Surface States and Trap Density in Perovskite Nanocrystals: Analysis, Mitigation, and Impact on Optoelectronic Performance

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of surface states and trap densities in metal halide perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs), a critical factor determining their efficiency and stability in optoelectronic applications.

Surface States and Trap Density in Perovskite Nanocrystals: Analysis, Mitigation, and Impact on Optoelectronic Performance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of surface states and trap densities in metal halide perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs), a critical factor determining their efficiency and stability in optoelectronic applications. We explore the fundamental origins of surface defects, including halide vacancies and under-coordinated lead atoms, and their direct impact on non-radiative recombination and photoluminescence quantum yield. The review covers advanced characterization techniques like scanning photocurrent measurement systems and thermal conductance spectroscopy for mapping trap distribution. A significant focus is placed on strategic passivation methods, including ligand engineering, compositional tuning, and encapsulation, to suppress trap states. By comparing lead-based and tin-based PNCs and discussing performance validation under operational stress, this work serves as a foundational resource for researchers and scientists developing next-generation, high-performance perovskite-based devices.

Unraveling the Fundamentals: How Surface States and Trap Density Govern Perovskite Nanocrystal Behavior

Defining Surface States and Trap Densities in ABX3 Perovskite Nanocrystals

In the pursuit of high-performance perovskite optoelectronics, surface states and trap densities have emerged as the predominant factors limiting both device efficiency and long-term stability. Metal halide perovskites with the ABX3 crystal structure—where 'A' is a monovalent cation (e.g., Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺), 'B' is a divalent metal cation (e.g., Pb²⁺, Sn²⁺), and 'X' is a halide anion (e.g., I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻)—exhibit exceptional optoelectronic properties including high absorption coefficients, long carrier diffusion lengths, and tunable bandgaps [1] [2]. However, their inherently ionic nature and soft lattice structure predispose them to the formation of numerous defective surface states [3].

These surface defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, significantly reducing charge carrier lifetimes and diffusion lengths, which consequently diminishes photovoltaic performance through reduced open-circuit voltage (VOC) and fill factors [3]. In strongly confined perovskite nanocrystals (NCs), where the surface-to-volume ratio is substantially increased, the impact of these surface states becomes even more pronounced, governing the fundamental photophysical processes and ultimately determining device viability [4] [5]. This technical guide comprehensively examines the origin, characterization, and mitigation of surface states in ABX3 perovskite nanocrystals, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge and experimental protocols necessary to advance this critical research domain.

Fundamental Origins of Surface States in ABX3 Nanocrystals

Atomic-Level Defect Structures

The surface of ABX3 perovskite nanocrystals hosts a variety of defects that fundamentally differ from bulk defects due to the broken symmetry and undercoordinated ions at the crystal boundary. These defects primarily form during synthesis or post-synthetic processing due to rapid crystallization kinetics and can be categorized as follows:

- Undercoordinated Ions: Surface Pb²⁺ or Sn²⁺ cations with missing halide anions in their coordination sphere create deep trap states within the bandgap. Similarly, undercoordinated halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻) contribute to shallow trap states [3].

- Ion Vacancies: The most mobile and prevalent defects in halide perovskites are A-site (e.g., Cs⁺, FA⁺), B-site (e.g., Pb²⁺), and X-site (e.g., I⁻) vacancies. X-site vacancies (VI) are particularly common and create deep traps that facilitate non-radiative recombination [1] [6].

- Antisite Defects: Pb-I antisites, where Pb²⁺ occupies I⁻ sites and vice versa, though energetically less favorable, can form under certain synthesis conditions and generate severe recombination centers [3].

- Interstitial Defects: Halide interstitials (Xi) can form during crystal growth or under illumination, contributing to ion migration and phase segregation [1].

Impact of Nanocrystal Confinement and Composition

In strongly confined nanocrystals (diameter < Bohr radius), the quantum confinement effect not only modifies the electronic structure but also amplifies the influence of surface states due to the dramatically increased surface-to-volume ratio [5]. The composition of the perovskite lattice further determines the nature and density of these surface traps:

- B-site Cation Oxidation States: The stability of the B-site metal oxidation state (e.g., Pb²⁺/Pb⁰, Sn²⁺/Sn⁴⁺) is crucial. Reduction of Pb²⁺ to Pb⁰ or oxidation of Sn²⁺ to Sn⁴⁺ creates metallic lead or tin vacancies (VPb) and tin interstitials (Sni), respectively, significantly increasing trap-assisted recombination [6].

- A-site Cation Influence: While A-site cations do not directly contribute to the band edges, they indirectly influence surface trap formation by modulating the [BX6]⁴⁻ octahedral tilting and steric interactions. Mixed A-site cations (e.g., Cs/FA/MA) can synergistically stabilize the perovskite structure and reduce surface defect density [1].

- Halide Composition: Mixed halide perovskites (e.g., I/Br) are prone to halide segregation under illumination, creating localized surface domains with different bandgaps that act as trapping centers [1].

Table 1: Common Surface Defects in ABX3 Perovskite Nanocrystals and Their Characteristics

| Defect Type | Formation Energy | Trap Depth | Impact on Device Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | Low | Deep | Severe non-radiative recombination, reduced VOC |

| Iodide Vacancies (VΙ) | Very Low | Deep | Enhanced ion migration, hysteresis, phase segregation |

| Lead Vacancies (VPb) | Medium | Shallow | Reduced conductivity, increased recombination |

| Interstitial Iodide (Ii) | Low | Shallow | Contributes to ion migration, minimal recombination |

| Pb-I Antisites | High | Deep | Severe recombination centers, reduced all performance parameters |

Quantitative Characterization of Trap Densities

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques

Accurate quantification of trap state densities is essential for evaluating material quality and developing effective passivation strategies. The following techniques provide complementary information about trap densities and energetics:

- Thermal Admittance Spectroscopy (TAS): This method measures the capacitance response of devices as a function of frequency and temperature to extract the density and energy distribution of trap states. The trap density (Nt) can be calculated using the formula: Nt = -(Vbi·dC/dω)/(q·ε·ω·kT), where Vbi is the built-in potential, C is capacitance, ω is angular frequency, q is elementary charge, ε is permittivity, k is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature [7].

- Deep Level Transient Spectroscopy (DLTS): DLTS applies repetitive voltage pulses to devices and monitors the transient capacitance response, providing thermal activation energies and capture cross-sections for specific trap states with densities as low as 10¹⁰ cm⁻³ [7].

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): By monitoring the decay of photoluminescence after pulsed excitation, TRPL quantifies charge carrier lifetimes. The trap density can be estimated using Nt = 1/(σ·vth·τ), where σ is the capture cross-section, vth is the thermal velocity, and τ is the carrier lifetime extracted from TRPL decay [8].

- Photothermal Deflection Spectroscopy (PDS): This highly sensitive technique measures sub-bandgap absorption from trap states, providing information about the energetic distribution of defects without requiring electrical contacts [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Trap Density Characterization Techniques for Perovskite Nanocrystals

| Technique | Detection Limit (cm⁻³) | Spatial Resolution | Information Obtained | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Admittance Spectroscopy | 10¹³ - 10¹⁵ | Device-level | Trap density of states, activation energy | Requires full device fabrication |

| Deep Level Transient Spectroscopy | 10¹⁰ - 10¹³ | Device-level | Discrete trap levels, capture cross-sections | Complex interpretation, device required |

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence | 10¹⁵ - 10¹⁷ | Micron-scale | Carrier lifetime, trap-assisted recombination rate | Indirect trap quantification |

| Photothermal Deflection Spectroscopy | 10¹⁴ - 10¹⁶ | Millimeter-scale | Sub-bandgap absorption, defect energy distribution | Limited spatial resolution, bulk-sensitive |

Experimental Protocol: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence Measurement

Objective: Quantify carrier lifetime and estimate trap density in CsPbI₃ perovskite nanocrystals.

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbI₃ nanocrystal solution or film

- Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) system

- Pulsed laser source (e.g., 405 nm, 1 MHz repetition rate)

- Spectrometer with near-infrared sensitivity

- Cryostat for temperature-dependent measurements (optional)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For solution measurements, dilute nanocrystals in anhydrous hexane to optical density ~0.1 at excitation wavelength. For film measurements, spin-coat nanocrystals on clean glass substrates at 2000 rpm for 60 seconds.

- Instrument Calibration: Align the excitation laser to illuminate the sample uniformly. Set the detection monochromator to the PL peak wavelength (typically ~690 nm for CsPbI₃). Adjust the instrument response function using a scattering solution.

- Data Acquisition: Excite the sample with pulsed laser and collect PL decay traces until achieving sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (>10⁴ counts at the peak). Repeat measurements at different positions for films to assess homogeneity.

- Data Analysis: Fit the PL decay curve using a multi-exponential function: I(t) = ΣAᵢ·exp(-t/τᵢ). Calculate the amplitude-weighted average lifetime: ⟨τ⟩ = ΣAᵢτᵢ²/ΣAᵢτᵢ.

- Trap Density Estimation: Using the relationship Nt ≈ 1/(σ·vth·⟨τ⟩), with typical values σ ≈ 10⁻¹⁵ cm² for capture cross-section and vth ≈ 10⁷ cm/s for thermal velocity, calculate the approximate trap density.

Interpretation: Shorter average lifetimes (<10 ns) typically indicate high trap densities (>10¹⁶ cm⁻³), while longer lifetimes (>100 ns) suggest well-passivated surfaces with lower trap densities (<10¹⁵ cm⁻³) [8] [5].

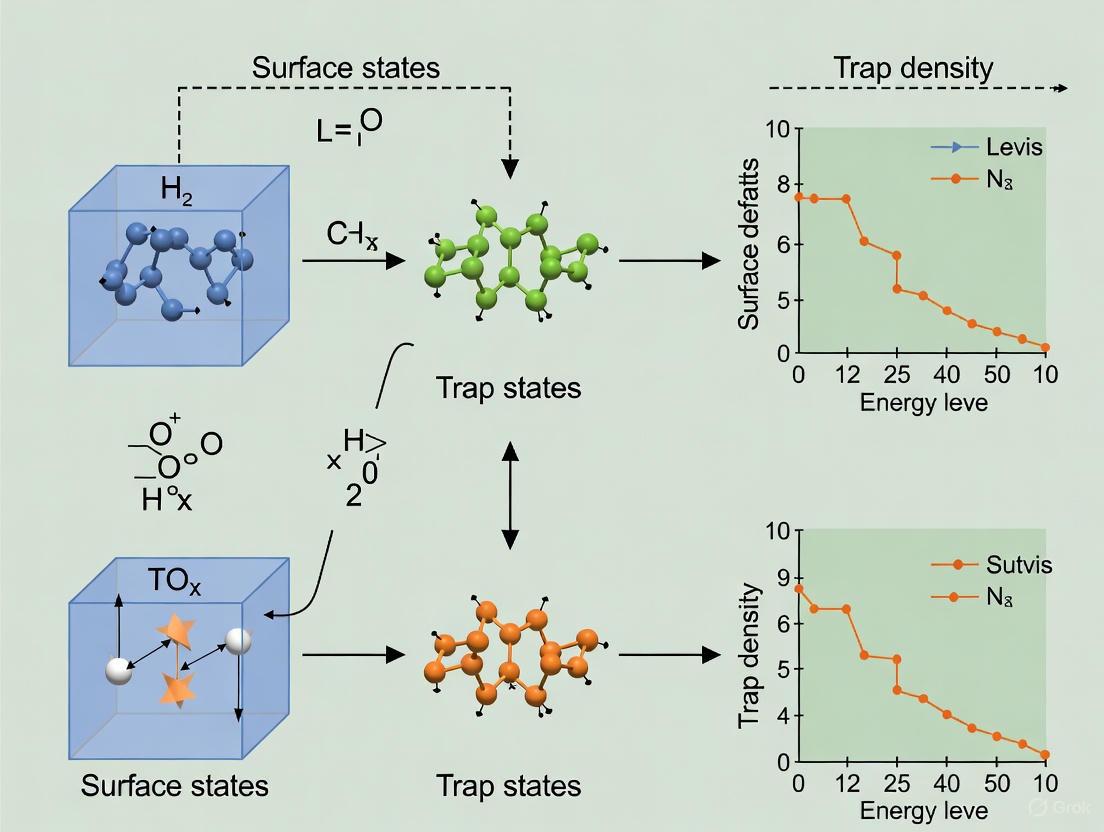

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for trap density quantification via time-resolved photoluminescence.

Mitigation Strategies: Surface Passivation and Engineering

Chemical Passivation Approaches

Surface passivation represents the most direct strategy to mitigate trap states in perovskite nanocrystals by coordinating with undercoordinated surface ions and eliminating dangling bonds:

- Lewis Acid-Base Passivation: Lewis base molecules (e.g., trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), thiophenes) donate electron density to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, while Lewis acids (e.g., metal halides) accept electrons from undercoordinated halide sites. This dual approach simultaneously addresses both cationic and anionic surface defects [3] [5].

- Halide-Rich Passivation: Introduction of excess halide anions (e.g., iodide from KI, PbI₂) during synthesis or as post-treatment fills halide vacancies and suppresses I⁻ migration. Potassium stannate (K₂SnO₃) treatment spontaneously generates KI and PbSnO₃ seeds, providing simultaneous halide passivation and templated growth [9].

- Multifunctional Molecular Passivation: Molecules containing multiple functional groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂, -SH) can passivate various defect types simultaneously. For example, polymer poly-vinylpyrrolidone (PVP) utilizes its acylamino groups to coordinate with surface ions through N and O atoms, enhancing electron cloud density and stabilizing the cubic phase of CsPbI₃ [8].

- Low-Dimensional Perovskite Capping: Formation of 2D or 1D perovskite phases on the surface of 3D nanocrystals creates a natural heterostructure that passivates surface states while enhancing environmental stability. 2D perovskites with long alkyl ammonium chains provide hydrophobic protection but may impede charge transport if too thick [3].

Crystallization Control and Seed Engineering

Prevention of defect formation during nanocrystal synthesis is more effective than post-synthetic passivation:

- Oxide-Based ABX3-Structured Seeds: In-situ formation of oxide perovskites (e.g., PbSnO₃) with high lattice matching (>98%) to the target perovskite provides templated growth, reducing nucleation barriers and promoting oriented crystallization with fewer defects [9].

- Multi-component Perovskite Formulations: Mixed A-site cations (Cs/FA/MA) and X-site halides (I/Br) create a more stable perovskite structure with increased activation energy for ion migration, effectively reducing defect formation and propagation [1].

- Size-Tunable Synthesis at Room Temperature: Recent advances enable synthesis of strongly confined doped NCs at room temperature using coordinating ligands like TOPO and lecithin, providing better control over nucleation and growth kinetics for lower defect densities [5].

Table 3: Surface Passivation Strategies for ABX3 Perovskite Nanocrystals

| Passivation Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Materials | Effect on Trap Density | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Acid-Base | Coordinate with undercoordinated surface ions | TOPO, Lecithin, Metal halides | Reduction by 50-80% | May impede charge extraction |

| Halide-Rich Treatment | Fill halide vacancies | KI, PbI₂, ZnI₂ | Reduction by 60-90% | Can introduce halide heterogeneity |

| Polymer Passivation | Multi-point coordination, surface energy modification | PVP, PMMA | Reduction by 70-85% | Potential insulating layer formation |

| Low-Dimensional Capping | Natural heterostructure, hydrophobic protection | Bulky ammonium salts (e.g., phenethylammonium) | Reduction by 75-95% | May limit charge transport |

| Oxide Seed Templating | Lattice-matched epitaxial growth | K₂SnO₃ (forms PbSnO₃) | Reduction by 80-90% | Complex synthesis optimization |

Experimental Protocol: Surface Passivation with Potassium Stannate

Objective: Implement in-situ oxide-based ABX3-structured seeding to reduce surface trap density in Sn-Pb perovskite nanocrystals.

Materials:

- Lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.99%)

- Tin iodide (SnI₂, 99.99%)

- Formamidinium iodide (FAI, 99.5%)

- Cesium iodide (CsI, 99.99%)

- Potassium stannate (K₂SnO₃, 98%)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, anhydrous)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous)

- Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, 99%)

- Lecithin (95%)

- Hexane (anhydrous)

- Centrifuge and vials

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation:

- Prepare perovskite precursor solution: Dissolve PbI₂ (1.0 M), SnI₂ (0.9 M), FAI (1.7 M), and CsI (0.3 M) in 1 mL DMF:DMSO (4:1 v/v) mixture.

- Prepare K₂SnO₃ solution: Dissolve 5 mg K₂SnO₃ in 1 mL DMSO (0.5 wt% relative to perovskite precursors).

Seed-Mediated Synthesis:

- Add 50 μL of K₂SnO₃ solution to 1 mL perovskite precursor solution under stirring.

- Allow the spontaneous reaction: K₂SnO₃ + PbI₂ → 2KI + PbSnO₃ to proceed for 10 minutes, forming PbSnO₃ seeds with ABX3 structure.

- Add TOPO (50 mg) and lecithin (10 mg) as coordinating ligands to control nanocrystal growth.

Nanocrystal Formation:

- Inject the precursor mixture into 6 mL hexane under vigorous stirring.

- Continue stirring for 5 minutes until colloidal nanocrystals form.

- Add acetone (3:1 v:v ratio) and centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes to precipitate nanocrystals.

- Redisperse in hexane and pass through a 0.2 μm syringe filter.

Characterization:

- Perform XRD to confirm phase purity and preferred orientation.

- Measure TRPL to quantify carrier lifetime improvement.

- Conduct XPS to verify surface composition and passivation.

Mechanism: The in-situ formed PbSnO₃ seeds exhibit 98% lattice matching with the target perovskite, templating oriented growth with fewer defects. Simultaneously, the KI byproduct passivates halide vacancies, reducing trap density from ~10¹⁶ cm⁻³ to ~10¹⁵ cm⁻³ [9].

Diagram 2: Mechanism of surface passivation and defect reduction via K₂SnO₃ treatment.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surface State Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Stannate (K₂SnO₃) | Oxide seed precursor, KI generator | Add 0.5-1 wt% to perovskite precursor | Enables in-situ formation of lattice-matched PbSnO₃ seeds [9] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Lewis base coordinative ligand | Add during NC synthesis (50-100 mg/mL) | Passivates undercoordinated Pb²⁺; controls NC size [5] |

| Lecithin | Zwitterionic surface ligand | Add during or post-synthesis (5-10 mg/mL) | Enhances colloidal stability; passivates multiple defect types [5] |

| Poly-Vinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Polymer passivant | Add to precursor (5-10 wt%) or spin-coat on film | Acylamino groups coordinate surface ions; stabilizes cubic phase [8] |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Halide vacancy passivator | Add to precursor (1-5 mol%) or post-treatment | Fills iodide vacancies; suppresses ion migration [9] |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | 2D perovskite former | Spin-coat on NC film (1-5 mg/mL in IPA) | Forms protective 2D layer; enhances humidity stability [3] |

The systematic definition and control of surface states in ABX3 perovskite nanocrystals represents a cornerstone for advancing perovskite optoelectronics. While significant progress has been made in understanding the atomic origins of trap states and developing effective passivation strategies, several research frontiers demand continued investigation:

First, the dynamic nature of surface states under operational stresses (light, heat, electric fields) requires more sophisticated characterization techniques that can monitor defect evolution in real-time. Second, the development of universal passivation strategies compatible with diverse perovskite compositions (Pb-based, Sn-Pb, and Pb-free alternatives) remains challenging yet essential for widespread technological adoption. Third, interface engineering in multilayer device architectures must be optimized to ensure that surface passivation translates to improved device performance and stability.

The recent emergence of oxide-based ABX3-structured seeds [9] and room-temperature synthesis approaches for strongly confined doped NCs [5] represent promising directions that circumvent traditional limitations. When combined with multimodal characterization and machine-learning-assisted materials design, these advances pave the way for perovskite nanocrystals with near-ideal surfaces, unlocking their full potential for next-generation photovoltaics, light-emitting devices, and quantum technologies.

In the pursuit of high-performance optoelectronic devices, the management of surface states and trap density is a central thesis in perovskite nanocrystal research. While lead-halide perovskites (LHPs) exhibit a degree of "defect tolerance"—meaning that certain defects do not create deep-level traps that cause severe non-radiative recombination—this tolerance is not universal [10]. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio of nanocrystals makes their optical and electronic properties exceptionally susceptible to surface defects [11] [10]. These defects, including halide vacancies, undercoordinated lead atoms (often denoted as Pb0), and specific bromine vacancies, act as trap states that quench photoluminescence, accelerate charge carrier recombination, and degrade device efficiency and stability [12] [13] [10]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the origin, characterization, and impact of these three critical defect types, framing the discussion within the broader context of controlling trap density to unlock the full potential of perovskite nanocrystals.

Core Defect Types: Origin and Impact on Material Properties

Halide Vacancies

Halide vacancies (VX) are one of the most common and significant point defects in lead-halide perovskite nanocrystals. They form when a halide ion (X = I⁻, Br⁻, Cl⁻) is missing from its lattice site, creating a local charge imbalance and undercoordinated lead ions [10].

- Formation and Role: These vacancies are native defects with relatively low formation energies. Their density can be intentionally increased through post-synthetic treatments, such as multiple purification steps using polar antisolvents like methyl acetate, which strip away surface halide ions [12]. While halide vacancies in I⁻-based perovskites (e.g., CsPbI3) are often shallow-level defects, the same vacancies in Br⁻-based or mixed-halide systems can form deeper traps [12].

- Impact on Device Performance: Halide vacancies are major contributors to ion migration, which leads to phase segregation in mixed-halide perovskites and severe voltage losses (VOC deficit) in wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells (PSCs) [14]. Furthermore, they act as non-radiative recombination centers, reducing the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and overall device efficiency [12].

Table 1: Characteristics of Halide Vacancies in Different Perovskite Compositions

| Perovskite Composition | Estimated Trap Depth (from DFT) | Key Impact on Properties | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI₃ | Shallow (0.278 eV from CBM) [12] | Minimal PLQY change with increased defect density; high defect tolerance [12] | Excitation-energy-dependent PLQY; transient absorption spectroscopy [12] |

| CsPb(Br/I)₃ | Intermediate (0.513 eV) [12] | ~15% PLQY decrease with high excitation energy in defective samples [12] | Photothermal deflection spectroscopy (PDS) shows sub-bandgap absorption [12] |

| CsPbBr₃ | Deeper (0.666 eV from CBM) [12] | Significant PLQY and lifetime reduction with purification-induced defects [12] | XPS shows decreased halide-to-Pb ratio; increased Urbach energy from PDS [12] |

Surface Pb⁰ Atoms (Undercoordinated Pb Species)

Undercoordinated lead atoms, often referred to as Pb⁰ or "surface Pb0" in the literature, are a critical surface defect originating from the non-stoichiometric, lead-rich nature of as-synthesized nanocrystals [13].

- Atomic-Level Origin: In PbS colloidal quantum dots (CQDs), which share similarities with halide perovskites in terms of surface chemistry, the (111) crystal facets are terminated with Pb atoms. Inhomogeneous distribution of atoms across surfaces leads to undercharged Pb species, which are a primary cause of deep-level traps [13]. This concept is directly transferable to lead-halide perovskite NCs, where undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the surface act as potent charge carrier traps [11] [10].

- Consequences for Optoelectronics: These surface Pb sites create trap states that dramatically increase non-radiative recombination, limiting the open-circuit voltage (VOC) in solar cells and the external quantum efficiency (EQE) in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [11] [13]. They also undermine the thermal and environmental stability of the nanocrystals.

Table 2: Impact and Passivation of Surface Pb⁰ Defects

| Aspect | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Impact | Significant reduction in PLQY and device efficiency; increased trap-assisted recombination. | [11] [10] |

| Passivation Strategy | Use of Lewis base molecules (e.g., imide derivatives, ionic liquids) whose electron-donating atoms (O, N) bind to undercoordinated Pb²⁺. | [11] [15] |

| Specific Example | Caffeine passivation of perovskite QDs improved LED performance, with current and external quantum efficiencies significantly higher than pristine QDs. | [11] |

| Theoretical Support | DFT calculations show strong binding energy (-1.49 eV) between triflate (OTF⁻) anions and Pb²⁺ on QD surface, confirming effective passivation. | [15] |

Bromine (Br) Vacancies

Bromine vacancies (VBr) are a specific and particularly detrimental subset of halide vacancies in bromine-containing wide-bandgap (WBG) perovskites.

- Challenges in Wide-Bandgap Perovskites: WBG perovskites (e.g., Cs₀.₂FA₀.₈Pb(I₀.₇Br₀.₃)₃) are crucial for tandem solar cells but suffer from high photovoltage loss and phase separation. A major source of these issues is the high density of Br vacancies at the surface and interfaces, which act as non-radiative recombination centers [14].

- Instability and Trap Formation: Br⁻ ions begin to escape from the perovskite lattice at relatively low temperatures (around 100°C), increasing the vacancy density. This leads to significant hysteresis, phase segregation, and thermal instability [14]. The deep trap nature of these vacancies in wider-bandgap systems accelerates hot carrier cooling, reducing the hot phonon bottleneck effect [12].

Quantitative Analysis of Defect Impact

The following table synthesizes quantitative data on how these defects influence key performance metrics in optoelectronic devices, as reported in recent studies.

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Defect Passivation on Device Performance

| Device Type | Passivation Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Control Device | Passivated Device | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBG PSC (1.73 eV) | PEABr (Br vacancy supplement & passivation) | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Not specified | 19.29% | [14] |

| Open-Circuit Voltage (VOC) | Not specified | 1.27 V | [14] | ||

| Operational Stability (T80 at MPP) | Not specified | 90% after 325 h | [14] | ||

| PeLED (Green) | Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 7.57% | 20.94% | [15] |

| Operational Lifetime (T50 @ 100 cd/m²) | 8.62 h | 131.87 h | [15] | ||

| EL Response Rise Time (Steady-state) | ~2.8 µs (est.) | 700 ns | [15] | ||

| Perovskite QD Film | Caffeine (Imide derivative) | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Not specified | 99% | [11] |

| Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) | Acetate & 2-HA ligands | ASE Threshold | 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² | 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² (70% reduction) | [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Characterization and Analysis

A critical component of defect research is the accurate characterization of trap densities and their dynamics. The following are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol: Tuning Defect Density via Antisolvent Purification

This protocol, adapted from [12], is used to intentionally introduce a controlled density of surface halide vacancies in colloidal perovskite nanocrystals (NCs) to study their impact on carrier dynamics.

- Synthesis: Synthesize colloidally stable CsPbX₃ (X = Br, I, or mixture) NCs using the standard hot-injection method.

- Purification (First Cycle): Centrifuge the as-synthesized NC solution and re-disperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane or toluene).

- Intentional Defect Introduction: To the dispersed NCs, add a low-polarity antisolvent (e.g., methyl acetate) and centrifuge the mixture. This process partially removes surface ligands and halide ions, creating surface vacancies without significantly altering the NC size or core structure.

- Repeat Purification: For higher defect densities, repeat Step 3 multiple times. The number of purification cycles is directly correlated with an increase in surface halide vacancy density, as confirmed by a decreasing halide-to-Pb ratio in XPS measurements.

- Validation: Characterize the resulting NCs after each cycle.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Measure the Pb 4f and Halide 3d core-level spectra to calculate the Pb:Halide ratio, which decreases with increasing purification cycles.

- Photothermal Deflection Spectroscopy (PDS): Measure the sub-bandgap absorption. An increase in absorption and the derived Urbach energy indicates a higher density of trap states.

- Steady-State Photoluminescence (PL): Track the PLQY, which will decrease with increasing defect density for non-defect-tolerant compositions (e.g., CsPbBr₃).

Protocol: Charge Carrier Lifetime Measurement via Transient Photovoltage (TPV)

This protocol, based on [17], is used to determine the charge carrier lifetime in a complete solar cell device, which is directly influenced by defect-mediated recombination.

- Device Preparation: Fabricate a planar perovskite solar cell with a structure such as ITO/PEDOT:PSS/Perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag.

- Setup Configuration: Place the device under a steady, background white light bias (e.g., from an LED) set to an intensity equivalent to 1 sun (100 mW/cm²). This biases the device to its open-circuit voltage (VOC).

- Apply Perturbation: Use a pulsed laser (e.g., a small diode laser) to generate a short, low-intensity light pulse that creates a small perturbation in the charge carrier density (Δn) within the device.

- Voltage Transient Measurement: Monitor the resulting small change in open-circuit voltage (ΔV) over time using a high-speed oscilloscope. The voltage transient should decay back to the steady-state VOC.

- Data Analysis: Fit the decaying voltage transient with a single exponential function (for planar devices without a mesoporous TiO₂ layer) to extract the small perturbation charge carrier lifetime, τ.

- The lifetime τ is a critical parameter defining, together with mobility, the charge carrier diffusion length. Lower lifetimes indicate higher defect densities and more pronounced non-radiative recombination.

Visualization of Defect Passivation and Characterization Workflows

Defect Passivation Mechanisms at the Nanocrystal Surface

This diagram illustrates the atomic-level interaction between common defect passivation agents and the specific surface defects they target on a perovskite nanocrystal.

Workflow for Correlating Defect Density with Hot Carrier Cooling

This experimental workflow outlines the key steps for investigating the relationship between intentionally introduced defects and the dynamics of hot carriers, a crucial process for high-efficiency photovoltaics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key chemical reagents used in the cited research for the synthesis, passivation, and defect management of perovskite nanocrystals.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Defect Passivation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Experimental Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar antisolvent for purification. Used to intentionally introduce surface halide vacancies by stripping surface ions and ligands [12]. | Multiple purification cycles (e.g., 1x, 2x) are used to create a controlled gradient of defect densities for comparative studies [12]. |

| Phenylethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Molecular cation salt for interfacial passivation. Simultaneously passivates surface defects and supplements bromine vacancies without forming a 2D perovskite layer [14]. | Applied as a post-treatment on the pre-formed perovskite film. Reduces non-radiative recombination at the interface with the hole transport layer (e.g., spiro-OMeTAD) [14]. |

| Imide Derivatives (e.g., Caffeine) | Lewis base molecules for surface defect passivation. Electron-donating carbonyl oxygen atoms coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, neutralizing trap states [11]. | Added during or after QD synthesis. Significantly improves PLQY and thermal stability. Successful in fabricating red, green, and blue LEDs with a wide color gamut [11]. |

| Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF | Additive for crystallization control and defect passivation. Cations coordinate with halides, anions bind strongly to Pb²⁺, suppressing surface defects and reducing charge injection barriers [15]. | Added to the precursor solution. Promotes growth of larger, higher-crystallinity QDs, leading to higher PLQY and dramatically faster electroluminescence response in PeLEDs [15]. |

| Potassium Triiodide (KI₃) | Additive for surface chemistry optimization in PbS CQDs. Dissociative I₂ eliminates undercharged Pb species and dangling S sites, while K⁺ helps passivate uncapped surfaces [13]. | Used in a one-step ligand exchange process combined with conventional PbX₂ matrix ligands. Results in lower defect density and enhanced device stability in air [13]. |

The Direct Link Between Trap States and Non-Radiative Recombination

In metal halide perovskites, trap states acting as non-radiative recombination centers are a primary factor limiting the performance and stability of optoelectronic devices. This whitepaper examines the fundamental mechanisms linking defect-induced trap states to performance-degrading non-radiative pathways. Surface and interfacial defects in perovskite nanocrystals create energetic landscapes that capture charge carriers, preventing radiative recombination and reducing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). Advanced surface passivation strategies, including lattice-matched molecular anchors and spatially confined synthesis, have demonstrated remarkable success in suppressing these losses, enabling devices such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to achieve external quantum efficiencies (EQE) exceeding 26% [18]. A detailed understanding of trap state dynamics is therefore essential for developing the next generation of high-performance perovskite optoelectronic devices.

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of metal halide perovskites, including long carrier diffusion lengths and high absorption coefficients, are often compromised by defect-mediated recombination losses. Trap states are localized electronic energy levels within the band gap that originate from crystallographic defects such as vacancies, interstitials, and anti-sites, particularly at surfaces and grain boundaries where the periodic lattice structure is broken [19]. In perovskite quantum dots (QDs), the high surface-to-volume ratio makes them exceptionally susceptible to surface defects.

The presence of these trap states has direct and severe consequences for device performance. They serve as non-radiative recombination centers, where excited electron-hole pairs recombine without emitting photons, releasing energy as heat instead. This process directly competes with radiative recombination, leading to lower PLQY in light emitters [20] and reduced open-circuit voltage (VOC) in photovoltaics [19]. In practical terms, even small densities of deep traps can significantly degrade device efficiency and operational stability by facilitating non-radiative pathways and initiating degradation processes.

Quantitative Analysis of Trap State Impact

The following tables consolidate quantitative findings from recent studies, demonstrating the direct correlation between trap state density, non-radiative recombination, and device performance metrics.

Table 1: Impact of Trap States on Perovskite Quantum Dot Optical Properties and Device Performance

| Material/System | Trap State Characteristics | Impact on Optical Properties | Device Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI3 QDs with TMeOPPO-p | Multi-site anchoring eliminates Pb-6pz trap states near Fermi level | PLQY increases from 59% (pristine) to 97% (passivated) | QLED EQE: 26.91%; Operating lifetime > 23,000 h | [18] |

| CsPbBr3 QDs in Cs-ZIF-8 MOF | Spatial confinement reduces surface defect density | Enables pure-blue emission at 460 nm via quantum confinement | Pure-blue PeLED: EQE = 5.04%, Luminance = 2,037 cd m⁻² | [21] |

| CsPbBr3 QDs with AcO⁻/2-HA | Surface passivation suppresses Auger recombination | PLQY of 99%; Narrow emission linewidth (22 nm) | ASE threshold reduced by 70% to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² | [22] |

| CsPbBr3 Nanoplatelets (NPLs) | PbBr2 treatment removes picosecond-nanosecond trapping pathways | PLQY enhancement; ~40% of NPLs are permanently non-fluorescent ("dark fraction") | -- | [20] |

Table 2: Trap State Dynamics and Characterization in Perovskite Thin Films

| Material/System | Trap Type & Density Enhancement | Characterization Method | Key Finding on Non-Radiative Recombination | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACs Perovskite with surface strain | Shallow trap density increased >100x via surface microstrain | Modified transient photocurrent measurement | Shallow traps temporarily hold charges, reduce bimolecular recombination, VOC loss minimized to 317 mV | [19] |

| CsPbBr3 Nanoplatelets (NPLs) | Trapping rates from sub-ps to ns; Detrapping on ns-μs timescales | Streak camera + TCSPC over 6 decades in time | Trapping with non-radiative recombination lowers PLQY; Trapping-detrapping causes delayed emission | [20] |

| MAPbI3 Films | High-density shallow traps (<100 meV depth) | Time-resolved microwave conductivity (TRMC) | Long carrier lifetime attributed to shallow traps that trap and re-emit charges | [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Trap States

Accurately characterizing trap states requires sophisticated methodologies to quantify their density, energy depth, and dynamic behavior.

Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) Spectroscopy

This technique measures the decay of photoluminescence after pulsed excitation, providing direct insight into charge carrier recombination dynamics.

- Procedure:

- Excite the perovskite sample (e.g., CsPbBr3 NPLs or QD film) with a short pulsed laser (e.g., 375 nm picosecond laser diode).

- Collect the emitted photoluminescence using a high-speed detector, such as in a time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) system or a streak camera.

- Record the decay curve over a wide temporal range (picoseconds to microseconds).

- Data Analysis:

- Multiexponential fitting of the decay curve (e.g., ( I(t) = A1exp(-t/τ1) + A2exp(-t/τ2) + ... ) ).

- The fast decay components (τ₁) are typically attributed to non-radiative recombination via trap states.

- The slow components (τ₂) can be attributed to radiative recombination and/or delayed emission from charge carrier detrapping [20].

- Key Insight: The technique revealed that in CsPbBr3 NPLs, trapping occurs from sub-picoseconds to nanoseconds, while detrapping can happen on nanosecond-to-microsecond timescales [20].

Quantifying Shallow Traps in Working Solar Cells

A modified transient photocurrent method has been developed to directly quantify charge-emitting shallow traps in operational devices.

- Procedure:

- Apply a small, fixed bias voltage to the perovskite solar cell device.

- Excite the device with a short laser pulse to generate charge carriers.

- Measure the transient photocurrent with high temporal resolution.

- Analyze the percentage of charges that are extracted immediately, those that recombine non-radiatively, and those that are temporarily trapped and then re-emitted [19].

- Data Analysis:

- The detrapped charge signal is directly correlated to the density of active shallow traps.

- This method revealed that shallow trap density in perovskites can be enhanced by over 100 times through the introduction of surface strain [19].

Integrating Sphere PLQY Measurements

This is a direct method for assessing the overall efficiency of radiative recombination and the extent of non-radiative losses.

- Procedure:

- Place the sample (e.g., a QD solution or film) inside an integrating sphere.

- Excite the sample with a continuous-wave or pulsed laser source.

- Measure the total emitted photon flux versus the absorbed photon flux using a spectrometer.

- Data Analysis:

- The PLQY is calculated as the ratio of emitted photons to absorbed photons.

- A PLQY below 100% is direct evidence of non-radiative recombination channels, including those mediated by trap states [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following reagents and materials are critical for the synthesis and passivation of high-quality perovskite quantum dots, as identified in the cited research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Trap State Management

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Ligands | Passivate surface defects and improve charge transport compared to long-chain insulating ligands. | DPPA (3,3-Diphenylpropylamine) used in pure-blue CsPbBr3 QD-LEDs to enhance carrier transport [21]. |

| Lattice-Matched Anchors | Multi-site binding to under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions, providing strong surface passivation and stabilizing the lattice. | TMeOPPO-p (Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide) with 6.5 Å O-atom spacing matching the QD lattice, achieving 97% PLQY [18]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Provide a spatial confinement matrix to control nanocrystal growth and suppress aggregation/overgrowth. | Cs-ZIF-8 used as a cesium source and confinement matrix to synthesize ultrasmall (1.9 nm), monodisperse CsPbBr3 QDs [21]. |

| Optimized Cesium Precursors | Improve batch-to-batch reproducibility and reduce defect formation by ensuring complete conversion and high precursor purity. | Acetate (AcO⁻) combined with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) increases cesium precursor purity to 98.59%, leading to 99% PLQY QDs [22]. |

| Surface Strain-Inducing Molecules | Intentionally create surface microstrain to modulate the density and behavior of shallow trap states. | Two-amine-terminated molecules anchored to FA⁺ cations used to increase shallow trap density by >100x [19]. |

Visualizing Trap State Dynamics and Characterization

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows related to trap state dynamics.

Trap State Dynamics in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Diagram 1: Trap State Dynamics and Passivation. This diagram illustrates (A) the competitive pathways for photoexcited charge carriers, including radiative recombination, trapping in shallow states (which can detrap), and non-radiative recombination via deep traps. (B) The passivation process where lattice-matched anchor molecules bind to surface sites, eliminating defect states [18] [20].

Experimental Workflow for Trap State Analysis

Diagram 2: Trap State Characterization Workflow. This flowchart outlines a combined spectroscopic approach for a comprehensive analysis of trap states, correlating steady-state efficiency (PLQY) with dynamics (TRPL) and electrical behavior (Transient Photocurrent) to fully quantify non-radiative pathways [19] [20].

The direct link between trap states and non-radiative recombination is a central consideration in perovskite materials science. The suppression of these performance-limiting defects requires a multi-faceted approach, combining advanced synthesis for superior crystallinity, innovative surface passivation strategies using lattice-matched ligands, and precise postsynthesis treatments. The remarkable recent progress in perovskite QD LEDs—achieving near-unity PLQY and EQEs rivaling established technologies—demonstrates the profound impact of mastering trap state physics [18] [22]. Future research will continue to focus on elucidating the atomic-scale nature of defects, developing ever-more precise passivators, and engineering trap landscapes to unlock the full potential of perovskite optoelectronics.

The performance of optoelectronic devices based on perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) is fundamentally governed by key properties such as photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), charge transport, and overall device efficiency. These properties are intrinsically linked to the surface states and trap density of PNCs, which arise from their high surface-area-to-volume ratio and dynamic ionic nature. This whitepaper synthesizes recent advancements in surface engineering strategies, including ligand exchange, passivation, and nanosurface reconstruction, which have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in mitigating non-radiative recombination and enhancing charge carrier mobility. By contextualizing these findings within a broader thesis on surface states, we provide a technical guide that delineates the mechanistic pathways from surface manipulation to performance enhancement, supported by quantitative data and detailed experimental protocols. The insights presented herein aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to advance the development of high-performance PNC-based optoelectronic devices.

Perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs), particularly all-inorganic CsPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I), have emerged as a frontrunner for next-generation optoelectronic applications, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, and photovoltaics [23]. Their appeal lies in exceptional size- and composition-tunable optical properties, high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), and cost-effective solution processability [22]. However, the paramount challenge obstructing their commercial viability stems from their inherent "soft" ionic lattice and ultrahigh surface-area-to-volume ratio. These characteristics lead to a dynamic surface equilibrium prone to the formation of defects, which act as trapping states for charge carriers [23] [24].

The presence of these surface traps directly and detrimentally impacts the core optoelectronic properties under review:

- PLQY: Trap states serve as centers for non-radiative Auger recombination, dissipating excited state energy as heat and drastically reducing the efficiency of light emission [22] [24].

- Charge Transport: Long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) used in synthesis create barriers between individual NCs, while surface defects scatter and trap charge carriers, severely impeding inter-dot transport and leading to low conductivity in solid films [25] [15].

- Device Efficiency: Ultimately, low PLQY and poor charge transport manifest in optoelectronic devices as low power conversion efficiencies (PCE) in photovoltaics, and low external quantum efficiencies (EQE) and slow response times in LEDs [26] [15].

Therefore, the central thesis of modern PNC research posits that rational surface engineering is the critical pathway to suppress trap density, manage surface states, and unlock the full potential of these materials. This guide details the strategies and mechanisms through which this is achieved.

Surface Engineering Strategies and Quantitative Impacts

Advanced surface chemistry strategies have been developed to address the trifecta of challenges: defect passivation, ligand insulation, and halide segregation. The quantitative outcomes of these strategies on key optoelectronic properties are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Surface Engineering on Optoelectronic Properties

| Strategy | Specific Material/ Method | Impact on PLQY | Impact on Charge Transport/ Mobility | Final Device Performance | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic Ligand Exchange | Benzylammonium Bromide [26] | Not Specified | Not Specified | EQE: 5.88% (vs. 2.4% pristine) | Orbital overlap reduces defects, enhances charge injection. |

| Multi-Functional Passivation | Tetraphenylporphyrin Sulfonic Acid (TPPS) [27] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Pure-red LED EQE: 22.47% | Sulfonate passivates halide defects; porphyrin enhances stability & charge mobility. |

| Ionic Liquid Treatment | [BMIM]OTF [15] | Solution: 85.6% → 97.1% | Promotes carrier injection | EQE: 20.94% (vs. 7.57% control)Response Time: Reduced by 75% | Enhances crystallinity, reduces surface defects & injection barrier. |

| Binary Synergistical Post-Treatment | tBBAI & PPAI blend [28] | Not Specified | Improved hole extraction & transfer | PCE (Solar Cell): 26.0% (certified) | Enhanced crystallinity & molecular packing of passivation layer. |

| Precursor & Ligand Optimization | Acetate/2-HA ligand [22] | ~99% | Suppressed Auger recombination | ASE Threshold: Reduced by 70% (0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) | Improved precursor purity, defect passivation, suppressed recombination. |

| Ligand Removal & Ripening | MeOAc & Annealing [25] | Not Specified | Mobility: ~0.023 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹Lifetime: 9.7x increase | Effective as a gas sensor | Insulating ligand removal, trap density modification. |

The data demonstrates that diverse surface engineering approaches consistently lead to profound improvements in device-level metrics. Enhancements are achieved by targeting the fundamental electronic processes at the nanocrystal surface.

Mechanistic Pathways from Surface States to Device Performance

The following diagram illustrates the causal pathways through which surface states influence material properties and how specific engineering strategies intervene to improve device performance.

Diagram 1: Pathways from surface states to device performance and strategic interventions. Surface states and ionic migration (red) drive detrimental processes (yellow) that degrade key properties (green) and final device performance (blue). Surface engineering strategies (green nodes) target these specific pathways for improvement.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Surface Engineering

To replicate the cited advancements, researchers require precise experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key surface engineering approaches.

Objective: To replace native long-chain insulating ligands with conjugated aromatic ligands to improve charge injection and passivate surface defects in CsPbBr₃ NCs. Materials: Synthesized CsPbBr₃ NCs, Benzylammonium Bromide (BABr), anhydrous solvents (e.g., Toluene, Hexane, Methyl Acetate). Procedure:

- Purification: Precipitate the pristine CsPbBr₃ NCs from the crude solution by adding methyl acetate as an anti-solvent, followed by centrifugation. Re-disperse the pellet in anhydrous toluene.

- Ligand Solution Preparation: Dissolve BABr in a suitable anhydrous solvent (e.g., isopropanol) to create a concentrated stock solution.

- Exchange Reaction: Under inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen glovebox), add the BABr solution dropwise to the purified NC solution under vigorous stirring. The typical ratio is 1 mL of NC solution to 10-50 µL of BABr stock (10 mg/mL).

- Incubation: Allow the reaction mixture to stir for 5-15 minutes. The progression can be monitored via spectral shifts or PL intensity changes.

- Purification: Precipitate the ligand-exchanged NCs by adding an excess of methyl acetate. Centrifuge the mixture to obtain a pellet and discard the supernatant containing the displaced native ligands and reaction by-products.

- Re-dispersion: Re-disperse the final product in an anhydrous solvent for film fabrication or characterization.

Objective: To implement a dual-functional passivation for mixed-halide CsPb(Br/I)₃ NCs to suppress halide segregation and non-radiative recombination. Materials: Pristine CsPb(Br/I)₃ NCs, Tetraphenylporphyrin Sulfonic Acid (TPPS), Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), Toluene. Procedure:

- NC Synthesis and Initial Purification: Synthesize ultrasmall CsPb(Br/I)₃ NCs via a standard hot-injection method. Perform an initial centrifugation to remove large aggregates.

- TPPS Solution Preparation: Dissolve TPPS in a minimal amount of a polar solvent (e.g., DMF) to create a concentrated stock solution.

- Post-Treatment: Add the TPPS solution dropwise to the purified NC solution under stirring. The mass ratio of TPPS to NCs should be optimized, typically within 1-5 wt%.

- Stirring and Reconstruction: Stir the mixture for 30-60 minutes to allow the TPPS ligands to coordinate with the NC surface. The sulfonate groups bind to uncoordinated halide sites, while the porphyrin macrocycles form a hydrophobic barrier.

- Purification: Precipitate the TPPS-modified NCs (TPPS-NCs) by adding toluene. Centrifuge and re-disperse the purified NCs in an appropriate solvent for device fabrication.

Objective: To enhance the crystallinity and reduce the surface defect density of CsPbBr₃ QDs, thereby improving PLQY and charge injection. Materials: Lead bromide (PbBr₂) precursor, Cesium Oleate, 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF), Chlorobenzene (CB), Octanoic Acid (OTAC). Procedure:

- In-situ Crystallization Strategy: Dissolve [BMIM]OTF in chlorobenzene at varying concentrations (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 3 mg/mL).

- Precursor Modification: Add the [BMIM]OTF/CB solution to the PbBr₂ precursor solution containing standard ligands like OTAC.

- Nucleation and Growth: Inject the cesium oleate precursor into the modified PbBr₂ precursor at elevated temperature (e.g., 160-180 °C). The [BMIM]+ ions coordinate with [PbBr₃]⁻ octahedra, slowing nucleation and promoting the growth of larger, highly crystalline QDs.

- Purification and Film Formation: The resulting QDs are purified via standard centrifugation and antisolvent procedures. Films are deposited by spin-coating the QD ink.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues critical reagents used in the featured surface engineering experiments, along with their primary functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Surface Engineering of PNCs

| Reagent Name | Function in Research | Technical Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Benzylammonium Halides [26] | Aromatic Ligand for Exchange | Replaces insulating ligands; π-conjugation enables orbital overlap with NC surface, enhancing charge injection and passivating defects. |

| Tetraphenylporphyrin Sulfonic Acid [27] | Dual-Functional Passivator | Sulfonate groups passivate halide vacancies via ionic coordination; porphyrin macrocycle forms a hydrophobic barrier, suppressing halide migration. |

| [BMIM]OTF Ionic Liquid [15] | Crystallization Modifier & Passivator | [BMIM]+ coordinates with halides to slow nucleation, promoting larger crystals; OTF⁻ anions strongly bind to Pb²⁺ sites, passivating surface defects. |

| 4-tert-Butyl-Benzylammonium Iodide [28] | Component of Binary Passivation | Blended with PPAI to form a crystalline passivation layer with enhanced molecular packing, improving hole extraction and energy level alignment. |

| Acetate/2-Hexyldecanoic Acid [22] | Short-Branched-Chain Ligand System | Acetate (AcO⁻) acts as a surface ligand and improves precursor conversion; 2-HA has stronger binding than oleic acid, effectively suppressing Auger recombination. |

| Methyl Acetate [25] | Antisolvent for Ligand Removal | Used in soft soaking and purification steps to remove native long-chain insulating ligands, thereby reducing inter-dot spacing and improving conductivity. |

The direct correlation between the mitigation of surface states and the enhancement of key optoelectronic properties is unequivocally established. Surface engineering has transitioned from a mere processing step to a central research paradigm in perovskite nanocrystal technology. As evidenced by the quantitative data, strategies such as conjugated ligand exchange, multi-component passivation, and ionic liquid-assisted crystallization can simultaneously achieve near-unity PLQY, enhanced charge transport, and record-breaking device efficiencies. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit provided herein serve as a foundational guide for researchers aiming to contribute to this rapidly evolving field. Future progress hinges on the development of even more robust and scalable surface chemistry solutions, potentially guided by artificial intelligence, to overcome the lingering challenges of stability and large-scale fabrication, ultimately translating laboratory breakthroughs into commercial technologies.

Metal halide perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) have emerged as superstar materials for next-generation optoelectronics, boasting exceptional properties such as high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs), tunable bandgaps, and long charge-carrier diffusion lengths [29] [30]. Despite their impressive performance, the commercial application of PNCs is severely hampered by their notorious instability, which originates from both intrinsic crystal structure vulnerabilities and susceptibility to extrinsic environmental factors [29]. The inherent ionic nature and low formation energy of perovskites make them inherently prone to degradation, while labile surface ligand binding further exacerbates these stability issues [29] [31]. Understanding the interplay between intrinsic crystal instability and dynamic ligand behavior is crucial for advancing PNCs toward practical applications, particularly within the broader context of managing surface states and trap density that govern device performance and longevity.

Intrinsic Instability Mechanisms

Crystal Structure and Phase Instability

The intrinsic instability of PNCs primarily stems from their ionic crystal structure and low formation energy. Metal halide perovskites typically adopt an ABX3 structure, where A is a monovalent organic (MA+, FA+) or inorganic (Cs+) cation, B is a divalent metal cation (Pb2+, Sn2+), and X is a halide anion (I-, Br-, Cl-) [29] [1]. This structure features a corner-sharing [BX6]4- octahedral framework with A-site cations occupying the cuboctahedral cavities [1].

Phase transformation represents a critical intrinsic instability pathway. For instance, the photoactive black phase (α or γ) of CsPbI3 readily transforms into a non-perovskite, non-photoactive yellow phase (δ-CsPbI3) under ambient conditions [29]. This transformation occurs more rapidly in nanocrystal films (within a day) compared to NCs in solution (days to months) [29]. The Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t = (rA + rX)/√2(rB + rX)), where rA, rB, and rX represent the ionic radii of the respective components, provides a useful empirical guideline for predicting phase stability, with values between 0.8 and 1.0 generally favoring a stable 3D perovskite structure [1].

Table 1: Common Intrinsic Instability Pathways in Perovskite Nanocrystals

| Instability Type | Mechanism | Impact on Properties | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Transformation | Transition from photoactive to non-photoactive crystal phase | Loss of luminescence, altered bandgap | α-CsPbI3 → δ-CsPbI3 [29] |

| Ligand Detachment | Dynamic desorption of surface-bound ligands | NC aggregation, PLQY quenching, degradation [29] | Oleylammonium loss leading to coalescence [31] |

| Ion Migration | Low activation energy for vacancy-mediated ion movement | Phase segregation, increased trap states, performance hysteresis [1] | Halide ion migration under bias [1] |

Ligand Dynamics and Surface Chemistry

The surface chemistry of PNCs plays a pivotal role in their intrinsic stability. Ligands such as oleylamine (OAm) and oleic acid (OA) are commonly used to stabilize PNCs during synthesis and in colloidal dispersions [31] [30]. However, the binding between these ligands and the NC surface is inherently labile and dynamic.

The canonical ligand system of oleylammonium (OAmH+) and carboxylates (e.g., oleate, OAc-) exhibits ionic binding that enables dynamic desorption through either deprotonation (OAmH+ + OAc- ⇋ OAm + OAcH) or salt formation (OAmH+ + OAc- ⇋ OAmHOAc or OAmH+ + Br- ⇋ OAmHBr) [31]. This dynamic equilibrium leads to ligand detachment during purification or with aging, resulting in NC aggregation, degradation, and loss of optical properties [29] [31]. Early-generation PNCs capped with OAm/OAcH combinations were particularly susceptible to deprotonation-induced instability, losing PLQY and colloidal integrity when exposed to polar solvents during purification [31].

Extrinsic Instability Factors

Extrinsic instability refers to the degradation of PNCs triggered by external environmental stressors including moisture, oxygen, heat, and light [29]. These factors often accelerate the intrinsic degradation pathways, leading to rapid performance deterioration.

Table 2: Extrinsic Instability Factors and Their Impacts on Perovskite Nanocrystals

| Stress Factor | Degradation Mechanisms | Observed Effects | Accelerated Intrinsic Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture/Water | Hydration, ion dissolution, lattice disruption | Loss of crystallinity, PL quenching, decomposition [29] | Accelerated phase transformation [29] |

| Oxygen | Photo-oxidation, defect formation | PL quenching, surface degradation [29] | Ligand detachment, trap state formation [29] |

| Light | Photo-induced ion migration, ligand desorption | Phase segregation, morphology changes, NW formation [29] | Ion migration, defect formation [29] |

| Heat | Thermal decomposition, ligand desorption | Phase transition, crystal growth, aggregation [29] | Accelerated ligand dynamics [29] |

The synergistic effect of multiple stressors often causes more severe degradation than individual factors. For example, the combination of heat and moisture rapidly degrades PNCs, while light-induced damage is worsened in the presence of oxygen, leading to photo-oxidation [29]. The wavelength of light also influences degradation, with UV light being particularly effective at removing surface ligands compared to visible light [29].

Experimental Methodologies for Stability Investigation

Ligand Binding Dynamics Analysis

Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy (DOSY NMR) provides a powerful method for investigating ligand binding dynamics at LHP NC surfaces [31]. This technique enables the differentiation between bound and free ligands in native colloidal solutions based on their diffusion coefficients.

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare CsPbBr3 NC solutions with varied ligand concentrations (e.g., guanidinium ligands, primary ammonium, zwitterionic ligands) [31].

- Acquire DOSY NMR spectra using a standardized pulsed-field gradient NMR sequence.

- Analyze diffusion coefficients to determine binding constants and exchange rates.

- Compare headgroup influences on binding dynamics by surveying ligands with different headgroups (sulfobetaine, phosphocholine, phosphoethanolamine, guanidinium) [31].

This methodology revealed that guanidinium ligands strike an optimal balance between dynamic binding and stability, with exchange rates matching primary ammonium ligands while significantly enhancing binding strength [31].

Shallow Trap Characterization

A specialized methodology has been developed to directly characterize charge-emitting shallow traps in working perovskite solar cell devices, which is equally applicable to PNC films [19].

Experimental Workflow:

- Fabricate perovskite devices or films with controlled surface strain introduced through chemical treatment (e.g., two-amine-terminated molecules anchoring onto formamidinium cations) [19].

- Apply a specialized charge extraction protocol to quantify the percentage of charges that are extracted without encountering traps, undergo non-radiative recombination, or are trapped and re-emitted [19].

- Correlate shallow trap density with surface microstrain, which can enhance shallow trap density by >100 times [19].

- Analyze the impact of high-density shallow traps on device performance parameters, particularly open-circuit voltage (VOC) [19].

This approach has demonstrated that high-density shallow traps can temporarily hold electrons and increase free-hole concentration by preventing bimolecular recombination, reducing VOC loss to 317 mV in formamidinium-caesium (FACs) perovskite systems [19].

Photocatalytic Activity Assessment

Photocatalytic testing provides an indirect method for evaluating PNC stability under reactive conditions while assessing surface accessibility—a key indicator of ligand binding dynamics [31] [32].

Protocol for C–C Bond Formation Catalysis:

- Synthesize CsPbBr3 NCs using hot-injection method with targeted ligands (e.g., guanidinium-based ligands) [31].

- Disperse NCs in appropriate organic solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran for stable ligands) [31].

- Set up photocatalytic reactions for fundamental organic transformations (C–C, C–N, C–O bond formations) under visible light irradiation [32].

- Monitor reaction progress via GC-MS or NMR spectroscopy to quantify yield.

- Correlate catalytic performance with NC stability, noting that dynamically bound ligands (e.g., guanidinium) enhance surface accessibility for superior performance in photocatalytic C–C coupling compared to static binders [31].

This methodology demonstrated that GA-based ligands significantly outperform more static ligands in photocatalytic applications due to their optimal balance of dynamic binding and stability [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Perovskite Nanocrystal Stability Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic Guanidinium Ligands | Cationic ligands combining compactness with deprotonation resistance | Surface stabilization with dynamic yet tight binding | [31] |

| Zwitterionic Ligands (PC, PEA) | Strong static binding via chelate effect | Enhanced stability in polar solvents | [31] |

| Oleylamine/Oleic Acid | Canonical ligand pair for ionic binding | Standard synthesis, baseline studies | [31] [30] |

| Two-Amine-Terminated Molecules | Introduce surface microstrain | Shallow trap density modulation | [19] |

| PbX2 (X=Cl, Br, I) | Halide source for perovskite framework | NC synthesis, compositional tuning | [29] [30] |

| Cs-oleate | Cesium precursor for all-inorganic PNCs | Hot-injection synthesis | [30] |

| Stability Matrices (Polymers, MOFs, Oxides) | Encapsulation and protection | Extrinsic stability enhancement | [29] [33] |

Interrelationship Between Intrinsic/Extrinsic Factors and Trap States

The intrinsic and extrinsic instability factors directly influence surface states and trap density in PNCs, creating a complex interplay that ultimately determines device performance and longevity. Intrinsic factors like ligand detachment create unsaturated bonds on the NC surface that act as trap states for charge carriers, promoting non-radiative recombination [29] [19]. Similarly, phase transformations alter the electronic structure of the material, potentially creating interfacial trap states between different crystal phases [29].

Extrinsic factors accelerate trap formation through multiple pathways. Moisture induces hydration reactions that create defect sites, while oxygen and light synergistically promote photo-oxidation processes that generate surface traps [29]. These trap states then act as nucleation points for further degradation, creating a positive feedback loop that accelerates PNC deterioration.

The instability of perovskite nanocrystals stems from a complex interplay between intrinsic crystal structure vulnerabilities and dynamic ligand chemistry, exacerbated by extrinsic environmental factors. Intrinsic phase instability and labile ligand binding create a foundation for degradation, while extrinsic stressors like moisture, oxygen, and light accelerate these processes, collectively increasing surface trap states and compromising device performance.

Future research directions should focus on developing advanced in situ characterization techniques to directly observe dynamic processes at the NC surface, enabling real-time monitoring of ligand binding and phase transformations [34]. Computational materials design approaches, including machine learning-guided composition optimization, will accelerate the discovery of novel perovskite formulations with enhanced intrinsic stability [1]. Additionally, multifunctional ligand systems that combine dynamic binding with robust surface passivation represent a promising avenue for simultaneously addressing intrinsic and extrinsic instability pathways [31].

The strategic engineering of shallow traps through controlled surface strain offers an innovative approach to managing charge recombination pathways [19]. Furthermore, the development of standardized stability testing protocols that account for both intrinsic and extrinsic factors will enable more accurate prediction of device lifetime under real-world operating conditions. As these strategies mature, the gap between laboratory demonstration and commercial application of PNC-based technologies will continue to narrow, ultimately fulfilling the promise of these exceptional materials.

The defect tolerance of lead-halide perovskites, a cornerstone of their high performance in optoelectronics, has been predominantly understood in the context of band-edge cold carriers. This whitepaper examines the extension of this paradigm to hot carrier (HC) dynamics, a frontier with significant implications for next-generation solar cells and optical gain media. Recent research reveals that hot carriers are not universally defect tolerant; their susceptibility to traps is governed by defect energy and material composition. Through intentional defect engineering in CsPbX3 nanocrystals (X = Br, I), it is established that HC defect tolerance is contingent upon the presence of shallow traps, a condition met in compositions like CsPbI3. This document synthesizes experimental evidence, quantitative data, and methodologies to provide a comprehensive technical guide on managing trap density and surface states for advanced perovskite applications.

Defect tolerance is a critical enabling property of efficient lead-halide perovskite (LHP) materials. In conventional semiconductors, defects and surface states create mid-gap trap states that act as non-radiative recombination centers, severely degrading device performance. In contrast, defect-tolerant LHPs exhibit a remarkable insensitivity of charge-carrier lifetimes and mobilities to the presence of defects. Historically, this concept has been defined and quantified through the behavior of band-edge "cold" carriers, typically measured via photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and time-resolved photoluminescence (PL). The prevailing understanding attributes this tolerance to the specific electronic structure of LHPs, where defect levels are shallow and do not introduce deep, mid-gap states that would otherwise facilitate rapid non-radiative recombination.

However, a critical, unresolved question in the field is whether this celebrated defect tolerance extends to hot carriers (HCs)—carriers excited above the bandgap with excess kinetic energy. The management of HCs is pivotal for surpassing the radiative efficiency limit of ~30% in photovoltaics, as their excess energy is typically lost as heat through ultrafast cooling processes. The current literature presents a contradictory picture: some studies suggest HCs are defect-tolerant, while others report significant HC lifetime shortening due to trapping. This whitepaper addresses this gap by framing the discussion within the broader context of surface states and trap density in perovskite nanocrystals, synthesizing recent findings to establish a unified understanding of carrier dynamics from the band-edge to above the bandgap.

Cold vs. Hot Carriers: A Critical Dichotomy

Fundamentals of Cold Carrier Defect Tolerance

The defect tolerance of cold carriers in lead-halide perovskites is a well-documented phenomenon. It is typically observed as high PLQY and long PL lifetimes even in materials with significant defect densities. The physical origin lies in the fundamental electronic properties of LHPs:

- Shallow Defect Levels: Common intrinsic defects, such as halide vacancies, form energy levels close to the band edges. These shallow traps do not act as efficient non-radiative recombination centers, allowing carriers to thermalize back to the band edges and contribute to radiative recombination or useful photocurrent.

- Ionic Character and Screening: The mixed ionic-covalent bonding nature contributes to strong screening of charge defects, reducing their capture cross-sections for charge carriers.

- High Dielectric Constant: The relatively high dielectric constant screens charged defects, further reducing carrier trapping probabilities.

This inherent tolerance has enabled the rapid advancement of perovskite photovoltaics, with certified power conversion efficiencies now reaching 26.7% under 1-sun illumination [12].

The Hot Carrier Challenge

Hot carriers, possessing excess energy above the bandgap, represent a potential pathway to exceed the Shockley-Queisser limit for single-junction solar cells. Theoretically, if HCs can be extracted before they cool to the band edges, or if their excess energy can be utilized to create additional electron-hole pairs through impact ionization, solar cell efficiencies could surpass 40%. However, practical realization has been hampered by extremely fast HC cooling processes, typically occurring on sub-picosecond timescales.

The central debate revolves around whether HCs in perovskites share the defect tolerance properties of their cold counterparts. Some studies suggested this might be the case, while others, notably Jiang et al., indicated that while band-edge carriers in MAPbI3 were defect-tolerant, the HC lifetime was shortened due to trapping at grain boundaries [12]. Resolving this contradiction is essential for designing materials for HC solar cells, multiexciton generation, and optical gain media.

Experimental Insights: Probing Carrier Dynamics

To systematically investigate the relationship between defects and HC dynamics, researchers selected CsPbX3 nanocrystals (X = Br, I, or mixed Br/I) as a model system. This choice offers several advantages:

- Tunable Composition: The bandgap can be precisely engineered through halide composition.

- Controlled Defect Introduction: Defect densities can be intentionally and progressively increased through surface chemistry manipulation.

The methodology for intentional defect creation involved multiple purification steps using the low-polarity antisolvent methyl acetate. This process partially removes surface ligands and halides without significantly altering the nanocrystal size or structure, thereby increasing the density of surface halide vacancies in a controlled manner [12]. The increase in defect density was confirmed through:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Showed a decrease in the surface halide-to-Pb ratio with increasing purification steps [12].

- Photothermal Deflection Spectroscopy (PDS): Revealed enhanced sub-bandgap absorption and increased Urbach energy, indicating higher defect density [12].

Table 1: Characterization of Defect Density in Purified CsPbX3 NCs

| Nanocrystal Type | Purification Steps | PLQY Trend | Urbach Energy | Trap Depth from DFT (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr3 | Increased | Decreased significantly | Increased | 0.666 (Br vacancy) |

| CsPbBrxI3-x | Increased | Decreased significantly | Increased | 0.513 (Br/I vacancy) |

| CsPbI3 | Increased | Remained high | Increased | 0.278 (I vacancy) |

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques

The investigation of carrier dynamics requires sophisticated time-resolved spectroscopic methods capable of resolving ultrafast processes:

- Femtosecond Transient Absorption (TA) Spectroscopy: Employed to probe both interband and intraband transitions, providing insights into carrier populations at different energy levels. This technique monitors the differential transmission (ΔT/T) of a probe pulse following an ultrafast pump pulse, revealing carrier cooling and trapping dynamics [12] [35].

- Pump-Push-Probe (PPP) Spectroscopy: A three-pulse technique that can selectively re-excite cooled carriers to study hot carrier-specific processes.

- Excitation-Energy-Dependent PLQY Measurements: Provides preliminary insight into HC trapping by varying the excitation energy and monitoring changes in PL efficiency [12].

The experimental workflow for correlating defect properties with carrier dynamics is summarized below:

Key Findings: Beyond Universal Defect Tolerance

Composition-Dependent Hot Carrier Tolerance

The research reveals that hot carriers are not universally defect tolerant across all perovskite compositions. Instead, HC tolerance strongly correlates with the defect tolerance of cold carriers and requires the presence of shallow traps:

- CsPbI3 with Shallow Traps: Exhibits preserved HC lifetimes even with increased defect density. DFT calculations confirm that iodide vacancies in CsPbI3 form shallow traps (0.278 eV from conduction band minimum) [12].

- CsPbBr3 with Deep Traps: Shows significantly accelerated HC cooling with increasing defect density. Bromide vacancies in CsPbBr3 create deeper traps (0.666 eV from CBM) [12].

- Mixed Halide CsPbBrxI3-x: Displays intermediate behavior with trap depth of 0.513 eV [12].

This composition dependence was further evidenced by excitation-energy-dependent PLQY measurements. For defective CsPbBr3 and mixed-halide NCs, PLQY decreased by ~15% with excess energy of ~1 eV, indicating additional non-radiative pathways for HCs. In contrast, CsPbI3 NCs showed minimal PLQY change with increasing excitation energy, even with high defect density [12].

Direct Hot Carrier Trapping Mechanism

A crucial finding challenges the conventional assumption that hot carriers must cool to band edges before being trapped:

- Direct Capture Pathway: HCs are directly captured by traps without transitioning through an intermediate cold carrier state [12] [35].

- Trap Depth Governs Cooling Rate: Deeper traps cause faster HC cooling, effectively reducing the hot phonon bottleneck effect and Auger reheating processes that would otherwise prolong HC lifetimes [12].

- Electronic Coupling: The overlap between the conduction band and trap states, along with the energy offset, determines trapping probability. Shallow traps in CsPbI3 have smaller electronic coupling with the conduction band compared to deeper traps in bromide-rich systems [12].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental difference in hot carrier dynamics between systems with shallow versus deep traps: