Navigating Data Interpretation Challenges in Surface Chemical Analysis: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Surface chemical analysis provides critical data for drug development, materials characterization, and biomedical device validation.

Navigating Data Interpretation Challenges in Surface Chemical Analysis: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Surface chemical analysis provides critical data for drug development, materials characterization, and biomedical device validation. However, researchers face significant challenges in accurately interpreting this complex data, from methodological artifacts to analytical pitfalls. This article offers a comprehensive guide for scientists and drug development professionals, covering foundational principles, key analytical techniques like XPS and AES, common troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks. By addressing these interpretation challenges, the article aims to enhance data reliability, improve analytical outcomes, and accelerate innovation in biomedical research and development.

Understanding Surface Analysis: Core Principles and Common Pitfalls

Surface chemical analysis is a branch of analytical chemistry that studies the composition, structure, and energy state of the outermost layers of a solid material—the region that interacts directly with its environment [1]. This field is dedicated to answering fundamental questions of 'what is it?' and 'how much?' exists at material interfaces, providing critical insights for applications ranging from drug development to semiconductor manufacturing [2] [3].

Core Concepts of Surface Analysis

What Constitutes a "Surface"?

In surface science, the "surface" is defined as that region of a solid that differs from its bulk composition and structure. This includes:

- Native Surfaces: Nominally pure solids where a surface layer has formed through environmental interaction (e.g., aluminum foil with an oxide layer) [1].

- Engineered Surfaces: Solids where a separate layer has been intentionally created (e.g., catalysts with reactive species deposited on a support material) [1].

- Operational Thickness: The thickness of interest varies by application—from less than 1 nm for catalysts to over 100 nm for corrosion studies [1].

Fundamental Principles

Surface analysis techniques generally follow a "beam in, beam out" mechanism where a primary beam of photons, electrons, or ions impinges on a material, and a secondary beam carrying surface information is analyzed [1]. The sampling depth varies significantly with the probe type, making certain techniques more surface-sensitive than others.

Table: Sampling Depths of Different Probe Particles

| Particle Type | Energy | Sampling Depth |

|---|---|---|

| Photons | 1 keV | ~1,000 nm |

| Electrons | 1 keV | ~2 nm |

| Ions | 1 keV | ~1 nm |

Essential Surface Analysis Techniques

Researchers employ various techniques to characterize surfaces, each with unique strengths for answering "what" and "how much" questions.

Primary Techniques

Three techniques have achieved widespread application for surface chemical analysis [4]:

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS/ESCA): Uses X-rays to eject photoelectrons, providing quantitative information about elemental composition and chemical bonding states [2] [3]. It is the most widely used surface analysis technique due to its relatively straightforward quantification and rich chemical state information [4] [2].

- Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES): Employs a focused electron beam to excite Auger electrons, enabling high-spatial-resolution elemental analysis and chemical mapping [3] [5].

- Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS): Uses focused primary ions to sputter secondary ions from the surface, offering extremely high sensitivity for elemental and molecular analysis, including isotope detection [4] [5].

Table: Comparison of Major Surface Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Primary Probe | Detected Signal | Key Information | Detection Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPS/ESCA | X-rays | Photoelectrons | Elemental composition, chemical state, quantitative analysis | All elements except H and He [4] [5] |

| AES | Electrons | Auger electrons | Elemental composition, high-resolution mapping | Does not directly detect H and He [4] |

| SIMS | Ions | Secondary ions | Trace elements, isotopes, molecular structure | All elements, including isotopes [4] |

| SPR | Light (photons) | Reflected light | Binding kinetics, affinity constants, "dry" mass | Mass change at surface (non-specific) [2] |

| QCM-D | Acoustic waves | Frequency/Dissipation | Mass uptake, viscoelastic properties, "wet" mass | Mass change including hydrodynamically coupled water [2] |

Emerging and Specialized Methods

The field continues to evolve with techniques that address specific challenges:

- Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES): Uses higher-energy X-rays to probe deeper layers and buried interfaces, now available in laboratory instruments [4].

- Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS): Allows analysis of surfaces in reactive environments rather than requiring ultra-high vacuum, enabling studies of corrosion and biological systems under more realistic conditions [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

General Surface Analysis Issues

Problem: Inconsistent results between replicate experiments

- Solutions: Standardize immobilization procedures; use consistent sample handling techniques; verify ligand stability over time; ensure proper instrument calibration; check sample state (complete dissolution, precipitation) [6].

Problem: Unexpected or uninterpretable spectral data

- Solutions: For XPS, ensure correct peak fitting using appropriate line shapes and constraints; check for confirming peaks and relative intensities; validate reference binding energies [4]. For SIMS, consider matrix effects and fragmentation patterns.

Specific Technique Challenges

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Troubleshooting [6]:

- Baseline Drift: Ensure proper buffer degassing; check for fluidic system leaks; use fresh buffer solutions; optimize flow rate and temperature settings.

- No Signal Change: Verify analyte concentration appropriateness; check ligand immobilization level; confirm ligand-analyte compatibility; evaluate sensor surface quality.

- Non-Specific Binding: Block sensor surface with suitable agents (e.g., BSA); optimize regeneration steps; consider alternative immobilization strategies; modify running buffer.

QCM-D Interpretation Challenges [2]:

- Viscoelastic Films: For dissipation changes >5%, use Voigt or Maxwell models instead of the Sauerbrey relationship, which only applies to rigidly attached masses.

- Hydration Effects: Remember QCM-D measures "wet" mass (protein + water), while SPR measures "dry" mass, explaining common discrepancies between techniques.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is surface analysis so important for drug development and biomedical devices? Surface analysis provides critical information about how proteins interact with material surfaces, affecting device performance, biosensor sensitivity, and biological responses. Understanding protein orientation, conformation, and concentration on surfaces enables structure-based design rather than trial-and-error approaches [2].

Q2: What is the most significant data interpretation challenge in XPS analysis? Peak fitting remains particularly challenging, with approximately 40% of published papers showing incorrect fitting. Common errors include using symmetrical peaks for inherently asymmetrical metal peaks, applying constraints incorrectly, and not justifying parameter choices [4].

Q3: Can surface analysis techniques detect hydrogen and helium? Most electron spectroscopy techniques (XPS and AES) cannot directly detect hydrogen and helium, though the effect of hydrogen on other elements can sometimes be observed. SIMS can detect all elements, including isotopes, making it unique for hydrogen detection [4].

Q4: How do I choose between XPS, AES, and SIMS for my application?

- Use XPS for quantitative composition and chemical state information, especially when analyzing both organic and inorganic materials.

- Choose AES for high-spatial-resolution mapping of metals and semiconductors.

- Select SIMS for ultra-high sensitivity elemental and molecular analysis, including isotope tracing [3].

Q5: What advancements are addressing current limitations in surface analysis? Emerging approaches include HAXPES for buried interfaces, NAP-XPS for reactive environments, improved data processing software, multi-technique analysis combining experimental and computational methods, and standardized data interpretation protocols [4] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials and Reagents for Surface Analysis Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Degassed Buffer Solutions | Running buffer for SPR and QCM-D to prevent bubble formation [6] |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Ethanolamine) | Reduce non-specific binding in biosensing experiments [6] |

| Radiolabeled Proteins (¹²⁵I, ¹³¹I) | Quantitative measurement of protein adsorption in radiolabeling studies [2] |

| Regeneration Buffers | Remove bound analyte from sensor surfaces between experimental runs [6] |

| Ultra-High Purity Gases | Sputtering sources for depth profiling and surface cleaning [1] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and quantitative analysis validation |

Experimental Workflow for Protein Surface Characterization

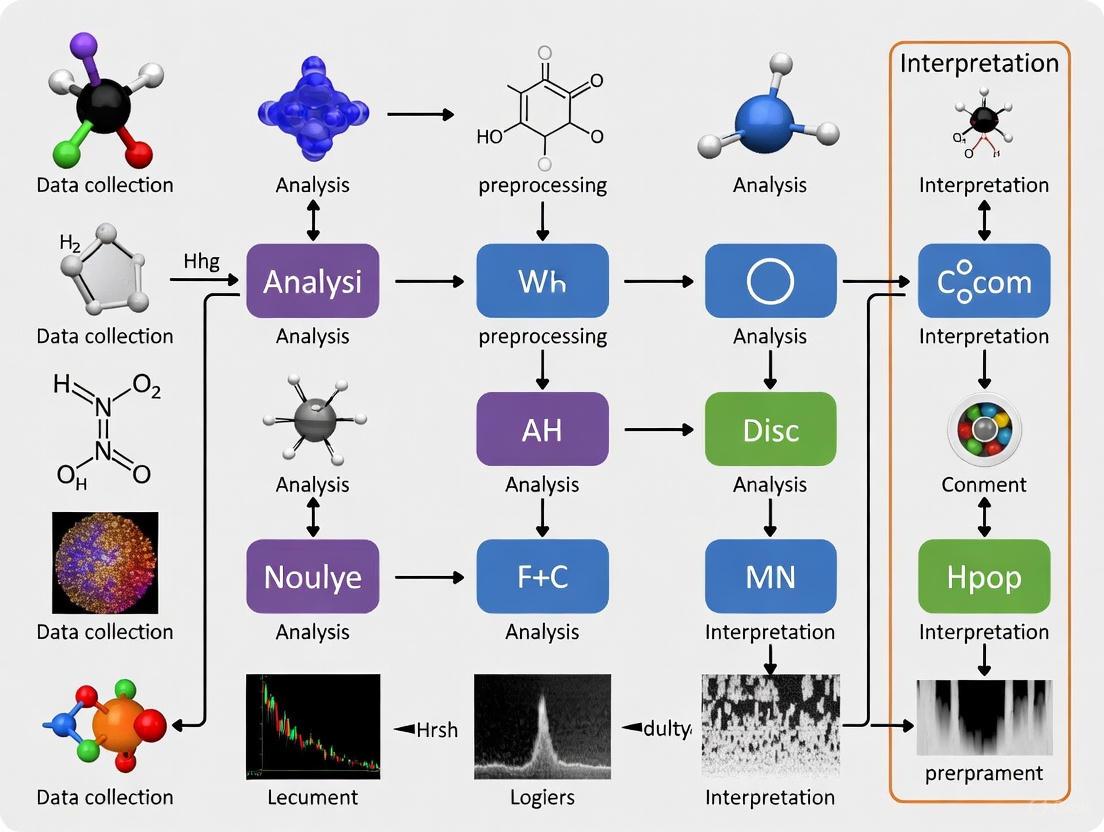

The following diagram illustrates a multi-technique approach for characterizing proteins on surfaces, essential for addressing data interpretation challenges in biological interface research:

This multi-technique methodology addresses the fundamental thesis that no single technique can provide complete structural information about surface-bound proteins, requiring both experimental and computational approaches for comprehensive characterization [2].

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why do I get different surface roughness measurements on the same sample when using the same profilometer? This is often caused by a lack of thermal stabilization of the instrument. Internal heat sources from engines and control electronics cause thermal expansion of the drive mechanism. If measurements are started before the device is fully stabilized, it can lead to significant synchronization errors of individual profile paths (e.g., 16.1 µm). It is recommended to allow for a thermal stabilization time of 6–12 hours after turning on the device [7].

FAQ 2: My surface defect analysis sometimes identifies problems that later turn out to be artifacts. How can I avoid this? Misinterpreting artifacts for real defects is a common pitfall. This can be caused by improper sample preparation or imaging artifacts. To avoid this, do not rely on a single inspection method. Cross-validate your findings using complementary techniques like SEM, AFM, and EDS to confirm the nature of a suspected defect [8].

FAQ 3: Besides thermal factors, what other instrument-related issues can affect my surface analysis data? Changes in the instrument's center of gravity during operation can be a significant factor. The movement of the measurement probe can shift the center of gravity, affecting the overall rigidity of the profilometer structure and the leveling of the tested surface. One study found a structural vulnerability of 0.8 µm over a 25 mm measurement section due to this effect [7].

FAQ 4: How can I be sure that a defect on one part of a surface is representative of the whole sample? Assuming uniformity across a surface is a common interpretation error. A defect that appears in one area might behave differently elsewhere. A robust analysis involves multiple measurements across different regions of the sample to understand the variability and not underestimate the material's overall reliability [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Spatial Measurements with Contact Profilometry Potential Cause: Thermal instability of the instrument and mechanical susceptibility. Solution:

- Thermal Stabilization: Allow the profilometer to stabilize thermally after powering on. The required time should be determined for your specific device but can be 6–12 hours. Using thermographic studies can help map thermal fields and identify stabilization time [7].

- Stabilize Ambient Conditions: Conduct measurements in a temperature-controlled environment. Even a 1°C change in ambient temperature can lead to noticeable errors in amplitude parameters [7].

- Check Mechanical Rigidity: Be aware that the movement of the measuring arm can affect the system's center of gravity. Follow manufacturer guidelines for setup to minimize this structural vulnerability [7].

Problem: Misidentification of Surface Defects Potential Cause: Over-reliance on a single analysis technique, leading to confusion between real defects and preparation artifacts. Solution:

- Cross-Validation: Employ a multi-technique approach. Use complementary methods like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) to validate findings and identify root causes [8].

- Review Sample Preparation: Scrutinize your sample preparation protocol. Improper techniques can introduce artifacts that mimic real surface failures [8].

- Use Enhanced Imaging: Utilize advanced imaging techniques that offer higher resolution and 3D mapping for a more thorough examination of surface features [8].

The table below summarizes major error sources and their impacts as identified in research.

| Error Factor | Observed Impact | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Instability [7] | Synchronization error of 16.1 µm before stabilization | Thermal stabilization for 6-12 hours after power-on |

| Ambient Temperature Change [7] | Noticeable errors in amplitude parameters with a 1 °C change | Perform measurements in a climate-controlled lab |

| Structural Vulnerability [7] | Displacement of 0.8 µm over a 25 mm section | Understand instrument limits; ensure proper leveling |

Experimental Protocol for Validating Surface Analysis Results

To ensure accurate interpretation and minimize errors, the following validation protocol is recommended.

Objective: To confirm that observed surface features are genuine material defects and not measurement artifacts. Materials:

- Primary surface analysis instrument (e.g., Stylus Profilometer, XPS, AFM)

- Sample of interest

- Tools for complementary analysis (e.g., SEM, EDS)

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Power on your primary instrument and allow it to stabilize for the recommended time (e.g., 6-12 hours for a contact profilometer) to reach thermal equilibrium [7].

- Initial Measurement: Perform the surface analysis on the area of interest using your standard parameters.

- Re-measurement: Repeat the analysis on the same area or a symmetrically equivalent area to check for reproducibility.

- Cross-Technique Validation: Analyze the same sample, focusing on the region with the suspected defect, using a complementary technique. For example:

- Data Correlation: Correlate the data from all techniques. A true defect will have consistent characteristics across multiple methods, while an artifact will likely only appear in one.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential items for conducting reliable surface analysis.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Contact Profilometer | A device with a diamond stylus that moves across a surface to record vertical deviations and measure topography [7]. |

| Thermal Chamber / Controlled Lab | Provides a stable temperature environment to minimize thermal expansion errors in the instrument and sample [7]. |

| Laser Interferometer | A high-precision tool used to diagnose mechanical stability and positioning errors of profilometer components [7]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Provides high-resolution images of surface morphology, useful for validating defects observed with other techniques [8]. |

| Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | Maps surface topography with extremely high resolution by scanning a sharp tip over the surface, useful for nano-scale defect confirmation [8]. |

| Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) | An accessory often paired with SEM that identifies the elemental composition of surface features, helping to determine the nature of a defect [8]. |

Workflow for Robust Surface Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow to minimize interpretation errors, incorporating cross-validation and checks for common pitfalls.

Troubleshooting Guides

Inaccurate Surface Roughness Measurements

Problem: Measurements from your surface roughness tester do not match reference values or expected results, indicating a potential accuracy issue.

Explanation: Accuracy refers to the closeness of a measured value to the true or accepted value. In surface measurement, this can be compromised by various factors including improper calibration, instrument drift, or sample preparation artifacts. For example, if a standard sample is known to have a roughness of 100 μm, an accurate analytical method should consistently yield a result very close to that value [9].

Solution:

- Verify Calibration: Regularly calibrate your instrument using certified reference materials with known surface parameters. Ensure your calibrations are traceable to national standards [10].

- Check Instrument Parameters: Confirm that measuring force, stylus tip size, and measuring speed are appropriate for your sample material and surface texture [10].

- Assess Sample Preparation: Ensure samples are clean, properly mounted, and representative of the surface being characterized. Improper sampling can lead to biased results regardless of subsequent analysis accuracy [9].

- Environmental Controls: Monitor laboratory conditions as temperature and humidity fluctuations can affect both instruments and samples, particularly for high-precision measurements.

Poor Measurement Precision/Reproducibility

Problem: Repeated measurements of the same surface area show unacceptably high variation.

Explanation: Precision is a measure of the reproducibility or repeatability of a method, reflecting how close multiple measurements are to each other under the same conditions. A precise method will produce a tight cluster of results, even if they are not entirely accurate. In surface metrology, this is often expressed as the standard deviation or relative standard deviation of multiple measurements [9].

Solution:

- Standardize Measurement Protocol: Develop and adhere to a detailed standard operating procedure specifying measurement location, direction, and environmental conditions.

- Evaluate Instrument Stability: Check for mechanical wear, particularly on tactile profilometer styli, or optical issues in non-contact systems. The Mitutoyo SJ-301, for instance, offers different measuring speeds and forces to optimize for different surface types [10].

- Operator Training: Ensure consistent operator technique through regular training and proficiency assessment. A lack of trained personnel can lead to high error rates and compromised data quality [9].

- Implement Statistical Control: Use control charts to monitor measurement variation over time and identify when the process is becoming unstable.

Specificity Challenges in Complex Surfaces

Problem: Inability to distinguish target surface features from background texture or contamination.

Explanation: Specificity is the ability of a method to measure a single, target analyte without interference from other components in the sample matrix. In surface measurement, this translates to distinguishing specific surface features of interest from overall topography, which is particularly challenging with complex geometries or contaminated surfaces [9].

Solution:

- Advanced Form Removal: Utilize software with advanced form removal algorithms that can extract roughness parameters from complex surfaces including radii, threads, and spherical surfaces with underlying form [11].

- Optimal Technique Selection: For particularly challenging surfaces, consider transitioning from 2D profile measurements to 3D areal surface measurement, which provides more comprehensive topographic information [12] [11].

- Surface Cleaning Protocol: Implement rigorous cleaning procedures to remove contaminants that might interfere with measurement specificity.

- Data Filtering: Apply appropriate digital filters to separate roughness, waviness, and form components according to ISO standards [12].

Difficulty Determining Limits of Detection and Quantification

Problem: Uncertainty in establishing the smallest detectable surface feature or measurable roughness value.

Explanation: The Limit of Detection is the smallest change in surface topography that can be reliably detected, while the Limit of Quantification is the smallest change that can be reliably measured with acceptable accuracy and precision. These parameters are crucial for trace analysis in surface measurement [9].

Solution:

- Apply Statistical Methods: Use the calibration curve method where LOD = 3.3σ/S and LOQ = 10σ/S, with σ representing the standard deviation of the response and S being the slope of the calibration curve [13].

- Standard Deviation Approach: Calculate based on the standard deviation of multiple measurements on a nominally smooth surface, which is equivalent to the standard deviation of the noise [13].

- Experimental Verification: After calculation, validate estimated LOD and LOQ by performing multiple measurements at those levels to confirm they meet performance requirements [13].

- Signal-to-Noise Assessment: Use signal-to-noise ratio approaches to confirm that LOD consistently meets 3:1 requirements and LOQ meets 10:1 requirements [13].

Performance Parameter Reference Tables

Key Performance Parameters and Definitions

| Parameter | Definition | Importance in Surface Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of measured value to true or accepted value [9] | Ensures surface measurements reflect actual surface characteristics |

| Precision | Measure of reproducibility or repeatability of measurements [9] | Determines consistency of repeated surface measurements under same conditions |

| Specificity | Ability to measure target surface features without interference from matrix [9] | Enables distinction of specific surface features from overall topography |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Smallest change in surface topography that can be reliably detected [9] | Determines minimum detectable surface feature size or roughness change |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Smallest change in surface topography that can be reliably quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [9] | Establishes minimum measurable surface feature with reliable quantification |

LOD and LOQ Calculation Methods

| Method | Formula | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Curve | LOD = 3.3σ/SLOQ = 10σ/SWhere σ = standard deviation of response, S = slope of calibration curve [13] | Preferred method; uses linear regression data from calibration studies |

| Standard Deviation of Blank | Based on standard deviation of measurements on smooth reference surface [13] | Equivalent to standard deviation of noise; suitable for establishing instrument capability |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | LOD: S/N ≥ 3:1LOQ: S/N ≥ 10:1 [13] | Practical method for quick verification of calculated values |

Surface Roughness Parameters and Standards

| Parameter Type | Common Parameters | Applicable Standards |

|---|---|---|

| 2D Profile (R-parameters) | Ra, Rq, Rz | ISO 4287, ISO 4288 [12] |

| 3D Areal (S-parameters) | Sa, Sq, Sz | ISO 25178-2 [12] |

| Bearing Area Curve | Sk, Spk, Svk | ISO 13565 [12] [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Surface Roughness Measurement

Objective: To obtain accurate, precise, and reproducible surface roughness measurements using either contact or non-contact methods.

Materials and Equipment:

- Surface roughness tester (e.g., Mitutoyo SJ-301 profilometer or optical 3D surface profiler) [10] [11]

- Certified roughness reference standards

- Appropriate mounting fixtures

- Cleaning supplies (solvents, lint-free wipes)

- Stable measurement environment (vibration-free table, temperature control)

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration:

- Use certified reference standards with known Ra/Sa values

- Calibrate instrument according to manufacturer specifications

- Verify calibration using a different standard than used for calibration

Sample Preparation:

- Clean surface thoroughly to remove contaminants

- Mount securely to prevent movement during measurement

- Ensure measurement orientation follows engineering drawing specifications

Parameter Selection:

- Select appropriate filter settings (e.g., Gaussian) according to ISO standards

- Choose evaluation length sufficient for representative sampling

- Set measuring force appropriate for material (e.g., 0.75mN for delicate surfaces) [10]

Measurement Execution:

- Perform multiple measurements at different representative locations

- Maintain consistent tracking force and speed

- Document all measurement parameters and environmental conditions

Data Analysis:

Validation: Verify method by measuring certified reference material and confirming results fall within certified uncertainty range.

Protocol for Determining LOD and LOQ in Surface Measurement

Objective: To establish the smallest detectable and quantifiable changes in surface topography using statistical methods.

Materials and Equipment:

- Surface measurement instrument with verified calibration

- Reference samples with progressively finer surface features

- Data analysis software with regression capabilities

Procedure:

- Calibration Curve Development:

- Measure a series of reference samples with known, progressively finer surface features

- Plot instrument response (e.g., measured roughness) versus reference values

- Perform linear regression to obtain slope (S) and standard error (σ)

Calculation:

Experimental Verification:

Documentation:

- Record all raw data, regression statistics, and calculations

- Document verification measurements and their compliance with acceptance criteria

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between accuracy and precision in surface measurement?

Accuracy refers to how close a measured value is to the true surface characteristic value, while precision refers to how close repeated measurements are to each other. You can have precise measurements that are consistently wrong (inaccurate) or accurate measurements with high variability (imprecise). Ideal surface measurement achieves both high accuracy and high precision [9].

Q2: When should I use 2D versus 3D surface roughness parameters?

2D profile parameters (Ra, Rz) are well-established and suitable for many quality control applications where traditional specifications exist. 3D areal parameters (Sa, Sz) provide more comprehensive surface characterization as they evaluate the entire surface rather than just a single line profile. 3D analysis is particularly valuable for functional surface characterization and complex surfaces where a single profile cannot adequately represent the topography [12] [11].

Q3: How often should I calibrate my surface measurement instrumentation?

Calibration frequency depends on usage intensity, required measurement uncertainty, and quality system requirements. For critical measurements in regulated environments, calibration should be performed at least annually or according to manufacturer recommendations. Additionally, daily or weekly verification using reference standards is recommended to ensure ongoing measurement validity [10].

Q4: What are the most common causes of poor specificity in surface measurements?

Common causes include: (1) inappropriate filter settings that don't properly separate roughness from waviness, (2) measurement artifacts from improper sample preparation or mounting, (3) interference from surface contaminants, and (4) insufficient measurement resolution for the feature size of interest. Implementing advanced form removal algorithms can significantly improve specificity on complex geometries [11].

Q5: Why must LOD and LOQ values be validated experimentally after calculation?

Statistical calculations provide estimates, but experimental verification confirms these estimates work in practice with your specific instrument, operator, and conditions. Regulatory guidelines require demonstrating that samples at the LOD can be reliably detected and samples at the LOQ can be quantified with acceptable precision in actual measurements [13].

Measurement Process Workflow

Surface Measurement Process Flow

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Surface Measurement

| Material/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Roughness Standards | Instrument calibration and verification | Provide traceable reference values for ensuring measurement accuracy [10] |

| Stable Mounting Fixtures | Sample positioning and stability | Critical for measurement repeatability; minimizes vibration artifacts |

| Cleaning Solvents | Surface contamination removal | Essential for measurement specificity; must not alter surface properties |

| Reference Materials with Known Features | LOD/LOQ determination | Used to establish minimum detectable and quantifiable feature sizes [13] |

| Optical Flat Standards | Flatness accuracy assessment | Crucial for validating measurement of flatness and parallelism [12] |

Troubleshooting Guides: Sample Contamination in LC-MS

Q: Why is my LC-MS baseline unusually high, and how can I resolve it?

A high baseline often indicates the presence of ionizable contaminants entering the mass spectrometer. These contaminants can originate from various sources, including the analyst themselves, solvents, or instrumentation. To resolve this, systematically check the following:

- Source: Contaminants from skin, hair, or personal products (like lotions) can be transferred during sample or mobile phase preparation. Impurities in mobile phase additives or solvents are also common culprits [14].

- Solution: Always wear nitrile gloves when handling solvents, samples, or any instrument components. Use dedicated, high-purity (LC-MS grade) solvents and additives from a reliable source and avoid filtering mobile phases unless absolutely necessary, as filters can leach contaminants [14].

Q: I observe a sudden, severe drop in analyte signal. What could be the cause?

This is a classic sign of ion suppression, often caused by a co-eluting contaminant that alters ionization efficiency in the source.

- Source: A contaminated source of mobile phase additive, such as formic acid from a plastic container, can introduce ion-suppressing compounds. Polymers from surfactants (e.g., Tween, Triton X-100) or PEGs from pipette tips and wipes are also frequent causes [14] [15].

- Solution: Check the provenance of all mobile phase additives. Avoid using surfactants in sample preparation. If you must use them, ensure they are completely removed via a robust solid-phase extraction (SPE) clean-up step [15]. Consistently use additives from a trusted source [14].

Q: How can I prevent keratin contamination in my sensitive proteomics samples?

Keratin from skin, hair, and dust is one of the most abundant protein contaminants and can obscure low-abundance target peptides.

- Source: The analyst's skin, hair, clothing (especially natural fibers like wool), and dust in the laboratory air [15].

- Solution: Perform sample preparation in a laminar flow hood. Always wear a lab coat and gloves, replacing gloves after touching potentially contaminated surfaces like notebooks or pens. Avoid wearing clothing made from natural fibers in the lab [15].

Troubleshooting Guides: Matrix Effects

Q: What are matrix effects, and how do they impact my quantitative results?

Matrix effects (ME) are the combined influence of all sample components other than the analyte on its measurement. In LC-MS, co-eluting compounds can suppress or enhance the ionization of your target analyte, leading to inaccurate quantification, reduced sensitivity, and poor method reproducibility [16].

Q: How can I evaluate and identify matrix effects in my method?

You can assess MEs qualitatively and quantitatively using these standard methods [16]:

Table 1: Methods for Evaluating Matrix Effects

| Method Name | Description | Output | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Column Infusion [16] | A blank matrix extract is injected while the analyte is infused post-column. | A chromatogram showing regions of ion suppression/enhancecence. | Qualitative only; does not provide a numerical value for ME. |

| Post-Extraction Spike [16] | Compares the response of the analyte in pure solution to its response when spiked into a blank matrix extract. | A quantitative measure of ME (e.g., % suppression/enhancement). | Requires a blank matrix, which is not always available. |

| Slope Ratio Analysis [16] | Compares the calibration curve slopes of the analyte in solvent versus the matrix. | A semi-quantitative measure of ME across a concentration range. | Does not require a blank matrix, but is less precise. |

The following workflow illustrates the application of these methods during method development:

Q: What practical steps can I take to minimize matrix effects?

- Improve Chromatography: Adjust the LC method to increase separation and shift the analyte's retention time away from the suppression/enhancement zone identified by post-column infusion [16].

- Enhance Sample Cleanup: Incorporate a selective sample preparation step, such as Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), to remove interfering compounds from the sample matrix [16].

- Use Alternative Ionization: If using Electrospray Ionization (ESI) with severe suppression, try Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), which is often less prone to certain types of MEs [16].

- Use Internal Standards: Isotope-labeled internal standards are the gold standard for compensating for matrix effects, as they co-elute with the analyte and experience the same ionization suppression/enhancement [16].

Troubleshooting Guides: Instrumental Artifacts

Q: My peptide sample recovery is low. Could the sample vials be the problem?

Yes, peptides and proteins can adsorb to the surfaces of sample vials, especially glass.

- Source: Adsorption of analytes to the walls of glass or plastic vials and pipette tips [15].

- Solution: Use "high-recovery" vials specifically designed to minimize adsorption. Avoid completely drying down samples; leave a small amount of liquid. Limit the number of sample transfers between containers. Consider "priming" vials with a sacrificial protein like BSA to saturate adsorption sites [15].

Q: I see strange, regularly spaced peaks in my mass spectrum. What are these?

These are characteristic of polymer contamination.

- Source: Polyethylene glycols (PEGs) show 44 Da spacing, and polysiloxanes show 74 Da spacing. Sources include pipette tips, certain wipes, skin creams, and surfactant-based cell lysis buffers [15].

- Solution: Scrutinize all materials that contact your samples. Avoid using surfactant-based lysis methods. If polymers are present, a rigorous SPE clean-up may be needed, though prevention is the best strategy [15].

Q: How can I prevent contamination from my water purification system?

Even high-quality water can become contaminated.

- Source: In-line filters used in water purification systems can leach PEGs. Water can also accumulate contaminants from the lab air or storage containers over time [15].

- Solution: Use high-purity water promptly after production (within a few days). Dedicate specific bottles for LC-MS use only and never wash them with detergent [14] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrile Gloves | Prevents transfer of keratins, lipids, and amino acids from skin to samples and solvents [14]. | Wear at all times during handling; change after touching non-sterile surfaces. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents/Additives | High-purity mobile phase components minimize background signals and ion suppression [14]. | Use dedicated bottles for each solvent; stick with a trusted supplier. |

| PFAS-Free Water | Critical for ultra-trace analysis of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances to prevent false positives [17]. | Must be supplied and verified as "PFAS-free" by the analytical laboratory. |

| High-Recovery Vials | Engineered surfaces minimize adsorption of valuable peptides/proteins, improving recovery [15]. | Superior to standard glass or plastic vials for sensitive biomolecule analysis. |

| Formic Acid (LC-MS Grade) | Common mobile phase additive for peptide/protein analysis to aid protonation [14]. | Ensure it is supplied in a glass container, not plastic, to avoid leachables. |

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Compensates for matrix effects and analyte loss during preparation, ensuring accurate quantification [16]. | Should be added to the sample as early in the preparation process as possible. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Matrix Effects via Post-Column Infusion

This protocol allows for the qualitative identification of chromatographic regions affected by ion suppression or enhancement [16].

1. Equipment and Reagents:

- LC-MS system with a post-column T-piece for infusion.

- Syringe pump for constant infusion.

- Standard solution of the target analyte.

- Prepared blank sample extract (matrix without the analyte).

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Connect the syringe pump, loaded with the analyte standard, to the post-column T-piece.

- Step 2: Start a constant infusion of the standard at a steady flow rate, creating a stable background signal in the mass spectrometer.

- Step 3: Using the LC autosampler, inject the blank sample extract. Run the chromatographic method as usual.

- Step 4: Monitor the total ion chromatogram (TIC) or the extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) for the infused analyte.

3. Data Interpretation:

- A stable signal indicates no matrix effects.

- A dip in the signal indicates ion suppression.

- A peak in the signal indicates ion enhancement.

The methodology is summarized in the diagram below:

Data Integrity Fundamentals and Regulatory Landscape

Data integrity is the cornerstone of reliable scientific research and regulatory compliance in the pharmaceutical and clinical sectors. It ensures that data remains complete, consistent, and accurate throughout its entire lifecycle. Regulatory agencies worldwide mandate strict adherence to data integrity principles to guarantee the safety, efficacy, and quality of pharmaceutical products [18] [19].

The ALCOA+ Framework

The foundational principle for data integrity in regulated industries is encapsulated by the ALCOA+ framework, which stipulates that all data must be [18]:

- Attributable: Who acquired the data or performed an action, and when?

- Legible: Can the data be read and understood permanently?

- Contemporaneous: Was the data recorded at the time of the activity?

- Original: Is this the first capture of the data (or a certified copy)?

- Accurate: Does the data reflect the true observation or measurement without alteration?

The "+" emphasizes that data should also be Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available throughout the data lifecycle [18].

Regulatory Consequences of Failure

Failure to maintain data integrity triggers significant regulatory actions. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies inspection outcomes to signify compliance levels [18]:

Table: FDA Inspection Classifications and Implications

| Classification | Description | Regulatory Implications |

|---|---|---|

| No Action Indicated (NAI) | No significant compliance issues found. | No further regulatory action required. |

| Voluntary Action Indicated (VAI) | Regulatory violations found, but not deemed critical. | Firm must correct issues; no immediate regulatory action. |

| Official Action Indicated (OAI) | Significant violations were observed. | FDA will take further action, which may include Warning Letters, injunction, or product seizure. |

The FDA's Bioresearch Monitoring (BIMO) Program, which oversees clinical investigations, frequently cites specific violations. An analysis of warning letters revealed the most common data integrity issues [18]:

- Failure to follow and maintain procedures

- Poor documentation practices

- Inadequate protocol adherence

- Insufficient adverse event reporting

Real-world impacts are severe. For instance, the FDA has denied drug applications due to incomplete data from clinical trials and has placed companies on import alert for non-compliance with good manufacturing practices, blocking their products from the market [20].

Troubleshooting Common Data Quality Issues

This section provides a practical guide for researchers to identify, resolve, and prevent common data integrity problems.

Data Quality Issue Identification

Table: Common Data Quality Issues and Mitigation Strategies

| Data Quality Issue | Description & Impact | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Duplicate Data | Redundant records from multiple sources skew analytics and machine learning models [21]. | Implement rule-based data quality tools to detect and flag duplicate records using probabilistic matching [22] [21]. |

| Inaccurate/Missing Data | Data that is incorrect or incomplete provides a false picture, leading to faulty conclusions [21]. | Use specialized data quality solutions for early detection and proactive correction in the data lifecycle [22] [21]. |

| Inconsistent Data | Mismatches in formats, units, or values across different data sources degrade reliability [21]. | Deploy data quality management tools that automatically profile datasets and flag inconsistencies using adaptive, self-learning rules [21]. |

| Outdated Data | Data that is no longer current leads to inaccurate insights and poor decision-making [21]. | Establish a data governance plan with regular reviews and use machine learning to detect obsolete records [21]. |

| Unstructured Data | Text, audio, or images without a defined model are difficult to store, analyze, and validate [21]. | Leverage automation, machine learning, and strong data governance policies to transform unstructured data into usable formats [21]. |

FAQ: Addressing Researcher Questions

Q1: Our analytical lab generates vast amounts of LC-MS/MS data. What is the first step in ensuring its integrity for regulatory submission? A1: Begin with the ALCOA+ framework. Ensure all data is attributable to a specific user via secure login, recorded contemporaneously with automated timestamps, and stored in its original format with protected audit trails. Implement a robust Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) to enforce these protocols automatically [18] [9].

Q2: We've found discrepancies in unit of measure between two legacy data sources. How can we resolve this without manual review? A2: This is a classic "Inconsistent Data" issue. Tools like DataBuck can automate the validation of units of measure across large datasets. They can automatically recommend and apply baseline rules to flag and correct such discrepancies, improving scalability and reducing manual errors [20].

Q3: What are the "Three Cs" of data visualization, and how can they help me interpret complex chromatography data? A3: The Three Cs are Correlation, Clustering, and Color.

- Correlation (e.g., Pearson, Euclidean distance) measures similarity between samples or features.

- Clustering (e.g., Hierarchical Clustering Analysis) groups similar items, revealing broader patterns.

- Color projects these patterns intuitively, allowing your brain to quickly identify sample classes and distinguishing features in a heatmap. Experiment with different combinations of similarity measures and linkage methods to find the best fit for your specific dataset [23].

Q4: How can I proactively identify "unknown unknown" data quality issues, like hidden correlations or unexpected data relationships?

A4: Use advanced data profiling tools that go beyond predefined rules. Solutions like ydata-quality or data catalogs can perform deep data reconnaissance, uncovering cross-column anomalies and hidden correlations that you may not have considered, thus revealing "unknown unknowns" in your data [22] [21].

Experimental Protocols for Data Integrity

Protocol: Data Quality Assessment for a New Dataset

Objective: To systematically identify and rank data quality issues in a new or existing dataset prior to analysis.

Materials:

- Dataset (e.g., in CSV, database format)

- Python environment with

pandasandydata-qualitylibraries installed - Computational resources suitable for the dataset size

Methodology:

- Library Import and Data Loading:

- Engine Initialization and Evaluation: This generates a report listing data quality warnings, their priority (P1 being highest), and the responsible module (e.g., 'Duplicates', 'Data Relations') [22].

- In-Depth Issue Investigation:

- To get details on a specific warning, such as duplicate columns:

- Targeted Module Analysis:

- For specific checks like bias and fairness, run standalone modules:

- Data Cleaning and Validation:

- Based on the warnings, create a targeted data cleaning pipeline (e.g., dropping duplicate columns, standardizing categorical values).

- Run the

DataQualityengine again on the cleaned data to verify that the high-priority issues have been resolved [22].

Workflow: Ensuring Data Integrity in Analytical Data Lifecycle

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and checks for maintaining data integrity from data generation through to analysis and reporting, specifically within the context of an analytical chemistry workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Tools and Technologies for Data Integrity Management

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality Libraries | ydata-quality (Python) |

An open-source library for performing automated data quality assessments, providing priority-based rankings of issues like duplicates, drift, and biases [22]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Benchling, LabWare, STARLIMS | Centralizes sample and experimental data, enforces Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), and manages workflows to ensure data is attributable, original, and enduring [9]. |

| Data Visualization & Analysis | R packages (pheatmap, corrplot), Python (Matplotlib, Plotly) |

Apply the "Three Cs" (Correlation, Clustering, Color) to explore complex datasets, identify patterns, and detect outliers in analytical data [23]. |

| Chromatography Data Systems (CDS) | Empower, Chromeleon | Acquire, process, and manage chromatographic data with built-in audit trails, electronic signatures, and data security features compliant with 21 CFR Part 11 [9]. |

| Automated Data Validation Tools | DataBuck | Uses machine learning to automatically validate large datasets, check for trends, unit of measure consistency, and data drift without constant manual rule updates [20]. |

Key Analytical Techniques and Their Biomedical Applications

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is a powerful, surface-sensitive analytical technique used to determine the quantitative atomic composition and chemistry of material surfaces [24]. This technique probes the outermost ~10 nm (approximately 30 atomic layers) of a material, making it invaluable for studying surface-mediated processes and phenomena where surface composition differs significantly from the bulk material [25].

The fundamental physical principle underlying XPS is the photoelectric effect, where a material irradiated with X-rays emits electrons called photoelectrons [26]. The kinetic energy of these emitted photoelectrons is measured by the instrument, and the electron binding energy is calculated using the equation: Ebinding = Ephoton - (Ekinetic + φ), where φ is the spectrometer's work function [25] [26]. Each element produces a set of characteristic peaks corresponding to the electron configuration within its atoms (e.g., 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s), and the number of detected electrons in each peak is directly related to the amount of the element present in the sampling volume [26]. A key strength of XPS is its ability to provide chemical state information through measurable shifts in the binding energy of photoelectrons, known as chemical shifts, which occur when an element enters different bound states [24] [25].

Core Capabilities and Technical Specifications

XPS is a versatile technique applicable to a wide range of materials, including inorganic compounds, metal alloys, semiconductors, polymers, ceramics, glasses, biomaterials, and many others [26] [27]. Its core capabilities stem from the fundamental information carried by the photoelectrons.

Key Analytical Strengths

- Elemental Composition: Identifies and quantifies all elements present on a surface except hydrogen and helium [24] [26].

- Chemical State Information: Distinguishes different oxidation states and chemical environments (e.g., sulfide vs. sulfate, metal vs. oxide) [24] [25].

- Empirical Formulas: Provides quantitative, semi-quantitative analysis to determine empirical formulas of surface materials [28].

- Surface Sensitivity: Analyzes the top 1-10 nm of a material, which is often chemically distinct from the bulk [25] [28].

- Depth Profiling: Characterizes thin film composition as a function of depth, either destructively via ion sputtering or non-destructively via angle-resolved measurements [24] [28].

Technical Specifications and Limitations

The utility of XPS is defined by its specific technical capabilities and inherent limitations, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Technical specifications and limitations of XPS analysis

| Parameter | Capability/Limitation | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Elements Detected | Lithium to Uranium [24] | Does not detect H or He [24] [26]. |

| Detection Limits | ~0.1–1 atomic % (1000-10000 ppm) [24] [26] | Can reach ppm levels for favorable elements with long collection times [26]. |

| Depth Resolution | 1-10 nm (surface analysis); 20-200 Å (sputter profiling) [24] [28] | Varies with technique and material [24]. |

| Lateral Resolution | ≥ 30 µm [24] | Specialized instruments can achieve sub-micron resolution [4]. |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ~90-95% for major peaks; 60-80% for minor peaks [26] | Accuracy depends on signal-to-noise, sensitivity factors, and sample homogeneity [26]. |

| Sample Requirements | Must be Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) compatible [24] | Typical operating pressure < 10-9 Torr [26]. |

| Sample Degradation | Possible for polymers, catalysts, and some organics [26] | Metals, alloys, and ceramics are generally stable [26]. |

The XPS Process and Data Interpretation

The XPS Workflow

A typical XPS analysis follows a logical sequence of steps to extract comprehensive surface information. The diagram below illustrates this workflow, from sample preparation to final data interpretation.

Modes of Data Acquisition

The workflow involves three primary modes of data acquisition, each serving a distinct purpose:

- Survey Scan (Wide Energy Range): A broad scan over the entire energy range to identify all elements present on the surface, enabling qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis [24].

- High-Resolution Scan (Narrow Energy Range): A detailed scan of specific elemental peaks under high energy resolution to determine chemical state information from precise peak position and shape [24] [25].

- Depth Profiling: Alternating cycles of ion sputtering (material removal) and XPS analysis to measure elemental composition as a function of depth, crucial for characterizing thin films and interfaces [24] [28].

Interpreting Chemical State Information

The core of XPS data interpretation lies in analyzing the high-resolution spectra. Chemical state information is derived from two main features:

- Chemical Shifts: Changes in binding energy resulting from the element's chemical environment. For example, an increase in the oxidation state typically leads to an increase in binding energy [25]. This allows researchers to distinguish between metal, oxide, and sulfide species, among others.

- Spin-Orbit Splitting: For electrons in p, d, or f orbitals, a characteristic doublet is observed (e.g., 2p₁/₂ and 2p₃/₂). The separation energy and the fixed area ratio between these doublet peaks are used to confirm the element's identity [25].

Common Data Interpretation Challenges and Troubleshooting

Despite its relative simplicity, XPS data interpretation is prone to specific, recurring errors. It is estimated that about 40% of published papers using XPS contain errors in peak fitting [4]. The following section addresses these common challenges in a troubleshooting format.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My sample is an insulator, and my spectrum shows a large, broad peak shift. How can I correct for this?

- Problem: Surface charging on insulating samples causes a positive charge buildup as photoelectrons are emitted, leading to a shift in the measured kinetic energies (and thus calculated binding energies) of all peaks [25].

- Solution: Use the instrument's charge neutralization system (electron flood gun) to replace lost electrons and stabilize the surface potential [28]. Additionally, for slight shifts, spectra can be calibrated by referencing the C 1s peak from adventitious carbon (ubiquitous hydrocarbon contamination) to a standard value, typically 284.8 eV [25].

FAQ 2: When fitting my high-resolution spectrum, the fit seems poor or unrealistic. What are the common pitfalls in peak fitting?

- Problem: Incorrect application of constraints and peak shapes leads to physically meaningless results [4].

- Solution:

- Use proper peak shapes: For metals, use asymmetric line shapes; for oxides and most other species, use symmetric, mixed Gaussian-Lorentzian line shapes [4].

- Apply correct constraints: For doublets (e.g., p, d, f peaks), constrain the peak area ratio (e.g., 2:1 for p orbitals, 3:2 for d orbitals) and the spin-orbit splitting energy. However, do not force the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of doublet peaks to be identical, as the higher-energy peak often has a slightly larger FWHM [4].

FAQ 3: How can I be sure my analysis is not damaging the sample surface?

- Problem: Some materials, particularly polymers, catalysts, and organic compounds, can degrade under X-ray exposure, especially from non-monochromatic sources that produce more heat and Bremsstrahlung X-rays [26].

- Solution: Use a monochromatic X-ray source, which reduces heat load and removes high-energy Bremsstrahlung radiation [26]. Monitor the carbon C 1s peak shape over time for signs of damage and minimize the total X-ray dose when analyzing sensitive materials.

FAQ 4: My depth profile shows mixing of layers and poor depth resolution. What could be the cause?

- Problem: Sputter depth profiling with monatomic ions (e.g., Ar⁺) can cause atomic mixing, preferential sputtering, and damage to the chemical structure, especially in organics and polymers, blurring the original in-depth composition [25] [28].

- Solution: For organic and soft materials, use a gas cluster ion source (e.g., Arn+ or C60+). These larger clusters sputter with minimal damage and penetration, preserving the chemical information of the underlying layers and enabling accurate depth profiling of soft materials [28] [27].

Common Peak Fitting Errors and Corrections

The table below summarizes frequent peak-fitting errors and their proper corrections to ensure accurate data interpretation.

Table 2: Common XPS peak fitting errors and their solutions

| Common Error | Impact on Data | Proper Correction Method |

|---|---|---|

| Using symmetrical peaks for metallic species [4] | Introduces extra, non-physical peaks to fit the asymmetry | Use an asymmetric line shape for metals to account for the conduction band interaction [4]. |

| Incorrect or missing doublet constraints [4] | Produces incorrect chemical state ratios and misidentifies species | Constrain the area ratio (e.g., 2:1 for p3/2:p1/2) and the separation energy based on literature values [4]. |

| Forcing identical FWHM for doublets [4] | Creates an inaccurate fit, as the higher BE component naturally has a slightly larger width | Allow the FWHM of the two doublet components to vary independently within a reasonable range [4]. |

| Over-fitting with too many components | Creates a model that fits the noise, not the chemistry | Justify each component with known chemistry and use the minimum number of peaks required for a good fit. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for XPS Analysis

A functional XPS instrument consists of several key components, each critical for successful analysis. Furthermore, specific reagents and materials are central to the technique's operation and calibration.

Key Instrument Components

Table 3: Essential components of an XPS instrument and their functions

| Component | Function | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Source | Generates X-rays to excite the sample. | Typically Al Kα (1486.6 eV) or Mg Kα (1253.6 eV); can be monochromatic or non-monochromatic [25] [26]. |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) System | Creates a clean environment for electron detection. | Operating pressure <10-9 Torr; prevents scattering of photoelectrons by gas molecules [25] [26]. |

| Electron Energy Analyzer | Measures the kinetic energy of emitted photoelectrons. | Typically a Concentric Hemispherical Analyzer (CHA) [25]. |

| Ion Gun | Sputters the surface for cleaning or depth profiling. | Often Ar⁺ source; gas cluster sources (e.g., Arn+) are used for organic materials [25] [28]. |

| Charge Neutralizer (Flood Gun) | Compensates for surface charging on insulating samples. | Low-energy electron beam that supplies electrons to the surface [28]. |

| Electron Detector | Counts the number of photoelectrons at each energy. | Position-sensitive detector, often used for imaging [27]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key materials and reference standards used in XPS analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function in XPS Analysis |

|---|---|

| Adventitious Carbon | In-situ reference for charge correction. The C 1s peak is set to 284.8 eV [25]. |

| Sputter Depth Profiling Standards | Calibrate sputter rates. Typically, a known thickness of SiO₂ on Si [25]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Used for absolute quantification and verification of instrumental sensitivity factors [26]. |

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes (e.g., Cu) | Mounting powdered or non-conducting samples to ensure good electrical and thermal contact with the sample holder. |

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that uses a focused electron beam to excite atoms within the outermost 1-10 nanometers of a solid sample. The analysis relies on detecting the kinetic energy of emitted Auger electrons, which is characteristic of the elements from which they originated, to determine surface composition [29] [30] [31].

The Auger process involves a three-step mechanism within an atom. First, an incident electron with sufficient energy ejects a core-level electron, creating a vacancy. Second, an electron from a higher-energy level fills this vacancy. Third, the energy released from this transition causes the ejection of another electron, known as the Auger electron, from a different energy level [30]. The kinetic energy of this Auger electron is independent of the incident beam energy and serves as a unique fingerprint for the element, and in some cases, its chemical state [29] [30].

AES is particularly valuable because it can detect all elements except hydrogen and helium, with detection limits typically ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 atomic percent [29]. When combined with ion sputtering, AES can perform depth profiling to characterize elemental composition as a function of depth, up to several micrometers beneath the surface [29] [30].

Comparison of AES with XPS

| Feature | AES (Auger Electron Spectroscopy) | XPS (X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Source | Focused electron beam [31] | X-rays [31] |

| Analyzed Elements | All except H and He [29] | All except H [31] |

| Spatial Resolution | High (can be down to ~12 nm) [29] | Lower (typically tens of micrometers) [31] |

| Sample Conductivity | Requires conductive or semiconducting samples [29] [31] | Suitable for both conductors and insulators [31] |

| Primary Information | Elemental composition, some chemical state information [30] | Elemental composition, chemical state, and electronic structure [31] |

| Ideal Use Cases | High-resolution surface mapping, depth profiling of conductors [31] | Analysis of insulating materials, detailed chemical bonding information [31] |

Common Experimental Challenges & Data Interpretation Pitfalls

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when performing AES analysis, which can lead to misinterpretation of data.

- Surface Contamination: The surface sensitivity of AES means that adventitious carbon, oxygen, or other contaminants from air exposure can dominate the spectrum, obscuring the true sample composition [30].

- Charge Accumulation on Insulators: The incident electron beam can cause localized charging on non-conductive samples, leading to peak shifts, broadening, and distorted line shapes, which complicates both qualitative and quantitative analysis [31].

- Peak Overlap and Interferences: Auger peaks from different elements can overlap, and peaks from the same element can appear multiple times. Furthermore, low-intensity peaks from trace elements can be overshadowed by stronger signals, while energy loss peaks can be mistaken for authentic Auger peaks [30].

- Sample Damage: The focused electron beam can thermally degrade or electronically damage sensitive materials, such as some polymers or thin organic films, altering the surface chemistry during analysis [31].

- Preferential Sputtering in Depth Profiling: During depth profiling using ion sputtering, elements with higher sputtering yields are removed faster than others. This alters the measured surface composition relative to the true bulk composition, leading to inaccurate depth profiles [30].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: My AES spectrum shows very high carbon and oxygen signals, overwhelming the elements of interest. What should I do?

This is a classic sign of surface contamination. Ensure samples are cleaned with appropriate solvents (e.g., alcohols, acetone) and/or dried thoroughly before introduction into the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. If possible, implement in-situ cleaning methods such as argon ion sputtering immediately before analysis to remove the contaminated layer.

FAQ: The AES peaks from my semiconductor sample are shifting and broadening during analysis. What is the cause?

This is likely caused by surface charging. For non-conductive or semi-conductive samples, apply a thin, uniform coating of a conductive material such as gold or carbon. Using a lower primary electron beam energy or current can also help mitigate charging effects. Some modern instruments can compensate for charging with electron floods.

FAQ: During depth profiling, the interface between two layers appears more diffuse than expected. Is this real?

Not necessarily. Ion beam mixing during sputtering can artificially broaden interfaces. To minimize this, use lower ion beam energies and oblique incidence angles for sputtering, as this can reduce atomic mixing and provide a more accurate depth resolution.

Troubleshooting Common AES Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Incorrect beam alignment, sample not grounded, detector failure, or excessive surface roughness. | Verify beam alignment and focus on a standard sample, ensure good electrical contact between sample and holder, check detector settings and high voltage, analyze smoother sample regions [29] [31]. |

| Poor Spatial Resolution | Electron beam is not properly focused, or the working distance is incorrect. | Adjust the focus and stigmation of the electron gun, optimize the working distance as per the instrument manual, use a smaller aperture if available [29]. |

| Unidentified Peaks in Spectrum | Surface contamination, overlap of Auger peaks from different elements, or energy loss peaks. | Clean the sample surface in-situ, consult standard AES spectral libraries for peak identification, analyze the peak shape and position for potential overlaps [30]. |

| Inconsistent Quantitative Results | Uncorrected matrix effects, variation in surface topography, or unstable electron beam current. | Use relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) and standard samples for quantification, analyze flat and uniform sample areas, ensure the electron gun emission is stable [30]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes (e.g., Carbon Tape) | Mounting powdered or irregular samples to a holder; provides electrical pathway to ground. | Ensure the tape does not outgas excessively in UHV and that its elemental signature (e.g., C for carbon tape) does not interfere with the analysis. |

| Reference Standard Samples | Calibration of energy scale and verification of quantitative sensitivity factors. | Pure, well-characterized, and atomically clean metal foils (e.g., Cu, Ag, Au) are commonly used. |

| Demineralized / Single-Distilled Water | Used in environmental AES chambers with humidity control; prevents system clogs. | Water that is too pure (deionized) or not pure enough (tap water) can cause humidity control issues and damage [32]. |

| Argon (Ar) Gas | Source for ion sputtering gun for in-situ cleaning and depth profiling. | High-purity (99.9999%) argon is essential to prevent introducing contaminants to the sample surface during sputtering. |

| Conductive Coatings (Au, C) | Sputter-coated onto insulating samples to dissipate charge from the electron beam. | Use the thinnest possible coating to avoid masking the sample's intrinsic surface chemistry; carbon is often preferred for its less intrusive Auger spectrum. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Qualitative Elemental Surface Analysis

Objective: To identify the elements present within the analysis volume of the sample surface.

- Sample Preparation: Clean the conductive sample to remove surface contaminants. Mount it securely on a stub using conductive tape to ensure electrical grounding.

- Instrument Setup: Insert the sample into the UHV chamber and pump down to operating pressure (typically <10-8 Torr). Select a primary electron beam energy (e.g., 10 keV) and a beam current that provides sufficient signal without causing damage.

- Data Acquisition: Position the electron beam on the area of interest. Acquire a survey spectrum over a wide energy range (e.g., 0-1000 eV or 0-2000 eV) to capture all potential Auger transitions.

- Data Interpretation: Identify the elements present by comparing the kinetic energies of the major peaks in the acquired spectrum with standard AES reference spectra from databases or pure element standards [30].

Protocol 2: Depth Profiling via Sputter Etching

Objective: To determine the elemental composition as a function of depth from the surface.

- Initial Surface Analysis: First, acquire an AES survey spectrum from the untouched surface.

- Sputter Etching: Use a focused ion gun (typically Ar+) to sputter away the surface layer. The ion energy (e.g., 0.5 - 5 keV) and etching time determine the depth removed.

- In-situ Analysis: After a short sputtering interval, pause the ion beam and acquire new AES spectra (survey or multiplex for specific elements) from the newly exposed surface.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 (sputtering and analysis) cyclically until the desired depth is profiled.

- Data Processing: Convert the sputtering time to depth using a pre-calibrated sputter rate for the material. Plot the atomic concentration of each element (derived from Auger peak intensities) as a function of depth to create a depth profile graph [29] [30].

AES Analysis Workflow

Auger Electron Emission Process

In surface chemical analysis research, particularly in pharmaceutical development, no single analytical technique can provide a complete picture of a material's properties. Relying on one method often leads to ambiguous data, misinterpretation, and potential project delays. This technical support guide focuses on the integrated use of Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS), contact angle measurements, and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflection (FTIR-ATR) to overcome these challenges. These techniques provide complementary data: SIMS offers elemental and molecular surface composition, contact angle quantifies surface energy and wettability, and FTIR-ATR determines chemical functional groups and bonding. When used together, they form a powerful triad for comprehensive surface characterization, but each presents specific troubleshooting challenges that researchers must navigate to ensure data reliability [33] [34].

The following sections provide targeted troubleshooting guides, frequently asked questions, and practical protocols to help researchers overcome common experimental hurdles in surface analysis. By addressing these specific technical challenges, scientists can generate more robust and interpretable data for drug development applications, from characterizing drug delivery systems to optimizing implant surface treatments.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FTIR-ATR Troubleshooting

Problem: Inconsistent or distorted ATR spectra with unusual band ratios

- Question: Why are my FTIR-ATR spectral band intensities changing between measurements of the same material?

Answer: This common issue often stems from contact problems between the sample and the ATR crystal. For solid samples, especially rigid polymers, incomplete contact creates a microscopic air gap that differentially affects absorption bands. The evanescent wave's penetration depth is wavelength-dependent, being greater at longer wavelengths. With poor contact, shorter-wavelength absorptions are more severely attenuated. Solution: Ensure consistent, adequate pressure application using the ATR accessory's pressure mechanism. For very hard or fragile samples where sufficient contact is impossible, consider the advanced approach of modeling the gap using polarized measurements as a workaround [35] [36].

Question: Why do I get different relative peak intensities when I rotate my sample on the ATR crystal?

Answer: You are observing orientation effects from sample anisotropy. Manufacturing processes like extrusion or coating often create molecular alignment. In ATR spectroscopy, the effective pathlength differs for radiation polarized parallel (p-polarized) versus perpendicular (s-polarized) to the plane of incidence. This enhances vibrations with dipole changes in the plane of incidence. Solution: For qualitative identification, average multiple readings at different orientations. For quantitative analysis of oriented systems, use a polarizer and collect separate s- and p-polarized spectra to understand the orientation relationships [35].

Question: How does applied force affect my ATR measurements beyond just improving contact?

- Answer: Excessive force can induce physical changes in susceptible samples. In polymers, pressure can deform crystalline regions, altering crystallinity and shifting bands. Research shows polyethylene's CH₂ rocking bands at 730/720 cm⁻¹ change from two sharp peaks (crystalline) to a broader single band (amorphous) under pressure. Some minerals like kaolin exhibit >10 cm⁻¹ band shifts due to crystal lattice deformation. Solution: Use the minimum force necessary for good spectral quality and document the pressure used for reproducible results [35].

Problem: Unusual spectral baselines or unexpected peaks

- Question: Why do I see negative absorbance peaks in my ATR spectrum?

Answer: Negative peaks typically indicate a dirty ATR crystal or contamination from previous samples. The contaminant absorbs during background measurement but not during sample measurement, creating negative-going bands. Solution: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with appropriate solvents and acquire a fresh background spectrum. Implement regular crystal cleaning protocols, especially between different samples [37].

Question: Why is my ATR spectrum noisier than usual?

- Answer: Noise issues often stem from instrument vibrations or degraded optical components. FTIR spectrometers are highly sensitive to physical disturbances. Solution: Ensure the instrument is on a stable, vibration-damped surface. Check for nearby equipment like pumps or centrifuges that may cause interference. Allow sufficient instrument warm-up time and increase scan numbers if necessary while maintaining acceptable collection times [37].

Complementary Data Integration Troubleshooting

Problem: Contradictory results between techniques

- Question: My contact angle measurements indicate a hydrophilic surface, but FTIR-ATR shows predominantly hydrophobic functional groups. Why the discrepancy?

- Answer: This common contradiction highlights the different sampling depths of these techniques. Contact angle probes the outermost molecular layers (Ångstroms), while FTIR-ATR typically probes 0.5-2 μm at 1000 cm⁻¹. Your sample likely has a thin surface contamination or oxidation that modifies wettability but doesn't contribute significantly to the bulk-sensitive FTIR-ATR spectrum. Solution: Use SIMS, which is more surface-sensitive (1-3 monolayers), to characterize the outermost surface composition. Low-energy SIMS can detect thin contamination layers that explain the hydrophilic contact angle [33].

Problem: Quantitative inconsistencies in surface composition

- Question: How can I confirm whether my surface treatment produced a uniform coating?

- Answer: Use the technique triad complementarily: Contact angle provides rapid assessment of surface energy changes across multiple sample positions, FTIR-ATR identifies the chemical functionality of the coating, and SIMS maps the elemental/molecular distribution to confirm uniformity. Significant variations in contact angle measurements across the surface suggest non-uniform coating, which SIMS mapping can confirm. Solution: Always measure multiple sample positions with contact angle and FTIR-ATR, then use SIMS for micro-scale mapping of representative areas [34].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Integrated Surface Analysis Protocol

This protocol describes a systematic approach for comprehensive surface characterization of pharmaceutical materials using the three complementary techniques.

Sample Preparation:

- Clean samples thoroughly using appropriate solvents (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol) followed by oxygen plasma treatment or UV-ozone cleaning for organic removal

- For particulate samples, prepare smooth pellets using a hydraulic press when possible

- Document sample history including storage conditions and any pre-treatment

Contact Angle Measurements:

- Use a sessile drop method with ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

- Maintain constant temperature (±0.5°C) and humidity (±5%)

- Measure at least 5 drops per sample at different positions

- Include both advancing and receding angles for hysteresis analysis

- For time-dependent studies, capture images at 1-second intervals for 30 seconds

FTIR-ATR Analysis:

- Use diamond ATR crystal for most pharmaceutical materials

- Apply consistent pressure using the instrument's torque mechanism

- Collect spectra at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution with 64 scans for good signal-to-noise

- Acquire background spectra immediately before sample measurement under identical conditions

- For anisotropic materials, collect spectra at multiple orientations or use polarized light

SIMS Analysis:

- Select primary ions appropriate for your sample (Cs⁺ for negative polarity, O₂⁺ for positive polarity)

- Use low primary ion dose density (<10¹² ions/cm²) for static SIMS to preserve molecular information

- Acquire data from multiple areas to account for surface heterogeneity

- Use charge compensation for insulating samples