Optimizing Signal Detection in Surface Spectroscopy: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research

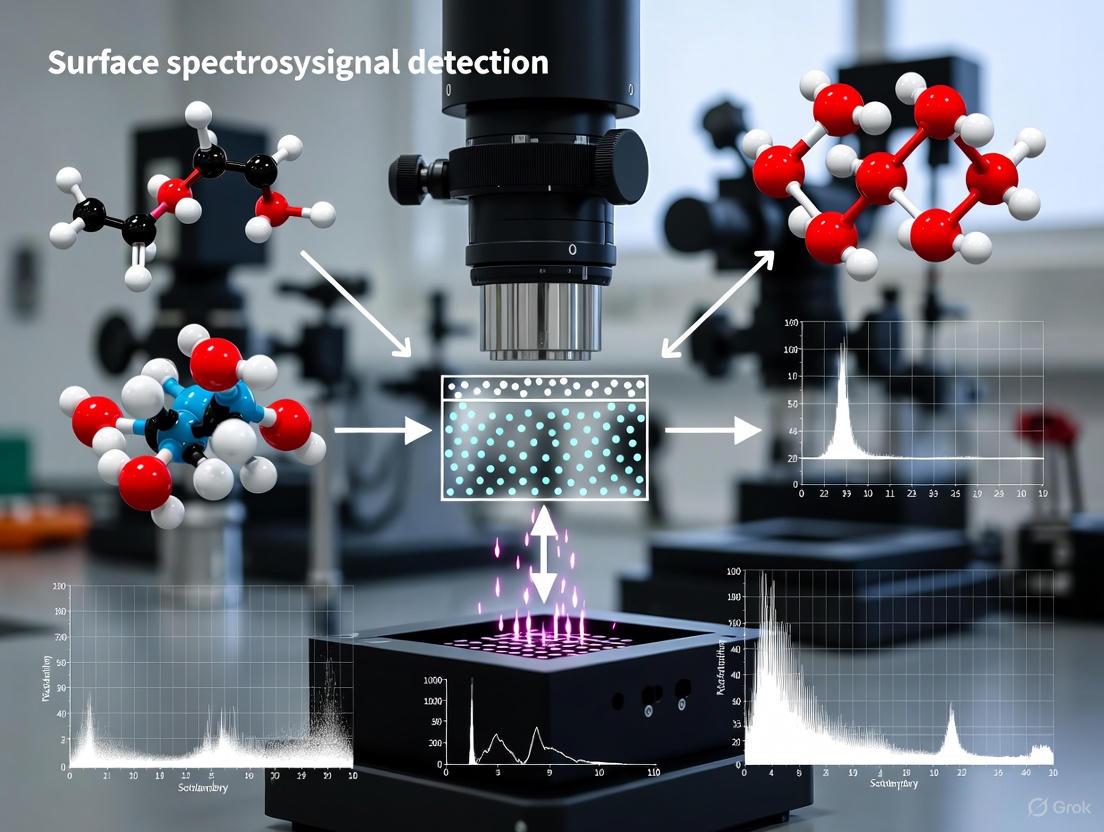

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on enhancing signal detection in key surface spectroscopy techniques, including Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Surface Plasmon Resonance...

Optimizing Signal Detection in Surface Spectroscopy: Advanced Strategies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on enhancing signal detection in key surface spectroscopy techniques, including Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). It explores the fundamental principles of signal generation and enhancement, details cutting-edge methodological and application advances in biomedicine, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization protocols for common experimental challenges, and evaluates validation frameworks and comparative performance of emerging technologies. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with advanced optimization strategies, this resource aims to empower scientists to achieve highly sensitive, reproducible, and clinically relevant data from surface spectroscopic analyses.

Core Principles and Signal Enhancement Mechanisms in Surface Spectroscopy

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common operational challenges in X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS), providing targeted solutions to maintain data integrity.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

- Q: What are common data collection and analysis errors in XPS? Persistent difficulties in XPS include improper handling of XPS backgrounds, errors in peak fitting, and incomplete reporting of instrument parameters, which can compromise data interpretation. Always follow established guidelines for data acquisition and analysis to avoid these common pitfalls [1].

- Q: Why might my conductive tape not be working, and what is 'preferential sputtering'? Conductive tape can sometimes be insulating rather than conductive, leading to sample charging. Preferential sputtering, where different elements are removed at different rates during ion etching, can alter the surface stoichiometry of your sample. Both are recognized common issues in XPS operation [2] [3].

- Q: How does prior SEM analysis affect my XPS results? Operating a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) on a sample before XPS analysis can deposit a layer of carbon on the area to be analyzed, contaminating the surface and skewing the XPS results [2] [3].

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

- Q: My AES data shows peak overlaps. How can I resolve this? Peak overlaps, such as Al over Cu or Sb over O, are a common difficulty. Utilizing the Auger parameter, which involves both the photoelectron and Auger peaks, can help in identifying chemical states and resolving these overlaps [4] [3].

- Q: What is the impact of a magnetic lens on Angle-Resolved XPS (AR-XPS), and could this affect AES? The magnetic lens used in some systems can have an effect on AR-XPS measurements. While directly noted for XPS, this is a important consideration for any electron spectroscopy technique, including AES, where lens effects can influence data collection [3].

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS)

- Q: How can I achieve accurate mass scale calibration in TOF-SIMS? Achieving good mass accuracy is challenging but critical. A detailed calibration protocol that accounts for factors like ion kinetic energy and emission angle can improve relative mass accuracy to better than 10 ppm for masses up to 140 u, which is essential for the unique identification of species [5].

- Q: What is a key advantage of operando SIMS analysis for battery research? Operando SIMS allows for the investigation of dynamic degradation and mass transport in systems like solid-state batteries under operating conditions. This technique can chemically identify processes like sodiation and solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) composition without exposing the highly reactive surfaces to ambient air, which could alter them [6].

The table below summarizes key quantitative information from the cited research to aid in experimental planning and comparison.

Table 1: Summary of Quantitative Experimental Data from Literature

| Analysis Technique | Key Parameter | Reported Value / Finding | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operando SIMS [6] | Critical Current Density (CCD) | 0.04 μA μm⁻² | Maximum tolerated current density before failure at Na metal|NASICON interface. |

| TOF-SIMS [5] | Mass Accuracy (after new protocol) | <10 ppm (up to 140 u) | A factor of 5 improvement over common calibration procedures. |

| SERS [7] | Signal Enhancement Factor | ∼21,500-fold (vs. conventional Raman) | For optimized rGO/AgNPs substrate detecting pesticides. |

| SERS [7] | Detection Limit for Ametryn | 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ | On apple and potato peels using the optimized substrate. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Operando Simultaneous Dual-Polarity SIMS for Solid-State Battery Interface Analysis

This protocol details the methodology for investigating dynamic degradation at the sodium metal|NASICON solid electrolyte interface, pioneering a diagnostic tool for next-generation batteries [6].

- 1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a solid-state sodium-ion half-cell using a NASICON solid electrolyte (e.g., Na₃.₄Zr₂Si₂.₄P₀.₆O₁₂) with a sodium metal electrode on the underside.

- Mount the cell in the main stage of a Hi-5 SIMS instrument.

- 2. Instrument Setup:

- Use Kliendiek micro-manipulator probes to make working electrode (WE) and counter electrode (CE) connections on the NASICON surface.

- The red square in the optical image is used for guidance to highlight the area where the beam can be applied.

- 3. Operando Electrochemical Cycling:

- Apply a constant current to generate an electric field at specific regions on the NASICON surface, creating a potential difference.

- Sodium ions (Na⁺) diffuse from the sodium metal electrode towards the probe positions.

- Cycle at different current densities (e.g., from 0.02 to 0.5 μA μm⁻²) in a 1 μm² region to form operando sodium metal|NASICON interfaces and determine the Critical Current Density (CCD).

- 4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS):

- Perform EIS on the formed interfaces.

- Fit the EIS data to equivalent circuit models to identify components, such as a resistive solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), that facilitate sodiation.

- 5. Simultaneous Dual-Polarity SIMS Analysis:

- Analyze the sodiated regions with dynamic dual-polarity SIMS, which allows the simultaneous detection of both positive and negative secondary ions.

- Chemically identify the composition of the SEI and map sodium mass transport columns.

- Key fragments to monitor include ZrO₂, SiO₂, and PO₂, indicating decomposition products like Na₂ZrO₃, Na₂SiO₃, and Na₃P.

Protocol: Integrated Suppression of Acoustic Echo and Background Noise

This protocol describes a novel frequency-domain approach to suppress both acoustic echo and background noise simultaneously within a soft decision framework, avoiding issues of conventional combined structures [8].

- 1. Signal Acquisition and DFT:

- Acquire the input signal from the microphone and the far-end speech signal.

- Convert these time-domain signals into the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) spectrum for processing, frame by frame.

- 2. Hypothesis Formulation:

- Define two hypotheses for the DFT spectrum of the microphone input signal Y(i,k), where i is the time index and k is the frequency index:

- H₀ (Near-end speech absent): Y(i,k) = D(i,k) + E(i,k)

- H₁ (Near-end speech present): Y(i,k) = D(i,k) + E(i,k) + S(i,k)

- where D is background noise, E is echo signal, and S is near-end speech.

- Define two hypotheses for the DFT spectrum of the microphone input signal Y(i,k), where i is the time index and k is the frequency index:

- 3. Estimate Combined Power of Echo and Noise (λcd):

- Echo Power (λe) Estimation:

- During single-talk periods (near-end speech absent), estimate the echo spectral magnitude |Ê(i,k)| using |Ê(i,k)| = H(i,k)|Xd(i,k)|, where Xd is the far-end signal.

- Estimate the echo path response filter H(i,k) iteratively using a magnitude least squares estimator: H(i,k) = E[Xd*(i,k)Y(i,k)] / E[Xd*(i,k)Xd(i,k)].

- Update the echo power variance λₑ(i,k) using smoothing: λ̂ₑ(i,k) = α{λₑ} λ̂ₑ(i-1,k) + (1-α{λₑ})|Ê(i,k)|².

- Freeze the update of H(i,k) during double-talk periods using a frequency-domain double-talk detector.

- Noise Power (λd) Estimation:

- Estimate the background noise power during periods of near-end speech and echo absence.

- Combine Powers: The combined power to be suppressed is λcd(i,k) = λe(i,k) + λ_d(i,k).

- Echo Power (λe) Estimation:

- 4. Calculate Suppression Gain via Soft Decision:

- Compute the a posteriori signal-to-combined power ratio (SCR): γ(i,k) = |Y(i,k)|² / λcd(i,k).

- Estimate the a priori SCR ξ(i,k) using a decision-directed approach: ξ̂(i,k) = αDD |Ŝ(i-1,k)|² / λ̂cd(i-1,k) + (1-αDD)P[γ(i,k)-1].

- Compute the likelihood ratio Λ(Y(i,k)) and the near-end speech absence probability (NSAP) p(H₀|Y(i,k)).

- Determine a single spectral suppression gain G(i,k) based on p(H₀|Y(i,k)) and the estimated parameters.

- 5. Apply Gain and Synthesize Output:

- Apply the gain to the microphone input spectrum to obtain an estimate of the clean near-end speech spectrum: Ŝ(i,k) = G(i,k) Y(i,k).

- Transform Ŝ(i,k) back to the time domain to produce the output speech signal.

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions as derived from the featured experiments and techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Context |

|---|---|---|

| NASICON Solid Electrolyte (e.g., Na₃.₄Zr₂Si₂.₄P₀.₆O₁₂) | Serves as the sodium ion-conducting electrolyte in a solid-state battery model system. | Enables operando study of sodium metal|solid electrolyte interfaces and degradation mechanisms [6]. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide/Silver Nanoparticles (rGO/AgNPs) | Acts as an optimized substrate for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). | Provides a ~21,500-fold signal enhancement for detecting trace analytes like pesticide residues [7]. |

| Hi-5 Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer | Instrument for performing operando simultaneous dual-polarity SIMS analysis. | Allows correlation of electrochemical data with chemical analysis at the nanoscale under operating conditions [6]. |

| Sodium Metal Electrode | Functions as the anode in the solid-state sodium-ion half-cell. | Provides the source of sodium ions (Na⁺) for sodiation and interface formation during operando cycling [6]. |

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has developed into a powerful analytical technique capable of detecting trace amounts of analytes, down to the single-molecule level in some cases [9]. The extraordinary sensitivity of SERS stems from two primary signal enhancement mechanisms: the electromagnetic mechanism (EM) and the chemical mechanism (CM) [9] [10]. The EM arises from the excitation of localized surface plasmons on nanostructured metal surfaces, which generates intensely concentrated electromagnetic fields [11]. The CM, while contributing a lesser degree of enhancement, involves charge transfer between the analyte molecule and the substrate, which can alter the polarizability of the molecule [9] [10]. For researchers in spectroscopy and drug development, understanding and optimizing these mechanisms is crucial for developing highly sensitive and reliable detection assays. This guide addresses frequent experimental challenges and provides methodologies for maximizing SERS performance in your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

1. Why is my SERS signal weak or inconsistent, even with a known good substrate?

Weak or inconsistent signals are among the most common frustrations in SERS experiments. The causes and solutions are often related to the nanostructures and molecular positioning:

- Cause: Lack of or Inconsistent "Hotspots": The vast majority of the SERS signal originates from nanoscale gaps and crevices in the substrate, known as "hotspots," where the electromagnetic field is most intense [12]. Small changes in the number of molecules residing in these hotspots can create large intensity variations. This is particularly problematic when using colloidal nanoparticles, where it can be very challenging to aggregate nanoparticles in a reproducible manner [12].

- Solution:

- For colloidal assays, standardize the aggregation process by using the same concentration of an aggregating agent (e.g., salts like NaCl or MgSO₄) and consistent mixing times.

- Consider switching to commercially available or lithographically fabricated patterned nanostructures, which offer better reproducibility, though they can still have intensity variations on the order of 10% [12].

- To average out heterogeneity, measure multiple spots on your substrate; one study suggested that more than 100 spots are needed to properly capture this variance [12].

2. My target molecule doesn't seem to produce a SERS signal. What could be wrong?

Not all molecules enhance equally, and the SERS effect is a very short-range phenomenon.

- Cause 1: Poor Adsorption to the Surface: The SERS enhancement decays rapidly within a few nanometers from the metal surface [12]. If your molecule does not adsorb to the surface, it will not experience a significant enhancement. Furthermore, the number of molecules at the surface often follows a Langmuir isotherm, meaning low surface coverage occurs if the molecule has low affinity for the surface [12].

- Solution: Functionalize your substrate to promote adsorption. For example, using aromatic thiols or creating charge-transfer complexes can boost signals [12]. For difficult molecules like glucose, this involves surface functionalization with a capture agent, such as boronic acid [12].

- Cause 2: Inherently Low SERS Responsiveness: Some molecules, such as glucose, have a low natural SERS cross-section [12].

- Solution: Employ a SERS "tag" strategy. Attach a reporter molecule (e.g., rhodamine, aromatic thiol) that gives a strong, known SERS signal to the nanoparticle. Then, functionalize the nanoparticle with a recognition element (e.g., antibody, DNA aptamer) that binds to your target molecule [12].

3. The SERS spectrum I obtained doesn't match the standard Raman spectrum of my molecule. Why?

It is a common misconception that a SERS spectrum is simply an intensified version of a normal Raman spectrum.

- Cause 1: Changes in Selection Rules and Molecular Orientation: Adsorption to a metal surface can change the symmetry of the molecule [9]. This can cause normally Raman-inactive modes to become active, or certain vibrational modes to be enhanced more than others based on their alignment with the enhanced electric field [9] [12].

- Cause 2: Surface Chemistry or Photoreactions: The electrons in the metals that generate the plasmon resonance can also drive chemistry on the analytes [12]. A classic example is para-aminothiophenol, which was initially thought to show altered selection rules but was later found to form dimercaptoazobenzene on the surface [12].

- Solution: Use low laser powers (generally less than 1 mW in a diffraction-limited focus) to minimize photoreactions and heating [12]. The best practice is to generate a calibration curve with known concentrations of your analyte at these low laser powers [12].

4. How can I make my SERS measurements more quantitative?

The hotspot-dominated nature of SERS makes quantitative analysis challenging but achievable.

- Cause: Inhomogeneous Distribution of Enhancements: The significant spatial variation in signal intensity means that the measured signal is not a simple linear function of concentration [12].

- Solution: Use an internal standard. This is a compound that is co-adsorbed with your analyte and is assumed to experience the same enhancement factors. The analyte signal is then normalized to the internal standard's signal. This can be a co-adsorbed molecule, or, preferably, a stable isotope variant of the target molecule itself [12].

Quantitative Data and Enhancement Factors

The Enhancement Factor (EF) is the key metric for quantifying SERS substrate performance. It is calculated as [12]:

EF = (I_SERS / N_SERS) / (I_Raman / N_Raman)

where I_SERS and I_Raman are the SERS and normal Raman scattering intensities, and N_SERS and N_Raman are the number of molecules probed under SERS and normal conditions, respectively.

The table below summarizes typical enhancement factors for different substrate types, illustrating how combining EM and CM can yield superior performance.

Table 1: Enhancement Factors and Limits of Detection for Select SERS Substrates

| Substrate Material | Enhancement Mechanism | Reported Enhancement Factor (EF) | Probe Molecule | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Primarily EM | ~10⁶ - 10⁸ (varies with aggregation) | Rhodamine 6G | Varies with aggregation | [12] [10] |

| Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene | Primarily CM | Relatively limited | Methyl Violet | Not competitive alone | [10] |

| Au–Ti₃C₂Tₓ Composite | Combined EM & CM | 3.9 × 10⁶ | Methyl Violet | 10⁻⁷ M | [10] |

| Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs Composite | Synergistic EM & CM | 3.8 × 10⁸ | Rhodamine 6G (R6G) | 10⁻¹⁴ M (fM level) | [10] |

Table 2: Key Properties of Common Plasmonic Metals for SERS

| Metal | Plasmon Resonance Range | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver (Ag) | Visible-NIR | Strongest EM enhancement, high EF [10] | Prone to oxidation/tarnishing |

| Gold (Au) | Visible-NIR | Biologically inert, stable | Lower EF than Ag [10] |

| Copper (Cu) | Visible | Lower cost | Susceptible to oxidation [9] |

| Aluminum (Al) | UV | Unique for UV-SERS applications [9] | Less common for visible/NIR experiments |

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Signal Enhancement

Protocol 1: Fabricating a Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs Composite Substrate for Synergistic EM-CM Enhancement

This protocol, adapted from recent research, details the creation of a highly sensitive substrate that leverages both electromagnetic and chemical enhancement [10].

Principle: Positively charged cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-capped Ag nanoparticles are electrostatically self-assembled onto negatively charged Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene nanosheets. The AgNPs provide strong EM via localized surface plasmon resonance, while the MXene facilitates CM via charge transfer with adsorbed analyte molecules [10].

Materials:

- Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene nanosheet solution (commercially available)

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃)

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄)

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)

- Target analyte molecules (e.g., R6G, biomarkers)

Procedure:

- Synthesis of CTAB-capped AgNPs: Synthesize positively charged silver nanoparticles using CTAB as a capping and reducing agent with NaBH₄.

- Preparation of Ti₃C₂Tₓ Suspension: Dilute the commercial Ti₃C₂Tₓ solution to a standard concentration (e.g., 0.5 mg/mL) in deionized water.

- Electrostatic Self-Assembly: Gradually mix the positively charged AgNP solution with the negatively charged Ti₃C₂Tₓ suspension under constant stirring. The electrostatic attraction will drive the uniform decoration of AgNPs on the MXene sheets, creating the hybrid substrate.

- Substrate Characterization: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and UV-Vis spectroscopy to confirm the successful and uniform assembly of AgNPs on the MXene.

- SERS Measurement: Drop-cast the analyte solution onto the prepared Ti₃C₂Tₓ/AgNPs composite substrate. After the solvent evaporates, acquire SERS spectra. The coupling factor between EM and CM in such a system has been calculated to be as high as 33.6%, demonstrating a significant synergistic interaction [10].

Protocol 2: Employing an Internal Standard for Quantitative SERS

This protocol is essential for achieving reliable quantitative results, especially when using substrates with inherent hotspot heterogeneity [12].

Principle: An internal standard (IS) molecule is introduced alongside the target analyte. This IS should adsorb to the substrate in a similar manner and its SERS signal is used to normalize the analyte signal, correcting for variations in laser power, substrate enhancement, and molecular density.

Materials:

- SERS substrate (e.g., colloidal AgNPs, patterned chip)

- Target analyte

- Internal standard molecule (e.g., a stable isotope variant of the analyte, or a co-adsorbing molecule with a distinct, non-overlapping Raman peak) [12]

Procedure:

- Prepare a Mixture: Create a solution containing a known, fixed concentration of the internal standard and varying concentrations of your target analyte.

- Deposit on Substrate: Apply the mixture to your SERS substrate uniformly.

- Acquire SERS Spectra: Collect spectra from multiple spots to account for spatial heterogeneity.

- Data Analysis: For each spectrum, identify the peak intensities of the analyte (

I_analyte) and the internal standard (I_IS). Calculate the normalized response as the ratioI_analyte / I_IS. Plot this ratio against the analyte concentration to build a robust calibration curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SERS Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Role in SERS | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles | Provides the primary EM enhancement via LSPR. | AgNPs, AuNPs [9] [10] |

| 2D Material Substrates | Provides a platform for CM via charge transfer; can improve stability and reproducibility. | Graphene, MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) [9] [10] |

| Aggregating Agents | Induces nanoparticle aggregation to form EM hotspots in colloidal assays. | NaCl, MgSO₄, KCl [12] |

| Internal Standards | Enables normalization for quantitative SERS measurements. | Deuterated compounds, 4-mercaptobenzoic acid [12] |

| Surface Functionalizers | Promotes specific adsorption of target molecules to the surface; enables SERS-tag strategies. | Thiols, boronic acid, antibodies, DNA aptamers [12] |

Enhancement Mechanism and Troubleshooting Workflows

Diagram 1: SERS Enhancement and Troubleshooting

Diagram 2: SERS Signal Enhancement Pathways

HAXPES and NAP-XPS for Deeper and In-Situ Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides

NAP-XPS Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for NAP-XPS Operation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor signal-to-noise ratio at elevated pressure | Signal attenuation due to electron scattering in the gas phase. | Optimize gas pressure; use a differentially pumped analyzer; position the analyzer close to the sample. | [13] [14] |

| Uncertainty if UHV measurements represent the state in reactive atmospheres | Surface state changes when transferring sample from gas environment to UHV. | Use NAP-XPS for direct in situ characterization under relevant gas pressures (up to 100 mbar). | [14] |

| Sample charging on insulating oxide surfaces | Low electrical conductivity of the sample at lower temperatures. | Perform measurements at elevated temperatures (e.g., 300-400 °C) to enhance ionic mobility and conductivity. | [14] |

| Unstable surface state under vacuum after gas exposure | Potential surface reconstruction or reduction when reactive gas is evacuated. | Compare spectra in gas and UHV. A stable binding energy indicates the surface state is maintained. | [14] |

| Pressure gap between UHV studies and real-world catalytic conditions | Inability to simulate atmospheric pressure conditions in standard XPS. | Utilize a NAP-XPS system with a specialized reaction cell to bridge the "pressure gap." | [13] [14] |

Data Analysis and Reporting Errors

Table 2: Guide to Common XPS Data Analysis Errors

| Error Category | Common Mistake | Correct Practice | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Fitting | Over-fitting with too many peaks. | Use the minimum number of components justified by chemical knowledge. | [1] |

| Background Handling | Applying an incorrect background subtraction model. | Select the background model (e.g., Shirley, Tougaard) appropriate for the sample and spectrum. | [1] |

| Reporting | Failing to report essential instrument parameters. | Always report X-ray source, analyzer settings, pass energy, and step size for reproducibility. | [1] |

| Data Presentation | Showing only peak-fitted data without the original spectrum. | Always overlay the fitted model on the raw data to allow critical evaluation. | [1] |

| Chemical State Identification | Incorrectly assigning peaks without proper reference. | Compare binding energies with reliable databases or standard samples. | [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using NAP-XPS over conventional XPS? NAP-XPS allows for the direct analysis of samples under "near-ambient" pressure conditions (up to 100 mbar), bridging the critical "pressure gap" between surface science and real-world applications like catalysis. This enables researchers to study the chemical state of a surface in situ during gas-solid interactions, which may not be preserved when the sample is transferred to a UHV environment for conventional XPS analysis [13] [14].

Q2: How stable is a surface state created in a gas environment when we evacuate the chamber for analysis? Research on complex oxides has shown that for some systems, the surface state formed under an O₂ atmosphere (e.g., 3.5 mbar) can remain largely stable and be maintained when the chamber is evacuated to UHV conditions. This stability can be verified by comparing the binding energy and shape of photoemission peaks, such as the O 1s spectrum, recorded in both environments [14].

Q3: My sample is an insulating material and is charging. What can I do in a NAP-XPS experiment? For certain materials, such as solid oxide ion conductors, performing experiments at elevated temperatures (e.g., 300-400 °C) can be an effective strategy. The increased temperature enhances the material's ionic mobility and electrical conductivity, thereby mitigating electrostatic charging effects induced by the photoelectron emission process [14].

Q4: Besides chemical composition, what unique information can NAP-XPS provide? The correlation of XPS spectra recorded in gas and UHV environments can provide insights into the electrical conductivity of specific surface sites. Shifts in the binding energy of photoemission peaks between these two conditions can be correlated with the electrical properties of different components in a complex material, which is crucial for applications like solid oxide electrochemical devices [14].

Q5: What are the most critical parameters to report when publishing XPS/NAP-XPS data? To ensure reproducibility and reliability, you must report key instrument parameters including the type of X-ray source (monochromatic or non-monochromatic, anode material), the analyzer (model, pass energy, slit settings), the energy step size, and the method used for background subtraction and peak fitting [1].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Comparing Surface States in O₂ and UHV using NAP-XPS

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating complex oxides for solid oxide electrochemical cells [14].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Use well-characterized samples (e.g., Ni/yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) cermet or La0.75Sr0.25Cr0.9Fe0.1O3 perovskite).

- Ensure samples are clean and mounted appropriately for the NAP-XPS holder, capable of heating.

2. In Situ Treatment and Data Acquisition:

- Introduce the sample into the NAP-XPS system and pump down to UHV.

- Heat the sample to the target temperature (e.g., 300 °C).

- Introduce O₂ gas into the analysis chamber to the desired pressure (e.g., 3.5 mbar).

- Acquire core-level spectra (e.g., Ni 2p, O 1s, La 3d, Fe 2p) under the O₂ atmosphere.

- After data collection in gas, carefully evacuate the analysis chamber back to UHV conditions while maintaining the sample temperature.

- Acquire the same core-level spectra again, ensuring all instrument parameters (analyzer pass energy, step size, etc.) are identical to the previous measurement.

3. Data Analysis:

- Compare the spectra collected in O₂ and UHV without any binding energy scale correction.

- Look for changes in peak position, shape, and the presence of satellite features.

- A stable peak position indicates the surface state formed in O₂ is maintained in UHV.

- Shifts in binding energy for specific elements can be correlated with their local electrical conductivity at the surface.

Workflow Diagram: NAP-XPS for In-Situ Surface Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for an experiment comparing surface states under gas and vacuum environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Components for NAP-XPS Experiments

| Item | Function / Relevance in HAXPES/NAP-XPS | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Differentially Pumped Analyzer | Enables electron detection under elevated pressure by maintaining UHV in the detector despite pressure in the analysis chamber. | PHOIBOS 150 NAP analyzer [13]. |

| In Situ Reaction Cell | A small-volume chamber connected to the analyzer, allowing for efficient gas exchange and study of reactions in a controlled environment. | DeviSim reaction cell [13]. |

| Complex Oxide Materials | Model systems for studying surface chemistry, catalysis, and electrochemistry under operando conditions. | Ni/YSZ cermets, LSCF perovskites [14]. |

| Synchrotron X-ray Source | Provides high-flux, tunable X-rays, which are often used in NAP-XPS for high signal-to-noise ratio and depth-profiling via variable energy. | Used via a windowless beam entrance stage [13] [14]. |

| Monochromated Lab X-ray Source | A laboratory-based alternative to synchrotron radiation, offering high energy resolution for precise chemical state analysis. | Small spot X-ray source [13]. |

The Role of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance in Signal Amplification

Core Concepts of LSPR Signal Amplification

What is LSPR and how does it enable signal amplification?

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) is an optical phenomenon occurring in noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver) where collective electron charge oscillations generate a highly localized evanescent field when excited by light. This field is extremely sensitive to minute changes in the local nano-environment, such as refractive index variations caused by molecular binding events. Signal amplification is achieved because this enhanced electromagnetic field significantly increases the detector's response to small molecular interactions, allowing for highly sensitive, label-free detection of biomolecules. [16]

What are the primary mechanisms for enhancing LSPR signals?

LSPR signal enhancement can be achieved through several key strategies:

- Refractive Index Management: Optimizing the thickness and properties of dielectric coatings (e.g., mesoporous silica) on metal nanoparticles to maximize sensitivity to environmental changes. [17]

- Surface Functionalization: Using branched polymer templates (e.g., PAMAM dendrimers) to increase the density of capturing ligands (antibodies, aptamers) on the sensor surface, improving target capture probability and binding avidity. [16]

- Plasmonic Coupling: Employing additional metallic nanoparticles (e.g., AuNPs) conjugated to targets to create coupled plasmonic systems that intensify the signal through enhanced electromagnetic fields. [16]

- Morphology Control: Utilizing nanoparticles with specific shapes (e.g., nanoflowers, nanorods) that feature sharp tips and edges to generate stronger local electric fields for superior signal enhancement. [18]

Troubleshooting Common LSPR Experimental Issues

Low Signal Intensity

Problem: The LSPR wavelength shift or signal change is weak upon analyte binding, leading to poor detection sensitivity. [19]

Solutions:

- Optimize Nanoparticle Structure: Utilize anisotropic nanoparticles like gold nanorods (Au NRs) or nanoflowers (GNFs). Au NRs offer tunable plasmon bands, while GNFs possess multiple tip structures that generate stronger local electric fields, enhancing sensitivity. [17] [18]

- Apply Signal Amplification Tags: Use secondary probes like Rolling Circle Amplification products conjugated to Gold Nanoparticles (RCA-AuNPs). These large complexes increase the mass bound to the sensor surface and enhance the plasmonic coupling effect, significantly amplifying the signal. [16]

- Increase Ligand Density: Immobilize capturing ligands (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) via multi-handled templates like PAMAM dendrimers. This increases the number of binding sites on the sensor surface, improving the probability of target capture and the overall signal. [16]

Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

Problem: Unwanted molecules adsorb to the sensor surface, causing high background noise and false-positive signals. [19] [20]

Solutions:

- Surface Passivation: Modify the sensor surface with non-fouling materials such as poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers or blocking agents like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). These materials minimize non-specific interactions from complex sample matrices. [16] [20]

- Buffer Optimization: Add mild detergents (e.g., Tween 20) to the running buffer to disrupt hydrophobic interactions, or increase ionic strength (e.g., with NaCl) to shield charge-based interactions. Typically, 0.005-0.01% Tween 20 or 150-500 mM NaCl is effective. [20]

- Optimize Ligand Orientation: Use site-specific immobilization strategies (e.g., via His-tags or biotin-streptavidin) to ensure capturing ligands are properly oriented, which maximizes specific binding and reduces non-specific surface interactions. [19]

Poor Reproducibility

Problem: Inconsistent results between experimental replicates or sensor chips. [19] [21]

Solutions:

- Standardize Nanoparticle Synthesis: Employ seed-mediated growth methods with precise control over reactant concentrations (e.g., CTAB, HAuCl₄, AgNO₃) and reaction conditions (temperature, time) to ensure batch-to-batch consistency in nanoparticle size, shape, and optical properties. [17] [18]

- Control Immobilization Chemistry: Standardize the surface activation and ligand coupling procedures. For covalent amine coupling, consistently use the same concentrations of EDC/NHS, consistent pH during ligand immobilization, and the same reaction times. [19] [22]

- Implement Rigorous Controls: Always include a reference channel or reference sensor surface that undergoes the exact same functionalization process but lacks the specific capturing ligand. This allows for real-time subtraction of bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding signals. [20]

Sensor Surface Instability or Degradation

Problem: The functionalized sensor chip loses activity over time or shows baseline drift. [21]

Solutions:

- Apply Protective Coatings: Coat nanoparticles with a thin, stable layer of silica (e.g., 2-5 nm mesoporous SiO₂). This provides a protective shell, improves chemical stability, and can be further functionalized while maintaining high sensitivity. [17]

- Ensure Proper Storage: Store functionalized sensor chips in a nitrogen atmosphere or under vacuum at 4°C. If stored in liquid, use sterile, degassed buffer with antimicrobial agents (e.g., 0.05% sodium azide) to prevent microbial growth and surface degradation. [21]

- Monitor Baseline Stability: Prior to experiments, run the flow buffer over the sensor surface for an extended period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) to achieve a stable baseline. Sudden drifts often indicate an improperly equilibrated surface. [23]

Advanced Optimization & Experimental Protocols

Optimizing Mesoporous Silica Thickness on Gold Nanorods (Au NRs)

A proven method for signal amplification involves coating Au NRs with mesoporous silica. The shell thickness is critical and can be optimized as follows: [17]

Protocol:

- Synthesize Au NRs: Use a seed-mediated growth method in the presence of Cetyltrimethyl Ammonium Bromide (CTAB) to obtain Au NRs with an aspect ratio of ~2.9 and a longitudinal LSPR peak around 726 nm. [17]

- Vary Silica Coating: By adjusting the concentration of CTAB and the amount of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) (e.g., from 2 µL to 20 µL), a series of Au NRs@SiO₂ with shell thicknesses from 2 nm to 25 nm can be synthesized. [17]

- Characterize Sensitivity: Expose the Au NRs@SiO₂ to solvents with varying refractive indices (e.g., water-glycerol mixtures). Measure the LSPR peak shift for each shell thickness and calculate the sensitivity in nm/RIU. [17]

Data Table: Sensitivity vs. Silica Shell Thickness [17]

| Silica Shell Thickness (nm) | Refractive Index Sensitivity (nm/RIU) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 390 |

| 5 | 340 |

| 10 | 280 |

| 15 | 220 |

| 20 | 170 |

| 25 | 110 |

Dendrimer-Mediated Aptamer Immobilization for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

This protocol details a surface modification strategy to drastically improve sensitivity for viral detection. [16]

Protocol:

- Surface Activation: Start with a gold nanoisland LSPR chip functionalized with carboxyl groups. Activate the surface with EDC/NHS chemistry. [16]

- Dendrimer Immobilization: Immobilize Generation 3.5 carboxylated PAMAM dendrimers (G3.5-COOH) onto the activated surface. Then, conjugate Generation 4 aminated PAMAM dendrimers (G4-NH₂) to the G3.5 layer, creating a dense, non-fouling, multi-handled template. [16]

- Aptamer Conjugation: Covalently link amino-modified aptamers (specific to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein) to the G4-NH₂ dendrimers using EDC/sulfo-NHS chemistry. This results in a high density of capturing probes. [16]

- Signal Amplification (Optional): For ultra-sensitive detection, after capturing the target (e.g., pseudo SARS-CoV-2 virus), introduce a secondary signal amplifier. Use an RCA product that hybridizes with numerous ssDNA-functionalized AuNPs (RCA-AuNPs) to bind to the captured target, massively increasing the mass and plasmonic coupling. [16]

Performance Comparison: This dendrimer-aptamer modified sensor chip demonstrated a limit of detection (LOD) of 21.9 pM for the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD, which was 152 times more sensitive than a traditional antibody-based chip. The additional RCA-AuNP amplification step improved sensitivity by another 10-fold for whole viral particles. [16]

Enhancing Signals via Nanoparticle Morphology

The shape of gold nanoparticles directly influences their fluorescence quenching efficiency and local field enhancement, which is vital for designing fluorescence-quenching LSPR assays. [18]

Experimental Comparison:

- Synthesize Different Shapes: Prepare four distinct gold nanoparticles (spheres-GNPs, nanoflowers-GNFs, nanorods-GNRs, nanotriangles-GNTs) using seed-growth methods. [18]

- Measure Quenching Efficiency: Test the ability of each nanoparticle type to quench the fluorescence of time-resolved fluorescent microspheres (TRFMs). [18]

- Theoretical Simulation: Perform Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) calculations to simulate the electric field distribution around each nanoparticle morphology. [18]

Data Table: Nanoparticle Morphology vs. Quenching Performance [18]

| Nanoparticle Morphology | Key Feature | Quenching Efficiency | Dominant Quenching Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoflowers (GNFs) | Multiple sharp tips, strong local field | 95% | Synergistic NSET & IFE (NSET dominant) |

| Gold Nanotriangles | Sharp edges | High | NSET & IFE |

| Gold Nanorods | Anisotropic, tunable LSPR | Moderate | IFE & NSET |

| Gold Nanospheres (GNPs) | Symmetric, common | Lower | Primarily IFE |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Material | Function in LSPR Signal Amplification | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanorods (Au NRs) | Tunable plasmonic nanoparticles; sensitive substrate for LSPR sensors. | Core plasmonic material in refractive index sensing. [17] |

| Mesoporous Silica Shell | Coating to protect nanoparticles, enhance stability, and finely tune refractive index sensitivity. | ~2 nm shell on Au NRs for max sensitivity (390 nm/RIU). [17] |

| PAMAM Dendrimers (G3.5-COOH, G4-NH₂) | Hyper-branched polymers for creating non-fouling surfaces and high-density ligand templates. | Immobilizing multiple aptamers for virus detection. [16] |

| Specific Aptamers | Single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotides that bind targets with high affinity and specificity. | Capturing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on sensor surface. [16] |

| Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) | Isothermal amplification technique to generate long, repetitive DNA products for signal enhancement. | Creating a scaffold to attach numerous AuNPs. [16] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Plasmonic tags for signal intensification via mass increase and plasmonic coupling. | Conjugating to RCA products for secondary amplification. [16] |

| Cetyltrimethyl Ammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant template for the synthesis and controlled silica coating of gold nanorods. | Directing the growth of uniform mesoporous silica shells. [17] |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Crosslinkers for activating carboxyl groups and covalently conjugating ligands to surfaces. | Immobilizing antibodies or aptamers on sensor chips. [16] [22] |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Innovations in Biomedicine

SERRS Immunoassays for Ultrasensitive Biomarker Detection (e.g., Tuberculosis)

Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering (SERRS) combines the significant signal enhancement of Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) with the additional intensity gains from Resonance Raman Scattering (RRS). This hybrid technique provides signal enhancements of 10⁸ to 10¹² times greater than normal Raman scattering, enabling single-molecule sensitivity for biomarker detection [24]. When the excitation laser wavelength overlaps with an electronic transition of the Raman reporter molecule and the localized surface plasmon resonance of the metallic nanostructure, this dual enhancement mechanism achieves detection limits that can surpass traditional methods like ELISA and PCR [25].

The application of SERRS immunoassays represents a transformative approach for detecting low-abundance biomarkers, particularly for infectious diseases like tuberculosis. Researchers have demonstrated that SERRS-based platforms can detect mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan (ManLAM), a key tuberculosis biomarker, at concentrations 10 times lower than conventional SERS methods, with a 40-fold increase in analytical sensitivity [24]. This exceptional sensitivity positions SERRS as a next-generation diagnostic platform capable of improving early disease detection and patient outcomes in point-of-need settings.

Technical Foundations & Signaling Pathways

SERRS immunoassays rely on a sophisticated plasmonic architecture that creates "hot spots" of dramatically enhanced electromagnetic fields. The typical assay employs a sandwich-style format with key components: a gold film functionalized with capture antibodies, a target biomarker (antigen), and antibody-conjugated gold nanoparticles coated with Raman reporter molecules [24].

The signal enhancement occurs through multiple mechanisms working synergistically. When laser excitation matches the electronic transition of the Raman reporter molecule, resonance Raman effects provide an initial 10² to 10⁶-fold enhancement. Simultaneously, the nanometric gap between the gold nanoparticle and the underlying gold film creates a coupled plasmonic system that further enhances the local electromagnetic field by approximately 10⁶ times through the lightning rod effect [24]. This hybrid enhancement creates the exceptional sensitivity that distinguishes SERRS from other spectroscopic techniques.

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and signal enhancement mechanism in a SERRS immunoassay:

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

SERRS Immunoassay Protocol for Tuberculosis Biomarker Detection

The following protocol details the specific methodology for detecting ManLAM, a tuberculosis biomarker, using SERRS immunoassay technology [24]:

1. Substrate Preparation:

- Begin with a gold film substrate thoroughly cleaned with oxygen plasma treatment

- Prepare a mixed thiolate solution containing 0.1 mM thiolated Cy5 and 1.0 mM dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) (DSP) in ethanol

- Immerse the gold substrate in the mixed thiolate solution for 2 hours at room temperature to form a self-assembled monolayer

- Rinse with ethanol and dry under nitrogen stream

- Incubate the functionalized substrate with capture antibodies (specific to ManLAM) at 10 µg/mL in phosphate buffer (pH 8.5) for 1 hour

- Block non-specific binding sites with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 minutes

2. Nanoparticle Label Preparation:

- Use 60 nm gold nanoparticles as the core material

- Incubate nanoparticles with thiolated Cy5 Raman reporter at 10 µM concentration for 30 minutes to form a monolayer coating

- Conjugate tracer antibodies to the reporter-coated nanoparticles using standard EDC-NHS chemistry

- Purify the functionalized nanoparticles (extrinsic Raman labels, ERLs) by centrifugation at 10,000g for 15 minutes

3. Assay Procedure:

- Apply clinical samples (serum or urine) to the antibody-functionalized substrate and incubate for 60 minutes at 37°C

- Wash three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST)

- Incubate with ERLs for 45 minutes at 37°C to label captured antigens

- Wash three times with PBST to remove unbound nanoparticles

- Air dry the substrate and acquire SERRS spectra using a 633 nm HeNe laser excitation source

4. Spectral Acquisition Parameters:

- Laser power: <1 mW (to prevent sample damage) [26]

- Integration time: 3-10 seconds

- Spectral range: 500-1800 cm⁻¹

- Objective magnification: 20× or 50×

- Repeat measurements at minimum three different locations per sample

Critical Optimization Steps for SERRS Enhancement

Optimal SERRS performance requires careful optimization of several parameters that directly impact signal intensity and reproducibility:

Nanoparticle Distribution and Density:

- Analyze nanoparticle distributions using atomic force microscopy (AFM)

- Target uniform distribution with approximately 35% higher densities for SERRS compared to SERS configurations

- Optimize surface functionalization to achieve approximately four orders of magnitude below closest-packed layer of 60 nm particles [24]

Buffer and Aggregation Conditions:

- For nucleic acid detection, optimize MgSO₄ concentration as a coagulant (typically 2 μL of 0.01 M solution)

- Balance aggregation to maximize "hot spot" formation without excessive precipitation

- Test different buffer systems (Tris-HCl, phosphate, acetate) for specific applications [27]

Laser Power Optimization:

- Maintain laser power below 1 mW in a diffraction-limited spot to prevent sample damage

- Calculate energy density using formula: Power/(π×(0.61×λ/NA)²)

- For 633 nm laser with 0.5 NA objective, keep energy density below 1.6×10⁵ W/cm² [26]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common SERRS Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SERRS Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | 1. Low nanoparticle capture efficiency2. Suboptimal laser power or alignment3. Raman reporter degradation4. Insufficient plasmonic coupling | 1. Verify antigen-antibody binding with control experiment2. Optimize laser focus and power (0.1-1 mW)3. Prepare fresh Raman reporter solutions4. Check gap distance (<10 nm) between nanoparticle and film | 1. Functionalize nanoparticles with fresh reagents2. Perform regular instrument calibration3. Store Raman reporters in dark at -20°C |

| High Background Signal | 1. Non-specific binding of nanoparticles2. Inadequate washing steps3. Fluorescence from impurities4. Substrate contamination | 1. Increase BSA concentration in blocking buffer (2-5%)2. Optimize wash buffer stringency (increased detergent)3. Implement photobleaching step before measurement4. Clean substrate with plasma treatment | 1. Include appropriate negative controls2. Filter all buffers before use3. Implement multiple blocking steps |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | 1. Irregular nanoparticle distribution2. Pipetting inconsistencies3. Inadequate mixing of reagents4. Variable incubation conditions | 1. Standardize functionalization protocols2. Calibrate pipettes regularly3. Implement vortexing of all reagents4. Use thermal mixer for uniform incubation | 1. Implement rigorous QC of functionalized substrates2. Train personnel on consistent technique3. Use automated liquid handling systems |

| Spectral Damage or Photo-bleaching | 1. Excessive laser power2. Prolonged exposure time3. Heat buildup in metallic structures4. Chemical degradation of reporter | 1. Reduce laser power to minimum detectable level2. Implement multiple short acquisitions3. Perform measurements in aqueous environment4. Test reporter stability under illumination | 1. Establish power curves for each new system2. Use lower NA objectives for reduced energy density3. Incorporate antioxidant in preparation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of SERRS over conventional SERS for biomarker detection?

SERRS provides significantly stronger signal amplification by coupling the ~10⁶ enhancement of SERS with additional 10²-10⁶ enhancement from resonance Raman scattering. This combined effect enables SERRS to achieve detection limits that can rival fluorescence methods while maintaining the sharp spectral features and molecular specificity of Raman spectroscopy. Additionally, SERRS exhibits reduced photobleaching, minimal background fluorescence with red excitation, and superior multiplexing capabilities due to narrower spectral bandwidths [24] [25].

Q2: How does the SERRS immunoassay design differ from traditional ELISA?

While both use sandwich-style formats, SERRS replaces enzymatic amplification with plasmonic enhancement. The key differences include: (1) SERRS uses a gold capture substrate instead of plastic wells, (2) SERRS employs gold nanoparticles coated with Raman reporters instead of enzyme-conjugated detection antibodies, and (3) SERRS detection relies on spectroscopic readout rather than colorimetric or chemiluminescent signals. These differences eliminate the time and temperature requirements for enzymatic substrate turnover, significantly reducing assay time while improving sensitivity [24] [25].

Q3: What causes variations in SERRS signal intensity between experiments, and how can we improve reproducibility?

The main factors affecting reproducibility include nanoparticle distribution density, aggregation state, laser power stability, and molecular orientation on metallic surfaces. To improve reproducibility: (1) Standardize nanoparticle functionalization protocols with quality control checks, (2) Optimize and consistently maintain aggregation conditions using MgSO₄ concentration curves, (3) Regularly calibrate laser power and alignment, (4) Implement internal standards for signal normalization, and (5) Use experimental design (DoE) approaches to identify critical factors [27] [28].

Q4: Why is thiolated-Cy5 particularly effective as a Raman reporter in SERRS applications?

Thiolated-Cy5 provides three significant advantages: (1) The thiol group enables strong, specific immobilization to gold surfaces through Au-S bonding, creating stable and reproducible molecular orientation, (2) When adsorbed on gold, Cy5's fluorescence is efficiently quenched, eliminating background fluorescence that could interfere with Raman detection, and (3) The absorption maximum of Cy5 at 649 nm aligns well with common 633 nm HeNe lasers, enabling optimal resonance enhancement [25].

Q5: What considerations are essential for adapting SERRS platforms to point-of-need diagnostic settings?

Key considerations for point-of-need deployment include: (1) Developing rugged, portable Raman spectrometers with battery operation, (2) Stabilizing reagents through lyophilization to break cold-chain requirements, (3) Simplifying sample preparation protocols for non-laboratory settings, (4) Implementing user-friendly software with automated data analysis, and (5) Establishing comprehensive training programs for safe operation including laser safety and sample handling procedures [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SERRS Immunoassay Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Nanostructures | 60 nm spherical gold nanoparticles; Gold film substrates (50-100 nm thickness) | Provide plasmonic enhancement through localized surface plasmon resonance | Size uniformity (PDI <0.2) critical for reproducible enhancement; Characterize by UV-Vis and TEM |

| Raman Reporters | Thiolated Cy5; Thiolated Rhodamine derivatives; Benzotriazole compounds | Generate characteristic Raman signatures; Resonance enhancement when laser matched to electronic transition | Select reporters with high Raman cross-sections; Thiolation enables stable gold attachment |

| Surface Functionalization | Dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) (DSP); Carboxyl-PEG-Thiol; NHS-EDC chemistry | Facilitate antibody immobilization with proper orientation; Control surface density | Mixed monolayers optimize bioactivity; Characterize by electrochemical methods |

| Biological Recognition Elements | Anti-ManLAM antibodies (for TB); CA 19-9 antibodies (pancreatic cancer) | Provide molecular specificity for target biomarkers | Validate affinity and specificity; Screen multiple clones for optimal performance |

| Aggregation Agents | MgSO₄ (0.01 M); HCl (0.3-0.7 M); Poly-L-lysine | Promote nanoparticle aggregation to create "hot spots" for enhanced signals | Titrate concentration carefully; Excess causes precipitation; Monitor by color change |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (1-5%); Casein; Fish skin gelatin | Reduce non-specific binding to improve signal-to-noise ratio | Test multiple blockers; Consider commercial blocker cocktails for complex samples |

Performance Optimization & Data Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

SERRS immunoassays demonstrate exceptional performance characteristics compared to conventional detection methods:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of SERRS vs. Other Detection Methods

| Analyte | Detection Method | Limit of Detection | Linear Range | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ManLAM (TB biomarker) | SERRS Immunoassay | 10× lower than SERS [24] | 1-50 ng/mL | 40× increase in analytical sensitivity vs. SERS |

| MMP-7 (Pancreatic cancer) | SERRS Immunoassay | 2.3 pg/mL [25] | Not specified | 14× improvement vs. ELISA (31.8 pg/mL) |

| CA 19-9 (Pancreatic cancer) | SERRS Immunoassay | 34.5 pg/mL [25] | Not specified | 29× improvement vs. ELISA (987 pg/mL) |

| Single-stranded DNA | SERS with MgSO₄ aggregation | Dependent on buffer optimization [27] | Linear with 1656/1099 cm⁻¹ peak ratio | Enables study of aptamer-toxin interactions |

Data Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in optimizing SERRS experiments and troubleshooting performance issues:

SERRS immunoassay technology represents a significant advancement in ultrasensitive biomarker detection, with demonstrated applications in tuberculosis diagnosis and cancer biomarker detection. The exceptional sensitivity and specificity achieved through the combination of plasmonic enhancement and resonance Raman effects position this technology as a powerful tool for researchers and clinical laboratories.

Future development efforts are focusing on several key areas: (1) Integration with vertical flow assay formats to reduce analysis time, (2) Implementation of robust multiplexing capabilities for parallel biomarker detection, (3) Development of field-deployable instrumentation for point-of-need testing, and (4) Creation of standardized reagent systems to improve inter-laboratory reproducibility [25]. As these advancements mature, SERRS-based platforms are poised to transform diagnostic paradigms across multiple disease areas, particularly in resource-limited settings where sensitivity, speed, and cost-effectiveness are paramount considerations.

Label-free vs. Label-based SERS Strategies for Virus and Pathogen Identification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between label-free and label-based SERS detection?

A1: The core difference lies in the source of the detected Raman signal.

- Label-free SERS directly captures the intrinsic Raman scattering signals generated by the pathogen's own molecular components (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids in a virus capsid) when they are adsorbed onto or near the SERS-active substrate [29] [30]. This method avoids complex labeling steps and provides the pathogen's unique "fingerprint" [31].

- Label-based SERS relies on detecting a strong, consistent signal from a dedicated Raman reporter molecule (e.g., 4-aminothiophenol) that is attached to a plasmonic nanoparticle (like a gold nanostar) [32]. These SERS tags are then linked to the pathogen via a specific recognition element (like an antibody or aptamer). The signal comes from the reporter, not the pathogen itself, which allows for indirect, highly sensitive detection [29].

Q2: When should I choose a label-free strategy over a label-based one for my pathogen detection experiment?

A2: The choice depends on your experimental goals, sample type, and required throughput. The following table summarizes the key considerations:

| Factor | Label-Free SERS | Label-Based SERS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Pathogen fingerprinting, discovery of unknown spectral features, rapid classification [29] [31]. | Highly sensitive and specific quantification of a known target pathogen [29] [32]. |

| Sensitivity | Generally lower; limited by the intrinsic Raman cross-section of the pathogen [29]. | Very high (can reach single-molecule level); signal is amplified by the reporter molecule [29] [33]. |

| Specificity | Relies on spectral analysis and machine learning for identification; can be affected by background interference [29] [30]. | High, conferred by the biological recognition element (antibody, aptamer) [32]. |

| Sample Preparation | Simpler and faster; often involves mixing the sample with a colloidal substrate [29] [30]. | More complex; requires synthesis of SERS tags and multiple incubation/washing steps [29]. |

| Multiplexing Potential | Challenging due to overlapping spectral fingerprints. | Excellent; different reporters with distinct Raman spectra can be used for different targets [29]. |

| Best for | Rapid screening, identification of unknown pathogens, and studies where preserving the native state of the pathogen is crucial. | Ultrasensitive detection of a specific pathogen in complex matrices, clinical diagnostics, and quantitative assays [32] [33]. |

Q3: I am getting poor and inconsistent signals in my label-free SERS experiments with viruses. What could be the issue?

A3: Inconsistent signals in label-free SERS are a common challenge, often stemming from these factors:

- Substrate Inhomogeneity: The distribution and density of "hotspots" on your SERS substrate are critical. Non-uniform substrates lead to variable signal enhancement [29] [34]. Ensure reproducible fabrication of your nanoparticles or solid substrates.

- Inefficient Pathogen Capture: Viruses may not be consistently driven into the enhanced electromagnetic fields. Employing specific capture methods, such as functionalizing the substrate with antibodies or aptamers, can help concentrate pathogens at the hotspots [29].

- Background Interference: Complex biological samples (like serum or saliva) contain proteins and other molecules that can adsorb to the substrate and swamp the weak viral signal [30] [33]. Optimization of sample pre-treatment (e.g., dilution, filtration) or using substrates with pre-concentration capabilities (like flexible swabs) can mitigate this [34].

- Laser-Induced Damage: Using excessive laser power can denature the viral proteins, altering their Raman fingerprint. Always use the minimum laser power required to obtain a measurable signal.

Q4: How can I improve the stability and reproducibility of my label-based SERS probes?

A4: Focus on the synthesis and functionalization of the plasmonic nanoparticles:

- Controlled Synthesis: Standardize your nanoparticle synthesis protocol (e.g., seed-mediated growth for nanorods or nanostars) to ensure consistent size, shape, and plasmonic properties [32].

- Stable Raman Reporter: Choose a reporter molecule that forms a stable, dense monolayer on the metal surface (e.g., thiolated compounds on gold) to prevent leaching and ensure a stable signal [32].

- Effective Passivation: After attaching the reporter and recognition element, passivate the remaining metal surface with an inert molecule like polyethylene glycol (PEG). This reduces non-specific binding and improves colloidal stability in complex fluids [32].

- Quality Control: Implement characterization techniques like UV-Vis spectroscopy, TEM, and SERS mapping to verify the uniformity of your SERS probes before use in detection assays [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Label-Free Viral Detection

Problem: The Raman signal from the virus is weak and obscured by background fluorescence or noise.

Solutions:

- Optimize the "Hotspot" Generation: For colloidal substrates, induce controlled aggregation of nanoparticles (e.g., using salts or adjusting pH) to create more inter-particle gaps where the field enhancement is strongest. One protocol uses sodium borohydride-reduced silver nanoparticles mixed with acetonitrile and the virus sample to form optimal hotspots for virus detection [30].

- Employ Advanced Substrates: Switch from simple spherical nanoparticles to nanostructures with high field enhancement at their tips, such as gold nanostars [32] or nano-urchins. Alternatively, use flexible SERS substrates (e.g., polymer-based or cellulose) that can conform to the pathogen's surface, improving contact and signal reproducibility [34].

- Leverage Data Analysis: Apply machine learning algorithms like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to differentiate the subtle spectral features of the pathogen from the complex background of clinical samples like serum or saliva [30] [33].

Issue: High Non-Specific Binding in Label-Based Sandwich Assays

Problem: The SERS tag binds to surfaces or molecules other than the target pathogen, leading to false positives.

Solutions:

- Optimize the Blocking Step: Incubate your capture substrate (e.g., antibody-coated slide or MIP electrode) with a high-concentration blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein, or commercial blocking buffers) before introducing the sample. This saturates non-specific binding sites.

- Refine Washing Stringency: Increase the number of washes and incorporate mild detergents (e.g., Tween-20) in the wash buffer to remove loosely bound SERS tags without disrupting specific antigen-antibody interactions.

- Use a Biomimetic Capture Layer: Replace or supplement antibodies with Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs). MIPs, known as "plastic antibodies," offer highly specific binding cavities for the target with superior chemical stability, reducing non-specific interactions [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents for SERS-based Pathogen Detection

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanostars (AuNSs) | Plasmonic nanoparticle with sharp tips that act as intense SERS hotspots; highly tunable LSPR [32]. | Used as the core for label-based SERS tags due to their high enhancement factor. |

| Silver Nanoparticles (Ag NPs) | Provides extremely high electromagnetic enhancement, often higher than gold, but can be less stable [30]. | Used in label-free detection, often aggregated to create hotspots for viral fingerprinting. |

| 4-Aminothiophenol (4-ATP) | A common Raman reporter molecule; forms a stable monolayer on gold/silver via the thiol group [32]. | The signal source in a label-based SERS probe; its distinct peaks are monitored for quantification. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | A synthetic polymer with cavities complementary to a target molecule, serving as a stable, artificial antibody [32]. | Used as a capture layer on the SERS substrate to specifically isolate the target pathogen from a sample. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A capping agent and stabilizer that controls nanoparticle growth and prevents aggregation in solution [32]. | Used during the synthesis of anisotropic nanoparticles like gold nanostars to control their shape and stability. |

| Flexible PDMS Substrate | A transparent, deformable polymer that can be coated with metal nanoparticles to create a versatile SERS substrate [34]. | Used for in-situ sampling on irregular surfaces (e.g., fruit skin) or integrated into microfluidic devices. |

Experimental Protocol: Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Label-Free Detection of Virus using Ag Nanoparticles

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating the detection of Monkeypox virus in serum [30].

Workflow:

Detailed Steps:

- Substrate Preparation: Add 5 mL of silver nitrate solution (6.6 mg/mL) to 500 mL of vigorously stirred sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) solution (0.135 mg/mL). Stir for 18 minutes. Centrifuge the resulting silver sol at 5500 rpm for 20 minutes at 25°C. Remove the supernatant and redisperse the pellet to concentrate the Ag nanoparticles (Ag@BO) [30].

- Sample Mixing: Combine 7 µL of the concentrated Ag@BO sol with 1 µL of acetonitrile. Then, add 5 µL of the virus sample (e.g., inactivated virus in serum) and 9 µL of 0.05 M NaBH₄ (pH=10). The NaBH₄ acts as an aggregating agent to form viral "hotspots" [30].

- Incubation: Mix the solution thoroughly and allow it to incubate for a few minutes to facilitate aggregation and the entrapment of viruses in the enhanced field regions.

- SERS Measurement: Deposit the mixture onto a slide or well plate. Acquire SERS spectra using a Raman spectrometer (e.g., 532 nm laser, 30 mW power, 30 s acquisition time). The entire detection process can be completed within 5 minutes [30].

- Data Analysis: Process all acquired spectra (e.g., baseline correction). Use multivariate analysis like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the 700-1500 cm⁻¹ spectral region to clearly identify and differentiate the virus based on its spectral fingerprint, even in a complex biological background [30].

Protocol 2: Label-Based Detection using SERS Nanotags and a MIP Capture Layer

This protocol is inspired by a biosensor developed for the breast cancer biomarker CA 15-3, demonstrating the principles of a sandwich assay applicable to pathogens [32].

Workflow:

Detailed Steps:

- Capture Substrate Fabrication (MIP): Electropolymerize a monomer (e.g., aniline) on a gold electrode in the presence of the target pathogen (template). This creates a polymer matrix with specific molecular cavities. Extract the template pathogen using a surfactant like Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), leaving behind complementary binding sites in the MIP layer [32].

- SERS Nanotag Preparation:

- Synthesize gold nanostars (AuNSs) via a seed-mediated or surfactant-directed method.

- Incubate the AuNSs with a Raman reporter molecule (e.g., 4-ATP) to form a self-assembled monolayer.

- Passivate the surface with a short PEG molecule.

- Conjugate a specific recognition element (e.g., antibody against the target pathogen) to the PEGylated surface [32].

- Sandwich Assay Execution:

- Capture: Incubate the prepared MIP sensor with the sample containing the pathogen. The pathogen is selectively captured into the imprinted cavities.

- Binding: After washing, incubate the sensor with the SERS nanotags. The antibodies on the nanotags bind to the captured pathogen, forming a "MIP-pathogen-nanotag" sandwich structure.

- Washing: Perform stringent washing to remove any unbound SERS nanotags, which is critical for minimizing background signal.

- Signal Detection: Dry the sensor and acquire SERS spectra from the surface. The intensity of the characteristic peaks of the Raman reporter (e.g., 4-ATP) is directly correlated with the concentration of the captured pathogen [32].

SPR Biosensor Design for Real-Time Biomolecular Interaction Analysis

Troubleshooting Guide: Common SPR Experimental Issues

This guide addresses frequent challenges encountered during Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments to optimize signal detection in surface spectroscopy research.

Q1: My baseline is unstable or drifting. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

A drifting baseline is a common issue often related to the fluidic system or buffer conditions.

- Solution: Ensure your running buffer is properly degassed to eliminate air bubbles, which can cause significant signal fluctuations [21]. Check the entire fluidic system for any leaks that might introduce air [21]. Always use fresh, filtered buffer to avoid particulate contamination, and allow sufficient time for temperature stabilization before starting experiments [21].

Q2: I observe no significant signal change upon analyte injection, despite expecting binding. What should I investigate?

A lack of expected signal can stem from several methodological or preparation issues.

- Solution: First, verify that your analyte concentration is appropriate (typically 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value) and that the ligand was successfully immobilized [21] [20]. Confirm the biological activity and integrity of both interaction partners, as inactive proteins will not bind [21] [35]. Ensure your running buffer is compatible and does not inhibit the interaction.

Q3: High levels of non-specific binding are obscuring my specific signal. How can I reduce this?

Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when analytes interact with the sensor surface rather than the specific ligand.

- Solution: Implement surface blocking with agents like BSA or casein to occupy non-specific sites [21] [19]. Optimize your running buffer by adding non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween-20) to reduce hydrophobic interactions, or increase salt concentration to shield charge-based interactions [35] [20]. Consider switching to a sensor chip with different surface chemistry that is less prone to NSB for your specific analyte [20].

Q4: The regeneration step does not completely remove bound analyte, causing carryover between cycles. How can I optimize regeneration?

Incomplete regeneration leads to decreasing ligand activity over time and inaccurate data.

- Solution: Systematically scout for optimal regeneration conditions by testing different pH, ionic strength, and buffer compositions [21]. Start with mild conditions (e.g., mild acid or base) and progressively increase stringency until complete analyte removal is achieved without damaging the ligand [20]. Increase regeneration flow rates (100-150 µL/min) and consider multiple short injections rather than one long injection [20].

Q5: My sensorgram suggests mass transport limitations. How do I confirm and address this?

Mass transport limitation occurs when analyte diffusion to the surface is slower than the association rate.

- Solution: To identify, run the assay at different flow rates. If the observed association rate (ka) increases with higher flow rates, mass transport is limiting [20]. To address, increase the flow rate, reduce ligand density, or use a higher analyte concentration [21] [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key considerations when selecting which binding partner to immobilize as the ligand? A: Choose the smaller molecule as the ligand to maximize the response signal, as SPR response is mass-based [20]. Prefer the partner with higher purity if using covalent coupling, and utilize tagged molecules (e.g., His-tag, biotin) for controlled orientation and higher activity [20]. Avoid using multivalent analytes as ligands, as they can cause avidity effects [20].

Q: How many analyte concentrations should I use for kinetic analysis, and what range is appropriate? A: Use a minimum of 3, but ideally 5 different analyte concentrations spanning from 0.1 to 10 times the expected KD value to ensure well-distributed binding curves [20]. If the KD is unknown, start with a low nM concentration series and adjust until a binding response is observed [20].

Q: How can I minimize bulk refractive index effects (bulk shift) in my experiments? A: Bulk shift appears as a square-shaped signal at injection start/end and is caused by differences between the analyte buffer and running buffer [20]. Match the composition of your analyte sample buffer to the running buffer as closely as possible, using dialysis or buffer exchange if necessary [20]. For components that cannot be matched (e.g., DMSO, glycerol), use reference subtraction, though this may not fully correct for large mismatches [20].

Q: What are the signs of an inadequate regeneration procedure, and how can I develop an effective one? A: Signs include progressively decreasing maximum response (Rmax) over cycles, drifting baseline, or curved baselines post-regeneration [20]. Develop a protocol by scouting different solutions (acidic, basic, high salt, with/without additives) starting with mild conditions and monitoring ligand activity after each regeneration [20]. Always include a positive control to verify ligand functionality remains intact [20].

Advanced Optimization Methodologies

Signal Enhancement Protocols

Nanomaterial-Based Signal Amplification: Incorporating nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles, graphene, or transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) can significantly enhance sensitivity [36]. These materials increase the local refractive index change and can provide additional binding sites, improving the detection limit for low-abundance analytes [37] [36].

Algorithm-Assisted Sensor Optimization: Recent advances employ multi-objective optimization algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to simultaneously optimize multiple design parameters (incident angle, metal layer thickness) and performance metrics (sensitivity, figure of merit) [37]. This approach has demonstrated improvements of 230.22% in bulk refractive index sensitivity and enables detection limits as low as 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) for model systems like mouse IgG [37].

Experimental Parameters for Quantitative Analysis

Table 1: Recommended Analyte Concentration Ranges for Kinetic Analysis

| Expected KD | Concentration Range | Number of Concentrations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown | 1 nM - 10 µM | 5-8 | Start with logarithmic dilution series |

| Low (pM-nM) | 0.1x to 10x KD | 5 | Use higher flow rates to minimize mass transport |

| High (µM-mM) | 0.5x to 5x KD | 3-5 | May require higher immobilization levels |

Table 2: Common Regeneration Solutions for Different Interaction Types

| Interaction Type | Regeneration Solution | Contact Time | Precautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein A/G - IgG | 10 mM Glycine, pH 1.5-2.5 | 15-30 seconds | Neutralize immediately after regeneration |

| Biotin-Streptavidin | 1-10 mM HCl or 1-5 mM NaOH | 30-60 seconds | Monitor streptavidin activity over cycles |

| His-tag - NTA | 350 mM EDTA, 10-300 mM Imidazole | 30-120 seconds | Requires re-charging with Ni²⁺ after regeneration |

| High Affinity Protein-Protein | 1-4 M MgCl₂, 10-100 mM HCl | 30-60 seconds | Test ligand activity carefully after each regeneration |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SPR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Carboxylated dextran matrix for covalent immobilization | Versatile for amine, thiol, or carbonyl coupling |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Captures His-tagged proteins via nickel chelation | Requires conditioning with Ni²⁺; gentle regeneration |

| Streptavidin Sensor Chip | Captures biotinylated ligands | Very stable surface; harsh regeneration possible |

| HBS-EP Buffer | Standard running buffer (HEPES + NaCl + EDTA + Surfactant) | Low non-specific binding; compatible with most proteins |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | Activates carboxyl groups for amine coupling | Standard for covalent immobilization; fresh preparation required |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Blocks remaining activated groups after coupling | Prevents non-specific binding |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-3.0) | Common regeneration solution | Effective for many antibody-antigen interactions |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

Machine Learning and Convolutional Neural Networks for Spectral Analysis and Pathogen Differentiation