Advanced Strategies for Suppressing Non-Radiative Recombination at Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces

Non-radiative recombination at perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces represents a critical bottleneck, limiting their efficiency and stability in optoelectronic devices and biomedical applications.

Advanced Strategies for Suppressing Non-Radiative Recombination at Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces

Abstract

Non-radiative recombination at perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces represents a critical bottleneck, limiting their efficiency and stability in optoelectronic devices and biomedical applications. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the fundamental mechanisms driving surface-mediated recombination losses, including defect states and blinking behaviors. We systematically review advanced surface passivation strategies, such as ligand engineering and hybrid coating methods, that effectively suppress these losses. Furthermore, we address key challenges in optimization and stability, presenting troubleshooting frameworks for common degradation pathways. The article also explores validation techniques and the translation of these strategies into high-performance devices, with a specific focus on sensitive biosensing and clinical diagnostics. This work serves as a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to harness the full potential of PQDs.

Unraveling the Roots of Loss: Fundamental Mechanisms of Non-Radiative Recombination in PQDs

FAQ: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: Why does my perovskite quantum dot (PQD) film exhibit low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY)? This is most frequently caused by non-radiative recombination at surface defects. Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide vacancies act as trap states, providing pathways for energy loss that compete with light emission [1] [2]. To confirm, perform time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopy; a short average carrier lifetime typically indicates significant non-radiative recombination.

Q2: My PQD solar cell efficiency degrades rapidly under ambient conditions. What surface defects are likely responsible? Halide vacancies are highly mobile and can facilitate ion migration, which accelerates decomposition upon exposure to moisture and oxygen [3] [2]. Furthermore, under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites at the surface are prone to reaction with water molecules, initiating the breakdown of the perovskite crystal structure.

Q3: After ligand passivation treatment, my PQD film's conductivity has dropped. What went wrong? You may have used an excess of long-chain, insulating ligands. While effective at passivation, these ligands can create barriers to charge transport between QDs [1] [2]. Consider switching to shorter-chain passivators like Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) or implementing a hybrid strategy that combines initial passivation with a subsequent ligand exchange to balance defect suppression and charge transport [4] [1].

Q4: How can I distinguish between the effects of Pb²⁺ defects and halide vacancies in my samples? These defects often have different spectroscopic signatures. Positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy can directly identify lead vacancies (VPb) [3]. Steady-state and TRPL are more general probes of overall defect density. A practical approach is to use targeted chemical treatments; for example, DDAB, which provides a bromide source, will primarily passivate halide vacancies and under-coordinated Pb²⁺, and the subsequent change in PLQY and lifetime can indicate the density of these specific defects [4] [1].

Diagnostic Data & Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Key Surface Defects in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Defect Type | Chemical Symbol | Primary Impact on Optoelectronics | Common Characterization Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Vacancy | V_Pb | Deep-level trap; strong hole trapping site; promotes non-radiative recombination [3]. | Positron Annihilation Lifetime Spectroscopy (PALS) [3] |

| Halide Vacancy | VBr, VI | Shallow trap; facilitates ion migration; reduces stability [2]. | Transient Photovoltage/Photocurrent, Ionic Conductivity Measurements |

| Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ | - | Deep-level trap; acts as a strong non-radiative recombination center [1] [2]. | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), FT-IR, TRPL |

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Surface Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Reagent | Target Defect | Reported Performance Improvement | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) | Halide vacancies, Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ | • PLQY increase from ~45% to ~90%• Exciton lifetime prolonged [1] | [1] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Surface trap states | • EQE of QLEDs: 10.13%• Efficiency roll-off at 200 mA/cm²: 1.5% [5] | [5] |

| SiO₂ Inorganic Shell | Environmental degradation | • Retained >90% of initial solar cell efficiency after 8 hours [4] | [4] |

Experimental Protocol 1: DDAB Passivation Treatment for CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating enhanced charge transfer and reduced non-radiative recombination [1].

- Synthesis: Synthesize CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs (Pure-QDs) via the standard hot-injection method using oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) as ligands.

- Purification: Purify the crude QD solution using standard antisolvent (e.g., acetone or ethyl acetate) centrifugation.

- Passivation: Re-disperse the purified QD pellet in a non-polar solvent like toluene or hexane. Under inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ glovebox), add a calculated amount of DDAB solution (in toluene) dropwise to the QD solution. A typical DDAB concentration used is 5 mg/mL [1].

- Incubation: Stir the mixture for 10-15 minutes at room temperature to allow ligand exchange and surface binding.

- Post-treatment Purification: Precipitate the DDAB-passivated QDs (DDAB-QDs) by adding an antisolvent, followed by centrifugation. Re-disperse the final pellet in the desired solvent for film fabrication or analysis.

Experimental Protocol 2: Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Passivation for Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs

This protocol outlines a synergistic approach for lead-free perovskites, combining organic ligand and inorganic shell passivation [4].

- Synthesis & Organic Passivation: Synthesize lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs via an antisolvent method. During synthesis, introduce DDAB to passivate surface defects organically.

- SiO₂ Coating: To the purified Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB PQD solution, add tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS). The typical volume of TEOS added is 2.4 mL [4].

- Hydrolysis & Encapsulation: Subject the mixture to controlled conditions to facilitate the hydrolysis of TEOS and the formation of a protective, amorphous SiO₂ layer around the PQDs.

- Aging and Purification: Allow the reaction to proceed for several hours to ensure complete shell formation, then purify the core-shell Cs₃Bi₂Br₉/DDAB/SiO₂ PQDs via centrifugation.

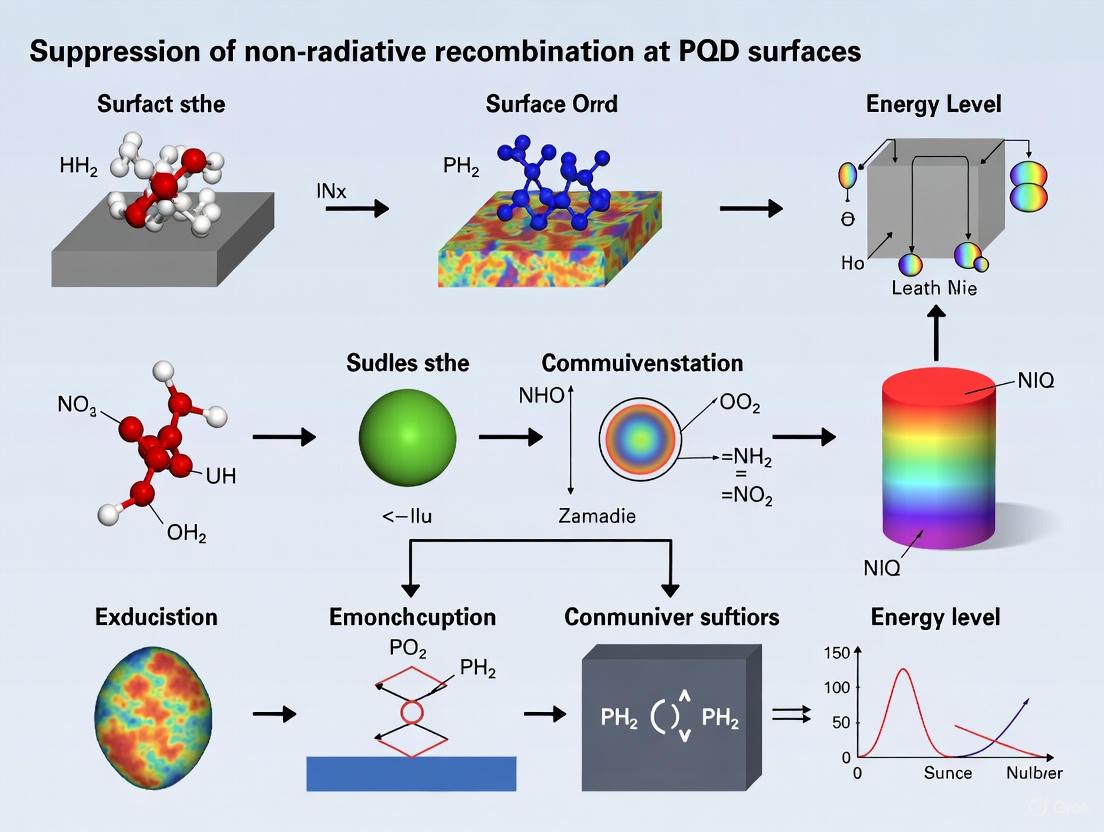

Defect Passivation Workflow & Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the strategic workflow for identifying and passivating major surface defects to suppress non-radiative recombination.

Diagram 1: Defect identification and passivation workflow.

The molecular mechanism of how passivators like DDAB bind to and heal surface defects is detailed below.

Diagram 2: Molecular mechanism of DDAB passivation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Surface Passivation Experiments

| Reagent | Primary Function | Example Use-Case & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) | Dual-function passivator: DDA⁺ cations coordinate with under-coordinated Pb²⁺, while Br⁻ anions fill bromide vacancies [4] [1]. | Use-case: Post-synthetic treatment of CsPbBr₃ or mixed-halide QDs. Rationale: Its short alkyl chain (vs. OA/OAm) improves charge transport while effectively suppressing non-radiative recombination [1]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Sulfate group acts as a strong Lewis base to coordinate with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, pacifying deep-level traps [5]. | Use-case: Ligand in room-temperature LARP synthesis of PQDs for LEDs. Rationale: Creates smooth, low-trap-density films that enable high-brightness QLEDs with very low efficiency roll-off [5]. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for forming an inert, amorphous SiO₂ inorganic shell that provides a physical barrier against moisture and oxygen [4]. | Use-case: Encapsulation of lead-free Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs. Rationale: Creates a hybrid organic-inorganic protection layer, synergistically enhancing long-term environmental stability for devices [4]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands for colloidal synthesis and stabilization of PQDs [2]. | Use-case: Initial synthesis and size control of PQDs. Rationale: Provides initial surface coverage but can lead to insulating films and dynamic binding; often requires partial exchange with more effective passivators [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Observed Problem: Your perovskite quantum dot (PQD) film or solar cell device exhibits a lower-than-expected PLQY, indicating severe non-radiative recombination.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution & Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Surface Defect Density (Unpassivated lead/halide vacancies) [6] [4] | Measure PLQY and fluorescence lifetime. A low PLQY with a short lifetime confirms non-radiative decay. [6] | Implement a dual-ligand passivation strategy. Use a combination of ligands (e.g., Eu(acac)3 for bulk and benzamide for surface defects) to simultaneously address different trap types. [6] |

| Ionic Defects and Grain Boundary Traps [7] | Perform thermal admittance spectroscopy or deep-level transient spectroscopy to quantify trap density and energy levels. | Apply advanced interface engineering. Post-treat the perovskite surface with multifunctional molecules like cage-like diammonium chloride (DCl) that contain both Lewis acid and base groups to passivate various defects. [8] |

| Poor Crystallinity & Residual PbI2 [8] | Use X-ray diffraction (XRD). A prominent PbI2 peak at ~12.5° indicates incomplete reaction and defective film. [8] | Optimize the crystallization process. Employ antisolvent engineering or additive strategies (e.g., DDAB) to improve crystal quality and suppress PbI2 formation. [4] |

Significant Open-Circuit Voltage (VOC) Deficit

Observed Problem: The open-circuit voltage of your perovskite solar cell is far below the theoretical maximum, leading to low power conversion efficiency.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution & Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Interfacial Energetic Misalignment [8] | Perform ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) to measure the work function and band alignment at interfaces. | Modulate the interfacial dipole. Introduce a polar, multifunctional molecule (e.g., DCl) at the perovskite/charge transport layer interface to optimize band alignment and reduce recombination losses. [8] |

| Trap-Assisted Recombination at Interfaces [7] [8] | Analyze dark J-V curves and ideality factor. An ideality factor >1 indicates significant trap-assisted recombination. | Employ a ferroelectric interlayer. Use a passivator that induces a phase-pure, in-plane oriented quasi-2D perovskite layer with ferroelectric properties to enhance charge separation and extraction. [8] |

| Bulk Non-Radiative Recombination [7] [9] | Use photoluminescence quantum yield mapping to identify spatial heterogeneity in recombination. | Precise compositional tuning and additive engineering. Incorporate additives like guanabenz acetate salt to prevent vacancy formation and crystallize high-quality films, especially for ambient-air fabrication. [9] |

Rapid Performance Degradation (Poor Stability)

Observed Problem: Your PQD-based device or film rapidly loses its optical or electronic performance under ambient conditions.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution & Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Detachment & Surface Degradation [6] [4] | Monitor PL intensity over time in air. A rapid decay suggests poor surface protection. | Apply a hybrid organic-inorganic coating. First, passivate with a strong-binding organic ligand (e.g., DDAB), then encapsulate with an inorganic shell (e.g., SiO2) for robust protection. [4] |

| Ion Migration [7] | Characterize current-voltage (I-V) hysteresis. A large hysteresis is often linked to ion migration. | Strengthen grain boundaries. Use molecular binders like uracil in the perovskite film, which effectively passivates defects and strengthens grain boundaries, improving mechanical and operational stability. [9] |

| Phase Instability & Hydration [9] | Observe film color change or perform XRD over time to detect phase impurities. | Utilize lattice strain engineering. Incorporate additives like β-poly(1,1-difluoroethylene) to stabilize the desired perovskite black phase and enhance thermal-cycling stability. [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common types of defects that create non-radiative pathways in metal-halide perovskites?

The most prevalent and detrimental defects are point defects (vacancies, interstitials, anti-sites) and surface/interface traps [7] [10]. Specifically:

- Pb²⁺ and Br⁻ Vacancies: These are common, low-energy formation defects that create deep-level traps, acting as efficient centers for non-radiative recombination via multiphonon emission or the trap-assisted Auger-Meitner process, especially in wider bandgap perovskites [10] [6].

- Under-coordinated Ions at Surfaces and Grain Boundaries: The termination of the crystal lattice creates dangling bonds that form shallow and deep trap states. These are a primary source of non-radiative losses and are exacerbated by poor crystallinity [7] [4].

Q2: Why does my high-quality perovskite film still suffer from VOC losses when integrated into a full device?

Even with a high-quality bulk perovskite layer, interfacial energy losses can dominate. This is often due to:

- Energy-Level Mismatch (Band Misalignment): An unfavorable energy offset at the perovskite/charge transport layer interface (e.g., with C60) creates a barrier, hindering charge extraction and promoting interfacial recombination [8].

- Interface-Induced Trap States: The first monolayer of the charge transport layer (like C60) can directly introduce deep trap states at the interface through energy-level pinning, severely increasing non-radiative recombination [8]. Mitigating this requires precise interface engineering, not just bulk optimization.

Q3: What is the advantage of using a dual-ligand or multifunctional passivation strategy over a single ligand?

A single ligand is often monofunctional, addressing only one type of defect (e.g., a Lewis base only passivates Pb²⁺ vacancies). A dual or multifunctional strategy provides a synergistic effect [8] [6]:

- Comprehensive Passivation: It can simultaneously passivate both anionic and cationic defects (e.g., Lewis acid and base groups in one molecule).

- Multi-Faceted Improvement: Beyond chemical passivation, it can improve interfacial band alignment via molecular dipole moments, enhance solvent compatibility for processing, and induce beneficial ferroelectric effects [8] [6]. This holistic approach is more effective in closing the VOC deficit.

Q4: How can I experimentally distinguish between bulk and surface non-radiative recombination?

You can use the following diagnostic experiments:

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Measure the PL decay lifetime. A longer lifetime generally indicates suppressed non-radiative recombination. Comparing films with and without a surface passivator can isolate surface effects [8].

- Thickness-Dependent Studies: Measure PLQY or device VOC as a function of perovskite film thickness. If losses are dominated by surfaces, thinner films will show disproportionately lower performance.

- Surface-Sensitive Techniques: Use techniques like grazing-incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD) and atomic force microscopy-based infrared (AFM-IR) spectroscopy to directly probe surface crystallinity and chemistry [8].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Dual-Ligand Synergistic Passivation for PQDs

This protocol is adapted from methods used to achieve near-unity PLQY by simultaneously suppressing bulk and surface defects [6].

1. Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs:

- Prepare a PbBr₂ precursor solution by dissolving PbBr₂ (1 mmol) and Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (TOAB, 2 mmol) in a mixture of ODE (Octadecene), OA (Oleic Acid), and OAm (Oleylamine) at 120°C under inert atmosphere.

- Rapidly inject a pre-heated Cs-oleate solution into the PbBr₂ precursor with vigorous stirring.

- Quench the reaction after 30 seconds using an ice bath.

2. Dual-Ligand Passivation:

- Bulk Lattice Stabilization: Co-dope the synthesis solution with Europium acetylacetonate (Eu(acac)₃). The Eu³⁺ ions compensate for Pb²⁺ vacancies, while the acac ligands coordinate with unbound Br⁻ ions.

- Surface Passivation: Introduce Benzamide as a short-chain ligand for surface exchange. The electron-rich amide group coordinates with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites, and the π-conjugated ring enhances binding via π-π interactions.

- Purify the passivated PQDs by centrifugation and re-disperse in a non-polar solvent.

Expected Outcome: A significant increase in PLQY (up to 98.56% reported) and a shortened fluorescence lifetime (~69.89 ns), indicating suppressed non-radiative decay [6].

Protocol: Multifunctional Molecular Interface Engineering

This protocol describes post-treatment of a perovskite film to suppress interfacial non-radiative recombination, as demonstrated with cage-like diammonium chloride molecules [8].

1. Perovskite Film Fabrication:

- Deposit your wide-bandgap perovskite precursor solution (e.g., for a 1.68 eV bandgap) onto the substrate via spin-coating.

- Use an antisolvent quenching method to initiate crystallization and anneal the film to form a dense, polycrystalline layer.

2. Surface Post-Treatment:

- Prepare a solution of 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane chloride (DCl) in isopropanol at an optimized concentration (e.g., 0.4 mg mL⁻¹).

- Spin-coat the DCl solution directly onto the annealed perovskite film.

- Perform a mild thermal treatment (e.g., 70°C for 5 minutes) to facilitate the reaction and self-assembly of the molecule on the surface.

3. Mechanism of Action:

- The DCl molecule reacts with the perovskite surface, consuming residual PbI₂ and forming an in-plane oriented, phase-pure quasi-2D perovskite (n=3) capping layer.

- The cage-like diammonium cation, containing both Lewis acid (R₃NH⁺) and base (R₃N) groups, passivates both negative and positive charge traps.

- The molecular dipole and ferroelectric nature of the resulting layer uplifts the surface work function, improving band alignment and facilitating charge extraction at the interface with C60 [8].

Expected Outcome: Enhanced open-circuit voltage and fill factor in solar cells, leading to a higher power conversion efficiency. For a 1.68 eV perovskite, this treatment enabled a PCE of 22.6% and impressive operational stability in tandem cells [8].

Visualization of Defect Dynamics and Passivation

Defect-Induced Non-Radiative Pathways

Diagram Title: Defect-Mediated Non-Radiative Recombination

Multimodal Defect Passivation Strategy

Diagram Title: Multimodal Defect Passivation Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Suppressing Non-Radiative Recombination

| Reagent / Material | Function / Mechanism | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cage-like Diammonium Chloride (DCl) [8] | Multifunctional passivator; Lewis acid/base groups passivate opposite charges, induces ferroelectric quasi-2D layer for improved band alignment and charge extraction. | Interface engineering in inverted p-i-n perovskite solar cells, especially wide-bandgap cells for tandem applications. |

| Dual-Ligand System: Eu(acac)₃ & Benzamide [6] | Synergistic passivation; Eu(acac)₃ compensates bulk Pb²⁺ vacancies, Benzamide passivates surface Pb²⁺ sites via coordination. | Achieving high PLQY in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) for light-emitting applications and photolithography patterning. |

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) [4] | Surface ligand; strong affinity for halide anions, provides superior surface coverage and defect passivation compared to traditional OA/OAm ligands. | Enhancing the environmental stability and PLQY of lead-based and lead-free (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) perovskite quantum dots. |

| Uracil [9] | Molecular binder; strengthens grain boundaries and passivates defects via multiple hydrogen bonding interactions, improving mechanical and operational stability. | Fabrication of robust, high-efficiency perovskite solar cells with negligible hysteresis and enhanced long-term stability. |

| Guanabenz Acetate Salt [9] | Crystallization modifier; prevents perovskite hydration and suppresses both anion and cation vacancies, enabling high-quality film fabrication in ambient air. | Ambient-air processing of perovskite films, a critical step towards scalable and cost-effective industrial manufacturing. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) [4] | Inorganic precursor; hydrolyzes to form a dense, amorphous SiO₂ shell around PQDs, providing a robust barrier against environmental stressors (moisture, oxygen). | Long-term stabilization of PQDs for applications in electroluminescent devices and down-conversion layers in photovoltaics. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are Type-A and Type-B-HC blinking mechanisms in Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)?

A1: Blinking refers to the random, intermittent fluorescence (on/off switching) observed in single quantum dots. In the context of PQDs:

- Type-A Blinking is primarily driven by band-edge carrier trapping. In this mechanism, an electron or hole is temporarily captured by a shallow trap state near the conduction or valence band. This is a temporary, non-radiative process that causes short-lived "off" periods. The carrier can escape back to the core, leading to the recovery of fluorescence.

- Type-B-HC Blinking (Charge Carrier Blinking) is a more severe process linked to non-radiative Auger recombination [11]. This occurs when an exciton (electron-hole pair) recombines and transfers its energy to a third charge carrier (an extra electron or hole) instead of emitting a photon. The presence of this additional charge, often due to ionization or trapping at a deep defect, enables this efficient non-radiative pathway, causing sustained "off" states [11].

Q2: How does non-radiative recombination relate to blinking and overall device performance?

A2: Non-radiative recombination is the core physical process behind quantum dot blinking and efficiency losses [12] [7]. When carriers recombine without emitting light, their energy is lost as heat. In blinking, this process turns the QD "off." At an ensemble level in devices like solar cells or LEDs, high rates of non-radiative recombination directly lower the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), open-circuit voltage (VOC), and overall power conversion efficiency [7]. Suppressing these pathways is therefore critical for both stabilizing emission and enhancing device performance.

Q3: What experimental techniques are used to distinguish between these blinking types?

A3: The primary method is single-dot time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopy.

- Type-A (Trapping): Manifests as short-lived "off" periods. Correlation analysis between fluorescence intensity and lifetime can show a slight reduction in lifetime during "on" periods due to the presence of shallow traps.

- Type-B-HC (Auger): Manifests as long-lived "off" periods. A key signature is a near-complete quenching of the PL lifetime during the "off" state because Auger recombination is an extremely fast non-radiative process.

Q4: What are the primary causes of non-radiative recombination in PQDs?

A4: The dominant causes are defects within the crystal structure and on the surface of the QDs [12] [7].

- Surface Defects: Incomplete surface passivation leads to "dangling bonds" that create trap states within the bandgap [11]. These states act as efficient centers for non-radiative Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination.

- Internal/Bulk Defects: Halide vacancies (e.g., Iodine vacancies), interstitials, and antisite defects can create deep-level traps [12]. Research on CsPbBr3-xIx QDs has shown that increasing iodine content introduces more defects, which shortens the carrier lifetime and enhances non-radiative pathways [12].

- Grain Boundaries: In perovskite films, boundaries between crystal grains are hotspots for defect-assisted recombination [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Dominant Non-Radiative Recombination

Problem: Low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and short average carrier lifetime in your PQD ensemble, indicating prevalent non-radiative pathways.

Investigation Protocol:

| Step | Action | Measurement/Tool | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perform Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) | Streak camera or fast detector [12]. Fit decay to multi-exponential model. | A fast decay component (τ₁) indicates strong non-radiative (defect-assisted) recombination. A dominant slow component (τ₂) indicates radiative, band-to-band recombination is more prevalent [12]. |

| 2 | Measure PLQY | Integrating sphere with calibrated spectrometer. | PLQY = (Radiative Recombination / Total Recombination). A low PLQY (<10%) signifies that non-radiative paths dominate the decay process [13]. |

| 3 | Correlate with Composition | Elemental analysis (EDS, XPS) and XRD. | Check for stoichiometric imbalances (e.g., PbI2 residue) [12]. Increased defect concentration is often linked to specific precursor incorporation. |

Solutions:

- Apply Surface Passivation: Use organic ligands (e.g., Oleic acid, Oleylamine) or inorganic shells (e.g., SiO2) to bind to unsaturated sites on the QD surface, neutralizing trap states [12]. For example, a SiO2 coating on CsPbBr3 PQDs was shown to increase the PL lifetime from 6.7 ns to 8.5 ns by passivating surface defects [12].

- Precise Compositional Engineering: Optimize precursor ratios and synthesis conditions to minimize the formation of halide vacancies and other intrinsic defects [7].

- Advanced Passivation Agents: Employ multifunctional molecules that can passivate multiple types of defects simultaneously. For instance, molecules with functional groups that bond to both positively and negatively charged defects [7].

Guide 2: Reducing Blinking (On/Off Intermittency) in Single PQDs

Problem: Your single-particle studies show strong blinking behavior, which is undesirable for applications requiring stable emission (e.g., single-photon sources).

Investigation Protocol:

| Step | Action | Measurement/Tool | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acquire Single-QD Intensity Traces | Confocal microscopy with single-QD isolation. | Analyze the on/off time distribution. Type-A blinking shows short off-times; Type-B-HC shows long off-times. |

| 2 | Perform Fluorescence Lifetime Correlation | Time-tagged, time-resolved (TTTR) detection. | Plot fluorescence lifetime vs. intensity. A lifetime that drops to nearly zero in the off state is a signature of Auger-dominated (Type-B-HC) blinking. |

| 3 | Test Under Different Atmospheres | Measure in inert (N2) vs. ambient air. | If blinking is suppressed in inert environments, it suggests surface oxidation or adsorption of atmospheric molecules is creating trap states. |

Solutions:

- Improve Shell/Passivation Quality: A thick, defect-free shell can physically separate charge carriers from the environment and suppress both trapping and Auger processes.

- Control the Electrostatic Environment: Embedding QDs in a charge-dissipating matrix can prevent the buildup of permanent charges that lead to Type-B-HC blinking.

- Ligand Engineering: Use ligands with stronger binding affinity or designed dipole moments to stabilize the QD surface and reduce the probability of charge ejection (ionization).

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research on recombination in perovskite quantum dots.

Table 1: Experimental Data on Recombination in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| PQD Material | PL Lifetime (ns) | Fast Lifetime, τf (ns) | Slow Lifetime, τs (ns) | Dominant Recombination Mechanism | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr3 [12] | - | - | - | - | Non-radiative recombination (τf) is the main mechanism at room temperature. |

| CsPbBr3 (Uncoated) [12] | 6.7 | - | - | - | Shorter lifetime indicates higher non-radiative recombination due to surface defects. |

| CsPbBr3@SiO2 (Coated) [12] | 8.5 | - | - | - | SiO2 coating passivates surface defects, reducing non-radiative pathways and increasing lifetime. |

| CsPbBr3-xIx (with PbI2) [12] | Gradual decrease with increasing I | - | - | Non-radiative | Incorporation of PbI2 increases defect concentration, enhancing non-radiative recombination. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for PQD Recombination and Blinking Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Lead Halide Precursors (e.g., Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, PbI₂) | Forms the inorganic perovskite crystal lattice (CsPbX₃) [12]. | Base material for creating PQDs with tunable bandgaps. Iodide incorporation is studied for bandgap tuning but can introduce defects [12]. |

| Surface Ligands (e.g., Oleic Acid, Oleylamine) | Organic molecules that coordinate with surface atoms during synthesis. | Prevent aggregation and passivate surface traps. Inadequate passivation is a primary source of non-radiative recombination and blinking [11]. |

| Silane Compounds (e.g., (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | Used for ligand exchange and surface functionalization [14]. | Enhances dispersibility in a siloxane matrix and improves atmospheric stability, mitigating surface-induced recombination [14]. |

| Halide Anion Salts | Source of halide ions (e.g., I⁻) for post-synthetic treatment. | Used for surface activation and defect healing, particularly to passivate halide vacancies [14]. |

| Passivation Molecules (e.g., Fullerene derivatives) | Molecules designed to bind specific defect sites. | Advanced passivation agents used at interfaces to suppress trap-assisted non-radiative recombination, a key strategy for improving solar cell efficiency [7]. |

Mechanism and Workflow Visualizations

Non-Radiative Recombination Pathways in PQDs

Experimental Workflow for Blinking Analysis

The Impact of Grain Boundaries and Surface Chemistry on Recombination Rates

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Do grain boundaries always dominate non-radiative recombination in perovskite films? No, this is not always the case. While some studies suggest grain boundaries (GBs) act as non-radiative recombination hotspots, particularly when they are accompanied by small, hidden grains [15], other research on high-quality, micrometer-sized perovskite films (e.g., MAPbI3) shows that recombination primarily occurs in non-grain boundary regions (grain surfaces or interiors) [16]. The role of GBs can depend on film quality and processing conditions. In some high-quality films, GBs do not show worse luminescence lifetimes compared to grain interiors, indicating they do not necessarily dominate recombination [16].

FAQ 2: How does surface ligand modification improve the performance of perovskite quantum dots? Surface ligand modification passivates surface defects, which are a major source of non-radiative recombination. Ligands such as trioctylphosphine (TOP), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), and l-phenylalanine (L-PHE) can coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the surface of CsPbI3 PQDs, effectively suppressing non-radiative recombination channels [17]. This leads to enhanced photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and improved environmental stability. For instance, studies have recorded PL enhancements of 3%, 16%, and 18% for L-PHE, TOP, and TOPO modifications, respectively [17].

FAQ 3: What is a synergistic bimolecular interface and how does it reduce recombination? A synergistic bimolecular interlayer (SBI) uses two different molecules to address multiple sources of loss at the perovskite interface. For example, one study used 4-methoxyphenylphosphonic acid (MPA) to form strong covalent P–O–Pb bonds with the perovskite surface, diminishing surface defect density [18]. A second molecule, 2-phenylethylammonium iodide (PEAI), was then added to create a negative surface dipole, which optimized the energy level alignment at the interface, enhancing electron extraction and further suppressing interface recombination [18]. This cooperative strategy led to a very small non-radiative recombination-induced open-circuit voltage (Voc) loss of only 59 mV in solar cells [18].

FAQ 4: Why is the hydrolysis of ester antisolvents important for perovskite quantum dot films? During the layer-by-layer deposition of PQD solid films for solar cells, ester antisolvents like methyl acetate (MeOAc) are used to rinse away the pristine long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleate, OA-). These esters hydrolyze under ambient moisture to generate shorter conductive ligands (e.g., acetate) that can cap the PQD surface, improving charge transfer between adjacent QDs [19]. However, this hydrolysis is often inefficient. Recent advances involve creating an alkaline environment during rinsing to make the hydrolysis reaction thermodynamically spontaneous and faster, leading to more effective ligand exchange, fewer trap states, and better device performance [19].

Performance Data of Defect-Passivation Strategies

The following table summarizes quantitative data on the effectiveness of various strategies for suppressing non-radiative recombination.

Table 1: Performance Enhancement via Surface and Interface Engineering

| Material/System | Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI3 PQDs | Ligand Passivation with L-PHE | Photoluminescence (PL) Enhancement | +3% | [17] |

| CsPbI3 PQDs | Ligand Passivation with TOP | Photoluminescence (PL) Enhancement | +16% | [17] |

| CsPbI3 PQDs | Ligand Passivation with TOPO | Photoluminescence (PL) Enhancement | +18% | [17] |

| Inverted p-i-n PSC | Synergistic Bimolecular Interlayer (MPA/PEAI) | Non-radiative Voc Loss | 59 mV | [18] |

| Inverted p-i-n PSC | Synergistic Bimolecular Interlayer (MPA/PEAI) | Stabilized Power Conversion Efficiency | 25.53% | [18] |

| Hybrid PQD Solar Cell | Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis | Certified Power Conversion Efficiency | 18.30% | [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Ligand Passivation of CsPbI3 Perovskite Quantum Dots

This protocol is adapted from a study on the effect of surface ligand modification on the optical properties of CsPbI3 PQDs [17].

- Synthesis of CsPbI3 PQDs: Use the hot-injection method. Heat a mixture of cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) and 1-octadecene (ODE) to 150°C under inert atmosphere. Separately, prepare a precursor solution of Lead (II) iodide (PbI₂) in ODE with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm). Rapidly inject the PbI₂ precursor into the Cs-ODE mixture at a controlled temperature (e.g., 170°C) with continuous stirring. Allow the reaction to proceed for a specific duration (e.g., 5-10 seconds) before cooling in an ice bath.

- Purification: Centrifuge the crude solution and precipitate the PQDs. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent like hexane.

- Ligand Exchange: To modify the surface ligands, introduce specific ligand modifiers such as trioctylphosphine (TOP), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), or l-phenylalanine (L-PHE) during the synthesis or in a post-synthetic treatment. The optimal hot-injection volume for enhancing PL intensity was found to be 1.5 mL in the cited study [17].

- Characterization: Analyze the optical properties by measuring UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra. Calculate the Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) to quantify the reduction in non-radiative recombination. Monitor the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the emission peak to assess the size distribution and purity of the PQDs.

Protocol 2: Constructing a Synergistic Bimolecular Interlayer (SBI) on Perovskite Films

This protocol is based on a study that developed a synergistic bimolecular interlayer for inverted perovskite solar cells [18].

- Perovskite Film Deposition: Deposit a high-quality perovskite thin film (e.g., Cs₀.₀₅(FA₀.₉₅MA₀.₀₅)₀.₉₅Pb(I₀.₉₅Br₀.₀₅)₃) onto your substrate using your standard method (e.g., spin-coating).

- MPA Surface Modification: Prepare a solution of 4-methoxyphenylphosphonic acid (MPA) in ethanol. Spin-coat this solution onto the freshly prepared perovskite film. The MPA will react with the surface, forming strong covalent P–O–Pb bonds with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, which passivates defects and upshifts the surface Fermi level.

- PEAI Deposition: Subsequently, deposit a layer of 2-phenylethylammonium iodide (PEAI) on top of the MPA-modified surface. The PEAI creates an additional negative surface dipole, which constructs a more n-type perovskite surface, enhancing electron extraction.

- Device Fabrication and Analysis: Complete the device by depositing the electron transport layer (e.g., PCBM) and other electrodes. Characterize the devices using current-voltage (J-V) measurements to determine the power conversion efficiency and Voc. Use techniques like ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) to confirm the shift in work function and valence band maximum.

Protocol 3: Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Rinsing for PQD Solid Films

This protocol details the alkali-augmented antisolvent hydrolysis (AAAH) strategy for improving the conductive capping on PQD surfaces [19].

- PQD Solid Film Preparation: Spin-coat a layer of hybrid FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs (or similar) from a colloidal solution to form a solid film.

- Prepare Alkaline Antisolvent: Add a carefully regulated amount of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to methyl benzoate (MeBz) to create the alkaline antisolvent. The alkaline environment facilitates the rapid hydrolysis of the ester, generating conductive ligands more efficiently than neat esters.

- Interlayer Rinsing: During the layer-by-layer film assembly, rinse the freshly deposited PQD solid film with the prepared alkaline MeBz antisolvent. This step substitutes the pristine long-chain insulating oleate (OA⁻) ligands with a higher density of hydrolyzed short conductive ligands.

- Post-Treatment and Completion: After achieving the desired film thickness, perform a standard post-treatment with a solution of short cationic ligands (e.g., formamidinium iodide) in a solvent like 2-pentanol to exchange the A-site cations. Complete the solar cell device with the deposition of charge transport layers and electrodes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Surface and Grain Boundary Engineering

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Surface ligand for CsPbI3 PQDs | Coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions to suppress non-radiative recombination. [17] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Surface ligand for CsPbI3 PQDs | Passivates surface defects; shown to provide 18% PL enhancement. [17] |

| l-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Surface ligand for CsPbI3 PQDs | Enhances photostability; retains >70% of initial PL after 20 days of UV exposure. [17] |

| 4-Methoxyphenylphosphonic Acid (MPA) | Covalent surface modifier for perovskite films | Forms strong P–O–Pb bonds, diminishing surface defect density and upshifting the Fermi level. [18] |

| 2-Phenylethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Surface dipole modifier | Creates a negative surface dipole for better energy level alignment, enhancing electron extraction. [18] |

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) | Ester-based antisolvent | Hydrolyzes to form conductive benzoate ligands for X-site ligand exchange during PQD film rinsing. [19] |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Alkaline additive for antisolvent | Facilitates spontaneous and rapid hydrolysis of ester antisolvents, improving ligand exchange efficiency. [19] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and mitigating non-radiative recombination, integrating the strategies discussed in the FAQs and protocols.

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting workflow for mitigating non-radiative recombination.

Correlating Surface Defect Density with Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) Loss

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental link between surface defect density and PLQY in Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs)?

Surface defects in PQDs, such as halide vacancies and under-coordinated lead ions, act as non-radiative recombination centers [1]. When a photoexcited charge carrier is captured by these trap states, its energy is dissipated as heat instead of light [7] [20]. PLQY measures the efficiency of light emission, and a higher density of these surface defects provides more pathways for non-radiative recombination, directly leading to a lower PLQY [1] [21].

What are the most common types of surface defects in PQDs?

The most prevalent and detrimental surface defects in all-inorganic PQDs like CsPbX3 are:

- Halide (X-site) Vacancies: These are easily formed and create deep trap states that significantly enhance non-radiative recombination [1] [20].

- Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ Ions: These occur at the crystal surface where the lead ion is not fully bonded to the surrounding halide lattice, creating electronic states within the bandgap that capture charge carriers [1].

How can we experimentally confirm that a treatment reduces surface defect density?

A combination of spectroscopic and material characterization techniques is used:

- Increase in PLQY: A direct rise in the absolute PLQY value is the most straightforward indicator of suppressed non-radiative recombination [1] [21].

- Prolonged Exciton Lifetime: Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) showing a longer average photoluminescence lifetime indicates that charge carriers are living longer because defect-mediated recombination has been reduced [1].

- Enhanced Crystallinity: X-ray diffraction (XRD) can show sharper peaks and reduced amorphous background, suggesting improved structural order and fewer defects [1].

Why is a high PLQY crucial for the performance of PQD-based solar cells?

A high PLQY is a direct indicator of low non-radiative recombination losses. In solar cells, these losses directly lower the open-circuit voltage (VOC) and the overall power conversion efficiency (PCE) [7] [20]. Suppressing non-radiative recombination via surface passivation is therefore essential for pushing the PCE of solar cells closer to their theoretical limits [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low or Inconsistent PLQY Measurements

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable Excitation Source | Check light source power output for fluctuations. | Use a stable laser or LED source and allow it to warm up before measurement [22]. |

| Improper Sample Preparation | Visually inspect sample for aggregation or precipitation. | Ensure sample concentration is optimal to avoid inner filter effects or concentration quenching [23] [22]. Use a blank substrate (e.g., uncoated glass) as a reference [24]. |

| Incorrect Instrument Calibration | Measure a standard sample with a known PLQY. | Regularly calibrate the system using calibrated standards or an integrating sphere with a certified reference [24] [23]. |

| Environmental Interference | Monitor laboratory temperature and ambient light. | Use temperature control and perform measurements in a dark environment to minimize signal noise [22]. |

Problem: Ineffective Surface Passivation

| Observation | Potential Reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No improvement in PLQY after passivation treatment. | Insulating ligands are hindering charge transport. | Employ ligand exchange strategies using shorter-chain or dual-functional ligands (e.g., DDAB) to balance passivation and conductivity [1] [20]. |

| PLQY improves initially but degrades rapidly over time. | Unstable passivation layer or ligand desorption. | Consider strategies that form a more robust passivation layer, such as the in-situ formation of a wide-bandgap shell (e.g., PbBr(OH)) [21]. |

| Severe aggregation of QDs during passivation. | Ligand collapse due to improper solvent or concentration. | Optimize the solvent polarity and ligand concentration during the post-synthesis treatment to maintain colloidal stability [1]. |

Quantitative Data on Defect Passivation and PLQY Recovery

The following table summarizes experimental data from recent studies demonstrating the correlation between surface passivation, reduced defect density, and recovered PLQY.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Surface Passivation Strategies on PLQY

| Passivation Method | Material System | Key Performance Metrics | Interpretation & Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Exchange with DDAB | CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs | PLQY: Increased significantly; TRPL: Prolonged exciton lifetime; Structural: Enhanced crystallinity, reduced QD size. | DDAB passivates under-coordinated Pb²⁺ and halide vacancies, suppressing non-radiative channels and improving charge transfer [1]. |

| Long-Term Air Exposure (4 years) | CsPbBr₃ QD Glass | Initial PLQY: ~20%; PLQY after 4 years: ~93%; Formation of a PbBr(OH) nano-phase confirmed. | Ambient moisture slowly drives a passivating PbBr(OH) layer on the QD surface, permanently curing surface defects and confining carriers [21]. |

| Co-passivation (DDAB & NaSCN) | CsPbBr₃ QDs | PLQY increased from 73% to nearly 100%. | A synergistic effect where DDAB and thiocyanate anions collectively passivate cationic and anionic surface defects, approaching ideal, defect-free emission [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: DDAB-Based Surface Passivation for CsPbX₃ QDs

This protocol outlines a post-synthetic ligand exchange strategy to suppress surface defects in mixed-halide PQDs, based on the method described by Mourya et al. [1]

Objective

To reduce surface defect density in CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs by treating with Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB), thereby enhancing PLQY and charge transfer efficiency.

Materials and Equipment

- Chemicals: Synthesized CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs (in non-polar solvent), DDAB, anhydrous toluene or hexane.

- Lab Equipment: Centrifuge, vortex mixer, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, fluorescence spectrometer (with integrating sphere for absolute PLQY), Time-Resolved PL (TRPL) spectrometer.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- QD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPb(Br₀.₈I₀.₂)₃ QDs via the standard hot-injection method using Oleic Acid (OA) and Oleylamine (OAm) as initial capping ligands [1].

- DDAB Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of DDAB in a dry, non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene) at a known concentration (e.g., 10 mg/mL).

- Ligand Exchange Reaction:

- Extract a precise volume of the purified QD solution.

- Add the DDAB solution dropwise to the QD solution under vigorous stirring. The typical ratio is 0.5-2.0 mg of DDAB per 1 mL of QD solution.

- Continue stirring the mixture for 10-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Purification: Precipitate the DDAB-treated QDs (DDAB-QDs) by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., methyl acetate) followed by centrifugation. Discard the supernatant.

- Redispersion: Redisperse the purified QD pellet in a suitable anhydrous solvent for further characterization and film fabrication.

Validation Measurements

- Absolute PLQY: Use an integrating sphere to measure the PLQY of the QD solution before and after DDAB treatment. A successful passivation will show a marked increase in PLQY [24] [23].

- TRPL: Measure the fluorescence decay kinetics. Effective passivation results in a longer average lifetime, indicating reduced non-radiative recombination [1].

- XRD: Perform X-ray diffraction to confirm that the treatment enhances crystallinity and does not induce phase impurities [1].

The logical relationship between surface defects, passivation, and their impact on PLQY and device performance is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Surface Defect Passivation in PQDs

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Consideration for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) | A halide-rich ligand used to passivate under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions and fill halide vacancies on the PQD surface [1]. | Using an optimal concentration is critical; excess DDAB can lead to colloidal instability and aggregation [1]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands used during synthesis for colloidal stability and initial surface termination [20]. | These are insulating and hinder charge transport in films; often require partial replacement with shorter ligands for device integration [1] [20]. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | A common precursor for perovskite synthesis. Also used in post-treatment to create a halide-rich environment and passivate halide vacancies [20]. | |

| Metal Halide Salts (e.g., ZnBr₂, CdBr₂) | Divalent metal ions can be used in hybrid passivation strategies to bind strongly to the perovskite surface, further reducing defect states [1]. | The ionic radius and bonding strength must be compatible with the perovskite lattice to avoid inducing strain [1]. |

| Anthraquinone (AQ) / Benzoquinone (BQ) | Model electron acceptor molecules used in quenching studies to quantitatively probe the charge transfer efficiency from passivated QDs [1]. | The strength of interaction (K_app) with QDs increases after effective passivation, indicating better charge extraction [1]. |

Surface Engineering Mastery: Cutting-Edge Passivation and Ligand Strategies

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Ligand-Related Issues in Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) Experiments

Table 1: Troubleshooting Poor PQD Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and Stability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low PLQY | High density of surface trap states due to incomplete ligand coverage or detachment [25] [26]. | • Increase ligand concentration during synthesis.• Use a combination of X-type and L-type ligands for more robust passivation [26].• Perform post-synthesis ligand exchange with shorter, conductive ligands [25]. |

| Poor Charge Transport in PQD Films | Long-chain insulating ligands (OA/OAm) create barriers between dots, impeding electronic coupling [25]. | • Conduct solid-state ligand exchange to replace long-chain ligands with shorter ones (e.g., formamidinium iodide, cesium acetate) [25].• Use additives like guanidinium thiocyanate to enhance dot-to-dot coupling [25]. |

| PQD Aggregation or Precipitation | Dynamic binding nature of OA/OAm leads to ligand detachment during purification or storage [25] [26]. | • Supplement with additional ligand (e.g., oleic acid) during washing steps [27].• Employ multidentate ligands (e.g., dicarboxylic acids) for stronger binding to the surface [26]. |

| Formation of Platelets or Layered Phases | Primary aliphatic amines (OAm) can compete with A-site cations, promoting 2D growth [27]. | • Adopt an amine-free synthesis route using trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) and oleic acid [27].• Precisely control the ratio of OA to OAm during synthesis [26]. |

| Poor Stability under Environmental Stress | Labile ligand shell allows penetration of moisture, oxygen, and polar solvents, degrading the ionic perovskite core [25] [26]. | • Implement in-situ ligand engineering with more stable molecules.• Apply interfacial passivation layers after film deposition [25]. |

FAQs: Ligand Engineering for Suppressing Non-Radiative Recombination

Q1: How do surface ligands directly help in suppressing non-radiative recombination in PQDs?

Surface defects on PQDs, such as lead or halide vacancies, act as trap states for charge carriers. When carriers are captured by these traps, they recombine without emitting light, which is known as non-radiative recombination. This process significantly reduces the efficiency of optoelectronic devices [7]. Ligands passivate these surface defects by coordinating with unsaturated lead atoms (via carboxylic or phosphonic groups) or by binding to halide ions (via amine groups), effectively removing the trap states and suppressing non-radiative pathways [25] [26].

Q2: The standard OA and OAm ligands are dynamic and insulating. What are the main ligand engineering strategies to overcome these issues?

The primary strategies are [25]:

- In-situ Ligand Engineering: Modifying the ligand shell during the synthesis of PQDs by introducing alternative ligands or adjusting ratios.

- Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange: Replacing the original long-chain insulating ligands after synthesis with shorter, more conductive molecules in solution or the solid state.

- Interfacial Engineering: Depositing a passivating layer on top of the pre-formed PQD film to stabilize the surface and improve charge injection/extraction.

Q3: Why is the TOPO (phosphine oxide) route considered advantageous for ligand engineering?

The TOPO route, which uses trioctylphosphine oxide with a protic acid like oleic acid and avoids aliphatic amines, offers several key benefits [27]:

- High Yield: Conversion of precursors to nanocrystals is close to the theoretical limit.

- Shape Homogeneity: It produces only cube-shaped nanocrystals without contamination from platelets or layered phases, a common issue with amine-based syntheses.

- Simple Ligand Shell: The resulting NCs are passivated primarily by Cs-oleate, simplifying the surface chemistry, unlike the complex acid-amine ligand compositions in traditional methods.

Q4: What types of ligands are used beyond OA and OAm to improve stability and performance?

Ligands can be classified by their binding mechanism. Common alternatives include [26]:

- X-type Ligands: Bind through an anionic group (e.g., carboxylate, sulfonate). Oleic acid is a common example.

- L-type Ligands: Donate electrons through a neutral group (e.g., alkyl amines, phosphine oxides). Oleylamine and TOPO fall into this category.

- Multidentate Ligands: Molecules with multiple binding groups (e.g., dicarboxylic acids, dendrimers) that form stronger, chelating interactions with the PQD surface, reducing ligand detachment.

- Zwitterionic Ligands: Molecules containing both positive and negative charges that can simultaneously passivate both anionic and cationic surface sites.

Experimental Protocols for Key Ligand Engineering Techniques

Protocol 1: Amine-Free Synthesis of CsPbBr3 Nanocrystals Using TOPO

This protocol outlines the synthesis of CsPbBr3 nanocubes using trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) and oleic acid (OA), avoiding the use of oleylamine [27].

Materials:

- Lead(II) bromide (PbBr2)

- Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3)

- Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO)

- Oleic Acid (OA)

- 1-Octadecene (ODE)

- Toluene

- Acetone

Procedure:

- Preparation of Cs-Oleate Precursor: Degas Cs2CO3 and OA in ODE in a three-neck flask under vacuum at 100°C for 1 hour. Then, react under nitrogen at 140°C until the solution becomes clear and colorless. Store in a glovebox.

- Preparation of PbBr2/TOPO/OA Precursor: Heat PbBr2 (60 mg, 0.16 mmol), TOPO (1.0 g, 2.59 mmol), and OA (400 μL, 1.27 mmol) in ODE (5.0 mL) to 100°C with stirring until a clear solution is obtained.

- Reaction and Injection: Set the temperature of the Pb-precursor solution to the desired reaction temperature (between 25°C and 140°C). Rapidly inject the preheated Cs-oleate solution (1.0 mL) into the reaction vial.

- Quenching and Purification: Allow the reaction to proceed for 30 seconds, then immediately cool the vial in an ice bath to stop nanocrystal growth. Centrifuge the reaction mixture and redisperse the nanocrystal pellet in toluene.

- Washing: To wash the NC dispersion, add acetone (2:1 volume ratio to NC solution) and centrifuge. Discard the supernatant. To maintain optimal surface coverage, redisperse the pellet in toluene with the addition of 5 μL of oleic acid per 1 mL of original NC dispersion. Repeat washing if necessary.

Protocol 2: Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange for Enhanced Charge Transport

This general protocol describes replacing long-chain insulating ligands with shorter organic or inorganic salts to improve electronic coupling in PQD solids [25].

Materials:

- PQDs capped with OA/OAm in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene, hexanes).

- Ligand exchange solution (e.g., formamidinium iodide in butanol, ammonium thiocyanate in methanol).

- Polar solvent for washing (e.g., ethyl acetate, methyl acetate).

- Centrifuge tubes.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Isolate the pristine PQDs via centrifugation and redisperse them in a minimal amount of non-polar solvent.

- Ligand Exchange: Add the ligand exchange solution to the PQD dispersion dropwise under vigorous stirring. The polar solvent helps dissociate the original ligands, while the new ligands in the solution bind to the freshly exposed surface sites.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to stir for a predetermined time (typically several minutes to an hour) to ensure complete exchange.

- Purification: Precipitate the ligand-exchanged PQDs by adding a polar anti-solvent and centrifuging. Carefully decant the supernatant, which contains the displaced ligands.

- Washing and Redispersion: Wash the pellet multiple times with a polar anti-solvent to remove any residual unbound ligands. Finally, redisperse the PQDs in a suitable solvent for film deposition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Ligands and Reagents in PQD Research

| Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | An X-type ligand. The carboxylate group chelates with unsaturated Pb²⁺ atoms on the PQD surface, suppressing lead-related trap states and preventing aggregation [25] [26]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | An L-type ligand. The amine group can bind to halide ions on the PQD surface via hydrogen bonding, helping to passivate halide vacancies. It also aids in precursor solvation [25] [26]. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | An L-type ligand used in amine-free syntheses. The P=O group coordinates with Pb²⁺, modulating precursor reactivity and enabling high-yield, shape-pure nanocube synthesis [27]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide | A short organic salt used in post-synthesis ligand exchange. It replaces long-chain OA/OAm, improving inter-dot charge transport and passivating surface defects [25]. |

| Zwitterionic Molecules | Ligands containing both positive and negative charges. They can simultaneously passivate both anionic and cationic surface sites with high binding affinity, enhancing stability against moisture and light [26]. |

| Multidentate Ligands | Ligands with multiple binding groups (e.g., dicarboxylic acids, dendrimers). They provide chelating effects for stronger, more stable attachment to the PQD surface, reducing ligand loss over time [26]. |

Ligand Engineering Pathways for PQD Optimization

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow and strategic decision-making process for employing ligand engineering to suppress non-radiative recombination in PQDs.

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Synergistic Hybrid-Ligand Passivation. This resource is designed for researchers and scientists working to suppress non-radiative recombination at perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces by implementing the combined phenethylammonium iodide (PEAI) and triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) ligand system. The following troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols will assist you in optimizing this advanced passivation technique to enhance the optoelectronic performance and environmental stability of your CsPbI₃-PQD devices.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: After ligand exchange with PEAI, my CsPbI₃-PQD films show reduced photoluminescence (PL) intensity and poor stability. What is the root cause?

A: This is a documented issue where PEAI, while essential for replacing insulating long-chain ligands, can induce the formation of reduced-dimensional perovskites (RDPs). Due to its large ionic radius, the PEA⁺ cation acts as an organic spacer. Initially, high-n RDPs (n > 2) may form, but these are unstable and undergo a detrimental phase transition to low-n RDPs over time. This phase transition is a primary cause of structural and optical degradation, leading to increased non-radiative recombination pathways and reduced PL intensity [28].

Q2: How does the addition of TPPO resolve the problems associated with PEAI?

A: TPPO acts as an ancillary covalent ligand that addresses the core limitations of PEAI through a multi-functional mechanism:

- Suppresses Low-n RDP Formation: TPPO regulates the rapid diffusion of PEAI molecules, thereby stabilizing the structure and suppressing the undesirable phase transition to low-n RDPs [28].

- Passivates Surface Traps: The TPPO molecule is a Lewis base that strongly coordinates with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface. This direct passivation neutralizes these common trap states, significantly reducing non-radiative recombination [29] [28].

- Enhances Ambient Stability: The TPPO ligand layer helps prevent the penetration of destructive H₂O molecules into the PQD solid, thereby improving the long-term stability of the film [28].

Q3: Why is it critical to dissolve TPPO in a nonpolar solvent like octane for post-treatment?

A: The ionic surface of CsPbI₃ PQDs is highly sensitive to polar solvents (e.g., methyl acetate, ethyl acetate) commonly used in conventional ligand exchange. These polar solvents can strip away not only the intended ligands but also metal cations and halides from the PQD surface, creating new uncoordinated sites and surface traps [29]. Using a nonpolar solvent like octane allows for the delivery of TPPO ligands while completely preserving the PQD surface components, preventing the introduction of new defects during the passivation process [29].

Q4: My PQD solar cell efficiency is lower than expected. How can I verify if the hybrid-ligand passivation is working correctly?

A: To diagnose the effectiveness of your passivation strategy, characterize your films with these techniques:

- Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy: A significant increase in PL intensity and PL lifetime after TPPO treatment indicates successful passivation of non-radiative recombination centers [29].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: Use FT-IR to confirm the removal of long-chain OA/OLA ligands and the successful binding of TPPO to the PQD surface [29].

- Device Performance Metrics: Ultimately, fabricate a solar cell and check for an increase in open-circuit voltage (VOC) and fill factor (FF), as these are directly benefited by reduced recombination. A properly executed hybrid-ligand process should lead to a notable improvement in power conversion efficiency (PCE) [29] [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Two-Step Ligand Exchange Procedure

This protocol forms the foundation for creating conductive PQD solids prior to hybrid-ligand passivation [29].

Objective: To replace insulating oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) ligands with short-chain ionic ligands, enabling efficient charge transport in CsPbI₃ PQD solids.

Materials:

- Synthesized OA/OLA-capped CsPbI₃ PQDs in toluene

- Methyl Acetate (MeOAc)

- Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc)

- Sodium Acetate (NaOAc)

- Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI)

- Anti-solvent (e.g., Anhydrous Toluene)

Methodology:

- Anionic Ligand Exchange:

- Prepare a ligand solution by dissolving NaOAc in MeOAc.

- Spin-coat a layer of OA/OLA-capped CsPbI₃ PQDs onto your substrate.

- While the film is still wet, drip-drop the NaOAc/MeOAc solution onto the film and spin to replace OA ligands with acetate ions.

- Wash with a small amount of anti-solvent to remove by-products and repeat this layer-by-layer process until the desired film thickness is achieved.

- Cationic Ligand Exchange:

- Prepare a ligand solution by dissolving PEAI in EtOAc.

- Post-treat the acetate-capped PQD solid film with the PEAI/EtOAc solution to replace residual OLA ligands with PEA⁺ cations.

- Wash gently with anti-solvent to complete the process.

Hybrid-Ligand Passivation Protocol with TPPO

This is the key stabilization step that mitigates the issues caused by the standard PEAI exchange [29] [28].

Objective: To passivate uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites and suppress phase degradation using TPPO dissolved in a nonpolar solvent, thereby enhancing optoelectronic properties and stability.

Materials:

- Ligand-exchanged CsPbI₃ PQD solids (from Protocol 3.1)

- Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO)

- Anhydrous Octane (nonpolar solvent)

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a TPPO solution by dissolving TPPO powder in anhydrous octane. Ensure the solution is fully dissolved and clear.

- Film Treatment: Spin-coat the TPPO/octane solution directly onto the ligand-exchanged CsPbI₃ PQD solid film.

- Annealing: Subject the treated film to a mild thermal annealing process (e.g., 60-70°C for 5-10 minutes) to facilitate strong Lewis-base coordination between TPPO and the uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface.

- The stabilized PQD film is now ready for the deposition of subsequent charge transport layers and electrode fabrication.

The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved with the hybrid-ligand passivation strategy, as reported in the literature, providing benchmarks for your experiments.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CsPbI₃ PQD Devices with Different Ligand Treatments

| Ligand System | Device Type | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Control Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEAI + TPPO (in Octane) | Solar Cell | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 15.4% | Lower than 15.4% (Control: PEAI only) | [29] |

| PEAI + TPPO | Solar Cell | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 15.3% | Not explicitly stated | [28] |

| PEAI + TPPO | Light-Emitting Diode | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 21.8% | Not explicitly stated | [28] |

| PEAI + TPPO (in Octane) | Solar Cell | Operational Stability (T80) | >90% initial PCE after 18 days in ambient | Lower stability (Control: PEAI only) | [29] |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists the essential materials required for the synergistic hybrid-ligand passivation technique.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Hybrid-Ligand Passivation

| Reagent | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) | The core photovoltaic/light-emitting material; the subject of surface passivation. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Ionic short-chain ligand used to replace insulating oleylamine (OLA), improving charge transport but potentially inducing RDPs. |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Covalent short-chain Lewis base ligand that passivates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites and suppresses PEAI-induced RDP formation. |

| Sodium Acetate (NaOAc) | Ionic short-chain ligand used to replace insulating oleic acid (OA) during the initial anionic ligand exchange. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar solvent for dissolving and delivering NaOAc during the anionic ligand exchange step. |

| Ethyl Acetate (EtOAc) | Polar solvent for dissolving and delivering PEAI during the cationic ligand exchange step. |

| Octane | Nonpolar solvent for dissolving TPPO; critical for preserving the PQD surface chemistry during the final passivation step. |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the procedural workflow for fabricating stable CsPbI₃ PQD films using the synergistic hybrid-ligand strategy.

Diagram 1: Hybrid-Ligand Passivation Experimental Workflow

This diagram details the molecular-level mechanism of the hybrid-ligand passivation process on the PQD surface.

Diagram 2: Molecular Mechanism of Surface Passivation and Stabilization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does shell encapsulation specifically help in suppressing non-radiative recombination in perovskite quantum dots (PQDs)? Non-radiative recombination occurs when charge carriers (electrons and holes) recombine without emitting light, primarily through defects and trap states on the PQD surface. Shell encapsulation addresses this by:

- Passivating Surface Defects: The encapsulating shell coordinates with undercoordinated lead (Pb²⁺) ions on the PQD surface, which are common sites for trap states. This coordination saturates these bonds, reducing the number of available sites for non-radiative recombination [17].

- Providing a Physical Barrier: The shell acts as a protective layer, shielding the PQD core from environmental factors like moisture and oxygen, which can create additional surface defects and degradation pathways that increase non-radiative losses [12] [17].

Q2: What are the key advantages of using Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) over other porous matrices for encapsulation? COFs offer a unique combination of properties that make them excellent host matrices:

- High Crystallinity and Ordered Porosity: Their predictable and uniform pore structures allow for precise encapsulation and potential size-selective applications [30] [31].

- Exceptional Stability: COFs exhibit high thermal and chemical stability, maintaining their structure under harsh conditions, unlike some metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [31] [32].

- Design Flexibility: Their structure can be tuned at the molecular level by choosing different building blocks, allowing for customization of pore size, surface functionality, and optical properties to suit specific needs [33] [31].

Q3: My core-shell structured COF nanocomposites are agglomerating. How can I improve their dispersion? Agglomeration is a common challenge. A highly effective strategy is the dual-ligand assistant encapsulation method [33].

- Method: Sequentially adhere polyethyleneimine (PEI) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) onto the surface of your core nanoparticles before COF synthesis.

- Function: These dual ligands work synergistically to control the nucleation and growth kinetics of the COF shell on the nanoparticle surface. This results in very uniform core@shell structures with minimal agglomeration, making the nanocomposites solution-processable [33].

Q4: Can I synthesize COF shells at room temperature? Yes, room temperature synthesis is possible and beneficial for sensitive substrates or precursors. The room temperature vapor-assisted conversion method is a proven approach [34].

- Protocol: A precursor solution is drop-cast onto a substrate, which is then placed in a sealed desiccator along with a small vessel containing a solvent mixture (e.g., mesitylene/dioxane). The vapor from the solvent vessel promotes the condensation reaction and crystallization of the COF over 24-72 hours at room temperature, producing high-quality, crystalline films [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) after Encapsulation

A low PLQY indicates persistent non-radiative recombination pathways.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Solution and Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual PLQY drop after encapsulation | Incomplete surface coverage leaving defects unpassivated | Optimize shell growth parameters (precursor concentration, reaction time). Use TEM to verify core-shell morphology and uniformity [30] [33]. |

| Immediate PLQY drop post-encapsulation | Lattice mismatch or chemical incompatibility causing new interface defects | Choose a shell material with a compatible crystal structure and lattice constant. Perform XPS to check for unwanted chemical interactions at the interface [35]. |

| High initial PLQY that degrades quickly | Poor shell stability allowing environmental degradation | Implement a more robust and dense shell. Perform stability tests under continuous illumination (e.g., UV exposure) and monitor PL intensity over time [17]. |

Recommended Workflow:

Issue 2: Poor Stability of Encapsulated PQDs under Operating Conditions

Instability can manifest as phase segregation, PL quenching, or structural degradation.

| Stability Challenge | Mechanism | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Instability (e.g., CsPbI3 transitioning from black to yellow phase) | [36] [35] | Employ halide alloying (e.g., CsPbIxBr3−x) or cation substitution to stabilize the desired perovskite phase [36] [35]. |

| Interfacial Degradation | Ion migration and reactions at the core-shell interface under heat/light. | Apply advanced surface passivation using Lewis base small molecules (e.g., 6TIC-4F) or polymers before shell growth to pacify the interface [36] [37]. |

| Environmental Degradation (Moisture/Oxygen) | Permeation of H2O and O2 through the shell, attacking the PQD core. | Utilize multi-shell structures or thicker, denser oxide coatings (e.g., SiO2) as a final protective layer [35] [17]. |

Recommended Workflow:

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solvothermal Synthesis of Core-Shell CuO@TAPB-DMTP-COF

This protocol is adapted for creating a composite where a metal oxide core enhances charge transfer while the COF shell provides a large, ordered surface area [30].

- Materials: CuO nanorods, 1,3,5-tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene (TAPB), 2,5-dimethoxyterephaldehyde (DMTP), 1,4-dioxane, butanol, mesitylene, acetic acid.

- Procedure:

- Pre-dispersion: Disperse the pre-synthesized CuO nanorods in a mixed solvent of 1,4-dioxane and butanol.

- Monomer Addition: Add stoichiometric amounts of TAPB and DMTP monomers to the dispersion.

- Solvothermal Reaction: Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 120°C for 72 hours to form the crystalline COF shell around the CuO cores.

- Purification: Collect the resulting core-shell composites by centrifugation and wash thoroughly with ethanol and tetrahydrofuran to remove unreacted monomers.

- Characterization: Use TEM/SEM to confirm core-shell morphology. Verify crystallinity with XRD and chemical structure with FTIR (looking for the C=N stretch at ~1618 cm⁻¹) [30].

Protocol 2: Surface Ligand Passivation of CsPbI3 PQDs

This passivation step is crucial prior to full shell encapsulation to directly suppress non-radiative surface recombination [17].

- Materials: CsPbI3 PQDs, Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), Trioctylphosphine (TOP), 1-Octadecene.

- Procedure:

- Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbI3 PQDs using the standard hot-injection method at an optimal temperature of 170°C [17].

- Ligand Exchange: Purify the PQDs and re-disperse them in a solution containing TOPO or TOP (e.g., 0.2 mL in 10 mL octadecene).

- Reaction: Stir the mixture at 80-100°C for 1-2 hours to allow the phosphine oxide groups to coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface.

- Purification: Precipitate and centrifuge the passivated PQDs to remove excess ligands.

- Verification: Measure Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL). Successful passivation is indicated by a significant increase in both PLQY and carrier lifetime, as TOPO passivation has been shown to enhance PL by up to 18% [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Encapsulation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Lewis base surface ligand for PQDs; passivates Pb²⁺ defects to reduce non-radiative recombination [17]. | High-temperature stability; can increase PLQY by up to 18% [17]. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) & Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Dual ligands for interfacial growth; enable uniform, non-agglomerated core@shell COF nanostructures [33]. | Sequential adhesion is critical for controlling COF nucleation kinetics on diverse core surfaces [33]. |

| TAPB & DMTP Monomers | Building blocks for imine-linked COF shells; create highly porous, crystalline, and stable coating matrices [30] [33]. | Produce a COF with a large electroactive surface area that enhances adsorption of target molecules [30]. |

| Silane Coupling Agents (e.g., APTES) | Provides amine-functionalized surfaces on substrates/cores; essential for initiating subsequent COF growth or improving adhesion [32]. | Creates a covalent link between inorganic surfaces and organic coatings. |

| Mesitylene & Dioxane Solvent Mix | High-boiling point solvent for solvothermal COF synthesis; also used in vapor-assisted conversion to control crystallinity [30] [34]. | Optimal solvent composition (e.g., 1:1 v/v) is crucial for high crystallinity in vapor-assisted methods [34]. |

| Lead Halide (PbI2) & Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Standard precursors for the synthesis of all-inorganic CsPbX3 PQD cores [12] [17]. | Stoichiometric balance and purity are vital for controlling defect density during core synthesis. |

Table 1: Optical Performance Metrics of Encapsulated PQDs