Optimizing Surface Measurement Accuracy: Best Practices in Sample Handling for Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing robust sample handling protocols for accurate surface measurements.

Optimizing Surface Measurement Accuracy: Best Practices in Sample Handling for Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing robust sample handling protocols for accurate surface measurements. Covering foundational principles, practical methodologies, advanced troubleshooting, and validation techniques, it addresses critical challenges from environmental control to data integrity. By integrating current best practices with emerging trends in automation and green chemistry, this resource aims to enhance reliability in pharmaceutical analysis, quality control, and research outcomes, ultimately supporting regulatory compliance and scientific excellence.

The Critical Link Between Sample Integrity and Surface Measurement Success

Defining Surface Measurement Objectives in Pharmaceutical Contexts

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Surface Roughness in Spectroscopic Cleaning Verification

Problem: Low or inconsistent recovery rates during surface sampling for cleaning verification, potentially due to variable surface roughness of manufacturing equipment.

Explanation: The surface finish of pharmaceutical manufacturing equipment (e.g., stainless steel vessels, millers, blenders) can significantly impact the accuracy of analytical measurements. Rough surfaces can trap residues, reduce analytical recovery, and lead to measurement variability during cleaning validation [1].

Solution:

- Identify and Categorize Surface Roughness: Before measurement, use the analytical technique (e.g., FTIR) to identify the surface type and roughness of the equipment piece [1].

- Employ Surface-Specific Calibration: Develop and use calibration models that are specific to different surface roughness categories. A one-size-fits-all model can lead to prediction errors as high as 28% [1].

- Validate Method Robustness: As per ICH guidelines, conduct robustness testing that accounts for variables such as surface roughness, the presence of excipients, measurement distance, and environmental temperature to ensure method reliability [1].

Guide 2: Optimizing Wipe Sampling for Hazardous Drug Residue Monitoring

Problem: Inefficient or complex wipe sampling processes for monitoring hazardous drug (HD) surface contamination per USP <800> guidelines.

Explanation: Traditional wipe sampling can be logistically challenging, requiring different swabs or solvents for various drug classes, leading to potential errors and training burdens [2].

Solution:

- Implement a Single-Swab, Broad-Spectrum Method: Utilize a single swab with a universal wetting solution (e.g., 50/50 methanol/water) compatible with a wide range of drug classes, including platinum compounds, to sample a standard 100 cm² area [2].

- Use a Comprehensive Kit: Employ a turnkey sampling kit that includes all necessary materials: swabs, wetting agent, sampling template, vials, chain-of-custody forms, and prepaid return shipping. This ensures methodological consistency and reduces handling errors [2].

- Focus on Trendable Data: Establish a baseline and conduct semiannual monitoring. Use the data to identify trends, locate contamination hotspots, and trigger root cause analysis and corrective actions, rather than focusing solely on the absence of universally defined safe limits [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is particle size analysis critical for surface measurement and sample handling in pharmaceuticals?

Particle size directly influences key properties like dissolution rate, bioavailability, content uniformity, and powder flowability [3]. For surface measurements, smaller particles have a larger surface area, which can increase dissolution speed but may also make residues more difficult to remove during cleaning processes. Controlling particle size is essential for ensuring consistent drug performance and manufacturing processability [3].

FAQ 2: What are the regulatory expectations for surface measurement and particle characterization?

Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require detailed particle characterization and cleaning validation when these factors impact drug quality, safety, or efficacy [3]. This is guided by ICH Q6A for specifications [3]. Analytical methods must be validated per ICH Q2(R1) to ensure accuracy, precision, and robustness [3]. For hazardous drugs, USP <800> mandates environmental monitoring, including surface sampling, to verify decontamination effectiveness, though it does not prescribe absolute residue thresholds [2].

FAQ 3: How does the choice of analytical technique affect surface measurement outcomes?

Different techniques are suited for different measurement objectives:

- Laser Diffraction: Best for rapid, high-throughput particle size distribution analysis of powders, granules, and suspensions [3].

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Effective for real-time, non-destructive identification and quantification of chemical residues on equipment surfaces during cleaning verification [1].

- Wipe Sampling with LC/MS: Ideal for trace-level detection and quantification of specific hazardous drug residues on surfaces to comply with safety guidelines like USP <800> [2]. The technique must be selected based on the specific residue, the required detection limit, and the surface properties.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Particle Size Analysis Techniques in Pharmaceuticals

| Technique | Principle | Applicable Size Range | Key Advantages | Common Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Diffraction [3] | Measures scattering angle of laser light by particles. | Submicron to millimeter | Rapid, high-throughput, suitable for wet or dry dispersion. | Tablet granules, inhalable powders, nanoparticle suspensions. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [3] | Measures Brownian motion to determine hydrodynamic size. | Nanometer range | Sensitive for nanoparticles in suspension. | Nanosuspensions, liposomes, colloidal drug delivery systems. |

| Microscopy [3] | Direct visualization and measurement of particles. | >1 µm (Optical); down to nm (SEM) | Provides direct data on particle shape and morphology. | Assessing particle shape, agglomerates, and distribution. |

| Sieving [3] | Physical separation via mesh screens. | Tens of µm to mm | Simple, cost-effective for coarse powders. | Granulated materials, raw excipient powders. |

Protocol: Robustness Testing for Spectroscopic Surface Measurement

This protocol outlines a methodology for assessing the robustness of an FTIR method for cleaning verification, as referenced in the troubleshooting guide [1].

Objective: To investigate the effect of surface roughness, excipients, measurement distance, and environmental temperature on the FTIR spectroscopic measurement of surface residues.

Materials:

- FTIR Spectrometer with specular reflectance capability

- Manufacturing equipment coupons with different surface finishes (e.g., polished, milled)

- Standard solutions of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and common excipients

- Environmental chamber (for temperature control)

Procedure:

- Surface Roughness Identification: Obtain FTIR spectra from clean equipment coupons with varying surface roughness. Use these spectra to create a library or algorithm for pre-measurement surface type identification.

- Calibration Model Development: Develop separate calibration models for each distinct category of surface roughness using the API standard solutions.

- Controlled Variation Testing:

- Excipients: Measure API recovery in the presence and absence of common formulation excipients.

- Distance: Vary the distance between the spectrometer probe and the test surface within a defined operational range.

- Temperature: Conduct measurements in an environmental chamber, varying the temperature to simulate manufacturing conditions.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the impact of each variable on the chemical prediction. The method is considered robust if prediction errors across all tested conditions remain within pre-defined acceptable limits (e.g., ±10-15%).

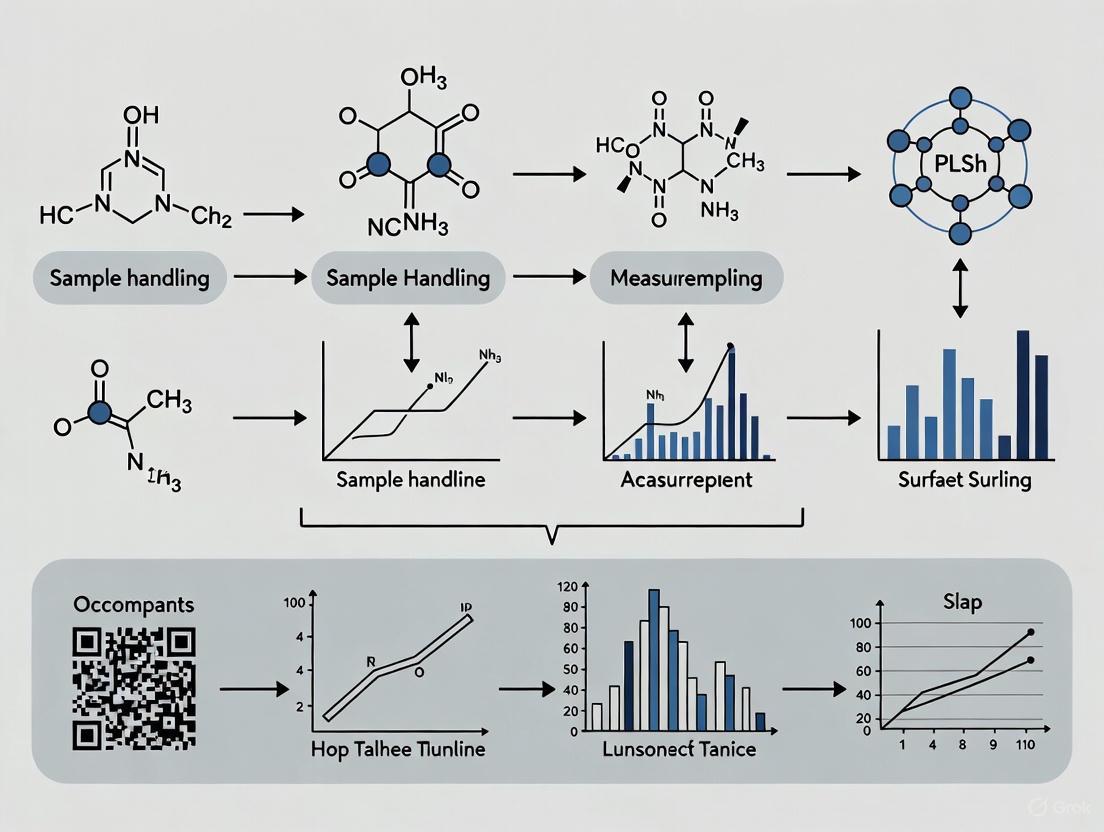

Workflow Visualization

Surface Measurement Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Surface Sampling and Analysis

| Item | Function | Example & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum Wipe Sampling Kit [2] | All-in-one kit for monitoring hazardous drug surface contamination. | ChemoSure kit: Includes swab, 50/50 methanol/water wetting solution, template, and vials for USP <800> compliance [2]. |

| Universal Wetting Solution [2] | Solvent used to moisten swabs for efficient residue recovery from surfaces. | 50/50 Methanol/Water: Provides broad compatibility across multiple drug classes (e.g., cytotoxics, platinum compounds) in a single swab [2]. |

| Surface Roughness Standards [1] | Certified materials with known surface finish used to calibrate and validate measurement methods. | Polished vs. Milled Steel Coupons: Used to develop surface-specific calibration models for spectroscopic techniques like FTIR [1]. |

| FTIR Spectrometer [1] | Analytical instrument for real-time, non-destructive identification and quantification of chemical residues. | Used for rapid cleaning verification on manufacturing equipment surfaces; requires robustness testing for variables like distance and temperature [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common environmental factors that can affect my surface measurements during sample handling? Environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations, humidity levels, and physical agitation or shock forces during transport are common sources of preanalytical error. Suboptimal storage and transport temperatures can alter specimen integrity, while agitation—common in pneumatic tube transport systems—can cause hemolysis or disrupt samples. Even within controlled indoor environments, microclimates and evaporation can impact measurement accuracy [4].

Q2: How do human factors contribute to measurement errors? Human error can arise from incorrect handling of precision instruments, misinterpretation of displayed data, or a lack of understanding of the instrument's functionality. This includes improper surface preparation of samples, which has been shown to cause measurement errors of approximately 20% in hardness tests due to high roughness or surface contamination [5] [6].

Q3: What is the difference between random and systematic errors?

- Systematic Errors: These are predictable, consistent inaccuracies that occur in the same direction and magnitude every time. Causes include calibration errors, incorrect instrument settings, or batch effects in laboratory analysis. They affect accuracy and can often be corrected through calibration or mathematical adjustments [7] [6].

- Random Errors: These are unpredictable fluctuations that vary from measurement to measurement. They stem from many uncontrollable factors, such as instrumental noise, minor environmental variations, or human perception differences. They affect precision and can be estimated statistically but not entirely eliminated [8] [6].

Q4: Can proper sample preparation really make a significant difference in measurement results? Yes, definitively. For instance, in one documented case, grinding balls measured with improperly prepared surfaces (showing high roughness and metal 'overburn') had an average hardness reading of 49.37 HRC. After correct surface preparation, the average result was 58.2 HRC—a discrepancy of about 20%. This highlights that proper preparation is not just a minor step but is critical for data validity [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Replicate Measurements

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Random Instrument Error | Calculate the standard deviation of multiple measurements. Check instrument specifications for stated repeatability (er) and linearity (el) [9]. | Increase the number of measurements and use the average. Ensure the instrument is placed on a stable, vibration-free surface. |

| Uncontrolled Environment | Monitor the laboratory temperature and humidity over time using a data logger. Check for drafts or direct sunlight on the instrument. | Perform measurements in a climate-controlled environment. Allow the instrument and samples to acclimate to the room temperature before use [6]. |

| Sample Preparation Variability | Review and standardize the sample preparation protocol. Inspect samples under magnification for consistent surface finish. | Implement a rigorous, documented sample preparation procedure. Train all staff on the specific protocol to ensure uniformity [5]. |

Problem: Measurements are Inaccurate (Deviate from Known Standard)

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic Instrument Error | Measure a known reference standard or calibration artifact. | Schedule regular calibration and maintenance of the measuring instrument as per the manufacturer's guidelines [6]. |

| Operator-Induced Error (Human) | Have a second trained operator perform the same measurement. Review the instrument's user manual for common handling pitfalls. | Provide comprehensive training for all users. Use jigs or fixtures to ensure consistent instrument placement and operation [6]. |

| Incorrect Data Interpretation | Check the formulas and calculations used to derive the final result from the raw measurement. | Validate data processing workflows. Use peer review for critical measurements. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Error Assessment

Protocol: Assessing the Impact of Agitation on Sample Integrity

Objective: To quantify the effect of agitation, similar to pneumatic tube system (PTS) transport, on a liquid sample.

Materials:

- Test tubes containing the sample liquid (e.g., whole blood, a standardized solution).

- A laboratory vortex mixer or a custom shaker platform.

- Centrifuge and microhematocrit tubes (if testing for hemolysis).

- Analytical equipment relevant to your sample (e.g., spectrophotometer).

Method: a. Divide the sample into two equal aliquots (Test and Control). b. Control Aliquot: Allow it to remain stationary at room temperature. c. Test Aliquot: Subject it to a defined agitation protocol on the vortex mixer (e.g., 10 minutes at a specific, documented speed). d. Analyze both aliquots using your analytical equipment. For hemolysis, measure free hemoglobin via spectrophotometry. For other samples, measure the analyte of interest.

Analysis: Compare the results from the Test and Control aliquots. A statistically significant difference indicates the sample is susceptible to agitation-induced error [4].

Protocol: Validating a Surface Measurement Process

Objective: To ensure that the entire process, from sample preparation to measurement, produces accurate and precise results.

Materials:

- Certified reference material (CRM) with a known, traceable value for the property being measured.

- All standard reagents and equipment for sample preparation.

Method: a. Prepare the CRM using your standard laboratory preparation protocol, ensuring it is identical to how unknown samples are treated. b. Perform the measurement on the prepared CRM a minimum of 10 times, ensuring the instrument is re-positioned between measurements where applicable.

Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the average of your measurements. The difference between this average and the CRM's certified value indicates your systematic error (accuracy).

- Precision: Calculate the standard deviation of your repeated measurements. This indicates your random error (precision) [8].

Visualizing Error Management

Error Management Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Reliable Surface Measurement Research

| Item | Function & Importance in Error Prevention |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a ground truth with a known, traceable value. Critical for calibrating instruments and validating the accuracy of your entire measurement process. |

| Standardized Cleaning Solvents | Ensures consistent and complete removal of contaminants from sample surfaces prior to measurement, preventing interference and false readings. |

| Non-Abrasive Wipes & Swabs | Allows for safe cleaning and handling of sensitive samples without scratching or altering the surface, which could introduce errors. |

| Data Loggers | Monitors and records environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) during sample storage, transport, and measurement to identify environmental error sources. |

| Calibrated Mass Standards | Used to verify the performance of balances and scales, a fundamental step in many sample preparation protocols. |

| Stable Control Samples | A homogeneous, stable material measured repeatedly over time to monitor the long-term precision and drift of the measurement system. |

The Impact of Sample Handling on Analytical Results and Data Integrity

In analytical science, the journey from sample collection to data reporting is fraught with potential pitfalls. Proper sample handling is not merely a preliminary step; it is a foundational component that directly determines the accuracy, reliability, and integrity of analytical results. This is particularly critical in surface measurements research, where minute contaminants or improper preparation can drastically alter topography readings and material property assessments. Recent research highlights that inconsistent measurement techniques can lead to variations in surface roughness parameters by a factor of up to 1,000,000, underscoring the profound impact of methodological approaches on data quality [10] [11].

Within regulated industries such as pharmaceuticals, the consequences of poor sample handling extend beyond scientific inaccuracy to regulatory non-compliance. Regulatory agencies including the FDA and MHRA have increasingly focused on data integrity during audits, implementing what some describe as a "guilty until proven innocent" approach where laboratories must prove their analytical results are not fraudulent [12]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate these challenges, ensuring their sample handling practices support both scientific excellence and regulatory compliance.

Understanding Data Integrity in the Analytical Laboratory

The ALCOA+ Framework

Data integrity in analytical laboratories is governed by the ALCOA+ principles, which provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring data reliability throughout its lifecycle [12]. These principles have been adopted by regulatory agencies worldwide as standard expectations for data quality:

- Attributable: Data must clearly indicate who created it, when it was created, and who made any subsequent modifications. Sharing passwords among analysts violates this principle, as it becomes impossible to attribute actions to specific individuals [12].

- Legible: Data must be permanently recorded in a durable medium and be readable throughout the records retention period. This includes ensuring that electronic data remains accessible as technology evolves [12].

- Contemporaneous: Documentation must occur at the time activities are performed. Recording data later from memory or rough notes compromises accuracy and reliability [12].

- Original: The source data or a certified true copy must be preserved. Defining printed copies as "raw data" rather than the electronic source files does not satisfy regulatory requirements [12].

- Accurate: Data must be free from errors, with any edits documented through audit trails. Uncontrolled manual calculations present significant accuracy risks [12].

The extended "+" principles include:

- Complete: All data including repeat or reanalysis performed on the sample must be present [12].

- Consistent: Date and time stamps should follow in sequence without unexplained inconsistencies [12].

- Enduring: Records must be maintained on controlled worksheets, laboratory notebooks, or electronic media throughout the required retention period [12].

- Available: Data must be accessible for review and audit for the lifetime of the record [12].

Data Integrity Model for Analytical Laboratories

A comprehensive data integrity program encompasses multiple layers of controls and practices as illustrated below:

Data Integrity Model for Analytical Laboratories

This model demonstrates that effective data integrity begins with a foundation of proper corporate culture and extends through appropriate instrumentation, validated procedures, and finally to the analysis itself, with quality oversight permeating all levels [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Sample Handling Issues and Solutions

Surface Measurement Challenges

Surface topography measurements present unique sample handling challenges that can significantly impact results:

Sample Handling Impact on Surface Measurements

The recent Surface-Topography Challenge, which involved 150 researchers from 20 countries submitting 2,088 individual measurements of standardized surfaces, revealed dramatic variations in results based on measurement techniques [10] [11]. The key finding was that measurements of the same surface using different techniques varied by a factor of 1,000,000 in root mean square (RMS) height values, highlighting the critical importance of standardized sample handling and measurement protocols [10].

Troubleshooting Solutions:

- Use multiple measurement scales and techniques (even just two or three) to obtain more accurate surface topography results [10].

- Establish standardized sample preparation protocols that include thorough cleaning to remove contaminants that could interfere with surface measurements.

- Implement regular calibration using reference samples with known topography to validate measurement systems.

Liquid Chromatography Sample Handling Issues

Liquid chromatography (LC) analyses are particularly susceptible to sample handling problems that manifest in various chromatographic anomalies:

Table 1: Common LC Sample Handling Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing or Fronting | Column overload, sample solvent mismatch, secondary interactions with stationary phase [14] | Reduce injection volume or dilute sample; ensure sample solvent compatibility with mobile phase; use columns with less active sites [14] |

| Ghost Peaks | Carryover from previous injections, contaminants in mobile phase or vials, column bleed [14] | Run blank injections; clean autosampler and injection needle; use fresh mobile phase; replace column if suspect degradation [14] |

| Retention Time Shifts | Mobile phase composition changes, column temperature fluctuations, column aging [14] | Verify mobile phase preparation; check column thermostat stability; monitor column performance over time [14] |

| Pressure Spikes | Blockage in inlet frit or guard column, particulate buildup, column collapse [14] | Disconnect column to identify location of blockage; reverse-flush column if permitted; replace guard column [14] |

Mass Spectrometry Sample Preparation Challenges

Mass spectrometry represents one of the most sensitive techniques to sample handling errors, where minute contaminants can significantly impact results:

Table 2: Mass Spectrometry Sample Preparation Challenges by Sample Type

| Sample Type | Common Pitfalls | Prevention Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins & Peptides | Incomplete digestion, keratin contamination from skin/hair [15] | Optimize digestion conditions; use clean, keratin-free labware; wear proper protective equipment [15] |

| Tissues & Cells | Inefficient homogenization, degradation of molecules [15] | Use appropriate homogenization techniques; include enzyme inhibitors; perform procedures at low temperatures [15] |

| Environmental Samples | Loss of volatile compounds, contamination from collection devices [15] | Use mild concentration techniques; employ inert, pre-cleaned collection equipment [15] |

| Pharmaceutical Samples | Incomplete extraction from matrix, inadequate enrichment [15] | Optimize solvent extraction; employ solid-phase extraction for concentration [15] |

Critical Mass Spectrometry Considerations:

- Solvent Compatibility: Use MS-compatible buffers such as ammonium acetate, ammonium formate, and ammonium bicarbonate at concentrations of 10 mM or less. Avoid salts, phosphate buffers, HEPES, detergents, urea, glycerol, and polymers which interfere with ionization [16].

- Sample Concentration: For electrospray ionization (ESI), solutions should typically be 50-100 μM in a suitable solvent with a recommended volume of ~1.5 mL [16].

- Special Handling: Light-sensitive samples should be wrapped in aluminum foil; air-sensitive samples require special arrangements with MS facility staff; low-temperature storage may be necessary for unstable compounds [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the minimum sample amount required for mass spectrometry analysis? For most mass spectrometry applications, 1 mL of a 10 ppm solution or 1 mg of solid material is generally sufficient. If sample quantity is limited, inform the facility staff as analyses may still be possible with smaller amounts [16].

Q2: How can we differentiate between column, injector, or detector problems in LC analysis? A systematic approach is needed: column issues typically affect all peaks, injector problems often manifest in early chromatogram distortions, while detector issues usually cause baseline noise or sensitivity changes. To isolate the source, replace the column with a known good one, run system suitability tests, and check injection reproducibility [14].

Q3: What are the regulatory consequences of poor data integrity practices? Regulatory agencies can issue warning letters, impose restrictions, or reject submissions based on data integrity violations. Common issues identified in audits include shared passwords, inadequate user privileges, disabled audit trails, and incomplete data [12].

Q4: How long should analytical data be retained? Data retention policies vary by organization and regulation, but as a general practice, data should be maintained for the lifetime of the product plus applicable statutory requirements. Mass spectrometry facilities typically store data for a minimum of six months, but researchers should obtain copies within this timeframe [16].

Q5: What acknowledgments are required when publishing data generated by core facilities? Publications containing data from core facilities should include acknowledgment of the facility. Typical wording is: "Mass spectrometry [or other technique] reported in this publication was supported by the [Facility Name] of [Institution]." In cases of significant intellectual contribution from facility staff, co-authorship may be appropriate [16].

Q6: What are the emerging technologies improving surface measurement accuracy? New approaches like fringe photometric stereo can reduce the number of required light patterns by more than two-thirds compared to traditional methods, significantly speeding up scanning while improving accuracy to micrometer levels. This is particularly valuable for industrial inspection and medical applications [17].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Sample Preparation and Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MS-Compatible Buffers (Ammonium acetate, ammonium formate) | Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry | Use at concentrations ≤10 mM; avoid non-volatile buffers [16] |

| Acidic Additives (Formic acid, acetic acid, TFA) | Enhance ionization in positive ion mode MS | TFA can cause ion suppression; formic acid generally preferred for ESI [16] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) | Sample clean-up and concentration | Effectively removes salts and detergents that interfere with ionization [16] [15] |

| MALDI Matrix Compounds | Enable soft ionization of large biomolecules | Must co-crystallize with sample; choice depends on analyte type [15] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Modify compounds for GC-MS analysis | Enhance volatility and stability for gas chromatography applications [15] |

| Enzymes for Digestion (Trypsin) | Protein cleavage for proteomics | Requires optimized conditions (temperature, pH, enzyme-to-substrate ratio) [15] |

Best Practices for Sample Handling Workflows

Implementing robust sample handling workflows is essential for maintaining data integrity throughout the analytical process:

Sample Handling and Data Integrity Workflow

Key workflow considerations:

- Sample Collection: Use appropriate containers and preservation methods immediately upon collection

- Documentation: Apply ALCOA+ principles from the initial handling stage

- Sample Preparation: Follow technique-specific protocols for extraction, purification, and concentration

- Analysis: Verify system suitability before running samples

- Data Processing: Maintain audit trails of any reprocessing or reintegration

- Storage: Ensure data is securely stored and readily available for the required retention period

The impact of sample handling on analytical results and data integrity cannot be overstated. As the Surface-Topography Challenge dramatically demonstrated, methodological variations can lead to differences of six orders of magnitude in measured parameters [10]. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and best practices outlined in this technical support resource, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their analytical results. Maintaining rigorous sample handling protocols supported by a culture of data integrity is not merely a regulatory requirement—it is the foundation of scientific excellence in surface measurements research and all analytical sciences.

The future of analytical measurements continues to advance with new technologies like fringe photometric stereo offering faster, more accurate surface measurements [17]. However, these technological improvements will only realize their full potential when coupled with impeccable sample handling practices and unwavering commitment to data integrity principles throughout the analytical workflow.

Key Regulatory Updates: FDA, EMA, and USP

Staying current with evolving guidelines from major regulatory bodies is fundamental for robust sample handling and accurate analytical measurements. The table below summarizes recent and upcoming changes.

| Agency/Standard | Guideline/Chapter | Key Focus Area | Status & Timeline | Implications for Sample Handling & Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. FDA | Considerations for Complying with 21 CFR 211.110 (Draft) [18] [19] |

In-process controls, sampling, testing, and advanced manufacturing [18]. | Draft guidance; comments accepted until April 7, 2025 [18]. | Promotes risk-based strategies; allows for real-time, non-invasive sampling (e.g., PAT) in continuous manufacturing [18] [19]. |

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) | Revised Variations Regulation & Guidelines [20] | Post-approval changes to marketing authorizations [20]. | New guidelines apply from January 15, 2026 [20]. | Changes to analytical methods or sample specifications must follow new categorization and reporting procedures [20]. |

| U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) | General Chapter <1225> "Validation of Compendial Procedures" (Proposed Revision) [21] | Alignment with ICH Q2(R2), integration with Analytical Procedure Life Cycle (<1220>) [21]. | Proposed revision; comments accepted until January 31, 2026 [21]. | Emphasizes "Fitness for Purpose" and "Reportable Result," linking validation directly to confidence in decision-making for sample results [21]. |

| U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) | General Chapter <1058> "Analytical Instrument Qualification" (Proposed Update) [22] | Modernizes qualification to a risk-based life-cycle approach [22]. | Proposed revision; comments accepted until May 31, 2025 [22]. | Ensures instrument "fitness for intended use" through continuous life-cycle management, crucial for reliable sample data [22]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

In-Process Sample Testing and Control

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent in-process sample results during continuous manufacturing. | Non-representative sampling or inability to physically isolate stable samples from a continuous stream [18]. | Implement and validate real-time Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for at-line, in-line, or on-line measurements instead of physical sample removal [18]. | FDA 21 CFR 211.110 [18] |

| A process model predicts out-of-spec results, but physical samples are within limits. | Underlying assumptions of the process model may be invalid due to unplanned disturbances [18]. | Do not rely solely on the process model. Pair the model with direct in-process material testing or examination. The model should be continuously verified against physical samples [18]. | FDA 21 CFR 211.110 [18] |

| Uncertainty in determining when to sample during "significant phases" of production. | Lack of a scientifically justified rationale for sampling points [18]. | Define and justify sampling locations and frequency based on process knowledge and risk assessment, and document the rationale in the control strategy [18]. | FDA 21 CFR 211.110 [18] |

Analytical Procedure and Instrument Qualification

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|

| An analytical procedure is validated but produces variable results when testing actual samples. | Traditional validation may not fully account for the complexity of the sample matrix or procedure lifecycle drift [21]. | Adopt an Analytical Procedure Life Cycle (APLC) approach per USP <1220>. Enhance validation to assess "Fitness for Purpose" and control uncertainty of the "Reportable Result" [21]. | USP <1225> (Proposed) [21] |

| An instrument passes qualification but generates unreliable sample data. | Qualification was treated as a one-time event rather than a continuous process; performance may have drifted [22]. | Implement a life-cycle approach to Analytical Instrument and System Qualification (AISQ) per the proposed USP <1058>, integrating ongoing Performance Qualification (PQ) and change control [22]. | USP <1058> (Proposed) [22] |

| A compendial (USP/EP) method does not perform as expected with a specific sample matrix. | The sample matrix may contain interfering components not present in the standard used to develop the compendial method [23]. | Verify the compendial method following USP <1226> to demonstrate its suitability for use with your specific sample under actual conditions of use [23]. | USP / EP General Chapters [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: According to the new FDA draft guidance, can I use a process model alone for in-process control without physical sampling?

A: No. The FDA explicitly advises against using a process model alone. The draft guidance states that process models should be paired with in-process material testing or process monitoring to ensure compliance. The FDA's current position is that it has not identified any process model that can reliably demonstrate its underlying assumptions remain valid throughout the entire production process without additional verification [18].

Q2: We are planning to make a change to an approved sample preparation method in the EU. What is the most critical date to know?

A: The key date is January 15, 2026. For any Type-IA, Type-IB, or Type-II variation you wish to submit on or after this date, you must follow the new Variations Guidelines and use the updated electronic application form [20]. For variations submitted before this date, the current guidelines apply.

Q3: What is the core conceptual change in the proposed USP <1225> revision for validating an analytical procedure?

A: The revision shifts the focus from simply checking a list of validation parameters to demonstrating overall "Fitness for Purpose." The goal is to ensure the procedure is suitable for its intended use in making regulatory and batch release decisions. It emphasizes the "Reportable Result" as the critical output and introduces statistical intervals to evaluate precision and accuracy in the context of decision risk [21].

Q4: How does the proposed update to USP <1058> change how we manage our laboratory instruments?

A: The update changes instrument qualification from a static, one-time event (DQ, IQ, OQ, PQ) to a dynamic, risk-based life-cycle approach. This means qualification is a continuous process that spans from instrument selection and installation to its eventual retirement. It requires ongoing performance verification and integration with your change control system to ensure the instrument remains "fit for intended use" throughout its operational life [22].

Experimental Protocols for Key Scenarios

Protocol: Verification of a Compendial Sample Preparation Method

This protocol outlines the steps to verify a USP or EP sample preparation and analysis method when implemented in your laboratory.

1. Principle: To demonstrate that a compendial method, as written, is suitable for testing a specific substance or product under actual conditions of use in your laboratory, using your analysts and equipment [23].

2. Scope: Applicable to all compendial methods for sample preparation and analysis that are used as-is, without modification.

3. Responsibilities: Analytical Chemists, Quality Control (QC) Managers.

4. Materials and Equipment:

- Reference Standard

- Samples (e.g., drug substance/product)

- Reagents and solvents as specified in the monograph

- Required instrumentation (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis) qualified per USP <1058>

- Data acquisition system

5. Procedure: 1. Document Review: Thoroughly review the compendial monograph and any related general chapters to understand all requirements. 2. System Suitability Test (SST): Prepare the system suitability standard and reference standard as prescribed. Execute the method and ensure all SST criteria (e.g., precision, resolution, tailing factor) are met before proceeding. 3. Sample Analysis: Prepare and analyze the test samples as per the monograph. This typically includes: * Analysis of the sample for identity, assay, and impurities. * Demonstrating specificity against known potential interferents. 4. Precision: Perform the analysis on a homogeneous sample at least six times (e.g., six independent sample preparations), or as specified by the monograph, to verify repeatability. 5. Accuracy (as required): For assay, perform a spike recovery experiment using a known standard. For impurities, confirm the detection limit.

6. Acceptance Criteria: The method verification is successful if all system suitability tests pass and the results for the samples (e.g., assay potency, impurity profile) are within the predefined expected ranges and monograph specifications.

7. Documentation: Generate a method verification report that includes raw data, chromatograms, calculated results, and a statement of suitability.

Protocol: Implementing a Risk-Based Life-Cycle Approach to Instrument Qualification

This protocol describes the process for qualifying an analytical instrument according to the principles of the proposed USP <1058> update.

1. Principle: To ensure an analytical instrument or system is and remains fit for its intended use through a life-cycle approach encompassing specification, qualification, ongoing performance verification, and retirement [22].

2. Scope: Applies to new and existing critical analytical instruments (e.g., HPLC, GC, spectrophotometers).

3. Responsibilities: QC/QA, Laboratory Managers, Instrument Specialists.

4. Materials and Equipment: Instrument-specific qualification kits and standards (e.g., wavelength, flow rate, absorbance standards).

5. Procedure: 1. Design Qualification (DQ): Document the intended purpose of the instrument and the user requirements specifications (URS). Select an instrument that meets these requirements. 2. Initial Qualification: * Installation Qualification (IQ): Document that the instrument is received as specified, installed correctly, and that the environment is suitable. * Operational Qualification (OQ): Verify that the instrument operates according to the supplier's specifications across its intended operating ranges. * Performance Qualification (PQ): Demonstrate that the instrument performs consistently and as intended for the specific analytical methods and samples it will be used with. This involves testing with actual samples and reference materials. 3. Ongoing Performance Verification: Establish a periodic schedule for re-qualification (PQ) based on risk, instrument usage, and performance history. This is a continuous process, not a one-time event. 4. Change Control: Any change to the instrument, software, or critical operating parameters must be evaluated through a formal change control process. Re-qualification must be performed as necessary based on the risk of the change. 5. Retirement: Formally document when the instrument is taken out of service.

6. Acceptance Criteria: All tests and checks must meet predefined acceptance criteria defined in the URS, manufacturer's specifications, or method requirements.

7. Documentation: Maintain a complete life-cycle portfolio for each instrument, including the URS, all qualification protocols and reports, change control records, and performance verification data.

Visualization of Key Processes

Analytical Procedure Lifecycle

This diagram illustrates the life-cycle approach for analytical procedures, connecting procedure design, validation, and ongoing verification to ensure continued fitness for purpose.

Sample Preparation Workflow

This workflow outlines the critical steps in preparing samples for analysis, highlighting how each stage impacts the final reportable result.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and tools critical for ensuring regulatory compliance and data integrity in sample-based research.

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Regulatory Context / Best Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Enables real-time, in-line, or at-line monitoring of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) during manufacturing. | Supported by FDA draft guidance as an alternative to physical sample removal in continuous manufacturing [18]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides a benchmark for calibrating instruments and validating/verifying analytical methods to ensure accuracy. | Required by USP/EP monographs for system suitability testing and quantitation [23]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Used in bioanalytical methods to correct for analyte loss during sample preparation and matrix effects during analysis. | Critical for achieving the accuracy and precision required for method validation per ICH/USP guidelines. |

| Qualification Kits & Calibration Standards | Used to perform Installation, Operational, and Performance Qualification of analytical instruments. | Core component of the life-cycle approach to Analytical Instrument Qualification per proposed USP <1058> [22]. |

| Data Integrity Management Software | Securely captures, processes, and stores electronic data with audit trails to ensure data is attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate (ALCOA). | Expected by FDA and EMA in all regulatory submissions; critical for compliance during inspections [23]. |

Establishing a Contamination Control Strategy for Sampling Areas

FAQs: Contamination Control Fundamentals

1. What is the primary purpose of a contamination control strategy in sampling areas? The primary purpose is to prevent product contamination and cross-contamination, ensuring the integrity of samples and the accuracy of analytical results. Effective control strategies are regulatory requirements that validate cleaning procedures, confirm that residues have been reduced to acceptable levels, and are a fundamental part of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) [24].

2. How do I determine the most appropriate surface sampling method? The choice depends on the surface type, the target analyte, and the purpose of sampling. No single method is perfect for all situations [25].

- Swab Sampling: Ideal for hard-to-reach spots and irregular surfaces. It is the method of choice for detecting antineoplastic drug contamination on specific, potentially contaminated surfaces [24] [25].

- Rinse Sampling: Effective for sampling large surface areas and the inner surfaces of equipment like tanks and pipes. It allows the sampling of areas that are otherwise inaccessible [24].

- Placebo Sampling: Used in pharmaceutical manufacturing, this involves running a non-active batch to check for carry-over of residues from previous product batches [24].

3. What are the critical factors for reliable sample preparation and analysis? Reliable sample preparation is the cornerstone of accurate analysis. Key factors include [26]:

- Collection: Samples must be gathered under controlled conditions to prevent degradation or contamination from the start.

- Storage: Temperature, time, and container materials must be managed to preserve analyte integrity until analysis.

- Processing: Techniques like filtration, centrifugation, and dilution are used to isolate analytes and remove interfering substances, making the sample ready for the assay.

4. Why is environmental monitoring (EM) crucial, and what should I test for? Environmental monitoring proactively identifies and controls contamination sources within the facility environment. A well-designed program tests for [27]:

- Pathogens: Such as Listeria spp., Salmonella, and E. coli in high-risk areas.

- Indicator Organisms: Like Coliforms or Enterobacteriaceae, which signal the overall hygienic state of the facility.

- Spoilage Organisms: Including yeasts and molds, to prevent product spoilage.

- Allergens: To verify that cleaning procedures effectively remove allergen residues and prevent cross-contact.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or High Background Contamination in Sampling Areas

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Ineffective Cleaning Procedures | Review and validate the Cleaning Validation Protocol. Check recovery studies for swab methods. | Revise Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). Optimize detergent selection and cleaning techniques (e.g., manual vs. CIP) [24]. |

| Poor Sampling Technique | Audit staff during sampling. Check for consistent use of neutralizing buffers in swab media. | Retrain personnel on aseptic technique and standardize the swab pattern, pressure, and area [25] [27]. |

| Inadequate Facility Zoning | Review the facility's hygienic zoning map and traffic flow patterns. | Re-establish four clear hygienic zones (Zone 1: Direct product contact, to Zone 4: General facility). Strengthen physical controls and GMPs for higher-risk zones [27]. |

Issue 2: Failure in Analytical Sample Preparation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Degradation During Storage | Review storage logs for temperature excursions. Check container material compatibility. | Implement strict temperature controls (e.g., -80°C, -20°C, 4°C). Use inert storage containers and minimize storage time [26]. |

| Improper Sample Processing | Check calibration records for centrifuges and pipettes. Review processing logs for deviations. | Standardize processing steps (e.g., centrifugation speed/duration, filtration pore size). Use high-quality reagents to prevent introduction of contaminants [26]. |

| Interfering Substances | Analyze the sample matrix complexity. Test for carry-over from previous samples in the equipment. | Incorporate specific processing steps to remove interferents. Use controls to identify background signal and perform adequate equipment cleaning between samples [26]. |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Sampling

Detailed Protocol: Surface Wipe Sampling for Hazardous Drug Residues

This protocol is adapted from methods used to monitor antineoplastic drugs in healthcare settings and is applicable for validating cleaning efficacy in pharmaceutical sampling areas [25].

1. Pre-Sampling Planning:

- Define Purpose: Clearly state the goal (e.g., routine monitoring, spill assessment, cleaning validation).

- Select Surrogates: Choose representative drugs based on toxicity, usage frequency, and detectability.

- Laboratory Coordination: Partner with an accredited lab (e.g., AIHA-LAP accredited) that has validated methods for your target analytes.

2. Materials Required:

- Swabs: Pre-moistened with a solution containing a neutralizing agent (e.g., sodium thiosulfate to neutralize disinfectants) [27].

- Templates: Use sterile, disposable templates to define a standardized sampling area (e.g., 10 cm x 10 cm).

- Sample Containers: Use sterile, leak-proof containers for swab transport.

- Cooler & Cold Packs: For transport at controlled temperatures.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, lab coat, and safety glasses.

3. Sampling Execution:

- Don PPE.

- Mark the Area: Place the template on the surface to be sampled.

- Swab Technique: Systematically wipe the area inside the template vertically and horizontally, applying consistent pressure. Roll the swab to use all sides.

- Package: Place the swab in the sample container, seal, and label immediately.

- Transport: Place samples in a cooler with cold packs and ship to the lab promptly.

4. Sampling Strategy and Frequency:

- Establish a risk-based schedule. Sample all hygienic zones, with higher frequency in high-risk areas (Zone 1). Incorporate both random and scheduled sampling [27].

The workflow for this surface sampling protocol is as follows:

Table: Establishing a Risk-Based Sampling Schedule

| Hygienic Zone | Description | Example Areas | Recommended Frequency [27] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | Direct product contact surfaces | Sampling tools, vessel interiors, filler needles | Every production run or daily |

| Zone 2 | Non-product contact surfaces adjacent to Zone 1 | Equipment frames, control panels, floor around equipment | Weekly |

| Zone 3 | Non-product contact surfaces farther from the process | Walls, floors, pallets, storage racks | Monthly |

| Zone 4 | Areas remote from the process | Locker rooms, cafeterias, warehouses | Quarterly or as part of an investigation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials for Contamination Control and Sampling

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Neutralizing Buffers | Inactivates disinfectants (e.g., quaternary ammonium compounds, chlorine) in swab media to prevent false negatives in microbiological testing [27]. | Must be matched to the disinfectants used in the facility's sanitation program. |

| ATP Detection Reagents | Provides a rapid (seconds) measure of general sanitation by detecting residual organic matter (Adenosine Triphosphate) on surfaces [27]. | Used for pre-operational checks; does not differentiate between microbial and non-microbial residues. |

| Selective Culture Media | Allows for the growth and identification of specific pathogens (e.g., Listeria, Salmonella) or indicator organisms (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae) [27]. | Choice of media depends on target organism; requires incubation time. |

| ELISA Kits | Detects specific allergen proteins (e.g., peanut, milk) on surfaces to validate cleaning efficacy and prevent cross-contact [27]. | High sensitivity and specificity; ideal for routine allergen verification. |

| Adsorbate Gases (N₂, Kr) | Used in Specific Surface Area analysis of materials. The sample must be properly "outgassed" to clear the surface of contaminants for an accurate measurement [28]. | The outgassing process (vacuum/heat) must not alter the material's structure. |

The logical relationship between the core components of a comprehensive contamination control strategy is illustrated below:

Practical Protocols: Implementing Robust Surface Sampling and Preparation Techniques

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary difference between a contact plate and a swab, and when should I use each?

Contact plates (including RODAC plates) and swabs are used for different surface types and scenarios. Contact plates are ideal for flat, smooth surfaces and provide a standardized area for sampling (typically 24-30 cm²) [29] [30]. They are pressed or rolled onto a surface to directly transfer microorganisms to the culture medium. Swabs, on the other hand, are better suited for irregular, curved, or difficult-to-reach surfaces, such as the nooks of machinery or wire racking [29] [31]. The choice depends on surface geometry and accessibility.

2. What is the proper technique for using a RODAC plate to ensure accurate results?

The technique significantly impacts recovery efficiency. For the highest microbial recovery, the recommended method is to roll the plate over the surface in a single, firm motion for approximately one second [30]. Avoid lateral movement during application, as this can spread contaminants and make enumeration difficult [32]. Ensure the entire convex agar surface makes contact with the test surface.

3. My cleaning validation swabs are consistently failing. What are the most common pitfalls?

Common pitfalls leading to swab failure include:

- Inadequate Sampling Technique: Applying insufficient pressure, using improper swab-to-surface contact, or sampling an inadequate area [33].

- Improper Swab Material: Using cotton swabs is no longer considered "state of the art" [34]. Modern swabs with specialized materials offer better recovery.

- Inefficient Extraction: Failing to properly transfer residues from the swab head into the extraction solution can lead to false negatives [34] [33].

- Sampling Dry Surfaces: Surfaces must be cool and dry before sampling; swabbing on surfaces still wet with sanitizer can interfere with test results [31].

4. Is environmental surface sampling always required, or are there specific indications?

Routine, undirected environmental sampling is generally not recommended [35]. Targeted sampling is indicated for four main situations:

- Investigating outbreaks of disease where environmental reservoirs are implicated.

- Research purposes with well-designed and controlled methods.

- Monitoring a potentially hazardous environmental condition.

- Quality assurance to evaluate a change in infection-control practice or equipment performance [35].

5. What are the critical storage and handling requirements for contact plates?

Contact plates must be refrigerated for storage at 2-8°C (40°F) and should not be frozen [32]. Exposure to light should be minimized. Prior to use, plates should be warmed to room temperature in their protective sleeves for about 15-20 minutes to prevent condensation [32]. Always use plates before their expiration date.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Microbial Recovery from Surfaces with Contact Plates

| Potential Cause | Explanation & Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect Application Technique | Explanation: Simply pressing the plate without rolling, or using an insufficient contact time, can drastically reduce recovery. One study found a press-only method had only 16% recovery efficiency vs. 53% for a 1-second roll [30].Solution: Implement a standardized protocol of rolling the plate in a single, firm motion for 1 second. |

| Improper Plate Preparation | Explanation: Using plates cold from the refrigerator can cause condensation, which may spread contamination or inhibit microbial growth [29].Solution: Always warm plates to room temperature in their sealed sleeves before use [32]. Store plates agar-up (lid-down) to minimize condensation [32]. |

| Expired or Compromised Growth Media | Explanation: The effectiveness of the culture media, including added neutralizers, degrades over time.Solution: Do not use expired plates. Ensure the media contains neutralizing agents (e.g., lecithin and polysorbate 80) to counteract disinfectant residues on sampled surfaces [29]. |

Issue 2: Inconsistent or Inaccurate Swab Results

| Potential Cause | Explanation & Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Swab Material | Explanation: Cotton swabs can release particulates, disintegrate, and fail to release residues into the extraction solution [34].Solution: Use modern swabs with specialized materials designed for high recovery. Select the swab material based on the target residue and the surface being sampled [33]. |

| Incorrect Swabbing Motion | Explanation: Gently swiping a surface is often insufficient. Vigorous, thorough scrubbing is needed to disrupt biofilms and pick up contaminants [31].Solution: Use a firm, overlapping pattern (e.g., a check pattern) and scrub vigorously, utilizing both sides of the sponge or swab head [34] [31]. |

| Poor Residue Extraction | Explanation: The transfer of residue from the swab to the liquid medium for analysis is a critical, often inefficient, step [34].Solution: Optimize the extraction solution for the residue type. Use mechanical aids like a vibratory shaker or ultrasonic bath to enhance extraction [34]. |

The table below consolidates critical quantitative data for planning and executing surface sampling.

| Parameter | Contact (RODAC) Plates | Swab Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Sampling Area | 24 - 30 cm² [29] [30] | Not standardized; a defined area (e.g., 5x5 in or 10x10 cm) is typically marked and swabbed. |

| Recovery Efficiency | Varies with technique: 16% (press), 53% (1-sec roll), 48% (5-sec roll) on hard surfaces with naturally occurring MCPs [30]. | Highly variable; depends on swab material, technique, residue type, and extraction efficiency. Must be validated for the specific method. |

| Incubation Parameters | 30-35°C for 48-72 hours [29] or 3-5 days [32]. Invert plates during incubation to prevent condensation [29]. | Determined by the target microorganism; similar temperature ranges are used after the swab is processed in a recovery medium. |

| Sample Transport Temp | Refrigerated conditions are standard for storage; shipped cool (e.g., with freezer packs) to the lab the same day as sampling [32]. | Must be received by the lab between 0 and 8°C to prevent microbial die-off or overgrowth [31]. |

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Surface Sampling Method Efficiencies

This protocol is adapted from a peer-reviewed study to determine the recovery efficiency of different manual contact plate sampling methods using naturally occurring microbe-carrying particles (MCPs) [30].

1. Objective To evaluate and compare the recovery efficiency of three different manual contact plate sampling procedures.

2. Materials

- Growth Media: Irradiated 55 mm diameter Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA) contact plates with lecithin and polysorbate 80 [30].

- Surfaces: A minimum of 20 different surface locations with sufficient microbial load (e.g., laboratory benches, floors in amenities areas). Surfaces should be hard, flat, and non-porous (e.g., vinyl, synthetic resin) [30].

- Incubator: Validated for 30-35°C.

- Labels and Diagram.

3. Methodology

- Sampling Plan: Identify and document 20 surface locations. At each location, mark three adjacent, non-overlapping test positions.

- Sampling Techniques: All sampling should be performed by the same trained individual to minimize variability.

- Position 1 - Method 1 (Roll, 1 second): Roll the contact plate over the surface in a single motion with firm force, lasting approximately 1 second. Immediately take a second sample (Sample B) from the exact same spot [30].

- Position 2 - Method 2 (Roll, 5 seconds): At an adjacent, unsampled spot, repeat the rolling motion with firm force, this time for 5 seconds. Take a second sample from this same spot [30].

- Position 3 - Method 3 (Press, no roll): At the third adjacent spot, press the plate onto the surface with firm force and no rolling motion for 1 second. Take a second sample from this spot [30].

- Labelling and Incubation: Label all plates clearly with method, location, and sample (A or B). Invert all plates and incubate at 30-35°C for 3-5 days [32] [30].

- Enumeration: Count the Colony Forming Units (CFUs) on all plates after incubation.

4. Data Analysis

Calculate the recovery efficiency for each method at each location using the following formula [30]:

Recovery Efficiency (%) = [1 – (B / A)] x 100

Where:

A= total CFU count from the first sample.B= total CFU count from the second sample taken from the exact same spot. Calculate the mean recovery efficiency for each of the three methods from the 20 locations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| RODAC Contact Plates | Specialized agar plates poured with a convex surface. Designed for direct impression sampling of flat surfaces, providing a standardized area (e.g., 24 cm²) for microbial collection [30] [36]. |

| TSA with Neutralizers | Tryptic Soy Agar is a general growth media. The addition of neutralizing agents (lecithin & polysorbate 80) is critical to deactivate disinfectant residues on sampled surfaces, preventing false negatives [29]. |

| Validated Swabs | Swabs with heads made of modern materials (e.g., polyester, foam) for superior recovery versus cotton. The material and handle should be compatible with the target analyte and extraction process [34] [31]. |

| Sterile Sampling Buffers | Solutions used to pre-moisten swabs, aiding in the dissolution and pickup of residues. The buffer must not interfere with the sanitizers used or the subsequent analytical detection method [31]. |

Surface Sampling Decision Workflow

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I determine the minimum number of sampling locations for my cleanroom certification?

The minimum number of sampling locations for cleanroom certification is determined by ISO 14644-1 standards and is based on the floor area of the cleanroom. The formula is NL = √A, where NL is the minimum number of locations and A is the cleanroom area in square meters. You should round NL up to the nearest whole number. This calculation ensures adequate spatial coverage to provide a representative assessment of airborne particulate cleanliness throughout the entire cleanroom. Remember that locations should be distributed evenly across the area of the cleanroom, and additional locations may be warranted in areas with critical processes or where contamination risk is highest [37].

Q2: What is the difference between "at rest" and "in operation" testing, and when should each be performed?

The cleanroom state fundamentally influences particle counts and determines when testing should occur [37]:

- "At Rest" state refers to the condition where the installation is complete with all equipment installed and operating, but no personnel present. This state verifies that the cleanroom infrastructure itself (HVAC, filters, construction) is capable of meeting the specified ISO Class.

- "In Operation" state is the condition where the installation is functioning in the specified manner, with the agreed number of personnel present and working. This state is critical for Performance Qualification (PQ) as it confirms the cleanroom can maintain its classification under actual working conditions, accounting for contamination generated by personnel, processes, and equipment [37].

Initial certification typically involves testing in both states. Routine monitoring, as required by ISO 14644-2, is performed "in operation" to demonstrate ongoing compliance during normal working conditions [37].

Q3: My particle counts are consistently within limits but show a slow upward trend. What does this indicate?

A slow, consistent upward trend in particle counts, even within specified limits, is a significant early warning signal. This trend often precedes a compliance failure and should trigger a root cause investigation. Potential causes include [38] [37]:

- Declining Filter Performance: HEPA or ULPA filters may be approaching the end of their service life and losing efficiency.

- Changes in Personnel Practices: Deterioration in gowning procedures or an increase in personnel movement can introduce more particles.

- Compromised Cleanroom Integrity: Check for leaks in filters, wall seals, or ceiling grids, and ensure pressure differentials are being maintained.

- Ineffective Cleaning Protocols: The current cleaning frequency, techniques, or materials may be inadequate for the operational load.

Initiate an investigation focusing on these areas. The trend data should be part of your routine review as required by ISO 14644-2, which emphasizes monitoring for trends to enable proactive interventions [37].

Q4: How often should I monitor non-viable particles in an operational ISO Class 5 environment?

ISO 14644-2 outlines the requirements for monitoring plan frequency. For an ISO Class 5 environment, which is critical for processes like sterile product filling, the monitoring is typically continuous or at very short intervals. The standard promotes a risk-based approach, meaning the frequency should be justified by the criticality of the process and historical data. For an ISO Class 5 zone, this almost always necessitates continuous monitoring with a particle counter to immediately detect any adverse events that could compromise product quality. For less critical areas (e.g., ISO Class 8), periodic monitoring may be sufficient, but the trend is moving towards more frequent data collection to ensure better control [38] [37].

Q5: What are the most common errors in sample handling that can compromise surface measurement results?

Common errors occur during sampling, transport, and storage, leading to inaccurate measurements [39]:

- Improper Sampling Technique: Using non-sterile or shedding wipers, applying inconsistent pressure or pattern during surface sampling, and failing to sample a defined area.

- Incorrect Identification & Labeling: Failure to apply a unique identifier immediately after sample collection can lead to mix-ups and lost data integrity.

- Poor Storage Conditions: Storing samples at the wrong temperature or humidity, or using contaminated containers, can lead to particle agglomeration, chemical changes, or microbial growth, altering the sample's properties.

- Delays in Processing: Extended time between sample collection and analysis can allow for sample degradation or contamination.

Adherence to standardized protocols for each step is crucial for reliable data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Spike in Particle Counts During Routine Operations

- Symptoms: A sudden, significant increase in non-viable particle counts reported by a continuous monitor or during a periodic test.

- Possible Causes & Corrective Actions:

| Possible Cause | Investigation Steps | Immediate Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Personnel Activity | Review video footage (if available) and interview staff for recent activity near the sensor. | Reinforce proper gowning and aseptic technique. Restrict unnecessary movement and personnel count. |

| Equipment Malfunction | Check the particle counter for error codes, verify calibration status, and inspect tubing for leaks or blockages. | Use a backup particle counter to verify readings. Isolate and repair faulty equipment. |

| Breach in Integrity | Perform a visual inspection of the cleanroom for open doors, damaged ceiling tiles, or torn filter media. | Secure any open doors or panels. Isolate the affected area from critical processes until repaired. |

| Maintenance Activity | Check the maintenance log for recent work in or near the cleanroom that could have disturbed particles. | Enhance cleaning protocols following any maintenance. Review and improve maintenance procedures to minimize contamination. |

Problem: Inconsistent Particle Counts Between Two Adjacent Sampling Locations

- Symptoms: Two sampling locations of the same classification show a consistent, significant difference in particle counts.

- Possible Causes & Corrective Actions:

| Possible Cause | Investigation Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Airflow Disruption | Perform an airflow visualization study (smoke test) to identify obstructions, turbulent flow, or dead zones. | Reposition equipment or furniture blocking airflow. Consult HVAC engineer to rebalance air supply if needed. |

| Proximity to Contamination Source | Audit the area around the higher-count location for particle-generating equipment, high-traffic pathways, or material transfer hatches. | Relocate the particle-generating activity or the sampling location. Implement additional local contamination control measures. |

| Sensor Issue | Swap the two particle counters and repeat the test to see if the high count follows the instrument. | Recalibrate or service the faulty sensor. Follow a regular calibration schedule for all monitoring equipment. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Methodology for Establishing an Operational Control Programme (OCP)

The 2025 revision of ISO 14644-5 establishes the requirement for an Operational Control Programme (OCP) as the foundation for cleanroom operations [40] [41]. This methodology outlines its implementation.

- Define Scope and Responsibilities: Clearly outline the cleanroom zones covered by the OCP and assign roles and responsibilities for its management, monitoring, and review.

- Establish Operational Procedures: Develop and document Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for all critical operations based on the consolidated guidance in ISO 14644-5:2025. This includes [40] [41]:

- Gowning: Reference IEST-RP-CC003 for garment selection and usage [40].

- Cleaning and Disinfection: Define frequencies, methods, and approved agents.

- Material Transfer: Specify decontamination procedures for all items entering the cleanroom.

- Personnel Training: Ensure all personnel are trained and competent on OCP procedures.

- Implement a Monitoring Plan: As per ISO 14644-2, establish a plan for continuous or frequent monitoring of parameters like airborne particles, pressure differentials, and temperature/humidity [37].

- Define Alert and Action Limits: Set levels that trigger a response, ensuring they are tighter than the ISO classification limits to provide an early warning.

- Create a Response Plan: Document immediate and corrective actions to be taken when monitoring data exceeds alert or action levels.

- Review and Update: Schedule periodic reviews of the entire OCP to ensure its effectiveness and adapt to any process changes.

The following workflow visualizes the core principles and cyclical nature of an effective OCP:

Protocol 2: Systematic Approach to Selecting and Qualifying Cleanroom Consumables

The updated ISO 14644-5:2025 integrates the principles of ISO 14644-18, placing greater emphasis on the qualification of consumables to minimize contamination risk [40].

- Risk Assessment: Identify all consumables (wipers, gloves, garments) and assess their potential impact on product quality based on their application.

- Define Qualification Criteria: Establish acceptance criteria for each consumable type. The standard now references IEST Recommended Practices for detailed test methods [40]:

- For Wipers (IEST-RP-CC004): Test for particle release, absorbency, and chemical compatibility.

- For Gloves (IEST-RP-CC005): Test for barrier integrity, particle shedding, and static dissipation.

- Supplier Qualification: Audit and approve suppliers based on their ability to consistently provide consumables that meet your qualification criteria and their own quality management systems.

- Initial Sampling and Testing: Perform incoming inspection and testing on initial lots of the consumable to verify it meets all defined criteria.

- Maintain Documentation: Keep complete records of qualification data, certificates of analysis, and supplier approvals. Update procurement standards to reflect the new ISO 14644-5 and IEST guidelines [40].

- Periodic Re-qualification: Establish a schedule for re-testing consumables to ensure ongoing compliance, especially if a supplier changes their manufacturing process.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key materials used in maintaining and monitoring cleanroom environments for accurate research.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| HEPA/ULPA Filters | High/Ultra Low Penetration Air filters are the primary contamination control barrier in the HVAC system, removing airborne particles from the cleanroom supply air to meet ISO Class requirements [38] [37]. |

| Validated Cleanroom Wipers | Used for cleaning and wiping surfaces; qualified per IEST-RP-CC004 to have low particle and fiber release, high absorbency, and chemical compatibility to prevent introducing contamination [40]. |

| Cleanroom Garments | Act as a primary barrier against human-shed particles; selected and managed per IEST-RP-CC003. Material and design are critical for controlling personnel-derived contamination [38] [40]. |

| Static-Dissipative Gloves | Protect sensitive products from electrostatic discharge (ESD) and operator contamination. Qualified per IEST-RP-CC005 for barrier performance and low particle shedding [40]. |

| Particle Counter | The key instrument for certifying and monitoring cleanroom ISO Class by counting and sizing airborne non-viable particles. Requires regular calibration to ensure data accuracy [37]. |

| Appropriate Disinfectants | Validated cleaning and disinfecting agents that are effective against microbes while leaving minimal residue and being compatible with cleanroom surfaces [38]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

Low Analyte Recovery

Symptom: Analyte recovery is less than 100%, potentially observed as analyte present in the "flow through" fraction. [42]

| Cause | Solution/Suggestion |

|---|---|

| Improper column conditioning | Condition column with sufficient methanol or isopropanol; follow with one column volume of a solution matching sample composition (pH-adjusted); avoid over-drying. [42] |

| Sample in excessively "strong" solvent | Dilute sample in a "weaker" solvent; adjust sample pH so analyte is neutral; add salt (5-10% NaCl) for polar analytes; use an ion-pair reagent. [42] |

| Column mass overload | Decrease sample volume loaded; increase sorbent mass; use a sorbent with higher surface area or strength. [42] [43] |

| Excessive flow rate during loading | Decrease flow rate during sample loading; increase sorbent mass. [42] |

| Sorbent too weak for analyte | Switch to a "stronger" sorbent with higher affinity or ligand density. [42] |

Flow Rate Issues

Symptom: Flow rate is too fast (reducing retention) or too slow (increasing run time). [43]

| Cause | Solution/Suggestion |

|---|---|

| Packing/bed differences | Use a controlled manifold or pump for reproducible flows; aim for flows below 5 mL/min for stability. [43] |

| Particulate clogging | Filter or centrifuge samples before loading; use a glass fiber prefilter for particulate-rich samples. [43] |

| High sample viscosity | Dilute sample with a matrix-compatible solvent to lower viscosity. [43] |

Poor Reproducibility

Symptom: High variability between replicate runs. [43]

| Cause | Solution/Suggestion |

|---|---|

| Cartridge bed dried out | Re-activate and re-equilibrate the cartridge to ensure the packing is fully wetted before loading. [43] |

| Flow rate too high during application | Lower the loading flow rate to allow sufficient contact time. [43] |

| Wash solvent too strong | Weaken wash solvent; allow it to soak in briefly and control flow at 1-2 mL/min. [43] |

| Cartridge overloaded | Reduce sample amount or switch to a higher capacity cartridge. [43] |

Unsatisfactory Cleanup

Symptom: Inadequate removal of matrix interferences. [43]

| Cause | Solution/Suggestion |

|---|---|

| Incorrect purification strategy | For targeted analyses, choose a strategy that retains the analyte and removes the matrix via selective washing; prioritize sorbent selectivity (Ion-exchange > Normal-phase > Reversed-phase). [43] |

| Suboptimal wash/elution solvents | Re-optimize wash and elution conditions (composition, pH, ionic strength); small changes can have large effects. [43] |

| Cartridge contaminants/improper conditioning | Condition cartridges per manufacturer instructions; use fresh cartridges if contamination is suspected. [43] |

General Sample Preparation Errors