A Modern Framework for Surface Spectroscopy Method Validation: Protocols, Applications, and Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive guide to method validation for surface spectroscopy, addressing the critical needs of researchers and development professionals in regulated environments.

A Modern Framework for Surface Spectroscopy Method Validation: Protocols, Applications, and Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to method validation for surface spectroscopy, addressing the critical needs of researchers and development professionals in regulated environments. It bridges the gap between foundational regulatory principles from ICH Q2(R2) and their practical application to techniques like Raman and SERS. The content explores a modern, lifecycle-based approach to validation, from establishing foundational parameters and developing robust methods to troubleshooting common challenges and executing comparative studies. By synthesizing current guidelines, application case studies, and interlaboratory validation data, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to ensure their spectroscopic methods are accurate, reproducible, and fit-for-purpose.

The Regulatory and Conceptual Bedrock of Surface Spectroscopy Validation

The validation of analytical procedures is a critical pillar in pharmaceutical development and quality control, ensuring the reliability of data used to assess drug safety and efficacy. The recent adoption of ICH Q2(R2) and its complementary guideline ICH Q14 represents a significant evolution in regulatory expectations, moving from a prescriptive "check-the-box" approach to a scientific, risk-based lifecycle model [1]. This modernization, also reflected in the latest FDA guidance, addresses technological advancements and emphasizes deeper methodological understanding [2] [1].

For researchers employing surface spectroscopy and other advanced analytical techniques, these guidelines provide a flexible framework for demonstrating method suitability. The core objective remains proving that an analytical procedure is fit-for-purpose for its intended use, whether for identity testing, assay, impurity quantification, or other attributes [3]. The harmonization of these standards under ICH ensures that a method validated in one region is recognized and trusted worldwide, streamlining global regulatory submissions [1].

Core Validation Parameters According to ICH Q2(R2) and FDA

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline outlines the fundamental performance characteristics that must be evaluated to demonstrate that an analytical method is valid. While the specific parameters required depend on the type of method (e.g., identification vs. quantitative assay), the following table summarizes the core attributes and their definitions [1] [3].

Table 1: Core Analytical Method Validation Parameters and Their Definitions

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Typical Application in Quantitative Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the measured value and a reference value accepted as true [1]. | Assessed by analyzing a sample of known concentration (e.g., a reference standard) or via spike/recovery studies [1]. |

| Precision | The degree of agreement among individual test results when the procedure is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings of a homogeneous sample. This includes repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [1]. | Measured as relative standard deviation (RSD) from multiple injections of the same homogeneous sample under defined conditions [4]. |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradants, or matrix components [1]. | Demonstrated by showing the method can distinguish the analyte from other components, often via forced degradation studies [4]. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte [1]. | Established across a specified range using a defined number of concentrations, typically via linear regression analysis [4]. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of the analyte for which the method has demonstrated suitable linearity, accuracy, and precision [1]. | Defined from the low to high concentration level that meets the acceptance criteria for the above parameters [4]. |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated, under the stated experimental conditions [1]. | Based on signal-to-noise ratio, visual evaluation, or statistical approaches (e.g., standard deviation of the response) [4]. |

| Quantitation Limit (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable accuracy and precision [1]. | Determined similarly to LOD, but with the additional requirement of meeting defined accuracy and precision criteria [4]. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH, temperature, flow rate) [1]. | Evaluated during development to identify critical parameters and establish a method control strategy [4]. |

The Orthogonal Method for Accuracy Verification

A key concept reinforced in the modernized guidelines, and explicitly mentioned in the 2025版药典, is the use of an orthogonal method for verifying accuracy when traditional approaches are not feasible [5]. This is particularly relevant for complex analyses such as biologics, complex formulations, or situations where a blank matrix is unavailable (e.g., when an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient is also a key excipient) [5].

An orthogonal method is an independent, validated procedure that is based on fundamentally different scientific principles than the primary method. For instance:

- Primary Method: HPLC (based on liquid chromatography separation)

- Orthogonal Method: Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) (based on electrophoretic mobility) or Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) (based on molecular vibrations) [5]

The principle is that if two methods with independent sources of error produce comparable results, the likelihood of undetected systematic error is low, providing strong evidence for the accuracy of the primary method [5].

The Lifecycle Approach: Integrating Q2(R2) Validation with Q14 Development

A fundamental shift introduced by the simultaneous release of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 is the move toward a holistic lifecycle management of analytical procedures [1] [6]. This model integrates development, validation, and ongoing routine use, moving away from treating validation as a one-time event.

The Role of the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

Central to this lifecycle approach is the Analytical Target Profile (ATP), a concept formalized in ICH Q14 [1]. The ATP is a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and its required performance criteria. It defines what the method needs to achieve before deciding how to achieve it. A well-defined ATP typically includes:

- The analyte to be measured

- The matrix in which it will be measured

- The required performance levels for accuracy, precision, range, etc., justified based on the method's impact on product quality

By defining the ATP at the outset, method development and validation become more efficient, science-based, and risk-focused [1].

Enhanced vs. Minimal Approach to Development

ICH Q14 describes two pathways for analytical procedure development:

- Minimal Approach: A traditional, empirical approach where the focus is on validating the final procedure. Post-approval changes may require more extensive regulatory oversight.

- Enhanced Approach: A systematic, risk-based approach that builds a deeper understanding of the method and its parameters. This enhanced knowledge facilitates a more flexible control strategy and more efficient management of post-approval changes [1] [6].

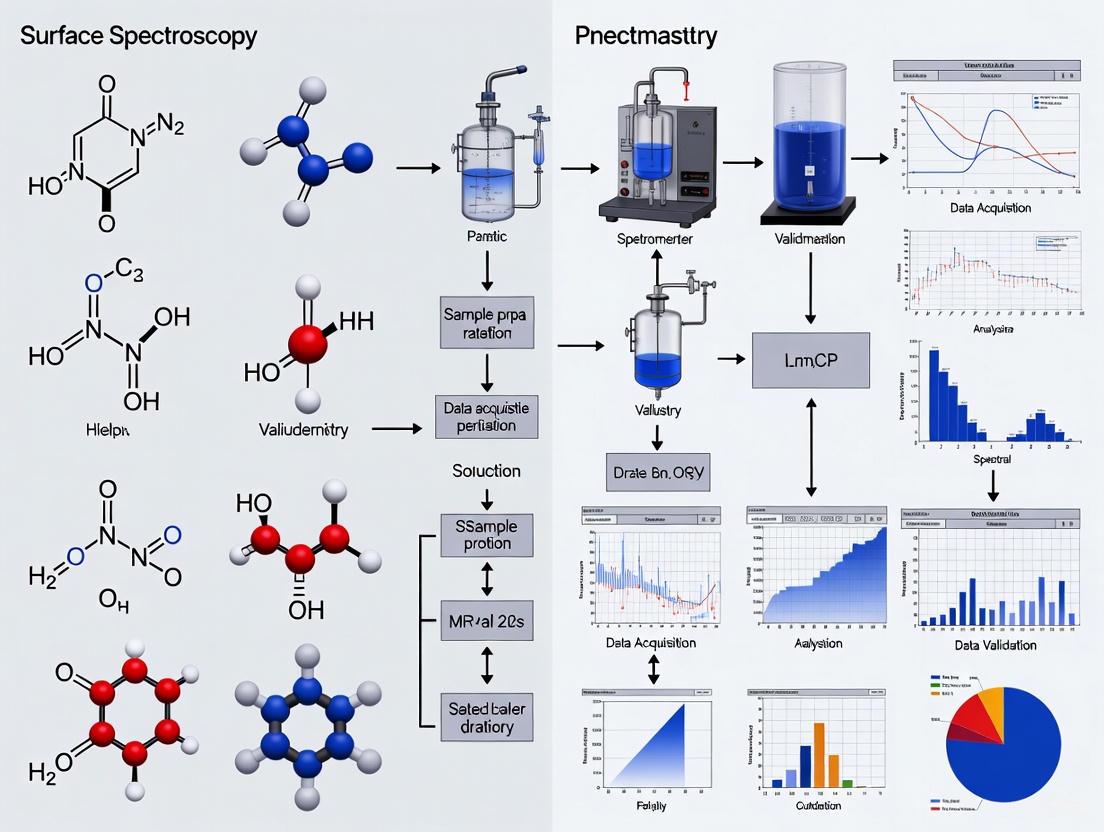

The following diagram illustrates the integrated lifecycle of an analytical procedure, from its initial conception through post-approval monitoring.

Application to Advanced and Spectroscopic Techniques

The revision of ICH Q2(R1) to Q2(R2) was driven in part by the need to address modern analytical procedures that were not adequately covered in the original guideline, such as Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy and Raman Spectroscopy [6]. These techniques, often reliant on multivariate models for calibration, are commonly used in process control and real-time release testing (RTRT) [6].

The new guidelines provide a framework for validating these complex methods, addressing characteristics specific to multivariate methods, such as:

- The definition of validation characteristics that may differ based on the application (e.g., identification vs. quantitation) [6].

- The role of important model parameters (e.g., the number of latent variables) established during development [6].

- The understanding and demonstration of robustness, which may not have a simple quantitative measure [6].

- Considerations for post-approval model verification and maintenance as part of the control strategy [6].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Studies

Protocol for Accuracy Assessment via Orthogonal Method

When the blank matrix is unavailable, using an orthogonal method for accuracy verification is a scientifically rigorous solution [5].

Objective: To verify the accuracy of a primary analytical method (e.g., HPLC for protein content) by comparing its results with those from a fully validated orthogonal method (e.g., CE-SDS).

Materials:

- Samples: A minimum of 3 batches of representative test samples.

- Reference Standards: Qualified reference standards for both methods.

- Instrumentation: The primary analytical system and the orthogonal analytical system, both qualified.

Procedure:

- Orthogonal Method Validation: First, ensure the orthogonal method (CE-SDS) is fully validated, with its own accuracy (e.g., recovery of 98.5-101.2%) demonstrated [5].

- Sample Analysis: Analyze the same set of samples using both the primary (HPLC) and orthogonal (CE-SDS) methods. The analyses should be performed independently.

- Data Comparison: Calculate the absolute difference or relative bias between the results obtained from the two methods for each sample.

Acceptance Criteria: The mean bias between the two methods for the sample set should be within pre-defined, justified limits (e.g., ≤1.5%). Consistency in results across the batches indicates the absence of significant systematic error in the primary method [5].

Protocol for Robustness Testing

Robustness testing is performed during method development to identify critical parameters that must be controlled in the final procedure.

Objective: To evaluate the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters.

Materials:

- Test Sample: A single, homogeneous preparation of the test material.

- Instrumentation: The analytical instrument(s) for which the method is being developed.

Procedure:

- Parameter Selection: Identify key method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH (±0.2 units), column temperature (±2°C), flow rate (±10%)).

- Experimental Design: Utilize a structured experimental design (e.g., Design of Experiments, DoE) to systematically vary the selected parameters.

- Response Monitoring: For each experimental run, measure critical responses such as peak area, retention time, resolution, and tailing factor.

- Data Analysis: Use statistical analysis to determine which parameters have a significant effect on the method responses.

Acceptance Criteria: While there are no universal pass/fail criteria, the method should perform satisfactorily (meeting system suitability criteria) across the normal operating range of the critical parameters. The study establishes permitted tolerances for these parameters in the final method [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful development and validation of a robust analytical method rely on high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function & Importance | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for method calibration and accuracy assessment. The quality of the standard directly impacts the reliability of all quantitative results. | Source from official compendia (e.g., USP, Ph. Eur.) or perform full characterization in-house. Document purity, storage conditions, and stability data [4]. |

| Qualified Impurities | Essential for validating specificity, LOD, LOQ, and for proving a method is stability-indicating. | Must be available in qualified quantities and purities. Forced degradation studies can generate real-world samples containing degradants [4]. |

| Chromatography Columns | The heart of chromatographic separation; critical for achieving specificity, resolution, and reproducibility. | Select appropriate chemistry (e.g., C18, HILIC), particle size, and dimensions. Document alternative columns that are also suitable [4]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Form the mobile phase and sample matrix. Impurities can cause high background noise, baseline drift, and ghost peaks, affecting LOD/LOQ and accuracy. | Use the specified grade (e.g., HPLC, GC). Include source and grade in the method description [4]. |

| System Suitability Standards | A check system used to verify that the entire analytical system (instrument, reagents, column, analyst) is performing adequately at the time of analysis. | Typically a mixture of the analyte and key impurities. Establishes pass/fail criteria for parameters like precision, tailing factor, and resolution [4]. |

The modernized ICH Q2(R2) and FDA guidelines for analytical method validation represent a significant step forward for pharmaceutical analysis. By embracing a science- and risk-based lifecycle approach, they provide a robust yet flexible framework that is applicable to both traditional assays and advanced techniques like spectroscopy. The integration of Q14's development principles with Q2(R2)'s validation requirements ensures that quality is built into the method from the beginning, leading to more reliable, robust, and fit-for-purpose analytical procedures. For scientists in drug development and research, understanding and implementing these core principles is essential for ensuring product quality, meeting regulatory expectations, and ultimately, safeguarding patient safety.

In the realm of pharmaceutical development and surface spectroscopy research, the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) serves as a foundational document that prospectively defines the requirements an analytical procedure must meet to be fit for its intended purpose. Introduced in the ICH Q14 Guideline in 2022, the ATP is a strategic tool that shifts the analytical procedure development paradigm from a reactive to a proactive approach [7]. It describes the necessary quality characteristics of an analytical procedure, ensuring it can reliably measure specific attributes of drug substances and products. For researchers employing sophisticated techniques like Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), the ATP provides a critical framework for establishing method credibility, particularly since such techniques often face perceptions of being poorly reproducible and insufficiently robust for highly regulated environments [8].

The ATP functions similarly to the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) used for drug product development, but it is specifically tailored to analytical procedures. It captures the measuring needs for Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), defines analytical performance characteristics—including system suitability, accuracy, linearity, precision, specificity, range, and robustness—and establishes conditions for change control [7]. By implementing an ATP early in the analytical procedure lifecycle, researchers can systematically guide development, facilitate monitoring, and support continual improvement, thereby ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance throughout the drug development process.

ATP Approaches: Minimal vs. Enhanced

The ICH Q14 guideline describes two distinct approaches to analytical procedure development: the minimal approach and the enhanced approach. Understanding the differences between these methodologies is crucial for selecting the appropriate strategy based on the criticality of the method, the stage of product development, and the required level of understanding.

The Minimal Approach

The minimal approach represents a more traditional pathway to analytical procedure development. It is largely empirical and based on univariate experimentation, where one factor is varied at a time while others are held constant. This approach typically relies on prior knowledge and historical data, focusing on defining a set of operating conditions that consistently produce results meeting pre-defined acceptance criteria. While it may be sufficient for early-stage development or for non-critical methods, the minimal approach offers less systematic understanding of the method's robustness and its operational boundaries. Consequently, any post-approval changes to methods developed using this approach often require more extensive regulatory submissions and validation data [7].

The Enhanced Approach

In contrast, the enhanced approach is a systematic, science- and risk-based framework for developing and maintaining analytical procedures. It provides a more rigorous understanding of the method's performance and its relationship to various input variables. The enhanced approach explicitly incorporates the Analytical Target Profile as its core foundation, along with several other key elements [7]:

- Prior Knowledge: Leveraging existing information from similar methods or products.

- Risk Assessment: Systematically identifying and evaluating potential factors that could impact method performance.

- Uni- or Multi-variate Experiments and/or Modeling: Using structured experimental designs (e.g., Design of Experiments, DoE) to understand the relationship between method inputs and outputs, and to establish a method operable design region.

- Control Strategy: Defining a set of controls that ensure the method performs as intended.

- Proven Acceptable Ranges (PARs): The range of a method parameter that has been demonstrated to produce results meeting ATP criteria.

The following diagram illustrates the structured workflow of the enhanced ATP approach, highlighting its systematic nature.

Comparative Analysis: Minimal vs. Enhanced ATP

The choice between a minimal and an enhanced approach has significant implications for method robustness, regulatory flexibility, and long-term efficiency. The table below provides a structured comparison of these two pathways.

Table 1: Comparison of Minimal and Enhanced Approaches to Analytical Procedure Development

| Feature | Minimal Approach | Enhanced Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Traditional, empirical; based on univariate experimentation [7] | Systematic, science- and risk-based; utilizes structured experimentation [7] |

| Foundation | Prior knowledge and historical data [7] | Analytical Target Profile (ATP) [7] |

| Experimental Design | One-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) [7] | Uni- or multi-variate experiments (e.g., DoE) [7] |

| Understanding | Limited understanding of parameter interactions [7] | Comprehensive understanding of method robustness and parameter interactions [7] |

| Control Strategy | Fixed operating parameters [7] | Proven Acceptable Ranges (PARs) and/or Method Operable Design Region (MODR) [7] |

| Regulatory Flexibility | Lower; changes often require major variation submissions [7] | Higher; facilitates post-approval change management under an established framework [7] |

| Best Application | Early development, non-critical methods [7] | Commercial release, stability testing, and critical methods [7] |

Quantitative Comparison: SERS Reproducibility in an Interlaboratory Study

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy is a powerful technique for quantitative analysis but has historically been challenged by perceptions of poor reproducibility. A landmark interlaboratory study (ILS) provided quantitative data on the reproducibility and trueness of SERS methods, offering a compelling case for the application of ATP principles [8].

The study involved 15 laboratories and 44 researchers using six different SERS methods to quantify adenine concentrations. Each method was defined by a specific Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) detailing the substrate and laser excitation wavelength. The results were analyzed using standardized figures of merit (FoMs) to assess accuracy, trueness, and precision, which align with the performance characteristics typically defined in an ATP [8].

Table 2: Performance Figures of Merit from the SERS Interlaboratory Study [8]

| Figure of Merit | Description | Interpretation in the Context of the ILS |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between measurement results and the accepted reference values [8] | The total prediction error, representing the combination of both trueness and precision (reproducibility) [8] |

| Trueness | Difference between the expected measurement results and the accepted reference values [8] | The systematic component of the total error (e.g., a constant offset) [8] |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent measurement results obtained under reproducible conditions [8] | The random component of the total error, indicating the width of the residuals distribution across different labs [8] |

The study concluded that while achieving high reproducibility across laboratories was challenging, it was possible with rigorously defined SOPs. This finding underscores the value of the ATP concept: defining the requirements before method development ensures that the resulting procedure is capable of producing reliable and comparable results, even when deployed across different instrumental setups and operators [8].

Experimental Protocol: An ATP-Driven Workflow for Surface Spectroscopy

Implementing an ATP for a surface spectroscopy technique like SERS involves a series of deliberate steps. The following protocol, informed by the interlaboratory study and ICH guidelines, provides a general framework for developing a quantitative SERS method under an ATP.

Step 1: Define the Intended Purpose

Clearly articulate what the analytical procedure is intended to measure. For example: "Quantitation of active ingredient concentration in a drug product using SERS" or "Determination of impurity levels in a drug substance" [7].

Step 2: Establish the ATP

Document the ATP, which should include:

- Technology Selection: Justify the choice of SERS (e.g., cAg@785 nm) over other techniques based on sensitivity, specificity, or developmental studies [7] [8].

- Link to CQAs: Summarize how the SERS procedure will provide reliable results about the CQA being assessed [7].

- Performance Characteristics & Acceptance Criteria: Define the required levels for accuracy, precision, specificity, and reportable range, with a rationale for each [7]. For instance, precision must demonstrate a relative standard deviation (RSD) of less than 5% across the reportable range.

Step 3: Develop a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP)

Create a detailed SOP that is sufficient for different operators in different laboratories to execute the method consistently. This was a critical success factor in the SERS ILS [8]. The SOP must specify:

- Materials: The specific SERS-active substrates (e.g., colloidal Ag, solid Au nanostructures), reagents, and standards.

- Sample Preparation: The exact protocol for bringing the analyte into contact with the SERS substrate.

- Instrumentation: The type of spectrometer and laser wavelength.

- Data Acquisition Parameters: Integration time, laser power, number of accumulations.

Step 4: Perform Risk Assessment and DoE

Identify potential factors that could affect method performance (e.g., colloidal aggregation time, laser power, pH). Use a multi-variate experimental design (DoE) to systematically investigate the impact of these factors and their interactions on the method's performance characteristics, as defined in the ATP [7].

Step 5: Establish the Control Strategy

Based on the DoE results, define the control strategy. This includes setting the Proven Acceptable Ranges (PARs) for critical method parameters and defining system suitability tests to ensure the method is functioning correctly each time it is used [7].

Step 6: Validate the Method and Manage Lifecycle

Validate the method according to ICH Q2(R2), ensuring it meets all acceptance criteria outlined in the ATP. Throughout the method's lifecycle, use the ATP as a benchmark for evaluating any proposed changes, ensuring the procedure remains fit for purpose [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SERS-based Quantification

The following table details key materials and reagents required for developing and executing a SERS-based quantitative method, as utilized in studies like the interlaboratory trial [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SERS Quantitative Analysis

| Item | Function | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanostructures | Provides signal enhancement via electromagnetic and chemical mechanisms [8] | Colloidal silver (cAg) or gold (cAu) nanoparticles; solid SERS substrates with Au or Ag nanostructures [8] |

| Analytical Standard | The pure substance used to create calibration curves and validate the method [8] | High-purity adenine; or the specific drug substance/impurity of interest [8] |

| Buffer Solutions | Controls the pH and ionic strength of the analytical matrix, which can influence analyte adsorption and signal stability [8] | Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) or other buffers appropriate for the analyte [8] |

| Aggregating Agent | Induces controlled aggregation of colloidal nanoparticles to create "hot spots" for maximum SERS enhancement [8] | Inorganic salts (e.g., MgSO₄, NaCl) or polyelectrolytes [8] |

| Internal Standard | A reference compound added to samples to correct for variations in signal intensity and instrument response [8] | A deuterated analog of the analyte or a compound with a distinct, non-interfering Raman signal [8] |

The workflow from sample preparation to data analysis in a SERS experiment can be visualized as a sequential process. The following diagram outlines the key stages involved in a typical SERS quantification protocol.

Establishing a well-defined Analytical Target Profile is not merely a regulatory formality but a fundamental practice that ensures the fitness for purpose of analytical procedures. For advanced techniques like surface spectroscopy, which may grapple with reproducibility concerns, the ATP provides a structured framework to build robustness, credibility, and regulatory confidence. The choice between a minimal and enhanced approach has long-term implications for method flexibility and lifecycle management. As demonstrated by interlaboratory studies, rigorous protocol definition—guided by the principles of the ATP—is the key to achieving reproducible and accurate quantitative results. By adopting this proactive and systematic approach, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure their analytical methods consistently deliver high-quality data to support product quality decisions.

Understanding the Role of Instrument Qualification (AIQ/AISQ) in Data Integrity

Table of Contents

- The Foundation of Data Integrity

- From AIQ to AISQ: Evolution of a Framework

- A Risk-Based Approach to Qualification

- The Integrated Lifecycle Model

- Practical Application: The SERS Case Study

- The Essential Toolkit for Reliable Spectroscopy

The Foundation of Data Integrity

In regulated laboratories, data integrity is the assurance that data is complete, consistent, and accurate throughout its entire lifecycle [9]. For researchers in surface spectroscopy, this is not merely a regulatory checkbox; it is the fundamental prerequisite for generating trustworthy and reproducible scientific data. Data integrity ensures that every reportable result, from drug development research to quality control testing, can be relied upon for critical decisions [10].

A robust data integrity model is built on multiple layers, with Analytical Instrument Qualification (and System Qualification (AIQ/AISQ) serving as the foundational technical layer [11]. Imagine a structure where the highest level is the "right analysis for the right reportable result." This top layer depends on the "right analytical procedure," which in turn rests on the "right instrument or system for the job" [11]. If the instrument is not properly qualified, the validity of all subsequent data and results is compromised, regardless of the quality of the analytical methods or the skill of the scientist. Therefore, AIQ/AISQ is not an isolated activity but an integral part of a holistic framework that ensures the validity of every measurement in surface spectroscopy research and development.

From AIQ to AISQ: Evolution of a Framework

The guiding principle for instrument qualification in the pharmaceutical industry is found in the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) General Chapter <1058> [12] [13]. This chapter has undergone a significant evolution, reflecting the increasing complexity of modern analytical instrumentation.

The traditional concept of Analytical Instrument Qualification (AIQ) focused primarily on the hardware components of an instrument. However, modern spectrometers are sophisticated systems where hardware, firmware, and software are deeply integrated. A failure in any of these components can lead to erroneous data. Recognizing this, the modernized framework is now termed Analytical Instrument and System Qualification (AISQ) [12] [13].

This shift to AISQ embodies several critical advancements:

- System-Wide Focus: It expands qualification scope to include software-controlled systems, networks, and firmware, acknowledging that modern devices are dependent on their digital components [12].

- Life Cycle Approach: Qualification is no longer a one-time event but a continuous process that spans the entire operational life of the instrument, from selection and installation to retirement [12] [14].

- Emphasis on Data Integrity: The updated approach explicitly strengthens the link between a qualified system and the generation of complete, traceable, and tamper-proof data [12].

A Risk-Based Approach to Qualification

A core principle of AISQ is that not all instruments require the same level of qualification rigor. The effort and depth of qualification should be proportional to the instrument's complexity and its impact on data integrity and product quality [12] [15]. This is managed through a risk-based classification system that categorizes instruments into three main groups.

The following table outlines these groups, their characteristics, and examples relevant to spectroscopy:

| Group | Type | Description | Common Examples | Qualification & Validation Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Simple Apparatus | Equipment with no measurement capability or standard configuration. Data integrity risk is low. | Vortex mixer, magnetic stirrer, glassware [15] | Minimal to none; typically require only record of use [15] |

| Group B | Intermediate Instruments | Instruments that measure standard quantities but do not generate data. Software is typically firmware-based. | pH meter, balances, ovens [15] | Calibration and basic performance checks. Software is often validated during operational qualification [15] |

| Group C | Complex Instrument Systems | Computerized systems that control instruments, acquire data, and process results. High data integrity risk. | HPLC, Mass Spectrometers, FTIR, NIR, SERS systems [15] [16] | Full instrument qualification and computerized system validation (CSV) [15] |

This classification can be further refined, especially for Group C systems, based on software complexity—from non-configurable software (C1) to configurable (C2) and custom-coded systems (C3)—with each sub-group requiring progressively more rigorous validation efforts [15] [16].

The Integrated Lifecycle Model

The AISQ process is structured around a lifecycle model that ensures instruments remain "fit for intended use" from conception to retirement. While the classic 4Qs model (Design, Installation, Operational, and Performance Qualification) is still recognized, the modern approach favors a more integrated, three-stage lifecycle [13] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and their interconnected activities:

Stage 1: Specification and Selection

This initial phase is critical for success. It involves defining the instrument's intended use through a User Requirement Specification (URS) [13] [14]. The URS is a "living document" that details the operational parameters, performance criteria, and software needs based on the analytical procedures it will support. A well-written URS is the foundation for selecting the right instrument and for all subsequent qualification activities.

Stage 2: Installation, Qualification, and Validation

In this phase, the instrument is installed, and documented evidence is collected to prove it is set up and functions correctly. This integrates traditional qualification steps:

- Installation Qualification (IQ): Verifies the instrument is delivered and installed correctly in the selected environment [17] [14].

- Operational Qualification (OQ): Verifies that the instrument operates according to its specifications in its operating environment [10] [17].

- Performance Qualification (PQ): Confirms the instrument performs consistently for its actual intended use, often using quality control check samples [17] [14].

- Computerized System Validation (CSV): For Group C systems, this runs in parallel, ensuring the software functions reliably and maintains data integrity [12].

Stage 3: Ongoing Performance Verification

Qualification does not end after release. This phase involves continuous activities to ensure the instrument remains in a state of control, including regular calibration, preventive maintenance, system suitability tests, and periodic review of performance data [12] [13]. Any changes, such as software updates or instrument relocations, must be managed through a formal change control process [12].

Practical Application: The SERS Case Study

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) is a powerful surface spectroscopy technique, but its quantitative application has been historically challenged by perceptions of poor reproducibility and robustness [8]. This case study highlights how AISQ principles and rigorous method validation are applied to overcome these challenges.

Experimental Protocol: An Interlaboratory SERS Study

A landmark interlaboratory study (ILS) involving 15 laboratories was conducted to assess the reproducibility and trueness of quantitative SERS methods [8]. The methodology provides an excellent template for validation.

- Objective: To determine if different laboratories could consistently implement a quantitative SERS method for adenine and to compare the reproducibility of different SERS methods [8].

- Materials and Standardization:

- Analyte: Adenine in buffered aqueous solution.

- SERS Substrates: Six different methods, including silver and gold colloids and solid substrates.

- Protocol: A detailed Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) was developed and provided to all participants to ensure methodological consistency [8].

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Each participant received identical kits from the organizing laboratory to prepare calibration and test sets as per the SOP.

- Instrument Qualification: All participating spectrometers (Group C systems) would be expected to have undergone full AIQ and CSV to ensure baseline hardware and software reliability.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Participants performed SERS measurements using their own qualified instruments but followed the centralized SOP. All raw spectral data was sent to the organizing laboratory for a centralized, blind data analysis to estimate reproducibility (precision) and trueness [8].

Results and Comparison of SERS Methods

The centralized analysis calculated key Figures of Merit (FoMs), focusing on reproducibility and trueness as components of overall accuracy [8].

The table below summarizes the hypothetical outcomes for different SERS method types, illustrating how such data is used for comparison:

| SERS Method Type | Reproducibility (Precision) | Trueness (Bias) | Overall Accuracy | Suitability for Regulated Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Colloids @ 785 nm | High | High | High | Strong candidate |

| Silver Colloids @ 633 nm | Moderate | High | Moderate | Requires protocol optimization |

| Solid Planar Substrates | Variable | Moderate | Variable | Method and batch-specific |

This study demonstrated that with a standardized, well-defined protocol and properly qualified instruments, quantitative SERS can achieve the reproducibility required for use in regulated environments [8]. It underscores that method validation and instrument qualification are mutually dependent; a perfectly validated method will fail on an unqualified instrument, and a qualified instrument cannot compensate for a poorly validated method.

The Essential Toolkit for Reliable Spectroscopy

Successful implementation of AISQ and robust surface spectroscopy research relies on a combination of documented procedures and physical standards.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Qualification & Validation |

|---|---|

| User Requirement Specification (URS) | The foundational document defining all instrument and system requirements based on its intended analytical use [16] [14]. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Documents detailing the approved processes for operation, calibration, maintenance, and data handling to ensure consistency [16]. |

| Traceable Reference Standards | Certified materials (e.g., NIST-traceable standards) used for calibration and verification of instrument performance, ensuring metrological traceability [10] [17]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Samples | Characterized samples run before or during an analytical sequence to verify that the total system (instrument, software, method) is performing adequately [9]. |

| Stable Control Samples | Samples used in Ongoing Performance Verification (OPV) to monitor the instrument's stability and performance over time [13]. |

| Audit Trail | A secure, computer-generated, time-stamped record that allows for the reconstruction of all events in the sequence related to an electronic record, which is a critical data integrity control for Group C systems [9] [16]. |

Implementing Robust Surface Spectroscopy Methods from Development to QA

In the pharmaceutical industry, the synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) frequently involves solvent distillation and exchange operations to isolate intermediates or achieve the desired solvent properties for subsequent reaction steps [18]. Traditionally, the monitoring of solvent content during these processes has relied on offline chromatographic techniques such as gas chromatography (GC). While accurate, these methods introduce time delays that prevent real-time process control and optimization [18].

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tool that enables real-time, inline monitoring of chemical processes. This case study objectively compares the performance of Raman spectroscopy against conventional GC analysis for monitoring solvent concentration during distillation and solvent exchange operations in early-phase API synthesis. The validation of this spectroscopic method within the broader framework of surface spectroscopy research demonstrates its potential to enhance efficiency, reduce development timelines, and ensure quality in pharmaceutical manufacturing [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Raman Spectroscopy Instrumentation and Configuration

The experimental setup for Raman spectroscopic analysis utilized a Kaiser Raman RXN2 spectrometer equipped with an Invictus 785-nm NIR diode laser. The system was configured with a spectral coverage of 150–3425 cm⁻¹ and operated at 400 mW of laser power. A low-noise charge-coupled device (CCD) detector cooled to -40°C was employed to minimize dark noise and baseline offset [18].

For inline analysis, a Kaiser Mk II filtered fiber optic probe head was connected to a wet head immersion probe via a fiber optic cable. The probe, constructed of stainless steel with a sapphire window, was 0.5 inches in diameter and 18 inches in length with a short fixed-focus design. This probe complied with ATEX (Atmosphères Explosibles) standards for usage in hazardous environments. Instrument calibration was performed regularly for spectrograph wavelength, laser wavelength, and laser intensity, with performance verification using cyclohexane standards [18].

During distillation or solvent exchange operations, the probe was immersed directly into the reaction mass under constant agitation. Dark spectrum subtraction and cosmic ray filters were applied before each analysis to ensure data quality. The entire system was controlled using HoloReact software (Kaiser Optical Systems Inc.) [18].

Gas Chromatography Reference Method

The conventional GC analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with a 7683 series autosampler and injector, and a flame ionization detector (FID) [18].

For case study 1 (distillation monitoring), a DB-1 column (30 m × 0.53 mm i.d. × 1.5 μm film thickness) was used with nitrogen carrier gas. The FID temperature was set at 300°C, and 1 μL of neat sample was injected with a split ratio of 10:1. The oven temperature program began at 40°C for 4 minutes, ramped to 150°C at 15°C/min, held for 1 minute, then ramped to 280°C at 30°C/min, with a final hold time of 8.33 minutes [18].

For case study 2 (solvent exchange), a DB-624 column (75 m × 0.53 mm i.d. × 3.0 μm film thickness) was employed with similar carrier gas and detection parameters. The injection split ratio was 20:1, and the oven temperature was maintained at 100°C for 7 minutes before increasing to 240°C at 30°C/min, with a final hold time of 8.33 minutes [18].

Calibration Standard Preparation

For quantitative Raman model development, calibration samples were prepared with known solvent concentrations spanning the expected operational ranges [18].

In case study 1, calibration standards for 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran (THF) were prepared by spiking known amounts of the solvent into isolated product from the hydrogenation step. The solvent levels ranged from 1-10%, and each standard was validated using GC analysis to establish reference values [18].

In case study 2, solvent mixtures of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) were prepared in the range of 0.5-10% v/v, corresponding to 0.37-7.4% w/v of MTBE in IPA [18].

Raman Chemometric Model Development

Quantitative Raman analysis involved multiple steps: spectral acquisition, preprocessing, feature selection, and multivariate regression model development. The accumulation times were optimized by adjusting laser exposure time and the number of accumulations to avoid CCD saturation while maintaining sufficient signal-to-noise ratio. For fluorescent compounds, exposure times were decreased and signal intensity was optimized by increasing the number of accumulations [18].

Calibration models were built by correlating the spectral data from prepared standards with reference concentration values obtained from GC analysis. Various preprocessing techniques, including baseline correction, normalization, and scatter correction, were applied to minimize spectral variations unrelated to concentration changes. Partial least squares (PLS) regression was typically employed to develop robust calibration models capable of predicting solvent concentrations in real-time during process operations [18].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Techniques

Table 1: Performance comparison between Raman spectroscopy and gas chromatography for solvent monitoring

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy | Gas Chromatography |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Real-time (continuous) | 20-25 minutes per sample |

| Sample Preparation | None (inline immersion) | Dilution and derivatization often required |

| Sampling Mode | Inline, non-invasive | Offline, requires physical sampling |

| Automation Potential | High (fully automated) | Moderate (autosampler dependent) |

| Multicomponent Analysis | Simultaneous with proper modeling | Sequential |

| Sensitivity | ~0.1-0.5% (dependent on solvent) | ~0.01% |

| Regulatory Acceptance | PAT guidance compliant | Well-established in pharmacopeias |

| Operator Skill Required | Moderate to high | Moderate |

The experimental data from both case studies demonstrated that Raman spectroscopy provided comparable accuracy to GC methods within the studied concentration ranges. For the 2-methyl THF distillation monitoring, the Raman model successfully tracked solvent concentration throughout the process with a root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) of less than 0.5% compared to GC reference values [18].

For the MTBE/IPA solvent exchange operation, the Raman method achieved similar accuracy to GC with the significant advantage of providing continuous real-time data, enabling immediate process adjustments. The technique demonstrated particular strength in monitoring the endpoint of solvent exchange operations, a critical process parameter in API synthesis [18].

Advantages and Limitations in API Synthesis Context

Raman spectroscopy offers several distinct advantages over traditional analytical methods for solvent distillation and exchange operations. The nondestructive nature of analysis preserves sample integrity, while the rapid data acquisition enables real-time process control. The technique is particularly suitable for PAT-based applications and offers ease of automation, significantly reducing analyst intervention [18].

The molecular specificity of Raman spectra, with resolvable features for different solvents, facilitates the development of quantitative models without significant interference from common process variables. Furthermore, models developed during early development stages can typically be extended to commercial manufacturing with minimal bridging studies, accelerating technology transfer [18].

However, practical challenges exist in implementing Raman spectroscopy for solvent monitoring. Fluorescence interference from certain process impurities or API intermediates can obscure the Raman signal, requiring optimization of acquisition parameters or application of advanced data processing techniques. The initial investment for instrumentation and the expertise required for chemometric model development also present higher barriers to entry compared to conventional techniques [18].

Method Validation Framework

Validation Protocols for Spectroscopic Methods

The integration of Raman spectroscopy into solvent monitoring applications requires rigorous method validation aligned with regulatory guidelines for PAT. The validation framework should demonstrate that the spectroscopic method is fit for its intended purpose and provides comparable data to established reference methods [18].

Key validation parameters include specificity, which ensures that the model can distinguish between different solvent systems; accuracy, demonstrated through comparison with reference methods across the validated range; precision, including both repeatability and intermediate precision; and range, establishing the upper and lower solvent concentrations over which the method provides accurate results [18].

The robustness of Raman methods should be evaluated against typical process variations, including temperature fluctuations, concentration changes of other components, and potential solid formation. For quantitative applications, the model's sensitivity should be established through determination of the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ) for each solvent component [18].

Lifecycle Management of Chemometric Models

The development and maintenance of chemometric models follow a structured lifecycle approach. During initial development, experimental design principles should be applied to ensure the calibration set encompasses expected process variations. Model performance must be monitored throughout its deployment, with periodic updates using new calibration standards to account for process changes or instrument drift [18].

The model transfer between different spectrometers requires appropriate calibration transfer techniques, including instrument standardization and mathematical alignment of spectral responses. Documentation should comprehensively cover the model development process, including spectral preprocessing methods, variable selection criteria, and validation results [18].

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

Raman Monitoring Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for quantitative analysis using Raman spectroscopic techniques in solvent distillation and exchange operations:

Diagram 1: Raman spectroscopy monitoring workflow for solvent processes

Data Analysis Pathway

The data analysis pathway for Raman spectroscopic monitoring involves multiple steps from raw spectral acquisition to quantitative concentration prediction:

Diagram 2: Data analysis pathway for Raman spectroscopic monitoring

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for Raman spectroscopy in solvent monitoring

| Item | Specification | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectrometer | Kaiser RXN2 with 785 nm laser | Spectral acquisition | Primary analysis instrument |

| Fiber Optic Probe | Immersion type, ATEX compliant | Inline sampling | Direct process monitoring |

| Calibration Standards | HPLC/GC grade solvents | Model development | Reference for quantitation |

| Chemometric Software | HoloReact, MATLAB, or equivalent | Data processing | Model development and prediction |

| GC System | Agilent 7890A with FID | Reference method | Method validation |

| Chromatography Columns | DB-1, DB-624 | Solvent separation | Reference analysis |

| Sample Chamber | Stray light protection | Atline analysis | Alternative to inline setup |

This case study demonstrates that Raman spectroscopy provides a viable and advantageous alternative to traditional GC analysis for monitoring solvent concentration during distillation and exchange operations in API synthesis. While GC offers slightly higher sensitivity, Raman spectroscopy enables real-time process monitoring with comparable accuracy within the operational ranges studied.

The implementation of Raman spectroscopy as a PAT tool aligns with regulatory encouragement for innovative approaches in pharmaceutical manufacturing. With proper method validation and chemometric model development, this technique can significantly reduce development timelines, enhance process understanding, and facilitate continuous manufacturing in the pharmaceutical industry.

The combination of Raman spectroscopy with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning presents promising opportunities for further advancement in process analytical capabilities. As these digital tools become more integrated with spectroscopic methods, the automation and predictive power of solvent monitoring systems will continue to improve, ultimately enhancing efficiency and quality in pharmaceutical development and manufacturing.

This guide provides an objective comparison of current methodologies for building quantitative models in spectroscopy, framed within the essential context of method validation protocols for surface spectroscopy research.

Comparison of Spectral Data Modeling Approaches

The selection of a modeling approach significantly impacts the performance, interpretability, and validation requirements of a quantitative spectroscopic method. The following table compares the core characteristics of established and emerging techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Chemometric and AI Modeling Approaches for Spectral Data

| Modeling Approach | Typical Applications | Key Strengths | Key Limitations & Validation Considerations | Representative Performance (R²/Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS & Variants (PLS-1, PLS-2, O-PLS) [19] | Quantitative analysis, concentration prediction | Well-understood, highly interpretable, less data hungry, suitable for linear relationships | Performance can degrade with highly non-linear data; Requires careful pre-processing selection [20] | Varies by application and data quality; Often the baseline for comparison [20] |

| Complex-Valued Chemometrics [21] | Systems with strong solvent-analyte interactions, ATR spectroscopy | Improves linearity by incorporating phase information; Physically grounded, reduces systematic errors | Requires complex refractive index data (e.g., via ellipsometry or Kramers-Kronig transformation) | Improved robustness and linearity in interacting systems (e.g., benzene-toluene) vs. absorbance-based models [21] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [20] [19] | Automated feature extraction, complex pattern recognition, large datasets | Can model complex, non-linear relationships; Automatically learns relevant features from raw data | Requires large datasets; "Black box" nature challenges interpretability for regulatory submissions | Can outperform PLS on larger datasets (e.g., waste oil classification); Benefits from pre-processing even with raw data capability [20] |

| Transformer/Attention Models [19] | High-dimensional data, complex relationships requiring context | Powerful pattern recognition; Handles long-range dependencies in data; Potential for enhanced interpretability via attention maps | Emerging technology in chemometrics; Computational complexity; Requires significant expertise and data | Potential to advance predictive power in pharmaceuticals and materials science; Active research area [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Adherence to standardized experimental protocols is fundamental for generating reliable and validated quantitative models.

Protocol for Comparative Model Evaluation

A rigorous, comparative study of linear and deep learning models for spectral analysis outlines a robust methodology for objective evaluation [20].

- Dataset Preparation: Utilize benchmark datasets (e.g., a beer regression dataset with 40 training samples, a waste lubricant oil classification dataset with 273 training samples) with known reference values [20].

- Pre-processing Regimes: Apply multiple pre-processing techniques and their combinations. This includes classical methods (e.g., SNV, derivatives) and wavelet transforms to create a comprehensive set of pre-processed data [20].

- Model Training & Tuning: Train a wide array of models:

- Linear Models: PLS with exhaustive pre-processing selection (9 models).

- Interval Models: iPLS with classical pre-processing or wavelet transforms (28 models).

- Regularized Linear Models: LASSO with wavelet transforms (5 models).

- Deep Learning: CNN with various pre-processing methods (9 models) [20].

- Performance Validation: Use appropriate validation methods (e.g., cross-validation, independent test set) and metrics (e.g., RMSE, accuracy) to evaluate and compare all model and pre-processing combinations objectively [20].

Protocol for Complex-Valued Chemometrics

This emerging, physically-grounded method requires a specific workflow to derive the complex refractive index [21].

- Diagram 1: Workflow for Complex-Valued Chemometrics. This diagram outlines the process of converting conventional intensity spectra into complex refractive index data for more physically-grounded modeling [21].

- Data Acquisition: Measure conventional intensity spectra (e.g., ATR reflectance or transmission spectra) using standard spectroscopic instrumentation [21].

- Complex Refractive Index Retrieval:

- Method A (Kramers-Kronig): Use the Kramers-Kronig relation to derive the real (dispersive) part

n(ν)from the imaginary (absorptive) partk(ν)obtained from the intensity spectrum [21]. - Method B (Iterative Inversion): Employ an iterative optimization procedure based on Fresnel equations or transfer matrix methods to invert the measured spectrum and retrieve the complex refractive index function

ñ(ν) = n(ν) + ik(ν), accounting for the specific sample geometry and measurement setup [21].

- Method A (Kramers-Kronig): Use the Kramers-Kronig relation to derive the real (dispersive) part

- Model Building: Use the resulting

n- andk-spectra as input for classical least squares (CLS) or inverse least squares (ILS) regression, replacing traditional absorbance spectra [21].

Protocol for Analytical Instrument and System Qualification (AISQ)

For drug development, the analytical instrument itself must be qualified under a life cycle approach as per the updated USP general chapter <1058> (now AISQ) [13].

- Phase 1: Specification and Selection: Define the instrument's intended use in a User Requirements Specification (URS), including operating parameters and acceptance criteria from relevant pharmacopoeial chapters. Perform risk assessment and supplier assessment [13].

- Phase 2: Installation, Qualification, and Validation: Install, commission, and qualify the instrument. This phase integrates components, configures software, and involves writing SOPs and user training. The instrument is released for operational use upon completion [13].

- Phase 3: Ongoing Performance Verification (OPV): Continuously demonstrate that the instrument performs against the URS throughout its life cycle. This includes regular calibration, maintenance, change control, and periodic review to ensure it remains in a state of statistical control [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis and Validation

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ag-Cu Alloy Reference Materials [22] | Certified reference materials used for method validation, specifically for evaluating detection limits and accuracy in complex matrices. |

| Ideal Binary Liquid Mixtures (e.g., Benzene-Toluene) [21] | Thermodynamically ideal systems used as model samples to develop and test new chemometric methods without complex intermolecular interference. |

| ATR Crystals (e.g., ZnSe, Diamond) [23] | Enable attenuated total reflection measurement, a common sampling technique in surface spectroscopy for solid and liquid analysis. |

| Ultrapure Water [24] | Critical reagent for sample preparation, dilution, and mobile phase preparation, minimizing background interference in sensitive measurements. |

Validation Procedures and Detection Limits

A critical final step in model building is the determination and validation of detection and quantification limits, which are highly matrix-dependent [22].

- Diagram 2: Detection Limit Determination Workflow. This diagram shows the process of calculating key detection and quantification limits, which are influenced by the sample matrix and background signal [22].

- Define Detection Limits: Clearly define the specific detection limit parameters being calculated [22]:

- LLD (Lower Limit of Detection): The smallest amount of analyte detectable with 95% confidence, typically calculated as 3 times the standard deviation of the background (σB) [22].

- ILD (Instrumental Limit of Detection): The minimum net peak intensity detectable by the instrument with 99.95% confidence [22].

- LOQ (Limit of Quantification): The lowest concentration that can be quantified with specified confidence, often defined as 10σB [22].

- Matrix-Specific Calibration: Analyze a series of standard samples or certified reference materials with known compositions (e.g., AgxCu1-x alloys). Establish a calibration curve for each analyte in the specific matrix of interest [22].

- Accuracy and Recovery Assessment: Validate the method by analyzing samples with known concentrations and calculating the recovery percentage. This confirms the reliability and precision of the analytical method [22].

- Documentation: Report the detection limits with a clear description of the sample matrix, as these limits are significantly influenced by matrix composition. This is essential for method validation dossiers [22].

Solving Common Challenges in Vibrational Spectroscopy Method Development

Mitigating Spectral Complexity and Overlapping Signals

Spectral complexity and overlapping signals present a significant challenge in analytical spectroscopy, particularly in the analysis of complex mixtures found in pharmaceuticals, biological fluids, and forensic samples. This guide objectively compares contemporary strategies—including advanced instrumentation, chemometric data processing, and data fusion approaches—for managing these challenges, framed within rigorous method validation protocols essential for surface spectroscopy research.

Instrumental and Chemometric Approaches: A Comparative Analysis

The selection of an appropriate technique is fundamental to managing spectral complexity. The table below compares the core capabilities of major spectroscopic techniques relevant for complex mixture analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques for Complex Mixtures

| Technique | Typical Spectral Range | Key Strengths | Limitations for Complex Mixtures | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) [25] | 190–780 nm | Simple instrumentation; excellent for quantitative analysis of chromophores. | Limited information richness; poor for identifying specific molecules in mixtures. | HPLC detection; concentration measurement of purified compounds. [25] |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) [25] | 780–2500 nm | Suitable for aqueous samples; can penetrate glass containers. | Non-specific, overlapping overtone/combination bands; requires chemometrics for interpretation. [25] [26] | Agricultural, polymer, and pharmaceutical quality control. [24] [25] |

| Mid-Infrared (IR) [25] | ~4000–400 cm⁻¹ | Rich in structural information; intense, isolated absorption bands. | Incompatible with aqueous samples (typically); can require complex sample preparation. | Material identification; fundamental molecular vibration studies. [25] |

| Raman Spectroscopy [25] | Varies with laser | Weak interference from water/glass; complimentary to IR; specific band information. | Susceptible to fluorescence interference, especially with impurities. [25] [27] | Aqueous systems; analysis of functional groups like -C≡C- and S-S. [25] |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) [28] [27] | Varies with laser | Dramatically enhanced sensitivity; enables trace-level detection; reduces fluorescence. | Protocol-dependent results; requires specialized substrates (e.g., Ag/Au nanoparticles). [28] | Trace analysis in biofluids; detecting low-concentration adulterants in forensic samples. [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Spectral Complexity

Protocol for SERS Serum Analysis with Protocol Standardization

A critical study directly compared five different SERS protocols for analyzing human serum to address the lack of standardization, which hinders the comparison of results between labs [28].

- Objective: To benchmark and standardize protocols for obtaining SERS spectra from human serum using silver nanoparticles [28].

- Sample Preparation: Human serum was analyzed with five different methods. Key variables included the type of substrate, laser power, nanoparticle concentration, and the use of incubation or deproteinization steps [28].

- Data Acquisition: SERS spectra were collected from the same serum sample using all five protocols [28].

- Data Analysis: The resulting spectra were compared for spectral intensity and repeatability. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to quantify the variability within the dataset for each protocol [28].

- Key Findings: While all protocols yielded similar biochemical information (primarily about uric acid and hypoxanthine), they differed significantly in spectral intensity and repeatability. Protocol 3 and Protocol 1 demonstrated the least variability, making them more reliable, while Protocol 2 and Protocol 4 were the least repeatable [28].

Protocol for Spectrofluorimetric Drug Analysis using Chemometrics

A 2025 study developed a novel method for simultaneously quantifying amlodipine and aspirin, showcasing how chemometrics can resolve spectral overlap [29].

- Objective: To develop a sustainable, cost-effective spectrofluorimetric method for simultaneous quantification of amlodipine and aspirin in pharmaceuticals and human plasma [29].

- Sample Preparation: Stock solutions were prepared in ethanol. The calibration set (25 samples) covered 200–800 ng/mL for both analytes. A 1% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in ethanolic medium was used for fluorescence enhancement [29].

- Data Acquisition: Synchronous fluorescence spectra were recorded at a wavelength difference (Δλ) of 100 nm using a spectrofluorometer [29].

- Data Analysis: The genetic algorithm-partial least squares (GA-PLS) regression model was applied. The genetic algorithm optimized the model by reducing the spectral variables to about 10% of the original dataset, maintaining performance with only two latent variables [29].

- Key Findings: The GA-PLS model demonstrated superior performance over conventional PLS, achieving low prediction errors (RRMSEP of 0.93 for amlodipine and 1.24 for aspirin) and high accuracy (98.62–101.90% recovery). The method was validated per ICH guidelines and showed no significant difference from established HPLC methods [29].

Protocol for Trace Detection using Data Fusion and Machine Learning

Research demonstrates that combining multiple spectroscopic techniques through data fusion and machine learning can overcome the limitations of any single instrument [27].

- Objective: To integrate SERS and IR spectroscopy via data fusion for improved trace detection of xylazine in illicit opioid samples [27].

- Sample Preparation: 218 illicit opioid powder samples were finely ground and mixed. For SERS, ~1.5 mg of sample was dissolved in water, mixed with gold nanoparticles, and aggregated with MgSO₄. For FTIR, a powdered aliquot was placed on a diamond ATR crystal [27].

- Data Acquisition: SERS spectra (200–2000 cm⁻¹) were collected with a portable Raman spectrometer. FTIR spectra (650–4000 cm⁻¹) were collected with a portable FTIR spectrometer [27].

- Data Analysis: Three data fusion strategies were tested with RF, SVM, and KNN classifiers, optimized via a 5-fold cross-validation grid search [27].

- Hybrid (Low-Level): SERS and IR spectra were concatenated.

- Mid-Level: Features were extracted from both SERS and IR spectra and then combined.

- High-Level: Predictions from separate SERS and IR models were fused, applying a 90% voting weight to the SERS model [27].

- Key Findings: The Random Forest (RF) classifier was optimal for all fusion strategies. The high-level fusion approach achieved the best performance with 96% sensitivity, 88% specificity, and a 92% F1 score, effectively leveraging the sensitivity of SERS without compromising on the information from IR [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Data Fusion Strategies with Random Forest [27]

| Data Fusion Strategy | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 Score | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid (Low-Level) | 88% | 88% | — | Simple concatenation of raw data. |

| Mid-Level | 92% | 88% | — | Uses extracted features, reducing dimensionality. |

| High-Level | 96% | 88% | 92% | Allows weighted voting from best-performing model (90% SERS). |

Visualizing Workflows for Mitigating Spectral Complexity

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for the key experimental protocols discussed, providing a clear roadmap for implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the described protocols requires specific materials. The following table details key reagents and their functions in mitigating spectral complexity.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Spectral Complexity Mitigation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [27] | SERS substrate for trace detection. | Provide massive signal enhancement, enabling detection of analytes at very low concentrations (e.g., trace xylazine in opioids). [27] |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) [28] | SERS substrate for biofluid analysis. | Commonly used with biofluids like serum to enhance the Raman signal of biomolecules. [28] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [29] | Surfactant for fluorescence enhancement. | Forms micelles in ethanolic medium, improving fluorescence signal and spectral characteristics in spectrofluorimetry. [29] |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [29] | Chemometric variable selection tool. | Intelligently selects the most informative spectral variables, reducing noise and improving PLS model robustness and accuracy. [29] |

| Random Forest (RF) Classifier [27] | Machine learning algorithm for classification. | Consistently identified as a high-performing model for complex spectral data, especially when used with data fusion strategies. [27] |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [28] [26] | Exploratory data analysis tool. | Used to assess dataset variability and repeatability, crucial for validating the robustness of analytical protocols. [28] |

Navigating the Limitations of Portable vs. Benchtop Spectrometers

The choice between portable and benchtop spectrometers represents a critical decision point in analytical method development, particularly within regulated industries like pharmaceutical research and development. While benchtop instruments have long been the gold standard for laboratory analysis, technological advancements are rapidly narrowing the performance gap with portable alternatives. This evolution necessitates a clear, evidence-based understanding of the capabilities and limitations of each platform to ensure fitness for intended use within a rigorous method validation framework.

The fundamental distinction lies in their operational design: benchtop spectrometers are stationary, high-performance instruments intended for controlled laboratory environments, whereas portable spectrometers are compact, field-deployable devices that bring analytical capabilities directly to the sample source. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance characteristics, supported by recent experimental data and structured within the context of analytical instrument qualification protocols.

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics and Experimental Data

Direct comparative studies provide the most reliable evidence for evaluating the practical performance of benchtop versus portable spectrometers. The following data, synthesized from recent research publications, highlights trends in accuracy, operational specifications, and suitability for various analytical tasks.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Benchtop and Portable NIR Spectrometers in Application Studies

| Application Field | Benchtop Model (Performance) | Portable Model (Performance) | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquito Age Grading | Labspec 4i (94% accuracy) | NIRvascan (90% accuracy) | Predictive Accuracy (ANN Model) | [30] |

| Mosquito Blood Feed History | Labspec 4i (82.8% accuracy) | NIRvascan (71.4% accuracy) | Predictive Accuracy (ANN Model) | [30] |

| Wood Properties (Eucalyptus) | Not Specified (R²p: 0.69 - 0.93) | Not Specified (R²p: 0.58 - 0.80) | Prediction Coefficient (PLS-R Model) | [31] |

| Wood Properties (Corymbia) | Not Specified (R²p: 0.82 - 0.96) | Not Specified (R²p: 0.69 - 0.81) | Prediction Coefficient (PLS-R Model) | [31] |

| Operational Wavelength | 350 - 2500 nm | 900 - 1700 nm | Spectral Range | [30] |

Table 2: General Characteristics and Operational Limitations

| Feature | Benchtop Spectrometers | Portable Spectrometers |

|---|---|---|

| Cost & Investment | High upfront cost (~$60,000), hidden maintenance fees [30] | More affordable, lower upfront cost and maintenance [32] |

| Portability & Use Case | Stationary; requires dedicated lab space [32] | On-the-go analysis in field, production floor, or supplier sites [32] |

| Operational Complexity | Often requires skilled operators [32] | Intuitive interfaces, minimal training requirements [32] |

| Data Integration | Typically laboratory information systems | Cloud-based software for data access from anywhere [32] |

| Typical Applications | High-precision quantification, reference methods | Rapid screening, field identification, supply chain checks [32] |

The experimental data in Table 1 reveals a consistent but narrowing performance gap. In entomological research, the portable NIRvascan demonstrated slightly lower but comparable accuracy to the benchtop Labspec 4i for age classification of mosquitoes, a critical parameter in vector-borne disease studies [30]. A more significant discrepancy was observed in classifying blood-feeding history, a complex physiological trait [30]. Similarly, in forestry bioenergy research, predictive models for wood properties developed with benchtop NIR data consistently yielded higher coefficients of determination (R²p) compared to those from portable instruments, though the portable models remained functionally useful for screening purposes [31].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Validation

For researchers validating a portable spectrometer against an established benchtop method, a rigorous experimental protocol is essential. The following workflow, derived from published methodologies, ensures a systematic comparison.

Sample Preparation and Selection

The foundation of any valid comparison is a representative and well-characterized sample set. For instance, in the mosquito study, three separate cohorts of laboratory-reared Aedes aegypti were reared and collected at precise age groups (1, 10, and 17 days old), with additional cohorts subjected to controlled blood-feeding regimens [30]. In wood analysis, samples from multiple clones and longitudinal positions in the tree were ground to create a homogeneous composite for analysis [31]. The sample set must encompass the natural variability expected in the analyte and include samples with known reference values.

Instrument Qualification and Spectral Acquisition

Prior to analysis, both instruments should undergo appropriate qualification checks following guidelines such as those in USP general chapter <1058> on Analytical Instrument Qualification (AIQ) [13]. This ensures they are metrologically capable and in a state of control. Scanning protocols must be standardized. For the benchtop Labspec 4i, this involved calibrating with a spectralon panel and positioning a fiber optic probe 2mm above the mosquito's head and thorax [30]. The portable NIRvascan was operated via a smartphone connected via Bluetooth [30]. Each sample should be scanned on both instruments in a randomized order to avoid systematic bias.

Chemometric Model Development and Validation

The collected spectra are used to develop predictive models using algorithms like Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) or Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS-R) [30] [31]. The critical step is to use independent validation sets—samples not used to train the model—to assess predictive accuracy. Performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, R²p, root mean square error) for both the benchtop and portable-derived models are then compared objectively to quantify the performance gap for the specific application.

Analytical Instrument Qualification within a Validated Framework

Integrating a new spectrometer, especially a portable one, into a regulated research environment requires adherence to a formal qualification lifecycle. The updated USP <1058> framework, now termed Analytical Instrument and System Qualification (AISQ), provides a structured, risk-based approach [13].

This lifecycle model aligns with FDA process validation guidance and involves three integrated phases [13]:

- Phase 1: Specification and Selection: The process is initiated by creating a User Requirements Specification (URS) that meticulously defines the instrument's intended use, including operating parameters and acceptance criteria derived from mandatory pharmacopoeial chapters [13]. This URS is the primary tool for selecting between a portable or benchtop system.