Surface Electronic Structure of Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots: Fundamentals, Engineering, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the electronic structure of halide perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces, a critical factor governing their optoelectronic properties and biomedical applicability.

Surface Electronic Structure of Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots: Fundamentals, Engineering, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the electronic structure of halide perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces, a critical factor governing their optoelectronic properties and biomedical applicability. We explore the fundamental principles linking surface chemistry to quantum confinement and defect states, detailing advanced synthesis and surface engineering strategies that enhance stability and performance. The review critically addresses challenges such as aqueous instability and lead toxicity, presenting optimization methods and comparative analyses with conventional quantum dots. Finally, we discuss the validation of these materials for biosensing, bioimaging, and therapeutic applications, offering a roadmap for their future in clinical research.

Unraveling the Core: Fundamental Principles of Halide Perovskite QD Surface Electronic Structure

The ABX3 Crystal Lattice and Its Surface Termination

The ABX3 perovskite crystal structure, a cornerstone of modern materials science, represents a versatile platform for a wide range of optoelectronic applications. Within the context of halide perovskite quantum dot (QD) research, understanding the surface termination of this lattice is not merely a structural consideration but a fundamental determinant of electronic properties, stability, and ultimate device performance. Quantum dots, characterized by their ultrahigh surface-area-to-volume ratio, exhibit surface effects that dominate their behavior, making surface termination engineering a critical research focus [1]. This technical guide examines the ABX3 crystal lattice, its surface termination variants, and the profound implications for the electronic structure of halide perovskite QD surfaces.

The perovskite structure consists of a three-dimensional network of corner-sharing BX6 octahedra, where the A-site cation occupies the cuboctahedral cavities within this network [2]. In halide perovskites, the A-site is typically occupied by a monovalent cation (e.g., Cs+, CH3NH3+), the B-site by a divalent metal cation (e.g., Pb2+, Sn2+), and the X-site by a halide anion (e.g., I-, Br-, Cl-) [3]. The surface of this lattice, where the periodic crystal structure terminates, presents distinct compositional possibilities that significantly influence the system's total energy, electronic band structure, and chemical stability [4].

Structural Fundamentals of the ABX3 Lattice

Crystallographic Configuration

The ideal ABX3 perovskite adopts a cubic structure with space group Pm-3m, where the B-site cation is octahedrally coordinated by six X-site anions to form BX6 octahedra. These octahedra connect at their corners to create a three-dimensional network, with the A-site cation residing in the 12-coordinate interstitial spaces between them [2]. The stability of this configuration is often assessed using the Goldschmidt tolerance factor (t) and the octahedral factor (μ), which provide quantitative measures of ionic radius matching and structural feasibility.

For a stable perovskite structure, the ionic radii of A, B, and X ions must satisfy the relationship for the tolerance factor: t = (RA + RX) / [√2(RB + RX)], where RA, RB, and RX are the ionic radii of the respective sites. Typically, a tolerance factor between 0.81 and 1.11 indicates a stable perovskite structure [5]. For instance, in the newly discovered LaWN3 nitride perovskite, the calculated tolerance factor is 0.941, well within the stability region [5].

Surface Termination Variants

When the perovskite crystal is cleaved to create a surface, the termination plane can expose different chemical compositions, each with distinct properties. For the prevalent (001) surface of halide perovskites, two primary termination types dominate the scientific discussion:

- AX-Terminated Surface (e.g., MAI-T for CH3NH3PbI3): This termination exposes a layer of A-site cations and X-site anions. In methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3), this corresponds to the methylammonium iodide-terminated (MAI-T) surface [4].

- BX2-Terminated Surface (e.g., PbI2-T for CH3NH3PbI3): This termination exposes a layer of B-site cations and X-site anions. In CH3NH3PbI3, this is the lead iodide-terminated (PbI2-T) surface [4].

The relative stability and prevalence of these terminations are governed by surface energy calculations under specific equilibrium growth conditions. Research on CH3NH3PbI3 (001) surfaces demonstrates that the MAI-T termination is thermodynamically more stable than the PbI2-T termination under equilibrium growth conditions [4].

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Surface Terminations in CH3NH3PbI3 (001)

| Property | MAI-T (AX-Terminated) | PbI2-T (BX2-Terminated) |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Energy | Lower (more thermodynamically stable) [4] | Higher (less stable) [4] |

| Band Gap | Larger (~1.6 eV for 4-layer slab) [4] | Smaller (~1.4 eV for 4-layer slab) [4] |

| Thickness Dependence | Band gap decreases with increasing slab thickness [4] | Band gap insensitive to slab thickness [4] |

| Surface States | Fewer surface states near band edges [4] | Surface Pb states contribute to band gap reduction [4] |

Computational Methodologies for Surface Analysis

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Approaches

First-principles calculations based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) serve as the primary tool for investigating perovskite surface terminations and their electronic structures. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional is commonly employed for structural optimizations and ground-state energy calculations [2] [5].

For more accurate electronic property characterization, especially band gap calculations, advanced functionals such as the modified Becke-Johnson (mBJ) potential often provide results closer to experimental values [3]. For systems with heavy elements like lead, incorporating spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is essential as it significantly affects the conduction band region, reducing band gap values [3]. For instance, in CsPbI3, the mBJ-GGA band gap of 1.983 eV reduces to 1.850 eV with mBJ-GGA+SOC correction [3].

Surface Energy Calculations

The surface energy (γ) for termination α is calculated using the formula:

γ = (Eslab^α - N × Ebulk) / (2A)

where Eslab^α is the total energy of the slab model with termination α, Ebulk is the energy per formula unit in the bulk crystal, N is the number of formula units in the slab model, and A is the surface area. The factor of 2 accounts for the two surfaces of the slab model. These calculations enable researchers to determine the relative stability of different surface terminations under various chemical potentials [4].

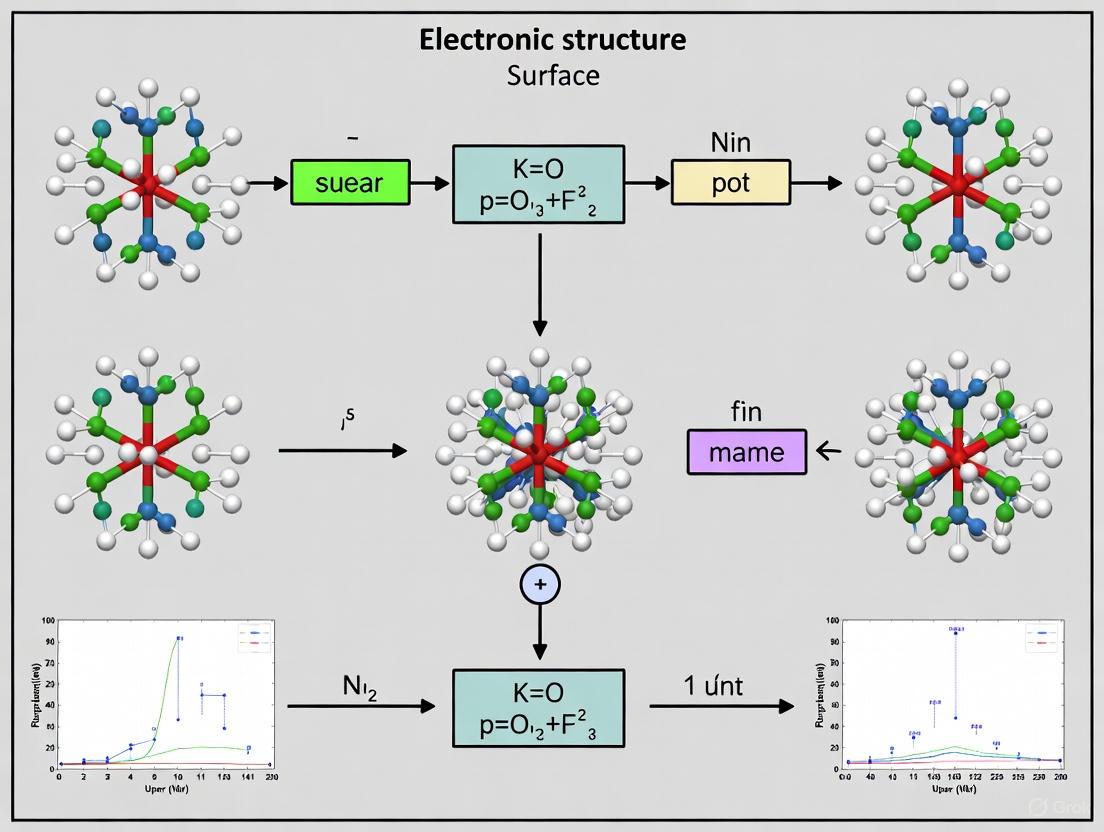

Workflow for Computational Surface Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for computational analysis of perovskite surface terminations using first-principles calculations:

Diagram 1: Workflow for computational surface analysis of perovskite surfaces.

Experimental Characterization and Synthesis Protocols

Advanced Synthesis of Perovskite Quantum Dots

The synthesis of high-quality perovskite quantum dots with controlled surfaces typically employs colloidal methods. A modified hot-injection approach has been successfully implemented for CsPbI3 QDs [6]:

- Precursor Preparation: Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) is dissolved in octadecene with oleic acid at specific temperatures under inert atmosphere. For improved reproducibility, novel cesium precursor recipes incorporating dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as short-branched-chain ligands have been developed, enhancing purity from 70.26% to 98.59% [7].

- Reaction Initiation: PbI2 precursor in octadecene with oleic acid and oleylamine is heated to 160-180°C under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Quantum Dot Formation: The cesium precursor is swiftly injected into the lead halide solution with vigorous stirring.

- Surface Engineering: Lattice-matched anchoring molecules like tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine oxide (TMeOPPO-p) can be introduced to passivate surface defects. The electron-donating P=O and -OCH3 groups interact strongly with uncoordinated Pb²⁺, with an interatomic distance of 6.5 Å matching the perovskite lattice spacing [6].

- Purification: The reaction mixture is cooled using an ice bath, and QDs are isolated by centrifugation with antisolvent addition.

Surface Termination Characterization Techniques

Multiple analytical techniques are employed to characterize the surface composition and electronic properties of perovskite QDs:

- Aberration-corrected STEM: Provides direct imaging of surface atomic structure and lattice fringes, confirming uniform cubic morphologies with clear lattice spacings (typically 6.5 Å for CsPbI3) [6].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Identifies surface elemental composition and chemical states. Shifts in Pb 4f peaks to lower binding energies indicate successful surface ligand coordination [6].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Confirms the presence and binding of organic ligands on QD surfaces by identifying characteristic functional group vibrations [6].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): ¹H and ³¹P NMR spectra verify the incorporation of phosphine oxide-based ligands like TMeOPPO-p on QD surfaces [6].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines crystal structure and phase purity without altering main diffraction peaks when proper surface ligands are applied [6].

Electronic Structure Implications of Surface Termination

Band Structure Modulations

Surface termination profoundly influences the electronic band structure of perovskite quantum dots. First-principles calculations reveal that different terminations create distinct electronic environments:

- BX2-Terminated Surfaces: Exhibit smaller band gaps due to surface states originating from the B-site cations. For CH3NH3PbI3, PbI2-terminated surfaces show significantly reduced band gaps compared to MAI-terminated surfaces [4]. The surface Pb states contribute to band gap narrowing, making these surfaces particularly sensitive to surface chemistry modifications.

- AX-Terminated Surfaces: Display larger band gaps with fewer mid-gap states. In CH3NH3PbI3, MAI-terminated surfaces show decreasing band gaps with increasing slab thickness, approaching the bulk value [4].

Projected density of states (PDOS) calculations reveal that pristine QDs possess imperfect surface sites with conspicuous trap states originating from halide vacancies or uncoordinated Pb²⁺ 6pz orbitals [6]. Lattice-matched multi-site anchoring molecules can eliminate these trap states by connecting trap states with conduction band minimum peaks, facilitating better charge transport [6].

Carrier Dynamics and Transport Properties

Surface termination directly impacts charge carrier behavior through several mechanisms:

- Effective Mass: The calculated effective masses of electrons and holes in halide perovskites are influenced by surface composition. The conduction band minimum (CBM) band edges are typically flatter than the valence band maximum (VBM), indicating that electrons generally have higher effective mass than holes [3].

- Defect States: Different terminations create distinct defect types. BX2-terminated surfaces are prone to halide vacancies and undercoordinated B-site cations, while AX-terminated surfaces may exhibit A-site cation vacancies [4] [6].

- Charge Trapping and Recombination: Unpassivated surfaces exhibit significant non-radiative recombination through defect states. Proper surface passivation can suppress Auger recombination, as demonstrated by the 70% reduction in amplified spontaneous emission threshold (from 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) in CsPbBr3 QDs with optimized surface chemistry [7].

Table 2: Electronic Properties of Selected Halide Perovskites with Different Compositions

| Perovskite Composition | Band Gap (mBJ-GGA) (eV) | Band Gap (mBJ-GGA+SOC) (eV) | Corrected Band Gap (eV) | Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbI3 | 1.983 [3] | 1.066 [3] | 1.850 [3] | Light absorber [3] |

| CsPbBr3 | 2.420 [3] | 1.478 [3] | 2.480 [3] | Solar cells, LEDs, lasers [3] |

| CsPbCl3 | 3.325 [3] | 2.182 [3] | 3.130 [3] | UV photodetectors [3] |

| CuMCl3 (M=Cr-Zn) | Close to ideal for photovoltaics [8] | N/A | N/A | Photovoltaic applications [8] |

| CaRbCl3 | N/A | N/A | Strong optical response in visible/UV [2] | UV-reflective coatings [2] |

Surface Engineering Strategies for Quantum Dot Applications

Ligand Design and Passivation Approaches

Surface termination control in perovskite QDs primarily occurs through strategic ligand engineering. Several innovative approaches have emerged:

- Lattice-Matched Molecular Anchors: Molecules like TMeOPPO-p are designed with interatomic distances (6.5 Å) matching the perovskite lattice spacing, enabling multi-site anchoring to uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. This approach achieves near-unity photoluminescence quantum yields (97%) and enhanced operational stability in QLEDs [6].

- Short-Chain Ligands: Combinations of acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as short-branched-chain ligands provide stronger binding affinity toward QDs compared to traditional oleic acid, effectively passivating surface defects and suppressing biexciton Auger recombination [7].

- Multi-Site Passivators: Molecules with multiple binding groups (e.g., P=O, -OCH3) increase coordination probability with undercoordinated surface sites. The calculated PDOS reveals that such multi-site anchoring can completely eliminate trap states that persist with single-site passivation [6].

Core/Shell Architectures

Beyond molecular passivation, core/shell nanostructures represent a powerful strategy for surface termination management:

- Electronic Structure Engineering: A protective shell layer on the perovskite QD core controls surface defects, improves stability against external environments, and optimizes optical properties through energy level adjustment [9].

- Stability Enhancement: Shell materials isolate the perovskite core from environmental factors (oxygen, moisture) that accelerate degradation while reducing surface recombination centers.

- Charge Confinement: Appropriate band alignment between core and shell materials facilitates charge carrier confinement, improving radiative recombination efficiency [9].

The following diagram illustrates the surface engineering strategies for perovskite quantum dots:

Diagram 2: Surface engineering strategies for perovskite quantum dots.

Research Reagents and Materials Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Perovskite Quantum Dot Surface Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs2CO3) | Cesium precursor for all-inorganic perovskite QDs [7] [6] | Requires high-purity sources; acetate-based recipes improve conversion to 98.59% purity [7] |

| Lead Iodide (PbI2) | Lead precursor for halide perovskite synthesis [6] | Moisture-sensitive; often used with oleic acid and oleylamine coordination |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand and reaction solvent component [7] [6] | Long alkyl chain; dynamic binding to surface sites; can be partially replaced by shorter ligands |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Co-ligand for surface passivation [6] | Nitrogen coordination to undercoordinated surface sites |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine Oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched anchoring molecule [6] | Multi-site anchor (P=O and -OCH3) with 6.5Å spacing matching perovskite lattice |

| Acetate Salts (e.g., CsAc) | Alternative cesium precursor with dual functionality [7] | AcO⁻ acts as surface passivator and improves precursor purity |

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) | Short-branched-chain ligand [7] | Stronger binding affinity than oleic acid; reduces Auger recombination |

| Octadecene (ODE) | Non-coordinating reaction solvent [6] | High-boiling point; inert atmosphere required |

The surface termination of ABX3 perovskite crystals represents a critical frontier in the pursuit of advanced quantum dot technologies with tailored electronic properties. Through a combination of computational prediction, sophisticated synthesis, and strategic surface engineering, researchers have demonstrated that control over termination chemistry enables unprecedented manipulation of optoelectronic behavior. The integration of lattice-matched molecular anchors, core/shell architectures, and precision characterization techniques continues to unravel the complex relationship between surface structure and electronic performance. As these fundamental insights mature, they pave the way for perovskite quantum dot devices that approach their theoretical efficiency and stability limits, fulfilling their promise as transformative materials for next-generation optoelectronics.

Quantum Confinement Effects on Bandgap and Emission Tunability

The electronic structure of halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) surfaces is fundamentally governed by quantum confinement effects, a phenomenon that emerges when the physical dimensions of a semiconductor nanocrystal become smaller than the Bohr radius of its exciton. This effect results in discrete energy levels and size-tunable optoelectronic properties, making PQDs exceptional candidates for next-generation applications in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, and photodetectors [10] [11]. In lead halide perovskites, the electronic structure is not only influenced by the core composition but is also profoundly sensitive to the surface chemistry and local disorder. Recent studies utilizing nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy reveal that dynamic disorder in hybrid perovskites (e.g., MAPbBr₃ and FAPbBr₃) can modulate the wave function, leading to a suppressed size-dependent confinement effect at room temperature compared to their all-inorganic counterparts (e.g., CsPbBr₃) [12]. This intricate interplay between quantum confinement and surface dynamics forms the critical foundation for this whitepaper, which aims to provide a detailed technical guide on manipulating bandgap and emission in PQDs within the broader context of electronic structure research.

Theoretical Foundations of Quantum Confinement

Quantum confinement in zero-dimensional structures, such as quantum dots, occurs when the electron and hole within an exciton are spatially confined in all three dimensions, leading to discrete, atom-like energy states [10] [11]. The extent of this confinement is determined by the relationship between the nanocrystal's size and its exciton Bohr radius (R_B), which can be calculated using the formula:

RB = ε(m0/μ)a0

where ε is the dielectric constant of the material, m0 is the mass of a free electron, μ is the reduced mass of the exciton, and a0 is the Bohr radius of hydrogen (0.53 Å) [11]. When the QD size is smaller than RB, the bandgap energy (Eg) increases, causing a blueshift in the emitted photon energy. This relationship allows for precise tuning of the photoluminescence (PL) emission wavelength by controlling the QD size during synthesis [11]. For instance, in CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ PQDs, size control between 2–10 nm enables emission tunability across the violet-to-green spectrum (409–523 nm) [13].

Table 1: Bohr Radii and Tunable Emission Ranges for Common Halide Perovskite QDs

| Perovskite Composition | Exciton Bohr Radius (approx.) | Experimentally Achieved Size Range | Emission Wavelength Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ [14] [12] | ~7 nm | 4-12 nm | 450-520 nm [13] |

| CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ (MAPbBr₃) [13] [12] | ~4 nm | 2-10 nm | 409-523 nm [13] |

| FAPbBr₃ [12] | Data not provided in search results | Data not provided in search results | Data not provided in search results |

The density of states (DOS) transforms from a continuous parabola in bulk semiconductors to a discrete, stair-like function in quantum dots [11]. This discrete electronic structure underpins the narrow emission linewidths (as low as 14 nm) and high color purity observed in PQDs, which are critical for display applications requiring wide color gamuts [13].

Experimental Evidence and Advanced Characterization

Advanced characterization techniques provide direct evidence of quantum confinement and its impact on the local electronic structure of PQDs.

Optical Spectroscopy Insights

Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy is the primary tool for observing confinement, where a blueshift in the emission peak is seen with decreasing QD size [12]. For example, high-quality CsPbBr₃ QDs can achieve a narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm and a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of up to 99% [7]. CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ QDs demonstrate PLQYs exceeding 95% due to effective surface passivation that minimizes non-radiative recombination from surface defects [13].

Probing Local Structure with NMR Spectroscopy

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly ²⁰⁷Pb NMR, serves as a powerful complementary tool to optical spectroscopy by probing the local ground-state electronic structure [12]. A key study combining optical and NMR spectroscopy on CsPbBr₃, MAPbBr₃, and FAPbBr₃ QDs revealed that while all compositions show the expected size-dependent PL energy shift, the hybrid perovskites (MAPbBr₃ and FAPbBr₃) exhibit a strongly reduced size-dependent confinement in their NMR chemical shifts at room temperature [12]. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations attribute this to disorder-induced wave function modulation caused by the dynamic motion of the organic cations (MA⁺ or FA⁺). This disorder effectively "softens" the confinement effect on the local scale. Experimental support for this was obtained by freezing the cation dynamics in MAPbBr₃ QDs, which caused the size-dependent NMR chemical shift to reappear [12]. This highlights a critical difference between the electronic structure of all-inorganic and hybrid perovskite QDs.

Synthesis and Bandgap Tuning Methodologies

Precise control over the synthesis of PQDs is paramount for achieving desired bandgaps and emission properties. The following protocols detail key synthesis and postsynthesis tuning methods.

Scalable Synthesis of CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ PQDs

Method: Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) [13]

- Principle: This room-temperature method involves dissolving perovskite precursors and coordinating ligands in a solvent, which is then rapidly injected into a poor solvent under stirring, inducing instantaneous nucleation and growth of QDs.

- Procedure:

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve MABr and PbBr₂ in a polar solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

- Ligand Addition: Add surface-capping ligands (e.g., oleic acid and oleylamine) to the precursor solution to control growth and stabilize the QDs.

- Reprecipitation: Rapidly inject the precursor solution into a non-solvent (e.g., toluene) under vigorous stirring.

- Purification: Centrifuge the resulting colloidal suspension to separate the QDs from unreacted precursors and by-products. The supernatant is discarded, and the pellet is redispersed in a solvent like hexane.

- Outcome: This method enables nanocrystal size control of 2–10 nm, achieving chemical yields above 70% and PLQYs up to 96.5% [13].

High-Reproducibility Synthesis of CsPbBr₃ PQDs

Method: Optimized Cesium Precursor Recipe [7]

- Principle: This method enhances the purity and conversion efficiency of the cesium precursor to improve batch-to-batch reproducibility and optical performance.

- Procedure:

- Precursor Design: Prepare a cesium precursor using a combination of cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) with dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as a short-branched-chain ligand.

- Reaction: Acetate aids in achieving near-complete conversion (98.59% purity) of the cesium salt, minimizing by-products.

- Surface Passivation: Both AcO⁻ and 2-HA act as surface ligands, passivating dangling bonds and suppressing non-radiative Auger recombination.

- Outcome: QDs with a uniform size distribution, a narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm, a PLQY of 99%, and a 70% reduction in the amplified spontaneous emission threshold [7].

Postsynthesis Bandgap Tuning via Femtosecond Laser Patterning

Method: Femtosecond Laser Patterning for Luminescence Control [15]

- Principle: This top-down technique uses ultrafast laser pulses to precisely modify the bandgap of pre-deposited PQD films, enabling high-resolution, multi-color patterning without additional chemistry.

- Procedure:

- Film Preparation: Deposit a solid film of PQDs (e.g., using three distinct halide perovskite solutions) onto a substrate.

- Laser Processing: Scan a femtosecond laser beam across specific regions of the film. The intense, localized energy of the laser pulses alters the nanostructure or composition of the QDs, inducing a tunable blueshift in their emission.

- Pattern Formation: By controlling laser parameters (e.g., power, scan speed), different colors can be generated side-by-side on the same film.

- Outcome: Enables fabrication of high-resolution (1.5 μm spacing), full-color (410-710 nm) patterns, streamlining the manufacturing process for display technologies [15].

The following workflow synthesizes the preparation, tuning, and characterization of perovskite quantum dots for optoelectronic applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The synthesis and optimization of high-performance PQDs rely on a specific set of chemical reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Example & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursors (e.g., Cs₂CO₃, Cs-Oleate) | Source of 'A'-site cation in all-inorganic PQDs (CsPbX₃). | Optimized recipe with acetate and 2-HA increased precursor purity to 98.59%, boosting reproducibility and PLQY to 99% [7]. |

| Organic Ammonium Salts (e.g., MABr, FAI) | Source of 'A'-site cation in hybrid organic-inorganic PQDs (e.g., MAPbBr₃, FAPbI₃). | Used in LARP synthesis of CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ PQDs for size control and emission tunability [13]. |

| Lead Halide Salts (e.g., PbBr₂, PbI₂) | Source of 'B' (Pb²⁺) and 'X' (Halide) ions in the ABX₃ perovskite structure. | A core component for achieving bright emission across the visible spectrum in lead-based PQDs [14] [13]. |

| Surface Ligands (e.g., Oleic Acid, Oleylamine, 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid) | Coordinate with surface atoms to control nanocrystal growth, prevent aggregation, and passivate surface defects. | 2-HA showed stronger binding than oleic acid, effectively suppressing Auger recombination [7]. Tartaric acid passivation retains >95% PLQY after 30 days [14]. |

| Encapsulation Matrices (e.g., ZrO₂, MOFs, PMMA) | Physically shield PQDs from environmental stressors (moisture, oxygen, heat) to enhance operational stability. | ZrO₂ and MOF encapsulation retained >80% PL in ambient conditions [13]. PMMA provides recyclable, biocompatible coatings [13]. |

| Dopants (e.g., Mn²⁺) | Partially substitute Pb²⁺ to reduce toxicity and modify optical properties/stability. | Mn²⁺ substitution halves Pb content, retains >90% PLQY, and doubles stability via stronger Mn-Br bonds [13]. |

Application in Advanced Optoelectronic Devices

The precise bandgap and emission tunability of PQDs, combined with their excellent color purity, make them ideal for high-performance devices.

- Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) and Displays: Integration of CH₃NH₃PbBr₃ PQDs with 2D materials like graphene and hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) has led to LEDs with luminous efficacies up to 121.57 lm/W and color gamut coverage exceeding 127% of the NTSC standard [13]. Femtosecond laser patterning enables high-resolution (1.5 μm), full-color (410-710 nm) patterning for next-generation displays [15].

- Lasers: The achievement of high PLQY and low Auger recombination is critical for lasing applications. Optimized CsPbBr₃ QDs exhibit a 70% reduction in amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) threshold, down to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻², facilitating low-threshold lasers [7].

- Memory Technologies: PQDs are gaining traction in non-volatile memory and neuromorphic computing. Their bandgap tunability allows for the design of resistive switching memory devices with high ON/OFF ratios, as the larger bandgap materials can exhibit higher resistivities in the high-resistance state [16].

The bandgap and emission of halide perovskite quantum dots are exquisitely controlled by the quantum confinement effect, which can be harnessed through sophisticated synthesis, precise surface engineering, and advanced patterning techniques. While the fundamental theory is well-established, ongoing research continues to reveal nuanced behaviors, such as the role of dynamic cation disorder in hybrid perovskites in modulating the local electronic structure [12]. Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) the development of universal green synthesis methods to reduce environmental impact and ensure scalability [14]; (2) the implementation of advanced stabilization strategies via compositional engineering and robust encapsulation to meet industrial durability standards [14] [13]; and (3) the integration of PQDs into novel device architectures, such as photonic memristors and neuromorphic computing systems, leveraging their unique optoelectronic synergy [16]. By deepening the understanding of the electronic structure at the PQD surface and its relationship to quantum confinement, researchers can further unlock the potential of these remarkable materials.

Halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) have emerged as a transformative class of semiconducting nanomaterials for optoelectronic applications, exhibiting exceptional properties including high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs >95%), narrow emission linewidths (14-36 nm), and readily tunable bandgaps [13] [17]. These characteristics position PQDs as superior candidates for next-generation light-emitting diodes (LEDs), displays, and quantum light sources. However, the exceptional optoelectronic performance of PQDs is critically undermined by inherent surface defects arising from their nanoscale dimensions and ionic crystal structure [17] [18]. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio characteristic of quantum dots (2-10 nm diameters) renders a significant proportion of constituent ions under-coordinated, creating localized electronic states within the bandgap that act as centers for non-radiative recombination [13] [19].

The electronic structure of PQD surfaces is predominantly compromised by two key defects: uncoordinated lead cations (Pb²⁺) and halide anion vacancies (Br⁻, I⁻) [19] [20]. These defects originate from the dynamic and ionic nature of the perovskite lattice, where ions possess relatively low migration energies, facilitating vacancy formation and ligand detachment under ambient conditions [17]. Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions, lacking proper passivation, introduce deep trap states that efficiently capture photogenerated charge carriers, promoting non-radiative decay pathways through Shockley-Read-Hall recombination [13]. Concurrently, halide vacancies not only create trap states but also facilitate ion migration under operational biases, accelerating structural degradation and phase segregation in mixed-halide PQDs [20] [21]. This defect-mediated recombination fundamentally limits the internal quantum efficiency of perovskite-based devices and impedes their commercial viability despite the outstanding intrinsic properties of PQDs [13] [17].

Atomic-Level Defect Characterization and Electronic Implications

Nature and Formation of Surface Defects

The formation of surface defects in PQDs is an inherent consequence of their nanocrystalline morphology and synthesis conditions. During crystal growth, termination at nanoscale dimensions leaves a significant population of surface ions with incomplete coordination spheres [17]. For lead halide perovskites with the general formula APbX₃ (where A = Cs⁺, CH₃NH₃⁺, HC(NH₂)₂⁺; X = Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), the primary defects include:

- Under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions: These surface sites lack the full octahedral coordination of bromine atoms, creating strong electron-withdrawing centers that trap photogenerated electrons [19].

- Halide vacancies: These are the most prevalent defects due to the low formation energy of anion vacancies in ionic crystals, generating hole traps and pathways for ion migration [20] [17].

- Organic cation vacancies: These defects, while less detrimental optically, disrupt the crystalline periodicity and may facilitate moisture ingress [13].

The propensity for defect formation is exacerbated by the ligand dynamics during PQD synthesis and purification. Traditional long-chain ligands like oleic acid and oleylamine exhibit weak binding affinities and steric hindrance due to their bent molecular structures, resulting in incomplete surface coverage [17] [18]. During purification processes with polar solvents, these weakly bound ligands readily detach, exposing fresh under-coordinated surfaces [17].

Electronic Structure of Defect States

Surface defects introduce electronic states within the PQD bandgap that profoundly influence charge carrier dynamics. First-principles calculations and spectroscopic studies reveal:

- Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions create deep trap states near the conduction band minimum, acting as efficient electron traps [19] [18]. The atomic orbitals of under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions generate localized states that extend into the bandgap, with energy positions dependent on the specific coordination environment.

- Halide vacancies introduce shallow trap states near the valence band maximum, serving as hole traps [20] [17]. These vacancies significantly reduce formation energies for other defect complexes, accelerating degradation.

- Charge trapping at these defect sites leads to the formation of trions (charged excitons) that undergo rapid non-radiative Auger recombination, effectively quenching photoluminescence [18].

The following diagram illustrates the defect-induced non-radiative recombination pathways in PQDs:

Figure 1: Defect-mediated recombination pathways in perovskite quantum dots. Surface defects create trap states that divert photogenerated excitons from radiative recombination to non-radiative decay channels.

Quantitative Impact on Optoelectronic Properties

The detrimental effects of surface defects manifest quantitatively in several key performance metrics:

- Reduced Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Defect-mediated non-radiative recombination directly competes with radiative processes, lowering PLQY. Unpassivated PQDs typically exhibit PLQYs below 50%, while effectively passivated samples can exceed 90% [13] [19].

- PL Blinking: Single-particle studies reveal pronounced fluorescence intermittency (blinking) in PQDs, where defect-induced charging creates trions that undergo non-radiative Auger recombination [18].

- Accelerated Degradation: Surface defects serve as initiation sites for environmental degradation through moisture ingress and ion migration, significantly reducing operational lifetimes [17].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Surface Defects on PQD Optoelectronic Properties

| Performance Metric | Unpassivated PQDs | Effectively Passivated PQDs | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLQY (%) | 22-50% [19] [17] | 78-96% [13] [20] | 2-4x |

| PL Lifetime (ns) | ~20 ns [18] | ~46 ns [20] | ~2.3x |

| Blinking Fraction | High (>80% OFF-time) [18] | Nearly non-blinking (<2% OFF-time) [18] | >40x reduction |

| Stability (PL Retention) | <50% after hours [17] | >80% after 100h [13] | >1.6x |

Experimental Methodologies for Defect Analysis and Passivation

Advanced Synthesis Techniques for Defect Control

Controlled synthesis represents the frontline approach for mitigating surface defects in PQDs. Several advanced methodologies enable precise control over nanocrystal surface chemistry:

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) This room-temperature technique involves dissolving perovskite precursors in a polar solvent followed by rapid injection into a non-polar solvent containing surface ligands [13]. The sudden change in solvent polarity induces instantaneous nucleation and growth of PQDs with in-situ ligand passivation. The LARP method offers scalability and compatibility with industrial manufacturing, achieving chemical yields above 70% with size control between 2-10 nm [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dissolve CH₃NH₃Br (0.75 mmol) and Pb(CH₃COO)₂·3H₂O (0.2 mmol) in 2 mL dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Prepare ligand solution containing oleic acid (2 mL) and oleylamine (0.2090 g OAmBr) in n-octane (8 mL)

- Rapidly inject the precursor solution into the vigorously stirring ligand solution

- Centrifuge at 2000× g for 3 min to remove large aggregates

- Precipitate PQDs with ethyl acetate (3:1 volume ratio) and centrifuge at 9000× g for 5 min

- Redisperse purified PQDs in n-hexane for further characterization [13] [22]

Hot-Injection Method This technique provides superior crystallinity and monodispersity through high-temperature nucleation followed by controlled growth [13]. Precursor solutions are rapidly injected into a heated solvent containing coordinating ligands, enabling precise kinetic control over nucleation and growth stages.

Ultrasonic Irradiation Synthesis This green synthesis approach utilizes high-power ultrasound to generate localized hot spots for PQD nucleation while facilitating efficient ligand coordination [13] [22]. The method offers rapid, energy-efficient production with excellent defect passivation capabilities.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for synthesizing and passivating perovskite quantum dots, highlighting key methodologies for defect control.

Surface Passivation Strategies

Ligand Engineering Approaches Strategic ligand design represents the most direct method for addressing specific surface defects:

- Short-Chain Ligands: Replacing long-chain insulating ligands (OA, OAm) with shorter alternatives (PEABr) enhances charge transport while maintaining passivation efficacy. PEABr-treated CsPbBr₃ QD films exhibit improved PLQY (78.64% vs. unpassivated) and reduced surface roughness (1.38 nm vs. 3.61 nm) [20].

- Zwitterionic Molecules: Amino acids and other zwitterions provide simultaneous passivation of both cationic and anionic surface sites through their dual functional groups. FAPbBr₃ QDs passivated with tryptophan achieved PLQYs of 87.2% through coordinated interactions with under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites [22].

- Imide Derivatives: Molecules like caffeine and 6-amino-1,3-dimethyluracil effectively passivate under-coordinated Pb²⁺ ions through carbonyl oxygen coordination, with efficacy proportional to the atomic charge of the carbonyl oxygen [19].

- π-π Stacking Ligands: Phenethylammonium (PEA) ligands facilitate attractive intermolecular interactions that promote near-epitaxial surface coverage, significantly reducing surface energy and enabling nearly non-blinking single photon emission with >98% purity [18].

Table 2: Surface Passivation Ligands and Their Mechanisms of Action

| Ligand Category | Representative Examples | Primary Defect Target | Passivation Mechanism | Performance Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Alkylammonium | PEABr [20] [18] | Br⁻ vacancies | Steric accessibility and halide compensation | PLQY: 78.64%, EQE: 9.67% [20] |

| Amino Acids | Tryptophan, Phenylalanine [22] | Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ | Lewis base coordination via -COOH/-NH₂ | PLQY: 87.2%, Luminance: >9000 cd/m² [22] |

| Imide Derivatives | Caffeine [19] | Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ | Carbonyl oxygen coordination with Pb²⁺ | Wide color gamut: 130% NTSC [19] |

| Specialized Zwitterions | AET (2-aminoethanethiol) [17] | Uncoordinated Pb²⁺ | Strong Pb²⁺-thiolate coordination | PL retention: >95% after 60min H₂O exposure [17] |

Post-Synthesis Passivation Protocols

Ligand Exchange with Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) [20]:

- Prepare purified CsPbBr₃ QDs dispersed in n-hexane (5 mg/mL)

- Add PEABr solution in isopropanol (10 mg/mL) with 1:2 molar ratio (PEABr:QDs)

- Stir the mixture at 60°C for 2 hours to facilitate ligand exchange

- Precipitate with ethyl acetate and centrifuge at 9000× g for 5 min

- Redisperse passivated QDs in n-octane for film fabrication

Amino Acid Passivation Procedure [22]:

- Synthesize FAPbBr₃ QDs via ultrasonic method with amino acid additives

- Use 1:2 molar ratio of ligand to Pb²⁺ during synthesis

- For mixed amino acid systems, use equimolar ratios (e.g., 0.05 mmol phenylalanine + 0.05 mmol tryptophan)

- Purify via centrifugation at 2000× g for 3 min, then 9000× g for 5 min with ethyl acetate

- Redisperse in n-hexane for device fabrication

Encapsulation and Structural Stabilization

Beyond molecular passivation, macroscopic stabilization strategies provide enhanced protection against environmental degradation:

- Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) Encapsulation: ZrO₂ and other MOF matrices create physical barriers against moisture and oxygen while allowing charge transport, retaining >80% PL intensity under ambient conditions [13].

- Crosslinking Strategies: Crosslinkable ligands form interconnected networks that inhibit ligand detachment, significantly improving thermal and environmental stability [17].

- Core-Shell Structures: Inorganic shells (e.g., wide-bandgap semiconductors) or polymer coatings (PMMA) provide physical isolation from environmental stressors while suppressing ion migration [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PQD Defect Passivation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Salts | Pb(CH₃COO)₂·3H₂O, Cs₂CO₃, CH₃NH₃Br, HC(NH₂)₂Br [13] [22] | Provides metal and halide ions for perovskite lattice formation | Lead acetate offers better solubility than lead halides; methylammonium provides better crystallinity [13] |

| Conventional Ligands | Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm) [13] [17] | Surface stabilization during synthesis; particle size control | Cause steric hindrance due to bent structures; low packing density [17] |

| Short-Chain Passivators | Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) [20] [18] | Defect passivation with improved charge transport | Enables π-π stacking for epitaxial surface coverage [18] |

| Amino Acid Ligands | Tryptophan, Phenylalanine, Cysteine [22] | Zwitterionic passivation of both cationic and anionic defects | Side-chain functional groups tune steric and electronic properties [22] |

| Imide Derivatives | Caffeine, 6-amino-1,3-dimethyluracil [19] | Specific passivation of uncoordinated Pb²⁺ sites | Efficacy correlates with carbonyl oxygen atomic charge [19] |

| Encapsulation Materials | ZrO₂, MOFs, PMMA [13] | Environmental protection and structural stabilization | MOFs provide porous confinement; PMMA offers solution processability [13] |

The strategic management of surface defects through coordinated passivation approaches is paramount for harnessing the exceptional optoelectronic properties of halide perovskite quantum dots. The relationship between uncoordinated ions, non-radiative recombination pathways, and macroscopic device performance underscores the critical importance of surface chemistry in PQD research. Current ligand engineering strategies, particularly those employing short-chain zwitterions, π-stacking molecules, and multifunctional passivators, have demonstrated remarkable success in suppressing defect-mediated recombination, enabling near-unity PLQYs and dramatically enhanced operational stabilities.

Future research directions will likely focus on the development of increasingly sophisticated passivation architectures that simultaneously address multiple defect types while facilitating efficient charge transport. The integration of computational screening with high-throughput experimental validation promises to accelerate the discovery of novel passivation molecules tailored to specific perovskite compositions. Furthermore, the advancement of in-situ characterization techniques will provide unprecedented insights into the dynamic nature of PQD surfaces under operational conditions, guiding the rational design of next-generation passivation strategies. As these approaches mature, the translation of laboratory-scale PQD innovations to commercially viable optoelectronic devices will become increasingly feasible, ultimately fulfilling the promise of perovskite quantum dots as transformative materials for advanced display technologies, quantum light sources, and energy conversion systems.

Influence of Surface Chemistry and Ligands on Electronic Properties

The electronic properties of halide perovskite quantum dots (QDs) are not solely defined by their intrinsic crystal structure but are profoundly influenced by their surface chemistry and the organic ligand shells that passivate them. Within the broader context of electronic structure research on halide perovskite QD surfaces, understanding this ligand-property relationship is paramount for advancing material design. Ligands serve as dynamic interfaces that mediate charge transport, influence stability, and can introduce novel electronic functionalities. Recent studies have demonstrated that strategic ligand engineering can modulate band structures, introduce surface states, and control charge carrier dynamics, thereby opening new pathways for optimizing perovskite QDs for applications in optoelectronics, quantum information science, and spintronics [23] [24] [25]. This whitepaper synthesizes current insights into the mechanisms of ligand influence, provides detailed experimental methodologies for their study, and offers a structured overview of quantitative data to guide research in this rapidly evolving field.

Ligands and Electronic Structure Modulation

Fundamental Mechanisms of Influence

Surface ligands interact with perovskite QD surfaces through specific binding motifs, primarily ionic interactions and coordination bonding. These interactions can significantly alter the electronic landscape of the QD in several key ways:

- Band Edge Perturbation: Ligands with conjugated π-electron systems can introduce their electronic states near the valence and conduction bands of the perovskite. The energy and spatial distribution of these states depend on the ligand's electronic structure and its binding geometry. When properly aligned, these ligand states can extend the material's frontier orbitals, facilitating charge transport and providing sites for chemical reactivity without inducing detrimental charge trapping [24].

- Surface State Creation: The binding event itself can induce local structural distortions at the perovskite surface. For instance, the choice of binding group (e.g., carboxylate vs. ammonium) can lead to the formation of distinctive surface states. Carboxylate groups, featuring electronegative oxygen atoms, tend to bind more strongly to lead sites than ammonium groups and can lower the energy of ligand orbitals relative to the perovskite's states [24].

- Chirality Transfer: Incorporating chiral ligands, such as R- or S-methylbenzylamine (MBA), disrupts the native centrosymmetry of the perovskite lattice. This induces chirality transfer from the molecular to the crystal structure level, enabling novel phenomena like circular dichroism, circularly polarized photoluminescence, and the chirality-induced spin selectivity (CISS) effect. This creates spin-polarized band structures and opens avenues for spintronic applications [25].

Quantitative Impact of Ligand Properties

The following table summarizes how specific ligand properties directly influence the electronic characteristics of lead halide perovskite QDs, based on computational and experimental studies.

Table 1: Correlation between ligand properties and electronic effects in lead halide perovskite QDs

| Ligand Property | Electronic Influence | Experimental Evidence/Model System |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Group | Determines binding strength and induced surface states; Carboxylates bind more strongly than ammonium groups [24]. | Computational screening on CsPbBr₃ QDs with various binding motifs [24]. |

| π-Conjugation | Extends frontier orbitals; Ligand states can appear near band edges or inside the band gap [24]. | Systematic study of ligands with varying π-electron systems on CsPbBr₃ [24]. |

| Head Group Geometry | Governs surface affinity and lattice stability; Primary ammonium (PEA) offers a superior geometric fit over phosphocholine (PC) on A-sites [23]. | MD simulations and NMR/FITR on FAPbBr₃ NCs with phospholipid ligands [23]. |

| Electron-Withdrawing Substituents | Lowers ligand orbital energies relative to perovskite states [24]. | Computational analysis of substituents on the ligand's π-system [24]. |

| Chiral Head Group | Breaks crystal symmetry, enabling spin-polarized band structures and CISS effect [25]. | Chiral halide perovskites (CHPs) using R/S-MBA ligands [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ligand Analysis

Computational Screening and Modeling

A high-throughput computational framework is essential for the initial screening and understanding of ligand effects.

- Objective: To systematically evaluate ligand binding affinity, binding modes, and the resulting electronic structure modifications.

- Methodology:

- System Setup: Model the perovskite surface (e.g., a slab of FAPbBr₃ with FABr-rich (100) planes or a CsPbBr₃ QD surface). Place the ligand of interest at a defined distance above the surface and solvate the system in a solvent model like toluene [23].

- Binding Mode Exploration: Use classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, such as replica-exchange MD, to explore possible binding modes (BM). Key modes include physisorption (BM1), displacement of a surface A-site cation (BM2) or halide anion (BM2'), and simultaneous displacement of both ions (BM3). For zwitterionic ligands like phospholipids, BM3 often dominates, where the anionic group (e.g., phosphate) coordinates to surface Pb atoms, and the cationic group (e.g., ammonium) inserts into a vacant A-site [23].

- Electronic Structure Analysis: Employ Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on the optimized ligand-surface systems. Compute the projected density of states (PDOS) to identify the introduction of ligand-induced states within the band gap or near the band edges of the perovskite [24] [26].

- Key Parameters: Binding energy, charge transfer, orbital hybridization, and Schottky barrier height (for heterostructures) [26].

Synthesis and Ligand Exchange

The following diagram illustrates a representative post-synthetic ligand exchange protocol for achieving high-integrity, luminescent QDs.

Diagram 1: Ligand exchange workflow for perovskite QDs.

- Procedure:

- Starting Nanocrystals (NCs): Synthesize NCs using a standard method, such as the trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO)/PbBr₂ room-temperature synthesis, which yields NCs with weakly bound ligands (e.g., trialkylphosphine oxides) [23].

- Ligand Solution: Prepare a solution of the target ligand (e.g., a designed phospholipid) in an aprotic solvent like toluene.

- Ligand Exchange: Mix the NC solution with the ligand solution. Incubate the mixture with stirring for 12-24 hours at room temperature to allow for the post-synthetic displacement of native ligands [23].

- Purification: Isolate the ligand-capped NCs by centrifugation. Remove the supernatant containing displaced ligands and excess free ligands. Redisperse the purified NC pellet in a desired solvent [23].

- Characterization: Proceed to validate successful ligand attachment and assess optical properties.

Characterization of Ligand Binding and Electronic Effects

- Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

- Objective: To confirm ligand binding and probe the local atomic environment.

- Protocol: Techniques like Rotational-Echo Double-Resonance (REDOR) NMR are used. For example, ³¹P-²⁰⁷Pb REDOR can detect through-space magnetic dipolar interactions between phosphorus atoms in a phosphate-containing ligand and lead atoms on the NC surface, providing direct evidence of coordination [23].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

- Objective: To identify functional groups involved in binding and observe shifts in vibrational modes upon surface attachment.

- Protocol: Acquire FTIR spectra of the free ligand and the ligand-capped NCs. Shifts in characteristic absorption bands (e.g., the P=O stretch for phosphate groups) indicate coordination to the NC surface [23].

- Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy (STS)

- Objective: To directly measure the electronic density of states and band gaps of surface-supported nanostructures.

- Protocol: Perform STS in conjunction with low-temperature scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). Acquire current-voltage (I-V) spectra at specific points on the nanostructure (e.g., a 1D chain or 2D network) to determine the local electronic gap [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for ligand design and analysis experiments

| Reagent/Ligand | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphoethanolamine (PEA) | Zwitterionic phospholipid with a primary ammonium head group; offers superior geometric fit on perovskite A-sites, enhancing stability [23]. | Passivation of FAPbBr₃, MAPbBr₃, and CsPbBr₃ NCs. |

| Carboxylate Ligands | Bind strongly to surface Pb atoms via electronegative oxygen; electronic properties tunable with substituents [24]. | Engineering surface states and modifying frontier orbitals in CsPbBr₃. |

| Chiral Ammonium Ligands (e.g., R/S-MBA) | Induce chirality transfer, breaking centrosymmetry for CPL and spintronics [25]. | Synthesis of chiral halide perovskites (CHPs). |

| Dioleyl-glycerophosphate Tails | Provide steric repulsion; branched/olefinic tails prevent crystallization, improving colloidal stability [23]. | Tail engineering for compatibility with diverse solvents. |

| PDMPO Silicaphilic Probe | Fluorescent molecular probe with pH-dependent chromaticity; senses surface charge and ionic character [28]. | Probing ionization and local environment of silica interfaces. |

| Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO) | Weakly binding ligand used in initial synthesis, easily displaced in post-synthetic exchanges [23]. | Starting ligand shell for subsequent functionalization. |

The strategic design of surface ligands is a powerful tool for tailoring the electronic properties of halide perovskite quantum dots. Moving beyond their traditional role as stabilizers, ligands are now recognized as integral components that can be rationally designed to modulate band structures, introduce spin functionality, and enhance charge transport. The experimental protocols and data compilations presented herein provide a roadmap for researchers to explore this vast design space. Future progress in this field will hinge on the continued integration of high-throughput computation, precise synthetic chemistry, and advanced characterization to establish robust structure-property relationships, ultimately accelerating the development of next-generation perovskite-based devices.

Linking Surface Electronic Structure to Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) and Color Purity

The performance of halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) in optoelectronic devices is predominantly governed by their surface electronic structure. This technical guide elucidates the fundamental relationships between surface chemistry, photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and color purity. By examining recent breakthroughs in surface ligand engineering, ionic passivation, and doping strategies, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and manipulating the surface-dominated electronic properties of PQDs. The discussions are contextualized within the broader scope of advancing sustainable and commercially viable perovskite technologies, with an emphasis on experimental methodologies for achieving near-unity PLQY and high color purity essential for next-generation displays and lighting.

Metal halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly all-inorganic CsPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I), have emerged as pivotal materials for next-generation optoelectronics due to their tunable bandgaps, high absorption coefficients, and defect-tolerant electronic structures [14] [29]. Among their defining characteristics, the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) and color purity are two critical parameters determining their suitability in applications ranging from light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to lasers. However, these properties are intrinsically linked to the surface electronic structure of the nanocrystals.

The surface of PQDs presents a complex landscape of ionic bonds and undercoordinated sites that act as traps for charge carriers, facilitating non-radiative recombination pathways that diminish PLQY [14]. Furthermore, surface disorder and stoichiometric deviations can introduce broadened emission spectra, adversely affecting color purity [7]. Consequently, precise control over the surface electronic structure through targeted chemical and structural interventions is not merely beneficial but essential for harnessing the full potential of these materials. This guide delves into the mechanisms through which surface modification influences core electronic properties and provides a detailed experimental roadmap for achieving optimal optoelectronic performance.

Core Mechanisms: How Surface Structure Dictates Optical Properties

The optical performance of PQDs is a direct consequence of their surface electronic properties. Defect states, surface energy landscape, and ligand-induced band bending collectively determine the efficiency and spectral characteristics of light emission.

Defect Tolerance and Non-Radiative Recombination

Halide perovskites exhibit a degree of innate "defect tolerance" where certain point defects form shallow trap states rather than deep-level traps that strongly promote non-radiative recombination [14]. However, undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the crystal surface constitute predominant deep-level traps that severely quench luminescence. Surface passivation strategies aim to coordinate these sites, elevating the energy level of these states out of the bandgap or suppressing their trapping cross-section. Effective passivation can reduce non-radiative recombination, thereby directly increasing the PLQY, as evidenced by reports of PLQYs soaring from initial values below 50% to near-unity 99% [7].

Surface Chemistry and Charge Carrier Dynamics

The organic-inorganic interface, defined by ligand binding, profoundly affects charge injection, extraction, and confinement. Long, insulating ligands like oleic acid and oleylamine, while stabilizing colloidal synthesis, create barriers to charge transport in devices. Conversely, short-chain or conjugated ligands can facilitate improved charge injection but may compromise stability [14]. Advanced ligand engineering employs molecules with multiple functional groups that act as bidentate or multidentate ligands, strengthening the binding affinity and more effectively passivating surface defects. For instance, the use of 2-bromohexadecanoic acid (BHA) as a bidentate ligand has yielded a PLQY as high as 97% with remarkable photostability [29].

Color Purity and Spectral Stability

Color purity is quantifiably represented by the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the emission spectrum and its chromaticity coordinates. Narrow FWHM values (e.g., 22 nm as reported in one study [7]) are indicative of high color purity, which is vital for wide color gamut displays. Surface electronic structure influences color purity through several mechanisms:

- Uniform Strain and Composition: A homogeneous surface potential minimizes Stark effect broadening.

- Suppression of Ion Migration: Surface treatments can inhibit the migration of halide ions, a phenomenon that causes phase segregation and spectral shifts under operational bias [30].

- Reduced Auger Recombination: Effective surface passivation diminishes non-radiative Auger recombination, which not only affects efficiency but can also cause spectral drift at high carrier densities [7]. The use of ligands like 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) has been shown to suppress Auger recombination effectively [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Surface Modifications on PLQY and Color Purity

| Modification Strategy | Material System | Key Outcome | Reported PLQY | Reported FWHM/Color Purity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate & 2-HA Ligands [7] | CsPbBr₃ QDs | Complete precursor conversion & defect passivation | 99% | 22 nm |

| Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF [30] | CsPbBr₃ QDs | Enhanced crystallinity, reduced trap states | 97.1% (Solution) | Not Specified |

| Bidentate Ligand (BHA) [29] | CsPbX₃ NCs | Surface defect passivation | 97% | Not Specified |

| Boron Doping [31] | Graphene QDs | Bandgap reduction, red-shift | 29% | Near-infrared emission |

| Eu³⁺ Doping [32] | GdYGd Phosphor | Narrow line emission from 4f transitions | 58.4% | 99.5% color purity |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Engineering

This section details specific methodologies for implementing key surface modification strategies, providing a reproducible framework for researchers.

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) with Advanced Ligands

The LARP method is a versatile, room-temperature synthesis technique amenable to various ligand systems [29].

- Precursor Preparation: Prepare a 0.1 M lead bromide (PbBr₂) solution in dimethylformamide (DMF). In a separate vial, dissolve a 1.5:1 molar ratio of cesium acetate (CsOAc) and the target ligand (e.g., 2-hexyldecanoic acid) in DMF. The acetate ion (AcO⁻) acts as a co-ligand and enhances the purity of the cesium precursor [7].

- Ligand Exchange: Combine the PbBr₂ and Cs-ligand solutions under stirring. The short-chain ligands dynamically coordinate with the Pb²⁺ sites during nucleation.

- Precipitation and Purification: Rapidly inject the precursor mixture into a non-solvent (e.g., toluene) under vigorous stirring. Centrifuge the resulting suspension to isolate the QDs. Wash the pellet with an anti-solvent to remove unbound ligands and reaction byproducts.

- Characterization: The success of passivation can be confirmed via Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to verify ligand binding and transient photoluminescence (TRPL) to measure prolonged carrier lifetime, indicating reduced trap-assisted recombination.

Ionic Liquid Post-Treatment for Defect Suppression

A post-synthetic treatment with ionic liquids (ILs) effectively passivates defects without disrupting the crystal lattice [30].

- QD Film Formation: Deposit a film of synthesized PQDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃) via spin-coating.

- IL Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) in chlorobenzene at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL.

- Treatment Process: Gently drop-cast the IL solution onto the QD film and allow it to dwell for 60 seconds, followed by spin-coating to remove the excess solvent.

- Mechanism: The OTF⁻ anions strongly coordinate with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites (binding energy -1.49 eV), while the [BMIM]+ cations interact with halide anions, collectively suppressing both anionic and cationic defect sites [30]. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations are instrumental in verifying these binding energies and the passivation mechanism.

Surface Doping with Heteroatoms

Doping introduces heteroatoms to modify the electronic structure. While common in other QD systems like graphene [31] and gold clusters [33], the principles are applicable to perovskites.

- Dopant Incorporation: Introduce a controlled amount of dopant precursor (e.g., a boron-containing compound for GQDs [31], or metal salts for Au clusters [33]) during the hot-injection or LARP synthesis.

- Kinetic Control: Carefully regulate the reaction temperature and injection speed to ensure uniform incorporation of the dopant without inducing phase segregation.

- Electronic Effects: The dopant atoms can introduce new energy levels within the bandgap, alter the HOMO-LUMO gap, and modify the charge distribution on the surface, leading to shifts in absorption/emission and changes in PLQY [31] [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Surface Engineering of PQDs

| Research Reagent | Function in Surface Modification | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Hexyldecanoic Acid (2-HA) [7] | Short-branched-chain ligand with strong binding affinity to QD surface; passivates defects and suppresses Auger recombination. | Superior to oleic acid; enhances reproducibility and stability. |

| Cesium Acetate (CsOAc) [7] | Dual-functional cesium precursor; acetate anion acts as a surface passivant during synthesis. | Increases precursor purity to >98%, minimizing by-products. |

| [BMIM]OTF Ionic Liquid [30] | Co-passivates anionic and cationic surface defects via strong electrostatic interactions with the QD surface. | Applied as a post-synthetic treatment; significantly boosts PLQY and device performance. |

| Oleic Acid / Oleylamine [29] | Standard long-chain ligands for colloidal stabilization during initial synthesis. | Often require partial exchange with shorter ligands for device integration. |

| 2-Bromohexadecanoic Acid (BHA) [29] | Bidentate ligand providing chelating binding to the surface, offering robust passivation. | Results in high PLQY and excellent photostability under UV irradiation. |

| Boron-based Precursors [31] | Dopant for tuning the bandgap and electronic structure of quantum dots (e.g., GQDs). | Leads to bandgap reduction and red-shift in emission; used in theoretical studies via TD-DFT. |

Visualization of Surface Modification Workflow and Electronic Effects

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for surface modification and its subsequent effect on the electronic structure of a perovskite quantum dot.

Surface Modification Workflow and Electronic Effects. The process begins with an as-synthesized QD and proceeds through analysis, modification, and characterization to yield a high-performance material. The critical electronic change involves the elimination of deep-level trap states upon effective surface passivation, leading to enhanced PLQY and color purity.

The deliberate engineering of the surface electronic structure is undeniably a cornerstone in the advancement of halide perovskite quantum dots. As detailed in this guide, strategies ranging from sophisticated ligand engineering and ionic passivation to controlled doping provide powerful means to achieve near-unity PLQY and exceptional color purity. These properties are no longer serendipitous outcomes but can be systematically targeted through a deep understanding of surface-defect interactions and charge carrier dynamics.

Future research directions will likely focus on the scalability and industrial integration of these surface modification protocols. The development of self-healing ligands and the exploration of lead-free perovskite compositions are emerging as critical areas for ensuring both operational longevity and environmental sustainability [14] [34]. Furthermore, combining multiple passivation strategies in a synergistic manner holds promise for overcoming the lingering challenges of stability under device operating conditions. By continuing to decipher and manipulate the surface electronic structure, researchers can fully unlock the potential of perovskite quantum dots, paving the way for their commercialization in high-performance optoelectronic devices.

Precision Engineering: Tailoring Surface Electronic Structure for Enhanced Performance and Biomedical Function

The electronic structure of halide perovskite quantum dot (PQD) surfaces is a cornerstone of their exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and defect tolerance [35] [36]. The synthesis methodology directly dictates surface morphology, ligand coverage, and defect density, thereby governing the final electronic characteristics. Techniques such as hot injection and ligand-assisted reprecipitation (LARP), coupled with advanced ligand engineering, provide precise control over the surface atomic and electronic landscape of PQDs [35] [29]. This whitepaper offers an in-depth technical analysis of these core synthesis platforms, framing them as essential tools for manipulating the electronic structure of PQD surfaces in pursuit of high-performance and stable materials for optoelectronic applications.

Core Synthesis Techniques: Principles and Protocols

The synthesis of halide perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) primarily relies on solution-processed methods that enable precise control over nucleation and growth. The choice of synthesis technique directly influences the crystallinity, size distribution, surface chemistry, and ultimately, the electronic and optical properties of the resulting PQDs [29].

Hot Injection Method

The hot injection method is a widely adopted synthesis technique for producing high-quality, monodisperse perovskite quantum dots with excellent crystallinity and optical properties [29] [36].

- Fundamental Principle: This method involves the rapid injection of a precursor solution into a high-temperature solvent, leading to instantaneous nucleation followed by controlled crystal growth. The sudden supersaturation creates a brief burst of nucleation, while the subsequent growth at elevated temperature allows for precise size control [29].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Preparation of Cs-oleate Precursor: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) is dissolved in a solvent like 1-octadecene (ODE) with oleic acid (OA) as a ligand. This mixture is heated under inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) until the Cs₂CO₃ is fully dissolved and a clear solution is obtained.

- Preparation of Pb-halide Precursor: Lead halide (e.g., PbBr₂) is dissolved in ODE along with coordinating ligands, typically OA and oleylamine (OAm). This mixture is dried under vacuum and then heated under inert atmosphere to a specific injection temperature (typically 140-180°C).

- Rapid Injection: The prepared Cs-oleate solution is swiftly injected into the vigorously stirred, hot Pb-halide precursor solution.

- Crystallization and Quenching: The reaction proceeds for a few seconds (e.g., 5-60 s) to allow for nanocrystal growth. The reaction is then quenched by immersing the flask in an ice-water bath.

- Purification: The crude solution is centrifuged to separate the quantum dots from unreacted precursors and larger aggregates. The supernatant is discarded, and the pellet is redispersed in a non-polar solvent like toluene or hexane [36].

- Impact on Electronic Structure: The high-temperature environment promotes the formation of highly crystalline QDs with low intrinsic defect densities. The dynamic binding of traditional ligands like OA and OAm, however, can lead to surface defects post-synthesis, which has motivated advanced ligand engineering strategies [35].

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP)

Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) is a versatile and accessible alternative to hot injection, capable of being performed at room temperature and in ambient air, which simplifies the synthesis process and reduces energy consumption [29] [36].

- Fundamental Principle: In LARP, the perovskite precursors and capping ligands are first dissolved in a polar, water-miscible "good solvent" (e.g., Dimethylformamide, DMF, or Dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO). This solution is then vigorously stirred as it is poured into a large volume of a non-polar "poor solvent" (e.g., toluene). The rapid change in solvent polarity causes instantaneous supersaturation, triggering the nucleation and growth of PQDs stabilized by the ligands [36].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Stoichiometric amounts of CsX and PbX₂ (or organic salts like MAI or FAI for hybrid perovskites) are dissolved in DMF or DMSO along with ligands such as OA and OAm.

- Antisolvent Introduction: The precursor solution is added dropwise or in a single pour into a large volume of toluene under vigorous stirring.

- QD Formation: Perovskite QDs precipitate from the solution within seconds.

- Purification: The resulting colloidal solution is centrifuged to remove unstable aggregates and obtain a clear supernatant containing the dispersed PQDs. Further purification steps may involve repeated precipitation/redispersion cycles [29].

- Impact on Electronic Structure: While LARP offers simplicity and scalability, the room-temperature synthesis can sometimes result in a higher density of surface traps compared to hot injection, due to less perfect crystallinity. The choice of ligands in the precursor solution is therefore critical for effective surface passivation and stabilization of the resulting QDs [35].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Synthesis Techniques for Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Feature | Hot Injection | Ligand-Assisted Reprecipitation (LARP) |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Temperature | High (140-200 °C) [29] | Room Temperature [36] |

| Atmosphere | Inert (N₂/Ar) required [36] | Ambient air possible [36] |

| Reaction Kinetics | Fast nucleation, controlled growth [29] | Instantaneous nucleation and growth [36] |

| Size Distribution | Narrow (high controllability) [29] | Moderate to broad [29] |

| Crystallinity | High [29] | Good [29] |

| Scalability | Moderate | High [29] |

| Key Advantage | Excellent size & crystallinity control | Simplicity, low cost, ambient conditions [29] |

| Primary Challenge | Complex setup, high-energy input | Potential for broader size distribution, solvent residues |

Ligand Engineering and Surface Electronic Structure

Ligand engineering is an indispensable strategy for modulating the surface electronic structure of PQDs, directly impacting their photoluminescence stability, charge transport properties, and environmental resilience [35] [37]. Ligands are molecules that bind to the PQD surface, passivating coordinatively unsaturated "dangling bonds" that would otherwise act as trap states for charge carriers.

The Role of Ligands and Instability Mechanisms

In traditional syntheses, long-chain alkyl ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm) are ubiquitous. OA, an X-type ligand, chelates with surface lead atoms, while OAm, an L-type ligand, binds to halide ions through hydrogen bonding [35]. These ligands facilitate nucleation and growth and prevent aggregation. However, their binding is dynamic and labile, leading to ligand detachment during purification, storage, or device operation [35]. This detachment creates surface defects—vacancies and under-coordinated ions—that introduce mid-gap states. These states promote non-radiative recombination, quench PLQY, and serve as entry points for environmental degradants like moisture and oxygen [35].

Advanced Ligand Engineering Strategies

To overcome the limitations of conventional ligands, several advanced strategies have been developed:

- In Situ vs. Post-Synthesis Ligand Exchange: Ligand engineering can be performed in situ during synthesis or as a post-synthesis treatment. In situ engineering involves introducing alternative ligands directly into the precursor solution, which are incorporated during QD formation. Post-synthesis exchange involves treating already-synthesized QDs with a solution containing new ligands, which replace the original ligands on the surface [35].

- Multidentate Ligands: Utilizing ligands with multiple binding groups (e.g., bidentate or tridentate) significantly enhances the binding affinity to the PQD surface compared to monodentate ligands like OA. For example, 2-bromohexadecanoic acid (BHA) acts as a bidentate ligand, effectively passivating surface defects and enabling a PLQY as high as 97% with remarkable stability under continuous ultraviolet irradiation [29].

- L-type Ligands: Lewis base (L-type) ligands, such as alkyl phosphines and thiophenes, can strongly coordinate with unsaturated Pb²⁺ sites on the PQD surface, effectively neutralizing these charge traps [35].

- Polymeric and Zwitterionic Ligands: Polymers and zwitterionic molecules offer multiple coordination sites along a single chain, creating a robust protective shell around the QD. Zwitterionic polymers, with their covalently linked cationic and anionic groups, have been used to create highly stable CsPbBr₃ PQD films that can even undergo photolithographic patterning [35].

The following diagram illustrates the ligand binding mechanisms and their impact on the surface electronic structure of a CsPbBr₃ PQD.

Ligand Binding and Surface Passivation Mechanisms

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis and Characterization

This section provides a detailed methodology for the synthesis and key characterization experiments relevant to analyzing PQD surfaces and their electronic structure.

Detailed Protocol: Hot Injection of CsPbBr₃ QDs

Objective: To synthesize high-quality, green-emitting CsPbBr₃ quantum dots with narrow size distribution [35] [36].

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below for reagent details. Equipment: Schlenk line or glovebox, 3-neck round-bottom flask, heating mantle with magnetic stirrer, thermometer, syringe needles, centrifuge.

Procedure: