Physical vs. Experimental Surfaces: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the critical distinction between a 'physical surface'—the intrinsic, outermost layer of a material—and an 'experimental surface'—the abstract, model-based representation of a system's behavior.

Physical vs. Experimental Surfaces: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the critical distinction between a 'physical surface'—the intrinsic, outermost layer of a material—and an 'experimental surface'—the abstract, model-based representation of a system's behavior. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we dissect the foundational concepts, showcase methodological applications in pharmaceutical science (including drug combination analysis and solid-form selection), address common pitfalls and optimization strategies in experimental design, and establish robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing these intents, this guide aims to enhance the rigor, predictability, and success of research reliant on surface-based analysis.

Defining the Divide: Core Concepts of Physical and Experimental Surfaces

What is a Physical Surface? The Intrinsic Material Boundary

In the realms of materials science, chemistry, and solid-state physics, a physical surface represents the intrinsic boundary where a material terminates and transitions to its external environment, typically vacuum, gas, or liquid. This boundary is not merely a geometric plane but a region of dramatically altered atomic and electronic structure that governs a material's interactions and functional properties. The physical surface arises from the sharp termination of the periodic crystal lattice of the bulk material, creating a region where the symmetric potential experienced by electrons is broken. This disruption leads to the formation of new electronic states and atomic configurations not found in the bulk, fundamentally dictating properties such as catalytic activity, adsorption, corrosion resistance, and electronic behavior [1] [2].

Understanding the physical surface is crucial for differentiating it from the experimental surface encountered in research. While the physical surface constitutes the ideal, intrinsic boundary of a material, the experimental surface represents the surface as measured and characterized through specific analytical techniques, which inevitably introduces methodological biases, artifacts, and limitations. This distinction forms a core challenge in surface science: bridging the gap between the intrinsic nature of the physical surface and our experimental observations of it [2] [3].

The Electronic Structure of Physical Surfaces

Origin and Theory of Surface States

The termination of a perfectly periodic crystal lattice creates a weakened potential at the material boundary, allowing for the formation of distinct electronic states known as surface states. These states are localized at the atom layers closest to the surface and decay exponentially both into the vacuum and the bulk crystal [1]. According to Bloch's theorem, electronic states in an infinite periodic potential are Bloch waves, extending throughout the crystal. At the surface, this periodicity is broken, giving rise to two qualitatively different types of solutions to the single-electron Schrödinger equation [1]:

- Bloch-like states that extend into the crystal and terminate in an exponentially decaying tail reaching into the vacuum.

- Surface states that decay exponentially both into the vacuum and the bulk crystal, with wave functions localized close to the crystal surface.

These surface states exist within forbidden energy gaps of semiconductors or local gaps of the projected band structure of metals. Their energies lie within the band gap, and within the crystal, these states are characterized by an imaginary wavenumber, leading to an exponential decay into the bulk [1].

Shockley States and Tamm States

Surface states are historically categorized into two types, named after their discoverers, which differ in their theoretical description rather than their fundamental physical nature [1]:

- Shockley States: These states arise as solutions to the Schrödinger equation within the framework of the nearly free electron approximation. They are associated with the change in electron potential due solely to crystal termination and are well-suited for describing normal metals and some narrow gap semiconductors. Within the crystal, Shockley states resemble exponentially decaying Bloch waves [1].

- Tamm States: In contrast, Tamm states are calculated using a tight-binding model, where electronic wave functions are expressed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). This approach is suitable for describing transition metals and wide gap semiconductors. Qualitatively, Tamm states resemble localized atomic or molecular orbitals at the surface [1].

Topological Surface States

A significant advancement in surface science has been the discovery of topological surface states. Materials can be classified by a topological invariant derived from their bulk electronic wave functions. When strong spin-orbital coupling causes certain bulk energy bands to invert, this topological invariant can change. At the interface between a topological insulator (non-trivial topology) and a trivial insulator, the interface must become metallic. Moreover, the surface state must possess a linear Dirac-like dispersion with a crossing point protected by time reversal symmetry. Such a state is exceptionally robust under disorder and cannot be easily localized [1].

Atomic and Crystallographic Structure of Surfaces

The atomic structure of a physical surface is often distinct from a simple termination of the bulk crystal. Several key phenomena define this structure:

Surface Reconstruction and Relaxation

Upon creation, surface atoms frequently reposition themselves to minimize the surface energy, leading to:

- Surface Relaxation: A change in the distance between the first and second crystal planes compared to the bulk interplanar spacing. This can involve either contraction or expansion [2].

- Surface Reconstruction: A more substantial rearrangement where surface atoms adopt a periodic structure different from the bulk crystal plane. This occurs when the surface structure found in the bulk is unstable, and atoms move to new positions to form a lower-energy configuration [2].

Defects and Surface Morphology

Real-world physical surfaces are not perfect; they contain various defects that significantly influence their properties. These include [2]:

- Steps

- Kinks

- Vacancies

- Ad-atoms

The concentration and type of these defects are critical parameters affecting surface reactivity and other functional behaviors.

The Physical-Experimental Duality in Surface Research

A central paradigm in surface science is recognizing the distinction between the intrinsic physical surface and the experimental surface observed through characterization techniques. This duality presents several fundamental "gaps" that researchers must bridge.

The Pressure and Materials Gap

In fields like heterogeneous catalysis, two significant challenges have long been identified [2]:

- The Pressure Gap: This refers to the disparity between surface studies conducted under Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) conditions (e.g., 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁹ torr) and industrial processes that operate at much higher pressures (e.g., 1-100 atmospheres). The question is whether UHV studies on model systems can accurately predict behavior at practical operating pressures.

- The Materials Gap (or Structure Gap): This describes the contrast between ideal, single-crystal surfaces used as model systems in fundamental research and the complex, practical surfaces often consisting of nanoparticles exposing different facets or being non-crystalline.

The Dimensionality Gap: 2D vs. 3D Characterization

A critical and recently quantified gap arises from the dimensional limitations of characterization techniques. Traditional analysis has relied heavily on 2D imaging, but emerging 3D characterization reveals significant biases, as shown in Table 1 [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of 2D vs. 3D Characterization of Twin Microstructures in Titanium

| Feature | 2D Characterization Findings | 3D Characterization Findings | Implication of the Dimensionality Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Connectivity | Reduced cross-grain and in-grain twin connectivity; appears as isolated twins and pairs. | High interconnectivity of domains into networks spanning the full reconstruction volume. | 2D views systemically underestimate connectivity, misrepresenting network morphology. |

| Twin Contacts | Undercounts the number of cross-grain contacts per twin. | Reveals a densely interconnected fingerprint with more contacts. | Alters understanding of how twin networks mediate plastic response and failure modes. |

| Network Morphology | Suggests a more disconnected network. | Shows complex, tortuous twin chains with long, complex 3D paths. | 2D analysis biases understanding of mechanisms driving network growth. |

This dimensionality gap demonstrates that conventional 2D analyses provide an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of the true, three-dimensional physical surface and its associated microstructures [3].

Methodologies for Probing the Physical Surface

A wide array of techniques has been developed to characterize the physical surface, each providing specific insights into its composition, structure, and electronic properties. These methodologies, and their typical applications, form the scientist's toolkit for experimental surface research.

Core Characterization Technique Groups

Advanced characterization can be organized into groups targeting specific physical and chemical aspects of functional solid materials, as detailed in Table 2 [4].

Table 2: Groups of Submicroscopic Characterization Techniques for Solid Materials

| Target Aspect | Example Techniques | Key Information Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology & Pore Structure | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Aberration-Corrected Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (AC-STEM), Surface Adsorption | Surface topography, particle shape, porosity, and pore size distribution. |

| Crystal Structure | X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystallographic phase, lattice parameters, crystal structure, preferred orientation (texture). |

| Chemical Composition & Oxidation States | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental identity, concentration, and chemical/oxidation state. |

| Coordination & Electron Structures | X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS), Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS) | Local atomic environment, coordination numbers, bonding, electronic structure. |

| Bulk Elemental & Magnetic Structure | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Mössbauer Spectroscopy | Identification of specific isotopes, magnetic properties, local chemical environment. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Surface science research relies on meticulously prepared samples and specific analytical environments. Key components of this toolkit include:

- Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) Systems: Essential for creating and maintaining clean, well-defined surfaces by eliminating contamination from ambient gases [2].

- Single Crystals: Used as model substrates to provide a well-defined, atomically flat starting point for studying fundamental surface processes [2].

- Sputtering Sources & Evaporators: Equipment for the controlled removal of surface contaminants (sputtering) or deposition of thin films with atomic precision [2].

- Calibrated Gas Dosing Systems: Allow for the precise introduction of specific gases onto a clean surface to study adsorption and reaction kinetics [2].

- Standard Reference Materials (e.g., Si/SiO₂ wafers, Gratings): Crucial for calibrating the lateral and vertical dimensions of surface profilometers and microscopes [5].

In Situ and Operando Methodologies

A significant trend in modern surface science is the shift from studying static surfaces to exploring dynamic systems. In situ (in the original position) and operando (under operating conditions) characterization methodologies allow researchers to track the structural evolution of a surface during various applications, such as catalytic reactions or mechanical strain [4]. This provides a more direct correlation between the state of the physical surface and its performance under realistic conditions, helping to bridge the pressure and materials gaps.

Workflow for Surface Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for moving from a real-world sample to a comprehensive understanding of the physical surface, highlighting the role of different characterization groups.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for physical surface analysis, showing the convergence of different characterization groups to build a comprehensive model.

The physical surface is fundamentally defined as the intrinsic material boundary where the bulk crystal periodicity terminates, giving rise to unique electronic states and atomic structures that govern a material's interactive properties. A comprehensive understanding requires the integration of multiple advanced characterization techniques to build a complete picture of its morphology, crystallography, and chemical and electronic composition.

A critical challenge in surface science remains the distinction between this intrinsic physical surface and the experimental surface measured by our tools. Key gaps—including the pressure gap, materials gap, and the recently quantified dimensionality gap between 2D and 3D analysis—underscore the fact that all experimental data provides a filtered view of physical reality. The future of surface research lies in the continued development of in situ and operando methods, the increased application of 3D characterization to reveal true microstructural fingerprints, and the integration of high-throughput experimentation with data science. These approaches will progressively narrow these gaps, offering a clearer and more accurate window into the complex world of the intrinsic material boundary.

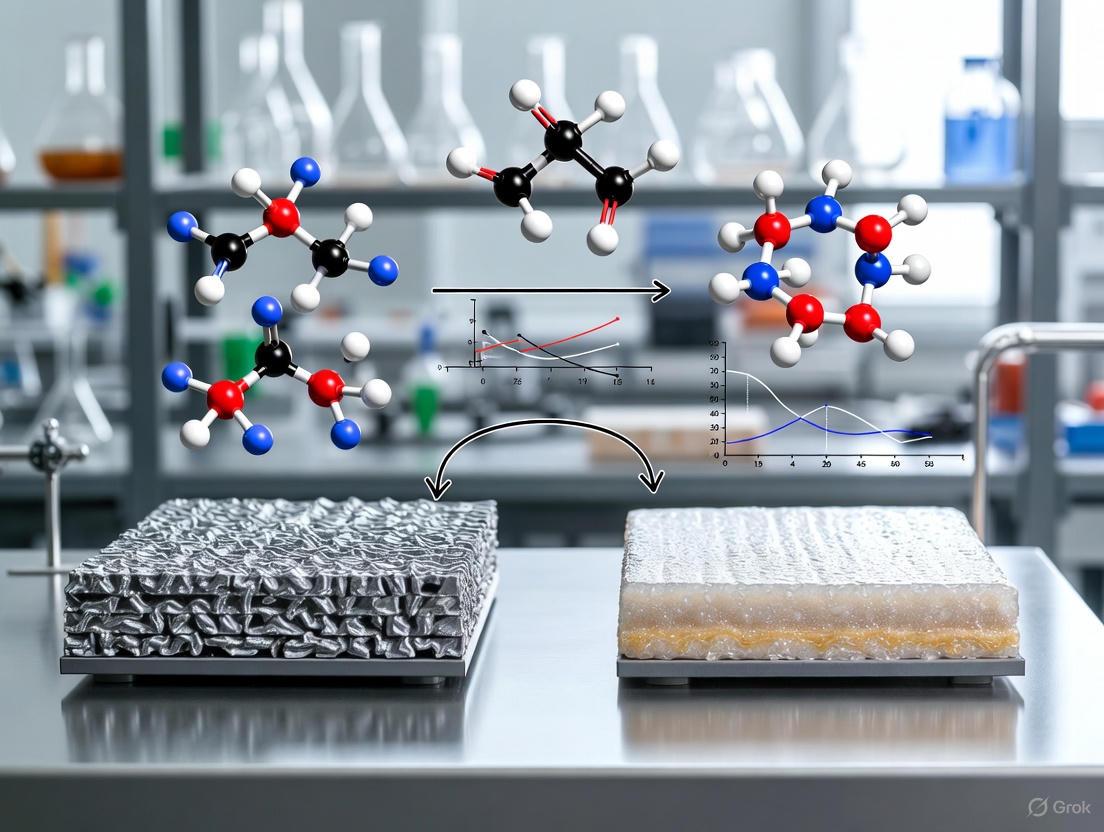

In materials science and pharmaceutical development, the concept of a "surface" operates on two distinct yet interconnected levels. The physical surface represents the tangible, atomic-level boundary of a material, characterized by its topography, chemical composition, and atomic arrangement. In contrast, the experimental surface constitutes an abstract, computational model—a theoretical construct built from experimental data and predictive simulations that represents surface properties and behaviors under specific conditions. This distinction is crucial for modern drug development, where understanding dissolution behavior, stability, and bioavailability depends on increasingly sophisticated digital design approaches.

The pharmaceutical industry faces significant challenges in bringing new compounds to market, particularly with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) exhibiting poor solubility characteristics. [6] Natural products like cannabinoids often demonstrate desirable pharmacological effects but present formulation challenges due to low melting points and limited solubility. [6] The emerging paradigm combines experimental techniques with computational modeling to create accurate experimental surface models that predict API behavior without requiring extensive physical testing, accelerating development timelines while reducing material requirements. [7] [6]

The Physical Surface in Pharmaceutical Sciences

The physical surface of pharmaceutical crystals represents the direct interface between the solid dosage form and the dissolution medium, ultimately governing the API's release rate and absorption potential. Traditional surface characterization focuses on quantifying physical attributes through techniques including:

- Surface roughness and topography measured via confocal microscopy (e.g., Zeiss Axio CSM 700) providing 3D surface maps [8]

- Chemical composition analysis using scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM/EDX) [8]

- Crystalline structure identification through X-ray diffraction (XRD) with specialized radiation sources (αCo radiation with Kα1 = 1.789 Å for Co-Cr alloys; αCu radiation with Kα = 1.54 Å for Ti alloys) [8]

- Phase analysis and quantification performed using Rietveld refinements with specialized software (e.g., MAUD) [8]

These techniques provide the foundational data points for constructing accurate experimental surface models, capturing the multidimensional nature of material interfaces.

The experimental surface transcends physical measurements by integrating disparate data sources into a unified computational representation. This abstract model incorporates not only topographic and chemical information but also predictive elements regarding dissolution behavior, surface energy, and interaction potentials. Advanced characterization symposiums highlight growing interest in spatially-resolved and in-situ characterization techniques that provide dynamic, rather than static, surface models. [9]

The power of the experimental surface lies in its capacity to function as a digital twin of physical reality, enabling researchers to run simulations, predict behaviors under varying conditions, and optimize formulations without continuous physical experimentation. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development where API availability may be limited during early stages. [6]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Physical vs. Experimental Surface Paradigms

| Characteristic | Physical Surface | Experimental Surface |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Tangible, atomic-level boundary | Abstract, computational model |

| Primary Data Sources | Direct measurement techniques (XRD, SEM, confocal microscopy) | Integrated computational and experimental datasets |

| Temporal Dimension | Static representation at measurement time | Dynamic, can model time-dependent processes |

| Key Advantage | Ground truth measurement | Predictive capability and design optimization |

| Common Techniques | SEM/EDX, XRD, confocal microscopy, DSC | CSD-Particle, computational morphology prediction, surface interaction modeling |

| Pharmaceutical Application | Solid form characterization, impurity detection | Dissolution rate prediction, form selection, manufacturing optimization |

Case Study: Cannabigerol Solid Forms and Dissolution Behavior

Experimental Design and Methodology

A recent investigation by Zmeškalová et al. (2025) exemplifies the integrated approach to experimental surface modeling. [7] [6] The study examined three solid forms of the biologically active molecule cannabigerol: the pure API and two co-crystals with pharmaceutically acceptable coformers (piperazine and tetramethylpyrazine). The research employed a multifaceted methodology:

1. Thermal Characterization: Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) established the thermal properties of the multicomponent materials, revealing that both co-crystals demonstrated higher melting points than pure cannabigerol—a critical factor for manufacturing processes. [6]

2. Dissolution Testing: Experimental measurements quantified the dissolution rates of all three solid forms, showing nearly triple the dissolution rate for the tetramethylpyrazine co-crystal compared to pure cannabigerol, while the piperazine co-crystal showed no significant improvement. [6]

3. Structural Analysis: Single crystal X-ray diffraction elucidated the molecular geometries, packing arrangements, and intermolecular interaction patterns in all three solid forms. [6]

4. Computational Surface Modeling: The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre's CSD-Particle suite predicted particle shapes and modeled surface properties, calculating interaction potentials and polar functional group distribution across major crystal facets. [6]

Quantitative Results and Surface-Based Interpretation

The experimental data revealed significant differences in performance between the solid forms, with the tetramethylpyrazine co-crystal demonstrating superior dissolution characteristics. Computational surface analysis provided the explanatory link: the predominant surface of the tetramethylpyrazine co-crystal exhibited higher incidence of polar functional groups and stronger interactions with water molecules based on Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) data, correlating directly with the enhanced dissolution rate observed experimentally. [6]

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Cannabigerol Solid Forms [6]

| Solid Form | Melting Point | Relative Dissolution Rate | Key Surface Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Cannabigerol | Low | 1.0 (baseline) | Lower polarity surface functionality |

| Piperazine Co-crystal | Higher | No significant increase | Limited polar group exposure |

| Tetramethylpyrazine Co-crystal | Higher | ~3.0 | Increased polar functional groups and water interactions |

This case study demonstrates how the experimental surface model—derived from both computational and experimental techniques—provides explanatory power that neither approach could deliver independently. The abstract surface representation successfully rationalized the observed dissolution behavior, moving beyond descriptive characterization to predictive capability.

Methodological Framework: Integrated Experimental-Computational Workflow

The transformation of physical surface measurements into predictive experimental surface models follows a systematic workflow that integrates multiple data streams and analytical techniques. This methodology represents the state-of-the-art in surface engineering for pharmaceutical applications.

Experimental Protocol for Surface Characterization

Sample Preparation and Surface Treatment

- Laser marking and electropolishing procedures prepare samples for analysis

- Standardized sample zones (typically square areas) ensure measurement consistency

- Multiple measurements (minimum three zones) establish statistical significance [8]

Topographical and Chemical Analysis

- Confocal Microscopy: Surface roughness quantification and 3D topography mapping through optical sectioning (e.g., Zeiss Axio CSM 700) [8]

- SEM/EDX: High-resolution surface imaging coupled with elemental composition analysis (e.g., Zeiss EVO MA 25 with Bruker EDX) [8]

- X-ray Diffraction: Crystalline phase identification and structural determination using appropriate radiation sources (Cu Kα = 1.54 Å for organic compounds) [8]

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry: Thermal property analysis including melting points, polymorphic transitions, and stability assessment [6]

Computational Surface Modeling Protocol

Structural Informatics and Prediction

- Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) mining for comparative structural analysis and interaction propensity [6]

- CSD-Particle implementation for crystal morphology prediction and surface property calculation [6]

- Surface interaction modeling with water and biological media to predict dissolution behavior [6]

Data Integration and Model Validation

- Experimental validation of predicted crystal habits through comparison with physically characterized materials

- Correlation of computational surface properties with observed dissolution rates

- Iterative refinement of computational parameters based on experimental discrepancies

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Successful implementation of the experimental surface paradigm requires specialized instrumentation, computational tools, and analytical techniques. This toolkit enables the transition from physical characterization to predictive modeling.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Experimental Surface Modeling [8] [9] [6]

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function in Surface Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Characterization | Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction | Determines molecular arrangement and packing in crystal lattice |

| Surface Topography | Confocal Microscopy (e.g., Zeiss Axio CSM 700) | Measures surface roughness and creates 3D topographic maps |

| Chemical Analysis | SEM/EDX (e.g., Zeiss EVO MA 25 with Bruker EDX) | Determines surface elemental composition and distribution |

| Thermal Analysis | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Characterizes thermal stability, polymorphic transitions |

| Computational Prediction | CSD-Particle Suite (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre) | Predicts crystal morphology and models surface properties |

| Data Mining | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Provides structural informatics for surface interaction analysis |

| In-Situ Characterization | Micro-Raman Spectroscopy, Advanced TEM | Enables real-time surface analysis during processes |

| Nanomechanical Testing | Nanoindentation, FIB-machined structures | Quantifies mechanical properties of surfaces and thin films |

Advanced characterization techniques continue to evolve, with particular emphasis on in-situ methods that provide real-time surface analysis during processes and under service conditions. [9] The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches represents the next frontier in surface modeling, enabling more accurate predictions from smaller experimental datasets. [10]

The experimental surface paradigm represents a fundamental shift in pharmaceutical materials science, transforming surfaces from static physical boundaries into dynamic, predictive models. This approach enables rational design of pharmaceutical products with optimized performance characteristics, particularly for challenging APIs with poor inherent solubility.

The case study of cannabigerol solid forms demonstrates how integrated experimental-computational workflows can successfully link molecular-level surface characteristics to macroscopic performance metrics like dissolution rate. As digital design tools continue to mature, the experimental surface will play an increasingly central role in reducing development timelines, conserving valuable API during early development, and ultimately delivering more effective pharmaceutical products to patients.

While current approaches still require experimental validation, the trajectory points toward increasingly predictive surface models that will eventually enable true in silico design of optimal solid forms, representing the future of surface engineering in pharmaceutical sciences.

Surface science, as a unified discipline, is the study of physical and chemical phenomena that occur at the interface of two phases, including solid–liquid interfaces, solid–gas interfaces, solid–vacuum interfaces, and liquid–gas interfaces [11]. This field inherently bridges the gap between two foundational domains: surface physics and surface chemistry. While surface physics focuses on physical interactions and changes at interfaces, investigating phenomena such as surface diffusion, surface reconstruction, surface phonons and plasmons, and the emission and tunneling of electrons, surface chemistry is primarily concerned with chemical reactions at interfaces, including adsorption, desorption, and heterogeneous catalysis [11] [12].

The distinction between a "physical surface" and an "experimental surface" is fundamental to understanding this convergence. The physical surface is the theoretical interface with inherent properties and behaviors governed by the laws of physics and chemistry. In contrast, the experimental surface represents the practical manifestation and probe of this interface within the constraints of measurement techniques, which can influence the very properties being observed. This article traces the historical trajectory of how these two domains, once more distinct, have merged through shared methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and a common goal of understanding the complex interface.

Historical Foundations and Early Divergence

The field of surface chemistry finds its early roots in applied heterogeneous catalysis, pioneered by Paul Sabatier on hydrogenation and Fritz Haber on the Haber process [11]. Irving Langmuir, another founding figure, made seminal contributions to the understanding of monolayer adsorption, with the scientific journal Langmuir now bearing his name [11]. Their work was fundamentally driven by chemical reactivity and the practical goal of controlling surface reactions.

A pivotal moment in the maturation of surface science was the development and application of ultra-high vacuum (UHV) techniques. These methods were necessary to create a clean, controlled environment to study surfaces without interference from contaminant layers [11]. The ability to prepare and maintain well-defined surfaces was a critical prerequisite for both physical and chemical studies, providing a common ground for experimentalists from both backgrounds. The 2007 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Gerhard Ertl for his investigations of chemical processes on solid surfaces, including the adsorption of hydrogen on palladium using Low Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), symbolizes the ultimate recognition of this interdisciplinary field [11]. Ertl's work demonstrated how physical techniques could unravel complex chemical mechanisms, effectively bridging the historical gap.

The Methodological Convergence

The most significant driver for the convergence of surface physics and surface chemistry has been the development and shared use of sophisticated analytical techniques. These tools provide atomic-scale insights into both the structural (physical) and compositional (chemical) properties of surfaces, blurring the traditional disciplinary lines.

Table 1: Key Analytical Techniques in Modern Surface Science

| Technique | Primary Domain | Key Information Provided | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | Surface Physics | Real-space imaging of surface topography and electronic structure at the atomic level. | [11] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface Chemistry | Elemental composition and chemical bonding states of the top few nanometers of a surface. | [11] [12] |

| Low Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED) | Surface Physics | Long-range order and atomic structure of crystal surfaces. | [11] |

| Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) | Surface Chemistry | Elemental identity and composition of surface layers. | [11] |

| Grazing-Incidence Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (GISAXS) | Surface Physics | Size, shape, and orientation of nanoparticles on surfaces. | [11] [13] |

Exemplar Technique: GISAXS Analysis of Ion Bombardment

The power of modern surface analysis is exemplified by GISAXS, which probes the structure factor of surfaces evolving during processes like ion bombardment. This technique is particularly powerful for studying early-time dynamics during pattern formation on surfaces [13].

The evolution of the surface height (h(\mathbf{r},t)) during the linear regime is described by: [ \frac{\partial \tilde{h}(\mathbf{q},t)}{\partial t} = R(\mathbf{q})\tilde{h}(\mathbf{q},t) + \beta(\mathbf{q},t) ] where (\tilde{h}(\mathbf{q},t)) is the Fourier transform of the surface height, (R(\mathbf{q})) is the amplification factor (dispersion relation), and (\beta(\mathbf{q},t)) is a stochastic noise term [13]. The structure factor (S(\mathbf{q},t)) measured by GISAXS evolves as: [ \langle S(\mathbf{q},t)\rangle = \left[S(q,0) + \frac{\alpha}{2R(\mathbf{q})}\right] \exp[2R(\mathbf{q})t] - \frac{\alpha}{2R(\mathbf{q})} ] where (\alpha) is the noise amplitude [13]. By fitting the experimental (S(\mathbf{q},t)) to this equation, the dispersion relation (R(\mathbf{q})) can be extracted and compared directly to theoretical models, enabling researchers to distinguish between competing physical mechanisms such as sputtering, atom redistribution, surface diffusion, and ion-induced stress [13].

The Modern Synthesis: A Quantitative and Interdisciplinary Paradigm

The contemporary landscape of surface science is characterized by a fully integrated, quantitative approach. The reliance on a single, potentially speculative technique is now recognized as insufficient. Instead, the "considerable added power" comes from combining methods like scanning probe microscopy and theoretical calculations with more traditional quantitative experiments that provide precise data on composition, vibrational properties, adsorption/desorption energies, and electronic and geometrical structure [14].

This synthesis is evident in the study of electrochemistry, where the behavior of an electrode–electrolyte interface is probed by combining traditional electrochemical techniques like cyclic voltammetry with direct observations from spectroscopy, scanning probe microscopy, and surface X-ray scattering [11]. Similarly, in geochemistry, the adsorption of heavy metals onto mineral surfaces is studied using in situ synchrotron X-ray techniques and scanning probe microscopy to predict contaminant travel through soils with molecular-scale accuracy [11]. This interplay ensures that theoretical models of the physical surface are constantly refined and validated against data from experimental surfaces.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Surface Science

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal Surfaces (e.g., Pt, Pd, Si) | Well-defined model substrates to study fundamental processes without the complexity of real-world materials. | Heterogeneous Catalysis, Model Electrodes [11] |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) Systems | Creates a contamination-free environment (≤10⁻⁷ Pa) to prepare and maintain clean surfaces for analysis. | Fundamental Surface Physics and Chemistry [11] |

| Synchrotron Radiation | High-intensity, tunable-energy X-ray source for high-resolution scattering and spectroscopy studies of buried interfaces. | GISAXS, HAXPES, XSW [11] [13] |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers | Model organic surfaces with controlled composition and structure for studying adhesion, lubrication, and biomaterial interfaces. | Surface Engineering, Tribology [11] |

The historical journey of surface science demonstrates a definitive convergence of surface physics and surface chemistry into a cohesive, interdisciplinary field. This fusion has been driven by the shared use of powerful analytical techniques capable of probing the atomic-scale structure and reactivity of interfaces. The distinction between the theoretical "physical surface" and the measured "experimental surface" remains a critical conceptual framework, guiding the interpretation of data and the development of more accurate models. Today, the most significant advances occur at this intersection, where quantitative physical measurements inform our understanding of chemical mechanisms, and chemical insights drive the exploration of new physical phenomena. The continued refinement of techniques like GISAXS and HAXPES promises to further bridge any remaining gaps, solidifying a unified approach to understanding and engineering the complex world at the interface.

In scientific research, the concept of a "surface" embodies a fundamental dichotomy between its physical reality and its experimental representation. The physical surface is a complex, multi-scale boundary layer of a material, defined by its innate topographical features, chemical composition, and behavioral properties under environmental interactions. In contrast, the experimental surface is a conceptual model constructed through measurement principles, characterization parameters, and analytical interpretations that inevitably simplify this physical reality for systematic study. This distinction is not merely philosophical; it has profound implications for how researchers across disciplines—from materials science to pharmaceutical development—design experiments, interpret data, and build predictive models. Understanding the relationship between actual surface properties and their parameterized representations is essential for advancing surface science and its applications. This guide examines the key properties that define both physical and experimental surfaces, providing a framework for navigating their complex interrelationships through quantitative characterization, standardized methodologies, and functional correlations.

Fundamental Properties of Physical Surfaces

Physical surfaces represent the actual boundary where a material interacts with its environment, possessing intrinsic properties that exist independently of measurement. These properties can be categorized into three interconnected domains: topography, composition, and behavior.

Surface Topography

Surface topography encompasses the three-dimensional geometry and microstructural features of a surface across multiple scales, typically classified as macroroughness (Ra ~10 μm), microroughness (Ra ~1 μm), and nanoroughness (Ra ~0.2 μm) [15]. This hierarchical structure represents the "fingerprint" of a material's manufacturing history and significantly influences its functional capabilities. At the nanoscale, surface features affect molecular interactions, while at microscales, they govern mechanical and tribological behaviors. Macroscale topography influences aesthetic perception and fluid dynamics. The complexity of natural surfaces often requires advanced characterization methods beyond simple height measurements, incorporating lateral and hybrid parameters to fully describe feature distribution and orientation [15] [5].

Surface Composition

Surface composition refers to the chemical and molecular makeup of the outermost material layers, which often differs substantially from bulk composition due to segregation, oxidation, or contamination processes. This composition dictates fundamental material properties including surface energy, reactivity, catalytic activity, and biocompatibility. In dental implants, for instance, titanium surfaces may be nitrided or acid-etched to create specific chemical properties that enhance biocompatibility and osseointegration [15]. Surface composition interacts synergistically with topography—for example, a chemically patterned surface with specific wettability properties may be further enhanced by hierarchical microstructures that amplify these effects.

Surface Behavior

Surface behavior emerges from the interaction between topography, composition, and external stimuli, manifesting as functional properties such as friction, wear resistance, adhesion, wettability, and corrosion resistance. The behavioral response represents the ultimate determinant of a surface's suitability for specific applications. For instance, the race for the surface between bacterial cells and mammalian cells on implant materials demonstrates how surface properties dictate biological responses—with smoother surfaces (nitrided, as machined, or lightly acid-etched) generally proving more favorable than rougher ones (strong acid etched or sandblasted/acid etched) in balancing bacterial resistance with tissue integration [15].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Physical Surfaces

| Property Category | Key Parameters | Functional Significance | Characterization Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topography | Height parameters (Sa, Sq), Spatial parameters (Str), Hybrid parameters (Sdq) | Friction, adhesion, optical perception, biocompatibility | Multi-scale nature, measurement instrument limitations |

| Composition | Elemental distribution, chemical states, molecular arrangement | Reactivity, corrosion resistance, surface energy, catalytic activity | Surface contamination, depth resolution, representative sampling |

| Behavior | Friction coefficient, contact angle, wear rate, adhesion strength | Tribological performance, wettability, durability, biological response | Context-dependent behavior, complex interaction mechanisms |

Experimental Surface Characterization

Measurement Principles and Instrumentation

Experimental surface characterization bridges the physical reality of surfaces with quantifiable parameters through various measurement modalities. The choice of instrumentation involves critical trade-offs between resolution, field of view, measurement speed, and potential surface damage.

Tactile methods, particularly stylus profilometry (SP), historically dominated industrial applications due to their robustness and standardization. However, they present limitations in measurement speed and potential for surface damage on soft materials [5]. Optical methods including confocal microscopy (CM), white light interferometry (WLI), focus variation microscopy (FV), and coherence scanning interferometry (CSI) have emerged as predominant techniques in research environments, offering non-contact, areal measurements with high vertical resolution and speed [5]. These now account for approximately 70% of applications in scientific studies of functional surfaces [5]. Advanced techniques such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provide nanometer-scale resolution but face limitations in field of view, measurement time, and operational complexity [15] [16].

Table 2: Surface Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Lateral/Vertical Resolution | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stylus Profilometry (SP) | Physical tracing with diamond tip | 0.1-10 μm / 1 nm-0.1 μm | Standardized roughness measurement, process control | Surface damage, slow speed, limited to 2D profiles |

| Confocal Microscopy (CM) | Optical sectioning with pinhole elimination of out-of-focus light | 0.1-0.4 μm / 1-10 nm | Transparent materials, steep slopes, biological surfaces | Limited to moderately rough surfaces, lower speed than WLI |

| White Light Interferometry (WLI) | Interference pattern analysis using white light source | 0.3-3 μm / 0.1-1 nm | High-speed areal measurements, rough surfaces | Noise on transparent materials, step height ambiguity |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Physical probing with nanoscale tip | 0.1-10 nm / 0.01-0.1 nm | Nanoscale topography, molecular resolution, force measurements | Very small scan area, slow measurement, surface contact |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Electron beam scanning with secondary electron detection | 1-10 nm / N/A | Ultra-high magnification, compositional mapping | Vacuum requirements, conductive coatings often needed, no direct height measurement |

Characterization Parameters and Their Limitations

The transformation of physical surface data into quantitative parameters introduces another layer of abstraction between reality and representation. Amplitude parameters (e.g., Sa, Sq, Sz) describing vertical characteristics remain the most widely used due to their historical precedence and conceptual simplicity, yet they provide incomplete information about feature distribution and orientation [15] [5]. Spatial parameters (e.g., Str, Sal) describe the dominant directionality and spacing of surface features, critically important for anisotropic functional behaviors like fluid transport or optical scattering. Hybrid parameters (e.g., Sdq, Sdr) combine vertical and lateral information to better characterize the complexity of surface geometry, with developed interfacial area ratio (Sdr) particularly valuable for predicting adhesion and wettability. Functional parameters based on the Abbott-Firestone curve (e.g., Sk, Spk, Svk) attempt to directly correlate topography with performance characteristics like lubricant retention, wear resistance, and load-bearing capacity [5].

Despite the proliferation of standardized parameters (>100 in ISO standards), a significant gap persists between parameter availability and functional understanding. Many industries continue to rely predominantly on Ra/Sa values despite their well-documented limitations in capturing functionally relevant topographic features [5]. This "parameter rash" [5] creates challenges in selecting the most appropriate descriptors for specific applications, often leading to either oversimplification or unnecessary complexity in surface specification.

Quantitative Contrast: Physical Properties vs. Model Parameters

The relationship between physical surface properties and their experimental representations can be quantitatively examined across multiple domains. The following tables synthesize data from surface science research to illustrate these critical distinctions.

Table 3: Topographic Properties vs. Experimental Parameters

| Physical Topographic Property | Experimental Parameter | Measurement Limitations | Typical Value Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature height distribution | Sa (Arithmetic mean height) | Insensitive to feature shape and spacing | 0.01 μm (polished) to 25 μm (coated) |

| Surface texture directionality | Str (Texture aspect ratio) | Dependent on measurement area and sampling | 0 (strongly directional) to 1 (isotropic) |

| Peak sharpness and valley structure | Sku (Kurtosis) and Ssk (Skewness) | Requires sufficient sampling statistics for accuracy | Sku: 1.5 (spiky) to 5 (bumpy); Ssk: -3 (porous) to +3 (peaked) |

| Effective surface area | Sdr (Developed interfacial area ratio) | Resolution-dependent, underestimates nanoscale features | 0% (perfectly flat) to >100% (highly textured) |

| Hybrid topography characteristics | Sdq (Root mean square gradient) | Sensitive to noise and filtering | 0° (flat) to 90° (vertical) |

Table 4: Compositional and Behavioral Properties vs. Experimental Parameters

| Physical Property | Experimental Parameter/Method | Functional Correlation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface energy/wettability | Contact angle measurement | Predicts adhesion, coating uniformity, biocompatibility | 30° (hydrophilic) to >120° (superhydrophobic) |

| Frictional behavior | Friction coefficient (μ) | Depends on both topography and material properties | 0.01 (lubricated) to >1 (high friction) |

| Wear resistance | Volume loss (mm³) under standardized load | Related to hardness, toughness, and topography | Varies by material and application |

| Adhesion performance | Peel strength (N/mm) or pull-off force (N) | Critical for coatings, composites, and bonding | Application-specific thresholds |

| Chemical composition | XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) | Determines reactivity, corrosion resistance, catalysis | Elemental atomic percentages |

Case Studies: From Physical Properties to Fitted Responses

Case Study 1: Visual Perception of Surface Color

The perception of surface color in complex scenes demonstrates sophisticated interactions between physical properties and cognitive processing. Research on representative surface color perception of real-world materials reveals that humans judge overall surface color using simple image measurements rather than complex physical analyses [17]. Despite heterogeneous structures in natural surfaces (soil, grass, skin), observers consistently identify a representative color that correlates strongly with the saturation-enhanced color of the brightest point in the image (excluding high-intensity outliers) [17].

This perceptual mechanism was validated through matching experiments using original natural images and their statistically synthesized versions (Portilla-Simoncelli-synthesized and phase-randomized images). Surprisingly, the perceived representative color showed no significant differences between original and synthetic stimuli except for one sample, despite dramatic impairments in perceived shape and material properties in the synthetic images [17]. This demonstrates that the visual system employs efficient heuristics rather than physical simulation for routine color judgments, with important implications for computer graphics, material design, and visual neuroscience.

Diagram 1: Surface color perception pathway

Case Study 2: Pharmaceutical Activity Landscapes

In pharmaceutical research, the relationship between chemical structure (surface composition and topography at molecular level) and biological activity represents a critical application of surface-property modeling. The pharmacological topography constitutes a two-dimensional mapping of chemical structure against biological activity, where activity cliffs appear as discontinuities—structurally similar compounds with unexpectedly large differences in biological effects [18].

Quantitative analysis of these landscapes employs similarity (s) and variation (d) metrics weighted by chemical similarity (c). Research reveals that activity variation (d) maintains above-average values more consistently than similarity (s) as chemical similarity increases, particularly in the transitional region (c ∈ [0.3, 0.64]) where rises in d are significantly greater than drops in s [18]. This "canyon" representation of activity landscapes provides a mathematical framework for predicting the probability of distinctive drug interactions, with important implications for drug design, repurposing, and safety assessment. The method identifies drug pairs where small structural modifications produce dramatic therapeutic differences, such as the tricyclic compounds Promethazine, Chlorpromazine, and Imipramine, which possess distinct therapeutic profiles despite high chemical similarity [18].

Case Study 3: Bacterial vs. Mammalian Cell Adhesion on Implant Surfaces

The "race for the surface" between bacterial and mammalian cells on dental implants demonstrates how topographic parameters influence biological responses. Research on five representative implant surfaces (nitrided, as-machined, lightly acid-etched, strongly acid-etched, and sandblasted/acid-etched) revealed that surface topography modulates differential responses based on cell size and membrane properties [15].

Bacterial cells (approximately 1μm diameter) with rigid membranes struggle to interact with complex nano-sized topographies where their size exceeds accessible adhesion cavities. In contrast, mammalian cells (gingival fibroblasts) with highly elastic membranes (up to 100μm spreading) accommodate complex topographies through actin microspikes that sense surfaces before adhesion occurs [15]. This fundamental difference means that rougher surfaces (strong acid etched or sandblasted/acid etched) generally favor bacterial adhesion over cell integration, while smoother surfaces (nitrided, as machined, or lightly acid etched) better support the "race for the surface" by mammalian cells [15]. These findings demonstrate the importance of multi-parameter topographic analysis beyond simple Sa values for predicting biological performance.

Diagram 2: Biological response to implant surface topography

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comprehensive Surface Characterization Protocol

Based on analyzed research, an effective surface characterization protocol should integrate multiple complementary techniques:

Primary Topography Mapping: Begin with non-contact optical methods (CM or WLI recommended) for areal surface measurement across representative regions (minimum 3 locations). Use 20×20μm to 250×250μm scan areas depending on feature scale with Gaussian filtering (ISO 25178) to separate roughness from waviness [15] [5].

Multi-Parameter Analysis: Calculate amplitude (Sa, Sq), spatial (Str), and hybrid (Sdr, Sdq) parameters following ISO 25178 standards. Include Abbott-Firestone curve parameters (Sk, Spk, Svk) for functional assessment of bearing ratio and lubricant retention [5].

Nanoscale Validation: For surfaces with suspected nanofeatures, employ AFM on selected 1×1μm to 10×10μm regions to validate optical measurements and characterize sub-resolution features.

Compositional Analysis: Perform XPS survey scans with monochromatic AlKα source (1486.7 eV), 300μm spot size, pass energy 200eV, and C1s referencing at 285.0eV for elemental quantification and chemical state identification [15].

Functional Testing: Conduct application-specific behavioral tests (contact angle measurements for wettability, adhesion assays, or tribological tests) correlating results with topographic and compositional parameters.

Visual Perception Experimental Protocol

To investigate perceived surface properties like color and gloss, researchers can adapt the methodology from Honson et al. [19]:

Stimulus Generation: Create 3D rendered surfaces with systematically varied specular roughness, mesoscopic relief height, and orientation to light source using perceptually uniform CIE LCH color space [19].

Psychophysical Procedure: Implement a matching paradigm where observers adjust reference stimuli (e.g., spherical objects) to match perceived lightness and chroma of test surfaces across multiple hue conditions (red, green, blue) [19].

Data Collection: Record matches across multiple trials (minimum 10 repetitions) and observers (minimum 5 observers with normal color vision).

Model Fitting: Analyze results through weighted linear combinations of perceived gloss and specular coverage to account for variations in perceived saturation and lightness across different hue conditions [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Materials for Surface Research

| Item/Category | Specification Guidelines | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Samples | Certified roughness standards (ISO 5436-1), calibrated step heights | Instrument calibration and measurement validation | Essential for cross-technique and cross-laboratory comparison |

| Surface Characterization Kits | Multiple surface finishes (polished, etched, textured, coated) | Method development and controlled experimentation | Dental implant studies used Ti discs with 5 treatments [15] |

| Optical Profilometers | White light interferometry or confocal microscopy systems | Primary areal surface topography measurement | Dominant in research (70% of studies) [5] |

| Fractal Analysis Software | MATLAB toolboxes or specialized surface analysis packages | Quantification of surface complexity across scales | Critical for food, porous materials, biological surfaces [16] |

| GTM/Chemography Platforms | Generative Topographic Mapping software with chemical descriptors | Visualization of structure-activity relationships in drug design | Creates predictive property landscapes from high-dimensional data [20] |

The dichotomy between physical surfaces and their experimental representations represents both a challenge and opportunity for scientific advancement. While physical surfaces embody infinite complexity across scales, experimental surfaces provide the essential abstraction needed for systematic analysis, prediction, and design. The most significant advances in surface science occur when researchers maintain critical awareness of the limitations inherent in parameterized representations while leveraging their power for functional correlation. Future progress will depend on developing more sophisticated characterization methods that better capture multi-scale relationships, establishing clearer correlations between parameter combinations and functional outcomes, and creating new visualization tools that help researchers navigate complex surface-property relationships. By embracing both the physical reality of surfaces and the experimental models needed to study them, researchers across disciplines can design better materials, optimize manufacturing processes, and develop more predictive computational models of surface-mediated phenomena.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Approaches and Real-World Applications

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) for Analyzing Drug Combinations and Synergy

Quantitative evaluation of how drugs combine to elicit a biological response is crucial for modern drug development, particularly in areas like cancer and infectious diseases where combination therapy affords greater efficacy with potential reduction in toxicity and drug resistance [21]. Traditional evaluations of drug combinations have predominantly relied on index-based methods such as Combination Index (CI) and Bliss independence, which distill combination experiments down to a single metric classifying interactions as synergistic, antagonistic, or additive [21]. However, these approaches are now recognized to be fundamentally biased and unstable, producing misleadingly structured patterns that lead to erroneous judgments of synergy or antagonism [21].

The distinction between physical surface research and experimental surface research provides crucial context for understanding the value of RSM. Physical surface research investigates tangible, directly measurable properties of material surfaces, whereas experimental surface research in drug combination studies involves constructing mathematical response surfaces from empirical data to model relationships between input variables (drug doses) and outputs (biological effects) across a multi-dimensional design space [22] [23]. This empirical modeling approach enables researchers to navigate complex biological response landscapes that cannot be directly observed physically but must be inferred through carefully designed experiments and statistical modeling.

Response Surface Methodology represents a more robust, unbiased, statistically grounded framework for evaluating combination experiments [21]. Through parametric mathematical functions of each drug's concentration, RSMs provide a complete representation of combination behavior at all doses, moving beyond simple synergy/antagonism designations to offer greater stability and insight into combined drug action [21].

Theoretical Foundations of Response Surface Methodology

Core Principles and Historical Development

Response Surface Methodology comprises a collection of mathematical and statistical techniques for modeling and optimizing systems influenced by multiple variables [22]. Originally developed by Box and Wilson in the 1950s, RSM emerged from practical industrial needs to link experimental design with optimization, creating formal statistical procedures for process improvement in chemical engineering and manufacturing [22] [23]. The methodology focuses on designing experiments, fitting mathematical models to empirical data, and identifying optimal operational conditions by quantifying how input variables jointly affect responses [22].

In pharmaceutical applications, RSM enables researchers to systematically explore the relationship between multiple input factors (e.g., drug concentrations, administration timing) and measured biological responses (e.g., cell viability, enzyme inhibition) [24]. Unlike traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches, RSM varies all factors simultaneously according to structured experimental designs, enabling efficient detection of interaction effects between variables that would otherwise be missed [23].

Comparison of Major Synergy Analysis Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Major Methodologies for Analyzing Drug Combinations

| Method Category | Key Methods | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index-Based | Combination Index (CI), Bliss Volume, Loewe Additivity, Zero Interaction Potency (ZIP) | Distills combination experiment to single interaction metric | Simple interpretation; Widely adopted; Computational simplicity | Structured bias; Unstable predictions; Divergent conclusions based on curve shape [21] |

| Response Surface Models | URSA, GRS, BRAID, MuSyC | Parametric mathematical function describing response across all dose combinations | Complete response representation; Statistical robustness; Reduced bias; Mechanistic insight [21] | Increased complexity; Larger experimental requirements; Steeper learning curve |

The Meaning of Synergy in Pharmacological Context

The term "synergy" carries different connotations across research contexts. Formally, a synergistic interaction occurs when compounds produce a larger effect in combination than expected from their isolated behavior, requiring a model of non-interaction that accounts for the nonlinear dose-effect relationship [21]. The Loewe additivity model remains the pharmacological gold standard, largely because it assumes additive interaction when a compound is combined with itself [21].

In practical drug discovery contexts, "synergy" often simply indicates an observed response greater than achievable with single agents alone—a distinct meaning from formal pharmacological synergy [21]. This definitional variance underscores the importance of specifying the null model and experimental framework when reporting combination effects.

Limitations of Traditional Index-Based Methods

Patterned Bias in Combination Index (CI) Methods

Simulation studies reveal that CI methods produce structured bias leading to erroneous synergy judgments. When combining drugs with different Hill slopes but identical EC₅₀ values in theoretically additive combinations, CI methods incorrectly identify synergy at 50% effect levels, additivity at 90% effect, and antagonism at 99% effect levels [21]. Similarly, combining drugs differing in maximum efficacy consistently produces false synergy conclusions [21]. These patterned biases stem from flawed assumptions about constant-ratio combination behavior in Loewe additive surfaces.

Patterned Bias in Bliss Independence Methods

Bliss independence frequently yields divergent conclusions compared to Loewe-based methods and RSMs because it employs different fundamental principles [21]. For example, when combining drugs with maximum efficacies of 0.35 and 0.7, Bliss independence predicts a combined effect of 0.815 at high concentrations—judged as antagonistic—while simultaneously judging lower dose combinations as synergistic [21]. These reproducible deviation patterns reflect disagreements between non-interaction models rather than true mechanistic interactions, creating analytical artifacts driven solely by variations in single-agent dose-response curve shapes.

Empirical Performance Comparison

A comprehensive evaluation using the Merck OncoPolyPharmacology Screen (OPPS)—comprising over 22,000 combinations from 38 drugs tested across 39 cancer cell lines—demonstrated RSM superiority in capturing biologically meaningful interactions [21]. When combination metrics were used to cluster compounds by mechanism of action, RSM-based approaches (except MuSyC's alpha2 parameter) consistently outperformed index-based methods [21]. The BRAID method's Index of Achievable Efficacy (IAE), a surface integral over the fitted response surface, achieved the best performance, indicating that RSMs more effectively capture the true interaction patterns reflective of underlying biological mechanisms [21].

Response Surface Methodology: Experimental Design and Implementation

Fundamental Experimental Designs for RSM

Proper experimental design forms the foundation of effective RSM application. The most prevalent designs include:

Central Composite Design (CCD): Extends factorial designs by adding center points and axial (star) points, allowing estimation of linear, interaction, and quadratic effects [22]. CCD can be arranged to be rotatable, ensuring uniform prediction variance across the experimental region [22]. Variations include circumscribed CCD (axial points outside factorial cube), inscribed CCD (factorial points scaled within axial range), and face-centered CCD (axial points on factorial cube faces) [22].

Box-Behnken Design (BBD): Efficiently explores factor space with fewer experimental runs than full factorial designs, particularly valuable when resources are constrained [22]. For three factors, BBD requires approximately 13 runs compared to 27 for full factorial, making it practically advantageous in pharmaceutical research with expensive compounds [24].

Factorial Designs: Serve as foundational elements for screening significant variables before implementing more comprehensive RSM designs [22]. Full factorial designs explore all possible combinations of factor levels, while fractional factorial designs examine subsets when screening large numbers of factors [25].

Step-by-Step RSM Implementation Protocol

Implementing RSM involves a systematic sequence of steps [25]:

Problem Definition and Response Selection: Clearly define research objectives and identify critical response variables (e.g., percentage cell viability, inhibitory concentration, therapeutic window).

Factor Screening and Level Selection: Identify key input factors (drug concentrations, ratios, timing) and determine appropriate experimental ranges based on preliminary data.

Experimental Design Selection: Choose appropriate design (CCD, BBD, etc.) based on number of factors, resources, and optimization goals.

Experiment Execution: Conduct experiments according to the design matrix, randomizing run order to minimize systematic error.

Model Development and Fitting: Fit empirical models (typically second-order polynomials) to experimental data using regression analysis.

Model Adequacy Checking: Evaluate model validity through statistical measures (R², adjusted R², lack-of-fit tests, residual analysis).

Optimization and Validation: Identify optimal factor settings and confirm predictions through additional experimental runs.

Mathematical Modeling in RSM

The most common empirical model in RSM is the second-order polynomial equation [22]:

Y = β₀ + ∑βᵢXᵢ + ∑βᵢᵢXᵢ² + ∑βᵢⱼXᵢXⱼ + ε

Where:

- Y represents the predicted response

- β₀ is the constant term

- βᵢ are linear coefficients

- βᵢᵢ are quadratic coefficients

- βᵢⱼ are interaction coefficients

- Xᵢ and Xⱼ are coded factor levels

- ε represents random error

This model captures linear effects, curvature, and two-factor interactions, providing sufficient flexibility to approximate most biological response surfaces within limited experimental regions [22] [25]. Model parameters are typically estimated using ordinary least squares regression, with significance testing to eliminate unimportant terms [23].

Diagram 1: RSM Implementation Workflow for Drug Combination Studies

Experimental Protocols for Drug Combination Studies

Comprehensive Screening Protocol

For initial characterization of unknown drug interactions:

Plate Setup: Seed cells in 384-well plates at optimized density (typically 1,000-5,000 cells/well) and incubate for 24 hours.

Compound Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of individual compounds in DMSO followed by culture medium, maintaining final DMSO concentration ≤0.1%.

Combination Matrix Design: Implement 8×8 dose-response matrix covering EC₁₀-EC₉₀ ranges for each compound, including single-agent and combination treatments.

Dosing Protocol: Add compounds using liquid handlers, maintaining consistent timing across plates.

Incubation and Assay: Incubate for 72-96 hours, then assess viability using ATP-based (CellTiter-Glo) or resazurin reduction assays.

Data Collection: Measure luminescence/fluorescence, normalize to vehicle (100%) and no-cell (0%) controls.

Quality Control: Include reference compounds with known responses, assess Z'-factor >0.4 for assay quality.

RSM-Optimized Experimental Protocol

For response surface modeling with Central Composite Design:

Factor Coding: Code drug concentrations to -α, -1, 0, +1, +α levels based on preliminary EC₅₀ estimates.

Design Implementation: Execute CCD with 4-6 center points to estimate pure error.

Response Measurement: Quantify multiple relevant endpoints (viability, apoptosis, cell cycle) where feasible.

Replication: Perform technical triplicates with biological replicates (n≥3).

Model Fitting: Fit second-order polynomial models to response data using multiple regression.

Surface Analysis: Generate 3D response surfaces and 2D contour plots to visualize interaction landscapes.

Validation Protocol for Synergy Claims

To confirm putative synergistic regions identified through RSM:

Confirmation Experiments: Conduct targeted experiments at predicted optimal combination ratios with increased replication (n≥6).

Bliss Independence Calculation: Compare observed effects against expected Bliss independent effects [26].

Statistical Testing: Apply two-stage response surface models with formal hypothesis testing for synergism at specific dose combinations to control false positives [26].

Mechanistic Follow-up: Investigate pathway modulation through Western blotting, RNA sequencing, or functional assays.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Combination Effects

Table 2: Key Parameters in RSM Analysis of Drug Combinations

| Parameter | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Coefficient (β₁₂) | Coefficient for cross-term X₁X₂ in polynomial model | Magnitude and direction of drug interaction; Positive values suggest synergy, negative values antagonism | Statistically significant deviation from zero (p<0.05) |

| Loewe Additivity Deviation | ∫(Yobserved - YLoewe) over dose space | Integrated measure of synergy/antagonism across all concentration pairs | Confidence intervals excluding zero indicate significant interaction |

| Bliss Independence Deviation | Yobserved - YBliss at specific concentrations | Difference between observed and expected effect assuming independent action | Values >0 suggest synergy, values <0 suggest antagonism |

| Potency Shift | ΔEC₅₀ between single agent and combination | Change in effective concentration required for response | Significant reduction indicates favorable combination effect |

| Therapeutic Index Shift | Combination TI / Best single-agent TI | Improvement in safety window | Values >1 indicate therapeutic advantage |

Model Diagnostics and Validation

Robust RSM analysis requires rigorous model validation:

Coefficient Significance: Test regression coefficients using t-tests, retaining only statistically significant terms (p<0.05-0.10) unless required for hierarchy.

Lack-of-Fit Testing: Compare pure error (from replicate points) to model lack-of-fit using F-tests; non-significant lack-of-fit (p>0.05) indicates adequate model.

R² and Adjusted R²: Evaluate proportion of variance explained, with adjusted R² >0.70 typically indicating reasonable predictive ability.

Residual Analysis: Examine residuals for normality, independence, and constant variance using Shapiro-Wilk tests and residual plots.

Prediction R² (R²pred): Assess predictive power through cross-validation or holdout samples, with R²pred >0.60 indicating acceptable prediction.

Visualization and Interpretation

Effective communication of RSM results employs multiple visualization approaches:

3D Response Surfaces: Display response as a function of two drug concentrations, enabling identification of synergistic regions and optimal combination ratios.

Contour Plots: Provide 2D representations of response surfaces with isoboles indicating equal effect levels, facilitating direct comparison with traditional synergy methods.

Interaction Plots: Show how the effect of one drug changes across levels of another, highlighting significant interactions.

Optimization Overlays: Superimpose contour plots for multiple responses to identify regions satisfying all optimization criteria simultaneously.

Diagram 2: RSM Data Analysis and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Drug Combination Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Example | Function in Combination Studies | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Assays | CellTiter-Glo (ATP quantification), Resazurin reduction, MTT | Quantification of treatment effects on cell metabolism and proliferation | Linear range, sensitivity, compatibility with drug compounds |

| Apoptosis Assays | Annexin V/PI staining, Caspase-3/7 activation assays | Distinction of cytostatic vs. cytotoxic combination effects | Timing of assessment relative to treatment |

| High-Throughput Screening Plates | 384-well tissue culture treated plates, 1536-well for large screens | Enable efficient testing of multiple dose combinations | Surface treatment, edge effects, evaporation control |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Beckman Biomek, Tecan Freedom Evo, Hamilton Star | Precise compound transfer and serial dilution for combination matrices | Volume accuracy, carryover minimization, DMSO compatibility |

| Response Surface Analysis Software | R (drc, Response Surface packages), Prism, COMPUSYM | Statistical analysis of combination data and response surface modeling | Implementation of appropriate null models, visualization capabilities |

| Compound Libraries | FDA-approved oncology drugs, Targeted inhibitor collections | Source of combination candidates with diverse mechanisms | Solubility, stability in DMSO, concentration verification |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Three-Way Drug Combinations and Higher-Order Interactions

RSM methodologies extend beyond two-drug combinations to address the increasing interest in three-drug regimens, particularly in oncology and infectious disease. Specialized experimental designs such as Box-Behnken and mixture designs enable efficient exploration of these higher-dimensional spaces [22]. The BRAID method specifically demonstrates RSM extensions for analyzing three-way drug combinations, capturing complex interactions that cannot be identified through pairwise testing alone [21].

Integration with Machine Learning and Predictive Modeling

The rise of large-scale drug combination databases presents opportunities for integrating empirical RSM with computational approaches [21]. Machine learning models can leverage RSM-derived interaction parameters as training data to predict novel synergistic combinations, creating virtual screening tools that prioritize combinations for experimental validation [21]. This integration addresses the fundamental dimensionality challenge in combination therapy development, where exhaustively testing all possible combinations remains practically impossible.

Atypical Response Behaviors and Therapeutic Window Optimization

RSM provides flexible frameworks for analyzing non-standard response behaviors, including partial inhibition, bell-shaped curves, and hormetic effects that complicate traditional synergy analysis [21]. By modeling entire response surfaces rather than single effect levels, RSM enables simultaneous optimization of both efficacy and toxicity surfaces, formally defining combination therapeutic windows that balance maximum target effect with minimum adverse effects [21].

Response Surface Methodology represents a paradigm shift in quantitative analysis of drug combinations, moving beyond the limitations of traditional index-based methods to provide robust, unbiased characterization of drug interactions. By modeling complete response surfaces across concentration ranges, RSM captures the complexity of biological systems more effectively, reduces structured analytical bias, and provides deeper mechanistic insights. The methodological framework supports advanced applications including three-way combinations, therapeutic window optimization, and integration with machine learning approaches. As combination therapies continue growing in importance across therapeutic areas, RSM offers the statistical rigor and conceptual framework necessary to navigate the complex landscape of drug interactions efficiently and accurately.

In the development of new pharmaceutical agents, a critical challenge lies in ensuring that the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) can be effectively delivered to and absorbed by the body. The solid-form selection and the subsequent particle engineering of an API are pivotal steps that directly influence key properties such as solubility, dissolution rate, stability, and processability during manufacturing [6]. Traditionally, the characterization of these properties has relied heavily on experimental techniques, a process that can be both time-consuming and resource-intensive. This paradigm establishes a fundamental distinction between the physical surface, which is the actual, measurable interface of a solid particle, and the experimental surface, which is the model of the surface constructed from analytical data. Computational surface analysis tools like CSD-Particle are now emerging to bridge this gap, offering a digital framework to predict critical material properties from crystal structure alone, thereby refining the physical-experimental research loop [6] [27].

This whitepaper details how computational modeling, particularly through the CSD-Particle software suite, is used to predict particle shape and dissolution behavior. It provides an in-depth technical guide on the underlying principles, methodologies, and integration of computational predictions with experimental validation, framed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Principles: From Crystal Structure to Functional Properties

The connection between a molecule's crystal structure and its macroscopic behavior is governed by the principle that a crystal's external form and surface chemistry are direct manifestations of its internal packing. The crystalline surface landscape is not uniform; it is composed of distinct facets with unique chemical functionalities and topographies. It is the surface chemistry and topology of these facets that dictate how a particle interacts with its environment, most critically with dissolution media [6].