Sample Preparation for Surface Analysis: An IUPAC Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of sample preparation for surface analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences.

Sample Preparation for Surface Analysis: An IUPAC Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of sample preparation for surface analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences. It covers foundational IUPAC terminology, methodological approaches for techniques like XPS and AES, troubleshooting for common contamination issues, and validation strategies to ensure analytical accuracy. By aligning with the latest IUPAC recommendations, this article serves as a critical resource for obtaining reliable, high-quality surface data that can inform material design, drug delivery systems, and diagnostic tool development.

Understanding Surface Analysis: Core IUPAC Concepts and Definitions

In surface science and analytical chemistry, the precise definition of the "surface" is fundamental to obtaining reliable, reproducible, and meaningful data. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) provides a critical framework that distinguishes between different surface concepts, recognizing that the term "surface" holds varying meanings depending on context—from general discussion to physical reality and experimental interaction [1]. This nuanced classification system is particularly vital for a thesis focused on sample preparation, as the preparation methodology directly influences which aspect of the surface is being probed and must therefore be documented with utmost precision. Without these standardized definitions, comparing results across different studies, techniques, and laboratories becomes fraught with ambiguity. The IUPAC recommendations establish a common language that enables clear communication among researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, ensuring that when one discusses the "surface," the specific layer or volume of interest is unequivocally defined [1] [2].

For professionals engaged in drug development, this precision is not merely academic. The interaction of a drug substance with its environment—be it during processing, in a delivery matrix, or at a biological target—is governed by its surface properties. Misinterpreting which "surface" is being analyzed could lead to flawed predictions of stability, bioavailability, or performance. This document outlines the IUPAC classifications and translates them into practical application notes and protocols, providing a rigorous foundation for thesis research and industrial application alike.

IUPAC Surface Classifications: Definitions and Implications

IUPAC recommends a three-tiered classification for the term "surface" to enhance clarity in surface analysis. The distinctions between these definitions are foundational to designing experiments, preparing samples, and interpreting data. The following table summarizes these core classifications.

Table 1: IUPAC Classifications of "Surface" for Analytical Chemistry

| Classification | Formal IUPAC Definition | Key Characteristics | Primary Importance in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Surface | The 'outer portion' of a sample of undefined depth [1]. | • Imprecise, qualitative• Used for general discussions• Depth is not specified | Provides a common term for initial, non-specific descriptions of the sample's exterior. |

| Physical Surface | That atomic layer of a sample which, in a vacuum, is the layer 'in contact with' the vacuum; the outermost atomic layer [1]. | • Theoretically ideal• Precisely one atom/molecule deep• Represents the absolute boundary | Critical for theoretical models and understanding fundamental surface interactions and reactivity. |

| Experimental Surface | That portion of the sample with which there is significant interaction with the particles or radiation used for excitation [1]. | • Defined by the analysis technique• A volume, not just a layer• Depth depends on probe and sample | The most practical definition; determines what is actually being measured and must be considered for data interpretation. |

The General Surface

The General Surface is the most colloquial of the three terms. It refers to the vague "outside" of a sample without any specification of its depth or atomic structure [1]. In a thesis context, this term is appropriate for introductory sections or broad-stroke discussions where the exact region of interest has not yet been defined by the analytical technique. For example, one might state, "The general surface of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) was contaminated after exposure to ambient laboratory air." This usage signals that a more precise investigation is required to determine the nature and extent of the contamination.

The Physical Surface

The Physical Surface is a rigorous theoretical construct, defined as the outermost atomic layer of a sample [1]. This is the layer that would be in direct contact with a perfect vacuum. In an ideal, defect-free world, this is the region where surface energy, catalytic activity, and adsorption processes initiate. The related concept of a Regular Surface—a perfect surface without heterogeneities or defects—is acknowledged as largely theoretical, though in practice, the term can be applied to local regions of real surfaces where the influence of nearby defects is negligible [3]. Understanding the ideal physical surface is crucial for modeling interfacial phenomena, but it is rarely, if ever, directly measured in its entirety due to the inherent imperfections of real materials and the limitations of analytical probes.

The Experimental Surface

The Experimental Surface is the most critical concept for practicing scientists. It is defined not by a fixed depth, but by the interaction volume between the sample and the analytical probe [1]. This volume is determined by whichever is larger: the depth required for the incoming radiation or particles to cause excitation, or the escape depth for the resulting emitted radiation or particles.

For instance:

- In X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), the experimental surface is typically the top 5-10 nm, dictated by the escape depth of the photoelectrons.

- In Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS), it can be as shallow as the top 1-2 monolayers for static SIMS or much deeper for dynamic SIMS.

- The concentration of a material within the experimental surface is defined as the amount of the material of interest divided by the total amount of substances in this interaction volume [4].

Therefore, the choice of analytical technique fundamentally defines the "surface" being studied. A sample preparation protocol that is optimal for XPS analysis might be entirely unsuitable for SIMS, precisely because each technique probes a different "experimental surface."

Experimental Protocols for Surface Characterization

The following protocols are adapted from IUPAC recommendations and standard practices for the physical adsorption characterization of porous and finely divided solids, which are common in pharmaceutical development [5].

Protocol: Sample Outgassing for Surface Area Analysis

1. Principle: The removal of pre-adsorbed contaminants (e.g., water vapor, atmospheric gases) from the surface and pores of a solid is essential prior to measuring surface area via gas physisorption. Inadequate outgassing leads to significant underestimation of surface area and pore volume.

2. Equipment & Reagents:

- Manometric (volumetric) gas sorption analyzer (e.g., Anton Paar Autosorb iQ, Quadrasorb) [5].

- High-purity vacuum system (capable of achieving pressures < 1 Pa, preferably with a turbo molecular pump) [5].

- Sample tube.

- Heating mantle with temperature controller.

3. Procedure:

- Weighing: Accurately weigh the clean, dry sample tube. Transfer a sufficient mass of sample (enough to provide a total surface area of >5 m² for the measurement) into the tube. Reweigh to determine the exact sample mass.

- Mounting: Securely attach the sample tube to the outgassing port of the sorption analyzer.

- Microporous Materials (e.g., zeolites, some MOFs): Apply vacuum (pressure < 1 Pa) and heat the sample to a predetermined temperature (e.g., 300°C) for a specified duration (typically several hours to 24 hours). The temperature must be below the decomposition temperature of the material [5].

- Non-Microporous Materials: As an alternative to vacuum, flushing the sample with an inert, dry gas (e.g., nitrogen or helium) at an elevated temperature for a set time may be sufficient [5].

- Cooling: After the outgassing cycle is complete, isolate the sample tube and allow it to cool to ambient temperature under continuous vacuum or inert gas flow.

- Verification: The sample is considered properly outgassed when the pressure rise in the isolated system is negligible over a period of several minutes.

4. Safety Notes:

- Always know the thermal stability of your sample to prevent decomposition or phase changes.

- Use heat-resistant gloves when handling hot equipment.

Protocol: Void Volume Calibration for Volumetric Adsorption

1. Principle: In manometric (volumetric) gas adsorption, the amount adsorbed is the difference between the gas admitted and the gas required to fill the space around the adsorbent (the "void volume"). An accurate void volume determination is critical for all subsequent calculations [5].

2. Equipment & Reagents:

- Manometric gas sorption analyzer.

- High-purity helium (≥99.999%) or the adsorptive gas to be used (e.g., nitrogen, argon).

- Liquid nitrogen or a CryoSync/CryoCooler device.

3. Procedure (Two Methods):

A. Helium Method (Standard):

- After outgassing, immerse the sample tube in a cryostat (e.g., liquid nitrogen at 77 K or a bath set to 87 K for argon).

- Expand a known amount of helium into the sample tube.

- Measure the equilibrium pressure to calculate the void volume, assuming helium adsorption is negligible under these conditions.

- Note: This assumption may be invalid for solids with very narrow micropores (<1 nm) where helium entrapment can occur [5].

B. NOVA (NO Void Analysis) Mode (For Narrow Micropores):

- Perform a multipoint void volume determination on the empty sample cell using the actual adsorptive (e.g., N₂ or Ar) at the analysis temperature prior to the isotherm measurement.

- This calibrated empty-cell volume is then used as a reference, and the "sample volume" is back-calculated during the subsequent sample analysis, avoiding issues with helium [5].

4. Data Analysis:

- The instrument software typically performs these calculations. The researcher must select the appropriate method based on the sample's porosity and document the choice thoroughly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions in surface preparation and analysis, as informed by the search results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Surface Analysis | Key Considerations & IUPAC Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Sorbent material for sample preparation (e.g., SPE, SPME) to isolate and concentrate analytes from complex liquid samples [6]. | High specific surface area (up to ~7000 m²/g) and tunable pore size; selection depends on target analyte and required selectivity [6]. |

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂), 77 K | Traditional adsorptive for measuring surface area and mesoporosity (2-50 nm) via physisorption isotherms [5]. | Not recommended for micropore analysis due to quadrupole moment causing specific interactions; can lead to inaccurate pore size distributions [5]. |

| Argon Gas (Ar), 87 K | Recommended adsorptive for accurate micropore size analysis [5]. | Lacks a quadrupole moment, minimizing specific interactions with surface functional groups; provides more reliable pore filling data for micropores [5]. |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂), 273 K | Recommended adsorptive for characterizing nanoporous carbons with narrow micropores [5]. | Higher temperature than cryogenic N₂/Ar allows faster diffusion into ultramicropores that are kinetically restricted at lower temperatures. |

| Krypton Gas (Kr), 77 K | Recommended adsorptive for analyzing very low surface area materials (< 1 m²) [5]. | Its low saturation vapor pressure at 77 K allows for more accurate measurements of small adsorbed amounts on limited surfaces. |

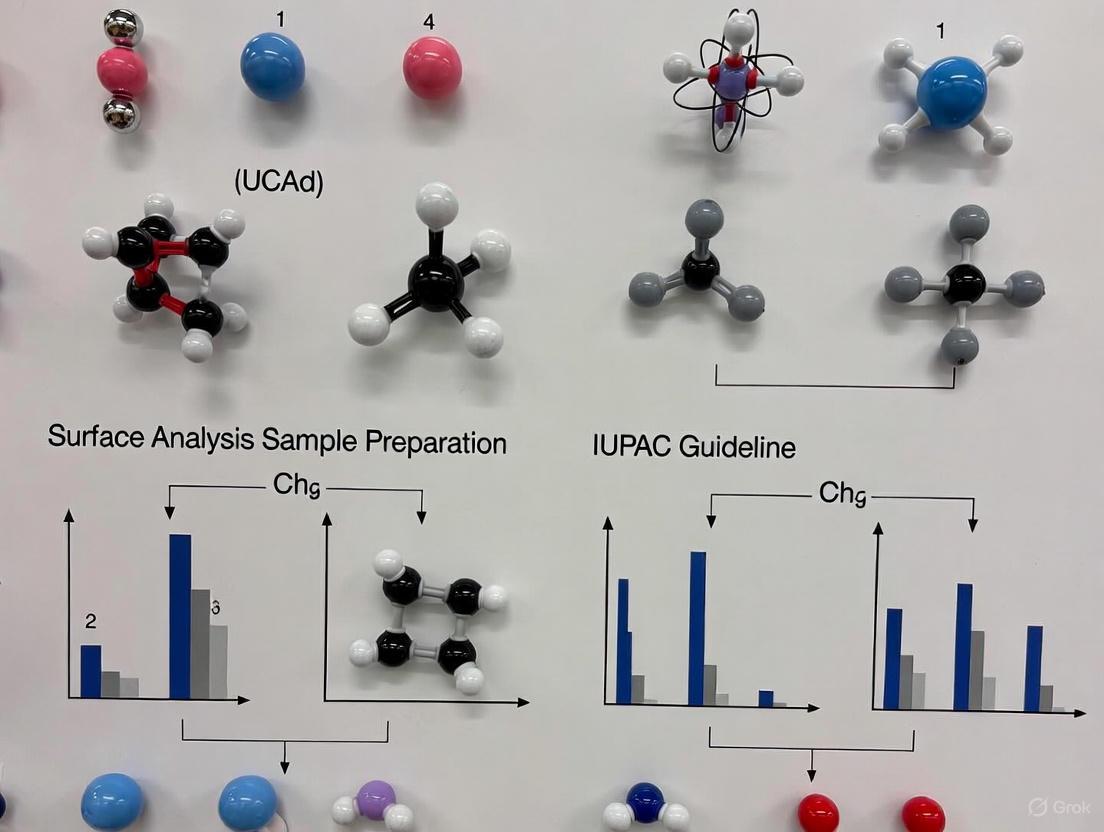

Workflow and Relationship Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between IUPAC's surface classifications, the analytical process, and the critical choices that define the experimental surface.

Adherence to IUPAC's precise definitions of "surface" is not a mere formality but a cornerstone of rigorous scientific practice in surface analysis. For a thesis centered on sample preparation, this framework provides the necessary lexicon to justify methodological choices and to accurately interpret analytical results. The researcher must be perpetually aware that the "Experimental Surface"—a volume defined by the specific analytical technique and its parameters—is the true subject of measurement. The protocols for sample preparation, such as outgassing and void volume determination, must be executed with an understanding of their impact on this defined region. By systematically applying these classifications and associated standard practices, researchers in both academia and drug development can ensure their findings on surface properties are reliable, reproducible, and meaningful, thereby building a solid foundation for subsequent development and regulatory review.

The Critical Role of Sample Preparation in Analytical Accuracy and Reproducibility

Sample preparation is a foundational step in analytical science, serving as the critical bridge between a raw sample and a reliable, interpretable result. In the context of surface analysis for drug development and chemical research, the accuracy of analytical techniques is fundamentally constrained by the care taken during sample preparation. Contamination, improper handling, or inconsistent presentation can introduce significant errors, leading to irreproducible data and flawed scientific conclusions [7] [8]. This document outlines standardized protocols and best practices to ensure data integrity, with a focus on methodologies relevant to an IUPAC-guided research framework.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents required for proper sample preparation to ensure analytical accuracy.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Reagents for Sample Preparation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Indium Foil | Substrate for pressing powdered samples for XPS analysis [8]. | Ensures a clean, conductive surface and avoids interference with the sample's elemental composition. |

| Clean Silicon Wafer | Inert substrate for drop-casting sample solutions [8]. | Provides an atomically flat and clean surface for uniform sample deposition. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) | Solvent for cleaning tweezers and other tools via sonication [7] [8]. | Effectively removes organic contaminants without leaving significant residues. |

| Powder-free Gloves (Nitrile/PE) | Personal protective equipment to prevent sample contamination [8]. | Prevents introduction of particulates and skin oils onto the sample surface. |

| Sticky Carbon Conductive Tape | Adhesive substrate for mounting certain powders or particles [8]. | Provides conductivity; should be avoided if carbon is an element of interest in the sample. |

| Clean Polystyrene Petri Dishes | Container for sample storage and transport [7] [8]. | Prevents contamination during sample handling and storage prior to analysis. |

Sample Preparation Workflow for Surface Analysis

The process of preparing a sample for surface analysis involves a series of deliberate, sequential steps to preserve the sample's native state and ensure the resulting data is representative and accurate. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and decision-making process.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Powdered Samples

Powdered samples present a significant challenge due to their high surface area and potential for contamination. The following quantitative data summarizes the primary methods and their criteria for use.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Powder Preparation Methods for XPS

| Preparation Method | Recommended Sample Amount | Typical Particle Size | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressing into Indium Foil | Sufficient to form a monolayer [8] | Not specified | Creates a flat, conductive surface; preferred method [8] | Potential for incomplete coverage or particle shedding. |

| Drop-Casting from Solution | Varies by solubility [8] | Not applicable (dissolved) | Produces a uniform film on a flat substrate (e.g., Si wafer) [8] | Requires a suitable, pure solvent that does not alter sample chemistry. |

| Sprinkling on Carbon Tape | Sufficient for a sparse monolayer [8] | Not specified | Fast and simple for conductive samples [8] | Carbon tape signal may interfere with analysis; not suitable for loose, fine powders. |

Step-by-Step Procedure for Pressing into Indium Foil:

- Material Preparation: Using clean tweezers, cut a piece of high-purity indium foil to approximately 1 cm x 1 cm. Clean the tweezers via sonication in Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) for 5-10 minutes and allow to air dry in a clean environment [7].

- Sample Application: Place the indium foil on a clean, stable surface. Gently sprinkle a small amount of the powder onto the center of the foil.

- Pressing: Place a second, smaller piece of clean indium foil or a clean glass slide on top of the powder. Apply firm and even pressure to create a flat, compact layer. The goal is a monolayer where particles are immobilized and in electrical contact with the conductive foil [8].

- Final Inspection: Gently tap or use a stream of clean, dry air to remove any loose, unbound particles. Ensure the analysis side is obvious and document this on the sample submission form [7].

Protocol for Bulk Solid Samples

The integrity of bulk solid analysis depends on a pristine surface.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Handling: Manipulate the sample only with powder-free nitrile or polyethylene gloves and clean tools to avoid contamination from skin oils or dust [8].

- Cleaning (if applicable): For samples contaminated with salts or electrolytes, rinse gently with distilled water and air dry. For organic contaminants, consider a gentle wash with a suitable solvent like IPA, ensuring the solvent does not react with the sample [8] [9].

- Mounting: Securely mount the sample on an appropriate XPS sample stub using a double-sided conductive adhesive tab or clip. The analysis area must be flat and unobstructed. For magnetic samples, contact the instrument operator in advance as special mounting procedures are required [8].

General Best Practices for All Sample Types

- Consistency is Critical: For all sample types, especially powders, translucent solids, and liquids, maintain consistency in thickness, size, and presentation for each measurement to ensure reproducibility [9].

- Contamination Control: Always use gloves and clean tools. Store and transport samples in clean glass vials, polystyrene Petri dishes, or new aluminum foil. Avoid all other plastic containers and bags [7] [8].

- Pump-down Time: Samples with high surface area (e.g., powders) or those that have been immersed in liquids require longer pump-down times in the vacuum chamber. It is often advisable to load such samples into the instrument's load lock the evening before analysis [8].

Material Selection Logic for Sample Preparation

Choosing the correct preparation materials is paramount to avoid introducing analytical artifacts. The logic below guides the selection of substrates and handling tools based on sample properties.

Adherence to rigorous, standardized sample preparation protocols is not merely a preliminary task but a determinant of analytical success. The methodologies detailed herein, developed within the context of IUPAC-guided research, provide a framework for achieving the accuracy and reproducibility demanded in scientific research and drug development. By systematically controlling for contamination, selecting appropriate materials, and following consistent workflows, researchers can ensure that their analytical results are a true reflection of the sample's properties and not an artifact of its preparation.

Identifying Common Surface Contaminants and Their Impact on Analytical Results

Within the framework of IUPAC guidelines for sample preparation and surface analysis, the control of surface contamination is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental determinant of analytical accuracy [1]. Surface contaminants are defined as impurities that physisorb, bond, or settle on surfaces, adversely affecting the physical and chemical properties of the material and subsequent analytical measurements [10] [11]. These contaminants originate from diverse sources including manufacturing processes, environmental exposure, and improper handling, presenting in both visible and invisible forms with thicknesses ranging from monolayers to layers several nanometers thick [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the implications extend beyond analytical interference to encompass regulatory compliance, product safety, and material integrity, particularly when working with potent active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) where cross-contamination poses serious health risks [12]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for identifying, quantifying, and mitigating surface contaminants to ensure analytical reliability in accordance with IUPAC standards for surface characterization.

Surface contaminants can be systematically categorized based on their composition, origin, and physical characteristics. Understanding this classification is essential for developing targeted detection and mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Classification of Common Surface Contaminants

| Contaminant Category | Specific Examples | Primary Sources | Physical Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonaceous Residues | Adventitious carbon, Heavy hydrocarbons, Graphite-like carbon | Airborne hydrocarbons, Incomplete combustion, Plasma cleaning residues [10] | Invisible thin films (3-8 nm) [10] |

| Silicone-Based Compounds | Silicone oil, Silicone polymers | Lubricants, Door seals, Laboratory tubing [10] [13] | Oily films, Residues |

| Particulates | Dust, Rust, Mill scale | Shot blasting, Environmental dust, Equipment wear [10] [14] | Micron-sized particles [10] |

| Soluble Salts | Chlorides, Sulfates | Acid rain, Marine environments, Industrial pollution, Process water [10] [11] | Crystalline deposits, Invisible films |

| Biological Matter | Microorganisms, Pyrogens | Stagnant water, Improper equipment storage [12] | Biofilms, Particulates |

| Metallic Residues | Aluminum, Iron, Zinc, Lead | Labware leaching, Environmental air, Cleaning tools [13] | Ions, Particles |

Invisible Contaminants: The Hidden Challenge

The most insidious contaminants are those not visible to the naked eye. Adventitious carbon represents a universal contaminant found on all materials exposed to ambient conditions, typically forming layers of 3-8 nanometers thickness [10]. Similarly, silicone oil contamination migrates readily from lubricants and seals, while soluble salts such as chlorides and sulfates deposit from environmental sources like acid rain and marine spray [10] [11]. These invisible contaminants are particularly problematic in semiconductor, optoelectronic, and pharmaceutical industries where molecular-level purity is critical for device performance and product safety [10].

Visible Contaminants: Indicators of Process Control Failures

Visible contaminants including dust, grime, rust, and oil films often signal broader process control issues [10] [14]. While more readily identified, their presence indicates potential cross-contamination risks that can compromise analytical results and product quality. In industrial coating applications, visible residues such as oil films prevent proper adhesion of protective coatings, leading to premature failure and accelerated corrosion [10] [14].

Impact of Contaminants on Analytical Results and Material Performance

Surface contaminants introduce significant errors in analytical measurements and impair material performance through multiple mechanisms.

Analytical Interference Mechanisms

The presence of surface contaminants can interfere with analytical techniques through various physical and chemical mechanisms. In Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), hydrocarbon and water vapor contamination layers create capillary forces that cause attractive interactions between the probe and sample, resulting in false feedback, reduced resolution, limited scan rates, and image artifacts [10]. For spectroscopic techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), surface contamination alters the elemental composition readings within the typical analysis depth of 10 nanometers, potentially leading to misinterpretation of surface chemistry [10]. In ICP and ICP-MS analysis, trace contaminants from water, acids, or labware can elevate background signals, producing falsely elevated results for common elements like sodium, calcium, aluminum, and zinc at parts-per-billion or parts-per-trillion levels [13].

Table 2: Impact of Common Laboratory Contaminants on Analytical Results

| Contaminant Source | Affected Elements | Typical Concentration Range | Primary Analytical Techniques Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borosilicate Glassware | Boron, Silicon, Sodium | Variable, potentially significant at low ppm [13] | ICP-MS, ICP-OES, Trace metal analysis |

| Impure Acids (e.g., HCl) | Various metals (Fe, Ni, etc.) | Up to 100 ppb in acid [13] | All elemental analysis techniques |

| Laboratory Air (Ordinary) | Iron, Lead, Aluminum | ng/m³ levels [13] | Surface analysis, Trace element analysis |

| Silicone Tubing | Silicon, Aluminum, Iron, Magnesium | Significant in presence of nitric acid [13] | HPLC, Flow-based analysis systems |

| Powdered Gloves | Zinc | High concentrations [13] | Trace element analysis, Surface analysis |

Material Performance Degradation

Beyond analytical interference, surface contaminants critically impact material performance and longevity. The most significant consequence involves corrosion initiation, where soluble salts such as chlorides and sulfates react with metal surfaces to form corrosion cells, accelerating material degradation [10] [11]. In protective coating applications, contaminants at the coating-substrate interface cause adhesive failure through osmotic blistering, where moisture drawn through the coating forms blisters beneath it, leading to delamination and under-film corrosion [10] [14] [11]. For pharmaceutical manufacturing, cross-contamination between potent compounds (e.g., steroids, hormones) or with pesticide residues presents serious health risks, as evidenced by FDA recalls and import alerts [12].

Detection and Analytical Methods for Surface Contamination

A systematic approach to contamination detection employs complementary analytical techniques to characterize both the composition and distribution of surface residues.

Advanced Analytical Techniques

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS/ESCA): This surface-sensitive technique provides quantitative elemental composition within the top 10 nanometers of a surface, enabling identification of chemical states and detection of as little as 0.1 monatomic layer of contamination [10]. XPS is particularly valuable for characterizing adventitious carbon, silicone contamination, and evaluating surface cleanliness after cleaning procedures [10].

Chromatographic-Mass Spectrometric Methods: Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables detection and quantification of organic contaminants including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and process residues at nanogram per liter levels [15] [16]. These methods are essential for monitoring environmental contaminants of concern in water and wastewater, with applications extending to pharmaceutical manufacturing cleanliness verification [15] [16].

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): AFM imaging combined with force-distance (F/D) curve measurements directly characterizes contamination layer thickness and properties through interactive forces between the probe and sample surface [10]. This technique is particularly sensitive to hydrocarbon and water vapor layers that affect nanoscale measurements.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): For trace metal contamination, ICP-MS provides exceptional sensitivity down to parts-per-trillion levels, making it indispensable for quantifying metallic impurities from labware, reagents, and environmental sources [13].

Standardized Surface Preparation and Cleanliness Assessment

Industry standards provide standardized methodologies for surface preparation and cleanliness assessment. The Association for Materials Protection and Performance (AMPP, formerly SSPC/NACE) standards define specific cleanliness levels for steel surfaces before coating application [14]:

- SSPC-SP-1 Solvent Cleaning: Removes soluble contaminants using steam, emulsifying agents, or cleaning compounds [14].

- SSPC-SP-5 White Metal Blast Cleaning: Produces a surface uniformly free of all visible contaminants with a white or gray appearance [14].

- SSPC-SP-10 Near-White Metal Blast Cleaning: Allows only 5% of each unit area to exhibit random staining [14].

- SSPC-SP-6 Commercial Blast Cleaning: Permits up to 33% of each unit area to contain residual stains [14].

These standards establish reproducible methods for quantifying surface cleanliness, with applicability extending beyond industrial coatings to analytical sample preparation.

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Assessment and Control

Protocol 1: Surface Cleanliness Validation for Analytical Equipment

This protocol aligns with FDA guidance on cleaning validation for pharmaceutical equipment [12] and can be adapted for analytical instrumentation.

Objective: To verify the effectiveness of cleaning procedures for analytical equipment and prevent cross-contamination between samples.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-purity water (ASTM Type I or better) [13]

- High-purity acids (trace metal grade) [13]

- Appropriate solvents (HPLC grade or better)

- Sampling materials (swabs, rinsate collection containers)

- Analytical instrumentation appropriate for target residues

Procedure:

- Establish Acceptance Criteria: Define scientifically justifiable residue limits based on analytical method sensitivity, typically including:

- Analytical detection levels (e.g., 10 ppm)

- Biological activity levels (e.g., 1/1000 of normal therapeutic dose)

- No visible residue [12]

Develop Sampling Plan:

- Identify worst-case locations in equipment (hard-to-clean areas, transfer lines, valves)

- Employ swab sampling for direct surface contact or rinse sampling for overall residue recovery

- Document sampling locations with reference to equipment diagrams [12]

Execute Cleaning and Sampling:

- Perform cleaning procedure according to established SOP

- Collect samples immediately after cleaning, documenting time between processing and cleaning

- Include procedural blanks to account for background contamination [12]

Analyze Samples:

- Utilize analytical methods with appropriate sensitivity (HPLC, LC-MS, ICP-MS)

- Target not only primary reactants but also potential by-products and degradants

- Include method validation data demonstrating specificity, accuracy, and precision [12]

Document and Report:

- Compare results against predetermined acceptance criteria

- Investigate any deviations and implement corrective actions

- Establish revalidation schedule based on equipment use and historical data [12]

Protocol 2: Minimizing Contamination in Trace Element Analysis

Adapted from laboratory practices for ICP and ICP-MS analysis [13], this protocol addresses common contamination sources in ultra-trace measurements.

Objective: To minimize introduction of contaminants during sample preparation for trace element analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- ASTM Type I water (resistivity >18 MΩ·cm) [13]

- High-purity acids (ICP-MS grade) [13]

- Fluoropolymer (FEP) or quartz labware [13]

- Powder-free gloves [13]

- Cleanroom environment (preferred) or class 100 laminar flow hood [13]

Procedure:

- Labware Preparation:

- Segregate labware for high-level (>1 ppm) and low-level (<1 ppm) use [13]

- Avoid borosilicate glass for boron and silicon analysis [13]

- Implement automated pipette washing systems to reduce residual contamination compared to manual cleaning [13]

- Pre-clean all labware with high-purity acid (e.g., 10% nitric acid) followed by multiple rinses with high-purity water

Sample Handling:

Reagent Quality Verification:

- Check certificates of analysis for all acids and reagents

- Perform reagent blank analyses to establish background levels

- Avoid hydrochloric acid when possible due to typically higher impurity levels [13]

Environmental Monitoring:

- Regularly analyze procedural blanks to monitor laboratory background

- Implement air particulate monitoring in critical sample preparation areas

- Maintain positive pressure in clean areas to minimize particulate ingress [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Surface Contamination Control

| Material/Reagent | Specification/Grade | Primary Function | Contamination Risks Mitigated |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | ASTM Type I [13] | Diluent, rinse solution | Ionic contamination, Trace elements |

| Nitric Acid | Trace metal grade, ICP-MS grade [13] | Sample digestion, Labware cleaning | Various metal impurities |

| Ammonium Hydroxide | High purity [13] | pH adjustment, Cleaning agent | Metallic impurities |

| Fluoropolymer (FEP) Labware | Metal-free certified [13] | Sample storage, preparation | Boron, silicon, sodium leaching |

| Powder-Free Gloves | Low extractables [13] | Personal protective equipment | Zinc, other particulate contamination |

| High-Purity Solvents | HPLC grade or better | Extraction, Cleaning | Organic residues, Additives |

| Certified Reference Materials | Current expiration dates [13] | Quality control, Calibration | Incorrect analytical results |

| XPS Test Kits | Silicone/fluorocarbon specific [10] | Facility contamination evaluation | Silicone contamination, Surface effects |

The identification and control of surface contaminants represents a critical component in ensuring analytical accuracy and material performance, particularly within the framework of IUPAC guidelines for surface analysis. A systematic approach encompassing proper material selection, standardized cleaning protocols, and validated analytical methods is essential for researchers and drug development professionals. Implementation of the protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provides a foundation for reducing analytical errors, improving product quality, and maintaining regulatory compliance. As analytical techniques continue to advance with increasingly sensitive detection capabilities, vigilance in contamination control becomes ever more critical to generating reliable, defensible scientific data.

Surface analysis is a critical component of materials science, playing a pivotal role in characterizing the outermost atomic layers of solids to understand composition, structure, and chemical state. This technical note provides a detailed overview of four principal surface analysis techniques—X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS), and Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). Framed within the context of developing a comprehensive IUPAC guide for sample preparation, this document serves researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require precise surface characterization for their work. These techniques offer complementary information for investigating surface phenomena, with applications spanning from battery cathode development to pharmaceutical surface characterization, making them indispensable tools in modern analytical science [17] [18].

The exceptional utility of these methods lies in their ability to probe the top 1-10 nanometers of a material, where many critical interactions occur. Each technique operates on different physical principles, offers varying levels of sensitivity, and provides unique information about the sample surface. Proper selection and application of these techniques require a thorough understanding of their fundamental principles, capabilities, and limitations, particularly regarding sample preparation requirements that ensure accurate and reproducible results while maintaining surface integrity.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Specifications

Physical Principles and Information Obtained

Each surface analysis technique exploits distinct physical phenomena to extract information about surface composition and chemistry:

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): This technique operates on the photoelectric effect, where incident X-rays eject core-level electrons from surface atoms. The measured kinetic energy of these photoelectrons provides information about elemental identity, chemical state, and bonding environment. XPS is particularly valuable for determining chemical states and oxidation states of elements present on the surface [19].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES): AES relies on the Auger process, where an incident electron beam creates a core-hole vacancy, followed by a relaxation process that emits a characteristic Auger electron. The kinetic energy of these Auger electrons serves as a fingerprint for elemental identification in the top 3-10 nm of the material. AES is particularly efficient for light element detection and offers exceptional spatial resolution [20] [21].

Ion Scattering Spectroscopy (ISS): ISS is based on the principles of elastic scattering between incident ions and surface atomic nuclei. By measuring the energy and angle of scattered ions, ISS provides information about the elemental composition and structure of the very outermost atomic layer, making it the most surface-sensitive technique available [18].

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): SIMS uses a focused primary ion beam to sputter material from the surface, with a fraction of the ejected particles becoming ionized. These secondary ions are then analyzed by a mass spectrometer, providing extremely sensitive elemental, isotopic, and molecular information from the uppermost atomic layers [22].

Technical Specifications and Comparison

The following table summarizes the key technical specifications and capabilities of the four surface analysis techniques, providing a clear comparison for technique selection:

Table 1: Comparison of Key Surface Analysis Techniques

| Parameter | XPS | AES | ISS | SIMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation | X-rays | Electron beam (3-25 keV) | Ion beam (noble gases) | Ion beam (O₂, Cs⁺) |

| Signal Detected | Photoelectrons | Auger electrons | Scattered ions | Secondary ions |

| Detection Limits | 0.1-1 at% | 0.1-1 at% | Varies with element | ppb-ppm range |

| Depth Resolution | 2-10 nm | 2-20 nm | Single atomic layer | Sub-nm to tens of nm |

| Lateral Resolution | 10-100 µm | ≥10 nm | Varies with instrument | Down to 40 nm |

| Elements Detected | Li and heavier | Li and heavier | Primarily heavier elements | H to U and above |

| Chemical Information | Excellent (chemical states) | Limited | Limited for bonding | Molecular information possible |

| Depth Profiling | With ion sputtering | With ion sputtering | By angle variation | Native capability |

| Quantitative Analysis | Good with standards | Semi-quantitative | Quantitative with calibration | Requires standards |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Guidelines

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable surface analysis data. The following protocols outline essential considerations for each technique:

Universal Preparation Considerations

All ultra-high vacuum (UHV) surface analysis techniques share common sample preparation requirements:

- Clean Handling: Use powder-free gloves and clean tools to prevent surface contamination.

- Size Compatibility: Samples must fit the instrument sample holder, typically less than several millimeters.

- UHV Compatibility: Materials must withstand ultra-high vacuum conditions (<10⁻⁹ torr) without significant outgassing [20].

- Surface Stability: Samples should not degrade or transform under beam exposure during analysis.

Technique-Specific Preparation Methods

XPS Sample Preparation:

- Conducting and insulating samples can typically be analyzed without modification.

- Powders should be pressed into indium foil or mounted on double-sided adhesive tapes.

- Flat surfaces are preferred for quantitative analysis to minimize topography effects.

- Sputter cleaning with Ar⁺ ions may be used to remove adventitious carbon contamination.

AES Sample Preparation:

- Samples must be electrically conductive to prevent charging under electron beam.

- For insulating samples, use specialized mounting techniques such as:

- Surface cleaning with low-energy ion sputtering is often necessary to remove contaminants.

ISS Sample Preparation:

- Surfaces must be atomically clean, often requiring in situ sputter-anneal cycles.

- Flat, well-ordered surfaces yield the best results for structural analysis.

- Special precautions are needed to maintain surface cleanliness during transfer.

SIMS Sample Preparation:

- Minimal special preparation is needed beyond standard UHV compatibility.

- Conductive and insulating materials can be analyzed.

- For insulating samples, electron flood guns may be used for charge compensation.

- Standards with known composition are essential for quantitative analysis.

Instrumental Workflows and Procedures

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for surface analysis experiments, from sample preparation to data interpretation:

Diagram 1: Generalized Surface Analysis Workflow

XPS Analysis Protocol

- Sample Loading: Introduce the sample into the UHV chamber using a load-lock system to maintain main chamber vacuum integrity.

- Survey Scan: Acquire a wide energy range survey spectrum (e.g., 0-1100 eV) to identify all elements present.

- High-Resolution Scans: Collect narrow energy range scans for regions of interest to determine chemical states.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate atomic concentrations using peak areas and elemental sensitivity factors.

- Depth Profiling (if required): Employ monatomic or cluster ion sputtering while intermittently analyzing the newly exposed surface.

AES Analysis Protocol

- SEM Imaging: Use the focused electron beam to obtain secondary electron images and identify regions of interest.

- Point Analysis: Position the electron beam on specific features and acquire Auger spectra.

- Elemental Mapping: Raster the beam across the sample surface while detecting specific Auger electrons to create elemental distribution maps.

- Depth Profiling: Combine with ion sputtering to determine composition as a function of depth.

SIMS Analysis Protocol

- Primary Ion Selection: Choose O₂⁺ primary ions for enhanced positive secondary ions or Cs⁺ for enhanced negative secondary ions [22].

- Analysis Mode Selection:

- Static SIMS: Use low primary ion dose (<10¹³ ions/cm²) to preserve molecular information from the top monolayer.

- Dynamic SIMS: Use higher primary ion dose for bulk composition and depth profiling of trace elements.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the mass-to-charge ratio of ejected secondary ions.

- Depth Profiling: Monitor secondary ion intensities as a function of sputtering time to obtain depth distributions.

Essential Materials and Research Reagents

Successful surface analysis requires specific materials and reagents for sample preparation, mounting, and analysis. The following table details these essential items:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Surface Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Technique Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| Indium Foil | Conductive, malleable substrate for mounting small or powder samples | AES, XPS |

| Conductive Carbon Tape | Sample mounting with electrical continuity to holder | All techniques |

| Double-Sided Adhesive Tape | Mounting insulating samples without conductive coatings | XPS, SIMS |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Source for ion sputter guns for surface cleaning and depth profiling | All techniques |

| Silicon Wafer Substrates | Clean, flat reference substrates for instrument calibration | All techniques |

| Certified Reference Materials | Quantification standards with known composition | All techniques |

| Colloidal Graphite Paint | Creating electrical pathways for charge dissipation on insulators | Primarily AES |

| Ultra-High Purity Solvents | (e.g., methanol, acetone) for ultrasonic cleaning without residue | Sample preparation |

| Copper TEM Grids | Masking insulating samples to minimize charging | AES |

| Gold/Palladium Targets | Thin film deposition for reference samples | Instrument calibration |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Battery Cathode Characterization

The combination of XPS and TOF-SIMS has proven invaluable for studying engineered particle (Ep) battery cathodes. In lithium metal battery systems, these techniques reveal how Ep coatings stabilize electrode-electrolyte interfaces, reduce side reactions, and mitigate transition metal dissolution from high-voltage cathode materials like lithium cobalt oxide (LCO). XPS provides chemical state information about the interface, while TOF-SIMS offers high-resolution detection of organic and inorganic species distribution, enabling researchers to optimize interfacial stability and enhance battery performance and longevity [17].

Defect and Contamination Analysis

AES excels at identifying sub-micrometer particles and defects in electronic devices. Its high spatial resolution (≥10 nm) enables precise elemental analysis of small surface features that can cause device failures. AES can determine oxide layer thickness on electropolished medical devices, analyze bond pads on semiconductor die, and identify grain boundary contamination in metal fractures. The ability to perform small-area depth profiling makes AES particularly valuable for failure analysis in semiconductor and metallurgical applications [21] [23].

Ultra-Sensitive Trace Element Detection

SIMS provides unparalleled sensitivity for trace element and isotopic analysis, with detection limits reaching parts-per-billion levels for many elements. This extreme sensitivity makes SIMS ideal for dopant and contaminant analysis in semiconductors, high-precision isotope ratio measurements, and distribution analysis of trace elements in materials. The technique's high lateral resolution (down to 40 nm) enables detailed imaging of elemental distributions, while its depth profiling capabilities allow characterization of thin film structures with nanometer-scale resolution [22].

Outermost Surface Layer Analysis

ISS uniquely probes the very outermost atomic layer of a material, providing information unavailable with other techniques. This extreme surface sensitivity makes ISS ideal for studying surface segregation, catalyst characterization, thin film growth, and adsorption phenomena. While less sensitive for light elements, ISS provides excellent elemental specificity for heavier elements and can achieve high depth resolution through angle-resolved measurements, making it valuable for understanding surface reactions and interface formation [18].

Technique Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate surface analysis technique requires careful consideration of the specific analytical needs:

For chemical state information and quantitative analysis of the top 2-10 nm: Select XPS, particularly for insulating materials or when chemical bonding information is crucial [19].

For high spatial resolution elemental analysis of the top 3-10 nm on conductive samples: Choose AES, especially for defect analysis, small particles, or features smaller than 1 micrometer [20] [21].

For extreme surface sensitivity analyzing only the outermost atomic layer: Employ ISS for studying surface segregation, adsorption, or catalyst surfaces [18].

For ultimate detection sensitivity (ppb levels) and isotopic information: Utilize SIMS, particularly for trace element analysis, depth profiling, or when molecular information is needed in static mode [22].

For comprehensive characterization of complex materials: Consider using multiple complementary techniques, such as the combined XPS and TOF-SIMS approach successfully applied to battery materials [17].

The following decision diagram provides a systematic approach for selecting the most appropriate surface analysis technique:

Diagram 2: Surface Analysis Technique Selection Guide

XPS, AES, ISS, and SIMS represent powerful complementary techniques for surface characterization, each with unique strengths and applications. XPS excels in providing chemical state information and quantitative analysis, AES offers exceptional spatial resolution for conductive materials, ISS provides unparalleled sensitivity to the outermost atomic layer, and SIMS delivers extreme elemental sensitivity and depth resolution. Understanding the fundamental principles, technical capabilities, and sample preparation requirements for each technique is essential for obtaining meaningful surface analysis data. As surface science continues to advance, these techniques will remain indispensable for materials development, failure analysis, and fundamental surface studies across diverse scientific and industrial fields. Proper technique selection, coupled with appropriate sample preparation protocols, enables researchers to extract maximum information from material surfaces and interfaces, driving innovation in technology and science.

Practical Sample Preparation Methods for Biomedical Surface Analysis

In the field of surface chemical analysis, the pre-treatment of samples is a critical step that directly influences the reliability and accuracy of analytical results. As defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), surface analysis techniques require specimens with well-defined surfaces free from artifacts introduced during preparation [24]. Ex-situ preparation, where these processes occur separately from the analysis instrument, encompasses mechanical and chemical techniques such as cutting, polishing, and etching. This article outlines standardized protocols and application notes for these essential methods, providing a structured guide for researchers and scientists, particularly those in drug development and materials science, to achieve surfaces fit for purpose according to international quality assurance standards [25].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Chemical Etching for Precision Metal Components

Chemical etching is a subtractive machining process that utilizes thermochemical reactions to selectively remove material from a metal substrate, achieving high precision without affecting the material's inherent properties [26].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Material Selection: Begin with a metal sheet suitable for the final component's requirements. The process accommodates a wide thickness range, typically from 0.010 mm to 2.5 mm [26].

- Pre-cleaning: Chemically clean and degrease the metal sheet to remove all debris, waxes, and rolling oils. This is critical for ensuring subsequent proper adhesion of the photoresist [26].

- Lamination: Apply an ultraviolet (UV)-light-sensitive photoresist layer to the entire surface of the pre-cleaned sheet. Ensure a uniform and blemish-free application, as any imperfections can lead to etchant penetration and part compromise [26].

- Printing: Align a photo tool stencil containing the desired component design with the laminated sheet. Expose the assembly to UV light, which crosslinks the photoresist in the exposed areas, transferring the design pattern onto the sheet [26].

- Developing: Wash the sheet in a developer solution to dissolve and remove the unexposed, soft photoresist. This step reveals the bare metal in the areas designated for etching while the hardened resist protects the features to be preserved [26].

- Etching: Spray the developed sheet with a corrosive etchant chemistry, most commonly ferric chloride. The etch time is a determined by a technician based on variables including metal type, grade, thickness, and the size of the features to be formed [26].

- Stripping: Following etching, remove the remaining hardened photoresist from the metal sheet using an appropriate chemical stripper, revealing the final etched components [26].

- Inspection and Finishing: Subject the components to visual and dimensional inspection using optical equipment. If required, subsequent finishing processes such as plating, passivation, or heat treatment can be performed [26].

Chemo-Mechanical Polishing for Semiconductor Substrates

Chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP) is a critical process for planarizing semiconductor substrates, such as tungsten wafers, combining chemical and mechanical actions to achieve ultra-smooth surfaces.

Detailed Protocol:

Table 1: Key Components of a Typical Tungsten Polishing Composition

| Component Category | Example | Function | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abrasive Grain | Silica, Alumina, Zirconia | Mechanical abrasion | Mean particle diameter ≤ 200 nm |

| Oxidizing Agent | Hydrogen peroxide, Iron(III) nitrate | Oxidizes metal surface for easier removal | Concentration 0.5-3.0% by mass |

| Organic Acid | Oxalic acid, Citric acid | Forms soluble metal complexes | Prevents redeposition of removed material |

| Dispersing Agent | Various polymers | Maintains suspension stability | Prevents particle agglomeration |

| pH Adjustor | Ammonia, Potassium hydroxide | Optimizes chemical activity | Typically adjusted to pH 2.0-5.5 |

- Composition Preparation: Formulate the polishing slurry by combining the components listed in Table 1 in deionized water. The specific formulation must be tailored to the substrate material (e.g., tungsten, tungsten alloy) [27].

- Substrate Mounting: Secure the semiconductor substrate onto a polishing holder, ensuring it is firmly and evenly held.

- Polishing Process: Feed the polishing slurry onto a polishing platen covered with a polyurethane pad. Press the substrate face-down against the rotating pad. The process parameters—including downforce pressure, platen speed, and slurry flow rate—are carefully controlled to achieve the desired material removal rate and surface planarity [27].

- Post-Polishing Cleaning: After polishing, thoroughly rinse the substrate with deionized water to remove all abrasive particles and chemical residues from the surface. This step is crucial to prevent contamination.

- Quality Control: Inspect the polished surface using techniques such as powder X-ray diffraction for crystallographic analysis and other metrology tools to measure surface roughness and ensure it meets the required specifications [27].

Dry Etching for Semiconductor Patterning

Dry etching is a vital process in semiconductor fabrication for the removal of material from a masked pattern on a substrate.

Process Overview:

This technique involves placing the patterned substrate in a vacuum chamber and exposing it to a bombardment of ions (often plasma-based) [28]. The ions interact with the surface, physically sputtering and/or chemically reacting with the unmasked material, thereby selectively etching it away. The highly anisotropic nature of dry etching allows for the creation of features with vertical sidewalls, which is essential for advanced micro- and nano-electronics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The efficacy of ex-situ preparation methods is highly dependent on the reagents and materials used. The table below details essential solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Ex-Situ Surface Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ferric Chloride (FeCl₃) | Corrosive etchant | A common etchant for a wide range of metals; concentration and temperature control are critical for etch rate and finish [26]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Oxidizing agent | Used in polishing slurries to oxidize metal surfaces, making them more amenable to mechanical removal [27]. |

| Photoresist | UV-sensitive polymer mask | Used in etching and lithography to protect selected areas of the substrate from the etchant; available in positive and negative tones [26]. |

| Silica & Alumina Nanoparticles | Abrasive grains | Provide the mechanical action in polishing slurries; particle size and distribution are key to controlling removal rate and surface scratch quality [27]. |

| Oxalic & Citric Acids | Organic complexing agents | Chelate with metal ions in polishing slurries, preventing redeposition of removed material and enhancing removal rates [27]. |

| Ionized Gas (e.g., Ar⁺, CF₄) | Etchant species in plasma | The reactive medium in dry etching processes; gas selection determines the chemical (reactive) or physical (sputtering) nature of the etch [28]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision pathways involved in selecting and applying the primary ex-situ preparation methods for surface analysis.

Pathway for Ex-Situ Surface Preparation Selection

This workflow guides the user from the initial sample state to the most appropriate preparation technique, based on the desired outcome and material properties.

The meticulous application of mechanical and chemical ex-situ preparation methods—including polishing, cutting, and etching—is a foundational requirement for generating high-quality, reliable data in surface analysis. Adherence to standardized protocols, such as those detailed in this document, ensures that sample surfaces are fit for their intended analytical purpose. Furthermore, compliance with established guidelines for single-laboratory method validation, as outlined by IUPAC and other international bodies, is indispensable for demonstrating the reliability of these preparation techniques within a comprehensive quality assurance framework [25]. By integrating these robust, well-defined procedures into their research and development workflows, scientists and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the integrity and reproducibility of their surface analysis results.

Within the field of surface science, the accurate characterization of material interfaces is fundamentally dependent on the initial condition of the sample. In-situ preparation under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions comprises a suite of techniques designed to create atomically clean and well-defined surfaces immediately prior to analysis, thereby preventing contamination from ambient exposure. These methods are crucial for obtaining reliable and reproducible data on surface composition, structure, and electronic properties. The integrity of surface analysis, a cornerstone of modern research from semiconductors to biomaterials, is predicated on meticulous sample preparation [29]. Adherence to standardized protocols, such as those outlined in metrological guidelines for purity assignment, ensures the traceability and validity of experimental results, connecting fundamental research directly to application-driven standards [30]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for three core in-situ UHV techniques: cleavage, fracture, and heating.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table catalogues the essential reagents, materials, and equipment required for the in-situ preparation techniques described in this guide.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for In-Situ UHV Preparation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| UHV System | Provides the necessary environment (pressures typically <10⁻⁹ mbar) to prevent surface contamination by gases. | Base pressure, chamber volume, and number of ports for analysis and preparation techniques are critical. |

| Sample Mounts & Holders | Secure and position the sample within the UHV system. | Must be compatible with high temperatures and fabricated from high-purity, low-vapor-pressure materials (e.g., Ta, Mo, W). |

| Cleavage Blades & Anvils | Used to apply a localized force for cleaving brittle crystals along their natural crystal planes. | Typically made of hardened steel or tungsten carbide. Geometry is specific to the sample and cleavage mechanism. |

| In-Situ Fracture Stage | A specialized fixture for applying stress to notched samples to induce brittle fracture. | Must be robust enough to generate high stress while maintaining UHV integrity. |

| Direct Heating Filaments | Resistive heating elements placed directly behind or in contact with the sample. | Fast heating rates; risk of sample contamination if filament outgasses. |

| Electron Bombardment Heater | Heats the sample by directing a beam of high-energy electrons onto its rear surface. | Can achieve very high temperatures (>2000°C); requires careful power control to avoid melting. |

| High-Purity Wires (Ta, Mo, W) | Used for spot-welding samples to holders for secure mechanical and thermal contact. | High melting point and good electrical conductivity are essential. |

| Sputter Ion Gun | Source of inert gas ions (e.g., Ar⁺) for removing surface layers via sputtering, often paired with annealing. | Ion energy and current density must be optimized to prevent ion implantation and surface damage. |

Protocols for In-Situ Cleavage

Application Notes

In-situ cleavage is a mechanical separation technique used to expose fresh, pristine surfaces of single-crystal or layered materials inside the UHV chamber. This method is highly effective for materials with defined cleavage planes, such as graphite, transition metal dichalcogenides, and many semiconductors (e.g., GaAs, Si) [29]. The primary advantage is the creation of large, atomically flat and clean surfaces that are free from solvent or thermal processing history. This makes it ideal for studying intrinsic surface properties, electronic band structures, and the physics of two-dimensional materials [31].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Ex-Situ Preparation:

- Sample Shaping: For a "pin and anvil" setup, shape the single-crystal sample into a rectangular rod (typical dimensions: 1x1x10 mm).

- Notching: Using a fine wire saw or diamond blade, carefully cut a shallow notch (approximately 10-20% of the cross-section) at the desired cleavage position on the rod.

- Solvent Cleaning: Ultricate the sample in a series of high-purity solvents (e.g., acetone, followed by isopropanol) to remove organic contaminants from handling and shaping.

- Mounting: Secure the notched sample onto a UHV-compatible cleavage stage using a high-temperature ceramic adhesive or a mechanical clamp.

In-Situ Cleavage in UHV:

- Transfer and Pump-Down: Introduce the loaded stage into the UHV system and pump down to the base pressure (typically <1x10⁻⁹ mbar) to ensure a contaminant-free environment.

- Alignment: Precisely align a hardened steel or tungsten carbide cleavage blade with the notch on the sample. The blade should be positioned to apply a tensile stress at the notch root.

- Cleavage Execution: Actuate the blade to apply a controlled, sharp impulse or slow pressure to the notch. Successful cleavage is often audibly indicated by a "click" and visually confirmed by a change in the sample's appearance.

- Post-Cleavage Verification: Transfer the freshly cleaved surface to an analysis position (e.g., for SEM, XPS, or STM) to confirm surface quality, flatness, and the absence of contaminants.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Cleavage of Common Materials

| Material | Cleavage Plane | Notch Depth (Typical) | Difficulty | Expected Surface Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) | (0001) | Optional | Easy | Atomically flat terraces over µm areas. |

| Mica (Muscovite) | (001) | Optional | Easy | Large, flat surfaces, can be charged. |

| GaAs | (110) | 10-15% | Moderate | Flat, with characteristic atomic reconstruction. |

| MoS₂ | (0001) | 15-20% | Moderate | Semi-conducting, layered surface. |

| Si | (111) | 20-25% | Difficult | Requires precise notch control; can shatter. |

Workflow Visualization

Protocols for In-Situ Fracture

Application Notes

In-situ fracture is specifically designed for the analysis of grain boundaries, interfaces, and the bulk composition of metals, alloys, and intermetallic compounds. Unlike cleavage, which follows a single crystal plane, fracture propagates through the path of least resistance, which is often a region of weakness like a grain boundary or a precipitate interface. This technique is therefore vital for studies of hydrogen embrittlement in pipeline steels [32], segregation phenomena, and mechanical failure analysis. The key measured property is often the fracture toughness in different environments, which can be severely degraded by hydrogen [32].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Sample Design and Notching:

- Geometry: Machine a compact tension (CT) or Charpy-style sample with a well-defined notch. Standardized dimensions are critical for comparative fracture toughness measurements.

- Notch Preparation: The notch root should be as sharp as possible, often achieved by fatiguing a pre-notched sample or using a razor blade to introduce a fine scratch. This ensures a controlled crack initiation point.

- Surface Finish: Polish the sample surfaces to a mirror finish to allow for subsequent microscopic analysis of the fracture path.

In-Situ Fracture in UHV:

- Mounting: Secure the notched sample into a dedicated UHV fracture stage. This stage must be capable of applying a high tensile or bending load.

- Cooling (Optional): For studies on hydrogen embrittlement, the sample may need to be cooled to cryogenic temperatures to retain dissolved hydrogen introduced by pre-charging, simulating conditions relevant to gas transmission pipelines [32].

- Fracture Execution: Actuate the fracture mechanism (e.g., a screw-driven plunger or a piezoelectric hammer) to apply a rapid, high-force impact to the sample, causing brittle fracture.

- Surface Analysis: Immediately transfer the fracture surface to an analytical instrument (e.g., SEM or AES) to examine the fracture morphology (ductile dimpling vs. brittle cleavage) and chemistry of grain boundaries before any contamination occurs.

Table 3: Fracture Parameters for Different Material Classes

| Material Class | Sample Geometry | Fracture Type | Key Analysis | Environmental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Strength Steels | Compact Tension (CT) | Brittle (Intergranular) | Grain boundary segregation, hydrogen content. | Hydrogen pre-charging drastically reduces fracture toughness [32]. |

| Ductile Metals (Al, Cu) | Charpy / 3-point bend | Ductile (Microvoid coalescence) | Inclusion chemistry, dimple size. | Less sensitive to UHV environment; fracture for bulk analysis. |

| Intermetallics (Ni₃Al) | Notched rod | Mixed (Brittle & Ductile) | Bonding strength at grain boundaries. | UHV prevents oxide formation on fresh surfaces. |

Workflow Visualization

Protocols for In-Situ Heating (Annealing)

Application Notes

In-situ heating, or annealing, is a versatile UHV technique used for a multitude of purposes: degassing a sample after introduction from air, ordering a surface to create specific atomic reconstructions, sintering deposited nanoparticles, and inducing chemical reactions or desorption. The process involves raising the sample temperature to precisely controlled values for defined durations. The thermal energy enables atoms to diffuse across the surface, healing defects and allowing the system to reach a lower-energy, more ordered state. This is a critical step for preparing well-defined surfaces for catalytic studies or thin film growth.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Sample Mounting for Thermal Contact:

- Ensure excellent thermal and mechanical contact between the sample and the heater. This is often achieved by spot-welding thin foil samples or mounting crystals with high-temperature conductive paste or clamps.

- Attach a thermocouple (Type K, C, or R) directly to the front face of the sample using a UHV-compatible ceramic adhesive or by spot-welding to a thin foil. Avoid relying on heater temperature, as it can be significantly different from the actual sample temperature.

Degassing and Annealing Cycle:

- Initial Degas: After pump-down, slowly heat the sample to a moderate temperature (e.g., 150-300°C for metals) and hold for several hours. This step desorbs water vapor and other volatile contaminants from the surface and the sample holder itself.

- Monitor Pressure: The UHV chamber pressure will rise during this process due to outgassing. Continue until the pressure stabilizes at or near the base pressure.

- High-Temperature Anneal: Ramp the temperature to the final annealing value. This is material-specific (e.g., 500-700°C for Au(111) reconstruction, >900°C for Si(100) cleaning).

- Controlled Cool-Down: After the annealing time elapses, lower the temperature slowly. Rapid cooling can introduce thermal stress and defects.

Surface Quality Assessment:

- Use Low-Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) to verify the presence of a sharp, well-ordered surface reconstruction.

- Use XPS or AES to confirm the removal of surface contaminants such as carbon or oxygen.

Table 4: Annealing Protocols for Common Surfaces

| Surface | Degas Temperature / Time | Annealing Temperature / Time | Purpose | Characteristic Verification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au(111) | 200°C / 2 hours | 550°C / 10-15 minutes | Form herringbone surface reconstruction. | LEED: (1x1) pattern; STM: large terraces with reconstruction. |

| Si(100) | 300°C / 3 hours | 900-1200°C / 1-5 minutes | Remove native oxide, create (2x1) dimer row reconstruction. | LEED: sharp (2x1) pattern; AES: no O KLL peak. |

| Cu(110) | 150°C / 2 hours | 500°C / 10 minutes | Create a clean, ordered surface for catalysis studies. | LEED: (1x1) pattern; XPS: minimal O 1s and C 1s signals. |

| Stainless Steel | 300-500°C / 5-10 hours | N/A | Bulk degassing of the vacuum chamber itself. | System base pressure improvement. |

Workflow Visualization

Within the framework of IUPAC-guided research on sample preparation for surface analysis, the selection and execution of a surface cleaning protocol are foundational to achieving reliable and reproducible data. Contaminants, including adsorbed atmospheric gases, hydrocarbons, and oxides, can significantly alter surface composition and electronic properties, leading to erroneous analytical results. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for two critical cleaning techniques: noble gas ion sputtering and solvent cleaning. The former is a physical method ideal for achieving atomically clean surfaces in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environments, while the latter is a chemical approach crucial for the initial removal of soluble contaminants. Adherence to the standardized nomenclature and practices detailed herein ensures the integrity of surface-sensitive analyses across scientific and industrial disciplines.

Solvent Cleaning Protocols

Solvent cleaning serves as a critical first step in most surface preparation workflows, aimed at removing soluble contaminants like oils, greases, and dust without altering the substrate's physical microstructure [14] [33]. Its effectiveness is governed by several international standards, which provide a common language for specifying and verifying cleanliness.

Key Standards and Visual Descriptions

The most widely recognized standards are the joint standards from NACE International and SSPC (now merged into AMPP), as well as ISO 8501 [14] [33]. The following table summarizes the primary solvent and mechanical preparation standards.

Table 1: Key Solvent and Mechanical Surface Preparation Standards

| Standard Designation | Description | Comparable ISO 8501 Grade |

|---|---|---|

| SSPC-SP 1 | Solvent Cleaning: Removal of all visible oil, grease, dirt, and soluble contaminants [14] [33]. | (Preparatory step) |

| SSPC-SP 2 | Hand Tool Cleaning: Removal of loose mill scale, rust, and coating using non-powered tools [14] [33]. | St 2 |

| SSPC-SP 3 | Power Tool Cleaning: Removal of loose mill scale, rust, and coating using powered hand tools [14]. | St 3 |

| ISO 8501 St 2 | Thorough hand tool scraping and brushing to bare metal [33]. | SSPC-SP 2 |

| ISO 8501 St 3 | Very thorough hand tool scraping and brushing to bare metal [33]. | SSPC-SP 3 |

For more aggressive cleaning to bare metal, which may be required for analysis, blast cleaning standards are used. It is critical to note that the numbering between different standards does not necessarily correlate, and higher numbers do not always indicate a cleaner surface [14].

Table 2: Key Blast Cleaning Standards for Surface Analysis

| Standard Designation | Description | Acceptable Staining | Comparable ISO 8501 Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| NACE No. 1/SSPC-SP 5 | White Metal Blast Cleaning: Uniformly free of all visible foreign matter [14] [33]. | 0% | Sa 3 |

| NACE No. 2/SSPC-SP 10 | Near-White Metal Blast Cleaning: Free of all except for light shadows on ≤5% of each unit area [14] [33]. | ≤5% | Sa 2½ |

| NACE No. 3/SSPC-SP 6 | Commercial Blast Cleaning: Free of all except for stains on ≤33% of each unit area [14] [33]. | ≤33% | Sa 2 |

| NACE No. 4/SSPC-SP 7 | Brush-Off Blast Cleaning: Removal of loose material, tight adherents may remain [14]. | (Tight adherents remain) | Sa 1 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SSPC-SP 1 Solvent Cleaning

This protocol is designed to achieve a surface condition compliant with SSPC-SP 1, serving as a essential preparatory step for subsequent analysis or further surface treatment [33].

2.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Solvent Cleaning

| Item | Function / Specification | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents | To dissolve and remove organic contaminants without leaving residue [33]. | Acetone, Methyl Ethyl Ketone (MEK), Isopropyl Alcohol. |

| Lint-Free Cloths/Wipes | Physical application and wiping of solvents. | - |

| Brushes | Agitation and cleaning of intricate geometries. | Non-shedding bristles. |

| Dull Putty Knife | To test for and remove loosely adherent contaminants [14] [33]. | - |

2.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Initial Inspection & Gross Removal: Visually inspect the surface for bulk contamination. Use a scraper or cloth to remove large deposits of oil, grease, or dirt.

- Solvent Application: Apply a suitable residue-free solvent (e.g., acetone or MEK) to a lint-free cloth or brush. Do not pour solvent directly onto the surface, as this can spread contamination.

- Wiping: Wipe the surface thoroughly with the solvent-dampened cloth, using a circular motion. Frequently fold the cloth to present a clean surface. Repeat until no visible residue remains on the cloth after wiping.

- Inspection and Verification: The final surface must be free of all visible oil, grease, dirt, and dust [14] [33]. A simple verification test involves drawing a line with chalk from a clean area, through the cleaned area, and onto another clean area. A decrease in the line's intensity in the cleaned zone indicates residual oil or grease requiring further cleaning [33].

- Drying: Allow the surface to air dry completely before any subsequent processing or analysis.

2.2.3 Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence for selecting and applying solvent and mechanical cleaning standards within a research context.

Noble Gas Ion Sputtering Protocols

Noble gas ion sputtering is a cornerstone technique for preparing atomically clean surfaces in UHV systems, essential for techniques like XPS, AES, and SIMS. It utilizes inert gas ions, typically argon, to physically eject atoms from the surface, thereby removing contaminants and overlayers.

Fundamentals and Quantitative Parameters