Surface Ligand Exchange of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Techniques, Applications, and Frontiers in Biomedicine

Surface ligand exchange is a critical transformation that enables the application of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) in biomedicine and optoelectronics.

Surface Ligand Exchange of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Techniques, Applications, and Frontiers in Biomedicine

Abstract

Surface ligand exchange is a critical transformation that enables the application of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) in biomedicine and optoelectronics. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of ligand chemistry, state-of-the-art methodological approaches, and advanced characterization techniques. We explore the pivotal role of ligand exchange in enhancing the colloidal stability, biocompatibility, and targeted functionality of PQDs for applications such as high-quality in vivo bioimaging. The content also addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies to overcome challenges like fluorescence quenching and poor water dispersibility. Furthermore, we present a comparative analysis of validation methodologies, including NMR spectroscopy and diffusometry, for quantifying ligand binding dynamics. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this article serves as a strategic guide for leveraging surface-engineered PQDs in next-generation diagnostic and therapeutic platforms.

The Core Chemistry of PQD Surfaces: Understanding Ligand Roles and Exchange Fundamentals

Surface ligands are molecular entities anchored to the surface of nanoparticles, serving as the primary interface between the inorganic nanomaterial and its external environment. Their role transcends mere surface decoration; they are fundamental components that dictate the very identity and function of the nanoparticle [1]. For perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) and other functional nanomaterials, surface ligands are indispensable from the initial synthesis in organic solvents through to sophisticated biomedical applications such as biosensing and drug delivery [1] [2]. The presence of these organic shells is not a passive phenomenon but a critical determinant of the nanoparticle's colloidal integrity, optoelectronic properties, and biological interactions [1] [2]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on surface ligand exchange techniques for PQDs, elucidates the quintessential functions of surface ligands and provides detailed protocols for their engineering, aiming to equip researchers with the practical knowledge to harness their full potential.

The Multifunctional Nature of Surface Ligands: A Lifecycle Perspective

Ligands in Synthesis and Stabilization

The journey of a quantum dot begins in organic solvents, where surface ligands act as sophisticated molecular directors during synthesis. They control critical parameters such as nucleation and growth by selectively binding to specific crystal facets, thereby enforcing size and shape control to produce monodisperse populations [1]. For instance, in the synthesis of PbS colloidal quantum dots (CQDs), ligands like oleic acid are paramount for achieving narrow size distributions [3]. Beyond synthesis, these ligands prevent irreversible aggregation or Oswald ripening by providing steric or electrostatic repulsion, ensuring long-term colloidal stability in harsh biological milieus—a prerequisite for any biomedical application [1]. The replacement of initial hydrophobic ligands with hydrophilic counterparts is often necessary to confer aqueous suspendability and functionality in physiological environments [1].

Ligands as Modulators of Physicochemical Properties

A nanoparticle's core properties are profoundly influenced by its surface. Ligands directly impact key optoelectronic characteristics; for example, they can enhance the photoluminescent quantum yield (PLQY) of semiconductor nanocrystals by passivating surface defects that would otherwise act as non-radiative recombination centers [1] [3]. Conversely, dynamic binding and the insulating nature of certain ligands can detrimentally affect charge transport and stability, presenting a central challenge in device engineering [2] [4]. This is particularly critical for optoelectronic devices like PbS CQD-based solar cells, where replacing long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid) with shorter ones (e.g., EDT) is mandatory to facilitate efficient carrier transport [3] [4].

Ligands at the Nano-Bio Interface

In the biomedical realm, surface ligands define the nanoparticle's identity when it interacts with complex biological systems. They form a dynamic interface, governing protein adsorption (formation of the "protein corona"), cellular uptake, biocompatibility, biodistribution, and eventual clearance [1] [5]. This interface often presents a paradox: during systemic circulation, ligands must minimize non-specific interactions with proteins and cells to evade the reticuloendothelial system (RES), yet at the target site, they are often required to facilitate specific binding and cellular internalization [1]. This contradictory demand makes rational ligand design one of the most significant hurdles in nanomedicine translation. Furthermore, ligand choice is inextricably linked to mitigating toxicity concerns, such as the release of lead ions (Pb²⁺) from CsPbBr₃ PQDs, where moving towards lead-free alternatives like bismuth-based PQDs or implementing robust surface passivation strategies becomes imperative [6] [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Binding and Exchange

The process of ligand exchange is not merely a substitution but a thermodynamic equilibrium governed by the relative binding affinities of the incoming and outgoing ligands [7]. A quantitative understanding of these interactions is crucial for rational design.

Table 1: Quantitative Binding Affinities of Different Ligand Classes on Metal Oxide Nanoparticles (e.g., TiO₂ Anatase) [8]

| Ligand Class | Example Functional Group | Relative Adsorption Strength | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphonic Acid | -PO(OH)₂ | High | Strongest binding; forms robust, stable monolayers; high grafting density |

| Catechol | 1,2-dihydroxybenzene | Medium to High | Strong bidentate coordination; useful in various pH conditions |

| Carboxylic Acid | -COOH | Medium | Moderate binding strength; dynamic binding/desorption |

The thermodynamic perspective of ligand exchange reveals that the feasibility and mechanism of replacing native ligands with functional ones depend on the binding constant of the new ligand and the overall change in free energy [7]. Quantitative studies, such as those employing dye-displacement assays on Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), have provided a methodology for determining apparent binding constants, offering invaluable insights for predicting and manipulating surface chemistry [9]. For instance, ligand affinity is highly dependent on the underlying metal-ion composition of the material, underscoring the need for a tailored approach [9].

Experimental Protocols: Ligand Exchange and Characterization

Protocol 1: Solid-State Ligand Exchange for PbS CQD Films

This protocol is critical for fabricating conductive quantum dot films for optoelectronic devices like photovoltaics and photodetectors [3] [4].

- Film Deposition: Spin-coat a concentrated solution of PbS CQDs (capped with native oleic acid ligands) in a non-polar solvent (e.g., octane or toluene) onto a pre-cleaned substrate to form an as-cast film. Typical initial thickness is ~40 nm.

- Ligand Solution Application: Introduce a polar solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) containing the short-chain ligand solution (e.g., 0.02 M 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) or mercaptopropionic acid (MPA)) onto the CQD film.

- Soaking and Reaction: Allow the film to soak in the ligand solution for an optimized time (typically 30-60 seconds) to facilitate the exchange reaction. The polar solvent helps displace the newly formed ligands (e.g., oleic acid) and excess short ligands.

- Rinsing and Drying: Spin-off the excess solution and rinse the film with neat polar solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) to remove the displaced long-chain ligands and any residual short-chain ligands.

- Layer-by-Layer Assembly: Repeat steps 1-4 to build the film to the desired thickness (e.g., 200-300 nm for a solar cell absorber layer).

Protocol 2: Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange for Biomedical PQDs

This protocol is designed to render PQDs water-dispersible and biocompatible for applications in biosensing and bioimaging [1] [2].

- Precipitation and Redispersion: Precipitate the original PQDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃ synthesized in octadecene with oleylamine/oleic acid ligands) from their organic solvent (e.g., hexane or toluene) by adding a polar anti-solvent (e.g., methanol or ethanol). Centrifuge (e.g., 8000 rpm for 5 min) and discard the supernatant.

- Ligand Exchange Reaction: Redisperse the PQD pellet in a suitable solvent (e.g., dimethylformamide, DMF) containing the new hydrophilic ligands (e.g., catechol-based ligands, dopamine, or specially designed zwitterionic polymers). Sonicate or stir the mixture for a controlled period (minutes to hours) to allow ligand exchange.

- Purification: Precipitate the ligand-exchanged PQDs by adding an anti-solvent (e.g., diethyl ether or ethyl acetate). Centrifuge to obtain a pellet.

- Transfer to Aqueous Buffer: Redisperse the final pellet in the desired aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) or deionized water. Filter the solution through a 0.2 μm syringe filter to remove any aggregates.

Protocol 3: Quantitative Determination of Ligand Grafting Density

This method uses thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to quantify the number of ligands bound per unit surface area of nanoparticles [8].

- Sample Preparation: Purify the ligand-capped nanoparticles thoroughly to remove all non-specifically bound (physisorbed) ligands. Dry the sample under vacuum to remove residual solvents.

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Subject the dried sample to a controlled temperature ramp (e.g., 25-600°C) in an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂). Monitor the weight loss as a function of temperature.

- Data Analysis: The sharp weight loss observed at intermediate temperatures corresponds to the decomposition of the chemically bound (chemisorbed) organic ligands. Use this weight loss percentage to calculate the grafting density (number of molecules per nm²) using the formula:

- Grafting Density (molecules/nm²) = [(ΔW / Ml) / (mcore / ρcore)] * [NA / Aspec]

- Where: ΔW is the weight fraction of the organic layer, Ml is the molecular weight of the ligand, mcore is the weight fraction of the inorganic core, ρcore is the density of the core material, NA is Avogadro's number, and Aspec is the specific surface area of the nanoparticles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Surface Ligand Engineering of Quantum Dots

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Primary long-chain ligand for synthesis and stabilization in non-polar solvents. | Provides excellent colloidal stability but insulates charge transport; must be exchanged for device integration. |

| 1,2-Ethanedithiol (EDT) | Short-chain ligand for solid-state exchange on PbS CQDs. | Enables conductive films for photovoltaics; offers initial air stability for small-size PbS CQDs [4]. |

| Phosphonic Acids | Strong-binding ligands for metal oxide surfaces (e.g., TiO₂). | Forms robust monolayers with high grafting density; superior stability versus carboxylic acids [8]. |

| Catechol / Dopamine | Bidentate anchor for solution-phase exchange onto PQDs. | Provides strong binding to metal sites; facilitates transfer to aqueous media for biomedical applications [8] [2]. |

| Atomic Ligands (e.g., Halides) | Inorganic ligands for surface passivation. | Reduces insulating organic layer thickness; enhances electronic coupling between QDs; improves device performance [2] [3]. |

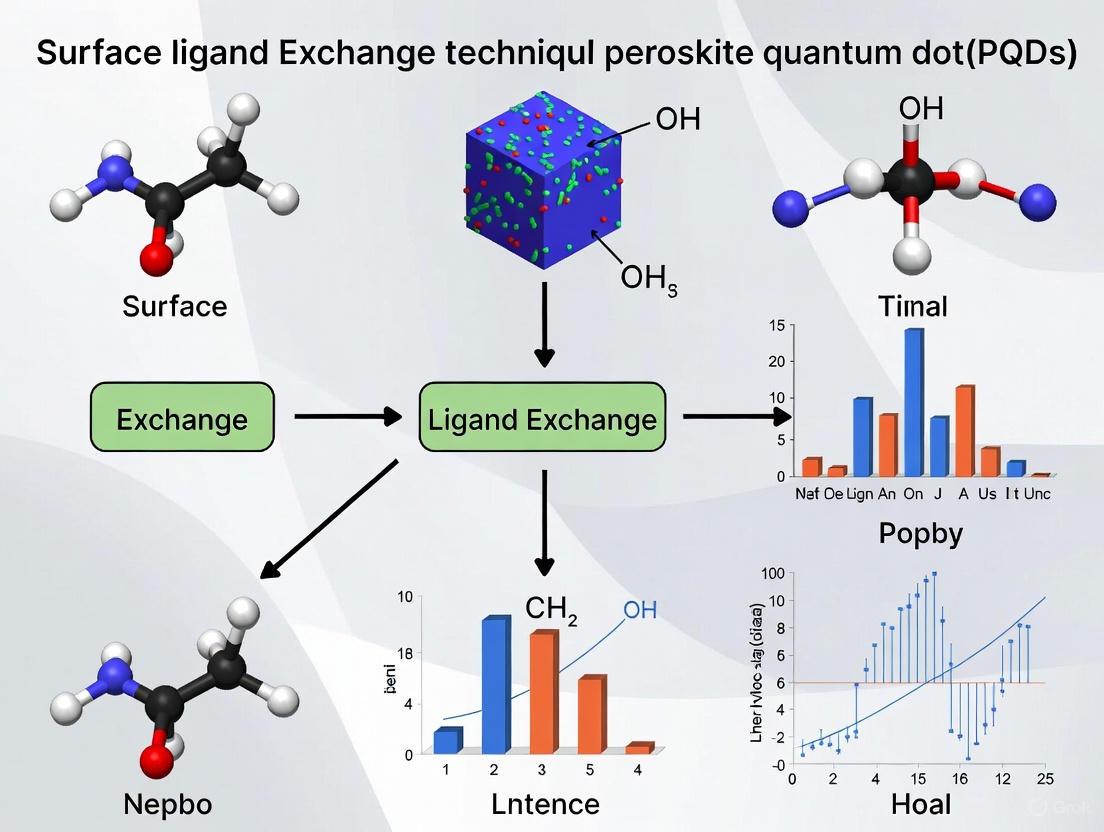

Schematic Workflows and Ligand Function

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows described in this note.

Application in Perovskite Quantum Dot Biosensing

Surface ligand engineering finds a critical application in the development of next-generation biosensors based on PQDs. For pathogen detection, ligands are engineered to serve dual purposes: they provide aqueous stability and also function as biorecognition elements. Technical advances include the creation of dual-mode lateral-flow assays that combine fluorescence and electrochemiluminescence for sensitive detection of Salmonella in food samples [6]. Furthermore, moving towards lead-free compositions, such as bismuth-based Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs, has enabled the development of photoelectrochemical sensors with sub-femtomolar sensitivity for microRNA (miRNA) while offering extended serum stability and meeting safety standards without additional coating [6]. The integration of machine-learning-assisted fluorescent arrays, where surface chemistry dictates binding specificity, allows for the complete discrimination of multiple bacterial species in complex matrices like tap water, showcasing the powerful synergy between tailored ligand chemistry and data analytics [6].

Surface ligands are the linchpin in the journey of quantum dots from synthetic vessels in the lab to real-world biomedical applications. A deep understanding of their roles in synthesis, stabilization, property modulation, and biological interaction is no longer optional but a fundamental requirement for progress in PQD research. The future of this field hinges on overcoming persistent challenges, including the development of scalable, lead-free PQD formulations, achieving long-term stability under physiological conditions, and navigating the regulatory pathways to clinical adoption [6]. The continued innovation in ligand design—such as the creation of stimuli-responsive ligands, hybrid passivation strategies, and atomic ligands—will be instrumental in unlocking the full potential of PQDs. The integration of these advanced nanomaterials with portable detection systems, nucleic-acid amplification techniques, and microfluidic platforms will ultimately pave the way for their practical implementation in point-of-care diagnostics and targeted therapeutics [6] [2] [5].

In the realm of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) research, surface ligand engineering has emerged as an indispensable strategy for modulating optoelectronic properties and enhancing material stability. The classification of ligands into X-type, L-type, and Z-type categories according to Green's covalent bond classification provides a fundamental framework for understanding and manipulating surface chemistry in PQD systems [10]. This classification system categorizes ligands based on their electron donation capabilities and binding mechanisms, which directly influence the electronic structure, surface passivation, and colloidal stability of PQDs [11]. The dynamic binding equilibrium of surface-bound ligands represents a critical factor governing PQD stability and functionality, with recent research revealing complex multi-state binding scenarios that extend beyond traditional two-state models [10].

Within the context of surface ligand exchange techniques, precise classification of binding motifs enables researchers to rationally design ligand engineering strategies that address the inherent instability of PQDs under environmental stressors such as humidity, temperature fluctuations, and light exposure [11]. The ionic crystal nature of CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) PQDs makes them particularly susceptible to degradation, necessitating robust ligand binding to passivate surface defects and prevent aggregation [12]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for classifying ligand binding motifs, quantifying binding interactions, and implementing experimental protocols for ligand exchange in PQD systems, with particular emphasis on practical applications for researchers and scientists engaged in PQD development for optoelectronics and related fields.

Theoretical Framework of Ligand Classification

Fundamental Binding Motifs

The covalent bond classification system divides ligands into three distinct categories based on their electron donation characteristics and binding configurations with PQD surfaces:

X-type Ligands: These anionic ligands function as one-electron donors to surface metal cations, compensating for excess cationic charge [10]. In PQD systems, carboxylates (such as oleate - OA) and thiolates represent common X-type ligands that bind to lead-rich surfaces. These ligands typically form ionic or covalent bonds with metal sites on the PQD surface, with binding strength influenced by the electronegativity of the donor atom and the steric bulk of the organic backbone [11].

L-type Ligands: Characterized as neutral two-electron donors, L-type ligands coordinate to surface metal sites without altering the net charge of the PQD [10]. Primary examples include amines and phosphines, though carboxylic acids (e.g., oleic acid) and thiols can also function as L-type ligands under specific conditions. The binding mechanism typically involves Lewis acid-base interactions, where the ligand donates an electron pair to an empty orbital on the surface metal atom [10].

Z-type Ligands: These neutral two-electron acceptors coordinate to surface chalcogen anions, functioning as Lewis acids [10]. In practice, Z-type ligands are often classified as metal complexes with two anionic X-type ligands attached, such as Pb(OA)2 and Cd(OA)2. Their binding is characterized by acceptance of electron density from surface anions into empty orbitals on the ligand's central atom [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Ligand Binding Motifs in PQD Systems

| Ligand Type | Electron Donation | Binding Mechanism | Common Examples | Primary Binding Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-type | One-electron donor | Ionic/covalent to metal cations | Carboxylates (oleate), thiolates | Pb-rich (111) facets [10] |

| L-type | Two-electron donor | Lewis base to metal cations | Amines, phosphines, carboxylic acids | Pb atoms, halide ions [11] |

| Z-type | Two-electron acceptor | Lewis acid to chalcogen anions | Metal carboxylates (Pb(OA)2) | Halide sites [10] |

Advanced Binding Concepts

Recent investigations have revealed that ligand binding in PQD systems exhibits greater complexity than the fundamental classification suggests. Studies of oleic acid (OAH) ligand binding to PbS QD surfaces have identified multiple distinct binding states beyond the traditional bound-free dichotomy [10]. Through multimodal NMR techniques, researchers have quantified three populations: (1) strongly bound (Sbound) oleate on Pb-rich (111) facets as X-type ligands, (2) weakly bound (Wbound) OAH on (100) facets through acidic headgroup coordination, and (3) free ligands in solution [10].

The binding behavior of ligands is further influenced by surface facet dependency, with different crystal facets exhibiting distinct coordination environments and binding affinities. For instance, PbS QDs demonstrate strong X-type binding on (111) facets versus weaker coordination on (100) facets [10]. This facet-dependent binding has profound implications for ligand exchange efficiency and overall PQD stability, as the equilibrium between strongly and weakly bound ligand populations directly affects susceptibility to environmental degradation [10] [11].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Binding

Population Distribution and Binding Energetics

Multimodal NMR spectroscopy has enabled precise quantification of ligand populations in different binding states, providing insights into the equilibria between distinct coordination environments. In PbS QD systems with oleic acid/oleate ligands, population analysis reveals temperature-dependent distribution between strongly bound, weakly bound, and free states [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Population Distribution of Oleic Acid Ligands on PbS QDs [10]

| Ligand State | Population Fraction (%) | Binding Energy | Exchange Kinetics | Proposed Structural Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Bound (S_bound) | 40-60% | High | Slow (timescale > ms) | X-type oleate on Pb-rich (111) facets [10] |

| Weakly Bound (W_bound) | 20-35% | Moderate | Fast (0.09-2 ms) | L-type OAH on (100) facets through -COOH coordination [10] |

| Free | 15-30% | None | Diffusion limited | Unbound OAH in solution [10] |

The population fractions exhibit concentration and temperature dependence, with increasing OAH titration leading to redistribution between states. Quantitative analysis reveals rapid exchange kinetics (0.09-2 ms) between weakly bound and free OAH ligands, while strongly bound ligands demonstrate considerably slower exchange rates [10]. This dynamic equilibrium has significant implications for ligand exchange strategies, as the weakly bound population serves as an intermediate state during displacement reactions.

Impact on PQD Optical Properties

Ligand binding motifs directly influence the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and stability of PQDs through surface passivation efficacy. The presence of strongly bound ligands correlates with enhanced defect passivation and improved PLQY, while weakly bound populations contribute to dynamic equilibria that can compromise stability under environmental stress [11]. Studies demonstrate that tailored ligand engineering with multidentate binding motifs can increase the strongly bound ligand fraction, resulting in enhanced resistance to humidity, temperature, and light exposure [12].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Analysis

Multimodal NMR Spectroscopy for Ligand Quantification

Principle: This protocol employs nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and diffusometry to quantify ligand populations, binding states, and exchange kinetics in PQD systems [10].

Materials:

- Purified PQD sample (e.g., OA-capped PbS QDs)

- Deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl₃)

- NMR reference standard (e.g., ferrocene)

- Titration ligand (e.g., oleic acid for acid-base exchange)

- NMR spectrometer with diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) capability

- Dynamic NMR analysis software

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

1H NMR Spectroscopy:

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectrum with sufficient scans (≥8) for high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR ≈ 700) [10].

- Identify bound ligand signatures by characteristic line broadening (fwhm ≈ 60 Hz for bound OA vs. ∼1 Hz for free OA).

- Quantify bound ligand density by integrating alkene resonances relative to internal standard [10].

DOSY Measurements:

- Perform diffusion-ordered spectroscopy to distinguish populations based on diffusion coefficients.

- Identify strongly bound ligands (D ≈ 1 × 10⁻¹⁰ m²·s⁻¹), weakly bound ligands (intermediate D), and free ligands (D ≈ 1.45 × 10⁻⁹ m²·s⁻¹) [10].

- Calculate population fractions from diffusion-resolved spectra.

Titration Experiments:

- Titrate increasing concentrations of exchange ligand (e.g., OAH) into PQD solution.

- Monitor changes in population fractions after each addition.

- Construct binding isotherms to determine equilibrium constants [10].

Dynamic NMR Analysis:

- Acquire temperature-dependent NMR spectra (typically 25-60°C).

- Perform line shape analysis to determine exchange rates between states.

- Calculate activation energies from Arrhenius plots [10].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for multimodal NMR ligand analysis

Ligand Exchange and Binding Motif Characterization

Principle: This protocol details the methodology for performing ligand exchange reactions and characterizing the resulting binding motifs using spectroscopic techniques.

Materials:

- Native ligand-capped PQDs (e.g., OA/OAm-capped CsPbBr₃)

- Exchange ligands (X-type: carboxylic acids, thiols; L-type: amines, phosphines)

- Non-polar solvents (toluene, hexane)

- Polar solvent for precipitation (acetone, ethanol)

- Centrifuge

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Photoluminescence spectrometer

- FT-IR spectrometer

Procedure:

Base PQD Synthesis:

Ligand Exchange:

- X-type Exchange: React OA-capped PQDs with carboxylic acids through acid-base mechanism [10].

- L-type Exchange: Treat with amine or phosphine ligands in appropriate solvent [11].

- Multidentate Ligands: Employ bifunctional ligands (e.g., dicarboxylic acids) for enhanced binding [12].

- Control reaction time (minutes to hours) and stoichiometry (ligand:QD ratio).

Post-Exchange Processing:

- Precipitate with polar solvent.

- Centrifuge and collect exchanged QDs.

- Redisperse in appropriate solvent for characterization.

Binding Motif Characterization:

- FT-IR Analysis: Identify binding through shifts in characteristic bands (e.g., COO⁻ stretch).

- UV-Vis/PL Spectroscopy: Monitor optical properties and quantum yield changes.

- NMR Analysis: Verify successful exchange and quantify binding populations per Protocol 4.1.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ligand Binding Studies in PQD Systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PQD Research | Binding Motif |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Ligands | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) | Base stabilization, size control during synthesis [11] | OA: X-type (as oleate); OAm: L-type [11] |

| X-type Exchange Ligands | Short-chain carboxylic acids, Thiols | Enhance charge transport, improve stability [11] | X-type (anionic one-electron donors) [10] |

| L-type Exchange Ligands | Primary amines, Phosphines | Passivate metal sites, modify surface reactivity [10] | L-type (neutral two-electron donors) [10] |

| Multidentate Ligands | Dicarboxylic acids, Amino acids | Stronger chelating binding, reduced dynamic exchange [12] | Mixed X/L-type (enhanced coordination) |

| Z-type Compounds | Metal carboxylates (e.g., Pb(OA)₂) | Passivate anionic surface sites [10] | Z-type (neutral two-electron acceptors) [10] |

| Solvents | Toluene, Hexane, Octadecene (ODE) | Reaction medium, precipitation solvents [11] | N/A |

| Analytical Standards | Ferrocene, CDCl₃ | Quantitative NMR reference, deuterated solvent [10] | N/A |

Visualization of Ligand Binding Concepts

Diagram 2: Hierarchical classification of ligand binding motifs

The precise classification of ligand binding motifs into X-type, L-type, and Z-type categories provides an essential foundation for rational surface engineering in PQD systems. The multimodal NMR protocols outlined in this application note enable quantitative assessment of ligand populations, binding strengths, and exchange kinetics, revealing complex multi-state binding equilibria that critically impact PQD stability and optoelectronic performance [10]. The research reagents and experimental methodologies detailed herein support the development of advanced ligand engineering strategies employing multidentate ligands and targeted binding motifs to enhance PQD stability against environmental stressors [11] [12]. As research in PQD optoelectronics advances, the systematic approach to ligand classification and analysis presented in this document will facilitate more precise control over surface chemistry, enabling the optimization of PQD materials for next-generation applications in light-emitting diodes, photovoltaics, and biological imaging.

Colloidal nanoparticles, including perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), are typically synthesized with long-chain, hydrophobic capping ligands such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) to control growth and ensure stability in non-polar solvents [13] [14]. While effective for synthesis and optical tuning, these native organic shells render the nanoparticles incompatible with aqueous biological media, severely limiting their application in drug development, biosensing, and bioimaging [14]. The core challenge is that this inherent hydrophobicity leads to instantaneous aggregation and precipitation in water-based solutions, disrupting assay systems and preventing interaction with biological targets.

Ligand exchange—the post-synthesis replacement of native hydrophobic ligands with hydrophilic counterparts—is therefore an essential processing step for biomedical applications. This technical note details the rationale, protocols, and material considerations for executing successful ligand exchanges, framed within the broader research context of tailoring PQD surfaces for aqueous dispersion and bio-conjugation.

The Scientific Rationale: Mechanisms of Ligand Exchange and Aqueous Stabilization

Fundamental Principles

Ligand exchange is primarily driven by the difference in binding affinity between the native and incoming ligands to the nanoparticle surface metal sites (e.g., Pb²⁺ in PbS or CsPbBr₃). The process often adheres to Pearson’s Hard-Soft Acid-Base (HSAB) theory, where the metal cation (a soft acid) preferentially binds with soft bases like thiolates or carboxylates [15]. The binding strength is quantified by the binding energy (Ebinding), which dictates the thermodynamic favorability of the exchange [16].

A critical challenge in conventional ligand exchange is the "strong replaces weak" rule, which historically made it difficult to replace a strong native ligand with a weaker, but more hydrophilic, one [16]. Advanced strategies have been developed to overcome this limitation. One innovative approach uses an intermediate ligand, diethylamine (DEA), whose binding affinity is pH-switchable. At high pH, DEA binds strongly to the metal surface, displacing the original ligand. Subsequent protonation with an acid weakens its binding, allowing it to be displaced by the desired weak, hydrophilic ligand [16].

For PQDs, successful exchange introduces polar functional groups (–COOH, –NH₂, –OH) that enable hydrogen bonding with water, while the new ligand's compact size and multidentate coordination enhance surface passivation and electronic coupling between dots, which is crucial for maintaining optoelectronic performance [17] [14].

Ligand Exchange Workflow and Multidentate Binding

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for ligand exchange and the structure of effective multidentate ligands.

Application Notes: Quantitative Performance of Ligand-Exchanged PQDs

The choice of ligand directly impacts the optical properties and colloidal stability of the resulting water-dispersible PQDs. The following table summarizes the performance of different ligand systems as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Ligand-Exchanged PQDs in Aqueous Media

| Ligand System | PQD Type | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Application Target | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Succinic Acid (SA) / NHS | CsPbBr₃ | Enhanced PL intensity vs. OA; enabled bioconjugation; BSA sensing LOD: 51.47 nM. | Biosensing (Protein) | [14] |

| Benzamidine Hydrochloride (PhFACl) | FAPbI₃ | Filled A-site and X-site vacancies; PCE of PQD solar cell: 6.4% (vs. 4.63% conventional). | Photovoltaics | [17] |

| Folic Acid, EDTA, Glutamic Acid | CsPbBr₃ | Varied binding affinity and water stability; SA showed strongest binding. | Biosensing | [14] |

| Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ (Lead-free) | N/A | Sub-femtomolar miRNA sensitivity; extended serum stability; meets safety standards. | Photoelectrochemical Biosensing | [6] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for two key ligand exchange approaches: a direct solution-phase exchange and a solid-state film-based exchange.

Protocol 1: Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange with Succinic Acid and NHS for CsPbBr₃ PQDs

This protocol describes the transformation of hydrophobic CsPbBr₃ PQDs into water-stable, bio-conjugatable probes [14].

- Synthesis of Native CsPbBr₃ PQDs: Synthesize OA/OLA-capped CsPbBr₃ PQDs via a hot-injection method. Briefly, dissolve Cs₂CO₃ in OA and ODE to form a Cs-oleate precursor. In a separate flask, heat PbBr₂ in ODE under vacuum, then add OA and OLA. Inject the Cs-oleate precursor at high temperature (e.g., 150-170 °C). Quench the reaction with an ice bath after a few seconds. Purify the PQDs by centrifugation and redispersion in toluene [14].

- Ligand Exchange to Succinic Acid (SA):

- Precipitation: Add a non-solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) to the pristine PQD solution in toluene to precipitate the PQDs. Recover them via centrifugation (8000 rpm, 5 min).

- Ligand Incubation: Redisperse the pellet in a solution of SA (≥99%) dissolved in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF or a DMF/toluene mixture). Vortex and incubate for a short period (e.g., 1-2 minutes).

- Purification: Precipitate the SA-capped PQDs by adding a non-solvent (e.g., diethyl ether). Centrifuge and discard the supernatant. Wash the pellet multiple times to remove excess ligands and by-products.

- Dispersion: Finally, disperse the purified SA-PQD pellet in a polar aprotic solvent like DMF.

- Activation with N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS):

- Add an NHS (98%) solution (in water or DMF) to the SA-PQD dispersion.

- Allow the reaction to proceed to form the NHS ester on the PQD surface, activating the carboxyl groups for bioconjugation with primary amines on target biomolecules.

- Transfer to Aqueous Media: After NHS activation, precipitate the PQDs and redisperse them directly in deionized water or a suitable aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) for subsequent bio-conjugation and sensing applications.

Protocol 2: Solid-State Ligand Exchange and Anti-Solvent Treatment for FAPbI₃ PQD Films

This protocol is optimized for processing PQD films for optoelectronic devices like solar cells, focusing on surface passivation and vacancy repair [17].

- PQD Film Deposition: Spin-coat the synthesized FAPbI₃ PQDs (dispersed in hexane) onto the desired substrate (e.g., compact TiO₂ on FTO glass). Typical spin speed is 2000 rpm for 40 seconds.

- Anti-Solvent Washing:

- During the spin-coating process, drip an appropriate anti-solvent (e.g., Methyl Acetate - MeOAc) onto the spinning film.

- The anti-solvent selectively removes the long-chain OA/OAm ligands without destroying the perovskite crystal structure. This step is critical for removing excess insulating ligands and facilitating subsequent exchange.

- Ligand Passivation with PhFACl:

- Prepare a solution of the short, passivating ligand, such as Benzamidine Hydrochloride (PhFACl).

- Apply this solution to the PQD film after the anti-solvent wash. The PhFACl molecules fill the surface vacancies (A-site formamidinium and X-site halide), thereby improving electronic coupling and stability.

- Layer Buildup: Repeat the deposition, anti-solvent washing, and passivation steps 3-5 times to build a PQD film of the desired thickness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ligand Exchange and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Ligand Exchange |

|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OLA) | Native long-chain ligands used in standard PQD synthesis. The exchange process aims to replace them. |

| Succinic Acid (SA) | A bidentate dicarboxylic acid ligand that chelates to surface Pb²⁺ ions, providing a short, hydrophilic surface and enhancing PL [14]. |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) | An activator that reacts with surface carboxyl groups (e.g., from SA) to form an NHS ester, enabling covalent bioconjugation with biomolecules [14]. |

| Benzamidine Hydrochloride (PhFACl) | A short, passivating ligand for FAPbI₃ PQDs. The formamidine group fills A-site vacancies while Cl⁻ fills X-site vacancies, boosting optoelectronic properties [17]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | An anti-solvent with optimal polarity for removing long-chain surface ligands from PQD solid films without dissolving or degrading the perovskite crystal [17]. |

| Diethylamine (DEA) | A pH-switchable intermediate ligand used to overcome the "strong replaces weak" rule, enabling the installation of weak capping ligands [16]. |

| Ethanedithiol (EDT) / NH₄SCN | Compact ligands used in solid-state exchanges to replace long organic shells, drastically improve electrical conductivity in NC films, and facilitate charge transport [18]. |

Surface ligand engineering is a foundational element in the development of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) with tailored optoelectronic properties. Traditional models often simplify ligand behavior into a two-state framework—bound versus unbound. However, emerging evidence reveals a more complex reality where ligands exist across a continuum of binding affinities, critically influencing PQD stability, passivation, and charge transport. This application note details experimental methodologies and analytical techniques for identifying and characterizing these distinct ligand populations, providing researchers with a refined framework for optimizing PQD materials. The insights presented are particularly valuable for designing targeted ligand exchange protocols that address specific weak or strong binding sites to enhance device performance and environmental stability.

Theoretical Framework: From Two-State to Multi-State Binding

The conventional two-state model for ligand binding, while useful, provides an incomplete picture of surface interactions in complex PQD systems. Advanced binding models, such as the two-state model adapted from pharmacological studies, describe systems where a ligand can bind to different states or conformations of a target. In receptor kinetics, this model has been successfully applied to measure the binding kinetics of unlabeled ligands when a radioligand displays biphasic association characteristics, indicating preference for distinct receptor states [19] [20]. Similarly, in PQD systems, ligands do not simply bind uniformly to surface sites but exhibit a spectrum of binding energies influenced by surface topography, crystal facets, and the presence of defects.

This heterogeneous binding behavior creates distinct populations of weakly bound and strongly bound ligands that coexist on the PQD surface. Weakly bound ligands typically interact through van der Waals forces or single coordination points, while strongly bound ligands form multiple coordination bonds or integrate into the crystal lattice itself. The dynamic equilibrium between these populations governs critical material properties, including colloidal stability, trap state passivation, and charge carrier mobility.

Table: Characteristics of Weakly and Strongly Bound Ligand Populations in PQDs

| Property | Weakly Bound Ligands | Strongly Bound Ligands |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy | Low (physisorption) | High (chemisorption) |

| Primary Interactions | Van der Waals, hydrogen bonding | Covalent coordination, ionic bonds |

| Exchange Kinetics | Fast | Slow |

| Thermal Stability | Low | High |

| Impact on Charge Transport | Can be removed to enhance conductivity | Provide essential surface passivation |

| Common Examples | Solvent molecules, loosely coordinated oleylamine | Atomic ligands (halides), bidentate carboxylates |

Experimental Evidence for Heterogeneous Ligand Binding

Spectroscopic Identification of Binding Modes

Multiple analytical techniques provide direct evidence for coexisting ligand populations. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy reveals distinct binding configurations through shifts in characteristic vibrational modes. For example, carboxylate ligands can display both monodentate and bidentate coordination geometries with measurable energy differences. In PbS CQD systems, ligand exchange processes show varying proportions of these coordination modes, indicating populations with different binding strengths [4].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly liquid-state NMR, has proven invaluable for studying ligand exchange mechanisms. In studies of InP QDs, researchers used NMR to demonstrate that metal halide salts dissociate in polar solvents to form metal-solvent complex cations (e.g., [Al(MFA)6]³⁺) which then passivate the QD surface after removal of organic ligands [21]. The dynamics of this ligand exchange process reveal different populations of surface-bound species with varying residence times and binding affinities.

Functional Manifestations of Binding Heterogeneity

The practical consequences of heterogeneous ligand binding are evident in PQD device performance and stability. Research on PbS CQDs has demonstrated that carrier mobility strongly depends on ligand species and their binding modes. Short-chain organic ligands like 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) and carboxylic acids enhance carrier transport compared to long-chain ligands, but with different environmental stability profiles [4]. This suggests that optimal ligand engineering must balance strong binding for permanent passivation with weaker-binding ligands that can be selectively removed to enhance inter-dot charge transport.

Furthermore, oxidation resistance varies significantly between different ligand populations. Smaller PbS CQDs (≤3 nm) show different oxidation products (PbSO₃) compared to larger dots (4-10 nm, PbSO₄), with the smaller dots demonstrating superior stability due to better surface passivation by strongly bound ligands that create spatial hindrance effects [4]. This size-dependent behavior underscores how nanocrystal curvature and facet accessibility create inherently different binding sites for ligands.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solid-State Ligand Exchange with Affinity-Based Selection

This protocol enables the replacement of native long-chain ligands with shorter counterparts while preserving populations of strongly bound ligands that provide essential surface passivation.

Materials:

- PbS or Pb-halide PQDs with native oleic acid/oleylamine ligands

- Anhydrous solvents: octane, acetonitrile, methanol

- Short-chain ligand solutions: 1% (v/v) 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) in acetonitrile, 1% (v/v) mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) in methanol

- Inert atmosphere glove box

Procedure:

- PQD Film Fabrication: Spin-coat PQD solution (10-15 mg/mL in octane) onto substrate at 2000 rpm for 30 seconds to form uniform 40 nm-thick film.

- Ligand Exposure: Apply short-chain ligand solution (EDT or MPA) to the film surface and incubate for 30-60 seconds without disturbance.

- Solution Removal: Spin-cast at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds to remove excess solution and displaced ligands.

- Washing: Rinse with neat acetonitrile (for EDT) or methanol (for MPA) while spinning to remove weakly bound excess ligands.

- Layer Buildup: Repeat steps 1-4 for 5-8 cycles to achieve desired film thickness (200-300 nm).

- Annealing: Thermally anneal at 70°C for 10 minutes in inert atmosphere to stabilize strongly bound ligand populations.

Critical Considerations:

- Monitor film photoluminescence after each cycle; significant quenching indicates excessive removal of passivating ligands.

- Adjust ligand solution concentration (0.5-2%) to optimize the ratio of weakly to strongly bound ligands based on specific application requirements.

Protocol 2: Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange with Metal Halide Salts

This protocol utilizes metal-solvent complexes to create well-passivated PQD surfaces with controlled ligand affinity distributions, particularly effective for InP PQD systems.

Materials:

- InP PQDs with myristate (X-type) or oleylamine (L-type) native ligands

- Metal halide salts: InCl₃, GaBr₃, AlI₃ (≥99.99% purity)

- Polar solvents: n-methylformamide (MFA), dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

- Non-polar solvents: hexane, octane, toluene

- Centrifuge tubes (20 mL)

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve metal halide salt (0.1 M) in polar solvent (MFA or DMF) with vigorous stirring until fully dissolved, forming [M(Solvent)₆]³⁺ complex cations.

- Ligand Exchange: Mix PQD solution (1 mL at 5 mg/mL in non-polar solvent) with metal halide solution (2 mL) in centrifuge tube.

- Phase Transfer: Vortex mixture for 60 seconds to facilitate phase transfer of PQDs from non-polar to polar phase.

- Separation: Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 3 minutes to achieve complete phase separation.

- Purification: Collect polar phase containing ligand-exchanged PQDs and wash three times with fresh polar solvent.

- Concentration: Adjust final concentration to 10-50 mg/mL for device fabrication.

Critical Considerations:

- Metal halide concentration controls the balance between ligand binding affinities; optimize for specific PQD size and composition.

- Solvent polarity significantly influences complex formation; DMSO provides stronger coordination than DMF or MFA.

- Monitor colloidal stability over time; stable solutions indicate successful formation of appropriately balanced ligand populations.

Protocol 3: Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Populations

This analytical protocol characterizes the distribution of weakly and strongly bound ligand populations using a combination of spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques.

Materials:

- Ligand-exchanged PQD samples

- Solvents: chloroform, hexane, ethanol, acetonitrile

- Centrifugal filtration devices (10 kDa MWCO)

- FTIR, NMR, and UV-Vis spectrophotometers

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare PQD solutions at consistent concentration (5 mg/mL) in deuterated solvent for NMR or as thin films for FTIR.

- Weakly Bound Ligand Extraction: Mix PQD solution with weak solvent (hexane, 1:10 v/v), incubate 10 minutes, and separate via centrifugation.

- Strongly Bound Ligand Liberation: Treat PQD pellet with strong solvent (chloroform:acetic acid 9:1) to displace all remaining ligands.

- FTIR Analysis: Collect spectra of initial samples and after each extraction step. Monitor carbonyl (1700-1750 cm⁻¹) and amine (3300-3500 cm⁻¹) stretches for organic ligands; metal-halide vibrations (200-400 cm⁻¹) for inorganic ligands.

- NMR Analysis: Use ¹H NMR to quantify ligand concentrations in extraction fractions based on characteristic proton signals.

- Data Analysis: Calculate ratios of weakly to strongly bound ligands by comparing integrals of characteristic signals before and after extractions.

Critical Considerations:

- Perform extractions at consistent temperature (25±2°C) to ensure reproducible results.

- Include control experiments with known ligand:QD ratios to establish calibration curves.

- For metal-halide ligands, supplement with XPS analysis to quantify binding states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Studying Ligand Binding Populations in PQDs

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Organic Ligands | 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT), Mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) | Replace long-chain native ligands to enhance charge transport while maintaining passivation |

| Metal Halide Salts | InCl₃, GaBr₃, AlI₃ | Serve as inorganic ligands that form complex cations for surface passivation [21] |

| Polar Solvents | n-methylformamide (MFA), Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Dissolve metal halide salts and facilitate ligand exchange via complex formation |

| Analytical Standards | Deuterated solvents, Certified reference materials | Enable quantitative analysis of ligand populations via NMR and chromatography |

| Native Capping Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine, Myristate | Provide initial colloidal stability and serve as reference points for binding studies |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Ligand Binding Equilibrium and Detection Workflow

Advanced Ligand Exchange Methodology

Moving beyond simplistic two-state models of ligand binding represents a critical advancement in perovskite quantum dot research. The experimental evidence and methodologies presented herein demonstrate that PQD surfaces host heterogeneous distributions of weakly and strongly bound ligands that dynamically influence material properties. The protocols for ligand exchange and population analysis provide researchers with precise tools to manipulate these distributions for targeted applications. By acknowledging and exploiting this binding heterogeneity, scientists can design more effective surface engineering strategies that simultaneously optimize passivation, stability, and charge transport in next-generation PQD optoelectronics.

Advanced Ligand Exchange Techniques and Their Biomedical Applications

Sequential Solid-State Multiligand Exchange for Enhanced Photovoltaic Performance

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as a promising class of materials for next-generation photovoltaic technologies due to their exceptional optoelectronic properties, including size-tunable bandgaps, high absorption coefficients, and multiple exciton generation capabilities [22] [23]. Despite these advantages, ligand-passivated PQDs face significant challenges related to reduced photogenerated carrier mobility and separation, primarily due to the presence of long insulating surface ligands [22] [23]. This limitation substantially hampers their efficiency and performance in practical device applications.

Surface ligand exchange techniques represent a critical strategy for addressing these challenges in PQD research. While conventional long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) provide colloidal stability during synthesis, they impose detrimental insulating barriers that restrict charge transport in solid-state films [23] [12]. Sequential solid-state multiligand exchange has recently been developed as an innovative approach to replace these long-chain ligands with shorter alternatives while simultaneously passivating surface defects, thereby enhancing both efficiency and stability in photovoltaic devices [22].

This protocol details a sequential solid-state multiligand exchange process for FAPbI₃ PQDs, which utilizes a solution of 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) in methyl acetate (MeOAc) to systematically replace long-chain octylamine (OctAm) and oleic acid (OA) ligands [22] [23]. The implementation of this technique has demonstrated remarkable improvements in photovoltaic performance, including approximately 28% enhancement in power conversion efficiency and significantly reduced hysteresis in n-i-p solar cells [22].

Experimental Principles and Workflow

The fundamental principle underlying sequential solid-state multiligand exchange involves the replacement of dynamically bound long-chain insulating ligands with shorter organic and inorganic ligands that improve inter-dot coupling and charge transport while maintaining surface passivation [22] [23]. This process addresses two critical challenges simultaneously: the reduction of inter-dot spacing to enhance film conductivity and the suppression of surface defects that contribute to non-radiative recombination [23].

The ligand exchange mechanism proceeds through a coordination complex formation between the incoming short-chain ligands and undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the PQD surface [24]. The sequential approach ensures that ligand removal and replacement occur in a controlled manner that minimizes surface defect formation and preserves the structural integrity of the quantum dots [22]. The hybrid MPA/FAI passivation strategy has been shown to improve thin-film conductivity and quality by reducing inter-dot spacing and defects, thereby mitigating vacancy-assisted ion migration [22] [23].

The complete experimental workflow encompasses PQD synthesis, purification, ligand exchange, and device fabrication, as illustrated below:

Figure 1: Complete experimental workflow for sequential solid-state multiligand exchange of FAPbI₃ PQDs and photovoltaic device fabrication.

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of sequential solid-state multiligand exchange requires careful selection and preparation of research reagent solutions. The table below details the essential materials, their specific functions, and critical considerations for use.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Sequential Solid-State Multiligand Exchange

| Reagent | Function/Role | Specifications & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lead(II) Iodide (PbI₂) | Perovskite precursor providing Pb²⁺ cations | 99.9% trace metals basis; moisture-sensitive requiring anhydrous handling [23] |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | A-site cation source and short-chain ligand | 99.9% trace metals basis; serves dual role in perovskite structure and surface passivation [22] [23] |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short-chain ligand for surface passivation | 90% purity; thiol group coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [22] [23] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Long-chain synthesis ligand | 97% purity; provides initial colloidal stability but inhibits charge transport [23] |

| Octylamine (OctAm) | Long-chain synthesis ligand | 99% purity; work with OA to control nucleation and growth [23] |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Purification and ligand exchange solvent | 99.5% purity; efficiently removes long-chain ligands without damaging PQD structure [22] [23] |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Polar solvent for precursor dissolution | Anhydrous, 99.8%; enables dissolution of perovskite precursors [23] |

| Toluene | Non-polar solvent for reprecipitation | Anhydrous, 99.8%; induces quantum dot formation during synthesis [23] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of FAPbI₃ Colloidal Quantum Dots

The synthesis of FAPbI₃ colloidal quantum dots follows a modified ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method, which offers advantages over traditional hot-injection techniques through its operational simplicity, low-temperature processing, and scalability [23].

Procedure:

- PbI₂ Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.1 mmol (0.045 g) of PbI₂ in 2 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile (ACN) containing 200 μL of oleic acid (OA) and 20 μL of octylamine (OctAm) under continuous stirring until a clear solution is obtained [23].

- FAI Solution Preparation: Separately, prepare the formamidinium iodide solution by mixing 0.08 mmol (0.0137 g) of FAI with 40 μL of OA, 6 μL of OctAm, and 0.5 mL of ACN [23].

- Reaction Initiation: Add the FAI solution dropwise to the PbI₂ solution with continuous stirring at room temperature [23].

- Quantum Dot Formation: Inject the resulting mixture into 10 mL of preheated toluene (70°C) under rapid stirring, immediately followed by quenching in an ice/water bath to control particle growth [23].

- Initial Isolation: Collect the precipitate via ultracentrifugation at 9000 rpm for 15 minutes [23].

- Size Selection: Redisperse the obtained product in 1 mL of hexane and centrifuge again at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove agglomerated particles, yielding unpurified perovskite quantum dots (UP PQDs) [23].

Liquid-Phase Purification

Liquid-phase purification is critical for removing excess precursors and weakly bound ligands while maintaining quantum dot stability.

Procedure:

- Solvent Addition: Add varying volumes of methyl acetate (MeOAc) – 1 mL, 3 mL, or 5 mL – to the colloidal UP PQD solution before the first centrifugation step [23].

- Ligand Removal: Centrifuge the mixture at 6000 rpm for 15 minutes and discard the supernatant containing residual precursors, excess free ligands, and detached ligands [23].

- Redispersion: Redisperse the remaining sediment in 1 mL of chloroform and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove large aggregated particles [23].

- Classification: Label the purified FAPbI₃ CQDs processed with different MeOAc volumes as LP1, LP3, and LP5, corresponding to MeOAc volumes of 1, 3, and 5 mL, respectively [23].

This purification process achieves approximately 85% ligand removal efficiency as confirmed by ¹H NMR analysis [22].

Sequential Solid-State Multiligand Exchange

The sequential solid-state multiligand exchange process represents the innovative core of this protocol, enabling the replacement of long-chain insulating ligands with shorter conductive alternatives while passivating surface defects.

Procedure:

- Thin Film Preparation: Deposit the purified PQD solution onto the target substrate using spin-coating or drop-casting techniques to form a solid thin film [22] [23].

- MPA/FAI Solution Preparation: Prepare a ligand exchange solution containing 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) in methyl acetate (MeOAc). Optimal concentrations should be determined empirically but typically range from 0.5-2 mg/mL for MPA and 1-3 mg/mL for FAI [22].

- Sequential Treatment: Gently apply the MPA/FAI solution to the solid-state PQD film using spin-coating or drop-casting methods, ensuring complete coverage without dissolving the film [22] [23].

- Incubation: Allow the film to incubate with the ligand exchange solution for 30-60 seconds to enable complete ligand substitution [22].

- Rinsing: Rinse the film gently with fresh MeOAc to remove excess ligands and reaction byproducts [22] [23].

- Drying: Carefully dry the film under a stream of nitrogen or gentle heating (50-70°C) for 5-10 minutes [22].

This sequential multiligand exchange process successfully passivates the nanocrystals with short-chain MPA and FAI ligands, as confirmed by ¹H NMR analysis [22].

Photovoltaic Device Fabrication

The application of ligand-exchanged PQDs in n-i-p structured solar cells demonstrates the technological relevance of this protocol.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrates sequentially in detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol under ultrasonication [23].

- Electron Transport Layer: Deposit a compact SnO₂ electron transport layer from a colloidal precursor using spin-coating followed by annealing at 150°C for 30 minutes [23].

- Active Layer Deposition: Deposit the ligand-exchanged FAPbI₃ PQD active layer using layer-by-layer spin-coating with MeOAc rinsing between each layer to remove residual solvents [22] [23].

- Hole Transport Layer: Deposit the spiro-OMeTAD hole transport layer by spin-coating a chlorobenzene solution containing 4-tert-butylpyridine (TBP) and lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (Li-TFSI) dopants [23].

- Electrode Deposition: Thermally evaporate gold or silver electrodes (80-100 nm thickness) through a shadow mask to complete the device structure [23].

Data Analysis and Performance Metrics

The efficacy of sequential solid-state multiligand exchange is quantitatively demonstrated through comprehensive material and device characterization. The following data represent typical results obtained using the described protocol.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PQD Photovoltaic Devices Before and After Multiligand Exchange

| Performance Parameter | Before Ligand Exchange | After MPA/FAI Exchange | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Density (mA cm⁻²) | Baseline | ~+2 mA cm⁻² increase | Significant enhancement [22] |

| Power Conversion Efficiency (%) | Baseline | 28% improvement | Substantial relative increase [22] |

| Hysteresis Behavior | Pronounced hysteresis | Reduced hysteresis | Improved device characteristics [22] |

| Operational Stability | Moderate stability | Enhanced stability | Extended device lifetime [22] |

| Film Conductivity | Limited by long-chain ligands | Enhanced conductivity | Improved charge transport [22] [23] |

Characterization techniques including photoluminescence spectroscopy and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy confirm that the hybrid MPA/FAI passivation improves thin-film conductivity and quality by reducing inter-dot spacing and defects, thereby mitigating vacancy-assisted ion migration [22] [23].

The relationship between material properties and device performance can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Relationship between material properties and device performance enhancements resulting from sequential multiligand exchange.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Successful implementation of sequential solid-state multiligand exchange requires attention to potential challenges and optimization opportunities.

Common Issues and Solutions:

- PQD Aggregation During Purification: Optimize MeOAc volume (LP3 conditions typically provide optimal balance) and minimize processing time to reduce ligand loss [23].

- Incomplete Ligand Exchange: Ensure proper MPA/FAI concentration and sufficient incubation time; verify exchange efficiency through ¹H NMR analysis [22].

- Film Dissolution During Solid-State Exchange: Control solvent polarity and application technique to maintain film integrity while enabling ligand diffusion [22] [23].

- Reduced Photoluminescence Quantum Yield: Optimize MPA/FAI ratio to balance conductivity enhancement with surface passivation quality [24].

Optimization Guidelines:

- Systematically vary MPA and FAI concentrations to achieve optimal balance between charge transport and defect passivation [22].

- Fine-tune MeOAc purification volume for specific PQD batch characteristics [23].

- Optimize solid-state exchange incubation time based on film thickness and packing density [22].

The sequential solid-state multiligand exchange protocol detailed herein represents a significant advancement in surface engineering techniques for perovskite quantum dots. By systematically replacing long-chain insulating ligands with short-chain MPA and FAI ligands, this approach simultaneously addresses the critical challenges of poor charge transport and surface defect-mediated recombination in PQD-based photovoltaics.

The documented enhancements in current density, power conversion efficiency, and device stability underscore the transformative potential of this methodology for advancing next-generation photovoltaic technologies. This protocol provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing this technique, with specific guidelines for material preparation, process optimization, and performance validation.

As research in perovskite quantum dots continues to evolve, the principles of sequential multiligand exchange established in this protocol may find broader applications in other optoelectronic devices, including light-emitting diodes, photodetectors, and quantum information technologies.

A Universal Strategy with NOBF4 for Facile Phase Transfer and Sequential Functionalization

The ability to engineer the surface properties of colloidal nanocrystals (NCs), including perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), is paramount for advancing their application in optoelectronics, bioimaging, and catalysis [25] [26] [27]. The surface chemistry of these nanoscale materials profoundly affects their physical and chemical properties, yet a significant challenge lies in manipulating these surfaces without compromising the NC's structural integrity or functionality [26]. This application note details a generalized ligand-exchange strategy utilizing Nitrosonium tetrafluoroborate (NOBF4), a method that enables sequential surface functionalization and phase transfer of a wide range of NCs. This protocol is presented within the broader research context of developing robust surface ligand exchange techniques for PQDs, which are critical for improving charge transfer in photovoltaic devices and enhancing dispersibility for biological applications [25] [26]. The NOBF4 strategy is distinguished by its ability to replace pristine organic ligands with inorganic BF4− anions, facilitating stabilization in polar solvents and serving as a versatile platform for subsequent functionalization with diverse capping molecules [27] [28].

Key Principles and Quantitative Data

The NOBF4-mediated ligand exchange operates on the principle of replacing hydrophobic, long-chain organic ligands (e.g., oleate, oleylamine) with inorganic BF4− anions. This substitution transforms the NC surface from hydrophobic to hydrophilic, enabling phase transfer from non-polar solvents like hexane to polar aprotic solvents such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [26] [27]. A critical advantage of this method is the relatively weak binding affinity of the BF4− anions to the NC surface. This weakness prevents permanent ligand lock-in and allows for sequential, reversible surface functionalization through a secondary ligand exchange with a variety of capping molecules, including dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA) for bio-imaging applications [26]. This strategy has demonstrated exceptional universality, successfully applied to NCs of various compositions (metal oxides, metals, semiconductors), sizes, and shapes [27] [28].

Table 1: Summary of Nanocrystal Systems and Performance Metrics Utilizing the NOBF4 Ligand Exchange Strategy

| Nanocrystal Composition | Initial Ligand | Final Ligand/Application | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag2Te QDs | Oleylamine (OLA) | DHLA & RGD peptides for in vivo imaging | High-quality in vivo fluorescent imaging in the NIR-II window achieved. | [26] |

| CdZnSeS QDs | Oleic Acid (OAc) | Various capping molecules (OAc, OAm, TDPA) | Fully reversible phase transfer and surface functionalization demonstrated. | [26] |

| Ag2S NCs | Oleylamine (OLA) | 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) for HER | Enhanced HER activity with an overpotential of 52 mV and stable operation for 24 h. | [29] |

| Various NCs (Metal Oxides, Semiconductors) | Mixed organic ligands | Stabilization in DMF | NCs stabilized in polar media for years without aggregation or precipitation. | [27] [28] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NOBF4 Ligand Exchange

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation | Example Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrosonium Tetrafluoroborate (NOBF4) | Primary exchange reagent; replaces original organic ligands with BF4− anions. | Provides electrostatic stability in polar media. Handle with care as it is moisture-sensitive. | [26] [27] |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Polar, hydrophilic solvent for stabilizing NCs after NOBF4 treatment. | NCs can remain dispersed in DMF for long-term storage (>60 days). | [26] |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Solvent for preparing the NOBF4 solution added to the NC dispersion. | A common organic solvent with good solubility for NOBF4. | [26] |

| Dihydrolipoic Acid (DHLA) | Bidentate ligand for secondary functionalization; imparts water solubility and biocompatibility. | Used to functionalize Ag2Te QDs for subsequent conjugation with RGD peptides. | [26] |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Ligand for secondary functionalization; introduces carboxyl groups and enhances hydrophilicity. | Used on Ag2S NCs to boost Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) activity. | [29] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Primary Ligand Exchange and Phase Transfer using NOBF4

This protocol describes the initial replacement of native hydrophobic ligands with BF4− anions to transfer NCs into DMF [26].

- Preparation of NOBF4 Solution: In an inert atmosphere glovebox, prepare a 10 mg/mL solution of NOBF4 in anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM).

- NC Precipitation: To a dispersion of the as-synthesized NCs (e.g., CdZnSeS QDs capped with oleic acid) in a non-polar solvent like hexane (e.g., 2 mL), add the NOBF4/DCM solution (e.g., 0.5 mL).

- Initiation of Exchange: Shake the mixture vigorously at room temperature. The NCs will typically precipitate from solution within 5 minutes, indicating a dramatic change in surface properties.

- Isolation: Centrifuge the mixture (e.g., at 6000 rpm for 5 minutes) to pellet the NCs. Carefully decant and discard the supernatant.

- Redispersion and Phase Transfer: Add a polar, hydrophilic solvent such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) (e.g., 2 mL) to the pellet. Vortex or agitate gently until the NCs are fully dispersed, forming a clear colloidal solution.

- Purification (Optional): The NCs in DMF can be further purified by repeated precipitation using a non-solvent like acetone or toluene, followed by centrifugation and redispersion in DMF.

Protocol 2: Secondary Ligand Exchange with DHLA for Bio-application

This protocol follows the primary NOBF4 treatment, enabling functionalization for biological imaging [26].

- Preparation of DHLA Solution: Dissolve DHLA in DMF to create a concentrated solution (e.g., 50 mM).

- Mixing: Combine the DHLA solution with the NOBF4-treated NCs dispersed in DMF. The ratio of DHLA to NCs should be optimized, but a molar excess of DHLA is typically used.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to react for several hours (e.g., 2-4 hours) at room temperature with gentle stirring.

- Phase Transfer to Aqueous Buffer: After incubation, add a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution or other aqueous buffer to the mixture. The NCs should transfer from the DMF phase to the aqueous phase.

- Purification: Purify the water-dispersible NCs via dialysis against deionized water or size-exclusion chromatography to remove excess ligands and solvent residues. The resulting NCs can be further functionalized with targeting moieties like RGD peptides.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequential process of the universal NOBF4 ligand exchange strategy, from initial synthesis to final application.

Universal NOBF4 Ligand Exchange Workflow

The logical relationship between surface functionalization and enhanced material performance, particularly in electrocatalysis, is governed by the modified electronic properties at the NC surface. The diagram below outlines this pathway for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER).

Surface Functionalization to HER Enhancement

The NOBF4 ligand exchange strategy represents a significant advancement in the surface engineering of nanocrystals, offering a universal, facile, and sequential approach to functionalization. Its compatibility with diverse NC compositions and its ability to serve as a platform for further customization make it an invaluable tool in PQD research and beyond. The detailed protocols and data summaries provided herein offer researchers a robust framework for implementing this technique to develop next-generation nanomaterials for imaging, energy, and electronic applications.

Surface ligand exchange on perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a fundamental technique for tuning their optoelectronic properties and stability for applications in photovoltaics and light-emitting devices. Secondary functionalization extends this surface engineering by introducing targeting moieties, which reroute nanoparticles from their natural pathways to specific molecular targets in vivo. The Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide serves as a paradigm for this strategy, demonstrating how ligand exchange principles can be adapted to confer precise targeting capabilities for molecular imaging. This application note details the methodology for RGD peptide conjugation to nanoparticle surfaces and its validation for integrin-targeted imaging.

The RGD Peptide: Mechanism and Target

The RGD peptide is a tri-amino acid sequence (Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid) that acts as a minimal recognition motif for a family of cell-surface receptors known as integrins [30].

- Target Integrins: Key integrins overexpressed in disease states, particularly on angiogenic endothelial cells and many cancer cells, include αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1, and αvβ6 [30] [31]. The αvβ3 integrin is the most extensively studied target for RGD-based imaging probes.

- Mechanism of Action: The peptide sequence binds specifically to the extracellular domain of these integrins, facilitating receptor-mediated endocytosis of the functionalized nanoparticle [30]. This interaction provides the basis for specific accumulation at disease sites.

- Role in Ligand Exchange: Integrating the RGD peptide represents a secondary ligand exchange process, where a targeting ligand is introduced alongside or in place of the native stabilizing ligands on the PQD surface to actively target biological receptors.

The following diagram illustrates the structure of an RGD-functionalized nanoparticle and its pathway to cellular internalization.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conjugation of RGD Peptides to Nanoparticles via SPDP Chemistry

This protocol describes the functionalization of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein (rHDL) nanoparticles with cyclic RGD peptides using the heterobifunctional crosslinker N-succinimidyl-3-(2-pyridyldithio)-propionate (SPDP), a method adaptable to PQD systems [32].

Materials

- Nanoparticles: Reconstituted HDL (rHDL) nanoparticles or other core nanoparticles (e.g., PQDs with a stable ligand shell).

- Targeting Ligand: Cyclic 5-mer RGD peptide (c[RGDf(S-acetylthioacetyl]K).

- Crosslinker: SPDP (N-succinimidyl-3-(2-pyridyldithio)-propionate).

- Buffers: HEPES buffer (pH 6.7), PBS (pH 7.4), hydroxylamine-HCl/EDTA deacetylation solution.

- Purification Devices: Vivaspin 6 centrifugal filter devices (10,000 kDa MWCO).

Procedure

Activation of Nanoparticles:

- Transfer rHDL nanoparticles into HEPES buffer and dilute to a concentration of 1 mg/mL (based on apoAI protein content).

- Add a 20-fold molar excess of SPDP (in dimethylformamide) relative to apoAI.

- Incubate the reaction mixture at room temperature for 2 hours with gentle agitation.

- Purify the SPDP-activated nanoparticles (rHDL-SPDP) from unreacted crosslinker using a Vivaspin 6 centrifugal filter device, washing thoroughly with HEPES buffer.

Preparation of RGD Peptide:

- Deacetylate the cyclic RGD peptide to expose the free thiol group by dissolving it in 0.05 M HEPES buffer containing 0.05 M hydroxylamine-HCl and 0.03 mM EDTA (pH 7.0).

- Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature.

Conjugation Reaction:

- Add the deacetylated RGD peptide to the purified rHDL-SPDP solution in HEPES buffer.

- Allow the reaction to proceed at 4°C overnight.

- Purify the final product (rHDL-RGD) by exchanging the buffer to PBS using a Vivaspin centrifugal filter device.

Quality Control:

- Determine the mean particle size and ζ-potential by dynamic light scattering.

- Confirm successful conjugation using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

Protocol 2: In Vivo MRI of RGD-Targeted Probes

This protocol validates the targeting efficacy and imaging performance of the RGD-functionalized probe in vivo using a murine xenograft model [33].

Materials

- Animals: Nude mice bearing human tumor xenografts (e.g., U87MG glioblastoma).

- Imaging Probes: RGD-functionalized probe (e.g., Gd₃L₃-RGD for MRI).

- Control Probes: Non-targeted version of the same probe or RGD-functionalized probe co-injected with excess free RGD as a competitor.

- Instrumentation: 7 T MRI scanner.

Procedure

Probe Administration:

- Divide mice into two experimental sets (n=3 per set).

- Set 1 (Experimental): Intravenously inject the RGD-functionalized probe (e.g., [Gd³⁺] = 5.0 mM).

- Set 2 (Control): Inject the same probe cocktail supplemented with a 5-fold molar excess of non-functionalized RGD peptide to compete for integrin binding sites.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging:

- Place anesthetized mice in the MRI scanner.

- Acquire T₁-weighted images at multiple time points post-injection (e.g., immediately, 1, 2, and 3 hours) using a standardized pulse sequence.

- Define a region of interest (ROI) encompassing the tumor and a contralateral control tissue.

Data Analysis:

- Quantify the mean signal intensity within the tumor ROI over time for both experimental and control groups.

- Calculate the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) or contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR).

- Compare the signal kinetics and retention time between the targeted probe and the control group.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Performance of RGD-Functionalized Probes

The tables below summarize key characterization data and in vivo performance metrics for RGD-functionalized imaging probes, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Physicochemical Properties of RGD-Functionalized Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle Type | Mean Size (nm) | ζ-Potential (mV) | Targeting Ligand | Key Functionalization Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rHDL-RGD | ~10-15 | Data Not Provided | cyclic RGD | Successful conjugation confirmed by FTIR | [32] |

| Gd₃L₃-RGD | < 10 (Molecular Probe) | Data Not Provided | GRGDGKGKGK peptide | Trimeric probe; +110% r₁ relaxivity enhancement with Ca²⁺ | [33] |

| APG/RGD-DOX | ~15-20 | Data Not Provided | RGD-4C peptide | Successful binding confirmed by FTIR, UV-Vis, Zeta sizer | [34] |

Table 2: In Vivo Imaging Performance of RGD-Targeted Probes

| Imaging Probe | Disease Model | Key Finding | Quantitative Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rHDL-RGD (NIR/MRI) | Human xenograft mouse model | Specific association with tumor endothelial cells | Confocal microscopy showed rHDL-RGD in tumor vasculature vs. interstitial space for controls | [32] |

| Gd₃L₃-RGD (MRI) | Rat somatosensory cortex | Longer retention time due to RGD-integrin interaction | Signal washout significantly slower vs. probe with competitive RGD blocking | [33] |

| RGD-functionalized rHDL (NIR) | Human xenograft mouse model | Different tumor accumulation kinetics | NIR imaging showed distinct kinetic profiles for RGD vs. non-targeted nanoparticles | [32] |

The experimental workflow for synthesizing, characterizing, and validating RGD-functionalized nanoparticles is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RGD Functionalization and Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|