Surface Engineering Strategies for High-Performance Perovskite Quantum Dot LEDs: A Comparative Review

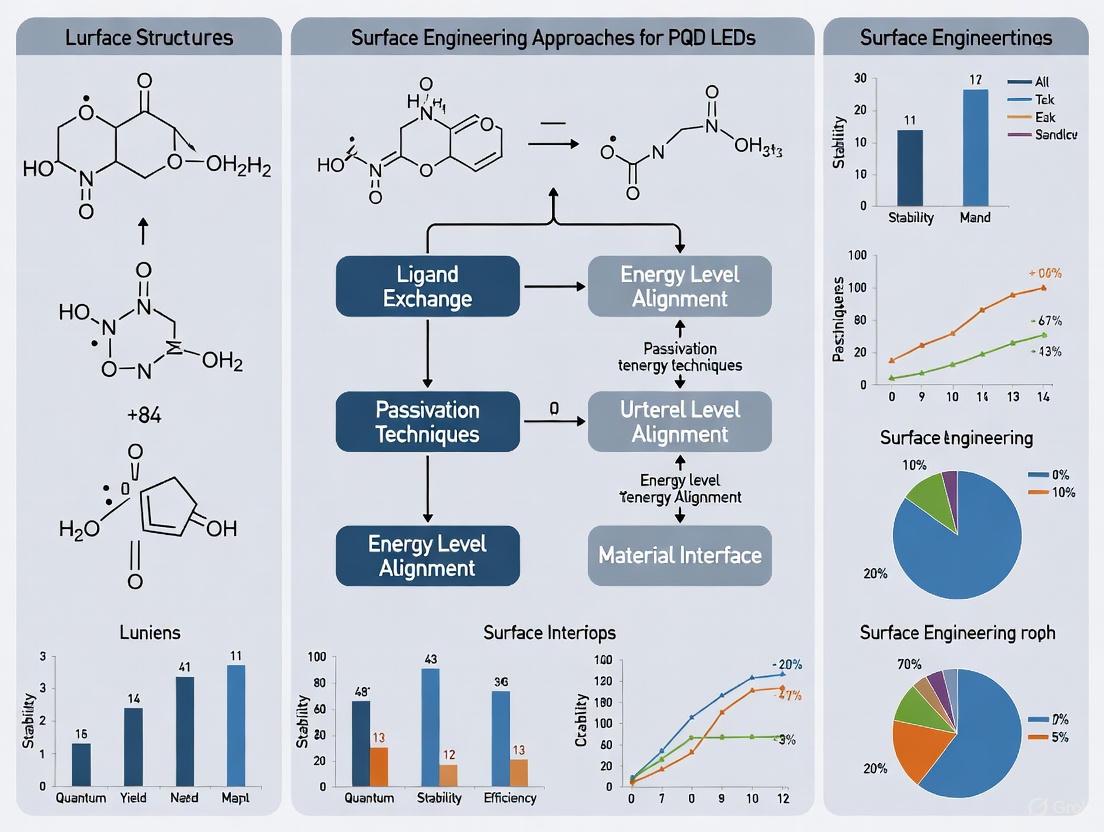

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of surface engineering approaches for enhancing the performance and stability of perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (PQD-LEDs).

Surface Engineering Strategies for High-Performance Perovskite Quantum Dot LEDs: A Comparative Review

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of surface engineering approaches for enhancing the performance and stability of perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (PQD-LEDs). Targeting researchers and development professionals, it systematically explores fundamental principles, advanced methodologies including ligand exchange and compositional engineering, and troubleshooting strategies for common challenges like environmental instability and lead toxicity. The review validates techniques through performance metrics and comparative analysis, synthesizing key takeaways to guide future innovations in display technologies and biomedical applications. By integrating the latest research advances, this work establishes a framework for rational surface design to unlock the full potential of PQDs in next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Fundamentals of PQD Surface Physics and Interface Engineering

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) are zero-dimensional nanocrystals of metal halide perovskites that exhibit distinct chemical, physical, electrical, and optical properties compared to their bulk counterparts [1]. Their unique crystal structure and pronounced quantum confinement effects make them highly promising materials for a broad range of optoelectronic applications, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar cells, lasers, photodetectors, and quantum technologies [1] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the fundamental structural and optical properties of PQDs, with a specific focus on how surface engineering approaches modulate these properties to enhance the performance of PQD-based LEDs.

Fundamental Structure and Quantum Confinement in PQDs

Crystal Structure of Perovskite Quantum Dots

The canonical crystal structure for all-inorganic PQDs is CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I), which derives from the ABX3 perovskite configuration. In this structure, cesium (Cs+) ions occupy the A-site, lead (Pb2+) ions the B-site, and halide ions (Cl-, Br-, I-) the X-site [3]. This arrangement forms a three-dimensional network of corner-sharing [PbX6]4- octahedra, with Cs+ ions situated in the cuboctahedral cavities. The integrity of this ionic crystal lattice is crucial for the material's optoelectronic properties.

The optical bandgap, and thus the emission color, of PQDs can be precisely tuned through halide composition. For instance, in mixed-halide systems like CsPbBr3−xIx, the bandgap can be engineered to emit across the visible spectrum [4]. Furthermore, the tolerance factor and octahedral factor are key geometric parameters that determine the stability of the perovskite structure, which can be optimized through ion doping at various lattice sites [3].

Quantum Confinement Effects

When the physical dimensions of a perovskite crystal are reduced to a scale comparable to or smaller than the Bohr exciton diameter (typically 3-10 nm for lead halide perovskites), quantum confinement effects become significant [5]. In this regime, the continuous energy bands of the bulk material transform into discrete, atom-like energy levels, dramatically altering the electronic and optical properties.

- Size-Dependent Bandgap: The bandgap of PQDs increases as their size decreases, leading to a blue shift in both absorption and photoluminescence (PL) emission spectra [5]. This effect is powerfully demonstrated not only in PQDs but also in other semiconducting systems, such as in-plane

MoSe2quantum dots embedded in aWSe2monolayer, where a clear exciton blue shift of 12-40 meV was observed for dots with widths of ~15-60 nm [6]. - Enhanced Optical Properties: Quantum-confined PQDs exhibit high color purity, characterized by narrow full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) emission linewidths (often <20 nm) [7], high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) approaching 100% [2] [8], and a high radiative recombination rate due to the spatial overlap of electron and hole wavefunctions [5].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between crystal structure, quantum confinement, and the resulting optical properties in PQDs.

Comparative Analysis of Surface Engineering Approaches for PQD LEDs

The surface of PQDs is a critical determinant of their structural stability and optical performance. Unpassivated surfaces with dangling bonds act as defect sites that trap charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination and reduced luminescence efficiency [2]. Surface engineering aims to passivate these defects and protect the ionic crystal lattice from environmental degradation, which is particularly crucial for the operational stability of PQD-LEDs. The table below compares the major surface engineering strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Engineering Approaches for PQD LEDs

| Engineering Approach | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Structural Properties | Impact on Optical Properties | Reported LED Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Exchange/Modification [2] [3] | Replacing long, insulating ligands (e.g., OA, OAm) with shorter or bifunctional ones (e.g., PEABr, DA). | Reduces inter-dot distance, improves charge transport. Stabilizes surface ions. | Reduces trap-assisted recombination; increases PLQY and charge injection efficiency. | High-efficiency pure-red CsPbI3 QLEDs; stable pure-blue LEDs via acid etching-driven ligand exchange [2]. |

| Ion Doping [4] [3] | Incorporation of foreign ions (e.g., Mn2+, Na+, Rb+, Cu+) into the PQD lattice. | Enhances phase stability by optimizing tolerance factor. Passivates surface defects. | Can enhance PL intensity and thermal/air stability. Modifies emission color. | Doping with alkaline metal oxides (e.g., Na2O) reported to enhance PL intensity by up to 200% and PLQY by 29% [4]. |

| Matrix Encapsulation [4] [3] | Embedding PQDs within a protective matrix (e.g., PMMA, oxide glasses, MOFs). | Physically shields PQDs from environmental stressors (H2O, O2, heat). | Maintains high PLQY over time; significantly improves operational longevity. | PMMA encapsulation (2:1 ratio) increased PLQY of CsPbBr3 QDs from 60.2% to 90.1% [3]. Borosilicate glass matrices enable high-stability PQDs for lighting [4]. |

| Bilateral/Composite Passivation [5] [2] | Forming composite structures (e.g., with graphene) or bilateral interfacial layers. | Provides a stable substrate and charge transfer pathways. Suppresses ion migration. | Enhances nonlinear optical properties and device stability. Improves EQE. | Bilateral passivation strategy promoted both efficiency and stability in LEDs [2]. CH3NH3PbBr3-G composites showed enhanced saturable absorption for optical switches [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Surface Engineering Methods

To provide a practical research toolkit, here are detailed methodologies for several key surface engineering techniques cited in the comparison table.

1. Ligand Exchange with PEABr (Post-Synthesis) [3]

- Synthesis of Original CsPbBr3 PQDs: Dissolve 0.2 mmol PbBr2 and 0.2 mmol CsBr in 5 mL DMF. Add 0.25 mL oleylamine (OAm) and 0.5 mL oleic acid (OA) and stir until clear. Inject 1 mL of this precursor solution into 10 mL of toluene under vigorous stirring (1200 rpm). The solution turns bright green immediately, indicating PQD formation.

- PEABr Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1.52 mg of PEABr powder and 50 μL of OA in 4 mL of ethyl acetate. Sonicate for 5 minutes to obtain a clear solution.

- Ligand Exchange: After the synthesis of the original PQDs, add the PEABr solution in molar ratios of 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% relative to the initial OAm amount. Mix thoroughly to allow the exchange of OAm with PEABr on the PQD surface.

2. Mn²⁺ Doping [3]

- Precursor Preparation: Co-dissolve PbBr2 (0.2 mmol), CsBr (0.2 mmol), and varying amounts of MnBr2·4H2O (9 mg, 12 mg, or 15 mg) in 5 mL of DMF. Add 0.25 mL OAm and 0.5 mL OA and stir until clear.

- PQD Synthesis: Follow the same injection and crystallization procedure as for the original CsPbBr3 PQDs. The Mn²⁺ ions are incorporated into the crystal lattice during the nucleation and growth process.

3. PMMA Encapsulation [3]

- PMMA Solution Preparation: Dissolve 50 mg of solid PMMA in 1 mL of toluene by heating and stirring in an 80 °C oil bath until fully dissolved. Allow the solution to cool.

- Encapsulation Process: After the synthesis of the CsPbBr3 PQD solution, add the PMMA solution in varying volume ratios (e.g., QD:PMMA = 1:2, 1:1, 2:1). Mix uniformly to encapsulate the individual PQDs within the transparent polymer matrix.

The workflow for synthesizing and optimizing PQDs for LED applications, integrating these key surface engineering steps, is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key materials and reagents essential for experimental work in PQD synthesis and surface engineering for LED applications.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Surface Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Typical Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Bromide (CsBr) | Cs+ (A-site) precursor for all-inorganic PQDs [3]. | Synthesis of CsPbBr3 QDs. |

| Lead Bromide (PbBr2) | Pb2+ (B-site) and halide precursor [3]. | Synthesis of CsPbBr3 QDs. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain surface ligands/capping agents [3]. | Stabilize nanocrystals during and after synthesis; prevent aggregation. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | High-polarity solvent for precursor salts [3]. | Dissolving PbBr2 and CsBr before injection into toluene. |

| Toluene | Low-polarity solvent [3]. | Non-solvent for triggering PQD nucleation and growth. |

| Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Short-chain, conductive surface ligand [3]. | Ligand exchange to replace OAm, improving charge transport in LED films. |

| Manganese Bromide (MnBr2) | Dopant source for B-site ion doping [3]. | Mn2+ doping to enhance stability and modify optical properties. |

| Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) | Transparent polymer for matrix encapsulation [3]. | Coating PQDs to shield them from moisture and oxygen, enhancing longevity. |

| Alkaline Metal Oxides (e.g., Na2O) | Glass network modifier and potential dopant [4]. | Added to borosilicate glass matrices to enhance crystallization and PL of CsPbBr3−xIx QDs. |

| Silver Oxide (Ag2O) | Nucleating agent in glass matrices [4]. | Promotes the crystallization of PQDs within an oxide glass host. |

The optoelectronic performance of perovskite quantum dot LEDs is intrinsically governed by their crystal structure and the quantum confinement effects that arise at the nanoscale. While these properties grant PQDs their exceptional luminescence and color tunability, they also introduce a vulnerability to surface defects and environmental degradation. The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that no single surface engineering approach is universally superior. Instead, the choice of strategy—be it ligand engineering for improved charge transport, ion doping for intrinsic lattice stability, or matrix encapsulation for extreme environmental shielding—must be aligned with the specific performance and stability requirements of the target LED application. The future of high-performance PQD-LEDs lies in the rational combination of these strategies, leveraging their synergistic effects to simultaneously achieve high efficiency, color purity, and operational longevity, thereby bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and commercial viability.

The surface chemistry of Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) represents a critical frontier in advancing optoelectronic technologies, particularly for light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Unlike bulk materials, PQDs possess an intrinsically high surface-to-volume ratio, making their optical and electronic properties profoundly dependent on surface conditions [9]. Surface ligands—organic or inorganic molecules bound to the nanocrystal surface—play a dual role: they passivate surface defects to enhance photoluminescence and govern charge transport in solid-state films [10] [11]. The interplay between ligands and surface states directly impacts key performance metrics in PQD-LEDs, including efficiency, stability, and color purity [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of surface engineering strategies, offering structured experimental data and protocols to inform research and development in PQD-based devices.

Ligand Engineering Strategies: A Comparative Analysis

Ligand engineering encompasses the selection and modification of molecules coordinated to the PQD surface. Different ligand classes impart distinct effects on the material's properties, as quantitatively compared below.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Surface Ligands on CsPbI3 PQDs

| Ligand Type | Key Functional Group | PL Enhancement | Photostability (After 20 days UV) | Primary Passivation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphine | 16% | Information Missing | Coordinates undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [13] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine Oxide | 18% | Information Missing | Coordinates undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [13] |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Amine/Carboxylate | 3% | >70% initial PL retained | Suppresses non-radiative recombination [13] |

Beyond small molecules, ionic ligands and mixed-ligand systems have emerged as powerful tools. For instance, a bilateral interfacial passivation strategy has been demonstrated to boost both efficiency and operational stability in PQD-LEDs [2]. Similarly, alkyl ammonium iodide-based ligand exchange has been employed to achieve high-efficiency in organic-cation perovskite quantum dot solar cells [2]. These strategies highlight a trend toward multi-functional ligand systems that simultaneously address defect passivation and charge transport.

Impact of Ligands on Electronic Structure

Surface ligands induce changes that extend beyond defect passivation, directly influencing the PQD's ground-state electronic structure. Experimental studies reveal that ligand exchange can alter the optical band gap, absorption coefficient at all wavelengths, and the ionization potential of colloidal QDs [9]. This occurs because the orbitals of the ligands and the inorganic core mix in each other's electric field, making the ligand-core adduct an indecomposable electronic entity. This description moves beyond simple electrostatic models and underscores the importance of treating the ligand and QD as an integrated system for rational design [9].

Advanced Characterization of Ligand-Surface Interactions

Understanding the dynamic interplay between ligands and the PQD surface requires advanced spectroscopic techniques. Mid-IR transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy has enabled the direct probing of ligand vibrational features in the excited states of nanocrystals, providing unprecedented insight into surface dynamics [14].

For example, studies on PbS QDs passivated with oleate ligands revealed a net weakening of Pb-O coordination in the excitonic excited state. This change is attributed to an enhanced electron density on the QD surface, which makes the ligand shell more dynamic and potentially more permeable to charge and energy transfer processes [14]. In contrast, when PbS QDs are passivated with 3-mercaptoproprionic acid (MPA)—which contains both thiol and carboxylate groups—the transient vibrational features indicate a different mechanism. The thiol groups localize hole density at the QD surface, leading to a uniform frequency shift of the carboxylate vibrational features due to changes in surface charge density [14]. These findings demonstrate that the excited-state surface chemistry is highly dependent on the specific ligand structure and its interaction with the nanocrystal.

Table 2: Summary of Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in PQD Surface Chemistry | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Surface passivator for undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions | CsPbI3 PQD synthesis for enhanced PLQY [13] |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Surface passivator for undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions | CsPbI3 PQD synthesis for high PL enhancement [13] |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Bifunctional ligand for defect suppression | Imparts superior photostability in CsPbI3 PQDs [13] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Common coordinating ligand / Surfactant | Standard in LARP and hot-injection synthesis methods [11] |

| Oleylamine (OlAm) | Common coordinating ligand / Surfactant | Standard in LARP and hot-injection synthesis methods [11] |

| 3-Mercaptoproprionic Acid (MPA) | Ligand with dual anchoring groups | Model system for studying hole localization at surfaces [14] |

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for studying PQD surface chemistry, covering synthesis, ligand engineering, and advanced characterization.

Machine Learning in Surface Chemistry Optimization

The complex relationship between synthesis parameters, surface chemistry, and final PQD properties presents a formidable challenge for traditional experimental approaches. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to navigate this multi-dimensional space. For instance, a study on CsPbCl3 PQDs demonstrated that ML models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Nearest Neighbour Distance (NND) can accurately predict output properties such as nanocrystal size, absorption, and photoluminescence peaks based on synthesis features as input [15].

The methodology involves creating a comprehensive database from peer-reviewed literature, including parameters such as injection temperature, precursor amounts and sources, ligand volumes (e.g., ODE, OA, OLA), and molar ratios (e.g., Cs-to-Pb, Cl-to-Pb) [15]. These inputs are then used to train various algorithms to predict target properties. This data-driven approach can significantly accelerate the optimization of surface ligand recipes, reducing the reliance on time-consuming and costly trial-and-error experimentation [15].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Ligand Modification of CsPbI3 PQDs

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the effect of surface ligand modification on the optical properties of CsPbI3 PQDs [13].

- Synthesis Method: Hot-injection method.

- Precursors: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99%), Lead(II) iodide (PbI₂, 99%).

- Ligands: Trioctylphosphine (TOP, 99%), Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, 99%), L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE, 98%).

- Reaction Medium: 1-octadecene (ODE) as the non-coordinating solvent.

- Optimized Parameters:

- Reaction Temperature: 170 °C (found optimal for highest PL intensity and narrowest FWHM).

- Hot-injection Volume: 1.5 mL.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve precursors in ODE with ligands.

- Rapidly inject the precursor mixture into the hot solvent.

- Maintain the reaction at the target temperature (e.g., 170 °C) for a controlled duration.

- Purify the resulting PQDs by centrifugation.

- Characterization: Analyze PL intensity, Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), and photostability under continuous UV exposure.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Surface Chemical States via Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the use of photoelectron spectroscopy to correlate surface chemical states with PL characteristics, a method employed in studies of cesium lead bromide NCs [11].

- Synthesis Methods: Employ parallel synthesis using LARP and URSOA methods with the same precursor composition to produce NCs with and without ligands.

- Ligand Removal: Purify NCs using a mixture of ethanol and toluene (1:1 v/v) with sonication to remove surface ligands.

- Surface Analysis:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) and Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES): Analyze the core-level orbitals to determine chemical states at the NC surface. Look for evidence of surface defect species such as Pb atoms with zero oxidation state (Pb⁰), unbonded Br atoms, and Br vacancies.

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Confirm the presence or absence of ligand binding.

- Correlation with Optical Properties:

- Measure photoluminescence (PL) decay dynamics (time-resolved PL).

- Directly correlate changes in surface chemical states (from XPS/HAXPES) with observed PL characteristics and decay lifetimes to understand the role of surface defects influenced by ligands.

Diagram 2: Logical relationships showing how intrinsic/extrinsic factors and surface components determine the final optoelectronic properties of PQDs.

The strategic engineering of surface ligands is paramount for harnessing the full potential of perovskite quantum dots in optoelectronic devices. Comparative analysis demonstrates that different ligand classes—from small molecules like TOP and L-Phenylalanine to complex mixed systems—impart distinct effects on PL enhancement, photostability, and charge transport. The emerging paradigm treats the ligand-PQD core as an indecomposable electronic entity, where surface chemistry directly dictates the ground-state and excited-state properties. Integrating advanced characterization like transient spectroscopy with data-driven machine learning models provides a robust framework for accelerating the development of high-performance, stable PQD-LEDs, pushing the boundaries of display and lighting technologies.

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high absorption coefficients, tunable bandgaps, and high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [2]. These characteristics make them particularly promising for applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), solar cells, and other advanced optoelectronic devices. However, the practical implementation and commercial viability of PQD-based technologies are significantly hampered by the presence of surface defects, primarily halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions [16] [17] [18]. These defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, deteriorating both the efficiency and operational stability of the resulting devices.

The "defect-tolerant" nature of metal halide perovskites is a double-edged sword. While many defects form shallow levels not detrimental to emission, halide vacancies and uncoordinated lead ions can create deep-level traps that facilitate non-radiative recombination and ion migration [16]. In mixed-halide systems, such as CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs developed for pure-red LEDs, halide vacancies significantly lower the activation energy for ion migration, leading to electric-field-driven phase segregation. This segregation manifests as undesirable emission broadening and spectral shifts, directly undermining color purity—a critical parameter for display applications [17]. Similarly, uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, often found on lead-rich surfaces, provide sites for exciton quenching and can initiate degradation pathways, reducing the PQDs' lifetime [17] [19]. Therefore, understanding and mitigating these specific defects through advanced surface engineering is a central focus in contemporary PQD research and development.

Defect Classification and Impact on PQD Performance

Origin and Classification of Defects

The soft ionic lattice of metal halide perovskites, combined with their typical low-temperature solution processing, makes them prone to the rapid formation of point defects during crystal growth [16]. These structural imperfections interrupt the perfect crystal periodicity and profoundly influence the material's electronic properties. The primary point defects in PQDs can be categorized as follows:

- Vacancies: Empty lattice sites where an atom is missing. For PQDs, iodide/bromide vacancies (Vᵢ/VBr) and lead vacancies (V_Pb) are common.

- Interstitials: Atoms that occupy positions outside the regular lattice sites.

- Anti-site substitutions: Atoms swapping their positions in the crystal lattice [16].

Among these, halide vacancies (Vᵢ/VBr) are notably prevalent due to their low formation energy. They are a major source of hole traps and serve as pathways for ion migration. Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions often arise from the absence of a passivating ligand or halide ion, leaving the Pb²⁺ ion under-saturated and creating a strong electron trap [17]. The formation energy of a defect determines its concentration in the lattice, and fortunately, many defects in MHPs have high formation energies for deep-level traps, resulting in a low non-radiative recombination rate—a property known as "defect tolerance" [16].

Performance-Limiting Mechanisms

The detrimental impact of halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions on PQD LEDs manifests through several physical mechanisms, as shown in the diagram below.

Non-Radiative Recombination: Both halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions create electronic states within the bandgap that capture photogenerated charge carriers (electrons and holes). Instead of recombining to emit a photon, the carriers lose their energy as heat through these trap states. This process directly lowers the external quantum efficiency (EQE) and photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of PQD LEDs [16] [17].

Ion Migration and Phase Segregation: Halide vacancies act as hopping sites for halide ions, especially under the influence of an electric field or light illumination. In mixed-halide PQDs (e.g., CsPb(Br/I)₃), this migration leads to the separation into iodine-rich and bromine-rich domains. The iodine-rich regions, with a narrower bandgap, become low-energy traps for charge carriers, causing the emission spectrum to red-shift and broaden over time. This phenomenon severely compromises the spectral stability and color purity of the LEDs, which is critical for display applications [17].

Reduced Charge Transport: Long-chain insulating ligands used in synthesis, such as oleic acid and oleylamine, are often partially removed during purification to improve electrical conductivity. However, aggressive ligand removal can expose uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, creating a high density of charge traps. This results in poor film conductivity, increased hysteresis, and significant open-circuit voltage (V_OC) losses in devices [19].

Comparative Analysis of Surface Engineering Strategies

A range of surface engineering strategies has been developed to passivate these defects. The table below provides a comparative overview of the primary approaches, their mechanisms, and performance outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of Surface Engineering Strategies for Defect Passivation in PQDs

| Strategy | Passivation Mechanism | Key Reagents / Conditions | Reported Performance Outcomes | Key Advantages & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudohalide Passivation | SCN⁻ ions strongly coordinate with uncoordinated Pb²⁺; K⁺/GA⁺ cations fill A-site vacancies. | KSCN, GASCN in acetonitrile; post-synthetic treatment [17]. | EQE: 22.1%; Luminance: 31,000 cd/m²; T₅₀: 1020 min (5x improvement) [17]. | Adv: Strong binding, suppresses ion migration. Chal: Solubility in processing solvents. |

| Multiligand Exchange | Replaces long-chain insulating ligands with short-chain conductive ones; reduces inter-dot distance. | 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) in methyl acetate [19]. | Jₛc: ~2 mA cm⁻² increase; PCE: 28% improvement; Reduced hysteresis [19]. | Adv: Enhances charge transport. Chal: Complex multi-step process. |

| Lewis Acid-Base Passivation | Molecular modifiers donate/accept electrons to neutralize undercoordinated ions and halide vacancies. | 4-guanidinobenzyl aminoguanidine hydrochloride (GBACl) [20]. | V_OC: 1.208 V (1.67 eV PSC); PCE: 21.10% (from 18.72%) [20]. | Adv: Multi-functional passivation. Chal: Molecular design complexity. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Guided Synthesis | ML models predict optimal synthesis parameters to minimize defect formation during growth. | SVR, NND models using synthesizing features (temp., precursor amounts, etc.) [15]. | High R², low RMSE/MAE in predicting PQD size, absorbance, and PL properties [15]. | Adv: Reduces trial-and-error; high prediction accuracy. Chal: Requires large, high-quality dataset. |

In-Depth Protocol: Pseudohalide Passivation for PQD LEDs

The following diagram and protocol detail the pseudohalide passivation strategy, which has demonstrated exceptional results for pure-red PQD LEDs.

Experimental Objective: To simultaneously passivate uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and halide vacancies in CsPb(Br/I)₃ PQDs via a post-synthetic treatment, thereby enhancing the efficiency and stability of pure-red PeLEDs [17].

Materials:

- Source PQDs: CsPbI₂Br QDs synthesized via a modified hot-injection method.

- Passivation Reagents: Potassium thiocyanate (KSCN, >99%) and/or Guanidinium thiocyanate (GASCN, >99%).

- Solvent: Anhydrous acetonitrile (ACN, 99.8%).

- Other Solvents: Hexane, ethyl acetate, toluene.

Detailed Procedure:

- PQD Purification: The as-synthesized CsPbI₂Br PQDs are precipitated and centrifuged. The pellet is redispersed in a minimal amount of hexane.

- Passivation Solution Preparation: A 1 mg/mL solution of KSCN (or GASCN) in anhydrous acetonitrile is prepared. Note: Acetonitrile is chosen for its ability to coordinate with and gently etch lead-rich surfaces without destroying the QD structure [17].

- Ligand Exchange Reaction: The passivation solution is added dropwise to the PQD dispersion in hexane under vigorous stirring. The mixture is stirred for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- Purification and Isolation: The treated PQDs are precipitated by adding ethyl acetate, followed by centrifugation. The supernatant, containing excess ligands and by-products, is discarded. The pellet is redispersed in toluene to form a stable colloidal solution for film fabrication.

- Film Formation and Device Fabrication: The passivated PQD ink is spin-coated onto substrates. Subsequent layers (e.g., hole transport layer, electrodes) are deposited to complete the LED device structure.

Key Characterization Techniques:

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measured using an integrating sphere to quantify the enhancement in emission efficiency after passivation.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): To confirm that the QD morphology and size distribution are maintained after treatment.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): To verify the successful binding of SCN⁻ species to the PQD surface.

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: To monitor the replacement of original long-chain ligands (OA/OAm) with thiocyanate ligands.

- Electroluminescence Testing: To evaluate the final LED performance metrics (EQE, luminance, operational stability).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful surface engineering relies on a specific set of chemical reagents. The following table lists key materials used in the featured protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Surface Passivation

| Reagent Name | Chemical Function | Role in Defect Passivation |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Thiocyanate (KSCN) | Inorganic pseudohalide salt | SCN⁻ anion acts as a bidentate ligand, strongly coordinating with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions to suppress electron trapping [17]. |

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate (GASCN) | Organic pseudohalide salt | Provides SCN⁻ for Pb²⁺ passivation; the guanidinium cation (GA⁺) can interact with the perovskite surface, potentially improving stability [17]. |

| 3-Mercaptopropionic Acid (MPA) | Short-chain organic acid with thiol group | Thiol (-SH) group has a high affinity for Pb²⁺, forming stable bonds. The short chain enhances inter-dot charge transport [19]. |

| Formamidinium Iodide (FAI) | Organic halide salt | Used in ligand exchange to provide halide ions (I⁻) that fill halide vacancies, reducing hole traps and ion migration [19]. |

| 4-Guanidinobenzyl aminoguanidine hydrochloride (GBACl) | Multifunctional molecular modifier | The carboxyl group acts as a Lewis base to undercoordinated Pb²⁺, while the protonated amine neutralizes halide vacancies as a Lewis acid [20]. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Polar aprotic solvent | Medium for pseudohalide dissolution; selectively etches poorly coordinated surface species (e.g., lead oxides) without degrading the QD core [17]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar solvent | Anti-solvent for PQD purification; used in liquid/solid-phase ligand exchange to remove long-chain ligands like OA and OAm [19]. |

The journey toward high-performance and commercially viable PQD LEDs is intrinsically linked to the effective management of surface defects, particularly halide vacancies and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. As this comparison guide illustrates, sophisticated surface engineering strategies—ranging from pseudohalide passivation and multiligand exchange to ML-guided synthesis—have proven highly effective in suppressing these defects. The experimental data confirms that such interventions directly translate to superior device metrics, including enhanced EQE, improved color stability, and extended operational lifetimes.

The choice of passivation strategy is not one-size-fits-all; it depends on the specific PQD composition, the target application, and the scale of production. Pseudohalide treatment currently stands out for its efficiency in producing high-performance red LEDs, while multiligand exchange offers a compelling route to improve charge transport in photovoltaic devices. Looking forward, the integration of high-throughput experimentation with machine learning models presents a promising pathway to accelerate the discovery of next-generation passivants, potentially moving beyond defect suppression to active functionalization of the PQD surface.

Impact of Surface Properties on Non-Radiative Recombination and PLQY

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as leading semiconductor nanomaterials for next-generation light-emitting diodes (LEDs), photocatalysis, and solar cells due to their outstanding photophysical properties, including high absorption cross-sections, efficient charge separation, and tunable emission wavelengths [21] [22]. However, the performance and stability of PQD-based optoelectronic devices are fundamentally limited by non-radiative recombination losses occurring at surface defects. The photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) serves as a critical metric quantifying the efficiency of radiative recombination processes, directly reflecting the extent of surface-mediated non-radiative losses [21]. This comparative analysis examines recent surface engineering methodologies aimed at suppressing non-radiative recombination pathways by passivating surface defects, thereby enhancing PLQY for high-performance PQD LEDs.

Surface Defects in PQDs: Origins and Recombination Mechanisms

Perovskite quantum dots possess high surface-to-volume ratios, making their optical properties exceptionally susceptible to surface chemistry. The primary origins of non-radiative recombination include:

- Halide Vacancies: Under-coordinated lead atoms and halide vacancies create deep-level traps that promote non-radiative Shockley-Read-Hall recombination, significantly reducing PLQY [21] [23]. These defects exhibit low formation energies, making them prevalent even in high-quality syntheses [21].

- Insufficient Ligand Coverage: Dynamic binding of native ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) leads to frequent desorption, creating surface defects that quench photoluminescence [24] [22].

- Stoichiometric Imbalances: Non-ideal I/Pb ratios in precursor materials (e.g., >2.000) generate iodide interstitials that act as non-radiative recombination centers [21].

The following diagram illustrates how surface defects promote non-radiative recombination and how passivation strategies counteract these pathways:

Comparative Analysis of Surface Engineering Approaches

Ligand Engineering Strategies

Ligand exchange and modification represent the most direct approach to suppress surface defect-mediated non-radiative recombination. Different ligand engineering strategies yield substantially varied outcomes in PLQY enhancement and defect suppression, as compared in Table 1.

Table 1: Performance comparison of ligand engineering strategies for PQD surface passivation

| Strategy | Mechanism | PLQY Improvement | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic-Assisted Chiral Ligand Exchange [24] | Enhanced chiral ligand (R-/S-MBA) coverage via ultrasonic desorption of native OA/OAm ligands | Not explicitly quantified, but gEL ~0.28 and EQE ~16.8% achieved | Simultaneously imparts chirality/spin selectivity and passivates surface defects | Requires specialized chiral ligands; complex optimization |

| Acid-Assisted Ligand Passivation [25] | Replaces weak long-chain ligands with stable Pb-S-P coordination bonds | Up to 96% PLQY for CsPbBr₃ NPLs | Enhances deep-blue emission (461 nm); meets Rec. 2020 standard | Acid concentration critical to prevent degradation |

| Pseudohalogen Engineering [25] | In-situ etching of Pb-rich surfaces and defect passivation with pseudohalogen ligands | Significant improvement (specific values not provided) | Suppresses halide migration in mixed-halide PeQDs; improves film conductivity | Requires post-treatment processing steps |

| Dual-Interface Molecular Passivation [25] | Solvent-free rub-on transfer of passivation molecules preserves film integrity | Not explicitly quantified | Prevents secondary defects from solution-based processing | Novel technique requiring specialized equipment |

Precursor Engineering and Synthetic Control

Beyond post-synthetic treatments, precursor quality and synthesis conditions fundamentally influence surface defect formation. Controlled recrystallization of PbI₂ precursors to achieve optimal I/Pb stoichiometry (2.000-2.012) significantly reduces iodide interstitials that otherwise function as non-radiative recombination centers [21]. This approach demonstrates that internal defect suppression complements surface passivation in maximizing overall PLQY.

Compositional and Dimensional Engineering

Low-dimensional perovskite structures offer alternative pathways to suppress non-radiative recombination:

- Quasi-2D Perovskites: Mixed phase systems with energy funneling structures that concentrate excitons in smaller-bandgap domains, reducing access to surface traps [24].

- Chiral Perovskite QDs: Exhibit chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS) effect, generating spin-polarized carriers that form spin excitons with rapid radiative recombination, effectively competing with non-radiative pathways [24].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Engineering

Objective: Enhance chiral ligand exchange efficiency to simultaneously impart spin selectivity and improve surface passivation.

Methodology:

- Synthesize achiral CsPbBr₃ PQDs using conventional hot-injection method with OA/OAm ligands

- Prepare chiral ligand solution (R-/S-MBA in suitable solvent)

- Apply ultrasonic treatment during ligand exchange to assist desorption of native OA/OAm ligands

- Purify resulting chiral PQDs via centrifugation and redispersion

- Characterize using CD spectroscopy, CPL measurements, and mCP-AFM for spin selectivity

Key Parameters: Ultrasonic power density, treatment duration, ligand concentration, solvent system.

Objective: Achieve high PLQY in deep-blue emitting CsPbBr₃ nanoplatelets through enhanced surface passivation.

Methodology:

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ NPLs using established methods

- Prepare acid-assisted passivation solution with short-chain ligands

- Treat NPLs to replace weak long-chain ligands with stable Pb-S-P coordination bonds

- Purify passivated NPLs and fabricate LED devices

- Characterize using PLQY measurements, EL spectroscopy, and device performance testing

Key Parameters: Acid concentration, ligand type, reaction time, temperature control.

Objective: Correlate halide deposition on PQD surfaces with PLQY enhancement through electrochemical methods.

Methodology:

- Prepare CsPbBr₃ perovskite films on conductive substrates

- Employ electrochemical setup with controlled potential application

- Simultaneously monitor photoluminescence intensity during electrodeposition

- Characterize bromide deposition on surface using complementary techniques

- Correlate PLQY enhancement with halide coverage

Key Parameters: Applied potential, electrolyte composition, deposition time, in-situ monitoring setup.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key research reagents for PQD surface engineering and defect passivation studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| R-/S-Methylbenzylamine (MBA) | Chiral ligand for spin-selective passivation | Imparts chirality and enhances surface coverage via ultrasonic-assisted exchange [24] |

| Octylammonium Iodide (OAI) | Dual-role additive for crystallization control and defect passivation | Modulates perovskite crystallization while passivating defects in pure red PeLEDs [25] |

| Pseudohalogen Inorganic Ligands | Defect passivation via halide vacancy suppression | Post-treatment strategy for mixed-halide PeQDs to suppress halide migration [25] |

| Cetyl Trimethylammonium Bromide | Stabilizing ligand suppressing inter-ligand proton transfer | Replaces oleylamine to enhance thermal and moisture stability [22] |

| Carboxyl-functionalized Polystyrene | Matrix encapsulation for enhanced stability | Composites with PQDs via chemical interactions to inhibit environmental degradation [22] |

| Phenanthroline-based Compounds | Vacuum-deposited passivation agents | Co-evaporated with perovskite precursors for in-situ passivation of halide vacancies [25] |

Surface property optimization through advanced engineering approaches presents a critical pathway for suppressing non-radiative recombination and maximizing PLQY in PQDs. Comparative analysis demonstrates that ligand engineering strategies—including ultrasonic-assisted chiral ligand exchange, acid-assisted passivation, and pseudohalogen treatments—effectively address surface defect challenges while enabling additional functionalities like spin selectivity and enhanced stability. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit outlined provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these surface engineering approaches. As PQD LED technology advances toward commercialization, synergistic combination of these surface passivation strategies with precise synthetic control and dimensional engineering will be essential for achieving both high performance and operational stability in next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Metal halide perovskites (MHPs) have emerged as revolutionary semiconducting materials for optoelectronic devices, particularly perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (PQD LEDs). Their exceptional performance stems from a fundamental property known as defect tolerance, which distinguishes them from conventional semiconductors like silicon, GaAs, or CdTe [26]. In traditional semiconductors, even parts-per-billion levels of defects create deep-level traps within the bandgap that severely quench photoluminescence and reduce charge-carrier lifetimes [26]. In contrast, the most common native point defects in MHPs (A-site and X-site vacancies) typically form shallow-level defects that do not actively promote non-radiative recombination [26]. This inherent tolerance arises from the electronic structure of MHPs, where the valence band maximum comprises antibonding Pb(6s)-I(5p) orbitals, and the conduction band minimum primarily involves Pb(6p) orbitals [27].

However, this defect tolerance has limitations. Despite the favorable intrinsic point defect properties, surface defects and grain boundaries remain critically detrimental to device performance [28] [26]. Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions at nanocrystal surfaces, halide vacancies, and structural discontinuities at grain boundaries create charge traps that significantly impact optical properties and device stability [13] [26]. These defects become particularly problematic in PQDs due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, where surface atoms constitute a substantial fraction of the total material [26]. Consequently, sophisticated surface modification strategies have become essential for developing high-performance PQD LEDs, forming the foundation of modern perovskite optoelectronics.

Defect Types and Their Impacts on PQD Performance

Classification of Defects in Metal Halide Perovskites

Defects in metal halide perovskites manifest across multiple scales, from atomic point defects to extended structural imperfections. Point defects include vacancies (atoms missing from lattice sites), interstitials (atoms occupying non-lattice positions), and anti-site defects (atoms swapping positions) [26]. Among these, Pb²⁺ vacancies and halide vacancies are most common, with formation energies suggesting halide vacancies are most prevalent under standard conditions [27]. Structural defects encompass grain boundaries between crystalline domains, dislocations, and surface defects where the periodic lattice terminates [26]. In colloidal PQDs, surface defects dominate due to the nanoscale dimensions, with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions representing the most significant non-radiative recombination centers [13] [26].

Table: Common Defect Types in Metal Halide Perovskites and Their Characteristics

| Defect Type | Formation Energy | Trap Depth | Impact on Optoelectronic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halide Vacancy (Vₓ) | Low | Shallow | Moderate impact on non-radiative recombination |

| A-site Cation Vacancy (Vₐ) | Low | Shallow | Minimal non-radiative recombination |

| Pb²⁺ Vacancy (V_Pb) | Medium | Shallow to Medium | Contributes to non-radiative losses |

| Undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | Surface defect | Deep | Strong non-radiative recombination center |

| Grain Boundaries | N/A | Varies | Charge trapping, ion migration pathways |

Influence of Defects on Optical and Electronic Properties

Defects undermine PQD LED performance through multiple mechanisms. Non-radiative recombination at defect sites reduces photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and external quantum efficiency (EQE) in devices [28] [26]. Even with high initial PLQY, defects become critical under LED operating conditions where injected charge carrier densities are typically lower than trap densities, resulting in actual PLQY during operation being significantly lower than measured optically [27]. Additionally, defects initiate and accelerate degradation processes by acting as entry points for environmental factors like moisture and oxygen, and by facilitating ion migration across interfaces [27]. This ion migration leads to electrode corrosion and operational instability, presenting fundamental challenges for commercial applications.

Fundamental Passivation Mechanisms

Surface passivation strategies for PQDs employ distinct chemical approaches to address different types of defects. The four primary mechanisms include:

Ionic Bonding

Ionic bonding passivation utilizes charged species that electrostatically interact with surface ions. For example, halide anions (such as I⁻, Br⁻) can fill halide vacancy sites, while alkylammonium cations (such as oleylammonium) can occupy A-site cation vacancies [26]. This mechanism effectively reduces halide vacancy concentrations and provides better surface coverage, improving environmental stability [27].

Coordinate Bonding

Coordinate bonding represents one of the most effective passivation mechanisms for addressing the most problematic defects in PQDs—undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. Lewis base donors (such as phosphine oxides, thiols, or amines) donate electron pairs to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ surface sites, forming stable coordination complexes [13] [28]. Trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) demonstrates exceptional passivation efficacy, with studies showing PL intensity enhancements of 18% in CsPbI₃ PQDs through coordination with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ ions and surface defects [13].

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding interactions can stabilize surface species and improve crystallinity. Molecules containing amine groups or hydroxyl functionalities form hydrogen bonds with surface halide ions, helping to maintain structural integrity and reduce ion migration [28] [27]. While generally providing weaker passivation than coordinate bonding, hydrogen bonding often works synergistically with other mechanisms in multi-functional ligand systems.

Core-Shell Structures

Creating core-shell architectures represents a physical passivation approach where the PQD core is encapsulated within a protective shell [28]. The shell material (typically wider bandgap semiconductors or stable oxides) physically isolates the core from environmental factors and reduces surface defect density. For blue QDs, sophisticated CdZnSe/ZnSe/ZnSeS/ZnS core-shell structures have achieved PLQYs up to 90% by effectively confining carriers and passivating interface defects [29].

Figure 1: Fundamental passivation mechanisms in perovskite quantum dots and their corresponding target defects. Each mechanism addresses specific defect types through distinct chemical interactions.

Comparative Analysis of Passivation Methods

Ligand Engineering Approaches

Ligand exchange represents the most widely employed passivation strategy for PQDs, with systematic studies revealing significant performance variations between different ligand types. Research on CsPbI₃ PQDs demonstrates that the choice of passivation ligand directly impacts optical properties and environmental stability [13].

Table: Comparative Performance of Surface Ligands on CsPbI₃ PQDs

| Ligand | Chemical Type | Passivation Mechanism | PL Enhancement | Photostability Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Phosphine oxide | Coordinate bonding | 18% | ~60% (20 days) |

| Trioctylphosphine (TOP) | Phosphine | Coordinate bonding | 16% | Data not reported |

| L-Phenylalanine (L-PHE) | Amino acid | Mixed coordinate/ionic | 3% | >70% (20 days) |

| Oleic Acid/Oleylamine | Carboxylic acid/amine | Ionic/hydrogen bonding | Baseline | ~30% (20 days) |

The data reveal important structure-property relationships: coordinate bonding via P=O groups (TOPO) provides superior initial PL enhancement, while multi-functional ligands like L-phenylalanine offer better long-term photostability despite lower immediate PL gains [13]. The enhanced stability of L-phenylalanine-modified PQDs (retaining >70% initial PL intensity after 20 days of UV exposure) highlights the importance of considering both initial performance and long-term stability in passivation design [13].

Aromatic Ligand Systems for Blue PQDs

Blue-emitting PQDs present particular challenges due to their smaller particle size and consequently higher surface-to-volume ratio. Research demonstrates that aromatic ligands with shorter chain lengths offer distinct advantages for blue QD applications [29]. Comparing oleic acid (OA) and 3-fluorocinnamate (3-F-CA) ligands reveals dramatic performance differences:

- PLQY Enhancement: 3-F-CA modification increased PLQY from 90% to 93% for blue QDs [29]

- Carrier Lifetime: Transient PL lifetime increased from 12.1 ns (OA) to 16.9 ns (3-F-CA) [29]

- Device Performance: QLEDs with 3-F-CA showed EQE of 16.4% versus 7.7% with OA—a 2.1-fold improvement [29]

The superior performance of aromatic ligands stems from dual mechanisms: stronger binding energy to the QD surface (more effective defect passivation) and π-π interactions between adjacent ligands that enhance inter-QD attraction and facilitate long-range ordered assembly [29]. Density functional theory calculations confirm higher binding energy and significantly more negative interaction energy (−0.64 eV for 3-F-CA vs −0.04 eV for OA) between modified QDs [29].

Experimental Protocols for Defect Passivation

Synthesis and Ligand Modification of CsPbI₃ PQDs

The synthesis of high-quality PQDs requires precise control over reaction parameters to minimize intrinsic defect formation [13]. A standardized protocol for CsPbI₃ PQD synthesis includes:

Precursor Preparation: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99%) and lead iodide (PbI₂, 99%) are combined with ligand modifiers (TOP, TOPO, or L-PHE) in 1-octadecene solvent [13].

Temperature Optimization: Reaction temperatures between 140°C and 180°C are systematically evaluated, with 170°C identified as optimal for achieving highest PL intensity and narrowest emission linewidth (FWHM 24-28 nm) [13].

Hot-Injection Volume Control: A hot-injection volume of 1.5 mL provides enhanced PL intensity while maintaining narrow emission profile [13].

Ligand Exchange Procedure: Purified PQDs are treated with specific ligand solutions (0.1 M concentration in hexane) at controlled ratios, followed by stirring at 80°C for 2 hours to ensure complete surface binding [13].

Purification and Characterization: PQDs are purified via centrifugation and redispersion in anhydrous hexane, followed by structural (XRD, TEM), optical (UV-Vis, PL), and surface (XPS, NMR) characterization [13].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for the synthesis and surface passivation of perovskite quantum dots, highlighting critical optimization parameters and characterization steps.

Capillary Bridge Assembly for Patterned QLEDs

For display applications, achieving patterned QLED arrays with long-range order is essential. The aromatic-enhanced capillary bridge confinement strategy represents an advanced assembly method [29]:

Surface Modification: Blue QDs are modified with 3-F-CA aromatic ligands (optimal amount: 0.7 μmol) to enhance inter-QD interactions [29].

Template Preparation: Micropillar templates and substrates with microhole arrays are fabricated using photolithography and surface-treated for appropriate hydrophilicity [29].

Capillary Bridge Formation: The blue QD liquid film with aromatic ligands is uniformly segmented using micropillar templates, forming independent capillary bridges as solvent evaporates [29].

Directed Assembly: Through controlled directional motion of the three-phase contact lines within isolated capillary bridges, highly ordered arrays of blue QD microstructures are achieved [29].

This method enables fabrication of QLED arrays with minimal pixel size of 3 μm, achieving resolution exceeding 5000 Pixels Per Inch—critical for high-resolution display applications [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for PQD Surface Passivation Studies

| Reagent | Chemical Function | Application Purpose | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Lewis base donor | Coordinate bonding to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ | 18% PL enhancement in CsPbI₃ [13] |

| 3-Fluorocinnamate (3-F-CA) | Short-chain aromatic ligand | Enhanced inter-QD interaction & charge transport | 93% PLQY in blue QDs [29] |

| L-Phenylalanine | Amino acid | Multi-functional passivation | >70% photostability after 20 days [13] |

| Oleic Acid/Oleylamine | Long-chain surfactants | Baseline synthesis & colloidal stability | Fundamental reference system [13] [29] |

| Alkylammonium Halides | Ionic compounds | A-site vacancy passivation | Improved environmental stability [27] |

The theoretical foundation for surface modification in PQDs rests on understanding the inherent defect-tolerant nature of metal halide perovskites while developing targeted strategies to address their remaining susceptibility to surface and interfacial defects. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that optimal passivation approach varies significantly depending on the target application—while coordinate bonding via phosphine oxides provides maximum immediate PL enhancement, multi-functional ligands and aromatic systems offer superior stability and device integration capabilities.

Future research directions should focus on developing multi-modal passivation systems that simultaneously address multiple defect types through complementary mechanisms. Additionally, advancing our understanding of ligand exchange kinetics and developing more environmentally benign passivators will be crucial for commercial translation. As patterning technologies and device architectures continue to evolve, surface modification strategies must adapt to maintain performance at increasingly small scales, particularly for blue-emitting materials where surface effects dominate optoelectronic behavior. The continued refinement of defect passivation methodologies promises to unlock the full potential of PQD LEDs for next-generation display and lighting technologies.

Advanced Surface Engineering Techniques for Enhanced PQD-LED Performance

Surface engineering through ligand exchange is a pivotal process in the development of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Ligands are molecules attached to PQD surfaces that control crystal growth, passivate surface defects, and determine the optoelectronic properties of the resulting materials [30]. The dynamic binding of native long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), however, leads to detachment that compromises PQD stability and performance [30]. Ligand exchange strategies address this by replacing long insulating ligands with shorter or more functional alternatives.

Conventional ligand exchange methods rely on natural competition between original and newly introduced ligands in solution or solid-state processes [31] [24] [32]. Recently, ultrasonic-assisted approaches have emerged as enhanced alternatives that significantly improve ligand exchange efficiency [31] [24]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their impacts on the chiroptoelectronic performance of PQDs for LED applications, framed within the broader context of surface engineering for PQD optoelectronics.

Performance Comparison: Conventional vs. Ultrasonic-Assisted Ligand Exchange

The table below summarizes key performance metrics achieved through conventional and ultrasonic-assisted ligand exchange strategies, based on experimental data from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Ligand Exchange Strategies

| Performance Parameter | Conventional Ligand Exchange | Ultrasonic-Assisted Ligand Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Electroluminescence Dissymmetry Factor (gEL) | Not specifically reported for conventional R-/S-MBA systems | R: 0.285; S: 0.251 [31] [24] |

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 12.6% (CsPbI₃ with OPA ligand) [33] | R: 16.8%; S: 16.0% [31] [24] |

| Spin Polarization Efficiency (P) | 27-36% (R-PQDs without US treatment) [31] [24] | 86-89% (R-PQDs with US treatment) [31] [24] |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Up to 98% (CsPbI₃ with OPA) [33] | Significantly enhanced versus non-US treated counterparts [31] [24] |

| Electrical Conductivity of QD Films | 1.1 × 10⁻³ S/m (CsPbI₃ with OPA) [33] | Not explicitly quantified, but noted as "synergistically enhanced" [31] [24] |

| Ligand Exchange Efficiency | Limited by natural ligand competition [31] [24] | Significantly improved via enhanced desorption of original ligands [31] [24] |

| Key Applications | Red PQD-LEDs [33]; Photodetectors [34] | Spin-LEDs with circularly polarized emission [31] [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Conventional Ligand Exchange Protocol

The conventional ligand exchange process typically employs a direct solution-phase approach. For CsPbI₃ QDs using octylphosphonic acid (OPA):

- Synthesis of CsPbI₃ QDs: CsPbI₃ QDs are synthesized via a hot-injection method with PbO, Cs₂CO₃, OA, OAm, and 1-octadecene (ODE) precursors [33].

- Ligand Introduction: OPA is added during synthesis to partially replace OA ligands. The strong interaction between OPA and Pb atoms effectively passivates undercoordinated Pb surface defects [33].

- Purification: QDs are purified through precipitation and centrifugation cycles to remove excess ligands and reaction byproducts [33] [32].

- Film Formation: QD films are fabricated via layer-by-layer deposition, sometimes incorporating additional solid-state ligand exchange using compounds like tetrabutylammonium iodide (TBAI) for further passivation [32].

This approach enhances PLQY and electrical conductivity by replacing long-chain OA with shorter OPA ligands, improving carrier transport while maintaining effective surface passivation [33].

Ultrasonic-Assisted Ligand Exchange Protocol

The ultrasonic-assisted method builds upon conventional approaches by incorporating ultrasonic energy:

- Base QD Synthesis: Achiral CsPbBr₃ PQDs capped with OA/OAm are synthesized using standard hot-injection methods [31] [24].

- Ultrasonic Treatment: The synthesized PQDs are treated with chiral ligand solutions (e.g., R-/S-methylbenzylamine) under ultrasonic irradiation [31] [24].

- Mechanism: Ultrasonic energy assists desorption of original OA/OAm ligands, promoting more efficient replacement with chiral ligands and enhancing surface coverage [31] [24].

- Transfer to Polar Solvents: The process enables phase transfer of QDs to polar solvents, indicating successful ligand exchange [35].

- Device Fabrication: Spin-LEDs are fabricated with a structure of ITO/poly-SAM/chiral PQDs, where the chiral PQDs serve as both spin-selective units and emissive centers [31] [24].

This strategy simultaneously enhances spin selectivity through improved chirality transfer and optoelectronic properties via superior surface passivation [31] [24].

Workflow and Strategic Decision Pathway

The diagram below illustrates the procedural workflow for both ligand exchange strategies and their impact on final PQD properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Ligand Exchange Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Ligand Exchange | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) & Oleylamine (OAm) | Native long-chain ligands for initial QD synthesis and stabilization [31] [24] [33] | Standard capping ligands in hot-injection synthesis of PQDs [31] [33] |

| R-/S-Methylbenzylamine (R-/S-MBA) | Chiral ligands for imparting spin selectivity in ultrasonic-assisted exchange [31] [24] | Creating chiral PQDs for circularly polarized LEDs [31] [24] |

| Octylphosphonic Acid (OPA) | Short-chain ligand for conventional exchange; enhances conductivity and passivation [33] | Efficient red PQD-LEDs with improved charge transport [33] |

| Tetrabutylammonium Iodide (TBAI) | Halide source for solid-state ligand exchange and surface passivation [32] | Iodide passivation of PbS QD films for solar cells [32] |

| Zinc Iodide (ZnI₂) | Hybrid ligand component providing Zn²⁺ and I⁻ ions for dual passivation [34] | PbSe CQD photodetectors with reduced trap states [34] |

| 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) | Short organic ligand for solution-phase exchange; improves interdot coupling [34] | PbSe CQD films for photodetectors [34] |

| Lead Halide Salts (e.g., PbI₂) | Inorganic ligands for solution-phase exchange; enhance stability [35] | Phase transfer of PbS CQDs for solar cells [35] |

Conventional and ultrasonic-assisted ligand exchange strategies each offer distinct advantages for different research and application goals in PQD-LED development. Conventional methods using short-chain ligands like OPA provide reliable improvements in PLQY and electrical conductivity, making them suitable for standard high-efficiency LED applications [33]. The ultrasonic-assisted approach demonstrates superior performance for specialized applications requiring chiral-induced spin selectivity, achieving unprecedented combination of high gEL and EQE in spin-LEDs [31] [24].

The choice between these strategies depends on the target application: conventional methods suffice for general efficiency improvements, while ultrasonic-assisted approaches enable advanced functionalities like circularly polarized emission. Future research will likely focus on combining elements from both strategies to further optimize PQD surface engineering for next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Surface engineering through ligand chemistry is a pivotal determinant in the performance of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Ligands anchored to the PQD surface govern critical processes including charge transport, defect passivation, environmental stability, and even novel functionalities such as spin control. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three dominant organic ligand systems: the conventional oleic acid/oleylamine (OA/OAm) pair, advanced compact ligands like formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN), and emerging chiral molecules such as R-/S-methylbenzylamine (R-/S-MBA). We objectively evaluate their performance through experimental data, detailing the methodologies that underpin these findings, to inform the selection of ligand strategies for high-performance PQD LEDs.

Performance Comparison of Ligand Systems

The following tables summarize key experimental data and performance metrics for the different ligand systems, highlighting their impact on PQD properties and device performance.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Systems on PQD Material Properties

| Ligand System | Key Function | Binding Energy (eV) | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Exciton Binding Energy (meV) | Film Conductivity (S m⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid / Oleylamine (OA/OAm) | Synthesis stabilization, steric hindrance [24] | -0.18 (OAm), -0.22 (OA) [36] | Low (Baseline) [36] | 39.1 [36] | Baseline [36] |

| Bidentate Ligand (FASCN) | Defect passivation, full surface coverage [36] | -0.91 [36] | Most notable improvement [36] | 76.3 [36] | 3.95 × 10⁻⁷ (8x higher than OA/OAm) [36] |

| Chiral Molecule (R-/S-MBA) | Chirality transfer, spin selectivity [24] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Table 2: LED Device Performance Metrics with Different Ligand Systems

| Ligand System | Device Type | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | Electroluminescence Dissymmetry Factor (gEL) | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid / Oleylamine (OA/OAm) | NIR LED (Control) | ~11.5% [36] | Not Applicable | Baseline performance [36] |

| Bidentate Ligand (FASCN) | NIR LED (FAPbI₃ QDs) | ~23% [36] | Not Applicable | Record efficiency for NIR PQD-LEDs [36] |

| Chiral Molecule (R-/S-MBA) | Spin LED (CsPbBr₃ QDs) | 16.8% (R-LED), 16.0% (S-LED) [24] | 0.285 (R-LED), 0.251 (S-LED) [24] | Simultaneously high gEL and EQE [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Implementation

Ligand Exchange on Chiral Perovskite QDs

Objective: To replace native OA/OAm ligands with chiral molecules (e.g., R-/S-MBA) to impart chirality and spin selectivity, while maintaining high photoluminescence quantum yield.

- Synthesis of Achiral PQDs: Synthesize CsPbBr₃ PQDs capped with OA/OAm ligands using the standard hot-injection method [24].

- Ultrasonic-Assisted Ligand Exchange:

- Prepare a solution containing the chiral ligand (e.g., R-MBA).

- Introduce the synthesized OA/OAm-capped PQDs into the chiral ligand solution.

- Subject the mixture to ultrasonic (US) treatment. This step is critical, as it actively assists in the desorption of the original, long-chain OA/OAm ligands, thereby significantly improving the exchange efficiency [24].

- Purification and Film Formation: Purify the resulting chiral PQDs via centrifugation and redispersion. Subsequently, deposit thin films via spin-coating for device fabrication and characterization [24].

Surface Treatment with Bidentate Ligands

Objective: To achieve full surface coverage and suppress interfacial quenching sites in near-infrared (NIR) PQDs using a short, tightly-bound bidentate ligand.

- QD Synthesis and Preparation: Synthesize FAPbI₃ QDs capped with standard OA/OAm ligands [36].

- FASCN Chemical Treatment:

- The synthesized QDs are treated with a solution of formamidine thiocyanate (FASCN).

- The liquid characteristics of FASCN allow its use without high-polarity solvents, which could otherwise damage the PQDs. Its short carbon chain (less than 3 atoms) prevents steric hindrance, enabling full surface coverage [36].

- The sulfur and nitrogen atoms in FASCN's thiocyanate group form a bidentate coordination with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the QD surface. Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations confirm a binding energy of -0.91 eV, which is fourfold higher than that of OA ligands [36].

- Film Formation and Device Fabrication: The FASCN-treated QD ink is spin-coated to form a solid film. The tight binding of the ligand prevents desorption during this process, eliminating interfacial quenching centers and resulting in films with high conductivity and excellent passivation [36].

Visualization of Ligand Strategies and Performance

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts, experimental workflows, and performance outcomes of the different ligand engineering strategies.

Ligand Engineering Concepts and Workflow

Diagram Title: Ligand Engineering Pathways for PQD LEDs

Comparative Performance Outcomes

Diagram Title: Performance Outcomes of Ligand Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Ligand Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Relevance to Ligand System |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Long-chain surfactants for colloidal synthesis and initial stabilization of PQDs [24]. | Foundation for OA/OAm system; baseline for ligand exchange processes [24] [36]. |

| Chiral Amines (e.g., R-/S-MBA) | Molecules with chiral centers that transfer chirality to the PQD lattice, enabling the CISS effect [24]. | Core component for chiral ligand system; imparts spin selectivity for CP-LEDs [24]. |

| Formamidine Thiocyanate (FASCN) | Short, bidentate liquid ligand that passivates defects and increases QD film conductivity [36]. | Core component for compact ligand system; enables high-efficiency NIR LEDs [36]. |

| Ultrasonic Probe | Applies ultrasonic energy to a solution, facilitating the desorption of native ligands during exchange [24]. | Critical equipment for effective chiral ligand exchange to achieve high coverage [24]. |

| Magnetic Conductive Probe AFM (mCP-AFM) | Characterizes spin selectivity (CISS effect) by measuring current with spin-polarized tips [24]. | Key instrumentation for quantifying performance of chiral ligand systems [24]. |

Surface engineering is a pivotal aspect of enhancing the performance and stability of perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (PQD LEDs). Inorganic passivation layers play a critical role in shielding the sensitive perovskite core from environmental degradation while mitigating intrinsic defects that quench luminescence. Among the various strategies, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and inorganic oxide shells have emerged as two leading approaches. This guide provides a objective comparison of these methodologies, evaluating their performance based on recent experimental data and detailing the standard protocols for their application in PQD LED research. The objective is to furnish researchers with a clear, data-driven understanding of each method's advantages and limitations to inform material selection and innovation.

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a class of crystalline, porous materials constructed from metal ions or clusters coordinated with organic linkers. [37] [38] Their application in passivation leverages their unique structural properties. When used for passivation, MOFs can form a protective, porous shell around PQDs, where the pore size can be tuned to selectively block moisture and oxygen while allowing for charge transport. [39] [40] The organic linkers can also be functionalized to interact favorably with the perovskite surface, potentially pacifying surface defects.

Oxide Shells, such as those based on silicon oxide (SiO₂), titanium oxide (TiO₂), or zirconium oxide (ZrO₂), provide a dense, continuous inorganic barrier. [41] This coating physically isolates the PQD core from the environment. The passivation mechanism often involves the termination of surface dangling bonds on the perovskite crystal by the oxide material, which reduces surface trap states that lead to non-radiative recombination. [41]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Passivation Properties

| Property | MOF Passivation | Oxide Shell Passivation |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Nature | Crystalline, porous framework [37] [38] | Dense, amorphous/crystalline, continuous layer [41] |

| Typical Thickness | Tunable, from few nm to >100 nm [40] | Typically < 10 nm [41] |

| Porosity | Tunable micro/mesoporosity (0.5 - 5 nm) [38] | Non-porous or controlled mesoporosity [41] |

| Primary Passivation Mechanism | Molecular sieving, defect site coordination, spatial confinement [39] [40] | Physical barrier formation, surface dangling bond termination [41] |

| Synthetic Typical Route | Solvothermal, in-situ growth, electrochemical deposition [38] [42] | Sol-gel, hydrolysis, atomic layer deposition (ALD) [41] |

Performance Comparison in Optoelectronic Applications

Experimental data from various studies highlight the performance implications of choosing a MOF or oxide shell passivation strategy. While direct head-to-head comparisons for PQD LEDs are limited in the search results, data from related applications like solar cells and general LEDs provide strong indicators of expected performance.

Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) is a critical metric for LED materials, indicating the efficiency of light emission. MOF passivation has been shown to enhance PLQY significantly. For instance, in perovskite-based systems, MOF passivation can lead to a relative increase in PLQY of over 50%, primarily by reducing non-radiative recombination pathways at the PQD surface. [39] Oxide shells, particularly SiO₂, also improve PLQY, but the enhancement can be more variable and depends heavily on the formation of a uniform, pinhole-free layer and the chemical compatibility between the oxide and the perovskite lattice. [43]

Operational Stability under continuous illumination or electrical driving is a key challenge for PQD LEDs. MOF coatings excel in this area due to their robust molecular sieving effect. The tunable pore windows can effectively block larger, degrading molecules like H₂O and O₂ while permitting smaller species involved in charge transport. [40] This has been demonstrated to extend the operational lifetime of devices by several hundred hours compared to unpassivated controls. [39] Oxide shells provide an excellent barrier to gas and moisture, but their rigid, inorganic nature can lead to mechanical stress or lattice mismatch at the PQD interface, which may create new defect sites over time or during device operation. [41]

Charge Transport is a double-edged sword in passivation. A thick or poorly conductive passivation layer can hinder the injection of charges into the QD. MOFs are generally insulative, but their ultra-thin, conformal nature and porous structure can allow for tunneling or hopping-based charge transport. [39] [44] Some MOFs and their derivatives are being engineered for higher conductivity. [44] Oxide shells, being wide-bandgap insulators, almost always introduce a charge transport barrier. This is often managed by keeping the shell extremely thin (a few nm) to allow for quantum tunneling, but this can come at the cost of complete coverage and protection. [41]

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Performance Data

| Performance Metric | MOF Passivation | Oxide Shell Passivation | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY Enhancement | >50% relative increase [39] | 20-40% relative increase [43] | Perovskite nanocrystal films |

| Operational Lifetime (T₅₀) | >300h (enhancement of 3x) [39] | ~200h (enhancement of 2x) [43] | Under constant illumination |

| Barrier Property | Excellent molecular sieving [40] | Excellent gas/moisture barrier [41] | Environmental stability testing |

| Impact on Charge Injection | Moderate (tunneling through thin layers) [39] [44] | Can be significant (requires ultra-thin layers) [41] | EL device efficiency measurement |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

MOF Passivation via In-Situ Growth

The in-situ growth method involves the formation of the MOF shell directly on the PQD surface, using the QD as a nucleation site.

Protocol Steps:

- PQD Surface Preparation: A solution of purified PQDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃) in a non-polar solvent (e.g., toluene) is prepared. The PQD surface is often treated with a catalytic amount of a proton scavenger or a Lewis base (e.g., dimethylphenylphosphine) to activate the surface for coordination. [38]

- Precursor Preparation: In a separate vial, the MOF precursors are dissolved. A typical recipe for a ZIF-8 shell involves dissolving zinc acetate dihydrate (

Zn(OAc)₂·2H₂O) and the organic linker 2-methylimidazole in a compatible solvent mixture (e.g., DMF and methanol). [38] [42] - Reaction Initiation: The PQD solution is rapidly injected into the vigorously stirred MOF precursor solution at a controlled temperature (e.g., room temperature or 60°C).

- Shell Growth: The reaction proceeds for a predetermined time (seconds to minutes), during which the MOF crystallizes directly onto the PQD surface. The growth time and precursor concentrations are critical for controlling shell thickness and porosity. [42]