SPR Running Buffer Mastery: A Complete Guide to Preparation, Degassing, and Troubleshooting for Flawless Data

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) running buffer in obtaining reliable, high-quality data.

SPR Running Buffer Mastery: A Complete Guide to Preparation, Degassing, and Troubleshooting for Flawless Data

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) running buffer in obtaining reliable, high-quality data. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from buffer selection and component matching to advanced methodological protocols for degassing and vesicle preparation. The article provides a systematic troubleshooting framework for common issues like bulk shifts and air bubbles, and explores validation techniques and emerging technologies. By synthesizing established best practices with cutting-edge insights, this resource serves as an essential manual for optimizing SPR assays in biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Role of SPR Running Buffer: Principles and Consequences

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensing, the running buffer is not merely a carrier solution; it is a critical component of the experimental environment that directly influences every aspect of data quality. For researchers and drug development professionals, maintaining the integrity of biomolecular interactions—whether for kinetic characterization, affinity measurements, or off-target screening—demands uncompromising rigor in buffer preparation [1]. The running buffer provides the chemical matrix in which molecular recognition occurs, and its quality dictates the signal-to-noise ratio, baseline stability, and ultimately, the reliability of calculated kinetic parameters (ka, kd, KD) [2] [3]. This application note details the direct mechanistic links between buffer quality and data integrity, providing validated protocols to safeguard your SPR research outcomes.

The Direct Link: How Buffer Quality Dictates Data Integrity

The quality of SPR running buffer impacts data integrity through three primary mechanisms: the introduction of air bubbles, particulate contamination, and suboptimal chemical conditions.

Degassing: Preventing Air-Induced Artifacts

Improperly degassed buffers lead to the formation of air bubbles within the microfluidic path. These bubbles cause significant baseline spikes and drifts by altering the refractive index at the sensor surface in an uncontrolled manner [4]. This artifact directly obscures the true binding signal, making accurate quantification of binding events difficult or impossible. Furthermore, bubbles can disrupt laminar flow, leading to inconsistent analyte delivery and introducing variability in binding kinetics.

Filtration: Eliminating Particulate Contamination

Unfiltered buffers contain microscopic particulates that can clog the microfluidic channels [4]. This clogging manifests as a gradual increase in system pressure and unstable baseline. More critically, particulates can adhere to the sensor surface, creating sites for non-specific binding and permanently damaging the sensitive gold film. This not only compromises the current experiment but can also necessitate extensive system cleaning.

Preparation: Ensuring Chemical Consistency

The use of buffers that are not freshly prepared can lead to chemical degradation and microbial growth. This alters the pH and ionic strength of the solution, which in turn affects the activity and stability of immobilized ligands and injected analytes [4] [3]. Chemical inconsistency is a major source of poor reproducibility between experimental runs. Matching the buffer composition exactly between the running buffer and the sample buffer (after dilution) is also critical to prevent bulk shift effects, a common source of injection artifacts [4].

Table 1: Consequences of Poor Buffer Quality on SPR Data

| Buffer Defect | Direct Impact on System | Manifestation in Sensorgram | Effect on Data Integrity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Degassing | Air bubble formation in microfluidics | Sharp spikes, irreversible baseline drift | Obscured binding response, inaccurate Rmax calculation |

| Incomplete Filtration | Particulate clogging of channels | Gradual baseline rise, increased noise | Poor signal-to-noise ratio, potential for surface damage |

| Non-Fresh Buffer | Chemical degradation, microbial growth | Baseline drift, altered binding kinetics | Poor reproducibility, inaccurate ka and kd values |

| Mismatched Sample/Running Buffer | Differences in refractive index | Bulk effect shifts at injection start/end | Inaccurate determination of binding onset and dissociation |

Essential Reagents and Materials

The following toolkit is essential for preparing high-quality SPR running buffers and maintaining system integrity.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Salts (e.g., PBS, HEPES) | Provides stable pH and ionic strength | Molecular biology grade, low UV absorbance |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20, P20) | Reduces non-specific binding to surfaces and tubing [4] [3] | Low fluorescence, sterile filtered |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Blocking agent to prevent non-specific binding to tubing and microfluidics [4] | Protease-free, low immunoglobulin content |

| DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide) | Increases solubility of small molecule analytes; must be matched in running and sample buffers [4] | High-purity, anhydrous |

| 0.2 µm Filter | Removes particulates to prevent microfluidic clogging [4] | Low protein binding, sterile |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Primary component of Desorb solution for deep system cleaning [5] [4] | High purity (≥99%) |

| Sodium Hypochlorite | Primary component of Sanitize solution (10% bleach) to remove biological contaminants [5] [4] | Fresh dilution from stock |

| Glycine-NaOH | Secondary component of Desorb solution (50 mM, pH 9.5) [5] [4] | High purity, pH-adjusted |

Validated Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure: Running Buffer Preparation

This protocol is adapted from established SPR maintenance guides and sample preparation tips [5] [4].

Principle: To consistently produce a high-quality, particle-free, and gas-free running buffer for SPR experiments to ensure stable baselines and reproducible binding data.

Materials:

- Buffer salts (e.g., for PBS or HEPES)

- Ultrapure water (18 MΩ·cm)

- Vacuum degassing apparatus or sonicator

- 0.2 µm vacuum filtration unit

- Optional additives: Tween-20 (0.005-0.05%), BSA (0.1 mg/mL), DMSO (1-5%)

Method:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve buffer salts in ultrapure water to the desired concentration. Adjust the pH meticulously at the temperature the experiment will be performed (typically room temperature).

- Additive Introduction: If using detergents (e.g., Tween-20) or DMSO, add them after degassing and filter sterilizing the primary buffer solution. Pour gently to prevent reintroduction of gas [4].

- Filtration: Filter the buffer through a 0.2 µm filter into a clean, dedicated buffer bottle. This removes particulate matter that can clog microfluidics.

- Degassing: Degas the filtered buffer using a vacuum degasser (approximately 4 torr for 30 minutes) or by sonication under vacuum [4] [6]. Critical Step: Degassing immediately before use is most effective.

- Storage: Use the buffer immediately. Rule of thumb: Make fresh running buffer every day [4]. Do not store degassed buffers for extended periods.

Protocol: System Cleaning and Maintenance

This protocol is critical for data integrity after instrument idle time or when baseline drift is observed [5] [4].

Principle: To remove accumulated contaminants from the microfluidic system using a series of cleaning solutions, restoring a stable baseline and preventing carryover.

Materials:

- Desorb Solution 1: 0.5% (w/v) SDS in pure water [5] [4]

- Desorb Solution 2: 50 mM Glycine-NaOH, pH 9.5 [5] [4]

- Sanitize Solution: 10% bleach (0.5% sodium hypochlorite) [5] [4]

- ddH2O

- Blank or "Maintenance" sensor chip

Method:

- Chip Docking: Dock a blank or dedicated "Maintenance" sensor chip to avoid damaging an active experimental chip [5].

- Desorb Procedure:

- Place all active buffer and sample wash tubing into the Desorb 1 solution.

- Run the automated Desorb command. The system will typically wash with Desorb 1 for ~41 minutes, followed by Desorb 2 and ddH2O (total time ~2 hours) [4].

- Sanitize Procedure:

- Place all active tubing into the Sanitize solution.

- Run the automated Sanitize command. The system will wash with Sanitize, followed by ddH2O and running buffer (total time ~2 hours) [4].

- Equilibration: After cleaning, prime the system with freshly prepared, degassed running buffer and allow it to equilibrate on a continuous flow until a stable baseline is achieved.

Data Validation and Quality Control

Quantitative Benchmarks for Buffer-Derived Artifacts

Establishing expected performance benchmarks allows for the objective assessment of buffer-related problems.

Table 3: Quantitative Benchmarks for System Performance Related to Buffer Quality

| Performance Parameter | Acceptable Range | Indication of Buffer Problem |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Noise Level | < 0.1-0.5 RU (instrument dependent) | High frequency noise > 1 RU suggests particulates or bubbles |

| Baseline Drift | < 5 RU/hour over 10 minutes | Consistent drift > 10 RU/hour suggests contamination or outgassing |

| Bulk Shift Magnitude | Minimal; should be fully reversible | Large, irreversible shifts indicate buffer mismatch |

| Chi² Value in Fitting | Square root of Chi² similar to instrument noise | High Chi² can indicate buffer-induced instability [2] |

| Rmax Consistency | < 5% decrease over multiple cycles | Progressive loss suggests harsh regeneration or surface fouling [2] |

Visual Inspection and Curve Validation

Always inspect sensorgrams and residuals for tell-tale signs of buffer issues [2].

- Check Residuals: After fitting a binding model, the residual plot (difference between fitted curve and actual data) should be randomly scattered around zero. Systematic deviations in the residuals can indicate a bulk effect or other buffer-related artifact that the model could not account for [2].

- Assess Dissociation: The dissociation phase should be monitored long enough to see at least 5% dissociation from the starting value. For very slow off-rates (kd < 1x10-5 s-1), this may require up to 90 minutes of dissociation time [2].

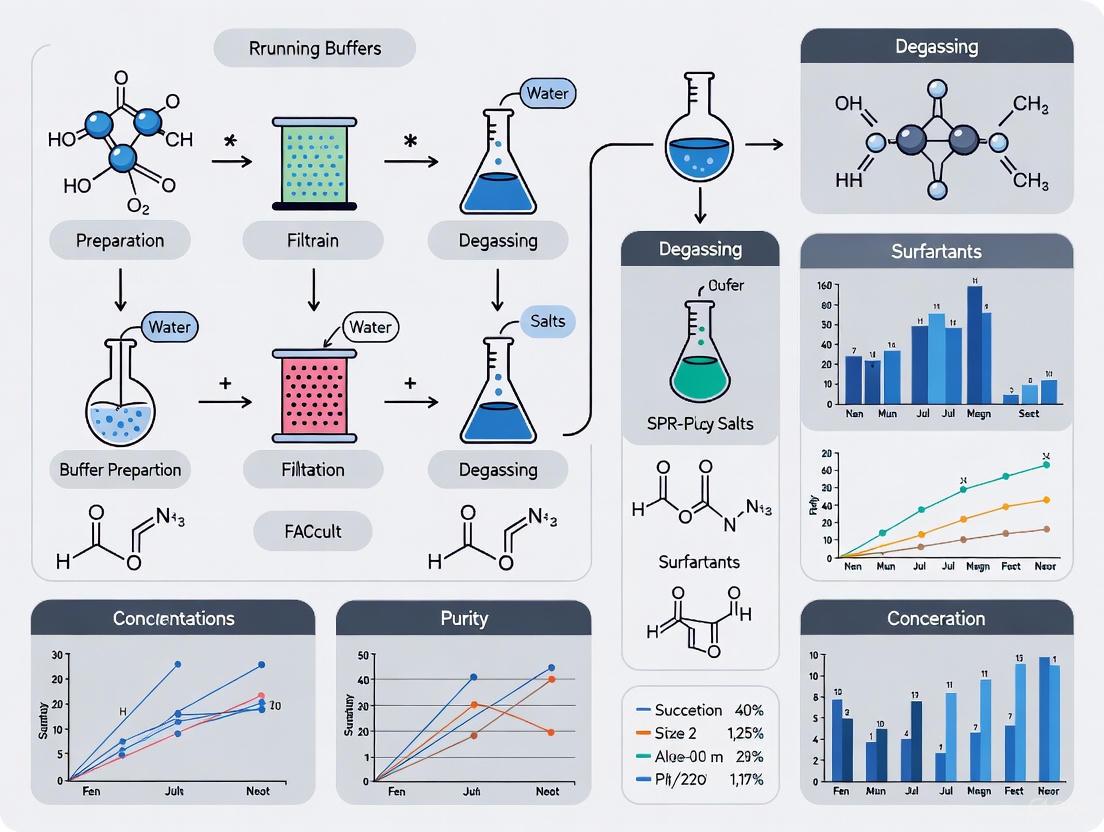

Workflow: Buffer Quality Impact on SPR Data

The following diagram illustrates the cascade of effects that poor buffer quality has on an SPR experiment, ultimately leading to compromised data integrity.

In SPR biosensing, there is no separation between sample integrity and buffer integrity. For researchers in drug development, where decisions are made based on nanomolar differences in affinity or subtle kinetic profiles, the quality of the running buffer is a primary determinant of success. As demonstrated, failures in buffer preparation—whether in degassing, filtration, or freshness—directly introduce noise, drift, and artifacts that corrupt the very data the instrument is designed to measure. By adhering to the rigorous protocols and validation checks outlined in this application note, scientists can ensure that their SPR data reflects biological truth rather than experimental artifact, thereby de-risking the critical path from discovery to development.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) technology, the running buffer is a critical component that forms the hydrodynamic and biochemical environment for biomolecular interaction analysis. The choice of buffer directly influences the stability of the baseline, the specificity of binding events, and the overall quality of kinetic data. This application note details the core formulations of HBS-EP and HEPES-KCl buffers, along with essential additives, providing researchers with standardized protocols for reproducible SPR experimentation. Proper buffer preparation is fundamental to maintaining near-physiological conditions while minimizing non-specific binding and refractive index artifacts, thereby ensuring the accuracy of affinity and kinetic measurements [7] [8] [9].

Core Buffer Formulations and Composition

The selection of an appropriate running buffer is paramount for successful SPR experiments. The buffer must provide stable pH, maintain ionic strength, and include specific additives to reduce non-specific interactions. The following table summarizes the key components and their functions in two commonly used SPR running buffers.

Table 1: Core Components of Common SPR Running Buffers

| Component | Function | HBS-EP+ Buffer (10X) [7] | HEPES-KCl Buffer [8] |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEPES | Buffering capacity, pH stability | 100 mM | 10 mM |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Maintains ionic strength & osmolarity | 1.5 M | - |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Maintains ionic strength & osmolarity | - | 150 mM |

| EDTA | Chelates divalent metal ions | 30 mM | - |

| Surfactant (P20/Tween-20) | Reduces non-specific binding | 0.50% (v/v) | - |

| Final pH | Optimal for biomolecular interactions | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 7.4 |

HBS-EP+ Buffer is a specialized formulation for SPR protocols. HEPES provides effective buffering in the physiological pH range, while 1.5 M NaCl (when diluted to 1X) creates a near-physiological salt environment. The inclusion of EDTA is crucial for chelating divalent cations that could promote non-specific aggregation or unwanted enzymatic activity. The surfactant P20, a proprietary formulation equivalent to Tween-20, is vital for coating fluidic paths and sensor surfaces to minimize nonspecific binding of analytes [7] [9]. This buffer is commercially available as a concentrated solution (e.g., 10X or 20X), requiring only dilution with sterile, ultrapure water to achieve the 1X working concentration [7] [9].

HEPES-KCl Buffer offers a simpler, detergent-free alternative, which is particularly advantageous when studying membrane proteins or lipid vesicles, as detergents can destabilize these structures [8]. Its lower ionic strength (150 mM KCl) may be preferable for studying electrostatic interactions. The absence of surfactant makes the baseline more susceptible to drift and non-specific binding, requiring exceptionally clean samples and surfaces. This buffer is typically prepared fresh in the laboratory from stock solutions.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Buffer Preparation and Degassing

Proper preparation of running buffer is a critical step that directly impacts baseline stability and data quality.

Materials:

- Ultrapure water (18 MΩ resistivity at 25°C)

- HEPES, Sodium Chloride, EDTA Disodium Salt, Tween-20 (for HBS-EP+)

- HEPES, Potassium Chloride (for HEPES-KCl)

- 0.22 µm vacuum filtration unit

- Buffer degassing station or vacuum chamber

- Sterile storage bottles

Procedure for HBS-EP+ (1X Working Solution):

- Dilution: Aseptically dilute the 10X HBS-EP+ concentrate with ultrapure water to a 1X final concentration. For example, add 100 mL of 10X stock to 900 mL of water to make 1 L of 1X buffer [7].

- Homogenization: Invert the buffer bottle at least 8 times to ensure thorough mixing. Inadequate mixing can create concentration gradients, leading to a constantly drifting baseline due to refractive index mismatches [10].

- Degassing: Degas the buffer for approximately 30 minutes using a vacuum degassing system or by stirring under a mild vacuum. Degassing removes dissolved air that can form bubbles within the microfluidics, causing sharp "air-spikes" in the sensorgram [11] [4].

- Storage: Store the degassed buffer in a clean, sealed container at room temperature. Buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air, which will outgas inside the warm SPR instrument, creating spikes [4].

Procedure for HEPES-KCl Buffer:

- Weighing and Dissolution: Weigh 2.38 g HEPES (10 mM final) and 11.18 g KCl (150 mM final). Dissolve in approximately 800 mL of ultrapure water.

- pH Adjustment: Adjust the pH to 7.4 using NaOH or KOH.

- Final Volume: Bring the final volume to 1 L with ultrapure water.

- Filtration and Degassing: Sterilize the buffer by filtering through a 0.22 µm filter, then degas as described above [8].

Note: If a detergent like Tween-20 is required for a HEPES-KCl buffer (typically at 0.005-0.05%), it should be added after the degassing step to prevent excessive foam formation [4].

System Equilibration and Baseline Stabilization

A stable baseline is a prerequisite for collecting high-quality binding data. The following workflow outlines the key steps to achieve system equilibrium.

Detailed Steps:

- System Priming: After preparing a fresh running buffer, prime the SPR system according to the manufacturer's instructions. This replaces the old buffer in the pumps and tubing, preventing buffer mixing that causes "waviness" in the baseline with each pump stroke [11].

- Chip Docking and Equilibration: Dock the appropriate sensor chip at least 12 hours prior to running the experiment. Flow running buffer continuously at the experimental flow rate. This prolonged equilibration hydrates the dextran matrix of the sensor chip and washes out preservatives, significantly reducing baseline drift [5] [11].

- Start-up Cycles: Incorporate at least three to five start-up cycles at the beginning of your experimental method. These cycles should mimic your sample injections but use running buffer instead of analyte. If a regeneration step is used, include it in these cycles. This "primes" the surface and stabilizes the system. These cycles should be excluded from the final analysis [11] [4].

- Baseline Assessment: Monitor the baseline response until it stabilizes. A stable baseline should have minimal drift and a low noise level (< 1 Resonance Unit (RU) is ideal) [11].

Troubleshooting Common Buffer-Related Issues

Even with careful preparation, buffer-related issues can arise. The following table outlines common problems, their likely causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Buffer-Related Issues in SPR

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Baseline Drift | Sensor surface not fully equilibrated; Buffer not freshly prepared; Buffer concentration gradient. | Equilibrate chip with running buffer for >12 hours [11]; Prepare fresh buffer daily [11] [4]; Invert buffer bottle 8+ times before degassing to ensure homogeneity [10]. |

| Air Spikes in Sensorgram | Dissolved air in buffer; Buffer stored at 4°C. | Ensure thorough degassing of buffer; Use buffer at room temperature [11] [4]. |

| High Noise Level | Contaminated buffers or fluidics; Inadequate filtration. | Prepare fresh, filtered (0.22 µm) buffer daily [11] [4]; Perform system cleaning (Desorb, Sanitize) [5] [4]. |

| Bulk Refractive Index Shifts | Mismatch between running buffer and sample buffer; Poorly mixed running buffer. | Dissolve/dilute analyte in the running buffer [8]; Ensure running buffer is thoroughly homogenized [10]. |

| Non-Specific Binding | Lack of surfactant in buffer; "Sticky" analyte. | Add detergent to running buffer (e.g., 0.005-0.05% Tween-20) after degassing [4]; Use a reference surface and apply double referencing during analysis [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful SPR experiment relies on more than just the running buffer. The following table details key reagents and materials essential for preparing and executing a robust SPR study.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SPR Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| L1 Sensor Chip | Sensor chip with lipophilic anchors for capturing lipid membranes. | Essential for studying protein-lipid interactions [8]. |

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Carboxymethylated dextran chip for covalent coupling. | General purpose chip for amine coupling of proteins, antibodies [12]. |

| Desorb Solutions | System cleaning solutions (0.5% SDS, 50 mM glycine pH 9.5). | Routine maintenance to remove contaminants from fluidics [5] [4]. |

| Sanitize Solution | Cleaning solution (0.5-10% sodium hypochlorite). | Sanitizes fluidics to remove biological contaminants [5] [4]. |

| Regeneration Solutions | Solutions to remove bound analyte without damaging ligand. | Acid (e.g., Glycine pH 2-3), base (e.g., 10-50 mM NaOH), detergents (0.01-0.5% SDS) [4]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Solvent for small molecule analytes. | Increases compound solubility; match concentration in sample and running buffer (e.g., 1-5%) [4]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Additive to reduce non-specific binding. | Prevents non-specific binding to tubing and microfluidics (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL) [4]. |

The meticulous preparation of SPR running buffers is a foundational element of reproducible and high-quality biomolecular interaction data. Adherence to the detailed protocols for HBS-EP+ and HEPES-KCl buffer preparation, degassing, and system equilibration outlined in this document will minimize baseline drift, noise, and non-specific binding. Furthermore, integrating the recommended troubleshooting strategies and essential reagents into your SPR workflow will enhance experimental robustness. By standardizing these critical pre-experimental steps, researchers can ensure the reliability of their kinetic and affinity measurements, thereby strengthening the overall conclusions of their research.

Understanding Bulk Refractive Index Shifts and Their Impact on Sensorgrams

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technology for investigating biomolecular interactions in real-time. The output of an SPR experiment is a sensorgram, a plot of the response (in Resonance Units, RU) against time, which provides a visual representation of binding events [13]. A critical, yet often confounding, factor in obtaining high-quality sensorgram data is the bulk refractive index (RI). A bulk RI shift is a change in the refractive index at the sensor surface that is not caused by a specific binding event between the ligand and analyte. Instead, it arises from a difference in composition between the running buffer and the sample solution [14]. This article, framed within a broader thesis on SPR running buffer preparation and degassing, details the sources and consequences of bulk effects and provides validated protocols for their mitigation.

The Principle of Bulk Refractive Index Shifts

The SPR signal is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index at the sensor surface. This principle is harnessed to measure the increase in mass from a binding event. However, any change in the solution's composition that alters its RI will also produce a signal. The analyte sample, often stored in a different buffer or containing stabilizing agents, will have a different RI than the running buffer flowing through the instrument.

When this sample is injected, the instrument detects the RI difference as a massive, instantaneous jump in the response—a bulk shift [14]. This shift can obscure the initial association phase of the binding event and complicate data analysis. The core of the problem is the mismatch between the running buffer and the analyte buffer [14]. Even small differences, such as variations in salt concentration or the presence of organic solvents, can cause significant responses. For example, a 1 mM difference in NaCl concentration can result in a bulk signal of approximately 10 RU [14].

Identifying and Troubleshooting Bulk Effects in Sensorgrams

Recognizing bulk shifts is the first step in troubleshooting. The table below summarizes common sensorgram artifacts and their primary causes.

Table 1: Common Sensorgram Artifacts and Their Identification

| Sensorgram Artifact | Description | Probable Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Shift Jumps | A sharp, vertical rise at the start of injection and a sharp drop at the end. The association and dissociation curves may appear normal but are offset. | Buffer mismatch between running buffer and analyte sample (e.g., differences in salt, DMSO, or glycerol concentration) [14]. |

| Spikes after Reference Subtraction | Sharp spikes only at the very beginning (1-4 seconds) and end of the injection after reference subtraction. | Slight "out-of-phase" arrival of the sample to the active and reference flow cells due to their serial arrangement, exacerbated by large bulk effects [14]. |

| Carry-over | A sudden buffer jump or spike at the beginning of an analyte injection. | Residual salt or viscous solution from a previous injection contaminating the next run [14]. |

| Air Spikes/Bubbles | Sudden, sharp spikes in the signal during an injection. | Formation of small air bubbles in the flow channels, often exacerbated by poorly degassed buffers or low flow rates [14]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving bulk RI issues based on observed sensorgram features.

Quantitative Impact of Common Solvents and Salts

Understanding the magnitude of the signal caused by common solutes is critical for experimental design. The following table provides a summary of the quantitative effects of typical solution components, illustrating why meticulous buffer matching is non-negotiable.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Common Solution Components on SPR Response

| Solution Component | Typical Context | Impact on SPR Signal & RI | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Solvent for small molecule compounds. | High refractive index causes large buffer jumps. Even small concentration differences (e.g., 0.5%) create significant RU shifts [14]. | Dialyze the analyte against the running buffer supplemented with the same DMSO concentration. Use this dialysate as the running and dilution buffer [14]. |

| Glycerol | Protein storage additive. | High refractive index, leading to bulk shifts. | Remove via dialysis or buffer exchange into the running buffer [14]. |

| NaCl (Salts) | Varying ionic strength in sample vs. running buffer. | ~10 RU signal per 1 mM NaCl concentration difference [14]. | Ensure precise buffer matching. Use the running buffer for the final sample dilution. |

| Evaporation | Sample storage in vials. | Increases analyte concentration and alters buffer composition, leading to jumps. | Always cap sample vials [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Bulk Effects

Protocol: Buffer Matching via Dialysis or Desalting

This protocol is the primary method for eliminating bulk shifts caused by differences in small molecule solutes and salts between the sample and running buffer.

- Preparation of Dialysis Buffer: Prepare a sufficient volume (e.g., 1 L) of the running buffer that will be used in the SPR experiment. If the analyte requires a component like DMSO for stability, add it to the running buffer at the exact final concentration that will be present in the sample.

- Sample Dialysis:

- Place the analyte sample in a dialysis tube or cassette with an appropriate molecular weight cutoff.

- Submerge the sealed dialysis unit in a large volume (e.g., 500x the sample volume) of the prepared running buffer.

- Dialyze at the recommended temperature (typically 4°C for proteins) with gentle stirring for several hours or overnight.

- Change the dialysis buffer at least once and continue dialysis for another few hours.

- Alternative: Buffer Exchange via Size Exclusion Chromatography:

- For smaller volumes, use a desalting or buffer exchange column (e.g., PD-10, Zeba Spin Columns) pre-equilibrated with the running buffer.

- Load the sample and elute according to the manufacturer's instructions, collecting the protein fraction in the new buffer.

- Final Buffer Usage: The buffer used in the final dialysis step or for column equilibration must be used as the running buffer in the SPR instrument and for any further dilution of the dialyzed analyte [14].

Protocol: Injection System and Buffer Integrity Test

This quality control procedure tests the overall health of the fluidics system and the quality of the buffer matching before running valuable samples.

- Chip and System Equilibration: Install a plain gold or dextran-coated sensor chip. Equilibrate the system with the degassed running buffer until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Preparation of Test Solutions: Create a solution with 50 mM extra NaCl dissolved in the running buffer. Then, prepare a dilution series of this solution in the running buffer (e.g., 50, 25, 12.5, 6.3, 3.1, 1.6, 0.8, 0 mM extra NaCl).

- Injection and Monitoring:

- Inject the solutions from low to high concentration (single cycle kinetics), ending with an injection of running buffer alone.

- Closely monitor the sensorgrams. The rise and fall of the curve should be smooth and immediate. The steady-state phase should be flat, without drift.

- The highest NaCl concentration will yield a signal of over 550 RU, confirming the ~10 RU/mM NaCl effect [14].

- Interpretation: The final running buffer injection checks for carry-over. A smooth, stepwise response confirms good system performance and well-matched buffers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for SPR Running Buffer Management

| Item | Function in Bulk RI Management |

|---|---|

| Degassing Apparatus | Removes dissolved air from buffers to prevent the formation of air bubbles, which cause spikes in the sensorgram [14]. |

| 0.22 µm Membrane Filters | Filters buffers to remove particulate matter that could clog the microfluidic system and introduces a source of contamination. |

| Dialysis Tubing/Cassettes | Allows for the equilibration of the analyte sample with the running buffer, eliminating differences in salt and small molecule composition [14]. |

| Size Exclusion Desalting Columns | Provides a rapid method for exchanging the buffer of small-volume analyte samples into the running buffer. |

| SPR Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, C1, SA) | The sensor surface. Using a reference surface (a channel with no ligand immobilized) is crucial for subtracting residual bulk effects [14] [15]. |

Advanced Considerations and Buffer Preparation Best Practices

For a thesis focused on buffer preparation, it is critical to adhere to rigorous buffer hygiene. Fresh buffers should be prepared daily, 0.22 µm filtered, and degassed before use [14]. It is bad practice to top up old buffer with new, as this can introduce contaminants or biological growth.

Furthermore, the excluded volume effect can cause artifacts. Differences in ligand density between the active and reference surfaces can lead to them responding differently to changes in ionic strength or organic solvent, as they have different displaced volumes [14]. This can be diagnosed by injecting a control solution with the same RI as the analyte but no binding capability.

Modern SPR systems also offer advanced features like real-time bulk compensation (e.g., BioNavis's PureKinetics), which actively measures the bulk RI of the solution, allowing for the analysis of samples containing DMSO without requiring it in the running buffer [14]. The buffer itself is a key experimental variable; as studies on other optical biosensors like Whispering Gallery Modes (WGM) have shown, even minuscule changes in buffer RI can significantly impact the sensor's wavelength shift and apparent sensitivity [16].

Within surface plasmon resonance (SPR) research, the preparation of running buffer is a foundational step that directly influences data integrity and experimental success. A meticulously prepared buffer is paramount for maintaining stable baselines, minimizing non-specific binding, and achieving accurate kinetic measurements. The process of buffer degassing serves as a critical control point to prevent the formation of air bubbles, a common source of significant experimental artifact [11] [17]. In SPR systems, air bubbles introduce abrupt signal spikes, cause baseline instability and drift, and can potentially damage the sensitive hydrodynamic flow system or the functionalized sensor surface [11] [18]. These disruptions compromise the detection of true biomolecular interactions, leading to unreliable data and wasted resources.

The necessity of degassing is rooted in the physics of SPR instrumentation. SPR functions as a highly sensitive refractometer, detecting minute changes in the refractive index at the sensor surface [19] [20]. Air bubbles possess a refractive index vastly different from aqueous buffers, and their passage through the flow cell creates massive, anomalous signals that obscure legitimate binding events [20]. Furthermore, bubbles can become trapped in microfluidic channels, creating persistent baseline drift by altering flow dynamics and pressure [18]. Therefore, proper degassing is not merely a recommended best practice but an essential, non-negotiable step in any rigorous SPR running buffer preparation protocol designed to ensure the highest data quality.

Key Principles: How Bubbles Disrupt SPR Assays

Consequences of Air Bubbles in Microfluidic Systems

The integration of microfluidics with biosensors, while enabling automated and precise fluid handling, also increases susceptibility to disruptions from gaseous microbubbles [18]. The consequences of bubble formation are severe and multifaceted, directly impacting key performance metrics as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Impact of Air Bubbles on SPR System Performance

| Performance Metric | Impact of Air Bubbles |

|---|---|

| Baseline Stability | Induces significant drift and instability as bubbles traverse the flow cell or become lodged, altering local refractive index [11] [17]. |

| Signal Integrity | Causes sharp, unpredictable spikes in the sensorgram that can mask legitimate binding signals or be misinterpreted as binding events [11]. |

| Assay Replicability | Introduces random, uncontrolled variables, leading to high intra- and inter-assay variability and poor reproducibility [18]. |

| Sensor Surface Integrity | Can displace or damage the immobilized ligand layer upon contact, degrading surface binding activity and necessitating chip replacement [18]. |

| Operational Yield | A major cause of assay failure, requiring aborted runs and repetition, which wastes valuable samples, reagents, and time [18]. |

The Underlying Signaling Pathway of Bubble-Induced Artifacts

The disruptive effect of an air bubble follows a defined pathway from its formation to the final data artifact. The following diagram visualizes this cascade, which underpins the necessity of rigorous degassing protocols.

Diagram 1: Cascade of bubble-induced SPR artifacts.

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Degassing Procedures

Protocol 1: In-Laboratory Vacuum Degassing

This protocol describes a standardized method for preparing and degassing SPR running buffer using a vacuum filtration system, a common setup in most life science laboratories.

Principle: Applying a vacuum to the buffer solution reduces the partial pressure of dissolved gases, lowering their solubility and causing them to effervesce out of the solution, after which they are removed from the system.

Materials:

- Buffer Components: High-purity water and analytical grade reagents.

- Vacuum Source: Laboratory vacuum line or vacuum pump.

- Filtration Apparatus: Vacuum flask and a bottle-top vacuum filter with a 0.22 µm membrane [11].

- Storage Vessel: Clean, sterile glass bottle.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Solution Preparation: Completely dissolve all buffer constituents in high-purity water. Stir gently to minimize vortexing and shearing.

- Filtration and Degassing: Assemble the bottle-top vacuum filter (0.22 µm pore size) onto a clean vacuum flask. Pour the buffer into the filter unit, apply a vacuum for 10-15 minutes, or until vigorous effervescence ceases. Filtration simultaneously removes particulate matter and dissolved gases [11].

- Storage: Transfer the degassed buffer from the vacuum flask into a clean, sterile storage bottle. Seal the bottle to minimize reabsorption of atmospheric gases.

- Pre-Use Equilibration: Before starting the SPR experiment, bring the required volume of degassed buffer to the instrument's operating temperature. It is considered bad practice to add fresh buffer to old buffer remaining in the system, as this can introduce contaminants [11].

Protocol 2: On-Instrument Dynamic Degassing

Many modern SPR instruments are equipped with integrated, in-line degassers. This protocol outlines their use and verification.

Principle: These systems typically use gas-permeable membranes or create turbulent flow under negative pressure to strip dissolved gases from the buffer immediately before it enters the microfluidic cartridge.

Materials:

- SPR instrument with integrated dynamic degasser.

- Buffer prepared according to Protocol 1.

Step-by-Step Method:

- System Prime: Prime the entire fluidic system of the SPR instrument with the buffer. The priming process itself often routes the buffer through the internal degasser.

- Baseline Monitoring: After priming, flow the running buffer over the sensor surface and monitor the baseline response. A stable baseline with minimal noise indicates successful degassing and system equilibration [11].

- Start-Up Cycles: Incorporate at least three start-up cycles into the experimental method where buffer is injected instead of analyte. This helps to "prime" the surface and fluidics, stabilizing the system before actual data collection begins [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful degassing and buffer preparation rely on specific laboratory reagents and equipment. The table below details these essential items and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Preparation

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Membrane Filter | Critical for removing particulate matter that could nucleate bubble formation and clog microfluidic channels [11]. |

| Vacuum Pump / Degassing Unit | Provides the vacuum force required to remove dissolved gases from the buffer solution [19] [21]. |

| High-Purity Water | The solvent base; minimizes ionic and organic contaminants that contribute to background noise and nonspecific binding. |

| Non-ionic Surfactant (e.g., Tween-20) | Added to the buffer after degassing to reduce surface tension and wet the microfluidic channels and sensor surface, further inhibiting bubble formation [11] [22]. |

| Clean, Sterile Storage Bottles | Prevents bacterial growth and chemical contamination of the prepared buffer, which can cause drift and noise [11]. |

Advanced Strategies and Integrated Bubble Mitigation

For systems persistently plagued by bubbles, a multi-faceted approach beyond simple degassing is required. Research by Puumala et al. demonstrates that effective bubble mitigation is achieved by combining microfluidic device degassing, plasma treatment, and microchannel pre-wetting with a surfactant solution [18]. This combined strategy addresses the problem at multiple points: removing gases from the fluid, modifying the channel surface to be more hydrophilic, and reducing the fluid's surface tension.

The following workflow diagram integrates degassing into a comprehensive buffer preparation and system equilibration protocol, highlighting its role within a broader context.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for SPR buffer prep and equilibration.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Persistent Baseline Issues

Despite degassing, baseline problems can occur. This guide helps diagnose and address common issues.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Baseline Drift and Bubble-Related Issues

| Observation | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual, continuous baseline drift | Buffer not fully equilibrated with sensor surface; insufficient degassing; buffer contamination [11] [17]. | Flow running buffer for longer to equilibrate (e.g., overnight for new surfaces). Re-degas buffer. Prepare fresh buffer in a clean container [11]. |

| Sudden, large spikes in sensorgram | Air bubbles entering the flow cell, often from a depleted buffer source or leak in the fluidic path [17]. | Check buffer supply for low volume. Inspect tubing and connections for leaks. Ensure degasser is functioning correctly. |

| High-frequency baseline noise | Electrical interference; mechanical vibrations; or very small, persistent microbubbles [17]. | Relocate instrument to minimize vibrations. Ensure proper grounding. Increase surfactant concentration slightly (e.g., 0.01% Tween-20) to suppress micro-bubbles. |

| Drift after buffer change | Inadequate priming after changing to a new buffer, leading to mixing of buffers with different refractive indices [11]. | Prime the system thoroughly after each buffer change. Allow sufficient time for the baseline to stabilize before starting injections. |

| Wavy or oscillating baseline | Mismatch between buffer temperature and instrument control, or a malfunctioning degasser. | Allow more time for the buffer to reach set temperature. Verify and service the instrument's degasser and temperature control unit. |

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, the principle of buffer matching is a critical precept for ensuring data accuracy and reliability. Buffer matching refers to the practice of minimizing differences in composition between the analyte sample and the running buffer, a process essential for reducing optical artifacts and obtaining true binding signals. Bulk shift, or solvent effect, occurs when a difference exists between the refractive index (RI) of the analyte solution and the running buffer [22]. This phenomenon creates a distinctive 'square' shape in sensorgrams due to large, rapid response changes at the start and end of analyte injection, potentially obscuring genuine binding events, particularly those with small responses or rapid kinetics [22]. This application note details systematic strategies and protocols for effective buffer matching within the broader context of SPR running buffer preparation, providing researchers with actionable methodologies to enhance data quality.

Understanding Bulk Shift Effects

Fundamental Principles and Consequences

Bulk shift effects originate from the core operating principle of SPR technology, which detects changes in the refractive index (RI) at the sensor surface [23]. While SPR instruments are exquisitely sensitive to binding-induced RI changes, they cannot intrinsically distinguish these from RI changes caused by variations in buffer composition between the sample and running buffer. Even minor differences in the concentration of salts, solvents, or other additives can generate significant bulk RI responses [22].

The primary consequence of uncompensated bulk shift is the distortion of binding sensorgrams, which complicates the differentiation of small binding-induced responses and other interactions with rapid kinetics from a high refractive index background [22]. Although reference subtraction can partially compensate for these effects, the correction may not always adequately account for the bulk effect, particularly with modern high-sensitivity SPR systems [22]. Therefore, preventive strategies through careful buffer matching are consistently more effective than post-acquisition correction.

Problematic Buffer Components

Certain buffer components are particularly prone to causing bulk shift effects, even when they are necessary for analyte or ligand stability. The table below summarizes common problematic components and recommended mitigation strategies:

Table 1: Common Buffer Components Causing Bulk Shift and Recommended Solutions

| Component | Typical Concentration Range | Primary Function | Bulk Shift Risk | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | >1% | Solubilizing small molecules | High | Use the lowest possible concentration; ensure exact match between analyte and running buffer; employ calibration if necessary [22] [24] |

| Glycerol/Sucrose | 1-10% | Protein stabilization, cryoprotection | Moderate to High | Avoid unless absolutely necessary; use minimal required concentration with exact buffer matching [22] |

| High Salt Concentrations | >250 mM | Maintaining ionic strength | Moderate | Precisely match salt concentrations; use reference surface subtraction [22] [24] |

| Detergents | 0.01-0.1% | Reducing non-specific binding | Low to Moderate | Use consistent brand and concentration; Tween-20 is recommended at 0.01-0.1% [22] [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Buffer Matching

Standard Buffer Matching Procedure

This protocol establishes a baseline methodology for preparing matched running buffer and analyte solutions for SPR experiments.

3.1.1 Materials and Reagents

- HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS-PE): 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.01% surfactant P20 [24]

- Tris Buffered Saline (TBS-P): 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% P20 [24]

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS-P): 10.1 mM Na₂PO₄, 1.8 mM KH₂PO₄, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4, 0.01% P20 [24]

- Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

- Buffer additives as required (e.g., BSA, CaCl₂, CM-dextran)

- Analytical grade salts and pH adjustment solutions

3.1.2 Equipment

- pH meter with temperature compensation

- Vacuum filtration apparatus (0.22 µm membrane)

- Buffer degassing system (in-line or offline)

- Analytical balance (0.1 mg sensitivity)

- Volumetric flasks and pipettes

3.1.3 Procedure

- Prepare Running Buffer Stock Solution: Prepare a 2-5 liter stock of the selected running buffer (HBS-PE, TBS-P, or PBS-P) using ultrapure water. Precisely weigh all components to ensure consistency.

- Adjust pH and Osmolality: Adjust the buffer to the required pH at the temperature the experiment will be conducted. Verify osmolality if necessary.

- Filter and Degas: Filter the entire buffer volume through a 0.22 µm membrane to remove particulates [24]. Degas the buffer thoroughly to prevent micro-bubble formation in the fluidic system [5] [24].

- Prepare Analyte Dilutions: Using the freshly prepared and degassed running buffer, prepare all analyte dilution series. Perform serial dilutions to minimize cumulative pipetting errors [22].

- Equilibrate System: Before starting experiments, equilibrate the SPR system with running buffer until a stable baseline is achieved (typically 30-60 minutes).

3.1.4 Critical Steps Notes

- Always use the same buffer batch for running buffer and analyte dilution to minimize lot-to-lot variation.

- Avoid cooling degassed buffer as this can cause gas re-uptake and bubble formation [24].

- For multi-day experiments, store running buffer appropriately to prevent contamination or evaporation.

Specialized Buffer Matching with Additives

Some experimental systems require specific additives to maintain biomolecule stability or function. This protocol addresses matching strategies for these challenging systems.

3.2.1 DMSO-Containing Buffers

- Prepare Base Running Buffer: Prepare the standard running buffer without DMSO.

- Add DMSO to Running Buffer: Add the required percentage of DMSO directly to the running buffer. For small molecule studies, typically use 1-2% DMSO, never exceeding 5%.

- Calibrate System: Perform a calibration run if significant solvent effects are anticipated [24].

- Prepare Analyte Solutions: Dissolve analytes in the same DMSO-containing running buffer, not pure DMSO.

3.2.2 Stabilizing Additives (BSA, Carrier Proteins)

- Identify Minimal Effective Concentration: Determine the lowest concentration of additive (e.g., BSA) that prevents non-specific binding and surface adsorption.

- Add to Running Buffer Only: Incorporate the additive (typically 0.1% BSA) into the running buffer to minimize analyte adsorption to system vials and tubing [24].

- Exclude from Analyte Buffer: Do not add these blocking agents to analyte samples to prevent competition with binding interactions.

3.2.3 Ion-Dependent Interactions

- Identify Essential Ions: Determine which ions (e.g., Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, Mg²⁺) are required for the interaction [24].

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Create concentrated stock solutions of these ions in ultrapure water.

- Add to Both Buffers: Precisely add the same concentration of ions to both running buffer and analyte dilution buffer.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for buffer matching strategies:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful buffer matching requires specific reagents and materials selected for their purity, consistency, and compatibility with SPR systems. The following table details the essential components of a buffer matching toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Matching

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Buffer Matching | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffers | Molecular biology grade HEPES, TRIS, or phosphate salts | Provides consistent ionic background and pH control | Prefer single large batch to ensure consistency [24] |

| Surfactant P20 | 0.01% in final buffer (10% stock solution) | Reduces non-specific binding to fluidics and surfaces | Use consistent brand; concentration affects baseline [24] |

| Ultrapure Water | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistance, <5 ppb TOC | Prevents contamination and particulate introduction | Always use for all buffer preparations [5] |

| DMSO | Spectrophotometric grade, low UV absorbance | Solvent for small molecule analytes | Match concentration exactly between buffer and sample [24] |

| BSA | Protease-free, low immunoglobulin content | Blocks non-specific binding in running buffer | Add only to running buffer, not analyte samples [24] |

| Filter Membranes | 0.22 µm pore size, low protein binding | Removes particulates that could clog microfluidics | Always filter before degassing [5] [24] |

| Concentrated Salt Solutions | Analytical grade NaCl, KCl, etc. | Adjusts ionic strength to match physiological conditions | Precisely match concentrations in all solutions |

Quality Assessment and Validation

Bulk Shift Detection and Analysis

Validating successful buffer matching requires analytical methods to detect and quantify bulk shift effects. The primary assessment occurs during preliminary runs without immobilized ligand or using a reference surface.

5.1.1 Sensorgram Analysis

- Characteristic Signature: Look for the tell-tale 'square' shape in sensorgrams with large, rapid response changes at injection start and end points [22].

- Response Magnitude: Quantify the bulk response magnitude in Resonance Units (RU). While reference subtraction can correct for bulk effects, significant shifts (>10 RU) may indicate problematic mismatch.

- Kinetic Artifacts: Examine whether the bulk effect obscures the initial association or dissociation phases of binding events.

5.1.2 Buffer Scouting Approach For challenging systems with unavoidable additives, implement a systematic buffer scouting protocol:

- Run a dilution series of analyte in perfectly matched buffers (positive control).

- Introduce deliberate, known mismatches in specific components (e.g., ±1% DMSO, ±50 mM salt).

- Quantify the resulting bulk shift responses to establish acceptable tolerance ranges.

The following workflow illustrates the quality assessment process for buffer matching:

Documentation and Reporting Standards

Comprehensive documentation of buffer preparation is essential for experimental reproducibility and troubleshooting. The following elements should be recorded:

5.2.1 Buffer Composition Documentation

- Exact identities and sources of all buffer components

- Final concentrations of all salts, buffers, and additives

- pH measurement temperature and exact values

- Batch numbers and preparation dates

5.2.2 Preparation Parameters

- Filtration method and membrane specifications

- Degassing method and duration

- Storage conditions and duration before use

Effective buffer matching through meticulous preparation of running buffers and analyte solutions represents a foundational element of robust SPR experimentation. By systematically addressing potential refractive index mismatches at their source, researchers can significantly reduce bulk shift artifacts, thereby enhancing data quality and reliability. The protocols and strategies outlined in this application note provide a standardized approach to buffer matching that aligns with the broader objectives of SPR running buffer preparation research. Implementation of these methodologies will enable researchers to distinguish true molecular interactions from solvent-based artifacts, ultimately leading to more accurate kinetic and affinity measurements in drug development and basic research applications.

Step-by-Step Protocols: From Buffer Preparation to Liposome Handling

Within Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, the quality of the running buffer is a fundamental determinant of data reliability and instrument integrity. This Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) outlines the protocols for the preparation, filtration, and degassing of running buffers for SPR instrumentation. Consistent adherence to this procedure is critical for maintaining a stable baseline, preventing the introduction of air bubbles and particulate matter into the microfluidics, and ensuring the reproducibility of biomolecular interaction analyses [5] [1]. This document is framed within a broader thesis investigating the optimization of SPR running buffers to enhance the accuracy of kinetic and affinity measurements in drug development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

The following table details the essential reagents and materials required for the successful execution of this protocol.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for SPR Buffer Preparation

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Buffer Salts | High-purity grade (e.g., USP, ACS) for consistent ionic strength and pH. |

| Ultrapure Water | Type I (18.2 MΩ·cm at 25°C) to minimize contaminant interference. |

| 0.22 µm Filters | Sterilization and removal of particulates and microorganisms [25] [26]. |

| Filter Membrane | PES: Recommended for aqueous buffers due to low protein-binding [25] [26]. |

| Vacuum Pump / Syringe | For driving the filtration process. |

| Degassing Unit | In-line degasser or sonication bath to remove dissolved gases [5]. |

| pH Meter | Calibrated instrument for accurate pH adjustment. |

| Sterile Storage Bottles | Chemical-resistant vessels (e.g., glass, PP) for storing prepared buffer. |

Quantitative Filter Selection Data

Selecting the appropriate 0.22 µm filter is crucial for both sterility and chemical compatibility. The following tables provide a quantitative guide for selection based on sample type and membrane properties.

Table 2: Filter Membrane Selection Guide by Chemical Compatibility

| Membrane Material | Hydrophilicity | Protein Binding | Strong Acid/Base | Organic Solvents | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethersulfone (PES) | Hydrophilic | Low | Poor | Moderate | Aqueous SPR running buffers, cell culture media [25] [26]. |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | Hydrophilic | Medium | Moderate | Good | General purpose filtration, biopharma applications [26]. |

| Nylon | Hydrophilic | Medium-High | Moderate | Poor | Water samples, polar solvents (not for sensitive LC-MS) [26]. |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) | Hydrophobic | Very Low | Excellent | Excellent | Organic solvents, aggressive chemicals [25] [26]. |

Table 3: Performance Characteristics for Different Applications

| Application | Recommended Membrane | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Aqueous SPR Buffer | PES | Low protein-binding preserves analyte integrity; high flow rate [26]. |

| Buffers with Organic Solvents | PTFE | Superior chemical resistance and compatibility [25] [26]. |

| Routine Filtration (aqueous) | PVDF | Good balance of flow rate and chemical resistance [26]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Buffer Preparation

- Weighing: Using an analytical balance, weigh the required mass of high-purity buffer salts into a clean, sterile container.

- Reconstitution: Add the correct volume of Type I ultrapure water to achieve the desired buffer concentration. Stir vigorously until all salts are completely dissolved.

- pH Adjustment: Calibrate the pH meter with standard buffers. Adjust the pH of the solution to the target value (e.g., 7.4 for PBS) using concentrated acid (e.g., HCl) or base (e.g., NaOH). Note that the pH may shift slightly after filtration and degassing.

Filtration Protocol

The following workflow details the steps for sterilizing and clarifying the buffer solution using a 0.22 µm filter.

4.2.1 Pre-wetting (for hydrophilic membranes): Pre-wet the PES filter membrane by passing a small volume (e.g., 5-10 mL) of ultrapure water through it. This eliminates air bubbles within the membrane matrix and ensures a consistent, high flow rate during the main filtration process [25] [27].

4.2.2 Filtration Assembly and Execution: Aseptically assemble the filtration apparatus, connecting the vacuum pump to the filter flask. Pour the prepared buffer into the filter funnel. Apply a gentle vacuum to drive the solution through the membrane. Avoid using excessive pressure, as this can compromise the integrity of the membrane. The resulting filtrate is now sterile and ready for degassing.

Buffer Degassing

Dissolved gases in the running buffer are a primary cause of air bubble formation in SPR microfluidics, leading to significant signal noise and data artifacts.

4.3.1 Sonication Method:

- Transfer the filtered buffer into a glass bottle, leaving sufficient headspace.

- Place the bottle in a sonication bath and sonicate for 15-30 minutes. Gentle stirring or agitation during sonication enhances gas removal.

4.3.2 In-line Degassing (Preferred):

- For instruments equipped with an in-line degasser, this is the recommended method.

- It provides continuous and on-demand degassing immediately before the buffer enters the fluidic system, which is the most effective approach for preventing bubble formation [28].

Quality Control and Storage

- Inspection: Visually inspect the final buffer for any cloudiness or particulate matter. The solution should be clear.

- pH Verification: Re-check and record the pH of the degassed buffer.

- Storage: Store the prepared buffer in a tightly sealed, sterile container at room temperature or as required by the specific buffer formulation. It is recommended that freshly prepared buffer be used within a short period (e.g., 24-48 hours) to prevent microbial growth or chemical degradation.

Integration with SPR Instrument Maintenance

Proper buffer preparation is intrinsically linked to the long-term health of the SPR instrument. The use of freshly prepared, degassed, and detergent-free running buffer is explicitly recommended as part of routine instrument maintenance to prevent the accumulation of contaminants within the fluidic path [5]. Furthermore, a clean fluidic system supplied with high-quality buffer is a prerequisite for successful pre-concentration screening and other sensitive immobilization techniques that optimize the sensor surface for ligand binding studies [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 4: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Flow Rate / Clogging | High particulate load in initial buffer. | Pre-filter the solution through a 0.45 µm or 1.0 µm filter before using the 0.22 µm filter [25] [27]. |

| Air Bubbles in Fluidics | Inadequate degassing. | Extend sonication time, ensure in-line degasser is functioning, or let buffer equilibrate to room temperature before use. |

| High Baseline Noise | Contaminated buffer or dirty fluidics. | Prepare fresh buffer, ensure all equipment is clean, and run instrument desorb and sanitize procedures [5]. |

| pH Drift | Buffer instability or CO₂ absorption. | Prepare buffer fresh, use tight-sealing containers, and consider the chemical stability of the buffer chosen. |

Within Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensing, the quality of running buffer is a foundational element dictating data integrity. SPR detects minute changes in refractive index at a sensor surface, making it highly susceptible to artifacts caused by air bubbles or particulate matter in the buffer [14] [20]. Proper buffer preparation, specifically filtration and degassing, is therefore not a mere preliminary step but a critical experimental variable that directly influences baseline stability, signal-to-noise ratio, and the reliability of derived kinetic parameters [5] [14]. This application note provides detailed protocols and best practices for buffer degassing, framed within a broader research context on optimizing SPR running buffer preparation to enhance research reproducibility.

The Critical Role of Degassing in SPR

Air bubbles represent a primary failure mode in SPR experiments. Small air bubbles entrapped in buffer can form within the microfluidic flow channels of the instrument. At low flow rates (< 10 µL/min), these bubbles are not efficiently flushed out and can grow, causing sudden spikes in the sensorgram that obscure the binding data [14]. Furthermore, buffers stored at 4°C contain more dissolved air, which is released as the buffer warms to experimental temperature, creating a significant risk of bubble formation [11]. The consequences of inadequate degassing include:

- Data Corruption: Spikes and drifts can make kinetic analysis impossible [14].

- Experimental Halt: Severe bubbles can block fluidic paths, requiring manual intervention and cleaning.

- Reduced Reproducibility: Fluctuating baselines introduce variability, compromising the reliability of binding affinities (KD) and rate constants (ka, kd) [11].

Degassing mitigates these risks by reducing the dissolved air content, thereby minimizing the potential for bubble nucleation and growth under the controlled temperature and flow conditions of an SPR assay.

Core Principles and Protocols for Buffer Preparation

A robust buffer preparation routine is the first step toward superior SPR data. The following workflow integrates filtration and degassing into a single, cohesive protocol. Adherence to strict buffer hygiene is paramount; it is considered "bad practice to add fresh buffer to the old" as microbial growth or chemical contamination can occur [14] [11].

The following diagram outlines the logical sequence and decision points in the SPR running buffer preparation workflow:

Comprehensive Degassing Techniques

Vacuum Degassing

Vacuum degassing is a common laboratory method where a buffer solution is placed under a vacuum, which lowers the partial pressure of dissolved gases, encouraging them to come out of solution.

Procedure:

- Pour the filtered buffer into a clean, heat-resistant glass flask. Do not fill more than halfway to allow for vigorous bubbling.

- Place the flask on a magnetic stirrer and add a clean stir bar.

- Seal the flask with a stopper connected to a vacuum line. Incorporate a cold trap between the flask and the vacuum source to prevent buffer vapor from entering the pump.

- Begin stirring at a moderate rate. Gradually apply vacuum until the buffer begins to bubble vigorously as gases evolve.

- Maintain this vacuum for 20-30 minutes. The process is complete when the evolution of fine bubbles substantially decreases.

- Slowly release the vacuum to avoid violent bubbling that can re-introduce air.

Optimal Duration: While the exact duration can depend on buffer volume and composition, a period of 20-30 minutes is generally effective for standard aqueous buffers like PBS or HBS-EP [14] [30]. Continuously monitor the solution; extended degassing beyond this point typically offers diminishing returns.

In-line Degassing and Helium Sparging

Many modern SPR systems, such as the Octet SF3, feature in-line degassers that actively remove gases from the buffer immediately before it enters the fluidic system, preventing air bubble formation during operation [28]. This is highly effective for the running buffer but does not degas the sample.

For systems without in-line degassing or for samples, helium (He) sparging is an excellent alternative. Helium has very low solubility in aqueous solutions, and when bubbled through the buffer, it displaces more soluble gases like nitrogen and oxygen [30].

- Procedure:

- Use a disposable, sterile filter (0.22 µm) on the helium inlet line to maintain sterility.

- Submerge the tip of the helium line in the buffer and set the gas flow to a gentle, continuous stream of bubbles. Avoid a violent flow that could cause foaming, especially if detergents are present.

- Sparge intensively for an initial 5-minute period to remove the bulk of dissolved air [30].

- For storage, reduce the helium flow to a minimal rate to maintain a positive pressure of inert gas over the buffer, or simply maintain a "He blanket" [30].

Buffer Selection and Handling

The composition of the buffer itself influences degassing efficacy and baseline stability.

Table 1: Buffer Handling and Degassing Considerations

| Buffer Type | Key Characteristics | Degassing & Handling Notes | Common SPR Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Buffers (e.g., PBS, HBS) | Low viscosity, high volatility for volatile additives. | Standard 20-30 min vacuum degassing. Volatile components may evaporate; sparge time may need optimization. | General protein-protein interactions, antibody-antigen binding. |

| DMSO-Containing Buffers | High refractive index, prone to evaporation. | Critical to match running and sample buffer DMSO concentration [14]. Evaporation changes concentration, causing large bulk shifts. | Small molecule screening where solubility requires DMSO. |

| High-Salt Buffers | Can increase solution viscosity. | Ensure complete dissolution before degassing. Risk of salt precipitation if stored cold; store at room temperature [11]. | Studies involving ionic strength dependence, DNA-protein interactions. |

Troubleshooting Common Buffer-Related Issues

Even with careful preparation, issues can arise. The table below outlines common symptoms, their likely causes, and corrective actions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Buffer-Related SPR Issues

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent spikes in the sensorgram [14] | Air bubbles from inadequately degassed buffer; bubbles growing at low flow rates. | Re-degas buffer thoroughly. Increase flow rate temporarily to flush system. Ensure buffers stored at room temp, not 4°C [11]. |

| Baseline drift after docking chip or buffer change [11] | System not equilibrated; temperature difference; mixing of old and new buffer in lines. | Prime system multiple times after buffer change. Equilibrate a new sensor chip in running buffer for up to 12 hours [5]. |

| Bulk refractive index shift (jump at injection start/end) [14] | Mismatch between running buffer and analyte buffer (e.g., different salt, DMSO, glycerol content). | Dialyze analyte into running buffer. Use size-exclusion columns for buffer exchange. For DMSO, include the same concentration in the running buffer [14]. |

| Carry-over or contamination [14] | Old or contaminated buffer; microbial growth. | Prepare fresh buffers daily. Never top off old buffer with new. Use clean, sterile bottles. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Preparation

| Item | Function in SPR Buffer Prep |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | The solvent base for all buffers; must be of high purity (e.g., 18 MΩ·cm) to minimize contaminants. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., HEPES, PBS components) | Maintain a stable pH and ionic strength to preserve biomolecule activity and interaction fidelity. |

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | Added after filtration and degassing to reduce nonspecific binding to the sensor chip and fluidics. Pre-filtration addition can cause foam [14] [11]. |

| 0.22 µm Membrane Filter | Removes particulate matter that could clog the instrument's microfluidic channels. |

| Vacuum Pump & Filter Flask | Standard apparatus for vacuum degassing of buffer solutions prior to use. |

| Helium Gas Tank & Sparging Line | Used for helium sparging, an effective method for degassing and maintaining an inert atmosphere over the buffer. |

Meticulous preparation and degassing of running buffers are non-negotiable prerequisites for robust and reproducible SPR data. There is no universal "one-size-fits-all" vacuum duration; rather, 20-30 minutes of vacuum degassing serves as a reliable starting point for most aqueous buffers, while 5 minutes of initial helium sparging is effective for in-process degassing. The most critical factor is consistency—maintaining strict buffer hygiene, precisely matching the composition of running and sample buffers, and systematically implementing the described protocols. Integrating these degassing techniques as a core component of SPR experimental design will significantly minimize artifacts, reduce wasted time and reagents, and enhance the confidence in the derived kinetic and affinity constants that are vital to drug development and basic research.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis, the integrity of binding data is profoundly influenced by the chemical composition of the running buffer. Buffer mismatch between the analyte sample and the SPR running buffer can introduce significant refractive index changes, leading to bulk shift effects that obscure genuine binding signals and compromise kinetic measurements [31]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, achieving perfect buffer matching is not merely a preparatory step but a foundational requirement for generating publication-quality binding affinities and kinetics.

Buffer exchange via desalting columns offers a rapid and efficient method to transfer an analyte into the exact SPR running buffer, eliminating matrix-induced artifacts. This application note details a robust protocol for implementing gel filtration-based desalting columns into SPR sample preparation workflows. The content is framed within a broader research context on optimizing SPR running buffer preparation and degassing, emphasizing practical steps to ensure data accuracy and reliability.

The Critical Role of Buffer Matching in SPR

The principle of SPR detection is based on measuring changes in the refractive index at a sensor surface [8]. When an analyte is dissolved in a buffer that differs in composition from the SPR running buffer—even slightly in salt concentration, pH, or additives like glycerol or DMSO—the difference in refractive index between the two solutions causes a sharp, bulk response upon injection [31] [8]. This response is distinct from a specific binding event and can manifest as a large injection peak or an unstable baseline, complicating or even preventing accurate data interpretation.

- Minimizing Bulk Shift Effects: The primary goal of buffer exchange is to make the analyte's solution matrix (its buffer) identical to the SPR running buffer. This ensures that any change in the SPR signal (Response Units, RU) during analyte injection is due solely to molecular binding at the sensor surface, and not from a difference in the solution's composition [31].

- Preserving Analyte Activity: The use of size-exclusion based desalting columns is a gentle process that maintains the native structure and activity of proteins and other biomolecules, which is crucial for obtaining biologically relevant binding data [32] [33].

- Compatibility with Additives: Many small molecule analytes require DMSO for solubility. It is critical to match the concentration of DMSO in the running buffer and all analyte samples to prevent significant baseline distortions [31]. Desalting columns efficiently remove and exchange buffers while being compatible with a range of biological samples.

Technical Principles of Desalting Columns

Desalting columns, also known as spin desalting columns or gel filtration columns, operate on the principle of size exclusion chromatography (SEC) [33]. The column is packed with porous resin beads, and the separation process is based on molecular size:

- Macromolecules (e.g., proteins, peptides) are too large to enter the pores of the resin. They flow around the beads and elute from the column first, in the void volume.

- Small molecules (e.g., salts, detergents, impurities, old buffer constituents) can enter the pores, which increases their path length and slows their progress through the column. They elute later, separated from the macromolecules [33].

For buffer exchange, the column resin is pre-equilibrated with the desired destination buffer (e.g., the SPR running buffer). As the sample passes through the column, the larger analyte is collected in this new buffer, effectively achieving a rapid and efficient buffer exchange [33].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating desalting columns into the SPR sample preparation process, from initial buffer preparation to the final SPR experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents required for successful buffer exchange and subsequent SPR analysis.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Analyte Preparation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Spin Desalting Columns | Gel filtration columns for rapid buffer exchange and desalting of protein/peptide samples. | AdvanceBio Spin Columns [32], Zeba Spin Desalting Columns [33] |

| SPR Running Buffer | The continuous phase for SPR analysis; must be matched by the analyte buffer. Common buffers include HBS-EP, PBS, or HEPES-KCl [19] [8]. | GE Healthcare (HBS-EP) [19], Laboratory preparation [8] |

| Ultrapure Water | Used for preparing buffer solutions; 18 MΩ resistivity at 25°C is recommended to minimize contaminants [8]. | Milli-Q Advantage A10 System [19] |

| Salts & Reagents | For buffer preparation (e.g., HEPES, NaCl, KCl). | Sigma-Aldrich [19] |

| Detergents | Added to running buffer (e.g., Tween-20) to reduce non-specific binding [19]. | Sigma-Aldrich [19] |

| DMSO | Organic solvent for dissolving small molecule analytes; concentration must be matched in all solutions [31]. | Sigma-Aldrich [19] |

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of desalting columns is characterized by high protein recovery and efficient removal of small molecules. The following table summarizes typical performance metrics as established in the literature and commercial product data.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Desalting Columns for Sample Preparation

| Parameter | Typical Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Recovery | >90% | Recovery of BSA demonstrated using Zeba Spin Desalting Columns across a concentration range of 0.04-1 mg/mL [33]. |

| Sample Volume | 2 µL to 4+ mL | Various commercial column formats are available to process a wide range of sample volumes [33]. |

| Molecular Weight Cutoff (MWCO) | ~7,000 Da | A common MWCO for spin columns, designed to retain proteins while excluding salts and small molecules [33]. |

| Processed Volume | 1.5 - 3.5 mL | Sample volumes of BSA successfully desalted with high recovery [33]. |

| Time Efficiency | Minutes per sample | Spin column procedures are designed for rapid processing, typically involving a short centrifugation step [32] [33]. |

Experimental Protocol: Buffer Exchange for SPR Analytes

This protocol describes the step-by-step procedure for exchanging the buffer of an analyte sample into an SPR running buffer using spin desalting columns.

Pre-Experiment Preparation

- Prepare and Degas Running Buffer: Prepare the SPR running buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% Tween-20, pH 7.4) [19] [8]. Degas the buffer thoroughly using a vacuum pump to prevent air bubble formation in the SPR microfluidic system during the experiment [19].

- Select the Desalting Column: Choose a spin desalting column with a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) significantly lower than the molecular weight of your analyte to ensure its retention. Ensure the column size is appropriate for your sample volume [33].

Buffer Exchange Procedure

Column Equilibration:

- Resuspend the resin in the column by gently vortexing or tapping the tube.

- Remove the top cap and then the bottom cap of the column.

- Place the column in a clean 2 mL microcentrifuge tube (provided with most kits) and centrifuge at 1,000 × g for 1 minute to remove the storage solution.

- Discard the flow-through. Apply the degassed running buffer (approximately the same volume as the column's bed capacity) to the column.

- Centrifuge again at 1,000 × g for 1 minute and discard the flow-through.

- Repeat this equilibration step a second time. A properly equilibrated column is critical for effective buffer exchange.