Advanced Strategies for Reducing Trap Density in Perovskite Quantum Dot Films: From Synthesis to High-Performance Optoelectronics

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest strategies for minimizing trap density in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films, a critical challenge for enhancing the performance and stability of...

Advanced Strategies for Reducing Trap Density in Perovskite Quantum Dot Films: From Synthesis to High-Performance Optoelectronics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest strategies for minimizing trap density in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films, a critical challenge for enhancing the performance and stability of optoelectronic devices. Targeting researchers and scientists, we explore the fundamental origins of trap states, delve into advanced synthesis and surface engineering methodologies, and present optimization techniques for device integration. The discussion is supported by current research on characterization, performance validation, and comparative analysis of various passivation strategies, offering a holistic roadmap for developing high-efficiency, commercially viable PQD-based technologies.

Understanding Trap States: The Fundamental Challenge in Perovskite Quantum Dot Films

Within the broader thesis on reducing trap density in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films, this guide serves as a technical resource for researchers. Trap states, or energy levels within a material's bandgap, are defects that capture charge carriers [1]. Their density directly governs non-radiative recombination—a process where excited electrons lose their energy as heat (phonons) rather than light (photons) [2]. This guide addresses frequently asked questions and provides troubleshooting protocols to help you identify, quantify, and mitigate the detrimental effects of trap density in your experimental devices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What exactly is a "trap" in a semiconductor, and how does it cause non-radiative recombination?

A trap is an electronic state within the forbidden band gap of a semiconductor, created by defects such as atomic vacancies, impurities, or structural irregularities at the surface or in the bulk material [2] [1]. These states can capture charge carriers (electrons or holes).

Non-radiative recombination via traps often occurs through the Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) mechanism [2] [3]. In this two-step process:

- An electron from the conduction band is captured by an unoccupied trap state.

- Subsequently, a hole from the valence band is captured by this now-occupied trap state.

The energy released from this electron-hole annihilation is not emitted as light but is transferred to the crystal lattice as vibrational energy (heat) [2] [1]. This contrasts with radiative recombination, where the energy is released directly as a photon.

2. How does trap density directly impact the performance of my perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs)?

High trap density severely degrades device performance through several key mechanisms, all stemming from enhanced non-radiative recombination:

- Reduced Efficiency: Trap states act as pathways for non-radiative recombination, stealing charge carriers that would otherwise contribute to light emission. This directly lowers the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of your film and the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of your device [4] [5]. Research has shown that effective trap passivation can boost PLQY from 85.6% to over 97% [4] and EQE from 7.57% to over 20% [4].

- Slow Response Time: Charge carriers can become temporarily "trapped" and then released after a delay. This hinders the swift injection and transport of carriers needed for fast electroluminescence (EL) response. Defect-related trapping is a primary cause of slow rise times in PeLEDs [4]. Mitigating traps has been shown to reduce the EL rise time by over 75%, achieving nanosecond-scale response [4].

- Low Operational Stability: Trap sites are often associated with ionic defects and weakly bound surface ligands. Under electrical stress, these sites can act as initiation points for irreversible degradation, such as ion migration and ligand detachment, leading to rapid device failure [5].

3. Are all trap states equally effective at causing non-radiative recombination?

No. The effectiveness of a trap state as a recombination center depends on its energy position within the bandgap. The conventional view is that deep-level traps (located near the middle of the bandgap) are the most effective recombination centers because they can trap both electrons and holes with relative ease [6] [1]. However, recent first-principles studies have revealed novel mechanisms, such as the "two-level process," where a defect with relatively shallow levels can still cause strong non-radiative recombination by undergoing a rapid structural change between carrier capture events [6]. This can accelerate the recombination rate by orders of magnitude.

4. What are the primary origins of traps in perovskite quantum dot films?

Traps in PQDs primarily originate from two sources:

- Surface Defects: The high surface-to-volume ratio of QDs means a significant portion of atoms are on the surface. These atoms have dangling bonds and are often poorly passivated by organic ligands. Weakly bound or detached ligands create a high density of surface traps [5]. The insulating nature of long-chain ligands like oleic acid and oleylamine can also hinder charge injection, creating injection barriers that mimic trap-like effects [4] [5].

- Internal Lattice Defects: Due to the low ionic migration energy in perovskites, halide vacancies and other point defects can easily form within the crystal lattice itself, creating bulk trap states [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing High Non-Radiative Recombination in Device Operation

Problem: Your PeLED shows low efficiency, low brightness, and/or slow response time.

Investigation Procedure:

| Observation | Possible Cause | Next Steps to Confirm |

|---|---|---|

| Low EQE and PLQY | High defect-assisted non-radiative recombination [4] [5]. | Measure TRPL lifetime; a short amplitude-weighted average lifetime (τ_avg) indicates strong non-radiative decay. |

| Slow EL rise time | Carrier trapping and detrapping at defect sites hindering swift exciton formation [4]. | Perform transient EL measurement under pulsed voltage. A slow second-stage rise indicates trap-limited transport. |

| Rapid efficiency roll-off at high voltage | Trap-filled limit reached; or Auger recombination (a three-carrier non-radiative process) becoming dominant at high carrier densities [7]. | Analyze current density/EQE relationship. Auger is dominant at high carrier injection, while SRH is more prominent at low injection [2]. |

| Poor operational stability (fast decay) | Trap-assisted degradation and ion migration initiated from defect sites [5]. | Monitor EQE or luminance over time under constant current stress. Correlate decay rate with initial trap density. |

Guide 2: Quantitative Assessment of Trap Density

Accurately quantifying trap density is crucial for tracking your progress. The following table summarizes common techniques.

- Table: Experimental Methods for Trap Density Quantification

| Method | What It Measures | Key Output & How it Relates to Trap Density | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) | The current released as trapped charges are thermally excited. | A TSC Spectrum plotting current vs. temperature. Peak positions indicate trap energy depth; integrated charge gives trap density. |

Provides information on trap energy distribution. Can be complex to set up. |

| Space-Charge-Limited Current (SCLC) | Current in a defect-free semiconductor is limited by the injected space charge. | Current Density-Voltage (J-V) curve in log-log scale. A steep increase in slope (to ≥2) indicates the Trap-Filled Limit (TFL). The voltage at this kink (V_TFL) calculates trap density. |

Common and direct method for diode structures. Requires hole-only or electron-only devices. |

| Transient Photoluminescence (TRPL) | The rate of photoluminescence decay after a pulsed excitation. | A PL Decay Curve. Faster non-exponential decay suggests higher trap density. The lifetime (τ_avg) is inversely related to non-radiative recombination rate. |

Non-invasive, directly probes recombination dynamics. Does not give an absolute trap density number without modeling. |

Experimental Protocols for Trap Reduction

This section details a specific, recently published methodology that has proven highly effective in reducing trap density and enhancing device performance.

Protocol: Ionic Liquid Treatment for Enhanced Crystallinity and Surface Passivation

This protocol is based on the work of Kim et al., who used the ionic liquid [BMIM]OTF to significantly improve the properties of PQDs [4].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) Precursor | Source of Pb²⁺ and Br⁻ for the perovskite lattice. |

| Cesium Oleate | Source of Cs⁺ cations. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands for colloidal synthesis and initial surface stabilization. |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) | Ionic Liquid Additive. The [BMIM]+ cation coordinates with Br⁻ to slow nucleation, promoting larger crystal growth. The OTF⁻ anion strongly binds to Pb²⁺ surface sites, effectively passivating lead-related traps [4]. |

| Chlorobenzene (CB) | Solvent for the ionic liquid and for purification. |

2. Step-by-Step Methodology

- In-Situ Addition: Dissolve a controlled amount of [BMIM]OTF in chlorobenzene and add it directly to your PbBr₂ precursor solution before initiating the reaction with Cs-oleate [4].

- Nucleation and Growth: The [BMIM]+ ions will coordinate with the [PbBr₃]⁻ octahedra, sterically hindering and slowing the subsequent reaction with Cs⁺. This results in enhanced crystallinity and larger QD size (e.g., from ~8.8 nm to ~11.3 nm), which inherently lowers the surface-area-to-volume ratio and reduces the number of surface atoms requiring passivation [4].

- Purification and Film Formation: Proceed with standard purification steps using methyl acetate or butanol. Due to the stronger binding energy of OTF⁻ to Pb²⁺ (calculated -1.49 eV vs. -0.95 eV for oleate), the ionic liquid provides a robust passivation layer that resists detachment during purification, preserving a low-trap surface [4].

- Characterization Validation:

- XRD: Check for enhanced and sharper diffraction peaks, indicating improved crystallinity [4].

- TEM: Confirm an increase in average QD size and maintainance of good crystallinity [4].

- PLQY: Measure a significant increase (e.g., from 85.6% to 97.1%), confirming the reduction of non-radiative channels [4].

- TRPL: Observe a longer amplitude-weighted average lifetime (

τ_avg), e.g., an increase from 14.26 ns to 29.84 ns, directly indicating suppressed non-radiative recombination [4].

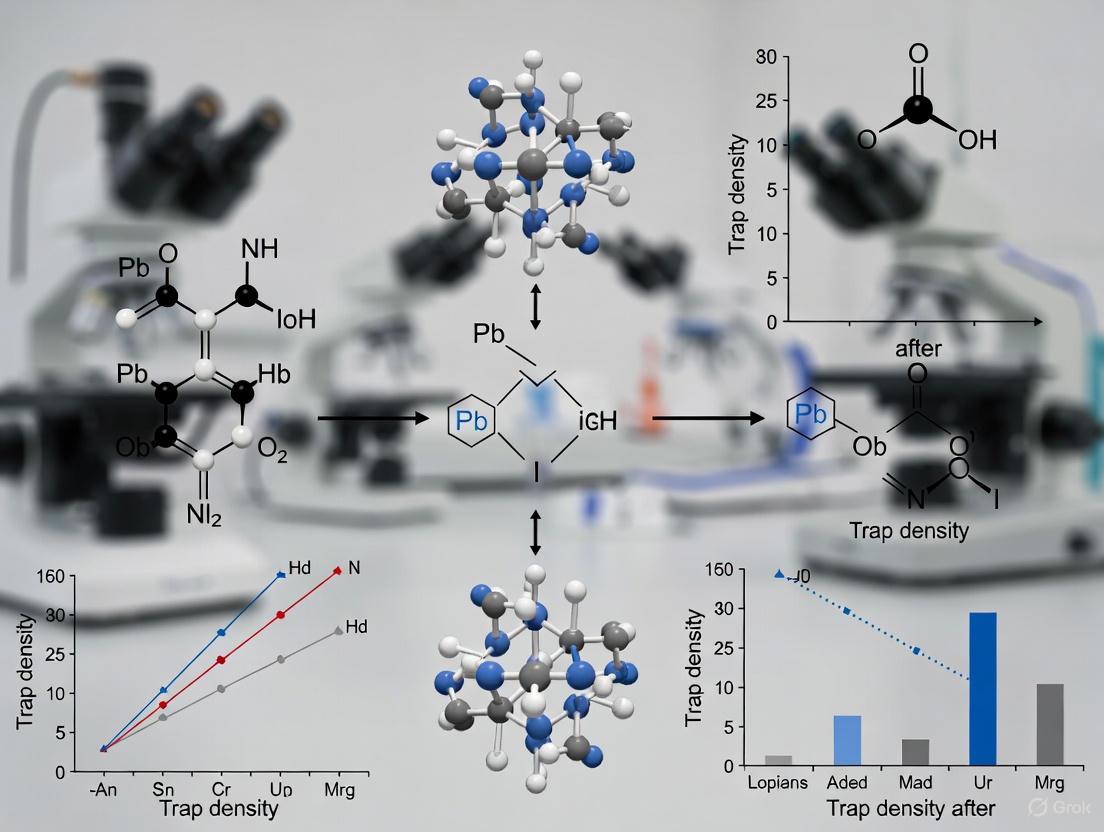

3. Workflow Visualization

The logical flow and mechanism of this experimental protocol are summarized in the diagram below.

Key Performance Metrics Table

The following table summarizes the typical performance enhancements you can expect from successful trap density reduction, based on cited research.

- Table: Expected Performance Gains from Effective Trap Passivation

| Metric | Before Passivation (Example) | After Passivation (Example) | Improvement Factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY (QDs Solution) | 85.6% | 97.1% | +13.4% | [4] |

TRPL Lifetime (τ_avg) |

14.26 ns | 29.84 ns | ~2.1x | [4] |

| EL Response Rise Time | ~2.8 µs | ~0.7 µs | ~75% reduction | [4] |

| Device EQE | 7.57% | 20.94% | ~2.8x | [4] |

| Device Operational Lifetime (T₅₀) | 8.62 h | 131.87 h | ~15.3x | [4] |

| Betavoltaic Cell VOC | 2.47 V | 2.07 V (with traps) | N/A (degradation) | [8] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary origins of trap states in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films? The main origins are the high surface-to-volume ratio of PQDs, which leads to a significant exposure of grain boundaries, and incomplete surface passivation by organic ligands [9]. During the essential ligand exchange process, the removal of long, insulating ligands introduces surface defects and can leave behind unpassivated sites, creating electronic traps that act as centers for non-radiative recombination [10].

2. Why do my PQD solar cells have a low open-circuit voltage (VOC), even when using high-purity materials? A low VOC is frequently a symptom of non-radiative recombination at trap states. Research shows that the ligand exchange process, while necessary for charge transport, can cause a dramatic 300-fold reduction in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), directly limiting the achievable VOC [10]. Trap states located approximately 150 meV below the conduction band have been identified as a key culprit [10].

3. How can I distinguish between bulk and surface defects in my films? Contactless spectroscopic techniques like absolute photoluminescence (PL) and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) are powerful tools for this. If the quasi-Fermi level splitting (QFLS) measured from a standalone PQD film is similar to that measured from a full device stack, it indicates that the VOC loss originates primarily from the absorber (PQD film) itself, not from the contact interfaces [10]. A short carrier lifetime in TRPL measurements further suggests a high density of defects within the film [10].

4. My PQD films have poor charge transport. Is this related to trap states? Yes, these issues are directly connected. Incomplete ligand coverage creates energetic disorder at the surfaces and grain boundaries, hindering the movement of charge carriers between QDs [9]. While a solid-state ligand exchange with compounds like lead nitrate in methyl acetate is required for conductivity, this process often creates new electronic traps if not optimized [10].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Excessive Non-Radiative Recombination

Symptoms: Low PLQY, short carrier lifetime in TRPL measurements, lower-than-expected VOC in solar cells. Underlying Cause: A high density of unpassivated surface defects, such as uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites and halide (I⁻) vacancies, which act as traps [10] [11]. Solutions:

- Implement Multi-Site Passivation: Use additive molecules that contain multiple functional groups to simultaneously passivate different defect types. For example, the molecule DBTT, which contains both Bromine (Br) and Sulfur (S) atoms, can passivate iodine vacancies (with Br) and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions (with S) [11].

- Employ Ionic Liquid Treatment: Incorporate ionic liquids like [BMIM]OTF during synthesis. The cations ([BMIM]⁺) and anions (OTF⁻) can coordinate with the QD surface, effectively suppressing the generation of surface defects and significantly improving PLQY [4].

- Optimize A-site Composition: Partially replacing Cs⁺ with formamidinium (FA⁺) has been shown to reduce trap density by up to a factor of 40 without altering the background carrier concentration [10].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Film Quality and Performance

Symptoms: Poor batch-to-batch reproducibility, varied emission properties, and fluctuating device performance. Underlying Cause: Incomplete conversion of precursors and inhomogeneous ligand coverage during synthesis [12]. Solutions:

- Improve Precursor Quality: Design a novel cesium precursor recipe using a combination of acetate (AcO⁻) and short-branched-chain ligands like 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA). Acetate can improve the purity of the cesium precursor from ~70% to over 98%, enhancing homogeneity [12].

- Use Strong-Binding Ligands: Replace oleic acid with ligands that have a stronger binding affinity to the QD surface, such as 2-HA. This provides more robust surface passivation and improves stability [12].

Problem 3: High Background Carrier Concentration

Symptoms: While sometimes beneficial for achieving a relatively high VOC, an excessively high and tunable background carrier concentration can be indicative of imperfect surface chemistry and is orders of magnitude higher than in perovskite thin films [10]. Underlying Cause: Specifics of the ligand chemistry and surface termination of the PQDs [10]. Solutions:

- Tune Ligand Chemistry: The background carrier concentration can be modulated by carefully adjusting the ligand exchange process, presenting an opportunity to tailor electronic properties [10].

- Characterize with TRPL: Use time-resolved photoluminescence to monitor the carrier dynamics and trap densities associated with different ligand treatments [10].

Table 1: Impact of Different Defect Passivation Strategies on PQD Optoelectronic Properties

| Strategy / Material | Key Performance Metrics (Before → After) | Identified Trap Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| A-site FA+ substitution [10] | Trap density reduced by up to a factor of 40. | Maintains background carrier concentration while reducing electronic traps. |

| Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF [4] | PLQY: 85.6% → 97.1%; Avg. exciton lifetime (τ_avg): 14.26 ns → 29.84 ns. | Stronger coordination to QD surface (Eb = -1.49 eV for OTF⁻) suppresses surface defect formation. |

| Multi-site additive DBTT [11] | Solar cell PCE: 20.39% → 23.02%; Stability: >91% of initial PCE after 1320 h in air. | Passivates I vacancy (V_I), uncoordinated Pb²⁺, and I-Pb antisite defects simultaneously. |

| Optimized Cs-precursor (AcO⁻ & 2-HA) [12] | PLQY: ~99%; ASE threshold: Reduced by 70% (1.8 μJ·cm⁻² → 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²). | Achieves uniform size distribution and passivates dangling bonds, suppressing Auger recombination. |

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Trap State Mitigation

| Reagent | Function / Role in Trap Reduction | Key Chemical Moieties / Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF [4] | Enhances crystallinity, reduces surface defects, and lowers charge injection barrier via coordination. | OTF⁻ anion (coordinates with Pb²⁺), [BMIM]⁺ cation (coordinates with Br⁻). |

| Multi-site Additive DBTT [11] | Collaborative passivation of multiple defect types (VI, uncoordinated Pb²⁺, IPb) in one molecule. | Br atoms (fill I vacancies), S atoms in thiophene groups (coordinate with Pb²⁺ and I). |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) [9] | Long-chain native ligands for initial synthesis and stabilization; provide initial passivation but inhibit charge transport. | Carboxylate group (R-COO⁻), Ammonium group (R-NH₃⁺). |

| Lead Nitrate / Methyl Acetate [10] | Standard solid-state ligand exchange solution to replace long ligands with shorter ones for better conductivity. | Often reduces PLQY significantly, introducing new traps if not optimized. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) [12] | Short-branched-chain ligand with stronger binding affinity than OA for superior defect passivation. | Carboxylate group with short, branched carbon chain. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Site Additive Passivation for Inverted Solar Cells

This protocol is adapted from the use of the DBTT additive to create high-quality, low-defect perovskite films [11].

Materials:

- Precursors: FAI, PbI₂, CsI, MABr, PbBr₂, MACl, etc., dissolved in a DMF/DMSO solvent mixture.

- Additive: 5,5″-Dibromo-2,2′:5′,2″-terthiophene (DBTT).

- Substrate: ITO/HTL (e.g., NiOx).

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Add a small, optimized molar percentage (e.g., 0.5-2.0%) of DBTT directly into the prepared perovskite precursor solution (e.g., Cs₀.₅(FA₀.₉₈MA₀.₀₂)₀.₉₅Pb(I₀.₈₅Br₀.₁₅)₃).

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat the DBTT-containing precursor solution onto the substrate.

- Crystallization and Annealing: During the thermal annealing step, the DBTT molecules migrate to the surface and grain boundaries of the perovskite crystals. The Br and S active sites interact with the perovskite lattice:

- Br atoms fill iodine vacancies (V_I).

- S atoms coordinate with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. These interactions suppress non-radiative recombination.

- Device Completion: Subsequently deposit the electron transport layer (e.g., PC₆₁BM) and top electrode (e.g., Ag) to complete the solar cell.

Protocol 2: Ionic Liquid Treatment for Enhanced PQD Crystallinity

This protocol describes an in-situ treatment for CsPbBr₃ QDs using [BMIM]OTF to achieve high crystallinity and low defect density [4].

Materials:

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂) precursor solution.

- Cesium (Cs⁺) precursor.

- Ionic liquid: 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF), dissolved in chlorobenzene.

Methodology:

- Additive Introduction: Add the [BMIM]OTF solution in varying concentrations (e.g., [BMIM]OTF-1, -2, -3) directly to the PbBr₂ precursor before QD synthesis.

- Nucleation and Growth: The [BMIM]⁺ and OTF⁻ ions coordinate with the [PbBr₃]⁻ octahedra, slowing the nucleation rate. This results in larger QDs with enhanced crystallinity and a lower surface-area-to-volume ratio, which intrinsically requires less ligand passivation.

- QD Synthesis: Inject the Cs⁺ precursor to initiate QD crystallization. The presence of [BMIM]OTF during growth leads to a denser and more defect-free film.

- Characterization: Confirm success via a red-shift in PL peak (e.g., 517 nm → 520 nm), an increase in average QD size (e.g., 8.84 nm → 11.34 nm), and a significant boost in PLQY and carrier lifetime.

Defect Passivation Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: A general workflow for diagnosing and addressing trap states in perovskite quantum dot films, outlining multiple strategic pathways.

Diagram 2: The relationship between common defect types in PQDs and the specific chemical groups or reagents used to passivate them.

This technical support center provides troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers using advanced characterization techniques to reduce trap density in perovskite quantum dot (PQD) films.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My XRD patterns for CsPbI₃ quantum dots show peak shifts and the emergence of new peaks at 25.4°, 25.8°, and 30.7° during in-situ heating. What does this indicate?

A1: The emergence of these specific peaks indicates a phase transition from the photoactive black γ-phase to a non-perovskite yellow δ-phase, a common thermal degradation pathway for Cs-rich PQDs [13]. The peak shifts often suggest changes in crystal lattice parameters, possibly due to ligand loss or A-cation migration.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm the Phase: Compare the new peak positions (25.4°, 25.8°, 30.7°) against reference patterns for the yellow orthorhombic δ-phase of CsPbI₃ [13].

- Check Experimental Conditions: Ensure the temperature during measurement does not exceed the stability threshold of your PQDs. FA-rich PQDs generally decompose directly to PbI₂ at high temperatures, while Cs-rich ones undergo this phase transition [13].

- Review Synthesis Parameters: The A-site cation composition (Cs/FA ratio) and surface ligand density significantly influence thermal stability. FA-rich compositions with stronger ligand binding exhibit higher thermal tolerance [13].

Q2: I am getting a very weak photoluminescence signal from my PQD film during TRPL measurements. What could be the cause and how can I improve this?

A2: A weak PL signal is often a sign of a high density of non-radiative recombination traps, frequently caused by surface defects.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Film Quality: Use SEM to check for film uniformity and the presence of pinholes or cracks that could quench luminescence [14].

- Optimize Passivation: Ensure effective surface passivation during synthesis. Inorganic halide perovskite QDs (e.g., CsPbX₃) are defect-tolerant, but surface ligands are critical for achieving high PL quantum yields (PLQY) above 95% [15].

- Control the Atmosphere: Perform measurements in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox). Exposure to oxygen and moisture can create surface traps that quench PL [13].

- Check Instrument Setup: Confirm the alignment of the excitation laser (e.g., 470 nm) and the collection optics. Ensure the detector sensitivity is set appropriately for the expected signal intensity [14].

Q3: When performing XPS depth profiling with argon ion sputtering on my PQD film, I notice changes in the Pb:I ratio. Are these changes real or an artefact?

A3: Changes in elemental ratios during ion sputtering can be real, but ion-induced artefacts are a major concern in XPS depth profiling [16].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Identify Preferential Sputtering: Halides like iodine are often preferentially sputtered over heavier elements like lead, leading to a non-stoichiometric surface and an artificially lowered I:Pb ratio [16].

- Mitigate Damage: Consider using cluster argon ion sources instead of monoatomic ions, as they cause less chemical damage and reduce preferential sputtering effects [16].

- Corroborate with Other Techniques: Use a non-destructive technique like XRD to check for the formation of metallic Pb⁰, which is a tell-tale sign of perovskite decomposition and would support the XPS findings [13].

Experimental Protocols for Defect Analysis in PQD Films

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) for Phase Purity and Stability

Objective: To identify crystal phases, detect unwanted impurity phases (e.g., PbI₂, non-perovskite phases), and monitor phase transitions under thermal stress.

Detailed Protocol:

- Instrument Setup: Use a diffractometer like the PANalytical X’pert PRO with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm). Configure the goniometer for a theta-2theta scan from 5° to 90° [14].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a uniform film of PQDs on a substrate such as glass or silicon. For in-situ heating studies, use a heating stage compatible with the diffractometer [13].

- Data Collection: Acquire data using software such as Malvern Panalytical's Data Collector, which stores data in the open XRDML format for easy processing and archiving [17].

- Data Analysis:

- Identify all diffraction peaks by matching them to crystallographic databases.

- The presence of a peak at 12.7° is a key indicator of PbI₂, suggesting decomposition [13].

- For Cs-rich PQDs, monitor for peaks at 25.4°, 25.8°, and 30.7°, which signify a transition to the non-perovskite yellow δ-phase [13].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) for Surface Composition and Chemical State

Objective: To determine the elemental composition and chemical bonding at the PQD surface (top ~10 nm) and identify surface defects or contaminants [18].

Detailed Protocol:

- Instrument Setup: Use a system like the Kratos Axis Supra with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). A charge neutralizer is essential for insulating PQD films [14].

- Sample Preparation: Transfer films directly from an inert atmosphere glovebox to the XPS load lock without air exposure to prevent surface oxidation.

- Data Collection:

- Acquire a survey spectrum to identify all elements present (except H and He).

- Collect high-resolution spectra for core levels like Pb 4f, I 3d, Cs 3d/4d, and N 1s (if FA is present).

- Data Analysis:

- Use software (e.g., CasaXPS) for peak fitting. Reference the C 1s peak (adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV) for binding energy calibration.

- Chemical State Identification: A shift in the Pb 4f peak to lower binding energy can indicate the formation of metallic Pb⁰, a deep-level trap state [18].

- Depth Profiling: If using ion sputtering, be aware of artefacts. Cluster ion sources provide more reliable depth profiles for halide perovskites [16].

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) for Carrier Dynamics and Trap Density

Objective: To measure the charge carrier lifetime, which is directly influenced by trap-mediated non-radiative recombination.

Detailed Protocol:

- Instrument Setup: Use a spectrofluorometer like the Horiba Fluorolog FL-3 equipped with a pulsed laser (e.g., 470 nm) and time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) detector [14].

- Sample Preparation: Use a pristine, uniform PQD film on a transparent substrate.

- Data Collection: Measure the photoluminescence decay at the peak emission wavelength. Perform the measurement in the dark and in an inert environment to exclude effects of photobleaching and environmental degradation.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the decay curve to a multi-exponential function: ( I(t) = A + B1e^{-t/τ1} + B2e^{-t/τ2} + ... )

- The amplitude-weighted average lifetime (( \tau{avg} )) is a key metric. A shorter ( \tau{avg} ) typically indicates a higher density of non-radiative recombination centers (traps) [14].

- Correlate longer TRPL lifetimes with higher PLQY for films with lower trap density [13].

Table 1: Characteristic Defect Signatures Identified by XRD, XPS, and TRPL in PQD Films

| Technique | Direct Output | Indicator of Low Defect Density | Indicator of High Defect Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRD | Phase identification, Crystallinity | Sharp peaks only for the perovskite phase [13]. | Presence of PbI₂ (peak at ~12.7°) or δ-phase (peaks at ~25.4°, 25.8°) [13]. |

| XPS | Surface elemental composition & chemical state | Stoichiometric Pb:I ratio, absence of metallic Pb⁰ peak [18]. | Non-stoichiometric surface, presence of Pb⁰ (shifted Pb 4f peak) [18]. |

| TRPL | Carrier lifetime | Long, multi-exponential decay; high amplitude-weighted average lifetime (( \tau_{avg} )) [14] [13]. | Short, fast decay; low amplitude-weighted average lifetime (( \tau_{avg} )) [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Synthesis and Stabilization of Low-Trap-Density PQD Films

| Material / Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Defect Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precarbonate (e.g., Cs₂CO₃) | A-site cation source for all-inorganic CsPbX₃ QDs [15]. | High purity ensures stoichiometric composition, minimizing vacancy defects. |

| Formamidinium Halide (e.g., FAI) | A-site cation source for hybrid FAPbX₃ QDs [13]. | Stabilizes the black perovskite phase; FA-rich compositions can enhance ligand binding [13]. |

| Lead Halides (PbX₂) | B-site and X-site source for the [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedron [15]. | Purification to remove metallic impurities is critical to prevent deep-level traps. |

| Oleic Acid & Oleylamine | Surface ligands and capping agents during synthesis [13]. | Passivate under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites; optimal balance and concentration are vital for full surface coverage and high PLQY [15] [13]. |

| Solid-state Electrolyte | Removable top contact for solid-state electrochemical defect quantification [19]. | Enables operando quantification of defect density and energetics without solvent damage [19]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for characterizing defects in perovskite quantum dot films.

Defect Characterization Workflow in PQD Films

Defect tolerance is a critical enabling property of lead halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) that distinguishes them from many other semiconductor materials. It indicates a relative insensitivity of the material's functional properties to defects, meaning that even in the presence of crystallographic imperfections, the material can maintain robust optoelectronic performance [20]. This does not equate to defect immunity, but rather that defects primarily form within the valence or conduction bands rather than within the band gap, thus avoiding the creation of states that lead to non-radiative recombination [20]. The remarkable defect tolerance of perovskite crystals explains their excellent performance in optoelectronic applications despite the presence of intrinsic point defects that would normally deteriorate performance in conventional semiconductors [20].

The structural properties of PQDs directly influence how trap states form and affect carrier dynamics. In defect-tolerant materials like CsPbI3, dominant iodide vacancies form shallow traps (approximately 0.278 eV from the conduction band minimum) that have minimal impact on carrier recombination, whereas in wider-bandgap systems like CsPbBr3, defects create deeper traps (approximately 0.666 eV from the conduction band minimum) that significantly accelerate non-radiative recombination [21]. This fundamental relationship between structural composition, trap depth, and electronic properties forms the core of the defect-tolerance paradigm in perovskite quantum dots.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Defect Tolerance

Q1: What exactly does "defect-tolerant" mean for perovskite quantum dots? Defect tolerance indicates that the functional optoelectronic properties of perovskite quantum dots, such as carrier lifetime and mobility, are relatively insensitive to the presence of crystallographic defects [20]. This occurs because defects in these materials primarily form within the valence or conduction bands rather than creating mid-gap states that would normally serve as non-radiative recombination centers [20]. However, defect tolerance does not mean defects are completely harmless—they can still influence hot carrier cooling dynamics and long-term stability [21].

Q2: How do structural properties affect trap state formation? The composition and crystal structure directly determine trap formation and characteristics. Iodide-based perovskites like CsPbI3 tend to form shallow traps (≈0.278 eV) due to iodide vacancies, while bromide-based systems like CsPbBr3 form deeper traps (≈0.666 eV) [21]. Shallow traps have minimal effect on cold carriers but can still influence hot carrier cooling dynamics. The unique electronic structure of lead halide perovskites, with their antibonding character at the valence band maximum, contributes to this defect-tolerant behavior [21].

Q3: Why is my PQD film exhibiting batch-to-batch variability in performance? Batch-to-batch inconsistencies often stem from variations in precursor purity and conversion efficiency during synthesis. Incomplete conversion of cesium salt (as low as 70.26% purity in non-optimized synthesis) leads to by-product formation and defective QDs [22]. Implementing a dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) precursor system can increase cesium precursor purity to 98.59% with significantly improved reproducibility [22]. Standardizing purification protocols and controlling ligand chemistry are also critical for reducing variability.

Q4: How does defect tolerance extend to hot carriers? Recent research demonstrates that hot carrier defect tolerance is not universal but correlates strongly with cold carrier defect tolerance. In CsPbI3 with shallow traps, hot carriers exhibit longer lifetimes, while in CsPbBr3 with deeper traps, hot carrier cooling accelerates significantly [21]. Hot carriers can be directly captured by traps without going through intermediate cold carrier states, with deeper traps causing faster hot carrier cooling [21].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Poor Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Problem: Low PLQY in perovskite quantum dot films, typically below 80%.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Cause 1: High surface defect density from insufficient passivation.

- Solution: Implement pseudohalogen engineering using ionic liquids like 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) to simultaneously etch lead-rich surfaces and passivate defects [4] [23]. This approach can increase PLQY from 85.6% to 97.1% [4].

- Protocol: Add [BMIM]OTF dissolved in chlorobenzene to lead bromide precursor during synthesis. The optimal concentration should be determined through systematic variation (e.g., [BMIM]OTF-1 to [BMIM]OTF-3) [4].

- Cause 2: Incomplete precursor conversion leading to impurity phases.

- Solution: Optimize cesium precursor recipe using dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as short-branched-chain ligand [22].

- Protocol: Combine AcO⁻ (which acts as both reaction modifier and surface ligand) with 2-HA (which exhibits stronger binding affinity toward QDs compared to oleic acid) in precursor preparation [22].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Defect Passivation Strategies on PQD Performance

| Passivation Strategy | PLQY Improvement | Defect Reduction Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| [BMIM]OTF Ionic Liquid | 85.6% → 97.1% | Enhanced crystallinity, reduced surface area ratio, coordination with QD surface | [4] |

| AcO⁻ + 2-HA Ligand System | Significant improvement to ~99% | Complete precursor conversion, surface dangling bond passivation | [22] |

| 2D-MoS2 Interface Layer | Improved Voc and FF | Reduced trap density, mitigated interfacial losses, prompt charge extraction | [24] |

| Multiple Antisolvent Purification | Controlled intentional defect introduction | Increased surface halide vacancies for controlled studies | [21] |

Slow Electroluminescence Response Time

Problem: Slow rise in electroluminescence (EL) response hindering high refresh rate display applications.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Cause: Hindered charge injection and massive charge trapping due to insulating and defective surface of QDs [4].

- Solution: Enhance interface quality and reduce capacitance effects.

- Interface Engineering: Use [BMIM]OTF treatment to reduce defect state density and injection barrier at the interface, decreasing EL rise time by over 75% [4].

- Device Architecture: Reduce light-emitting unit area to further decrease capacitance effects. Fabricate ultra-high resolution (9072 PPI) PeLEDs with 1.3 μm pixel size to achieve 700 ns response time [4].

- Protocol: Apply ionic liquid treatment during QD synthesis, then implement photolithographic patterning for sub-micron pixel fabrication.

Instability Under Ambient Conditions

Problem: Rapid degradation of PQD films when exposed to air and moisture.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Cause: The ionic crystal structure of PQDs is highly susceptible to degradation from polar molecules like water, which hydrate the ionic lattice and cause structural breakdown [25].

- Solution: Implement comprehensive encapsulation and surface stabilization strategies.

- Hydrophobic Capping: Develop core-shell structures with protective layers.

- Surface Ligand Engineering: Employ long-chain hydrophobic ligands and cross-linkable surface moieties [23].

- Protocol: Utilize pseudohalogen inorganic ligands in acetonitrile for post-treatment to simultaneously etch lead-rich surfaces and passivate defects in-situ, producing PQDs with suppressed halide migration [23].

Key Experimental Protocols for Defect Characterization and Mitigation

Purpose: Systematically investigate defect tolerance mechanisms by controllably introducing defects.

Methodology:

- Synthesize colloidally stable CsPbX₃ (X = Br, I) NCs by hot-injection method [21].

- Purify multiple times using low-polarity antisolvent methyl acetate to partially remove surface ligands and halides.

- Characterize defect density after each purification step using:

- Correlate defect density with optoelectronic properties through PLQY, time-resolved PL, and femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy.

Expected Outcomes: Controlled increase in defect density as evidenced by decreased PLQY and PL lifetime in CsPbBr₃ and mixed-halide perovskites, while CsPbI₃ maintains high performance due to shallow traps [21].

Protocol: Hot Carrier Dynamics Analysis

Purpose: Determine how defects influence hot carrier cooling dynamics.

Methodology:

- Prepare perovskite NC samples with varying defect densities using the intentional defect introduction protocol.

- Perform femtosecond pump-probe (PP) and pump-push-probe (PPP) transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy.

- Conduct excitation-energy-dependent PLQY measurements with excess energy up to ~1 eV above bandgap.

- Analyze data using kinetic modeling to extract hot carrier trapping rates and cooling dynamics.

- Correlate findings with DFT-calculated trap depths for different compositions.

Expected Outcomes: Demonstration that hot carrier lifetime is governed by both defect density and energy, with protection of hot carriers in narrow-bandgap perovskite NCs with shallow traps compared to wide-gap NCs [21].

Table 2: Defect-Dependent Performance Metrics in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Material System | Trap Depth from CBM (eV) | PLQY Change with Defects | Hot Carrier Cooling Impact | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ | 0.278 | Minimal decrease | Shallow traps preserve HC lifetime | Photovoltaics, LEDs [21] |

| CsPbBrₓI₃₋ₓ | 0.513 | Moderate decrease | Intermediate HC lifetime reduction | Tunable LEDs [21] |

| CsPbBr₃ | 0.666 | Significant decrease | Deep traps accelerate HC cooling | Green LEDs, Lasers [21] |

| CsPbBr₃ (AcO⁻ optimized) | Not specified | High (99% PLQY) | Not measured | Low-threshold lasers (ASE threshold: 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Defect Engineering in PQDs

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) | Ionic liquid for enhancing crystallinity and reducing surface defects | Interface engineering in PeLEDs | 75% reduction in EL rise time, EQE from 7.57% to 20.94% [4] |

| Dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) | Cesium precursor optimization and surface passivation | Improving reproducibility in CsPbBr₃ QD synthesis | Increases precursor purity from 70.26% to 98.59%, enables 99% PLQY [22] |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain ligand with strong binding affinity | Surface defect passivation in synthesis | Suppresses biexciton Auger recombination, reduces ASE threshold by 70% [22] |

| 2D-MoS₂ flakes | Hole extraction interlayer | Interface engineering in perovskite solar cells | Increases PCE from 15.05% to 18.54%, reduces trap density [24] |

| Methyl acetate | Antisolvent for controlled defect introduction | Purification and defect density control | Enables systematic studies of defect impact on carrier dynamics [21] |

Visualization of Defect Tolerance Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

Defect Tolerance Mechanism in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Experimental Workflow for Defect Analysis and Mitigation

The defect-tolerance paradigm in perovskite quantum dots represents a fundamental shift in how we approach semiconductor defects, moving from complete elimination to strategic management. The structural properties of PQDs—particularly their composition-dependent trap depths—directly govern both cold and hot carrier dynamics, with shallow traps in iodide-rich systems providing the most favorable defect tolerance [21]. The experimental protocols and troubleshooting guides presented here provide researchers with practical methodologies for characterizing and mitigating defects in PQD systems.

Future research directions should focus on extending defect tolerance to mixed compositions and lead-free alternatives, understanding the dynamic behavior of defects under operational conditions, and developing standardized characterization protocols for defect density assessment across different laboratories. The integration of machine learning approaches with high-throughput experimentation shows particular promise for accelerating the discovery of novel defect-passivation strategies and optimizing synthesis parameters for enhanced reproducibility and performance [26]. As these fundamental relationships between structural properties and trap formation become better understood, the design of next-generation perovskite quantum dots with tailored defect properties will enable unprecedented performance in optoelectronic applications ranging from displays and photovoltaics to quantum information processing.

Synthesis and Passivation: Methodologies for Low-Defect High-Quality PQD Films

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) have emerged as promising materials for optoelectronic applications due to their exceptional properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and defect tolerance. [27] [28] However, their inherent ionic nature and dynamic surface chemistry make them susceptible to environmental degradation and surface defect formation, which significantly increases trap-assisted non-radiative recombination. [27] [29] This trap density issue represents a critical challenge for both device performance and long-term stability.

Surface ligand engineering has proven to be an indispensable strategy for suppressing surface defects and enhancing the optoelectronic properties of PQDs. [30] [28] Traditional long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) exhibit highly dynamic binding and facile detachment from PQD surfaces, creating vacancies that act as trap states. [27] [30] This review examines advanced ligand engineering approaches, focusing specifically on short-chain and multifunctional ligands that provide robust passivation to minimize trap density in perovskite quantum dot films.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are traditional ligands like OA and OAm insufficient for effective long-term passivation?

OA and OAm ligands exhibit highly dynamic binding characteristics and reversible proton transfer (OA⁻ + OAmH⁺ ⇋ OAM + OA, OAmH⁺ + X⁻ ⇋ OAM + HX), leading to easy ligand desorption from the PQD surface. [30] This dynamic equilibrium creates surface defects and trap states that quench photoluminescence and reduce stability. [30] [28] Additionally, their long hydrocarbon chains act as insulating barriers, impeding inter-dot charge transport in films. [31] [28]

Q2: What are the key advantages of short-chain ligands over conventional long-chain ligands?

Short-chain ligands provide stronger binding affinity, reduced interparticle distance, and enhanced electronic coupling between quantum dots. [32] [31] Studies demonstrate that replacing oleic acid with short-chain succinic acid (SA) significantly improves fluorescence intensity and stability due to tighter ligand binding. [32] Furthermore, shorter ligands facilitate closer packing of PQDs in films, establishing stronger tunnel coupling for more efficient charge transport. [31]

Q3: How do multidentate ligands enhance passivation effectiveness compared to monodentate ligands?

Multidentate ligands feature multiple binding sites that coordinate simultaneously with surface atoms, creating a chelate effect that significantly enhances binding affinity and stability. [32] [30] For instance, N-Hydroxy succinimide (NHS) can act as a multidentate ligand with donor atoms (N and O) that provide stronger coordination to Pb²⁺ sites. [32] This multidentate approach reduces ligand detachment and more effectively passivates surface defects compared to monodentate ligands like OA. [32]

Q4: What specific surface defects do these engineered ligands target?

Different ligand types target distinct surface defects. X-type carboxylate ligands (e.g., OA, SA) bind to and passivate undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites (lead vacancies). [30] [33] L-type ligands (e.g., OAm, phosphines) donate electron density to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites. [27] [28] Multidentate ligands can simultaneously address multiple defect types, while halide-based ligands (e.g., from ammonium salts) help passivate halide vacancies. [30] [34]

Q5: How can researchers verify successful ligand exchange and improved passivation?

Multiple characterization techniques can confirm effective ligand exchange:

- FTIR and NMR spectroscopy: Identify chemical states and binding of new ligands. [35]

- Photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY): Measure defect reduction through enhanced emission efficiency. [30]

- Density functional theory (DFT) calculations: Quantify binding energies between ligands and PQD surfaces. [30]

- GISAXS: Analyze packing density and interparticle spacing in films. [31]

- Transient absorption/emission spectroscopy: Monitor trap-assisted recombination dynamics. [29]

Ligand Classification and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Classification of Ligand Types for Perovskite Quantum Dot Passivation

| Ligand Type | Binding Mechanism | Key Advantages | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain Carboxylic Acids | Coordinate to Pb²⁺ sites (X-type) | Reduced interparticle distance; Enhanced charge transport | Succinic acid (SA), [32] 2-hexyldecanoic acid (DA) [33] |

| Multidentate Ligands | Multiple coordination sites (chelate effect) | Stronger binding affinity; Improved stability in aqueous media | EDTA, NHS-activated SA, [32] THAB [30] |

| Zwitterionic Ligands | Simultaneous cationic and anionic binding | Balanced surface coverage; Enhanced defect passivation | Iminodibenzoic acid, [32] Phosphocholine [30] |

| Perovskite-like Ligands | Ionic coordination similar to perovskite structure | Lattice matching; Effective defect passivation | (BA)₂PbI₄, [34] MAPbI₃ [34] |

| Short-chain Ammonium Salts | Hydrogen bonding with halide anions | Halide vacancy passivation; Improved crystallinity | THAB, [30] Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide [30] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Engineered Ligand Systems

| Ligand System | PLQY (%) | Binding Energy (eV) | Stability Improvement | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Succinic Acid (SA) + NHS | "Very high PL" (specific value not reported) | Not specified | Significant improvement in water stability | Bioconjugation; Biosensing [32] |

| THAB | 61 | -2.779 | Superior stability against UV, heat, and polar solvents | Light-emitting diodes [30] |

| 2-hexyldecanoic Acid (DA) on CsPb₁₋ₓNiₓBr₃ | 84.71 | Not specified | Enhanced stability under ambient, thermal, and moisture conditions | General optoelectronics [33] |

| SHS | Not specified | -2.320 | Moderate stability enhancement | Reference for comparison [30] |

| Binary Mixed PQD Films | Not specified | Not specified | Improved packing density (37.1% volume fraction) | Solar cells [31] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Poor Quantum Yield After Ligand Exchange

- Potential Cause: Incomplete removal of native ligands or insufficient binding of new ligands.

- Solution: Optimize ligand concentration and reaction time. For SA ligand exchange, ensure thorough purification to remove residual OA/OAm before introducing new ligands. [32] Implement successive purification steps with antisolvent precipitation.

- Prevention: Characterize intermediate products with FTIR to confirm complete ligand exchange. [35]

Problem: Rapid Degradation in Aqueous Environments

- Potential Cause: Weak ligand binding or insufficient surface coverage.

- Solution: Employ multidentate ligands with stronger coordination. NHS activation of SA PQDs forms stable esters that resist hydrolysis and enable bioconjugation while maintaining high PL in water. [32]

- Prevention: Incorporate hydrophobic groups in ligand design. BA⁺-rich surfaces from (BA)₂PbI₄ ligands provide excellent hydrophobicity for enhanced moisture stability. [34]

Problem: Poor Charge Transport in PQD Films

- Potential Cause: Excessive interparticle spacing from long-chain ligands or incomplete ligand exchange.

- Solution: Use short-chain ligands like SA or implement binary mixing of different PQD sizes. [32] [31] Binary mixing of 14nm and 10nm PQDs increases packing density to 37.1% volume fraction, reducing interparticle distance from ~5.8nm to ~3.7nm. [31]

- Prevention: Combine ligand exchange with post-treatment strategies such as solid-state ligand exchange or matrix engineering.

Problem: Ligand-Induced PQD Aggregation During Exchange

- Potential Cause: Too rapid ligand exchange or improper solvent selection.

- Solution: Implement phase-transfer methods with controlled mixing rates. For (BA)₂PbI₄ ligand exchange, use DMF/octane biphasic system with ammonium acetate as colloidal stabilizer. [34]

- Prevention: Maintain appropriate concentration ratios and temperature control throughout the process.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Batches

- Potential Cause: Variations in precursor ratios or reaction conditions.

- Solution: Standardize ligand precursor preparation. For THAB-capped PQDs, precise control of ligand concentration during synthesis is critical for reproducible binding energy and PLQY. [30]

- Prevention: Strictly control reactant purity, moisture levels, and reaction atmosphere (N₂ glovebox).

Experimental Protocols for Key Ligand Engineering Approaches

Principle: Replace long-chain oleic acid (OA) with short-chain dicarboxylic acid succinic acid (SA) for stronger binding and improved electronic coupling.

Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ PQDs synthesized via hot-injection method

- Succinic acid (≥99%)

- Toluene (99.8%) and ethyl acetate (99.8%)

- N-Hydroxy succinimide (98%, for subsequent activation)

Procedure:

- Purify pristine OA-capped CsPbBr₃ PQDs by precipitation with ethyl acetate and centrifugation at 9500 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Redisperse PQD pellet in anhydrous toluene to achieve concentrated stock solution.

- Prepare SA solution in toluene (concentration range: 0.1-1.0 mg/mL).

- Add SA solution dropwise to PQD solution under vigorous stirring at room temperature.

- React for 1-2 hours with continuous stirring.

- Precipitate with ethyl acetate and centrifuge at 9500 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Redisperse purified SA-PQDs in desired solvent for characterization or further processing.

- For NHS activation: React SA-PQDs with NHS in aqueous medium to form multidentate ligand system.

Characterization:

- UV-Vis and PL spectroscopy: Confirm retention of optical properties with increased absorption and PL intensity.

- FTIR: Verify replacement of OA signatures with SA characteristic peaks.

- TEM: Monitor morphological changes and particle size distribution.

Principle: Employ hexadecyltrimethylammonium tetrafluoroborate (THAB) as bifunctional X-type ligand for strong binding and defect passivation.

Materials:

- PbBr₂ (99.999%), CsBr (99.9%)

- Hexadecyltrimethylammonium tetrafluoroborate (THAB, 98%)

- Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.5%), toluene, and methanol

- 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), oleylamine (OAm, 70%)

Procedure:

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ NCs via ligand-assisted reprecipitation method.

- Dissolve PbBr₂ and CsBr in DMF with THAB ligand (typical molar ratio: Pb:Cs:THAB = 1:1:0.5-2).

- Stir precursor solution at 60°C until completely clear.

- Quickly inject precursor solution into poor solvent (toluene) under vigorous stirring.

- Centrifuge crude solution at 6000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate large aggregates.

- Collect supernatant containing THAB-capped CsPbBr₃ NCs.

- Further purify by precipitation with methanol and centrifugation at 9500 rpm for 5 minutes.

Characterization:

- PLQY measurement: Quantify improvement in emission efficiency (typically ~61% for THAB).

- DFT calculations: Determine binding energy (typically -2.779 eV for THAB).

- Stability testing: Evaluate resistance to UV light, heat, and polar solvents.

Principle: Utilize differently sized PQDs (10nm and 14nm) to increase packing density and reduce trap-assisted recombination.

Materials:

- Two batches of CsPbI₃ PQDs with different sizes (excitonic peaks at 662nm and 688nm)

- Toluene or hexane for dispersion

- Ethyl acetate for purification

Procedure:

- Synthesize two size populations of CsPbI₃ PQDs via hot-injection at different temperatures (120°C and 170°C).

- Separate and purify each population through standard precipitation/centrifugation.

- Determine concentration of each PQD batch through absorbance measurements.

- Mix PQDs at optimal number ratio (0.64:0.36 for 14nm:10nm QDs).

- Form films by spin-coating binary mixture at 1000 rpm for 10s followed by 2000 rpm for 7s.

- Characterize packing density through GISAXS measurements.

Characterization:

- GISAXS: Quantify volume fraction and packing efficiency.

- GIWAXS: Confirm crystalline structure maintenance.

- Transport measurements: Evaluate carrier lifetime and trap density reduction.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ligand Engineering Experiments

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Key Properties | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Succinic Acid (SA) | Short-chain bidentate ligand | Dicarboxylic acid; Strong binding to Pb²⁺ sites [32] | Surface engineering for water-compatible QDs [32] |

| N-Hydroxy succinimide (NHS) | Multidentate ligand activator | Forms NHS ester for bioconjugation; Strong chelation [32] | Biomolecule conjugation; Enhanced aqueous stability [32] |

| THAB | Bifunctional X-type ligand | Quaternary ammonium salt; High binding energy (-2.779 eV) [30] | High PLQY (61%) and stability for LED applications [30] |

| 2-hexyldecanoic acid (DA) | Branched carboxylic acid ligand | Steric hindrance; Enhanced surface coverage [33] | Nickel-doped CsPbBr₃ QDs with 84.71% QY [33] |

| (BA)₂PbI₄ | 2D perovskite-like ligand | Layered structure; Hydrophobic BA⁺ cations [34] | Infrared photovoltaics; Enhanced ambient stability [34] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Reference long-chain ligand | Monodentate carboxylate binding; Dynamic equilibrium [30] | Baseline for comparison; Standard synthesis [30] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Reference long-chain amine ligand | L-type donor; Charge compensation [35] | Baseline for comparison; Standard synthesis [35] |

Visualization of Ligand Engineering Concepts

Ligand Exchange Workflow for Trap Reduction

Multidentate Ligand Passivation Mechanism

Troubleshooting Guide: [BMIM]OTF in Perovskite Quantum Dot Films

Issue 1: Inconsistent Improvement in Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Problem: The expected significant increase in PLQY is not observed after adding [BMIM]OTF. Questions to consider:

- What is the current PLQY measurement compared to the control sample?

- What was the method of [BMIM]OTF introduction (in-situ vs. post-synthesis)?

- What is the purity of the [BMIM]OTF source?

Solutions:

- Verify Synthesis Protocol: Ensure you are using the in-situ crystallization strategy. Add [BMIM]OTF dissolved in chlorobenzene directly to the lead bromide precursor solution to control nucleation, rather than post-synthetic treatment [4].

- Check Concentration: Optimize the amount of [BMIM]OTF. Research indicates using sequential addition to create variants like [BMIM]OTF-1, [BMIM]OTF-2, and [BMIM]OTF-3, with the highest performance often achieved at optimal concentrations that maximize crystallinity without introducing quenching sites [4].

- Confirm Purity: Use high-purity (≥98%) [BMIM]OTF to avoid unintended side reactions from impurities that can create new defect states.

Issue 2: Slow Electroluminescence (EL) Response Time

Problem: The device response time remains in the microsecond range and does not achieve nanosecond-scale improvement. Questions to consider:

- What is the current EL rise time (time to 90% of stable intensity)?

- Has the device capacitance been minimized?

- Are there other bottlenecks in charge injection?

Solutions:

- Reduce Device Area: The capacitance effect is a key factor limiting response speed. Decrease the light-emitting unit area to reduce capacitance, which was crucial for achieving the reported 700 ns response time [4] [36].

- Ensure Defect Passivation: The primary role of [BMIM]OTF is to reduce defect states that cause charge trapping. Use TRPL measurements to confirm a significant increase in average exciton recombination lifetime (τavg), which should increase from approximately 14 ns to 30 ns, indicating successful trap reduction [4].

Issue 3: Poor Quantum Dot Film Morphology or Crystallinity

Problem: Films appear non-uniform, or XRD analysis does not show enhanced crystallinity. Questions to consider:

- What does TEM analysis reveal about QD size and size distribution?

- Are the characteristic XRD peaks, especially for the (200) plane, intensified?

Solutions:

- Characterize Crystal Structure: Perform XRD analysis. A successful treatment will show significantly enhanced intensity for the (200) crystal plane peak, indicating improved crystallinity along this plane due to [BMIM]OTF interaction, without a shift in peak position [4].

- Monitor Size Distribution: Use TEM to confirm an increase in average QD size from ~8.8 nm to ~11.3 nm. This size growth and reduced surface area ratio are indicators of successful [BMIM]OTF-mediated crystallization [4].

Issue 4: Device Efficiency (EQE) Not Meeting Expectations

Problem: The external quantum efficiency (EQE) of the PeLEDs remains low despite [BMIM]OTF addition. Questions to consider:

- What is the current EQE and how does it compare to the control device?

- Has the charge injection barrier been effectively reduced?

Solutions:

- Interface Engineering: The ionic liquid should decrease the charge injection barrier at the interface. Check energy level alignment via UV-photoelectron spectroscopy or similar techniques to ensure favorable band alignment for carrier injection [4] [37].

- Cross-Check with Performance Metrics: Refer to the quantitative benchmarks. A properly optimized process should see EQE jump from ~7.6% to over 20% for standard devices, and reach up to 15.8% for ultra-high-resolution devices with pixel sizes of 1.3 μm [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary mechanism by which [BMIM]OTF reduces surface defects? A1: [BMIM]OTF acts through a dual coordination mechanism. The OTF⁻ anion has a stronger binding energy (Eb = -1.49 eV) with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ on the QD surface compared to traditional ligands like octanoic acid (Eb = -0.95 eV). Simultaneously, the [BMIM]+ cation coordinates with Br⁻ ions on the surface (Eb = -1.00 eV). This strong dual passivation effectively suppresses the formation of bromide vacancies and Pb-related defects, which are major non-radiative recombination centers [4].

Q2: Can [BMIM]OTF be used for other perovskite formulations beyond CsPbBr3? A2: While the cited research focuses on CsPbBr3 QDs, the fundamental passivation chemistry is likely applicable to other halide compositions (e.g., Cl, I) and mixed-cation perovskites. The key is the interaction between the OTF⁻ anion and the metal lead and the cation with the halides, which is a common feature in lead halide perovskites. However, optimization of concentration and processing conditions would be necessary [4] [38].

Q3: How does [BMIM]OTF enhance the crystallinity of perovskite QDs? A3: During the in-situ synthesis, the positively charged N+ of the [BMIM]+ ion coordinates with Br− ions, forming a complex with the [PbBr3]− octahedron. The imidazole ring also introduces a steric hindrance effect, which slows down the subsequent nucleation process when Cs+ cations combine with the octahedrons. This controlled, delayed nucleation promotes the growth of larger QDs with higher crystallinity, as evidenced by XRD and TEM [4].

Q4: Are there stability improvements associated with using [BMIM]OTF? A4: Yes, the enhanced surface passivation and reduced defect density contribute to improved operational stability. Research reports a significant increase in the T50 operational lifetime from 8.62 hours to 131.87 hours (normalized to an initial brightness of 100 cd/m²) for PeLEDs incorporating [BMIM]OTF-treated QDs [4].

Q5: What are the key characterization techniques to verify the effectiveness of [BMIM]OTF? A5: Essential characterization methods include:

- Transient Photoluminescence (TRPL): To measure the increase in exciton recombination lifetime.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To confirm enhanced crystallinity, particularly of the (200) plane.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To analyze the increase in QD size and uniformity.

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): To quantify the reduction in non-radiative recombination.

- Electroluminescence (EL) Response Measurement: To directly measure the improvement in device response speed [4].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics achieved with [BMIM]OTF treatment, as reported in the literature, providing benchmarks for your research.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Enhancement with [BMIM]OTF

| Performance Parameter | Control (Without [BMIM]OTF) | With [BMIM]OTF Optimization | Improvement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY (QD Solution) | 85.6% | 97.1% | +11.5% | [4] |

| Average Exciton Lifetime (τavg) | 14.26 ns | 29.84 ns | +109% | [4] |

| EL Response Rise Time | ~2.8 µs (extrapolated) | 700 ns | >75% reduction | [4] [36] |

| Maximum EQE (Standard Device) | 7.57% | 20.94% | ~2.8x increase | [4] |

| Maximum EQE (9072 PPI Device) | Not Reported | 15.79% | - | [4] |

| T50 Operational Lifetime (L₀=100 cd/m²) | 8.62 h | 131.87 h | ~15x increase | [4] |

| Peak Brightness | Not Reported | >170,000 cd/m² | - | [4] [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-situ Synthesis of [BMIM]OTF-Treated CsPbBr3 QDs

This protocol is adapted from the method used to achieve high-performance QDs [4].

Reagents Needed:

- Cesium acetate (C₂H₃CsO₂, 99.0%)

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂, 99.9%)

- 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF, ≥98%)

- Oleic Acid (OA, 90%)

- Oleylamine (OAm, 80-90%)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.5%)

- Chlorobenzene (CB, anhydrous)

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve PbBr₂ in DMF with standard OA and OAm ligands to create the lead bromide precursor solution.

- Ionic Liquid Addition: Dissolve a calculated amount of [BMIM]OTF in chlorobenzene. This solution is then added to the lead bromide precursor.

- Nucleation and Growth: Inject the cesium acetate precursor into the mixture under stirring. The [BMIM]OTF will modulate the nucleation process.

- Purification: Centrifuge the reaction mixture to isolate the QDs. Wash the pellet with a non-solvent like methyl acetate or toluene to remove unreacted precursors and excess ligands.

- Dispersion: Re-disperse the final QDs in an appropriate solvent like toluene or octane for film deposition.

Key Notes:

- Create a series of samples with varying [BMIM]OTF concentrations (e.g., [BMIM]OTF-1, [BMIM]OTF-2, [BMIM]OTF-3) to identify the optimal concentration for your specific setup [4].

- The entire synthesis should be performed in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox).

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Ultra-Fast PeLEDs

This protocol outlines the key steps for fabricating light-emitting diodes with nanosecond response [4] [36].

Key Steps:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean and plasma-treat ITO-coated glass substrates.

- Charge Transport Layers: Deposit hole injection and transport layers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) via spin-coating and annealing.

- Active Layer Deposition: Spin-coat the synthesized [BMIM]OTF-treated CsPbBr3 QD ink onto the transport layer to form the emissive film.

- Electrode Deposition: Thermally evaporate an electron transport layer (e.g., TPBi), a LiF interlayer, and finally a metal cathode (e.g., Al).

- Patterning for Speed: To achieve the fastest response, define very small active pixel areas (e.g., 1.3 μm pixel size) to minimize device capacitance, which is critical for the nanosecond operation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for [BMIM]OTF-based Perovskite QD Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| [BMIM]OTF | Primary additive for defect passivation & crystallinity enhancement. | Purity (≥98%) is critical. Acts as a crystallization modulator and surface passivator [4]. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead and halide source for the perovskite lattice. | High purity (≥99.9%) minimizes intrinsic impurities that act as defects [4]. |

| Cesium Acetate | Cesium source for the APbX₃ structure. | Acetate anion can assist in precursor conversion and may itself act as a ligand [4] [22]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligands for colloidal stability during synthesis. | Ratio and concentration affect QD growth, stability, and final film conductivity [4]. |

| Chlorobenzene | Solvent for [BMIM]OTF in the in-situ synthesis. | Anhydrous grade is required to prevent premature degradation of precursors [4]. |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Polar solvent for precursor dissolution. | Anhydrous grade is essential for reproducibility and high PLQY [4]. |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for synthesizing [BMIM]OTF-treated QDs and fabricating high-speed PeLEDs.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for PeLED fabrication.

The next diagram illustrates the proposed mechanism of defect passivation by [BMIM]OTF on the surface of a perovskite quantum dot.

Diagram 2: Mechanism of [BMIM]OTF passivation on QD surface.

Technical FAQs: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is a sacrificial layer in the context of perovskite quantum dot films? A sacrificial layer is a temporary material layer applied during fabrication that actively improves the interface quality of the final structure, often by preventing unwanted reactions or by passivating defects, and is sometimes removed or transformed after serving its purpose [39] [40]. In perovskite quantum dot (PQD) research, this strategy is emerging as a method to reduce surface trap density and enhance optoelectronic properties.

Q2: How do sacrificial layers specifically help reduce trap density in PQDs? Sacrificial layers and related interface engineering strategies help reduce trap density by:

- Suppressing Interfacial Reactions: Preventing the formation of defect-inducing layers, such as resistive silicon oxide (SiOx), during high-temperature processing of adjacent layers [39].

- Direct Defect Passivation: Coordinating with unsaturated bonds on the PQD surface, thereby eliminating charge trapping sites that cause non-radiative recombination [4].

- Promoting Favorable Crystallization: Modifying the crystal growth environment to produce larger, higher-quality QDs with a lower surface-area-to-volume ratio, which inherently reduces the number of surface defects [4].

Q3: Can a sacrificial layer be regenerated after its removal? Yes, for some systems, a key advantage is the ability to regenerate the sacrificial layer. Research on thin-film composite membranes has demonstrated that certain sacrificial layers, such as Fe3+-TA (tannic acid complexed with iron ions), can be removed and then re-coated in situ for multiple cycles, restoring performance after scaling or fouling occurs [40].

Troubleshooting Guides: Experimental Challenges

Issue: Incomplete Passivation or Low Film Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Problem: After applying the passivation strategy, the PQD film shows low PLQY, indicating a high density of non-radiative recombination centers.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient coordination of the passivation agent with the QD surface. | Analyze binding energies via Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations; perform Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). | Use passivators with stronger binding energy. For instance, the OTF− anion shows a higher binding energy to Pb²⁺ on QD surfaces (-1.49 eV) than common octanoic acid (-0.95 eV) [4]. |

| High surface area ratio of QDs, making full passivation difficult. | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for size analysis; statistical size distribution. | Employ additives like ionic liquid [BMIM]OTF to promote the growth of larger QD crystals, thereby reducing the surface area requiring passivation [4]. |

| Severe bulk recombination due to interior defects (e.g., Sn vacancies in Sn-based perovskites). | Thermally Stimulated Current (TSC) measurements to profile trap density and depth. | Incorporate smaller-sized additive ions (e.g., Ge) into the perovskite matrix to reduce bulk trap density and carrier concentration [41]. |

Recommended Workflow:

Issue: Poor Charge Injection and Slow Device Response

Problem: The fabricated PeLEDs or solar cells exhibit a slow rise in electroluminescence response or poor charge extraction, leading to low efficiency.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insulating surface ligands on QDs hindering charge transport. | Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL); measure device response time under pulse voltage. | Implement ligand engineering to replace long, insulating ligands with shorter, conductive ones, or use ionic liquids like [BMIM]OTF to improve carrier injection [4]. |

| High injection barrier at the interface between the QD layer and charge transport layer. | Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) for energy level alignment; current-density-voltage (J-V) characterization. | Insert an ultrathin organic interfacial layer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) to tune energy level alignment and facilitate charge transfer via efficient recombination [39]. |

| Massive charge trapping at the interface. | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) measurement; impedance spectroscopy. | Apply a sacrificial passivation layer that permanently heals interfacial defects, reducing trap-assisted recombination [42] [4]. |

Recommended Workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents used in advanced interfacial passivation strategies for perovskite quantum dot research.

| Reagent Name | Function / Role | Key Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS (Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrene sulfonate) | Sacrificial Interface Layer: Acts as a temporary layer to prevent resistive SiOx formation during subsequent layer deposition and enables efficient charge recombination [39]. | An ultrathin layer inserted between TCO and HTL restores junction functionality, enabling tandem solar cells with a fill factor up to 81.3% [39]. |

| [BMIM]OTF (1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate) | Crystallization Modifier & Defect Passivator: Enhances QD crystallinity, increases QD size, and passivates surface defects via coordination of both cation ([BMIM]+) and anion (OTF−) [4]. | Reduces EL response rise time by over 75% and boosts EQE from 7.57% to 20.94%. OTF− shows stronger binding to Pb²⁺ (-1.49 eV) than common ligands [4]. |

| LiTFSI (Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide) | Electron Transport Layer (ETL) Modifier: Passivates oxygen vacancies in SnO₂ ETL and improves energy level alignment with the perovskite layer [42]. | Treatment of SnO₂ ETL with LiTFSI increased PSC efficiency from 18.55% to 20.84% by improving charge extraction and reducing hysteresis [42]. |

| Ge ions (Germanium) | Bulk Additive: Reduces trap density and carrier concentration in tin-based perovskites, effectively passivating deep traps associated with Sn vacancies [41]. | 7.5 mol% Ge doping doubled the reduction of total trap density to 4.14 × 10²⁰ cm⁻³, increasing Voc from 0.36 V to 0.46 V in a tin-based PSC [41]. |

| Fe³⁺-TA Complex (Tannic Acid with Iron Ions) | Regenerable Sacrificial Layer: Forms a removable layer that improves surface smoothness and provides a physical barrier against scaling, which can be regenerated in situ [40]. | Demonstrated excellent anti-scaling performance and durability over six reuse cycles with a flux recovery rate exceeding 97% [40]. |

The following table summarizes quantitative performance improvements achieved by various interfacial and sacrificial layer strategies.

| Material System | Strategy / Reagent | Key Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolithic Perovskite/Si Tandem Solar Cell | Ultrathin PEDOT:PSS sacrificial layer | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE): 21.95%; Fill Factor (FF): 81.3% (among highest reported) [39]. | [39] |

| Perovskite Solar Cell (SnO₂ ETL) | LiTFSI modification of SnO₂ | PCE: Control 18.55% → Modified 20.84% [42]. | [42] |

| CsPbBr₃ Perovskite QLED | [BMIM]OTF treatment of QDs | EQE: 7.57% → 20.94%; PLQY: 85.6% → 97.1%; Avg. Exciton Lifetime: 14.26 ns → 29.84 ns; EL Response Time: Reduced by >75% [4]. | [4] |

| Tin-based Perovskite Solar Cell | 7.5 mol% Ge additive | Trap Density: Reduced to 4.14 × 10²⁰ cm⁻³ (approx. half of control); PCE: Control 3.96% → Ge-doped 7.45%; Voc: 0.36 V → 0.46 V [41]. | [41] |

| Thin-Film Composite Membrane | Fe³⁺-TA Sacrificial Layer | Flux Recovery: >97% over 6 reuse cycles in gypsum scaling tests [40]. | [40] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents essential for the optimized synthesis of reproducible, low-trap-density perovskite quantum dots.

| Reagent Name | Function / Role in Synthesis | Key Benefit / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-functional Acetate (AcO⁻) | Cesium precursor additive and surface ligand [12] [43] [44]. | Improves cesium salt conversion purity (from ~70% to ~99%), reduces by-products, and passivates surface dangling bonds [12] [44]. |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain ligand [12] [43] [44]. | Stronger binding affinity to QD surface than oleic acid; passivates defects and suppresses Auger recombination [12]. |