Surface Spectroscopy for Beginners: A Guide to Methods, Applications, and Optimization in Biomedical Research

This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of key surface spectroscopy techniques.

Surface Spectroscopy for Beginners: A Guide to Methods, Applications, and Optimization in Biomedical Research

Abstract

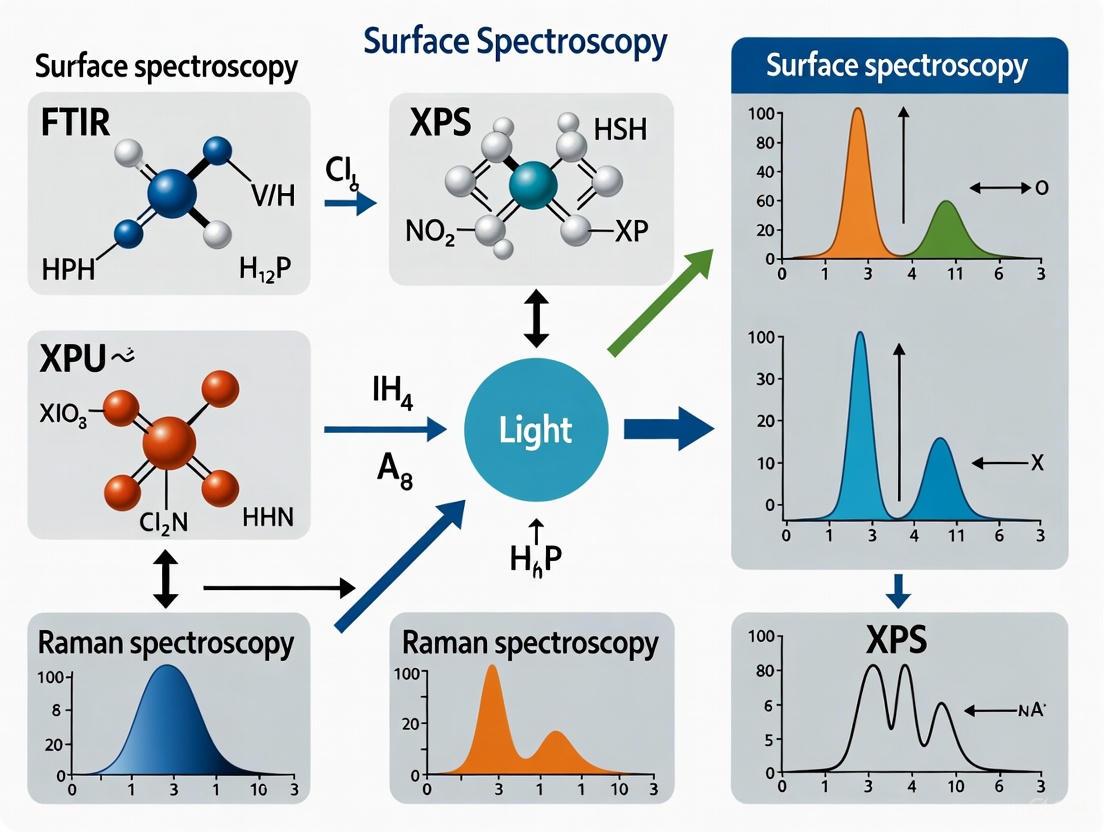

This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of key surface spectroscopy techniques. It explores the principles of methods like XPS, FT-IR, SERS, and SPR, detailing their specific applications in characterizing biomaterials and drug-delivery systems. The article offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common experimental challenges and provides a comparative framework for selecting the appropriate technique based on research goals. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical application, this resource aims to empower beginners to effectively utilize surface spectroscopy in biomedical and clinical research.

What is Surface Spectroscopy? Core Principles and Key Techniques for Beginners

Surface spectroscopy encompasses a suite of analytical techniques designed to determine the elemental composition, chemical state, and electronic structure of the outermost layers of a material, typically the top 1 to 10 nanometers [1]. This surface region is critically important because its properties can differ significantly from the bulk material, governing key behaviors in processes like corrosion, catalytic activity, and electrode function [2]. The core principle of these techniques is the detection of emitted particles—most commonly electrons or ions—after a surface is probed with a primary beam of photons, electrons, or ions [3]. Analyzing the energy and quantity of these emitted particles provides a fingerprint of the surface's chemical and physical state.

The fundamental challenge that surface spectroscopy overcomes is one of sensitivity and specificity. In a typical sample with a surface area of 1 cm², there are only about 10^15 atoms in the surface layer. Detecting an impurity present at just a 1% level requires a technique sensitive to about 10^13 atoms [2]. This level of sensitivity is beyond the capabilities of many common bulk analytical techniques. Furthermore, a surface-sensitive technique must successfully distinguish the weak signal from the surface atoms from the potentially overwhelming signal originating from the billions of layers of atoms in the bulk beneath [2].

Core Principles and Surface Sensitivity

The surface sensitivity of techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is not based on the probe's penetration depth, but rather on the short travel distance of the emitted electrons they detect. When a core-level electron is ejected, the resulting electron must travel through the solid to escape into the vacuum and be detected. These electrons can undergo inelastic scattering, losing energy in the process [3] [1].

The probability of an electron escaping without energy loss is highest for those originating very close to the surface. The average distance an electron can travel without losing energy is known as its inelastic mean free path (IMFP). IMFP values are very low for electrons with kinetic energies in the range of 10-1000 eV, typically corresponding to a distance of only 0.5 to 5 nanometers [1] [2]. This short escape depth effectively confines the analytical information to the top few atomic layers, making these techniques inherently surface-sensitive.

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of how the short IMFP of electrons confers surface sensitivity.

The relationship between the detected electron signal and the depth from which it originates can be quantified. The signal intensity, I, from a depth d follows an exponential decay relationship:

I = I0 exp(-d / λ)

where I0 is the intensity from the surface and λ is the IMFP [2]. This means that approximately 63% of the detected signal originates from within the top layer of thickness λ, and 95% from within a depth of 3λ. This mathematical relationship allows for the calculation of surface film thicknesses and is the foundation of depth profiling experiments, where sequential layers are removed (e.g., by ion sputtering) to reveal the composition as a function of depth [2].

Key Surface Spectroscopy Techniques

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), uses a beam of X-rays to eject core-level electrons from a sample [3]. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is measured, and their binding energy is calculated using the equation:

EKE = hν - EBE - Φ

where EKE is the electron's kinetic energy, hν is the energy of the X-ray photon, EBE is the electron's binding energy, and Φ is the spectrometer's work function [3]. The binding energy is a characteristic of the element and its chemical state, allowing XPS to provide both elemental identification and chemical state information [1]. Common X-ray sources are the Mg Kα line (1253.6 eV) and the Al Kα line (1486.6 eV) [3]. XPS has an information depth of typically 1-10 nm [1].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) can be initiated by either an electron beam or X-rays [3]. The process creates a core-level vacancy. When an electron from a higher energy level fills this vacancy, the excess energy can be released by ejecting a second electron, known as an Auger electron [3]. The kinetic energy of the Auger electron is characteristic of the element and is independent of the incident beam energy. AES is highly surface-sensitive, with an information depth of typically 0.5-5 nm, making it suitable for studying the topmost atomic layers [1]. It can provide high spatial resolution when combined with electron microscopy, enabling elemental mapping of small features [1].

Other Surface-Sensitive Techniques

While XPS and AES are the most common electron spectroscopies, other techniques provide complementary information:

- Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) uses UV light to probe the valence band and occupied electronic states near the Fermi level, providing information on the electronic structure, band gap, and work function with an information depth of 1-2 nm [1].

- Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) uses a primary beam of ions to sputter the surface, and the ejected secondary ions are analyzed by a mass spectrometer [3]. It is highly sensitive and provides elemental and molecular information from the outermost surface.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Surface Spectroscopy Techniques

| Technique | Primary Probe | Detected Signal | Information Depth | Primary Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS (ESCA) | X-ray photons | Photoelectrons | 1 - 10 nm [1] | Elemental composition, chemical states [1] |

| AES | Electrons or X-rays | Auger electrons | 0.5 - 5 nm [1] | Elemental composition, chemical states [1] |

| UPS | UV photons | Photoelectrons | 1 - 2 nm [1] | Valence band structure, work function [1] |

| SIMS | Ions | Sputtered ions | < 1 nm (top monolayer) [3] | Elemental and molecular composition, isotopic ratios |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Extracting meaningful information from surface spectra requires a rigorous approach to data processing. Key steps include background subtraction, peak fitting, and data normalization [1].

- Background Subtraction: The measured signal includes a background from inelastically scattered electrons that have lost energy. This background must be removed to reveal the true peak shapes and intensities. Common methods are the Shirley and Tougaard backgrounds, which account for the increasing background on the higher binding energy (lower kinetic energy) side of peaks [3] [1].

- Peak Fitting and Decomposition: Core-level peaks from different chemical states often overlap. Peak fitting is used to deconvolute these overlapping peaks into individual components using Gaussian, Lorentzian, or Voigt line shapes. Constraints based on prior knowledge (e.g., fixed peak separation, spin-orbit splitting ratios) are applied to ensure a physically meaningful result [1].

- Data Normalization: To compare spectra from different samples or instruments, normalization is essential. This can involve scaling to the total signal intensity, a specific core-level peak (e.g., C 1s), or the background level at a certain energy [1].

The process from data acquisition to interpretation follows a logical workflow, illustrated below for a generic surface analysis.

Quantification of elemental composition is achieved by comparing the intensity of characteristic peaks (areas after background subtraction and peak fitting) and applying relative sensitivity factors that account for photoionization cross-sections and instrument transmission [1]. Chemical state identification is performed by analyzing binding energy shifts; for example, the binding energy for an element in its oxide form is typically higher than in its metallic state [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A Standard XPS Analysis Protocol

- Sample Preparation and Mounting: The solid sample is securely mounted on a sample holder using conductive tape or a metal clamp to ensure electrical and thermal contact. Powdered samples may be pressed into a soft metal foil like indium [1].

- Sample Introduction and Vacuum Pump-Down: The sample holder is transferred into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) introduction chamber. The chamber is pumped down to a pressure typically below 10-8 mbar to minimize surface contamination from the atmosphere [1].

- In-Situ Surface Cleaning (If Required): To remove ubiquitous atmospheric contamination (e.g., adventitious carbon, native oxides), surface cleaning may be performed inside the UHV system. Common methods include Ar+ ion sputtering (physical removal of surface layers) or thermal annealing (to desorb contaminants or order the surface) [1].

- Spectrometer Calibration: The energy scale of the spectrometer is calibrated using a standard reference material, most commonly the Au 4f7/2 peak at a binding energy of 84.0 eV [1].

- Data Acquisition:

- Survey Scan: A wide energy range scan (e.g., 0-1100 eV binding energy) is acquired first to identify all elements present on the surface [3].

- High-Resolution Regional Scans: Narrow energy ranges covering the core-level peaks of identified elements (e.g., C 1s, O 1s, Fe 2p) are acquired with higher energy resolution to enable chemical state analysis [1].

- Data Processing and Analysis:

- Background Subtraction: Apply a Shirley or Tougaard background to all core-level peaks [1].

- Peak Fitting: Decompose the high-resolution spectra using appropriate line shapes and constraints to quantify the contributions of different chemical states [1].

- Quantification: Calculate atomic concentrations using the peak areas and relative sensitivity factors.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Surface Spectroscopy

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Conductive Tapes & Mounting Clamps | Provides electrical and thermal contact between the sample and holder, crucial for preventing charging on insulating samples [1]. |

| Metal Foils (Indium, Gold) | Used as substrates for pressing powdered samples into a stable pellet for analysis. Gold foil is also used for energy scale calibration [1]. |

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | The source gas for generating the Ar+ ion beam used for in-situ surface cleaning and depth profiling via sputtering [1]. |

| Calibration Standards (e.g., Au, Cu, Ag) | Certified reference materials with known peak positions used to calibrate the binding energy scale of the spectrometer, ensuring data accuracy [1]. |

| UHV-Compatible Sample Holders | Specialized metal stubs or plates designed to hold samples securely while withstanding ultra-high vacuum conditions. |

Applications in Energy and Materials Research

Surface spectroscopy is a driving force in modern energy and materials research. In the development of lithium-ion batteries, XPS is used extensively to analyze the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer that forms on electrode surfaces, understanding its composition and how it evolves during charging cycles to improve battery efficiency and longevity [4]. It is also vital for studying catalyst degradation and regeneration in hydrogen production and carbon capture applications [4].

The technique is equally important in fuel cell research, where it helps characterize the surface composition and chemical states of electrocatalysts, providing insights into reaction mechanisms and degradation pathways [4]. Furthermore, surface spectroscopy supports the development of solar cells by monitoring the optical properties and degradation of photovoltaic components, helping manufacturers design more durable and efficient solar panels [4].

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its power, surface spectroscopy has several important limitations that researchers must consider:

- Charging Effects: Non-conducting or poorly conducting samples can accumulate charge when probed with X-rays or electrons, leading to shifts in peak positions and distorted spectra. This is typically mitigated using an electron flood gun or by applying thin conductive coatings, though the latter is not always desirable [1].

- Beam-Induced Damage: The incident X-ray or electron beam can alter sensitive surfaces, particularly organic, polymeric, or biological materials. This damage can change the surface composition and chemical states during measurement, requiring careful control of the beam dosage [1].

- Spectral Overlap and Resolution: Closely spaced or overlapping peaks from different elements or chemical states can complicate quantification and interpretation. The ability to resolve these peaks is limited by the natural linewidth of core-level transitions and the energy resolution of the spectrometer [1].

- Sample Heterogeneity: If a sample's surface is not uniform, a single measurement may not be representative. This necessitates multiple measurements across the surface or the use of mapping techniques to capture the true nature of the surface [1].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is a highly surface-sensitive, quantitative technique that measures the elemental composition, empirical formula, and chemical and electronic states of elements within a material [5]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of XPS, framing its principles and methodologies for researchers beginning their exploration of surface spectroscopy.

Core Principles of XPS

XPS operates on the fundamental principle of the photoelectric effect. The technique involves irradiating a solid sample with a beam of X-rays in an ultra-high vacuum environment while simultaneously measuring the kinetic energy of electrons ejected from the top 1–10 nm of the material [5] [6].

The core equation in XPS is: Binding Energy (BE) = hν - Kinetic Energy (KE) - Φ where hν is the energy of the incident X-ray photon, and Φ is the work function of the spectrometer [7]. Each element produces a unique set of photoelectron peaks at characteristic binding energies, enabling identification. Furthermore, slight shifts in these binding energies—known as chemical shifts—occur due to the chemical environment of the atom (e.g., oxidation state, type of chemical bond), providing a powerful means for chemical state analysis [7] [6].

XPS Imaging and Chemical State Mapping

While often used for point analysis, XPS can be extended to image the surface of a sample, revealing the distribution of chemistries across a surface, locating contamination, or examining the thickness variation of ultra-thin coatings [8]. There are two primary approaches for obtaining XPS images, each with distinct advantages.

Serial Acquisition (Mapping)

This method is based on acquiring a two-dimensional, rectangular array of small-area XPS analyses [8]. The sample stage is scanned to move the specimen surface with respect to the fixed analysis position.

- Spatial Resolution: Defined by the X-ray spot size, which can be as small as 10 μm [8].

- Data Acquisition: A spectrum (or 'snapshot' spectrum) can be collected at each pixel [8] [9].

- Field of View: Can be very large (e.g., up to 60 x 60 mm), limited only by the stage's range of motion [9].

Parallel Acquisition (Imaging)

This method simultaneously images the entire field of view using additional electron optics and a two-dimensional detector without scanning the specimen [8].

- Speed and Resolution: Faster than serial methods for producing an image at a single energy and provides the best possible imaging resolution [8].

- Data Acquisition: A chemical image is constructed by tuning the energy analyzer to the kinetic energy of a specific photoelectron peak [8]. To obtain spectral data, a series of images must be collected at different energies [8].

The table below summarizes a comparison of these two imaging modes.

| Feature | Serial Acquisition (Mapping) | Parallel Acquisition (Imaging) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Stage is scanned to collect a rectangular array of points [8]. | Entire field of view is imaged simultaneously using a 2D detector [8]. |

| Spatial Resolution | Determined by X-ray spot size (e.g., 10 μm) [8]. | Determined by spherical aberrations in the electron lenses [8]. |

| Spectral Information | 'Snapshot' spectrum can be acquired at every pixel [9]. | Collects a single energy; requires energy scanning for full spectra [8]. |

| Best For | Quantitative chemical state mapping over large areas [9]. | High-resolution, fast imaging at a single energy [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: Chemical State Mapping of a Polymer

The following detailed methodology, adapted from a study on polymer analysis, illustrates a typical workflow for chemical state mapping using serial acquisition [9].

Sample Preparation

A copper grid was fixed to a silicon substrate coated with an acrylic acid plasma polymer. The substrate was then placed in a plasma containing a fluorocarbon monomer, causing fluorocarbon polymer to form on the exposed areas. After plasma exposure, the copper grid was removed, leaving behind a patterned polymeric fluorocarbon film on the substrate [9].

Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

- Instrument: Thermo Scientific K-Alpha XPS System.

- X-ray Spot Size: 30 μm.

- Data Collection: Snapshot XPS spectra for C 1s and F 1s peaks were collected into 64 channels for each element.

- Mapping: The sample stage was scanned over an array of 67 x 94 pixels with a step size of 10 μm. A spectrum was acquired at each pixel [9].

Data Processing and Image Construction

- Spectral Summation: The C 1s signal from every pixel in the image was summed to generate an average, high signal-to-noise spectrum.

- Peak Fitting: The summed C 1s spectrum was peak-fitted to identify the different chemical species present (e.g., hydrocarbon vs. fluorocarbon), as shown in the figure below [9].

- Peak 1: Binding energy of 284.7 eV (Hydrocarbon, C-C/C-H)

- Peak 2: Binding energy of 291 eV (Fluorocarbon, C-F)

- Map Generation: Images were constructed by displaying the signal intensity at specific binding energies.

- A map for hydrocarbon was created from the signal at 284.7 eV.

- A map for fluorocarbon was created from the signal at 291 eV.

- An overlay of these images clearly shows the spatial distribution of the two chemical states, corresponding to the grid pattern [9].

- Quantitative Mapping: The same set of peaks from the peak fit was applied to every spectrum in the map, allowing for the creation of atomic concentration maps for each chemical component [9].

- Thickness Mapping: Using an "Overlayer Thickness Calculator" in the data system and assuming bulk polymer densities, a thickness map of the fluorocarbon layer was constructed non-destructively [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key components used in the featured XPS experiment and their general functions in the field [9].

| Item | Function in Experiment / General Application |

|---|---|

| Silicon Substrate | Provides a flat, conductive, and easily handled base for supporting the sample being analyzed [9]. |

| Acrylic Acid Plasma Polymer | Served as a model polymer substrate with a known chemical composition (hydrocarbon/ester) for contrast [9]. |

| Fluorocarbon Monomer | Used to deposit a second, chemically distinct polymer (fluorocarbon) for creating a patterned surface [9]. |

| Copper Grid | A physical mask used to create a well-defined pattern of coated and uncoated regions during sample preparation [9]. |

| Charge Compensation System (Electron Flood Gun) | Essential for neutralizing positive surface charge that builds up on electrically insulating samples during analysis, preventing distorted spectra [5]. |

| Monatomic/Gas Cluster Ion Source | Used for depth profiling by sputtering away material layer-by-layer to reveal in-depth composition [5]. |

Applications and Best Practices

Key Applications in Research and Industry

XPS is a versatile technique with critical applications across multiple fields:

- Contamination Analysis: Detecting and quantifying trace surface contaminants (e.g., oils, residues) that can impair processes like adhesion or soldering [6].

- Adhesion Studies: Analyzing the top molecular layers to understand and improve the bonding of adhesives, coatings, and paints [6].

- Oxidation and Corrosion Studies: Measuring surface oxide layers and their composition, such as determining the passivation integrity of stainless steel by calculating the chromium-to-iron ratio [7].

- Thin Film and Coating Analysis: Assessing the uniformity, chemistry, and thickness of thin films, from ultra-thin polymer layers to functional coatings [9].

Avoiding Common Errors

A significant body of literature addresses persistent errors in XPS data collection and analysis [10]. Key considerations include:

- Peak Fitting: Avoid over-fitting spectra with too many components. Peak fits should be constrained by chemical knowledge and supported by high-quality, high-resolution data [10].

- Charge Referencing: Use a reliable and well-documented method for correcting binding energy shifts in insulating samples (e.g., the C 1s peak for adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV) [10].

- Reporting: Always report critical instrument parameters (X-ray source, pass energy, step size) and peak fitting details (background type, constraints) to ensure the reproducibility and credibility of your analysis [10].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy is an indispensable tool for the quantitative and chemical-state analysis of material surfaces. Its capabilities, extending from point analysis to chemical state mapping and depth profiling, make it vital for fundamental research and solving practical industrial problems. For researchers beginning their journey in surface spectroscopy, a rigorous approach to data acquisition, analysis, and reporting is fundamental to leveraging the full power of XPS.

Vibrational spectroscopy encompasses a suite of analytical techniques that probe the characteristic vibrational modes of molecules, providing a unique molecular fingerprint for chemical identification and structural analysis. When infrared or visible light interacts with matter, molecules can absorb specific energies to excite vibrational transitions or scatter light with shifted frequencies, processes that form the basis for Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) and Raman spectroscopies, respectively [11] [12]. These techniques are invaluable across chemistry, materials science, and biomedicine because they are non-destructive, require minimal sample preparation, and provide direct information about molecular composition, structure, and interactions [11] [13]. The concept of a "molecular fingerprint" is paramount; just as a human fingerprint is unique to an individual, the collective vibrational pattern of a molecule's chemical bonds creates a spectral signature that can be used for its unambiguous identification [14] [12].

The term "fingerprint" is particularly apt for the mid-infrared region (4000 - 400 cm⁻¹), where complex coupled vibrations generate a unique pattern for every distinct chemical compound [11]. This review details three powerful vibrational spectroscopy methods: FT-IR as the core infrared absorption technique, Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) as a dominant modern sampling method for FT-IR, and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) as a powerful enhancement technique for Raman spectroscopy. Together, they offer complementary capabilities for obtaining molecular fingerprints across a vast range of applications, from the analysis of bulk pharmaceuticals to the trace detection of biomarkers for disease diagnosis [11] [12] [15].

Fundamental Principles

FT-IR Spectroscopy

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by molecules undergoing vibrational transitions. The fundamental principle involves the interaction of IR radiation with a sample, where specific frequencies are absorbed when their energy matches the energy required to excite a molecular vibration, such as stretching or bending of chemical bonds [14]. The absorbed frequencies are characteristic of specific functional groups and chemical structures within the molecule.

Modern FT-IR spectrometers employ an interferometer, typically of the Michelson design, which generates an interferogram by splitting the IR beam, sending it along two paths (one with a fixed mirror and one with a moving mirror), and then recombining them [13]. This interferogram, which encodes all spectral frequencies simultaneously, is then converted into a conventional intensity-versus-wavenumber spectrum using a Fourier Transform mathematical operation [13] [14]. This approach provides significant advantages over older dispersive instruments, including higher signal-to-noise ratio (Fellgett's or multiplex advantage), higher energy throughput (Jacquinot's advantage), and superior wavelength precision (Connes' advantage) [13].

Infrared absorption requires a change in the dipole moment of the molecule. Consequently, polar bonds like C=O, O–H, and N–H are strong IR absorbers, while non-polar bonds such as those in homonuclear diatomic molecules (N₂, O₂) are IR-inactive [13]. A typical IR spectrum is plotted with wavenumber (cm⁻¹) on the x-axis and either absorbance or transmittance on the y-axis, providing a visual representation of the molecular fingerprints [11].

ATR Sampling Technique

Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) is the most common sampling technique for FT-IR spectroscopy due to its simplicity and minimal sample preparation requirements [14] [16]. The core of ATR involves directing the IR beam through a crystal with a high refractive index (e.g., diamond, ZnSe, or Ge) such that it undergoes total internal reflection [11] [16].

At each point of internal reflection, an evanescent wave penetrates a short distance (typically 0.5-2 µm) beyond the crystal surface into the sample in contact with it [17] [16]. This evanescent field is absorbed by the sample, generating the IR spectrum. The penetration depth depends on the wavelength, the refractive indices of the crystal and the sample, and the angle of incidence [16]. Because the evanescent wave only probes the very surface of the sample, ATR is ideal for analyzing solids, liquids, pastes, and gels without the need for extensive preparation like grinding or pellet-making, which are required for traditional transmission measurements [14] [17]. This makes ATR a virtually universal, non-destructive, and rapid sampling method.

SERS Enhancement Mechanism

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) is a powerful enhancement technique that overcomes the inherent weakness of normal Raman scattering, where only about 1 in 10 million photons is inelastically scattered [18] [12]. SERS can enhance the Raman signal by factors as large as 10¹⁰ to 10¹⁵, enabling single-molecule detection [18]. The enhancement arises from two primary mechanisms:

- Electromagnetic Enhancement: This is the dominant contributor (up to 10¹⁰). When laser light illuminates a nanostructured metallic surface (typically gold or silver), it can excite collective oscillations of conduction electrons, known as localized surface plasmon resonances [18] [12]. This creates a greatly enhanced electromagnetic field at the surface. When a molecule is located within this enhanced field (within 1-10 nm), both the incident laser field and the Raman scattered field are amplified. The highest enhancements occur at "hot spots," such as gaps between nanoparticles or at sharp tips, where the electromagnetic fields are most intense [19] [18].

- Chemical Enhancement: This mechanism provides a smaller contribution (typically 10²-10⁴). It involves a modification of the molecule's polarizability due to charge transfer between the molecule and the metal surface. This effect is short-range, acting over angstroms, and depends on the specific chemical interaction between the analyte and the substrate [18].

SERS requires the analyte to be in close proximity to a nano-textured metal surface, and the choice of substrate—including its material, morphology, and size—is critical for obtaining strong, reproducible signals [19] [18].

Experimental Protocols

ATR-FTIR Analysis Protocol

ATR-FTIR is renowned for its straightforward and rapid sample analysis. The following protocol is suitable for a wide range of solid and liquid samples.

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Procedure

Instrument Warm-up and Setup: Power on the FT-IR spectrometer and allow it to warm up for the manufacturer's recommended time (typically 15-30 minutes). Ensure the instrument is purged with dry air or nitrogen to minimize spectral contributions from atmospheric CO₂ and water vapor [13].

ATR Crystal Inspection and Cleaning: Visually inspect the ATR crystal (commonly diamond) for any residue or damage. Clean the crystal thoroughly by wiping with a soft cloth moistened with a suitable solvent (e.g., isopropanol or acetone), followed by a dry wipe. Allow any residual solvent to evaporate completely [16].

Background Spectrum Acquisition: Collect a background spectrum with a clean, dry ATR crystal. This spectrum will record the instrument response and atmospheric contributions, which will be automatically subtracted from the sample spectrum. The background should be acquired with the same number of scans and resolution as will be used for the sample [13] [14].

Sample Preparation and Loading:

- For Solid Samples: Place a small amount of the solid directly onto the ATR crystal. Use the instrument's pressure clamp to apply firm, even pressure to ensure good contact between the sample and the crystal. The sample should fully cover the crystal surface [14] [16].

- For Liquid Samples: Deposit a small droplet onto the crystal, ensuring it covers the measurement area. For volatile liquids, a sealed liquid cell accessory may be necessary.

Spectral Acquisition: Acquire the sample spectrum. Standard parameters are:

Post-measurement Cleaning: Carefully remove the sample and clean the ATR crystal thoroughly as described in Step 2 to prevent cross-contamination.

Data Processing: Process the raw spectrum using the instrument's software. Key steps include:

- Applying an ATR correction algorithm to compensate for the variation in penetration depth with wavelength, making the spectrum visually comparable to a transmission spectrum [14] [16].

- Performing a baseline correction to remove any sloping background.

- Peak picking and analysis by comparing the positions and intensities of absorption bands to reference libraries or known standards [11] [13].

SERS Substrate Preparation and Measurement Protocol

This protocol describes the preparation of a simple colloidal nanoparticle SERS substrate and its use for analyzing a model analyte.

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Procedure

Synthesis of Colloidal Nanoparticles (Citrate-reduced Gold Nanoparticles):

- Prepare a 0.25 mM solution of hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (HAuCl₄) in ultrapure water.

- Bring the solution to a rolling boil under vigorous stirring in a round-bottom flask equipped with a condenser.

- Rapidly add a pre-calculated volume of a 1% (w/v) trisodium citrate solution. The ratio of citrate to gold salt determines the final nanoparticle size [19] [18].

- Continue heating and stirring for 15 minutes until the solution turns a deep red color, indicating nanoparticle formation.

- Allow the colloidal solution to cool slowly to room temperature while stirring. Characterize the nanoparticles using UV-Vis spectroscopy (should show a plasmon peak ~520-530 nm) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to determine size and monodispersity [19].

Sample Preparation for SERS:

- Colloid-Based Method: Mix the analyte solution (e.g., 10 µL of a 1 µM solution) with the gold colloid (e.g., 90 µL). To induce mild aggregation and create more "hot spots," add an aggregating agent like potassium nitrate or nitric acid (e.g., 10 µL of 0.1 M KNO₃). Mix gently and incubate for 1-5 minutes to allow analyte adsorption onto the metal surface [18].

- Solid Substrate Method: Alternatively, deposit a droplet of the nanoparticle colloid onto a clean silicon or glass slide and allow it to dry. Then, deposit a droplet of the analyte solution onto the dried nanoparticle film and allow it to dry [19].

SERS Spectral Acquisition:

- Load the prepared SERS sample onto the stage of the Raman spectrometer.

- Select Laser Excitation: Choose a laser wavelength that matches the plasmon resonance of the substrate. For gold nanoparticles, 532 nm, 633 nm, or 785 nm lasers are commonly used [18] [12].

- Optimize Power and Focus: Use a low laser power (e.g., 0.1-5 mW at the sample) to avoid thermal degradation. Carefully focus the laser beam onto the sample.

- Set Acquisition Parameters: Use an integration time of 1-10 seconds and accumulate 1-10 scans to obtain a spectrum with good signal-to-noise.

- Acquire the SERS spectrum.

Data Analysis and Validation:

- Process the raw spectrum by applying a fluorescence background subtraction and cosmic ray removal.

- Compare the SERS spectrum to a normal Raman spectrum of the same analyte at a much higher concentration. The SERS spectrum should show the same characteristic vibrational bands but with dramatically increased intensity. Note that relative band intensities may differ between normal Raman and SERS due to the surface selection rules [18].

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in vibrational spectroscopy requires specific materials and reagents tailored to each technique. The table below summarizes the essential components of a research toolkit.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals [17] [16] | Internal reflection element for ATR-FTIR sampling. | Diamond: Hard, chemically inert, universal use. ZnSe: Good for liquids and soft solids; avoid acids/bases. Ge: High refractive index for surface analysis of strong absorbers. |

| FT-IR Calibration Standards [13] | Verify wavenumber accuracy and photometric linearity of the FT-IR spectrometer. | Polystyrene film is a common standard for routine checks. |

| Metal Salts [19] [18] | Precursors for SERS-active nanoparticle synthesis. | HAuCl₄ (Gold) and AgNO₃ (Silver) are most common. |

| Reducing & Capping Agents [19] [18] | Control nucleation, growth, and stability of nanoparticles during synthesis. | Trisodium Citrate: Common reducing/capping agent for Au/Ag. Ascorbic Acid: A reducing agent used in "bottom-up" syntheses. |

| SERS Solid Substrates [19] [18] | Commercial off-the-shelf platforms for SERS measurements. | Pre-fabricated nanostructured gold or silver films, chips, or wires. Offer better reproducibility than lab-made colloids. |

| Probe Molecules [18] | Used to test and validate the enhancement performance of SERS substrates. | 4-Nitrothiophenol (4-NTP) or Rhodamine 6G are frequently used. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Band Assignment in IR and Raman Spectra

Interpreting vibrational spectra involves assigning the observed peaks to specific vibrational modes of functional groups. The mid-IR region is divided into the Functional Group Region (4000-1500 cm⁻¹) and the Fingerprint Region (1500-400 cm⁻¹) [11]. The following table provides general guidance for band assignment, but note that exact positions can shift depending on the molecular environment.

Table 2: Characteristic Vibrational Band Assignments for Biomolecules

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Vibration Mode | Assignment / Biomolecule |

|---|---|---|

| ~3300 | ν(O-H) / ν(N-H) | Water, Carbohydrates, Proteins (Amide A) [11] |

| 3050 - 2800 | νₐₛ(C-H), νₛ(C-H) | Lipids, Fatty Acids [11] [15] |

| ~1740 | ν(C=O) | Ester carbonyl in Lipids [11] |

| 1650 - 1640 | ν(C=O), δ(N-H) | Amide I (Proteins) [11] [15] |

| 1550 - 1530 | δ(N-H), ν(C-N) | Amide II (Proteins) [11] [15] |

| 1450 - 1450 | δₐₛ(CH₃) | Proteins, Lipids [15] |

| 1390 - 1380 | δₛ(CH₃) | Proteins, Fatty Acids [15] |

| 1240 - 1230 | νₐₛ(P=O) | Phosphodiester groups in DNA/RNA [11] [15] |

| 1170 - 1000 | ν(C-O), ν(C-C) | Carbohydrates (e.g., glycogen) [11] |

| 1080 - 1060 | νₛ(P=O) | Phosphodiester groups in DNA/RNA [11] [15] |

ν: stretching; δ: bending; νₐₛ: asymmetric stretch; νₛ: symmetric stretch.

For SERS, the same fundamental vibrations are observed as in normal Raman spectroscopy. However, bands associated with vibrational modes closest to the metal surface or involved in charge-transfer are often preferentially enhanced, which can alter the relative peak intensities compared to a normal Raman spectrum [18].

Chemometric Analysis for Complex Data

Spectral data from complex mixtures, such as biological fluids (blood, saliva) or polymer blends, can be challenging to interpret by visual inspection alone due to overlapping bands. Chemometrics uses multivariate statistical methods to extract meaningful information from such spectral datasets [15].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): An unsupervised method used for exploratory data analysis. It reduces the dimensionality of the data (thousands of wavenumber points) to a few principal components (PCs) that capture the greatest variance. Scores plots of the first few PCs can reveal natural clustering or outliers in the data, such as separating healthy from diseased samples based on their biochemical composition [15].

- Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): A supervised method used for classification. It finds the linear combinations of variables (wavenumbers) that best separate predefined classes. LDA can build models to classify unknown samples into specific categories (e.g., cancer vs. control) with high sensitivity and specificity, as demonstrated in gastric cancer detection from biofluids [15].

- Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS-R): A supervised method used for quantitative analysis. It correlates spectral data (X-matrix) with reference concentration values (Y-matrix) to build a calibration model. This model can then predict the concentration of an analyte in an unknown sample [17].

Applications in Research and Development

The applications of FT-IR, ATR, and SERS are vast and cross-disciplinary, particularly leveraging their fingerprinting capabilities.

Biomedical Diagnostics and Cancer Detection: Vibrational spectroscopy is emerging as a powerful tool for disease diagnosis, especially in oncology. Studies have successfully used ATR-FTIR spectroscopy of biofluids (blood serum, plasma, saliva) combined with LDA to discriminate gastric cancer cases from controls with 100% accuracy in research settings [15]. SERS's extreme sensitivity allows for the detection of trace-level cancer biomarkers, enabling early diagnosis and the monitoring of treatment efficacy [11] [12].

Pharmaceutical Quality Control and Drug Development: FT-IR is routinely used for raw material identity testing, quality control of final products, and monitoring solid-state forms (polymorphs) of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [11] [17]. ATR-FTIR can also verify the successful immobilization of active molecules onto drug-delivery matrices, such as catheter coatings [13].

Polymer and Materials Science: These techniques are indispensable for characterizing polymer composition, crystallinity, degradation, and surface modification. For example, FT-IR curve-fitting methods can determine the crystallinity of polymers like poly(ε-caprolactone), and monitor oxidation in reclaimed asphalt binders [13].

Environmental Monitoring and Analysis: FT-IR is used for open-path monitoring of atmospheric gases (CO₂, CH₄, O₃) and for the identification and quantification of microplastics in environmental samples using µ-FT-IR imaging [13].

Catalysis and Surface Science: Operando FT-IR and SERS are used to probe adsorbed species, identify active sites, and monitor reaction intermediates on catalyst surfaces, providing crucial insights into reaction mechanisms [13]. SERS substrates made from anisotropic nanomaterials like nanostars or nanocubes are particularly effective due to their high density of electromagnetic "hot spots" [19].

Comparison of Techniques

Table 3: Comparison of Key Vibrational Spectroscopy Techniques

| Parameter | ATR-FTIR | Transmission FTIR | SERS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; non-destructive [14] [16] | Extensive; often destructive (grinding, pressing) [14] | Moderate; requires substrate and analyte adsorption [18] |

| Typical Analysis Depth | Shallow (0.5 - 2 µm) [16] | Through entire sample (µm to mm) | Surface-sensitive (nm scale) [18] |

| Sensitivity | Excellent for bulk analysis | Excellent for bulk analysis | Extremely high; single-molecule level possible [18] |

| Aqueous Compatibility | Good (water has strong absorption) | Poor (strong water absorption) | Excellent (weak Raman scattering from water) [11] [18] |

| Quantitative Reproducibility | High (with good crystal contact) [11] | High (with careful preparation) | Can be challenging (depends on substrate homogeneity) [18] |

| Key Strength | Ease of use, versatility, rapid analysis | Standardized libraries, quantitative accuracy | Ultra-high sensitivity, bio-compatibility |

| Key Limitation | Limited to surface/near-surface analysis | Time-consuming sample preparation | Reproducibility and cost of substrates |

FT-IR, ATR, and SERS represent a powerful trio of vibrational spectroscopy techniques that provide comprehensive molecular fingerprinting capabilities. ATR-FTIR stands out for its unmatched simplicity and robustness for routine analysis of a vast array of sample types, making it an essential workhorse in modern laboratories. In contrast, SERS offers unparalleled sensitivity down to the single-molecule level, opening up possibilities for trace analysis and detection that were previously unimaginable with conventional Raman spectroscopy.

The choice of technique is dictated by the specific analytical question: ATR-FTIR for rapid, non-destructive bulk analysis, and SERS for ultra-sensitive, surface-specific detection, particularly in aqueous environments. For the beginner researcher, mastering ATR-FTIR provides a solid foundation in vibrational spectroscopy, while venturing into SERS offers a pathway to cutting-edge research in nanotechnology and sensing. As these technologies continue to evolve, particularly through integration with advanced chemometrics and machine learning, their impact is set to grow further, bridging the gap between fundamental molecular spectroscopy and real-world problem solving across medicine, industry, and environmental science.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful label-free optical technique used to study biomolecular interactions in real time. The phenomenon occurs when plane-polarized light hits a thin metal film (typically gold) under conditions of total internal reflection [20] [21]. This incident light excites surface plasmons, which are collective oscillations of free electrons at the metal-dielectric interface, leading to a characteristic drop in the reflected light intensity at a specific resonance angle [22] [21].

The core sensing principle relies on the fact that the resonance angle is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index within approximately 200 nanometers of the metal surface [23] [21]. When a biomolecule binds to a ligand immobilized on this surface, the local refractive index changes, causing a measurable shift in the resonance angle [20] [22]. This shift, recorded in resonance units (RU), is directly proportional to the mass concentration of molecules bound to the surface, enabling researchers to monitor binding events as they happen without the need for fluorescent or radioactive labels [20].

Instrumentation and Core Components

A typical SPR instrument consists of three primary subsystems that work in concert to enable sensitive detection.

Optical Detection System

The optical system includes a monochromatic, polarized light source and a photodetector. The most common configuration is the prism-coupled system (Kretschmann configuration), where light passes through a high-refractive-index prism to generate the evanescent wave that excites surface plasmons in the metal film [22]. The detector measures the intensity of reflected light as a function of the incident angle, identifying the precise angle of resonance attenuation [20] [22].

Sensor Chip

The sensor chip forms the foundation for molecular interactions. It typically consists of a glass substrate coated with a thin gold layer (approximately 50 nm) [22]. This gold surface is often derivatized with a polymer matrix or chemical functional groups to facilitate the immobilization of ligand molecules through various chemistries, including amine, thiol, aldehyde, or carboxyl coupling [22] [24]. Specialized surfaces exist for capturing specific tags, such as biotin, histidine tags, or glutathione-S-transferase fusion proteins [22].

Microfluidic System

The microfluidic system precisely delivers buffer solutions and analyte samples over the sensor surface. It ensures uniform sample distribution and laminar flow, which is critical for obtaining reliable kinetic data [25]. Modern systems may use traditional flow channels or innovative technologies like digital microfluidics (DMF) that manipulate nanoliter-sized droplets for enhanced efficiency and reduced sample consumption [26].

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of a standard SPR experiment, from surface preparation to data interpretation:

Sensorgram Interpretation

The real-time data output from an SPR experiment is called a sensorgram, which plots the response (RU) against time [20] [24]. A typical sensorgram displays several distinct phases:

- A. Baseline: Established with a continuous flow of running buffer, providing a stable reference signal [21].

- B. Association Phase: Begins when analyte is injected over the immobilized ligand. The increase in response signal indicates binding and complex formation [21]. The slope of this curve depends on the analyte concentration and the association rate constant [21].

- C. Equilibrium Plateau: Represents the dynamic balance between association and dissociation rates, where the net binding signal remains constant [21].

- D. Dissociation Phase: Initiated by switching back to running buffer alone. The decrease in signal reflects the dissociation of the analyte-ligand complex [21].

- E. Regeneration Phase: An optional step where a solution is injected to remove any remaining bound analyte, restoring the surface for a new experiment [22] [21].

Quantitative Parameter Extraction

SPR data provides rich quantitative information about molecular interactions, which can be modeled using appropriate binding equations:

Kinetic Analysis: The interaction between a ligand (L) and analyte (A) forming a complex (LA) is described by: ( L + A \rightleftharpoons[ kd ]{ ka } LA ) [21]

The sensorgram data is fitted to determine:

- Association rate constant (kₐ or kₒₙ): Measured in M⁻¹s⁻¹, describes how quickly the complex forms [21].

- Dissociation rate constant (kḍ or kₒff): Measured in s⁻¹, describes how quickly the complex dissociates [21].

Affinity and Thermodynamics:

- Equilibrium dissociation constant (KD): Calculated as KD = kd/ka, expressed in molar units (M) [20] [21]. This value represents the analyte concentration required to occupy half the binding sites at equilibrium and is a direct measure of binding affinity.

- Thermodynamic parameters: By performing experiments at different temperatures, the change in free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) can be derived using the relationship: ΔG = -RT ln(KA) = ΔH - TΔS, where KA = 1/K_D [21].

Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful SPR experimentation requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table summarizes key components and their functions:

| Item | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips | Platform for immobilizing ligands; gold film enables plasmon resonance [20] [22] | Series S sensor chips (Cytiva); various surface chemistries (amine, carboxyl, streptavidin, NTA) [20] |

| Running Buffer | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength; reduces non-specific binding [20] | HBS-EP (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20); should include detergent like 0.05% Tween 20 [20] |

| Ligand & Analyte | Interacting molecules; ligand is immobilized, analyte is in solution [20] [24] | Proteins, antibodies, DNA, small molecules, lipids, carbohydrates [22] [24] |

| Immobilization Reagents | Facilitate covalent attachment or capture of ligand to sensor surface [22] | Amine coupling kit (NHS/EDC); thiol coupling reagents; capture surfaces (anti-His, streptavidin) [22] |

| Regeneration Solutions | Remove bound analyte without damaging immobilized ligand for surface reuse [22] | Mild acid (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.5-3.0) or base; high salt; chelating agents [22] |

| Instrument Cleaners | Maintain fluidic path and prevent contamination [20] | Desorb solutions (e.g., Desorb 1, Desorb 2); biadisinfectant [20] |

Advanced SPR Technologies and Applications

High-Throughput and Imaging SPR

Traditional SPR systems are limited in throughput, but recent advancements have addressed this challenge. SPR imaging (SPRi) utilizes a camera to simultaneously monitor resonance conditions across the entire sensor surface, enabling the parallel analysis of hundreds to thousands of interactions in microarray formats [23] [21]. This multiplexing capability is particularly valuable for epitope binning of therapeutic antibodies and large-scale interaction screening [27].

Digital microfluidics (DMF) represents another innovation, manipulating nanoliter droplets on the sensor surface instead of using traditional continuous flow. This approach, implemented in systems like the Alto Digital SPR, drastically reduces sample consumption and enables true high-throughput screening with minimal hands-on time [26].

Key Application Areas

SPR technology has enabled advanced applications across multiple domains of biological research and drug discovery:

- Therapeutic Antibody Discovery: High-throughput SPR allows researchers to rapidly characterize the kinetic and epitope diversity of large antibody libraries early in the discovery process, enabling better candidate selection and intellectual property positioning [27].

- Drug Serium Protein Binding: SPR can directly measure the binding of drug candidates to serum proteins (e.g., human serum albumin), providing critical early data on ADME/PK (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion/Pharmacokinetics) properties that determine bioavailability [26].

- Nanoparticle-Biomolecule Interactions: SPR is used to characterize the surface functionalization of nanoparticles and study their interactions with biological systems, supporting the rational design of drug delivery systems and diagnostic devices [25].

- Fragment-Based Drug Design (FBDD): The high sensitivity of modern SPR instruments enables detection of weak interactions (K_D in mM-μM range) from low-molecular-weight fragments, making it ideal for screening fragment libraries in early drug discovery [28].

Surface Plasmon Resonance has firmly established itself as a cornerstone technology for biomolecular interaction analysis. Its unique capabilities for real-time, label-free monitoring of binding events provide researchers with unparalleled access to kinetic, affinity, and concentration data. As SPR technology continues to evolve toward higher throughput, greater sensitivity, and increased accessibility through automation, its role in accelerating drug discovery and deepening our understanding of biological systems will only expand. For researchers beginning their journey in surface spectroscopy methods, SPR offers a powerful and versatile platform with applications spanning from basic research to clinical assay development.

Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) is a highly sensitive surface analytical technique that provides elemental and molecular information from the outermost layers of a sample. It operates on the principle of using a focused primary ion beam to sputter and ionize material from a solid surface, then analyzing the emitted secondary ions by their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) using a time-of-flight mass analyzer [29] [30]. This technique enables researchers to perform detailed surface composition analysis and depth profiling with exceptional chemical specificity.

The fundamental process involves several key steps: first, a pulsed primary ion beam strikes the sample surface, causing the emission of neutral atoms, molecules, and secondary ions. These secondary ions are then accelerated to a constant kinetic energy and travel through a field-free flight tube towards a detector. Since ions with lower mass achieve higher velocities than heavier ions with the same kinetic energy, they reach the detector first, allowing precise mass determination based on arrival time [30]. TOF-SIMS achieves remarkable sensitivity, with detection limits in the parts-per-million to parts-per-billion range, and can provide lateral resolution below 1 micrometer and depth resolution of several nanometers [31].

Principles and Instrumentation of TOF-SIMS

Core Components and Their Functions

A TOF-SIMS instrument consists of three essential subsystems that work in concert to generate surface chemical data. The configuration of these components creates a sophisticated analytical tool for surface characterization, as illustrated in the following workflow:

The ion source generates the primary ion beam that initiates the analytical process. Common primary ions include Biₙ⁺, Auₙ⁺, or C₆₀⁺ for analysis, while sputter ions like Cs⁺, Ar⁺, or Arₙ⁺ are used for depth profiling [32] [33]. The mass analyzer, specifically the time-of-flight design, separates ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio by measuring the time they take to travel a fixed distance. Lighter ions with the same charge arrive at the detector first, followed by heavier ions, creating a mass spectrum that displays m/z versus relative abundance [30]. This entire process occurs under ultra-high vacuum conditions (typically 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹⁰ mbar) to minimize interference from gas molecules and prevent surface contamination [30].

Operational Modes and Information Output

TOF-SIMS operates in three primary modes, each yielding distinct types of chemical information about the sample surface. In spectrometry mode, the technique identifies the elemental and molecular species present within the analysis area, producing a mass spectrum where each peak corresponds to a specific m/z value [29]. The imaging mode generates detailed two-dimensional maps showing the spatial distribution of specific chemical species across the sample surface, achieving sub-micrometer lateral resolution [31]. In depth profiling mode, the instrument alternates between data acquisition using a analysis ion beam and material removal using a separate sputter ion beam, enabling the reconstruction of three-dimensional chemical information as a function of depth [31] [32].

TOF-SIMS Depth Profiling Methodology

Fundamental Approach and Technical Considerations

Depth profiling TOF-SIMS enables the investigation of chemical composition beneath the sample surface by performing sequential cycles of surface analysis followed by material removal. Each cycle consists of a brief period of data acquisition using a low-current primary ion beam, followed by a longer period of surface erosion using a higher-current sputter ion beam [31] [32]. This process generates a series of secondary ion images that progressively sample deeper regions of the sample, which can be stacked and rendered to produce a three-dimensional chemical map [31].

The choice of sputter ion parameters significantly impacts depth resolution and the preservation of molecular information. Research on lithium metal surfaces has demonstrated that cluster ions like Ar₁₅₀₀⁺ with energies of 5-10 keV (approximately 3.33 eV per atom) cause minimal fragmentation and preserve molecular information, while monatomic ions like Cs⁺ and Ar⁺ with energies of 250 eV to 2 keV induce more fragmentation but offer higher sputter yields [32]. The selection of appropriate sputter conditions must balance the need for rapid material removal with the preservation of chemical integrity throughout the profiling process.

Advanced Correction Techniques for Accurate 3D Representation

When depth profiling contoured samples like intact cells, z-axis distortion occurs in 3D renderings because each TOF-SIMS image becomes a flat plane that doesn't conform to the sample's actual topography [31]. Advanced correction strategies have been developed to address this limitation. One approach uses total ion count (TIC) images collected during TOF-SIMS depth profiling to create a 3D morphology model of the cell's surface when each depth profiling image was acquired [31]. These models correct the z-position and height of each voxel in component-specific 3D TOF-SIMS images, resulting in more accurate representations of subcellular structures such as endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane (ER-PM) junctions [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Sputter Ions for TOF-SIMS Depth Profiling

| Sputter Ion | Energy Range | Fragmentation Level | Best Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ar₁₅₀₀⁺ (Cluster) | 5-10 keV total (∼3-7 eV/atom) | Low | Organic/polymeric materials, delicate structures | Preserves molecular information, lower sputter yield |

| Cs⁺ (Monatomic) | 250 eV - 2 keV | High | Inorganic materials, high sputter yield applications | Enhances negative ion yield, causes significant fragmentation |

| Ar⁺ (Monatomic) | 250 eV - 2 keV | Moderate | General purpose, positive and negative mode compatibility | No surface reduction/oxidation, balanced performance |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Detailed Methodology for Battery Interface Analysis

TOF-SIMS depth profiling provides powerful insights into solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layers on lithium metal electrodes, which is crucial for developing next-generation batteries. A representative experimental protocol involves:

Sample Preparation: Lithium metal sections are prepared under inert atmosphere to prevent atmospheric contamination. For SEI formation, a lithium metal rod is cut while immersed in an organic carbonate-based electrolyte, allowing spontaneous reaction between bare lithium and electrolyte to form the interphase layer [32].

Instrument Parameters: Analysis is performed using a TOF-SIMS instrument equipped with both analysis and sputter ion sources. Typical conditions include a Biₙ⁺ primary ion source for analysis, with a 30 kV accelerating voltage, 3 nA current, and 16 ns pulse width. For sputtering, Ar₁₅₀₀⁺ cluster ions at 5 keV with 500 pA current provide optimal balance between removal rate and chemical preservation for SEI layers [32].

Data Acquisition: Depth profiling begins at the native surface and proceeds through approximately 40 nm of material. 512 × 512 pixel images are collected over a 70 μm field of view, with tandem MS¹ and MS² data acquired at each pixel. Secondary ions characteristic of SEI components (LiF₂⁻, LiCO₃⁻, C₂H₃O⁻, LiO⁻) are monitored throughout the profile to track compositional changes with depth [32].

Data Processing: Secondary ion images are aligned using registration algorithms, with intensity normalization and 3×3 boxcar smoothing applied. Specific signals are assigned to chemical species based on mass accuracy and confirmed through MS/MS analysis when necessary [31] [32].

Biological Sample Analysis with Depth Correction

For biological applications such as mapping subcellular distributions of unlabeled metabolites, a specialized protocol enables 3D chemical imaging of intact cells:

Cell Preparation: Transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells expressing recombinant GFP-Kv₂.₁ fusion protein are cultured on silicon substrates and labeled with organelle-specific stains such as ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX, which produces distinctive fluorine secondary ions during TOF-SIMS analysis [31].

Imaging Parameters: Secondary ion images are acquired in unbunched mode with a 30 kV Biₙ⁺ liquid metal ion source operated at 3 nA current, 16 ns pulse width, and 8300 Hz repetition rate. Between depth profiling image acquisitions, a 5 keV Ar₂₅₀₀₀⁺ ion beam with 2.5 nA DC current sputters material from an 800 × 800 μm region [31].

Depth Correction Processing: Total ion count (TIC) images from each depth are converted to grayscale and compiled into a 3D matrix (512 × 512 × 127 cycles). After alignment and smoothing, the TIC intensity values are used to model sample height at each pixel position. These morphology models shift voxels in 3D TOF-SIMS images to correct z-position and height above the substrate, accurately rendering structures such as ER-PM junctions relative to surface topography features [31].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for TOF-SIMS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX | Organelle-specific staining for endoplasmic reticulum | Thermo Fisher Scientific product | Contains fluorine atoms that produce distinctive F⁻ secondary ions |

| Silicon Substrates | Sample support for biological specimens | Standard silicon wafers | Provides clean background, generates m/z 77 (SiO₃H⁻) substrate signal |

| Organic Carbonate Electrolyte | SEI formation on battery electrodes | Lithium battery electrolyte solution | Forms complex interphase with organic and inorganic components |

| Argon Cluster Ions | Sputter source for depth profiling | Ar₁₅₀₀⁺ at 5 keV | Low fragmentation, preserves molecular information during depth profiling |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Considerations

Mass Spectrum Analysis and Peak Assignment

Interpreting TOF-SIMS data requires understanding several characteristic features present in mass spectra. The molecular ion (M⁺• or [M+H]⁺) typically represents the intact molecule and provides the total molecular weight [34]. Fragment ions result from the breakage of chemical bonds during the ionization process and provide structural information about the molecule [30] [34]. Isotopic patterns arise from the natural abundance of heavier isotopes (particularly ¹³C at 1.07% abundance), with the M+1 peak height relative to the molecular ion peak providing information about the number of carbon atoms in the molecule [34].

For example, in the analysis of lithium metal SEI layers, specific secondary ions are assigned to chemical components: LiF₂⁻ represents lithium fluoride, LiCO₃⁻ indicates lithium carbonate, C₂H₃O⁻ corresponds to organic decomposition products, and LiO⁻ signifies lithium oxide [32]. The relative intensities and depth distributions of these signals reveal the layered structure of the SEI, with organic components typically dominating near the electrolyte interface and inorganic components prevailing closer to the lithium metal surface [32].

Technical Challenges and Limitations

Despite its exceptional sensitivity, TOF-SIMS faces several analytical challenges that researchers must address during experimental design and data interpretation. Matrix effects significantly influence secondary ion yields, where the chemical environment of an analyte can enhance or suppress its ionization efficiency by several orders of magnitude [32]. This complicates quantitative analysis without appropriate standard reference materials. The technique is also inherently destructive, as the primary ion beam permanently alters the analyzed area, though this is managed through careful selection of analysis conditions [29].

Topographical artifacts in 3D reconstructions present particular challenges for non-flat samples like intact cells, necessitating advanced correction algorithms based on total ion count images or secondary electron images [31]. Additionally, the complexity of mass spectra from heterogeneous samples can complicate interpretation, often requiring multivariate statistical analysis (MVSA) methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) to extract meaningful chemical information from the dataset [33].

TOF-SIMS has established itself as an indispensable technique for surface composition analysis and depth profiling across diverse fields including battery research, biological imaging, and materials characterization. Its unique capability to provide both elemental and molecular information from the outermost surface layers with high spatial resolution enables researchers to address fundamental questions in interfacial chemistry and heterogeneous material systems. The continuing development of cluster ion sources, improved mass resolution, advanced data extraction algorithms, and sophisticated 3D reconstruction methods will further expand applications of this powerful surface analysis technique.

For researchers embarking on TOF-SIMS investigations, careful attention to sample preparation, appropriate selection of primary and sputter ion parameters, implementation of corrective methodologies for topographic artifacts, and application of multivariate analysis tools are essential for generating reliable, interpretable data. As instrument manufacturers continue to refine hardware capabilities and software solutions, TOF-SIMS is poised to remain at the forefront of surface analytical techniques for characterizing complex material systems at the molecular level.

How to Apply Surface Spectroscopy: Techniques for Biomaterial and Drug Characterization

Characterizing Drug-Delivery Systems and Implant Surfaces with XPS and FT-IR

The efficacy and safety of modern drug-delivery systems and implantable medical devices are profoundly influenced by their surface properties. Surface characteristics dictate critical performance aspects, including drug release kinetics, biocompatibility, cellular responses, and long-term stability within the biological environment [35] [36]. Spectroscopic techniques have therefore become indispensable tools for the precise characterization of these properties. Among them, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy stand out for their ability to provide complementary molecular and elemental information from material surfaces. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of how these powerful analytical methods are applied to characterize advanced drug-delivery systems and implant surfaces, offering a foundational resource for researchers entering the field of biomaterials surface science.

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these techniques is essential for the rational design of next-generation medical devices. Implant-associated challenges, such as fibrotic capsule formation, can create diffusion barriers that compromise drug release profiles and sensor function [36]. Similarly, the uniform distribution of a drug on an implant surface is a critical factor for consistent therapeutic effect [35]. XPS and FT-IR provide the nanoscale insights required to understand and engineer surfaces that mitigate these issues, thereby improving clinical outcomes.

Fundamental Principles of XPS and FT-IR

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS, also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is a quantitative technique used to determine the elemental composition and chemical state of a material's surface. Its fundamental principle is based on the photoelectric effect [7]. When a sample is irradiated with X-rays, core electrons from the surface atoms absorb energy and are ejected as photoelectrons. The kinetic energy ((Ek)) of these emitted electrons is measured, allowing the calculation of their binding energy ((Eb)) using the equation: [Eb = h\nu - Ek - \phi] where (h\nu) is the energy of the incident X-ray photon and (\phi) is the work function of the spectrometer [7] [37].

- Surface Sensitivity: XPS is exceptionally surface-sensitive, probing only the top 1 to 10 nanometers of a material. This is because the emitted photoelectrons have a very short inelastic mean free path in solids [38] [7] [37].

- Information Obtained: An XPS spectrum plots the number of detected electrons versus their binding energy. Peaks in the spectrum identify the elements present (all except hydrogen and helium), and small shifts in the binding energy (chemical shifts) provide information about the chemical environment and oxidation state of those elements [38] [7].

- Data Output: The primary data includes survey scans for elemental identification and high-resolution scans for detailed chemical state analysis [7].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy probes the vibrational modes of molecules to identify functional groups and molecular structures. Molecules absorb infrared radiation at specific frequencies that correspond to the natural frequencies of their chemical bonds' vibrations, such as stretching and bending [39] [40].

- Molecular Fingerprint: The mid-infrared region (4000 - 400 cm⁻¹) provides a "molecular fingerprint" unique to the chemical composition and structure of the sample. The spectrum is typically divided into regions: single bonds (2500–4000 cm⁻¹), triple bonds (2000–2500 cm⁻¹), double bonds (1500–2000 cm⁻¹), and a fingerprint region (650–1500 cm⁻¹) [40].

- Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR): A common sampling technique, ATR-FTIR, allows for the direct analysis of solid and liquid samples with minimal preparation. It is particularly useful for studying surfaces, thin films, and biological samples [41] [39] [40].

- Information Obtained: An FT-IR spectrum reveals the specific functional groups (e.g., C=O, O-H, N-H) present in a material. Changes in peak position, intensity, or shape can indicate molecular interactions, such as drug-polymer bonding or surface modifications [39] [40].

The following table summarizes the core differences and complementary nature of these two techniques.

Table 1: Core Differences Between XPS and FT-IR Spectroscopy

| Feature | XPS (ESCA) | FT-IR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Measures kinetic energy of ejected photoelectrons | Measures absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds |

| Primary Information | Elemental composition, chemical/oxidation states | Functional groups, molecular structure, chemical bonding |

| Depth of Analysis | ~1-10 nm (extremely surface-sensitive) | Bulk and surface (µm range, depends on technique) |

| Sample Types | Solid surfaces, thin films | Solids, liquids, gases |

| Chemical State Sensitivity | High (can distinguish oxidation states) | Moderate (identifies functional groups) |

| Quantitative Capability | Quantitative elemental composition | Semi-quantitative for functional groups |

Applications in Drug-Delivery and Implant Characterization

Implant Surface Modification and Biocompatibility

The biological response to an implant is heavily influenced by its surface chemistry. Studies have systematically investigated how different functional groups affect the foreign body reaction. For instance, polypropylene microspheres were coated with varying densities of -OH and -COOH groups using plasma polymerization, and the resulting tissue response was evaluated after subcutaneous implantation [36]. XPS was critical for quantifying the surface density of these functional groups and confirming the stability of the coatings before implantation. The study concluded that the type of functional group had a dramatic impact, with -COOH rich surfaces prompting the least tissue reactions, while the density of the groups had a minor influence [36].

In another application, XPS and FT-IR were used in tandem to characterize polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) thin coatings deposited by pulsed laser and electron beam methods. The combination of techniques confirmed the chemical structure of the coatings and identified defluorination, a sign of polymer degradation during deposition that could affect long-term stability and performance [41].

Drug-Delivery System Characterization

XPS and FT-IR are pivotal in developing and validating controlled-release systems. A prime example is the analysis of a zinc titanate-coated titanium implant designed for the sustained release of risedronate, a drug used to treat osteoporosis [35].

- Drug Distribution: FT-IR imaging was used to confirm that the drug was evenly distributed over the entire surface of the alloy, a crucial factor for consistent dosing [35].

- Material and Drug Verification: The effectiveness of the zinc titanate coating and the successful attachment of the drug molecule to the implant surface were verified using a suite of techniques, including SEM, XPS, EDS, and FT-IR imaging [35].

- Release Kinetics: UV-VIS studies demonstrated that the risedronate could be released gradually upon contact with body fluids over a week, showcasing the potential of such a system for prolonged therapeutic effect [35].

Analysis of Complex Interactions

Advanced applications combine these techniques to deconvolute complex interfacial processes. A study on the binding of humic acid (a model organic compound) to kaolinite (a clay mineral) used two-dimensional FTIR correlation analysis (2D-FTIR-CoS) alongside XPS [42]. This powerful combination allowed researchers to:

- Identify the specific functional groups (e.g., carboxylate COO–, aliphatic OH) participating in the binding.

- Determine the sequence of interaction, showing that inner-sphere complexes formed before outer-sphere complexes over time.

- Quantify the contribution of different binding mechanisms (e.g., ligand exchange, electrostatic attraction), which was found to be 13.90% at pH 4.0 and 7.65% at pH 6.0 for the COOH group [42].

This level of detailed, mechanistic insight is directly applicable to understanding how drug molecules or bioactive coatings interact with carrier materials or native tissue.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A Standard Workflow for Coating Analysis

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for characterizing a drug-loaded coating on an implant surface, integrating both XPS and FT-IR.

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: XPS Analysis of Implant Surface Chemistry

This protocol is adapted from studies on functionalized polymer surfaces and PTFE coatings [36] [41].

Sample Preparation:

- Cut the implant or coating material to an appropriate size (typically ~1 cm x 1 cm).

- Clean the surface with a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol in an ultrasonic bath) to remove adventitious carbon and contaminants.

- Dry thoroughly in a vacuum oven or under a stream of inert gas (e.g., N₂).

Instrument Calibration & Setup:

- Use a standard sample (e.g., clean gold or silver foil) to calibrate the XPS instrument's binding energy scale.

- Mount the sample on a holder using conductive double-sided tape or a metal clip to minimize charging.

- Load the sample into the introduction chamber and pump down to ultra-high vacuum (typically < 10⁻⁸ mbar).

Data Acquisition:

- Survey Scan: Acquire a wide energy range scan (e.g., 0-1200 eV) to identify all elements present on the surface. Use an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) with a pass energy of 50-100 eV [7] [41].

- High-Resolution Scans: For each element of interest (e.g., C 1s, O 1s, N 1s, specific metal orbitals), acquire high-resolution spectra with a lower pass energy (e.g., 20-50 eV) for better energy resolution.

- Charge Neutralization: Use a low-energy electron flood gun to neutralize charge buildup on insulating samples.

Data Analysis:

- Apply a linear or Shirley background subtraction to the peaks.

- For quantitative analysis, use atomic sensitivity factors to calculate the relative atomic concentrations of detected elements.

- Deconvolute complex high-resolution peaks (e.g., C 1s) into sub-peaks representing different chemical states (e.g., C-C, C-O, C=O, O-C=O) using curve-fitting software.

Protocol 2: FT-IR Characterization of Drug-Polymer Interactions

This protocol is based on methods used in drug-delivery system and nanocomposite characterization [35] [39] [40].

Sample Preparation (ATR Mode):