Solving SPR Baseline Drift After Buffer Change: A Complete Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) baseline drift following buffer changes.

Solving SPR Baseline Drift After Buffer Change: A Complete Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) baseline drift following buffer changes. It covers the fundamental causes of drift, including system equilibration issues and buffer mismatches, and offers detailed methodological protocols for buffer preparation and system priming. The content delivers advanced troubleshooting strategies to correct and prevent drift, alongside validation techniques like double referencing to ensure data integrity. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical application, this guide empowers scientists to achieve stable baselines and generate high-quality, reproducible SPR data for critical drug discovery and biomolecular interaction studies.

Understanding the Root Causes of SPR Baseline Drift

Defining Baseline Drift and Its Impact on Data Quality

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for monitoring biomolecular interactions in real time. The quality of the data it produces is paramount, and a stable baseline is a critical prerequisite for obtaining reliable kinetic and affinity constants. Baseline drift, defined as a gradual, unidirectional shift in the response signal when no active binding occurs, is a common phenomenon that can significantly compromise data integrity. This technical guide defines baseline drift, details its root causes—with a specific focus on buffer changes—and provides validated experimental protocols for its mitigation within the context of advanced drug discovery research.

In SPR, a sensorgram plots the resonance response (in Resonance Units, RU) against time, providing a real-time record of binding events. The baseline is the stable signal region before any analyte injection, serving as the critical reference point from which all binding-induced response changes are measured [1].

Baseline drift is a persistent deviation from this stable state, manifesting as a gradual increase or decrease in the signal when only running buffer is flowing over the sensor chip [2] [3]. Its impact on data quality is profound. Drift can lead to inaccurate quantification of binding responses, distort the calculation of association and dissociation rates, and ultimately result in erroneous affinity constants (KD). These inaccuracies can misdirect lead optimization in pharmaceutical development and invalidate crucial research findings.

Root Causes and Identification of Drift

A systematic approach to troubleshooting baseline drift begins with identifying its underlying cause. The following table summarizes the primary culprits, their characteristics, and diagnostic signatures.

Table 1: Common Causes and Identification of Baseline Drift

| Category | Specific Cause | Manifestation in Sensorgram | How to Identify |

|---|---|---|---|

| System & Buffer Issues | Inadequate buffer equilibration after a change [2] | Sustained, unidirectional drift after buffer switch. | Prime system repeatedly; observe if drift persists. |

| Poor buffer hygiene (microbial growth, contaminants) [2] | Unstable baseline with increased noise. | Prepare fresh, filtered (0.22 µm), and degassed buffer daily. | |

| Buffer-component incompatibility [3] | Drift or sudden baseline shifts. | Check for precipitates; switch to a compatible buffer. | |

| Sensor Surface Issues | Improperly equilibrated or hydrated sensor chip [2] | Drift immediately after docking a new chip or after immobilization. | Flow running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surface. |

| Slow ligand stabilization post-immobilization [2] | Drift that levels out over 5-30 minutes after flow start. | Incorporate start-up cycles with buffer injections. | |

| Experimental Procedure | Inefficient surface regeneration [3] | Progressive, step-wise baseline shift after each regeneration. | Test different regeneration buffers; ensure complete analyte removal. |

| Start-up drift after flow standstill [2] | Initial drift that stabilizes after several minutes of buffer flow. | Wait for a stable baseline (5-30 min) before analyte injection. |

A critical and common scenario is baseline drift following a buffer change. This occurs when the previous buffer mixes with the new one within the fluidics system, creating a refractive index gradient. Failing to equilibrate the system adequately post-change results in a "waviness pump stroke" pattern in the baseline until mixing is complete and a new equilibrium is established [2].

Impact of Drift on Data Analysis

Baseline drift introduces systematic errors that propagate through data analysis. Its primary impacts include:

- Inaccurate Response Measurement: The binding response (ΔRU) is measured from the baseline. A drifting baseline means the starting point for this calculation is incorrect, leading to over- or under-estimation of the bound analyte mass [1].

- Distorted Kinetic Analysis: The calculation of association (

k_on) and dissociation (k_off) rate constants relies on the precise shape of the sensorgram. A drifting baseline during the dissociation phase, for instance, can make a slow-dissociating complex appear even slower or non-dissociating, falsely suggesting a higher-affinity interaction. - Compromised Affinity Constants: Since the equilibrium dissociation constant (

K_D) is derived from the ratio of the rate constants (k_off/k_on) or from steady-state analysis, errors in kinetics directly translate to erroneousK_Dvalues.

Advanced data analysis software, such as the Genedata Screener module, incorporates preprocessing functions like baseline adjustment to align traces to a common baseline of y=0 prior to the first injection. Furthermore, double referencing—subtracting both a reference surface signal and a blank (buffer) injection—is a fundamental data processing technique to compensate for residual drift and bulk effects [2] [4].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Drift

A proactive experimental design is the most effective strategy to prevent baseline drift.

Protocol for Buffer Preparation and System Equilibration

This protocol is critical, especially after any buffer change [2].

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare running buffer fresh daily. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter into a sterile bottle to remove particulates and microbes. Degas the filtered buffer to prevent the formation of air bubbles ("air-spikes") in the fluidics.

- System Priming: After changing the buffer reservoir, prime the instrument's fluidic system multiple times with the new buffer. This ensures the previous buffer is completely purged from all tubing and the integrated fluidic cartridge (IFC).

- Baseline Stabilization: Flow the running buffer at the experimental flow rate while monitoring the baseline. A stable baseline, typically with fluctuations of less than 1-2 RU over 5-10 minutes, indicates the system is equilibrated. This may take 5-30 minutes or longer, depending on the system and sensor chip history.

Protocol for Incorporating Start-up and Blank Cycles

This protocol uses the experiment's own method to stabilize the system before critical data collection begins [2].

- Start-up Cycles: Program the instrument method to include at least three initial "dummy" cycles. These cycles should replicate the experimental cycle exactly but inject running buffer instead of analyte. If a regeneration step is used, include it.

- Blank Injections: Space blank injections (running buffer only) evenly throughout the experiment, approximately one blank for every five to six analyte cycles, and include one at the end.

- Data Analysis: Exclude the start-up cycles from final analysis. Use the blank injections during data processing to perform double referencing, which corrects for any remaining drift and bulk refractive index effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Managing Drift

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Baseline Stability

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Managing Baseline Drift |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffers (e.g., HEPES, PBS) | Provides a consistent chemical environment. Prevents drift caused by pH shifts or contaminants. Must be 0.22 µm filtered and degassed [2] [5]. |

| Detergents (e.g., Tween-20) | Added to running buffer (typically 0.05%) to reduce non-specific binding to the sensor surface and fluidics, a potential source of drift [2] [3]. |

| Regeneration Solutions (e.g., Glycine-HCl pH 2.0-3.0) | Efficiently removes bound analyte without damaging the ligand. Prevents cumulative baseline drift due to incomplete regeneration between cycles [3] [6]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Used to cap unused active sites on the sensor surface after ligand immobilization, minimizing a common source of non-specific binding and subsequent drift [3]. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, HC30M) | The foundation of the assay. A clean, well-hydrated, and compatible sensor chip is essential for a stable baseline [3] [6]. |

Advanced Data Processing Algorithms

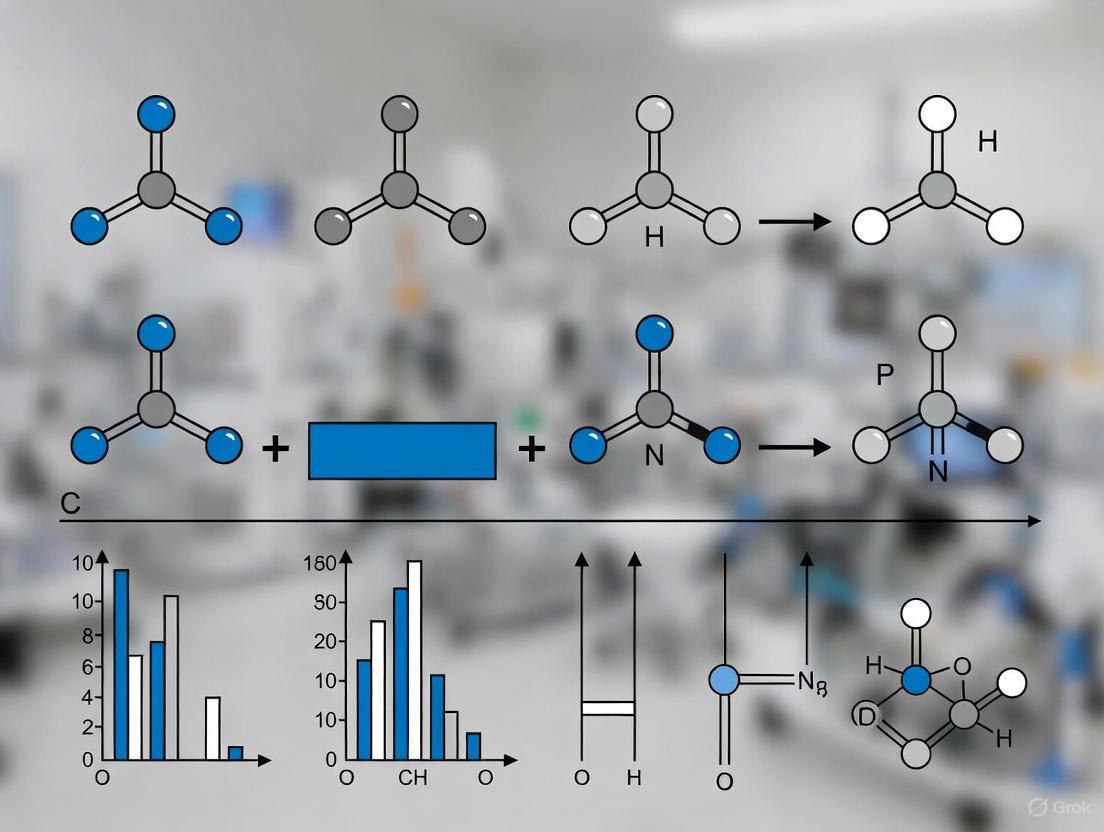

Beyond experimental best practices, advanced data processing algorithms can help correct for drift. One such method is the Dynamic Baseline Algorithm [7]. This algorithm dynamically adjusts the baseline (P_B in the centroid calculation method) for each SPR curve based on a pre-defined ratio (R_0) between the integrated areas of the SPR curve below and above the baseline. This adjustment compensates for fluctuations in optical power and background signal, making the final output (θ_res) insensitive to these instrumental drifts. The relationship is defined by:

P_B is adjusted to satisfy: ∫[P_B - P(θ)]dθ / ∫[P(θ) - P_B]dθ = R_0

This algorithm is mathematically simple to implement and can be combined with standard data analysis methods like the centroid method or polynomial curve fitting to enhance robustness against correlated noise and drift [7].

Baseline drift in SPR is more than a minor inconvenience; it is a significant threat to data quality that can derail scientific conclusions and drug discovery decisions. Its root causes are well-understood, often stemming from suboptimal system equilibration, particularly after buffer changes, or unstable sensor surfaces. As detailed in this guide, a combination of rigorous experimental protocols—including meticulous buffer preparation, systematic priming, and the use of start-up cycles—provides a robust defense. Furthermore, modern data analysis techniques, from double referencing to advanced dynamic baseline algorithms, offer powerful tools to correct for residual drift. For the researcher, a disciplined focus on baseline stability is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental requirement for generating publication-quality, reliable SPR data.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) has emerged as a powerful, label-free technology for real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions, providing valuable insights into kinetics, affinity, and specificity for researchers in biochemistry, biophysics, and drug development [8]. Despite its sophisticated capabilities, SPR technology remains vulnerable to a fundamental experimental challenge: baseline drift after buffer changes. This phenomenon represents a significant source of data inaccuracy, particularly affecting the precision of kinetic measurements and affinity calculations.

Baseline drift following buffer modification is not merely an instrumental artifact but primarily a consequence of inadequate system equilibration [2]. When a new buffer is introduced to the fluidic system without proper equilibration procedures, the previous buffer mixes with the incoming solution, creating refractive index gradients and unstable hydrodynamic conditions. The resulting "waviness pump stroke" effect manifests as baseline instability that can persist for multiple pump cycles until the system fully stabilizes [2]. For researchers investigating small molecule interactions or conformational changes where signal changes may be minimal, uncompensated drift can severely compromise data integrity, leading to erroneous conclusions about molecular binding events.

This technical guide examines the critical role of system equilibration in mitigating buffer-induced baseline drift, providing experimental protocols and quantitative frameworks to enhance data quality in SPR-based research.

Understanding Baseline Drift: Mechanisms and Impact

Physicochemical Origins of Buffer-Induced Drift

Baseline drift following buffer changes originates from multiple interrelated physicochemical processes occurring within the SPR microfluidic environment:

- Refractive Index Incompatibility: Differential refractive indices between displaced and incoming buffers create transient optical inhomogeneities at the sensor surface-a critical concern given SPR's fundamental dependence on refractive index measurements [8].

- Temperature Dissipation: Buffer solutions at different temperatures establish microthermal gradients across the sensor surface, modifying the local refractive index through the thermo-optic effect.

- Surface Rehydration Dynamics: Sensor surfaces, particularly newly docked chips or those recently regenerated with harsh solutions, undergo rapid rehydration when exposed to aqueous buffers, creating substantial baseline displacement until hydration equilibrium is achieved [2].

- Chemical Equilibration: Immobilized ligands and sensor surface chemistries require time to establish stable interfacial properties with new buffer compositions, including ion distribution, pH stabilization, and detergent adsorption.

Impact on Data Quality and Kinetic Parameters

The consequences of inadequate equilibration extend beyond visual artifacts in sensorgrams. Kinetic analysis software frequently misinterpret drifting baselines as ongoing association or dissociation events, substantially altering calculated rate constants. For low-affinity interactions or small molecule binding studies where signal changes may be marginal relative to drift amplitude, the resulting affinity constants (KD values) may contain significant errors that undermine experimental conclusions.

Experimental Protocols for Optimal System Equilibration

Comprehensive Buffer Preparation and Handling

Proper buffer management forms the foundation of effective system equilibration and drift minimization:

- Daily Buffer Preparation: Prepare fresh buffers daily and filter through 0.22 µM membranes to remove particulate contaminants that contribute to optical noise and non-specific binding [2].

- Degassing Protocol: Degas buffers thoroughly before use to eliminate microbubbles that create spike artifacts and baseline instability. Note that buffers stored at 4°C contain higher dissolved gas concentrations that nucleate upon warming [2].

- Buffer Introduction Technique: Avoid adding fresh buffer to existing solutions, as "all kind of nasty things can happen/growing in the old buffer" [2]. Completely replace buffer reservoirs with freshly prepared solutions.

- Detergent Addition: Introduce appropriate detergents after filtering and degassing to prevent foam formation that introduces air-liquid interfaces into the fluidic path.

Systematic Equilibration Procedures

Implement these structured protocols to ensure complete system equilibration after buffer changes:

- Priming Sequence: Prime the system multiple times after each buffer change to thoroughly replace the previous solution throughout the entire fluidic path [2] [9].

- Flow-Through Equilibration: Following priming, flow running buffer at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained. This may require 5-30 minutes depending on sensor type and immobilized ligand [2].

- Start-Up Cycles: Incorporate at least three start-up cycles in experimental methods that mimic analyte injections but use buffer only. These "dummy" cycles precondition the surface and identify stabilization requirements before actual sample analysis [2].

- Extended Dissociation Monitoring: When system stabilization is problematic, implement short buffer injections followed by five-minute dissociation periods to establish stable baselines before analyte introduction [2].

Table 1: Equilibration Parameters for Common SPR Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | Minimum Equilibration Time | Recommended Flow Rate | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Buffer Change | 5-15 minutes | Experimental flow rate | Buffer refractive index, temperature |

| After Sensor Chip Docking | 30+ minutes | 10-30 µL/min | Surface rehydration, temperature stabilization |

| Post-Immobilization | 30 minutes to overnight | 5-10 µL/min | Ligand stabilization, wash-out of chemicals |

| After Regeneration | 10-20 minutes | Experimental flow rate | pH equilibration, surface charge stabilization |

| High-Sensitivity Measurements | 20-30 minutes | Low flow rate (5-10 µL/min) | Thermal stability, minimal vibrations |

Advanced Equilibration Monitoring and Quality Control

For precise quantification applications, implement these enhanced equilibration verification procedures:

- Noise Level Assessment: After apparent equilibration, inject running buffer multiple times and observe the average baseline response. Acceptable noise levels should be < 1 RU for high-quality instruments [2].

- Drift Rate Calculation: Monitor baseline position over a 5-minute period after equilibration. Drift rates should not exceed 0.5 RU/minute for kinetic studies of small molecule interactions.

- Reference Channel Alignment: Compare baseline stability between active and reference channels. Significant differential drift indicates surface-specific equilibration issues requiring additional stabilization time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SPR Equilibration Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function in Equilibration | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 µM Filters | Removes particulate contaminants causing optical noise | Use cellulose acetate or PVDF membranes compatible with buffer systems |

| Buffer Degassing Apparatus | Eliminates dissolved gases that form microbubbles | In-line degassers preferred for continuous flow systems |

| Detergents (e.g., Tween-20) | Reduces non-specific binding and surface adsorption | Add after filtering and degassing to prevent foam formation [2] |

| Ethanolamine | Blocks unused coupling sites on sensor surface | Standard blocking agent after covalent immobilization |

| CM5 Sensor Chips | Versatile dextran matrix for diverse immobilization | Most common chip type; requires thorough hydration |

| NTA Sensor Chips | Specific capture of His-tagged proteins | Requires nickel saturation stabilization |

| SA Sensor Chips | Streptavidin surface for biotinylated ligands | High binding affinity necessitates extended equilibration |

| Regeneration Solutions | Removes bound analyte while preserving ligand activity | Must be thoroughly washed out to prevent baseline effects |

Integrated Workflow for Drift Minimization

Data Analysis and Drift Compensation Strategies

Double Referencing Methodology

Even with meticulous equilibration, minimal drift may persist. The double referencing technique provides a powerful computational approach to compensate for residual baseline effects:

- Primary Referencing: Subtract the reference channel response from the active channel to compensate for bulk refractive index effects and instrumental drift [2].

- Blank Subtraction: Subsequently subtract blank injections (buffer alone) from the referenced data to correct for differences between reference and active channels [2].

- Optimal Blank Spacing: Distribute blank injections evenly throughout the experiment, approximately one blank every five to six analyte cycles, concluding with a final blank measurement [2].

Quantitative Drift Assessment and Acceptance Criteria

Establish laboratory-specific criteria for acceptable drift levels based on experimental objectives:

- Kinetic Studies: For accurate kinetic parameter determination, drift rates should not exceed 0.3 RU/minute during association and dissociation phases.

- Affinity Measurements: Steady-state affinity analysis tolerates slightly higher drift (up to 1 RU/minute) provided the baseline trend remains linear.

- Qualitative Binding: Screening applications may accept drift rates up to 2 RU/minute when establishing binding presence versus absence.

Table 3: Quantitative Drift Parameters and Their Experimental Implications

| Drift Parameter | Acceptable Range | Impact Outside Range | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drift Rate | < 0.5 RU/min | Erroneous kinetic rate constants | Extend equilibration, check temperature control |

| Noise Level | < 1.0 RU | Reduced signal-to-noise ratio | Improve buffer filtering, stabilize temperature |

| Step Artifacts | < 2.0 RU | Inaccurate Rmax determination | Eliminate bubbles, check for leaks |

| Differential Drift | < 0.3 RU/min | Ineffective referencing | Match reference surface, extend stabilization |

| Post-Injection Stabilization | < 3.0 RU shift | Incorrect baseline interpolation | Increase dissociation time, add wash steps |

Technological Innovations in Drift Reduction

Recent advancements in SPR instrumentation and sensor design demonstrate promising approaches to minimizing equilibration-related challenges:

Hybrid Sensor Architectures

Novel sensor designs integrate complementary transduction mechanisms to compensate for drift artifacts. The extended-gate organic thin-film transistor (ExG-OTFT) with SPR readout spatially separates the sensing surface from the transistor body, significantly improving system reliability [10]. This architecture maintains compatibility with commercial SPR instrumentation while incorporating a pseudo-reference electrode that enhances baseline stability during buffer exchanges.

Enhanced Surface Engineering

Advanced material stacks improve surface stability and reduce equilibration requirements. Multilayer architectures incorporating silver mirrors with silicon nitride (Si3N4) spacers and tungsten disulfide (WS2) capping layers demonstrate improved chemical passivation while concentrating the evanescent field at the recognition surface [11]. Such designs show reduced susceptibility to buffer-induced drift through controlled electromagnetic field confinement.

System equilibration stands as the fundamental determinant of SPR data quality following buffer changes. Through implementation of standardized buffer preparation protocols, systematic equilibration procedures, and comprehensive drift compensation strategies, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of kinetic and affinity measurements. The experimental frameworks presented in this technical guide provide actionable methodologies for achieving optimal baseline stability, enabling more accurate characterization of molecular interactions across diverse research and development applications.

As SPR technology continues evolving toward higher sensitivity and miniaturization, maintaining vigilance toward fundamental physicochemical processes such as system equilibration will remain essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from this powerful analytical platform.

The Role of Buffer Composition and Mismatches

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, the molecular interactions observed on the sensorgram are not only a reflection of biomolecular binding but are also profoundly sensitive to the physicochemical environment. The composition of the running buffer and the sample analyte buffer is a critical, though often underestimated, variable. In the specific context of investigating SPR baseline drift after buffer change, buffer mismatches emerge as a predominant source of significant experimental artifacts, including bulk shifts and negative response curves, which can obscure true kinetic data [12] [2]. A buffer mismatch of just 1 mM NaCl can induce a response jump of approximately 20 RU on a carboxylated dextran sensor chip, directly mimicking or distorting the binding signal of interest [12]. This technical guide details the mechanisms by which buffer composition influences SPR outputs and provides validated methodologies to identify, mitigate, and correct for these effects, ensuring the integrity of binding kinetics data.

Core Mechanisms: How Buffer Composition Impacts SPR Signals

The SPR signal is a measure of the refractive index at the sensor surface. Any change in the composition of the solution over the chip that alters the refractive index will be detected as a response change. Buffer mismatches introduce such changes systematically.

Bulk Refractive Index Shift and Volume Exclusion

The most common artifact arises from a difference in composition between the running buffer and the sample analyte buffer. When the sample is injected, the differing buffer properties cause a shift in the refractive index across the entire sensor surface—a bulk effect [13]. This shift is typically uniform across active and reference surfaces and can be partially corrected via reference subtraction.

A more complex phenomenon is volume exclusion [12]. The immobilized ligand occupies physical space within the dextran matrix. Surfaces with different ligand densities present different volumes to the solvent. When the buffer changes, the matrix can swell or shrink depending on the new buffer's properties. Because the reference and active surfaces have different ligand densities, they swell or shrink to different degrees, leading to a differential response after reference subtraction. This effect is particularly pronounced with additives like DMSO or glycerol [12].

Ionic Strength and pH Effects

- Ionic Strength: Low ionic strength analyte solutions injected into a higher ionic strength running buffer cause a negative jump in the response [12]. This is due to the change in the local ionic environment affecting the plasmon wave.

- pH: Changes in pH can alter the charge state of the immobilized ligand and the dextran matrix, leading to swelling or contraction of the matrix and changes in the observed response.

Consequences of Buffer Mismatches

These effects manifest in several ways on the sensorgram:

- Positive or Negative Response Jumps: Sudden shifts in the baseline at the start and end of injection [12].

- Negative Binding Curves: After reference subtraction, the signal from the active channel may be lower than the reference, resulting in a negative curve. This often indicates that the reference surface is more affected by the buffer change or has higher non-specific binding than the active surface [12].

- Baseline Drift: Improper buffer equilibration is a primary cause of baseline instability. Fresh buffers must be filtered and degassed daily to prevent air spikes and drift, and the system must be thoroughly primed after a buffer change [2].

Table 1: Common Buffer Components and Their Impact on SPR Signals

| Buffer Component | Primary Effect on SPR Signal | Typical Artifact | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salts (NaCl, etc.) | Alters ionic strength and refractive index [12] | Negative jump (low salt), positive jump (high salt) | Dialyze analyte into running buffer |

| DMSO | High refractive index, affects matrix volume [12] | Large positive bulk shift, volume exclusion effects | Use calibration injections for correction [12] |

| Glycerol/Sucrose | Increases viscosity and refractive index [12] | Positive bulk shift, volume exclusion | Match running and sample buffer concentrations |

| Detergents (P20, Tween-20) | Reduces non-specific binding [14] | Altered baseline if mismatched | Include in running buffer at consistent low concentration (e.g., 0.005%) |

| BSA/CM-Dextran | Blocks non-specific sites on the matrix [12] [14] | Can reduce drift and negative responses | Add to running buffer (0.1-1 mg/mL) |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Buffer Matching and Sample Preparation

Objective: To eliminate bulk effects caused by buffer mismatches.

- Dialysis: Dialyze the analyte preparation extensively against the running buffer. This is the most effective method to ensure identical buffer compositions.

- Desalting Columns: Use centrifugal desalting columns to exchange the analyte into the running buffer immediately before the experiment.

- Direct Dilution: If possible, prepare the analyte samples by diluting a stock solution directly into the running buffer. Avoid using different buffers for dilution.

Protocol 2: Assessing and Optimizing the Reference Surface

Objective: To create a reference surface that minimizes differential volume exclusion and non-specific binding.

- Test Surfaces: Inject a high concentration of analyte over multiple surfaces [12]:

- A native (unmodified) surface.

- A deactivated surface (activated with NHS/EDC and blocked with ethanolamine).

- A surface immobilized with a non-interacting protein (e.g., BSA or an irrelevant IgG).

- Evaluate Binding: Select the surface that shows the least non-specific binding of your analyte for use as the reference.

- Match Immobilization Levels: Immobilize the reference molecule to a level (in RU) similar to the active ligand surface to ensure comparable volume exclusion properties [12].

Protocol 3: Incorporating Blank and Calibration Injections

Objective: To empirically correct for residual buffer effects using double referencing.

- Blank Injections: Include injections of running buffer (blanks) interspersed throughout the experiment, ideally one blank for every five to six analyte injections [2].

- Calibration Injections: For additives like DMSO, perform a separate calibration series with injections containing only the additive at different concentrations (but no analyte) over both active and reference surfaces. Create a calibration plot to correct for the volume exclusion effect in the actual analyte sensorgrams [12].

- Data Processing: Apply double referencing during data analysis. First, subtract the reference channel data from the active channel data. Second, subtract the averaged signal from the blank injections [2].

Protocol 4: System Equilibration to Minimize Drift

Objective: To achieve a stable baseline following a buffer change.

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare fresh running buffer daily, filter through a 0.22 µm filter, and degas thoroughly [2].

- System Priming: After docking a new chip or changing the buffer, prime the system multiple times with the new running buffer.

- Start-up Cycles: Program the instrument to run at least three "start-up cycles" that mimic the experimental cycle (including regeneration if used) but inject only running buffer. Use these cycles to equilibrate the system before beginning data collection; do not include them in analysis [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Managing Buffer Effects

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| HBS-EP Buffer | A standard running buffer (HEPES, NaCl, EDTA, surfactant P20); provides a consistent ionic and chemical environment [14]. | Used as the primary running buffer in many SPR experiments to maintain stability and reduce non-specific binding. |

| Carboxymethyl (CM) Dextran | Added to running buffer to saturate non-specific binding sites on the dextran matrix, reducing non-specific analyte binding and negative curves [12]. | Used at 0.1 - 1 mg/mL in running buffer to pre-block the sensor chip surface. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A common blocking protein used to passivate the reference surface and reduce non-specific binding [12] [14]. | Immobilized on the reference channel or added to running buffer at 0.1-1 mg/mL. |

| Surfactant P20 | A non-ionic detergent that reduces non-specific hydrophobic interactions on the sensor surface [14]. | Standard component of HBS-EP buffer at 0.005% concentration. |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Used to deactivate and block unreacted groups on the sensor surface after amine coupling immobilization, ensuring a stable baseline [14]. | Injected after ligand immobilization to cap excess NHS-esters. |

Workflow and Data Analysis Visualization

The following workflow diagrams the process of diagnosing and resolving common buffer-related artifacts in SPR data.

Advanced Data Analysis and Bulk Shift Handling

In high-throughput analysis, sophisticated tools can programmatically handle bulk effects. For instance, the TitrationAnalysis tool, a Mathematica package for analyzing SPR and BLI data, incorporates mathematical handling of bulk shift signals [13]. The tool can fit sensorgrams to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model while accounting for the baseline shifts (Rshift_i and Rdrift_i in its equations) that often originate from buffer mismatches, ensuring more accurate estimation of association (k_a) and dissociation (k_d) rate constants [13].

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Common Buffer Mismatches

| Mismatch Type | Approximate Signal Change | Recommended Correction Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 mM NaCl | ~20 RU [12] | Dialysis of analyte into running buffer |

| Low Ionic Strength Analyte | Negative response jump [12] | Match ionic strength or use double referencing |

| DMSO/Glycerol Addition | Large positive response; differential volume exclusion [12] | Calibration plot and subtraction |

| pH Discrepancy | Swelling/shrinking of dextran matrix; signal drift | Dialysis into running buffer |

Buffer composition is a foundational element of robust SPR experimental design. Mismatches between the running buffer and sample buffer are not mere inconveniences; they are significant sources of artifacts that can compromise kinetic data interpretation. By understanding the mechanisms of bulk shift and volume exclusion, and by systematically implementing protocols for buffer matching, reference surface optimization, and data processing with double referencing, researchers can effectively control for these variables. A rigorous approach to buffer management ensures that the observed SPR signals accurately reflect the biomolecular interactions of interest, thereby enhancing the reliability of findings in drug discovery and basic research.

Sensor Surface Rehydration and Chemical Wash-Out

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free analytical technique used extensively in biochemical, biophysical, and drug development research for the real-time study of biomolecular interactions. A critical challenge in obtaining high-quality, reproducible SPR data is managing the stability of the instrumental baseline. This technical guide examines two fundamental, interconnected processes that are primary sources of baseline instability: sensor surface rehydration and chemical wash-out. These phenomena are particularly pronounced directly after docking a new sensor chip, following surface immobilization procedures, or after a change in the running buffer [2]. Within the context of a broader thesis on SPR baseline drift, understanding and mitigating these factors is paramount, as failing to do so results in sensorgrams with significant drift, complicating data analysis and leading to potentially erroneous kinetic and affinity determinations [2] [9].

This document provides an in-depth analysis of the underlying causes of these issues, summarizes quantitative data on contributing factors, outlines detailed experimental protocols for stabilization, and introduces visualization tools to guide researchers. The objective is to equip scientists with the knowledge and methodologies necessary to minimize baseline drift, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of their SPR-based research.

Core Mechanisms of Baseline Drift

Sensor Surface Rehydration

The sensor chip, particularly one with a dextran polymer matrix (e.g., CM5, CM4, CM7), is often stored in a dry or partially hydrated state. Upon initial exposure to the aqueous running buffer, the polymer matrix begins to absorb water and swell in a process known as rehydration [2]. This physical change in the matrix structure and density alters the refractive index (RI) in the immediate vicinity of the gold sensor surface, which is the very property SPR measures. The swelling is not instantaneous and can continue for an extended period, manifesting as a gradual downward or upward drift in the baseline signal until the hydrogel matrix is fully equilibrated with the buffer. This effect is also observed after the immobilization of a ligand, as the immobilized biomolecule itself adjusts to the flow buffer [2].

Chemical Wash-Out

Chemical wash-out refers to the gradual dissolution and removal of residual chemicals from the sensor surface and the fluidic system into the running buffer. These residues can originate from:

- Immobilization Reagents: Chemicals such as N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), and ethanolamine used in covalent coupling protocols [2].

- Storage Solutions: Preservatives or buffers in which sensor chips are stored.

- Regeneration Solutions: Harsh buffers (e.g., low or high pH, high salt, detergents) used to dissociate tightly bound analyte from the ligand between analysis cycles [9].

As these residual chemicals are washed away, they create a small but measurable change in the local refractive index at the sensor surface. Furthermore, if the running buffer and the buffer containing the chemical residues have different compositions, their mixing can cause RI fluctuations until the system is completely flushed and homogeneous [2].

Quantitative Impact and Stabilization Parameters

The time required for baseline stabilization is influenced by several experimental factors. The following table summarizes key parameters and their quantitative impact on the rehydration and wash-out processes.

Table 1: Factors Influencing Baseline Stabilization Time

| Factor | Impact on Stabilization | Typical Parameter Range | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip Type | Chips with thicker hydrogels (e.g., CM7) require longer rehydration than flat surfaces (e.g., C1, HPA). | Varies by chip (CM3, CM4, CM5, CM7, C1, L1) [15] | Allow longer equilibration for high-capacity dextran chips. |

| Ligand Immobilization Level | Higher density immobilization can prolong surface adjustment post-coupling. | N/A | Incorporate start-up cycles to "prime" the surface [2]. |

| Flow Rate | Lower flow rates prolong wash-out; higher rates can accelerate it but may introduce noise. | 10-100 µ/min | Use a constant, stable flow rate equivalent to the experiment's planned rate [2] [15]. |

| System Cleanliness | Contamination in tubing or from previous runs significantly extends wash-out. | N/A | Perform regular instrument cleaning and sanitization [16]. |

| Buffer Composition Change | Larger differences in salt concentration, pH, or additives between old and new buffers increase drift. | N/A | Prime the system multiple times after a buffer change [2]. |

The relationship between these factors and the resulting baseline stability can be visualized in the following workflow, which maps the causes of drift to their effects and primary mitigation strategies.

Figure 1. Workflow of baseline drift causes and mitigation. This diagram illustrates how common experimental triggers (yellow) lead to physical processes (red) that cause a measurable effect (blue), which can be mitigated by specific stabilization strategies (green).

Experimental Protocols for Minimizing Drift

Pre-Experiment System Preparation

A rigorous pre-experiment routine is the first line of defense against baseline drift.

- Buffer Preparation: "Ideally fresh buffers are prepared each day and 0.22 µM filtered and degassed before use" [2]. Storage should be in clean, sterile bottles. Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stock. Always degas an aliquot of the buffer immediately before use to prevent air-spikes in the sensorgram [2].

- Instrument Cleaning and Priming: If the instrument has been idle, perform a cleaning procedure before docking a new sensor chip. This can involve running a desorb procedure using specific solutions (e.g., 0.5% SDS followed by 50 mM glycine-NaOH, pH 9.5) and a sanitize cycle with a 10% bleach solution, as per the instrument manufacturer's guidelines [16]. This is done with a dedicated "maintenance" chip to avoid damaging an experimental chip.

- Sensor Chip Docking and Equilibration: Dock the experimental sensor chip at least 12 hours before running the experiment. Flow running buffer at a constant rate (e.g., 10 µL/min) to allow for surface rehydration and the wash-out of storage solution preservatives. "It can be necessary to run the running buffer overnight to equilibrate the surfaces" [2].

Incorporating Start-up and Blank Cycles

Stabilize the system at the beginning of an experimental run through strategic cycle design.

- Start-up Cycles: "In the experimental method, add at least three start-up cycles. These cycles are the same as the cycles with analyte but inject buffer instead of analyte. If a regeneration step is required, the regeneration injection is also done" [2]. These cycles serve to "prime" the surface, exposing it to the flow and regeneration conditions, which helps to complete the initial wash-out and surface adjustment. Data from these start-up cycles should not be used in the final analysis.

- Blank Cycles: Integrate blank (buffer alone) injections evenly throughout the experiment, approximately one blank every five to six analyte cycles, and always include one at the end. These blanks are crucial for the data analysis technique known as double referencing [2].

Data Analysis: Double Referencing

Double referencing is a standard data processing technique to compensate for residual drift, bulk refractive index effects, and differences between flow channels.

- Reference Channel Subtraction: First, subtract the signal from a reference flow channel (which should have a surface as similar as possible to the active channel, but without the specific ligand) from the signal of the active ligand channel. This step removes most of the bulk effect and system-wide drift [2].

- Blank Injection Subtraction: Second, subtract the response from the blank (buffer) injections from the analyte injection responses. This step compensates for any remaining differences between the reference and active channels and further corrects for drift. For this to be effective, the blank cycles must be spaced evenly throughout the experiment [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Stabilization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer (e.g., HEPES-KCl) | Core solution for hydrating the chip and carrying analyte. | Must be 0.22 µm filtered and degassed. Composition should match analyte storage buffer to minimize RI differences [16]. |

| NaOH Solution (e.g., 50 mM) | Common regeneration and cleaning solution. | Used to remove bound analyte and clean the fluidic system. Concentration varies by application [16]. |

| Detergent Solutions (e.g., CHAPS, Octyl-β-D-Glucopyranoside) | For system cleaning and solubilizing hydrophobic analytes. | Used in instrument desorb procedures; sterile filtered to prevent particulates [16]. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, L1, SA) | Platform for ligand immobilization. | Choice of chip (dextran, lipophilic, streptavidin) dictates immobilization chemistry and rehydration time [15]. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry Reagents | Activate carboxylated surfaces for covalent ligand immobilization. | A primary source of chemical wash-out; requires extensive washing post-immobilization [17] [15]. |

Advanced Surface Chemistry and Antifouling Strategies

For experiments in complex matrices like blood serum or cell lysate, non-specific binding (fouling) becomes a major source of signal noise and drift. Advanced surface chemistries are designed to resist fouling, which inherently improves baseline stability.

The effectiveness of antifouling materials is governed by two primary mechanisms:

- Hydration: Surfaces modified with hydrophilic polymers form a tightly bound hydration layer via hydrogen bonding. This layer creates a physical and energetic barrier that prevents proteins from adsorbing to the surface [18].

- Steric Hindrance: Polymer brushes, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), exert a repulsive force on approaching biomolecules due to the loss of conformational entropy upon compression, effectively blocking their adhesion [18].

Common classes of antifouling materials include zwitterionic compounds (e.g., peptides, polysaccharides) and PEG-based polymers. The molecular structure, charge, grafting density, and thickness of these layers are critical factors influencing their antifouling performance [18]. The following diagram illustrates the molecular-level interaction of these two mechanisms.

Figure 2. Mechanisms of antifouling surface materials. The diagram shows how different classes of antifouling materials (yellow) function through two primary mechanisms (blue) to achieve a stable baseline (green) by preventing non-specific binding.

Managing sensor surface rehydration and chemical wash-out is a critical, foundational aspect of robust SPR experimental design. These processes are inevitable consequences of standard SPR procedures but can be effectively controlled through meticulous system preparation, strategic experimental workflow design, and sophisticated data processing. By understanding the underlying causes—the physical swelling of the sensor matrix and the dissolution of chemical residues—researchers can proactively implement the protocols outlined in this guide. Furthermore, the adoption of advanced antifouling surface chemistries extends the capability of SPR to analyze complex biological samples reliably. Mastering the stabilization of the SPR baseline is not merely a technical exercise; it is a prerequisite for generating high-fidelity binding data, which is the ultimate goal of any SPR-based investigation in basic research or drug development.

Start-Up Drift and Flow Rate Sensitivity

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for studying biomolecular interactions in real-time. However, the reliability of its kinetic and affinity data is highly dependent on the stability of the baseline signal. Start-up drift and flow rate sensitivity are two prevalent challenges that can compromise data quality immediately after initiating flow or following changes in the experimental setup, such as a buffer exchange. Start-up drift manifests as a gradual shift in the baseline response when flow is initiated after a period of stagnation, while flow rate sensitivity describes baseline perturbations triggered by alterations in the flow velocity [2] [19]. Within the broader context of SPR baseline drift research, understanding these specific phenomena is critical. They are often indicative of a system that is not fully equilibrated and, if unaddressed, can lead to erroneous interpretation of binding kinetics and affinities, particularly for interactions with slow rates or weak affinity [3]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these issues, offering targeted protocols and solutions for researchers and drug development professionals.

Causes and Underlying Mechanisms

The occurrence of start-up drift and flow rate sensitivity is typically a physical and chemical symptom of system instability. Recognizing the root cause is the first step in effective troubleshooting.

Start-up drift is frequently observed directly after docking a new sensor chip or following the immobilization of a ligand. This is often due to the rehydration of the sensor surface and the gradual wash-out of chemicals used during the immobilization procedure [2]. The sensor surface and the immobilized ligand itself require time to adjust to the flow buffer's composition, temperature, and hydrodynamic conditions. Furthermore, a change in running buffer can introduce drift if the system is not sufficiently primed, leading to a mixing of the old and new buffers within the pump and tubing [2].

Flow rate sensitivity is a disturbance often seen as a drift in the sensorgram that levels out over 5 to 30 minutes after a change in flow rate [19]. This effect is caused by the sensor surface's susceptibility to mechanical and pressure changes inherent in the fluidics system. An abrupt change in flow rate can create a transient disturbance in the laminar flow profile and the pressure within the flow cell, which the sensitive SPR detector registers as a baseline shift. The duration of this effect depends on the type of sensor chip and the properties of the ligand bound to it [2] [19].

A common contributor to both issues is the presence of dissolved air in buffers or small air bubbles within the flow system. At low flow rates (e.g., < 10 µL/min), tiny air bubbles are not flushed out efficiently and can grow, becoming visible as disturbances in the sensorgram. This risk is elevated at higher temperatures (e.g., 37°C) where gas solubility decreases [19]. Therefore, the use of thoroughly degassed buffers is a critical preventive measure.

The following tables summarize key quantitative data related to drift phenomena and the effects of system configuration, providing a reference for experimental planning and diagnosis.

Table 1: Documented Drift Durations and Flow Rate Ranges

| Cause of Disturbance | Typical Duration / Flow Rate | Observable Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Start-up after flow stall [2] | 5 - 30 minutes | Baseline drift that levels out over time |

| Change in flow rate [19] | 5 - 30 minutes | Drift in sensorgram post-change |

| Low flow rate (bubble risk) [19] | < 10 µL/min | Increased probability of bubble-related drift |

| System flushing flow rate [19] | 100 µL/min | High flow rate used to flush bubbles between cycles |

Table 2: System Factors Influencing Drift and Sensitivity

| Factor | Influence on Drift | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chip Type [2] [19] | Different chips have varying susceptibility; newly docked or immobilized chips show more drift. | Allow for specific equilibration time based on chip and ligand. |

| Ligand Type [2] [19] | The nature of the immobilized ligand affects the duration of flow-change effects. | Incorporate a 15-minute WAIT command at method start for sensitive surfaces [19]. |

| Buffer Temperature [19] | Higher temperature (e.g., 37°C) increases the likelihood of bubble formation. | Ensure buffers are thoroughly degassed, especially for high-temperature runs. |

| Buffer Compatibility [2] | Incompatibility or improper priming after a buffer change causes "waviness" and drift. | Prime the system thoroughly after each buffer change; use a single buffer batch per experiment [2] [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Mitigation

Protocol for System Equilibration and Minimizing Start-Up Drift

A proactive approach to system preparation is the most effective strategy against start-up drift.

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a sufficient volume (e.g., 2 liters) of running buffer fresh on the day of the experiment. Filter through a 0.22 µM filter and thoroughly degas the solution. Store in a clean, sterile bottle at room temperature. Immediately before use, transfer an aliquot and degas it again. Do not add fresh buffer to old stock [2].

- System Priming: After any buffer change or at the start of a method, prime the system multiple times to ensure the fluidics lines and pump are completely filled with the new buffer. This prevents the mixing of buffers from different sources or compositions, which is a primary cause of baseline "waviness" [2] [19].

- Initial Equilibration: Flow running buffer over the sensor surface at the intended experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is obtained. For a new sensor chip or after an immobilization, this may require flowing buffer overnight to fully equilibrate the surface and wash out all chemicals [2].

- Incorporating Start-Up Cycles: In the experimental method, program at least three start-up cycles before data collection cycles. These cycles should be identical to the sample cycles but inject running buffer instead of analyte. If a regeneration step is used, include it. These cycles "prime" the surface and stabilize the system, and they should be excluded from the final analysis [2].

Protocol for Addressing Flow Rate Sensitivity

This protocol helps diagnose and mitigate issues arising from changes in flow rate.

- Baseline Stabilization: Before any analyte injection, initiate the flow and wait for a stable baseline. If immediate injection is necessary, a short buffer injection with a five-minute dissociation period can help stabilize the baseline before the analyte is introduced [2].

- Flow Rate Optimization: If drift is observed after a flow rate change, maintain the new rate until the baseline stabilizes (which can take 5-30 minutes). To minimize this effect at the beginning of a run, start the sensorgram at the desired flow rate and incorporate a WAIT command for 15 minutes before the first injection [19].

- Bubble Mitigation: For methods using low flow rates, introduce a high-flow-rate flushing step (e.g., 100 µL/min for a short duration) between measurement cycles to drive out any small air bubbles that may have accumulated [19].

- Drift Compensation via Referencing: Establish equal drift rates between the active and reference channels, or use double referencing to compensate for drift differences. This is especially important for experiments with long dissociation phases [2].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process and recommended actions for diagnosing and resolving start-up drift and flow rate sensitivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for preventing and mitigating start-up drift and flow rate sensitivity.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Mitigation

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | The liquid phase for dissolving analytes and maintaining the sensor surface. | Prepare fresh daily; 0.22 µM filtered and thoroughly degassed. Add detergents after degassing to avoid foam [2] [3]. |

| Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5) | The functionalized surface for ligand immobilization. | Choice of chip (dextran, NTA, SA) affects susceptibility. Newly docked chips require extensive equilibration [2] [20]. |

| Degassing Unit | Removes dissolved air from buffers to prevent bubble formation in the flow system. | Essential for all buffers, particularly when working at elevated temperatures or low flow rates [19]. |

| System Cleaning Solutions | Removes contaminants from the fluidics system (IFC, tubing, needle) that can cause drift. | Use recommended desorb and sanitize solutions if a "wavy" baseline persists after priming [19]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Blocks unused active sites on the sensor surface after immobilization. | Reduces non-specific binding, which can be a source of long-term drift and instability [3]. |

By integrating these protocols, understanding the quantitative impacts, and utilizing the essential toolkit, researchers can significantly enhance the stability of their SPR baselines, thereby ensuring the generation of high-quality, reliable data for drug development and molecular interaction studies.

Proactive Protocols: Buffer Handling and System Setup to Prevent Drift

Within the context of a broader thesis on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) baseline drift research, the preparation of running buffer emerges as a foundational, yet frequently underestimated, variable. SPR is a label-free technology that enables real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions, but its sensitivity makes it susceptible to minor experimental inconsistencies [8]. Baseline drift—the gradual shift in the sensor's baseline signal over time—is a common manifestation of such inconsistencies and poses a significant challenge for obtaining accurate kinetic and affinity data [3] [2]. Proper buffer preparation, encompassing strict protocols on freshness, filtration, and degassing, is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant in mitigating drift and ensuring the integrity of data collected after any buffer change.

The intrinsic link between buffer quality and baseline stability is rooted in both physical and chemical principles. Impurities, dissolved gases, and microbial growth in buffers can directly affect the refractive index at the sensor chip surface, leading to signal artifacts [2]. Furthermore, a change in buffer introduces a new chemical environment to the delicate surface chemistry of the sensor chip, which requires time to equilibrate fully. Inadequate preparation exacerbates this transition period, resulting in prolonged instability. Therefore, standardizing buffer protocols is a primary control measure in systematic investigations of SPR baseline drift.

Core Principles of SPR Buffer Preparation

The overarching goal of buffer preparation is to create a chemically stable and optically clean environment that minimizes system-introduced artifacts. Adherence to the following three pillars is essential.

Freshness

Daily preparation of running buffer is a non-negotiable practice for high-quality SPR data [21] [2]. The recommendation is based on two primary risks associated with old buffers:

- Chemical Degradation: Buffer components can react with atmospheric carbon dioxide, leading to pH shifts. A stable pH is crucial for maintaining the activity of immobilized ligands and the specificity of interactions.

- Microbial Contamination: Buffers, especially those containing salts, can support microbial growth, which introduces particulates and metabolic byproducts. These contaminants are a direct source of non-specific binding and signal drift. It is considered "bad practice to add fresh buffer to the old since all kind of nasty things can happen / growing in the old buffer" [2].

Filtration

Filtration of the buffer through a 0.22 µm membrane filter is a critical step immediately following preparation [21] [16]. This process serves a key function:

- Particulate Removal: It eliminates microscopic particles that could otherwise clog the instrument's delicate microfluidics, a problem that causes pressure spikes, erratic flow, and irreversible damage [21]. Filtering is a primary defense against system blockages and the resultant baseline noise.

Degassing

Degassing is the process of removing dissolved air from the buffer solution and is vital for preventing air spikes within the sensorgram [21] [2].

- Source of the Problem: Buffers stored at cold temperatures (e.g., 4°C) contain higher levels of dissolved air. When these buffers warm to room temperature within the SPR instrument, the dissolved gas comes out of solution, forming tiny bubbles [2].

- Consequences: These bubbles can become trapped in the microfluidic cartridges (IFCs), creating sudden, sharp spikes in the signal and disrupting the smooth flow of buffer across the sensor surface. A degassed buffer ensures a stable, continuous liquid flow, which is a prerequisite for a stable baseline.

Table 1: Key Buffer Additives and Their Functions in SPR Experiments

| Additive | Function | Example Concentration | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent (e.g., Tween-20) | Reduces non-specific binding of proteins to surfaces and tubing [21] [3]. | 0.005% - 0.05% [21] | Add after degassing to prevent foam formation [2]. |

| DMSO | Increases solubility of small molecule analytes; matches sample and running buffer conditions to reduce bulk refractive index shifts [21]. | 1% - 5% [21] | Match the concentration precisely between sample and running buffer. |

| BSA | Blocks remaining active sites on the sensor chip surface to prevent non-specific binding [21]. | 0.1 mg/mL [21] | Useful for stabilizing some protein ligands. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

The following detailed methodology is compiled from established technical notes and peer-reviewed protocols [21] [2] [16].

Recommended Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Buffer Preparation

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Ultrapure Water | 18 MΩ resistivity at 25°C [16]. |

| Buffer Salts | Analytical grade (e.g., HEPES, PBS components) [16]. |

| Filtration Membrane | 0.22 µm pore size, sterile [21] [16]. |

| Detergent Solutions | e.g., Tween-20 for reducing non-specific binding [21]. |

| pH Meter | For accurate adjustment of buffer pH. |

| Sterile Bottles | For storage of prepared buffers to minimize contamination. |

Detailed Workflow

- Formulate and Prepare: Dissolve buffer salts in ultrapure water to the desired concentration. A common SPR running buffer is PBS (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) or HEPES-KCl (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4) [21] [16].

- Adjust pH: Carefully adjust the pH of the solution using a calibrated pH meter. Proper pH adjustment is critical for the stability of the molecular interaction being studied [21].

- Filter: Immediately filter the entire volume of buffer through a 0.22 µm filter into a clean, sterile storage bottle. This removes particulates and also serves to sterilize the solution [2] [16].

- Degas: Subject the filtered buffer to a degassing procedure. This can be done using an in-line degasser on the SPR instrument, a vacuum degassing system, or by sonication under vacuum.

- Add Additives: After degassing, gently add any required detergents (like Tween-20) or DMSO. Pouring gently at this stage prevents the introduction of foam or bubbles [21].

- Daily Use: Transfer a sufficient aliquot for the day's experiments to a clean bottle. The buffer should be used at room temperature to prevent "outgassing" inside the system [21]. Discard any unused buffer at the end of the day; do not top off old buffers with new ones.

The logical relationship between proper buffer preparation and its impact on experimental outcomes is summarized in the workflow below.

Diagram: Workflow of optimal SPR buffer preparation leading to data quality outcomes.

Connecting Buffer Preparation to Broader Drift Research

While optimal buffer preparation is a direct control, its effectiveness is realized within a holistic experimental framework. Research into baseline drift must therefore consider the interaction of buffer quality with other system components.

After a buffer change, comprehensive system equilibration is mandatory. Even a perfectly prepared new buffer requires time to fully displace the old buffer within the microfluidics and equilibrate with the sensor surface chemistry. The recommended procedure is to prime the system several times with the new buffer and then allow a continuous flow until a stable baseline is achieved, which can sometimes take 30 minutes or more [2]. Incorporating start-up cycles (5-15 buffer injections prior to analyte injection) into the method is a proven strategy to accelerate surface equilibration and improve overall data quality [21].

Furthermore, the principles of double referencing are a critical computational correction that complements good buffer practice. This data processing technique involves subtracting the signal from a reference flow cell and also subtracting signals from blank (buffer-only) injections. This method directly compensates for any residual baseline drift and bulk refractive index effects, providing a more robust dataset [2]. In drift research, the combination of meticulous buffer preparation and rigorous data referencing provides a powerful strategy to isolate and quantify drift originating from other sources, such as ligand instability or instrument performance.

In Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) research, baseline drift following a buffer change is a frequently encountered challenge that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous kinetic analysis. This drift often manifests as a persistent waviness in the sensorgram, directly mirroring pump strokes, and originates from the incomplete mixing of the previous buffer with the new one within the fluidic system [2]. Within the context of a broader thesis on SPR baseline drift, the procedure of priming the system emerges not merely as a routine recommendation but as a critical, non-negotiable step for ensuring data validity. It is the foundational process that establishes a stable, equilibrated environment necessary for quantifying biomolecular interactions with high precision. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this step is essential for generating publication-quality, reproducible binding data, as it directly addresses a key preventable cause of experimental artifact.

The Critical Role of Priming in System Equilibration

Understanding the Consequences of Inadequate Priming

Failing to prime the system thoroughly after changing the running buffer introduces a significant variable that can invalidate careful experimental design. The core issue is the creation of a heterogeneous buffer environment within the intricate tubing and flow channels of the SPR instrument [2]. As the pump operates, it does not instantly replace the old buffer but instead creates a gradual gradient, leading to a phenomenon often described as "waviness pump stroke" in the sensorgram [2]. This instability is not merely a visual nuisance; it reflects real changes in the refractive index at the sensor surface, which are misinterpreted by the instrument as binding events. Consequently, kinetic and affinity models fitted to this noisy and drifting data will be fundamentally flawed, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions in critical areas like lead compound optimization or antibody characterization.

The Science of Stabilization: How Priming Works

Priming is the deliberate process of flushing the instrument's entire fluidic path with a sufficient volume of the new running buffer to achieve complete buffer replacement. This process serves two primary functions:

- Complete Buffer Exchange: It physically displaces the residual buffer from the previous experiment or condition, ensuring that the analyte and ligand are exposed to a consistent solvent environment throughout the analysis cycle [2].

- System Re-equilibration: It allows the sensor chip surface, the immobilized ligand, and the dextran matrix (if present) to adapt to the new buffer's pH, ionic strength, and chemical composition [2]. This is particularly crucial after an immobilization procedure or the use of harsh regeneration solutions, which can alter the physical properties of the sensor surface and require extended periods to re-stabilize [22].

Comprehensive Priming and Equilibration Protocol

Standard Operating Procedure for Priming

A meticulous approach to priming is required for rigorous experimentation. The following step-by-step protocol should be adopted as a standard practice.

Table 1: Step-by-Step Priming Protocol After Buffer Change

| Step | Action | Purpose & Rationale | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Prepare a fresh batch of running buffer and filter (0.22 µm) and degas it. | Prevents air spikes and contamination from buffer impurities or microbial growth [2]. | 2 liters, filtered and degassed. |

| 2. System Command | Execute the instrument's "Prime" command, typically multiple times. | Forces the new buffer through the entire fluidic system (needles, tubing, injection loop, flow cells) to displace the old buffer completely [2]. | Minimum of 3-5 prime cycles. |

| 3. Initial Flow | Initiate a continuous flow of running buffer at the experimental flow rate. | Begins the process of equilibrating the sensor chip surface and stabilizes the pressure in the flow system [2]. | Standard flow rate (e.g., 30 µL/min). |

| 4. Baseline Monitoring | Monitor the baseline response in real-time without injecting any sample. | Provides a direct visual assessment of baseline stability, indicating whether the system has reached equilibrium [2]. | Observe until flat (variation < 1 RU). |

| 5. Final Verification | Perform several dummy injections of running buffer, including regeneration steps if used. | "Primes" the surface by exposing it to the injection cycle's pressure changes and chemical environment, stabilizing it before real analyte injections [2]. | At least 3 start-up cycles. |

Advanced Equilibration Strategies

For systems that are particularly sensitive or when using challenging buffer conditions, the basic priming procedure may need to be enhanced. Incorporating start-up cycles is a highly effective advanced strategy. These are identical to the experimental cycles used for analyte injection, but they use a buffer-only injection instead of analyte [2]. If a regeneration step is part of the method, it should be included in these start-up cycles. This process serves to condition the sensor surface, acclimatizing it to the mechanical and chemical stresses of the experimental run, thereby minimizing the initial drift often seen in the first few cycles. These start-up cycles should be excluded from the final data analysis [2].

Another critical strategy is the inclusion of blank injections (buffer alone) spaced evenly throughout the experiment, ideally one every five to six analyte cycles, and always ending with one [2]. These blanks are fundamental for performing double referencing, a data processing technique that subtracts out systematic noise and drift, further compensating for any residual instability [2].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Priming and Equilibration

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Priming & Equilibration | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Creates the solvent environment for interactions; its consistency is paramount. | Freshly prepared daily, 0.22 µM filtered and degassed. Common examples: HBS-EP (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% P20), PBS. |

| Degassed Water | Used for initial system flushing or as a diluent; degassing prevents air bubble formation. | Ultrapure water, rigorously degassed using a sonicator or vacuum degasser. |

| System Fluidic Cleaner | Periodically used to remove contaminants, aggregates, and non-specifically bound material from the entire fluidic path. | Instrument-specific solutions (e.g, Biacore Desorb and Sanitize solutions). Used according to manufacturer protocols. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for a successful priming and equilibration strategy.

Integrating Priming into a Holistic Drift Mitigation Workflow

While priming is critical after a buffer change, it is part of a larger strategy to combat baseline drift. A holistic view is necessary for consistent success.

Buffer Hygiene: The quality of the running buffer is the first line of defense. Buffers should be prepared fresh daily from high-quality reagents and stored properly to prevent contamination and microbial growth, which can be a significant source of drift and noise [2] [9]. It is considered bad practice to add fresh buffer to an old batch [2].

Sensor Chip Handling: Newly docked sensor chips or surfaces freshly modified with ligand require an extended period of equilibration. This allows for the rehydration of the surface and the wash-out of chemicals used during the immobilization process, which can cause substantial initial drift [2]. In some cases, flowing running buffer overnight may be necessary to achieve perfect stability.

Environmental and Instrumental Factors: The SPR instrument should be located in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations, as these can directly cause baseline instability [9]. Furthermore, a systematic approach to preventative maintenance, including regular calibration and checks for fluidic leaks, is essential for long-term baseline stability [9].

In the meticulous world of SPR analysis, where the detection of minuscule refractive index changes is paramount, the stability of the baseline is the bedrock of data integrity. The simple act of priming the system after a buffer change is a powerful and cost-effective intervention that addresses a primary, preventable cause of baseline drift. By adopting the detailed protocols and holistic framework outlined in this guide—encompassing rigorous buffer preparation, systematic priming, advanced equilibration via start-up cycles, and consistent data processing with double referencing—researchers can transform their approach. This disciplined practice ensures that the observed binding signals are a true reflection of molecular interaction kinetics, thereby upholding the highest standards of scientific rigor in drug development and basic research.

Incorporating Start-Up and Blank Cycles in Method Design

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors are powerful tools for characterizing molecular interactions in drug development and basic research. However, baseline instability following buffer changes presents a significant challenge, compromising data quality and leading to erroneous kinetic and affinity calculations. This technical guide examines the critical practice of incorporating start-up and blank cycles into SPR method design as a systematic approach to mitigate baseline drift. Framed within broader research on SPR baseline stability, we provide researchers with detailed protocols, quantitative frameworks, and practical strategies to enhance data reliability, improve replicability, and streamline biosensor validation.

In SPR analysis, baseline drift—a gradual change in the response signal when no active binding occurs—is a prevalent issue that directly impacts data integrity. This drift is particularly pronounced after system perturbations such as buffer changes or sensor chip docking [2]. The root causes are multifaceted:

- Insufficient System Equilibration: The instrument's fluidics and sensor surface require time to reach a state of physical and chemical equilibrium with the new running buffer.

- Sensor Surface Rehydration: Newly docked sensor chips undergo rehydration, and chemicals from immobilization procedures wash out, causing signal instability [2].

- Buffer Incompatibility: Differences in composition, ionic strength, or temperature between buffers can create refractive index gradients and surface interactions that manifest as drift.

This drift introduces systematic errors in the determination of binding kinetics (association rate constant, ( k{on} ), and dissociation rate constant, ( k{off} )) and equilibrium affinity constants (( K_D )). In the context of rigorous biosensor development and validation, controlling for these variables is not merely good practice but a prerequisite for generating reliable, publication-quality data. This guide details how a disciplined approach to method design, specifically the use of start-up and blank cycles, provides a robust solution to these challenges.

Core Concepts: Start-Up and Blank Cycles

Start-Up Cycles

Purpose: Start-up cycles, also known as conditioning or "dummy" cycles, are initial method sequences designed to stabilize the SPR system before analyte data collection begins.

Function: They "prime" the sensor surface and fluidic system by mimicking the experimental conditions without injecting analyte. This process accommodates the initial period of significant drift, allowing the system to reach a stable state where the baseline response has a minimal and consistent drift rate [2].

Implementation: A typical start-up cycle involves flowing running buffer and executing all steps of a standard sample cycle—including any regeneration injections—but with buffer substituted for the analyte solution [2]. It is critical that data from these start-up cycles are excluded from the final analysis.

Blank Cycles

Purpose: Blank cycles are interspersed throughout the experimental run and contain only running buffer injected over both reference and active ligand surfaces.

Function: They serve two primary purposes. First, they provide a critical tool for double referencing, a data processing technique that subtracts systematic noise and drift. Second, they monitor the system's stability throughout the entire experiment, confirming that the low drift rate achieved during start-up is maintained [2].

Implementation: The response from a blank injection is subtracted from the analyte injection responses to correct for any residual bulk refractive index shifts and channel-specific drift [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comprehensive Pre-Experiment System Preparation

A stable baseline begins with proper system preparation before the automated method is even initiated.

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare running buffer fresh daily. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter and degas thoroughly. Avoid adding fresh buffer to old stock. After degassing, add appropriate detergents (e.g., surfactant P20) to minimize nonspecific binding [2].

- System Priming: After any buffer change, prime the instrument's fluidic system extensively. This replaces the liquid in the pumps and tubing, preventing a "waviness pump stroke" signal caused by the mixing of old and new buffers [2].