Accurate Bulk Response Correction in SPR: A Comprehensive Guide for Reliable Biomolecular Interaction Data

This article provides a complete guide to bulk response correction in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), a critical challenge that complicates data interpretation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Accurate Bulk Response Correction in SPR: A Comprehensive Guide for Reliable Biomolecular Interaction Data

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to bulk response correction in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), a critical challenge that complicates data interpretation for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational theory of the bulk effect, details a novel reference-free correction method, offers practical troubleshooting for common artifacts, and establishes robust validation protocols. By synthesizing current research and best practices, this guide empowers scientists to improve the accuracy of affinity and kinetic measurements, revealing subtle interactions often obscured by bulk signals.

Understanding the SPR Bulk Response: From Fundamental Theory to Impact on Data Quality

What is the Bulk Response? Defining the Signal from Molecules in Solution

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a well-established, label-free technique for real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions [1] [2]. A significant complicating factor in SPR sensing is the "bulk response" (or bulk effect), an inconvenient signal contribution from molecules in solution that do not actually bind to the sensor surface [1] [3] [4]. This effect occurs because the evanescent field used for detection extends hundreds of nanometers from the surface—far beyond the thickness of typical analytes like proteins (2-10 nm) [1]. Consequently, when molecules are injected at high concentrations (necessary for probing weak interactions), or when complex samples with differing refractive indices are introduced, a large but false sensor signal is generated from the solution itself, obscuring the true binding signal [1] [3]. This bulk response is one major reason why conclusions in many SPR publications may be questionable [1]. Properly identifying and correcting for this effect is therefore critical for obtaining accurate interaction data, particularly for weak affinities or in drug development contexts [1] [5].

The Physical Basis of the Bulk Response

Origin in SPR Physics

The bulk response arises from the fundamental operating principle of SPR. SPR instruments detect changes in the refractive index (RI) near a sensor surface [6] [5]. The evanescent field probes a volume that encompasses not only the surface-bound layer but also a significant portion of the adjacent solution [1]. Any change in the composition of the bulk solution during an injection—such as the introduction of proteins, salts, or solvents like DMSO—will alter its bulk refractive index [3] [7]. Since SPR cannot intrinsically distinguish between a mass change on the surface and a RI change in the solution, both contribute to the measured signal [5]. This is why a large, rapid response shift is observed at the start and end of an injection, even in the absence of any specific binding [7].

Consequences for Data Interpretation

The bulk effect complicates data interpretation by inflating the apparent binding response, which can lead to overestimation of binding affinity or mask weak interactions [1]. In sensorgrams, it typically manifests as a characteristic 'square' shape due to large, rapid response changes at the injection start and end points [7]. The shifts may be positive or negative, depending on the direction of the RI difference between the analyte solution and the running buffer [7]. While bulk shift does not change the inherent kinetics of the binding partners, it makes differentiating small binding-induced responses and interactions with rapid kinetics from a high refractive index background particularly challenging [7].

Table 1: Common Sources of Bulk Response and Their Causes

| Source | Description | Impact on SPR Signal |

|---|---|---|

| High Analyte Concentration [1] | Necessary for probing weak interactions, but increases solute concentration in bulk solution. | Increased signal from molecules in solution, not surface binding. |

| Buffer Mismatch [3] | Running buffer and analyte buffer are not perfectly matched in composition. | "Jumps" in the sensorgram at injection start/end. |

| DMSO/Glycerol [3] | Analyte stored in or dissolved in solvents with high refractive index (e.g., DMSO, glycerol). | Large bulk shifts that can obscure the binding signal. |

| Complex Samples [1] | Samples like serum or cell lysates have a different overall refractive index than running buffer. | Large false signal due to changing bulk RI. |

A Novel Method for Accurate Bulk Response Correction

Limitations of Traditional Approaches

The conventional approach to mitigating bulk response uses a separate reference channel on the sensor chip, which is intended to measure the bulk effect for subtraction from the active channel [1]. However, this method requires that the reference surface perfectly repels all injected molecules and has an identical coating thickness to the active channel, conditions that are difficult to achieve in practice [1]. Even minor variations can introduce significant errors. Furthermore, the bulk response correction methods recently implemented in some commercial instruments (e.g., PureKinetics by BioNavis) have been shown to not be generally accurate, as evidenced by remaining bulk responses during injections in published data [1].

A Reference-Free Physical Model

A recent study presents a new method for direct bulk response correction that does not require a reference channel or separate surface region [1] [4]. This approach is based on a physical model that uses the total internal reflection (TIR) angle response as an independent measure of the bulk refractive index [1]. The method acknowledges that the thickness of the surface layer containing receptors must be considered for an accurate correction. It provides a simple analytical model to account for the bulk contribution using the TIR angle as the only input, thereby revealing binding signals that would otherwise be hidden by the bulk effect [1].

Experimental Validation with PEG-Lysozyme Interaction

The utility of this new correction method was demonstrated by revealing a weak interaction between poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) brushes and the protein lysozyme under physiological conditions [1] [4]. Before correction, this interaction was obscured by the bulk response. After applying the model, the equilibrium affinity was accurately determined to be KD = 200 µM, with the interaction being relatively short-lived (1/koff < 30 s) [1]. This application not only provided new insights into a biologically relevant interaction but also served as an excellent model system for validating the correction method [1].

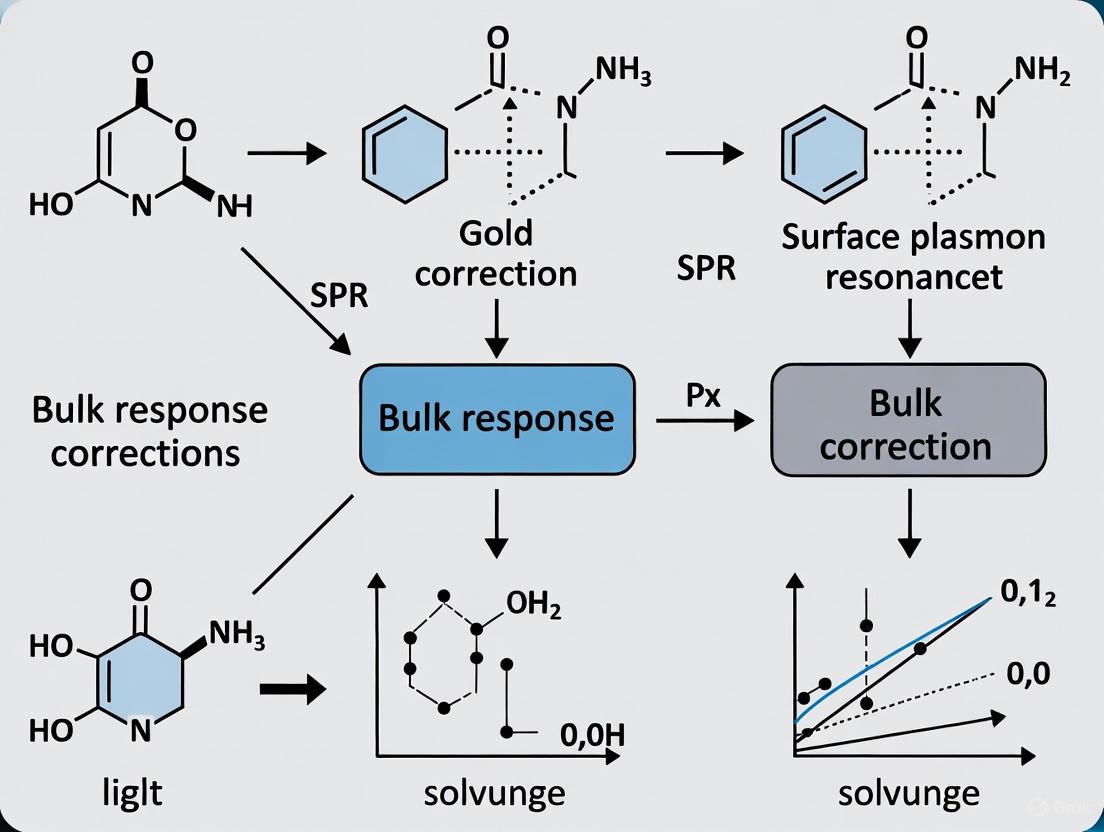

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for bulk response correction and validation using the PEG-lysozyme model system.

Experimental Protocol for Bulk Response Correction

Sensor Chip Preparation and Functionalization

This protocol is adapted from the lysozyme-PEG interaction study that successfully implemented the novel bulk correction method [1].

Materials:

- SPR chips with ~2 nm Cr and 50 nm Au (optimal for a narrow, deep SPR minimum) [1].

- Thiol-terminated PEG (MW 20 kg/mol) for creating a well-hydrated polymer brush layer [1].

- Proteins: Lysozyme (the analyte) and Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, a non-interacting control) [1].

- Buffers: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for experiments; Na₂SO₄ solution (0.9 M) for PEG grafting [1].

- Cleaning solutions: RCA1 and RCA2 cleaning solutions, ethanol, oxygen plasma [1].

Procedure:

- Clean glass substrates using RCA2 solution (1:1:5 conc. HCl:H₂O₂(30%):H₂O at 80°C) and 50 W O₂ plasma at 250 mTorr [1].

- Deposit metal layers via electron beam physical vapor deposition: first ~2 nm Cr, then 50 nm Au [1].

- Clean SPR chips before experiments with RCA1 (5:1:1 MQ water:H₂O₂:NH₄OH at 75°C for 20 min), incubate in 99.8% EtOH for 10 min, and dry with N₂ [1].

- Graft PEG brushes by immersing the sensor in 0.12 g/L thiol-terminated PEG in filtered 0.9 M Na₂SO₄ for 2 hours with gentle stirring (50 rpm) [1].

- Rinse and hydrate the functionalized sensor thoroughly with ultrapure water, dry with N₂, and leave immersed in water overnight on a Teflon stand [1].

SPR Measurement with Bulk Correction

Instrument Setup:

- Use an SPR Navi 220A instrument or equivalent with dual-flow channels and multiple wavelengths [1].

- Set temperature to 25°C and use a wavelength of 670 nm [1].

- Set flow rate to 20 µL/min for all protein injections [1].

Data Acquisition:

- Perform dry thickness scans in air to determine the dry PEG thickness using Fresnel model fits to SPR spectra [1].

- Determine hydrated brush height by introducing BSA (a non-interacting protein) into the liquid bulk and using Fresnel models [1].

- Run lysozyme injections in PBS buffer across a range of concentrations (e.g., from <0.1 g/L upwards). Repeat measurements for all but the lowest concentrations to ensure reproducibility [1].

- Record both SPR angle and TIR angle simultaneously during all injections. The TIR signal serves as the independent measure of the bulk refractive index [1].

Data Processing and Bulk Correction:

- Apply linear baseline correction if instrumental drift is consistent throughout the experiment (typically <10⁻⁴ °/min) [1].

- Correct for injection artifacts by subtracting a very small shift (~0.002°) observed in both SPR and TIR angles during buffer injections from all corresponding protein injection signals [1].

- Calculate the bulk-corrected SPR signal using the physical model that incorporates the effective field decay length and the TIR angle response as detailed in the source literature [1]. For well-hydrated films like PEG brushes, an effective field decay length can quantify the SPR response accurately.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Bulk Response Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Gold SPR Chips (Cr/Au) | Sensor substrate for SPR signal generation and ligand immobilization. |

| Thiol-terminated PEG | Forms a hydrated polymer brush layer on gold, used to study weak interactions. |

| Lysozyme (LYZ) | Model analyte protein for validating bulk correction method. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Non-interacting control protein to determine hydrated brush height. |

| PBS Buffer | Standard running buffer for maintaining physiological conditions. |

| Na₂SO₄ Solution | Salt solution used as the medium for PEG grafting to the gold surface. |

| RCA1 & RCA2 Solutions | Highly effective cleaning agents for preparing ultra-clean sensor surfaces. |

Troubleshooting and Mitigation Strategies

Proactive Bulk Shift Reduction

The most effective approach to bulk response is to prevent it where possible through careful experimental design [7].

- Buffer Matching: Ensure the running buffer and analyte buffer are perfectly matched. Dialyze the analyte against the running buffer or use size exclusion columns for buffer exchange [3].

- Minimize DMSO Differences: If DMSO is necessary for analyte solubility, dialyze against buffer containing the same DMSO concentration and use this dialysate as the running and dilution buffer. Even small differences in DMSO concentration cause large bulk jumps. Cap vials to prevent evaporation [3].

- Prepare Fresh Buffers: Prepare buffers fresh daily, filter through 0.22 µM filters, and degas before use. Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stock [3].

Identification and Diagnostic Tests

- Recognize the Signature: Identify the characteristic 'square' shape in sensorgrams with large, rapid shifts at injection start/end points [7].

- Test with Salt Solutions: To diagnose system response, inject a NaCl dilution series (e.g., 0-50 mM extra NaCl in running buffer) over a plain sensor chip. Every 1 mM salt difference typically gives ~10 RU bulk difference, helping calibrate expected effects [3].

- Check for Carry-Over: Sudden jumps at injection start may indicate carry-over from previous injections. Add extra wash steps between injections, particularly with high-salt or viscous solutions [3].

Addressing Persistent Bulk Effects

Figure 2: A logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing bulk response effects in SPR data.

- Reference Subtraction: If a suitable reference surface is available, use reference channel subtraction to compensate for bulk RI differences [7]. Note that this may not be fully accurate due to surface differences [1].

- Advanced Physical Model: For the most accurate results, particularly for weak interactions or thick surface layers, implement the reference-free physical model that uses the TIR angle for correction [1].

- Excluded Volume Calibration: If the reference and active surfaces respond differently to changes in ionic strength or solvent composition (due to different displaced volumes), create a calibration plot with control solutions of known refractive index to compensate for these excluded volume differences [3].

The bulk response is an inherent challenge in SPR technology that originates from the extended evanescent field probing the solution volume. Without proper correction, it can lead to significant errors in interpreting biomolecular interactions. While traditional reference subtraction methods offer a partial solution, they are often insufficient for precise measurements. The recently developed physical model that uses the TIR angle for bulk response correction without a reference channel represents a significant advancement, enabling the detection of weak interactions previously obscured by bulk effects. By incorporating the protocols and troubleshooting strategies outlined in this application note, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy of their SPR data, leading to more reliable conclusions in interaction analysis.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for studying biomolecular interactions in real-time. Its operation hinges on a fundamental optical phenomenon: the evanescent field. When plane-polarized light hits a thin metal film under total internal reflection (TIR) conditions, the photons' electrical field extends a short distance beyond the reflecting surface [8]. This electromagnetic field, known as the evanescent field, is the primary sensing element of SPR. Although no light propagates away from the interface, the oscillating electric field of the evanescent wave probes the immediate environment above the metal surface, making it exquisitely sensitive to changes in refractive index [8] [9].

The evanescent field is characterized by its exponential decay in intensity with increasing distance from the sensor surface. The field's intensity (I) at a distance (z) from the surface is described by I(z) = I0e^(-z/d), where I0 is the intensity at the surface and d is the decay length or penetration depth [9]. This decay length defines the distance over which the field's intensity drops to 1/e (about 37%) of its original value and is typically several hundred nanometers [10]. For most commercial SPR instruments using light wavelengths between 600-800 nm, the decay length ranges from 300-400 nm [9], defining the effective sensing volume for detecting molecular binding events.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Evanescent Field in SPR

| Parameter | Typical Value/Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Generated under Total Internal Reflection (TIR) conditions | Creates a surface-sensitive probing field without light propagation [8] |

| Field Nature | Electromagnetic field extending from the metal surface | Sensitive to changes in refractive index [9] |

| Decay Profile | Exponential intensity decay with distance | Intensity drops to 1/e (37%) at the decay length [9] |

| Penetration Depth (d) | ~300-400 nm (for λ=600-800 nm) [9] | Defines the effective sensing zone and maximum detection distance |

| 1/e Decay Distance | Empirically measured at ~63 nm for silicon photonic resonators [10] | Determines sensitivity to bound molecules at different distances |

Quantitative Characterization of the Evanescent Field

The exponential decay of the evanescent field has profound implications for SPR detection sensitivity. Because the field intensity diminishes with distance, the SPR response is not uniform throughout the sensing volume. A binding event occurring close to the metal surface will generate a significantly stronger signal than an identical event farther away [9]. For instance, a receptor-ligand binding event within 10 nm of the metal surface generates an SPR response nearly three times greater than the same interaction occurring 300 nm away [9]. This distance-dependent sensitivity must be carefully considered when designing experiments, particularly with large analytes or thick polymer brushes.

The penetration depth of the evanescent field is influenced by the wavelength of the incident light. Longer wavelengths produce evanescent fields that penetrate deeper into the solution but with reduced surface sensitivity [11]. An instrument using 635 nm light will produce a significantly stronger response (0.75° shift) for a 3 nm protein layer compared to an instrument using 890 nm light (0.2° shift) under otherwise identical conditions [11]. This trade-off between penetration depth and surface sensitivity is crucial for selecting appropriate instrument parameters for specific applications.

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Parameters on Evanescent Field and Sensitivity

| Parameter | Effect on Evanescent Field | Impact on Measured SPR Response |

|---|---|---|

| Incident Light Wavelength | Longer wavelengths increase penetration depth but reduce surface sensitivity [11] | 635 nm light: 0.75° shift for 3 nm protein layer vs. 890 nm light: 0.2° shift for same layer [11] |

| Prism Material Refractive Index | Higher index prisms (e.g., SF10 glass) weaken the angular response to surface binding [11] | BK7 prism (n=1.515): 0.75° shift vs. SF10 prism (n=1.723): 0.35° shift for same protein layer [11] |

| Binding Distance from Surface | Exponential decay of field intensity with distance [9] | Binding at 10 nm: ~3x stronger signal than identical binding at 300 nm [9] |

| Analyte Size | Large particles may not fully reside within the most sensitive region of the field | Particles >400 nm do not cause a linear change in refractive index, limiting quantitative analysis [9] |

Diagram 1: Physical origin and signal transduction pathway in SPR. The evanescent field (yellow) decays exponentially from the sensor surface and detects bound analyte, causing a measurable SPR angle shift.

Experimental Protocols for Profiling Field Decay and Correcting Bulk Response

Protocol: Empirical Measurement of Evanescent Field Decay Using Layer-by-Layer Deposition

Purpose: To empirically determine the 1/e decay distance of the evanescent field intensity as a function of distance from the sensor surface.

Materials and Reagents:

- SPR instrument (e.g., BioNavis SPR Navi 220A or similar)

- Gold sensor chips (~50 nm Au thickness)

- Silicon photonic microring resonator chips (as an alternative platform)

- Poly(sodium 4-styrene-sulfonate) (PSS, MW ~70,000 Da)

- Polyethyleneimine (PEI, MW ~750,000 Da)

- Poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH, MW ~56,000 Da)

- Tris buffer (0.5 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.1)

- Purified water (ASTM Type I, 18.2 MΩ·cm)

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Clean gold sensor chips using RCA-1 cleaning solution (5:1:1 v/v H₂O:H₂O₂:NH₄OH at 75°C for 20 min), followed by ethanol rinse and nitrogen drying [1].

- Baseline Measurement: Mount the sensor chip in the SPR instrument and establish a stable baseline in Tris buffer.

- Polymer Multilayer Assembly:

- Inject a 1 mg/mL solution of cationic polymer (e.g., PEI) for 10 minutes at 20 μL/min flow rate to form an initial adhesion layer.

- Rinse with Tris buffer for 5 minutes to remove non-specifically bound polymer.

- Record the SPR angle shift (Δθ₁).

- Inject a 1 mg/mL solution of anionic polymer (e.g., PSS) for 10 minutes.

- Rinse with Tris buffer and record the SPR angle shift (Δθ₂).

- Repeat steps c-e to build multiple polymer bilayers, each adding a consistent thickness increment [10].

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the SPR angle shift versus the number of polymer layers.

- Fit the data to an exponential decay model: Δθ(z) = Δθ₀e^(-z/d)

- Calculate the 1/e decay distance (d) from the fit. Empirical measurements using this method have determined a decay distance of approximately 63 nm for silicon photonic microring resonators [10].

Protocol: Bulk Response Correction Using Simultaneous SPR and TIR Monitoring

Purpose: To accurately correct for the bulk refractive index contribution from analyte molecules in solution that do not bind to the surface.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-parametric SPR instrument (e.g., BioNavis SPR Navi with multi-wavelength capability)

- Gold sensor chips (~50 nm Au thickness)

- Protein analyte (e.g., lysozyme)

- Polymer brush surface (e.g., thiol-terminated PEG, MW 20 kDa)

- PBS buffer (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na₂HPO₄, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4)

- Regeneration solution (if needed, e.g., 10-100 mM HCl)

Procedure:

- Surface Functionalization:

- Prepare a PEG-grafted surface by incubating a clean gold sensor with 0.12 g/L thiol-terminated PEG in 0.9 M Na₂SO₄ for 2 hours with gentle stirring [1].

- Rinse thoroughly with water and store overnight in water before use.

- SPR Experiment Setup:

- Mount the functionalized sensor chip in the MP-SPR instrument.

- Set temperature to 25°C and use a flow rate of 20 μL/min.

- Use a wavelength of 670 nm for optimal sensitivity [1].

- Data Collection:

- Inject a series of lysozyme concentrations (e.g., 0.01-1 g/L) in PBS buffer.

- For each injection, simultaneously record both the SPR angle (minimum) and the TIR angle (total internal reflection) response.

- Include buffer blanks to account for injection artifacts.

- Bulk Response Correction:

- For each lysozyme concentration, apply the correction formula: Δθcorrected = ΔθSPR - (∂θSPR/∂n) / (∂θTIR/∂n) × ΔθTIR

- Where ΔθSPR is the measured SPR angle shift, ΔθTIR is the TIR angle shift, and (∂θSPR/∂n) and (∂θTIR/∂n) are the sensitivities of each angle to bulk refractive index changes [1].

- The TIR angle response (ΔθTIR) serves as an internal reference for the bulk refractive index change.

- Data Interpretation:

- Analyze the corrected binding curves for the PEG-lysozyme interaction.

- Determine kinetic parameters (ka, kd) and equilibrium affinity (KD) from the corrected data. This approach has revealed a weak affinity (KD = 200 μM) between PEG brushes and lysozyme that was previously masked by bulk effects [1].

Diagram 2: Workflow for bulk response correction using simultaneous SPR and TIR angle monitoring. This method reveals weak interactions masked by bulk effect.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Evanescent Field and Bulk Response Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Sensor Chips | ~50 nm Au thickness on glass with ~2 nm Cr adhesion layer [1] | Optimal SPR signal generation; platform for functionalization |

| Thiol-Terminated PEG | MW 20 kDa, PDI <1.07 [1] | Creating protein-repelling polymer brushes to study weak interactions |

| Layer-by-Layer Polymers | PSS (MW ~70,000), PEI (MW ~750,000), PAH (MW ~56,000) [10] | Building controlled thickness multilayers to profile evanescent field decay |

| Model Protein Analyte | Lysozyme (e.g., from chicken egg white, purity ≥90%) [1] | Studying protein-polymer interactions and demonstrating bulk response |

| Buffer Systems | PBS (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na₂HPO₄, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) [1] | Maintaining physiological conditions during binding experiments |

| Cleaning Solutions | RCA-1 (H₂O:H₂O₂:NH₄OH, 5:1:1) and RCA-2 (H₂O:HCl:H₂O₂, 5:1:1) [1] | Ensuring ultraclean sensor surfaces before functionalization |

Implications for Data Interpretation and Experimental Design

Understanding the evanescent field's physical properties is crucial for proper SPR experimental design and data interpretation. The exponential decay profile means SPR is most sensitive to binding events occurring close to the sensor surface. This has particular significance when studying large biomolecular complexes or polymer brushes, where binding may occur at varying distances from the surface [9]. The extended nature of the evanescent field also explains the ubiquitous bulk response effect, where molecules in solution (not surface-bound) contribute to the SPR signal, potentially leading to inaccurate conclusions [1].

The bulk response effect is especially problematic when studying weak interactions requiring high analyte concentrations [4]. Recent research demonstrates that proper bulk correction using the TIR angle can reveal previously hidden interactions, such as the weak affinity (KD = 200 μM) between PEG brushes and lysozyme [1]. This correction is essential for obtaining accurate kinetic parameters, as the bulk response can obscure true binding signals and lead to incorrect estimates of association and dissociation rates.

For small molecule detection, the limited penetration depth presents sensitivity challenges. Molecules with molecular weight below 200 Daltons require sensor chips with high binding capacity to generate sufficient signal [9]. Conversely, for particles larger than 400 nm, quantitative analysis becomes difficult as they may not fully reside within the most sensitive region of the evanescent field [9]. Innovative approaches that exploit large-scale conformational changes, such as the folding of long human telomeric DNA repeats induced by small molecules, can enhance detection by increasing the mass within the sensitive region of the evanescent field [12].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free analytical technique generating thousands of publications annually for the quantitative analysis of biomolecular interactions [13]. A critical, yet often inconvenient, effect that complicates the interpretation of SPR results is the "bulk response"—a signal generated from analyte molecules in solution that does not stem from specific binding to the immobilized ligand on the sensor surface [14]. This effect arises from differences in the refractive index (RI) between the analyte solution and the running buffer [7]. For decades, researchers have relied on standard correction methods, often using a reference channel. However, recent research demonstrates that the bulk response correction method implemented in many commercial instruments is not generally accurate, risking the propagation of questionable conclusions in a substantial body of scientific literature [14]. Proper identification and correction of this artifact are therefore not merely procedural details but are fundamental to reporting accurate and reliable binding affinities and kinetics.

The Consequences of Improper Bulk Correction

Scientific and Commercial Risks

Inaccurate bulk response correction can lead to both false positive and false negative conclusions. It can cause researchers to:

- Overestimate binding responses, leading to incorrect reports of weak interactions.

- Miss subtle but real interactions entirely, as the signal may be obscured by the uncorrected bulk effect.

- Compromise the accuracy of determined affinity (KD) and kinetic rate constants (ka, kd), undermining the validity of structure-activity relationships and mechanistic studies.

The commercial risks are equally significant, particularly in drug development. Inaccurate characterization of a lead compound's binding kinetics can misdirect optimization efforts, resulting in the costly pursuit of ineffective clinical candidates or the premature abandonment of promising therapeutics.

A Case Study: Revealing Hidden Interactions

The gravity of this issue is highlighted by a 2022 study that re-examined the interaction between poly(ethylene glycol) brushes and the protein lysozyme. Using a novel physical model for bulk correction, researchers were able to reveal an interaction at physiological conditions that was previously obscured [14]. This study demonstrated that:

- Proper subtraction of the bulk response was crucial for detecting this specific biomolecular interaction.

- The equilibrium affinity was accurately determined to be a weak KD of 200 µM, partly due to a short-lived interaction (1/koff < 30 s).

- The improved correction method also provided new insights into the dynamics of self-interactions between lysozyme molecules on surfaces.

This case underscores how a widely used but imperfect methodology can obscure scientifically important phenomena, delaying progress in fundamental understanding.

A Robust Methodology for Accurate Bulk Response Correction

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for identifying, mitigating, and correcting for the bulk response in SPR experiments, drawing on best practices and recent advancements in the field.

Experimental Design and Setup

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A carboxymethyl-dextran chip, popular for covalent ligand immobilization via amine coupling [13]. |

| C1 Sensor Chip | A chip with a flatter surface, better suited for analyzing large analytes like nanoparticles to prevent steric hindrance [13]. |

| Running Buffer | The continuous buffer flowing through the instrument. Matching its composition to the analyte buffer is critical to minimize bulk shift [7]. |

| Regeneration Buffer | A solution (e.g., low pH, high salt) used to completely dissociate the analyte-ligand complex between analyte injections without damaging the ligand [7]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein-based blocking additive used to reduce non-specific binding (NSB) [7]. |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant used to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB [7]. |

Ligand Immobilization

- Ligand Selection: Choose the smaller, purest binding partner as the ligand to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio and minimize non-specific binding. If the partner is multivalent, it is typically better suited as the ligand [7].

- Sensor Chip Selection: Select a sensor chip compatible with your ligand's characteristics (e.g., tagged vs. untagged). For large analytes like nanotherapeutics, consider a flatter chip like the C1 to ensure all immobilized ligand is accessible [13].

- Immobilization Level: Use lower ligand densities to avoid mass transport limitations and analyte depletion at the sensor surface. The density should be sufficient to generate a measurable response but should also reflect physiologic densities where possible for biologically relevant data [13] [7].

Analyte Series Preparation

- Concentration Series: Prepare a minimum of 5 analyte concentrations in a serial dilution, ideally spanning from 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value. This ensures evenly spaced sensorgrams for robust kinetic analysis [7].

- Buffer Matching: To minimize the bulk refractive index shift, match the running buffer and analyte buffer as closely as possible. Dissolve the analyte in the running buffer. If additives are necessary for stability, include them in both the running buffer and the analyte sample [7].

Data Acquisition and Artifact Identification

- Run the Experiment: Inject the analyte concentration series over both the active ligand surface and a reference surface.

- Inspect Raw Sensorgrams: Before any data correction, examine the raw sensorgrams for artifacts.

- Bulk Shift Identification: Look for a large, rapid, square-shaped response change precisely at the start and end of the injection. This indicates a difference in refractive index between the sample and running buffer [7].

- Non-Specific Binding (NSB) Test: Run a high analyte concentration over a bare sensor with no immobilized ligand. NSB is present if a significant response is observed and must be mitigated [7].

- Mass Transport Limitation Check: A linear, non-curving association phase can indicate that the binding kinetics is limited by the diffusion of the analyte to the surface rather than the interaction itself [7].

The Svirelis et al. Bulk Correction Protocol

This protocol is based on the physical model verified by Svirelis et al. (2022) and does not require a separate reference surface [14].

Step 1: Data Export and Preparation

- Export the raw sensorgram data (Time vs. Response) for all analyte concentrations from your SPR instrument software.

- Crucial Note: Ensure the data includes a stable baseline region before analyte injection and the entire dissociation phase.

Step 2: Apply the Physical Model for Bulk Correction

- The model determines the specific binding response by accurately decoupling it from the bulk response contribution directly from the sensorgram data, based on the physical properties of the interaction and the SPR system.

- Implementation: The specific mathematical model and its implementation are detailed in the supplementary information of Svirelis et al. (2022) [14]. Researchers are encouraged to consult this source for the precise algorithms.

Step 3: Data Analysis and Validation

- Fit the corrected sensorgrams to appropriate binding models (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) to determine the kinetic rate constants (ka, kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

- Validate the correction by ensuring the residuals (difference between the fitted curve and the data) are randomly distributed.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in this robust SPR experiment and data analysis process.

Figure 1: Workflow for robust SPR data acquisition and analysis.

Quantitative Comparison of Bulk Response Scenarios

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and recommended actions for different bulk response scenarios, from an ideal experiment to one requiring advanced correction.

Table 1: Identification and mitigation strategies for bulk response.

| Scenario | Sensorgram Signature | Impact on Data | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal: Minimal Bulk Effect | Flat baseline during injection; response driven purely by binding kinetics. | Accurate determination of ka, kd, and KD. | Proceed with standard reference subtraction. |

| Moderate: Correctable Bulk Shift | "Square" shift at injection start/end; binding curve is visible atop the shift [7]. | Can obscure true binding response, especially for weak/small molecules. | 1. Improve buffer matching. 2. Apply the physical model by Svirelis et al. [14]. |

| Severe: Uncorrected (Traditional Method) | Large bulk signal dominates, making binding response difficult to distinguish. | High risk of false positives/negatives; kinetic constants are unreliable. | Mandatory use of advanced correction [14]; redesign experiment to minimize bulk effect. |

Discussion and Best Practices

The risk of questionable conclusions in SPR publications is a tangible problem rooted in subtle technical artifacts like the bulk response. Adopting a rigorous, critical approach to experimental design and data analysis is paramount. The following dot script summarizes the logical relationship between poor bulk correction and its ultimate scientific risk, providing a conceptual overview of the core thesis of this application note.

Figure 2: The logical pathway from technical artifact to scientific risk.

To ensure the highest data quality and reliability, researchers should:

- Prioritize Prevention: The most effective strategy is to minimize the bulk effect at the source through meticulous buffer matching.

- Validate Correction Methods: Do not blindly trust the default output of instruments. Critically evaluate sensorgrams and validate the chosen correction method against a known standard if possible.

- Adopt Advanced Models: Implement and use physically accurate models, such as the one presented by Svirelis et al., for bulk correction, moving beyond potentially inadequate standard methods [14].

- Report Transparently: Clearly detail the methods used for bulk response correction in publications, including the model and any software employed, to allow for critical evaluation and reproducibility.

By adhering to these protocols and fostering a culture of rigorous data interrogation, the SPR community can mitigate the risks associated with the bulk response and enhance the reliability of the thousands of publications that rely on this powerful technology each year.

A significant and inconvenient issue in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) sensing is the "bulk response," a signal contribution from molecules in solution that do not actually bind to the sensor surface. This effect arises because the SPR evanescent field extends hundreds of nanometers from the surface, far beyond the thickness of a typical protein. Consequently, when molecules are injected—especially at high concentrations necessary for probing weak interactions—they generate a response simply by being present in this field. This phenomenon, coupled with refractive index (RI) changes in complex samples, generates a large but false sensor signal that has complicated SPR data interpretation for decades [1]. Arguably, the bulk response effect is a major reason why conclusions in many SPR publications may be questionable [1]. This application note examines the limitations of conventional correction methods and outlines a more accurate alternative framework.

The Inadequacy of Standard Correction Methodologies

Limitations of the Reference Channel Approach

The traditional solution for bulk response correction employs a reference channel, a surface designed to be inert, to measure and subtract the bulk contribution. However, this method suffers from critical flaws:

- Imperfect Surface Inertness: The reference channel must perfectly repel all injected molecules to avoid introducing error from non-specific binding, a condition difficult to achieve in practice [1].

- Coating Thickness Discrepancies: Even with perfect repellence, an error is introduced unless the reference channel coating has a thickness identical to that in the sample channel. Any difference in thickness alters the baseline signal and corrupts the subtraction [1].

- Excluded Volume Effects: Differences in ligand density after immobilization can cause the reference and active surfaces to react differently to changes in ionic strength or solvents like DMSO. This excluded volume effect means that a change in solution RI does not affect both channels equally, leading to incomplete correction and artefactual spikes in the sensorgram after subtraction [3].

Shortcomings in Commercial Implementations

Commercial instruments have recently incorporated features for bulk response removal. However, a systematic investigation reveals that these built-in methods are not generally accurate [1]. In one cited study that utilized a commercial correction feature, the data clearly showed remaining bulk responses during injections, indicating that the correction was incomplete [1]. This independent verification underscores that commercial implementations, while a step forward, may not fully resolve the underlying physical complexities of the bulk effect.

A Novel Physical Model for Accurate Bulk Correction

Principle of the Single-Channel Method

A recent methodological advancement provides a more accurate approach that does not require a separate reference channel or surface region. This method uses a physical model to determine the bulk response contribution directly from the same sensor surface, eliminating the variations inherent in a two-channel system [1].

The core of this method involves using the Total Internal Reflection (TIR) angle response as an input to correct the SPR angle signal. The TIR signal is sensitive to bulk RI changes but is largely independent of surface binding events. By leveraging this relationship, the bulk contribution to the SPR signal can be accurately isolated and subtracted, revealing the true binding signal [1].

Experimental Validation: Revealing Hidden Interactions

The power of this method was demonstrated by characterizing the weak interaction between poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) brushes and lysozyme—an interaction that standard commercial correction failed to fully resolve. After applying the accurate bulk correction, the equilibrium affinity was determined to be KD = 200 µM, revealing a short-lived interaction (1/koff < 30 s) that was previously obscured [1]. This case study confirms that proper correction is essential for obtaining reliable insights into weak biomolecular interactions.

Experimental Protocol for Advanced Bulk Response Analysis

Sensor Chip Preparation

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean glass substrates (e.g., from Bionavis) using RCA2 solution (1:1:5 volume of conc. HCl:H₂O₂ (30%):H₂O at 80°C) followed by a 50 W O₂ plasma treatment at 250 mTorr.

- Metal Deposition: Deposit thin metal films (~2 nm Cr and 50 nm Au) via electron beam physical vapor deposition to create sensor chips optimal for a narrow SPR minimum [1].

- Pre-experiment Cleaning: Immediately prior to experiments, clean chips with RCA1 solution (5:1:1 v/v MQ water:H₂O₂:NH₄OH at 75°C for 20 min), incubate in 99.8% EtOH for 10 minutes, and dry with N₂ [1].

Surface Functionalization (Exemplified with PEG)

- Prepare Grafting Solution: Dissolve thiol-terminated PEG (20 kDa) in a freshly prepared and filtered 0.9 M Na₂SO₄ solution at 0.12 g/L concentration.

- Grafting: Incubate the cleaned Au sensor chip in the PEG solution for 2 hours with gentle stirring (e.g., 50 rpm).

- Rinsing: After grafting, rinse the sensor thoroughly with ultrapure water (e.g., ASTM Type I) and dry with N₂. Store the functionalized sensor immersed in water overnight [1].

SPR Experiment and Data Acquisition

- Instrument Setup: Conduct experiments on a suitable SPR instrument (e.g., SPR Navi 220A). Set temperature to 25°C and use a flow rate of 20 µL/min.

- Data Collection: Acquire data for both the SPR angle and the TIR angle at a single wavelength (e.g., 670 nm). Both signals are required for the subsequent correction [1].

- Protein Injection: Inject lysozyme (or analyte of interest) in a standard buffer (e.g., PBS) across a concentration series. For equilibrium analysis, replicate measurements (n≥2) are recommended for all but the lowest concentrations [1].

Data Analysis and Bulk Correction

- Baseline Correction: Perform a linear baseline correction if instrumental drift is consistent throughout the experiment.

- Artifact Compensation: Subtract a very small signal shift (~0.002°) observed in both SPR and TIR angles during buffer injections, attributable to minor injection artifacts like tiny temperature changes.

- Bulk Correction: Apply the physical model to correct each SPR signal using its corresponding TIR angle signal. The model accounts for the thickness of the receptor layer on the surface, which is critical for accuracy [1].

- Calculation: Finally, calculate the average and standard deviation of the corrected response for each analyte concentration.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for implementing the advanced bulk correction protocol.

| Item | Specification / Example | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Chips | Glass substrates with ~2 nm Cr & 50 nm Au [1] | Optimal substrate for generating a narrow and deep SPR minimum. |

| Cleaning Reagents | RCA1 & RCA2 solutions [1] | Ensure an ultraclean, contaminant-free sensor surface prior to functionalization. |

| Functionalizing Molecule | Thiol-terminated PEG (20 kDa) [1] | Creates a well-defined receptor brush layer on the gold surface for interaction studies. |

| Analyte | Lysozyme (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich L6876) [1] | Model protein for validating the method and probing weak interactions. |

| Buffer Salts | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) tablets [1] | Provides a standard, physiologically relevant ionic strength and pH environment. |

| SPR Instrument | Multi-wavelength instrument capable of simultaneous SPR and TIR angle measurement (e.g., SPR Navi) [1] | Hardware capable of acquiring the necessary data streams for the correction model. |

Table 2: Comparison of bulk response correction methods in SPR.

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations / Inadequacies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Channel [1] [3] | Subtracts signal from an inert reference surface. | Conceptually simple; widely available. | Requires perfect repellence and identical coating thickness; fails with excluded volume effects. |

| Commercial Implementation [1] | Proprietary built-in software correction (e.g., PureKinetics). | Integrated into instrument software; convenient. | Not generally accurate; can leave significant residual bulk signals uncorrected. |

| Novel Physical Model [1] | Uses TIR angle from the active surface to model bulk contribution. | No reference channel needed; accounts for receptor layer thickness; more accurate for weak interactions. | Requires specific instrument capability (TIR monitoring); not yet universally available. |

The traditional reliance on reference channels and the trust in built-in commercial corrections for bulk response are insufficient for the most demanding SPR applications, particularly when studying weak interactions or working in complex media. The novel single-channel methodology, which leverages a physical model and TIR correction, provides a demonstrably more accurate path forward. Adopting this rigorous approach is critical for obtaining reliable kinetic and affinity data, ensuring the continued value of SPR in advanced drug development and biophysical research.

Implementing Advanced Correction Methods: A Step-by-Step Guide to Reference-Free Techniques

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a label-free optical technique that has become a cornerstone for real-time biomolecular interaction analysis, enabling the determination of binding affinity and kinetics [15]. However, a significant complication in SPR sensing is the "bulk response" effect. This occurs because the evanescent field extends hundreds of nanometers from the sensor surface—far beyond the thickness of typical protein analytes (2-10 nm). Consequently, molecules in solution that do not bind to the surface still generate a signal, especially at high concentrations necessary for probing weak interactions [1]. This bulk effect has plagued SPR data interpretation for decades and is a major reason why conclusions drawn from thousands of annual SPR publications may be questionable [1].

Traditional approaches to address this issue have relied on reference channels to measure the bulk response. However, this method requires that the reference surface perfectly repels injected molecules while maintaining identical thickness to the sample channel—conditions difficult to achieve in practice [1]. This application note details a novel physical model that accurately determines the bulk response contribution without requiring a separate reference channel or surface region, thereby revealing previously obscured molecular interactions.

Theoretical Foundation of the Novel Bulk Correction Method

Physical Principles of SPR and Bulk Response

SPR occurs when plane-polarized light hits a thin metal film (typically gold) under total internal reflection conditions, generating surface plasmons—collective oscillations of free electrons at the metal-dielectric interface [8]. The evanescent wave generated during this process decays exponentially with distance from the surface, typically extending ~300 nm into the medium [8]. The resonance angle (θ) is highly sensitive to changes in refractive index (RI) within this evanescent field. The bulk response arises from changes in the RI of the solution itself, rather than from surface binding events [1].

The novel method is grounded in the relationship between the SPR signal and the bulk RI. For well-hydrated films, an effective field decay length can quantify the SPR response. The generic expression for the SPR signal (resonance angle shift, Δθ) is:

Δθ = (dθ/dn) × Δn

Where dθ/dn represents the sensitivity of the SPR angle to RI changes, and Δn is the RI change. The bulk contribution constitutes a significant portion of Δn, particularly at high analyte concentrations.

Core Innovation: Reference-Free Bulk Subtraction

The key innovation of this method lies in its use of the Total Internal Reflection (TIR) angle response as the sole input for bulk response correction [1]. Unlike previous approaches that required separate surface regions to obtain the TIR angle [1], this model extracts both SPR and TIR data from the identical sensor surface. The TIR angle is dependent exclusively on bulk properties surrounding the sensor, enabling inline referencing without a separate control channel [8].

The model establishes that proper subtraction of the bulk response must account for the thickness of the receptor layer existing on the surface [1]. This critical adjustment recognizes that the evanescent field samples different regions depending on the vertical distribution of molecular components, ultimately yielding a more accurate representation of true surface binding events.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. Novel Bulk Response Correction Methods

| Feature | Traditional Reference Channel Method | Novel Single-Surface Method |

|---|---|---|

| Requirement | Separate reference surface region | No separate surface region |

| Reference Surface | Must perfectly repel molecules | Not applicable |

| Thickness Matching | Critical for accuracy | Not required |

| Bulk Signal Source | Different surface region | Same sensor surface |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate | Simplified |

| Correction Accuracy | Potentially compromised by surface variations | Enhanced through self-referencing |

Experimental Protocol for Bulk Response Correction

Sensor Surface Preparation

Materials Required:

- SPR sensor chips with ~2 nm Cr and 50 nm Au (optimal thickness for narrow, deep SPR minimum)

- RCA1 cleaning solution (5:1:1 v/v MQ water:H₂O₂:NH₄OH)

- Ethanol (99.8%)

- Thiol-terminated PEG (20 kg/mol) for functionalization

- Na₂SO₄ solution (0.9 M, filtered)

Procedure:

- Clean gold sensor chips using RCA1 solution at 75°C for 20 minutes [1].

- Incubate sensors in 99.8% ethanol for 10 minutes and dry with N₂ [1].

- For PEG functionalization, graft thiol-terminated PEG (0.12 g/L in 0.9 M Na₂SO₄) onto planar gold SPR sensors for 2 hours with 50 rpm stirring [1].

- Thoroughly rinse functionalized sensors with ultrapure water and dry with N₂ [1].

- Store functionalized SPR sensors immersed in ultrapure water overnight before use [1].

SPR Experimental Setup

Equipment and Reagents:

- SPR instrument (e.g., SPR Navi 220A or Biacore X100)

- Running buffer (e.g., PBS: 10 mM Na₂HPO₄, 10 mM NaH₂PO₄, 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, pH 7.4)

- Analyte solutions at varying concentrations (0.25-700 μM range recommended)

Instrument Parameters:

- Temperature: 25°C (controlled)

- Wavelength: 670 nm

- Flow rate: 20 μL/min for analyte injections [1]

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Execution:

- Prime the SPR instrument fluidics system with degassed, filtered running buffer [1].

- Establish a stable baseline with running buffer flowing over the sensor surface.

- Inject analyte solutions at defined concentrations (typically for 200s association phase) [1].

- Monitor dissociation by switching to running buffer (typically for 800s) [1].

- Collect both SPR angle and TIR angle data simultaneously throughout the experiment [1].

- Regenerate the surface between runs using appropriate regeneration solutions (e.g., 20 mM CHAPS, 0.5% SDS, NaOH with methanol) [16].

Data Analysis and Bulk Correction Implementation

Processing Steps:

- Apply a linear baseline correction if instrument drift is consistent throughout the experiment (typically <10⁻⁴ °/min) [1].

- Correct each SPR signal with its corresponding TIR angle signal [1].

- Account for minor injection artifacts (e.g., temperature changes) by subtracting the shift observed when protein concentration approaches zero (typically ~0.002°) [1].

- Apply the physical model to subtract bulk contribution using the TIR response as input [1].

- Calculate average and standard deviation for each analyte concentration from corrected data [1].

Key Calculations: The model utilizes the relationship between SPR angle shift (ΔθSPR) and TIR angle shift (ΔθTIR) to isolate the surface-specific binding signal:

Δθ_corrected = Δθ_SPR - f(Δθ_TIR)

Where the function f incorporates the thickness of the surface receptor layer and the decay characteristics of the evanescent field [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for SPR Bulk Response Correction Experiments

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPR Hardware | Gold sensor chips (~50 nm Au) | Optimal SPR signal generation [8] | Commercial vendors |

| L1 Sensor Chip (Biacore) | Lipid membrane interaction studies [16] | GE Healthcare | |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Immobilization of His-tagged proteins [17] | Nicoya Lifesciences | |

| Surface Chemistry | Thiol-terminated PEG | Creating protein-repelling surfaces [1] | Laysan Bio |

| Carboxymethyl dextran | Hydrogel matrix for ligand immobilization [15] | Biacore | |

| Buffers & Reagents | HBS-EP Buffer (HEPES with surfactant) | Standard running buffer for protein interactions [15] | Biacore |

| PBS Buffer (Phosphate Buffered Saline) | Physiological conditions for biomolecular interactions [17] | Multiple suppliers | |

| Sodium acetate buffers (pH 4.0-5.5) | Acidic immobilization conditions [15] | Biacore | |

| Coupling Chemistry | EDC/NHS amine coupling | Covalent immobilization of protein ligands [15] | Biacore |

| NiCl₂ solution (40 mM) | Charging NTA chips for His-tag capture [17] | Nicoya Lifesciences | |

| Regeneration Solutions | Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-3.0) | Mild regeneration conditions [15] | Biacore |

| NaOH (10-50 mM) | Strong regeneration solution [15] | Biacore | |

| CHAPS detergent (20 mM) | Gentle surface regeneration [1] | Sigma-Aldrich |

Application Case Study: Revealing PEG-Lysozyme Interactions

Experimental Findings

Implementation of this novel bulk correction method revealed previously obscured interactions between poly(ethylene glycol) brushes and the protein lysozyme at physiological conditions [1]. Prior to bulk response correction, these interactions remained undetectable by conventional SPR analysis. After applying the correction model, the equilibrium affinity was determined to be K_D = 200 μM [1].

The corrected data further demonstrated that the interaction is relatively short-lived (1/k_off < 30 s), explaining why it had eluded previous detection [1]. Additionally, the method revealed the dynamics of self-interactions between lysozyme molecules on surfaces [1].

Comparative Data Analysis

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Bulk Response Correction on SPR Data Interpretation

| Parameter | Without Bulk Correction | With Bulk Correction | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-Lysozyme Interaction | Not detectable | K_D = 200 μM | Reveals weak but significant affinity |

| Lysozyme Self-interaction | Obscured by bulk signal | Dynamics revealed | Unveils secondary interaction phenomena |

| Binding Duration | Not applicable | 1/k_off < 30 s | Explains previous non-detection |

| Data Accuracy | Questionable due to bulk contamination | High fidelity | Improves reliability of conclusions |

| Reportable Interactions | Limited to strong binders | Includes weak interactions | Expands application range |

Comparative Analysis with Commercial Systems

Limitations of Existing Implementations

Commercial SPR instruments have recently implemented features for removing bulk response (e.g., PureKinetics by Bionavis). However, these implementations lack general accuracy [1]. One study that utilized a commercial instrument's built-in method showed remaining bulk responses during injections, indicating incomplete correction [1].

The novel method described herein provides more accurate bulk subtraction because it accounts for the thickness of the surface receptor layer, which commercial implementations typically overlook [1]. This represents a significant advancement in SPR data treatment fidelity.

Methodological Advantages

The novel physical model for determining bulk contribution without a separate surface region represents a significant advancement in SPR methodology. By leveraging TIR angle measurements from the same sensor surface and accounting for receptor layer thickness, this approach enables accurate bulk response correction that reveals previously undetectable molecular interactions.

Researchers implementing this method should prioritize:

- Precise surface characterization to determine receptor layer thickness

- Simultaneous SPR and TIR monitoring throughout experiments

- Control of injection artifacts through careful baseline measurement

- Validation with known weak interaction systems to confirm proper implementation

This method extends SPR application beyond strong 1:1 stoichiometric binding into the realm of weak interactions, membrane partitioning, and other phenomena where bulk effects have previously confounded accurate interpretation. Adoption of this approach will improve the accuracy of SPR data generated by instruments worldwide, potentially impacting thousands of annual publications in molecular interaction studies.

Leveraging the Total Internal Reflection (TIR) Angle as a Primary Input

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a cornerstone optical technique for the real-time, label-free analysis of biomolecular interactions, providing critical data on binding kinetics and affinity [18] [19]. A fundamental challenge in quantitative SPR analysis is the discrimination of the specific binding signal from the non-specific bulk refractive index (RI) change caused by the composition of the flowing analyte solution [20]. This bulk effect can obscure true binding events and reduce data accuracy. The Total Internal Reflection (TIR) angle, a property inherent to the sensor interface, offers a robust physical basis for correcting these artifacts. This Application Note details the theory and practical protocols for using the TIR angle as a primary input for bulk response correction, enhancing data fidelity in SPR research.

Theoretical Foundation

Principles of Total Internal Reflection and SPR

Surface Plasmon Resonance functions by exciting charge-density oscillations (plasmons) at a metal-dielectric interface, typically a gold film deposited on a glass prism [8]. This excitation is achieved using the Kretschmann configuration, where plane-polarized light is directed through the prism and reflects off the metal film [18].

When the angle of incident light exceeds the critical angle (θc), Total Internal Reflection (TIR) occurs. Under TIR, an evanescent wave is generated, which propagates a short distance (typically ~200-300 nm) into the medium on the sensor side [18] [8]. The critical angle is defined by the refractive indices of the two media at the interface:

θc = arcsin(na/ng) where ng is the refractive index of the glass prism and na is the refractive index of the aqueous solution [20] [21].

When a thin metal film is present at the interface, the evanescent wave can couple energy to the metal's electron plasma, generating surface plasmons. This coupling, known as Surface Plasmon Resonance, manifests as a sharp dip in the intensity of the reflected light at a specific SPR angle (θSPR), which is highly sensitive to changes in the refractive index within the evanescent field [18] [8].

The Critical Angle as a Sensing and Reference Parameter

The critical angle itself is directly dependent on the bulk refractive index of the solution adjacent to the sensor surface. A change in bulk RI, Δna, causes a proportional shift in the critical angle, Δθc [20]. This relationship provides a direct measure of the bulk effect that is independent of molecular binding events occurring on the sensor surface. In contrast, the SPR angle (θSPR) responds to both the bulk RI change and the surface binding event. By monitoring both θc and θSPR simultaneously, the component of the SPR signal due solely to bulk effects can be quantified and subtracted.

The table below summarizes the key optical phenomena and their roles in sensing:

Table 1: Key Optical Phenomena in TIR and SPR-based Sensing

| Optical Phenomenon | Physical Definition | Dependency | Role in Biosensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Internal Reflection (TIR) | Complete reflection of light at a medium boundary when incident angle > θc [21]. | Refractive indices of glass (ng) and solution (na). |

Underlying mechanism for generating the evanescent field. |

| Critical Angle (θc) | θc = arcsin(na/ng); the minimum angle for TIR [20]. |

Bulk refractive index of the solution (na). |

Primary input for bulk RI change measurement. |

| Evanescent Wave | An electromagnetic field that decays exponentially from the interface under TIR conditions [18]. | Incident angle and wavelength of light. | Probes the local environment near the sensor surface. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Resonance energy transfer from evanescent wave to surface plasmons in a metal film [8]. | Refractive index very close to the metal surface (<200 nm). | Primary transducer for surface binding events. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Dual-Parameter Monitoring for Bulk Response Correction

This protocol describes a methodology for acquiring simultaneous critical angle and SPR angle data to correct for bulk refractive index shifts during a binding experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for TIR/SPR Experiments

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| SPR Instrument | Instrument capable of angular interrogation and imaging (e.g., BIACORE systems, SPR imager). A homemade setup can be constructed for cost-effectiveness [18]. |

| Sensor Chip | Gold-coated (~50 nm) glass slide or bare cover glass for Critical Angle Reflection (CAR) imaging [18] [20]. |

| Prism | High-refractive-index glass prism (e.g., SF10) for coupling light in Kretschmann configuration [18]. |

| Polarizer | To produce p-polarized light, essential for efficient SPR excitation [8]. |

| Immobilization Reagents | Chemical linkers (e.g., PEG-DA, GOPTS), coupling agents (e.g., NHS/EDC), and ligands (antibodies, antigens, receptors) [22]. |

| Running Buffer | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS). Must be filtered and degassed. |

| Analyte Samples | Purified protein, antibody, or small molecule solutions in running buffer. |

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Instrument Setup and Calibration:

- Mount the sensor chip and prism assembly on the instrument stage. Use index-matching oil to ensure optical contact.

- Align the optical components. Flow running buffer through the system at a constant rate (e.g., 20-50 µL/min) to establish a stable baseline.

- Perform an angular scan to obtain the initial reflectivity profile. Identify and record the initial critical angle (θc) and SPR angle (θSPR). For bulk correction, the instrument should be configured to monitor reflectivity at two fixed angles: one at the steepest slope of the SPR dip and one just below the critical angle [20].

Ligand Immobilization:

- Activate the gold sensor surface using a suitable chemistry (e.g., NHS/EDC amine coupling).

- Inject the ligand solution (e.g., an antibody at 10-100 µg/mL in sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0-5.5) over the activated surface to achieve covalent immobilization.

- Block any remaining activated groups with an injection of ethanolamine.

- A reference flow cell should be prepared and subjected to the activation and blocking steps without ligand, to serve as a control for non-specific binding and bulk effects.

Baseline Acquisition:

- Flow running buffer until a stable signal is achieved at both monitoring angles. This establishes the baseline for both the bulk RI signal (via θc) and the combined surface/bulk signal (via θSPR).

Analyte Injection and Data Acquisition:

- Inject the analyte sample over both the ligand-functionalized and reference surfaces.

- Monitor the real-time response (sensorgram) at both the SPR-sensitive angle and the critical angle-sensitive region during the association phase.

- Continue monitoring during the dissociation phase, when running buffer is reintroduced.

Data Processing and Bulk Correction:

- Export the sensorgram data from both detection channels.

- The signal from the critical angle channel (

R_CAR) is predominantly responsive to bulk RI changes. - Apply a correction factor (α) to scale the bulk response to the SPR channel. The corrected specific binding response (

R_corrected) is calculated as:R_corrected = R_SPR - α * R_CAR. The factor α can be determined empirically by injecting a known bulk RI change (e.g., a small percentage of ethanol or DMSO in buffer) and measuring the response in both channels.

Protocol: Validating Performance with Small Molecule Binding

Small molecule detection is particularly challenging for SPR due to low response signals that are easily swamped by bulk effects [19]. This protocol validates the TIR-based correction method using a small molecule- protein interaction.

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Immobilize the protein target (e.g., a kinase) on the sensor surface.

- Prepare a dilution series of the small molecule analyte (e.g., a kinase inhibitor) in running buffer. Include a DMSO concentration matched across all samples to ensure consistent bulk composition.

- Inject each concentration over the surface, recording data from both the SPR and critical angle channels.

- Process the data with and without the bulk correction algorithm.

- Compare the extracted kinetic constants (ka, kd) and equilibrium affinity (KD) from the corrected and uncorrected data. Effective correction will typically result in more reliable and reproducible kinetic fits, especially for low-affinity interactions [22] [19].

Data Analysis and Bulk Response Correction Methods

Quantitative Data Interpretation

The core of this methodology lies in the differential sensitivity of the SPR angle and the critical angle to surface and bulk events. The following table quantifies typical signal behaviors:

Table 3: Signal Response to Different Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | SPR Angle (θSPR) Response | Critical Angle (θc) Response | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer Stable Flow | Stable baseline. | Stable baseline. | System equilibrium. |

| Bulk RI Change (e.g., 1% ethanol pulse). | Significant shift. | Significant, proportional shift. | Non-specific bulk effect. The θc shift directly quantifies the bulk component. |

| Specific Binding (Analyte to immobilized ligand). | Significant shift. | Minimal to no shift. | Specific surface binding event. The θSPR shift is primarily due to mass deposition. |

| Binding with Buffer Dissociation | Signal returns towards original baseline. | Signal returns towards original baseline. | Dissociation of bound analyte. |

Implementing the Correction Algorithm

The simplest and most effective correction model is a linear subtraction. The steps are:

- Calibration: Inject a known bulk refractive index change (Δn) and record the resultant signal changes in the SPR channel (ΔRSPRbulk) and the critical angle channel (ΔRCARbulk). The correction factor is calculated as

α = ΔR_SPR_bulk / ΔR_CAR_bulk. - Application: For any subsequent analyte injection, the corrected binding signal at each time point (t) is:

R_corrected(t) = R_SPR(t) - α * R_CAR(t).

This approach effectively isolates the signal originating from the surface binding event, leading to more accurate sensorgrams for kinetic analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR with Bulk Correction

| Category | Item | Brief Explanation of Function |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Chemistry | Carboxymethylated Dextran (CM5) | A common hydrogel matrix that increases ligand immobilization capacity and reduces non-specific binding. |

| NHS/EDC Chemistry | Standard amine-coupling reagents for covalently immobilizing proteins and other biomolecules containing primary amines. | |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Used to deactivate and block excess reactive groups on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization. | |

| Buffers & Solvents | HBS-EP+ Buffer | A common running buffer (HEPES pH 7.4, NaCl, EDTA, Surfactant P20) that promotes stability and minimizes non-specific binding. |

| Regeneration Solutions | Low pH buffer (e.g., Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0) or other reagents used to break the ligand-analyte complex without damaging the ligand, allowing surface re-use. | |

| DMSO | High-quality solvent for dissolving small molecule compounds. Must be used at a consistent, low concentration (<5% v/v) to avoid excessive bulk shifts. | |

| Calibration & QC | Ethanol or Glycerol Solutions | Used at low percentages (e.g., 0.5-2%) to introduce a controlled bulk RI change for system calibration and determination of correction factor (α). |

| Blank Buffer | Used for baseline stabilization, negative controls, and dissociation phases. |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for biomolecular interaction analysis, generating real-time data on binding affinity and kinetics. However, a significant challenge complicating SPR data interpretation is the "bulk response" effect, where molecules in solution generate signals without binding to the surface. This occurs because the evanescent field extends hundreds of nanometers from the surface—far beyond the thickness of typical analytes like proteins. When molecules are injected, especially at high concentrations necessary for probing weak interactions, even non-binding species contribute to the response due to refractive index (RI) changes in the bulk liquid [1]. This effect haunts SPR studies worldwide and can lead to questionable conclusions in thousands of annual publications if not properly corrected [1]. This application note details practical workflows for accurate bulk response correction, enabling researchers to distinguish true binding events from solution-based artifacts.

Theoretical Background: Understanding the Bulk Response

The bulk response constitutes a significant, binding-independent signal contribution that must be analytically removed to reveal authentic molecular interactions. In SPR systems, the evanescent sensing field typically extends 100-400 nm from the sensor surface, considerably beyond the dimensions of most biological analytes (e.g., proteins measuring 2-10 nm) [1]. This physical principle means that any change in solute concentration within the flow cell during injection alters the local refractive index throughout the sensing volume, generating a substantial signal superimposed upon specific binding signals.

For well-hydrated films, the SPR response can be quantified using an effective field decay length. The total observed signal (Δθtotal) comprises both surface binding (Δθbinding) and bulk solution (Δθbulk) contributions [1]. The bulk contribution is proportional to the RI change (Δn) and the decay length, while the binding contribution depends on the surface coverage and the optical properties of the adlayer. Without correction, this bulk effect can masquerade as binding, particularly when studying weak interactions requiring high analyte concentrations, or when analyzing complex samples with varying RI.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Bulk Response Correction

| Challenge | Impact on Data Quality | Common Experimental Scenarios |

|---|---|---|

| High Analyte Concentrations | Overestimation of binding response | Weak affinity measurements (KD > μM) |

| Complex Samples | False positive binding signals | Serum, lysate, or complex buffer analysis |

| Small Analyte Size | Reduced signal-to-bulk ratio | Fragment-based screening, small molecules |

| Reference Surface Mismatch | Incomplete bulk subtraction | Improper surface functionalization |

Experimental Design for Effective Bulk Correction

Strategic Reference Surface Selection

Proper reference surface design is crucial for effective bulk response subtraction. Two primary approaches exist, each with distinct advantages:

- *Non-functionalized Surface:* A bare surface with no immobilized ligand provides the simplest reference but may inadequately match the hydrodynamic and nonspecific binding properties of the active surface [23] [24].

- *Non-cognate RNA/Protein Control:* Immobilizing a structurally similar but functionally irrelevant biomolecule (e.g., mutant RNA, scrambled peptide) better matches the nonspecific binding characteristics of the active surface. This approach specifically subtracts electrostatic and other nonspecific interactions, revealing only target-specific binding [23].

For RNA-small molecule interactions, using a non-cognate RNA reference has proven particularly effective for subtracting nonspecific binding contributions mediated by electrostatic interactions, which often convolute analysis of weak binders [23].

Immobilization Chemistry Considerations

The choice of immobilization strategy significantly impacts the reliability of bulk correction:

Covalent Immobilization (e.g., CMS chips):

- NHS/EDC amine coupling creates stable surfaces but may yield heterogeneous attachment orientations

- Requires careful optimization of ligand density to minimize mass transport effects

- Generally more resistant to harsh regeneration conditions

Affinity Capture (e.g., Streptavidin-Biotin, His-NTA):

- Provides oriented, uniform ligand presentation

- Preserves biological activity more effectively

- Enables easier surface regeneration in many cases

- Particularly valuable for RNA studies using 5'-biotinylated molecules [23]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Bulk Response Studies

| Reagent/Chip Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CMS Sensor Chip | Carboxymethylated dextran for covalent immobilization | General protein-protein interactions |

| SA Sensor Chip | Streptavidin-functionalized for biotin capture | Biotinylated RNA/DNA, tagged proteins |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Nickel chelation for His-tagged capture | Recombinant His-tagged proteins |

| Membrane Scaffold Protein (MSP) | Nanodisc formation for lipid embedding | Membrane protein-lipid interactions |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Protein-repelling brush layer | Negative controls, polymer interactions |

| HEPES Buffer Saline | Physiological-like running buffer | Biomolecular interaction studies |

Practical Workflow: Data Collection to Analytical Subtraction

Instrument Preparation and Experimental Setup

Begin with thorough system preparation to minimize technical artifacts:

Buffer Matching: Precisely match running buffer and analyte buffer composition, including exact DMSO percentages when working with small molecules dissolved in organic solvents [25]. Even minor differences in salt concentration, pH, or co-solvents create significant bulk shifts.

Ligand Immobilization:

- Dilute biotinylated RNAs to 500 nM in running buffer

- Fold RNA by heating to 95°C for 2 minutes, snap cooling on ice, then incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes [23]

- Immobilize on streptavidin chips at 5 μL/min for 3-12 minutes to achieve 2000-3000 response units (RU)

- For covalent immobilization, optimize density to avoid mass transport limitations [24]

Reference Surface Preparation: Immobilize non-cognate control RNA/protein in reference flow cell using identical immobilization conditions as active surface [23].

Data Collection Parameters

Implement optimized binding protocols to ensure data quality:

- Flow Rate: 20-30 μL/min to minimize mass transport effects [1] [23]

- Association Phase: 2-5 minutes depending on kinetic rates

- Dissociation Phase: 4-10 minutes to observe adequate signal decay

- Analyte Concentration Series: 8-10 concentrations spanning 0.1-10× expected KD in half-log increments [23] [24]

- Regeneration Conditions: Optimize for complete analyte removal without damaging ligand (e.g., 2 M NaCl for mild regeneration, 10 mM glycine pH 2 for acidic regeneration) [25]

Bulk Response Correction Methods

Two robust correction methodologies have emerged for reliable bulk subtraction:

Method 1: Reference Channel Subtraction

This approach utilizes a dedicated reference flow cell containing a non-binding control surface [23] [24].

The workflow involves:

- Simultaneously monitoring active and reference surfaces during analyte injection