increases compressive strength by 74.30% and volumetric energy absorption by 111.30% compared to BCC [16].

Programmable Active Lattice Structures

Emerging research enables dynamic control of deformation mechanisms through programmable active lattice structures that can switch between stretching and bending-dominated states [13]. These metamaterials utilize shape memory polymers or active materials to change nodal connectivity through precisely programmed thermal activation, allowing a single structure to adapt its mechanical properties for different operational requirements [13].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Essential materials and computational tools for lattice deformation research include:

| Research Tool | Function & Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ti-6Al-4V Alloy | Biomedical lattice implants for bone ingrowth studies [15] | Spinal fusion cages, orthopedic implants [15] |

| 316L Stainless Steel | High-strength energy absorbing lattices [17] | LPBF-fabricated buffer structures [17] |

| Shape Memory Polymers | Enable programmable lattice structures [13] | 4D printed active systems [13] |

| UV Tough Resin | High-precision polymer lattices via LCD printing [16] | Hybrid lattice prototypes [16] |

| ANSYS SpaceClaim | Parametric lattice model generation [15] | Python API for unit cell creation [15] |

| Numerical Homogenization | Predicting effective stiffness of periodic lattices [12] | Calculation of Young's/shear moduli [12] |

Table 2: Essential research materials and computational tools for lattice deformation studies.

Applications and Performance Optimization

Biomedical Applications

In orthopedic implants, lattice structures balance mechanical properties with biological integration. Studies comparing 24 topologies found bending-dominated lattices like Diamond, BCC, and Octahedron stimulated higher percentages of mature bone growth across various relative densities and physiological pressures [15]. Their enhanced bone ingrowth capacity is attributed to higher fluid velocity and strain within the pores, creating favorable mechanobiological stimuli [15].

Energy Absorption Applications

For impact protection and energy management, hybrid designs optimize performance. A stress-field-driven hybrid gradient TPMS lattice demonstrated 19.5% greater total energy absorption and reduced peak stress on sensitive components to 28.5% of unbuffered structures [17]. These designs strategically distribute stretching and bending-dominated regions to maximize energy dissipation while minimizing stress transmission.

The selection between stretching and bending-dominated lattice designs represents a fundamental trade-off between structural efficiency and energy absorption capacity. Recent advances in hybrid and programmable lattices increasingly transcend this traditional dichotomy, enabling structures that optimize both properties for specific application requirements across biomedical, aerospace, and mechanical engineering domains.

Lattice structures, characterized by their repeating unit cells in a three-dimensional configuration, have emerged as a revolutionary class of materials with significant applications in aerospace, biomedical engineering, and mechanical design due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and energy absorption properties [11]. These engineered architectures are not a human invention alone; they are extensively found in nature, from the efficient honeycomb in beehives to the trabecular structure of human bones, which combines strength and flexibility for weight-bearing and impact resistance [11]. The mechanical performance of lattice structures is primarily governed by two fundamental deformation modes: stretching-dominated behavior, which provides higher strength and stiffness, and bending-dominated behavior, which offers superior energy absorption due to a longer plateau stress [10] [18]. Understanding these behaviors, along with the ability to precisely characterize them through both analytical and numerical methods, is crucial for optimizing lattice structures for specific engineering applications where weight reduction without compromising structural integrity is paramount.

The evaluation of lattice performance hinges on several key metrics, with strength-to-weight ratio (specific strength) and energy absorption capability being the most critical for structural and impact-absorption applications. The strength-to-weight ratio quantifies a material's efficiency in bearing loads relative to its mass, while energy absorption measures its capacity to dissipate impact energy through controlled deformation [11]. These properties are influenced by multiple factors including unit cell topology, relative density, base material properties, and manufacturing techniques. Recent advances in additive manufacturing (AM), particularly selective laser melting (SLM) and electron beam melting (EBM), have enabled the fabrication of complex lattice geometries with tailored mechanical and functional properties, further driving research into performance optimization [19] [10].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Lattice Topologies

Quantitative Comparison of Mechanical Properties

Experimental data from recent studies reveals significant performance variations across different lattice topologies. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for various lattice structures under compressive loading.

Table 1: Performance comparison of different lattice structures under compressive loading

| Lattice Topology | Base Material | Relative Density (%) | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Peak Strength (MPa) | Specific Energy Absorption (J/g) | Key Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional BCC [20] | Ti-6Al-4V | ~20-30% | - | - | - | Baseline for comparison |

| TCRC-ipv [20] | Ti-6Al-4V | Same as BCC | +39.2% | +59.4% | +86.1% | Optimal comprehensive mechanical properties |

| IWP-X [21] | Ti-6Al-4V | 45% | - | +122.06% | +282.03% | Enhanced strength and energy absorption |

| Multifunctional Hybrid [16] | Polymer Resin | - | - | +74.3% vs BCC | +111.3% (Volumetric) | High load-bearing applications |

| FRB Hybrid [16] | Polymer Resin | - | - | +15.71% vs BCC | +103.75% (Volumetric) | Lightweight energy absorption |

| Octet [18] | Polymer Resin | 20-30% | - | - | - | Stretch-dominated (M=0) |

| BFCC [18] | Polymer Resin | 20-30% | - | - | - | Bending-dominated (M=-9) |

| Rhombocta [18] | Polymer Resin | 20-30% | - | - | - | Bending-dominated (M=-18) |

| Truncated Octahedron [18] | Polymer Resin | 20-30% | - | - | - | Most effective for energy absorption |

Analysis of Topology-Performance Relationships

The data demonstrates that topology optimization significantly enhances lattice performance beyond conventional designs. The trigonometric function curved rod cell-based lattice (TCRC-ipv) achieves remarkable improvements of 39.2% in elastic modulus, 59.4% in peak compressive strength, and 86.1% in specific energy absorption compared to traditional BCC structures [20]. This performance enhancement stems from the curvature continuity at nodes, which eliminates geometric discontinuities and reduces stress concentration factors from theoretically infinite values in traditional BCC structures to finite, manageable levels through curvature control [20].

Similarly, the IWP-X structure, which fuses an X-shaped plate with an IWP surface structure, demonstrates even more dramatic improvements of 122.06% in compressive strength and 282.03% in energy absorption over the baseline IWP design [21]. This highlights the effectiveness of hybrid approaches that combine different structural elements to create synergistic effects. The specific energy absorption (SEA) reaches its maximum in IWP-X at a plate-to-IWP volume ratio between 0.7 to 0.8, indicating the importance of optimal volume distribution in hybrid designs [21].

The deformation behavior directly correlates with topological characteristics described by the Maxwell number (M), calculated as M = s - 3n + 6, where s represents struts and n represents nodes [18]. Structures with M ≥ 0 exhibit stretch-dominated behavior with higher strength and stiffness, while those with M < 0 display bending-dominated behavior with better energy absorption. This theoretical framework provides valuable guidance for designing lattices tailored to specific application requirements.

Experimental Methodologies for Lattice Characterization

Standardized Compression Testing Protocols

The mechanical characterization of lattice structures primarily relies on quasi-static compression testing following standardized methodologies across studies. Specimens are typically manufactured using additive manufacturing techniques with precise control of architectural parameters. The standard experimental workflow involves several critical stages, as illustrated below:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for lattice structure characterization

For metallic lattices, specimens are typically fabricated using selective laser melting (SLM) with parameters carefully optimized for each material. For Ti-6Al-4V alloys, standard parameters include laser power of 280W, scanning speed of 1000 mm/s, hatch distance of 0.1 mm, and layer thickness of 0.03 mm [21]. For aluminum alloys (AlSi10Mg), parameters of 350W laser power and 1650 mm/s scanning speed are employed, while for magnesium WE43, 200W laser power with 1100 mm/s scanning speed is used [10]. The entire fabrication process is conducted in an inert atmosphere (argon gas) to prevent oxidation, and specimens are cleaned of residual powder after printing using ultrasonic cleaning [21].

Compression tests are performed using universal testing machines with strain rates typically in the range of 5×10⁻⁴ s⁻¹ to 7×10⁻⁴ s⁻¹ to maintain quasi-static conditions [10]. The tests are conducted until 50-70% compression to capture the complete deformation response, including the elastic region, plastic plateau, and densification phase [18]. Force-displacement data is recorded throughout the test and converted to stress-strain curves for analysis.

Performance Metrics Calculation Methods

From the compression test data, key performance metrics are derived using standardized calculation methods:

- Elastic Modulus: Determined from the initial linear elastic region of the stress-strain curve (typically between 0.002 and 0.006 strain) [20].

- Peak Compressive Strength: Identified as the first maximum stress before specimen collapse [20].

- Energy Absorption Capacity: Calculated as the area under the stress-strain curve up to a specific strain value (usually 50% strain), representing the energy absorbed per unit volume [18].

- Specific Energy Absorption (SEA): Obtained by dividing the energy absorption capacity by the mass density, providing a mass-normalized measure of energy absorption efficiency [21].

For structures exhibiting progressive collapse behavior, additional metrics such as plateau stress (average stress between 20% and 40% strain) and densification strain (point where stress rapidly increases due to material compaction) are also calculated to characterize the energy absorption profile [18].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The experimental study of lattice structures requires specific materials and manufacturing technologies. The table below details essential research reagents and materials used in lattice structure research.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for lattice structure fabrication and testing

| Material/Technology | Function/Role | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy [21] | Primary material for high-strength lattices | Aerospace, biomedical implants | High strength-to-weight ratio, biocompatibility |

| AlSi10Mg Aluminum Alloy [10] | Lightweight lattice structures | Automotive, lightweight applications | High specific strength, good thermal properties |

| WE43 Magnesium Alloy [10] | Lightweight, biodegradable lattices | Biomedical implants, temporary structures | Biodegradable, low density |

| 316L Stainless Steel [19] | Corrosion-resistant lattices | Medical devices, marine applications | Excellent corrosion resistance, good ductility |

| UV-Curable Polymer Resins [16] | Rapid prototyping of lattice concepts | Conceptual models, functional prototypes | High printing precision, fast processing |

| Selective Laser Melting (SLM) [10] | Metal lattice fabrication | High-performance functional lattices | Complex geometries, high resolution |

| Stereolithography (SLA) [18] | Polymer lattice fabrication | Conceptual models, energy absorption studies | High precision, smooth surface finish |

| Finite Element Software (Abaqus) [21] | Numerical simulation of lattice behavior | Performance prediction, optimization | Nonlinear analysis, large deformation capability |

The choice of base material significantly influences lattice performance. Metallic materials like Ti-6Al-4V offer high strength and are suitable for load-bearing applications, while polymeric materials provide viscoelastic behavior enabling reversible energy absorption for sustainable applications [18] [21]. The manufacturing technique must be selected based on the material requirements and desired structural precision, with SLM and EBM being preferred for metallic lattices and VAT polymerization techniques like SLA and LCD printing suitable for polymeric systems [16].

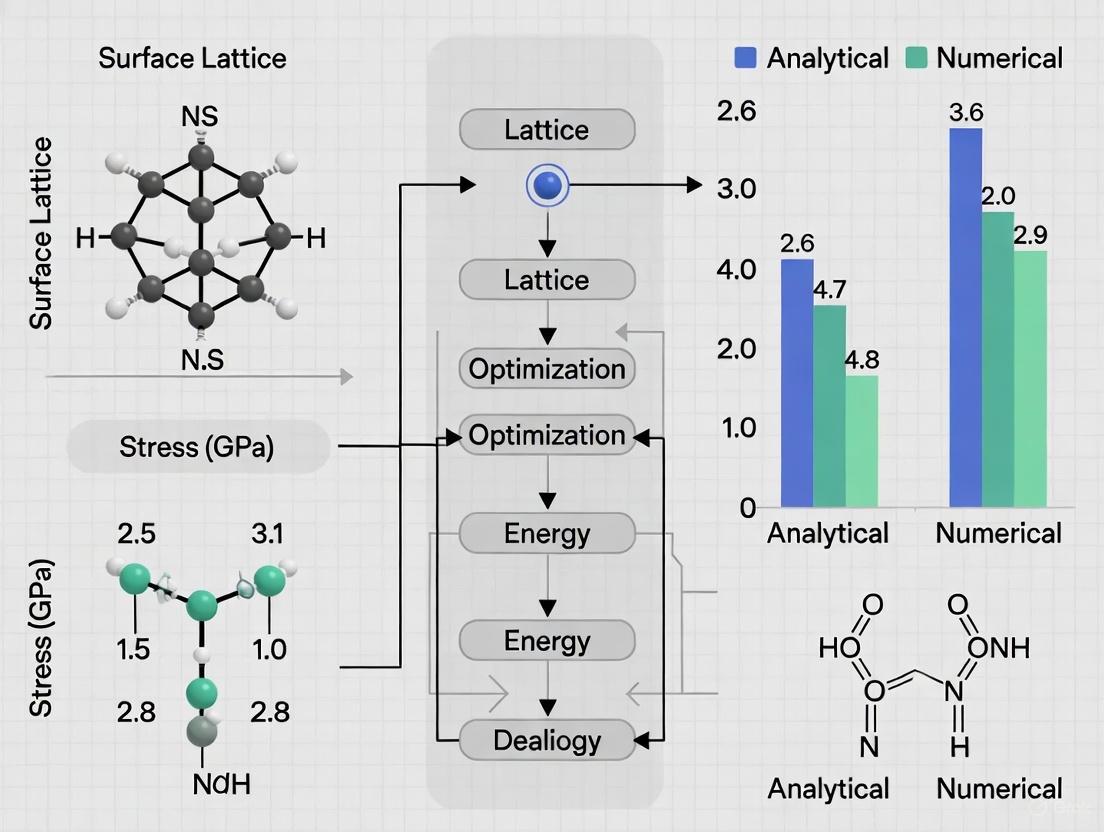

Analytical vs. Numerical Approaches in Lattice Optimization

Analytical Modeling Techniques

Analytical models for lattice structures are primarily based on plasticity limit analysis and beam theory, which provide closed-form solutions for predicting mechanical properties. Recent developments include a new analytical model for micro-lattice structures (MLS) that can determine the amounts of stretching-dominated and bending-dominated deformation in two configurations: cubic vertex centroid (CVC) and tetrahedral vertex centroid (TVC) [10]. These models utilize plastic moment concepts and beam theory to predict collapse strength by equating external work with plastic dissipation [10].

The analytical approach offers the advantage of rapid property estimation without computational expense, enabling initial design screening and providing physical insight into deformation mechanisms. However, these models face limitations in capturing complex behaviors such as material nonlinearity, manufacturing defects, and intricate cell geometries beyond simple cubic configurations. The accuracy of analytical models has been validated through comparison with experimental results for AlSi10Mg and WE43 MLS, showing good agreement for simpler lattice topologies [10].

Numerical Simulation Methods

Numerical approaches, particularly Finite Element Analysis (FEA), provide more comprehensive tools for lattice optimization. Advanced simulations using software platforms like ABAQUS/Explicit employ 10-node tetrahedral grid cells (C3D10) to model complex lattice geometries with nonlinear material behavior and large deformations [21]. These simulations effectively predict stress distribution, identify fracture sites, and capture the complete compression response including elastic region, plastic collapse, and densification.

Recent advances in numerical modeling include the development of multi-scale modeling techniques that combine microstructural characteristics with macroscopic lattice dynamics to improve simulation accuracy [19]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with numerical simulations is emerging as a powerful approach for rapid lattice optimization and property prediction [22]. The effectiveness of numerical methods has been demonstrated in predicting the performance of novel lattice designs like trigonometric curved rod structures and TPMS hybrids before fabrication, significantly reducing experimental costs and development time [20] [21].

Integrated Approach for Optimal Results

The most effective lattice optimization strategy combines both analytical and numerical approaches, using analytical models for initial screening and numerical simulations for detailed analysis of promising candidates. This integrated methodology is exemplified in the development of novel lattice structures like the TCRC-ipv and IWP-X, where theoretical principles guided initial design, and FEA enabled refinement before experimental validation [20] [21]. The synergy between these approaches provides both computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, accelerating the development of optimized lattice structures for specific application requirements.

The comprehensive comparison of lattice structures reveals that topological optimization through either curved-strut configurations or hybrid designs significantly enhances both strength-to-weight ratio and energy absorption capabilities. The performance improvements achieved by novel designs like TCRC-ipv (+86.1% SEA) and IWP-X (+282.03% energy absorption) demonstrate the substantial potential of computational design approaches over conventional lattice topologies [20] [21].

Future research directions in lattice optimization include the development of improved predictive computational models using artificial intelligence, scalable manufacturing techniques for larger structures, and multi-functional lattice systems integrating thermal, acoustic, and impact resistance properties [11]. Additionally, sustainability considerations will drive research into recyclable materials and energy-efficient manufacturing processes. The continued synergy between analytical models, numerical simulations, and experimental validation will enable the next generation of lattice structures with tailored properties for specific engineering applications across aerospace, biomedical, and automotive industries.

The cubic crystal system is one of the most common and simplest geometric structures found in crystalline materials, characterized by a unit cell with equal edge lengths and 90-degree angles between axes [23]. Within this system, three primary Bravais lattices form the foundation for understanding atomic arrangements in metallic and ionic compounds: the body-centered cubic (BCC), face-centered cubic (FCC), and simple cubic structures [23] [24]. These arrangements are defined by the placement of atoms at specific positions within the cubic unit cell, resulting in distinct packing efficiencies, coordination numbers, and mechanical properties that determine their suitability for various engineering applications.

In materials science and engineering, understanding these fundamental lattice structures is crucial for predicting material behavior under stress, designing novel heterogeneous lattice structures for additive manufacturing, and advancing research in structural optimization [25]. The BCC and FCC lattices represent two of the most important packing configurations found in natural and engineered materials, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications ranging from structural components to functional devices.

Fundamental Lattice Structures: BCC and FCC

Body-Centered Cubic (BCC) Structure

The body-centered cubic (BCC) lattice can be conceptualized as a simple cubic structure with an additional lattice point positioned at the very center of the cube [26] [24]. This arrangement creates a unit cell containing a net total of two atoms: one from the eight corner atoms (each shared among eight unit cells, contributing 1/8 atom each) plus one complete atom at the center [26] [27]. The BCC structure exhibits a coordination number of 8, meaning each atom within the lattice contacts eight nearest neighbors [26] [28].

In the BCC arrangement, atoms along the cube diagonal make direct contact, with the central atom touching the eight corner atoms [27]. This geometric relationship determines the atomic radius in terms of the unit cell dimension, expressed mathematically as (4r = \sqrt{3}a), where (r) represents the atomic radius and (a) is the lattice parameter [29]. The BCC structure represents a moderately efficient packing arrangement with a packing efficiency of approximately 68%, meaning 68% of the total volume is occupied by atoms, while the remaining 32% constitutes void space [28] [29].

Several metallic elements naturally crystallize in the BCC structure at room temperature, including iron (α-Fe), chromium, tungsten, vanadium, molybdenum, sodium, potassium, and niobium [26] [23] [28]. These metals typically exhibit greater hardness and less malleability compared to their close-packed counterparts, as the BCC structure presents more difficulty for atomic planes to slip over one another during deformation [28].

Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) Structure

The face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice features atoms positioned at each of the eight cube corners plus centered atoms on all six cube faces [23] [24]. This configuration yields a net total of four atoms per unit cell: eight corner atoms each contributing 1/8 atom (8 × 1/8 = 1) plus six face-centered atoms each contributing 1/2 atom (6 × 1/2 = 3) [23] [27]. The FCC structure exhibits a coordination number of 12, with each atom contacting twelve nearest neighbors [27] [28].

In the FCC lattice, atoms make contact along the face diagonals, establishing the relationship between atomic radius and unit cell dimension as (4r = \sqrt{2}a) [29]. This arrangement represents the most efficient packing for cubic systems, achieving a packing efficiency of approximately 74%, with only 26% void space [28] [29]. The FCC structure is also known as cubic close-packed (CCP), consisting of repeating layers of hexagonally arranged atoms in an ABCABC... stacking sequence [27].

Many common metals adopt the FCC structure, including aluminum, copper, nickel, lead, gold, silver, platinum, and iridium [23] [28] [30]. Metals with FCC structures generally demonstrate high ductility and malleability, properties exploited in metal forming and manufacturing processes [28] [30]. The FCC arrangement is thermodynamically favorable for many metallic elements due to its efficient atomic packing, which maximizes attractive interactions between atoms and minimizes total intermolecular energy [27].

Comparative Analysis of BCC and FCC Structures

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of BCC and FCC Lattice Structures

| Parameter | Body-Centered Cubic (BCC) | Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) |

|---|---|---|

| Atoms per Unit Cell | 2 [26] [27] | 4 [23] [27] |

| Coordination Number | 8 [26] [28] | 12 [27] [28] |

| Atomic Packing Factor | 68% [28] [29] | 74% [28] [29] |

| Relationship between Atomic Radius (r) and Lattice Parameter (a) | (r = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}a) [29] | (r = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{4}a) [29] |

| Closed-Packed Directions | <111> | <110> |

| Void Space | 32% [29] | 26% [29] |

| Common Metallic Examples | α-Iron, Cr, W, V, Mo, Na [26] [28] | Al, Cu, Au, Ag, Ni, Pb [23] [28] |

| Typical Mechanical Properties | Harder, less malleable [28] | More ductile, malleable [28] [30] |

Table 2: Multi-Element Cubic Structures in Crystalline Compounds

| Structure Type | Arrangement | Coordination Number | Examples | Space Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caesium Chloride (B2) | Two interpenetrating primitive cubic lattices [23] | 8 [23] | CsCl, CsBr, CsI, AlCo, AgZn [23] | Pm3m (221) [23] |

| Rock Salt (B1) | Two interpenetrating FCC lattices [23] | 6 [23] | NaCl, LiF, most alkali halides [23] | Fm3m (225) [23] |

Diagram 1: Structural relationships between cubic crystal systems, showing the hierarchy from the cubic crystal system to specific BCC and FCC lattices, their properties, and example materials. The diagram illustrates how different cubic structures share common classification while exhibiting distinct characteristics.

TPMS Structures: An Emerging Lattice Topology

Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMS) represent an important class of lattice structures characterized by minimal surface area for given boundary conditions and mathematical periodicity in three independent directions. These complex cellular structures are increasingly employed in engineering applications due to their superior mechanical properties, high surface-to-volume ratios, and multifunctional potential. While conventional BCC and FCC lattices derive from natural crystalline arrangements, TPMS structures are mathematically generated, enabling tailored mechanical performance for specific applications.

Unlike the node-and-strut architecture of BCC and FCC lattices, TPMS structures are based on continuous surfaces that divide space into two disjoint, interpenetrating volumes. Common TPMS architectures include Gyroid, Diamond, and Primitive surfaces, each offering distinct mechanical properties and fluid transport characteristics. These structures are particularly valuable in additive manufacturing applications, where their smooth, continuous surfaces avoid stress concentrations common at the joints of traditional lattice structures.

Experimental Protocols for Lattice Analysis

Computational Stress Analysis Methods

The investigation of lattice structures typically employs a combination of computational and experimental approaches. Finite element analysis (FEA) serves as the primary computational tool for evaluating stress distribution and structural integrity under various loading conditions. For lattice structures, specialized micro-mechanical models are developed to predict effective elastic properties, yield surfaces, and failure mechanisms based on unit cell architecture and parent material properties.

Recent advances in topology optimization techniques enable the design of functionally graded lattice structures with spatially varying densities optimized for specific loading conditions [25]. These methodologies iteratively redistribute material within a design domain to minimize compliance while satisfying stress constraints, resulting in lightweight, high-performance components particularly suited for additive manufacturing applications [25]. The integration of homogenization theory with optimization algorithms allows researchers to efficiently explore vast design spaces of potential lattice configurations.

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Experimental validation of lattice mechanical properties typically employs standardized mechanical testing protocols. Uniaxial compression testing provides fundamental data on elastic modulus, yield strength, and energy absorption characteristics. Digital image correlation (DIC) techniques complement mechanical testing by providing full-field strain measurements, enabling researchers to identify localized deformation patterns and validate computational models.

Micro-computed tomography (μ-CT) serves as a crucial non-destructive evaluation tool for quantifying manufacturing defects, dimensional accuracy, and surface quality of lattice structures. The integration of μ-CT data with finite element models, known as image-based finite element analysis, enables highly accurate predictions of mechanical behavior that account for as-manufactured geometry rather than idealized computer-aided design models.

Diagram 2: Research workflow for lattice structure evaluation, showing the cyclic process from initial design through computational modeling, manufacturing, testing, and characterization, culminating in model validation and design refinement.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Lattice Structure experimentation

| Research Material/Equipment | Function/Application | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Base Metal Powders | Raw material for additive manufacturing of metallic lattices | Particle size distribution: 15-45 μm for SLM; sphericity >0.9 [25] |

| Finite Element Software | Computational stress analysis and topology optimization | Capable of multiscale modeling and nonlinear material definitions [25] |

| μ-CT Scanner | Non-destructive 3D characterization of as-built lattices | Resolution <5 μm; compatible with in-situ mechanical staging |

| Digital Image Correlation System | Full-field strain measurement during mechanical testing | High-resolution cameras (5+ MP); speckle pattern application kit |

| Universal Testing System | Quasi-static mechanical characterization | Load capacity 10-100 kN; environmental chamber capability |

Performance Comparison and Applications

Mechanical Behavior Under Stress

The structural performance of BCC, FCC, and TPMS lattices varies significantly under different loading conditions. BCC lattices typically exhibit lower stiffness and strength compared to FCC lattices at equivalent relative densities due to their bending-dominated deformation mechanism [28]. In contrast, FCC lattices display stretch-dominated behavior, generally providing superior mechanical properties but with greater anisotropy. TPMS structures often demonstrate a unique combination of properties, with continuous surfaces distributing stress more evenly and potentially offering improved fatigue resistance.

Research has demonstrated that hybrid approaches, combining different lattice types within functionally graded structures, can optimize overall performance for specific applications. For instance, BCC lattices may be strategically placed in regions experiencing lower stress levels to reduce weight, while FCC or reinforced TPMS structures are implemented in high-stress regions to enhance load-bearing capacity [25]. This heterogeneous approach to lattice design represents the cutting edge of structural optimization research.

Application-Specific Considerations

The selection of appropriate lattice topology depends heavily on the application requirements and manufacturing constraints. BCC structures, with their relatively open architecture and interconnected voids, find application in lightweight structures, heat exchangers, and porous implants where fluid transport or bone ingrowth is desirable [28]. FCC lattices, with their higher stiffness and strength, are often employed in impact-absorbing structures and high-performance lightweight components.

TPMS structures exhibit exceptional performance in multifunctional applications requiring combined structural efficiency and mass transport capabilities, such as catalytic converters, heat exchangers, and advanced tissue engineering scaffolds. Their continuous surface topology and inherent smoothness also make them particularly suitable for fluid-flow applications where pressure drop minimization is critical.

The comparative analysis of BCC, FCC, and TPMS lattice structures reveals a complex landscape of architectural possibilities, each with distinct advantages for specific applications. BCC structures offer moderate strength with high permeability, FCC lattices provide superior mechanical properties at the expense of increased material usage, and TPMS architectures present opportunities for multifunctional applications requiring combined structural and transport properties. The ongoing research in stress-constrained topology optimization of heterogeneous lattice structures continues to expand the design space, enabling increasingly sophisticated application-specific solutions [25].

Future developments in lattice structure research will likely focus on multi-scale optimization techniques, functionally graded materials, and AI-driven design methodologies that further enhance mechanical performance while accommodating manufacturing constraints. As additive manufacturing technologies advance in resolution and material capabilities, the implementation of optimized lattice structures across industries from aerospace to biomedical engineering will continue to accelerate, driving innovation in lightweight, multifunctional materials design.

Computational Workflows: From DFT to Finite Element Analysis for Lattice Design

Applying Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Molecular-Level Stress Predictions

The accurate prediction of molecular-level stress is a cornerstone in the design of advanced materials and pharmaceuticals, bridging the gap between atomic-scale interactions and macroscopic mechanical behavior. This domain is characterized by two fundamental computational philosophies: analytical methods, which rely on parametrized closed-form expressions, and numerical methods, which compute forces and stresses directly from electronic structure calculations. Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a primary numerical method, offering a first-principles pathway to predict stress and related mechanical properties without empirical force fields. Unlike classical analytical potentials, which often struggle with describing bond formation and breaking or require reparameterization for specific systems, DFT aims to provide a universally applicable, quantum-mechanically rigorous framework [31]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of DFT's performance against emerging alternatives, detailing the experimental protocols and data that define their capabilities and limitations in the context of surface lattice optimization research.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, performance metrics, and ideal use cases for DFT and its leading alternatives in molecular-level stress prediction.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Molecular-Level Stress Predictions

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Stress/Force Accuracy | Computational Cost | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-Principles (Quantum Mechanics) | High (with converged settings); Forces can have errors >1 meV/Å in some datasets [32] | Very High | High accuracy for diverse chemistries; broadly applicable [33] | Computationally expensive; choice of functional & basis set critical [34] [35] |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine Learning (Trained on DFT data) | DFT-level accuracy achievable (e.g., MAE ~0.1 eV/atom for energy, ~2 eV/Å for force) [31] | Low (after training) | Near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the cost; enables large-scale MD [31] | Requires large, high-quality training datasets; transferability can be an issue [31] |

| Classical Force Fields (ReaxFF) | Empirical (Bond-Order based) | Moderate; often struggles with DFT-level accuracy for reaction pathways [31] | Low | Allows for simulation of very large systems and long timescales | Difficult to parameterize; lower fidelity for complex chemical environments [31] |

| DFT+U | First-Principles with Hubbard Correction | Improved for strongly correlated electrons (e.g., in metal oxides) [35] | High | Corrects self-interaction error in standard DFT for localized d/f electrons | Requires benchmarking to find system-specific U parameter [35] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Rigorous benchmarking against experimental data and high-level computational references is essential for evaluating the predictive power of these methods. The data below highlights key performance indicators.

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Predicted Properties

| Method & System | Predicted Property | Result | Reference Value | Deviation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (PBE) (General Molecular Dataset) | Individual Force Components | Varies by dataset quality | Recomputed with tight settings | MAE: 1.7 meV/Å (SPICE) to 33.2 meV/Å (ANI-1x) [32] | [32] |

| DFT (PBE0/TZVP) (Gas-Phase Reaction Equilibria) | Correct Equilibrium Composition (for non-T-dependent reactions) | 94.8% correctly predicted | Experimental Thermodynamics | Error ~5.2% | [34] |

| NNP (EMFF-2025) (C,H,N,O Energetic Materials) | Energy and Forces | MAE within ± 0.1 eV/atom (energy) and ± 2 eV/Å (forces) | DFT Reference Data | Matches DFT-level accuracy | [31] |

| DFT+U (PBE+U) (Rutile TiO₂) | Band Gap | Predicted with (Ud=8, Up=8 eV) | Experimental Band Gap | Significantly closer than standard PBE | [35] |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol for DFT Stress/Force Calculations

A robust DFT workflow for reliable stress and force predictions involves several critical steps:

- Geometry Selection: Obtain initial molecular or crystal structure from experimental databases (e.g., Cambridge Structural Database, Materials Project [35]) or through preliminary geometric optimization.

- Functional and Basis Set Selection: Choose an appropriate exchange-correlation functional (e.g., PBE [33], PBE0 [34], or ωB97M-V [36]) and a sufficiently large basis set (e.g., def2-TZVPD [36]). This choice is system-dependent and crucial for accuracy [34] [35].

- Numerical Convergence: Ensure tight convergence criteria for the self-consistent field (SCF) cycle and geometry optimization. Use fine DFT integration grids (e.g., DEFGRID3 in ORCA [32]) to minimize noise and errors in forces, which should ideally be below 1 meV/Å. Disabling approximations like RIJCOSX in some software versions can be necessary to eliminate significant nonzero net forces [32].

- Stress Calculation: For crystalline materials, the elastic tensor is computed by applying small, finite strains (typically ±0.01) to the equilibrium unit cell and calculating the resulting stress tensor from the derivative of the energy. Mechanical properties like Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio are then derived from the elastic tensor [33].

- Validation: Compare predicted structures, energies, and forces against experimental data or higher-level quantum chemistry methods where available. For forces, check that the net force on the system is near zero, which indicates a well-converged calculation [32].

Protocol for Training an NNP for Stress Prediction

Machine-learning interatomic potentials like the EMFF-2025 model are trained to emulate DFT:

- Dataset Generation: Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) using DFT to sample a diverse set of configurations, including equilibrium and non-equilibrium structures, for the target system. The OMol25 dataset exemplifies this with over 100 million DFT calculations [36].

- Data Labeling: Extract total energies, atomic forces, and stresses (if required) from the DFT calculations for each configuration.

- Model Training: Train a neural network (e.g., using the Deep Potential (DP) framework [31]) to map atomic environments to the DFT-labeled energies and forces. Transfer learning from a pre-trained general model (e.g., DP-CHNO-2024) can significantly reduce the amount of new data required [31].

- Model Validation: Validate the trained NNP on a held-out test set of configurations not seen during training. Metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in energy and forces are used to confirm the model reproduces DFT-level accuracy [31].

- Deployment: Use the validated NNP to run large-scale, long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations at a computational cost orders of magnitude lower than direct DFT.

Figure 1: A workflow for computational stress prediction, comparing the DFT and NNP pathways.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Datasets for Molecular Stress Predictions

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Stress Prediction | Relevant Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software Package | Performs DFT calculations to compute energies, forces, and stresses for periodic systems. | [35] |

| ORCA | Software Package | Performs DFT calculations on molecular systems; used to generate many modern training datasets. | [32] [36] |

| OMol25 Dataset | Dataset | Provides a massive, high-precision DFT dataset for training and benchmarking machine learning potentials. | [36] |

| DP-GEN | Software Tool | Automates the generation of machine learning potentials via active learning and the DP framework. | [31] |

| EMFF-2025 | Pre-trained NNP | A ready-to-use neural network potential for simulating energetic materials containing C, H, N, O. | [31] |

| Hubbard U Parameter | Computational Correction | Corrects DFT's self-interaction error in strongly correlated systems, improving property prediction. | [35] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores a paradigm shift in molecular-level stress prediction. While DFT remains the foundational, first-principles method for its generality and high accuracy, its computational cost restricts its direct application to the large spatiotemporal scales required for many practical problems in material and drug design. The emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials, trained on high-fidelity DFT data, represents a powerful hybrid approach, blending the accuracy of quantum mechanics with the scalability of classical simulations [31]. For researchers, the choice between a direct DFT study and an NNP-based campaign depends on the specific balance required between accuracy, system size, and simulation time. Future progress hinges on the development of more robust, transferable, and data-efficient MLIPs, backed by ever-larger and higher-quality quantum mechanical datasets like OMol25 [36]. Furthermore, addressing the inherent numerical uncertainties in even benchmark DFT calculations [32] will be crucial for establishing the next generation of reliable in silico stress prediction tools.

Developing Stability-Indicating Methods Through Forced Degradation Studies

Forced degradation studies represent a critical component of pharmaceutical development, serving to investigate stability-related properties of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and drug products. These studies involve the intentional degradation of materials under conditions more severe than accelerated stability protocols to reveal degradation pathways and products [37]. The primary objective is to develop validated analytical methods capable of precisely measuring the active ingredient while effectively separating and quantifying degradation products that may form under normal storage conditions [38].

Within the broader context of analytical versus numerical stress calculations in surface lattice optimization research, forced degradation studies represent the analytical experimental approach to stability assessment. This stands in contrast to emerging in silico numerical methods that computationally predict degradation chemistry. The regulatory guidance from ICH and FDA, while mandating these studies, remains deliberately general, offering limited specifics on execution strategies and stress condition selection [37] [39]. This regulatory framework necessitates that pharmaceutical scientists develop robust scientific approaches to forced degradation that ensure patient safety through comprehensive understanding of drug stability profiles.

The Role of Forced Degradation in Pharmaceutical Development

Forced degradation studies provide essential predictive data that informs multiple aspects of drug development. By subjecting drug substances and products to various stress conditions, scientists can identify degradation pathways and elucidate the chemical structures of resulting degradation products [37]. This information proves invaluable throughout the drug development lifecycle, from early candidate selection to formulation optimization and eventual regulatory submission.

Key Objectives and Applications

The implementation of forced degradation studies addresses several critical development needs:

- To develop and validate stability-indicating methods that can accurately quantify the API while resolving degradation products [38]

- To determine degradation pathways of drug substances and drug products during development phases [38]

- To identify impurities related to drug substances or excipients, including potentially genotoxic degradants [39]

- To understand fundamental drug molecule chemistry and intrinsic stability characteristics [38]

- To generate more stable formulations through informed selection of excipients and packaging [38]

- To establish degradation profiles that mimic what would be observed in formal stability studies under ICH conditions [38]

These studies are particularly beneficial when conducted early in development as they yield predictive information valuable for assessing appropriate synthesis routes, API salt selection, and formulation strategies [38].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Critical Stress Conditions

Forced degradation studies employ a range of stress conditions to evaluate API stability across potential environmental challenges. The typical conditions, as summarized in Table 1, include thermolytic, hydrolytic, oxidative, and photolytic stresses designed to generate representative degradation products [38].

Table 1: Typical Stress Conditions for APIs and Drug Products

| Stress Condition | Recommended API Testing | Recommended Product Testing | Typical Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat | ✓ | ✓ | 40-80°C |

| Heat/Humidity | ✓ | ✓ | 40-80°C/75% RH |

| Light | ✓ | ✓ | ICH Q1B option 1/2 |

| Acid Hydrolysis | ✓ | △ | 0.1-1M HCl, room temp-70°C |

| Alkali Hydrolysis | ✓ | △ | 0.1-1M NaOH, room temp-70°C |

| Oxidation | ✓ | △ | 0.1-3% H₂O₂, room temp |

| Metal Ions | △ | △ | Fe³⁺, Cu²⁺ |

✓ = Recommended, △ = As appropriate