Advanced SPR Baseline Correction Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Accurate Biomolecular Interaction Analysis

This article provides a thorough examination of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) baseline correction data analysis methods, essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced SPR Baseline Correction Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Accurate Biomolecular Interaction Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a thorough examination of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) baseline correction data analysis methods, essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers fundamental principles from identifying sources of baseline drift and noise to advanced algorithmic correction techniques. The content explores specialized methodologies including dynamic baseline algorithms and double referencing, offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common experimental artifacts, and presents validation frameworks for assessing method performance. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical applications, this guide enables more reliable interpretation of SPR data, ultimately enhancing the accuracy of kinetic and affinity measurements in biomedical research.

Understanding SPR Baseline Drift: Sources, Impacts, and Fundamental Correction Principles

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, the sensorgram provides a real-time, label-free record of molecular interactions. The initial baseline phase of this sensorgram is not merely a starting point but a critical foundation that dictates the validity of all subsequent kinetic and affinity data extracted from the experiment. A properly established baseline represents a state of system equilibrium where the sensor surface is stable, the flow buffer is consistent, and no specific binding is occurring [1] [2]. Understanding, achieving, and maintaining this baseline is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on SPR for precise quantification of biomolecular interactions, as inaccuracies at this stage propagate through association, steady-state, and dissociation phases, potentially compromising the entire dataset [3]. This Application Note details the protocols and considerations for defining and optimizing the SPR baseline within the broader context of advanced data analysis methods.

The Role of the Baseline in Sensorgram Interpretation

Definition and Key Characteristics

The baseline is the initial flat line on a sensorgram, occurring before the analyte is introduced. It represents the signal from the immobilized ligand in contact with a continuous flow of running buffer [4]. During this phase, the system conditions the sensor surface and allows the investigator to check for any instabilities [1] [4]. An ideal baseline is stable and flat, indicating that the refractive index near the sensor surface is constant and that the instrument is optically stable [2]. The relative SPR response in a sensorgram, measured in Resonance Units (RU), is proportional to the mass of bound analytes; a stable initial baseline ensures that any change in this response can be accurately attributed to the binding event itself [1].

Impact on Data Analysis

The integrity of the baseline directly influences the accuracy of all calculated interaction parameters. The initial baseline value is used as the reference point (zero) for measuring the binding response during the association phase [5]. Consequently, baseline drift—a gradual increase or decrease in the signal before analyte injection—skews the measurement of the maximum response (Rmax) and the subsequent calculation of the association rate (k~on~) and dissociation rate (k~off~) [3] [2]. Since the equilibrium dissociation constant (K~D~) is derived from the ratio k~off~/k~on~, an unstable baseline can lead to incorrect affinity determinations [1] [5]. Furthermore, for experiments requiring a regeneration step, the baseline must return to its original level to ensure the sensor surface is properly prepared for a new analysis cycle [1] [6].

Experimental Protocols for Baseline Establishment

Pre-Experiment System Preparation

A stable baseline begins with meticulous preparation of the instrument and reagents.

Protocol 3.1.1: Buffer and Sample Preparation

- Running Buffer Selection: Use a high-purity, freshly prepared buffer. Common choices include phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 10 mM HEPES with 150 mM NaCl [1] [7]. The buffer must be compatible with both the ligand and analyte to maintain their stability and activity.

- Filtration and Degassing: Filter the running buffer through a 0.22 µm membrane and degas it thoroughly to prevent the formation of air bubbles within the microfluidic system, which can cause significant signal spikes and baseline noise [2] [6].

- Sample Clarification: Centrifuge or filter all analyte and ligand solutions through a 0.22 µm membrane to remove any particulate matter or aggregates that could non-specifically bind to the sensor surface or clog the fluidics [3] [6].

Protocol 3.1.2: Fluidic System Priming

- Initiate a system prime or flush with the filtered and degassed running buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions. This step is critical to remove storage solutions, air, and contaminants from the fluidic path [4].

- Ensure all buffer lines are primed with the correct running buffer. Switching between different buffers without adequate priming can create refractive index mismatches, leading to a bulk shift that destabilizes the baseline.

Establishing a Stable Baseline

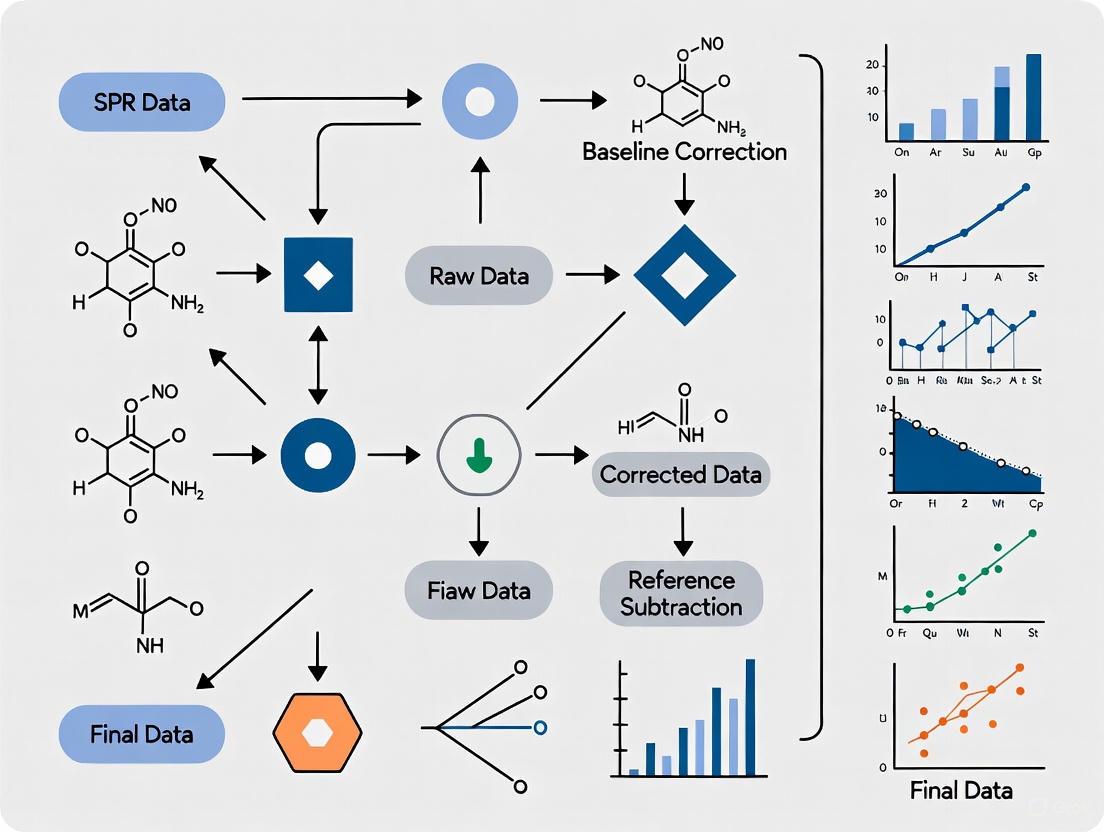

The following workflow is essential for achieving a baseline suitable for data acquisition. The diagram below outlines the key steps and decision points.

Protocol 3.2.1: Baseline Conditioning and Monitoring

- Initial Conditioning: After priming, initiate a continuous flow of running buffer over the sensor surface. A flow rate of 10-30 µL/min is typically used for conditioning, though this may be optimized for specific assays [3].

- Stability Monitoring: Observe the baseline signal for a minimum of 2-5 minutes. The signal is considered stable when the drift is less than 5 RU per minute [2]. Many modern SPR systems provide software-based drift measurements.

- Commence Experiment: Only once the baseline stability criteria are met should the experiment proceed to the injection of the analyte, marking the start of the association phase.

Troubleshooting Common Baseline Anomalies

Even with careful preparation, baseline issues can occur. The table below summarizes common problems, their causes, and solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for SPR Baseline Issues

| Anomaly | Primary Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift [2] | Contaminated sensor chip or buffer; air bubbles in fluidics; temperature fluctuations. | Clean fluidic system and sensor chip; replace buffer; ensure proper degassing; verify instrument temperature control. |

| Injection Spikes [1] [2] | Air bubbles in sample; particulate matter in sample; improper injection valve operation. | Centrifuge/filter samples; carefully load samples to avoid introducing air; perform air check on instrument. |

| High Buffer Response / Bulk Shift [3] | Mismatch between running buffer and analyte buffer composition (e.g., DMSO, salt, glycerol). | Match analyte buffer to running buffer exactly; use reference cell subtraction; dialyze samples into running buffer. |

| Noisy Signal (High RU) | Contaminated flow cell; degraded sensor chip; micro-bubbles. | Perform stringent system cleaning; replace sensor chip; ensure buffers are thoroughly degassed. |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when the analyte interacts with the sensor surface itself rather than the specific ligand. This can manifest as an elevated or drifting baseline even before analyte injection, or as an unexpectedly high binding response [3]. To mitigate NSB:

- Use a Reference Flow Cell: A surface without immobilized ligand is essential for subtracting signals arising from NSB and bulk refractive index effects [3] [6].

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: Add blocking agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA at 0.1-1%) or non-ionic detergents like Tween 20 (0.005-0.01%) to the running buffer to shield hydrophobic or charged surfaces [3] [6].

- Adjust pH or Ionic Strength: Modifying the pH to the isoelectric point of the analyte or increasing the salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) can reduce charge-based NSB [3].

- Change Sensor Chemistry: If NSB persists, switch to a sensor chip with a different surface chemistry (e.g., from CM5 to CM4 for highly positively charged molecules) [8] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials required for successful SPR experiments, with a focus on achieving a stable baseline.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Baseline Stability

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip [8] [6] | A carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent ligand immobilization. Versatile and chemically stable. | General protein-protein interactions; immobilization via amine coupling. |

| SA Sensor Chip [8] [6] | Pre-immobilized streptavidin for capturing biotinylated ligands. Ensures uniform orientation. | Immobilization of biotinylated DNA, antibodies, or carbohydrates. |

| NTA Sensor Chip [8] [6] | Pre-immobilized nitrilotriacetic acid for capturing His-tagged ligands via chelated nickel ions. | Oriented capture of recombinant His-tagged proteins. |

| HEPES-NaCl Buffer [1] [7] | A standard running buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Provides a stable ionic and pH environment. | A common starting point for most protein interaction studies. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) [1] [7] | A common regeneration solution for disrupting ligand-analyte complexes after a binding cycle. | Regeneration of antibody-antigen surfaces; returning baseline to its original level. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [3] | A blocking agent used to passivate the sensor surface, reducing non-specific binding. | Added to running buffer or sample diluent at 0.1-1% to minimize NSB. |

A rigorously defined and stable baseline is the non-negotiable cornerstone of accurate SPR data interpretation. It ensures that the measured changes in resonance signal faithfully represent the biomolecular interaction of interest, thereby guaranteeing the reliability of kinetic and affinity constants. By adhering to the detailed protocols for system preparation, baseline establishment, and proactive troubleshooting outlined in this document, researchers can significantly enhance the quality of their SPR data. As SPR technology continues to evolve, with increasing automation and sensitivity, the fundamental principles of baseline management remain critical for generating publication-quality data in drug discovery and basic research.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for the real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions. The accuracy of kinetic and affinity constants derived from SPR data hinges on the stability of the baseline response. Baseline drift, the gradual shift in the baseline signal prior to analyte injection, introduces significant inaccuracies by distorting the measurement of binding responses [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, identifying and mitigating the sources of drift is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental requirement for generating publication-quality data. Within the broader context of developing robust SPR baseline correction data analysis methods, understanding these experimental sources is the critical first step, informing the development of more effective post-hoc computational corrections. This application note details the common sources of baseline drift, categorized into instrumental noise, buffer effects, and surface instability, and provides targeted protocols for their diagnosis and resolution.

Understanding and Quantifying Baseline Drift

Baseline drift manifests as a gradual increase or decrease in resonance units (RU) over time when only running buffer is flowing over the sensor surface. An ideal baseline is stable, with a noise level typically below 1 RU [9]. Drift can be quantified by measuring the slope of the baseline (RU/minute) over a defined period before analyte injection. The table below summarizes the core characteristics and primary mitigation strategies for the three major sources of drift.

Table 1: Common Sources of SPR Baseline Drift and Their Characteristics

| Source Category | Common Manifestations | Key Characteristics | Primary Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental Noise | Electronic fluctuations, air bubbles, temperature instability, pump strokes [9] | Abrupt spikes, high-frequency noise, periodic fluctuations | System priming, proper maintenance, temperature control, degassing buffers |

| Buffer Effects | Bulk refractive index shifts, buffer mismatch, poor buffer hygiene [3] [10] | Square-shaped injection artifacts, slow continuous drift | Prepare fresh, filtered, degassed buffers; match buffer composition exactly |

| Surface Instability | Rehydration of new chips, ligand leaching, incomplete regeneration [9] [10] | Slow, continuous drift after docking or regeneration | Extended equilibration, optimized immobilization, surface "priming" with start-up cycles |

Protocols for Diagnosing and Correcting Drift

Protocol: Mitigating Instrumental and Buffer-Related Drift

This protocol establishes a foundation for a stable SPR system by addressing instrumental and buffer-related issues [9] [3].

Materials:

- Fresh running buffer (e.g., HEPES, PBS)

- 0.22 µm filter unit

- Degassing apparatus

Procedure:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare running buffer fresh daily. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter into a sterile container to remove particulates. Degas the buffer for at least 30 minutes to prevent air spike formation [9].

- System Priming: Prime the SPR instrument's fluidic system with the freshly prepared, degassed buffer. Repeat the prime command 2-3 times after a buffer change to ensure complete purging of the previous solution [9].

- Baseline Equilibration: Initiate a constant flow of running buffer (at the experimental flow rate) over a clean, undocked sensor chip or a docked but unimmobilized chip. Monitor the baseline for a minimum of 15-30 minutes, or until the drift rate falls below an acceptable threshold (e.g., < 1 RU/min) [9].

- Noise Level Assessment: Once the baseline is stable, perform several dummy injections of running buffer. The observed noise level should be low (e.g., < 1 RU) [9]. High noise indicates a need for further system cleaning or maintenance.

Protocol: Establishing a Stable Sensor Surface

This protocol ensures the sensor chip and immobilized ligand are sufficiently equilibrated to minimize surface-induced drift [9] [10].

Materials:

- Equilibrated SPR system with fresh running buffer

- Appropriate sensor chip (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA)

- Ligand and coupling reagents

Procedure:

- Chip Docking and Hydration: Dock a new sensor chip and initiate buffer flow. For newly docked chips or chips just after immobilization, plan for an extended equilibration time (30 minutes to several hours, sometimes overnight) to allow for the rehydration of the dextran matrix and wash-out of immobilization chemicals [9].

- Surface "Priming" with Start-up Cycles: Incorporate at least three start-up cycles into the experimental method. These cycles should mimic the experimental cycle exactly but inject running buffer instead of analyte. If a regeneration step is used, include it. These cycles are not used in the final analysis but serve to condition the surface [9].

- Monitor Post-Regeneration Drift: After a regeneration injection, closely observe the baseline. A significant drift that does not stabilize quickly may indicate an overly harsh or incomplete regeneration strategy, requiring optimization [3].

- Validation with Blank Injections: Space blank (buffer alone) injections evenly throughout the experiment. The consistent response from these blanks is used for double referencing, which compensates for residual drift and bulk effects during data analysis [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the systematic approach for diagnosing and addressing the primary sources of baseline drift.

Advanced Signal Processing for Drift Correction

Even with optimized experimental practices, some drift may persist. Advanced signal processing methods can be applied during data analysis to correct for these residual effects.

- Double Referencing: This is a standard and highly effective procedure. First, subtract the signal from a reference flow cell (no ligand immobilized) from the active flow cell signal. This corrects for bulk refractive index shifts and some instrumental drift. Second, subtract the average response from multiple blank injections (buffer alone) from the analyte injection data. This corrects for systematic drift and channel-specific differences [9].

- Projection Method for SNR Improvement: A computational "projection method" has been developed to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of SPR signals. This method projects a normalized measured transmission spectrum onto a pre-simulated reference matrix of spectra spanning a range of refractive indices. The resulting "solution vector" is interpolated to provide a precise refractive index estimate, effectively transforming a noisy measurement into a smooth curve and improving the limit of detection [11].

- Dynamic Baseline Adjustment with PSO: For fiber SPR sensors, a dynamic baseline adjustment method using a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm has been shown to effectively track the resonance point in reflection spectra. The PSO algorithm optimizes the parameters for selecting the best dynamic baseline, outperforming traditional centroid methods, especially under conditions of light source fluctuation, leading to more accurate resonance wavelength determination [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating SPR Baseline Drift

| Item | Function in Drift Mitigation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Filter | Removes particulates from buffers that could clog microfluidics or cause light scattering [9]. | Essential for all running and sample buffers immediately before use. |

| Degassing Apparatus | Removes dissolved air to prevent the formation of air bubbles in the flow system, which cause spikes and instability [9]. | Degas buffers for >30 mins; do not store degassed buffers at 4°C. |

| Non-ionic Surfactant (e.g., Tween-20) | Reduces non-specific binding (NSB) and minimizes hydrophobic interactions between analyte and surface that can cause drift [3] [10]. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.005-0.01%) in running buffer. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Blocks unreacted groups on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization, preventing NSB and stabilizing the baseline [10]. | Ethanolamine is standard for amine coupling; BSA for blocking in other strategies. |

| High-Purity Water & Salts | Ensures consistent buffer ionic strength and pH, minimizing refractive index changes due to buffer mismatch or contaminants [9] [7]. | Use ASTM Type I water and high-purity salts for buffer preparation. |

A stable baseline is the cornerstone of reliable SPR data. Baseline drift, originating from instrumental factors, buffer inconsistencies, or surface instability, can significantly compromise the accuracy of determined kinetic and affinity parameters. By adopting a systematic approach—incorporating rigorous buffer management, instrumental maintenance, surface conditioning protocols, and robust data processing techniques like double referencing—researchers can effectively minimize and correct for baseline drift. Mastering these practices is an indispensable prerequisite for advancing SPR baseline correction data analysis methods and ensures the generation of high-quality, trustworthy data in both academic research and pharmaceutical development.

The Critical Impact of Uncorrected Baseline on Kinetic Parameter Calculation

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for quantifying biomolecular interactions in real-time, playing a critical role in drug discovery and basic research [13] [14]. The accuracy of kinetic and affinity constants (kₐ, kd, KD) derived from SPR data is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the baseline—the signal prior to analyte injection. An uncorrected or unstable baseline introduces significant errors into these calculated parameters, potentially compromising scientific conclusions and decisions in lead compound development [15] [3]. This application note details the sources and impacts of baseline irregularities and provides a validated protocol for their identification and correction, framed within a comprehensive data analysis methodology.

The Critical Role of Baseline Stability in SPR Analysis

The baseline is the foundation upon which all binding response measurements are built. In SPR kinetics, the calculation of observed rate constants (kobs) and the subsequent derivation of kₐ and kd rely on the precise measurement of response changes from the baseline level. A shifting baseline directly distorts the measured response (RU) over time, leading to inaccurate fitting of the binding curves [3]. Furthermore, the initial baseline value is critical for setting the baseline for analyte injection and for the accurate calculation of Rmax, the maximum binding response. An error in Rmax propagates directly into an error in the calculated kₐ [16].

The following diagram illustrates how baseline-related issues are integrated into the overall SPR data acquisition and analysis workflow, highlighting key points where errors can be introduced and identified.

Quantifying the Impact of Common Baseline Artifacts

Systematic baseline errors manifest in distinct ways, each with a specific impact on the calculated kinetic parameters. The following table summarizes the primary artifacts, their visual characteristics, and their consequent effects on data analysis.

Table 1: Impact of Common Baseline Artifacts on Kinetic Parameter Calculation

| Artifact Type | Visual Signature in Sensorgram | Impact on Kinetic Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Refractive Index (RI) Shift [3] | Square-shaped response shift at injection start/end; positive or negative. | Obscures true binding response, complicating analysis of interactions with fast kinetics; can be partially corrected via reference subtraction. |

| Instrumental Drift [15] | Continuous, gradual signal increase or decrease throughout the experiment. | Shifts baseline for subsequent analyte injections, leading to inaccurate Rmax calculation and introducing error in ka. |

| Incomplete Regeneration [3] | Successively higher baseline after each regeneration step; residual analyte remains bound. | Reduces available binding sites for next injection, artificially lowering response and affecting both affinity (KD) and kinetic constants. |

| Non-Specific Binding (NSB) [3] | Elevated response on reference or bare surface; binding signal does not follow expected concentration dependence. | Inflates measured response, skewing calculated RU and leading to overestimation of binding affinity. |

Detailed Protocol for Baseline Correction

This step-by-step protocol guides the user through identifying baseline issues and applying appropriate corrections to ensure data integrity.

Pre-Experiment Preparation and Planning

- Buffer Matching: Precisely match the chemical composition (including salts, additives, and pH) of the running buffer and analyte sample buffer to minimize bulk RI shifts [3].

- Ligand Immobilization: Aim for a low to moderate ligand density (e.g., ~50-100 RU for kinetics) to minimize mass transport effects and non-specific binding [3]. Document the immobilization level (e.g., 2500 RU as in one study [13]).

- Reference Surface: Use an in-line reference flow cell or channel. The surface should mimic the active surface as closely as possible but lack the specific ligand [16].

- System Equilibration: Before data collection, run the system with running buffer until a stable baseline is achieved, typically with a slope of < 0.3 RU/min [3].

Data Acquisition and Real-Time Monitoring

- Include Blank Injections: Inject running buffer or a zero-concentration analyte sample. This serves as a critical control for identifying bulk RI shifts and instrumental noise [16].

- Verify Regeneration Efficiency: After each regeneration cycle, inject a known, intermediate analyte concentration as a positive control. A consistent binding response confirms that the ligand activity remains unchanged [3].

Post-Run Data Analysis and Correction

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract the sensorgram from the reference flow cell from the active flow cell sensorgram. This corrects for bulk RI shifts and some non-specific binding [3] [16].

- Blank Subtraction: Further subtract the response from the blank injection (buffer alone) from all analyte sample sensorgrams. This helps account for any injection artifacts [16].

- Baseline Alignment: If a slow, consistent instrumental drift is present, manually adjust the baseline of the dissociation or regeneration phase to align it with the pre-injection baseline level, using the software's alignment tool. Avoid using this to correct for large, systematic errors.

Validation of Corrected Data

- Visual Inspection: The corrected sensorgrams should display clean association and dissociation phases. The baseline before injection and after complete dissociation should be flat and stable [16].

- Residual Plot Analysis: After fitting the kinetic model, examine the residuals (difference between fitted curve and raw data). The residuals should be randomly distributed around zero, not showing any systematic patterns [16].

- Chi² Value: The Chi² value should be low, and its square root should be on the same order of magnitude as the instrument's noise level [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Baseline Management

| Reagent / Material | Function in Baseline Management | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [3] | Additive to block non-specific binding on sensor surfaces and in sample solutions. | Typically used at 0.1-1% concentration. Add to running and sample buffers only during analyte runs to avoid coating the ligand. |

| Non-Ionic Surfactant (e.g., Tween 20) [3] | Reduces hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB. | Use at low concentrations (e.g., 0.005-0.01% v/v). Effective in both running buffer and sample dilution. |

| High-Salt Buffer (e.g., NaCl) [3] | Shields charge-based interactions between analyte and sensor surface. | Concentration varies (e.g., 150-500 mM). Test to find optimal concentration without disrupting specific binding. |

| Carboxylmethylated Dextran Sensor Chip (e.g., CM5) | Standard sensor chip for amine-coupling ligand immobilization. | A well-characterized surface. The immobilization level should be documented (e.g., 2500 RU) [13]. Low density minimizes mass transport. |

| Reference Sensor Chip | Provides a surface for control subtraction of bulk RI and NSB signals. | Should be activated and deactivated (blocked) identical to the active surface, but without ligand immobilization [16]. |

Advanced Validation and Troubleshooting

For complex interactions or when high-precision kinetics are required, advanced validation is necessary.

- Vary Flow Rates: Run the assay at multiple flow rates (e.g., 30, 50, 100 µL/min). If the observed association rate (k_obs) increases with higher flow rates, the system is likely mass-transport limited, which can be misinterpreted as a baseline issue [16].

- Global Analysis: Fit all analyte concentrations simultaneously to a single model. This provides more robust and reliable kinetic parameters compared to individual curve fitting [16].

- Self-Consistency Checks: Verify that the KD calculated from kinetics (kd/kₐ) matches the KD derived from equilibrium analysis (steady-state response). Also, ensure the kd from the dissociation phase matches the k_d fitted from the association phase [16].

The following decision tree outlines the advanced troubleshooting process to diagnose and address persistent issues after initial correction.

A stable and properly corrected baseline is not merely a data presentation preference but a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining accurate kinetic and affinity constants from SPR experiments. Uncorrected baseline artifacts directly compromise the integrity of kₐ, kd, and KD values, potentially leading to flawed scientific and development decisions. By implementing the systematic protocols outlined here—including careful experimental design, rigorous reference and blank subtraction, and comprehensive validation—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their SPR data. Adherence to these practices ensures that the powerful analytical capabilities of SPR are fully realized, providing high-quality data to accelerate drug discovery and deepen the understanding of molecular interactions.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a label-free technology that quantitatively measures biomolecular interactions in real-time, making it indispensable in drug discovery for characterizing affinity, kinetics, and concentration [17] [18]. The accurate interpretation of SPR data hinges on the quality of the baseline, which represents the system's signal when no binding is occurring. Baseline anomalies, caused by instrumental drift, refractive index changes, or non-specific binding, can obscure true binding events and lead to inaccurate kinetic parameter estimation. Therefore, robust baseline correction is a foundational step in SPR data analysis, ensuring the validity of results from early target validation to lead optimization [17] [19]. This document outlines a progression of correction methods, from simple subtractive techniques to sophisticated algorithm-based approaches, providing a structured framework for researchers to enhance their data integrity.

Fundamental Correction Principles

The Role of the Baseline in SPR Analysis

In SPR assays, the baseline establishes a reference point of zero response, corresponding to a state of no interaction between the ligand and analyte. A stable baseline is critical for the accurate determination of key interaction parameters. The association rate constant (ka) describes how quickly a complex forms, the dissociation rate constant (kd) measures how quickly it breaks apart, and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), calculated as kd/ka, quantifies the overall binding affinity [17]. A drifting or unstable baseline can distort the measurement of these parameters, potentially leading to the misclassification of lead compounds during critical stages of drug discovery, such as fragment screening and hit confirmation [17] [20].

- Instrumental Noise: Electronic noise from detectors and light sources creates high-frequency signal fluctuations. The spectrometer's diffraction grating and CCD sensor have wavelength-dependent efficiencies that shape the recorded spectrum and contribute to noise [15].

- Bulk Refractive Index Changes: Shifts in buffer composition, temperature, or solvent concentration after sample injection can cause sudden baseline steps or drifts, which are not related to specific binding events [17].

- Non-Specific Binding: Analyte molecules interacting with the sensor surface or ligand in a non-specific manner can cause a slow, continuous signal drift that mimics true binding [19].

- Systematic Instrumental Effects: The measured SPR spectrum is a convolution of the true resonance and the transfer functions of every optical component in the system, including the light source, polarizers, and optical fibers. Without correction, this can shift the observed resonance wavelength [15].

From Simple Subtraction to Advanced Algorithms

Simple Subtraction and Fitting Methods

The most straightforward baseline correction methods involve establishing a reference and subtracting it from the sensorgram.

- Blank Subtraction: A standard method involves running a reference flow cell with no immobilized ligand or an irrelevant ligand. The signal from this reference cell, which captures all non-specific effects and bulk shifts, is subtracted from the active cell's signal [17].

- Pre- and Post-Injection Fitting: The baseline before analyte injection is fitted to a line or curve to establish a starting point. After dissociation, the final baseline level is fitted, often with an exponential decay model, and this fitted line is used for subtraction to isolate the binding signal.

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Baseline Correction Methods

| Method | Principle | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank Subtraction | Subtracts signal from a reference flow cell | All SPR assays with a available reference channel | Requires a well-designed reference surface; may not capture all non-specific effects |

| Linear Fitting | Fits a straight line to pre-injection baseline | Assays with minimal instrumental drift | Ineffective for correcting non-linear drift or complex artifacts |

| Exponential Fitting | Fits an exponential curve to the dissociation phase | Correcting for slow dissociation or baseline drift post-injection | Model-dependent; can over-correct and distort kinetic parameters if misapplied |

Advanced Algorithmic Approaches

For complex systems and higher precision, advanced algorithms that model the entire SPR system are required.

- Transfer Function (TF) Modeling: This novel approach moves beyond simple signal processing to model the entire SPR spectrometer. The system's total transfer function is the product of the individual TFs of each component (light source, polarizer, optical fibers, spectrometer, etc.):

H_TOTAL(λ) = H_light(λ) * H_polarizer(λ) * H_fiber(λ) * H_spectrometer(λ)[15]. By characterizing these functions, a comprehensive model of the system's response is created. This model can then be used to correct the measured SPR spectrum, effectively deconvoluting the instrumental response from the true biological signal. This method has demonstrated a similarity of greater than 95% between the model and experimental spectra [15]. - Spectral Centroid and Minimum Identification: These algorithms process the raw spectral data to identify the resonance wavelength. The centroid method calculates the center of mass of the SPR dip, while the minimum method identifies the wavelength of lowest intensity [15]. These are more robust than simple subtraction but can still be influenced by the spectrometer's detector response.

- Detector-Specific Correction Models: Advanced methods account for the wavelength-dependent efficiency of the spectrometer's detector (e.g., Silicon or InGaAs). Distinct correction models are applied to compensate for this, improving the symmetry, depth, and width of the SPR spectrum for more accurate resonance determination [15].

Table 2: Advanced Algorithmic Correction Methods

| Algorithm | Underlying Principle | Key Advantage | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Function Modeling | Models the physical response of each optical component in the system | Highly accurate; corrects distortions at the source | High (requires detailed characterization of each component) |

| Spectral Centroid Calculation | Determines the center of mass of the SPR dip | Robust against asymmetric noise | Medium (integrated into some instrument software) |

| Detector-Response Correction | Applies a model to correct for the specific detector's efficiency | Improves spectral shape metrics (FWHM, depth) without fitting | Medium (requires pre-calibrated models) |

Experimental Protocols for Baseline Correction

Protocol: System Characterization for Transfer Function Modeling

This protocol details the steps for characterizing an SPR instrument's transfer function, as demonstrated in recent research [15].

1. Objective: To determine the individual transfer functions of each optical component in a homemade SPR spectroscopy system to create a comprehensive model for accurate spectral correction.

2. Materials and Reagents

- SPR spectrometer (e.g., configured in Kretschmann geometry)

- Stabilized tungsten-halogen light source (e.g., Thorlabs SLS201L)

- Linear polarizer (e.g., Thorlabs LPVISE050-A)

- Optical fibers

- High-refractive-index prism with gold film sensor chip

3. Methodology

- Step 1: Characterize the Spectrometer TF

- Use the manufacturer's data for the diffraction grating efficiency,

G(λ), and the CCD sensor responsivity,S(λ). - Calculate the spectrometer TF as:

H_Spec(λ) = G(λ) * S(λ)[15].

- Use the manufacturer's data for the diffraction grating efficiency,

- Step 2: Characterize the Light Source

- Model the lamp's emission spectrum,

X(λ), using Planck's law. Fit the published spectrum to determine an optimal blackbody temperature (e.g., 2650 K for a tungsten-halogen lamp) [15].

- Model the lamp's emission spectrum,

- Step 3: Characterize the Polarizer

- Experimentally determine the polarizer's transmittance,

P(λ), by measuring incident and transmitted light intensities across the relevant wavelength range (e.g., 350–1000 nm). Account forH_Spec(λ)during this measurement.

- Experimentally determine the polarizer's transmittance,

- Step 4: Assemble the Total Transfer Function

- Combine the individual TFs to obtain the total system TF:

H_Total(λ) = X(λ) * P(λ) * H_Spec(λ) * ...(including all other components).

- Combine the individual TFs to obtain the total system TF:

- Step 5: Validate and Apply the Model

- Compare the theoretical response generated by the model with an experimental SPR measurement. A successful model should reproduce the experimental spectrum with high similarity (>95%).

- Use the model to correct subsequently acquired SPR spectra, leading to a more accurate determination of the resonance wavelength.

System Characterization Workflow

Protocol: Standardized Baseline Correction for Binding Assays

This protocol is designed for routine binding assays, such as those used in fragment screening or bispecific molecule validation [19] [20].

1. Objective: To acquire and process SPR sensorgram data with proper baseline correction for reliable kinetics and affinity analysis.

2. Materials and Reagents

- SPR instrument (e.g., Alto Digital SPR or comparable system)

- Running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP)

- Ligand and analyte samples

- Regeneration solution (e.g., glycine-HCl)

3. Methodology

- Step 1: System Preparation and Equilibration

- Dock the sensor chip and prime the system with running buffer until a stable baseline (low drift, e.g., < 1 RU/min) is achieved.

- Step 2: Ligand Immobilization and Reference Setup

- Immobilize the ligand onto the sensor surface via standard amine coupling or capture methods.

- Use a reference flow cell that is activated and deactivated without ligand, or immobilized with an irrelevant molecule.

- Step 3: Double-Referenced Data Collection

- For each analyte injection cycle:

- Record a buffer injection over both ligand and reference surfaces.

- Inject the analyte sample over both surfaces.

- Process the data by first subtracting the reference cell signal from the ligand cell signal. Then, subtract the buffer injection signal from the analyte injection signal to yield a double-referenced sensorgram [20].

- For each analyte injection cycle:

- Step 4: Post-Run Baseline Alignment

- Align the baseline to zero response units (RU) at the start of each injection.

- If the post-dissociation baseline does not return to the pre-injection level, fit the final part of the dissociation phase and use this fitted baseline for final adjustment before kinetic fitting.

Binding Assay Correction Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SPR Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Alto Digital SPR System | Automated SPR platform for affinity, kinetics, and epitope mapping. | Uses digital microfluidics (DMF) to reduce sample consumption and hands-on time [17]. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Gold surface with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent ligand immobilization. | Standard for amine coupling; suitable for most proteins and other biomolecules. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | Running buffer containing HEPES, NaCl, EDTA, and surfactant P20. | Provides a stable pH and ionic strength; surfactant reduces non-specific binding. |

| G-Protein Coupled Receptor (GPCR) | Stabilized variant of neurotensin receptor 1 (NTS1) for fragment screening. | Essential for studying challenging membrane protein targets; requires stabilization for SPR analysis [20]. |

| Nitrilotriacetic Acid (NTA) Chip | Sensor surface for capturing His-tagged proteins. | Ideal for capturing recombinant proteins; allows for surface regeneration and ligand reuse. |

Mathematical Representation of Baseline Correction in SPR Signals

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technology for real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions, widely used in drug discovery, life sciences, and diagnostic development [18] [14]. The accurate interpretation of SPR data depends critically on proper baseline correction to eliminate instrumental artifacts and non-specific binding effects that can obscure true binding signals. Baseline correction is a mathematical process essential for isolating specific molecular interaction signals from systematic noise, enabling precise determination of kinetic parameters and binding affinities [21] [3].

This protocol outlines a comprehensive transfer function approach for baseline correction in SPR spectroscopy, providing researchers with a rigorous mathematical framework to correct instrumental distortions and obtain accurate, reproducible interaction data. The methods described are particularly valuable for applications requiring high sensitivity, such as characterization of low-affinity interactions, analysis of complex biological matrices, and detection of subtle conformational changes.

Theoretical Foundation

The Transfer Function Concept in SPR Systems

The transfer function (TF) approach, adapted from control systems engineering, provides a powerful mathematical framework for characterizing how each component in an SPR system modifies the incident light as a function of wavelength [15]. In this model, the entire SPR spectrometer is treated as a system that transforms an ideal theoretical input signal (X) into the measured experimental output (Y) through the cumulative effect of all optical components.

The total system transfer function is expressed mathematically as the product of individual component transfer functions:

H_TOTAL(λ) = H_1(λ) · H_2(λ) · ... · H_n(λ) [15]

Where:

H_TOTAL(λ)= Overall system transfer functionH_i(λ)= Transfer function of the i-th componentλ= Wavelength

This approach enables researchers to model the complete optical path mathematically, facilitating precise correction of measured spectra by reversing the systematic distortions introduced by each component [15].

Mathematical Representation of Component Transfer Functions

Table 1: Mathematical representations of individual component transfer functions in an SPR system

| System Component | Transfer Function | Mathematical Representation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Spectral radiance | I(λ,T) = (2πhc²/λ⁵) · 1/(e^(hc/λk_BT)-1) [15] |

h = Planck's constant, c = speed of light, k_B = Boltzmann constant, T = temperature (K) |

| Polarizer | Transmittance | P(λ) = I_transmitted(λ)/I_incident(λ) [15] |

Experimentally determined transmittance spectrum |

| Spectrometer | Detection efficiency | H_Spec(λ) = G(λ) · S(λ) [15] |

G(λ) = grating efficiency, S(λ) = CCD responsivity |

| SPR Sensor | Reflectance | Characteristic matrix theory [15] [22] | Complex dielectric constants of prism, metal films, and analyte |

| Optical Fibers | Attenuation | A(λ) = I_out(λ)/I_in(λ) [15] |

Experimentally determined attenuation spectrum |

Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive System Characterization

Objective: To determine the individual transfer functions of all optical components in the SPR instrumentation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Stabilized tungsten-halogen light source (e.g., Thorlabs SLS201L)

- Linear polarizer (e.g., Thorlabs LPVISE050-A)

- Spectrometer with CCD detector (e.g., Thorlabs CCS200)

- Optical fibers and connectors

- SPR sensor chip with appropriate metal coating

- Reference materials for validation

Table 2: Research reagent solutions for SPR baseline correction studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips | Carboxyl-modified, NTA, CM5 [3] | Provides surface for ligand immobilization with specific chemistry |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [3] | Reduces non-specific binding to sensor surface |

| Detergents | Tween 20 [3] | Minimizes hydrophobic non-specific interactions |

| Regeneration Solutions | Glycine-HCl (10-100 mM, pH 1.5-3.0) [3] | Removes bound analyte without damaging ligand activity |

| Buffer Additives | NaCl (0.1-1 M) [3] | Reduces charge-based non-specific interactions |

| Reference Analytes | Carbonic Anhydrase II with Acetazolamide [21] | Positive control for binding interactions |

Procedure:

Spectrometer Characterization

Light Source Characterization

- Measure emission spectrum using pre-characterized spectrometer

- Fit experimental data to Planck's law using non-linear regression

- Determine optimal blackbody temperature (typically ~2650 K for tungsten-halogen lamps) [15]

Polarizer Characterization

- Measure incident light intensity

I_incident(λ)without polarizer - Measure transmitted light intensity

I_transmitted(λ)with polarizer aligned to polarization axis - Calculate polarizer transfer function:

P(λ) = I_transmitted(λ)/I_incident(λ) - Apply Savitzky-Golay filter (window size=15, polynomial order=3) to smooth data [15]

- Measure incident light intensity

Optical Fiber Characterization

- Measure input light intensity

I_in(λ)before fiber optic path - Measure output light intensity

I_out(λ)after fiber optic path - Calculate attenuation transfer function:

A(λ) = I_out(λ)/I_in(λ)

- Measure input light intensity

SPR Sensor Modeling

System Characterization Workflow

Baseline Correction of Experimental SPR Data

Objective: To apply the system transfer function model to correct experimental SPR spectra for instrumental artifacts.

Procedure:

Data Acquisition

- Collect raw experimental SPR spectrum

Y_exp(λ) - Record all experimental conditions (temperature, flow rates, buffer composition)

- Collect raw experimental SPR spectrum

Theoretical Signal Calculation

Transfer Function Application

- Calculate total system transfer function:

H_TOTAL(λ) = H_Source(λ) · H_Polarizer(λ) · H_Fiber(λ) · H_Spec(λ) - Apply inverse transfer function to obtain corrected spectrum:

X_corrected(λ) = Y_exp(λ) / H_TOTAL(λ)

- Calculate total system transfer function:

Validation and Quality Control

- Compare corrected spectrum with theoretical prediction

- Calculate similarity metric (e.g., R² > 0.95 indicates successful correction) [15]

- Verify signal-to-noise ratio remains acceptable across operational range

Baseline Correction Process

Data Processing and Analysis

Pre-processing of SPR Sensorgrams

For kinetic analysis, additional baseline processing steps are required beyond spectral correction:

- Zero in Y-axis: Select timeframe before injection start and set baseline to zero [21]

- Cropping: Remove stabilization periods and regeneration steps [21]

- Zero in X-axis: Align injection start to t=0 [21]

- Reference Subtraction: Compensate for bulk refractive index differences [21] [3]

- Blank Subtraction: Subtract zero-analyte injections (double referencing) [21]

Quantitative Assessment of Correction Quality

Table 3: Key metrics for evaluating baseline correction performance

| Performance Metric | Mathematical Representation | Target Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity Index | S = [1 - Σ(X_corr - X_theo)²/Σ(X_theo)²] × 100% [15] |

>95% [15] | Overall correction accuracy |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | SNR = μ_signal/σ_noise |

Application dependent | Measurement precision |

| Spectral Symmetry (SMT) | Symmetry around resonance minimum [15] | Maximize | Indicator of proper correction |

| Resonance Depth (DRD) | Depth of resonance dip [15] | Application dependent | Signal strength |

| Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) | Width of resonance at half depth [15] | Minimize | Sensor resolution |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Artifacts and Solutions

Bulk Shift Effects: Manifest as square-shaped sensorgrams due to refractive index mismatch between analyte and running buffer [3]. Mitigate by matching buffer components or using reference subtraction.

Incomplete Regeneration: Leads to residual binding between cycles [3]. Optimize regeneration solution (e.g., glycine-HCl pH 1.5-3.0) and contact time.

Mass Transport Limitations: Appear as linear association phases without curvature [3]. Address by increasing flow rates or reducing ligand density.

Non-Specific Binding (NSB): Causes inflated response units [3]. Reduce through buffer additives (BSA, Tween 20), pH adjustment, or increased salt concentration.

Model Refinement Strategies

- For systems with high similarity index (<95%), refine optical constants of thin films using ellipsometry [15]

- For noisy corrected spectra, apply Savitzky-Golay filtering to transfer functions before application [15]

- When extending operational range, monitor signal-to-noise ratio at spectrum edges [15]

The transfer function approach to SPR baseline correction provides a rigorous mathematical framework for isolating true molecular interaction signals from instrumental artifacts. By systematically characterizing each optical component and applying the appropriate inverse transformations, researchers can achieve >95% similarity between theoretical and corrected experimental spectra [15]. This methodology enables more accurate extraction of kinetic parameters and binding affinities, which is particularly valuable for drug discovery applications where small molecule characterization demands high precision [14].

The protocols described herein form an essential component of SPR data analysis methodology, supporting the generation of publication-quality data with well-characterized uncertainty sources. When implemented as part of a comprehensive SPR workflow—including proper experimental design, surface chemistry optimization, and appropriate referencing strategies—this mathematical approach to baseline correction significantly enhances data reliability and reproducibility.

SPR Baseline Correction Techniques: From Dynamic Algorithms to Referencing Strategies

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, the accurate determination of biomolecular interactions is often compromised by instrumental noise and drift. The dynamic baseline algorithm has emerged as a powerful mathematical correction method that maintains a constant area ratio of the SPR curve above and below a baseline, providing exceptional robustness against common noise sources, particularly fluctuations in optical power [24]. This protocol details the implementation of this algorithm for both centroid and curve-fitting analysis methods, enabling researchers to achieve higher data quality and reliability in kinetic and affinity studies.

Theoretical Foundation

Core Principle of Area Ratio Constancy

The fundamental operation of the dynamic baseline algorithm is its adjustment of the analysis baseline (P_B) to maintain a pre-defined, constant ratio (λ) between the integrated area of the SPR curve below the baseline and the area above it [24]. This is mathematically described by the equation:

λ = ∫_{θ_1}^{θ_2} [P_B - P(θ)] dθ / ∫_{θ_1}^{θ_2} [P(θ) - P_B] dθ [24]

Where:

λis the fixed area ratio.P(θ)is the detector response at angle of incidenceθ.P_Bis the dynamically adjusted baseline level.θ_1andθ_2define the angular range of the SPR curve.

This adjustment compensates for multiplicative noise (e.g., light source intensity drift) and additive noise (e.g., detector dark signal changes), making the final calculated resonance position (θ_res) insensitive to these fluctuations [24].

Algorithm Workflow and Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for implementing the dynamic baseline algorithm.

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Baseline Centroid Method

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for implementing the dynamic baseline algorithm in conjunction with the centroid method for angular interrogation SPR systems [24].

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip | Platform for ligand immobilization. Choice depends on ligand properties and coupling chemistry [3]. | CM5 (carboxylated dextran matrix); NTA sensor for His-tagged proteins [3] [25]. |

| Running Buffer | Continuous phase for analyte delivery. Must match analyte buffer to minimize bulk shift [3]. | 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 [25]. Other common buffers: PBS. |

| Ligand Molecule | The interactor immobilized on the sensor chip. Should be pure and preferably the smaller partner [3]. | Purified protein, e.g., sDDR2 [25]. |

| Analyte Molecule | The interaction partner flowed over the ligand. Serial dilutions prepared in running buffer [3]. | e.g., C1q proteins, 0-40 μg/mL for KD determination [25]. |

| Regeneration Solution | Strips bound analyte from ligand without damaging activity [3]. | Mild acid/base (e.g., 10 mM Glycine pH 2.5) or high salt [3]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Setup and Ligand Immobilization

- Prime the SPR instrument with filtered and degassed running buffer.

- Immobilize the ligand onto an appropriate sensor chip surface using a standard coupling chemistry (e.g., amine coupling for CM5 chips). In the provided example, sDDR2 was immobilized using 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.0-6.0) as a scouting buffer [25].

- Employ a reference flow cell (immobilized with a non-interacting molecule or activated then deactivated surface) for control subtraction [3].

Data Collection

- Inject a series of analyte concentrations over the ligand and reference surfaces. Use a minimum of five concentrations spanning from 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value for kinetic analysis [3]. A sample set could be 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL [25].

- Record sensorgrams (reflectivity vs. angle/time) for all analyte injections.

- Include a regeneration injection if the complex does not fully dissociate spontaneously, ensuring the baseline returns to the pre-injection level before the next cycle [3].

Software-Aided Dynamic Baseline Calculation

- Extract the SPR curve (reflectivity vs. angle,

P(θ)) at a specific time point for analysis. - Define the target area ratio,

λ. This value may be determined empirically from a stable, high-quality SPR curve. - Implement an iterative solver (e.g., PSO, bisection method) to find the baseline

P_Bthat satisfies the constant area ratio condition defined in Section 2.1. - Calculate the resonance angle

θ_resusing the standard centroid formula with the dynamically determinedP_B[24]:θ_res = ∫_{θ_1}^{θ_2} (P_B - P(θ)) θ dθ / ∫_{θ_1}^{θ_2} (P_B - P(θ)) dθ - Repeat this calculation for every sensorgram point or averaged window to track the resonance angle shift over time.

- Extract the SPR curve (reflectivity vs. angle,

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The complete workflow, from sample preparation to data analysis, is summarized below.

Performance Validation and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The dynamic baseline algorithm's effectiveness is demonstrated by its performance against common noise sources. The table below summarizes key benchmarks.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Dynamic Baseline Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Key Feature | Performance Metric | Result / Advantage | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Dynamic Baseline | Fixed area ratio (λ) |

Insensitivity to correlated noise/drift | Mathematically exact compensation for optical power fluctuations. | [24] |

| PSO-Optimized Dynamic Baseline | Optimized params (β, m, λ) with Particle Swarm Optimization | Fitting degree (R²) in sucrose solution exp. | 0.9963 (Superior predictive ability) | [12] |

| PSO-Optimized Dynamic Baseline | Optimized params (β, m, λ) with PSO | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 1.78 | [12] |

Fixed m Method |

Fixed number of points below baseline | Parameter dominance study | Identified as most effective single parameter. | [12] |

Advanced Implementation: Swarm Intelligence Optimization

For systems requiring maximum accuracy, the dynamic baseline parameters can be automatically optimized using metaheuristic algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO).

- Objective: Find the optimal parameter combination

(β, m, λ)that defines the best dynamic baseline for a given SPR reflection spectrum [12]. - Process: PSO treats each parameter set as a particle. Particles "fly" through the parameter space, iteratively adjusting their positions based on their own experience and the swarm's best-found solution, converging on the global optimum [12].

- Performance: In experimental validations, the PSO-optimized dynamic baseline method achieved a superior fitting degree (

R² = 0.9963) and low error (RMSE = 1.78) when measuring sucrose solution concentrations. It also demonstrated the best tracking ability and optimization speed compared to other metaheuristic algorithms [12].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Mitigating Bulk Shift: A large, square-shaped response at injection start/end indicates a bulk shift caused by refractive index (RI) differences between the running buffer and analyte sample. While reference subtraction helps, the most effective strategy is to match buffer components exactly, or use additives like BSA (1%) or Tween 20 at low concentrations to stabilize proteins without causing significant RI mismatch [3].

- Minimizing Non-Specific Binding (NSB): If the analyte interacts with the sensor surface itself, it inflates the response. To reduce NSB:

- Adjust buffer pH to the protein's isoelectric point.

- Increase salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) to shield charge-based interactions.

- Use a different sensor chemistry to avoid opposite charges between the surface and analyte [3].

- Addressing Mass Transport Limitation: If the analyte diffusion to the surface is slower than its binding rate, kinetics become limited by mass transport. This manifests as a linear, non-curving association phase in the sensorgram. To test, run the assay at different flow rates; if the observed association rate (

k_a) increases with higher flow rates, the system is mass transport limited [3].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a well-established, label-free technique for biomolecular interaction analysis, generating thousands of publications each year [26]. A fundamental challenge in SPR sensing is that the evanescent field extends hundreds of nanometers from the surface—far beyond the thickness of typical analytes like proteins (2-10 nm) [26]. This physical characteristic means that when molecules are injected, even those that do not bind to the surface will generate a significant response due to their presence in solution. This "bulk response" or "bulk refractive index effect" occurs because of the difference in refractive index (RI) between the running buffer and the analyte sample [3] [27].

The bulk response problem has haunted SPR users for decades, as it complicates the differentiation between signals originating from actual surface binding and those arising merely from molecules in solution [26]. This effect is particularly pronounced when high analyte concentrations are necessary for probing weak interactions or when complex samples with varying RI are injected [26]. Arguably, the bulk response effect is a major reason why conclusions in many SPR publications may be questionable [26]. Proper compensation for these effects through reference channel subtraction is therefore essential for obtaining accurate binding data.

Theoretical Foundation of Bulk Response Correction

Physical Basis of Bulk Effects

The bulk response in SPR manifests as an immediate shift in the sensorgram at the beginning and end of analyte injection, often creating a characteristic 'square' shape [3]. These shifts may be positive or negative, depending on whether the RI of the analyte solution is higher or lower than that of the running buffer [3]. The magnitude of the bulk response is directly proportional to the RI difference between the solutions, with every 1 mM change in salt concentration generating approximately a 10 RU bulk difference [27].

The evanescent field decay length in SPR typically exceeds the size of most biological analytes, meaning that signals from non-bound molecules in solution contribute significantly to the total measured response [26]. This effect becomes particularly problematic when studying weak interactions requiring high analyte concentrations or when working with complex samples that have inherently different refractive indices from the running buffer.

Principles of Reference Channel Subtraction

Reference subtraction serves to compensate for bulk refractive index differences between flow buffer and analyte sample, in addition to compensating for some non-specific binding to the sensor chip [21]. The fundamental principle involves using a reference surface that ideally experiences the same bulk effects as the active surface but lacks the specific binding activity.

There are two primary types of referencing in SPR analysis [28]:

- Blank surface referencing: Corrects for bulk effect and nonspecific binding using either an empty surface or one coated with an irrelevant molecule.

- Blank buffer referencing: Corrects for baseline drift resulting from changes to the ligand surface itself.

When combined, these approaches implement the "double referencing" strategy that significantly enhances data quality by compensating for both bulk effects and instrumental drift [21] [28].

Table 1: Types of Reference Surfaces and Their Applications

| Reference Type | Composition | Primary Function | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank Surface | Bare sensor matrix or mock-immobilized surface | Subtract bulk RI change and non-specific binding to matrix | May not perfectly match hydration or exclusion properties of active surface |

| Iso-type Control | Immobilized irrelevant molecule with similar properties | Subtract non-specific binding to ligand chemistry | Requires identification of suitable control molecule |

| Mutant Target | Non-functional variant of the target | Control for specific binding while maintaining surface properties | Requires protein engineering |

| Streptavidin Surface | Bare streptavidin without biotinylated ligand | Standard for capture systems | Differences in matrix exclusion volume |

Experimental Design for Effective Reference Subtraction

Reference Surface Selection

The choice of an appropriate reference surface is critical for effective bulk response correction. Several approaches are commonly employed, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

For protein interaction studies, a blank surface functionalized with the same chemistry as the active surface but without the specific ligand is often used [21]. For RNA-small molecule interactions, research shows that using a mutant or noncognate RNA as a reference effectively controls for nonspecific electrostatic interactions that often complicate analysis of weak binders [29]. This approach enforces target specificity by subtracting signals arising from non-specific interactions while preserving those from specific binding events.

The unique 6×6 experimental configuration of systems like the ProteOn XPR36 offers advanced referencing options such as interspot referencing, which uses interval surfaces adjacent to interaction spots rather than consuming valuable interaction surfaces [28]. This approach enhances referencing quality through immediate proximity to the interaction spots while conserving experimental capacity.

Buffer Matching Strategies

Proper buffer matching between running buffer and analyte samples is the first line of defense against significant bulk effects [3]. When analytes are stored in different buffers, dialysis against the running buffer or buffer exchange using size exclusion columns is recommended [27]. For small molecules dissolved in DMSO, it is essential to match DMSO concentrations exactly between sample and running buffers, as even small differences (e.g., 1% vs. 0.95% DMSO) can cause significant bulk responses [27].

Table 2: Common Buffer Components Causing Bulk Shifts and Mitigation Strategies

| Component | Typical Concentration | Bulk Effect Severity | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 1-10% | High | Exact matching ±0.1%; dialysis against running buffer with DMSO |

| Glycerol | 5-50% | High | Dialysis or buffer exchange; consider alternative stabilizers |

| Sucrose | 100-500 mM | Medium | Dilution in running buffer; consider lower concentrations |

| High Salt | >500 mM NaCl | Medium | Dialysis; use running buffer for serial dilutions |

Experimental Controls and Calibration

Incorporating appropriate controls validates the reference subtraction process. Injection of a series of buffer blanks (zero analyte concentration) corrects for drift and minor differences between reference and active channels [21]. For systems with high refractive index cosolvents like DMSO, excluded volume correction (EVC) calibration may be necessary when reference and active surfaces respond differently to changes in ionic strength or organic solvent concentration [21] [27]. This calibration involves creating a standard curve with known DMSO concentrations to correct for differential displacement volumes between surfaces with different ligand densities.

Step-by-Step Protocol for Reference Channel Subtraction

Surface Preparation

- Immobilize the ligand on the active flow cell using standard coupling procedures appropriate for your molecule (e.g., amine coupling, thiol coupling, or capture systems) [21].

- Prepare the reference surface using one of the following approaches [29] [28]:

- For blank surface reference: Activate and deactivate the surface without ligand immobilization.

- For control molecule reference: Immobilize a non-binding control molecule (e.g., mutant protein, non-cognate RNA) at a density similar to the active surface.

- For capture systems: Prepare the reference surface with the capture molecule (e.g., streptavidin) but without the ligand.

- Condition the surfaces with 3-5 injections of running buffer to establish stable baselines before analyte injections [29].

Data Collection Parameters

- Set the flow rate between 20-30 μL/min to minimize mass transport effects while maintaining adequate sample delivery [26] [29].

- For multi-cycle kinetics, program analyte injections in increasing concentration order, starting with a blank buffer injection [29].

- Use association phases of 2-5 minutes and dissociation phases of 4-10 minutes, adjusted based on the kinetic properties of your interaction [29] [28].

- Include periodic buffer injections throughout the run to monitor baseline stability and drift [28].

Data Processing Workflow

The following workflow illustrates the complete data processing procedure for SPR data, highlighting the role of reference subtraction within the broader context:

The reference subtraction process itself consists of two sequential steps that can be visualized as follows:

Implementation of Double Referencing

Perform blank surface referencing [28]:

- Subtract the sensorgram from the reference flow cell (blank surface + analyte solution) from the active surface sensorgram.

- This step removes the bulk refractive index effect and non-specific binding to the sensor matrix.

Perform blank buffer referencing [21] [28]:

- Subtract the sensorgram from the blank buffer injection (ligand surface + blank buffer) from all analyte injection sensorgrams.

- This step corrects for baseline drift resulting from changes to the ligand surface over time.

Apply excluded volume correction when necessary [21] [27]:

- Use when significant differences in ligand density cause differential response to cosolvents.

- Generate a calibration curve using control solutions with known refractive indices.

- Apply the calibration to correct for excluded volume differences between reference and active surfaces.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Spikes After Reference Subtraction

Spikes at the beginning and end of injections after reference subtraction indicate phase misalignment between channels, particularly when flow channels are in series [27]. This occurs because the sample arrives at each channel at slightly different times. To resolve this:

- Improve alignment of curves in the X-direction by carefully aligning the injection start times [21] [27].

- Use instruments with inline reference subtraction when available, as this minimizes timing discrepancies [27].

- Ensure better buffer matching to reduce the magnitude of bulk shifts, making timing differences less impactful [27].

Incomplete Bulk Compensation

When bulk effects remain after reference subtraction, consider these solutions:

- Verify that the reference surface closely matches the active surface in terms of matrix properties and ligand density [26].

- For systems with high refractive index cosolvents like DMSO, implement excluded volume correction [21] [27].

- Consider alternative reference strategies, such as using a mutant target rather than a blank surface [29].

- Explore advanced bulk correction methods like PureKinetics (BioNavis) that measure bulk refractive index in real-time [26] [27].

Persistent Non-Specific Binding

When non-specific binding (NSB) persists after reference subtraction:

- Increase salt concentration in the running buffer (e.g., additional 50-150 mM NaCl) to shield charge-based interactions [3].

- Add non-ionic surfactants like Tween-20 (typically 0.05%) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [3] [29].

- Include protein blocking additives such as BSA (1%) in analyte solutions during runs (but not during immobilization) [3].

- Adjust buffer pH to the isoelectric point of the analyte to minimize electrostatic interactions [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SPR Reference Subtraction Experiments

| Reagent/Chip Type | Function in Reference Subtraction | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Series S Sensor Chip SA | Streptavidin-coated for capture immobilization | Enables uniform ligand density between active and reference surfaces through biotin capture [29] |

| CM5 Carboxylated Dextran Chip | Versatile matrix for amine coupling | Most common chip type; allows creation of blank reference by activating/deactivating without ligand [21] |

| HEPES-buffered Saline (HBS) | Standard running buffer | Low UV absorbance, good buffering capacity; 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 typical [29] |

| Tween-20 (0.05%) | Non-ionic surfactant | Reduces NSB by disrupting hydrophobic interactions; standard additive in running buffers [3] [29] |

| DMSO | Cosolvent for small molecules | Match concentration exactly between sample and running buffer (±0.1%); causes significant bulk shifts [27] |

| BSA (1%) | Protein blocking agent | Add to analyte solutions (not during immobilization) to reduce NSB; use fatty-acid free grade [3] |

Advanced Applications and Method Extensions

RNA-Small Molecule Interaction Studies

For RNA-small molecule interactions, standard referencing approaches may be insufficient due to significant nonspecific electrostatic interactions [29]. Implementing a mutant or noncognate RNA reference enables subtraction of nonspecific binding contributions, allowing accurate measurement of specific binding affinities ranging from nanomolar to millimolar [29]. This approach has been validated for riboswitch RNAs and low-molecular-mass fragment ligands, demonstrating reliable discrimination between specific and nonspecific binding.

Reference-Free Bulk Correction Methods

Emerging methodologies offer bulk response correction without requiring a separate reference channel. One recently developed physical model determines bulk response contribution using the total internal reflection (TIR) angle response as the only input [26]. This method accounts for the thickness of the receptor layer on the surface and has been shown to reveal interactions that might otherwise be obscured by bulk effects, such as the weak affinity between poly(ethylene glycol) brushes and lysozyme (KD = 200 μM) [26].

High-Throughput Screening Applications

In fragment-based screening where weak binders are common, reference subtraction strategies are critical for distinguishing true binding from false positives. Using control surfaces with mutated binding sites or irrelevant proteins enhances confidence in identifying specific binding events [29]. The efficiency of SPR combined with robust referencing makes it particularly valuable for screening applications where material consumption and throughput are significant considerations.

Proper implementation of reference channel subtraction is essential for obtaining accurate SPR data by effectively compensating for bulk refractive index effects. The double referencing approach, combining blank surface and blank buffer subtraction, provides a robust framework for distinguishing specific binding from non-specific effects. Careful experimental design—including appropriate reference surface selection, precise buffer matching, and validation controls—ensures reliable data interpretation. As SPR applications expand to include more challenging interactions like RNA-small molecule binding and weak affinities, advanced referencing strategies continue to evolve, enhancing the technique's utility in fundamental research and drug discovery.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has established itself as a cornerstone technology for real-time, label-free monitoring of biomolecular interactions across diverse fields including drug discovery, diagnostic development, and fundamental biological research [18] [30]. The core measurement in SPR is the detection of changes in the refractive index at the sensor surface, which is expressed in resonance units (RU). However, not all changes in RU originate from the specific biomolecular interaction of interest; significant signal contributions can arise from instrumental noise, bulk refractive index effects from buffer composition, and non-specific binding [28] [15]. These confounding signals can obscure true interaction data and compromise kinetic and affinity analyses.

Referencing strategies are therefore critical for isolating the specific binding signal. Double referencing has emerged as a gold-standard methodology that systematically removes these non-specific contributions through a two-step correction process [28]. This technique combines blank surface referencing (addressing bulk effects and non-specific binding) with blank buffer referencing (addressing baseline drift and instrumental artifacts). The power of double referencing lies in its comprehensive approach to signal purification, enabling researchers to extract high-quality interaction data from complex experimental systems. For researchers working within the context of SPR baseline correction methodologies, mastering double referencing is essential for producing publication-quality data with enhanced reliability and accuracy.

Theoretical Foundation of Double Referencing

The Need for Signal Correction in SPR

SPR biosensors detect changes in mass concentration at the sensor surface by measuring refractive index variations. Unfortunately, the detected signal represents a composite of several factors: (1) specific binding between ligand and analyte; (2) non-specific binding of analyte to the sensor matrix or immobilized ligand; (3) bulk refractive index changes resulting from differences in composition between running buffer and analyte solution; and (4) instrumental drift and optical artifacts [28] [15]. Without appropriate correction, these non-specific effects can lead to significant data misinterpretation. For instance, buffer mismatches – where the analyte solution has different salt or co-solvent composition than the running buffer – can produce substantial signal jumps that mimic or mask binding events [31]. One study noted that a mismatch of just 1 mM NaCl can generate a signal shift of approximately 20 RU on a carboxylated dextran sensor chip [31].

Components of Double Referencing