Strategies for Minimizing Beam Damage in Surface Spectroscopy: A Guide for Reliable Data Collection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on mitigating beam damage during surface spectroscopy, a critical challenge in analyzing beam-sensitive materials, including those relevant to drug development.

Strategies for Minimizing Beam Damage in Surface Spectroscopy: A Guide for Reliable Data Collection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on mitigating beam damage during surface spectroscopy, a critical challenge in analyzing beam-sensitive materials, including those relevant to drug development. It covers the foundational mechanisms of electron and X-ray beam damage, explores advanced low-dose and non-damaging methodologies like aloof beam EELS, details practical optimization protocols for instrument parameters, and discusses validation techniques to confirm data integrity. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to empower professionals to acquire chemically and structurally accurate spectroscopic data from delicate biological and organic specimens.

Understanding Beam Damage: Mechanisms and Impact on Spectroscopic Analysis

FAQs: Fundamental Beam Damage Mechanisms

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms by which electron beams damage sensitive materials?

The two primary classical mechanisms are knock-on displacement and radiolysis. Knock-on displacement results from high-angle elastic scattering between primary electrons and atomic nuclei, which transfers sufficient kinetic energy to displace atoms from their lattice sites if the energy exceeds the material-specific displacement energy (E~d~). This mechanism dominates in conducting materials. In contrast, radiolysis dominates in non-conducting materials and arises from inelastic scattering that creates long-lived electronic excitations. This drives atomic displacements through energy-momentum conversion via thermal vibration or local Coulomb repulsion, leading to permanent bond breakage and reformation [1]. Volume plasmon excitations, which promptly transition into multiple single-electron ionization and excitation events, are identified as a predominant cause of damage in biological and other radiation-sensitive materials [2].

Q2: What is "dark progression" in the context of X-ray damage?

Dark progression refers to the increase or progression of radiation damage that occurs after the X-ray beam has been turned off. This phenomenon means that damage can continue to develop during X-ray-free "dark" periods, which were initially introduced as a potential mitigation strategy. The extent of dark progression is influenced by factors like temperature and the duration of the dark interval. For instance, it has been observed on timescales from 200 to 1200 seconds at temperatures between 180 K and 240 K, but not at cryogenic temperatures (below 180 K) [3].

Q3: Are there non-classical damage mechanisms beyond knock-on and radiolysis?

Yes, recent studies using low-dose electron microscopy have revealed nonclassical beam damage mechanisms. In open-framework materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), these include:

- Reversible Radiolysis: A mechanism involving cascade self-repairing processes that lead to dynamic crystalline-to-amorphous interconversion events, exhibiting a direct dose-rate effect [1].

- Radiolysis-Enhanced Knock-on Displacement: Anisotropic lattice strain resulting from radiolytic structural degradation can facilitate site-specific ligand knockout events, indicating a synergy between the two primary mechanisms [1].

Q4: How does sample temperature influence radiation damage mechanisms?

Temperature plays a critical role. Cryocooling (e.g., below 110 K) is a widely used mitigation strategy as it slows down thermal diffusion and radical-mediated processes. For example, dark progression of global damage is not observed from 25 K to 180 K, but becomes measurable at temperatures of 180 K and above [3]. Lower temperatures also reduce the rate of thermal diffusion of the excitations initiated by the X-ray photon, thereby slowing global sample damage [3].

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Mitigating Beam Damage

Table 1: Symptom Diagnosis and Mitigation Strategies

| Observed Symptom | Potential Underlying Mechanism | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid fading of diffraction spots, amorphization | Radiolysis (dominant in non-conductors) [1] | • Use lower accelerating voltages where possible [1].• Cryo-cool the sample (e.g., to liquid N~2~ temperatures) [3].• Implement low-dose imaging techniques [2] [1]. |

| Atomic vacancies, surface sputtering | Knock-on Displacement (dominant in conductors) [1] | • Use lower primary beam energies below the knock-on threshold [1] [4].• Consider higher kV conditions to mitigate knock-on (note: this may increase radiolysis) [1]. |

| Continued damage progression after beam is off | Dark Progression [3] | • For X-rays, avoid long, unnecessary dark periods during data collection at certain temperatures [3].• Collect data continuously without pauses between frames if possible [3].• Operate at cryogenic temperatures (<180 K) where dark progression is suppressed [3]. |

| Anisotropic shrinkage, pore collapse in frameworks | Nonclassical Reversible Radiolysis [1] | • Control the dose rate [1].• Introduce specific gas atmospheres within the microscope to regulate the self-repairing dynamics [1]. |

| Gas bubble formation in liquid media | Radiolysis in liquids [5] | • Use radiolysis-resistant solvents or scavengers [5].• Model the reaction kinetics and species diffusion using advanced computational workflows [5]. |

Table 2: Critical Dose (D~c~) for Select Beam-Sensitive Materials

This table summarizes the electron dose at which significant damage occurs, guiding exposure budgets. The critical dose (D~c~) is a quantitative measure of a material's vulnerability to radiolytic damage, often defined as the dose where diffraction spot intensity falls to 1/e of its original value [1].

| Material | Material Type | Critical Dose (D~c~) | Primary Damage Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-66(Zr) | Metal-Organic Framework | ~17 e⁻ Å⁻² | Radiolysis | [1] |

| ZIF-8(Zn) | Metal-Organic Framework | ~25 e⁻ Å⁻² | Radiolysis | [1] |

| MIL-101(Cr) | Metal-Organic Framework | ~16 e⁻ Å⁻² | Radiolysis | [1] |

| Biological Molecules | Biological | Limited exposure budget | Volume Plasmon-driven Radiolysis | [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Damage Mitigation

Protocol: Implementing Low-Dose Imaging for Atomic-Scale Studies

Objective: To visualize radiation-induced structural dynamics in beam-sensitive materials without compromising spatial resolution. Materials: Aberration-corrected (S)TEM with a direct electron detector. Workflow: The core of this protocol involves acquiring data at high speed and low signal-to-noise, followed by advanced computational decoding [4].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare and load the beam-sensitive sample (e.g., monolayer MoS~2~, Metal-Organic Frameworks).

- Microscope Setup:

- Use an external beam control system that enables non-raster scanning (e.g., spiral scan paths) to achieve high temporal resolution (up to 100 fps) and reduce peripheral dose [4].

- Set the electron dose rate to a pre-calibrated low-dose condition.

- Data Acquisition:

- Acquire a continuous series of images at high frame rates.

- The low dose per frame results in a low signal-to-noise ratio, which is acceptable for subsequent processing.

- Data Processing and Decoding:

- Process the image series using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN), such as the Ensemble Learning-Iterative Training (ELIT) workflow.

- The model is trained on simulated STEM images of the pristine material structure, including common defects.

- The trained network decodes individual frames to identify atomic positions and defect types with high certainty, reconstructing the structural dynamics [4].

Protocol: Investigating Dark Progression in X-ray Experiments

Objective: To determine whether introducing X-ray-free "dark" periods mitigates or promotes sample damage. Materials: Single crystal or powder sample of a radiation-sensitive material (e.g., [M(COD)Cl]₂ catalysts), synchrotron beamline. Workflow: This protocol compares continuous and discontinuous irradiation patterns [3].

- Baseline Data Collection:

- Collect a reference diffraction dataset (e.g., PXRD) or spectrum (e.g., XPS) from a pristine sample location with a standard, continuous exposure.

- Quantify initial metrics like unit cell parameters, B-factors, or chemical state peaks.

- Discontinuous Irradiation Experiment:

- Move to a new, pristine location on the sample.

- Expose the sample to the X-ray beam using an intermittent pattern: a short period of irradiation (e.g., 1-5 seconds) followed by a programmed "dark" period of no irradiation (e.g., 10-600 seconds).

- Repeat this cycle multiple times, collecting a data frame after each irradiation period.

- Control Experiment:

- On a comparable sample region, collect a dataset using continuous irradiation for a total dose matched to the cumulative dose of the discontinuous experiment.

- Data Analysis:

- Monitor the decay of data quality indicators (e.g., reflection intensity, peak resolution, B-factor increase, chemical shift) as a function of cumulative dose.

- Compare the rate of degradation and final state between the discontinuous and continuous irradiation datasets. A faster degradation in the discontinuous experiment indicates the presence of damaging dark progression [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Role in Experiment | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic Coolant (Liquid N~2~) | Suppresses diffusion of radicals and slows down damage processes like dark progression. | Standard mitigation for biological samples and sensitive materials in EM and X-ray diffraction [3]. |

| AuRaCh Python Tool | Automates the composition and simulation of complex radiolysis reaction networks in homogeneous (0D) scenarios. | Modeling radiolysis in Liquid-Phase EM; predicts species concentration over time [5]. |

| COMSOL Multiphysics | Finite Element software for expanding radiolysis models into complex geometries, incorporating diffusion and convection. | Coupled with AuRaCh for spatially resolved radiolysis modeling in application-near conditions [5]. |

| Direct Electron Detector | Enables high-efficiency imaging at very low electron doses, crucial for capturing data before damage. | Foundational hardware for low-dose EM and high-temporal-resolution studies [1] [4]. |

| Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) | Decodes high-speed, low-signal-to-noise image data to determine atomic positions and track defect dynamics. | Used in the ELIT workflow to analyze beam-induced modifications in 2D materials [4]. |

Advanced Visualization: Beam Damage Mechanisms and Pathways

Understanding the sequence and interplay of damage events is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies. The following diagram synthesizes classical and non-classical mechanisms across multiple timescales.

FAQ: How do I identify knock-on displacement in my samples?

Knock-on displacement can be identified through several observable changes in your sample's structure and composition under the beam.

Key Indicators and Diagnostic Methods:

- Emergence of Nanoscale Features: In metallic alloys like Zircaloy-4, nanoscale precipitates may gradually become visible under prolonged electron beam irradiation, even at energies below the theoretical displacement threshold [6].

- Surface Sputtering and Atomic Restructuring: Direct evidence includes the sputtering of surface atoms and nanoscale atomic restructuring in the matrix, observable via Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) techniques like bright-field imaging and selected area electron diffraction [6].

- Amorphization of Crystalline Structures: Crystalline precipitates can undergo irradiation-induced amorphization, which can be identified by a loss of clarity in diffraction patterns [6].

- Mass Loss and Thickness Reduction: In organic and biological samples, a significant loss of specimen mass (up to 40%) and thickness (up to 50%) can occur at high electron doses (above 10⁶ to 10⁸ e⁻/nm²) [7].

- Elemental Composition Changes: Monitor for specific elemental loss. For instance, oxygen content in organic sections can drop sharply (e.g., from 25% to 9%) at relatively low doses (10⁴ e⁻/nm²), while phosphorus and nitrogen may be more stable at higher doses [7].

FAQ: What are the primary signs of radiolytic breakdown?

Radiolytic breakdown, the dissociation of molecules by ionizing radiation, manifests differently depending on the environment.

Key Indicators and Manifestations:

- In Liquid Media (e.g., Water): Radiolysis produces a complex mixture of radical and molecular species, including hydrated electrons (eₐq⁻), hydroxyl radicals (HO•), hydrogen atoms (H•), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and molecular hydrogen (H₂) [8]. These species can cause:

- In Soft Matter and Polymers: For materials like the Nafion ionomer used in fuel cells, X-ray beams can cause specific damage, altering the chemical states observed in spectroscopy and potentially degrading performance [9].

- During Biological Analysis: In unstained biological sections, mass loss and shrinkage are primary indicators of radiolytic damage [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Mitigating Knock-on Displacement

The following table outlines common symptoms and solutions for knock-on displacement.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution / Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Visible emergence of nanoparticles or precipitates during imaging [6] | High incident electron energy and current density causing atomic displacement [6]. | Reduce electron beam energy and current density. Minimize total irradiation time. Use lower magnification for observation where possible. |

| Sputtering of surface atoms observed in TEM [6] | Direct momentum transfer from electrons to nuclei, especially at surfaces [6]. | Coat the surface with a thin, stable, conductive carbon layer [7]. |

| Amorphization of crystalline phases or precipitates [6] | Accumulation of displacement damage disrupts the long-range crystal order [6]. | Use cryo-holders to cool the specimen, which can reduce atomic mobility and defect migration. |

| Specimen thinning or lateral shrinkage [7] | Knock-on displacement and subsequent loss of mass from the irradiated area. | For quantitative work, apply a dose fractionation approach in tomography to keep the total dose below damaging thresholds [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Radiolytic Breakdown

The following table outlines common symptoms and solutions for radiolytic breakdown.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution / Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Gas bubble formation in liquid cells [5] | Radiolysis of water or solvent producing molecular hydrogen and oxygen [5] [8]. | Use radical scavengers (e.g., formic acid, hydrogen-atom donors) to alter reaction pathways and reduce gas yield [8]. |

| Uncontrolled growth or dissolution of nanoparticles in liquid [5] | Reactions between radiolytic species (e.g., radicals) and the nanoparticle surface [5]. | Model the radiolysis reaction network to predict and control chemical conditions [5]. |

| Damage to sensitive polymers (e.g., ionomers) during XPS [9] | Absorption of X-rays, leading to bond scission within the polymer [9]. | Use a defocused, rastered beam and shorter data acquisition times. Take frequent "snapshots" from fresh sample spots to monitor and minimize cumulative damage [9]. |

| Mass loss and elemental changes in biological samples [7] | Radiolytic cleavage of chemical bonds (e.g., C-O, C-H) leading to volatilization [7]. | Work at cryogenic temperatures to suppress diffusion and volatile product formation. For elemental mapping, work at the lowest possible dose to achieve usable signal-to-noise [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Damage Assessment

Protocol 1: Quantifying Mass Loss and Elemental Composition in Thin Films

This methodology is used to measure radiation damage as a function of electron dose [7].

1. Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Unstained, plastic-embedded biological thin-sections (e.g., mouse thymocytes) | A standard, homogeneous model system for quantifying damage [7]. |

| High-Voltage Transmission Electron Microscope (e.g., 300 kV) | Provides the high-energy electron beam for irradiation and analysis [7]. |

| Energy Filtering TEM (EFTEM) system | Allows for acquisition of elemental maps (e.g., for Phosphorus, Nitrogen) via core-edge imaging [7]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Fiducial markers for tracking drift and aligning images for tomography and thickness measurement [7]. |

2. Procedure

- Specimen Preparation: Prepare unstained, plastic-embedded sections (90-150 nm thick) on bare copper grids. Evaporate a thin (5-10 nm) carbon film onto the sections for stability. Deposit 10 nm colloidal gold nanoparticles on both surfaces as fiducial markers [7].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a series of energy-filtered images and EELS spectra from a specific area while incrementally increasing the total electron dose.

- Mass-Thickness Measurement: Calculate the relative mass-thickness (t/λ) from unfiltered and zero-loss filtered images using the formula: ( t/λ = \ln(I{unfilt}/I{zero}) ), where ( I ) is the image intensity [7].

- Absolute Thickness Measurement: Reconstruct bright-field tomograms from tilt series acquired at different doses. Use the known positions of gold markers on the top and bottom surfaces to measure absolute thickness changes [7].

- Elemental Quantification: Acquire pre- and post-edge images for elements of interest (e.g., P, N). Use validated background modeling to subtract the underlying spectral background and calculate net elemental signals as a function of dose [7].

Protocol 2: Operando XPS Analysis of a Composite Electrode with Beam Damage Mitigation

This protocol details the study of a working electrolyzer interface while actively managing X-ray beam damage [9].

1. Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) | The composite electrode of interest, typically a catalyst-coated membrane [9]. |

| Tender X-rays (2-6 keV) | Higher energy photons produce high-energy photoelectrons that can escape through a thin liquid layer and vapor environment [9]. |

| AP-XPS System with "Dip-and-Pull" Capability | Allows for the creation of a thin, continuous liquid layer on the sample surface at ~20 Torr pressure, mimicking operando conditions [9]. |

| Control Samples (Ir foil, IrO₂ powder, Nafion ionomer) | Assist in the accurate identification of chemical states in the complex MEA spectrum [9]. |

2. Procedure

- Cell Design and Humidification: Use a two-electrode cell and establish a humid environment (~20 Torr, 100% relative humidity) to create a continuous liquid water layer on the MEA surface [9].

- Beam Damage Assessment: First, expose a fresh sample spot to the X-ray beam while collecting consecutive spectra. Monitor for changes in chemical states (e.g., the carbon spectrum of the Nafion ionomer) to identify the onset of damage [9].

- Mitigated Data Acquisition: Once a safe exposure time is known, collect data using a "snapshot" approach. Move to a fresh, unexposed spot on the sample for each new measurement or potentiostatic hold to avoid cumulative damage [9].

- Data Correlation: Correlate the chemical information from XPS with the electrochemical response (current density) of the cell to ensure the analyzed spot is electrochemically relevant [9].

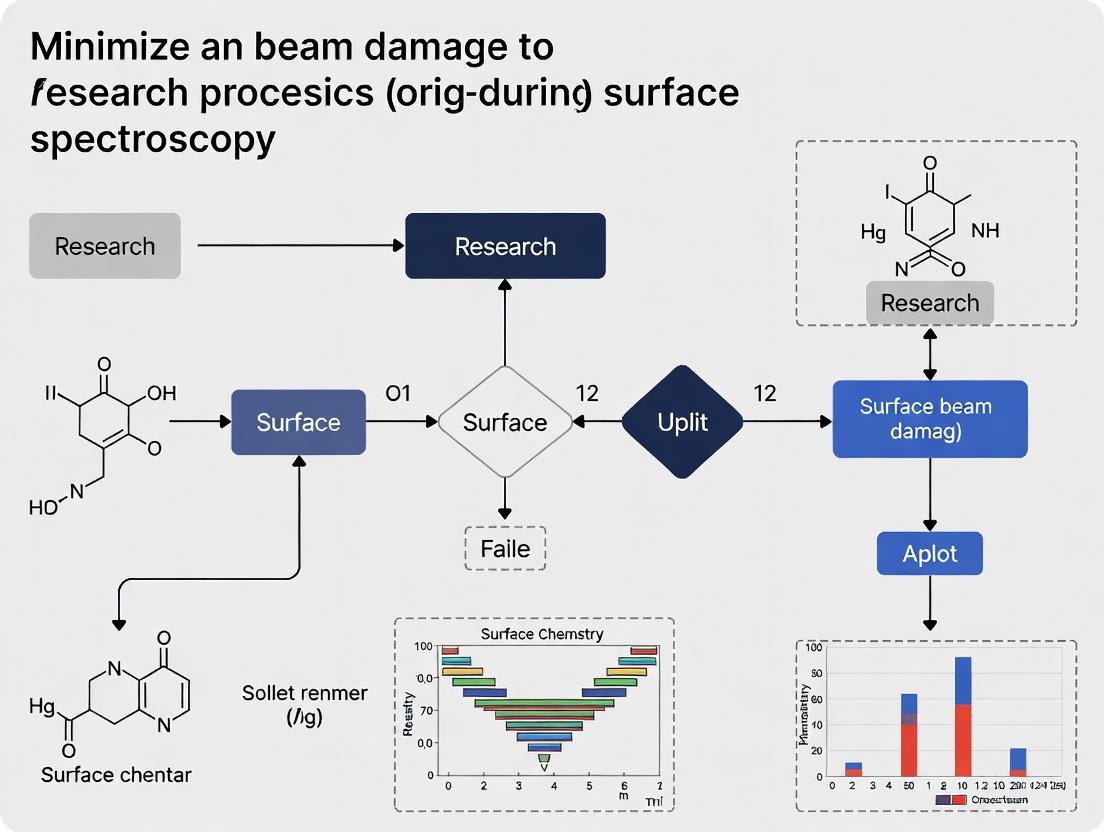

Visualization of Damage Mechanisms and Mitigation

Diagram 1: Knock-on Displacement and Radiolysis Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Proactive Beam Damage Mitigation Workflow

FAQs: Understanding and Mitigating Nonclassical Beam Damage

Q1: What are nonclassical beam damage mechanisms, and how do they differ from classical ones?

Classical radiation damage mechanisms in electron microscopy are primarily knock-on displacement (atomic displacement via elastic scattering) and radiolysis (atomic displacement via inelastic scattering leading to bond breakage) [10]. Nonclassical mechanisms extend this framework. They include phenomena like reversible radiolysis, which involves a cascade self-repairing process leading to dynamic crystalline-to-amorphous interconversion, and radiolysis-enhanced knock-on displacement, where radiolytic structural degradation facilitates site-specific atomic knockout [10]. These are dynamic and synergistic, unlike the often permanent damage described by classical models.

Q2: I am working with a beam-sensitive Metal-Organic Framework (MOF). What specific damage symptoms should I look for?

When conducting surface spectroscopy on sensitive materials like MOFs, you may observe [10]:

- Anisotropic Volumetric Shrinkage: The crystal undergoes non-uniform shrinkage due to the formation of stripe-like amorphized domains with collapsed structures and diminished porosity.

- Dynamic Crystalline-Amorphous Interconversion: Fluctuations in local structure due to the competition between radiolytic bond breaking and self-repair processes.

- Site-Specific Ligand Knockout: Specific molecular ligand groups are selectively ejected from the structure, driven by anisotropic lattice strain from radiolysis.

Q3: What experimental strategies can I use to minimize this damage during analysis?

The cornerstone of modern beam-sensitive material analysis is low-dose electron microscopy [10]. Furthermore, you can:

- Control the Electron Dose Rate: The reversible radiolysis mechanism exhibits a direct dose-rate effect, so modulating this parameter is crucial [10].

- Introduce a Gas Atmosphere: Introducing a specific gas atmosphere within the microscope column can be a strategy to regulate the reversible radiolysis process and monitor structural dynamics [10].

- Use Cryogenic Conditions: This is a standard technique to mitigate radiolytic damage [10].

- Use Lower Accelerating Voltages: This helps to mitigate knock-on displacement damage [10].

Q4: How can I quantitatively measure the radiation vulnerability of my material?

The critical dose (Dc) is a key quantitative metric. It is analogous to a half-life in radioactive decay and can be derived by fitting the exponential decay of intensities in electron diffraction (ED) dose series [10]. However, Dc alone is insufficient because [10]:

- It can be influenced by ill-defined illumination conditions and dose-rate effects.

- It indicates a loss of structural order but does not identify the specific real-space structural damage.

- It struggles to discern complex damage forms beyond simple amorphization. Real-space visualization via low-dose EM is needed for a complete picture.

Quantitative Data on Beam Damage

Table 1: Critical Dose (Dc) Values for Selected Beam-Sensitive Materials

| Material | Material Type | Critical Dose (Dc) / Approximate Tolerance | Primary Damage Mechanism | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-66(Zr) [10] | Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) | ~17 e⁻ Å⁻² (high-order reflection fading) | Radiolysis | Electron Diffraction (ED) |

| ZIF-8(Zn) [10] | Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) | ~25 e⁻ Å⁻² (crystallinity loss) | Radiolysis | Electron Diffraction (ED) |

| MIL-101(Cr) [10] | Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) | ~16 e⁻ Å⁻² | Radiolysis | Material withstands this dose |

| Single-Layer Graphene [10] | 2D Material | Not Applicable (See Table 2) | Knock-on Displacement | Direct atom counting in HRTEM |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Knock-on Displacement Cross-Section Modeling

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Consideration in Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement Energy | Ed | Energy threshold for atomic displacement at a lattice site. | Site-specific; varies from tens of eV (lattice sites) to <1 eV (surface adatoms) [10]. |

| Knock-on Cross-Section | σK | Probability of knock-on displacement event. | Integrated from differential elastic cross-section; model includes screening effects and vibration [10]. |

| Differential Elastic Cross-Section | σe | - | Derived from atom models (e.g., Wentzel model) considering screening effects [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Damage Pathways

Protocol: Visualizing Radiation-Induced Structural Dynamics via Low-Dose EM

This protocol is used for real-space visualization of beam damage, as performed on UiO-66(Hf) [10].

1. Principle: Integrate direct electron detectors and low-dose imaging to capture structural dynamics while maintaining high spatial resolution, enabling the observation of nonclassical damage mechanisms.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) equipped with a direct electron detector.

- Low-dose imaging software and beam blanking system.

- Specimen of beam-sensitive material (e.g., UiO-66(Hf) crystals).

- Specimen holder.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Specimen Preparation. Disperse powder onto a TEM grid using a method that ensures minimal amorphous contamination.

- Step 2: Low-Dose Setup. Navigate to a region of interest using a very low-intensity beam. Set the image acquisition area to be exposed only during data capture.

- Step 3: Image Series Acquisition. Acquire a time-resolved series of images or a dose series under controlled illumination conditions. The cumulative electron dose must be carefully monitored and kept as low as possible.

- Step 4: Data Analysis. Analyze the image series for:

- Morphological changes (shrinkage, bubble formation).

- Loss of crystallinity (fading of lattice fringes).

- Specific molecular-level events (ligand displacement).

4. Expected Outcome: Direct observation of damage events like anisotropic shrinkage, amorphous domain formation, and site-specific knockout.

Protocol: Regulating Reversible Radiolysis with Gas Atmosphere

This protocol outlines a strategy proposed to influence the self-repairing pathway [10].

1. Principle: Introducing a specific gas atmosphere into the microscope column can interact with the temporary defects created by radiolysis, potentially altering the kinetics of the cascade self-repairing process and the dynamic crystalline-to-amorphous interconversion.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- TEM equipped with an environmental cell (E-cell) or gas injection system.

- High-purity gas source (specific gas type is material-dependent and requires research).

- Standard low-dose EM setup.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Baseline Measurement. Perform the low-dose EM protocol (3.1) under high vacuum to establish the material's baseline damage behavior.

- Step 2: Gas Introduction. Introduce a controlled, low pressure of a specific gas (e.g., an inert gas or a mild oxidizing/reducing agent) into the E-cell.

- Step 3: In-Situ Monitoring. Repeat the low-dose EM acquisition under identical dose conditions but within the gas atmosphere.

- Step 4: Comparative Analysis. Compare the structural dynamics and critical dose metrics (Dc) between the vacuum and gas environment conditions.

4. Expected Outcome: A measurable change in the rate of radiolytic damage or the stability of the structure, indicating a modulation of the reversible radiolysis pathway.

Mechanisms and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Beam Damage Pathways in Sensitive Materials.

Diagram 2: Low-Dose EM Workflow for Damage Analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for Beam Damage Studies

| Item | Function / Role in Research | Example / Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Electron Detector | Enables high-resolution, low-dose imaging by directly capturing electrons with high efficiency [10]. | - |

| Low-Dose Imaging Software | Controls the electron beam, limiting exposure to the area of interest only during data acquisition to minimize pre-characterization damage [10]. | - |

| Environmental Cell (E-Cell) | A specialized sample holder that allows the introduction of gases or liquids around the sample, used to study damage regulation via atmosphere [10]. | - |

| Cryogenic Sample Holder | Cools the specimen to very low temperatures (e.g., liquid N2), a standard method for mitigating radiolysis damage by reducing atom mobility [10]. | - |

| Ab Initio Simulation Software | Computational modeling of radiation-induced structural dynamics to predict damage pathways and verify experimental observations at the atomic level [10]. | - |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Model beam-sensitive materials for studying nonclassical damage pathways due to their open-framework structures [10]. | UiO-66(Hf), ZIF-8, MIL-101 |

FAQs: Understanding Beam Damage in Spectroscopy

What are the primary symptoms of beam damage in spectroscopic analysis? Beam damage manifests through several key symptoms that degrade data quality and compromise material integrity. These include the appearance of non-native spectral features (artifacts), a measurable reduction in sample mass (mass loss), and the transformation of a crystalline structure into a disordered, non-crystalline state (amorphization). In electron microscopy, the fading of Bragg spots and diffuse scattering rings in electron diffraction series is a direct measurable symptom of radiation-induced amorphization [1].

What are the fundamental physical mechanisms that cause this damage? The two primary classical mechanisms are knock-on displacement and radiolysis. Knock-on displacement results from high-angle elastic scattering between primary electrons and atomic nuclei, which causes atomic displacement if the transferred energy exceeds the material's displacement energy. Radiolysis (ionization) arises from inelastic scattering that creates long-lived electronic excitations, leading to the breaking and reformation of chemical bonds. Radiolysis typically dominates in non-conducting materials [1].

How can I distinguish between sample-derived signals and damage-induced artifacts? Damage-induced artifacts often exhibit specific characteristics. For instance, in Raman spectroscopy, cosmic ray spikes are sharp, single-pixel events that must be algorithmically removed during data preprocessing [11]. In FT-IR spectroscopy, a contaminated ATR crystal can cause strange negative peaks, which are resolved by cleaning the crystal and taking a fresh background scan [12]. Consistent, non-reproducible features that intensify with prolonged beam exposure are likely artifacts.

Why is amorphization a critical concern in material analysis? Amorphization fundamentally alters a material's properties. For example, when single-layer amorphous carbon is synthesized, its bond angles span 90°–150° compared to the rigid 120° in crystalline graphene, and its bond lengths vary from 0.9–1.8 Å. This results in electronic properties that can differ by nine orders of magnitude depending on the degree of disorder, directly impacting interpretations of material behavior [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Damage

Symptom: Unusual Peaks or Spectral Features (Artifacts)

- Potential Cause 1: Instrument vibration or contamination.

- Solution: Ensure the spectrometer is on a stable, vibration-free base, isolated from nearby pumps or lab activity. For FT-IR, regularly clean ATR crystals and take fresh background scans [12].

- Potential Cause 2: Cosmic ray strikes (primarily in Raman).

- Solution: Implement a data preprocessing step with an algorithm specifically designed for cosmic ray removal [11].

- Potential Cause 3: Surface chemistry not representative of the bulk.

- Solution: For materials like polymers, collect spectra from both the surface and a freshly cut interior to check for surface oxidation or additives that may be more susceptible to beam damage [12].

Symptom: Mass Loss or Signal Attenuation

- Potential Cause 1: Radiolytic sputtering or desorption.

- Solution: Reduce the electron dose or beam current. For single-particle mass spectrometry, using a two-step desorption-ionization process with a lower-energy infrared laser for desorption can minimize fragmentation and mass loss compared to a single-step, high-energy process [14].

- Potential Cause 2: Knock-on displacement at surfaces or defects.

- Solution: Lower the accelerating voltage of the electron beam if possible, as the knock-on cross-section has a sharp onset at an energy threshold [1].

Symptom: Loss of Crystallinity (Amorphization)

- Potential Cause: Radiolytic damage breaking chemical bonds.

- Solution: Implement low-dose techniques. In electron microscopy, this enables real-space imaging of radiation-induced structural dynamics in beam-sensitive materials like Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) while maintaining high spatial resolution [1]. For lasers, consider using a higher repetition rate with lower pulse energy where feasible.

Quantitative Data on Beam Damage Phenomena

The following table summarizes critical dose thresholds and damage characteristics for different materials and techniques, highlighting their vulnerability.

Table 1: Quantitative Damage Thresholds and Characteristics in Different Materials

| Material / Technique | Damage Phenomenon | Critical Dose / Threshold | Observed Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-66(Zr) MOF [1] | Radiolytic Amorphization | ~17 e⁻ Å⁻² (onset of diffraction fading) | Loss of structural order, anisotropic volumetric shrinkage, and pore collapse. |

| MIL-101(Cr) MOF [1] | Radiolytic Damage | ~16 e⁻ Å⁻² (withstandable dose) | General structural degradation. |

| ZIF-8(Zn) MOF [1] | Radiolytic Damage | ~25 e⁻ Å⁻² (crystallinity loss) | Rapid loss of crystallinity. |

| Single-Layer Graphene [1] | Knock-on Displacement | Threshold energy for atomic ejection | Directly observable ejection of atoms from the lattice. |

| Monolayer Amorphous Carbon [13] | Structural Disorder | Synthesis temperature dependent | Electrical conductivity varies by nine orders of magnitude with different ring statistics (e.g., 86% vs 45% hexagons). |

| Raman Spectroscopy [11] | Fluorescence Overlap | Background 2-3 orders more intense than Raman signal | Obscured Raman bands, requiring baseline correction before normalization. |

Experimental Protocols for Damage Mitigation

Protocol 1: Low-Dose Electron Microscopy for Beam-Sensitive Materials

Purpose: To enable structural elucidation of highly beam-sensitive materials like MOFs with minimal damage [1].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a thin, dispersed sample on a suitable TEM grid.

- Instrument Setup: Use a microscope equipped with a direct electron detector.

- Area Selection: Locate a region of interest at low magnification and low beam intensity.

- Data Acquisition: Switch to a pre-exposed area adjacent to the region of interest for focusing and astigmatism correction. Acquire the final image or diffraction pattern at the desired high magnification with a total electron dose kept below the material's critical dose (Dc), often as low as 16-25 e⁻ Å⁻² for MOFs [1].

- Data Processing: Integrate and analyze the captured images or diffraction series to monitor fading or structural dynamics.

Protocol 2: Two-Step Laser Desorption/Ionization (LD-REMPI-LDI) in SPMS

Purpose: To detect aromatic hydrocarbons and refractory components in single particles with reduced fragmentation and matrix effects [14].

- Particle Introduction: Aerodynamically focus and size particles into the instrument's vacuum.

- Laser Desorption (LD): Upon particle detection, trigger a pulsed infrared laser (e.g., CO₂ at 10.6 µm or solid-state Er:YAG at 3 µm) to vaporize organic material from the particle. The Er:YAG laser offers a compact, maintenance-free alternative [14].

- Ionization & Residue Analysis: Immediately after desorption, fire a UV laser pulse (e.g., 266 nm) through the resulting gas plume. This pulse performs Resonance-Enhanced Multi-Photon Ionization (REMPI) for selective, soft ionization of aromatic compounds like PAHs. The same pulse also hits the remaining particle residue, generating ions via Laser Desorption/Ionization (LDI) for inorganic component analysis [14].

- Data Collection: Detect the resulting positive and negative ions using a bipolar time-of-flight mass spectrometer.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms of electron beam-induced damage and their interrelationships, culminating in the observed experimental consequences.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials and reagents used in experiments featured in this guide, along with their specific functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Damage Mitigation Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Er:YAG Solid-State Laser [14] | Compact, maintenance-free infrared laser for laser desorption in two-step SPMS. | Prototype laser (3 µm, 200 µs pulses) used as an alternative to CO₂ lasers for desorbing organics from particles [14]. |

| UiO-66(Hf) MOF [1] | A model, beam-sensitive open-framework material for studying radiolysis damage mechanisms. | Used to observe non-classical mechanisms like reversible radiolysis and anisotropic shrinkage [1]. |

| 4-Acetamidophenol [11] | Wavenumber standard for calibrating Raman spectrometers. | Provides multiple peaks across a wide wavenumber region to construct a stable and accurate wavenumber axis, preventing drift-related artifacts [11]. |

| Diesel Soot & Wood Ash Particles [14] | Laboratory-generated model particles containing PAHs for SPMS method development. | Used to test and compare the performance of LD-REMPI-LDI techniques with different IR lasers [14]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) / BSA [15] | Additives to running buffers to minimize non-specific binding in surface-based techniques like SPR. | Reduces analyte binding to the sensor surface itself, improving data reliability [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the common signs that my material is beam-sensitive during electron microscopy? Beam-sensitive materials often show clear signs of degradation, including:

- Loss of crystallinity: Diffraction patterns become diffuse or disappear entirely [16].

- Formation of bubbles and voids: Observable in the material's subsurface or bulk [17].

- Carbon deposition: Growth of carbonaceous structures, like nanopillars, on the surface [17].

- Mass loss and structural collapse: Particularly in porous materials like MOFs and COFs [18].

Q2: What are the primary mechanisms causing electron beam damage? The main damage mechanisms are:

- Radiolysis: Breaking of chemical bonds due to electron-electron interactions. This is often the dominant mechanism for organic and hybrid materials [18].

- Knock-on damage: Physical displacement of atoms caused by direct electron-nucleus collisions [18].

- Heating: Localized temperature rise due to energy deposition, especially problematic in materials with poor thermal conductivity [18].

Q3: How can I minimize beam damage when analyzing a sensitive MOF, like ZIF-8? A successful protocol for ZIF-8 involves several key strategies [16] [19]:

- Use cryo-conditions: Cool the sample with liquid nitrogen to reduce damage.

- Apply low-dose techniques: Use total exposures as low as 0.02 e⁻/Ų per frame and cumulative doses below 1 e⁻/Ų.

- Utilize direct electron detectors: These provide a much higher signal-to-noise ratio at low doses.

- Consider Focused Ion Beam (FIB) milling: Create thin lamellas (e.g., ~150 nm thick) to allow for lower-dose, higher-resolution (e.g., 0.59 Å) data collection.

Q4: My biological sample changed after placing it in the vacuum for analysis. What happened? Biological surfaces are dynamic and can rearrange when moved from their native (e.g., aqueous) environment to the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) required for techniques like XPS or SIMS. A surface that was enriched with hydrophilic components in water may rearrange to expose hydrophobic components in a vacuum. Furthermore, proteins can denature and unfold [20].

Q5: Does beam damage only occur with electron beams? No. While electron beam damage is frequently discussed, high-intensity X-ray beams can also cause significant damage, particularly in operando studies on materials like battery electrodes. This damage is often chemistry-specific [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Rapid Loss of Crystallinity During Electron Diffraction

Symptoms: Sharp diffraction spots fade quickly, becoming a diffuse halo or disappearing entirely during data collection.

Solutions:

- Immediately reduce the electron dose.

- Lower the beam current or use a larger spot size.

- Use a dedicated low-dose data collection protocol, such as MicroED, which uses ultra-low dose rates (e.g., ~0.02 e⁻/Ų/frame) and continuous sample rotation [16].

- Cool your sample. Prepare and analyze the sample at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., using liquid nitrogen) to mitigate radiolytic damage [16] [18].

- Use a faster detector. Switch to a direct electron detector (DED) which has a higher detection quantum efficiency, allowing you to collect usable data at lower doses [18].

Problem 2: Surface Contamination and Hydrocarbon Deposition

Symptoms: Unusual carbonaceous structures (like nanopillars) grow on the surface, or EDS analysis shows a persistent carbon signal that obscures the sample's true composition [17].

Solutions:

- Improve sample handling and preparation.

- Never touch the analysis surface with anything (including tweezers).

- Use gloves and clean, non-plasticizer-leaching containers (e.g., tissue culture polystyrene).

- Avoid introducing contaminants from solvents [20].

- Use a plasma cleaner to clean the sample surface in the vacuum chamber immediately before analysis.

- Verify your sample is stable under the beam by taking a time-series of images or spectra at low dose to monitor the buildup of contamination.

Problem 3: Inaccurate Chemical Analysis via EDS in Beam-Sensitive Materials

Symptoms: EDS spectra change during acquisition, or the quantified elemental composition does not match expected values.

Solutions:

- Acknowledge beam-induced alteration. Be aware that the electron beam can decompose the sample (e.g., forming Au nanoparticles from AuCl₃) and deposit carbon, fundamentally changing the chemistry you are trying to measure [17].

- Find the narrow operating window. Systematically vary the accelerating voltage and exposure time to find a combination that provides a sufficient X-ray signal while minimizing visible damage. Lower voltages (1-5 kV) may sometimes be beneficial [17].

- Correlate with other techniques. Use a multi-technique approach. For example, combine low-dose TEM or electron diffraction with your EDS analysis to confirm the crystalline structure was preserved during measurement [20].

Quantitative Data on Beam Sensitivity

The table below summarizes key parameters and damage thresholds for different material classes.

Table 1: Beam Damage Characteristics and Mitigation Strategies for Different Materials

| Material Class | Primary Damage Mechanism | Key Sensitive Components | Example Low-Dose Protocol | Achievable Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [16] [18] | Radiolysis | Organic linkers, coordination bonds | MicroED at cryo-temperature, total dose < 1 e⁻/Ų [16] | 0.87 Å (ZIF-8) [16] |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) [18] | Radiolysis | Covalent organic bonds | Low-dose TEM with iDPC-STEM [18] | Atomic-level [18] |

| Biological Materials [20] | Radiolysis, Denaturation | Proteins, lipids, hydrated surfaces | Cryo-fixation, analysis in hydrated state or with minimal air exposure [20] | Varies with technique |

| Battery Electrodes (in operando) [21] | X-ray Radiolysis/Hindrance | Electrolyte, active materials (chemistry-specific) | Intermittent exposure at higher energies (e.g., 25-35 keV) [21] | N/A (Powder Diffraction) |

Table 2: Effect of MicroED and Cryo-FIB on Data Quality for ZIF-8 [16] [19]

| Sample Preparation Method | Data Collection Method | Total Electron Dose | Achieved Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct deposition of nanocrystals | MicroED | ~1 e⁻/Ų | 0.87 Å |

| Cryo-FIB milling of a thin lamella | MicroED with energy filter & direct electron detector | 0.64 e⁻/Ų | 0.59 Å |

Experimental Workflows for Beam-Sensitive Material Analysis

The following diagram outlines a general workflow for the preparation and analysis of beam-sensitive materials, integrating key steps to minimize damage.

Low-Damage Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Beam-Sensitive Material Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Cryogen (Liquid Nitrogen / Ethane) | Cryo-fixation of samples to reduce atomic mobility and radiolytic damage during TEM analysis [16] [18]. | Rapid cooling is essential to form vitreous (non-crystalline) ice in hydrated samples. |

| Holey Carbon Grids | Support for nano- and micro-crystals in transmission electron microscopy [16]. | The grid material itself should be clean and not react with the sample. |

| Methanol / Ethanol (High Purity) | Solvent for creating colloidal suspensions of microcrystalline materials (e.g., ZIF-8) for grid deposition [16]. | High purity is critical to prevent introduction of surface contaminants that can obscure analysis [20]. |

| Tissue Culture Polystyrene | Preferred container for storage and shipping of prepared samples due to low risk of introducing contaminants like plasticizers [20]. | Always verify containers are contamination-free before use. |

| Direct Electron Detector (DED) | Advanced camera for electron microscopy that provides a much higher signal-to-noise ratio at very low electron doses [18]. | This is a key hardware innovation that enables atomic-resolution imaging of beam-sensitive materials. |

Advanced Techniques for Damage-Free Spectroscopy and Imaging

Low-Dose Electron Microscopy (LDEM) is an essential set of techniques designed to minimize electron beam-induced damage during the imaging of radiation-sensitive specimens. The fundamental principle involves using a minimized electron exposure (dose) that is sufficient to generate a usable signal for imaging while being low enough to preserve the native structure of the sample. This approach is critical for fields such as structural biology and materials science, where high-resolution information must be extracted from specimens that are highly vulnerable to radiolysis and knock-on displacement [1] [2].

Radiation damage arises primarily through two mechanisms: radiolysis (ionization), which dominates in non-conducting materials like biological samples and soft materials, and knock-on displacement, where direct momentum transfer from electrons to nuclei displaces atoms from their lattice sites [1]. For sensitive materials, radiolysis imposes a strictly limited "budget" of electron exposure, making dose-efficient imaging paramount [2]. The emergence of direct electron detectors and sophisticated low-dose imaging protocols has enabled the real-space visualization of structural dynamics in even the most beam-sensitive materials, such as Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), opening up new possibilities for their characterization [1].

Technical FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What are the most common symptoms of excessive electron dose during my experiment? Excessive electron dose manifests through specific, observable symptoms:

- Gradual Fading of Diffraction Spots: In crystalline materials, the loss of crystallinity due to radiolytic damage causes Bragg spots in electron diffraction (ED) series to fade [1].

- Mass Loss and Compositional Variation: Tracking with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) series may show a reduction in mass or changes in sample composition [1].

- Visual Degradation in Real-Space: In real-space imaging, you may observe volumetric shrinkage, amorphization of crystalline domains, or the specific "knockout" of lighter ligand groups in framework materials [1].

Q2: My images have unacceptably low signal-to-noise. How can I improve this without increasing dose? Improving signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) without raising the dose is a key skill in LDEM.

- Optimize Your Detector: Use a direct electron detector, which typically has a higher Detective Quantum Efficiency (DQE) than traditional film or CCD cameras, capturing more information from each electron [1] [22].

- Leverage Frame Averaging and Motion Correction: Collect data as a movie of many short-exposure frames. Subsequent computational alignment and averaging of these frames can correct for sample drift and instrument instability, significantly boosting the effective SNR [22].

- Fine-Tune Defocus for Contrast: Phase contrast, generated by applying a mild defocus, is crucial for visualizing features. An optimal defocus (typically between -0.5 μm and -2.0 μm for cryo-EM) balances the need for sufficient low-resolution contrast to identify particles with the retention of high-resolution information [22].

Q3: I am consistently observing beam-induced sample drift. What steps can I take to mitigate this? Beam-induced sample drift can ruin high-resolution data collection.

- Ensure Stable Cryo-Conditions: If working at cryogenic temperatures, verify that your sample is properly thermally equilibrated in the microscope. Instability can cause continuous drift.

- Use a Low-Dose Search Mode: Always use the microscope's low-dose workflow. When searching for areas of interest, use a high-defocus, very low-dose "search" mode to navigate without exposing your target area to damaging radiation [22].

- Allow for Stage Settling Time: After moving the stage, program a relaxation delay (e.g., 1-2 seconds) to allow for mechanical vibrations to dampen before beginning the focus and record steps [22].

Low-Dose Workflow and Experimental Design

A successful low-dose experiment hinges on a meticulously planned workflow that minimizes the electron dose at every stage, from initial screening to final data acquisition.

The core principle of this workflow is the physical separation of the focusing step from the data recording area. This prevents the precious region of interest from being exposed to a high dose during the focusing procedure, which is essential for preserving high-resolution information [22].

Optimizing Key Acquisition Parameters

The table below summarizes critical parameters and their optimization strategy for low-dose work.

Table 1: Key User-Defined Parameters for Low-Dose Data Collection

| Parameter | Typical Range | Optimization Consideration | Primary Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Electron Dose [22] | 40-60 e⁻/Ų (Cryo-EM) | Balance between sufficient image signal and minimization of radiation damage. | High Dose: Better SNR vs. Increased Damage.Low Dose: Reduced Damage vs. Poorer SNR. |

| Pixel Size (Magnification) [22] | Variable (Å/pixel) | Chosen based on desired resolution. Pixel size should be at least 2x smaller than the target resolution. | High Mag: Finer pixel size vs. Fewer particles per image.Low Mag: More particles vs. Coarser pixel size. |

| Defocus [22] | -0.5 μm to -2.0 μm | Lower defocus retains high-resolution info but reduces contrast. Higher defocus boosts contrast but attenuates high-resolution signal. | Close to Focus: High-resolution signal vs. Low contrast.Far from Focus: High contrast vs. Attenuated high-res signal. |

| Hole Targeting Strategy [22] | Conventional vs. Beam-Shift | Conventional (one hole per stage move) gives pristine optics. Multi-hole beam-shift vastly increases throughput with a minor potential resolution cost. | Conventional: Best resolution vs. Low throughput.Beam-Shift: High throughput vs. Potential coma aberrations. |

Beam Damage Mechanisms and Advanced Mitigation

Understanding the physical origins of beam damage is key to developing effective mitigation strategies. Damage occurs across multiple time and length scales.

Classical Mechanisms:

- Radiolysis is caused by inelastic scattering, where electrons excite the specimen's electrons, leading to broken chemical bonds and atomic displacement. It is the predominant damage mechanism in insulating, beam-sensitive materials like biological samples and MOFs [1] [2]. Volume plasmon excitations are a primary initiator of this damage cascade [2].

- Knock-on Displacement results from elastic scattering, where incident electrons directly transfer enough kinetic energy to an atomic nucleus to displace it from its lattice site. This mechanism is more dominant in conducting materials and at higher accelerating voltages [1].

Emerging/Non-Classical Mechanisms: Recent studies using low-dose EM have revealed more complex damage pathways:

- Reversible Radiolysis: In some framework materials, a cascade self-repairing process can occur, leading to dynamic crystalline-to-amorphous interconversion instead of permanent damage [1].

- Radiolysis-Enhanced Knock-on Displacement: Radiolytic structural degradation can induce anisotropic lattice strain, which in turn facilitates site-specific knockout events that would not occur via knock-on displacement alone [1].

Advanced Low-Dose Techniques

Table 2: Advanced Methodologies for Minimizing Beam Damage

| Technique | Underlying Principle | Key Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo-Conditions [23] | Rapid vitrification of hydrated samples to form amorphous ice and reduce atomic mobility. | Preservation of native structure in biological molecules (proteins, viruses) and beam-sensitive soft materials. | Requires specialized plunge-freezing apparatus and constant liquid nitrogen cooling during imaging. |

| Low kV Imaging | Reducing the accelerating voltage of the electron beam to lower the kinetic energy of electrons. | Mitigating knock-on damage in conductive or semi-conductive materials (e.g., 2D materials, polymers). | Can reduce beam penetration and increase the cross-section for inelastic scattering (radiolysis). |

| Dynamic Sampling (MOADS) [24] | An algorithmic approach that autonomously decides the next most informative location to measure during spectrum imaging. | Accelerating analytical mapping (EELS, EDS) and reducing total area dose for beam-sensitive materials. | Implementable as software on conventional STEMs; can reduce acquisition time/dose by over an order of magnitude. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Equipment and Software Solutions for Low-Dose EM

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Products / System Types |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo Transmission EM [23] | High-resolution structure determination of vitrified biological molecules at cryogenic temperatures. | Thermo Fisher Scientific Krios, Glacios, Tundra [25]. |

| Direct Electron Detector | Captures electrons with high Detective Quantum Efficiency (DQE), enabling high-resolution imaging at low doses. | Gatan K2, K3; Falcon series (Thermo Fisher) [1]. |

| Plasma / Cryo-FIB-SEM | For large-volume sample preparation and lamella milling prior to TEM imaging, including for cryo-samples. | Thermo Fisher Scientific Helios Hydra PFIB, Arctis Cryo-Plasma-FIB, Aquilos 2 Cryo-FIB [25]. |

| Low-Dose Automation Software | Software to automate and control the low-dose workflow, including beam-blanking, stage movement, and data acquisition. | Thermo Scientific Velox, TFS Maps, SerialEM, Gatan Digital Micrograph (DM) [22] [25]. |

| Algorithmic Sampling Software | Software add-ons that enable dynamic sampling to drastically reduce total acquisition dose and time for spectral mapping. | Multi-Objective Autonomous Dynamic Sampling (MOADS) for Gatan DM [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of electron beam damage during surface analysis, and how do aloof beam and low-angle polishing address them? Electron beam damage primarily occurs through two mechanisms: knock-on displacement (physical displacement of atoms via elastic scattering) and radiolysis (breaking of chemical bonds via inelastic scattering, often dominant in non-conducting materials) [1]. Aloof beam Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) addresses this by positioning the electron beam several nanometers away from the sample surface. This setup eliminates knock-on damage and significantly reduces ionization damage because the beam does not directly strike the specimen [26]. Low-angle polishing with a Focused Ion Beam (FIB) minimizes surface damage by using a shallow ion incidence angle and lower beam energies. This reduces ion penetration depth and the creation of artifacts, preserving the topmost surface layer for analysis [27].

Q2: For which types of samples is the aloof beam technique most favored? The aloof beam technique is most favored for analyzing surface layers on insulating materials [26]. The large bandgap in these materials provides a lower background, which facilitates the clearer detection of subtle spectral features such as vibrational signals and bandgap states [26].

Q3: My EBSD analysis of a multi-phase material shows poor pattern quality. How can low-angle polishing help? Materials with multiple phases of varying hardness are challenging to prepare. Traditional mechanical polishing can over-polish the softer phase, while electrochemical methods struggle with different chemical compositions [27]. The Low Angle Polishing method on a plasma FIB-SEM system automates polishing at shallow angles with programmable ion beam energies (e.g., 30 keV down to 10 keV). This approach creates a uniform, deformation-free surface across all phases, which is crucial for obtaining high-quality Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) patterns [27].

Q4: What is a "nonclassical" beam damage mechanism, and why is it important? Recent research using low-dose electron microscopy has revealed beam damage mechanisms beyond the classical knock-on and radiolysis models. One such mechanism is reversible radiolysis, which involves dynamic crystalline-to-amorphous interconversion events [1]. Understanding these nonclassical pathways is crucial for developing more advanced damage mitigation strategies, as they can exhibit direct dose-rate effects and other complex behaviors [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive sample mass loss or rapid amorphization | Pre-existing surface damage or contamination from sample preparation [27]. | Implement a final low-energy (e.g., ≤ 5 kV) broad-beam Ar+ ion milling step to remove amorphous layers [28]. |

| Poor signal-to-noise ratio in aloof beam EELS | Electron beam is too far from the sample, or monochromator stability is insufficient. | Optimize the impact parameter (start at 2-10 nm from the surface) [26]. Ensure the electron monochromator is properly warmed up and stabilized for high-energy resolution [26] [28]. |

| Curtaining artifacts and non-uniform surfaces in FIB polishing | High incident angle and/or high ion beam current. | Use the Low Angle Polishing software module. Reduce the ion beam current (e.g., from 100 nA to 30 nA) and progressively lower the beam energy (e.g., from 30 keV to 10 keV) for the final polish [27]. |

| Inconsistent EBSD indexing on a multi-phase sample | Different phases have different hardnesses, leading to uneven material removal and relief. | Apply low-angle polishing with low beam energies (10-15 keV). This significantly improves EBSD pattern quality and indexing rates for all phases, as shown in Figure 5 of the source material [27]. |

Table 2: Optimizing Key Parameters for Damage Minimization

| Technique | Critical Parameter | Recommended Setting | Effect / Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aloof Beam EELS | Beam Impact Parameter | 2 nm or greater [26] | Eliminates knock-on damage; drastically reduces ionization damage. |

| Accelerating Voltage | Lower voltages (e.g., 80-120 kV) [26] | Suppresses relativistic effects and guided light modes that complicate spectral interpretation. | |

| Low-Angle FIB Polishing | Ion Incident Angle | Low angle (close to glancing incidence) [27] | Reduces ion penetration depth and minimizes subsurface damage. |

| Final Polishing Ion Energy | 10 keV [27] | Creates a superior, deformation-free surface compared to higher energies (30 keV). | |

| Ion Beam Current | Lower current (e.g., 30 nA vs. 100 nA) [27] | Reduces the milling rate and improves final surface finish. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Aloof Beam EELS for Surface Analysis

This protocol is designed for characterizing the surface of beam-sensitive materials like catalysts or insulators.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a clean, electron-transparent edge. For ceramic or metal oxide samples, use a tripod polisher and finish with a low-energy (e.g., 0.3-5 kV) broad-beam Ar+ ion mill to remove amorphous surface layers [28].

2. Microscope Setup:

- Insert the sample into a Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM) equipped with a monochromator and a Gatan Image Filter (GIF).

- Set the accelerating voltage to 200 kV [28] or consider lower voltages (e.g., 80 kV) to further minimize damage [26].

- Align the monochromator to achieve an energy resolution of approximately 0.2 eV [28].

3. Data Acquisition:

- Navigate to a region of interest near a clean sample edge.

- In STEM mode, position the electron beam at the desired impact parameter (e.g., 2-20 nm away from the sample surface) [26].

- Acquire the EELS spectrum. The delocalized nature of the low-loss and vibrational signals allows for collection even with the beam positioned outside the physical specimen [26].

- Process the acquired spectrum by removing the zero-loss peak and applying plural scattering deconvolution to obtain the single-scattering distribution [28].

Protocol 2: Low-Angle Plasma FIB-SEM Polishing for EBSD Sample Preparation

This protocol is optimized for preparing large, deformation-free surfaces of multi-phase materials for EBSD analysis.

1. Initial Sample Preparation:

- The sample should be sized to fit the FIB-SEM holder. Clean the surface to remove any contaminants.

2. Plasma FIB-SEM Setup:

- Load the sample into a system like the TESCAN AMBER X plasma FIB-SEM.

- Use the Essence Low Angle Polishing software module, which automates the sample tilt to maintain a shallow incidence angle during milling [27].

3. Polishing Procedure:

- Coarse Polish: Begin with a higher beam current (e.g., 100 nA) and energy (e.g., 30 keV) to define and clean a large area (e.g., 500 µm x 500 µm) [27].

- Fine Polish: Sequentially reduce the ion beam energy and current. A recommended sequence is:

- 30 keV at 30 nA

- 15 keV at 75 nA

- Final Polish: 10 keV at 30 nA [27].

- This step-wise reduction in energy is critical for removing the damaged layer created by the previous, higher-energy steps.

4. Quality Verification:

- After polishing, acquire an EBSD map. The success of the preparation is indicated by high band contrast and a low percentage of "zero solutions" (unindexed points) across all material phases [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Xenon (Xe) Plasma FIB-SEM | Enables high-current milling for large-area sample preparation (e.g., 500x500 µm) with minimal gallium contamination compared to traditional Ga+ FIB [27]. |

| Low Angle Polishing Software Module | Automates the sample positioning and tilt to maintain a consistent, shallow ion incident angle, which is crucial for reducing surface damage and artifacts [27]. |

| Monochromated STEM | Provides the high-energy resolution (≈0.2 eV) necessary for detecting subtle spectral features in vibrational and low-loss EELS [26] [28]. |

| Broad-Beam Argon (Ar+) Ion Mill | Used for final sample cleaning and removal of amorphous layers created during initial preparation, especially for TEM samples [28]. |

| Fast Argon Atoms | A non-contact polishing method for ceramics, effective at reducing surface roughness and friction at high angles of incidence (α > 50°) [29]. |

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Diagram Title: Damage-Minimization Workflow Selection

Diagram Title: Damage Mechanisms and Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is cryogenic temperature used in sample preparation for electron microscopy?

Cryogenic temperatures are used to preserve samples in a near-native, hydrated state by rapidly freezing them into a glass-like, non-crystalline ice. This process, called vitrification, prevents the formation of damaging ice crystals and minimizes structural artifacts caused by dehydration or chemical stains used in conventional electron microscopy. It allows biological samples to be visualized directly in their frozen-hydrated state, which is crucial for high-resolution structural determination [30] [31].

Q2: What is the single biggest challenge in cryo-sample preparation today?

The most prevalent challenge is sample interaction with the air-water interface (AWI). When a thin film of sample is created on the grid before plunging freezing, the particles are exposed to a large air-water interface. This exposure can lead to partial or even complete denaturation (unfolding) of the macromolecular complex, preferential orientation of particles, and generally poor particle distribution, which severely compromises data quality [32] [33].

Q3: How can I tell if my sample has been damaged by the air-water interface?

Signs of AWI damage can often be detected during initial data processing. Common indicators include:

- Preferential Orientation: The vast majority of your particles adopt the same orientation in the ice.

- Particle Denaturation: Particles appear to be partially unfolded or only a portion of the complex is visible.

- Empty Grid Areas: Grid holes appear empty or contain very few particles, suggesting particles have been adsorbed and denatured at the interface [32] [33].

Q4: My sample is >95% pure by SDS-PAGE, but looks bad on the grid. Why?

SDS-PAGE assesses biochemical purity but does not provide information on structural homogeneity. Your sample may be pure but consist of a mixture of different conformational states or be partially disaggregated. Techniques like negative stain electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering (DLS), or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) are better for evaluating structural homogeneity and integrity, which are critical for cryo-EM [34] [35] [31].

Q5: What is the purpose of negative stain electron microscopy in cryo-EM workflows?

Negative stain EM acts as a powerful and cost-effective gatekeeper. It allows you to quickly assess sample quality, homogeneity, and appropriate concentration before committing to more expensive and time-consuming cryo-EM. It provides a visual confirmation that your sample is monodisperse, structurally intact, and at a good concentration for grid preparation [35] [31].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common problems, their causes, and potential solutions to improve your cryo-sample preparation outcomes.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Cryo-Preparation Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Denaturation at Air-Water Interface | Exposure to AWI during blotting and plunging [32] [33]. | - Use affinity grids to immobilize particles away from the AWI [32] [34].- Optimize blotting time to reduce exposure [33].- Use surfactants (e.g., detergents, fluorinated surfactants) at low concentrations to passivate the interface [34]. |

| Preferential Particle Orientation | Particles have a favored orientation at the air-water or water-substrate interface [33]. | - Alter grid surface properties (e.g., use different grid types like graphene oxide, change hydrophobicity via plasma cleaning) [35].- Adjust buffer conditions (pH, salt concentration) [36] [34].- Use affinity grids to present particles in different orientations [32]. |

| Insufficient or Too Many Particles | Incorrect sample concentration [36] [35]. | - Optimize concentration empirically, typically between 10 nM and 10 µM [35].- Use negative stain EM to check particle density beforehand [35]. |

| Poor Vitrification (Crystalline Ice) | Slow freezing speed; inappropriate blotting conditions [36] [30]. | - Ensure rapid plunging speed and proper blotting to create a thin, vitreous ice layer [36].- Maintain cryogen (liquid ethane/propane) at correct temperature (< -180°C) [36]. |

| Sample Aggregation or Disaggregation | Biochemically unstable sample; unsuitable buffer conditions [34] [31]. | - Re-optimize purification buffer (pH, salt, additives).- Use cross-linking (e.g., GraFix) to stabilize transient complexes [34].- Demonstrate sample activity to confirm native state [35]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Optimizing Sample Purity and Homogeneity

High-resolution cryo-EM requires samples with exceptional biochemical purity and structural homogeneity.

- Purification: Employ a combination of chromatography techniques such as affinity (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag), followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). SEC is particularly valuable as it separates molecules by size and shape, providing a good indicator of monodispersity [36] [34].

- Quality Control: Perform the following assessments:

- Concentration: Use concentrators (e.g., centrifugal filters with an appropriate molecular weight cutoff) to achieve the target concentration (e.g., 0.05 - 1 mg/mL, but must be empirically determined). Avoid over-concentrating, which can lead to aggregation [34] [31].

Protocol 2: Standard Plunge Freezing for Vitrification

This is the most common method for preparing cryo-EM samples [36] [31].

- Grid Preparation: Select an appropriate grid (e.g., copper or gold Quantifoil or Lacey carbon). Clean the grid using a glow discharge apparatus or plasma cleaner to make the surface hydrophilic, ensuring even sample spread [36] [35].

- Sample Application: Apply a small volume (typically 3-5 µL) of your purified sample to the glow-discharged grid [31] [33].

- Blotting: In a chamber with controlled humidity (e.g., >80%), gently blot away excess liquid using filter paper. The blotting time (typically 1-10 seconds) is critical and must be optimized to leave a thin, continuous film of sample solution across the grid holes [31] [33].

- Plunging: Immediately after blotting, rapidly plunge the grid into a cryogen (liquid ethane or a ethane/propane mixture) cooled by liquid nitrogen. The rapid cooling rate (exceeding 10,000°C/sec) is essential for vitreous ice formation [36] [31].

- Storage: Transfer the vitrified grid under liquid nitrogen to a storage box or cryo-holder for subsequent imaging [30].

Workflow Diagram: Cryo-EM Sample Preparation

The diagram below summarizes the key steps and decision points in a typical cryo-EM sample preparation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials & Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cryo-EM Sample Prep

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Holey Carbon Grids (e.g., Quantifoil) | EM support grids with a patterned holey carbon film. Particles are suspended over the holes, minimizing background noise for high-resolution imaging [36] [35]. |

| Plasma Cleaner / Glow Discharge | Instrument used to make the grid surface hydrophilic. This ensures the aqueous sample spreads evenly across the grid, preventing beading and promoting a uniform ice layer [36]. |

| Cryogen (Liquid Ethane/Propane) | Has high heat capacity and facilitates the ultra-rapid cooling necessary to form vitreous (non-crystalline) ice, preserving the sample's native structure [36] [31]. |

| Vitrification Device (Plunge Freezer) | Automated instrument that controls blotting time, humidity, and plunging speed to ensure reproducible and consistent vitrification of samples [36] [31]. |

| Negative Stains (e.g., Uranyl Acetate) | Heavy metal salts that surround dehydrated particles, providing high contrast for initial sample screening and optimization using conventional TEM [35] [31]. |

| Affinity Grids | Grids functionalized with tags (e.g., antibody, Ni-NTA) that specifically bind to the sample. This immobilizes particles, preventing interaction with the air-water interface [32] [34]. |

Simultaneous techniques, which apply two or more measurement methods to the same sample at the same time, have become indispensable in advanced materials characterization. The combination of spectroscopy with calorimetry represents a powerful approach that enables researchers to correlate structural changes with thermal events in real-time. According to the International Confederation for Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (ICTAC), "simultaneous techniques" are formally defined as "the application of two or more techniques to the same sample at the same time" [37]. This methodology has proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development, polymer science, and materials research where understanding the relationship between structural transformations and thermal properties is critical.

The fundamental advantage of these combined systems lies in their ability to eliminate interpretation uncertainties that arise when analyzing separate samples using different techniques at different times. When spectroscopic and calorimetric data are collected from the same sample simultaneously under identical conditions, researchers can directly correlate heat flow events with specific structural changes at the molecular level [37]. This integrated approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of material behavior than either technique could deliver independently.

Technical Challenges and Solutions

Common Experimental Challenges

Combining spectroscopy with calorimetry presents several technical challenges that must be addressed to obtain reliable data. The first significant challenge involves sample geometry compatibility. The ideal sample configurations for spectroscopic and calorimetric measurements often differ substantially. For calorimetry, samples are typically placed in small metal pans as thin layers for optimal heat transfer, whereas spectroscopy often requires specific geometries to maximize signal collection. This discrepancy can lead to weak spectroscopic signals when short collection times are necessary [38].

The second major challenge is energy dissipation management. The energy input from spectroscopic sources, such as lasers in Raman spectroscopy, must be carefully controlled to prevent interference with calorimetric measurements. This energy can cause localized heating that may distort DSC data or even induce premature transitions in the sample. Research has shown that these effects are particularly pronounced in single-furnace, heat flux DSC systems compared to double-furnace, power-compensated designs [38].

A third challenge involves maintaining thermal integrity while accommodating spectroscopic access. Introducing optical components or probes into a calorimeter creates potential paths for heat loss, which can compromise temperature control accuracy. Additionally, for subambient operations, these pathways can allow moisture ingress, leading to frosting issues [38].

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do I observe strange negative peaks or distorted baselines in my combined DSC-FTIR measurements?

Negative absorbance peaks in FTIR spectra often indicate a contaminated crystal in ATR accessories. This can be resolved by cleaning the crystal thoroughly and collecting a fresh background scan. Distorted baselines may result from instrument vibrations, as FTIR spectrometers are highly sensitive to physical disturbances from nearby equipment or laboratory activity. Ensure your setup is on a vibration-isolated platform away from pumps or other vibrating equipment [12].

FAQ 2: How can I minimize beam damage to sensitive samples during combined experiments?

Beam damage can be minimized through several strategies. For focused ion beam (FIB) applications on polymers, maintain a low beam current (≤100 pA) during milling to limit beam heating [39]. For X-ray beam interactions with organic materials, consider that the temperature increase due to beam heating can be quantified using FDSC and may be limited to approximately 0.2 K with proper configuration [40]. Additionally, using double-furnace DSC designs can significantly reduce laser-induced heating effects in DSC-Raman systems [38].

FAQ 3: Why does my DSC-Raman data show thermal events at different temperatures than expected?