Surface Ligand Engineering in Perovskite Quantum Dots: Controlling Electronic Properties for Advanced Biomedical and Clinical Applications

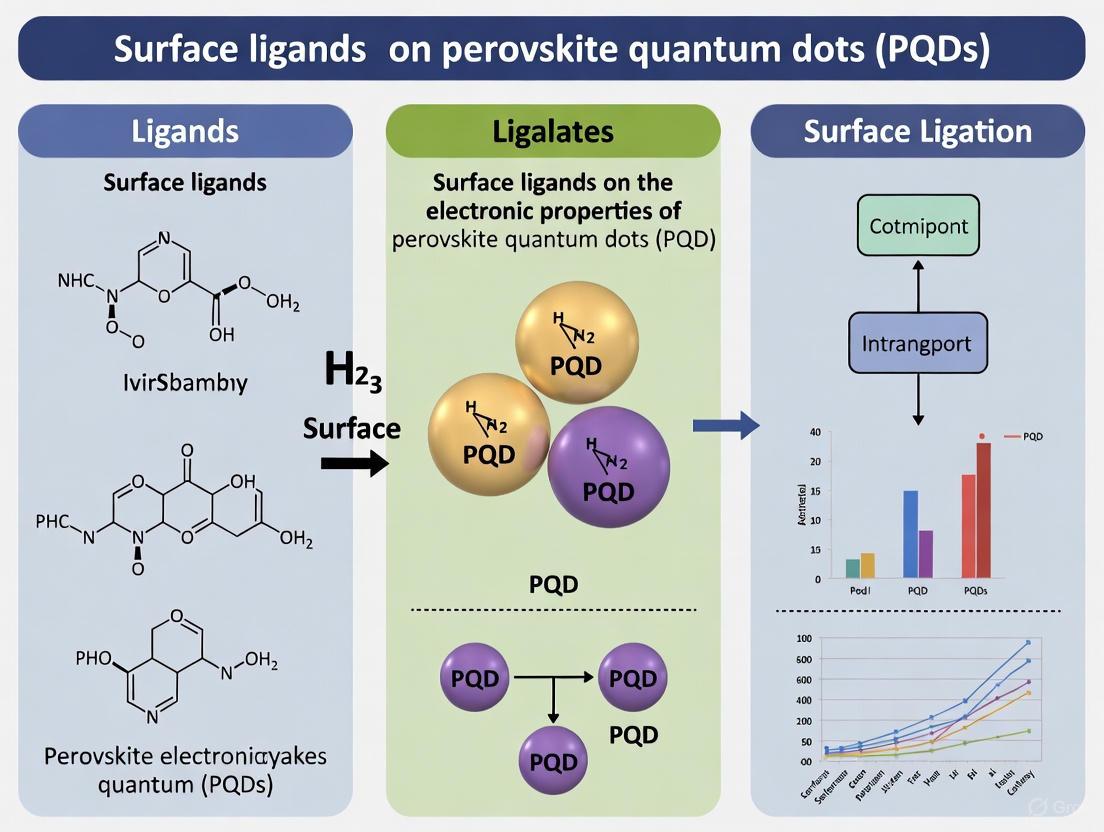

This article comprehensively explores the pivotal role of surface ligand chemistry in determining the electronic and optoelectronic properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs).

Surface Ligand Engineering in Perovskite Quantum Dots: Controlling Electronic Properties for Advanced Biomedical and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the pivotal role of surface ligand chemistry in determining the electronic and optoelectronic properties of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details how the strategic design of capping ligands—from foundational passivation to advanced dual-ligand systems—governs charge transport, stability, and functionality. The discussion bridges fundamental synthesis and characterization methods with practical applications in sensing and diagnostics, addressing key challenges in optimization and validation. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs and established principles, this review provides a framework for leveraging ligand engineering to develop next-generation, high-performance PQD-based tools for biomedical research and clinical deployment.

The Molecular Foundation: How Surface Ligands Dictate PQD Electronic Structure and Stability

The Critical Role of Surface Passivation in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) represent a revolutionary class of semiconducting materials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including tunable bandgaps, high photoluminescence quantum yields, and superior defect tolerance. [1] However, the extensive surface-to-volume ratio of these nanoscale materials makes their electronic properties profoundly dependent on surface chemistry. The dynamic binding of inherent long-chain insulating ligands creates numerous surface defects that severely compromise photovoltaic performance by trapping charge carriers and inducing non-radiative recombination. [2] Surface passivation addresses these challenges by substituting insulating ligands with shorter, conductive counterparts and filling uncoordinated ionic sites, thereby enhancing electronic coupling between adjacent PQDs and improving charge transport throughout the solid film. [3]

The imperative for passivation stems from the fundamental synthesis process of PQDs. Colloidal synthesis utilizing long-chain oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) ligands is essential for producing high-quality, monodispersed PQDs, but these very ligands become detrimental in final devices due to their insulating properties. [4] This creates a paradox where the ligands necessary for synthesis become impediments to performance, necessitating sophisticated post-synthetic ligand exchange strategies to transform electronically isolated PQDs into functionally connected solids capable of efficient charge transport for photovoltaic applications.

Key Challenges in PQD Surface Engineering

Incomplete Ligand Exchange and Surface Defects

Conventional ligand exchange processes using ester antisolvents like methyl acetate (MeOAc) face significant limitations. Under ambient conditions, these esters hydrolyze inefficiently, failing to generate adequate target ligands for complete surface coverage. [1] This results in the predominant dissociation of pristine insulating oleate ligands without sufficient substitution by conductive counterparts, creating extensive surface vacancy defects that capture charge carriers and reduce device performance. [1]

Structural Instability During Processing

The ionic nature of perovskite crystals makes them particularly vulnerable to polar solvents used in conventional ligand exchange processes. These solvents inevitably strip away not only surface-bound ligands but also essential metal cations and halides from the PQD surface. [4] This destructive process generates uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites that act as non-radiative recombination centers and create penetration pathways for destructive environmental species like oxygen and water molecules, ultimately compromising both performance and operational stability.

Trade-offs Between Conductivity and Stability

A fundamental challenge in PQD surface engineering lies in balancing the enhanced electronic coupling achieved through shorter ligands against the improved environmental stability provided by more robust, longer ligands. While shorter ligands reduce inter-dot distance and improve charge transport, they often provide insufficient protection against environmental factors. Additionally, achieving homogeneous crystallographic orientations and minimal particle agglomeration during film assembly remains technically challenging, directly impacting the reproducibility and performance of PQD solar cells.

Advanced Passivation Strategies and Mechanisms

Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate that creating alkaline environments during ligand exchange significantly enhances ester hydrolysis thermodynamics and kinetics. This approach renders ester hydrolysis thermodynamically spontaneous and lowers reaction activation energy by approximately nine-fold, enabling rapid substitution of pristine insulating oleate ligands with up to twice the conventional amount of hydrolyzed conductive counterparts. [1]

Experimental Protocol: The alkaline treatment involves tailoring potassium hydroxide (KOH) coupled with methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent for interlayer rinsing of PQD solids. Specifically, hybrid FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQD solid films are rinsed with MeBz antisolvent containing controlled concentrations of KOH under ambient conditions (~30% relative humidity). This facilitates efficient hydrolysis of MeBz into benzoate ligands that replace pristine OA⁻ ligands while preserving perovskite core structural integrity. The resulting PQD light-absorbing layers exhibit fewer trap-states, homogeneous orientations, and minimal particle agglomerations. [1]

Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering

The Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering (CSME) strategy disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of proton exchange between OA and OAm by inducing an amidation reaction. This approach advances insulating ligand desorption from PQD surfaces while enabling short-chain conjugated ligands with high binding energy to efficiently occupy the resulting surface vacancies. [3]

Experimental Protocol: The CSME process involves treating FAPbI₃ PQD films with a solution containing short-chain conjugated ligands that preferentially bind to surface vacancy sites. This is followed by thermal annealing to promote amidation between residual OA and OAm, further enhancing ligand desorption and electronic coupling. The process significantly suppresses trap-assisted nonradiative recombination, enabling FAPbI₃ PQD solar cells to achieve record efficiencies of up to 19.14%. [3]

Nonpolar Solvent-Based Covalent Passivation

This innovative approach utilizes covalent short-chain triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) ligands dissolved in nonpolar solvents (e.g., octane) to passivate uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites via strong Lewis acid-base interactions. The nonpolar solvent completely preserves PQD surface components while enabling effective trap passivation. [4]

Experimental Protocol: After conventional ligand exchange using ionic short-chain ligands in polar solvents, CsPbI₃ PQD solids are treated with TPPO ligand solution (1-2 mg/mL in octane) via spin-coating or immersion. The TPPO solution covalently coordinates with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites without damaging the PQD surface, followed by mild thermal treatment (60-70°C) to remove residual solvent. This approach simultaneously improves photovoltaic performance and ambient stability, with devices maintaining over 90% of initial efficiency after 18 days of storage under ambient conditions. [4]

Complementary Dual-Ligand Reconstruction

This strategy employs trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and phenylethyl ammonium iodide to form a complementary dual-ligand system on the PQD surface through hydrogen bonds. This system stabilizes the surface lattice while maintaining good colloidal dispersion and improving inter-dot electronic coupling in PQD solids. [2]

Experimental Protocol: CsPbI₃ PQDs in solution are treated with sequential additions of trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate (0.1-0.3 mM) and phenylethylammonium iodide (0.2-0.4 mM) in anhydrous solvent with continuous stirring. The complementary ligands form a hydrogen-bonded network on the PQD surface, enhancing both optoelectronic properties and environmental stability. This approach has enabled a record efficiency of 17.61% in inorganic PQD solar cells. [2]

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Advanced PQD Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | PQD Composition | Certified PCE (%) | Stability Retention | Key Improvement Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline-Augmented Antisolvent Hydrolysis [1] | FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ | 18.30 (certified) | Improved operational stability | 2x ligand substitution; 9-fold reduced activation energy |

| Consecutive Surface Matrix Engineering [3] | FAPbI₃ | 19.14 | Enhanced operation stability | Disrupted OA-OAm equilibrium; Reduced trap density |

| Nonpolar Solvent-Based Covalent Passivation [4] | CsPbI₃ | 15.40 | >90% after 18 days | Strong Lewis acid-base coordination; Preserved surface components |

| Complementary Dual-Ligand Reconstruction [2] | CsPbI₃ | 17.61 | Improved environmental stability | Hydrogen-bonded ligand network; Uniform stacking orientation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PQD Surface Passivation Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Passivation | Application Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl Benzoate (MeBz) Antisolvent | Medium-polarity ester that hydrolyzes to conductive benzoate ligands | Interlayer rinsing of PQD solid films under controlled humidity |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Creates alkaline environment to enhance ester hydrolysis kinetics | Coupled with MeBz antisolvent at optimized concentrations |

| Triphenylphosphine Oxide (TPPO) | Covalent short-chain ligand for Lewis acid-base coordination with Pb²⁺ sites | Dissolved in nonpolar octane solvent (1-2 mg/mL) for post-treatment |

| Phenylethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Short-chain cationic ligand for replacing OLA ligands | Dissolved in ethyl acetate for A-site ligand exchange |

| Trimethyloxonium Tetrafluoroborate | Anionic component for complementary dual-ligand system | Sequential addition with PEAI for hydrogen-bonded surface network |

| Metal Salts (In³⁺, Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺) | Strips organic ligands and passivates Lewis basic sites | DMF solutions for phase transfer ligand exchange |

Experimental Workflows and Mechanism Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making workflow for selecting appropriate PQD passivation methodologies based on specific research objectives and material constraints:

The molecular-level mechanism of PQD surface passivation is illustrated below, showing how different ligand systems interact with the perovskite crystal structure to enhance both performance and stability:

Surface passivation stands as an indispensable component in the development of high-performance PQD optoelectronic devices. The strategic replacement of pristine insulating ligands with carefully engineered conductive counterparts directly addresses the fundamental challenge of balancing charge transport with structural stability in PQD solids. Advanced passivation strategies, including alkaline-augmented hydrolysis, consecutive surface matrix engineering, nonpolar covalent passivation, and complementary dual-ligand systems, have collectively driven remarkable progress in PQD solar cell performance, with certified power conversion efficiencies now approaching 20%. [1] [3]

Future research directions will likely focus on developing multifunctional ligand systems that simultaneously address electronic, structural, and environmental stability challenges. The integration of in-situ characterization techniques to monitor passivation efficacy in real-time, coupled with machine learning approaches to design optimal ligand structures, represents a promising frontier. As understanding of PQD surface chemistry deepens, precise control over interfacial energetics and defect passivation will unlock the full potential of perovskite quantum dots for next-generation photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications.

Surface passivation represents a cornerstone technique in materials science and engineering, critical for mitigating performance-degrading defects in semiconductors and nanomaterials. Within the specific context of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) electronic properties research, this process is predominantly governed by the strategic application of surface ligands. These organic or inorganic molecules functionalize the nanomaterial surface, neutralizing electronically active defects known as dangling bonds. The ensuing modification of surface states within the band gap is paramount, as it directly dictates key electronic properties including charge carrier mobility, non-radiative recombination rates, and operational stability. A profound understanding of these mechanisms is not merely academic; it is the key to unlocking the full potential of PQDs in optoelectronic devices, from high-efficiency solar cells to next-generation light-emitting diodes. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the atomic-level mechanisms of surface passivation, detailing the specific interactions between ligands and defects, and presents the experimental methodologies essential for probing these critical interfaces.

Fundamental Defect Types and Passivation Principles

The Origin and Impact of Dangling Bonds

In any terminated crystalline or amorphous structure, a dangling bond is an unsatisfied valence on a surface atom that results from the abrupt interruption of the periodic lattice. These defects create electronic states within the forbidden band gap of the material, which act as traps for charge carriers. The trapping process facilitates non-radiative recombination—a primary loss mechanism in photovoltaic devices—and degrades charge transport properties by scattering mobile carriers. In perovskite quantum dots, which possess a high surface-to-volume ratio, the impact of these surface defects is profoundly magnified, making effective passivation not a mere enhancement but a fundamental requirement for functional devices [5].

Parallels in Amorphous Semiconductor Systems

The critical nature of defect passivation is vividly illustrated in hydrogenated amorphous silicon nitride (a-Si3N4), a material widely used in electronic devices. In this system, hydrogen plays a role analogous to surface ligands in QDs. Hydrogen atoms passivate both silicon and nitrogen dangling bonds, effectively "healing" coordination defects and purging the associated gap states. This restorative action enhances the material's dielectric properties. However, this role is multifaceted; the incorporation of hydrogen can also induce Si–N bond breaking, particularly in strained regions of the amorphous network, introducing new structural weaknesses. This duality underscores a universal principle in passivation: the healing agent must be carefully selected and controlled to avoid unintended detrimental effects on the host matrix [6].

Classification of Surface Ligands and Their Mechanisms

Surface ligands for PQDs can be systematically categorized based on their binding functional groups, which directly determine their passivation mechanism, binding strength, and resultant effect on the electronic structure of the nanomaterial [5].

Table 1: Classification of Common Surface Ligands by Functional Group

| Functional Group | Example Ligands | Binding Target (Ion) | Primary Mechanism | Impact on Electronic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylate | Oleic Acid | Pb²⁺ | Coordinate covalent bond | Good passivation; can limit inter-dot coupling |

| Amine | Oleylamine | Halide (I⁻, Br⁻) | Dative covalent bond | Good passivation; can limit inter-dot coupling |

| Ammonium | Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Anionic site (Halide) | Ionic bond / Lattice incorporation | Strong binding; can enhance stability and charge transport |

| Phosphate | - | Pb²⁺ | Strong coordinate covalent bond | Enhanced stability; effective defect passivation |

| Sulfonate | - | Pb²⁺ | Strong coordinate covalent bond | Enhanced stability; effective defect passivation |

Monodentate and Bidentate Passivation

The coordination chemistry of the ligand-functional group interaction is a key determinant of passivation efficacy. Monodentate ligands, such as alkyl amines, bind to a single surface Pb²⁺ ion through a dative bond. While this neutralizes one dangling bond, the binding can be dynamic and relatively weak, leading to ligand desorption and defect regeneration. Bidentate ligands, featuring two coordinating atoms (e.g., in certain dicarboxylate species), can chelate a single Pb²⁺ ion or bridge two adjacent ions. This chelation effect results in significantly stronger binding constants and more robust, durable passivation of the surface [5].

The Complementary Dual-Ligand Mechanism

A sophisticated advancement in passivation strategy involves the use of multiple ligands that work synergistically. A prominent example is a system comprising trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and phenylethyl ammonium iodide (PEAI). In this configuration, the ligands form a complementary dual-ligand system on the PQD surface through hydrogen bonds. This network creates a more complete and stable surface coverage, where one ligand species may passivate one type of defect (e.g., Pb²⁺ sites) while the other targets another (e.g., halide sites). This cooperation not only stabilizes the surface lattice but also improves inter-dot electronic coupling in solid films, leading to superior charge transport and record-high efficiencies in quantum dot solar cells [2].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Studies and Passivation

Synthesis of Core-Shell Perovskite Quantum Dots

Objective: To synthesize MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ core-shell PQDs for advanced in situ passivation studies [7].

Materials:

- Methylammonium bromide (MABr) and Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂): Core precursor materials.

- Tetraoctylammonium bromide (t-OABr): Shell precursor.

- Oleylamine (OAm) and Oleic Acid (OA): Coordinating ligands to control growth and stabilize nanoparticles.

- Dimethylformamide (DMF) and Toluene: Solvents.

Methodology:

- Core Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 0.16 mmol MABr and 0.2 mmol PbBr₂ in 5 mL DMF. Add 50 µL OAm and 0.5 mL OA under continuous stirring.

- Shell Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 0.16 mmol t-OABr in 5 mL DMF using a separate vial, following the same protocol.

- Nanoparticle Growth: Heat 5 mL of toluene to 60°C in an oil bath with stirring.

- Core Injection: Rapidly inject 250 µL of the core precursor solution into the heated toluene, initiating the formation of MAPbBr₃ core nanoparticles.

- Shell Growth: Inject a controlled amount of the t-OABr-PbBr₃ shell precursor into the reaction mixture. The formation of core-shell nanoparticles is indicated by the emergence of a green color. Allow the reaction to proceed for 5 minutes.

- Purification: Transfer the solution to a centrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes. Discard the precipitate.

- Subject the supernatant to a second centrifugation with isopropanol at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Storage: Redisperse the final precipitate in chlorobenzene for subsequent applications [7].

In Situ Integration of PQDs for Bulk Perovskite Passivation

Objective: To incorporate pre-synthesized core-shell PQDs during the fabrication of a bulk perovskite film to passivate grain boundaries and surface defects [7].

Materials:

- Fabricated Core-Shell PQDs (from Protocol 4.1)

- Perovskite Precursors: PbI₂, FAI, PbBr₂, MACl, MABr

- Solvents: DMF, DMSO, Chlorobenzene (antisolvent)

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean FTO/ITO substrates sequentially in soap solution, distilled water, ethanol, and acetone. Treat with UV-ozone for 15 minutes.

- Transport Layer Deposition: Deposit compact and mesoporous TiO₂ layers via spray pyrolysis and spin-coating, followed by annealing.

- Perovskite Film Fabrication with PQDs:

- Prepare the standard perovskite precursor solution (e.g., 1.6 M PbI₂, 1.51 M FAI, etc., in DMF:DMSO).

- Spin-coat the perovskite precursor onto the substrate.

- During the antisolvent dripping step (critical for crystallization), use a chlorobenzene antisolvent containing the dispersed core-shell PQDs at an optimal concentration (e.g., 15 mg/mL).

- Annealing: Anneal the film to form the crystalline perovskite layer. The PQDs, introduced in situ, become integrated at grain boundaries and surfaces, epitaxially passivating defects.

- Device Completion: Subsequently deposit hole-transport and electrode layers to complete the solar cell device [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of the in situ passivation process:

Characterization Techniques for Assessing Passivation Efficacy

The success of a passivation strategy must be quantitatively evaluated through a suite of characterization techniques.

Table 2: Key Characterization Methods for Passivation Quality

| Technique | Measured Parameter | Information on Passivation |

|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Efficiency of photon emission | Direct measure of non-radiative recombination suppression. |

| Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) | Carrier lifetime | Quantifies trap density; longer lifetimes indicate better passivation. |

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Vibrational modes of surface bonds | Confirms ligand binding and identifies functional groups present. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface elemental composition & bonding | Identifies chemical states of surface atoms and ligand attachment. |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Unpaired spin density | Directly probes the concentration of paramagnetic dangling bonds. |

| Solar Cell J-V Measurement | PCE, Voc, Jsc, FF | Device-level performance metrics impacted by reduced recombination. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Surface Passivation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Common coordination ligand for Pb²⁺ sites. | Colloidal stabilization and preliminary passivation during PQD synthesis [7]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Common passivation ligand for halide sites. | Colloidal stabilization and preliminary passivation during PQD synthesis [7]. |

| Phenethylammonium Iodide (PEAI) | Ionic ammonium ligand for strong surface binding. | Used in complementary dual-ligand systems for enhanced stability and performance [2]. |

| Trimethyloxonium Tetrafluoroborate | Reactive organo-oxygen compound. | Partner in hydrogen-bonded dual-ligand systems for surface reconstruction [2]. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Bulky ammonium salt for shell formation. | Creating a wider-bandgap shell around PQD cores in core-shell architectures [7]. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr₂) | Source of Pb²⁺ ions. | Core and shell precursor; used to remedy lead-site surface defects. |

| Methylammonium Bromide (MABr) | Source of organic cation and halide. | Core precursor; can be used in ligand exchange for surface repair. |

Visualization of Passivation Mechanisms

The following diagram synthesizes the core concepts of defect types and ligand passivation mechanisms discussed in this guide, illustrating how different ligands target specific surface defects on a perovskite quantum dot.

The deliberate passivation of surface defects is an indispensable unit operation in the fabrication of high-performance electronic and optoelectronic materials. The mechanisms—ranging from the simple coordination of a single monodentate ligand to the sophisticated synergy of a complementary dual-ligand system—provide a powerful toolkit for materials engineers. The experimental protocols and characterization methods outlined herein form the foundation for rigorous research in this domain. As the field progresses, the development of novel ligand chemistries and integration strategies, particularly those that enable robust, long-term stability under operational stresses, will be critical. Mastering these surface passivation mechanisms is a fundamental prerequisite for advancing the broader thesis on the role of surface ligands in determining the ultimate electronic properties and commercial viability of perovskite quantum dot technologies.

In the realm of colloidal nanotechnology, surface ligands are not merely passive stabilizers but active determinants of nanocrystal fate and function. These organic molecules covalently bound to nanocrystal surfaces dictate critical aspects of material behavior including colloidal stability, electronic properties, and application performance. For perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), ligand chemistry becomes particularly crucial due to the dynamic nature of their surfaces and heightened susceptibility to environmental degradation. Oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) have emerged as the canonical ligand pair in PQD synthesis, forming the foundational chemical environment that enables precise nanocrystal growth and stabilization. Their amphiphilic character and complementary binding modes create a synergistic system that balances nucleation control with post-synthesis processability. This review examines the fundamental roles of OA and OLA in PQD technology, their inherent limitations, and advanced engineering strategies that build upon this classical chemistry to push the boundaries of optoelectronic performance.

Fundamental Chemistry of OA and OLA

Oleic acid and oleylamine represent two of the most ubiquitous ligands in colloidal nanocrystal synthesis, with their effectiveness stemming from their molecular structure and complementary binding functionalities.

Molecular Structure & Binding Modes: OA (C₁₇H₃₃COOH) is a monounsaturated fatty acid featuring a carboxylic acid headgroup, while OLA (C₁₈H₃₅NH₂) is its amine-terminated counterpart. During perovskite quantum dot synthesis, the carboxylate group of OA coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the crystal surface, while the ammonium group of OLA (formed through protonation) interacts with halide anions, creating a balanced passivation system [8]. This acid-base pairing is not merely coincidental but functionally critical, as the two components work in concert to stabilize the ionic perovskite lattice.

The OA:OLA Ratio as a Synthetic Control Knob: The relative concentration ratio of OA to OLA serves as a powerful parameter for dictating nanocrystal morphology and dimensionality. Research demonstrates that regulating the protonation behavior of OLA and the competitive lattice-forming behavior between oleylammonium cations and cesium ions directly influences dimensional outcomes [8]. By precisely tuning the OA/OLA feed ratio, synthesis can be directed toward either two-dimensional nanoplatelets or three-dimensional nanocubes, enabling spectral control over optical properties without changing material composition.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Common Ligands in PQD Synthesis

| Ligand | Chemical Formula | Head Group | Primary Binding Site | Role in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | C₁₇H₃₃COOH | Carboxylic acid | Pb²⁺ ions | Surface passivation, growth control |

| Oleylamine (OLA) | C₁₈H₃₅NH₂ | Amine | Halide ions (I⁻, Br⁻) | Charge balance, colloidal stability |

| Octylphosphonic Acid (OPA) | C₈H₁₇PO(OH)₂ | Phosphonic acid | Pb²⁺ ions | Defect passivation, conductivity enhancement |

| Succinic Acid (SA) | C₄H₆O₄ | Dicarboxylic acid | Pb²⁺ ions | Bidentate binding, water compatibility |

Experimental Protocols in Ligand Engineering

Standard Hot-Injection Synthesis with OA/OLA

The hot-injection method represents the most widely employed approach for producing high-quality CsPbX₃ perovskite quantum dots with narrow size distributions. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

Precursor Preparation: Combine cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 2.49 mmol) with oleic acid (2.5 mL) and 1-octadecene (ODE, 30.0 mL) in a three-neck flask. Degas and dry under vacuum for 1 hour at 120°C, then heat to 150°C under N₂ until complete dissolution to form cesium oleate [9].

Reaction Mixture Setup: In a separate flask, combine lead precursor (e.g., PbI₂ for CsPbI₃) with ODE, OA, and OLA. The typical OA:OLA ratio ranges from 1:1 to 1:2 for optimal cubic phase stabilization. Degas the mixture under vacuum at 120°C for 30-60 minutes to remove residual water and oxygen [10].

Quantum Dot Formation: Rapidly inject the cesium oleate precursor into the reaction flask maintained at 170°C. The reaction temperature critically determines nucleation and growth kinetics, with 170°C identified as optimal for CsPbI₃ PQDs exhibiting maximum photoluminescence intensity and narrowest emission linewidth [10].

Purification and Isolation: After 5-10 seconds of reaction, rapidly cool the mixture in an ice bath. Centrifuge the crude solution with antisolvents (typically ethyl acetate or acetone) to precipitate the quantum dots. Carefully decant the supernatant and redisperse the pellet in non-polar solvents like hexane or toluene [10] [9].

Ligand Exchange and Modification Techniques

While OA and OLA excel during synthesis, their long aliphatic chains (C18) impede charge transport in solid-state films, necessitating post-synthetic ligand engineering:

Partial Ligand Exchange: Introduce short-chain ligands during or after synthesis to partially replace OA/OLA. For instance, the addition of octylphosphonic acid (OPA, C8) during synthesis creates a mixed-ligand system that enhances electrical conductivity from 5.3×10⁻⁴ to 1.1×10⁻³ S/m while maintaining colloidal stability [9].

Bidentate Ligand Strategies: Replace monodentate OA with bidentate ligands like succinic acid (SA) featuring two carboxylic acid groups. This creates stronger coordination with the perovskite surface through the chelate effect, significantly improving photoluminescence quantum yield and water stability [11].

Complementary Dual-Ligand Systems: Implement advanced resurfacing approaches using complementary ligand pairs that form hydrogen-bonded networks around the quantum dots. Systems incorporating trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate and phenylethyl ammonium iodide demonstrate improved inter-dot electronic coupling while maintaining good dispersion [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand Effects

The impact of ligand engineering on PQD performance can be systematically quantified through key optoelectronic metrics. Research demonstrates that strategic ligand modification significantly enhances device performance.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of PQDs with Different Ligand Systems

| Ligand System | PLQY (%) | Conductivity (S/m) | Device Performance | Stability (PL Retention) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional OA/OLA | 71.9 | 5.3 × 10⁻⁴ | Baseline | <50% after 7 days |

| OPA Modification | 98 | 1.1 × 10⁻³ | LED: 12.6% EQE, 10171 cd m⁻² | Not reported |

| TOP/TOPO Passivation | 16-18% enhancement | Not reported | Not reported | >70% after 20 days UV |

| L-Phenylalanine | 3% enhancement | Not reported | Not reported | Superior photostability |

| Complementary Dual-Ligand | Not reported | Improved inter-dot coupling | Solar cell: 17.61% efficiency | Enhanced environmental stability |

The data reveal several significant trends. First, the implementation of shorter-chain ligands like OPA substantially improves charge transport characteristics, as evidenced by the approximate doubling of film conductivity compared to conventional OA/OLA systems [9]. Second, alternative binding groups such as phosphonic acids (TOP, TOPO) and amino acids (L-phenylalanine) provide superior surface passivation, reducing non-radiative recombination pathways and enhancing photoluminescence quantum yield [10]. Third, advanced multi-ligand architectures enable simultaneous optimization of multiple properties, addressing the traditional trade-off between operational stability and electronic performance [2].

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies

Short-Chain Ligands for Enhanced Charge Transport

The insulating nature of long-chain OA and OLA ligands (approximately 2 nm chain length) creates significant barriers to inter-dot charge transport in solid-state films. To address this limitation, researchers have developed strategic ligand exchange approaches that introduce shorter-chain alternatives while maintaining adequate surface passivation:

Organic Phosphonic Acids: The substitution of OA with octylphosphonic acid (OPA) demonstrates the multifaceted benefits of short-chain ligands. OPA's phosphonic acid group forms a stronger coordinate bond with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ surface sites compared to carboxylic acids, leading to more effective defect passivation and remarkable PLQY values up to 98% [9]. Simultaneously, its shorter hydrocarbon chain (C8 vs C18) reduces inter-dot spacing, enhancing film conductivity from 5.3×10⁻⁴ to 1.1×10⁻³ S/m.

Inorganic Ligands: Beyond organic alternatives, inorganic ligands like halide salts (e.g., NH₄I) and pseudohalides provide ultracompact passivation layers that dramatically enhance inter-dot electronic coupling. These inorganic species create essentially ligand-free quantum dot surfaces with near-atomic contact between adjacent nanocrystals, enabling charge mobility values orders of magnitude higher than conventional OA/OLA-capped systems.

Multidentate Ligands for Enhanced Stability

The monodentate binding character of OA and OLA creates dynamic ligand binding with relatively low activation energies for desorption, leading to progressive surface degradation under operational conditions. Multidentate ligand strategies address this fundamental limitation:

Dicarboxylic Acid Systems: Ligands such as succinic acid (SA) featuring two carboxylic acid groups enable bidentate coordination with the perovskite surface. This chelate effect creates significantly more stable binding configurations, as demonstrated by theoretical calculations showing stronger binding energies compared to monodentate OA [11]. The improved binding affinity translates directly to enhanced environmental stability, particularly in aqueous environments.

Biomolecule Conjugation: The inherent limitations of OA/OLA become particularly pronounced in biological applications. Research shows that replacing OA/OLA with succinic acid enables subsequent functionalization with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters, creating reactive intermediates for biomolecular conjugation [11]. This approach facilitates the development of PQD-bioconjugates for sensing applications, achieving detection limits of 51.47 nM for bovine serum albumin while maintaining quantum dot stability in aqueous media.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful ligand engineering in perovskite quantum dots requires careful selection of chemical reagents and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key components for advanced ligand studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Ligands | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OLA) | Baseline synthesis, colloidal stability | Purification to remove oxidation products; optimal OA:OLA ratio critical |

| Short-Chain Ligands | Octylphosphonic acid (OPA), Octanoic acid (OTAc) | Enhanced charge transport, defect passivation | Balance between chain length and solubility; binding group affinity |

| Multidentate Ligands | Succinic acid (SA), Ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) | Improved binding stability, water compatibility | Chelate effect strength; potential for bridge bonding between QDs |

| Precision Additives | Trioctylphosphine (TOP), Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) | Surface defect passivation | Coordination with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions; 16-18% PL enhancement [10] |

| Amino Acid Ligands | L-phenylalanine, L-glutamic acid | Environmentally friendly alternatives, chiral properties | Steric effects of side chains; binding group availability |

| Purification Solvents | Hexane, Toluene, Ethyl acetate, Acetone | QD isolation, ligand excess removal | Polarity matching for precipitation; solvent quality for redispersion |

The chemistry of oleic acid and oleylamine represents both the foundation and frontier of perovskite quantum dot research. While their role as synthetic workhorses is firmly established, contemporary research has illuminated both their limitations and pathways to transcend them. The future of PQD ligand engineering lies in rational design strategies that move beyond single-ligand systems to multi-component, functionally integrated approaches. Promising directions include dynamic ligand systems that adapt to environmental conditions, computationally guided ligand discovery that predicts binding affinities and electronic effects, and bio-inspired approaches that mimic the sophisticated ligand management found in natural photosynthetic systems. As these advanced ligand paradigms mature, they will unlock the full potential of perovskite quantum dots across optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and biomedical applications, transforming these nanoscale materials from laboratory curiosities into technological mainstays.

Surface ligands are integral to the structure and function of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), serving not merely as passive stabilizing agents but as active determinants of their fundamental electronic characteristics. Within the context of advanced materials research for optoelectronics, the strategic engineering of ligand chemistry provides a powerful pathway to control core behaviors such as charge carrier mobility, band structure, and successful dopant integration. This whitepaper synthesizes recent scientific advances to elucidate the profound impact of ligand selection and modification on these key properties, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists aiming to optimize PQD performance for applications in photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and other quantum dot-based devices. The ensuing sections will detail the specific mechanisms of influence, supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies.

The Influence of Ligands on Band Gap and Exciton Dynamics

Ligands directly impact the electronic structure of PQDs, notably through surface chemistry that alters the density and localization of charge carriers. The band gap itself can be influenced indirectly through ligand-induced lattice strain and dimensionality changes, but the most direct electronic effects are observed in exciton relaxation and recombination dynamics.

Research on CdSe quantum dots has demonstrated that the presence of surface ligands, such as trimethylphosphine oxide or methylamine, significantly increases the rate of photoexcitation relaxation. The extensive hybridization between the electronic states of the quantum dot and the ligand molecules creates an efficient nonradiative relaxation channel, facilitating rapid exciton relaxation and electronic energy loss [12].

Furthermore, the modification of surface chemistry dictates how ligand bonding behaves in the excited states of the nanocrystals. Transient mid-IR absorption spectroscopy studies on PbS QDs reveal that the excited-state bonding is highly ligand-dependent. In oleate-passivated QDs, the overall Pb-O coordination decreases in the excitonic excited state, indicating a net weakening of ligand bonding. In contrast, for QDs passivated with 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA)—a ligand featuring both thiol and carboxylate anchoring groups—the localization of hole density near the thiol groups causes a uniform shift in the carboxylate vibrational features, signifying a change in surface charge density. This altered surface charge directly affects the energy and electron transfer processes at the nanocrystal surface, which are crucial for photocatalytic activity [13].

Ligand Engineering for Enhanced Charge Carrier Mobility

A primary challenge in PQD technology is the inherent trade-off between colloidal stability, provided by long-chain insulating ligands, and efficient charge transport, which requires shorter, conductive pathways. Ligand engineering strategies are pivotal in overcoming this bottleneck, directly influencing device performance in photovoltaics and LEDs.

Short-Chain Ligands and Conjugated Molecules

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Engineering on Charge Mobility and Device Performance

| Ligand Strategy | Material System | Key Effect on Mobility/Conductivity | Resulting Device Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain MPA/FAI exchange [14] | FAPbI₃ PQDs | Reduces inter-dot spacing, improves thin-film conductivity | 28% improvement in solar cell power conversion efficiency (PCE) |

| Conjugated PPABr ligands [15] | CsPbBr₃ PQDs | Enhances carrier mobility via π-π stacking and electron delocalization | LED External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) of 18.67% (up to 23.88% with light extraction) |

| Short-chain ThPABr ligand [15] | CsPbBr₃ PQDs (Control) | Provides a baseline for carrier transport | Serves as a reference for conjugated ligand improvements |

Replacing long-chain insulating ligands like oleylamine (OAm) and oleic acid (OA) with shorter alternatives is a common approach. A sequential solid-state multiligand exchange process for FAPbI₃ PQDs, replacing octylamine (OctAm) and OA with a hybrid of 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI), demonstrated a significant enhancement in photovoltaic device performance. This process removed ~85% of the original long-chain ligands, which reduced inter-dot spacing and defects, thereby boosting the current density and achieving a 28% improvement in power conversion efficiency [14].

Beyond simple chain length reduction, the use of conjugated ligands presents a more advanced strategy. Short-chain conjugated ligands based on 3-phenyl-2-propen-1-amine bromide (PPABr) leverage their π-π stacking capability and delocalized electron clouds to create efficient pathways for charge transport between QDs. The electronic properties of these ligands can be finely tuned with substituents; for instance, electron-donating groups (e.g., -CH₃) enhance hole transport, while electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -F) can improve electron transport. This modulation addresses carrier transport imbalance in devices, leading to a dramatic increase in the external quantum efficiency of light-emitting diodes [15].

Experimental Protocol: Sequential Solid-State Ligand Exchange

The following workflow, detailed for FAPbI₃ PQDs, outlines a robust method for enhancing thin-film conductivity [14]:

Title: Solid-State Ligand Exchange Workflow

Key Steps:

- Synthesis: FAPbI₃ colloidal QDs are synthesized via a modified ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP) method using PbI₂ and FAI precursors in acetonitrile, with OctAm and OA as initial capping ligands.

- Liquid Purification: Methyl acetate (MeOAc) is added to the colloidal solution in varying volumes (e.g., 1, 3, 5 mL). The solution is centrifuged, and the supernatant containing excess ligands and precursors is discarded.

- Solid Purification: The remaining sediment is redispersed in chloroform and centrifuged at a lower speed to remove large, agglomerated particles, yielding purified PQDs.

- Ligand Exchange: A solution of 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) and formamidinium iodide (FAI) in MeOAc is used to treat the spin-coated PQD films, replacing the remaining long-chain ligands.

- Validation: Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H NMR) spectroscopy is used to quantitatively confirm the removal of original ligands and the successful passivation with MPA and FAI.

Ligands as a Tool for Controlled Doping and Lattice Engineering

Ligands play a surprisingly active role in facilitating the incorporation of dopant ions into the PQD lattice and in driving structural transformations that directly affect electronic energy transfer processes.

Enhancing Nd³⁺ Doping Efficiency

In the pursuit of pure blue-emitting PQDs, neodymium (Nd³⁺) doping of CsPb(Cl/Br)₃ QDs is an effective strategy. However, the presence of surface halide and cesium vacancies often limits doping efficiency and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY). A ligand exchange process using 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS) was found to effectively repair these surface vacancies. This passivation step enhances the subsequent incorporation of Nd³⁺ into the perovskite lattice, leading to a dramatic increase in PLQY, achieving up to 94% at 466 nm for blue emission. The APTMS ligand not only improves optical efficiency but also contributes to greater photostability [16].

Driving Multiphase Formation for White Emission

Ligands can also be utilized to engineer the perovskite lattice dimensionality to create single-emitter white-light quantum dots. A two-step process involving Mn²⁺ doping followed by ligand exchange with short alkylammonium ligands like isopropylammonium bromide (IPABr) can induce a controlled transformation of the crystal structure.

Table 2: Ligands in Doping and Lattice Engineering

| Ligand Function | Ligand Example | Material System | Impact on Electronic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doping Enhancement [16] | APTMS (silane) | Nd-CsPb(Cl/Br)₃ PQDs | Repairs surface vacancies, enables high Nd³⁺ doping, boosts blue PLQY to 94% |

| Lattice Dimensionality Control [17] | IPABr (alkylammonium) | Mn-CsPb(Cl/Br)₃ PQDs | Drives formation of 0D-3D composite phases, tuning exciton energy transfer to Mn²⁺ for white light |

| Defect Passivation [10] | TOPO, L-PHE | CsPbI₃ PQDs | Coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺, suppresses non-radiative recombination, enhances PL intensity and stability |

This ligand exchange thermodynamically tunes the perovskite's emission profile. The strong interaction between short alkylammonium ligands and the perovskite surface can drive the formation of a mixed-dimensional composite, such as a 0D-3D structure. This transformation is crucial because it modifies the charge carriers' localization and the strength of exciton-phonon coupling within the lattice. These changes directly influence the efficiency of energy transfer from the perovskite excited state to the Mn²⁺ dopant ions, enabling the calibration of both excitonic and Mn²⁺ d-d emission to achieve a balanced white light profile [17].

The diagram below illustrates the mechanism of ligand-enhanced doping.

Title: Ligand-Enhanced Doping Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Ligand Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ligand Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Ligand Engineering | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short-chain bidentate ligand (thiol & carboxylate); improves charge transport and influences excited-state surface charge [14] [13]. | Photovoltaic devices for solid-state ligand exchange [14]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Simultaneously acts as A-site cation source and short ligand; helps maintain perovskite structure during exchange [14]. | Hybrid MPA/FAI passivation for FAPbI₃ PQDs [14]. |

| Conjugated Amines (e.g., PPABr) | Short-chain ligands with π-conjugated backbone; enhance inter-dot carrier mobility via π-π stacking [15]. | High-efficiency perovskite QLEDs [15]. |

| Alkylammonium Salts (e.g., IPABr) | Drive halide exchange and lattice dimensionality transformation; tune energy transfer to dopants [17]. | Fabrication of white-light single-emitter PQDs [17]. |

| Silane Molecules (e.g., APTMS) | Strongly binds to surface vacancies; enhances doping efficiency and photostability [16]. | Repairing Cs/halide vacancies in blue-emitting Nd-doped PQDs [16]. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Passivates undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on the PQD surface; reduces non-radiative recombination [10]. | Improving PLQY and stability of CsPbI₃ PQDs [10]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) | Multi-component ligand system forming a hydrogen-bonding network; enhances passivation and PL intensity [18]. | Synthesizing high-luminance PQDs for bright LEDs [18]. |

The strategic selection and application of surface ligands is a cornerstone of modern perovskite quantum dot research, offering precise control over the fundamental electronic properties that dictate device performance. As evidenced by recent studies, moving beyond traditional long-chain ligands to sophisticated short-chain, conjugated, and multi-functional ligands directly enhances charge carrier mobility by reducing inter-dot barriers and creating efficient conduction pathways. Furthermore, ligands are indispensable tools for enabling high-efficiency doping and band gap engineering through defect passivation and controlled lattice manipulation. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit outlined in this whitepaper provide a foundation for researchers to continue advancing the field, ultimately driving the development of more efficient, stable, and high-performance optoelectronic devices.

The surface area-to-volume ratio (SA:V) is a fundamental principle that distinguishes nanomaterials from their bulk counterparts. As material dimensions shrink to the nanoscale (1-100 nm), the surface area increases exponentially relative to volume [19]. For spherical perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), this relationship is defined mathematically as SA:V = 6/r, where r is the particle radius [19]. This geometric reality means that a dramatically larger fraction of atoms in PQDs reside at the surface, making these surface atoms dominant in determining the material's properties, stability, and functionality [20] [19].

This whitepaper examines how the exceptionally high SA:V ratio of PQDs necessitates careful surface ligand management to control optoelectronic properties, stabilize the ionic crystal structure, and enable advanced applications in sensing, photovoltaics, and biomedicine. We explore the fundamental ligand-PQD interactions, present quantitative data on ligand effects, and provide detailed methodologies for implementing ligand engineering strategies in research settings.

The Geometric Imperative: Surface Area to Volume Ratio in PQDs

The high SA:V ratio of PQDs creates both extraordinary opportunities and significant challenges. With particle sizes typically ranging from 5-20 nm, PQDs exhibit quantum confinement effects that enable size-tunable bandgaps and intense, narrow photoluminescence with quantum yields reaching 50-90% [21] [22]. However, this same characteristic creates a high energy, reactive surface where undercoordinated ions are susceptible to environmental degradation [22].

Table 1: Impact of Decreasing PQD Size on Surface Area to Volume Ratio

| Particle Radius (nm) | Surface Area (SA) | Volume (V) | SA:V Ratio | Implications for Surface Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1200 nm² | 4000 nm³ | 0.3 | Moderate surface dominance |

| 5 | 600 nm² | 500 nm³ | 1.2 | High surface reactivity |

| 2 | 240 nm² | 32 nm³ | 7.5 | Extreme surface dominance |

The relationship illustrated in Table 1 demonstrates why surface management becomes progressively more critical as PQD dimensions decrease. The large surface area provides numerous active sites for chemical reactions and functionalization, but simultaneously makes the material inherently unstable without proper passivation [19]. This geometric imperative establishes why ligand chemistry is not merely a synthetic consideration but a fundamental determinant of PQD viability.

Ligand Functions: Beyond Simple Stabilization

Surface ligands perform multiple critical functions that address the challenges posed by high SA:V ratios:

Structural and Electronic Stabilization

Ligands passivate undercoordinated surface atoms, particularly Pb²⁺ ions, preventing structural degradation and non-radiative recombination [11] [23]. Short-chain dicarboxylic acids like succinic acid (SA) demonstrate stronger binding to perovskite surfaces compared to conventional oleic acid, significantly improving fluorescence and stability [11]. Multidentate ligands provide enhanced stabilization through the chelate effect, where multiple binding points create more durable surface attachment [11].

Charge Transport Modulation

The insulating nature of long-chain hydrocarbon ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) creates barriers to inter-dot charge transport [22] [20]. Ligand engineering strategies replace these insulating ligands with shorter organic or inorganic alternatives, reducing interparticle distance from >2nm to <1nm and dramatically improving conductivity in PQD films [20] [1].

Application-Specific Functionalization

Ligands enable PQD integration into diverse applications. For biological sensing, ligands like N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) create ester groups that facilitate bioconjugation to proteins such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) [11]. In photovoltaic devices, conductive ligands such as formamidinium iodide and guanidinium thiocyanate enhance dot-to-dot electronic coupling while passivating surface defects [22].

Quantitative Evidence: Ligand Impact on PQD Properties

Research demonstrates measurable improvements in PQD performance through strategic ligand engineering:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of PQDs with Different Surface Ligands

| Ligand Type | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Stability Improvement | Key Findings | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Succinic Acid (SA) | Significant improvement over OA-capped QDs [11] | Enhanced water stability [11] | Stronger binding to perovskite surface; better electronic coupling [11] | Aqueous bio-sensing [11] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | 18% increase in PL intensity [23] | Not specified | Effective passivation of undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [23] | Optoelectronic devices [23] |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | 3% increase in PL intensity [23] | >70% initial PL intensity after 20 days UV exposure [23] | Superior photostability [23] | Long-term optical applications [23] |

| Alkaline-Treated Short Ligands | Not specified | Improved storage and operational stability [1] | Fewer trap-states, minimal agglomeration [1] | Photovoltaics (18.3% certified efficiency) [1] |

The data in Table 2 confirms that ligand selection directly influences key PQD performance metrics. The enhancement mechanisms vary from improved electronic coupling to defect passivation, with different ligands offering distinct advantages for specific application contexts.

Ligand Binding Dynamics and Classification

Understanding ligand-PQD interactions requires examining both binding mechanisms and ligand categorization:

Binding Coordination Chemistry

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies of PbS QDs reveal complex ligand binding beyond simple two-state (bound/free) models [24]. Three distinct ligand states exist: strongly bound oleate (OA) on Pb-rich (111) facets (X-type binding), weakly coordinated oleic acid (OAH) on (100) facets through acidic headgroups (L-type binding), and free ligands in solution [24]. This dynamic equilibrium influences exchange processes and surface coverage, which typically reaches 3.9 ligands/nm² [24].

Ligand Classification Framework

- X-type ligands: Anionic ligands (carboxylates, thiolates) that compensate for excess cationic charge by donating one electron to surface metal cations [24]

- L-type ligands: Neutral two-electron donors (amines, phosphines, carboxylic acids) that coordinate without affecting QD charge [24]

- Z-type ligands: Neutral two-electron acceptors that coordinate to surface chalcogen anions, typically classified as metal complexes [24]

The following diagram illustrates the multifaceted roles that ligands play in managing the high SA:V ratio in PQDs:

Experimental Protocols: Ligand Engineering Methodologies

Objective: Render CsPbBr₃ PQDs water-compatible for biomolecule sensing via ligand exchange.

Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ PQDs capped with oleic acid/oleylamine

- Dicarboxylic acid ligands: succinic acid (SA), folic acid (FA), EDTA, glutamic acid (GA)

- N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Toluene, ethyl acetate, double-distilled water

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA) as model protein

Procedure:

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ PQDs using established protocols with OA/OLA ligands

- Precipitate PQDs from toluene using ethyl acetate as antisolvent

- Redisperse purified PQDs in toluene containing dicarboxylic acid ligands (SA, FA, EDTA, or GA)

- Stir mixture for 4-6 hours at room temperature to facilitate ligand exchange

- Precipitate ligand-exchanged PQDs, remove supernatant with released OA ligands

- For bioconjugation: React SA-treated PQDs with NHS in aqueous medium to form NHS ester

- Add BSA protein to NHS-activated PQDs for bioconjugation via amide linkage

Characterization:

- UV-Vis and PL spectroscopy confirm retention of optical properties

- FTIR spectroscopy validates ligand exchange

- TEM analysis verifies crystal structure preservation

- Detection limit quantification for BSA sensing (achieved 51.47 nM)

Objective: Enhance conductive ligand capping on PQD surfaces for improved photovoltaics.

Materials:

- FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs with pristine OA/OAm ligands

- Methyl benzoate (MeBz) antisolvent

- Potassium hydroxide (KOH)

- 2-pentanol (2-PeOH) as solvent for cationic salts

Procedure:

- Prepare hybrid FA₀.₄₇Cs₀.₅₃PbI₃ PQDs via post-synthetic cation exchange

- Spin-coat PQD colloids into solid films

- Establish alkaline environment by adding KOH to MeBz antisolvent

- Rinse PQD solid films with alkaline MeBz solution under ambient humidity (~30% RH)

- Control alkalinity concentration to balance ligand exchange and structural integrity

- Perform subsequent A-site cationic ligand exchange using 2-PeOH as solvent

- Assemble PQD layers via layer-by-layer deposition with interlayer rinsing

Characterization:

- DFT calculations reveal ester hydrolysis becomes thermodynamically spontaneous

- Activation energy reduced approximately 9-fold versus conventional ester hydrolysis

- Achieved ~2× conventional amount of hydrolyzed conductive ligands

- Certified solar cell efficiency of 18.3% with minimal particle agglomeration

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for ligand exchange and its impact on PQD properties:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Ligands | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OLA) | Initial stabilization during synthesis; provide colloidal stability [11] [22] | Standard synthesis of pristine PQDs |

| Short-Chain Organic Ligands | Succinic acid, Glutamic acid, L-Phenylalanine | Replace long-chain ligands; reduce interparticle distance; improve charge transport [11] [23] | Aqueous compatibility; environmental stability |

| Conductive Ligands | Formamidinium iodide, Guanidinium thiocyanate, Acetate salts | Enhance inter-dot electronic coupling; passivate surface defects [22] [1] | Photovoltaic applications |

| Polymeric Ligands | PMMA, PS, PEG, Block copolymers | Form protective matrices; create tailored porosity [11] [20] | Environmental protection; sensor films |

| Inorganic Ligands | Halides (I⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻), Metal chalcogenide complexes | Create all-inorganic capping; superior conductivity [20] | Electronic devices |

| Bioconjugation Ligands | N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), Folic acid | Enable covalent bonding to biomolecules [11] | Biosensing; targeted delivery |

| Antisolvents | Methyl benzoate, Methyl acetate, Ethyl acetate | Facilitate ligand exchange during purification; induce precipitation [1] | Film processing; purification |

The high surface area-to-volume ratio of perovskite quantum dots represents both their greatest asset and most significant challenge. Through strategic ligand engineering, researchers can transform this potential vulnerability into a design advantage, precisely tuning PQD properties for specific applications. The methodologies and data presented herein demonstrate that comprehensive understanding and control of surface chemistry is indispensable for harnessing the full potential of PQDs in advanced technologies ranging from ultrasensitive biosensors to high-efficiency photovoltaics. As research advances, continued innovation in ligand design will undoubtedly unlock new frontiers in nanomaterial science and application.

Synthesis and Implementation: Ligand Engineering Strategies for Enhanced PQD Performance

The synthesis of perovskite nanocrystals (PNCs) has emerged as a critical research domain, with Hot-Injection (HI) and Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) standing as two predominant methodologies. Within the broader context of surface ligand research, these synthesis strategies represent more than mere procedural alternatives; they constitute fundamentally different approaches to manipulating surface chemistry that directly dictate the final electronic properties of the quantum-confined systems. Surface ligands serve as dynamic interfaces that passivate undercoordinated surface atoms, suppress non-radiative recombination, and ultimately determine the optoelectronic fate of the nanocrystals [25] [10]. The choice between HI and LARP protocols intrinsically determines the ligand binding dynamics, surface defect density, and colloidal stability, thereby positioning synthesis methodology as a primary variable in the pursuit of tailored PNC electronic characteristics. This technical analysis provides a comprehensive comparison of these core methods, focusing specifically on their mechanistic implications for surface chemistry and the resulting functional properties of CsPbBr3 and CsPbI3 PNCs, with direct relevance to optoelectronic applications including photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, and advanced biosensors [26] [27].

Methodological Fundamentals and Mechanisms

Hot-Injection (HI) Synthesis

The hot-injection method is a heat-driven precipitation technique conducted at elevated temperatures in non-aqueous, organic solvents. This approach involves the rapid injection of precursor compounds into a high-temperature reaction flask containing coordinating solvents and ligands, triggering instantaneous nucleation and subsequent controlled growth of nanocrystals [25] [28]. The synthesis of CsPbBr3 or CsPbI3 PNCs via HI typically employs a reaction medium of 1-octadecene with oleylamine and oleic acid as primary surface ligands, with temperatures precisely controlled between 140–180°C [10]. The high-temperature environment provides sufficient thermal energy to overcome kinetic barriers, facilitating the formation of highly crystalline structures with excellent optical properties. The protocol necessitates an oxygen-free environment, typically achieved through Schlenk line techniques, and offers exceptional control over nanocrystal size through manipulation of temperature, reaction duration, and ligand concentration [28].

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP)

In contrast, Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation represents a room-temperature strategy where perovskite precursors dissolved in a polar solvent (such as dimethylformamide or dimethyl sulfoxide) are rapidly introduced into a non-polar poor solvent (typically toluene) under vigorous stirring [29]. This sudden change in solvent environment dramatically reduces solute solubility, triggering supersaturation and subsequent nanocrystal formation. The ligands present in the system—typically long-chain alkyl amines and acids—immediately coordinate with nascent crystal surfaces, controlling growth and preventing aggregation [29]. This method's effectiveness hinges on the precise balance between precursor concentration, solvent polarity, and ligand chemistry, which collectively determine nucleation kinetics and final nanocrystal characteristics. As a bench-top technique requiring no specialized inert equipment, LARP offers remarkable accessibility and scalability while producing PNCs with commendable optical properties, though with distinct surface characteristics compared to HI-synthesized counterparts [25] [29].

Comparative Analysis: Structural and Optical Properties

Table 1: Direct comparison of key characteristics between Hot-Injection and LARP synthesis methods

| Parameter | Hot-Injection (HI) | Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Temperature | 140-180°C [10] | Room temperature [29] |

| Reaction Atmosphere | Inert (oxygen-free) required [28] | Ambient conditions possible [29] |

| Typical Ligands | Oleylamine, Oleic Acid, TOPO, TOP [10] | Short-chain and long-chain amines/acids [29] |

| PLQY Range | Up to 95%+ (with optimal passivation) [10] | Generally high but method-dependent [29] |

| Crystallinity | Excellent [25] | Good to very good [25] [29] |

| Size Distribution | Narrow (with optimization) [28] | Broader, requires careful parameter control [29] |

| Scalability | Moderate (batch process) [28] | High (potentially continuous) [29] |

| Defect Density | Lower deep traps [25] | Highly ligand-dependent [29] |

| Blinking Behavior | Power-law statistics with "blinking-down" [25] | Distinct patterns with "blinking-up" [25] |

Table 2: Impact of synthesis method on CsPbBr₃ PNC characteristics based on experimental data

| Property | Hot-Injection Derived PNCs | LARP-Derived PNCs |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Quenchers | Distinct energy levels [25] | Different trap state distribution [25] |

| Non-Radiative Recombination | Controlled by high-temperature surface annealing [25] | Influenced by ligand diffusion kinetics [29] |

| Phase Stability | High (CsPbI₃ retained at 170°C) [10] | Moderate (room-temperature phase challenges) [29] |

| Ligand Binding Affinity | Strong, thermodynamically favored [25] | Weaker, kinetically controlled [29] |

| Application Performance | High-efficiency LEDs and solar cells [10] | Promising for sensors and large-area films [27] |

The structural and optical differences between HI and LARP-synthesized PNCs directly originate from their distinct formation mechanisms. Hot-injection produces PNCs with superior crystallinity and narrower size distributions due to high-temperature growth and Oswald ripening processes [25]. These materials typically exhibit higher photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) and enhanced phase stability, particularly for the metastable cubic phase of CsPbI₃, which can be retained at optimal synthesis temperatures of 170°C [10]. The elevated temperatures facilitate stronger ligand binding and more effective surface passivation, as evidenced by PLQY enhancements of 16% and 18% with TOP and TOPO ligands, respectively [10].

LARP-synthesized PNCs display different photophysical behaviors, including distinct blinking statistics with observed "blinking-up" events attributed to varying surface quencher energy levels created during room-temperature formation [25]. The crystallinity, while good, is generally inferior to HI-derived crystals, and size distributions tend to be broader without careful parameter optimization [29]. The ligand binding is kinetically controlled and highly dependent on diffusion rates during the reprecipitation process, resulting in different surface trap distributions and non-radiative recombination pathways [29].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Hot-Injection Synthesis for CsPbI₃ PQDs

Table 3: Key reagents for Hot-Injection synthesis of CsPbI₃ PQDs

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentration/Purity |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cs⁺ precursor | 99% purity [10] |

| Lead(II) Iodide (PbI₂) | Pb²⁺ and I⁻ source | 99% purity [10] |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating solvent | 90% purity [10] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Ligand and reaction medium | 98% purity [10] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Ligand and reaction medium | 80% purity [10] |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphorus ligand for passivation | 99% purity [10] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine oxide ligand for passivation | 99% purity [10] |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Amino acid ligand | 98% purity [10] |

Step 1: Precursor Preparation

- Cs-oleate precursor: Load 0.2 mmol Cs₂CO₃ (0.065 g) into a 50 mL flask with 1.6 mL OA and 8 mL ODE. Dry under vacuum for 1 hour at 120°C, then heat under N₂ atmosphere to 150°C until complete dissolution [10].

- Pb-I precursor: Combine 0.2 mmol PbI₂ (0.092 g) with 10 mL ODE in a 25 mL flask. Dry under vacuum at 120°C for 30 minutes, then add 1 mL OA and 1 mL OAm under nitrogen atmosphere [10].

Step 2: Injection and Reaction

- Heat the Pb-I mixture to the target synthesis temperature (140-180°C) under nitrogen with vigorous stirring [10].

- Rapidly inject 1.5 mL of the preheated Cs-oleate precursor into the reaction vessel [10].

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 5-15 seconds until the solution develops a deep red color, indicating CsPbI₃ PQD formation [10].

Step 3: Purification and Ligand Modification

- Immediately cool the reaction mixture in an ice-water bath to terminate growth [10].

- Precipitate PQDs by adding excess ethyl acetate (approximately 10 mL) followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes [10].

- For ligand exchange, redisperse the pellet in 5 mL anhydrous toluene and add specific ligands (TOP, TOPO, or L-PHE) at controlled molar ratios relative to Pb²⁺ content (typically 1:1 to 1:5 ligand:Pb ratio) [10].

- Incubate the ligand-modified PQDs for 1-2 hours with stirring to ensure complete surface coordination before a final purification step [10].

Detailed LARP Protocol for CsPbBr₃ PNCs

Step 1: Precursor Solution Preparation

- Prepare the polar solution: Dissolve 0.1 mmol CsBr (0.021 g) and 0.1 mmol PbBr₂ (0.037 g) in 1 mL dimethylformamide (DMF) [29].

- Add specific ligands to the precursor solution: For acid-base pair ligands, use equimolar amounts of oleylamine and oleic acid (typically 50 μL each per mL DMF) [29].

Step 2: Reprecipitation and Nanocrystal Formation

- Place 5 mL of the poor solvent (toluene or chloroform) in a vial under vigorous stirring (800-1000 rpm) [29].

- Rapidly inject the precursor solution (100-200 μL) into the toluene antisolvent [29].

- Immediate color development (green luminescence for CsPbBr₃) indicates PNC formation within seconds [29].

Step 3: Purification and Optimization

- Isolate PNCs by centrifugation at 6000-8000 rpm for 5 minutes to remove aggregates and unreacted precursors [29].

- Redisperse the purified PNCs in toluene or hexane for further characterization [29].

- Critical parameters: High-throughput robotic screening reveals that ligand diffusion rates during reprecipitation crucially determine final PNC functionalities. Long-chain ligands (e.g., oleylamine) produce more homogeneous and stable PNCs compared to short-chain alternatives [29].

Synthesis Workflow and Decision Pathways

Surface Ligand Dynamics and Electronic Implications

The fundamental distinction between HI and LARP synthesis manifests most profoundly in their respective surface ligand dynamics and the resulting electronic properties. In hot-injection, the elevated temperature environment facilitates strong, thermodynamically favored ligand binding with effective passivation of undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, significantly suppressing non-radiative recombination centers [25] [10]. This produces PNCs with lower defect densities and enhanced photoluminescence quantum yields, as demonstrated by the 18% PL enhancement observed with TOPO passivation in CsPbI₃ PQDs [10]. The high-temperature annealing promotes more ordered ligand packing and superior surface coverage, critical for charge transport in optoelectronic devices.

In LARP synthesis, the room-temperature ligand coordination occurs through kinetically controlled processes where ligand diffusion rates crucially determine final surface functionality [29]. High-throughput robotic studies reveal that long-chain ligands (e.g., oleylamine) provide homogeneous and stable PNCs, while short-chain ligands generally fail to produce functional nanocrystals with desired characteristics [29]. The different surface quencher configurations in LARP-derived PNCs lead to distinct blinking behaviors, including "blinking-up" phenomena not typically observed in HI-synthesized counterparts [25]. Monte Carlo simulations corroborate that these synthetic differences create surface traps with varying energy levels, directly influencing charge carrier dynamics and recombination pathways [25].

Application-Specific Performance and Future Outlook

The choice between HI and LARP synthesis methods carries significant implications for application performance across various technological domains. For high-performance optoelectronics including light-emitting diodes and photovoltaic cells, hot-injection synthesized PNCs generally deliver superior performance metrics due to their excellent crystallinity, high PLQY, and outstanding charge transport characteristics [10]. The enhanced phase stability of HI-derived CsPbI₃ PQDs is particularly valuable for solar cell applications where thermal stress is inevitable during device operation [10].

For sensing and detection platforms, including biosensors for pathogen detection and fluorescent probes for food safety monitoring, LARP-synthesized PNCs offer compelling advantages [26] [27]. Their room-temperature processing compatibility facilitates integration with biological recognition elements, while their sufficient quantum yields enable sensitive detection mechanisms based on FRET, PET, and inner filter effects [27]. The scalability of LARP further supports cost-effective production for disposable sensor platforms, with demonstrated capabilities in detecting pesticides and mycotoxins at sub-ng/mL concentrations in complex food matrices [27].

Future developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine the advantages of both methods, potentially through moderate-temperature synthesis or post-synthetic ligand engineering. Machine-learning-assisted optimization, as demonstrated in high-throughput LARP studies, represents a promising direction for rapidly identifying optimal synthesis parameters for specific applications [29]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on lead-free alternatives (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs) for biomedical and environmental applications will require adaptation of both HI and LARP protocols to accommodate different precursor chemistries and coordination requirements [26].

Surface ligands play a fundamental role in determining the electronic properties of quantum dot (QD) solids, which critically impact charge transport, doping density, and overall device performance in photovoltaic and other optoelectronic applications [30]. The diligent utilization of surface chemistry enables the precise engineering of material characteristics, essentially paving the way for advanced functionality. Among various ligand strategies, binary ligand systems comprising carboxylic acids and amines represent a particularly powerful approach for achieving superior passivation and electronic coupling [30]. These systems leverage synergistic effects between the two complementary ligand types, allowing for enhanced mobility-lifetime products in QD solids compared to traditional single-ligand passivation strategies [30]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms, methodologies, and applications of carboxylic acid/amine binary ligand systems within the broader context of tailoring PQD electronic properties.

The Role of Surface Ligands in Quantum Dot Electronics

Fundamental Functions of Ligands

Surface ligands are molecular entities bound to the surface atoms of quantum dots. Their primary functions extend beyond mere colloidal stability to actively defining the electronic landscape of the resulting solid materials. Key roles include:

- Surface Passivation: Coordinative binding to under-coordinated surface atoms reduces trap states and prevents non-radiative recombination [30].

- Inter-Dot Spacing: The physical size and conformation of ligands determine the distance between adjacent QDs, critically influencing charge carrier tunneling and mobility [30].

- Dielectric Environment: The polarizability and functional groups of ligands modify the dielectric constant surrounding the QDs, affecting Coulombic interactions and charge separation efficiency [30].

- Doping Density: Ligands can introduce charge carriers into the QD solid through remote molecular doping mechanisms, enabling controlled tuning of Fermi levels [30].

Electronic Property Modulation

The changes in size, shape, and functional groups of small-chain organic ligands enable researchers to modulate key electronic properties of lead sulfide QD solids [30]. This modulation directly impacts photovoltaic figure of merits, including power conversion efficiency, open-circuit voltage, and short-circuit current. Atomic ligand strategies utilizing monovalent halide anions have demonstrated particularly enhanced electronic transport and effective surface defect passivation in PbS CQD films [30].

Table 1: Key Electronic Properties Modulated by Surface Ligands in QD Solids

| Property | Impact on Device Performance | Ligand Influence Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Charge transport efficiency; Fill factor | Inter-dot distance; Electronic coupling |