Advanced Sol-Gel Encapsulation of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Enhancing Stability for Biomedical Sensing and Drug Delivery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of sol-gel methods for the surface encapsulation of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical technology for stabilizing these highly luminescent but fragile nanomaterials in...

Advanced Sol-Gel Encapsulation of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Enhancing Stability for Biomedical Sensing and Drug Delivery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of sol-gel methods for the surface encapsulation of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical technology for stabilizing these highly luminescent but fragile nanomaterials in aqueous and biological environments. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational chemistry of silica coating, detail advanced methodological strategies for single-particle level encapsulation, address key challenges in biocompatibility and process optimization, and validate performance through comparative analysis of stability and functionality. The scope extends from fundamental synthesis to specific applications in biosensing, bioimaging, and targeted drug delivery, offering a practical guide for implementing these advanced nanomaterial systems in biomedical research and development.

The Chemistry and Imperative of Sol-Gel Encapsulation for Perovskite Quantum Dots

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly lead halide perovskites with the chemical formula ABX₃ (where A = CH₃NH₃, CH₅N₂, Cs; B = Pb, Sn; C = I, Br, Cl), have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconductor nanomaterials for optoelectronic applications [1]. These materials exhibit exceptional optoelectronic properties, including tunable bandgaps, high light-absorption efficiency, narrow emission linewidths, high color purity, and remarkably high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) approaching 100% in some cases [1] [2]. Their unique defect-tolerant structure enables outstanding performance even without perfect surface passivation, making them superior to traditional semiconductor QDs like CdSe and PbS for many applications [1].

Despite these promising characteristics, PQDs face critical stability challenges that hinder their commercial application. Their ionic crystal structure and highly dynamic ligand bonding make them susceptible to degradation under environmental factors including moisture, oxygen, heat, and UV light [1]. This degradation manifests as rapid deterioration of optical properties, structural decomposition, and eventual loss of functionality. Consequently, developing effective stabilization strategies—particularly surface encapsulation via sol-gel methods—has become a central focus in PQD research to bridge the gap between their outstanding potential and practical application.

Quantifying PQD Performance: PLQY and Stability Metrics

The performance of perovskite quantum dots is primarily evaluated through photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and various stability metrics. PLQY represents the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed, directly indicating the material's emission efficiency. Stability is measured through retention of PL intensity under environmental stressors like heat, moisture, and prolonged storage.

Table 1: Reported PLQY Values and Stability Performance of Various PQD Systems

| PQD System | Stabilization Method | Initial PLQY (%) | Stability Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ | Short-chain n-amylamine (ALA) ligand | 91.3% | 56% PL retention after 72h in air; Higher thermal stability | [3] |

| CsPbX₃@SiO₂ | Sol-gel SiO₂ encapsulation | 86.7% | Unchanged PL after 6 months in water; Stable in boiling water for 14h | [4] |

| MAPbBr₃@S-COF | Thiomethyl-functionalized COF encapsulation | N/A | Exceptional water stability >1 year | [5] |

| CsPbBr₃ | Acetate/2-HA ligand engineering | 99% | Enhanced reproducibility & ASE performance | [2] |

| ALA-CsPbBr₃ | Short-chain ligand passivation | N/A | Higher activation energy (570.8 meV) for thermal stability | [3] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of PQD Stabilization Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sol-gel Encapsulation | Dense silica shell blocks environmental factors | Exceptional long-term stability; Maintains high PLQY | Requires careful control of hydrolysis conditions |

| Ligand Engineering | Surface passivation with stronger-binding ligands | Improved charge transport; Enhanced PLQY | May require complex synthesis optimization |

| MOF/COF Encapsulation | Nanoconfinement in functionalized porous matrices | Synergistic protection; Functionalizable pores | Intricate post-modification processes possible |

| Glass Encapsulation | Melt quenching in inorganic oxide glass | Extreme thermal/chemical resistance | High temperature processing required |

Sol-Gel Encapsulation Protocols for PQDs

Sol-Gel SiO₂ Encapsulation of CsPbX₃ NCs

This protocol describes a solid-state reaction method using sol-gel derived porous SiO₂ as reactors to create exceptionally stable CsPbX₃@SiO₂ composites, adapted from published procedures [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Sol-gel SiO₂ powders: Synthesized via traditional sol-gel processes

- Cesium halides: CsCl (99.9%), CsBr (99.9%), CsI (99.9%)

- Lead halides: PbCl₂ (99%), PbBr₂ (99%), PbI₂ (99%)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH): For etching treatment

- Solvents: High-purity water, ethanol

Experimental Procedure:

Precursor Preparation:

- Grind stoichiometric ratios of cesium halide and lead halide precursors with sol-gel SiO₂ powders using a mortar and pestle

- Ensure homogeneous mixing for uniform distribution of growth sites within the SiO₂ matrix

High-Temperature Treatment:

- Transfer the mixture to an alumina crucible

- Heat in a muffle furnace at 600-800°C in air for 2-4 hours

- The high temperature facilitates the growth of CsPbX₃ NCs within the SiO₂ matrix while simultaneously densifying the silica structure

Alkali Etching:

- Treat the resulting SiO₂/CsPbX₃ glass composites with NaOH solution (concentration: 0.1-0.5M)

- Etching time: 30-60 minutes with gentle stirring

- This process removes excess silica, leaving a thin, dense SiO₂ shell around individual CsPbX₃ NCs

Washing and Collection:

- Centrifuge the resulting CsPbX₃@SiO₂ composites at 8000-10000 rpm for 5 minutes

- Wash with deionized water and ethanol to remove residual alkali

- Dry at 60-80°C for 12 hours before characterization

Critical Parameters:

- The SiO₂:precursor ratio controls NC size and distribution

- Heating rate (5-10°C/min) affects nucleation density

- Alkali concentration determines final shell thickness

In Situ Passivation with Short-Chain Ligands

This protocol employs n-amylamine (ALA) as a short-chain surface ligand to replace conventional oleylamine (OLA) for enhanced stability and optical properties [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%)

- n-Amylamine (ALA, 90%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%)

- Lead bromide (PbBr₂, 99%)

- 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%)

- Toluene

Experimental Procedure:

Cesium Oleate Precursor:

- Combine 0.08g Cs₂CO₃ with 0.25mL OA and 3mL ODE in a 100mL three-neck flask

- Heat to 120°C under N₂ atmosphere with stirring until complete dissolution

- Maintain at 100°C until use to prevent solidification

Perovskite Precursor Solution:

- Dissolve 0.069g PbBr₂ in 5mL ODE in a separate flask

- Add optimized amounts of OA (0.5mL) and ALA (0.4mL)

- Heat to 120°C under N₂ with stirring until clear

QD Synthesis:

- Raise the temperature of the PbBr₂ solution to 180°C

- Rapidly inject 0.4mL of the preheated cesium oleate solution

- Immediately cool in an ice-water bath after 5-10 seconds to terminate growth

Purification:

- Centrifuge the crude solution at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes

- Redisperse the precipitate in toluene for further characterization

Optimization Notes:

- ALA content should be optimized between 0.1-0.8mL for maximum PLQY

- Reaction time at high temperature critically controls QD size

- Excess ALA can lead to decreased PLQY due to insufficient surface passivation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Encapsulation

| Reagent/Chemical | Function | Application Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | SiO₂ precursor in sol-gel processes | Hydrolyzes to form silica network; concentration controls pore size | [1] |

| n-Amylamine (ALA) | Short-chain surface ligand | Replaces OLA for better stability & charge transport | [3] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand & coordination agent | Synergizes with amines for effective surface passivation | [6] [3] |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium precursor for all-inorganic PQDs | Requires complete conversion to cesium oleate | [3] [2] |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead and halide source | Stoichiometry controls final composition & optical properties | [3] |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain ligand | Stronger binding affinity than OA; suppresses Auger recombination | [2] |

| Acetate Salts (AcO⁻) | Dual-functional precursor additive | Enhances precursor purity & acts as surface passivator | [2] |

The integration of sol-gel encapsulation methodologies with advanced ligand engineering represents a promising pathway for overcoming the critical stability challenges of perovskite quantum dots while maintaining their exceptional PLQY. The protocols outlined herein provide reproducible methods for creating stable, high-performance PQDs suitable for further research and development. As these stabilization technologies mature, PQDs are poised to enable transformative advances in optoelectronics, photonics, and biomedical applications. Future research directions should focus on optimizing the interface chemistry between PQDs and encapsulation matrices, developing lead-free alternatives with comparable performance, and scaling these laboratory protocols to industrial production.

The sol-gel process is a versatile chemical synthesis technique for fabricating ceramic materials, particularly silica networks, through the preparation of a sol, its gelation, and subsequent removal of the solvent [7]. This method provides exceptional control over material composition and microstructure at the molecular level, making it particularly valuable for research applications including the surface encapsulation of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) [7]. The process fundamentally relies on two consecutive classes of chemical reactions: hydrolysis and condensation, typically starting from metal alkoxide precursors such as tetramethoxysilane (TMOS) or tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) [7].

A key advantage of the sol-gel route for PQD encapsulation is its ability to form a robust, inorganic matrix under mild processing conditions, which can protect the sensitive PQD cores from environmental degradation factors such as moisture, oxygen, and heat without compromising their optical properties. The resulting silica network can be tailored to specific requirements by controlling various synthesis parameters [7].

Fundamental Reactions and Mechanism

The formation of the silica network via the sol-gel process is governed by two principal chemical reactions.

Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis initiates the sol-gel process by replacing alkoxide groups (OR) with hydroxyl groups (OH) through the action of water [7].

General Reaction:

≡Si-OR + H₂O ⇔ ≡Si-OH + ROH

This reaction generates reactive silanol groups (Si-OH) from the precursor molecules. The rate and extent of hydrolysis are critical as they determine the number of available sites for the subsequent condensation step.

Condensation

Condensation follows hydrolysis, linking the hydrolyzed species through the formation of siloxane bonds (Si-O-Si) with the liberation of water or alcohol [7].

General Reactions:

- Alcohol Condensation:

≡Si-OH + RO-Si≡ ⇔ ≡Si-O-Si≡ + ROH - Water Condensation:

≡Si-OH + HO-Si≡ ⇔ ≡Si-O-Si≡ + H₂O

These condensation reactions create the three-dimensional silica network that constitutes the final gel. The relative rates of hydrolysis and condensation, and the pathway of condensation (water or alcohol), profoundly impact the microstructure, porosity, and mechanical properties of the resulting gel [7].

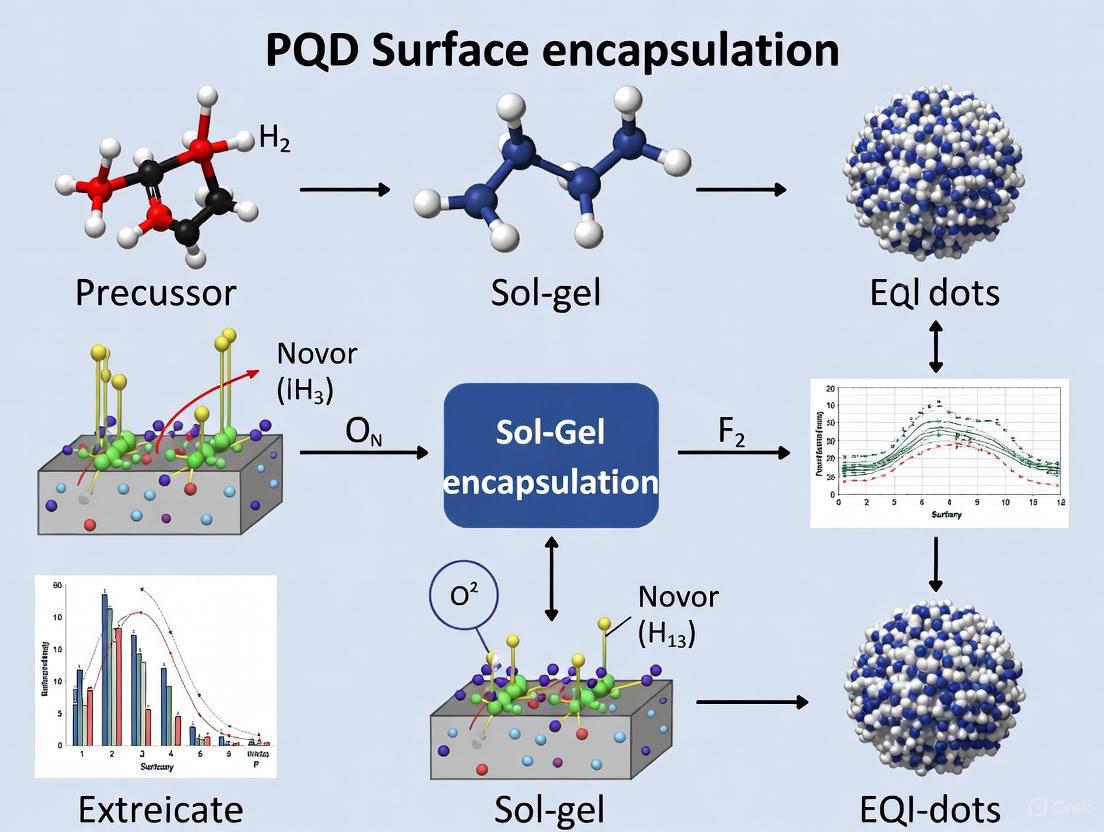

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from precursor to final encapsulated product, highlighting the key stages and the decisions that influence the final material properties.

Critical Parameters Governing Silica Network Formation

The properties of the final silica network are highly sensitive to a range of processing parameters. Understanding and controlling these variables is essential for designing a silica matrix suitable for PQD encapsulation.

Table 1: Key Sol-Gel Processing Parameters and Their Impact on Final Material Properties

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Silica Network & Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Type (pH) | Use of acid (e.g., HCl) or base (e.g., NH₄OH) to catalyze reactions [7] [8]. | Acid-catalysis: Promotes linear polymer chains, resulting in gels with lower connectivity, smaller pores, and higher specific surface area. Base-catalysis: Favors the formation of highly branched, colloidal particles, leading to gels with higher network connectivity and larger, more uniform pores [7] [8]. |

| Water to Alkoxide Ratio (Rw) | Molar ratio of water (H₂O) to the silicon alkoxide precursor [8]. | Increasing Rw generally decreases network connectivity and increases the bioactivity/dissolution rate of the glass. This effect is more pronounced in glasses with initially high network connectivity (e.g., base-catalyzed) [8]. For PQD encapsulation, this can be leveraged to control matrix stability and ion release. |

| Precursor Type & Concentration | The specific alkoxide used (e.g., TMOS, TEOS) and its amount in the solvent [7]. | Influences the rate of hydrolysis and condensation, the density of the final gel, and the pore size distribution. Higher precursor concentrations typically lead to faster gelation times and denser networks [7]. |

| Solvent | The liquid medium (e.g., ethanol, methanol) in which reactions occur [7]. | Affects precursor solubility, reaction rates, and the structure of the gel network during drying. It also influences the stability of suspended PQDs during incorporation. |

| Temperature | The temperature at which hydrolysis, condensation, and aging are performed [7]. | Higher temperatures accelerate all reaction rates (hydrolysis and condensation), which can shorten processing time but may lead to a less homogeneous network or damage sensitive PQDs. |

| Aging Time & Conditions | The period the gel is left in its solvent after gelation [7]. | Aging (syneresis) strengthens the gel network through continued condensation and localized reprecipitation, which thickens interparticle necks and reduces porosity. This enhances mechanical strength, reducing the risk of cracking during drying [7]. |

The interplay of these parameters directly dictates the structural properties of the gel, which in turn governs its performance as an encapsulation matrix. The following diagram maps how these key parameters influence the reaction pathway and the resulting gel structure.

Experimental Protocols for Silica-Based Sol-Gel Encapsulation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for forming a silica network via the sol-gel process, adaptable for PQD encapsulation.

Base-Catalyzed Synthesis of Silica Gels for High Connectivity Networks

Objective: To synthesize a silica gel with high network connectivity and uniform pore structure suitable for creating a stable, protective barrier around PQDs.

Materials:

- Precursor: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, ≥99%)

- Solvent: Anhydrous Ethanol

- Catalyst: Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH, 28-30%)

- Water: Deionized Water

Procedure:

- Hydrolysis (Sol Formation):

- In a sealed container, mix TEOS and ethanol in a molar ratio of

1 : 3. - Add deionized water with a water-to-alkoxide ratio (Rw) of

2 : 1under constant stirring. - Initiate the hydrolysis by adding NH₄OH to adjust the solution to a pH of

10-11. - Stir the mixture vigorously at room temperature for

60 minutesto ensure complete hydrolysis. The solution will remain clear.

- In a sealed container, mix TEOS and ethanol in a molar ratio of

PQD Incorporation (at the Sol Stage):

- After the hydrolysis step, a stabilized dispersion of PQDs in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane or toluene) can be introduced.

- Note: The PQDs must be compatible with the current chemical environment. Slow, dropwise addition under vigorous stirring is critical to avoid agglomeration or instantaneous precipitation.

Condensation and Gelation:

- Seal the container and allow the mixture to stand undisturbed at

40°Cfor gelation. - Gelation typically occurs within

2-4 hours, marked by a sharp increase in viscosity and the loss of fluidity, forming a wet gel.

- Seal the container and allow the mixture to stand undisturbed at

Aging:

- Once gelation is complete, age the wet gel by immersing it in the mother liquor (the excess solvent) for

24 hoursat40°C. - This step strengthens the gel network, enhancing its resistance to cracking during the subsequent drying step [7].

- Once gelation is complete, age the wet gel by immersing it in the mother liquor (the excess solvent) for

Drying:

- Carefully remove the aged gel from the mother liquor.

- Dry the gel slowly under ambient conditions for

48 hours, followed by further drying in an oven at80°Cfor24 hoursto remove residual solvents, forming a xerogel. - For ultra-high porosity and low density, supercritical drying (e.g., with CO₂) can be employed to produce an aerogel, which avoids the collapse of the pore structure due to capillary forces [7].

Acid-Catalyzed Synthesis for Fine-Tuned Microstructure

Objective: To synthesize a silica gel with a finer, more polymeric microstructure, offering potentially better barrier properties for smaller PQDs.

Modifications to the Base Protocol:

- Catalyst: Use Hydrochloric Acid (HCl, 0.1 N) instead of NH₄OH.

- Procedure: Adjust the solution to a pH of

2-3using HCl. The hydrolysis and condensation will proceed more slowly. The gelation time will be significantly longer, potentially taking24-72 hours. The resulting gel will have a denser microstructure with smaller pores compared to the base-catalyzed gel [7] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sol-Gel Silica Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function in the Sol-Gel Process | Example & Notes for PQD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Alkoxide Precursor | The primary source of Si atoms for building the silica network [7]. | Tetramethoxysilane (TMOS): Highly reactive. Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS): More common, slower reaction rate allows better control. Purity ≥99% is recommended for reproducible results. |

| Co-precursors / Dopants | Modify the network properties or introduce functionality [8]. | 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate (MPTMOS): Introduces organic, polymerizable methacrylate groups for hybrid organic-inorganic matrices [9]. Titanium isopropoxide: Dopant ion (Ti⁴⁺) that increases network connectivity and can impart bactericidal properties [8]. |

| Catalyst | Controls the rates of hydrolysis and condensation reactions [7] [8]. | HCl (Acid): Produces linear, polymeric gels with small pores. NH₄OH (Base): Produces particulate, highly connected gels with larger pores. |

| Solvent | Dissolves precursors and facilitates homogeneous mixing. | Anhydrous Ethanol: Most common solvent for TEOS/TMOS. Must be anhydrous to prevent premature, uncontrolled hydrolysis before catalyst addition. |

| Porogen | A substance used to generate and control porosity in the gel. | Glycerol, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG). Added to the sol, they are later removed during drying/washing to create tailored pore architectures [9]. |

| Photo-initiator | For UV-polymerizable hybrid sol-gel systems. | Irgacure 1800 (5 wt% of final solution). Used with monomers like MPTMOS to enable photopolymerization, allowing precise spatial patterning of the monolith within a device [9]. |

Advanced Applications and Characterization in PQD Encapsulation

The sol-gel-derived silica matrix serves as an ideal host for PQDs, enhancing their stability for applications in displays, lighting, and photovoltaics. The porous nature of the xerogel or aerogel can be leveraged for sensor applications, where the analyte diffuses through the pores to interact with the encapsulated PQDs [7] [10].

For the successful implementation of sol-gel encapsulation, characterization is paramount. Key techniques include:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): To visualize the microstructure, homogeneity, and pore architecture of the silica network and the distribution of PQDs within it [9].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Can be used to characterize pore sizes in saturated monoliths and study thermal transitions [9].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): To confirm the amorphous nature of the silica matrix and monitor the crystalline phase of encapsulated PQDs or any crystalline dopant phases (e.g., TiO₂) [8] [11].

The inherent versatility of the sol-gel process, allowing for molecular-level control over composition and microstructure, makes it a powerful tool for advancing the stability and application range of perovskite quantum dots.

Why Silica? Exploring the Protective Role of SiO2 Matrices for PQDs

All-inorganic perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I), have emerged as promising materials for optoelectronic applications due to their high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission linewidths, and tunable bandgaps. However, their commercial deployment is hindered by inherent instability under environmental conditions such as moisture, oxygen, and heat. This application note elucidates the fundamental role of silica (SiO2) matrices in mitigating these vulnerabilities through sol-gel based encapsulation strategies. We detail the protective mechanisms of SiO2, provide quantitative performance comparisons of various encapsulation architectures, and present standardized protocols for synthesizing silica-encapsulated PQDs, specifically tailored for researchers and scientists in the field.

The Protective Imperative for PQDs

Perovskite quantum dots represent a significant advancement in semiconductor nanocrystals, yet their susceptibility to environmental degradation poses a major challenge for practical applications. When exposed to ambient conditions, unprotected PQDs undergo rapid surface degradation, leading to defect accumulation that quenches photoluminescence and degrades performance [12] [13]. The inherent ionic nature of perovskite crystals makes them particularly vulnerable to moisture, oxygen, and thermal stress [14]. Furthermore, at high concentrations or during processing, PQDs tend to aggregate, creating large domains that impair heat dissipation, increase non-radiative recombination, and cause undesirable color shifts in emission spectra [12]. These limitations necessitate robust encapsulation strategies that shield PQDs from environmental factors while preserving their exceptional optical properties.

Why Silica? Fundamental Protective Mechanisms

Silica matrices offer a unique combination of properties that address the specific vulnerabilities of PQDs. The sol-gel derived silica encapsulation provides multiple protective mechanisms that operate synergistically to enhance PQD stability.

Chemical and Physical Shielding

The dense, amorphous network of SiO2 creates an effective physical barrier against environmental degradants. Silica's exceptionally low oxygen permeability compared to polymeric materials [14] significantly reduces oxidative degradation of PQD surfaces. This inorganic glassy matrix physically impedes the penetration of moisture and oxygen, the primary agents of PQD decomposition [12] [13]. The stable, inert nature of silica provides chemical resistance to the encapsulated PQDs, shielding them from corrosive gases and solvents that would otherwise degrade the perovskite crystal structure.

Nanoconfinement and Surface Passivation

The sol-gel process enables the entrapment of delicate PQDs within the inner porosity of silica matrices, resulting in pronounced chemical and physical stabilization [15]. This nanoconfinement effect restricts molecular mobility and reduces the diffusion of degradants to the PQD surface. Additionally, silica encapsulation facilitates surface passivation by reducing the number of surface defects and unpassivated sites on PQDs, which are common sources of non-radiative recombination [16]. The formation of a stable interface between the PQD surface and the silica matrix through judicious use of silane coupling agents further enhances this passivation effect, promoting efficient radiative recombination and improving luminescence efficiency [14].

Thermal and Mechanical Stability

Silica matrices provide exceptional thermal protection, broadening the practical utilization of thermally sensitive PQDs [15]. The silica shell acts as a thermal barrier, dissipating heat and preventing thermal degradation of the encapsulated PQDs. Furthermore, the rigid silica framework enhances mechanical stability, protecting PQDs from aggregation and coalescence during processing and operation [12]. This mechanical robustness is particularly valuable for application environments that involve mechanical stress or repeated thermal cycling.

Quantitative Performance Enhancement

The following tables summarize the measurable improvements in PQD performance achieved through various silica encapsulation strategies, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Silica-Encapsulated PQDs vs. Unprotected PQDs

| Encapsulation Strategy | PLQY (%) | Environmental Stability | Thermal Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unprotected CsPbBr₃ PQDs | ~70-80 | Retains <60% PL after 7 weeks | Significant degradation above 150°C | [16] |

| CsPbBr₃/s-MSNs@SiO₂ | 90.0 | Retains >95% PL after 7 weeks | Stable up to synthesis temperature | [16] |

| CsPbBr₃@Glass@ASG | ~88 | Retains 100% PL after 7 weeks | Improved thermal reversibility | [13] |

| CsPbBr₃@Glass@A | ~85 | Retains 90% PL after 7 weeks | Moderate improvement | [13] |

Table 2: Structural and Optical Properties of Silica Matrices for PQD Encapsulation

| Silica Matrix Property | Protective Benefit | Impact on PQD Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Low oxygen permeability | Reduces oxidative degradation | Prevents PL quenching and color shifts |

| Tunable porosity (2-10 nm) | Controls molecular diffusion | Enables size-selective protection |

| High optical transparency | Minimal light scattering | Maintains emission efficiency |

| Adjustable shell thickness | Optimizes protection vs. size | Balances stability and quantum confinement |

| Surface functionalization | Enhves compatibility | Improves interfacial adhesion and dispersion |

Silica Encapsulation Architectures and Workflows

Two principal approaches have emerged for encapsulating PQDs within silica matrices: in-situ hydrolysis and template-based encapsulation. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting the appropriate encapsulation methodology based on research objectives and PQD properties.

In-Situ Hydrolysis Methods

Stöber Method for Hydrophobic PQDs

The Stöber method, a base-catalyzed sol-gel process, is particularly suitable for hydrophobic PQDs stabilized with long-chain ligands [14]. This approach enables the preparation of silica nanoparticles containing dozens of encapsulated hydrophobic PQDs with precise control over shell thickness and morphology.

Experimental Protocol: Stöber Method for CsPbBr₃ PQDs

Reagents Required:

- CsPbBr₃ PQDs in toluene (1 mg/mL)

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, ≥99%)

- Ammonium hydroxide (28-30% NH₃ basis)

- Absolute ethanol

- (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) or other silane coupling agents

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Transfer 5 mL of CsPbBr₃ PQD solution to a 50 mL round-bottom flask.

- Add 20 mL absolute ethanol and mix thoroughly using magnetic stirring.

- Add 100 μL APTES as a coupling agent and stir for 15 minutes to promote surface functionalization.

- Introduce 200 μL TEOS and continue stirring for 30 minutes.

- Add 500 μL ammonium hydroxide catalyst to initiate the silica condensation reaction.

- Maintain continuous stirring at room temperature for 4-6 hours.

- Recover the silica-encapsulated PQDs by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Wash twice with ethanol to remove unreacted precursors.

- Redisperse in desired solvent for characterization or application.

Key Parameters:

- Molar ratio of TEOS:PQD surface area critically influences shell thickness

- Reaction temperature controls condensation rate and silica density

- APTES concentration affects interfacial adhesion and PLQY preservation

Reverse Microemulsion Method

The reverse microemulsion (water-in-oil) technique creates nanoreactors for silica encapsulation, offering superior control over particle size and morphology [12] [13].

Experimental Protocol: Reverse Microemulsion Encapsulation

Reagents Required:

- CsPbBr₃ PQDs in non-polar solvent

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS)

- Cyclohexane

- Surfactant (e.g., Triton X-100)

- Co-surfactant (e.g., n-hexanol)

- Ammonium hydroxide solution

- Acetone for precipitation

Procedure:

- Prepare the microemulsion by mixing 20 mL cyclohexane, 5 mL Triton X-100, and 5 mL n-hexanol.

- Add 500 μL of PQD solution and stir until uniformly dispersed.

- Introduce 100 μL of ammonium hydroxide solution (28-30%) to establish basic conditions.

- Slowly add 200 μL TEOS dropwise with continuous stirring.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 24 hours with gentle stirring.

- Break the microemulsion by adding acetone (1:2 v/v) to precipitate the encapsulated PQDs.

- Collect by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Wash with ethanol/acetone mixture (1:1) to remove surfactant residues.

- Redisperse in appropriate solvent for further use.

Template-Based Encapsulation Methods

Mesoporous Silica Nanosphere Encapsulation

Mesoporous silica nanospheres (MSNs) provide a structured host matrix for PQD incorporation, enabling high loading capacities while preventing aggregation.

Experimental Protocol: In-Situ Growth in Functionalized MSNs

Reagents Required:

- Surface-functionalized mesoporous silica nanospheres (s-MSNs)

- Cesium precursor (e.g., Cs₂CO₃)

- Lead precursor (e.g., PbBr₂)

- Ligands (oleic acid, oleylamine)

- Non-polar solvents (octadecene)

- TEOS for secondary encapsulation

- TMOS for secondary encapsulation

Procedure:

- Activate s-MSNs by heating at 120°C under vacuum for 2 hours to remove adsorbed moisture.

- Prepare precursor solution containing Cs₂CO₃ and PbBr₂ in octadecene with oleic acid and oleylamine ligands.

- Incubate s-MSNs in the precursor solution at 80°C for 4 hours to facilitate pore infiltration.

- Rapidly increase temperature to 180°C to initiate PQD nucleation within the mesopores.

- Maintain reaction for 10 minutes to allow crystal growth.

- Cool to room temperature and recover PQD-loaded MSNs by centrifugation.

- For enhanced protection, implement secondary SiO₂ encapsulation via TEOS/TMOS hydrolysis.

- Characterize loading efficiency (target: up to 28.3% as reported) and PL properties [16].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for the mesoporous silica encapsulation approach, which has demonstrated high PLQY and exceptional stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Silica Encapsulation of PQDs

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silica Precursors | Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | Forms silica network through hydrolysis and condensation | Most common precursor; balance reactivity with purity |

| Tetramethyl orthosilicate (TMOS) | Faster hydrolysis rate than TEOS | Useful for rapid encapsulation needs | |

| Silane Coupling Agents | (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Mediates interface between PQD and silica matrix | Amino group promotes adhesion; may affect PL |

| (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane (MPTES) | Thiol group for surface coordination | Strong binding to PQD surface; potential quenching | |

| Vinyltriethoxysilane (VTES) | Low VOC emission; improves dispersion | Environmental friendly option [17] | |

| Surfactants | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) | Template for mesoporous structures | Critical for MSN synthesis; remove excess post-reaction |

| Triton X-100 | Stabilizes microemulsion systems | Forms nanoreactors for uniform encapsulation | |

| Catalysts | Ammonium hydroxide | Base catalyst for hydrolysis/condensation | Concentration controls reaction rate and morphology |

| Hydrochloric acid | Acid catalyst for controlled hydrolysis | Produces more branched silica structures | |

| PQD Precursors | Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, PbI₂ | Forms perovskite crystal structure | Stoichiometry determines composition and emission |

| Solvents | Octadecene | High-booint solvent for synthesis | Enables high-temperature reactions |

| Toluene, Hexane | Dispersion and purification | Anhydrous grades prevent premature degradation |

Silica matrices provide a multifaceted protective environment for perovskite quantum dots that addresses their fundamental instability issues while preserving their exceptional optical properties. Through chemical shielding, nanoconfinement, surface passivation, and thermal stabilization, SiO₂ encapsulation significantly extends PQD lifetime and performance under operational conditions. The sol-gel methods described herein—including Stöber process, reverse microemulsion, and mesoporous template approaches—offer researchers versatile tools for designing optimized encapsulation architectures tailored to specific application requirements. As PQD technologies continue to advance toward commercial applications, silica encapsulation strategies will play an increasingly critical role in enabling their practical implementation across optoelectronics, photonics, and related fields.

In sol-gel methods for perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surface encapsulation, the selection of molecular precursors fundamentally determines the structural, optical, and stability characteristics of the resulting protective matrix. Alkoxides and organosilanes represent two critical precursor classes that enable controlled formation of inorganic and hybrid organic-inorganic networks at the PQD interface [18] [19]. These precursors undergo sequential hydrolysis and condensation reactions, forming metal oxide frameworks that encapsulate PQDs while mitigating environmental degradation pathways [18].

The sol-gel process transitions liquid precursors to solid networks through a "sol" (colloidal suspension) and finally to a "gel" (3D network extending through a fluid phase) [18]. This evolution allows for precise application of conformal coatings on PQD surfaces through techniques including dip-coating, spin-coating, and template-assisted methods [19]. The chemical versatility of alkoxide and organosilane precursors enables tailoring of network porosity, surface functionality, and mechanical properties essential for enhancing PQD photoluminescence quantum yield and operational lifetime.

Chemical Fundamentals of Key Precursors

Metal Alkoxides: Inorganic Network Formers

Metal alkoxides (M(OR)ₓ) serve as the primary precursors for constructing metal oxide matrices in PQD encapsulation. Their reactivity follows a well-defined pathway:

- Hydrolysis: Replacement of alkoxy groups with hydroxyl groups via nucleophilic attack by water molecules [18].

- Condensation: Formation of metal-oxygen-metal (M-O-M) bridges through polycondensation, releasing water or alcohol as byproducts [18] [19].

The electronegativity difference between metal and oxygen atoms significantly influences the ionic character of the M-O bond, thereby dictating hydrolysis rates and gelation kinetics [18]. Titanium alkoxides, such as titanium isopropoxide, demonstrate particularly high reactivity requiring chemical modification for controlled gelation applicable to PQD surface functionalization [19].

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Alkoxide Precursors for PQD Encapsulation

| Alkoxide | Chemical Formula | Reactivity | Resulting Oxide | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) | Si(OC₂H₅)₄ | Moderate | SiO₂ | Barrier matrix, surface passivation |

| Titanium isopropoxide | Ti(OCH(CH₃)₂)₄ | High | TiO₂ | High-refractive index coatings |

| Aluminum sec-butoxide | Al(OCH(CH₃)C₂H₅)₃ | High | Al₂O₃ | Protective encapsulation |

Organosilanes: Hybrid Interface Engineers

Organosilanes (R'ₓSi(OR)₄₋ₓ) constitute a specialized precursor class incorporating non-hydrolyzable organic substituents that introduce specific functionality to the resulting silica-based network [20] [21]. These precursors enable:

- Surface functionalization through organophilic groups that enhance compatibility with PQD surface ligands

- Controlled porosity via organic templates that can be subsequently removed

- Specific chemical reactivity through functional groups including amines, epoxides, and vinyl groups [21]

Methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS) exemplifies this category, where the methyl group introduces hydrophobicity to the resulting silica matrix, significantly enhancing moisture resistance of encapsulated PQDs [22]. Similarly, 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS) provides primary amine groups for subsequent bioconjugation or further chemical modification of the PQD surface [20].

Table 2: Functional Organosilane Precursors for PQD Surface Engineering

| Organosilane | Chemical Formula | Organic Functionality | Key Properties | PQD Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTMS | CH₃Si(OCH₃)₃ | Methyl | Hydrophobicity, reduced shrinkage | Moisture barrier |

| APTMS | (CH₂)₃NH₂Si(OCH₃)₃ | Aminopropyl | Amine reactivity, adhesion promotion | Bio-conjugation, ligand anchoring |

| GPTMS | (CH₂)₃OCH₂CHCH₂OSi(OCH₃)₃ | Glycidoxypropyl | Epoxide ring-opening reactivity | Cross-linking, polymer hybrid |

Experimental Protocols for PQD Functionalization

Protocol 1: Silica Encapsulation via Alkoxide Precursors

This protocol describes the formation of a conformal silica coating on PQDs using tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as the primary alkoxide precursor, adapted from methodologies for nanostructured metal oxides [19].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Precursor Solution: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, ≥99%) in anhydrous ethanol (10% v/v)

- Catalyst Solution: Ammonium hydroxide (28% NH₃) diluted 1:100 in deionized water

- PQD Dispersion: PQDs (5 mg/mL) in anhydrous toluene

- Solvent: Anhydrous ethanol (200 proof)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pre-hydrolysis of TEOS: Add 1 mL TEOS precursor solution to 9 mL anhydrous ethanol under inert atmosphere. Introduce 100 μL catalyst solution with vigorous stirring (500 rpm) at 25°C. Continue stirring for 30 minutes to initiate hydrolysis.

- PQD Introduction: Add 2 mL PQD dispersion dropwise to the pre-hydrolyzed TEOS solution under continuous stirring. Maintain inert atmosphere to prevent PQD degradation.

- Gelation: Reduce stirring rate to 100 rpm and allow reaction to proceed for 2-6 hours, monitoring gelation point by vial tilt test.

- Aging: Once gelation occurs, seal container and age for 12-24 hours at 25°C to strengthen network through continued condensation.

- Washing: Centrifuge encapsulated PQDs at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard supernatant and resuspend in fresh anhydrous ethanol. Repeat three times.

- Characterization: Analyze silica coating thickness by TEM, chemical composition by FTIR, and photoluminescence properties by fluorescence spectroscopy.

Critical Parameters:

- Water:TEOS molar ratio controls hydrolysis rate (typically 4:1 for controlled gelation)

- Reaction temperature must remain below 40°C to prevent PQD degradation

- Ammonium hydroxide concentration determines condensation kinetics

Protocol 2: Aminosilane Functionalization for Bio-interface

This protocol details surface functionalization with 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS) to introduce primary amine groups for subsequent bioconjugation, adapted from organosilane modification strategies [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Organosilane Solution: APTMS (3% v/v) in anhydrous toluene

- PQD Dispersion: PQDs (5 mg/mL) in anhydrous toluene

- Wash Solvent: Anhydrous toluene

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Surface Activation: Transfer 10 mL PQD dispersion to round-bottom flask equipped with condenser. Heat to 60°C with mild stirring (200 rpm) under inert gas purge.

- Silane Introduction: Add 1 mL organosilane solution dropwise over 5 minutes using syringe pump.

- Reaction: Maintain temperature at 60°C for 4 hours with continuous stirring.

- Quenching: Cool reaction mixture to 25°C and add 5 mL anhydrous toluene to stop reaction.

- Purification: Precipitate functionalized PQDs by addition of 40 mL anhydrous methanol. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes. Resuspend in original solvent.

- Validation: Confirm surface modification using ninhydrin test (formation of Ruhemann's purple, absorbance at 576 nm) and FTIR spectroscopy (appearance of N-H stretching vibrations) [20].

Critical Parameters:

- Strict control of moisture content (<50 ppm) prevents uncontrolled silane polymerization

- Reaction temperature above 50°C ensures complete surface reaction

- APTMS concentration controls surface amine density without multilayer formation

The diagram above illustrates the parallel pathways for alkoxide and organosilane functionalization, highlighting key steps in each encapsulation strategy.

Analytical Methods for Characterization

Comprehensive characterization of functionalized PQDs validates encapsulation effectiveness and guides process optimization. Essential analytical techniques include:

Structural Analysis:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Direct visualization of core-shell morphology and coating thickness (1-20 nm range) [20] [19]

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Verification of perovskite crystal structure preservation post-encapsulation [20]

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Identification of characteristic siloxane (Si-O-Si, 1000-1100 cm⁻¹) and organic functional group vibrations [20]

Surface Properties:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Elemental composition and chemical state analysis of surface species

- Water Contact Angle: Hydrophobicity assessment for moisture resistance (MTMS-derived coatings typically >100°) [22]

Optical Performance:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Quantification of encapsulation-induced efficiency changes

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence: Excited-state lifetime monitoring of charge carrier dynamics

- Stability Testing: Accelerated aging under thermal, moisture, and illumination stress

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Functionalized PQDs

| Characterization Method | Key Parameters | Target Values | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEM | Coating thickness, uniformity | 5-15 nm, conformal | Barrier integrity, surface coverage |

| FTIR | Si-O-Si peak intensity, organic groups | Strong ~1080 cm⁻¹ | Network formation, functionality |

| PLQY | Quantum yield retention | >90% initial value | Minimal surface defect introduction |

| Contact angle | Water repellency | >100° for MTMS | Hydrolytic stability |

| Accelerated aging | PL intensity half-life | 5-10x improvement | Operational longevity |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Successful implementation of alkoxide and organosilane functionalization requires attention to common challenges:

Gelation Control:

- Problem: Premature gelation before complete PQD dispersion

- Solution: Implement staged precursor addition with controlled hydrolysis rates [18]

- Optimization: Adjust water:precursor ratio and catalyst concentration to balance reaction kinetics

Surface Defect Mitigation:

- Problem: Reduced PLQY after encapsulation

- Solution: Incorporate surface passivation steps using coordinating solvents prior to encapsulation

- Optimization: Employ ligand exchange to improve interface compatibility between PQD and growing matrix

Scalability Considerations:

- Problem: Batch-to-batch variability in coating properties

- Solution: Standardize mixing parameters and reagent addition rates

- Optimization: Implement inline monitoring of viscosity and pH for process control

The strategic application of alkoxide and organosilane precursors enables robust PQD encapsulation schemes that balance protective function with optical performance. These protocols provide a foundation for developing PQD-based materials with enhanced stability for photonic, electronic, and biomedical applications.

The Impact of Encapsulation on PQD Photoluminescence and Quantum Yield

Metal Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY), narrow emission profiles, and broadly tunable bandgaps [23]. Their fundamental structure, denoted as ABX₃ where A is an organic or inorganic cation, B is a metal cation (typically Pb²⁺), and X is a halide anion, facilitates strong light absorption and efficient emission [23]. Despite these advantages, the widespread application of PQDs is severely hampered by their intrinsic instability under ambient conditions, particularly their susceptibility to moisture, oxygen, heat, and light [24] [25].

Encapsulation strategies, particularly those utilizing sol-gel derived silica matrices, have proven to be a highly effective countermeasure. This approach forms a protective barrier around the PQDs, shielding them from environmental degradation while often enhancing their luminescent properties through surface passivation [26] [25]. This document, framed within a broader thesis on sol-gel methods for PQD surface encapsulation, provides detailed application notes and protocols. It is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the practical methodologies and analytical frameworks necessary to implement these techniques effectively, thereby advancing the development of stable, high-performance PQD-based devices.

Quantitative Impact of Encapsulation on PQD Optical Properties

Encapsulation significantly influences the key optical metrics of PQDs. The following tables summarize quantitative data on the enhancement of stability, photoluminescence (PL), and overall device performance.

Table 1: Impact of Encapsulation on PQD Stability and Photoluminescence Intensity

| Encapsulation System | PQD Type | Test Conditions | PL Retention/Change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silica Matrix (MQD) | CdSe/ZnS | High-power optical exposure | PL quenching reduced to 19% (vs. 48% in bare QDs) | [27] |

| SiO₂ Encapsulation | FAPbI₃ | Humid atmosphere (60%), 1 month | ~94% of initial PL preserved | [25] |

| Siloxane Matrix | CsPbBr₃ | Ambient atmosphere, 1 month | ~80% of original PL efficiency maintained | [28] |

| CsPbBr₃@PDMS in PAAm Hydrogel | CsPbBr₃ | Aqueous environment | High PLQY maintained; stability enhanced | [23] |

Table 2: Impact of Encapsulation on Quantum Yield and Device Performance

| Encapsulation System | PQD Type | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA Film Integration | CdSe/ZnS | LED efficiency & thermal stability | Enhanced efficiency and thermal stability for WLEDs | [27] |

| SiO₂ Encapsulation | FAPbI₃ | White LED Color Gamut | 144% of NTSC standard | [25] |

| Silane/Siloxane Encapsulation | CsPbBr₃ | Flexibility & Stability in displays | Functional flexible display with 5 mm bend radius | [28] |

| 3D Mesoporous Silica | CsPbX₃ | Application range | Suitable for LEDs and luminescent thin films | [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Sol-Gel Encapsulation of PQDs

Protocol 1: APTES-Assisted Silica Encapsulation of FAPbI₃ PQDs

This one-pot ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) and sol-gel method produces silica-embedded FAPbI₃ QDs with high phase stability [25].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents

- Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) & Lead Iodide (PbI₂): PQD precursors.

- Acetonitrile (ACN): A non-coordinating solvent for precursors, superior to DMF for enhancing stability [25].

- 3-Aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APTES): Silica precursor and surface ligand; the amino group interacts with Pb²⁺, controlling growth and initiating silica network formation.

- Oleic Acid (OA): Co-ligand for surface stabilization during synthesis.

- Toluene and Hexane: For reprecipitation and purification.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve FAI (0.15 mmol) and PbI₂ (0.15 mmol) in 5 mL of anhydrous ACN inside a nitrogen-filled glovebox.

- Reaction Initiation: Quickly inject the precursor solution into a mixture containing 0.5 mL of APTES and 0.5 mL of OA in 10 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring.

- Gelation and Aging: Stir the reaction mixture for 60-240 minutes at ambient temperature. The hydrolysis and condensation of APTES occur, forming a silica matrix encapsulating the PQDs. Longer stirring times promote a more uniform distribution of QDs within silica beads versus core-shell structures [25].

- Purification: Precipitate the silica-encapsulated PQDs by adding hexane. Isolate the product via centrifugation (e.g., 6000 rpm for 5 minutes).

- Post-processing: Dry the collected powder under vacuum. The resulting powder can be re-dispersed in appropriate solvents for film fabrication or integrated into polymer matrices like PMMA for device application [25].

Protocol 2: Silane Ligand Exchange for PQD/Siloxane Composite Films

This protocol describes the functionalization of PQDs with silane ligands for subsequent incorporation into a photocurable siloxane resin, ideal for fabricating robust color conversion layers (CCLs) in displays [28].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents

- Oleate-capped PQDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃): Synthesized via hot-injection method [28].

- Methylammonium Bromide (MABr): Anion-rich salt for surface activation.

- (3-Mercaptopropyl)methyldimethoxy silane: Silane ligand for exchange; thiol group binds to the PQD surface, and methoxy groups undergo condensation.

- Siloxane Resin Precursors: MPTMS (3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate) and DPSD (diphenylsilanediol).

- Barium Hydroxide Monohydrate (Ba(OH)₂·H₂O): Catalyst for sol-gel condensation.

- 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone: Photo-initiator for UV curing.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Ligand Exchange:

- Mix an oleate-PQDs solution (10 mg/mL in toluene) with MABr (0.1 g) and (3-mercaptopropyl)methyldimethoxy silane (20 µL).

- Stir the mixture in an N₂ atmosphere for 1 hour to facilitate ligand exchange.

- Purify the resulting silane-capped PQDs (silane-PQDs) by centrifugation and redisperse in toluene [28].

Siloxane Resin Preparation:

- React MPTMS and DPSD at a 1:1 molar ratio with 0.1 mol% Ba(OH)₂·H₂O catalyst at 85°C for 5 hours.

- Remove the methanol byproduct under vacuum to obtain methacrylate oligosiloxane resin [28].

Composite Fabrication and Curing:

- Mix the silane-PQDs solution with the siloxane resin (100:1 weight ratio) and stir until the solvent evaporates.

- Add 0.2 wt% of the photo-initiator to the composite.

- Cast the mixture into a mold or deposit it on a substrate and expose to UV light (365 nm) for 10 minutes to achieve a fully cured, solid film [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Sol-Gel Encapsulation of PQDs

| Reagent | Function in Encapsulation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| APTES | Silica precursor and bifunctional ligand; amino group coordinates with PQD surface, alkoxy groups form SiO₂ network. | Concentration controls silica shell thickness and QD size [25]. |

| Tetramethyl Orthosilicate (TMOS) | Traditional silica precursor for hydrolysis and sol-gel reaction. | Can require more complex control over reaction conditions to prevent PL quenching [25]. |

| (3-Mercaptopropyl)trimethoxy silane | Bifunctional ligand for exchange; thiol group provides strong binding to PQD surface. | Enhances dispersibility in siloxane matrices and final stability [28]. |

| Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate (EVA) | Encapsulating polymer matrix for flexible films. | Provides excellent thermal stability and reduces heat accumulation in LED applications [27]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Primary surface ligands during initial QD synthesis. | Often replaced or supplemented during encapsulation to improve matrix integration [28] [25]. |

The sol-gel encapsulation of PQDs represents a critical advancement in stabilizing these promising nanomaterials without sacrificing their exceptional optical properties. The protocols outlined herein provide reproducible methods for creating robust silica and siloxane-based composites, effectively mitigating degradation from moisture, heat, and optical stress. The quantitative data confirms that successful encapsulation preserves high PLQY and PL intensity over extended periods, enabling the integration of PQDs into practical devices such as wide-color-gamut WLEDs and flexible displays. By adhering to these detailed application notes and protocols, researchers can systematically explore and optimize encapsulation strategies, accelerating the path toward commercial and biomedical applications of perovskite quantum dots.

Synthesis Strategies and Biomedical Applications of Encapsulated PQDs

Surface encapsulation of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represents a critical advancement in enhancing their environmental stability for optoelectronic and biomedical applications. Despite their exceptional optical properties, such as high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and tunable bandgaps, the widespread application of PQDs is limited by their susceptibility to degradation from moisture, oxygen, and heat [29] [30]. Silica coating has emerged as a premier strategy for protecting PQDs, forming an inert, transparent barrier that mitigates environmental degradation while preserving optical performance [29]. This application note details two prominent silica coating methodologies—Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) and Sol-Gel techniques—framed within broader thesis research on PQD surface encapsulation. We provide comprehensive experimental protocols, quantitative comparisons, and practical guidance tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement these protective strategies.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) for Silica Coating

Principle and Advantages

The LARP technique enables the direct synthesis and encapsulation of PQDs through a precipitation process driven by solvent polarity change, facilitated by ligand molecules that control crystal growth and stabilize the nanocrystal surface [30]. This method is particularly valuable for producing silica-coated PQDs with uniform size distribution and high crystallinity without requiring high-temperature conditions. The silica shell grown via LARP effectively passivates surface defects, enhances PLQY, and provides a robust physical barrier against environmental stressors [29] [30]. A key advantage is the ability to control shell properties through manipulation of ligand chemistry and reaction parameters.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials:

- Precursors: Cesium bromide (CsBr, 99.99%), Lead bromide (PbBr₂, 99.99%)

- Solvents: Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous), Toluene (anhydrous), Isopropyl alcohol (IPA)

- Ligands: Oleic acid (OA, 90%), Oleylamine (OAm, 90%)

- Silica Source: Tetramethyl orthosilicate (TMOS, 99%) or 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES, 99%)

- Other: Ammonia solution (28% NH₃ in H₂O)

Procedure:

- PQD Precursor Solution: Dissolve 0.2 mmol CsBr and 0.2 mmol PbBr₂ in 5 mL of anhydrous DMF in a nitrogen-filled glovebox. Add 0.5 mL OA and 0.5 mL OAm. Stir vigorously at room temperature until fully dissolved.

- LARP Silica Coating Solution: In a separate vial, add 20 mL toluene, 1 mL OAm, 0.5 mL TMOS (or APTES), and 0.1 mL ammonia solution. Stir for 5 minutes to pre-hydrolyze the silica precursor.

- Nanocrystal Precipitation and Encapsulation: Rapidly inject 0.5 mL of the PQD precursor solution into the LARP silica coating solution under vigorous stirring (800-1000 rpm). The solution will become turbid and luminescent immediately.

- Reaction Aging: Allow the reaction to proceed for 2-4 hours at room temperature with continuous stirring to facilitate silica network formation around the nucleated PQDs.

- Purification: Centrifuge the reaction mixture at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant and redisperse the pellet in 5 mL of anhydrous toluene. Repeat this centrifugation-redispersion cycle twice to remove unreacted precursors and ligands.

- Storage: Store the purified CsPbBr₃@SiO₂ core-shell nanoparticles in toluene at 4°C in the dark for further use.

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain strict control over reaction temperature (25±2°C) throughout the process

- Ensure rapid and uniform mixing during precursor injection to achieve monodisperse particles

- Optimize TMOS/OAm ratio to balance between silica condensation rate and surface passivation quality

- Control ammonia concentration precisely, as it catalyzes both silica condensation and affects PQD stability

LARP Process Workflow

Sol-Gel Techniques for Silica Coating

Principle and Advantages

Sol-gel processing represents a well-established bottom-up approach for fabricating ceramic materials through the transition of a colloidal solution (sol) into a solid network (gel) [7] [31]. For PQD encapsulation, this method involves hydrolysis and condensation of silica precursors (typically alkoxides) to form a controlled silica shell around pre-synthesized PQDs [29]. The sol-gel approach offers exceptional tunability of shell thickness, porosity, and density through manipulation of reaction parameters including precursor concentration, catalyst pH, water content, and temperature [7] [31]. This technique can produce both dense, impermeable shells for maximum protection and mesoporous shells for specific applications like drug delivery [31] [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials:

- Pre-synthesized PQDs: CsPbX₃ (X=Cl, Br, I) nanocrystals in toluene (5 mg/mL)

- Silica Precursor: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 98%) or APTES

- Solvents: Toluene (anhydrous), Ethanol (absolute)

- Catalyst: Ammonia solution (28% NH₃ in H₂O) or hydrochloric acid (0.1N HCl)

- Surfactant: Triton X-100

Procedure (Alkoxide Precursor Route):

- PQD Surface Preparation: Transfer 10 mL of pre-synthesized PQDs in toluene to a three-neck flask. Add 0.1 mL of APTES and stir for 30 minutes under nitrogen atmosphere to promote surface functionalization.

- Hydrolysis Solution Preparation: In a separate container, prepare a solution containing 5 mL ethanol, 1 mL deionized water, and 0.2 mL ammonia catalyst.

- Silica Precursor Addition: Slowly add 0.3 mL TEOS dropwise to the hydrolysis solution while stirring. Allow partial hydrolysis to occur for 15 minutes until the solution becomes slightly opaque.

- Coating Process: Gradually add the hydrolyzed TEOS solution to the PQD dispersion under vigorous stirring at room temperature. Continue reaction for 2-6 hours depending on desired shell thickness.

- Shell Growth Control: Monitor shell growth by periodic sampling and UV-Vis/PL measurements. For thicker shells, additional TEOS can be added in increments.

- Aging and Drying: Age the coated PQDs for 12 hours at room temperature. Recover particles by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Wash twice with ethanol and once with hexane.

- Post-treatment: For enhanced stability, anneal the particles at 60°C for 1 hour under vacuum to complete condensation and remove residual solvents.

Critical Parameters:

- Pre-functionalization with APTES provides nucleation sites for uniform silica growth

- Strict control of water-to-alkoxide ratio (typically 4:1 to 8:1) determines hydrolysis rate

- Ammonia concentration (0.1-0.5M) critically affects condensation kinetics and network density

- Reaction temperature (25-60°C) controls silica growth rate and morphology

- Solvent polarity influences precursor solubility and interfacial energy

Sol-Gel Chemistry and Process

Comparative Analysis and Applications

Shell Thickness and Application Performance

The table below summarizes how silica shell thickness influences key performance parameters across different applications, based on experimental findings from the literature [29].

Table 1: Influence of Silica Shell Thickness on Application Performance

| Shell Thickness | Application | Performance Implications | Recommended Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-thin (<2 nm) | PeLEDs [29] | Enables efficient charge carrier injection; maintains high device efficiency | Sol-gel with APTES |

| Thin (2-5 nm) | Bio-imaging [29] | Preserves fluorescence while providing sufficient protection in aqueous media | LARP or Sol-gel |

| Moderate (5-15 nm) | White LEDs [29] | Good balance between protection and maintenance of optical properties | Sol-gel with TMOS/TEOS |

| Thick (>15 nm) | Drug Delivery [29] | Enhanced chemical barrier; suitable for functionalization; may reduce fluorescence | Sol-gel with extended reaction time |

Stability Enhancement Data

Silica coating significantly improves PQD stability under various environmental stressors. The following table quantifies these enhancements based on experimental studies [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Stability Enhancement of Silica-Coated PQDs

| Stress Condition | Uncoated PQDs | Silica-Coated PQDs | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambient Air (75% humidity) | PLQY drops to <10% in 3 days [29] | PLQY maintained >80% after 30 days [29] | >10x |

| Aqueous Environment | Complete degradation in <40 min [29] | >80% PLQY retention after 40 min [29] | >15x |

| Thermal Stress (80°C) | Rapid degradation in hours [30] | Stable for >100 hours [30] | >10x |

| UV Irradiation | Significant bleaching in 24 hours [30] | Minimal degradation after 48 hours [30] | >5x |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Silica Coating of PQDs

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silica Precursors | TEOS, TMOS, APTES [29] | Source of silica network; determines condensation kinetics | APTES provides amine groups for surface passivation and faster condensation [29] |

| Catalysts | NH₄OH, HCl [7] [32] | Controls hydrolysis and condensation rates | Acid catalysts produce denser gels; base catalysts yield more particulate structures [7] |

| Solvents | Toluene, Hexane, DMF, IPA [29] [30] | Medium for reactions; influences precursor solubility | Non-polar solvents favor controlled growth; polar solvents accelerate condensation [29] |

| Ligands/Surfactants | Oleic Acid, Oleylamine, Triton X-100 [29] [30] | Stabilize PQDs; control interface energy; mediate silica growth | OA/OAm combinations provide optimal surface coverage for PQDs [30] |

| PQD Precursors | Cs₂CO₃, PbBr₂, PbI₂ [30] | Source of perovskite composition | Purification and stoichiometry critical for high-quality PQDs [30] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Challenges and Solutions

- Incomplete Shell Coverage: Manifested by residual sensitivity to polar solvents. Solution: Optimize pre-functionalization with APTES; ensure sufficient reaction time; consider staggered precursor addition.

- PQD Degradation During Coating: Evidenced by dropping PLQY during synthesis. Solution: Use milder catalysts (dilute ammonia); lower reaction temperature; reduce water content; employ nitrogen atmosphere.

- Aggregation of Core-Shell Particles: Solution: Introduce steric stabilizers (e.g., PEG-silanes); optimize solvent composition; reduce precursor concentration; employ ultrasonic dispersion during synthesis.

- Excessive Shell Thickness: Results in reduced quantum efficiency. Solution: Precisely control silica precursor concentration; monitor growth kinetics; employ shorter reaction times.

Characterization Techniques

Essential characterization methods for evaluating silica-coated PQDs include:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Direct visualization of core-shell morphology and shell thickness [29]

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Verification of perovskite crystal structure preservation after coating [29]

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Confirmation of silica network formation and surface chemistry [32]

- UV-Vis and PL Spectroscopy: Assessment of optical properties and quantum efficiency [29] [30]

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Evaluation of particle size distribution and colloidal stability [29]

The implementation of standardized silica coating protocols via LARP and Sol-Gel techniques provides robust pathways to enhance PQD stability while maintaining their exceptional optical properties. The LARP method offers a streamlined, single-pot approach suitable for applications requiring moderate protection, while the Sol-Gel technique enables precise control over shell architecture for demanding applications in optoelectronics and biomedicine. As research progresses, optimization of these encapsulation strategies will be crucial for realizing the full potential of PQDs in commercial applications, particularly where environmental stability is a limiting factor. Future directions include development of hybrid organic-inorganic shells, multifunctional coatings, and scale-up processes for industrial production.

This application note details standardized protocols for the sol-gel synthesis of two advanced functional architectures: hollow mesoporous silica spheres (HMSs) and amino-functionalized silica coatings. These materials are of paramount importance in the context of surface encapsulation research for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), serving as foundational platforms for developing robust protection systems. Hollow silica shells provide a confined environment that can shield PQD cores from environmental degradants such as moisture, oxygen, and heat, while mitigating ion migration and enhancing photostability. Conversely, amino-functionalized coatings introduce specific surface chemistries that can passivate PQD surface defects, improve dispersion stability in various matrices, and facilitate further covalent bonding with functional molecules or polymers. The protocols herein are designed for reproducibility, providing researchers with clear methodologies, key characterization data, and essential reagent toolkits to accelerate innovation in PQD stabilization and functionalization.

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Hollow Mesoporous Silica Spheres (HMSs) via Sol-Gel/Emulsion

The synthesis of Hollow Mesoporous Silica Spheres (HMSs) via a sol-gel/oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion approach utilizes emulsion droplets as soft templates, bypassing the need for solid templates and their subsequent removal [33] [34]. In this process, an oil phase containing the silica precursor, tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), is emulsified in a continuous water-ethanol phase. The surfactant cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) serves a dual purpose: it stabilizes the oil droplets and acts as a structure-directing agent for the mesopores [33]. The hydrolysis and condensation of TEOS are catalyzed by ammonia, leading to the formation of a solid silica shell at the droplet interface. Subsequent calcination removes the CTAB template and any organic residues, yielding hollow spheres with ordered mesopores in the shell [34]. This method allows for precise control over the sphere diameter and shell thickness by adjusting key synthetic parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents for the synthesis of Hollow Mesoporous Silica Spheres.

| Reagent | Function in the Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Silicon alkoxide precursor; forms the silica network via hydrolysis and condensation. | Must be freshly distilled before use for optimal reactivity [34]. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant; stabilizes emulsion droplets and templates the formation of mesopores. | Critical for directing the mesoporous structure of the silica shell [33] [34]. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH) | Base catalyst; accelerates the hydrolysis and condensation reactions of TEOS. | Typically a 25% NH₃ in water solution is used [34]. |

| Anhydrous Ethanol | Co-solvent; improves the stability of the TEOS oil droplets in the emulsion. | Key for controlling monodispersity and final sphere diameter [34]. |

| n-Hexane | Oil phase; can act as the core of the emulsion droplet template. | Used in double emulsion methods for hollow structure formation [35]. |

| High-Purity Water | Solvent for the continuous phase; reactant for the hydrolysis of TEOS. | Resistivity of 18 MΩ·cm is recommended [34]. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Materials:

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), freshly distilled

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)

- Ammonium hydroxide (25 wt% NH₃ in water)

- Anhydrous ethanol

- High-purity water (18 MΩ·cm)

Procedure:

- Preparation of the Aqueous Phase: Dissolve CTAB (5 mM) in a mixture of high-purity water (50 mL) and ethanol (30 mL). Add ammonium hydroxide to this solution to achieve a pH of approximately 11.

- Emulsion Formation: Add TEOS (2 mL) to the solution from Step 1 under vigorous stirring (e.g., 500 rpm). The TEOS will form oil droplets within the continuous water/ethanol phase, creating an oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion.

- Sol-Gel Reaction: Allow the reaction to proceed for 2 hours at room temperature under continuous stirring. The hydrolysis and condensation of TEOS will occur at the droplet interface, forming silica shells.

- Aging and Collection: Let the mixture stand without stirring for an additional 12 hours to age. Collect the resulting white precipitate by centrifugation.

- Washing: Wash the precipitate thoroughly with ethanol and water to remove unreacted precursors and surfactant.

- Calcination: Dry the product and calcine it in a muffle furnace at 600°C for 6 hours to remove the CTAB template, yielding the final HMSs.

Characterization and Key Performance Data

Table 2: Tunable properties and characterization data for synthesized HMSs [34].

| Parameter Varied | Effect on HMSs Morphology | Typical Resulting Value / Range |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-to-Water Ratio | Controls the diameter of the hollow spheres. A higher ratio increases diameter. | Diameter: 210 nm to 720 nm [34]. |

| CTAB Concentration | Mediates the shell thickness. Higher concentration leads to thicker shells. | Shell thickness: Tunable via CTAB concentration [34]. |

| BET Surface Area | -- | 924–1766 m²/g [34]. |

| BJH Pore Size | -- | ~3.10 nm [34]. |

Protocol 2: Amino-Functionalization of Silica Surfaces

Amino-functionalization introduces nitrogen-containing groups onto silica surfaces, drastically altering their surface chemistry and functionality. This process enables enhanced interactions with various targets, including metal ions for sequestration and specific molecules in analytical applications [36] [37]. Two primary sol-gel strategies are employed:

- Co-condensation: An organosilane precursor containing an amino group (e.g., 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl amine, TMSPA) is mixed with a primary silica precursor (e.g., TEOS) during the sol-gel process, leading to the incorporation of amine groups directly into the growing silica network [37].

- Post-synthesis Grafting (Kinetic Doping): Functional molecules are introduced into a pre-formed, but still evolving, sol-gel network. The growing silica matrix entraps the functional molecules, such as branched polyethylenimine (BPEI), as it condenses [36]. This method is particularly useful for incorporating large polymeric species.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents for the amino-functionalization of silica surfaces.

| Reagent | Function in the Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl amine (TMSPA) | Amino-functional organosilane precursor; provides primary amine groups for surface binding. | Used in co-condensation to create a polar, functionalized coating [37]. |

| Branched Polyethylenimine (BPEI) | Polymeric amine; provides a high density of primary, secondary, and tertiary amines for multifunctional sites. | High molecular weight (e.g., 25,000 MW) is loaded via kinetic doping [36]. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Primary silica network former. | Serves as the backbone for the functionalized material. |

| Hydroxy-Terminated Polydimethylsiloxane (OH-PDMS) | Coating polymer; contributes to the formation of a porous, composite organic-inorganic network. | Used with TMSPA to create SPME fibers [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Method A: Co-condensation with TMSPA for SPME Fiber Coating [37]

- Sol Preparation: Prepare a sol solution by mixing TEOS, TMSPA, OH-PDMS, and ethanol. Add a catalytic amount of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) containing 5% water.

- Hydrolysis: Sonicate the mixture for a set period to facilitate the hydrolysis of the precursors.

- Fiber Coating: Immerse a fused-silica fiber into the sol solution for a specified time to deposit the coating.

- Curing and Aging: Withdraw the fiber and allow it to cure in a conditioning environment for 24 hours before use.

Method B: Kinetic Doping with BPEI for Thin Films [36]

- Film Deposition: Deposit a silica sol-gel thin film onto a substrate via a method like drain coating.

- Kinetic Doping Window: After a specific delay time (e.g., 5 minutes) post-coating, introduce the film to an aqueous loading solution containing BPEI (25,000 MW).

- Entrapment and Washing: The BPEI molecules are entrapped by the evolving silica network. Subsequently, wash the film to remove any unbound BPEI.

- Characterization: The loaded films can be assessed for amine content and application-specific performance, such as copper(II) ion sequestration.

Characterization and Key Performance Data

Table 4: Performance data for amino-functionalized silica materials.

| Functionalization Method / Material | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Doping with BPEI (25,000 MW) | BPEI concentration in film | ~0.5 M [36] |

| Copper(II) ion sequestration capacity | ~10 ± 6 mmol/g [36] | |

| Co-condensation with TMSPA/OH-PDMS | Detection limit for chlorophenols (SPME-GC-MS) | 0.02–0.05 ng/mL [37] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Experimental Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Hollow Silica Shell Synthesis

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the synthesis of hollow mesoporous silica spheres.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for the synthesis of hollow mesoporous silica spheres via the sol-gel/emulsion method, highlighting key control parameters.

Workflow for Amino-Functionalization Strategies

The following diagram outlines the two principal pathways for incorporating amine functionality into silica matrices.

Figure 2: Decision tree illustrating the two primary sol-gel strategies for amino-functionalization of silica materials and their typical applications.