The Essential IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the IUPAC Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis, a critical resource for ensuring terminology consistency in analytical sciences.

The Essential IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the IUPAC Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis, a critical resource for ensuring terminology consistency in analytical sciences. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational concepts, methodological applications, and practical implementation of standardized surface analysis terminology. The content bridges the gap between IUPAC recommendations and ISO standards, addressing techniques from XPS to emerging methods like atom probe tomography, to enhance data reproducibility, cross-disciplinary communication, and regulatory compliance in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding IUPAC's Role in Surface Analysis Terminology

The Authoritative Role of IUPAC in Chemistry

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) serves as the universally recognized authority on chemical nomenclature and terminology [1] [2]. Established in 1919, IUPAC's primary mission involves creating unambiguous, consistent nomenclature and terminology systems across all chemical disciplines [1] [2]. This standardization work ensures that when chemists use terms like "surface" or "interface," they convey precise, consistent meanings that enable accurate international scientific communication and data exchange [3].

Two key IUPAC bodies lead these standardization efforts: Division VIII – Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation and the Interdivisional Committee on Terminology, Nomenclature, and Symbols [1]. These groups develop comprehensive recommendations published through various channels including IUPAC's journal Pure and Applied Chemistry (which becomes freely available one year after publication), the IUPAC Standards Online database, and the famous IUPAC Color Books that provide definitive guides for different chemical subdisciplines [1] [2].

IUPAC Nomenclature Systems and Principles

IUPAC has developed multiple systematic approaches for naming chemical compounds, each serving different chemical contexts [2]. The table below summarizes the primary nomenclature systems used in organic chemistry.

Table 1: IUPAC Organic Chemistry Nomenclature Systems

| System Type | Fundamental Principle | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Substitutive | Replacing hydrogen atoms with functional groups indicated by prefixes/suffixes | Most widely used system for organic compounds |

| Radicofunctional | Naming functional classes as main group with remainder as radical(s) | Limited use for specific compound classes |

| Additive | Adding atoms to a parent structure (e.g., indicated by 'hydro-' prefix) | Mainly for hydrogen addition |

| Subtractive | Removing atoms from a parent structure (e.g., indicated by 'dehydro-' prefix) | Primarily in natural products chemistry |

| Replacement | Replacing carbon atoms in a chain with other atoms | Used when simplification results (e.g., PEGs) |

IUPAC also establishes precise typographic conventions for chemical nomenclature, including rules for capitalization, italicization, and punctuation [2]. For instance, stereochemical descriptors like cis, trans, R, and S are italicized, while prefixes such as "cyclo-" and "iso-" are considered part of the main name and capitalized accordingly at the beginning of sentences [2].

Standardization in Surface Chemical Analysis

Fundamental Terminology in Surface Analysis

In surface chemical analysis, IUPAC provides precise definitions that distinguish between related concepts [3]. The term "surface" itself has multiple nuanced definitions depending on context:

- Surface: The "outer portion" of a sample with undefined depth, used in general discussions of outside regions [3]

- Physical Surface: The specific atomic layer that contacts vacuum, representing the true outermost atomic layer [3]

- Experimental Surface: The sample portion that interacts significantly with analytical radiation or particles, determined by measurement volume requirements [3]

These precise distinctions are critical for surface science researchers who must accurately describe their experimental conditions and results [3] [4].

IUPAC maintains several important resources specifically for surface chemical analysis terminology:

Table 2: IUPAC Resources for Surface Chemical Analysis Terminology

| Resource Name | Description | Key Features | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Book (Online) | Interactive version of Compendium of Chemical Terminology | Browseable alphabetical/thematic indexes; digital formats available | Some entries may need updating; divisions conducting reviews [5] |

| Glossary of Methods and Terms in Surface Chemical Analysis | Formal vocabulary for surface analysis concepts | Covers electron, ion, and photon spectroscopy of surfaces | Provisional Recommendations (2019) under review [4] |

| Orange Book (4th Edition, 2023) | Compendium of Terminology in Analytical Chemistry | New chapter on Analytical Chemistry of Surfaces; aligns with latest ISO/JCGM standards | Published January 2023 [6] |

The Gold Book (Compendium of Chemical Terminology), while foundational, carries a note that some definitions may not reflect the most current chemical understanding as the online version has not been updated in several years, though IUPAC divisions are working to review and update entries [5].

IUPAC's Evolving Role in the Digital Age

FAIR Data Initiatives

IUPAC is actively working to align chemical data standards with FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) through the WorldFAIR Project [7]. These initiatives focus on:

- Developing guidelines, tools, and validation services for FAIR data sharing and storage

- Addressing standards gaps that limit chemistry in both academic and industrial settings

- Engaging stakeholders to increase machine-readable chemical data availability [7]

The IUPAC FAIR Chemistry Protocol Services project represents a new service prototype supporting standard programmatic chemical data exchange and validation, reflecting IUPAC's adaptation to digital research environments [7].

Emerging Technologies Recognition

IUPAC's Top Ten Emerging Technologies in Chemistry initiative, most recently published in 2025, highlights IUPAC's role in identifying transformative innovations [8]. The 2025 list includes technologies such as:

- Direct Air Capture and Electrochemical Carbon Capture and Conversion for sustainability

- Multimodal Foundation Models for Structure Elucidation representing AI/ML applications

- Nanochain Biosensors and Single-Atom Catalysis for advanced materials and health [8]

This initiative demonstrates IUPAC's ongoing relevance in showcasing chemistry's potential to address urgent societal challenges through technological innovation [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chemical Measurement Process (CMP) Framework

IUPAC has established a standardized framework for describing the Chemical Measurement Process (CMP), defined as "a fully specified analytical method that has achieved a state of statistical control" [9]. This framework includes:

- Sample Preparation: Transformation of the test portion into a form suitable for instrumental measurement

- Instrumental Measurement: Conversion of the analyte amount (x) to a signal or response (y)

- Evaluation Unit: Transformation of the response (y) back into an estimate (x̂) of the original analyte amount [9]

The CMP structure provides a systematic approach for characterizing analytical methods and their performance metrics, enabling meaningful comparison between different analytical techniques [9].

Characterization of Method Performance

IUPAC recommendations provide detailed nomenclature for evaluating analytical method performance, including fundamental quantities related to:

- Observed Response and Calibration Functions

- Precision and Accuracy Measures including variance and standard error

- Detection and Quantification Capabilities

- Uncertainty Components and Error Propagation [9]

This standardized approach to method validation ensures consistency across laboratories and analytical techniques, which is particularly crucial in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development [6] [9].

Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Chemical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Provide known surface composition for instrument calibration | Essential for quality control in quantitative surface analysis |

| Calibration Standards | Establish correlation between instrument response and analyte concentration | Required for method validation per IUPAC/ISO guidelines |

| Ultra-high Vacuum Systems | Enable preparation and maintenance of clean surfaces | Critical for physical surface characterization studies |

| Characterized Substrates | Provide consistent surface properties for reproducible measurements | Gold, silicon, and mica surfaces with specified roughness/crystallinity |

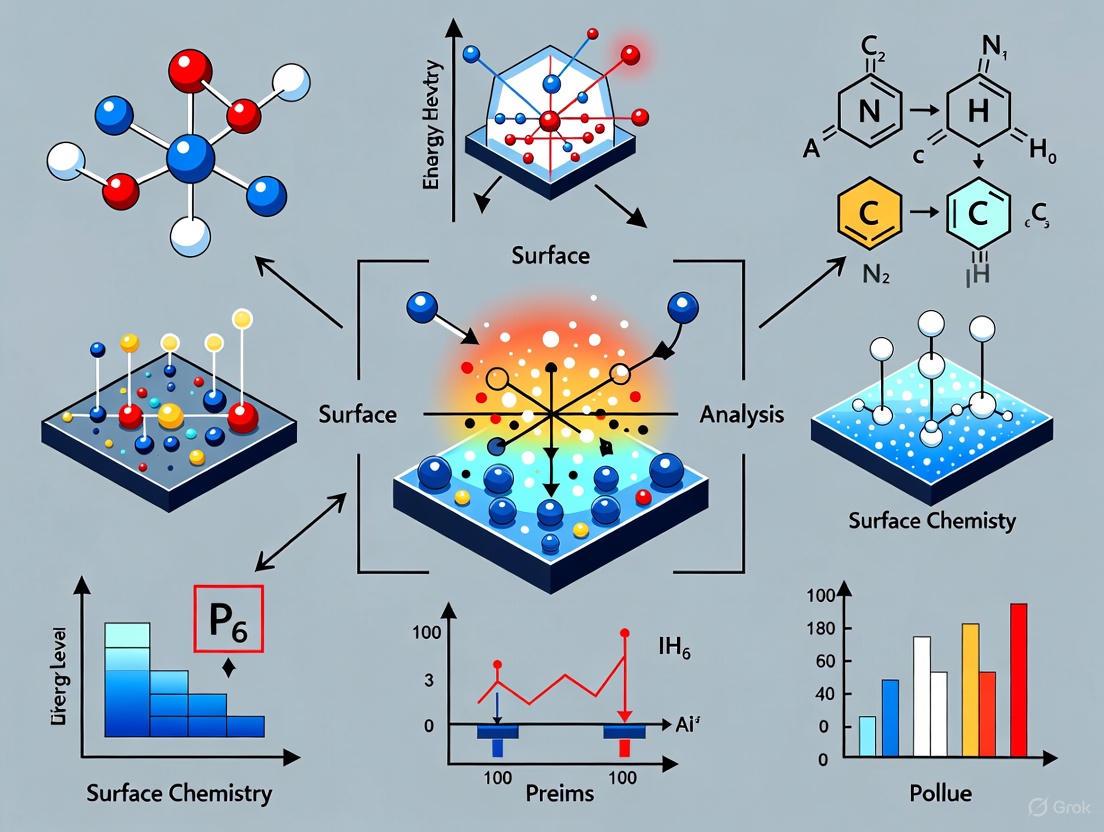

Workflow Diagram for IUPAC Standard Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for implementing IUPAC standards in surface chemical analysis research:

IUPAC maintains its position as the global authority in chemical standardization through continuous development of nomenclature systems, adaptation to digital research environments, and recognition of emerging technologies. The organization's precise definitions for surface chemical analysis terminology, combined with its framework for characterizing analytical methods and its initiatives toward FAIR data principles, ensure that chemical research maintains consistency, precision, and interoperability across international boundaries and scientific disciplines. As chemical research evolves with new technologies, IUPAC's standardization work remains fundamental to accurate scientific communication and collaboration.

Scope and Purpose of the Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary

The Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis represents a formal vocabulary established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) to standardize terminology in the field of surface analytical chemistry [4] [10]. This comprehensive document provides clear, authoritative definitions for researchers who utilize surface chemical analysis or need to interpret results but may not be specialists in surface chemistry or surface spectroscopy [11]. The glossary serves as a critical update to the previous version published in 1997, reflecting the substantial technical advances that have occurred in surface analysis methodologies over the intervening decades [11].

The primary objective of this glossary is to ensure universality and consistency in terminology throughout the field of Surface Analytical Chemistry [11]. This consistency is fundamental to assuring reproducibility and comparability of results across different laboratories and research initiatives worldwide. By establishing a common language, the glossary facilitates clearer communication among scientists, enhances the reliability of scientific publications, and supports quality assurance in both academic and industrial settings where surface analysis techniques are employed.

Scope of the Glossary

Analytical Techniques Covered

The scope of the glossary is carefully defined to include analytical techniques where beams of electrons, ions, or photons are incident on a material surface, and scattered or emitted electrons, ions, or photons are detected from within approximately 10 nanometers of the surface [11]. This encompasses a wide range of spectroscopic methods used for chemical analysis of surfaces under vacuum conditions, as well as surfaces immersed in liquid environments [11]. The glossary systematically covers the principal methods of surface chemical analysis along with notes describing common variants of these techniques, providing researchers with a comprehensive overview of the available analytical tools [11].

Delimitations and Exclusions

A key delimitation of this glossary is its specific exclusion of methods that yield purely structural and morphological information without chemical specificity [11]. Consequently, techniques such as diffraction methods and imaging microscopies fall outside its scope. This focused approach ensures the glossary maintains its specialized utility for researchers requiring precise definitions related to the chemical composition and chemical state information obtained from surface analysis techniques.

Table: Scope Boundaries of the IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary

| Included Techniques | Excluded Techniques |

|---|---|

| Electron spectroscopy of surfaces | Pure structural determination methods |

| Ion spectroscopy of surfaces | Diffraction methods |

| Photon spectroscopy of surfaces | Pure imaging microscopies |

| Methods analyzing ~10 nm surface region | Techniques analyzing bulk properties |

| Vacuum-based surface analysis | |

| In-liquid surface analysis |

Purpose and Scientific Significance

Standardization of Terminology

The fundamental purpose of this glossary is to provide a standardized vocabulary that promotes consistency in terminology across the field of surface analytical chemistry [11]. This standardization is particularly crucial for a multidisciplinary field where researchers from various backgrounds (including chemistry, materials science, biology, and engineering) employ surface analysis techniques and must communicate their findings unambiguously. The IUPAC recommendations ensure that terms have precisely defined meanings, reducing the potential for misinterpretation that can arise when inconsistent terminology is used in scientific literature, technical reports, and method specifications.

Relationship with International Standards

This IUPAC glossary has been developed with careful coordination with existing international standards, particularly those established by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) [11]. The document selectively incorporates topics from ISO 18115: Surface Chemical Analysis—Vocabulary, which consists of two parts: ISO 18115-1, covering general terms and terms used in spectroscopy (2013), and ISO 18115-2, addressing terms used in scanning-probe microscopy (2013) [11]. The terminology taken from these ISO standards is reproduced with permission, and the definitions also comply with the International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM) [11]. This alignment with established international standards ensures global recognition and adoption of the terminology.

Structural Organization of the Glossary

Systematic Arrangement of Content

The glossary is organized into two principal sections that facilitate both learning and reference use. Section 2 contains definitions of the principal methods used in surface chemical analysis, accompanied by notes that describe common variants of these core techniques [11]. This structure introduces researchers to the full spectrum of surface chemical analysis methods available. Section 3 provides definitions of terms associated with the various methods described in the previous section, creating a comprehensive terminological resource [11]. This logical organization allows users to first understand the analytical approaches and then explore the specific terminology associated with each method.

Development and Review Process

The glossary was developed through IUPAC's rigorous review procedures, which include a period of public review where provisional recommendations are made widely available to allow interested parties to provide comments before final publication [4]. This transparent, collaborative process ensures broad consensus and technical accuracy. The final version was published as IUPAC Recommendations in Pure and Applied Chemistry on November 2, 2020 [10], and appeared in print in January 2021 [11].

Table: Key Metadata for the IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Publication Status | IUPAC Recommendations 2020 |

| Journal | Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| Print Publication Date | January 2021 |

| Online Publication Date | November 2020 |

| Volume and Issue | Volume 92, Issue 11 |

| Page Range | 1781-1860 |

| Corresponding Author | D. Brynn Hibbert |

Technical Framework and Methodological Coverage

Core Analytical Concepts Defined

The glossary provides precise definitions for fundamental concepts in surface chemical analysis, establishing a technical framework that supports methodological development and application. These definitions cover instrumental components, analytical parameters, data interpretation concepts, and measurement phenomena specific to surface analysis techniques. By standardizing these core concepts, the glossary enables more precise communication of methodological details in scientific publications and facilitates more accurate comparison of results obtained using different instrumental configurations or across different laboratories.

Methodological Classification System

The classification system employed in the glossary allows researchers to understand relationships between different surface analysis techniques based on their fundamental operational principles. This includes categorization by the type of incident probe (electrons, ions, or photons), the detected signals (electrons, ions, or photons), and the specific physical or chemical phenomena exploited for analysis. This systematic classification assists researchers in selecting appropriate analytical strategies for specific material characterization challenges and promotes understanding of the complementary information available from different surface analysis methods.

Essential Reference Materials for Surface Analysis

Table: Key Reference Resources for Surface Chemical Analysis Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Terminology | IUPAC Surface Analysis Glossary, ISO 18115 | Ensure consistent terminology and definitions |

| Methodology Standards | ISO/TC 201 Standards系列 | Standardized measurement procedures |

| Data Management | IUPAC FAIRSpec Guidelines | Spectroscopic data curation and management |

| Complementary Techniques | IUPAC Gold Book, Multilingual Polymer Glossary | Broader chemical terminology context |

The Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis represents an essential authoritative resource that establishes a standardized vocabulary for the surface analysis community. Its carefully defined scope encompasses the principal spectroscopic techniques used for chemical characterization of the outermost surface regions of materials, while explicitly excluding methods focused purely on structural or morphological information. Through its coordinated development with ISO standards and implementation of IUPAC's rigorous review process, the glossary provides precise definitions that support reproducibility, consistency, and clear communication in surface analysis research. For drug development professionals and other researchers working with surface characterization techniques, this glossary serves as a critical reference that enhances methodological rigor and facilitates more effective cross-disciplinary collaboration in surface science applications.

The Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis represents a formal vocabulary established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) to standardize terminology across this specialized scientific domain. This glossary serves an essential function for researchers, technicians, and students who utilize surface chemical analysis techniques but may not possess specialized expertise in surface chemistry or spectroscopy. By providing clear, authoritative definitions, the glossary facilitates more precise communication and interpretation of data across disciplines and international boundaries. The provisional recommendations for this glossary were made available for public review on 18 December 2019, with the final version published after the review period concluded on 30 April 2020 [4] [10].

The development of this glossary falls within IUPAC's broader mission to establish standardized nomenclature and terminology in chemistry, as exemplified by its series of "Color Books" that serve as authoritative resources for chemical nomenclature, terminology, and symbols [12]. These include the well-known Gold Book (Chemical Terminology), Green Book (Quantities, Units, and Symbols in Physical Chemistry), Blue Book (Organic Chemistry Nomenclature), Red Book (Inorganic Chemistry Nomenclature), Purple Book (Polymer Terminology and Nomenclature), Orange Book (Analytical Terminology), Silver Book (Clinical Laboratory Sciences), and White Book (Biochemical Nomenclature) [13]. The Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary extends this standardized approach to the specific methodological and conceptual framework of surface analysis techniques.

Methodological Framework for Glossary Development

IUPAC Provisional Recommendation Process

The development of the Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis followed IUPAC's established procedural framework for terminology standardization. This process begins with the formation of an international committee of experts in the relevant sub-disciplines of chemistry. These experts draft definitions and recommendations that are then published as Provisional Recommendations, making them widely available to the global scientific community for comment and review [4]. This open review process, which for this glossary lasted from 18 December 2019 to 30 April 2020, allows interested parties from academia, industry, and research institutions to provide feedback, ensuring the resulting definitions reflect broad consensus and practical utility [4] [10].

The provisional status of these recommendations signifies they are drafts of IUPAC recommendations on terminology, nomenclature, and symbols before final revision and publication in IUPAC's official journal, Pure and Applied Chemistry. This iterative, collaborative approach to terminology development helps establish what IUPAC's FAIR Chemistry Cookbook describes as a "formal vocabulary of terms for concepts in surface analysis" [14]. The process ensures that the final published glossary represents the most current understanding of methods and terms while maintaining consistency with established chemical nomenclature principles across IUPAC's color book series.

Editorial and Review Methodology

The editorial process for the glossary was overseen by Corresponding Author D. Brynn Hibbert, who coordinated the receipt and integration of feedback from the global scientific community [4] [10]. Following the public review period, comments were systematically evaluated and incorporated where appropriate before the final recommendations were ratified by IUPAC's Interdivisional Committee on Terminology, Nomenclature and Symbols (ICTNS). This rigorous methodology ensures that the published definitions maintain the highest standards of scientific accuracy and practical utility for the intended audience of both specialists and non-specialists who need to interpret surface chemical analysis results [4].

The glossary's development aligns with IUPAC's broader framework for FAIR Data Management (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), which emphasizes the importance of standardized terminology for effective data sharing and reuse in chemistry [14]. This is particularly relevant for surface analysis data, where consistent terminology enables proper data curation - "the process of maintaining, preserving and adding value to data throughout its lifecycle" [14]. The formal definitions facilitate the creation of meaningful metadata (data about data) that document digital objects for discovery, description, and contextualization [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Glossary Structure and Content

Taxonomic Organization of Method Categories

Table 1: Primary Method Categories in Surface Chemical Analysis

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Core Physical Principles | Key Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Spectroscopy | XPS, AES, EELS | Electron emission/absorption | Kinetic energy, binding energy, intensity |

| Ion Spectroscopy | SIMS, ISS, RBS | Ion scattering/sputtering | Mass/charge ratio, scattering angle, energy loss |

| Photon Spectroscopy | XPS, UPS, IRAS | Photon absorption/emission | Wavelength, intensity, absorption frequency |

The glossary organizes surface analysis methods into three primary spectroscopic categories based on the probe particle or radiation used: electron spectroscopy, ion spectroscopy, and photon spectroscopy [4]. This taxonomic structure reflects the fundamental physical principles underlying each technique and creates a logical framework for understanding their respective applications, strengths, and limitations. Electron spectroscopy methods, such as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), focus on the energy distribution of electrons emitted from a surface following excitation. Ion spectroscopy techniques, including Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) and Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS), utilize ion beams to probe surface composition through scattering or sputtering processes. Photon spectroscopy methods employ electromagnetic radiation to investigate surface properties through absorption, emission, or photoelectron processes.

Each methodological category contains specific techniques with defined acronyms and standardized nomenclature. The glossary provides explicit definitions for these acronyms and techniques, establishing a consistent vocabulary that enables precise communication among researchers. For example, within electron spectroscopy, the glossary distinguishes between techniques based on their excitation mechanisms and detected particles, creating clear conceptual boundaries between related methods. This systematic categorization allows researchers to quickly identify techniques relevant to their specific analytical needs while understanding the fundamental principles that govern each method's application to surface characterization.

Term Classification and Definition Structure

Table 2: Classification of Definition Types in the Glossary

| Term Category | Definition Characteristics | Examples | Relationship to Broader Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument-Based Terms | Specific to analytical equipment | Detector types, source specifications | Linked to methodological categories |

| Theoretical Concepts | Fundamental physical principles | Mean free path, inelastic scattering | Connected to multiple techniques |

| Data Analysis Terms | Pertaining to interpretation | Quantitative analysis, peak fitting | Applied across methodological boundaries |

| Procedural Terms | Related to sample preparation/handling | Sputter cleaning, ultra-high vacuum | Cross-cutting practical concerns |

The glossary employs a structured approach to term definitions that addresses the diverse needs of its target audience. Each entry provides a concise explanation of the concept while establishing its relationship to broader principles in surface analysis. The definition structure typically includes: the fundamental principle underlying the term, its specific application in surface analysis, relationships to other terms or techniques, and in some cases, mathematical formalisms or quantitative parameters where appropriate. This consistent definitional framework enables users to quickly grasp unfamiliar concepts while understanding their practical significance in surface analysis methodology.

The terminology encompasses several distinct categories of terms, including instrument-based terms specific to analytical equipment, theoretical concepts describing fundamental physical principles, data analysis terms pertaining to interpretation methods, and procedural terms related to sample preparation and handling. This comprehensive coverage ensures researchers have access to standardized terminology across the entire workflow of surface analysis, from experimental design through data interpretation. The glossary particularly emphasizes terms that have specific meanings within surface analysis that may differ from their general usage in other chemistry subdisciplines, thereby reducing potential confusion among non-specialists who need to interpret surface analysis results.

Visualization of Glossary Structure and Relationships

Conceptual Organization of the Glossary

The following diagram illustrates the systematic organization and relationships between key components of the IUPAC Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis:

This conceptual map demonstrates how the Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary integrates within IUPAC's broader ecosystem of standardized terminology while maintaining its specialized focus on surface analysis methods and associated terms. The diagram highlights the relationships between fundamental IUPAC frameworks, the specific glossary development process, and the resulting taxonomic structure of the glossary content.

Essential Research Toolkit for Surface Analysis Terminology

Table 3: Essential IUPAC Resources for Surface Chemical Analysis Terminology

| Resource Name | Resource Type | Primary Focus | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glossary of Methods and Terms in Surface Chemical Analysis | Technical Glossary | Surface analysis methods and terminology | Published in Pure and Applied Chemistry [10] |

| Gold Book (Compendium of Chemical Terminology) | Reference Work | General chemical terminology | Print and online versions available [13] |

| Orange Book (Compendium of Analytical Nomenclature) | Reference Work | Analytical chemistry terminology | Third edition (1998) available online [13] |

| IUPAC FAIR Chemistry Cookbook | Digital Resource | FAIR data management in chemistry | Online glossary of FAIR terminology [14] |

| Green Book (Quantities, Units, and Symbols) | Reference Work | Physical chemistry quantities and units | Third edition (2007) [13] |

The research toolkit for surface analysis terminology centers around IUPAC's authoritative publications, with the Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis serving as the specialized foundation. This is complemented by IUPAC's broader color book series, which provides context and connecting terminology across chemical subdisciplines. The Gold Book offers comprehensive definitions of general chemical terms that may intersect with surface analysis concepts, while the Orange Book provides specific nomenclature for analytical chemistry that supports and extends the specialized terminology in the surface analysis glossary [13]. These resources collectively establish a hierarchical terminology structure that maintains consistency across levels of specialization.

Contemporary digital resources have become increasingly important for terminology research, with the IUPAC FAIR Chemistry Cookbook representing an evolving online resource that addresses modern data management concerns, including standardized terminology for digital objects, metadata schemas, and persistent identifiers [14]. This digital resource complements the traditional print publications by addressing how standardized terminology facilitates the implementation of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles for chemical data, particularly relevant for surface analysis datasets that may be shared across research groups or deposited in public repositories. The integration of traditional terminology resources with these emerging digital standards creates a comprehensive toolkit for researchers working with surface analysis methodology and data.

Implementation and Application Framework

The practical application of surface analysis terminology requires understanding both the formal definitions and their implementation in experimental design, data collection, and scholarly communication. The glossary serves as a critical resource for writing research proposals, methods sections in publications, and technical reports where precise description of surface analysis techniques is essential. By providing standardized definitions, the glossary helps ensure that terms such as "detection limit," "lateral resolution," and "quantitative analysis" are consistently applied and understood across the scientific community, reducing ambiguity in technical communications.

For researchers implementing surface analysis techniques, the glossary provides the terminology necessary for accurate data management - "the overall activity of organizing, maintaining, and cataloging data assets" [14]. This includes standardized terms for describing instrumental parameters, sample preparation methods, and data processing techniques that should be documented as part of effective data curation. The definitions also support the creation of comprehensive metadata - "data that contains descriptive, contextual and provenance assertions about the properties of a Digital Object" [14] - for surface analysis datasets, facilitating their discovery, interpretation, and reuse by other researchers. This standardized terminology framework is particularly valuable for creating data management plans that describe how surface analysis data will be handled during and after research projects.

The Critical Link Between Standardized Terminology and Scientific Reproducibility

The reproducibility of scientific findings is a cornerstone of the scientific method, yet numerous fields currently face a "reproducibility crisis" where results from one laboratory cannot be reliably replicated by another. While contributing factors are multifaceted, a critical and often overlooked component is the inconsistent use of scientific terminology. In the specialized domain of surface chemical analysis, where techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) provide essential material characterization, the lack of standardized definitions for methods and terms can lead to ambiguous reporting, misinterpretation of data, and ultimately, irreproducible results.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) addresses this challenge through the provision of formal glossaries. The "Glossary of Methods and Terms used in Surface Chemical Analysis" provides a formal vocabulary for concepts in surface analysis, offering clear definitions for those who utilize surface chemical analysis but are not themselves surface chemists or surface spectroscopists [4] [15]. This standardization is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental prerequisite for ensuring that data and methodologies are communicated with the precision necessary for independent verification. The IUPAC Recommendations, which align with the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) standards like ISO 18115, aim to ensure universality of terminology within the field, which is key to assuring reproducibility and consistency in results [15] [10]. This technical guide explores the intrinsic connection between standardized terminology and scientific reproducibility, using the IUPAC surface chemical analysis glossary as a foundational framework.

The Role of Standardized Terminology in the Research Workflow

The integration of standardized terminology is not a single event but a process that permeates the entire research lifecycle. The following workflow diagram illustrates how formal vocabularies, like the IUPAC glossary, create a framework for reproducible science at every stage, from initial study design to final publication and knowledge transfer.

As depicted, standardized terminology acts as a connecting thread that ensures clarity and consistency at each stage. For instance, during data collection and instrument operation, precise definitions of terms such as "analysis area" and "information depth" prevent misinterpretation of instrumental parameters that could drastically alter experimental outcomes [15]. During data analysis and interpretation, a shared understanding of concepts like "binding energy referencing" is critical for the correct processing of spectral data and for meaningful comparisons between datasets generated in different laboratories [4].

Quantitative Impact: How Terminology Affects Reproducibility and Outcomes

The consequences of inconsistent terminology are not merely theoretical; they have measurable effects on research integrity and efficiency. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from various scientific domains that highlight the critical role of standardized language.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Terminology Standardization Impact

| Domain / Study | Finding | Impact of Standardization |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Chemical Analysis (IUPAC) | Provision of a formal vocabulary for methods and terms [4] [15]. | Ensures universality of terminology, which is a key to assuring reproducibility and consistency in results [15]. |

| Nursing Informatics (Secondary Analysis, 2025) | Gordon’s Eleven Functional Health Patterns was the most frequently used assessment framework [16]. | Standardized documentation practices strengthen professional visibility, support quality improvement, and enhance outcome measurement [16]. |

| General Research Methods | Confidence limits are expressed in a "plus or minus" fashion according to sample size and corrected with standardized formulas [17]. | Allows for accurate determination of the range within which a population value is likely to fall, enabling valid comparison and replication of studies [17]. |

| Drug Discovery & LLMs | Two paradigms exist: specialized models (trained on scientific language) and general-purpose models [18]. | A clear, standardized taxonomy for model types is essential for interpreting capabilities and applicability, preventing misapplication in critical tasks like drug toxicity prediction [18]. |

The data from healthcare is particularly telling. A 2025 secondary analysis of 53 studies on Standardized Nursing Terminologies (SNTs) found that while the use of structured frameworks like Gordon’s Eleven Functional Health Patterns is common, details regarding assessment tools and their integration into Electronic Health Records (EHRs) are inconsistently reported [16]. This lack of consistent documentation directly impedes the ability to replicate care protocols and reliably measure patient outcomes across different clinical settings. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that inter-rater reliability—the agreement among different nurses making the same diagnosis—was reported in only a limited number of studies and with considerable variation, underscoring a fundamental challenge in reproducing clinical judgments [16].

Case Study: Implementing Terminology Standards in Surface Chemical Analysis

Experimental Protocol for Reproducible Surface Analysis

To illustrate the practical application of standardized terminology, consider a typical experiment: determining the elemental surface composition of a solid catalyst material using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). The following protocol is structured using defined terms from the IUPAC glossary.

1. Sample Preparation and Mounting:

- Clean the analysis area (the region from which signals are acquired) using a solvent specified in the protocol, such as isopropanol [15].

- Mount the sample on a standard specimen stub using a double-sided adhesive tab or conductive tape, documenting the exact material used.

- If the sample is non-conductive, state whether charge neutralization was employed, using a flood gun of specified current and energy.

2. Instrument Calibration and Setup:

- Calibrate the binding energy scale of the spectrometer using the peak position of a standard, such as Au 4f~7/2~ at 84.0 eV or Cu 2p~3/2~ at 932.67 eV. The specific standard and its measured value must be reported [15].

- Report key instrumental parameters using standardized terms:

- Source of X-rays: e.g., Al Kα, Mg Kα (including the linewidth and energy).

- Analysis area: diameter or dimensions.

- Pass energy and step size for high-resolution spectra.

- Take-off angle (the angle between the surface plane and the direction to the analyzer entrance), as this influences the surface sensitivity.

3. Data Acquisition:

- Acquire survey spectra over a wide binding energy range (e.g., 0-1200 eV) to identify all elements present.

- Acquire high-resolution spectra for each identified element.

- For each spectrum, the number of scans and dwell time per data point should be recorded to fully document the signal-to-noise ratio.

4. Data Analysis and Reporting:

- Process the data using standardized procedures:

- Perform a linear or Shirley background subtraction for the high-resolution spectra [15].

- Fit the peaks using a consistent line shape (e.g., a mix of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions, with the ratio documented).

- Identify chemical states by comparing the measured binding energy with values from standard databases, citing the database used.

- Calculate atomic concentrations using relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) provided by the instrument manufacturer or from a cited, peer-reviewed source.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Reproducible Surface Analysis

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Chemical Analysis

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| IUPAC Glossary of Surface Chemical Analysis | Provides the formal vocabulary for writing unambiguous protocols and reports, ensuring all terms (e.g., "analysis area," "take-off angle") are consistently interpreted [4] [15]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Samples with a certified composition, used for instrument calibration and validation. Essential for verifying the accuracy of measurements and enabling cross-lab comparison. |

| Standard Spectra Databases | Collections of reference spectra (e.g., for XPS) from pure elements and well-characterized compounds. Critical for accurate peak identification and chemical state analysis. |

| Charge Neutralization Flood Gun | A source of low-energy electrons or ions used to neutralize positive charge buildup on insulating samples during analysis, preventing shifts in spectral data. |

| Ultra-High Purity Solvents | Solvents (e.g., isopropanol, methanol) used for sample cleaning to avoid contamination of the surface being analyzed. The purity grade and supplier should be specified. |

Beyond Chemistry: The Expanding Need for Terminology Standards

The imperative for standardized terminology extends far beyond surface chemistry. In emerging fields like artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug discovery, the lack of universal definitions can significantly hamper progress and reproducibility.

In the application of Large Language Models (LLMs) to drug discovery, researchers categorize models into distinct paradigms: specialized language models (trained on domain-specific data like molecular SMILES strings) and general-purpose language models (trained on broad textual data) [18]. A clear, standardized taxonomy for these model types, their architectures, and their training data is essential for other researchers to accurately interpret results, select appropriate models for their work, and, most importantly, replicate published findings. Without this, studies claiming to use an "LLM for target identification" may be referring to fundamentally different tools and methodologies, making independent verification impossible. This field also grapples with the need for standardized terminology to describe the maturity of LLM applications, using a scale from "Nascent" (in silico only) to "Matured" (deployed in operational pipelines) to clearly communicate the developmental stage of a new method [18].

The link between standardized terminology and scientific reproducibility is both critical and undeniable. As demonstrated through the IUPAC glossary for surface chemical analysis and analogous efforts in other fields, a common, precise vocabulary is the bedrock upon which reliable methods, transparent reporting, and successful replication are built. It is the conduit that allows knowledge to be accurately transferred from one researcher to another, across institutional and international boundaries.

Future efforts must focus on the dynamic maintenance of these standards to keep pace with technological innovation, the wider adoption of standardized terminologies in journal data reporting policies, and the development of interoperable glossaries that bridge related scientific disciplines. For the individual researcher, consistently using and championing standardized terminology is not just a matter of good practice—it is an active contribution to the integrity, efficiency, and collective advancement of science.

Core Techniques and Terms in Modern Surface Chemical Analysis

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the principal analytical methods used for surface chemical analysis, framed within the context of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommendations for terminology and methodology. Surface chemical analysis encompasses techniques in which beams of electrons, ions, or photons are incident on a material surface, with scattered or emitted particles spectroscopically analyzed from within approximately 10 nanometers of the surface [19]. The IUPAC glossary establishes a formal vocabulary for concepts in surface analysis, providing clear definitions to ensure terminology universality, reproducibility, and consistency in results across scientific disciplines [10] [19]. This standardization is particularly crucial for researchers in pharmaceutical development and materials science who rely on these analytical methods for characterizing material composition, electronic structure, and surface properties.

The field has advanced significantly since the initial IUPAC recommendations, with modern techniques now capable of analyzing surfaces under vacuum as well as surfaces immersed in liquid environments [19]. This guide systematically examines the core methodologies based on their excitation sources—electrons, ions, and photons—and their applications in research and industrial settings, with particular attention to the standardized terminology established by IUPAC and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) [19].

Core Principles of Surface Spectroscopy

Surface spectroscopy techniques share common fundamental principles based on the interaction of incident probes (electrons, ions, or photons) with matter. When these primary excitations strike a material surface, they transfer energy to the atoms, leading to the emission of secondary particles that carry characteristic information about the surface composition, chemical state, and electronic structure.

The information depth—typically defined as the maximum depth from which emitted particles can escape without significant energy loss—varies by technique but is generally limited to the top 1-10 nanometers for electron spectroscopy methods [20]. This extreme surface sensitivity necessitates specialized experimental conditions, particularly ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environments, to maintain surface cleanliness and prevent contamination during analysis [21].

The analytical capabilities of these methods are governed by multiple parameters including lateral resolution (the ability to distinguish features spatially), detection limits (minimum detectable concentration), and whether the technique provides elemental, chemical state, or molecular information. Each method represents a compromise between these factors, with the choice of technique dependent on the specific analytical requirements.

Electron Spectroscopy Techniques

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

3.1.1 Principles and Methodology

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), operates on the photoelectric effect where X-ray photons irradiate a material, causing the ejection of core electrons [22]. The kinetic energy of these emitted photoelectrons is measured and related to their binding energy through the equation:

[ Ek = h\nu - Eb - \phi ]

where (Ek) is the measured kinetic energy of the photoelectron, (h\nu) is the energy of the incident X-ray photon, (Eb) is the binding energy of the electron, and (\phi) is the work function of the spectrometer [21]. Each element produces a characteristic set of photoelectron peaks at specific binding energies, allowing for elemental identification, while chemical state information is derived from subtle shifts in these binding energies due to the local chemical environment [22].

3.1.2 Experimental Protocol

A standard XPS experiment requires specific instrumentation and conditions:

- Radiation Source: Typically employs magnesium (Mg Kα = 1253.6 eV) or aluminum (Al Kα = 1486.6 eV) anodes, with monochromatic sources providing higher energy resolution [21]. Synchrotron radiation offers tunable photon energies and higher brightness.

- Analyzer: An electrostatic electron energy analyzer measures the kinetic energy of emitted photoelectrons. Deflection analyzers provide resolving power ((E/\delta{E})) greater than 1,000 [21].

- Vacuum System: Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (typically 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹⁰ mbar) are essential to minimize surface contamination and allow photoelectrons to reach the detector without scattering [21].

- Sample Preparation: Samples must be compatible with UHV conditions and are typically mounted on conductive holders. Insulating samples may require charge neutralization systems.

- Data Collection: Survey scans identify all elements present, while high-resolution regional scans provide detailed chemical state information. The "magic angle" (54.7°) between incident X-rays and detected photoelectrons eliminates angular anisotropy effects [23].

3.1.3 Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative XPS analysis employs relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) to convert peak areas to atomic concentrations. The intensity for an element A is given by:

[ IA = k \cdot \sigmaA \cdot \lambdaA \cdot T \cdot nA ]

where (k) is an instrument factor, (\sigmaA) is the photoionization cross-section, (\lambdaA) is the inelastic mean free path, (T) is the analyzer transmission function, and (n_A) is the atomic concentration [23]. Using Scofield's ionization cross-sections and proper inelastic mean free path calculations, quantitative accuracy of ±30% can be achieved [23] [20].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

3.2.1 Principles and Methodology

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) utilizes a focused electron beam (typically 3-20 keV) to eject core electrons from surface atoms [23]. The resulting excited ion decays through a radiationless process where an electron from a higher energy level fills the core hole, transferring energy to a third electron (the Auger electron) that is emitted from the atom. The kinetic energy of the Auger electron is characteristic of the element and largely independent of the incident beam energy, making AES a powerful elemental analysis technique [23].

3.2.2 Experimental Protocol

- Primary Excitation: A focused electron beam (typically 1-10 nm diameter for scanning Auger microscopy) with energies between 3-20 keV [20].

- Analyzer: Cylindrical mirror analyzers (CMAs) or hemispherical sector analyzers (HSAs) measure Auger electron energies. Electron optics are often used to decelerate electrons before analysis to improve resolution [21].

- Detection Modes: Direct spectrum mode (N(E) vs E) provides the highest quantitative accuracy, while differential mode (dN(E)/dE vs E) enhances signal-to-noise for elemental identification [23].

- Spatial Resolution: Can achieve approximately 200 Å (20 nm) lateral resolution, making it suitable for microanalysis and mapping of heterogeneous surfaces [20].

3.2.3 Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative AES analysis requires careful background removal and normalization. The Auger electron yield for element A is calculated as:

[ IA^{\infty} = NA \sumi QA(E{AXi}) n{AXi} \sigma{AXi} \lambdaA(E{AXi}) [1 + r{m,A}(E0,E{AX_i},\alpha)] ]

where (NA) is the atomic density, (QA) is the fraction of ionizations in shell Xᵢ leading to Auger electrons, (n{AXi}) is the number of electrons in the subshell, (\sigma{AXi}) is the ionization cross-section, (\lambdaA) is the inelastic mean free path, and (r{m,A}) is the backscattering factor [23]. The Casnati et al. ionization cross-section and inelastic mean free path calculations for electrons with binding energies of 14 eV or less provide the best correlation with experimental databases [23].

Ion Spectroscopy Techniques

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS)

4.1.1 Principles and Methodology

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) uses a focused primary ion beam (typically 0.5-30 keV) to sputter atoms and molecules from the outermost surface of a sample. A fraction of these sputtered particles are ionized (secondary ions) and are subsequently analyzed by mass spectrometry [20]. SIMS operates in two primary modes: dynamic SIMS, which uses high primary ion currents for depth profiling, and static SIMS (including Time-of-Flight SIMS or TOF-SIMS), which uses low primary ion doses to preserve molecular information from the uppermost monolayer [20].

4.1.2 Experimental Protocol

- Primary Ion Sources: Liquid metal ion guns (LMIG) using Ga⁺, Au⁺, or Biₙ⁺ clusters for high spatial resolution; O₂⁺ or Cs⁺ for enhanced negative or positive secondary ion yields, respectively.

- Mass Analyzers: Magnetic sector instruments offer high transmission and mass resolution for dynamic SIMS; time-of-flight (TOF) analyzers provide high mass resolution and parallel detection for static SIMS.

- Detection Limits: SIMS offers exceptional sensitivity with detection limits in the parts-per-million (dynamic SIMS) to parts-per-billion (TOF-SIMS) range [20].

- Depth Profiling: Dynamic SIMS can perform depth profiling by continuously sputtering the surface and analyzing the emerging secondary ions, allowing compositional analysis as a function of depth.

Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS)

4.2.1 Principles and Methodology

Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) separates ions based on their size-to-charge ratio as they drift through a buffer gas under the influence of an electric field [24]. The collision cross section (CCS), which is related to the ion's mobility, provides structural information about the analyte. The mobility (K) is given by:

[ K = \frac{3q}{16N} \left( \frac{1}{M} + \frac{1}{m} \right)^{0.5} \left( \frac{2\pi}{kB T} \right)^{0.5} \frac{1}{\Omega{TM}} ]

where (q) is the charge, (N) is the buffer gas number density, (M) and (m) are the masses of the drift gas and analyte, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, and (\Omega{TM}) is the collision cross section calculated using the Trajectory Method [24].

4.2.2 Experimental Protocol

- Drift Tube: Typically 5-15 cm in length with uniform electric field (200-500 V/cm).

- Ionization Source: Electron impact, corona discharge, or photoionization sources create reactant ions that subsequently ionize analyte molecules through chemical ionization processes.

- Drift Gas: Purified air or nitrogen at atmospheric pressure.

- Detection: Faraday cup or electron multiplier detectors measure separated ion currents.

- Computational Support: Molecular structures optimized using density functional theory (DFT) with B3LYP functional and 6-311+G(d) basis set, with collision cross sections calculated using MOBCAL software [24].

Photon Spectroscopy Techniques

Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS)

5.1.1 Principles and Methodology

Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) uses ultraviolet radiation (typically He I at 21.2 eV or He II at 40.8 eV) to probe the valence electronic structure of materials [21] [22]. Unlike XPS, which investigates core electrons, UPS specifically examines electrons involved in chemical bonding, providing information about the density of states, work functions, and molecular orbitals [22].

5.1.2 Experimental Protocol

- Radiation Source: Gas discharge lamps (typically helium) producing resonance lines at 21.2 eV (He I) or 40.8 eV (He II) [21].

- Analyzer: Hemispherical electron energy analyzer with energy resolution typically 10-50 meV for valence band studies.

- Sample Considerations: Requires exceptionally clean surfaces and UHV conditions. Particularly sensitive to surface contamination due to the low kinetic energy of valence photoelectrons.

- Applications: Originally developed for gas-phase molecular studies; now extensively used for solid-state materials including organic semiconductors, catalysts, and electrode materials [22].

Other Photon-Based Techniques

5.2.1 X-ray Fluorescence (XRF)

XRF utilizes X-rays to excite core electrons, with the subsequent decay processes producing characteristic fluorescent X-rays that are detected and analyzed [20]. Unlike XPS, XRF probes deeper into the bulk material (micrometers rather than nanometers) and requires minimal sample preparation. It offers quantitative analysis with ±10% accuracy and detection limits reaching parts-per-billion for certain elements [20].

5.2.2 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

FTIR measures absorption of infrared radiation by molecular bonds, providing information about functional groups and molecular structure [20]. When configured for surface analysis, FTIR can probe depths of 20 Å to 1 µm, identifying organic compounds and chemical bonds with quantitative accuracy of ±5% [20].

5.2.3 Raman Microprobe

Raman spectroscopy analyzes the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light (typically a laser), providing vibrational information about molecular systems [20]. It offers excellent spatial resolution (down to 2 µm) and can probe transparent materials to depths exceeding 10 µm, making it particularly valuable for pharmaceutical analysis and carbon material characterization [20].

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Technical Specifications Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Principal Electron Spectroscopy Techniques

| Parameter | XPS/ESCA | AES | EDS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation | X-Ray | Electron | Electron |

| Detected Signal | Photoelectron | Auger Electron | X-Ray |

| Elemental Range | 3-92 | 3-92 | 6-92 |

| Lateral Resolution | 10 µm | 200 Å (20 nm) | 1 µm |

| Information Depth | 30 Å | 30 Å | 1 µm |

| Detection Limit | 1% | 1% | 0.1% |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ±30% | ±30% | ±10% |

| Chemical State ID | Yes | Some | No |

| Insulating Samples | Yes | No | Yes |

Table 2: Comparison of Principal Ion and Photon Spectroscopy Techniques

| Parameter | SIMS | TOF-SIMS | XRF | FTIR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation | Ions | Ions | X-Ray | IR Radiation |

| Detected Signal | Substrate Ions | Substrate Ions | X-Ray | IR Radiation |

| Elemental Range | 1-92 | 1-92 | 6-92 | NA |

| Lateral Resolution | 60 µm | 2000 Å (200 nm) | 1 cm | 10-100 µm |

| Information Depth | 0-10 µm | 15 Å | Bulk | 20 Å-1 µm |

| Detection Limit | ppm | ppm | ppb | ppm |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ±30% | ±100% | ±10% | ±5% |

| Molecular Information | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate surface analysis technique depends on specific analytical needs:

- Elemental Composition: XPS for surface composition with chemical state information; AES for high spatial resolution mapping; EDS for rapid elemental analysis with higher throughput.

- Chemical State Information: XPS provides detailed chemical bonding information; FTIR identifies functional groups; Raman characterizes molecular structures.

- Trace Analysis: SIMS offers the lowest detection limits (ppm to ppb); TOF-SIMS provides molecular specificity for trace organic analysis.

- Depth Profiling: AES and XPS with sputtering provide composition versus depth; dynamic SIMS offers the highest depth resolution for thin films.

- Insulating Materials: XPS, FTIR, and Raman are suitable for insulating samples; AES requires special charge compensation techniques.

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

XPS Chemical State Analysis Workflow

Diagram Title: XPS Chemical State Analysis Workflow

Surface Analysis Technique Selection Pathway

Diagram Title: Surface Analysis Technique Selection Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Spectroscopy

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Quantification Calibration | Au, Cu, Ag foils for energy scale calibration; certified stoichiometric compounds (e.g., Cu₂O, SiO₂) for relative sensitivity factors |

| Charge Neutralization Sources | Charge Compensation on Insulators | Low-energy electron flood guns (0.1-10 eV); low-energy argon ion guns; charge neutralization filaments |

| Sputter Ion Sources | Depth Profiling & Surface Cleaning | Ar⁺ gas (99.999% purity) for inert sputtering; O₂⁺ for enhanced positive secondary ion yield; Cs⁺ for enhanced negative ion yield |

| UHV-Compatible Adhesives | Sample Mounting | Conductive carbon tapes; silver paints; specially formulated UHV-compatible epoxies |

| Calibration Grids | Spatial Resolution Verification | Gold-coated diffraction gratings with certified line spacing; nickel meshes with certified dimensions |

| X-ray Anodes | XPS/XRF Excitation Sources | Magnesium (1253.6 eV); Aluminum (1486.6 eV); silver (2984.2 eV) anodes of 99.95% minimum purity |

| Gas Discharge Lamps | UPS Excitation Sources | Helium discharge lamps for He I (21.2 eV) and He II (40.8 eV) radiation; discharge gas purity 99.999% |

| Electron Gun Filaments | AES Excitation Source | Lanthanum hexaboride (LaB₆) for high brightness; tungsten filaments for extended lifetime |

The principal analytical methods of electron, ion, and photon spectroscopy provide complementary capabilities for surface chemical analysis, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The IUPAC recommendations for terminology ensure consistency and reproducibility across these techniques, facilitating accurate communication of results within the scientific community [10] [19]. As surface analysis continues to evolve, developments in time-resolved spectroscopy, improved energy resolution, and novel instrumentation such as cryo-XPS systems for volatile materials will further expand the applications of these techniques [22].

For researchers in pharmaceutical development and materials science, understanding the capabilities and limitations of each technique is essential for appropriate method selection and data interpretation. The comparative tables and workflows provided in this guide serve as a foundation for making informed decisions about surface characterization strategies, while the standardized terminology ensures alignment with international standards and recommendations.

Implementing Standard Terminology for Reliable Data and Reporting

In scientific research and development, the precise use of terminology is not merely a matter of linguistic preference but a fundamental requirement for data integrity, reproducibility, and safety. Inconsistencies in terminology can introduce significant errors in data interpretation, leading to costly mistakes in research outcomes and practical applications. This technical guide examines the critical challenges posed by terminology inconsistencies across scientific domains, with particular focus on surface chemical analysis and pharmaceutical development, and provides frameworks for mitigating associated risks.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has long recognized the essential role of standardized terminology in ensuring reproducibility and consistency in scientific results [25]. As scientific fields become increasingly interdisciplinary and data-driven, the need for unambiguous terminology has never been more pressing. The recent D-UST Conference 2025 highlighted the growing importance of ensuring scientific terminology, units, and symbols are fit for purpose in a predominantly digital and interdisciplinary research landscape [26]. This guide explores these challenges within the context of the IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary, while drawing relevant connections to pharmaceutical naming conventions and their impact on data interpretation.

The Scope of Terminology Standardization

Standardization Frameworks in Scientific Practice

Scientific terminology standardization involves establishing formally recognized vocabularies with clear definitions to ensure consistent understanding across research communities and applications. These frameworks are particularly crucial for fields where precise communication directly impacts safety, regulatory compliance, and scientific progress.

The IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary represents a comprehensive effort to provide a formal vocabulary for concepts in surface analysis, offering clear definitions for those who utilize surface chemical analysis or need to interpret results without being surface chemists or surface spectroscopists themselves [25] [10]. This glossary selectively incorporates topics from ISO 18115, which consists of two parts: General terms and terms used in spectroscopy, and Terms used in scanning probe microscopy [25]. The alignment between IUPAC and ISO standards demonstrates the critical importance of consistent terminology across international boundaries and scientific organizations.

The Digital Imperative

Contemporary scientific research increasingly operates within digital ecosystems that demand machine-readable terminology alongside human comprehension. The 2025 D-UST Conference emphasized harmonizing scientific expression across digital platforms, enhancing machine-readability, and supporting data interoperability as key enablers for FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data practices and global collaboration [26].

Samantha Pearman-Kanza's presentation at the conference encouraged the use of "modular, standards-based ontologies for scientific data exchange" [26], highlighting the evolution from traditional glossaries to structured semantic frameworks that can support computational analysis and integration across disciplines.

Terminology Inconsistencies in Surface Chemical Analysis

Evolution of Analytical Techniques

The field of surface chemical analysis has experienced significant methodological advancement since the previous version of the terminology guide (often called the "Orange Book") was published in 1997 [25]. These advancements have necessitated updated terminology to ensure universal understanding and application.

The IUPAC Recommendations 2020 for surface chemical analysis terminology specifically focus on analytical techniques in which "beams of electrons, ions, or photons are incident on a material surface and scattered or emitted electrons, ions, or photons detected from within about 10 nm of the surface are spectroscopically analysed" [25]. The glossary covers methods under vacuum as well as surfaces immersed in liquid, acknowledging the expanding methodological scope that requires precise terminological boundaries.

Critical Terminology Challenges

Surface chemical analysis faces several specific terminology challenges that can impact data interpretation:

- Methodological blurring: As techniques combine or evolve, the boundaries between traditional methodological categories become less distinct, requiring careful definitional precision.

- Cross-disciplinary applications: Researchers from different backgrounds may apply varying terms to the same analytical approaches, leading to confusion in literature interpretation.

- Instrument-specific terminology: Different manufacturers may use proprietary terms for similar instrumental parameters, complicating cross-platform comparisons.

The IUPAC Glossary addresses these challenges by providing definitions for principal methods along with notes on common variants, introducing the range of surface chemical analysis methods available, and defining terms associated with these methods [25].

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Nomenclature and Medication Errors

The Drug Naming Crisis

In pharmaceutical development and clinical practice, terminology inconsistencies present direct risks to patient safety. Medication errors commonly involve confusion between drug names that look or sound alike, accounting for between approximately 8% and 25% of all medication errors [27]. These errors may involve the wrong drug, wrong dose, wrong patient, wrong route of administration, or wrong time of delivery [27].

Drug nomenclature falls into two categories with different confounding factors:

- Proprietary (brand) names: May be intentionally similar to transfer trademark value between products

- Non-proprietary (generic) names: Often share prefixes or suffixes to indicate shared mechanism of action or chemical constituents

The problem is particularly acute for combination medicinal products, which do not fall under the conventional International Non-proprietary Name (INN) system managed by the World Health Organization [28]. Researchers have identified 26 combination formulations historically named with the "co-drug" format in the United Kingdom alone, with 11 of these prescribed more than 2000 times in the past year [28]. This high prescription volume amplifies the potential risk from naming confusion.

Quantitative Assessment of Drug Name Confusion

Table 1: Drug Name Confusion Errors and Risk Mitigation Strategies

| Error Category | Representative Examples | Error Rate Impact | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look-alike drug names | Dobutamine/Dopamine | 8-25% of all medication errors [27] | Tall Man lettering (e.g., DOBUTamine/DOPamine) |

| Sound-alike drug names | Clomiphene/Clomipramine | Substitutions common [27] | Phonetic differentiation strategies |

| Combination drug nomenclature | co-codamol, co-amoxiclav, co-trimoxazole | 11+ products prescribed >2000 times annually [28] | Standard INN component + dose format (x+y) |

| Abbreviation confusion | IU (International Unit)/IV (intravenous) | Illegibility in handwritten orders [27] | Avoid dangerous abbreviations |

Experimental Evidence for Nomenclature Solutions

Tall Man Lettering Protocol

Research has empirically evaluated strategies for reducing drug name confusion, particularly the use of Tall Man lettering. The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Stimuli development: Creation of mock drug packs with information limited to generic name, dosage form, and strength in sans serif fonts (e.g., Arial)

- Experimental design: Participants search for a target product among an array of product packs where the target pack may be replaced by a similar distractor

- Eye movement monitoring: Using eye-tracking equipment to record fixations (point-of-regard when looking at a stationary target) and saccades (rapid eye movements between fixations)

- Data analysis: Reduction of raw eye position data to fixation points using analysis software (e.g., ASL EYENAL), with fixations defined as mean X and Y eye position coordinates over a minimum period of 100ms [27]

Experimental Findings

Eye-tracking experiments demonstrate that participants make fewer medication selection errors when Tall Man letters are implemented [27]. The eye movement data directly corresponds with error rates: in conditions where participants make more errors, they also make more fixations and spend longer fixating relevant portions of the array [27]. This objective physiological evidence strongly supports the effectiveness of visual differentiation strategies in reducing confusion between similar drug names.

Broader Impacts on Scientific and Industrial Practice

Consequences in Analytical Chemistry

Beyond pharmaceutical nomenclature, terminology inconsistencies introduce significant risks in analytical chemistry testing laboratories. These risks can be categorized into two primary groups:

- Risks from human errors in test performance: Resulting from misunderstandings or inconsistent application of methodological terminology

- Risks from erroneous interpretation of test results: Due to measurement uncertainty combined with terminology ambiguity when judging results against specification limits [29]

Advanced methods for assessing risks of false decisions in analytical chemistry laboratories have emerged as a critical research focus, with multivariate Bayesian approaches being applied for risk modeling and evaluation [29]. These methodological frameworks acknowledge that terminology inconsistency represents a fundamental variable in analytical quality control.

Implications for Research Reproducibility

Inconsistencies in scientific terminology directly threaten the reproducibility crisis across multiple disciplines. The D-UST Conference 2025 highlighted how frameworks like the Crystallographic Information Framework (CIF) have supported reproducibility and transparency through standardized terminology and data representation [26]. Simon Coles' presentation emphasized how consistent information frameworks enable research verification and reuse across institutional boundaries.

Mitigation Strategies and Standardization Solutions

Institutional Frameworks and Guidelines

Multiple international organizations have established frameworks to address terminology inconsistencies:

- World Health Organization INN Program: Established in the 1970s to select unambiguous names for single-drug products [28]

- IUPAC Terminology Recommendations: Provide domain-specific glossaries like the Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary to ensure universality of terminology [25]

- ISO Standards: International standards such as ISO 18115 for surface chemical analysis vocabulary create binding terminology frameworks [25]

- FDA Name Differentiation Project: Implemented in 2001 to encourage voluntary revision of confusing drug names using Tall Man letters [27]

Proposed Nomenclature Standards for Combination Products

For combination medicinal products that fall outside conventional INN nomenclature, researchers advocate for a standard nomenclature format: "state the INN of each component followed by dose information in the x + y format" [28]. This approach would enhance clarity and safety during prescribing and administration, particularly for high-volume drugs like paracetamol + codeine (instead of co-codamol), amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (instead of co-amoxiclav), and trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole (instead of co-trimoxazole) [28].

Digital-Age Solutions

Contemporary terminology challenges require solutions designed for digital infrastructure:

- Machine-readable terminology: Development of standards that support both human comprehension and computational analysis

- Semantic web technologies: Implementation of modular, standards-based ontologies for scientific data exchange [26]

- Cross-domain interoperability: Frameworks like CODATA's Cross Domain Interoperability Framework (CDIF) to bridge terminology gaps between disciplines [26]

- Unicode standardization: Coordinated community input to ensure proper encoding of scientific symbols for digital representation [26]

Table 2: Digital-Era Terminology Solutions and Applications

| Solution Framework | Key Features | Application Context | Implementing Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine-readable terminology | Links quantitative values to defined aspects and scales [26] | Measurement data transformation | M-layer framework |

| Semantic Web ontologies | Modular, standards-based data exchange [26] | Scientific data integration | University of Southampton |

| FAIR Data standards | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable data [26] | Crystallography, materials science | IUPAC, CODATA, RSC |

| Unicode symbol representation | Consistent encoding of scientific concepts [26] | Scientific computing | Unicode Consortium with scientific input |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Terminology Standardization

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminology Standards | IUPAC Surface Chemical Analysis Glossary [25] | Formal vocabulary for surface analysis concepts | Surface chemical analysis interpretation |

| Nomenclature Systems | WHO INN Guidelines [28] | Unambiguous naming of pharmaceutical substances | Drug development and prescribing |

| Risk Assessment Tools | Multivariate Bayesian approaches [29] | Modeling risks of false decisions | Analytical chemistry testing laboratories |

| Visual Differentiation | Tall Man lettering protocols [27] | Reducing drug name confusion errors | Medication packaging and labeling |

| Digital Interoperability | CODATA CDIF Framework [26] | Cross-domain terminology alignment | Interdisciplinary research projects |