Advanced Immobilization Strategies to Reduce Surface Drift: From Fundamental Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of surface drift phenomena and the immobilization strategies developed to mitigate it, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical engineering.

Advanced Immobilization Strategies to Reduce Surface Drift: From Fundamental Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of surface drift phenomena and the immobilization strategies developed to mitigate it, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical engineering. Surface drift, the unintended movement of materials from functionalized surfaces, presents significant challenges in biosensing accuracy and drug delivery efficacy. We explore the fundamental mechanisms of drift, including particle dynamics and interfacial interactions. The review systematically covers advanced methodological approaches such as surface functionalization, covalent bonding, and nanomaterial engineering. Practical guidance for troubleshooting common issues like baseline instability is included, alongside rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of technique performance. By synthesizing knowledge across disciplines, this content serves as an essential resource for developing robust, drift-resistant biomedical interfaces.

Understanding Surface Drift: Fundamental Mechanisms and Impact on Biomedical Systems

Surface drift, the unwanted movement or instability of molecules attached to a surface, is a critical parameter influencing the performance and reliability of technologies ranging from analytical biosensors to therapeutic drug delivery systems. In surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensing, baseline drift complicates data analysis and can lead to erroneous kinetic measurements [1]. In drug delivery, the uncontrolled drift of an immobilized therapeutic enzyme from its carrier can reduce efficacy and increase side effects [2]. This article frames the control of surface drift within the broader thesis that advanced immobilization strategies are fundamental to stabilizing surface-bound biomolecules, thereby enhancing the accuracy of diagnostic tools and the therapeutic profile of medicinal agents. The following sections provide quantitative comparisons, detailed protocols, and visual frameworks to guide researchers in minimizing surface drift.

Table 1: Impact of Antibody Immobilization Strategy on SPR Biosensor Performance for Shiga Toxin Detection

| Immobilization Strategy | Dissociation Constant (KD) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Preserved Binding Efficiency | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent (Non-oriented) | 37 nM | 28 ng/mL | 27% | Simple chemistry |

| Protein G (Oriented) | 16 nM | 9.8 ng/mL | 63% | Maximized paratope accessibility |

| Free Antibody-Antigen (Baseline) | 10 nM | - | 100% (Reference) | Native binding function |

Table 2: Comparison of Immobilization Techniques for Therapeutic Enzymes

| Immobilization Method | Example Support | Example Enzyme | Key Performance Metric | Implication for Drift/Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrapment | Chitosan hydrogel beads | Lipase | ~51% entrapment efficiency [2] | Low solubility prevents premature release; pH-dependent drift risk |

| Adsorption | Polyhydroxyalkanoate | Nattokinase | 20% activity increase post-immobilization [2] | Stable for 25 days at 4°C, indicating low desorption |

| Covalent Attachment | Fe3O4@chitosan | Penicillin G Acylase | Improved thermal stability & reusability [2] | Strongest resistance to leaching and drift |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Protein G-Mediated Oriented Antibody Immobilization for SPR

This protocol is designed to minimize surface drift and maximize binding site availability for Shiga toxin detection [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- SPR gold chip sensor

- 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA)

- Absolute ethanol

- Protein G

- N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) / N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC)

- Anti-Shiga toxin B subunit (anti-Stxb) antibody

- Ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5)

- Regeneration buffer: 15 mM NaOH with 0.2% (w/v) SDS

- Running buffer: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% (v/v) Tween 20 (pH 7.4)

- Acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5)

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Surface Cleaning: Clean the SPR gold disk sensor thoroughly using piranha solution (3:1 v/v 98% H2SO4:30% H2O2). Caution: Piranha solution is highly corrosive and must be handled with extreme care.

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation: Incubate the cleaned chip overnight at room temperature in a 1 mM solution of 11-MUA in ethanol. Rinse the chip three times with absolute ethanol and three times with deionized water, then dry under a stream of nitrogen.

- System Setup: Insert the functionalized chip into the SPR instrument, perform optical alignment, and stabilize the surface by flowing acetate buffer for 45 minutes.

- Surface Activation: Activate the carboxyl groups on the SAM by injecting a freshly prepared mixture of 400 mM EDC and 100 mM NHS for 300 seconds.

- Protein G Immobilization: Immobilize Protein G (25 µg/mL in acetate buffer) onto the activated surface using standard amine coupling. This creates the foundation for oriented antibody capture.

- Antibody Capture: Inject the anti-Stxb antibody (40 µg/mL) as the secondary ligand, allowing it to form an oriented complex with the pre-immobilized Protein G via specific Fc-region binding.

- Surface Blocking and Regeneration: Block any remaining active esters by injecting 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 600 seconds. Treat the surface with regeneration buffer for 120 seconds to remove any non-covalently bound material. Rinse thoroughly with running buffer between each step.

Protocol: Entrapment of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) in Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) Hydrogel for Wound Healing

This protocol demonstrates an immobilization method to control the drift of a therapeutic enzyme for sustained local delivery [2].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

- Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC)

- Alginate (optional, for forming network beads)

- Cross-linking agents (as required for the specific hydrogel formulation)

- Buffers suitable for the enzyme and hydrogel preparation

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Hydrogel Preparation: Prepare a CMC hydrogel solution according to the desired formulation. Graft copolymerization with other moieties may be performed to adjust solubility and release profiles.

- Enzyme Entrapment: Mix the SOD enzyme thoroughly into the hydrogel matrix under gentle conditions to avoid denaturation.

- Formation and Stabilization: Form the enzyme-loaded hydrogel into the final application format (e.g., beads, sheet). Cross-link the structure to solidify the matrix and entrap the enzyme fully.

- In-Vitro Validation: Apply the SOD-CMC hydrogel to an ex-vivo wound model (e.g., open wounds on the backs of rats). Monitor the wound healing time and compare it to controls (native SOD and untreated wounds) to validate efficacy and controlled release.

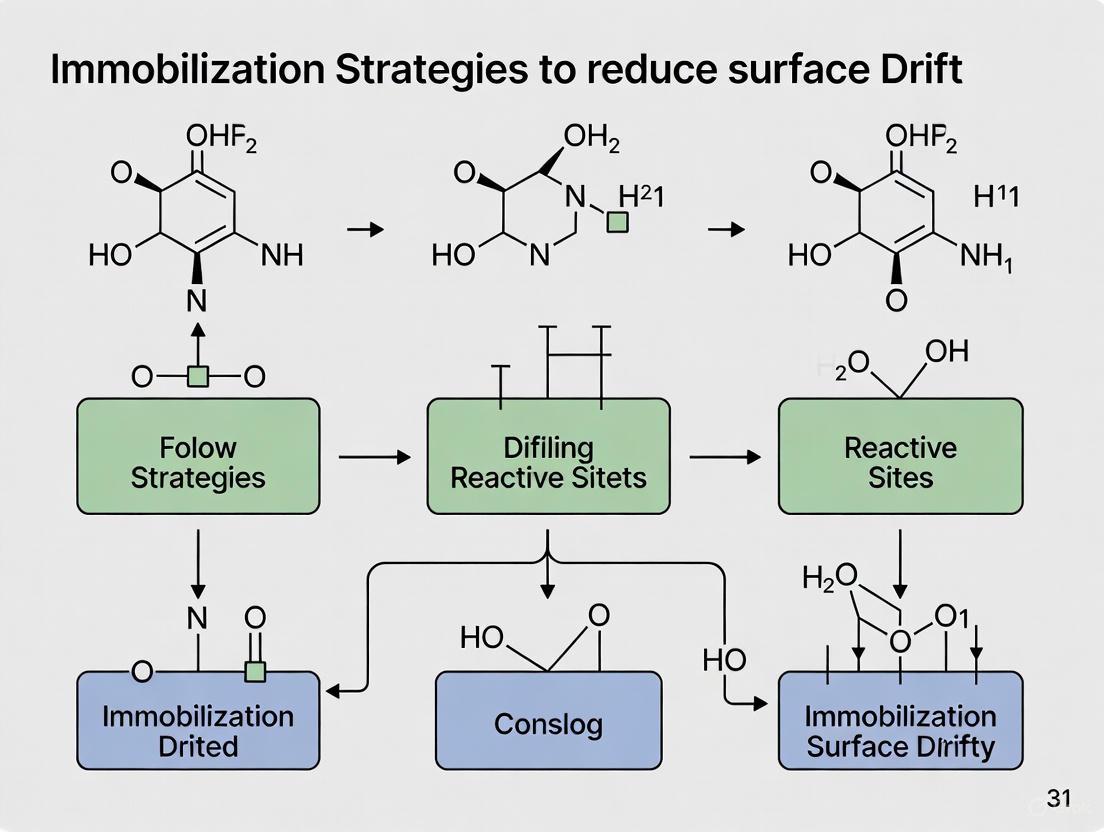

Visualizing Strategies and Workflows

Diagram: Immobilization Strategies to Mitigate Surface Drift

Diagram: SPR Experimental Workflow with Drift Control

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Surface Immobilization and Drift Control

| Item | Function and Relevance to Drift Control |

|---|---|

| Protein G | Bioaffinity ligand for oriented antibody immobilization on biosensor chips. Drift Reduction: By directing the Fc region of antibodies to the surface, it maximizes antigen-binding site availability and minimizes non-specific, unstable attachments that contribute to drift [3]. |

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) | A thiol compound that forms a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on gold surfaces, providing a stable, functionalizable base layer with carboxyl groups for subsequent immobilization chemistry [3]. |

| NHS/EDC Crosslinker Kit | Standard reagents for activating carboxyl groups to form stable amide bonds with primary amines in proteins. Drift Reduction: Creates strong covalent linkages that directly resist leaching and surface dissociation [3] [2]. |

| Chitosan & CMC Hydrogels | Natural polymer matrices for the entrapment of therapeutic enzymes. Drift Reduction: Physically confines the enzyme, controlling its release rate and protecting it from degradation and rapid clearance in vivo [2]. |

| HEPES-NaCl-EDTA-Tween Buffer | A common running buffer for SPR. Drift Reduction: Contains a detergent (Tween 20) to minimize non-specific adsorption and chelating agents (EDTA) to improve buffer stability, both contributing to a cleaner baseline [3] [1]. |

In fields ranging from drug development to biosensing, controlling the behavior of particles and molecules at interfaces is paramount. The random, incessant motion of microscopic particles, known as Brownian motion,, is a fundamental physical phenomenon that dominates the dynamics at these scales [4]. For applications that rely on precise measurements or reactions at surfaces, such as biosensors or immobilized biocatalysts, this motion can manifest as unwanted surface drift, reducing accuracy and efficiency [5] [6]. This application note details the core mechanisms of particle dynamics and Brownian motion, explains their contribution to surface drift and provides structured experimental data and protocols. The content is framed within the overarching thesis that a mechanistic understanding of these forces is a prerequisite for designing effective immobilization strategies to mitigate drift and enhance the performance of biomedical and analytical devices.

Core Theoretical Frameworks

The Fundamentals of Brownian Motion

Brownian motion describes the random movement of a small particle suspended in a fluid due to constant bombardment by surrounding fluid molecules [4]. A key quantitative descriptor is the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF), defined as ( C(t) = \langle v(0) \cdot v(t) \rangle ), which measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time [7] [4]. In an unbounded, bulk liquid, the VACF of a spherical particle exhibits a characteristic long-time decay proportional to ( t^{-3/2} ), a signature of hydrodynamic memory effects [7].

The mean-squared displacement (MSD), another critical metric, quantifies the average distance a particle travels over time. For free diffusion in one dimension, it is given by: [ \langle \Delta x^2(t) \rangle = 2Dt ] where ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient [4]. This relationship is a hallmark of purely diffusive motion.

The Critical Role of Interfaces and Confinement

When a Brownian particle approaches a solid boundary, its motion is fundamentally altered. Hydrodynamic interactions between the particle, the fluid, and the interface lead to a dramatic change in the VACF. As demonstrated through large-scale molecular dynamics simulations, the classic ( t^{-3/2} ) decay is replaced by a much faster ( t^{-5/2} ) decay near a boundary [7]. This transition occurs because the vortex generated by the particle's motion is reflected by the interface, modifying the coupling between the particle and the fluid.

Furthermore, the presence of a boundary universally reduces particle mobility. The diffusion coefficient near a fully wetted, no-slip surface is quantitatively described by a reduced diffusivity ( D{\parallel} ), which is lower than the bulk value ( D0 ) [7]. This confinement effect must be considered when modeling processes in microfluidic devices or on sensor surfaces.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Models of Brownian Motion

| Model | Core Description | Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) | Key Assumptions & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Diffusion (Einstein Model) | Models particle motion as a random walk, connecting diffusion to MSD [4]. | Not defined in the model; implies an instantaneous decay. | Neglects particle and fluid inertia; assumes Markovian (memoryless) process. |

| Langevin Model | Introduces a stochastic force and friction term to account for particle inertia [4]. | Exponential decay. | Includes particle inertia but neglects the fluid's inertia and hydrodynamic memory. |

| Hydrodynamic Model (Bulk) | Incorporates inertia of both the particle and the fluid, capturing transient hydrodynamics [4]. | Long-time tail decay: ( \sim t^{-3/2} ) [7]. | Accounts for fluid vortex generation, providing a more complete physical picture. |

| Hydrodynamic Model (Confined) | Extends the hydrodynamic model to include the effect of a nearby boundary or interface [7] [4]. | Long-time tail decay: ( \sim t^{-5/2} ) [7]. | Models the interaction with a boundary; slip length and local wettability are critical parameters. |

Relating Core Theory to Immobilization and Drift

The theoretical principles of near-boundary Brownian motion have a direct and profound impact on the challenge of surface drift. The persistent, albeit altered, random motion of particles or molecules near a surface is a primary physical driver of drift. This can lead to the gradual desorption of immobilized catalysts or the non-specific binding of analytes in biosensors, degrading signal stability [6] [8]. The ( t^{-5/2} decay of the VACF indicates that while the "memory" of the initial velocity fades faster near an interface, the motion does not cease, underscoring the need for robust immobilization strategies that can withstand this continuous stochastic forcing. Understanding these dynamics allows researchers to select immobilization techniques that counteract these specific forces, for instance, by using covalent bonds to resist the mechanical tug of Brownian motion or by designing surface coatings that minimize non-specific interactions.

Diagram 1: The logical pathway from fundamental Brownian motion to the requirement for immobilization strategies.

Quantitative Data & Experimental Evidence

The following data, drawn from recent studies, quantifies the impact of various factors on drift and the efficacy of mitigation strategies.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Drift Mitigation from Spray Drift Study

| Experimental Factor | Level/Variable | Key Quantitative Result on Drift Reduction | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Size (VMDₚᵣₑₛₑₜ) | 60-80 μm | Drift reduced ~2.5-fold with DRA [5]. | Field study using a ground spraying robot with a jet spraying system and lateral wind [5]. |

| Droplet Size (VMDₚᵣₑₛₑₜ) | 100-120 μm | Drift reduced ~3.5-fold with DRA [5]. | Same as above. |

| Lateral Wind Velocity | 2-4 m/s | DRA solutions were "significantly more effective" [5]. | Same as above. |

| Lateral Wind Velocity | 10 m/s | Difference in effectiveness between DRAs decreased [5]. | Same as above. |

| Drift Reduction Agent (DRA) | DRA1 (Anionic Polymer) | All DRA solutions significantly reduced spray drift compared to water control [5]. | Same as above. |

| Drift Reduction Agent (DRA) | DRA2 (Calcium Dodecylbenzene Sulfonate) | All DRA solutions significantly reduced spray drift compared to water control [5]. | Same as above. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Drift Reduction Agents (DRA) for Surface Immobilization

This protocol is adapted from agricultural spray drift research for application in laboratory settings to test agents that minimize surface drift [5].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Drift Reduction Agents (DRAs): Test agents such as anionic polymer dispersions (e.g., DRA1) or surfactant-based solutions (e.g., DRA2: calcium dodecylbenzene sulfonate) [5].

- Control Solution: Deionized water or standard buffer without DRA.

- Model Particle/Solute: Fluorescent or easily traceable nanoparticles or biomolecules.

- Surface Substrate: Standardized material (e.g., gold sensor chip, silica, polymer) relevant to the end application.

2. Methodology A. Solution Preparation: Prepare DRA solutions at a target concentration (e.g., 0.1% v/v) in the desired solvent [5]. B. Surface Functionalization: Immobilize the model particle/solute onto the substrate surface using a chosen method (e.g., covalent bonding, adsorption). Treat surfaces with DRA solution vs. control. C. Drift Simulation & Measurement: Place the surface in a controlled flow cell or microfluidic channel. Subject it to a simulated stressor (e.g., controlled lateral flow, shear stress, or thermal cycling). D. Quantification: Measure the amount of material desorbed or displaced from the target area over time using an appropriate analytical method (e.g., fluorescence microscopy, SPR, or HPLC). E. Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage reduction in drift for DRA-treated surfaces compared to the control.

Protocol: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for Kinetic Characterization with Regenerable Surfaces

This protocol outlines the use of regenerable immobilization strategies in SPR for accurate small-molecule kinetic profiling, minimizing surface drift and baseline instability [8].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Sensor Chips: CM5 (carboxymethylated dextran) or NTA chips.

- Immobilization Ligands: His-tagged recombinant proteins; Streptavidin or Switchavidin for biotin-capture; Biotinylated ligands.

- Running & Regeneration Buffers: HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% v/v Surfactant P20, pH 7.4); suitable regeneration solution (e.g., 10-350 mM EDTA for NTA, or glycine-HCl at low pH for covalent surfaces).

2. Methodology A. Surface Selection & Preparation: Choose a sensor chip compatible with the chosen immobilization strategy (e.g., NTA for His-tagged proteins). B. Ligand Immobilization: * Dual-His-Tagged Protein: Charge the NTA surface with Ni²⁺, then inject the purified His-tagged protein for direct capture [8]. * His-Tagged Streptavidin: Immobilize His-tagged streptavidin on an NTA chip, then capture a biotinylated ligand [8]. * Switchavidin: Immobilize the mutant streptavidin (Switchavidin) on a CM5 chip via standard amine coupling. Capture the biotinylated ligand. This surface can be fully regenerated with mild biotin solution [8]. C. Kinetic Analysis: Perform binding experiments by injecting a concentration series of the analyte over the functionalized surface. D. Surface Regeneration: After each binding cycle, inject the appropriate regeneration solution to remove bound analyte and, if applicable, the ligand, without damaging the base surface. E. Data Processing: Double-reference the sensorgrams (reference surface & buffer blank) and fit the data to appropriate binding models (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) to determine association (( ka )) and dissociation (( kd )) rate constants, and the equilibrium dissociation constant (( K_D )).

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for a regenerable SPR binding assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Drift Mitigation and Immobilization Studies

| Category | Item | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Drift Reduction Agents | Anionic Polymer Dispersions (e.g., DRA1) | Increase droplet or solution viscosity, modify interfacial properties, and reduce physical drift [5]. |

| Drift Reduction Agents | Surfactant-based DRAs (e.g., DRA2, DRA3) | Alter surface tension and interaction energies at the solid-liquid interface to improve retention [5]. |

| Immobilization Supports | Functionalized Microbeads / Porous Polymers | Provide a high-surface-area solid support for packing into reactors or columns for catalyst or enzyme immobilization [9] [10]. |

| Immobilization Supports | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) & Nanocarriers | Advanced porous materials for high-density, stable enzyme encapsulation or attachment, enhancing stability and reusability [10]. |

| Surface Chemistry | His-Tag / Ni-NTA (Nitrilotriacetic Acid) | Provides a reversible, affinity-based method for immobilizing recombinant proteins on surfaces for assays like SPR [8]. |

| Surface Chemistry | Streptavidin/Biotin | A high-affinity, nearly irreversible binding pair for robust and specific surface immobilization [8]. |

| Surface Chemistry | Switchavidin | A mutant streptavidin allowing for gentle, reversible immobilization of biotinylated ligands, enabling surface regeneration [8]. |

| Surface Chemistry | POEGMA (Poly(oligo (ethylene glycol) methacrylate)) Brushes | Polymer coatings that confer strong antifouling properties, minimizing non-specific binding and associated signal drift in biosensors [6]. |

Signal drift, the undesirable change in a biosensor's baseline signal over time under constant conditions, is a critical challenge that compromises the accuracy and reliability of biosensing platforms [11] [12]. In therapeutic applications, where biosensors are increasingly deployed for real-time monitoring of drugs and biomarkers, drift can lead to incorrect dosage calculations, potentially diminishing therapeutic efficacy and patient safety [13] [14]. This phenomenon is particularly problematic in closed-loop systems, such as feedback-controlled drug delivery, where sensor output directly governs therapy administration [11].

The underlying causes of drift are multifaceted, originating from complex interactions between the biosensor's physical components and its operational environment. For electrochemical biosensors deployed in biological fluids, primary drift mechanisms include electrochemically driven desorption of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) and surface fouling by proteins and blood cells [11]. In field-effect transistor (FET)-based biosensors, signal drift arises from the slow diffusion of ions from the solution into the sensing region, altering gate capacitance and threshold voltage over time [12]. Addressing these sources of drift requires targeted immobilization strategies that enhance interface stability between the biological recognition element and the transducer surface.

Mechanisms of Signal Drift: A Quantitative Analysis

Understanding the specific mechanisms and their quantitative impact on sensor performance is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies. The table below summarizes the primary drift mechanisms, their causes, and measurable effects on biosensor performance.

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of Biosensor Signal Drift

| Drift Mechanism | Primary Cause | Impact on Signal | Temporal Pattern | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Desorption | Redox-driven breakage of gold-thiol bonds on electrode surface [11] | Linear signal decrease over time [11] | Long-term, linear degradation [11] | Rate increases with expanded potential window (>0.0 V anodic, <-0.4 V cathodic) [11] |

| Surface Fouling | Non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, and other biomolecules [11] [12] | Rapid, exponential signal loss [11] | Short-term, exponential decay (e.g., over ~1.5 hours) [11] | Up to 80% signal recovery after urea wash; decreased electron transfer rate [11] |

| Enzymatic Degradation | Nuclease-mediated cleavage of DNA or RNA recognition elements [11] | Irreversible signal loss [11] | Saturation-limited decay [11] | Enzyme-resistant oligonucleotides (2'O-methyl RNA) show similar drift to DNA constructs [11] |

| Ionic Diffusion (in BioFETs) | Slow diffusion of electrolytic ions into the sensing region, altering gate capacitance [12] | Drift in threshold voltage and drain current [11] | Time-based artifact that can obscure true binding signals [12] | Minimized by stable electrical testing, passivation, and polymer brush coatings [12] |

The temporal pattern of signal loss often provides the first clue for identifying the dominant drift mechanism. Research on electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors reveals a characteristic biphasic drift profile when deployed in whole blood at 37°C: an initial exponential decay phase lasting approximately 1.5 hours, followed by a sustained linear decrease [11]. This profile indicates that multiple distinct mechanisms are active simultaneously, with fouling dominating the initial phase and electrochemical desorption governing the long-term linear degradation.

Diagram 1: Biosensor drift mechanisms and their effects on signal accuracy.

Experimental Protocols for Drift Characterization and Mitigation

Protocol: Quantifying Drift Mechanisms in Electrochemical Biosensors

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating signal loss in electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors in biologically relevant conditions [11].

1. Sensor Fabrication:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean gold disk electrodes (e.g., 2 mm diameter) via sequential sonication in deionized water and ethanol for 5 minutes each, followed by electrochemical cleaning in 0.5 M H₂SO₄.

- SAM Formation: Incubate electrodes in a 1 µM solution of thiol-modified DNA or RNA probes (e.g., a 37-base sequence with a methylene blue redox reporter) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Passivation: Rinse electrodes and immerse in a 1 mM solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) for 30 minutes to backfill unoccupied gold sites and form a stable, low-density SAM.

2. Experimental Setup:

- Drift Challenge Medium: Undiluted, fresh whole blood or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control, maintained at 37°C using a temperature-controlled electrochemical cell.

- Electrochemical Interrogation: Use an Autolab or CH Instruments potentiostat. Perform continuous square-wave voltammetry (SWV) scans with parameters: frequency = 60 Hz, amplitude = 25 mV, step potential = 1 mV, potential window tailored to the redox reporter (e.g., -0.4 V to -0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl for methylene blue to minimize desorption).

3. Data Collection:

- Record the peak SWV current for each scan over a minimum of 10 hours.

- For fouling assessment, pause interrogation after 2.5 hours, wash the sensor with 6 M urea for 10 minutes, and resume measurement in PBS to quantify signal recovery.

- To probe electron transfer rates, perform the experiment at multiple SWV frequencies (e.g., 10-300 Hz) and track the frequency of maximum charge transfer over time.

4. Data Analysis:

- Plot normalized signal (I/I₀) versus time and fit the curve to a double-exponential decay model or a linear-exponential hybrid model to deconvolute rapid (fouling) and slow (desorption) drift components.

- A significant signal recovery after urea washing confirms fouling as a major contributor. A strong dependence of drift rate on the applied potential window indicates electrochemical desorption is active.

Protocol: Minimizing Drift in ISFET Biosensors via Surface Treatment

This protocol outlines the surface treatment of Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistor (ISFET) gate oxides to minimize sensing voltage drift error (ΔVdf) [15].

1. Gate Oxide Layer (GOL) Fabrication:

- Deposit an 80 nm SnO₂ thin film on an ITO/glass substrate using RF magnetron sputtering (50 W power, 2×10⁻⁶ Torr base pressure, 18 mTorr work pressure, 5 sccm Ar flow).

- Define a sample reservoir by bonding a plasma-treated PDMS block (with 6 mm holes) to the GOL surface.

2. Stepwise Surface Functionalization:

- Step 1: Hydroxylation. Treat the GOL surface with O₂ plasma (70 W, 1 min, 30 sccm O₂ flow) to create a high density of surface OH groups.

- Step 2: Aminosilanzation. Immediately introduce a 5% (v/v) solution of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) in ethanol to the reservoir. Seal in a dark, humid environment for 1 hour to form a uniform NH₂-terminated monolayer. Rinse with ethanol and cure at 120°C for 15 minutes.

- Step 3: Carboxylation. React the aminated surface with a 5% (w/v) solution of succinic anhydride in dimethylformamide (DMF) overnight at 37°C to generate a COOH-terminated surface.

- Step 4: Antibody Immobilization. Activate the carboxyl groups by applying a fresh mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in water for 30 minutes. Rinse and incubate with the target antibody (e.g., 100 nM PSMA antibody) for 2 hours.

- Step 5: Passivation. Block remaining active esters and non-specific sites by successive treatment with 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 30 minutes and 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 hour.

3. Drift Measurement:

- Connect the functionalized GOL to a semiconductor parameter analyzer (e.g., Keysight 4200-SCS) using a standard CMOS transistor and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Fill the reservoir with 1X PBS (pH 7.4). Measure the transfer characteristic (I-V curve) immediately (t=0) and at 1, 3, 5, and 10 minutes.

- Calculate ΔVdf as the change in threshold voltage or a reference current point over the 5- or 10-minute interval. Compare the ΔVdf of the surface-treated GOL to a bare GOL control.

Diagram 2: Surface treatment workflow for stable ISFET biosensors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of drift-mitigation strategies relies on specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in preparing stable biosensor interfaces.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Drift-Reducing Biosensor Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Benefit | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Alkanethiols (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) | Forms self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on gold; passivates electrode surface to reduce non-specific binding and stabilizes the recognition element tether [11]. | Electrochemical biosensors (EAB sensors) [11]. |

| Polymer Brushes (e.g., POEGMA) | Extends Debye length via Donnan potential; creates a non-fouling, hydrophilic layer that reduces biofouling and signal drift in ionic solutions [12]. | CNT-based BioFETs and immunoassays [12]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., EDC, Sulfo-NHS) | Enables covalent, stable immobilization of biomolecules (antibodies, enzymes) onto COOH-functionalized surfaces, preventing receptor leaching [15]. | ISFET biosensors, general surface functionalization [15]. |

| Surface Modifiers (e.g., APTES) | Silane coupling agent that forms a covalent link between oxide surfaces (SnO₂, SiO₂) and organic layers, providing a stable foundation for further functionalization [15]. | ISFET and FET-based biosensors [15]. |

| Enzyme-Resistant Oligonucleotides (e.g., 2'O-methyl RNA) | Backbone-modified nucleic acids that resist degradation by nucleases, mitigating one potential source of signal decay in complex biological fluids [11]. | Electrochemical aptamer-based (EAB) sensors [11]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Passivates unreacted surface sites after bioreceptor immobilization, drastically reducing non-specific adsorption and the associated drift [15]. | Universal step in immunosensor and aptasensor fabrication [15]. |

Signal drift is not a singular challenge but a confluence of physical, electrochemical, and biological processes that degrade biosensor performance. As this Application Note delineates, effective mitigation requires a mechanistic understanding and targeted immobilization strategies. Key approaches include employing stable SAM chemistry with optimized potential windows, implementing drift-resistant polymer brushes like POEGMA to combat fouling and Debye screening, and utilizing covalent immobilization techniques with robust cross-linkers. The integration of these strategies, guided by the standardized protocols and reagents outlined herein, provides a clear path toward enhancing biosensor accuracy and, consequently, the safety and efficacy of the therapies they monitor and control.

In the pursuit of reliable and robust biosensing and biocatalysis systems, controlling surface drift is paramount. Surface drift, the non-specific and time-dependent change in signal baseline, severely compromises the accuracy and long-term stability of analytical devices, particularly in label-free detection platforms. This application note delineates how three critical experimental factors—surface energy, buffer composition, and environmental conditions—collectively influence surface stability. Framed within a broader thesis on immobilization strategies to reduce surface drift, this document provides detailed protocols and data to guide researchers and drug development professionals in optimizing their experimental systems for enhanced reproducibility and performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues key reagents and materials frequently employed in surface functionalization and immobilization protocols, along with their primary functions.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Immobilization |

|---|---|

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) | Forms a carboxyl-terminated self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on gold surfaces for subsequent covalent coupling [3]. |

| Protein G | Provides oriented immobilization of antibodies by binding to their Fc region, maximizing paratope accessibility [3]. |

| NHS/EDC Chemistry | Activates carboxyl groups on the surface for efficient amine coupling with proteins [3]. |

| Poly(amidoamine) PAMAM Dendrimer | Hyperbranched polymer used to modify surface energy and introduce a high density of functional groups (e.g., amines) for robust enzyme immobilization [16]. |

| Mesoporous Silica SBA-15 | Inorganic carrier with high surface area for enzyme immobilization; often functionalized with groups like N-aminoethyl-γ-aminopropyl trimethoxy [17]. |

| Octyl-Agarose Beads | Hydrophobic support used for the immobilization of lipases via interfacial activation [18]. |

| HEPES Buffer | A zwitterionic buffer used for its stabilizing properties, often showing superior performance compared to phosphate buffers for immobilized enzymes [18] [3]. |

Core Experimental Factors and protocols

Surface Energy and Functionalization

Surface energy directly governs the initial protein attachment, its conformation, and long-term stability on the sensor or catalyst surface. Modifying surface energy to introduce favorable functional groups is a critical first step in building a stable, low-drift interface.

Protocol 3.1.1: Plasma-Dendrimer Treatment of Polyester Fabric This protocol details the surface modification of inert polyester to create a high-energy, amine-rich surface conducive to robust enzyme immobilization [16].

- Surface Cleaning: Clean polyester fabric (e.g., poly(ethylene terephthalate) nonwoven) via Soxhlet extraction with petroleum ether and ethanol to remove spinning oils and contaminants. Confirm cleanliness when the surface tension of rinse water matches distilled water (72 mN/m).

- Plasma Activation:

- Option A (Atmospheric Pressure Plasma): Treat fabric using a Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) system at 60 kJ/m² and 26 kHz. Process at 2 m/min speed.

- Option B (Cold Remote Plasma): Treat fabric with a microwave-generated plasma (800 W, 2.45 GHz) using a gas mixture of N₂ (1230 sccm) and O₂ (89 sccm) at 3.8 mbar.

- Dendrimer Grafting: Incubate the plasma-treated fabric with a solution of poly-(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimer to graft hyperbranched polymers with terminal amine groups onto the activated surface.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Immobilize the target enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) onto the PAMAM-grafted fabric from a solution. The amine groups enable strong covalent attachment.

Protocol 3.1.2: Oriented Antibody Immobilization on Gold SPR Chips This protocol ensures optimal antibody orientation on biosensors, maximizing antigen-binding efficiency and minimizing non-specific surface interactions that contribute to drift [3].

- Surface Cleaning: Clean SPR gold chips with fresh piranha solution (3:1 v/v H₂SO₄:H₂O₂). Caution: Piranha solution is highly corrosive and must be handled with extreme care. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and absolute ethanol.

- SAM Formation: Incubate the clean gold chip in 1 mM 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) in ethanol overnight at room temperature. Rinse with ethanol and water, then dry under a nitrogen stream.

- Surface Activation: Install the chip in the SPR instrument and stabilize with acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5). Inject a fresh mixture of 400 mM EDC and 100 mM NHS for 5 minutes to activate the carboxyl groups.

- Protein G Immobilization: Inject Protein G (25 µg/mL in acetate buffer) over the activated surface for 15 minutes.

- Antibody Capture: Inject the target antibody (40 µg/mL in a suitable buffer) to allow specific, oriented binding via the Fc region to the immobilized Protein G.

The experimental workflow for these surface engineering strategies is summarized in the diagram below.

Buffer Composition

The buffer system is not merely a spectator in immobilization and assay procedures; its ionic composition, pH, and additives profoundly impact the stability and activity of immobilized biomolecules.

Protocol 3.2.1: Evaluating Buffer Effects on Immobilized Lipase Stability This protocol is designed to systematically investigate how different buffers influence the operational stability of enzymes immobilized on hydrophobic supports [18].

- Biocatalyst Preparation: Immobilize lipases (e.g., TLL or CALB) on octyl-agarose beads at different loadings (e.g., 1 mg/g and 15 mg/g).

- Stability Incubation: Incubate the immobilized biocatalysts in a series of 10 mM buffers (e.g., Sodium Phosphate, HEPES, Tris-HCl) at pH 7.0 and a controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C or 45°C).

- Activity Assay: At regular time intervals, withdraw samples and assay residual activity using a specific substrate (e.g., p-nitrophenyl butyrate at pH 5 and 7, or triacetin at pH 5). Monitor the release of p-nitrophenol or the hydrolysis of triacetin.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the residual activity and fit the decay in activity over time to determine half-life or inactivation constant for each buffer condition.

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Buffer on Immobilized Lipase Stability and Activity [18]

| Enzyme (Loading) | Buffer | Relative Stability | Impact on Specific Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CALB (Low Load) | Phosphate | Very Low | Variable, depends on substrate |

| HEPES | High | Variable, depends on substrate | |

| Tris-HCl | High | Variable, depends on substrate | |

| CALB (High Load) | Phosphate | Very Low | Can be almost 2x higher vs. other buffers |

| HEPES | Moderate | Lower than high-load in phosphate | |

| Tris-HCl | High | Lower than high-load in phosphate | |

| TLL (Both Loadings) | Phosphate | Moderately Low | Variable, depends on substrate |

| HEPES / Tris-HCl | High | Variable, depends on substrate |

Environmental Conditions

Factors such as temperature and ionic strength during operation and storage are critical determinants of long-term surface stability, especially for electrochemical biosensors.

Protocol 3.3.1: Capacitive Sensor Performance in High-Ionic-Strength Solutions This protocol outlines the testing of capacitive biosensors under physiologically relevant conditions to evaluate their susceptibility to signal drift [19].

- Sensor Fabrication: Fabricate interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) or other capacitive transducer topographies. Functionalize the electrode surface with an appropriate self-assembled monolayer (SAM) and capture probe (e.g., an antibody or aptamer).

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare running buffers mimicking biological fluids (e.g., 1X PBS, HEPES-buffered saline with 150 mM NaCl) and a low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES) for comparison.

- EIS Measurement: Use Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to measure the double-layer capacitance (C~dl~) in both low and high-ionic-strength buffers. A significant compression of the electrical double layer (reduced Debye length) in high-salt buffers will be observed as a large drop in baseline capacitance.

- Stability & Drift Test: Continuously monitor the capacitive signal over an extended period (e.g., 1-2 hours) in the high-ionic-strength running buffer without introducing the analyte. The slope of the baseline signal over time quantifies the surface drift.

- Non-Specific Binding Test: Challenge the sensor with a complex matrix (e.g., diluted serum or saliva) to assess signal change due to biofouling.

Table 3: Key Environmental Challenges and Mitigation Strategies for Biosensors [19]

| Environmental Factor | Effect on Surface Drift | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| High Ionic Strength | Compresses the electrical double layer (Debye screening), reducing sensitivity and increasing noise. | Engineer the sensor interface using nanoporous electrodes or hydrogels to localize binding within the Debye length. |

| Biofouling | Non-specific adsorption of proteins or cells, causing significant signal drift and reduced specificity. | Implement antifouling surface chemistries (e.g., PEGylation, zwitterionic polymers) on the sensor. |

| Temperature Fluctuation | Causes signal drift due to changes in reaction kinetics and refractive index (in optical sensors). | Use instruments with active temperature control and employ a reference channel for differential measurement. |

The Role of Nanomaterial Properties in Drift Susceptibility and Control

Nanomaterial drift refers to the unintended movement of nanoparticles away from their targeted site of application, leading to potential inefficacy, economic loss, and environmental and health risks. In both biomedical and agricultural applications, controlling this drift is paramount for developing precise and sustainable nanotechnologies. The high mobility and large surface area-to-volume ratio that make nanomaterials so effective also render them particularly susceptible to drift forces, including fluid flow, diffusion, and environmental conditions [20] [21].

The core challenge lies in balancing the inherent mobility of nanomaterials, which is often desirable for delivery, with sufficient retention and targeting to prevent off-site movement. This document frames drift control within the broader thesis that strategic surface immobilization—the engineered attachment of nanomaterials to surfaces or their functionalization with specific molecules—can significantly mitigate drift without compromising functionality. These strategies are universally critical, whether the goal is to retain a drug delivery system at a specific tissue site, maintain an enzymatic biosensor's stability, or ensure pesticides reach only intended crops [22] [20].

Quantitative Analysis of Drift-Influencing Properties

The susceptibility of nanomaterials to drift is governed by a set of quantifiable physicochemical properties. Understanding these parameters is the first step in designing effective drift control strategies. The following tables summarize key properties and their measurable impact.

Table 1: Core Nanomaterial Properties Influencing Drift Susceptibility

| Property | Impact on Drift | Ideal Range for Low Drift | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Smaller particles exhibit greater Brownian motion and are more easily carried by currents. | >100 nm for reduced airborne drift; <200 nm for cellular uptake [20]. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [23] |

| Surface Charge (Zeta Potential) | High negative or positive charge increases stability in suspension, potentially increasing drift range. | Near-neutral charge promotes aggregation and sedimentation [23]. | Zeta Potential Analyzer [23] |

| Hydrophobicity | Hydrophobic particles may aggregate in aqueous environments, reducing drift. | Tunable based on application; can be engineered for specific media [20]. | Contact Angle Measurement |

| Density | Higher density materials settle more quickly from aerosols or suspensions. | Material-dependent; composites can be engineered. | Pycnometry |

Table 2: Impact of Formulation and Environment on Observed Drift

| Factor | Experimental Finding | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Concentration | Nonlinear pharmacokinetics observed; saturation of absorption at high doses indicates limited drifting capacity [24]. | In vivo study of enzalutamide nanoparticles. |

| Animal Species | Differences in drift and absorption profiles linked to variations in gastrointestinal bile salt concentrations [24]. | Comparative study in mice vs. rats. |

| Surface Functionalization | Covalent coupling with APTS ligand resulted in excellent catalytic activity and stable immobilization vs. physical adsorption [23]. | Lipase immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles. |

Immobilization Strategies for Drift Control

Immobilization refers to techniques that restrict the mobility of a bioactive molecule (e.g., a drug, enzyme, or pesticide) by attaching it to a solid support or surface. In the context of drift control, these strategies anchor nanomaterials, preventing their unintended migration.

Classification of Immobilization Techniques

The choice of immobilization strategy is a critical determinant in the success of drift reduction. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting an appropriate immobilization method based on the intended application and desired outcome.

Surface Engineering and Functionalization

Beyond the core immobilization method, engineering the surface of the nanomaterial or its support is a powerful tool for drift control.

- Defect Modulation: Introducing or healing surface defects on 2D nanomaterials like transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) or MXenes can alter surface energy and interaction with the environment, thereby modulating drift propensity [25].

- Ligand Functionalization: Coating nanoparticles with specific polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol) or proteins can provide a steric barrier, reduce nonspecific binding, and enhance stability against aggregation—a common precursor to uncontrolled drifting [20] [26].

- Active Targeting: This advanced strategy involves conjugating nanomaterials with ligands (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) that recognize and bind specifically to receptors on the target cell surface. This actively prevents drift by "locking" the particle in place [20].

Experimental Protocols for Drift Assessment and Control

This section provides detailed methodologies for evaluating drift susceptibility and implementing an effective covalent immobilization strategy.

Protocol: Assessing Drift Susceptibility in Aqueous Environments

Objective: To quantify the suspension stability and sedimentation rate of nanomaterials in a simulated application environment, which is a key indicator of drift potential in liquids.

Materials:

- Nanomaterial suspension: The nano-formulation to be tested.

- Dispersant medium: An appropriate buffer or solvent (e.g., PBS, water).

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer: For quantifying nanomaterial concentration.

- Cuvettes: Disposable or quartz, compatible with the spectrophotometer.

- Centrifuge: For accelerated stability testing.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a standardized concentration of the nanomaterial suspension in the dispersant medium. Sonicate the sample to ensure homogeneity.

- Baseline Measurement: Using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, measure the absorbance of the well-mixed suspension at a characteristic wavelength (e.g., 410 nm was used in lipase activity assays [23]). Record this as A₀.

- Static Sedimentation: Allow the suspension to stand undisturbed under controlled conditions (temperature, humidity). At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours), carefully sample from a fixed depth and measure the absorbance (Aₜ).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of material remaining in suspension at each time point: % Suspension = (Aₜ / A₀) × 100. Plot % Suspension versus time to generate a sedimentation profile. A slower decay curve indicates lower drift susceptibility in the liquid phase.

Protocol: Covalent Immobilization onto Magnetic Nanoparticles

Objective: To stably immobilize a bioactive molecule (e.g., an enzyme) onto magnetic nanoparticles via covalent bonding, facilitating easy magnetic recovery and minimizing drift and leakage [23].

Materials:

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Covalent Immobilization

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Covalent Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Core support material; enables magnetic recovery. | Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles synthesized by coprecipitation [23]. |

| Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTS) | Silane coupling agent; introduces primary amine (-NH₂) groups onto MNP surface. | Allows for subsequent covalent attachment [23]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinker; reacts with amine groups on the support and the enzyme to form a stable Schiff base. | A homobifunctional crosslinker [23]. |

| Target Enzyme | The bioactive molecule to be immobilized. | e.g., Lipase from Rhizomucor miehei [23]. |

| p-Nitrophenyl Palmitate (p-NPP) | Substrate for quantifying enzymatic activity of immobilized lipase. | Hydrolysis is measured at 410 nm [23]. |

Procedure:

- Support Functionalization:

- Synthesize magnetic Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles via chemical co-precipitation of Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ salts in a basic ammonia solution [23].

- Wash the MNPs and resuspend them in an ethanolic solution of APTS (e.g., 0.043 M). Stir the mixture for 40 hours at 28°C to form amine-functionalized MNPs (MNPs-NH₂).

- Separate the MNPs-NH₂ magnetically and wash thoroughly with ethanol and water to remove excess silane.

Enzyme Coupling:

- Activate the MNPs-NH₂ by incubating with a glutaraldehyde solution (e.g., 2.5% v/v) in a suitable buffer for 1 hour.

- Wash the activated support to remove unreacted glutaraldehyde.

- Incubate the activated MNPs with the target enzyme solution (e.g., 30 mg/mL in PBS, pH 7.2) under gentle agitation for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Recover the immobilized enzyme (e.g., MNP-Lipase) using a magnet and wash extensively with buffer to remove physically adsorbed enzyme.

Validation and Activity Assay:

- Confirm immobilization by quantifying the protein concentration in the initial and final wash supernatants using UV-Vis spectrophotometry (e.g., absorbance at 280 nm) [23].

- Assess the success of immobilization by measuring the catalytic activity of the conjugated lipase. Incubate the MNP-Lipase with p-NPP substrate and measure the release of p-nitrophenol at 410 nm over time [23].

Controlling nanomaterial drift is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor but a deliberate design process. The data and protocols presented herein establish that drift susceptibility is directly governed by quantifiable nanomaterial properties, including size, surface charge, and functionalization. As demonstrated, strategic immobilization—particularly through stable covalent binding and advanced surface engineering—provides a robust methodological framework to anchor nanomaterials, enhance their functional stability, and mitigate unintended drift. By integrating these principles and experimental approaches, researchers and drug development professionals can advance the design of more precise, efficient, and environmentally responsible nanotechnologies for biomedical and agricultural applications.

Proven Immobilization Techniques: Practical Strategies for Drift Reduction

Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of alkanethiolates on gold represent one of the most well-characterized and robust platforms for covalent immobilization in biomedical research. These monolayers form through the spontaneous chemisorption of thiol-containing molecules onto gold surfaces, creating highly ordered, chemically well-defined substrates [27] [28]. The process relies on the strong affinity between sulfur atoms and gold, where thiol groups form coordination bonds with the gold surface, followed by the organization of alkyl chains through van der Waals interactions, resulting in a stable, closely packed monolayer [28]. This system has emerged as a powerful tool for studying cell-biomolecule interactions, fabricating biosensors, and developing diagnostic assays because it provides precise control over surface chemistry and biomolecule presentation [27] [28]. Within the context of immobilization strategies to reduce surface drift research, SAMs offer exceptional stability through covalent bonding, significantly minimizing the desorption and lateral movement (drift) of immobilized molecules that plagues non-specific adsorption methods, thereby enhancing experimental reproducibility and reliability.

The Gold-Thiol Interface: Bonding Nature and Stability

The chemistry at the gold-thiol (Au-S) interface is complex and dynamic, with the nature and strength of the bond varying significantly under different experimental conditions [29]. The Au-S bond is best described as a resonance hybrid with varying proportions of two extreme forms: a dispersive-force-dominating Au(0)-thiyl character and a covalent/ionic-force-dominating Au(I)-thiolate character [29]. The prevailing character depends on environmental factors such as pH, surface properties, and interaction time [30].

Crucially, the bond formed between a deprotonated thiyl radical (RS) and gold—a stronger chemisorption bond (Au-SR)—is significantly more stable than the weaker coordinate (dative) bond formed with a protonated thiol group (RSH), denoted as Au-SRR' [29]. Single-molecule studies have demonstrated that the Au-SR bond is so strong that mechanical breaking often results in the extraction of a gold atom from the surface, breaking Au-Au bonds instead of the Au-S bond itself [30] [29]. This exceptional stability is the fundamental basis for using thiol-based SAMs to mitigate surface drift, as it firmly anchors molecules to the substrate.

Table 1: Factors Influencing the Strength and Stability of Thiol-Gold Contacts

| Factor | Effect on Bond Strength/Stability | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Surface Oxidation State | Oxidized gold surfaces greatly enhance contact stability compared to reduced surfaces. | Rupture force of 1.09 ± 0.39 nN on oxidized gold vs. 0.62 ± 0.18 nN on reduced gold [30]. |

| Environmental pH | Higher pH favors deprotonation, shifting the bond from a coordinate bond to a more stable covalent bond. | A shift in binding modes observed with increasing pH [30]. |

| Interaction Time | Bond stability can increase with interaction time, further shifting towards covalent character. | Increased rupture force observed with longer interaction times [30]. |

| Molecular Environment | Isolated thiol-gold contacts are more stable than contacts within densely packed SAMs. | Single-molecule experiments show higher stability for isolated contacts [30]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Thiol-Gold Bond Strength

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) has been instrumental in quantifying the strength of individual thiol-gold contacts. These experiments measure the rupture force required to break a single bond. The values observed typically correspond to the breaking of Au-Au bonds near the binding sites, as the Au-S bond itself is stronger than the metallic bonds in the gold substrate [30] [29].

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Rupture Forces of Thiol-Gold Contacts

| Experimental Condition | Measured Rupture Force (nN) | Proposed Rupture Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Standard AFM-SMFS [30] | 1.4 ± 0.3 | Rupture of Au-Au bond or extraction of gold atoms. |

| Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics [30] | ~1.2 | Breakage of a Au-Au bond. |

| Mechanically Controlled Break-Junction [30] | ~1.5 | Breaking of molecular junctions at Au-Au bonds. |

| AFM on Oxidized Gold (pH 8.0) [30] | 1.09 ± 0.39 | Cleavage of single Au-Au bonds. |

| AFM on Reduced Gold (pH 8.0) [30] | 0.62 ± 0.18 | Cleavage of single Au-Au bonds. |

Experimental Protocol: Forming a Carboxyl-Terminated SAM for Protein Immobilization

This protocol details the creation of a well-ordered SAM terminated with carboxyl groups, which can be activated for covalent immobilization of proteins (e.g., antibodies) via their primary amines, thereby minimizing surface drift.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SAM Formation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Gold substrate (e.g., on glass/silicon) | Provides the surface for thiol chemisorption. |

| 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (COOH-terminated alkanethiol) | Forms the SAM, presenting a carboxyl group for subsequent protein coupling. |

| Absolute Ethanol (high purity) | Serves as the solvent for thiol solution preparation. |

| 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) | Activates carboxyl groups to form reactive O-acylisourea intermediates. |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) | Stabilizes the activated ester, preventing hydrolysis and improving coupling efficiency. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) | Provides a biocompatible buffer for protein handling and coupling reactions. |

| Target Protein (e.g., antibody) | The molecule to be covalently immobilized. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean the gold substrate thoroughly using an oxygen plasma cleaner or by immersion in a piranha solution (Caution: Piranha solution is extremely corrosive and must be handled with extreme care), followed by rinsing with copious amounts of pure water and ethanol. This step removes organic contaminants and creates a hydrophilic, oxidized gold surface, which has been shown to enhance thiol-gold contact stability [30].

- SAM Formation: Prepare a 1 mM solution of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid in absolute ethanol. Immerse the clean, dry gold substrate into this solution and incubate for 12-18 hours at room temperature. This allows for the spontaneous formation of a dense, well-ordered monolayer.

- SAM Rinsing and Drying: After incubation, remove the substrate from the thiol solution and rinse it thoroughly with pure ethanol to remove any physically adsorbed molecules. Dry the substrate under a stream of inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon).

- Carboxyl Group Activation: Prepare a fresh activation solution containing 0.2 M EDC and 0.05 M NHS in deionized water or a buffer like MES (pH 5-6). Incubate the SAM-coated substrate in this solution for 30-60 minutes to convert the terminal carboxyl groups to amine-reactive NHS esters [27].

- Protein Immobilization: Rinse the activated substrate briefly with a coupling buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4). Apply a solution of the target protein (typically at a concentration of 10-100 µg/mL in PBS) to the surface and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. During this step, primary amines (lysine residues) on the protein react with the NHS esters, forming stable amide bonds.

- Quenching and Washing: After coupling, rinse the substrate with PBS to remove unbound protein. To quench any remaining activated esters, incubate the surface with a 1 M ethanolamine solution (pH 8.5) for 1 hour. Perform a final series of washes with PBS before using the functionalized surface in subsequent assays.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol:

Application Note: Covalent vs. Physical Adsorption in ELISA

The critical importance of covalent immobilization for reducing surface drift is clearly demonstrated in the development of paper-based ELISAs (P-ELISA). A 2024 study directly compared immobilizing capture antibodies (human IgG) on paper via covalent bonding versus physical adsorption [31].

- Covalent Methods: Two covalent strategies were employed: (1) oxidizing paper with NaIO₄ to create aldehyde groups, and (2) treating paper with APTS-glutaraldehyde to similarly create aldehyde groups for Schiff base formation with antibody amines.

- Performance Outcome: The APTS-glutaraldehyde covalent method was superior to physical adsorption in both sensitivity and reproducibility. The covalently bound antibodies resisted desorption during repeated washing steps, a common source of surface drift and signal instability in immunoassays [31]. This highlights how covalent immobilization directly enhances assay performance by locking biomolecules in place.

Visualization of the Thiol-Gold Binding Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the chemical process of SAM formation and the subsequent covalent protein immobilization, which is key to understanding the stability of the system.

Surface functionalization of nanomaterials has emerged as a pivotal strategy for enhancing the stability and performance of nanoparticles (NPs) in biomedical applications. Within the broader context of immobilization strategies to reduce surface drift research, controlling the nano-bio interface is essential for improving colloidal stability, ensuring target specificity, and minimizing non-specific interactions that contribute to signal drift and performance degradation. Surface functionalization significantly impacts the success of various applications by enabling selective and precise targeting, which is crucial for reliable biosensing, drug delivery, and diagnostic systems [32]. The functionalization of nanostructures provides partial control over the orientation of ligands on the substrate surface, which directly influences interfacial behavior and drift phenomena [32]. This document outlines detailed protocols and application notes for surface functionalization techniques that enhance stability, with particular emphasis on their role in mitigating surface drift—a critical consideration for researchers and drug development professionals designing robust nanomaterial-based systems.

Background and Significance

Surface functionalization encompasses various strategies for modifying nanomaterial surfaces to impart specific chemical functionalities that enhance stability and reduce undesirable drift. These modifications are crucial for applications requiring precise interfacial control, as they affect intermolecular forces at the liquid-solid interface [33]. For nanomaterials used in biological environments, surface drift can result from uncontrolled protein adsorption, aggregation, or non-specific binding, ultimately compromising performance reliability.

The fundamental mechanisms governing nanoparticle-biomolecule interactions include electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic effects [34]. Electrostatic forces, particularly susceptible to environmental conditions like pH and ionic strength, often dominate adsorption behavior and can be harnessed to improve stability [34]. Understanding these interactions enables researchers to design functionalization strategies that create more stable interfaces with reduced drift, which is essential for applications such as point-of-care devices and environmental monitoring where consistent performance is critical [32].

Functionalization Approaches and Mechanisms

Chemical Functionalization Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Functionalization Methods for Enhanced Stability

| Method | Mechanism | Key Reagents | Stability Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silanization | Covalent attachment of organosilanes to surface hydroxyl groups | APTES, carboxyethylsilanetriol | High stability in aqueous media, introduces reactive handles for further conjugation | Requires specific surface chemistry, may introduce impurities [35] |

| Click Chemistry | Bioorthogonal cycloaddition reactions | Azides, alkynes, catalysts | High specificity, minimal byproducts, suitable for complex ligand architectures | May require pre-functionalization, catalyst removal needed [32] |

| Active Ester Chemistry | Acylation of amine-containing molecules | NHS esters, EDC, sulfo-NHS | Rapid conjugation under mild conditions, high efficiency for biomolecules | Hydrolysis in aqueous solutions limits working time [32] |

| Maleimide Chemistry | Thiol-ene coupling to cysteine residues | Maleimide-functionalized linkers | Highly specific for thiol groups, stable amide bond formation | Potential hydrolysis over time, may require reducing environments [32] |

| Aldehyde Linkers | Schiffs base formation with primary amines | Glutaraldehyde, PEG-dialdehyde | Direct conjugation to amine-rich surfaces, simple implementation | Reversible nature may contribute to drift, requires stabilization [32] |

Polymer-Based Stabilization Approaches

Polymer wrapping and coating significantly alter surface electrostatic potential and provide steric stabilization against aggregation. Cationic polymers like polyethyleneimine (PEI) and chitosan create positively charged surfaces that enhance adsorption of negatively charged biomolecules while improving colloidal stability [34]. Anionic polymers such as poly(acrylic acid) and poly(styrene sulfonate) generate negative surface charges suitable for binding cationic therapeutic agents [34]. The PEGylation technique, using polyethylene glycol, creates a hydrophilic protective layer that reduces protein adsorption and opsonization, thereby decreasing surface drift and improving circulation time [36] [37].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Functionalized Nanoparticles

| Functionalization Method | Hydrodynamic Size Increase | Zeta Potential Range | Colloidal Stability | Protein Corona Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEGylation | 5-15 nm | -20 to -30 mV | Excellent (>4 weeks) | High (70-80% reduction) |

| Silanization (APTES) | 2-8 nm | +25 to +40 mV | Good (1-2 weeks) | Moderate (40-50% reduction) |

| Chitosan Coating | 10-20 nm | +30 to +50 mV | Good (2-3 weeks) | Moderate (30-40% reduction) |

| PEI Coating | 8-15 nm | +35 to +55 mV | Fair (3-7 days) | Low (20-30% reduction) |

| PAA Coating | 5-12 nm | -30 to -50 mV | Excellent (>4 weeks) | High (60-70% reduction) |

Experimental Protocols

Single-Step Surface Functionalization of Polymeric Nanoparticles

This protocol describes a versatile, single-step surface functionalization technique for polymeric nanoparticles that enables simultaneous incorporation of multiple targeting ligands, reducing processing time and potential sources of drift through simplified fabrication [37].

Materials:

- Polylactide-polyethylene glycol (PLA-PEG) diblock copolymer

- PLA-PEG-ligand conjugate (e.g., PLA-PEG-biotin or PLA-PEG-folate)

- Organic solvent (ethyl acetate or dichloromethane)

- Aqueous phase (surfactant solution, e.g., polyvinyl alcohol)

- Drug compound (e.g., paclitaxel for therapeutic applications)

- Purification equipment (dialysis membrane or tangential flow filtration)

Procedure:

- Organic Phase Preparation: Dissolve 100 mg PLA-PEG copolymer and 50 mg PLA-PEG-ligand conjugate in 5 mL organic solvent. Add therapeutic agent if producing drug-loaded nanoparticles (e.g., 10 mg paclitaxel).

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Prepare 20 mL of 1-2% polyvinyl alcohol solution in deionized water as the continuous phase.

- Emulsification: Add the organic phase to the aqueous phase while probe-sonicating at 80-100 W for 2-3 minutes in an ice bath to form a stable oil-in-water emulsion.

- Organic Solvent Removal: Stir the emulsion overnight at room temperature to allow complete solvent evaporation, or use reduced pressure for faster removal.

- Purification: Centrifuge the nanoparticle suspension at 15,000 × g for 30 minutes, then resuspend in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Alternatively, purify by dialysis against deionized water for 4-6 hours.

- Characterization: Determine particle size by dynamic light scattering, surface charge by zeta potential measurement, and ligand incorporation by surface plasmon resonance or NMR.

Silanization-Based Surface Functionalization for Inorganic Nanoparticles

This protocol details the silanization of inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., iron oxide, silica) to introduce amine functional groups for improved stability and subsequent biomolecule conjugation [35].

Materials:

- Inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., iron oxide, 10-20 nm diameter)

- 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES)

- Anhydrous toluene or ethanol

- Inert atmosphere setup (argon or nitrogen gas)

- Rotary evaporator or centrifugal concentrator

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Activation: Dry 50 mg of nanoparticles under vacuum at 80°C for 2 hours to remove adsorbed water and activate surface hydroxyl groups.

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Disperse activated nanoparticles in 50 mL anhydrous toluene under inert atmosphere. Add 500 μL APTES dropwise while stirring.

- Silanization Reaction: Reflux the mixture at 110°C for 12-16 hours with continuous stirring under moisture-free conditions.

- Purification: Recover functionalized nanoparticles by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 minutes. Wash sequentially with toluene, acetone, and ethanol to remove unreacted silane.

- Drying: Dry the amine-functionalized nanoparticles under vacuum or resuspend in appropriate buffer for immediate use.

- Characterization: Confirm functionalization by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) for amine group detection (peaks at 1650 cm⁻¹ and 1550 cm⁻¹) and zeta potential shift toward positive values.

Electrostatic Adsorption Optimization Protocol

This protocol outlines steps to optimize electrostatic adsorption of biomolecules onto functionalized nanoparticles, with particular attention to parameters affecting stability and drift reduction [34].

Materials:

- Functionalized nanoparticles (amine- or carboxyl-terminated)

- Target biomolecule (DNA, protein, or peptide)

- Buffer solutions at varying pH (phosphate, acetate, carbonate)

- Salt solutions (NaCl, KCl) for ionic strength adjustment

- Dynamic light scattering instrument

- Zeta potential analyzer

Procedure:

- Surface Charge Characterization: Measure the zeta potential of functionalized nanoparticles (0.1 mg/mL) in different pH buffers (pH 3-9) to determine the isoelectric point.

- Biomolecule Charge Assessment: Determine the isoelectric point (pI) of the target biomolecule using electrophoresis or zeta potential analysis.

- Adsorption Condition Optimization: Incubate nanoparticles with biomolecule at varying:

- pH values (select 1-2 units above or below pI for opposite charges)

- Ionic strength (0-150 mM NaCl)

- Nanoparticle:biomolecule ratios (1:1 to 1:10 w/w)

- Incubation: Allow adsorption to proceed for 30-60 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Purification: Remove unbound biomolecules by centrifugation, dialysis, or size exclusion chromatography.

- Characterization: Determine adsorption efficiency by UV-Vis spectroscopy (measuring supernatant depletion), confirm complex stability by dynamic light scattering, and assess functionality through cell uptake studies or activity assays.

Visualization of Functionalization Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Surface Functionalization and Stability Enhancement

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Surface Stabilization |

|---|---|---|

| Coupling Agents | EDC, NHS, sulfo-NHS | Activate carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with amine-containing ligands [32] |

| Silane Coupling Agents | APTES, MPTMS, CPTES | Introduce functional groups (-NH₂, -SH) for covalent attachment to hydroxylated surfaces [35] |

| Polymeric Stabilizers | PEG, PLA-PEG, chitosan | Provide steric hindrance against aggregation, reduce protein adsorption [37] |

| Surface Ligands | Biotin, folic acid, lactobionic acid | Enable specific targeting, reduce non-specific interactions [35] |

| Charge Modifiers | PEI, PAA, PSS | Alter surface potential to control electrostatic interactions [34] |

| Biological Ligands | Antibodies, peptides, aptamers | Provide high-specificity recognition, minimize off-target binding [32] |

Surface functionalization of nanomaterials represents a critical approach for enhancing stability and reducing surface drift in biomedical applications. The protocols and data presented herein provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these strategies, with particular relevance to immobilization strategies in drift-sensitive systems. As the field advances, the development of novel functionalization techniques with enhanced precision and reduced environmental impact will continue to drive innovation in nanotechnology applications [38]. The integration of multiple functionalization strategies appears particularly promising for addressing the complex challenge of surface drift while maintaining biological functionality.

Surface immobilization of biomolecules is a critical process in numerous biotechnological and diagnostic applications, ranging from biosensor development to targeted drug delivery systems. A fundamental challenge in these applications is surface drift—the gradual loss of functional integrity due to unstable molecular anchoring. Cross-linking strategies, particularly those employing bifunctional agents like EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide), provide powerful solutions to this problem by creating stable, covalent linkages between surface materials and biological ligands. The EDC/NHS chemistry enables efficient amide bond formation between carboxyl and amine groups without incorporating the cross-linker into the final bond, making it particularly valuable for biomedical applications where biocompatibility is essential [39]. This protocol details advanced implementation of EDC/NHS and complementary strategies to achieve robust surface immobilization while minimizing drift, a crucial consideration for the reliability of biosensors, diagnostic devices, and therapeutic platforms.

Fundamental Mechanisms of EDC-NHS Chemistry

Reaction Pathways and Molecular Interactions

The EDC/NHS cross-linking mechanism involves a precise sequence of reactions that transform carboxyl groups into amine-reactive intermediates. EDC first activates carboxyl groups to form an unstable, reactive O-acylisourea intermediate. This intermediate can then follow two primary pathways: it may directly react with primary amines to form amide bonds, or it can be stabilized through reaction with NHS to create a more stable NHS-ester. The NHS-ester subsequently reacts efficiently with amine groups to yield stable amide linkages [40] [39]. This dual-reagent system significantly improves conjugation efficiency compared to EDC alone, as the NHS-ester is less susceptible to hydrolysis in aqueous environments, thereby extending the functional window for conjugation.

The reaction kinetics and final products can be influenced by steric factors and the molecular environment. Research on polymethacrylic acid (PMAA) demonstrates that polymers with closely spaced carboxylic acid groups may predominantly form anhydrides due to the Thorpe-Ingold effect, where gem-dialkyl groups compress acid side chains, favoring intramolecular reactions. In contrast, isolated acid groups are more likely to form NHS-esters [41]. Understanding these subtleties is crucial for optimizing immobilization strategies for different surface chemistries and biomolecules.

Quantitative Comparison of Bifunctional Cross-linking Strategies

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Bifunctional Cross-linking Approaches

| Cross-linking Strategy | Reactive Groups | Binding Mechanism | Optimal Applications | Impact on Surface Drift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Carboxyl to Primary Amine | Zero-length crosslinker (not incorporated) | Protein immobilization, collagen scaffolds, nanoparticle conjugation | Minimal drift due to covalent amide bonds; stability enhanced by NHS |

| UV-NBS Method | Indole ring to Antibody variable regions | Site-specific, moderate binding | Antibody and Fab fragment conjugation to nanocarriers | Superior orientation control reduces denaturation-related drift |

| BS³ (Bis[sulfosuccinimidyl] suberate) | Amine to Amine | NHS-ester mediated, 11.4 Å spacer | Protein complex structural studies, interactome analysis | Stable protein network reduces dissociation; maintains structural integrity |

| PDDA Cross-linking | Quaternary ammonium complexes | Electrostatic immobilization | Cationic surface modification, electrochemical applications | Reduces reagent leaching; maintains functional surface density |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Immobilization

Standard EDC/NHS Conjugation Protocol for Carboxylated Surfaces

This protocol describes the optimized immobilization of antibodies onto carboxyl-terminated self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) for biosensor applications, with specific modifications to enhance surface density and reduce drift [40] [3].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Carboxylated surface (e.g., 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid SAM on gold chip)

- EDC hydrochloride (400 mM stock solution in water)

- NHS (100 mM stock solution in water)

- Antibody solution (20-100 μg/mL in acetate buffer, pH 4.5)

- Acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5)

- Regeneration buffer (15 mM NaOH with 0.2% SDS)

- Ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.5)

- Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) instrument for quantification

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Surface Preparation: Clean the gold sensor surface with piranha solution (3:1 v/v H₂SO₄:H₂O₂; caution: highly corrosive), then rinse thoroughly with deionized water. Immerse the cleaned surface in 1 mM 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA) ethanol solution overnight to form a carboxyl-terminated SAM. Rinse extensively with ethanol and deionized water, then dry under nitrogen stream [3].

Surface Activation: Insert the functionalized chip into the biosensor instrument. Stabilize the surface by flowing acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5) for 45 minutes. Activate the carboxyl groups by injecting a freshly prepared mixture of 400 mM EDC and 100 mM NHS for 300 seconds at a flow rate of 10 μL/min [40] [3].