Advanced Passivation Strategies for CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots: Enhancing Performance and Stability for Optoelectronic Applications

This article comprehensively reviews the latest strategies for passivating surface defects in CsPbBr3 quantum dots (QDs), a leading material for next-generation optoelectronics.

Advanced Passivation Strategies for CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots: Enhancing Performance and Stability for Optoelectronic Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the latest strategies for passivating surface defects in CsPbBr3 quantum dots (QDs), a leading material for next-generation optoelectronics. We explore the fundamental origins of non-radiative recombination, present a detailed methodology of chemical and structural passivation techniques—including ligand engineering, cation substitution, and heterostructure formation—and provide troubleshooting guidelines for optimizing photoluminescence quantum yield, charge transport, and operational stability. By comparing the performance outcomes of various approaches, this work serves as an essential resource for researchers and scientists developing high-efficiency, stable perovskite QD-based devices such as light-emitting diodes, lasers, and optical communication systems.

Understanding Surface Defects in CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots: Origins and Impacts on Optoelectronic Properties

FAQs: Understanding Surface Defects in CsPbBr₃ QDs

1. What are the primary types of surface defects in CsPbBr₃ Quantum Dots? The two most common and detrimental surface defects are uncoordinated lead atoms (Pb²⁺) and halide vacancies (V˅Br⁻). These defects act as trapping states for charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination, which reduces photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and compromises the performance of optoelectronic devices [1] [2].

2. How do halide vacancies (V˅Br⁻) negatively impact my QDs? Halide vacancies are labile and facilitate ion migration within the perovskite lattice. This leads to:

- Deep trap states: These states capture excitons and cause them to recombine without emitting light [3] [4].

- Instability: Accelerated degradation under heat, light, or electrical stress [1].

- Luminescence quenching: A significant drop in the brightness and efficiency of the QDs [2].

3. What causes uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites to form? Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites occur when the native capping ligands (like oleic acid) desorb from the QD surface. This is often due to the highly dynamic and weak bonding between these traditional long-chain ligands and the perovskite crystal structure, especially during purification or long-term storage [1].

4. Why is my CsPbBr₃ QD solution losing its luminescence over time? A primary reason is the progressive loss of surface passivation. As ligands detach, unpassivated Pb²⁺ sites and halide vacancies are exposed, increasing non-radiative recombination pathways. Furthermore, bromide ions can be lost to the environment, exacerbating the problem of halide vacancies [1] [5].

5. Can these defects be completely eliminated? While it is challenging to eliminate all defects, they can be effectively passivated. Passivation involves using chemical agents or structural engineering to "heal" these defect sites, tying up the uncoordinated bonds and filling the vacancies, thereby restoring the optoelectronic quality of the QDs [2] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: Addressing Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY)

Symptom: Newly synthesized or purified CsPbBr₃ QDs exhibit a lower-than-expected PLQY.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

Cause: Inadequate surface passivation due to weak, dynamic ligands like OA/OAm.

- Solution: Implement a dual-ligand passivation strategy.

- Protocol: Replace a portion of the oleic acid with stronger coordinating ligands. As demonstrated in one study, a combination of homophthalic acid (HA, a bidentate ligand) and 2-bromoethanesulphonic acid sodium salt (SBES) can be highly effective [1].

- Synthesize CsPb(Br/I)₃ QDs via the hot-injection method.

- Use HA and SBES as co-passivators along with oleylamine (OAm).

- The bidentate structure of HA strongly binds to uncoordinated Pb²⁺, while the sulfonate group from SBES also coordinates with Pb²⁺. Simultaneously, the Br⁻ from SBES fills bromide vacancies [1].

- Expected Outcome: This synergistic passivation can increase the PLQY to 71% and significantly enhance stability at high temperature and humidity [1].

Cause: High density of halide vacancies.

- Solution: Introduce halide-rich additives or use halide-containing ligands.

- Protocol: Dope the QDs with formamidinium (FA) cations to promote Br-enrichment.

- Synthesize Cs₁₋ₓFAₓPbBr₃ QDs with an optimal FA content (e.g., x=0.04).

- The FA cations form hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with Br⁻ ions, leading to Br-enrichment in the perovskite framework and a reduction in V˅Br⁻ defects [3].

- Expected Outcome: PLQY can increase from 76.8% (undoped) to 85.1% (FA-doped) [3].

Guide 2: Mitigating Poor Thermal and Operational Stability

Symptom: QDs degrade rapidly under elevated temperatures or during operation in an LED device, losing luminescence and changing color.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

Cause: Ligand desorption at high temperatures.

- Solution: Employ inorganic ligand passivation and core-shell engineering.

- Protocol: Perform a ZnF₂ post-treatment on the CsPbBr₃ QDs.

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs via ligand-assisted reprecipitation.

- Inject a solution of ZnF₂ inorganic ligand and stir.

- Purify the resulting QDs via centrifugation.

- This treatment forms a dual-shell structure: a CsPbBr₃:F inner shell and a zinc-rich outer shell. The inner shell suppresses thermal degradation, and both shells mitigate surface defects [6].

- Expected Outcome: The QDs maintain their optical properties and crystallinity even after heating at 120°C for 60 minutes, achieve a near-unity PLQY (97%), and show a 24-fold enhancement in LED device lifespan [6].

Cause: Ion migration exacerbated by surface defects.

- Solution: Passivate with metal cations.

- Protocol: Incorporate gallium (Ga³⁺) cations during or after synthesis.

- Introduce Ga cations (e.g., 40% molar ratio) to the precursor solution or post-synthetically treat the QDs.

- The Ga cations bind to the QD surface, passivating defect sites and improving crystalline quality [7].

- Expected Outcome: The PLQY of CsPbBr₃ QDs can be increased from 60.2% to 86.7%, and the resulting LEDs exhibit a maximum brightness over two times higher than devices made from pristine QDs [7].

The following table summarizes key quantitative improvements achieved by various defect passivation strategies for CsPbBr₃-based QDs.

Table 1: Efficacy of Different Defect Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Key Reagents | Defect Targeted | Reported PLQY Improvement | Key Stability Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Ligand Passivation [1] | Homophthalic Acid (HA), 2-Bromoethanesulphonic acid sodium salt (SBES) | Uncoordinated Pb²⁺, V˅Br⁻ | Up to 71% | Stable after 90 days storage; stable at 80°C/80% humidity |

| Cation Doping [7] | Gallium (Ga³⁺) cations | Surface defects (general) | 60.2% → 86.7% | Enhanced operational stability in LEDs |

| Dual-Shell Engineering [6] | Zinc Fluoride (ZnF₂) | Uncoordinated Pb²⁺, V˅Br⁻, Thermal degradation | Up to 97% (near-unity) | Stable at 120°C for 60 min; 24x LED lifespan |

| FA Cation Doping [3] | Formamidinium (FA⁺) | V˅Br⁻ | 76.8% → 85.1% | Improved performance in LED devices |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Passivating CsPbBr₃ QD Surface Defects

| Reagent | Function | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Homophthalic Acid (HA) [1] | Bidentate Carboxylic Acid Ligand | Strongly chelates to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via its two carboxylate groups, providing more stable passivation than monodentate OA. |

| 2-Bromoethanesulphonic acid sodium salt (SBES) [1] | Multi-functional Halide Equivalent | The sulfonate group coordinates with Pb²⁺, while the Br⁻ ion fills bromide vacancies (V˅Br⁻). |

| Gallium (Ga³⁺) Cations [7] | Cationic Passivator | Binds to the QD surface, suppressing defect states and improving crystalline quality, thereby enhancing radiative recombination. |

| Zinc Fluoride (ZnF₂) [6] | Inorganic Shell Precursor | Forms a dual protective shell (CsPbBr₃:F and Zn-rich shell) that suppresses halide vacancy formation and inhibits thermal degradation. |

| Formamidinium (FA⁺) Iodide/Salt [3] | A-site Cation Dopant | Its hydrogen bonding with Br⁻ ions leads to Br-enrichment in the lattice, reducing V˅Br⁻ defects. |

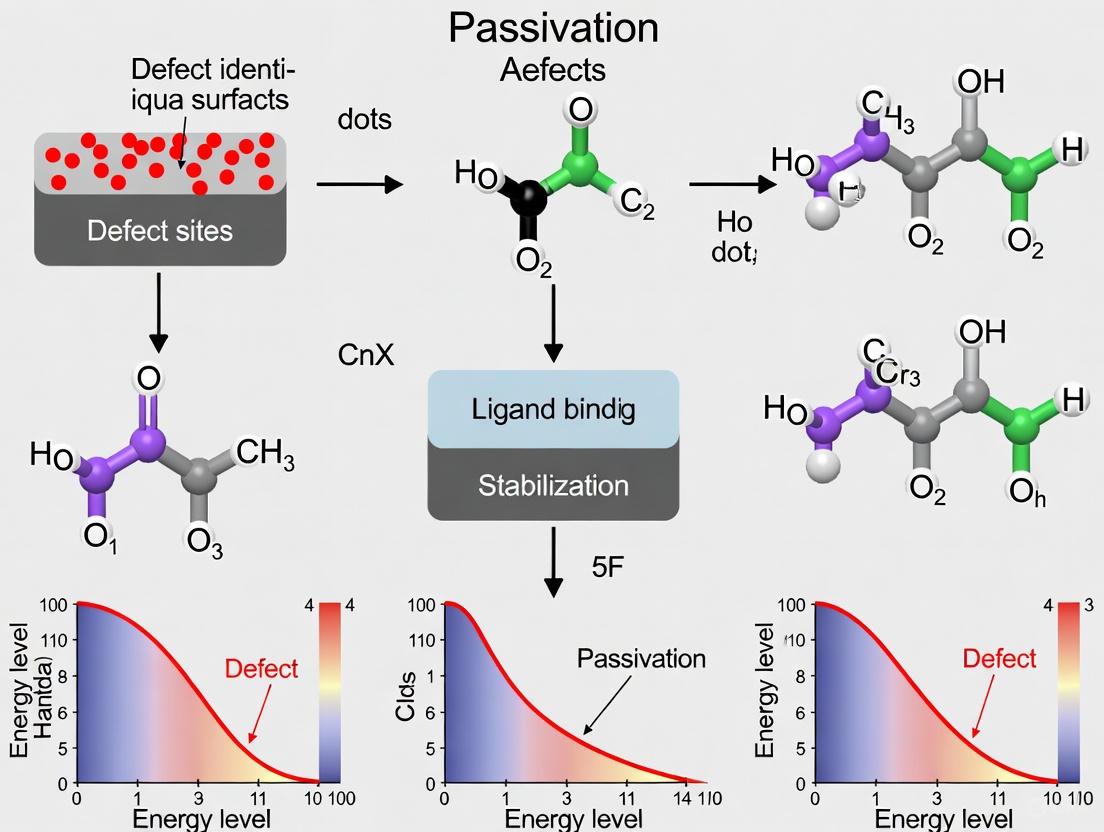

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for synthesizing and passivating CsPbBr₃ QDs, integrating the strategies discussed above.

How Defects Promote Non-Radiative Recombination and Quench Luminescence

Inorganic cesium lead bromide (CsPbBr3) quantum dots (QDs) represent a transformative class of semiconductor nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission linewidths, and tunable bandgaps [8] [9]. These characteristics make them exceptionally promising for applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar cells, lasers, and advanced sensing platforms [10]. However, their exceptional performance is critically limited by a fundamental issue: surface defects.

The ionic crystal nature and high surface-to-volume ratio of perovskite QDs make them highly susceptible to the formation of surface defects, such as halide vacancies and under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions [8] [11]. These defects create electronic trap states within the bandgap, which act as efficient centers for non-radiative recombination. In this process, photogenerated electrons and holes recombine without emitting light, releasing their energy as heat (phonons) instead. This phenomenon directly quenches luminescence, reduces PLQY, and accelerates the degradation of the nanocrystals, posing a significant bottleneck for their commercial application [8] [7]. This guide explores the mechanisms of defect-induced quenching and provides actionable, experimentally-validated passivation strategies for researchers.

Fundamental FAQs: Unraveling the Defect-Recombination Relationship

Q1: What are the primary types of defects in CsPbBr3 QDs and how do they form?

The most common and detrimental defects in CsPbBr3 QDs are ionic defects arising from their inherently low lattice formation energy and ionic character [12]. The primary defects include:

- Bromine (Br) Vacancies (V˅Br): These are the most prevalent defects due to the high mobility and relatively weak binding of halide ions. They create shallow trap states [11].

- Under-coordinated Lead (Pb) Ions: These occur when Pb²⁺ ions on the crystal surface are not fully bonded to the surrounding bromine lattice. They act as deep trap states and are potent centers for non-radiative recombination [11] [7]. These defects form readily during synthesis and are exacerbated by exposure to external environmental stimuli such as heat, light, oxygen, and moisture [8].

Q2: What is the atomic-level mechanism by which defects quench photoluminescence?

Defects introduce electronic energy levels within the forbidden bandgap of the semiconductor. When an electron in the conduction band is captured by one of these "trap states," it cannot directly recombine with a hole in the valence band to emit a photon (radiative recombination). Instead, it undergoes a multi-step non-radiative recombination process, releasing its excess energy through vibrational modes (phonons) of the crystal lattice, which manifests as heat [9]. This process effectively "steals" the energy that would otherwise produce light, leading to the observed quenching of luminescence and a decrease in the measured PLQY.

Q3: How can I experimentally confirm that non-radiative recombination is the main cause of low PLQY in my samples?

A combination of steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopic techniques is used to diagnose non-radiative recombination:

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): A shortened average carrier lifetime (τ_avg) is a direct indicator of dominant non-radiative pathways. Passivated samples with reduced defects show significantly prolonged lifetimes [11]. For instance, one study showed carrier lifetimes in CsPbBr3 films increased from 2.77 ns to 7.90 ns after effective passivation [11].

- Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (fs-TAS): This technique can directly track the cooling and trapping dynamics of photoexcited carriers, revealing the presence and density of tail states associated with defects [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core electronic processes governing luminescence quenching and the diagnostic experimental techniques.

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimentally Observed Problems and Solutions

Problem: Rapid Luminescence Quenching Under Ambient Conditions

Observation: Your CsPbBr3 QD solution or film loses fluorescence intensity within hours or days when stored in air. Root Cause: Susceptibility to environmental factors like moisture (H₂O) and oxygen (O₂) due to the ionic nature of the perovskite lattice and lack of physical isolation [8]. Solution: Hollow Silica (H-SiO₂) Encapsulation

- Principle: Physical isolation of QDs within a rigid, chemically inert, and transparent shell [8].

- Experimental Protocol (H-SiO₂ Coating):

- Synthesize Hollow Silica Microspheres via a template method using trisodium citrate in an ammonia-ethanol solution, followed by the slow addition of ethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) as the silica precursor [8].

- Grow CsPbBr3 QDs Inside H-SiO₂ using a simple sol-gel method in an aqueous solution. The QDs nucleate and attach to the interior of the hollow shell, maximizing encapsulation protection [8].

- Validated Performance:

- Retains 70% of initial fluorescence intensity after heating at 140 °C.

- Maintains 91.4% of its initial fluorescence quantum efficiency after 4 days in a humid environment [8].

Problem: Low Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) in As-Synthesized QDs

Observation: Freshly synthesized QDs have a PLQY below the theoretical maximum (<90%), indicating abundant intrinsic surface defects. Root Cause: Presence of under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide vacancies on the QD surface acting as non-radiative recombination centers [7]. Solution: Surface Passivation with Gallium (Ga³⁺) Cations

- Principle: Gallium cations (Ga³⁺) bind to the QD surface, effectively compensating for under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites and suppressing trap states [7].

- Experimental Protocol (Ga³⁺ Passivation):

- Validated Performance:

Problem: Luminescence Instability Under Light/Irradiation

Observation: QD films or devices undergo severe photoluminescence quenching under continuous illumination. Root Cause: Light-induced ion migration and accelerated defect formation, often leading to phase segregation in mixed-halide compositions [11]. Solution: Perovskite QD-Based Bulk Passivation

- Principle: Using CsPbBr3 QDs themselves as a passivator for polycrystalline perovskite films. Upon annealing, ions from the QDs diffuse into the film to fill vacancies, while the hydrophobic ligands self-assemble on surfaces and grain boundaries [11].

- Experimental Protocol (QD-Based Film Passivation):

- Disperse synthesized CsPbBr3 QDs in hexane (concentration: ~20 mg/mL) to create an anti-solvent solution [11].

- During the spin-coating of your perovskite precursor solution (e.g., CsPbIBr₂ for solar cells), use the QD-containing solution as the anti-solvent.

- Post-anneal the deposited film (e.g., at 150°C for inorganic perovskites) to facilitate the integration and passivation effect [11].

- Validated Performance:

- Suppresses light-induced phase segregation in mixed-halide perovskites.

- Improved the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of CsPbIBr₂ solar cells from 8.7% to 11.1% [11].

Quantitative Comparison of Passivation Strategies

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for the defect passivation methods discussed, providing a benchmark for experimental planning.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CsPbBr3 QD Defect Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Key Reagent/ Material | Reported PLQY Improvement | Enhanced Stability Performance | Best For Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hollow Silica Encapsulation [8] | Hollow SiO₂ microspheres | High retention of initial efficiency | 91.4% QE after 4 days in humidity; 70% intensity at 140°C | Harsh environments, anti-counterfeiting inks, displays |

| Gallium Cation Passivation [7] | Gallium Bromide (GaBr₃) | 60.2% → 86.7% | Enhanced operational stability in LED devices | High-brightness LEDs, light-emitting devices |

| Polymer Encapsulation (EVA-TPR) [12] | Ethylene Vinyl Acetate-Terpene Phenol | Improved optical stability | Enhanced physical & optical stability in composite films | Flexible optics, stable composite films & coatings |

| QD-Based Bulk Film Passivation [11] | CsPbBr3 QDs in hexane | Significant PL intensity increase | Suppressed phase segregation under light | Efficient and stable solar cells, mixed-halide perovskites |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Defect Passivation

Table 2: Key Reagents for Passivating CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Passivation | Key Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Gallium Bromide (GaBr₃) [7] | Passivates under-coordinated Pb²⁺ surface defects via cation exchange. | Optimal concentration found at ~40% Ga³⁺ relative to Pb²⁺. |

| Hollow Silica (H-SiO₂) [8] | Provides a physical barrier against H₂O and O₂, confining QDs in a rigid matrix. | Synthesized via a template method; allows large-scale aqueous synthesis. |

| Lithium Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) [13] | Passivates interface defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies in SnO₂ ETL) and improves energy level alignment. | Used in modifying the electron transport layer to reduce non-radiative recombination at interfaces. |

| Ethylene Vinyl Acetate-Terpene Phenol (EVA-TPR) [12] | A copolymer that encapsulates QDs, enhancing physical and optical stability. | Highly transparent, inexpensive, and processable via simple solvent dispersion and mild heating. |

| Oleic Acid / Oleylamine Ligands [9] [11] | Standard organic ligands for QD synthesis and surface coordination; prevent aggregation. | Ligand stability is crucial; dynamic binding can lead to desorption and defect formation. |

Advanced Workflow: Integrating Passivation into QD Synthesis and Processing

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow, integrating synthesis with the subsequent passivation strategies detailed in this guide.

Linking Surface Defects to Reduced Charge Carrier Mobility and Device Efficiency

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

FAQ 1: Why do my CsPbBr3 QD-based LEDs have low efficiency (EQE) and brightness?

Problem: Low External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) and luminance in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are primarily caused by non-radiative recombination at surface defects, which wastes energy as heat instead of light.

Solutions:

- Implement Ligand Exchange: Replace long-chain insulating ligands (like oleylamine/OAm) with shorter, more conductive passivating ligands. For example, using 3,3-diphenylpropylamine (DPPA) has been shown to passivate defects and improve carrier transport, leading to a device with an EQE of 5.04% and luminance of 2,037 cd m⁻² at 460 nm [14]. Similarly, passivation with 2-phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) can significantly suppress non-radiative recombination, resulting in a maximum current efficiency of 32.69 cd A⁻¹ and an EQE of 9.67% [15].

- Apply a Core-Shell Structure: A dual-shell structure formed by ZnF₂ post-treatment (creating a CsPbBr₃:F inner shell and a zinc-rich outer shell) can effectively suppress thermal degradation and mitigate surface defects. This approach led to a near-unity Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and a 24-fold enhancement in device lifespan for electroluminescent LEDs [6].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the poor charge carrier transport in my CsPbBr3 QD films?

Problem: Charge carrier mobility is often hindered by two factors: the presence of long, insulating organic ligands on the QD surface, and energy level misalignment at the interface with charge transport layers.

Solutions:

- Use Short-Chain Ligands: As mentioned above, short-chain ligands like DPPA and PEABr not only passivate defects but also enhance the electronic coupling between QDs, facilitating better charge transport through the film [14] [15].

- Modify the Interface: Introduce an ionic liquid (e.g., BMIMPF₆) into the hole transport layer (HTL). This treatment optimizes the interfacial energy alignment and suppresses non-radiative losses, ensuring holes can be injected into the QD layer more efficiently [14].

- Functionalize with Electronic Ligands: Grafting ferrocene carboxylic acid (FCA) onto CsPbBr₃ QDs creates a microelectric field that disrupts surface barrier energy and facilitates electron transfer, thereby boosting charge transfer dynamics [16].

FAQ 3: What can I do to prevent the thermal degradation of my CsPbBr3 QDs during device operation?

Problem: CsPbBr₃ QDs are susceptible to thermal degradation at elevated temperatures (>100°C), leading to a loss of luminescence and structural integrity, which is a critical barrier for commercial applications.

Solutions:

- Employ Inorganic Shell Engineering: The ZnF₂-induced dual-shell strategy provides exceptional thermal stability. QDs treated this way maintained their optical properties and crystallinity even after heating at 120°C for 60 minutes [6].

- Utilize Polymer Encapsulation: Embedding QDs in a robust polymer matrix like Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) can shield them from environmental stress. One study achieved a PLQY increase from 60.2% to 90.1% and significantly improved stability with optimal PMMA encapsulation [17].

- Select Ligands with High Binding Energy: The thermal degradation mechanism is linked to ligand binding energy. Research on CsₓFA₁₋ₓPbI₃ QDs shows that formulations with higher ligand binding energy exhibit better thermal stability [18].

FAQ 4: How can I achieve reproducible synthesis of ultrasmall, deep-blue emitting CsPbBr3 QDs?

Problem: Conventional methods struggle to produce monodisperse, ultrasmall CsPbBr₃ QDs with strong quantum confinement needed for pure-blue emission, often leading to uncontrolled growth and aggregation.

Solutions:

- Adopt a Spatial-Confinement Strategy: Use a metal-organic framework (MOF) like Cs-doped ZIF-8 as a template. The porous structure of ZIF-8 confines crystal growth, enabling the synthesis of monodisperse QDs as small as 1.9 nm with tunable deep-blue emission (435-515 nm) without the stability issues associated with chloride doping [14].

- Precisely Control Synthesis Temperature: The size of CsPbBr₃ QDs can be directly controlled by varying the hot-injection temperature (e.g., between 130°C and 190°C), which in turn governs the quantum confinement effect and the resulting emission wavelength [9].

The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved by different passivation strategies as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Defect-Passivated CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots and Devices

| Passivation Strategy | Material/Method Used | Key Performance Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Ligand Exchange | 3,3-Diphenylpropylamine (DPPA) | EQE: 5.04%; Luminance: 2,037 cd m⁻² (at 460 nm) [14] | [14] |

| Short-Chain Ligand Exchange | 2-Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Current Efficiency: 32.69 cd A⁻¹; EQE: 9.67% (3.88x improvement) [15] | [15] |

| Dual-Shell Engineering | ZnF₂ Post-Treatment | PLQY: ~97%; Device Lifespan: 24x enhancement [6] | [6] |

| Ligand Exchange & Interface Engineering | DPPA & Ionic Liquid in HTL | PLQY increased from 60.2% to 90.1% (with optimal PMMA encapsulation) [17] | [17] |

| Spatial-Confinement Synthesis | Cs-doped ZIF-8 MOF | Achieved ultrasmall (1.9 nm) QDs with pure-blue emission tunable down to 435 nm [14] | [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Passivation Techniques

Protocol 1: Short-Chain Ligand Passivation with PEABr

This protocol is adapted from methods used to achieve high-efficiency LEDs [15] [17].

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs: Prepare standard CsPbBr₃ QDs using the ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method at room temperature. A typical precursor solution contains PbBr₂ and CsBr dissolved in DMF, with OA and OAm as initial capping ligands.

- Prepare PEABr Solution: Dissolve PEABr powder in a solvent like ethyl acetate, often with a small amount of OA, and ultrasonicate to obtain a clear solution.

- Perform Ligand Exchange: Add the PEABr solution directly to the synthesized CsPbBr₃ QD solution. The molar ratio of PEABr to the original OAm ligand should be optimized (e.g., 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%).

- Stirring and Purification: Stir the mixture for a set period to allow the ligand exchange to occur. Purify the passivated QDs by centrifugation and redispersion in a non-polar solvent like toluene to remove excess ligands and reaction byproducts.

Protocol 2: Dual-Shell Passivation via ZnF₂ Post-Treatment

This protocol is based on a strategy to achieve exceptional thermal stability [6].

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs: Synthesize QDs using a standard room-temperature method (e.g., involving Pb²⁺ precursor, Cs-oleate, and ligands like didodecyldimethylammonium bromide/DDAB).

- Introduce ZnF₂: After the QD synthesis is complete, inject a solution of ZnF₂ inorganic ligands into the QD reaction mixture under stirring.

- Stirring and Formation: Continue stirring to allow the post-treatment reaction to proceed. During this step, the dual-shell structure forms: a CsPbBr₃:F inner shell and a zinc-rich outer shell.

- Purification: Centrifuge the solution to purify the dual-shell QDs, removing unreacted precursors and ligands.

Visualization of Defect Passivation Workflows

Defect Formation and Passivation Pathways in CsPbBr3 QDs

Experimental Workflow for High-Efficiency QD-LED Fabrication

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Passivating CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Passivation | Key Benefit / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| DPPA (3,3-Diphenylpropylamine) | Short-chain ligand for surface defect passivation and carrier transport enhancement [14]. | Reduces surface defects, improves charge transport, enables high-efficiency pure-blue LEDs [14]. |

| PEABr (2-Phenethylammonium Bromide) | Short-chain ammonium salt ligand for passivating Br⁻ vacancies and improving film morphology [15] [17]. | Suppresses non-radiative recombination, reduces film roughness, significantly boosts LED EQE [15]. |

| ZnF₂ (Zinc Fluoride) | Inorganic ligand for forming a dual-shell (CsPbBr₃:F + Zn-rich) structure [6]. | Suppresses thermal degradation, achieves near-unity PLQY, dramatically enhances device operational stability [6]. |

| FCA (Ferrocene Carboxylic Acid) | Electron-rich ligand for modulating exciton dissociation and charge transfer [16]. | Reduces surface energy barriers, facilitates multi-exciton dissociation, enhances charge transfer for photocatalysis [16]. |

| PMMA (Polymethyl Methacrylate) | Polymer for encapsulating and shielding QDs from the environment [17]. | Significantly improves air/thermal stability and increases PLQY through physical protection [17]. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., BMIMPF₆) | Additive for the hole transport layer to optimize energy level alignment [14]. | Suppresses interfacial non-radiative losses, improves hole injection efficiency into the QD layer [14]. |

Core Mechanism: Understanding Emission Line-Broadening

What is the primary cause of emission line-broadening in CsPbBr₃ quantum dots (QDs) at room temperature? Emission line-broadening in CsPbBr₃ QDs is primarily governed by the coupling of excitons (bound electron-hole pairs) to low-energy surface phonons (atomic vibrations at the QD surface). This interaction is a dominant homogeneous broadening mechanism, meaning it affects individual QDs, not just ensembles. [19]

How does quantum confinement influence this coupling? Research demonstrates a strong size dependence: smaller QDs with stronger quantum confinement exhibit broader photoluminescence (PL) linewidths. This occurs because the reduced physical dimensions enhance the coupling of the excitonic transition to surface-located phonon modes. [19]

What quantitative evidence supports this mechanism? Single QD spectroscopy and ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations reveal the direct relationship between QD size and linewidth. The table below summarizes key experimental findings for differently sized CsPbBr₃ QDs. [19]

Table 1: Emission Linewidth vs. Quantum Dot Size

| QD Edge Length (nm) | Emission Peak Energy (eV) | PL Linewidth, FWHM (meV) |

|---|---|---|

| ~6 (and smaller) | ~2.6 and higher | ~70 - 120 |

| 7 | ~2.5 | ~90 |

| 14 | ~2.3 | ~70 |

FWHM: Full Width at Half Maximum

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Symptom: Excessive Emission Line-Broadening

FAQ: My synthesized CsPbBr₃ QDs have a much broader emission linewidth than reported in literature. What could be the cause? Excessive broadening often points to unresolved surface defects that enhance exciton-phonon coupling. Inhomogeneous broadening from a significant size distribution can also contribute. The following troubleshooting table guides you through diagnosis and solutions. [19] [20] [14]

Table 2: Troubleshooting Excessive Line-Broadening

| Problem | Recommended Experiments/Analysis | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High surface defect density leading to strong coupling to surface phonons | Time-resolved PL (TRPL): Short lifetime and non-exponential decay. Temp-dependent PL: Increased linewidth at higher temps. [19] | Surface passivation: Employ short-chain ligands like 3,3-diphenylpropylamine (DPPA) or perfluoroglutaric acid (PFGA) to bind to and pacify surface trap sites. [20] [14] |

| Uncontrolled QD growth resulting in large size distribution (inhomogeneous broadening) | Ensemble vs. Single QD spectroscopy: If ensemble linewidth is much larger than single QD, size distribution is likely too broad. TEM analysis: Direct size imaging. [19] | Spatially confined synthesis: Use a metal-organic framework (e.g., ZIF-8) as a template to control nucleation and growth, yielding monodisperse QDs. [14] |

| Insufficient quantum confinement for target blue/deep-blue emission | UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy: Check for a distinct first excitonic peak. TEM: Confirm QD size is sufficiently small (<~4 nm for deep-blue). [20] [14] | Molecular etching: Use agents like diphenylalanine (FF) to gently etch larger QDs down to ultra-small sizes (< 3 nm) with robust deep-blue emission. [20] |

FAQ: After surface passivation, my QDs aggregate and lose colloidal stability. How can I prevent this? This is a common issue when replacing long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleylamine) with shorter, more conductive ones. To mitigate aggregation:

- Gradual ligand exchange: Perform the exchange in a controlled, step-wise manner rather than a single step.

- Mixed-ligand systems: Consider using a mixture of short-chain and stabilizing long-chain ligands.

- Post-exchange purification: Optimize centrifugation speeds and antisolvent choices to avoid destabilizing the QD dispersion. [14]

Symptom: Instability of Deep-Blue Emitting QDs

FAQ: My deep-blue emitting CsPbBr₃ QDs are unstable, and their emission red-shifts or quenches over time. What should I do? Ultra-small QDs for deep-blue emission have a very high surface-to-volume ratio, making them inherently more susceptible to surface defects and degradation.

- Root Cause: The high surface energy leads to dynamic surface reconstruction, ligand loss, and oxidation.

- Solution: Implement the surface passivation strategies outlined in Table 2. The use of robust passivating ligands like PFGA can effectively overcome surface defects induced by ligand detachment and improve stability against environmental factors. [20]

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Passivation via Ligand Exchange for Reduced Linewidth

This protocol details the surface passivation of CsPbBr₃ QDs using short-chain ligands to suppress exciton-surface phonon coupling. [20] [14]

- Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs using your standard hot-injection or ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method.

- Purification: Purify the crude solution by centrifugation and redispersion in an anhydrous solvent like toluene or octane to remove excess precursors and ligands.

- Ligand Exchange:

- Prepare a separate solution containing the passivating ligand (e.g., DPPA or PFGA) in a compatible solvent (e.g., DMF or acetonitrile).

- Slowly add the ligand solution to the purified QD dispersion under vigorous stirring.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for a predetermined time (e.g., 1-2 hours) at room temperature or mild heating.

- Purification: Precipitate the passivated QDs by adding an antisolvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). Recover the QDs via centrifugation and redisperse them in the desired solvent for film formation or further characterization.

- Validation: Characterize the success of passivation by measuring:

- PL Linewidth (FWHM): A significant reduction indicates successful suppression of exciton-phonon coupling.

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): An increase confirms a reduction in non-radiative recombination channels.

- FTIR Spectroscopy: To verify the binding of the new ligands to the QD surface.

Protocol 2: Single Quantum Dot Spectroscopy for Homogeneous Linewidth Measurement

This protocol is used to disentangle homogeneous (intrinsic) broadening from inhomogeneous (size distribution) broadening. [19]

- Sample Preparation: Create a sparse film of QDs to ensure isolation of individual emitters.

- Dilute the QD solution significantly with a non-solvent polymer matrix (e.g., polystyrene).

- Spin-coat the mixture onto a clean glass coverslip to form a thin film with well-separated QDs.

- Microscopy Setup: Use a home-built or commercial micro-PL setup.

- Excitation: A laser source focused to a diffraction-limited spot via a high-numerical-aperture (NA) objective.

- Detection: The emitted light from a single QD is collected through the same objective, passed through a spectrometer, and detected with a sensitive camera (e.g., CCD or EMCCD).

- Data Acquisition:

- Scan the sample stage to locate isolated, bright single QDs.

- Acquire PL spectra of individual QDs with high signal-to-noise ratio.

- Measure the FWHM of the emission peak from a single QD. This value represents the homogeneous linewidth, primarily governed by exciton-phonon coupling at room temperature.

Mechanism & Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of line-broadening and the logical workflow for its mitigation through surface passivation.

Diagram: Surface Passivation Reduces Line-Broadening

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials used in advanced synthesis and passivation strategies for achieving narrow emission linewidths in CsPbBr₃ QDs. [20] [14]

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Surface Defect Passivation

| Reagent Name | Function / Role in Passivation |

|---|---|

| 3,3-Diphenylpropylamine (DPPA) | Short-chain organic ligand used in surface ligand exchange. Passivates surface defects (e.g., Pb²⁺ vacancies), improves carrier transport, and enhances PLQY. [14] |

| Perfluoroglutaric Acid (PFGA) | Passivating ligand that effectively binds to the QD surface, overcoming defects induced by ligand detachment and reducing non-radiative recombination. [20] |

| Diphenylalanine (FF) | Molecular etchant used to strip atomic layers from larger QDs, creating ultra-small QDs with enhanced quantum confinement and deep-blue emission. [20] |

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) | A metal-organic framework (MOF) used as a spatial confinement matrix. It limits nanocrystal growth, enabling precise size control and monodisperse, ultra-small QDs. [14] |

The Critical Challenge of Defect Regeneration During QD Film Assembly

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why do my CsPbBr3 quantum dot (QD) films lose photoluminescence (PL) during the assembly process, even when using high-quality QDs? This is a classic symptom of defect regeneration. During solvent evaporation and film formation, surface ligands like oleic acid and oleylamine can detach due to their highly dynamic binding nature [21]. This creates a high density of surface defects, such as uncoordinated Pb²⁺ atoms and bromide vacancies, which act as non-radiative recombination centers, quenching the PL [21] [2].

2. What is "bilateral interfacial passivation" and why is it more effective than passivating just one side of the QD film? Bilateral interfacial passivation involves depositing a layer of passivating molecules at both the bottom and top interfaces of the perovskite QD film [21]. Defects at both interfaces with charge transport layers can capture charge carriers and cause non-radiative losses. Passivating only one side leaves the other vulnerable. Research shows that bilateral passivation drastically improves device efficiency and stability compared to unilateral methods, leading to a significant jump in external quantum efficiency (EQE) from 7.7% to 18.7% [21].

3. Can I achieve pure blue emission from CsPbBr3 QDs without using mixed halides? Yes, by leveraging strong quantum confinement. You can synthesize ultrasmall, monodisperse CsPbBr3 QDs with sizes down to ~1.9 nm. This method avoids the halide phase separation common in mixed-halide systems, enabling stable, deep-blue emission at 460 nm [14].

4. Are there synthesis methods that can inherently reduce defect regeneration? Yes, spatially confined synthesis strategies are highly effective. For example, using a cesium-doped metal-organic framework (Cs-ZIF-8) as both a Cs source and a growth template restricts nanocrystal growth and prevents overgrowth and aggregation, resulting in ultrasmall QDs with high stability and emission purity [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Significant Drop in Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) from Solution to Solid Film

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| PLQY of QD solution is >85%, but drops sharply in thin films [21]. | Ligand loss and defect regeneration during solvent evaporation and film formation [21]. | Implement a bilateral passivation strategy. After depositing the QD film, evaporate a layer of organic passivation molecules (e.g., TSPO1) on both the top and bottom interfaces of the film [21]. |

| Film exhibits low PL intensity and non-uniform morphology. | Rapid, uncontrolled crystallization and Ostwald ripening during film formation. | Employ a spatially confined growth approach using a metal-organic framework (e.g., ZIF-8) to control QD size and suppress aggregation [14]. |

| Ineffective native ligands (OA/OAm) providing incomplete surface coverage. | Perform post-synthesis ligand exchange with short-chain ligands like 3,3-Diphenylpropylamine (DPPA) or tetraoctylammonium bromide (TOAB) for a more stable and compact ligand shell [14] [22]. |

Problem 2: Poor Performance and Stability of Blue-Emitting CsPbBr3 LEDs

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to achieve pure-blue emission (<465 nm); emission is greenish. | Weak quantum confinement due to QDs that are too large [14]. | Utilize the spatial-confinement approach with Cs-ZIF-8 to synthesize ultrasmall QDs (~1.9 nm) for deep-blue emission [14]. |

| Device efficiency and color stability degrade rapidly under operation. | Halide phase separation in mixed-halide systems and interface-induced defects [14] [2]. | 1. Use pure CsPbBr3 with strong confinement instead of mixed halides [14].2. Modulate interfaces with a quasi-organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor layer to improve energy alignment and suppress non-radiative losses [14]. |

| High defect density in blue-emitting QD films. | High surface-to-volume ratio of ultrasmall QDs amplifies the impact of surface defects [14]. | Apply surface engineering with dual ligands. For example, passivate with a combination of PbBr₂ and TOAB, which has been shown to achieve a high PLQY of 96.6% in films [22]. |

Problem 3: Inefficient Charge Injection and Transport in QD Light-Emitting Diodes (QLEDs)

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low device efficiency (EQE, current efficiency) despite bright QD films. | Interfacial defects between the QD layer and charge transport layers (CTLs) hindering carrier injection and promoting non-radiative recombination [21]. | Apply the bilateral interfacial passivation strategy with molecules like TSPO1. This passivates defects at both interfaces, improving carrier injection and boosting EQE [21]. |

| Imbalanced charge injection leads to efficiency roll-off at high currents. | Energy level misalignment at the QD/CTL interfaces. | Introduce an ionic liquid (e.g., BMIMPF₆) into the hole transport layer. This optimizes the interfacial energy alignment and improves hole injection [14]. |

The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved by different defect mitigation strategies reported in recent literature.

| Passivation Strategy | Material/Reagent Used | Key Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral Interfacial Passivation | TSPO1 molecule | EQE increased from 7.7% to 18.7%; Current efficiency: 75 cd A⁻¹; Operational lifetime (T50): 15.8 h (20x improvement) [21]. | [21] |

| Spatial-Confinement Synthesis | Cs-ZIF-8 MOF matrix | Pure-blue PeLEDs: EQE of 5.04%; Luminance of 2,037 cd m⁻² at 460 nm; Enables deep-blue emission without halide mixing [14]. | [14] |

| Dual-Ligand Passivation | PbBr₂ & TOAB | PLQY of 96.6% for CsPbBr₃ QD film; Low ASE threshold of 12.6 µJ/cm² [22]. | [22] |

| Heterostructure Passivation | p-MSB Nanoplates | PLQY of heterostructure thin film increased by 200%; EQE of 9.67% for green-emitting LEDs [23]. | [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bilateral Interfacial Passivation for QLEDs

This protocol is adapted from a study that achieved an EQE of 18.7% [21].

- Substrate Preparation: Clean and treat the ITO/glass substrate with oxygen plasma.

- Deposit Hole Transport Layer (HTL): Spin-coat a layer of PEDOT:PSS onto the ITO substrate and anneal.

- First Passivation Layer: Thermally evaporate a thin layer (e.g., 2-5 nm) of the passivation molecule (e.g., TSPO1) directly onto the HTL.

- QD Film Deposition: Spin-coat the CsPbBr3 QD solution onto the passivated HTL to form the emissive layer.

- Second Passivation Layer: Thermally evaporate another layer of the passivation molecule (e.g., TSPO1) on top of the QD film.

- Complete Device Fabrication: Deposit the electron transport layer (e.g., TPBi) and the metal electrode (e.g., Al) by thermal evaporation.

Protocol 2: Spatially Confined Synthesis of Ultrasmall CsPbBr3 QDs

This protocol describes the synthesis of deep-blue emitting QDs using a MOF template [14].

- Synthesize Cs-ZIF-8:

- Combine zinc nitrate hexahydrate and 2-methylimidazole in methanol.

- Add cesium acetate to the mixture to incorporate Cs ions into the framework.

- Recover the resulting Cs-ZIF-8 crystals by centrifugation and dry.

- Prepare Precursor Solutions:

- Prepare a PbBr2 precursor in DMF with oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm).

- Prepare a Cs-ZIF-8 precursor by dispersing the synthesized Cs-ZIF-8 in a solvent.

- Synthesize CsPbBr3 QDs via LARP:

- Mix the PbBr2 precursor with a non-solvent (e.g., a hexane/isopropanol mixture).

- Quickly inject the Cs-ZIF-8 precursor into the mixture under vigorous stirring at room temperature.

- The Cs ions are released from the MOF pores, reacting with PbBr2 within the confined space to form ultrasmall, monodisperse QDs.

- Purification: Centrifuge the reaction solution to remove unreacted precursors and large aggregates. Re-disperse the QD precipitate in toluene for further use.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents used in the advanced passivation strategies discussed.

| Reagent Name | Function | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| TSPO1 (Diphenylphosphine oxide-4-(triphenylsilyl)phenyl) | Bilateral interfacial passivator [21]. | The P=O group has a strong interaction with uncoordinated Pb²⁺, effectively pacifying trap states and blocking ion migration [21]. |

| Cs-ZIF-8 | Spatial confinement matrix and cesium source [14]. | The porous framework restricts nanocrystal growth, enabling precise size control for pure-blue emitters and preventing aggregation [14]. |

| DPPA (3,3-Diphenylpropylamine) | Short-chain surface ligand [14]. | Improves carrier transport by reducing insulating ligand barrier and effectively passivates surface defects [14]. |

| PbBr₂ & TOAB Dual Ligands | Post-synthesis surface passivators [22]. | PbBr₂ compensates for Pb²⁺ vacancies, while TOAB provides Br⁻ ions to fill halide vacancies, yielding high PLQY films [22]. |

| p-MSB Nanoplates | Component for 0D-2D heterostructures [23]. | Facilitates electron transfer, significantly boosting PLQY, while its hydrophobicity enhances film stability against moisture [23]. |

| Ionic Liquid (e.g., BMIMPF₆) | Additive for hole transport layer [14]. | Modulates interfacial energy alignment, improves hole injection efficiency, and suppresses non-radiative losses at the interface [14]. |

Workflow: Bilateral Passivation Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and logical relationship of the bilateral passivation process for constructing high-performance QLEDs.

A Practical Guide to Surface Passivation Techniques: From Ligand Engineering to Core-Shell Structures

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My CsPbBr3 quantum dot (QD) films show poor surface coverage and a "coffee ring" effect during inkjet printing. What ligand strategy can mitigate this?

- Answer: The coffee ring effect, caused by uneven solute migration during droplet drying, can be suppressed by engineering the QD surface energy with specific short-chain ligand combinations.

- Recommended Solution: Utilize a mixed-ligand system of octanoic acid (OcA) and oleylamine (OAm). The branched nature of these ligands provides enhanced steric stabilization, adjusts surface tension, and reduces particle aggregation during solvent evaporation [24].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesize CsPbBr3 QDs via the hot-injection method using your chosen ligand combination (e.g., OcA/OAm) [24].

- Purify the QDs to remove excess unbound ligands.

- Formulate the printing ink by dispersing the QDs in a suitable solvent. Characterize the ink's Ohnesorge number to ensure optimal jetting characteristics [24].

- Expected Outcome: This ligand combination has been shown to achieve a high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 92% and enables the printing of high-fidelity patterns with uniform film morphology on flexible substrates [24].

Q2: How can I simultaneously improve the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and environmental stability of my CsPbBr3 QDs?

- Answer: A dual-action strategy combining chemical surface passivation with rigid matrix encapsulation is highly effective.

- Recommended Solution: Employ a sulfonic acid-based surfactant (SB3-18) for surface passivation, combined with encapsulation within a mesoporous silica (MS) matrix. The SB3-18 coordinates with unpassivated Pb²⁺ sites to suppress surface defects, while the silica matrix forms a dense protective barrier [25].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Fully grind CsBr, PbBr₂, and mesoporous silica in a mortar until homogeneous.

- Add the SB3-18 passivator to the mixture.

- Calcinate the mixture in a muffle furnace at 650 °C for 1-2 hours. This high-temperature step triggers pore collapse in the silica, encapsulating the QDs [25].

- Expected Outcome: This synergistic approach raised the PLQY from 49.59% to 58.27%. The composite retained 95.1% of its initial PL intensity after water-resistance tests and 92.9% after light radiation aging, demonstrating exceptional stability [25].

Q3: For optoelectronic devices like QLEDs, my CsPbBr3 QD-based devices suffer from inefficient carrier transport. How can ligand engineering help?

- Answer: Long, insulating native ligands hinder charge transport. Exchanging them with short, conductive ligands is crucial.

- Recommended Solution: Post-synthetic treatment with 2-phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr), a short carbon chain ligand. This passivates Br⁻ vacancies and improves the film morphology [15].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesize CsPbBr3 QDs using standard methods (e.g., with oleic acid/oleylamine).

- Perform a ligand exchange process by introducing PEABr to the QD solution.

- Purify the treated QDs and deposit them as a thin film.

- Expected Outcome: PEABr treatment can boost the PLQY of the QD film to 78.64% and drastically reduce surface roughness from 3.61 nm to 1.38 nm. This leads to highly efficient QLED devices, with one study reporting a 3.88-fold increase in current efficiency compared to control devices [15].

Q4: Can zwitterionic ligands be used for applications beyond display technologies, such as photocatalysis?

- Answer: Yes, zwitterionic ligands are highly versatile. For example, they can be engineered to modify the surface charge of QDs, which is beneficial for photocatalysis.

- Recommended Solution: Implement a post-synthetic ligand exchange using zwitterionic sulfobetaine (ZSB) ligands. These ligands passivate surface defects and can induce a negative surface potential on the QDs, facilitating better electron transfer to a co-catalyst [26].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesize and purify CsPbBr3 QDs, removing excess native ligands.

- Redisperse the QDs in toluene and add ZSB powder.

- Vigorously stir the mixture at room temperature to allow ligand exchange.

- Purify the ZSB-capped QDs for subsequent integration into photocatalytic systems, such as with Pt-TiO₂ [26].

- Expected Outcome: ZSB capping enhances PLQY and photostability. More importantly, it creates a kinetically favorable band alignment at the heterojunction with the co-catalyst, leading to a threefold increase in electron transfer rates and significantly enhanced H₂ production rates under visible light [26].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different ligand strategies as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ligand Strategies for CsPbBr3 QDs

| Ligand Strategy | Key Function | Reported PLQY | Key Stability/Performance Metric | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB3-18 / Mesoporous Silica [25] | Defect passivation & rigid encapsulation | 58.27% (up from 49.59%) | Retains 95.1% PL after water exposure | Wide color gamut displays |

| OcA / OAm Ligands [24] | Surface energy control & steric stabilization | 92% | Suppresses coffee ring effect; enables high-resolution printing | Inkjet-printed flexible displays |

| PEABr Ligand [15] | Bromine vacancy passivation & morphology control | 78.64% | Film roughness reduced to 1.38 nm; QLED efficiency increased 3.88-fold | Electroluminescent QLEDs |

| Zwitterionic Sulfobetaine (ZSB) [26] | Defect passivation & surface charge modulation | Enhanced (vs. native ligands) | 3x higher electron transfer rate for H₂ production | Photocatalysis |

| Designer Phospholipid (PEA) [27] | Lattice-matched zwitterionic binding | >96% | High colloidal integrity for months; ~94% average ON fraction | High-purity emitters, single-photon sources |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Temperature Solid-State Synthesis for SB3-18/MS Composites [25]

- Objective: To create highly stable and efficient CsPbBr3 QD composites via synergistic surface passivation and matrix encapsulation.

- Materials: CsBr, PbBr₂, mesoporous silica (MS), SB3-18 surfactant, agate mortar, muffle furnace.

- Procedure:

- Weigh CsBr and PbBr₂ in a 1:1 molar ratio. Weigh MS so that the mass ratio of

(CsBr + PbBr₂) : MSis 1:3. - Combine the precursors and MS in an agate mortar and grind thoroughly until a homogeneous mixture is achieved.

- Add a controlled amount of the SB3-18 sulfonic acid surfactant to the mixture and continue grinding.

- Transfer the mixture to an alumina crucible and calcinate in a muffle furnace at 650 °C for 1 hour under an air atmosphere.

- After the furnace cools to room temperature, collect the final solid product for characterization and application.

- Weigh CsBr and PbBr₂ in a 1:1 molar ratio. Weigh MS so that the mass ratio of

Protocol 2: Post-Synthetic Ligand Exchange with Zwitterionic Sulfobetaine (ZSB) [26]

- Objective: To replace native long-chain ligands with ZSB ligands for enhanced charge transfer and photocatalytic performance.

- Materials: Synthesized CsPbBr3 QDs (washed), toluene, ZSB ligand powder, methyl acetate, stirring equipment, centrifuge.

- Procedure:

- QD Preparation: Synthesize CsPbBr3 QDs via the hot-injection method. Wash the as-synthesized QDs with methyl acetate (anti-solvent) and centrifuge to remove excess oleic acid and oleylamine. This step is critical for creating binding sites for new ligands.

- Ligand Exchange: Redisperse the washed QD pellet in toluene at a concentration of ~3 mg/mL. Add ZSB powder directly to this QD solution.

- Reaction: Vigorously stir the mixture at room temperature for several hours to allow the ZSB ligands to exchange with the remaining native ligands on the QD surface.

- Purification: Purify the ZSB-capped QDs by centrifugation and redispersion to remove any unbound ligands. The resulting QDs can be used for film formation or dispersed in solvents for photocatalytic ink formulation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Ligand Engineering Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfonic Acid Surfactant (SB3-18) [25] | Surface passivator that coordinates with unsaturated Pb²⁺ ions to suppress trap states. | Effective in high-temperature solid-state synthesis. |

| Mesoporous Silica (MS) [25] | A rigid template that collapses at high temperature to form a protective matrix around QDs. | Provides a physical barrier against moisture and oxygen. |

| Short-Chain Ligands (OcA, OAm, PEABr) [24] [15] | Modulate surface energy and improve charge transport by reducing insulating ligand layer thickness. | Short chains (e.g., PEABr) reduce film roughness and current leakage in devices [15]. |

| Zwitterionic Ligands (ZSB, Phospholipids) [26] [27] | Provide strong, charge-neutral surface binding, passivating defects while allowing good charge/energy transfer. | The head group structure (e.g., primary ammonium vs. quaternary) is critical for geometric fit on the NC surface [27]. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) [27] | A coordinating solvent/ligand used in room-temperature synthesis, later displaced by target ligands. | Serves as a weakly bound initial ligand for post-synthetic exchange. |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for applying ligand engineering strategies to enhance CsPbBr3 QD performance, integrating the solutions discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Ligand Engineering Workflow for CsPbBr3 QD Optimization.

The mechanism by which zwitterionic ligands, such as designer phospholipids, bind to the QD surface is key to their performance. The following diagram details this atomistic binding mode.

Diagram 2: Atomistic Binding Mechanism of a Zwitterionic Ligand.

All-inorganic CsPbBr₃ perovskite quantum dots (QDs) are promising materials for next-generation optoelectronics, from light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to photodetectors. However, their high surface-to-volume ratio makes them particularly susceptible to surface defects, which act as charge traps that degrade performance. These defects, often stemming from lead and bromine vacancies, cause significant reductions in photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and accelerate the degradation of the nanocrystals. Cationic passivation has emerged as a powerful strategy to heal these atomic-scale imperfections. This technique involves incorporating metal cations to suppress non-radiative recombination and improve the intrinsic stability of the QDs, forming the foundation for more reliable and efficient devices.

Key Mechanisms: How Cationic Passivation Works

The incorporation of foreign metal cations, such as gallium (Ga³⁺), addresses the root causes of instability and poor optoelectronic performance in CsPbBr₃ QDs.

- Surface Defect Passivation: The primary mechanism involves the interaction of the introduced cations with the labile surface of the QDs. Research shows that Ga³⁺ cations effectively passivate surface defects, which are non-radiative recombination centers. This passivation directly enhances the radiative recombination of charge carriers [7].

- Crystalline Quality Improvement: The incorporation of gallium cations has been linked to an improvement in the overall crystalline quality of the CsPbBr₃ QDs. This suggests that the cations integrate into the surface structure, promoting a more ordered and less defective crystal lattice [7].

- Stoichiometry and Ligand Management: A related strategy for healing surfaces involves post-synthetic treatment with lead bromide (PbBr₂) and alkylammonium bromides (e.g., didodecyldimethylammonium bromide). This treatment repairs surface lead and bromine vacancies and restores the protective ligand shell, which is crucial for colloidal stability. This combined approach has been shown to recover PLQYs to values exceeding 95% [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of how introduced cations heal surface defects on a quantum dot.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful cationic passivation requires a specific set of chemical reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions in a typical experimental workflow for passivating CsPbBr₃ QDs.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Cationic Passivation of CsPbBr₃ Quantum Dots

| Reagent | Function/Role in Passivation | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Gallium Precursors (e.g., Gallium nitrate hydrate) | Source of Ga³⁺ cations for surface defect passivation; improves crystallinity and enhances radiative recombination [7]. | Incorporated during synthesis or via post-synthetic treatment; concentration must be optimized. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Replenishes lead and bromide ions at the surface; repairs vacancies and helps restore the integrity of the PbBr₆ octahedra [28]. | Used in post-synthetic treatments; often combined with ammonium bromides for synergistic effect. |

| Alkylammonium Bromides (e.g., Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide - DDAB) | Provides halide ions and bulky organic cations; helps maintain charge balance and colloidal stability via steric repulsion [28]. | Critical for forming a stable ligand shell and preventing QD aggregation. |

| Cesium Oleate / Cesium Carbonate | Standard precursor for the cesium component in hot-injection synthesis of CsPbBr₃ QDs. | Forms the A-site cation of the perovskite lattice (ABX₃). |

| Guanidinium Bromide (GABr) | An organic cation passivator; its highly symmetrical structure can passivate defects at the surface and grain boundaries, forming a stable bromine-rich surface [29]. | Can be introduced in-situ during synthesis; improves environmental stability. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Gallium Cation Passivation Protocol

The following workflow details a method for passivating CsPbBr₃ QDs with gallium cations, based on published research [7].

Detailed Methodology:

- QD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs using the standard hot-injection method. This typically involves preparing a cesium oleate precursor and injecting it into a hot (150-200 °C) solution containing lead bromide (PbBr₂) and ligands (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine) in a non-polar solvent [29].

- Gallium Incorporation: Introduce the gallium precursor (e.g., gallium nitrate hydrate) into the perovskite precursor solution during the hot-injection process. The Ga³⁺ cations are incorporated into the QD surface during crystal growth.

- Purification: Isolate the passivated QDs through centrifugation. Wash the pellet with a non-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or methyl acetate) to remove unreacted precursors and excess ligands.

- Characterization: Characterize the optical properties of the passivated QDs. Key metrics include:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure the efficiency of light emission.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Analyze absorption onset and QD concentration.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Confirm crystal structure and phase purity.

Quantitative Outcomes of Passivation Strategies

The effectiveness of cationic passivation is quantified through key performance metrics. The table below summarizes the improvements achieved by different strategies as reported in the literature.

Table 2: Performance Outcomes of Different Passivation Strategies for CsPbBr₃ QDs

| Passivation Strategy | Reported Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Key Improvement / Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine (Unpassivated) CsPbBr₃ QDs | ~60% | Baseline performance | [7] |

| Ga³⁺ Cation Passivation | ~87% | Enhanced radiative recombination and carrier mobility; LED max. brightness: 11,777 cd/m² [7]. | [7] |

| PbBr₂ + DDAB Treatment | 95-98% | Nearly complete surface trap healing; excellent colloidal durability survives multiple washing cycles [28]. | [28] |

| In-situ Guanidinium Bromide (GABr) | Not Specified | Improved environmental stability and crystallinity; formation of a stable bromine-rich surface [29]. | [29] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: I incorporated gallium cations, but my PLQY decreased instead of improving. What could have gone wrong?

- Cause: The most likely cause is an incorrect concentration of the gallium precursor. An excess of dopant can create new defects or distort the crystal lattice, acting as new non-radiative recombination centers.

- Solution: Perform a doping series experiment. Systematically vary the molar ratio of the gallium precursor to PbBr₂ (e.g., from 5% to 40%) to identify the optimal concentration that maximizes PLQY for your specific synthetic setup [7].

Q2: My passivated QDs are aggregating and losing colloidal stability during purification. How can I prevent this?

- Cause: Aggregation indicates an incomplete or damaged ligand shell. The passivation process or subsequent washing may have stripped the protective organic ligands.

- Solution: Ensure a robust ligand environment by using a combination of passivators. Introduce alkylammonium bromides (e.g., DDAB) alongside your metal cation. The bulky organic chains provide steric repulsion that keeps QDs dispersed. A post-synthetic treatment with PbBr₂ and DDAB has been shown to greatly improve colloidal durability [28].

Q3: The emission from my Ga³⁺-passivated QD-based LED degrades rapidly during operation. What can I do to improve stability?

- Cause: Operational instability is complex, but can be linked to residual surface defects or ion migration under an electric field.

- Solution: Beyond initial passivation, focus on device structure and encapsulation. The Ga³⁺ passivation itself has been shown to enhance operational stability relative to pristine devices [7]. Ensure efficient charge transport layers in your LED to prevent charge accumulation at the QD layer. Finally, hermetically seal the finished device to protect it from oxygen and moisture.

Q4: Are there alternatives to gallium for cationic passivation?

- Answer: Yes, the principle of cationic passivation extends to other ions. Research has explored trivalent cations like Gd³⁺ and Sc³⁺ for passivating other metal oxides, where they help inactivate oxygen vacancies [30]. In perovskite QDs, various B-site metal ions including alkaline-earth metals (Sr²⁺), transition metals (Zn²⁺, Mn²⁺), and rare-earth metals have been investigated for improving stability and optical properties [29]. The choice of cation depends on its ionic radius, charge, and how it integrates into or interacts with the host lattice.

In the research of CsPbBr₃ quantum dots (QDs), achieving high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and operational stability is paramount for applications in LEDs, solar cells, and lasers. A primary obstacle is the presence of surface defects, particularly bromine vacancies, which act as trap states for charge carriers. These traps promote non-radiative recombination, significantly reducing the efficiency and stability of the nanocrystals [7] [31]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers employing anionic treatments with PbBr₂ and ammonium bromide salts to passivate these critical defects, a strategy grounded in the broader thesis of enhancing optoelectronic properties through surface engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are bromine vacancies a major concern in CsPbBr₃ QDs? Bromine vacancies are inherent surface defects that create shallow trap states. These states capture excited charge carriers (electrons and holes) and facilitate non-radiative recombination, a process that wastes energy as heat instead of light. This results in a lower PLQY, reduced charge carrier lifetimes, and can diminish the performance and stability of final devices [31].

Q2: What is the fundamental mechanism behind using bromide salts for passivation? The treatment functions by providing a source of bromide ions (Br⁻) to fill the vacant bromine lattice sites on the surface of the CsPbBr₃ QDs. This surface binding reduces the density of trap states by completing the crystal lattice, which in turn suppresses non-radiative recombination pathways and enhances radiative recombination, leading to brighter and more efficient light emission [31].

Q3: My treatment has caused a drop in PLQY or particle aggregation. What went wrong? A drop in PLQY or observable aggregation often points to two common issues:

- Excessive Ion Concentration: An overly high concentration of the bromide salt can lead to surface etching or damage of the QDs, creating new defects instead of healing existing ones.

- Polar Solvent Incompatibility: CsPbBr₃ QDs are sensitive to polar environments. Using a treatment solvent that is too polar can strip the native insulating ligands (like oleic acid and oleylamine), destabilizing the colloidal suspension and causing aggregation or precipitation.

Q4: How can I conclusively confirm that bromine vacancies have been passivated? Passivation success is verified through a combination of optical and structural characterization techniques. Key indicators include a significant increase in absolute PLQY and a lengthening of the average photoluminescence (PL) lifetime, both suggesting reduced non-radiative recombination. Advanced techniques like X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can detect changes in surface composition, while elemental analysis via techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) can track an increased Br:Pb ratio post-treatment [31].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased PLQY after treatment | Surface etching from excessive bromide ion concentration. | Titrate the treatment solution to find the optimal, lower concentration. |

| QD Aggregation or Precipitation | Colloidal destabilization from polar solvents or violent mixing. | Use milder solvents, ensure slow, dropwise addition with gentle stirring. |

| No Improvement in PLQY | Incomplete passivation; wrong binding chemistry. | Verify reagent freshness, explore alternative ammonium salts (e.g., didodecyldimethylammonium bromide). |

| Worsened Stability vs. Air/Moisture | Ligand stripping during treatment. | Consider a post-treatment ligand exchange step to restore a protective surface layer. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Protocol 1: Direct Solution-Phase Treatment with PbBr₂

This method aims to provide both Pb²⁺ and Br⁻ ions, which may help in passivating lead-related sites while also filling bromine vacancies.

- Stock Solution Preparation: Dissolve a precise amount of PbBr₂ (e.g., 10 mM) in a compatible solvent such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or a DMSO/octane mixture. Gently heat and sonicate to ensure complete dissolution.

- QD Solution Preparation: Standardize the concentration of your purified CsPbBr₃ QDs in a non-polar solvent like hexane or toluene to an optical density (OD) at the first excitonic peak.

- Treatment Procedure: Under an inert atmosphere and with vigorous stirring, add the PbBr₂ stock solution to the QD solution dropwise. The typical recommended molar ratio of PbBr₂:QDs is 10:1 to 100:1.

- Reaction and Purification: Allow the reaction to proceed for 1-5 minutes. Subsequently, precipitate the treated QDs by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or methyl acetate) and centrifuge. Redisperse the pellet in a clean non-polar solvent for characterization.

Protocol 2: Ligand-Assisted Surface Treatment with Ammonium Bromide

This approach utilizes ammonium bromide salts, where the ammonium cation can assist with surface binding and the bromide anion fills the vacancies.

- Salt Solution Preparation: Dissolve an ammonium bromide salt (e.g., didodecyldimethylammonium bromide or tetraoctylammonium bromide) in a minimal volume of a moderately polar solvent that is miscible with the QD dispersion, such as toluene or chloroform.

- QD Solution Preparation: Standardize the CsPbBr₃ QD concentration as in Protocol 1.

- Treatment Procedure: Add the ammonium bromide solution to the QDs dropwise with stirring. A typical molar ratio of ammonium bromide:QDs is 50:1 to 500:1.

- Incubation and Purification: Let the mixture incubate for 10-30 minutes at room temperature. Purify the QDs via centrifugation and redispersion.

Expected Quantitative Outcomes

The table below summarizes the typical performance enhancements observed in successfully passivated CsPbBr₃ QDs.

| Performance Metric | Pre-Treatment (Typical Range) | Post-Treatment (Expected Outcome) | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute PLQY | ~60% | Increase to >85% - near-unity [7] [31] | Integrating sphere measurement [31] |

| Average PL Lifetime (τ_avg) | < 10 ns | Significant increase to >20 ns [32] | Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) [32] |

| FWHM (Full Width at Half Maximum) | ~20 nm | Slight narrowing, improved color purity | Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy |

| Stability (PLQY retention) | < 50% after 7 days | > 80% after 7 days [33] | Under constant illumination/ambient conditions |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cesium Oleate | Cesium precursor for CsPbBr₃ QD synthesis [32] |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead and bromide precursor; source of Br⁻ ions for vacancy filling [32] |

| Ammonium Bromide Salts | Source of Br⁻ ions for passivation; ammonium group aids surface binding [31] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) | Surface ligands to control growth and provide colloidal stability [32] |

| Octadecene (ODE) | High-booint solvent for high-temperature synthesis [32] |

| Urea-Ammonium Thiocyanate (UAT) | Ionic liquid for advanced thiocyanate-based surface treatment [31] |

Experimental Workflow and Defect Passivation Mechanism

The following diagrams illustrate the procedural workflow and the atomic-scale mechanism of defect passivation.

Experimental Workflow for Anionic Treatment

Atomic Mechanism of Bromine Vacancy Passivation

All-inorganic cesium lead bromine perovskite quantum dots (CsPbBr3 QDs) represent an emerging class of semiconductor nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY), tunable narrow-band emission, and superior defect tolerance. These characteristics make them promising candidates for various technological applications, including light-emitting diodes (QLEDs), wide color gamut displays, and photodetectors. However, the practical deployment of CsPbBr3 QDs is fundamentally limited by their inherent environmental instability. The defect-rich surfaces of CsPbBr3 QDs, arising from an intrinsically soft lattice and low defect formation energy, are highly susceptible to degradation triggered by moisture, elevated temperature, and oxygen, leading to accelerated material breakdown and rapid performance decline. Surface lead defects, particularly unpassivated Pb2+ sites and bromine vacancies, aggravate non-radiative recombination, which results in diminished PLQY and poor luminescence stability. The CsPbBr3@CsPb2Br5 core-shell heterostructure approach has emerged as a transformative strategy to overcome these limitations through synergistic physical encapsulation and chemical passivation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for CsPbBr3@CsPb2Br5 Composite Synthesis

| Reagent Name | Chemical Function | Role in Composite Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Lead and bromine source | Primary precursor for CsPbBr3 crystal formation; excess amounts drive peritectic reaction for shell formation |

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cesium source | Forms Cs-oleate precursor for perovskite synthesis |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand | Coordinates with Pb²⁺ sites; assists in crystal growth stabilization |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Surface ligand | Enhances solubility and controls crystal growth dynamics |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-polar solvent | High-boiling point solvent for hot-injection synthesis |

| Zinc Bromide (ZnBr₂) | Additive/passivator | Provides Br-rich environment; passivates bromine vacancies [34] [35] |

| Dodecylbenzenesulfonic Acid (DBSA) | Sulfonic acid surfactant | Coordinates with unpassivated Pb²⁺ sites; suppresses Ostwald ripening [35] |

Experimental Protocol: Pseudo-Peritectic Method for Core-Shell Construction

The pseudo-peritectic method represents a significant advancement for achieving water-resistant, monodispersed, and stably luminescent CsPbBr3@CsPb2Br5 nanocrystals. This method essentially creates a peritectic reaction in solutions, mimicking the solid-state phase transformation observed in the CsBr-PbBr2 phase diagram where CsPb2Br5 is the peritectic product of CsPbBr3 and PbBr2 [36].

Step-by-Step Synthesis Procedure

CsPbBr3 Core Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbBr3 nanocrystals using the standard solvothermal method. Specifically, prepare a Cs-oleate precursor by dissolving Cs₂CO₃ (0.4 g) in a mixture of OA (5 mL) and ODE (15 mL) with vacuum drying at 120°C for 1 hour followed by heating under N₂ protection to 140°C until complete dissolution. Simultaneously, prepare the lead precursor by mixing ODE (10 mL), PbBr₂ (0.138 g), oleylamine (2 mL), and OA (2 mL) in a separate flask with vacuum drying at 120°C for 1 hour. Inject the Cs-oleate precursor into the lead precursor solution at elevated temperature (typically 140-180°C) to initiate rapid nucleation and growth of CsPbBr3 QDs [36] [37].

PbBr2 Solution Preparation: Dissolve additional PbBr₂ in a mixture of coordinating solvents (e.g., ODE, OA, OAm) at elevated temperature to create a reactive Pb²⁺ source for the peritectic reaction.

Core-Shell Formation: Inject the pre-synthesized CsPbBr3 nanocrystals into the PbBr₂ solution. The peritectic reaction between CsPbBr3 and PbBr₂ occurs in the solution according to the equation: CsPbBr₃ + PbBr₂ ⇔ CsPb₂Br₅ [36].

Reaction Control: Maintain the reaction at temperatures between 140-180°C for specific durations (typically 1-2 hours) to control the thickness and uniformity of the CsPb2Br5 shell. The transformation follows a "Survival of the Fittest" mechanism where smaller or defective crystals dissolve while more stable structures grow [36].

Purification and Collection: Purify the resulting CsPbBr3@CsPb2Br5 nanocrystals by adding anti-solvents (such as acetone or hexane) followed by centrifugation. Redisperse the final product in non-polar solvents like toluene or hexane for further characterization and application.

Synthesis Workflow for CsPbBr3@CsPb2Br5 Core-Shell Nanocrystals

Mechanism of Defect Passivation in Core-Shell Structures

The CsPbBr3@CsPb2Br5 core-shell architecture enhances stability and optical properties through multiple synergistic mechanisms. The structural relationship between these phases creates a unique passivation scheme that addresses the fundamental instability issues of CsPbBr3 QDs.

Defect Passivation Mechanism in Core-Shell Heterostructures