Surface Chemical Analysis: Principles, Techniques, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles of surface chemical analysis, a critical field for understanding material properties at the nanoscale.

Surface Chemical Analysis: Principles, Techniques, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

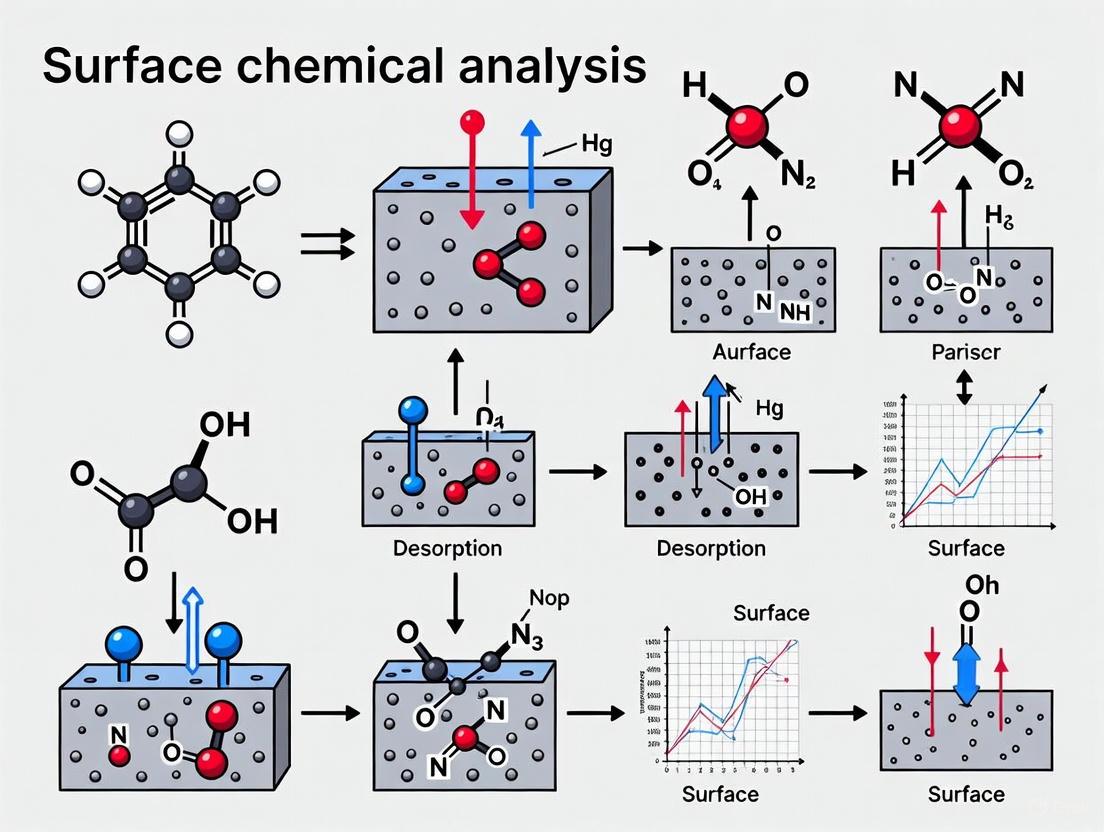

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles of surface chemical analysis, a critical field for understanding material properties at the nanoscale. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the core concepts that make surfaces—the outermost layer of atoms—dictate material behavior in applications from drug delivery to biosensors. We detail the operation of key techniques like XPS, AES, and TOF-SIMS, address common characterization challenges for complex materials like nanoparticles, and present frameworks for method validation and optimization to ensure reliable, reproducible data. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical troubleshooting and current applications, this guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging surface analysis to advance biomedical innovation and ensure product quality.

Why Surfaces Rule: Core Principles and Impact on Material Behavior

Surface chemical analysis is defined as the spatial and temporal characterization of the molecular composition, structure, and dynamics of any given sample. The ultimate goal of this field is to both understand and control complex chemical processes, which is essential to the future development of many fields of science, from materials development to drug discovery [1]. The surface represents a critical interface where key interactions determine material performance, biological activity, and chemical reactivity. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of surface analysis, framed within the broader context of basic principles governing surface chemical analysis research.

At present, imaging lies at the heart of many advances in our high-technology world. For example, microscopic imaging experiments have played a key role in the development of organic material devices used in electronics. Chemical imaging is also critical to understanding diseases such as Alzheimer's, where it provides the ability to determine molecular structure, cell structure, and communication non-destructively [1]. The ability to visualize chemical events in space and time enables researchers to probe interfacial phenomena with unprecedented detail.

Core Principles of Surface Analysis

The Concept of the Surface Interface

In analytical chemistry, the "surface" refers to the outermost atomic or molecular layers of a material where unique chemical and physical properties emerge. These properties often differ significantly from the bulk material beneath, creating an interface where critical interactions occur. Surface analysis aims to characterize these top layers, typically ranging from sub-monolayer coverage to several microns in thickness.

A fundamental challenge in surface science is that complete characterization of a complex material requires information not only on the surface or in bulk chemical components, but also on stereometric features such as size, distance, and homogeneity in three-dimensional space [1]. This multidimensional requirement drives the development of increasingly sophisticated analytical techniques.

Key Physical Principles Governing Surface Interactions

Several physical principles form the foundation of surface analysis techniques:

- Capillary Action: The fundamental principle behind liquid penetrant testing, allowing penetrants to enter surface discontinuities and later re-emerge for detection [2]

- Plasmonic Enhancement: The mechanism underlying surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) where noble metal nanomaterials dramatically amplify Raman scattered light from molecules on their surface [3]

- Quantum Tunneling: The physical basis for scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) that enables atomic-scale surface imaging

- Photoelectric Effect: Essential for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), providing elemental and chemical state information

Each of these principles is exploited by specific analytical techniques to extract different types of information about surface characteristics and interactions.

Essential Surface Analysis Techniques

Spectroscopic Methods

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is a vibrational spectroscopic technique that exploits the plasmonic and chemical properties of nanomaterials to dramatically amplify the intensity of Raman scattered light from molecules present on the surface of these materials [3]. Since its discovery 50 years ago, SERS has grown from a niche technique to one in the mainstream of academic research, finding applications in detecting chemical targets in samples ranging from bacteria to batteries [3].

The essential components of a quantitative SERS experiment include: (1) the enhancing substrate material, (2) the Raman instrument, and (3) the processed data used to establish a calibration curve [3]. As shown in Figure 1, a laser irradiates an enhancing substrate material to generate enhanced Raman scattering signals of chemical species on the substrate at various concentrations.

Table 1: Analytical Figures of Merit in SERS Quantitation

| Figure of Merit | Description | Considerations in SERS |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | Typically expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) of signal intensity | Subject to variances from instrument, substrate, and sample matrix |

| Accuracy | Closeness of measured value to true value | Affected by substrate-analyte interactions and calibration model |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest concentration detectable | Can reach single-molecule level under ideal conditions |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest concentration quantifiable | Determined from calibration curve with acceptable precision and accuracy |

| Quantitation Range | Concentration range over which reliable measurements can be made | Limited by saturation of enhancing sites at higher concentrations |

SERS offers significant advantages over established techniques like GC-MS, including potential for cheaper, faster, and portable analysis while maintaining sensitivity and molecular specificity [3]. This makes SERS particularly valuable for challenging analytical problems such as bedside diagnostics and in-field forensic analysis [3].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS is a quantitative technique that measures elemental composition, empirical formula, chemical state, and electronic state of elements within the surface (typically top 1-10 nm). When combined with other techniques, XPS provides comprehensive surface characterization.

Microscopic and Imaging Methods

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a cutting-edge scanning probe microscopy technique which enables the visualization of surfaces with atomic or nanometer-scale resolution [4]. Its operational principle lies in measuring the force interactions between a minuscule probe tip and the sample surface.

AFM images serve as graphical representations of physical parameters captured on a surface. Essentially, they comprise a matrix of data points, each representing the measured value of an associated physical parameter. When multiple physical parameters are simultaneously measured, the resulting "multi-channel images" contain one image layer per physical property measured [4].

Table 2: Primary AFM Image Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Measured Parameters | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Topographic Analysis | Surface roughness, step height | Material surface characterization |

| Particle Analysis | Size, shape, distribution of particles/grains | Nanoparticle characterization, grain analysis |

| Nanomechanical Properties | Stiffness, elasticity, adhesion | Material properties at nanoscale |

| Phase Analysis | Surface potential | Material composition mapping |

| Force Curve Analysis | Chemical composition, molecular interactions | Biological systems, material interfaces |

AFM processing has significant impact on image quality. Key processing steps include leveling or flattening to correct unevenness caused by the scanning process, lateral calibration to correct image distortions, and noise filtering to eliminate unwanted noise through spatial filters, Fourier transforms, and other techniques [4].

Advanced Chemical Imaging Approaches

A very important goal for chemical imaging is to understand and control complex chemical processes, which ultimately requires the ability to perform multimodal or multitechnique imaging across all length and time scales [1]. Multitechnique image correlation allows for extending lateral and vertical spatial characterization of chemical phases. This approach improves spatial resolution by utilizing techniques with nanometer resolution to enhance data from techniques with micrometer resolution [1].

Examples of powerful technique combinations include:

- Combining SERS and nanoscale scanning probe techniques: Tip-enhanced SERS experiments combine high SERS enhancement factors and highly confined probed volumes with nanoscale-controlled scanning [1]

- Combining X-rays, electrons, and scanning probe microscopies: Integrating these three techniques enables investigation of the chemical (X-ray, infrared, or Raman), structural (EM), and topographic (SPM) nature of samples [1]

Data fusion techniques combine data from multiple methods to perform inferences that may not be possible from a single technique, forming a new image containing more interpretable information [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantitative SERS Analysis Protocol

Principle: SERS quantitation relies on measuring the enhanced Raman signal intensity of an analyte at various concentrations to establish a calibration curve for unknown samples [3].

Materials:

- Enhancing substrate (aggregated Ag or Au colloids recommended for non-specialists) [3]

- Raman instrument with appropriate laser wavelength

- Internal standard compounds

- Calibration standards of known concentration

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Prepare colloidal Ag or Au nanoparticles according to established protocols. Aggregate if necessary using salts or polymers to create "hot spots" [3].

- Analyte Adsorption: Incubate substrate with analyte solutions of varying concentrations for optimized dwell time to ensure consistent adsorption.

- Signal Acquisition: Acquire Raman spectra using consistent instrument parameters (laser power, integration time, number accumulations).

- Data Processing:

- Select a characteristic analyte Raman band

- Measure band height (preferred over area for reduced interference)

- Normalize using internal standard if available

- Calibration: Plot normalized signal intensity versus concentration to generate calibration curve.

- Quantitation: Apply calibration model to unknown samples and calculate concentration.

Critical Considerations:

- Since plasmonic enhancement falls off steeply with distance, substrate-analyte interactions are critical in determining successful SERS detection [3]

- SERS quantitation is subject to numerous sources of variance associated with the instrument, enhancing substrate, and sample matrix

- Use internal standards to minimize variances and improve quantification accuracy [3]

- The precision of SERS measurements is often indicated by quoting the standard deviation of the signal, but it is the standard deviation in the recovered concentration which is most useful [3]

AFM Surface Characterization Protocol

Principle: AFM measures surface topography and properties by scanning a sharp tip across the surface while monitoring tip-sample interactions [4].

Materials:

- AFM with appropriate operation mode (contact, tapping, non-contact)

- Rigid, flat sample substrates

- Calibration standards with known dimensions

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mount sample securely on substrate. Ensure surface cleanliness using appropriate solvents or plasma treatment.

- Probe Selection: Choose appropriate cantilever based on required resolution and sample properties (soft, hard, adhesive).

- Instrument Setup:

- Engage laser alignment on cantilever

- Set appropriate scan parameters (size, resolution, scan rate)

- Select operation mode based on sample characteristics

- Image Acquisition: Perform multiple scans at different locations for representative sampling.

- Image Processing [4]:

- Apply leveling/flattening to correct scanning artifacts

- Perform lateral calibration using reference standards

- Apply noise filtering if necessary (low-pass or median filters)

- Quantitative Analysis:

- Perform topographic analysis for roughness parameters

- Conduct particle analysis for size/shape distributions

- Extract nanomechanical properties if force volume mode used

Critical Considerations:

- AFM image processing has significant impact on final results and must be consistently applied [4]

- Vibration isolation is critical for high-resolution imaging

- Tip condition dramatically affects image quality; replace worn tips

- Multiple locations should be measured to ensure representative sampling

Liquid Penetrant Surface Defect Analysis

Principle: The basic principle of liquid penetrant testing (PT) is capillary action, which allows the penetrant to enter the opening of the defect, remain there when the liquid is removed from the material surface, and then re-emerge on the surface on application of a developer [2].

Materials:

- Color contrast or fluorescent penetrant

- Developer (aqueous, non-aqueous, or dry)

- Cleaning solvents and materials

- UV light source (for fluorescent method)

Procedure:

- Surface Pre-cleaning: Remove all contaminants (oil, grease, dirt) from test surface.

- Penetrant Application: Apply penetrant by dipping, brushing, or spraying.

- Dwell Time: Allow penetrant to remain on surface for specified time (typically 5-30 minutes depending on material and defect type) [2].

- Excess Penetrant Removal:

- For water-washable: Spray with water (<50 psi, <43°C)

- For post-emulsifying: Apply emulsifier followed by water spray

- For solvent-removable: Wipe with lint-free cloth moistened with solvent

- Developer Application: Apply thin, uniform developer layer by spraying, brushing, or dipping.

- Inspection: Examine under appropriate lighting (1000 lux for color contrast; UV light for fluorescent).

Critical Considerations:

- The choice and application of the method for removal of surface excess penetrant has the greatest effect on process effectiveness [2]

- Over-removal can extract penetrant from defects; under-removal creates excessive background

- Temperature should be maintained between 10-50°C throughout testing

- Developing time is critical for indication formation

Visualization of Surface Analysis Techniques

Workflow for Multimodal Surface Characterization

Diagram 1: Multimodal surface analysis workflow

SERS Quantitative Analysis Process

Diagram 2: SERS quantitative analysis process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ag/Au Colloidal Nanoparticles | SERS enhancing substrate | Aggregated colloids provide robust performance for non-specialists [3] |

| Internal Standards (Isotopic or Structural Analogs) | Signal normalization in SERS | Minimizes variances from instrument, substrate, and sample matrix [3] |

| Color Contrast Penetrants | Surface defect detection | Deep red penetrant against white developer background [2] |

| Fluorescent Penetrants | High-sensitivity defect detection | Requires UV light examination; more sensitive than color contrast [2] |

| Emulsifiers | Penetrant removal control | Used in post-emulsifying method to control removal process [2] |

| AFM Cantilevers | Surface topography probing | Choice depends on required resolution and sample properties [4] |

| Calibration Gratings | AFM dimensional calibration | Reference standards with known feature sizes [4] |

| Developer Solutions | Penetrant visualization | Draws penetrant from defects via blotting action; forms uniform white coating [2] |

Applications in Drug Development and Materials Research

Surface analysis techniques play a critical role in pharmaceutical development and materials characterization. The Surface and Trace Chemical Analysis Group at NIST supports safety, security, and forensics with projects ranging from developing contraband screening technologies to nuclear particle analysis and forensics [5]. Specific applications include:

- Drug Analysis and Opioids Detection: Research focuses on measurement challenges associated with detection and analysis of synthetic opioids and novel psychoactive substances [5]. Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) is employed as a robust technique capable of differentiating a wide range of drug molecules [5].

- Personalized Medicine Development: Additive manufacturing technologies (3D printing and precision drop-on-demand deposition) enable rapid production of customizable drug formulations, requiring precise surface characterization for quality control [5].

- Illicit Narcotics Detection: IMS and other trace detection methods are being optimized for screening of illicit substances, with methods developed for evaluating spectrometers for trace detection of fentanyl and fentanyl-related substances [5].

- Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems: AFM and SERS characterize the size, shape, distribution, and surface chemistry of nanoparticles essential for drug delivery applications.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of surface chemical analysis research lies in advancing multimodal imaging capabilities and addressing current limitations. For SERS, current challenges include moving the technique from specialist use to mainstream analytical applications [3]. Promising developments include:

- Digital SERS and AI-Assisted Data Processing: Advanced computational methods to improve quantification accuracy and reliability [3]

- Multifunctional Substrates: Smart substrates with tailored surface properties for specific analytical challenges [3]

- Standardization and Protocols: Development of standardized methods to improve reproducibility across laboratories

- Miniaturization and Portability: Development of field-portable instruments for real-world analysis outside research labs

For chemical imaging broadly, a grand challenge is to achieve multimodal imaging across all length and time scales, requiring advances in computational capabilities, data fusion techniques, and instrument integration [1]. As these technologies mature, surface analysis will continue to provide critical insights into the interface where crucial interactions occur, driving innovations in drug development, materials science, and analytical chemistry.

The ability to visualize chemistry at surfaces and interfaces represents one of the most powerful capabilities in modern analytical science, enabling researchers to understand and ultimately control complex chemical processes across diverse applications from fundamental research to real-world problem solving.

The surface-to-volume ratio (SA:V) is a fundamental geometric principle describing the relationship between an object's surface area and its volume. As objects decrease in size, their surface area becomes increasingly dominant over their volume. This ratio has profound implications across physics, chemistry, and biology, but its effects become most dramatic and technologically significant at the nanoscale (1-100 nanometers) [6] [7]. For scientists conducting surface chemical analysis, understanding SA:V is not merely an academic exercise but a core principle that dictates material reactivity, stability, and functionality. Nanomaterials exhibit unique properties that differ significantly from their bulk counterparts primarily due to two factors: surface effects, which dominate as SA:V increases, and quantum effects, which become apparent when particle size approaches the quantum confinement regime [8]. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundation of SA:V, its direct impact on nanomaterial properties, and the critical analytical techniques required to characterize these effects within research and drug development contexts.

The mathematical relationship for a spherical object illustrates this concept clearly, where surface area (SA = 4πr²) increases with the square of the radius, while volume (V = 4/3πr³) increases with the cube of the radius. Consequently, the SA/V ratio for a sphere equates to 3/r, demonstrating an inverse relationship between size and SA:V [6]. This means that as the radius of a particle decreases, its SA/V ratio increases dramatically. For example, a nanoparticle with a 10 nm radius has an SA/V ratio 1000 times greater than a 1 cm particle of the same material [7]. This exponential increase in surface area relative to volume fundamentally alters how nanomaterials interact with their environment.

Theoretical Foundation: The Mathematical Principles of SA:V

The surface-to-volume ratio follows distinct scaling laws that predict how properties change with size. These relationships are described by the power law SA = aVᵇ, where 'b' represents the scaling factor [9]. When b = 1, surface area scales isometrically with volume (constant SA/V). When b = ⅔, surface area follows geometric scaling, where SA/V decreases as size increases—the characteristic relationship for perfect spheres [9]. At the nanoscale, this mathematical relationship dictates that a significantly larger proportion of atoms or molecules reside on the surface compared to the interior. For example, while a macroscopic cube of material might have less than 0.1% of its atoms on the surface, a 3 nm nanoparticle can have over 50% of its atoms exposed to the environment [8]. This fundamental shift in atomic distribution creates the driving force for novel nanoscale behaviors.

Table 1: Surface Area to Volume Ratio for Spherical Particles of Different Sizes

| Particle Radius | Surface Area | Volume | SA:V Ratio | Comparative Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 cm | 12.6 cm² | 4.2 cm³ | 3 cm⁻¹ | Sugar cube |

| 1 mm | 12.6 mm² | 4.2 mm³ | 3 mm⁻¹ | Grain of sand |

| 100 nm | 1.26 × 10⁻¹³ m² | 4.2 × 10⁻¹⁸ m³ | 3 × 10⁷ m⁻¹ | Virus particle |

| 10 nm | 1.26 × 10⁻¹⁴ m² | 4.2 × 10⁻²¹ m³ | 3 × 10⁸ m⁻¹ | Protein complex |

| 1 nm | 1.26 × 10⁻¹⁵ m² | 4.2 × 10⁻²⁴ m³ | 3 × 10⁹ m⁻¹ | Molecular cluster |

The dimensional classification of nanomaterials further influences their SA:V characteristics. Zero-dimensional nanomaterials (0-D), such as quantum dots and fullerenes, have all three dimensions in the nanoscale and exhibit the highest SA:V ratios. One-dimensional nanomaterials (1-D), including nanotubes and nanorods, have one dimension outside the nanoscale. Two-dimensional nanomaterials (2-D), such as nanosheets and nanofilms, have two dimensions outside the nanoscale. Each classification presents distinct surface area profiles that influence their application in sensing, catalysis, and drug delivery platforms [8].

Impact of High SA:V on Nanomaterial Properties

Enhanced Chemical Reactivity and Catalytic Activity

The dramatically increased surface area of nanomaterials provides a greater number of active sites for chemical reactions, making them exceptionally efficient catalysts [7]. This property is exploited in applications ranging from industrial chemical processing to environmental remediation. For example, platinum nanoparticles show significantly higher catalytic activity in reactions like N₂O decomposition compared to bulk platinum, with their reactivity directly dependent on the number of atoms in the cluster [8]. The large surface area of nanomaterials also enhances their capacity for adsorption, making them ideal for water purification systems where they can interact with and break down toxic substances more efficiently than bulk materials [7]. This enhanced reactivity stems from the higher surface energy of nanomaterials, where surface atoms have fewer direct neighbors and thus higher unsaturated bonds, driving them to interact more readily with surrounding species [8].

Modified Thermal and Mechanical Properties

Nanomaterials exhibit unique thermal behaviors distinct from bulk materials, primarily due to their high SA:V ratio. The melting point of nanomaterials decreases significantly as particle size reduces, following the Gibbs-Thomson equation. For instance, 2.5 nm gold nanoparticles melt at temperatures approximately 407°C lower than bulk gold [8]. Mechanically, nanomaterials often demonstrate increased strength, hardness, and elasticity due to the increased surface area facilitating stronger interactions between surface atoms and molecules. Carbon nanotubes, with their exceptionally high surface areas, exhibit remarkable tensile strength and are incorporated into composites for aerospace engineering and biomedical devices [7]. These properties directly result from the high fraction of surface atoms, which experience different force environments compared to interior atoms.

Unique Optical and Electronic Characteristics

The optical and electrical properties of nanomaterials are profoundly influenced by their high SA:V ratio, often in conjunction with quantum confinement effects. For example, quantum dots exhibit size-tunable light absorption and emission properties dependent on their surface chemistry and structure [7]. The ancient Lycurgus Cup, which contains 50-100 nm Au and Ag nanoparticles, demonstrates this principle through its unusual optical properties—appearing green in reflected light but red in transmitted light due to surface plasmon resonance [8]. Electrically, some non-magnetic bulk materials like palladium, platinum, and gold become magnetic at the nanoscale, while the electrical conductivity of nanomaterials can be significantly altered due to their increased surface area and quantum effects [7] [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Properties Between Bulk and Nanoscale Materials

| Property | Bulk Material Behavior | Nanoscale Material Behavior | Primary Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Reactivity | Moderate to low | Significantly enhanced | High SA:V providing more active sites |

| Melting Point | Fixed, size-independent | Decreases with reducing size | Surface energy effects |

| Mechanical Strength | Standard for material | Often significantly increased | Surface atom interactions |

| Optical Behavior | Consistent, predictable | Size-dependent, tunable | Surface plasmons & quantum effects |

| Catalytic Efficiency | Moderate, non-specific | Highly efficient, selective | High SA:V and surface structure |

Analytical Methodologies for Characterizing SA:V Effects

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Cell Surface Area Using Suspended Microchannel Resonator (SMR)

Objective: To measure the scaling relationship between cell size and surface area in proliferating mammalian cells by quantifying cell surface components as a proxy for surface area.

Principle: This approach couples single-cell buoyant mass measurements via SMR with fluorescence detection of surface-labeled components, enabling high-throughput analysis (approximately 30,000 cells/hour) of SA:V relationships in near-spherical cells [9].

Methodology Details:

- Cell Preparation: Culture suspension mammalian cell lines (e.g., L1210, BaF3, THP-1) maintaining near-spherical shape. Exclude dead cells from analysis using viability markers.

- Surface Protein Labeling: Incubate live cells with cell-impermeable, amine-reactive fluorescent dye (e.g., NHS-ester conjugates) on ice for 10 minutes to prevent membrane internalization. Validate surface-specificity using microscopy controls.

- Mass and Fluorescence Measurement: Introduce labeled cells into SMR system which measures buoyant mass (accurate proxy for cell volume) simultaneously with photomultiplier tube (PMT)-based fluorescence detection of surface labels.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity (proxy for surface area) against buoyant mass (proxy for volume) for single cells. Fit data to power law (SA = aVᵇ) to determine scaling factor 'b'. A value of b ≈ 1 indicates isometric scaling (constant SA/V), while b ≈ ⅔ indicates geometric scaling (decreasing SA/V) [9].

Validation: The protocol was validated using spherical polystyrene beads with volume-labeling (scaling factor 0.99 ± 0.06) versus surface-labeling (scaling factor 0.58 ± 0.01), confirming the system's sensitivity to distinguish different scaling modes even over small size ranges [9].

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing SA:V Impact on Composite Material Properties

Objective: To determine the correlation between particle surface-to-volume ratio and the effective elastic properties of particulate composites.

Principle: Composite materials with particles of different shapes but identical composition will exhibit different mechanical properties based on the SA:V ratio of the reinforcing particles, particularly when particles are stiffer than the matrix [10].

Methodology Details:

- Particle Shape Modeling: Create digital models of particles with varying shapes (polyhedral, undulated, spherical) using analytical functions including spherical harmonics and Goursat's surface to systematically vary SA:V while controlling for other factors.

- Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Incorporate modeled particles into composite material simulations. Calculate effective elastic properties, particularly Young's moduli, using FEA under standardized boundary conditions.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare FEA results with mean-field homogenization methods (Mori-Tanaka, Lielens) for validation. Correlate effective Young's moduli with calculated SA:V ratios for each particle shape.

- Parameter Isolation: Study the specific effects of surface curvature and edge sharpness on SA:V and resulting mechanical properties by comparing particles of similar shapes with controlled geometric variations [10].

Key Finding: The effective Young's moduli of particulate composites increase with the SA:V ratio of the particles in cases where particles are stiffer than the matrix material, demonstrating how nanoscale geometry directly influences macroscopic material properties [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomaterial SA:V Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-impermeable amine-reactive dyes (NHS-ester conjugates) | Selective labeling of surface proteins without internalization | Quantifying cell surface area as proxy for SA:V in biological systems [9] |

| Maleimide-based fluorescent labels | Labeling surface protein thiol groups via alternative chemistry | Validation of surface protein scaling relationships [9] |

| Carrageenan | Induction of controlled inflammation in tissue cage models | Studying effect of SA:V on drug pharmacokinetics in confined spaces [11] |

| Silicon tubing tissue cages | Creating controlled SA/V environments for pharmacokinetic studies | Modeling drug movement in subcutaneous spaces with defined geometry [11] |

| Sol-gel precursors (e.g., tetraethyl orthosilicate) | Producing nanomaterials with controlled porosity and surface characteristics | Fabrication of nanostructured films and coatings for sensing applications [7] |

| Stabilizing ligands (e.g., thiols, polymers) | Preventing nanoparticle aggregation by reducing surface energy | Maintaining high SA:V in nanoparticle suspensions for catalytic applications [8] |

| κ-Carrageenan | Inflammatory agent for tissue cage models | Studying the effect of inflammation on drug pharmacokinetics in different SA/V environments [11] |

Implications for Surface Chemical Analysis Research

The high SA:V ratio of nanomaterials presents both opportunities and challenges for surface chemical analysis. From an analytical perspective, the increased surface area enhances sensitivity in detection systems but also amplifies potential interference from surface contamination. Research has demonstrated that nanomaterials with high surface areas react at much faster rates than monolithic materials, which must be accounted for when designing analytical protocols [6]. In pharmaceutical development, the relationship between SA:V and extraction processes must be carefully considered, as the concentration of extractables from plastic components has a complex relationship with SA/V that depends on the partition coefficient between plastic and solvent (Kp/l) [12].

For drug development professionals, the SA:V principle directly impacts delivery system design. Nanoparticles with high SA:V ratios provide greater surface area for functionalization with targeting ligands and larger capacity for drug loading per mass unit [7] [8]. The constant SA:V ratio observed in proliferating mammalian cells, maintained through plasma membrane folding, ensures sufficient plasma membrane area for critical functions including cell division, nutrient uptake, and deformation across varying cell sizes—an important consideration for cellular uptake of nanotherapeutics [9]. Understanding these relationships enables researchers to design more efficient drug carriers with optimized release profiles and targeting capabilities.

The surface-to-volume ratio represents a fundamental principle governing the unique behavior of nanoscale materials, with far-reaching implications for surface chemical analysis research and pharmaceutical development. As materials approach the nanoscale, their dramatically increased SA:V ratio drives enhanced chemical reactivity, modified thermal and mechanical properties, and unique optical and electronic behaviors. These characteristics directly enable innovative applications in drug delivery, catalysis, sensing, and materials science. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and controlling SA:V effects is essential for designing effective nanomaterial-based systems. The analytical methodologies outlined—from SMR-based biological measurements to FEA of composite materials—provide the necessary tools to quantify and leverage these relationships. As nanotechnology continues to evolve, the precise characterization and strategic utilization of surface-to-volume relationships will remain central to advancing both basic research and applied technologies across scientific disciplines.

Surface properties dictate the performance and applicability of materials across a vast range of scientific and industrial fields, from medical devices and drug delivery systems to catalysts and semiconductors. The interactions that occur at the interface between a material and its environment are governed by a set of fundamental surface characteristics. Among these, adhesion, reactivity, and biocompatibility are three critical properties that determine the success of a material in its intended application. Adhesion describes the ability of a surface to form bonds with other surfaces, a property essential for coatings, adhesives, and composite materials. Reactivity refers to a surface's propensity to participate in chemical reactions, which is paramount for catalysts, sensors, and energy storage devices. Biocompatibility defines how a material interacts with biological systems, a non-negotiable requirement for implantable medical devices, drug delivery platforms, and tissue engineering scaffolds. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core surface properties, framed within the context of surface chemical analysis research. It synthesizes current research findings, detailed experimental methodologies, and emerging characterization techniques to serve as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex landscape of surface science.

Surface Adhesion

Fundamental Mechanisms and Influencing Factors

Surface adhesion is the state in which two surfaces are held together by interfacial forces. These forces can arise from a variety of mechanisms, each dominant under different conditions and material combinations.

The primary mechanisms of adhesion include:

- Chemical Bonding: The formation of strong covalent, ionic, or coordination bonds across the interface. For instance, mussel-inspired adhesives utilize catechol groups to form robust covalent and coordination bonds with various substrates, even in wet conditions [13].

- Physical Interlocking: Mechanical entanglement at the microscale and nanoscale, where an adhesive penetrates surface irregularities of a substrate.

- Electrostatic Forces: Attraction between oppositely charged surfaces, often significant in polymeric and biological systems.

- Van der Waals Forces: Ubiquitous, though relatively weak, attractive forces between all atoms and molecules that contribute to adhesion, especially in dry conditions and at the nanoscale [14].

A critical, yet often overlooked, factor in adhesion is surface topography. Research from the multi-laboratory Surface-Topography Challenge has demonstrated that the common practice of characterizing roughness with a single parameter, such as Ra (arithmetic average roughness), is fundamentally insufficient [15] [16]. Different measurement techniques can yield Ra values varying by a factor of one million for the same surface, as each technique probes different scale ranges. A comprehensive understanding of adhesion requires topography characterization across multiple scales, as roughness at different wavelengths can profoundly influence the true contact area and mechanical interlocking potential [16] [17].

Quantitative Analysis of Adhesive Performance

The following table summarizes quantitative adhesion performance data from a recent study on additively manufactured ceramic-reinforced resins with varying content of a zwitterionic polymer (2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine or MPC) [18] [19].

Table 1: Effect of Zwitterionic Polymer (MPC) Content on Resin Properties [18] [19]

| Property | CRN (0 wt% MPC) | CRM1 (1.1 wt% MPC) | CRM2 (2.2 wt% MPC) | CRM3 (3.3 wt% MPC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Roughness, Ra (μm) | ~0.050 (Reference) | 0.045 ± 0.004 | 0.046 ± 0.004 | 0.055 ± 0.009 |

| Flexural Strength (MPa) | 121.47 ± 12.53 | 131.42 ± 8.93 | 123.16 ± 10.12 | 93.54 ± 16.81 |

| Vickers Hardness (HV) | Highest | High | High | Significantly Lower |

| Contact Angle (°) | Reference | Data Not Specified | Significantly Higher | Significantly Lower |

| S. mutans Adhesion | Baseline | Data Not Specified | Significantly Reduced | Significantly Reduced |

The data illustrates a non-linear relationship between adhesive component concentration and macroscopic properties. The CRM2 formulation (2.2 wt% MPC) achieved an optimal balance, maintaining structural integrity (flexural strength and hardness) while significantly reducing microbial adhesion [18] [19].

Experimental Protocol: Microfluidic Assessment of Adhesion by Surface Display (MAPS-D)

The MAPS-D technique is a novel, semi-quantitative method for evaluating peptide adhesion to polymeric substrates like polystyrene (PS) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [20].

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 1: MAPS-D experimental workflow.

Detailed Methodology:

- Library Cloning: A library of random 15-mer peptides is generated and expressed on the surface of Escherichia coli using an autodisplay/autotransporter system. The construct includes an N-terminal His-tag for display confirmation, the variable peptide region, a (GS)(_{10}) spacer, and the autotransporter protein embedded in the cell's outer membrane [20].

- Cell Culture and Peptide Display: Individual bacterial cells, each displaying a single peptide variant, are cultured. Surface display is confirmed via the His-tag epitope, obviating the need for expensive peptide synthesis and purification [20].

- Microfluidic Assembly: A suspension of the peptide-displaying cells is introduced into a commercial microfluidic chip (e.g., from Ibidi) placed on the substrate of interest (PS or PMMA). Cells are allowed to settle and adhere under static conditions [20].

- Controlled Flow Application: A controlled flow of buffer is applied at defined rates (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mL/min) using a syringe pump. This generates shear forces that challenge the adhesion of the cells [20].

- Imaging and Quantification: The number of cells remaining adherent after each flow rate is quantified using microscopy. A "releasing force" can be estimated from the relationship between cell retention and flow rate [20].

- Data Analysis: Peptides displayed by cells that resist detachment at higher flow rates are identified as strong adhesives. This enables high-throughput down-selection from large libraries for further, more precise testing [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for Adhesion Studies

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Adhesion Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Monomer (MPC) | Imparts protein-repellent and anti-fouling properties. | Reducing microbial adhesion on dental resins [18] [19]. |

| Urethane Dimethacrylate (UDMA) | A common monomer providing mechanical strength in photopolymerizable resins. | Matrix component in additively manufactured resins [19]. |

| Silicate-based Composite Filler | Inorganic filler used to reinforce composite materials. | 60 wt% filler in AM ceramic-reinforced resins [18] [19]. |

| Autodisplay Plasmid Vector | Genetic construct for expressing peptides on the surface of E. coli. | Enables cell surface display for MAPS-D assay [20]. |

| Microfluidic Chips (Ibidi) | Pre-fabricated channels for fluid manipulation at small scales. | Platform for applying controlled shear forces in adhesion assays [20]. |

Surface Reactivity

Principles and Kinetic Analysis

Surface reactivity refers to the free energy change and activation energy associated with chemical reactions occurring at a material's surface. It is intrinsically linked to the density and arrangement of atoms at the surface, which often differ from the bulk material, creating active sites for catalysis, corrosion, or gas sensing.

Key factors governing surface reactivity include:

- Surface Energy: The excess energy at the surface of a material compared to its bulk. Higher surface energy generally correlates with greater reactivity.

- Crystallographic Plane: Different atomic arrangements on various crystal facets exhibit distinct reactivities.

- Defect Sites: Steps, kinks, and vacancies on surfaces are often highly reactive centers.

- Electronic Structure: The local density of states and work function of a surface influence its ability to donate or accept electrons during reactions.

Operando studies, such as time-resolved infrared and X-ray spectroscopy, are powerful techniques for probing surface reactions in real-time. For instance, these methods have been used to study the CO oxidation and NO reduction mechanisms on well-defined Rh(111) surfaces, providing direct insight into intermediate species and reaction pathways [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Reactive Surface Performance

The following table summarizes performance data for selected reactive surfaces from recent literature, highlighting their application in catalysis and environmental remediation.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Selected Reactive Surfaces

| Material / System | Application | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(II)-doped γ-Fe₂O₃ with Oxygen Vacancies [21] | Sulfite activation for antibiotic abatement | Iohexol abatement rate | Rapid and efficient degradation |

| Polypyrrole-Co₃O₄ Composite [21] | Zn-ion capacitor | Electrochemical performance (specific capacitance, cycling stability) | Superior performance (Synergistic effect) |

| PtFeCoNiMoY High-Entropy Alloy [21] | Oxygen evolution/reduction reaction (OER/ORR) | Bifunctional catalytic activity | Efficient performance in Zn-air batteries |

| S-scheme TiO₂/CuInS₂ Heterojunction [21] | Photocatalysis | Charge separation efficiency | Enhanced and sustainable photocatalytic activity |

Experimental Protocol: Nanoindentation for Surface Adhesion and Energy Measurement

Nanoindentation is an advanced technique that can be adapted to measure adhesion forces and calculate the Surface Free Energy (SFE), a key parameter influencing reactivity and wettability [14].

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 2: Nanoindentation adhesion measurement.

Detailed Methodology:

- System Setup: A nanoindenter equipped with a high-force-resolution sensor (e.g., capable of sub-µN resolution) and a spherical tip (e.g., 105 µm radius sapphire) is required. Displacement control is essential for accurate data [14].

- Environmental Control: Relative humidity must be rigorously controlled (<5% recommended) using a dry nitrogen purge or an environmental chamber to prevent capillary forces from confounding measurements [14].

- Approach and Contact: The tip approaches the surface at a very low velocity (e.g., 10 nm/s) with a minimal trigger force (e.g., 0.1 µN) to define initial contact and avoid plastic deformation [14].

- Loading and Dwell: A small load is applied to a shallow target depth (e.g., 20 nm). A brief dwell period (e.g., 3 s) allows for force relaxation and system stabilization [14].

- Unloading and Pull-off: The tip is retracted. The force-displacement curve is recorded, with particular attention to the "pull-off force" (F(_c)), the maximum negative force required to separate the tip from the surface [14].

- Data Analysis and SFE Calculation: The measured pull-off force is used to calculate the SFE (γ(s)) using contact mechanics models. The Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) model is used for compliant materials with large adhesion, while the Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) model is more suitable for stiff materials with smaller contact radii [14].

- JKR Model: ( Fc = - \frac{3}{2} \pi R W{12} ) where ( W{12} = 2 \sqrt{\gammas \gammat} ) (for identical surfaces)

- DMT Model: ( Fc = - 2 \pi R W{12} ) Here, R is the tip radius, and γ(_t) is the known SFE of the tip material [14].

Surface Biocompatibility

Fundamentals and Regulatory Framework

Biocompatibility is defined as the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application. It is not an intrinsic property but a dynamic interplay between the material and the biological environment. Key aspects include cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, sensitization, and hemocompatibility.

The evaluation of biocompatibility for medical devices is internationally standardized by ISO 10993-1:2025, "Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process" [22]. The 2025 update represents a significant evolution, fully integrating the biological evaluation process into a risk management framework aligned with ISO 14971 (Risk Management for Medical Devices) [22].

Essential new concepts in ISO 10993-1:2025 include:

- Biological Risk Estimation: Requires estimating biological risk based on the severity of harm and the probability of its occurrence, moving beyond a simple checklist of tests [22].

- Reasonably Foreseeable Misuse: Manufacturers must now consider how a device might be used outside its intended instructions for use (e.g., use for longer than intended) and incorporate these scenarios into the risk assessment [22].

- Total Exposure Period: The calculation of contact duration has been refined. For devices with multiple exposures, the "total exposure period" is the number of calendar days from the first to the last use, where any contact within a day counts as a full "contact day" [22].

Quantitative Analysis of Biocompatible Surface Performance

The following table summarizes key findings from a study on the biocompatibility and biological properties of additively manufactured resins, demonstrating how surface composition can be engineered to enhance performance.

Table 4: Biological Performance of AM Ceramic-Reinforced Resins with Varying MPC [18] [19]

| Biological Property | CRN (0 wt% MPC) | CRM1 (1.1 wt% MPC) | CRM2 (2.2 wt% MPC) | CRM3 (3.3 wt% MPC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. mutans Adhesion | Baseline (High) | Intermediate | Significantly Reduced (P<.001) | Significantly Reduced (P<.001) |

| S. gordonii Adhesion | Baseline (High) | Intermediate | Significantly Reduced (P<.001) | Significantly Reduced (P<.001) |

| Cytotoxicity | Non-cytotoxic | Non-cytotoxic | Non-cytotoxic | Non-cytotoxic |

| Cell Viability | Biocompatible | Biocompatible | Biocompatible | Biocompatible |

The data confirms that the incorporation of MPC significantly reduces microbial adhesion without inducing cytotoxicity, a crucial balance for preventing biofilm formation on medical devices without harming host tissues [18] [19].

Experimental Protocol: Biological Evaluation within a Risk Management Framework

The modern approach to biological safety, as mandated by ISO 10993-1:2025, is a structured, knowledge-driven process integrated within a risk management system [22].

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 3: Biocompatibility risk management process.

Detailed Methodology:

- Material and Intended Use Characterization: Gather comprehensive information on the device's materials of manufacture, including chemical composition, leachables, and processing aids. Define the intended use and, critically, any reasonably foreseeable misuse. Determine the nature and duration of body contact (e.g., skin, blood, bone) and the total exposure period based on single or multiple uses [22].

- Identify Biological Hazards: Based on the characterization, identify potential biological hazards (e.g., cytotoxicity, sensitization) that the device may present [22].

- Estimate Biological Risk: For each identified hazard, estimate the biological risk. This involves qualitatively or quantitatively assessing both the severity of the potential harm and the probability of its occurrence [22].

- Evaluate and Control Risk: Determine if the estimated risks are acceptable. If a risk is deemed unacceptable, implement risk control measures (e.g., material change, design modification, protective packaging). Re-evaluate the risk after implementing controls [22].

- Generate Biological Evaluation Report (BER): Compile a comprehensive report that documents the entire evaluation process, provides the rationale for all decisions, and concludes on the overall biological safety of the device [22].

- Post-Market Surveillance: Establish and maintain a system to collect and review production and post-market information. This data is used to verify the original risk assessment and identify any previously unanticipated biological harms [22].

The interplay between surface adhesion, reactivity, and biocompatibility forms the cornerstone of advanced material design for scientific and medical applications. As research advances, it is evident that a holistic, multi-scale approach is essential. The properties of a surface cannot be reduced to a single number or considered in isolation; understanding requires characterization from the atomic scale to the macroscopic level, often under realistic environmental conditions. The integration of novel high-throughput screening methods, such as MAPS-D, with precise techniques like nanoindentation and operando spectroscopy, provides a powerful toolkit for accelerating the development of next-generation materials. Furthermore, the evolving regulatory landscape, exemplified by the risk-management-centric ISO 10993-1:2025 standard, underscores that the successful implementation of a material, particularly in the medical field, depends not only on its intrinsic performance but also on a thorough and proactive understanding of its interactions within a complex biological system. Future progress will rely on continued interdisciplinary collaboration, leveraging insights from biology, chemistry, materials science, and engineering to precisely tailor surface properties for the challenges of drug delivery, implantable devices, and sustainable technologies.

In the realm of materials science, chemistry, and drug development, the outermost surface of a material—typically the top 1-10 nanometers—governs critical characteristics such as chemical activity, adhesion, wetness, electrical properties, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility [23]. This extreme surface sensitivity means that the chemical structure of the first few atomic layers fundamentally determines how a material interacts with its environment [23]. Surface analysis techniques have thus become indispensable for research and development (R&D) and quality management across numerous industrial and scientific research fields, enabling precise characterization of elemental composition and chemical states that exist only within this shallow surface region [23].

Achieving a comprehensive understanding of sample surfaces requires the strategic deployment of specialized analytical techniques, primarily conducted under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions to preserve surface purity and ensure accurate results [24]. These techniques provide insights not possible with bulk analysis methods, allowing researchers to correlate surface properties with material performance—a crucial capability when developing new functional materials or troubleshooting contamination issues that can compromise product quality, particularly in semiconductor manufacturing and biomedical applications [23].

Fundamental Principles of Surface-Sensitive Analysis

The Photoelectric Effect and Electron Spectroscopy

The foundational principle underlying many surface analysis techniques is the photoelectric effect, which forms the basis of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). When a material is irradiated with X-rays, electrons are ejected from the sample surface. The kinetic energy of these photoelectrons is measured and related to their binding energy through the fundamental equation:

Ebinding = Ephoton - (E_kinetic + ϕ)

where Ebinding represents the electron binding energy relative to the sample Fermi level, Ephoton is the energy of the incident X-ray photons, E_kinetic is the measured kinetic energy of the electron, and ϕ is the work function of the spectrometer [25]. This relationship enables the identification of elements present within the material and their chemical states, as each element produces a characteristic set of XPS peaks corresponding to its electron configuration (e.g., 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s) [25].

Surface Sensitivity and Information Depth

The exceptional surface sensitivity of techniques like XPS stems from the short inelastic mean free path of electrons in solids—the distance an electron can travel through a material without losing energy. This limited escape depth means that only electrons originating from the very topmost layers (typically 5-10 nm or 50-60 atoms) can exit the surface and be detected by the instrument [25]. This shallow sampling depth makes XPS and related techniques uniquely capable of analyzing the chemical composition of the outermost surface while being essentially blind to the bulk material beneath.

To maintain this surface sensitivity and prevent contamination or interference from gas molecules, surface analysis is typically conducted under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions with pressures at least one billionth that of atmospheric pressure [23]. This environment ensures that the surface remains clean during analysis and reduces gas phase interference, which is particularly crucial for experiments utilizing ion-based techniques [24].

Major Surface Analysis Techniques

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS stands as one of the most widely employed surface analysis techniques due to its versatility and quantitative capabilities. It can identify all elements except hydrogen and helium when using laboratory X-ray sources, with detection limits in the parts per thousand range under standard conditions, though parts per million (ppm) sensitivity is achievable with extended collection times or when elements are concentrated at the top surface [25].

The quantitative accuracy of XPS is excellent for homogeneous solid-state materials, with atomic percent values calculated from major XPS peaks typically accurate to 90-95% of their true value under optimal conditions [25]. Weaker signals with intensities 10-20% of the strongest peak show reduced accuracy at 60-80% of the true value, depending on the signal-to-noise ratio achieved through signal averaging [25].

Table 1: Technical Capabilities of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

| Parameter | Capability Range | Details and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Information Depth | 5-10 nm [25] | Measures the very topmost 50-60 atoms of any surface |

| Detection Limits | 0.1-1.0% atomic percent (1000-100 ppm) [25] | Can reach ppm levels with long collection times and surface concentration |

| Spatial Resolution | 10-200 μm for conventional; ~200 nm for imaging XPS with synchrotron sources [25] | Small-area XPS (SAXPS) used for analyzing small features like particles or blemishes [26] |

| Analysis Area | 1-5 mm for monochromatic beams; 10-50 mm for non-monochromatic [25] | Larger samples can be moved laterally to analyze wider areas |

| Quantitative Accuracy | 90-95% for major peaks; 60-80% for weaker signals [25] | Requires correction with relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) and normalization |

| Sample Types | Inorganic compounds, metal alloys, polymers, catalysts, glasses, ceramics, biomaterials, medical implants [25] | Hydrated samples can be analyzed by freezing and sublimating ice layers |

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) employs a focused electron beam to excite the sample and analyzes the resulting Auger electrons emitted from the surface. The Auger process occurs when an atom relaxes after electron emission, with an electron from another orbital filling the shell vacancy and the excess energy causing the emission of another electron [26]. AES provides both elemental and some chemical state information, complementing XPS data with superior spatial resolution due to the ability to focus the electron beam to a very small spot size [26] [23]. This high spatial resolution makes AES particularly valuable for analyzing metal and semiconductor surfaces and for identifying microscopic foreign substances on surfaces [23].

Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS)

TOF-SIMS represents an extremely surface-sensitive technique that uses high-speed primary ions to bombard the sample surface, then analyzes the secondary ions emitted using time-of-flight mass spectrometry. This approach provides exceptional surface sensitivity and can obtain organic compound molecular mass information along with high-sensitivity inorganic element analysis [23]. Historically used for analyzing surface metallic contamination and organic materials in semiconductors and display materials, TOF-SIMS has expanded to include analysis of organic matter distribution and segregation on organic material surfaces [23].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Primary Excitation | Detected Signal | Key Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS [23] | X-rays | Photoelectrons | Quantitative elemental & chemical state analysis; works with organic/inorganic materials | Surface composition, chemical bonding, oxidation states, thin films |

| AES [26] [23] | Electron beam | Auger electrons | High spatial resolution; elemental & some chemical information | Metal/semiconductor surfaces, micro-level foreign substances, thin films |

| TOF-SIMS [23] | Primary ions | Secondary ions | Extreme surface sensitivity; molecular mass information; high sensitivity | Organic material distribution, surface contamination, segregation studies |

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Depth Profiling

Depth profiling represents a powerful extension of surface analysis that enables researchers to measure compositional changes as a function of depth beneath the original surface. This technique involves the controlled removal of material using an ion beam, followed by data collection at each etching step, producing a high-resolution composition profile from the surface to the bulk material [26]. Depth profiling is particularly valuable for studying phenomena like corrosion, surface oxidation, and the chemistry of material interfaces [26].

Two primary approaches are employed for depth profiling. Traditional monatomic ion sources work well for hard materials, while newer gas cluster ion sources enable the analysis of several classes of soft materials that were previously inaccessible to XPS depth profiling [26]. Modern ion sources, such as the differentially pumped caesium ion gun (IG5C), can achieve depth resolution as fine as 2 nanometers, providing exceptional precision for analyzing thin surface layers formed through deposition or corrosion processes [24].

Complementary Surface Analysis Techniques

Several specialized techniques complement the major surface analysis methods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of surface properties:

Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS): By collecting photoelectrons at varying emission angles, this technique enables electron detection from different depths, providing valuable insights into the thickness and composition of ultra-thin films without the need for ion etching [26].

Small-Area XPS (SAXPS): This approach maximizes the detected signal from specific small features on a solid surface (such as particles or surface blemishes) while minimizing contributions from the surrounding area [26].

Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS): Also known as Low-Energy Ion Scattering (LEIS), this highly surface-sensitive technique probes the elemental composition of specifically the first atomic layer of a surface, making it valuable for studying surface segregation and layer growth [26].

Reflected Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (REELS): This technique probes the electronic structure of materials at the surface by measuring energy losses in incident electrons resulting from electronic transitions in the sample, allowing measurement of properties like electronic band gaps [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Handling Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable surface analysis results. Samples must be carefully handled to avoid contamination from fingerprints, dust, or environmental exposure. Solid samples should be mounted using appropriate holders that minimize contact with the analysis area. For insulating samples, charge compensation strategies must be implemented to counteract the accumulation of positive surface charge that significantly impacts XPS spectra [26]. This typically involves supplying electrons from an external source to neutralize the surface charge and maintain the surface in a nearly neutral state [26].

For hydrated materials like hydrogels and biological samples, a specialized protocol involving rapid freezing in an ultrapure environment followed by controlled sublimation of ice layers can preserve the native state while making the sample compatible with UHV conditions [25]. This approach allows researchers to analyze materials that would otherwise be incompatible with vacuum-based techniques.

Standard Analytical Workflow

A comprehensive surface analysis follows a systematic workflow:

Sample Introduction: Transfer the sample into the UHV chamber using a load-lock system to maintain vacuum integrity in the main analysis chamber.

Preliminary Survey: Conduct a broad survey scan (typically 1-20 minutes) to identify all detectable elements present on the surface [25].

High-Resolution Analysis: Perform detailed high-resolution scans (1-15 minutes per region of interest) to reveal chemical state differences with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio, often requiring multiple sweeps of the region [25].

Spatial Analysis: Employ either XPS mapping (serial acquisition) or parallel imaging to understand the distribution of chemistries across a surface, locate contamination boundaries, or examine thickness variations of ultra-thin coatings [26].

Depth Profiling (if required): When subsurface information is needed, initiate depth profiling using ion beam etching with simultaneous analysis, which may require 1-4 hours depending on the depth and number of elements monitored [25].

Data Interpretation: Quantify results using relative sensitivity factors, account for peak overlaps, and interpret chemical states based on binding energy shifts and spectral features.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Equipment and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Tool/Component | Function and Application | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic X-ray Source [25] | Provides focused X-ray excitation for high-resolution XPS analysis | Al Kα (1486.7 eV) or Mg Kα (1253.7 eV); eliminates Bremsstrahlung background |

| Ion Guns for Depth Profiling [24] | Controlled surface etching for depth profile analysis; sputter cleaning | Gas cluster ion sources for soft materials; spot sizes from <30 μm to >1mm |

| Charge Neutralization System [26] | Compensates for surface charging on insulating samples | Low-energy electron flood gun; precise control for stable analysis |

| UHV Analysis Chamber [23] | Maintains pristine surface conditions during analysis | Pressure <10⁻⁷ Pa; minimizes surface contamination and gas interference |

| Electron Energy Analyzer [25] | Measures kinetic energy of emitted electrons with high precision | Hemispherical analyzer for high energy resolution; multi-channel detection |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Analytical Constraints and Challenges

Surface analysis techniques face several important limitations that researchers must consider when designing experiments and interpreting results. Sample degradation during analysis represents a significant concern for certain material classes, particularly polymers, catalysts, highly oxygenated compounds, and fine organics [25]. The degradation mechanism depends on the material's sensitivity to specific X-ray wavelengths, the total radiation dose, surface temperature, and vacuum level. Non-monochromatic X-ray sources produce significant Bremsstrahlung X-rays (1-15 keV) and heat (100-200°C) that can accelerate degradation, while monochromatized sources minimize these effects [25].

The inherent trade-off between spatial resolution, analytical sensitivity, and analysis time presents another important consideration. While XPS offers excellent chemical information, its spatial resolution is limited compared to techniques like AES. Achieving high signal-to-noise ratios for weak signals or low-concentration elements requires extended acquisition times, potentially leading to sample degradation or impractical analysis durations [25].

Detection Limitations and Quantitative Considerations

Detection limits in surface analysis vary significantly depending on the element of interest and the sample matrix. Elements with high photoelectron cross sections (typically heavier elements) generally exhibit better detection limits. However, the background signal level increases with both the atomic number of matrix constituents and binding energy due to secondary emitted electrons [25]. This matrix dependence means that detection limits can range from 1 ppm for favorable cases (such as gold on silicon) to much higher limits for less favorable combinations (such as silicon on gold) [25].

Quantitative precision—the ability to reproduce measurements—depends on multiple factors including instrumental stability, sample homogeneity, and data processing methods. While relative quantification between similar samples typically shows good precision, absolute quantification requires certified standard samples and careful attention to reference materials and measurement conditions [25].

Application in Research and Industry

Surface analysis techniques find application across diverse scientific and industrial fields. In semiconductor manufacturing, these methods help identify minimal contamination that could compromise device performance [23]. In biomedical applications, surface analysis characterizes the chemical properties of medical implants and biomaterials that directly interact with biological systems [25]. Catalysis research relies heavily on surface analysis to understand the chemical states and distribution of active sites on catalyst surfaces [25].

The development of new materials with enhanced surface properties—such as improved corrosion resistance, tailored wetting behavior, or specific biocompatibility—depends fundamentally on the ability to characterize and understand surface chemistry at the nanometer scale. As materials science continues to push toward more complex and functionalized surfaces, the role of sophisticated surface analysis techniques becomes increasingly critical for both fundamental research and industrial application.

The Analyst's Toolkit: Techniques, Applications, and Real-World Case Studies

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) is a quantitative, surface-sensitive analytical technique that measures the elemental composition, empirical formula, and chemical state of elements within the top 1–10 nm of a material [27]. This technical guide details its fundamental principles, methodologies, and applications, framed within the broader context of surface chemical analysis research.

XPS, also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is based on the photoelectric effect [25]. When a solid surface is irradiated with soft X-rays, photons are absorbed by atoms, ejecting core-level electrons called photoelectrons. The kinetic energy (KE) of these ejected electrons is measured by the instrument, and their binding energy (BE) is calculated using the fundamental equation [25]:

- Ebinding = Ephoton - (Ekinetic + ϕ)

where Ebinding is the electron binding energy, Ephoton is the energy of the X-ray photons, and ϕ is the work function of the spectrometer [25]. Since the binding energy is characteristic of each element and its chemical environment, XPS provides both elemental identification and chemical state information [25] [27].

The strong interaction between electrons and matter limits the escape depth of photoelectrons without energy loss, making XPS highly surface-sensitive, typically probing the top 5–10 nm (approximately 50–60 atomic layers) [25] [27]. This surface selectivity, combined with its quantitative capabilities, makes XPS invaluable for understanding surface-driven processes such as corrosion, catalysis, and adhesion [28].

Quantitative Analysis in XPS

The conversion of relative XPS peak intensities into atomic concentrations is the foundation of quantification. For homogeneous bulk materials, accuracy is fundamentally limited by the subtraction of the inelastically scattered electron background and the accurate knowledge of the intrinsic photoelectron signal's spectral distribution [29].

The Quantification Workflow

Quantification relies on correcting raw XPS signal intensities with Relative Sensitivity Factors (RSFs) to calculate atomic percentages [25]. The process can be broken down into several stages, as visualized below.

Relative Sensitivity Factors (RSFs)

There are two primary approaches to determining RSFs:

- Theoretical RSFs (t-RSF): Calculated using photoemission cross-sections (σ) [29].

- Empirical RSFs (e-RSF): Derived from measurements of standard samples [29].

A key perspective in the field is that, when performed correctly, there is no significant disagreement between these two approaches, contradicting earlier claims of serious discrepancies [29].

Accuracy, Precision, and Detection Limits

The quantitative performance of XPS can be summarized as follows:

Table 1: Quantitative Accuracy and Detection Limits in XPS

| Aspect | Typical Performance | Notes and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (Major Peaks) | 90–95% of true value [25] | Applies to strong signals used for atomic percent calculations. |

| Accuracy (Weaker Peaks) | 60–80% of true value [25] | Peaks with 10–20% intensity of the strongest peak. |

| Precision | High [29] | Essential for monitoring small changes in composition or film thickness. |

| Routine Detection Limits | 0.1–1.0 atomic % (1000–10000 ppm) [25] | Varies with element and matrix. |

| Best Detection Limits | ~1 ppm [25] | Achievable under optimal conditions (e.g., high cross-section, low background). |

| Material Dependency | Varies significantly [29] | Best for polymers with first-row elements (±4%); more challenging for transition metal oxides (±20%). |

Quantitative accuracy is influenced by multiple parameters, including signal-to-noise ratio, accuracy of relative sensitivity factors, surface volume homogeneity, and correction for the energy dependence of the electron mean free path [25].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

A range of experimental modalities extends the core XPS technique to address specific analytical challenges.

Small Area XPS (SAXPS) or Selected Area XPS

- Purpose: To analyze small features on a solid surface, such as particles or surface blemishes [30] [27].

- Protocol: The instrument is configured to maximize the detected signal from a specific, small area (down to ~10 µm diameter) while minimizing the contribution from the surrounding region [30] [28].

- Application: Locating and analyzing specific regions of interest before performing detailed spectroscopy or imaging [28].

XPS Imaging

XPS imaging reveals the distribution of chemistries across a surface. There are two primary acquisition methods [30] [27]:

- Serial Acquisition (Mapping): The X-ray beam is scanned across the sample surface, collecting a spectrum at each pixel.

- Parallel Acquisition (Parallel Imaging): The entire field of view is illuminated, and a position-sensitive detector simultaneously collects spatially resolved electrons. This is the preferred mode as it allows faster acquisition and minimizes sample damage [28].

Advanced Imaging Protocol: Quantitative chemical state imaging involves acquiring a multi-spectral data set—a stack of images incremented in energy (e.g., 256 x 256 pixels, 850 energy steps) [28]. Multivariate analytical techniques, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or the Non-linear Iterative Partial Least Squares (NIPALS) algorithm, are then used to reduce noise and the dimensionality of the data, enabling the generation of quantitative chemical state maps [28].

XPS Depth Profiling

- Purpose: To determine the composition as a function of depth from the surface, useful for studying interfaces, thin films, corrosion, and oxidation [30] [27].

- Protocol: Material is controllably sputtered away using an ion beam. The process alternates between brief ion etching cycles and XPS data collection, building a composition profile from the surface to the bulk [30].

- Advanced Development: The use of gas cluster ion sources (e.g., Ar clusters) has dramatically reduced sputtering artifacts, enabling the depth profiling of soft materials (polymers, organics) previously inaccessible to this technique [30] [27].

Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS)

- Purpose: To gain depth composition information non-destructively for ultra-thin films (typically < 10 nm) [30].

- Protocol: XPS spectra are collected at varying electron emission angles. Grazing emission angles are more surface-sensitive, while normal angles probe deeper into the sample [30].

- Application: Determining the thickness and composition of ultra-thin films [30] [27].

Data Processing and Advanced Workflows

The journey from raw data to chemical insight involves a multi-step workflow, particularly for imaging data sets.

This workflow allows for the classification of image pixels based on chemistry, which guides the application of curve-fitting models. The validity of the fit is checked across the entire image using a figure of merit, ensuring robust quantitative results [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Instrumental Components

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Al Kα / Mg Kα X-ray Source | Standard laboratory X-ray sources for generating photoelectrons. Al Kα = 1486.7 eV; Mg Kα = 1253.7 eV [25] [29]. |

| Mono-chromated X-ray Source | Produces a narrow, focused X-ray beam, improving energy resolution and reducing Bremsstrahlung radiation that causes sample damage [25]. |

| Charge Compensation (Flood Gun) | Neutralizes positive charge buildup on electrically insulating samples (e.g., polymers, ceramics) by supplying low-energy electrons, ensuring accurate spectral data [30] [27]. |

| MAGCIS/Dual-Mode Ion Source | Provides both monatomic ions and gas cluster ions for depth profiling, enabling analysis of hard and soft materials on a single instrument [30] [27]. |

| Magnetic Immersion Lens / Spherical Mirror Analyser | Key components in modern instruments for focusing and energy-filtering photoelectrons, enabling high spatial resolution and sensitivity in parallel imaging [28]. |