In-Situ Surface Passivation of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Techniques, Mechanisms, and Applications in Nanomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of in-situ surface passivation strategies for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical technology for enhancing their optoelectronic properties and stability.

In-Situ Surface Passivation of Perovskite Quantum Dots: Techniques, Mechanisms, and Applications in Nanomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of in-situ surface passivation strategies for perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical technology for enhancing their optoelectronic properties and stability. Aimed at researchers and scientists in materials science and drug development, we explore the foundational principles of surface defects and the necessity of passivation. The review details advanced methodological approaches, including ligand engineering, pseudohalide treatment, and epitaxial growth, highlighting their application in creating highly efficient and stable PQDs. We further address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as ligand lability and halide migration, and present rigorous validation techniques for assessing passivation efficacy. Finally, we discuss the transformative potential of well-passivated PQDs in biomedical applications, including biosensing, targeted drug delivery, and bio-imaging.

Unraveling the Need for Passivation: Surface Defects and Stability Challenges in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Inorganic halide perovskite quantum dots (IHPQDs), such as CsPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I), have emerged as pivotal materials for next-generation optoelectronic technologies due to their tunable optical properties, high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY), and defect-tolerant structures. [1] Despite their promising characteristics, the performance and stability of perovskite QDs are intrinsically limited by non-radiative recombination pathways originating from surface defects. These defects arise from the ultrahigh surface-area-to-volume ratio characteristic of quantum-confined nanostructures, where surface atoms constitute a significant fraction of the total material. [2]

The "soft" ionic nature of perovskite materials creates a dynamic surface equilibrium where ligands are constantly binding and detaching, leading to the formation of surface defects such as halide vacancies and under-coordinated lead atoms. [2] These defects create trap states within the bandgap that facilitate non-radiative recombination, whereby excited charge carriers relax without emitting photons, dissipating energy as heat instead. This process significantly reduces the internal quantum efficiency of light-emitting devices and contributes to accelerated degradation under operational conditions. [3] Understanding and mitigating these surface defects through advanced passivation strategies is therefore essential for realizing the full potential of perovskite QDs in optoelectronic applications.

Mechanisms of Non-Radiative Recombination at Surface Defects

Atomic Origin of Surface Defects

Surface defects in perovskite QDs primarily manifest as ionic vacancies and unpassivated surface sites. In lead halide perovskites, the most prevalent and detrimental defects are halide vacancies (particularly bromine vacancies in CsPbBr₃) which create shallow trap states that serve as efficient centers for non-radiative recombination. [3] These vacancies occur when the ionic lattice terminates abruptly at the QD surface, leaving under-coordinated atoms that disrupt the periodic potential of the crystal structure.

The problem is particularly pronounced on specific crystal facets. For instance, in PbS CQDs, non-polar <100> facets with S/Pb dual-terminations present a particular challenge for conventional passivation strategies that effectively passivate polar <111> facets with Pb atom-only termination. [4] Similarly, in CsPbBr₃ QDs, labile surface lattices and strong quantum confinement exacerbate the scale of exciton-surface lattice interactions, making the optical properties of small QDs especially prone to surface defect effects. [5]

Defect-Induced Photophysical Processes

Surface defect states introduce intermediate energy levels within the bandgap that dramatically alter the recombination dynamics of photogenerated charge carriers. The presence of these trap states enables several deleterious processes:

- Trap-Assisted Non-Radiative Recombination: Charge carriers are captured by defect states and recombine without photon emission, reducing PLQY and overall device efficiency. [3]

- Quantum Dot Photoionization: Surface defects trap photogenerated charge carriers, leaving the QD charged and enabling non-radiative Auger recombination for subsequently generated excitons. [5]

- Photoluminescence Blinking: The charging and discharging of QDs due to defect-mediated trapping and detrapping of carriers lead to stochastic intermittency in emission (blinking), a significant barrier for quantum light source applications. [5]

- Photodarkening: Photo-illumination can create additional defect states and induce surface ligand detachment, leading to irreversible degradation of optical properties over time. [5]

Table 1: Major Surface Defect Types and Their Impacts in Perovskite Quantum Dots

| Defect Type | Atomic Structure | Impact on Optoelectronic Properties | Preferred Passivation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halide Vacancies (VBr, VI) | Missing halide ions in crystal lattice | Creates shallow trap states; facilitates non-radiative recombination; reduces PLQY | Halide-rich ligands (PEABr, DDABr) [3] |

| Under-coordinated Pb atoms | Pb ions with incomplete coordination sphere | Acts as electron traps; promotes non-radiative decay | Lead-binding ligands (OA, OAm) [6] |

| Surface disorder | Amorphous regions at QD surface | Increases surface energy; enhances ion migration | Epitaxial ligand coverage [5] |

Advanced Surface Passivation Strategies

In Situ 2D Perovskite-like Ligand Passivation

A robust approach for passivating large and small-sized PbS quantum dots utilizes 2D neat perovskite (BA)₂PbI₄ as a surface engineering agent through an in situ solution-phase ligand-exchange strategy. [4] This treatment forms a thin shell of BA⁺ and I⁻ ions on the QD surface, enabling strong inward coordination that effectively reduces surface defect density, particularly on challenging non-polar <100> facets.

The methodology involves:

- QD Synthesis and Preparation: PbS CQDs with specific bandgaps (1.0 eV for large dots, 1.3 eV for small dots) are synthesized using standard colloidal methods.

- Ligand Exchange Solution Preparation: (BA)₂PbI₄ is prepared by reacting butylammonium iodide with lead iodide in a 2:1 molar ratio in dimethylformamide (DMF).

- In Situ Treatment: The PbS CQD solution is mixed with the (BA)₂PbI₄ solution at controlled stoichiometries and stirred for 6-12 hours at 60-80°C to allow complete ligand exchange.

- Purification: Treated QDs are purified via precipitation with antisolvents (typically toluene or hexane) and centrifugation at 6000-8000 rpm for 5-10 minutes.

This approach achieves impressive performance enhancements, with infrared solar cells employing (BA)₂PbI₄-capped large-sized PbS CQDs achieving power conversion efficiencies of 8.65%, while small-sized counterparts reach 13.1% PCE. [4]

Ligand Tail Engineering with π-π Stacking

For CsPbBr₃ QDs, a transformative strategy focuses on engineering ligand tails to promote attractive intermolecular interactions in the solid state. [5] Using phenethylammonium (PEA) ligands with low-steric tails enables π-π stacking that promotes the formation of a nearly epitaxial ligand layer, significantly reducing QD surface energy.

The experimental protocol comprises:

- Initial Surface Treatment: CsPbBr₃ QDs are first treated with n-butylammonium bromide (NBABr) to passivate halide vacancies.

- Ligand Exchange: Treated QDs are immersed in a saturated phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) solution in a 3:1 solvent mixture of hexane and octane.

- Thermal Annealing: The mixture is heated to 70-80°C for 10-30 minutes to enhance ligand binding and promote inter-ligand ordering.

- Solid-State Fabrication: QDs are deposited onto substrates via spin-coating or drop-casting for device integration.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirm that PEA-covered CsPbBr₃ surfaces reach minimum free energy when fully covered, with intermolecular π-π interactions driving near-epitaxial surface passivation. [5] Single QDs processed with this method exhibit nearly non-blinking emission with high single-photon purity (~98%) and extraordinary photostability, maintaining performance over 12 hours of continuous laser irradiation.

In Situ Epitaxial Quantum Dot Passivation

Core-shell structured perovskite QDs composed of methylammonium lead bromide (MAPbBr₃) cores and tetraoctylammonium lead bromide (tetra-OAPbBr₃) shells can be integrated during antisolvent-assisted crystallization of perovskite films for solar cell applications. [7] [8]

The detailed synthesis protocol:

- Core Precursor Preparation: 0.16 mmol methylammonium bromide (MABr) and 0.2 mmol lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂) are dissolved in 5 mL dimethylformamide (DMF) with 50 µL oleylamine and 0.5 mL oleic acid.

- Shell Precursor Solution: 0.16 mmol tetraoctylammonium bromide (t-OABr) is dissolved in 5 mL DMF following the same protocol.

- Nanoparticle Growth: 5 mL toluene is heated to 60°C in an oil bath, then 250 µL core precursor is rapidly injected.

- Shell Formation: A controlled amount of t-OABr-PbBr₃ precursor is injected, initiating core-shell structure formation (indicated by green coloration).

- Purification: After 5 minutes reaction, solution is centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes, precipitate discarded, supernatant collected and recentrifuged with isopropanol at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

This approach enables epitaxial compatibility between PQDs and the host perovskite matrix, effectively passivating grain boundaries and surface defects. [8] At optimal concentration (15 mg/mL), modified perovskite solar cells demonstrate remarkable PCE enhancement from 19.2% to 22.85%, with improved open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current density, and fill factor. [7]

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Advanced Surface Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Material System | Performance Improvement | Stability Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Perovskite-like Ligands | PbS CQDs (1.0 eV bg) | PCE: 8.65% in infrared photovoltaics [4] | Excellent ambient stability (hydrophobic BA+-rich surface) [4] |

| π-π Stacking Ligands | CsPbBr₃ QDs | Near non-blinking emission (>98% purity) [5] | 12 hours continuous operation; saturated excitation stability [5] |

| In Situ Epitaxial QD Passivation | MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr³ core-shell | PSC PCE: 19.2% → 22.85%; Voc: 1.120V → 1.137V [7] | >92% PCE retention after 900 h (vs. ~80% control) [7] |

| PEABr Treatment | CsPbBr₃ QD films | PLQY: 78.64%; Avg. PL lifetime: 45.71 ns [3] | Reduced surface roughness: 3.61 nm → 1.38 nm [3] |

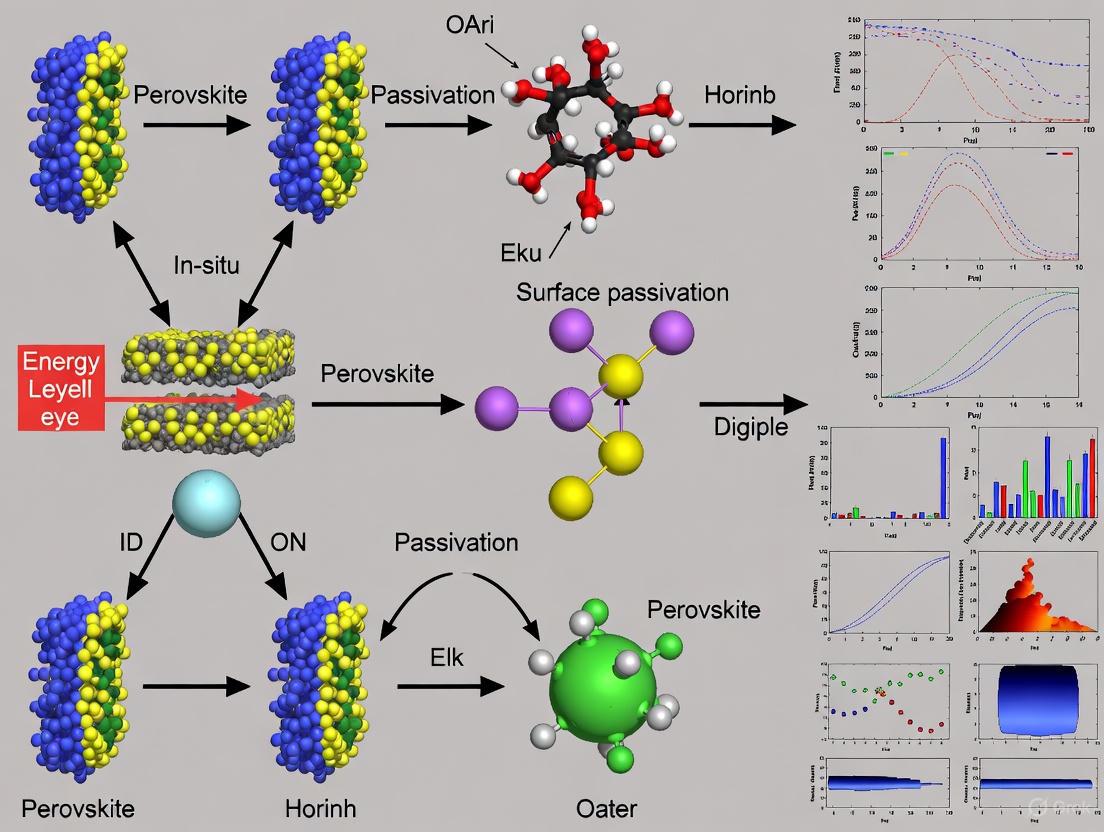

Visualization of Surface Passivation Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Surface Passivation of Perovskite QDs

| Reagent/Material | Chemical Function | Application Protocol | Impact on Surface Defects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Halide vacancy passivation; π-π stacking | Post-synthetic treatment of CsPbBr₃ QDs; saturation in hexane/octane [5] [3] | Suppresses non-radiative recombination; enables near-non-blinking emission [5] |

| Butylammonium-based 2D Perovskites | Facet-selective passivation | In situ ligand exchange during QD synthesis [4] | Passivates challenging non-polar <100> facets; reduces trap density [4] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | Binding to QD surfaces; defect passivation | Used during synthesis with optimized [OA]/[OAm] ratios [6] | Significantly improves PLQY by passivating surface defects [6] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Colloidal stability enhancement | Co-ligand with OAm during QD synthesis [6] | Improves QD stability without direct binding to surface [6] |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Shell formation for core-shell structures | Secondary injection after core QD formation [7] [8] | Creates epitaxial shells that suppress non-radiative surface recombination [7] |

| Methylammonium Bromide (MABr) | Core perovskite formation | Primary precursor in core-shell QD synthesis [8] | Forms high-quality core structures for subsequent passivation [8] |

The strategic engineering of surface chemistry represents a cornerstone in overcoming the fundamental challenge of non-radiative recombination in perovskite quantum dots. The advanced passivation methodologies detailed in this application note—ranging from in situ 2D perovskite-like ligands and π-π stacking phenethylammonium treatments to epitaxial core-shell quantum dot integration—demonstrate that rational surface design can effectively suppress defect-mediated recombination pathways.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on multifunctional ligand systems that simultaneously address halide vacancies, under-coordinated metal sites, and interfacial energy alignment while providing enhanced environmental stability. The integration of computational screening methods, including density functional theory and machine learning approaches, will accelerate the discovery of novel passivation molecules tailored to specific perovskite compositions and crystal facets. [2] Additionally, the development of green synthesis protocols utilizing environmentally benign solvents and ligands will be essential for sustainable commercialization of perovskite QD technologies. [1] As these surface engineering strategies mature, they will unlock the full potential of perovskite quantum dots for high-performance optoelectronic devices, including displays, lighting, photovoltaics, and quantum light sources.

The journey of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) from laboratory curiosities to commercial applications is significantly hampered by inherent instability issues. A primary source of this instability is the dynamic and labile nature of the surface-capping ligands, such as oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OAm), which are essential for colloidal stability and defect passivation. These ligands readily desorb from the QD surface during processing, film formation, or device operation, leading to the regeneration of surface defects, accelerated non-radiative recombination, and rapid degradation in the presence of environmental stressors like moisture. This Application Note examines the fundamental challenge of labile ligands and details advanced protocols, including bilateral interfacial passivation and the use of multi-anchoring binding molecules, to achieve robust in-situ surface passivation. The quantitative data and methodologies presented herein provide a roadmap for researchers to enhance the operational lifetime and efficiency of PQD-based optoelectronic devices.

Perovskite quantum dots, particularly lead halide perovskites (e.g., CsPbX₃, where X = Cl, Br, I), have garnered significant attention for their exceptional optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), tunable bandgaps, and narrow emission linewidths. However, their path to commercialization is fraught with challenges, predominantly centered on poor long-term stability. A critical, often overlooked, factor is the role of surface ligands.

These ligands, typically long-chain organic molecules like OA and OAm, perform a dual function: they passivate undercoordinated surface atoms (e.g., Pb²⁺ ions) to suppress non-radiative recombination, and they stabilize the colloidal suspension during synthesis. Unfortunately, the binding of these conventional ligands is often weak and non-specific. During post-synthesis processing—such as purification, film deposition, or thermal annealing—these ligands can readily detach or be displaced. This ligand lability results in:

- Defect Regeneration: The exposure of undercoordinated ions creates trap states that quench luminescence and reduce efficiency [9].

- Surface Reactivity: The newly exposed, ionic surface becomes highly susceptible to attack by ambient moisture and oxygen [10].

- Particle Aggregation: The loss of steric hindrance leads to QD aggregation, degrading film morphology and charge transport [11].

Consequently, developing strategies to anchor ligands more firmly to the QD surface is a cornerstone of modern perovskite research, aiming to convert these labile binding sites into stable, robust interfaces.

Quantitative Data on Ligand Impact and Passivation Efficacy

The following tables summarize quantitative findings from recent studies, highlighting the profound impact of ligand management on device performance and stability.

Table 1: Impact of Ligand Ratios on Double Perovskite QD Properties

| Ligand Ratio [OA]/[OAm] | Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | ~25% | Lower emission efficiency, suboptimal passivation |

| 1 | ~55% | Highest PLQY; balanced passivation and stability |

| 0.25 | ~30% | Reduced PLQY; insufficient OA impacts colloidal stability |

Source: Adapted from [11]. The study on Cs₂NaInCl₆ QDs found that only OAm was directly bound to the QD surface, responsible for defect passivation, while OA played a critical role in overall stability.

Table 2: Performance Enhancement from Advanced Passivation Strategies

| Passivation Strategy | Device Type | Key Performance Metric | Control Device | Passivated Device | Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral Interface (TSPO1) [9] | Green QLED | External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 7.7% | 18.7% | T₅₀ from 0.8h to 15.8h |

| Multi-site Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ [12] | Perovskite Solar Cell | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | ~23% (baseline) | 25.03% | T₈₀: 23,325 h (dark storage) |

| Core-Shell PQDs [13] | Perovskite Solar Cell | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 19.2% | 22.85% | >92% PCE retained after 900h |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Surface Passivation

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing two of the most promising strategies to overcome ligand lability.

Protocol: Bilateral Interfacial Passivation for QLEDs

This protocol, based on the work in [9], describes the passivation of both the top and bottom interfaces of a CsPbBr₃ QD film in a quantum dot light-emitting diode (QLED) structure.

- Objective: To suppress defect regeneration at the critical interfaces between the QD layer and the charge transport layers, thereby enhancing efficiency and operational stability.

Materials:

- Synthesized CsPbBr₃ QDs in non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane, octane).

- Passivation molecule solution: e.g., TSPO1 (diphenylphosphine oxide-4-(triphenylsilyl)phenyl) in anhydrous ethanol or isopropanol (0.5-2 mg/mL).

- Electron transport layer (ETL) materials (e.g., ZnO nanoparticles).

- Hole transport layer (HTL) materials (e.g., TFB, Poly-TPD).

- Pre-patterned ITO/glass substrates.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean ITO/glass substrates sequentially with detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol via sonication for 15 minutes each. Treat with UV-ozone plasma for 15-20 minutes.

- ETL Deposition: Spin-coat the ZnO nanoparticle solution onto the ITO substrate at 3000-4000 rpm for 30 s. Anneal at 100-120°C for 10-30 minutes in air.

- First (Bottom) Passivation Layer:

- Transfer the substrate into a nitrogen-filled glovebox.

- Deposit the TSPO1 solution onto the ZnO layer via spin-coating (3000-4000 rpm, 30 s) or thermal evaporation (1-2 Å/s to a thickness of 1-3 nm).

- QD Film Deposition:

- Spin-coat the CsPbBr₃ QD solution (e.g., 20-30 mg/mL in octane) onto the prepared substrate at 1500-2500 rpm for 20-30 s. This forms the emissive layer.

- Second (Top) Passivation Layer:

- Immediately after QD deposition, deposit the TSPO1 solution again using the same parameters as in Step 3, forming the top passivation layer.

- HTL and Electrode Completion:

- Spin-coat the HTL solution (e.g., TFB in toluene) onto the passivated QD film.

- Complete the device by thermally evaporating a MoO₃/Au or Ag anode.

- Key Considerations: The P=O group in TSPO1 has a strong binding affinity with undercoordinated Pb²⁺ on the QD surface, forming a stable complex that reduces trap states. The bilateral approach ensures both charge injection interfaces are optimized.

Protocol: In-Situ Integration of Core-Shell Perovskite Quantum Dots

This protocol, adapted from [13], involves the use of core-shell PQDs as additives during the antisolvent step of perovskite film fabrication for solar cells.

- Objective: To leverage epitaxially matched PQDs for grain boundary and surface defect passivation, improving photovoltaic performance and ambient stability.

Materials:

- Core-Shell PQDs: Pre-synthesized MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ PQDs dispersed in chlorobenzene (CB) at various concentrations (e.g., 3-30 mg/mL).

- Perovskite Precursor Solution: (e.g., 1.6 M PbI₂, 1.51 M FAI, 0.04 M PbBr₂, 0.33 M MACl, 0.04 M MABr in 1 mL of DMF:DMSO (8:1 v/v)).

- Substrate: FTO/c-TiO₂/mp-TiO₂.

- Antisolvent: Chlorobenzene (CB).

Procedure:

- PQD Synthesis (Brief):

- Synthesize MAPbBr₃ core QDs by injecting a precursor solution into hot toluene.

- Subsequently, inject a shell precursor (tetraoctylammonium bromide-PbBr₃) to form the core-shell structure.

- Purify via centrifugation and redisperse in CB to create a stable stock solution [13].

- Perovskite Film Fabrication with PQDs:

- Spin-coat the perovskite precursor solution onto the mp-TiO₂ substrate using a two-step program (e.g., 1000 rpm for 10 s, then 4000 rpm for 30 s).

- During the final 5-10 seconds of the second spin-coating step, dynamically drop-cast 200 µL of the PQD/CB antisolvent solution onto the spinning film.

- Immediately after spinning, anneal the film on a hotplate at 100°C for 10 min, followed by 150°C for 10-20 min.

- Device Completion: Continue with the standard deposition of the hole transport layer (e.g., Spiro-OMeTAD) and metal electrode (e.g., Au).

- PQD Synthesis (Brief):

- Key Considerations: The optimal concentration of PQDs is critical. At 15 mg/mL, the core-shell PQDs embed at grain boundaries, providing a lattice-matched passivation layer that inhibits ion migration and non-radiative recombination without impeding charge transport.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for In-Situ Passivation Research

| Reagent / Material | Chemical Formula / Example | Primary Function in Passivation |

|---|---|---|

| Oleylamine (OAm) | C₁₈H₃₅NH₂ | A common ligand; binds to QD surface, passivating defects and providing colloidal stability [11]. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | C₁₇H₃₃COOH | A common ligand; often works synergistically with OAm. Critical for maintaining solution stability of QDs [11]. |

| Phosphine Oxide Molecules | TSPO1 | Multi-dentate passivator; P=O group strongly coordinates with undercoordinated Pb²⁺, reducing trap states at interfaces [9]. |

| Inorganic Perovskite QDs | CsPbBr₃, CsPbI₃ | The core material of study; their ionic surface is prone to defect formation and ligand loss [9]. |

| Antimony-Based Complex | Sb(SU)₂Cl₃ | Multi-anchoring ligand; binds via Se and Cl atoms to multiple adjacent sites on the perovskite lattice, enabling superior stability [12]. |

| Core-Shell PQDs | MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ | Additive passivator; the shell provides a protective, epitaxial layer that passivates the core and enhances environmental stability [13]. |

Visualization of Passivation Strategies

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and mechanisms of the key passivation strategies discussed.

Diagram 1: From Problem to Solution. This workflow outlines the root cause of QD instability and logically connects it to three advanced research strategies aimed at mitigating the issue.

Diagram 2: Ligand Binding Modes and Outcomes. This diagram contrasts weak, single-site binding by traditional ligands with strong, multi-site or specific-interaction binding by advanced passivators, and their corresponding results on QD surface state.

The performance of quantum dot (QD)-based optoelectronic devices is intrinsically limited by surface defects that act as charge trapping sites, facilitating non-radiative recombination and degrading both efficiency and stability. In-situ passivation, defined as the integration of defect-passivating agents during QD synthesis or film formation, presents a transformative strategy to overcome these limitations. Unlike conventional ex-situ methods where passivation occurs after QD synthesis, in-situ approaches enable more uniform and thermodynamically favorable binding to nascent crystal surfaces, leading to superior defect suppression and enhanced material robustness [13] [14]. This Application Note delineates advanced protocols and provides a critical analysis of in-situ passivation techniques for perovskite and other QD systems, contextualized within a broader research framework aimed at achieving high-performance, industrially viable devices.

Experimental Approaches & Protocols

This section details specific methodologies for implementing in-situ passivation across different QD material systems.

In-Situ 2D Perovskite-like Ligand Exchange for PbS QDs

This protocol describes the formation of a robust 2D perovskite-like ligand shell on PbS CQDs during solution-phase ligand exchange, significantly enhancing passivation of non-polar facets and environmental stability [15].

- Primary Objective: To replace native oleic acid (OA) ligands with (BA)₂PbI₄ in situ, forming a thin shell of butylammonium (BA⁺) and iodide (I⁻) ions that passivate challenging non-polar <100> facets on PbS QDs.

- Materials:

- PbS-OA CQDs: Synthesized via hot-injection method, with exciton peaks at 933 nm (~1.3 eV) or 1180 nm (~1.0 eV) in n-octane [15].

- Lead Iodide (PbI₂): Serves as the lead and iodide source for the 2D perovskite ligand.

- n-Butylammonium Iodide (n-BAI): Provides the bulky organic cation for the 2D perovskite structure.

- Ammonium Acetate: Acts as a colloidal stabilizer during the ligand exchange process.

- Dimethylformamide (DMF): Polar solvent for the ligand exchange.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Disperse a stoichiometric mixture of PbI₂, n-BAI, and a small amount of ammonium acetate in DMF solvent. This forms the 2D perovskite precursor solution [15].

- Ligand Exchange: Inject the precursor solution into the PbS-OA CQD solution in n-octane. Vigorous stirring is required.

- Phase Transfer: The exchange process will cause the QDs to transfer from the non-polar n-octane phase to the polar DMF phase, indicating successful ligand replacement. The resulting QDs are denoted as PbS-(BA)₂PbI₄.

- Purification: Isolate the passivated QDs via centrifugation and redisperse in an appropriate solvent for film deposition.

- Critical Technical Notes: This method is versatile for both large- (1.0 eV) and small-bandgap (1.3 eV) PbS CQDs. The hydrophobic BA⁺-rich surface confers excellent ambient stability [15].

In-Situ Epitaxial Passivation with Core-Shell Perovskite QDs

This protocol involves the incorporation of pre-synthesized core-shell perovskite QDs during the antisolvent step of perovskite film formation, enabling epitaxial passivation of grain boundaries and surface defects [13].

- Primary Objective: To embed MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ core-shell PQDs into a bulk perovskite film during crystallization, passivating defects and suppressing non-radiative recombination.

- Materials:

- Core-Shell PQDs: Methylammonium lead bromide (MAPbBr₃) cores encapsulated by a shell of tetraoctylammonium lead bromide (tetra-OAPbBr₃), synthesized via colloidal synthesis and dispersed in chlorobenzene (CB) [13].

- Perovskite Precursor Solution: e.g., containing PbI₂, FAI, PbBr₂, MACl, MABr in a DMF:DMSO solvent mixture.

- Antisolvent: Chlorobenzene (CB).

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- PQD Synthesis: Synthesize core-shell PQDs by first injecting a MAPbBr₃ core precursor into heated toluene, followed by a controlled injection of the tetra-OAPbBr₃ shell precursor. Purify via centrifugation and redisperse in CB at a specific concentration (e.g., 15 mg/mL) [13].

- Film Fabrication: Deposit the perovskite precursor solution onto the substrate via a two-step spin-coating process (e.g., 2000 rpm for 10 s, then 6000 rpm for 30 s).

- In-Situ Integration: During the final seconds of the spin-coating process (e.g., last 18 s), introduce 200 µL of the PQD-CB solution as the antisolvent.

- Annealing: Thermally anneal the film to induce crystallization (e.g., 100°C for 10 min, then 150°C for 10 min). The core-shell PQDs become integrated at grain boundaries and surfaces during this process [13].

- Critical Technical Notes: The optimal concentration of PQDs is critical; 15 mg/mL was found to be effective. The epitaxial compatibility between the PQD shell and the host perovskite matrix is key to effective passivation.

Dual-Stage In-Situ Etching and Passivation for InP QDs

This protocol outlines a synthesis strategy for indium phosphide (InP) QDs that combines in-situ etching for defect removal with simultaneous surface passivation, achieving high photoluminescence quantum yield [14].

- Primary Objective: To synthesize high-performance green-emissive InP QDs by using an etchant during nucleation and shelling stages to achieve atomic-level defect passivation while preventing excessive etching.

- Materials:

- Zinc Fluoride (ZnF₂): Acts as the etchant during nucleation and shelling stages.

- Tri-n-octylphosphine (TOP): Serves as a ligand for nucleation control.

- Shell Precursors: For the growth of ZnSeS/ZnS multilayer shells.

- Carboxylic acid–thiol bifunctional ligands: For advanced surface modification post-synthesis.

- Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Nucleation with Etching: Conduct the nucleation of magic-sized InP clusters in the presence of ZnF₂ etchant and TOP ligands. The etchant removes surface oxides and defective layers, while TOP ligands control growth and suppress excessive etching [14].

- Shell Growth with Etching: Continue the use of ZnF₂ during the subsequent shell growth stages (ZnSeS/ZnS). This promotes a coherent interface and further passivates surface defects.

- Interfacial Engineering: A thin ZnSe interfacial layer is integrated to improve lattice matching between the InP core and the wider-bandgap ZnS shell.

- Surface Ligand Exchange: Perform a final surface modification with bifunctional ligands to enhance charge transport properties for device integration [14].

- Critical Technical Notes: The "etching–optical properties–surface passivation interdependence" must be carefully balanced. This approach effectively addresses long-standing challenges in controlling defects during InP QD synthesis.

Performance Data & Comparative Analysis

The following tables summarize the quantitative performance enhancements achieved by the in-situ passivation techniques detailed above.

Table 1: Photovoltaic performance of PbS QD solar cells with in-situ 2D perovskite-like ligand passivation. [15]

| QD Type (Bandgap) | Passivation Ligand | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Open-Circuit Voltage (VOC) | Short-Circuit Current Density (JSC) | Noted Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-sized (1.0 eV) | (BA)₂PbI₄ | 8.65% | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Excellent ambient stability |

| Large-sized (1.0 eV) | Control (PbI₂) | < 8.65% | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Lower stability |

| Small-sized (1.3 eV) | (BA)₂PbI₄ | 13.1% | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Significant thermal stability |

| Small-sized (1.3 eV) | Control (PbI₂) | 11.3% | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | Lower thermal stability |

Table 2: Performance enhancement of perovskite solar cells via in-situ epitaxial passivation with core-shell PQDs. [13]

| Device Parameter | Control Device | PQD-Passivated Device | Relative Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 19.2% | 22.85% | +19.0% |

| Open-Circuit Voltage (VOC) | 1.120 V | 1.137 V | +17 mV |

| Short-Circuit Current Density (JSC) | 24.5 mA/cm² | 26.1 mA/cm² | +1.6 mA/cm² |

| Fill Factor (FF) | 70.1% | 77.0% | +6.9% (absolute) |

| Stability (PCE retention after 900h) | ~80% | >92% | Significantly improved |

Table 3: Optical performance of InP-based QDs synthesized via in-situ etching and passivation. [14]

| Parameter | Performance Metric |

|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | 93% |

| Emission Linewidth (FWHM) | 36 nm |

| Maximum External Quantum Efficiency (in QLED) | 4.6% |

| Peak Maximum Luminance (in QLED) | >13,000 cd/m² |

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical progression and key components of the described in-situ passivation strategies.

In-Situ Passivation Workflow

Core-Shell PQD Passivation Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key research reagents for in-situ passivation strategies.

| Reagent/Material | Function in In-Situ Passivation | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| n-Butylammonium Iodide (n-BAI) | Spacer cation for forming 2D perovskite ligands; confers hydrophobicity and stability [15]. | 2D perovskite-like ligand for PbS QDs [15]. |

| Tetraoctylammonium Bromide (t-OABr) | Forms a wider-bandgap, hydrophobic shell around PQD cores, enhancing stability and passivation [13]. | Core-shell PQDs for epitaxial passivation [13]. |

| Zinc Fluoride (ZnF₂) | In-situ etchant that removes surface oxides and defective layers while providing Zn²⁺ for surface coordination [14]. | Dual-stage etching and passivation of InP QDs [14]. |

| Tri-n-octylphosphine (TOP) | Ligand that controls nucleation and growth, preventing excessive etching during synthesis [14]. | Nucleation control in InP QD synthesis [14]. |

| Ammonium Acetate | Colloidal stabilizer that assists in maintaining dispersion during ligand exchange processes [15]. | Solution-phase ligand exchange for PbS QDs [15]. |

In the advancement of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) research, particularly for in-situ surface passivation strategies, a multifaceted analytical approach is paramount. The performance and stability of these nanomaterials are critically dependent on their surface chemistry, where ligands and passivating molecules interact with the ionic crystal structure. This application note details the synergistic use of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to provide a comprehensive picture of surface interactions, ligand binding efficacy, and electronic structure modification. Framed within a broader thesis on in-situ passivation, these protocols offer researchers a robust toolkit for validating and refining surface engineering approaches in PQDs.

FTIR Spectroscopy: Probing Surface Ligand Binding

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a fundamental technique for identifying the chemical functional groups present on the PQD surface and characterizing the nature of their binding to the inorganic crystal lattice.

Application Protocol and Data Interpretation

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare purified and dried PQD powder (e.g., CsPbI3 or MAPbBr3). For transmission mode, homogenously mix ~1 mg of PQD powder with 100 mg of potassium bromide (KBr) and press into a pellet. For attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode, a small amount of pure PQD powder or film can be directly placed on the crystal.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire FTIR spectra in the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹. Collect and subtract a background spectrum of the empty KBr pellet or clean ATR crystal.

- Data Analysis: Identify characteristic vibrational modes of common ligands (e.g., oleic acid (OA), oleylamine (OAm)) and new passivating molecules. Key shifts in peak position or intensity compared to the free ligand indicate surface binding.

Table 1: Key FTIR Signatures for Common Perovskite Quantum Dot Ligands

| Functional Group / Ligand | Characteristic FTIR Peaks (cm⁻¹) | Interpretation of Surface Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) | C=O stretch: ~1710 (free acid) ~1500-1650 (carboxylate) | Shift from ~1710 to lower wavenumbers indicates deprotonation and coordination to Pb²⁺ sites [16] [17]. |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | N-H stretch: ~3300-3500 C-N stretch: ~1000-1200 | Broadening or weakening of N-H stretch suggests interaction with the perovskite surface [17]. |

| BODIPY-OH | C-O stretch, B-F stretch | Changes in intensity and position confirm ligand exchange and binding [17]. |

| TMeOPPO-p | P=O stretch: ~1100-1200 | Shift in P=O stretch confirms coordination with uncoordinated Pb²⁺ [18]. |

Key Findings from Literature

FTIR is crucial for verifying successful ligand exchange or passivation. For instance, in MAPbBr3 QDs passivated with BODIPY-OH dye molecules, FTIR confirmed the successful binding of the new ligand to the QD surface [17]. Similarly, after treating CsPbI3 QDs with the conjugated molecule PCBM, the significant reduction in C-H stretching modes (~2851 and 2921 cm⁻¹) confirmed the effective removal of long-chain native oleate ligands, which is a critical step for enhancing charge transport in photovoltaic devices [19].

NMR Spectroscopy: Unveiling the Local Electronic Environment

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides atomic-level insights into the local electronic structure and dynamics of atoms within the PQD, offering a unique ground-state perspective that complements optical spectroscopy.

Application Protocol and Data Interpretation

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve 5-10 mg of purified PQDs in 0.6 mL of deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl3, toluene-d8). Ensure the sample is fully dissolved and homogeneous.

- Data Acquisition: Conduct 1H NMR to study organic ligand surface coverage and dynamics. For direct analysis of the perovskite lattice, acquire 207Pb or 133Cs NMR spectra, which may require specialized probes due to low sensitivity.

- Data Analysis: For 1H NMR, compare chemical shifts and peak broadening with free ligand spectra. For 207Pb NMR, the chemical shift is highly sensitive to the local electronic density and structural confinement.

Table 2: NMR Nuclei and Their Utility in Perovskite Quantum Dot Analysis

| Nucleus | Information Revealed | Example Experimental Observation |

|---|---|---|

| 1H | Ligand surface coverage, dynamics, and binding. | Presence of specific peaks (e.g., from -OCH3 at δ 3.81) confirms the incorporation of passivating molecules like TMeOPPO-p on the QD surface [18]. |

| 31P | Direct detection of phosphorous-containing passivators. | A signal in 31P NMR of purified QDs confirms the presence of TMeOPPO-p, proving its interaction with the surface [18]. |

| 207Pb | Local electronic structure, quantum confinement effects, dynamic disorder. | Size-dependent chemical shift in CsPbBr3; suppression of this shift in hybrid MAPbBr3 at room temperature due to dynamic disorder from organic cations [20]. |

Key Findings from Literature

NMR challenges conventional assumptions about PQDs. While optical spectroscopy shows a blueshift with decreasing QD size due to quantum confinement, 207Pb NMR reveals that the local electronic structure at the Pb nucleus in hybrid perovskites (MAPbBr3, FAPbBr3) does not follow this trend at room temperature. This is attributed to dynamic disorder from the fluctuating organic cations, which masks the confinement effect. This effect is reversed when the cation motion is frozen at low temperatures, highlighting the power of NMR to decouple dynamic and quantum effects [20].

DFT Calculations: Predicting and Rationalizing Surface Interactions

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations provide a theoretical foundation for interpreting experimental data, allowing researchers to predict binding energies, electronic structures, and the efficacy of passivating molecules at an atomic level.

Computational Protocol

Workflow for Surface Passivation Studies:

- Model Construction: Build a slab model of the relevant PQD surface facet (e.g., (100), (111)) or a cluster model representing the QD surface site.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the structure of the bare surface and the surface with adsorbed passivating molecules to find the most stable configuration.

- Property Calculation:

- Calculate the projected density of states (PDOS) to identify the presence and origin of trap states (e.g., from uncoordinated Pb²⁺) and their passivation.

- Compute the binding energy (Eb) of the ligand to the surface: ( Eb = E{[PQD+Ligand]} - (E{[PQD]} + E{[Ligand]}) ).

- Analyze charge transfer and electronic density difference maps.

Key Findings from Literature

DFT is instrumental in rational ligand design. For example, calculations on the lattice-matched anchor TMeOPPO-p showed that its P=O and -OCH3 groups, with an interatomic distance of 6.5 Å, perfectly match the lattice spacing of CsPbI3 QDs. The PDOS analysis demonstrated that this multi-site anchoring completely eliminated the trap states associated with uncoordinated Pb²⁺, whereas single-site anchors only partially mitigated them [18]. In another study, DFT calculations revealed that the binding energy of oleylamine and oleic acid ligands to the surface of FA-rich CsxFA1-xPbI3 PQDs was stronger than to Cs-rich ones, directly explaining the composition-dependent thermal stability observed experimentally [21].

The Integrated Workflow: A Case Study on Lattice-Matched Anchoring

The true power of these techniques is realized when they are used in concert. The development of the TMeOPPO-p passivator provides an excellent case study.

Diagram: The integrated workflow for developing and validating surface passivation strategies for perovskite quantum dots, combining DFT design with experimental synthesis and characterization.

- DFT-Guided Design: The molecule TMeOPPO-p was designed with a interatomic distance of 6.5 Å between its binding oxygen atoms to match the CsPbI3 lattice spacing. PDOS calculations predicted the elimination of trap states via multi-site anchoring [18].

- FTIR and NMR Verification: Experimental FTIR showed a shift in the P=O stretch, confirming coordination. 1H and 31P NMR spectra directly verified the presence of TMeOPPO-p on the purified QD surface, proving successful passivation [18].

- Performance Outcome: This targeted passivation yielded CsPbI3 QDs with a near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 97% and enabled light-emitting diodes with an external quantum efficiency of up to 27% [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for In-Situ Surface Passivation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (OA) / Oleylamine (OAm) | Standard long-chain ligands for colloidal synthesis and stabilization. | Used in the initial LARP synthesis of CsPbBr3 and MAPbBr3 QDs [16] [17]. |

| Tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphine Oxide (TMeOPPO-p) | Lattice-matched multi-site anchor for defect passivation. | Passivated uncoordinated Pb²⁺ in CsPbI3 QDs, boosting PLQY and device efficiency [18]. |

| Phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) | Fullerene derivative for surface passivation and charge transport. | Integrated into CsPbI3 QD films to passivate defects and enhance charge extraction in solar cells [19]. |

| BODIPY-OH | Short-chain dye ligand for photocatalytic applications. | Used to passivate MAPbBr3 QDs, enabling efficient carrier separation and singlet oxygen generation [17]. |

| (BA)2PbI4 (2D Perovskite) | Robust ionic ligand for surface engineering. | Employed for in-situ ligand exchange on PbS QDs, improving passivation and ambient stability [4]. |

| Core-Shell PQDs (e.g., MAPbBr3@Tetra-OAPbBr3) | Epitaxial passivator for bulk films. | Added during perovskite solar cell fabrication to passivate grain boundaries and suppress non-radiative recombination [7]. |

The integration of FTIR, NMR, and DFT calculations forms a powerful, self-validating toolkit for advancing in-situ surface passivation in perovskite quantum dots. FTIR provides quick verification of chemical binding, NMR offers unparalleled insight into the local ground-state electronic structure and ligand dynamics, and DFT allows for the predictive design and theoretical understanding of passivating molecules. By applying these techniques in a synergistic manner, as demonstrated in the integrated workflow, researchers can move beyond trial-and-error approaches and rationally develop high-performance and stable perovskite quantum dot materials for optoelectronic devices, photocatalysis, and beyond.

Advanced Passivation Techniques: From Ligand Engineering to Epitaxial Growth

The pursuit of high-performance and stable optoelectronic devices based on colloidal quantum dots (CQDs) has been hampered by insufficient surface passivation, particularly on non-polar crystal facets prevalent in larger-sized nanocrystals. Traditional short-chain ligands like lead iodide (PbI₂) provide inadequate coverage and suffer from weak ionic nature, leaving devices vulnerable to environmental degradation and surface defect-mediated performance losses [4]. The emergence of 2D perovskite-like ligands represents a paradigm shift in surface engineering strategies, offering a robust, versatile solution for comprehensive facet passivation.

These advanced ligands form a thin, coherent shell around quantum dots through in-situ solution-phase ligand-exchange strategies. Unlike conventional ligands that struggle with non-polar facets, 2D perovskite-like ligands enable strong inward coordination that effectively reduces surface defect density while preventing CQD aggregation and fusion [4]. This approach leverages the structural integrity and hydrophobic properties of layered perovskite materials to create a protective barrier that enhances both performance and environmental stability. The resulting core-shell architecture combines the excellent optoelectronic properties of quantum dots with the stability of 2D perovskite materials, opening new possibilities for infrared photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, and other quantum-dot-based technologies.

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative assessments demonstrate the significant advantages of 2D perovskite-like ligands across various material systems and device configurations. The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved through this passivation strategy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Dot Devices with Different Ligand Strategies

| Material System | Ligand Type | Key Performance Metrics | Stability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-sized PbS CQDs (1.0 eV bandgap) | (BA)₂PbI₄ (2D perovskite) | PCE: 8.65% [4] | Excellent ambient stability (hydrophobic BA⁺-rich surface) [4] |

| Small-sized PbS CQDs (1.3 eV bandgap) | (BA)₂PbI₄ (2D perovskite) | PCE: 13.1% [4] | Significantly enhanced thermal stability [4] |

| Small-sized PbS CQDs (1.3 eV bandgap) | PbI₂ (control) | PCE: 11.3% [4] | Lower stability compared to 2D perovskite analogues [4] |

| CsPbBr₃ QDs | Phenethylammonium (PEA) with π-π stacking | Near-non-blinking single photon emission (~98% purity) [5] | Extraordinary photostability (12 hours continuous operation) [5] |

| Quasi-2D Perovskite LEDs | PPT ligand (conjugated) | EQE: 26.3% (average 22.9%) [22] | Half-life: ~220 hours (0.1 mA/cm²), 2.8 hours (12 mA/cm²) [22] |

The performance benefits extend beyond efficiency metrics to fundamental material properties. Ligands with attractive intermolecular interactions between low-steric ligand tails, such as π-π stacking in phenethylammonium (PEA) ligands, promote the formation of a nearly epitaxial ligand layer that significantly reduces quantum dot surface energy [5]. This structural arrangement enables remarkable photostability, with single CsPbBr₃ quantum dots maintaining nearly non-blinking photoluminescence emissions even under continuous laser irradiation for 12 hours [5].

Table 2: Impact of Ligand Structural Features on Passivation Efficacy

| Ligand Feature | Impact on Passivation | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| π-conjugation length | Suppresses ion transport and phase disproportionation [22] | Narrowed phase distribution in quasi-2D perovskite films [22] |

| Cross-sectional area | Controls lattice distortions and structural stability [22] | Enhanced radiative recombination efficiencies [22] |

| Nitrogen content | Dominant driver of structural distortions in 2D perovskites [23] | Machine learning prediction with 92.6% accuracy [23] |

| Hydrophobic moieties | Enhances ambient stability through moisture resistance [4] | BA⁺-rich surfaces maintaining performance in environmental conditions [4] |

Experimental Protocols

In-situ Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange for PbS CQDs

Principle: This protocol describes the formation of a thin shell of BA⁺ and I⁻ ions on PbS CQD surfaces via in-situ solution-phase ligand exchange, enabling strong inward coordination that effectively reduces surface defect density [4].

Materials:

- PbS CQDs: Synthesized with oleic acid ligands, bandgap tuned to 1.0 eV (large-sized) or 1.3 eV (small-sized) for infrared photovoltaics [4]

- (BA)₂PbI₄ precursor: Butylammonium iodide (BAI) and PbI₂ in appropriate stoichiometric ratio

- Solvents: Dimethylformamide (DMF), octane, and acetone (anhydrous grades)

- Substrates: Glass/ITO substrates for film deposition

Procedure:

- Prepare PbS CQD stock solution: Disperse PbS CQDs in octane at concentration of 20-30 mg/mL

- Synthesize (BA)₂PbI₄ ligand solution: Dissolve BAI and PbI₂ in DMF at 50°C with molar ratio 2:1, concentration 0.05-0.1 M

- Execute ligand exchange:

- Mix PbS CQD solution with (BA)₂PbI₄ solution at volume ratio 1:2

- Stir vigorously for 5-10 minutes at room temperature to facilitate complete ligand exchange

- Precipitate and purify:

- Add acetone (anti-solvent) at 2:1 volume ratio to precipitate exchanged CQDs

- Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes and discard supernatant

- Redisperse and process:

- Redisperse purified CQDs in appropriate solvent for film deposition

- Spin-coat onto substrates at 2000-3000 rpm for 30-60 seconds

- Anneal and characterize:

- Thermal anneal at 70-90°C for 10 minutes to remove residual solvent

- Characterize film quality, optical properties, and device performance

Troubleshooting:

- Aggregation issues: Optimize ligand concentration and mixing time

- Incomplete exchange: Ensure stoichiometric balance between native and new ligands

- Film non-uniformity: Adjust spin-coating parameters and solvent composition

Solid-State Ligand Engineering for Non-Blinking Perovskite QDs

Principle: This protocol utilizes attractive intermolecular interactions (π-π stacking) between low-steric ligand tails to promote formation of nearly epitaxial ligand layers that significantly reduce QD surface energy, enabling non-blinking single photon emission with high photostability [5].

Materials:

- CsPbBr₃ QDs: Synthesized via hot-injection method, size below exciton Bohr diameter for strong quantum confinement [5]

- Phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr): Purified by recrystallization before use

- n-butylammonium bromide (NBABr): For initial surface treatment

- Solvents: Toluene, hexane, and acetonitrile (anhydrous)

Procedure:

- Initial QD preparation:

- Synthesize CsPbBr₃ QDs with standard oleic acid/oleylamine ligands

- Purify by precipitation/redispersion cycle three times

- Primary ligand exchange:

- Treat QDs with excess NBABr in toluene at 50°C for 1 hour

- Precipitate with acetonitrile, centrifuge, and collect exchanged QDs

- Secondary PEA treatment:

- Immerse NBABr-treated QDs in saturated PEABr solution

- Heat at 60-70°C for 30 minutes to promote ligand tail stacking

- Solid-state immobilization:

- Deposit QDs on substrate by spin-coating or drop-casting

- Mild thermal treatment (50-60°C) to enhance inter-ligand π-π stacking

- Photostability assessment:

- Characterize single QD photoluminescence under continuous excitation

- Monitor blinking statistics and photodarkening resistance

Validation Metrics:

- Blinking suppression: Near-non-blinking behavior with >95% ON-time fraction [5]

- Photostability: Stable emission for >12 hours continuous operation [5]

- Single photon purity: ~98% purity in single photon emission [5]

Diagram 1: In-situ 2D Perovskite Ligand Exchange Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of replacing native ligands with 2D perovskite-like ligands to achieve comprehensive facet passivation and enhanced material properties [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 2D Perovskite-like Ligand Studies

| Reagent Solution | Composition | Function & Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butylammonium-based 2D Perovskite Precursor | (BA)₂PbI₄ in DMF or DMSO | Forms robust passivation shell on polar and non-polar facets [4] | Optimal for PbS CQDs in infrared photovoltaics [4] |

| π-Stacking Ligand Solution | Phenethylammonium bromide (PEABr) in toluene | Promotes epitaxial ligand coverage via π-π interactions [5] | Essential for non-blinking CsPbBr₃ QDs; requires thermal annealing [5] |

| Conjugated Ligand Systems | PPT or PPT' ligands with extended π-systems | Suppresses phase disproportionation in quasi-2D perovskites [22] | Enables narrow phase distribution in PeLEDs [22] |

| Anti-solvent QD Dispersion | CdSe/ZnS QDs in toluene | Enhances stability via electric field redistribution [24] | Used in LARP process for PeLEDs; 15 mg/mL concentration [24] |

| Machine Learning Screening Library | Curated dataset of 15 ligand descriptors | Predicts 2D perovskite formation with 92.6% accuracy [23] | Identifies nitrogen content as key distortion driver [23] |

Mechanism and Signaling Pathways

The exceptional passivation efficacy of 2D perovskite-like ligands stems from multifaceted mechanisms operating at both molecular and macroscopic scales. At the fundamental level, directional noncovalent interactions between ligand moieties drive self-assembly into coherent, epitaxial-like layers on quantum dot surfaces [25]. For aromatic ligands like phenethylammonium (PEA), π-π stacking between adjacent ligand tails creates attractive intermolecular forces that significantly reduce surface energy and enhance binding stability [5]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirm that ligand systems with attractive tail interactions achieve minimum surface energy at full coverage, unlike bulky aliphatic ligands where complete passivation is energetically forbidden [5].

The passivation mechanism proceeds through three coordinated pathways:

Facet-Selective Coordination: The 2D perovskite ligands exhibit strong inward coordination particularly on challenging non-polar <100> facets that exhibit S/Pb dual-terminations, which are prevalent in larger-sized CQDs and inadequately passivated by conventional ligands [4].

Ion Migration Suppression: Extended π-conjugation and increased cross-sectional area in designed ligand structures dramatically suppress ion transport by raising activation energy barriers for halide migration. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that conjugated ligands like PPT and PPT' require twice the free energy for I⁻ diffusion compared to conventional BA ligands [22].

Phase Distribution Control: In quasi-2D perovskite systems, tailored ligand structures kinetically inhibit phase disproportionation by modulating interlayer diffusion barriers, enabling narrow n-phase distributions that enhance radiative recombination efficiencies and emission color purity [22].

Diagram 2: Multi-pathway Mechanism of 2D Perovskite Ligand Passivation. This diagram illustrates how 2D perovskite-like ligands simultaneously address multiple degradation pathways through comprehensive surface passivation [4] [5] [22].

The structural parameters of organic ligands precisely control their passivation functionality through well-defined relationships. Machine learning analyses of 15 ligand descriptors have established that nitrogen content serves as the dominant driver of structural distortions in 2D perovskites, while hydrogen bonding and π-conjugation provide counterbalancing stabilization effects [23]. Increasing nitrogen atoms in ligand structures systematically reduces octahedral X-M-X angles while enhancing lattice distortions, enabling predictive design of passivation ligands with tailored optoelectronic properties [23].

Application Scope and Versatility

The 2D perovskite-like ligand strategy demonstrates remarkable versatility across diverse material systems and device architectures. In infrared photovoltaics, the approach enables high-performance PbS CQD solar cells with tunable bandgaps, achieving champion power conversion efficiencies of 13.1% for small-sized CQDs (1.3 eV bandgap) and 8.65% for large-sized CQDs (1.0 eV bandgap) [4]. The hydrophobic nature of BA⁺-rich surfaces confers excellent ambient stability, addressing a critical limitation of previous passivation strategies [4].

In light-emitting applications, ligand engineering enables unprecedented control over phase distribution in quasi-2D perovskite LEDs. Conjugated ligands with extended π-systems and tailored cross-sectional areas (PPT, PPT') suppress phase disproportionation, yielding devices with narrow emission profiles and exceptional external quantum efficiencies up to 26.3% [22]. The enhanced phase stability translates to improved operational lifetimes, with half-lives of approximately 220 hours at low current densities [22].

For quantum light sources, phenethylammonium ligands with optimized π-π stacking create nearly non-blinking CsPbBr₃ quantum dots with single-photon emission purity of ~98% [5]. The extraordinary photostability enables continuous operation for 12 hours under saturated excitation conditions, permitting detailed studies of size-dependent exciton radiative rates and emission linewidths at the single-particle level [5].

The ligand strategy further extends to nanowire architectures, where directional noncovalent interactions guide 1D anisotropic growth within the 2D crystal plane [25]. This bottom-up assembly approach yields quantum-well nanowires with robust exciton-photon coupling (Rabi splitting energies up to 700 meV) and enhanced lasing performance compared to exfoliated crystals [25].

Concluding Remarks

The development of 2D perovskite-like ligands represents a significant advancement in quantum dot surface engineering, transitioning from partial facet passivation to comprehensive interfacial control. The multi-faceted mechanism—combining facet-specific coordination, ion migration suppression, and phase distribution control—enables simultaneous enhancement of optoelectronic performance and environmental stability across diverse device platforms.

The integration of machine learning frameworks with experimental validation accelerates the discovery of optimized ligand structures, establishing quantitative correlations between molecular descriptors and functional properties [23]. This data-driven approach, combined with fundamental insights into intermolecular interactions and crystallization kinetics, provides a robust foundation for rational design of next-generation passivation materials.

As research progresses, the expanding library of 2D perovskite-like ligands promises to unlock new frontiers in quantum dot technology, from stable infrared photovoltaics to quantum light sources and neuromorphic computing elements. The precise control over surface chemistry and interface properties demonstrated by these advanced ligand systems establishes a versatile platform for developing high-performance, solution-processable optoelectronics with tailored functionality.

In the pursuit of high-performance and stable perovskite quantum dot (PeQD) optoelectronics, in-situ surface passivation has emerged as a critical frontier in materials engineering. The intrinsic ionic nature of metal halide perovskites facilitates remarkable optoelectronic properties but also predisposes them to halide ion migration, a primary degradation pathway that severely limits device longevity and performance under operational conditions. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in mixed-halide systems, such as CsPb(Br/I)₃, which are essential for achieving pure red emission as specified by the Rec. 2020 display standard [26].

Pseudohalide ions, particularly thiocyanate (SCN⁻), have recently demonstrated exceptional capabilities in suppressing this ion migration through robust surface coordination. Unlike conventional organic ligands that often exhibit weak binding and thermal instability, SCN⁻ ligands provide dual-coordination sites (sulfur and nitrogen) that strongly chelate undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites on the PeQD surface [26]. This passivation mechanism not only reduces surface defect densities but also directly inhibits the vacancy-mediated migration of halide ions, thereby enhancing both operational stability and optoelectronic performance. This Application Note details the protocols and mechanistic insights for implementing SCN⁻-based pseudohalide passivation in PeQD systems, providing a framework for advancing in-situ passivation strategies within perovskite research.

Mechanism of Action

The efficacy of SCN⁻ pseudohalide ligands in stabilizing PeQDs stems from their multifaceted interaction with the perovskite surface, which simultaneously addresses several key degradation pathways.

Chemical Bonding and Defect Passivation

Thiocyanate ions (SCN⁻) function as X-site substitutes in the perovskite lattice, binding strongly to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ surface sites. This interaction is characterized by a dual-coordination capability through both sulfur and nitrogen atoms, creating a more stable and energetically favorable surface complex compared to monodentate organic ligands [26]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that this strong chemisorption effectively fills halide vacancy sites, which are the primary channels for ion migration [26] [27]. The passivation mechanism reduces the formation energy of critical defects while eliminating mid-gap trap states that facilitate non-radiative recombination, thereby significantly enhancing photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) [26].

Suppression of Halide Migration

Halide ion migration in mixed-halide perovskites occurs via a vacancy-mediated mechanism under electric fields and illumination. The introduction of SCN⁻ ligands directly competes with this process through two complementary actions:

- Steric Blocking: The physical presence of strongly-bound SCN⁻ ions at surface vacancy sites reduces the available pathways for halide ion movement.

- Energetic Stabilization: The strong Pb-SCN bond reinforces the surface lattice structure, increasing the activation energy required for halide ion displacement and subsequent migration [26].

This suppression is critically important for maintaining spectral stability in mixed-halide PeLEDs, preventing the formation of iodide- and bromide-rich domains that lead to undesirable emission broadening and peak shifts [26].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of SCN⁻-Passivated PeQDs vs. Non-Passivated Controls

| Performance Parameter | SCN⁻-Passivated PeQDs | Pristine (Non-Passivated) PeQDs | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 22.1% [26] | Not Reported | Significant |

| Luminance (cd/m²) | 31,000 [26] | Not Reported | Significant |

| Operational Lifetime (T₅₀) | 1020 min [26] | ~204 min (estimated) | 5-fold [26] |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Significantly Enhanced [26] | Baseline | Substantial |

| Spectral Stability | Excellent [26] | Poor due to halide segregation | Drastic Improvement |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing pseudohalide passivation in PeQD synthesis and device fabrication, specifically adapted from the pioneering work on mixed-halide CsPb(Br/I)₃ systems [26].

In-Situ Etching and Passivation of CsPb(Br/I)₃ Quantum Dots

Principle: A post-synthesis treatment strategy simultaneously removes lead-rich surface defects and passivates the PeQD surface using pseudohalogen inorganic ligands dissolved in acetonitrile [26].

Materials:

- Precursor Salts: Cesium carbonate (Cs₂CO₃, 99.9%), lead iodide (PbI₂, 99.99%), lead bromide (PbBr₂, 99.99%)

- Solvents: 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), oleylamine (OLA, 80–90%), methyl acetate, ethyl acetate, acetonitrile

- Passivation Agents: Potassium thiocyanate (KSCN), Guanidinium thiocyanate (GASCN)

- Inert Atmosphere: Nitrogen or Argon gas

Procedure:

- PeQD Synthesis: Synthesize CsPbI₂Br QDs using a standard hot-injection method.

- Dissolve Cs₂CO₃ in OA and ODE at 120°C under nitrogen to form a Cs-oleate precursor.

- In a separate flask, dissolve PbI₂ and PbBr₂ in ODE, OA, and OLA at 120°C.

- Rapidly inject the Cs-oleate precursor into the lead salt solution at 170°C and react for 10 seconds.

- Cool the reaction mixture in an ice-water bath and precipitate the QDs by adding methyl acetate, followed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes [26].

- In-Situ Etching and Passivation:

- Re-disperse the purified PeQD precipitate in 5 mL of toluene.

- Prepare the passivation solution by dissolving KSCN or GASCN in acetonitrile (concentration range: 1-5 mg/mL).

- Add the passivation solution dropwise to the PeQD dispersion under vigorous stirring.

- Continue stirring for 20-30 minutes at room temperature to allow complete ligand exchange and surface reconstruction.

- Purify the passivated PeQDs by adding ethyl acetate and centrifuging at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the passivated QDs in non-polar solvents (e.g., octane, toluene) for film deposition [26].

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Solvent Choice: Acetonitrile is critical as it is non-coordinating and of low polarity, which gently etches lead-rich defects without damaging the QD core—unlike stronger coordinating solvents like DMF or DMSO [26].

- Ligand Concentration: Optimize the concentration of KSCN/GASCN to achieve maximum PLQY enhancement without inducing QD aggregation or dissolution.

- Reaction Time: Monitor the reaction time carefully; prolonged exposure to acetonitrile may degrade QD quality.

Bilateral Interfacial Passivation in QLED Devices

Principle: Enhance device performance and stability by passivating defect-rich interfaces between the QD layer and charge transport layers (CTLs) in a light-emitting diode (LED) structure [9].

Materials:

- Passivated PeQDs (from Protocol 3.1)

- Charge Transport Materials: PTAA (hole-injection layer), TiO₂ (electron-transport layer)

- Passivation Molecule: Diphenylphosphine oxide-4-(triphenylsilyl)phenyl (TSPO1) or similar phosphine oxide-based ligands [9].

Procedure:

- Device Fabrication:

- Pattern ITO-coated glass substrates and clean sequentially with detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol.

- Deposit a hole-injection layer (e.g., PTAA) by spin-coating.

- Bottom Interface Passivation: Evaporate a thin layer (~5 nm) of TSPO1 molecules onto the PTAA layer under high vacuum [9].

- Spin-coat the film of passivated PeQDs (from Protocol 3.1) onto the TSPO1 layer.

- Top Interface Passivation: Evaporate a second layer of TSPO1 molecules directly onto the QD film [9].

- Complete the device by depositing an electron-transport layer (e.g., TiO₂) and a metal cathode (e.g., Al) via thermal evaporation.

- Characterization:

- Perform current-density-voltage (J-V) measurements to determine key device parameters (EQE, luminance).

- Assess operational stability by tracking luminance decay over time under constant current bias.

Data Analysis and Validation

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm the effectiveness of pseudohalide passivation.

Structural and Optical Characterization

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Confirm uniform QD morphology, monodisperse size distribution, and high crystallinity with clear lattice fringes post-passivation [26].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Analyze phase purity and identify any lattice contraction or expansion due to SCN⁻ incorporation [26].

- Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Measure using an integrating sphere. SCN⁻ passivation typically results in a substantial increase in PLQY (e.g., from <50% to >80%) due to reduced non-radiative recombination [26] [9].

- Photoluminescence (PL) Lifetime: Perform time-resolved PL measurements. Passivated QDs exhibit a longer average PL lifetime, indicating suppressed trap-assisted recombination [3].

Device Performance Metrics

- Electroluminescence (EL) Spectra: Monitor EL spectral stability under constant current driving. Passivated devices show negligible peak shift or broadening, confirming suppressed halide segregation [26].

- External Quantum Efficiency (EQE): Characterize LED performance. Record significant improvements in peak EQE and luminance for passivated devices, as detailed in Table 1 [26].

- Operational Stability: Measure the device lifetime (T₅₀, time to 50% initial luminance) under constant current density. SCN⁻-passivated PeLEDs demonstrate a fivefold enhancement in T₅₀ compared to pristine devices (1020 min vs. ~204 min) [26].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pseudohalide Passivation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Thiocyanate (KSCN) | Inorganic pseudohalide passivator | Provides SCN⁻ anions; strong dual-site (S, N) coordination to Pb²⁺; enhances PLQY and stability [26]. |

| Guanidinium Thiocyanate (GASCN) | Organic cation pseudohalide passivator | Provides SCN⁻; GUA⁺ cation may offer additional lattice stabilization; often used with KSCN [26]. |

| Acetonitrile (Solvent) | Medium for etching & passivation | Non-coordinating, low polarity; selectively etches lead-rich defects without QD dissolution [26]. |

| Diphenylphosphine Oxide (TSPO1) | Bilateral interfacial passivator | Evaporable molecule; P=O group strongly binds surface Pb²⁺; reduces interfacial non-radiative recombination [9]. |

| Phenethylammonium Bromide (PEABr) | Short-chain surface ligand | Passivates Br⁻ vacancies; improves film morphology and conductivity; reduces current leakage [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

The implementation of SCN⁻ pseudohalide passivation represents a significant advancement in the in-situ surface engineering of perovskite quantum dots. By leveraging the strong, dual-coordination chemistry of thiocyanate ligands, researchers can effectively suppress the detrimental halide ion migration that plagues mixed-halide perovskites. The protocols outlined herein—encompassing synthesis, passivation, and device integration—provide a robust framework for achieving PeQD films and devices with markedly enhanced optoelectronic performance and operational stability. As the field progresses, the principles of targeted defect passivation established by SCN⁻ ligands will continue to inform the development of next-generation perovskite materials for a wide range of optoelectronic applications.

In-situ epitaxial quantum dot passivation represents a cutting-edge strategy for enhancing the performance and durability of perovskite solar cells (PSCs). This approach involves the integration of core-shell structured perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) directly during the fabrication process of the perovskite active layer [8] [13]. The epitaxial compatibility between these PQDs and the host perovskite matrix enables effective passivation of grain boundaries and surface defects, which are primary sites for non-radiative recombination and degradation initiation [8]. The core-shell architecture typically consists of a photoactive core (e.g., methylammonium lead bromide - MAPbBr3) encapsulated by a protective shell (e.g., tetraoctylammonium lead bromide - tetra-OAPbBr3), which synergistically suppresses charge recombination while enhancing environmental stability [8] [7].

The in-situ integration differentiates this approach from conventional ex situ methods where pre-synthesized QDs are applied to the perovskite surface. By incorporating PQDs during the antisolvent-assisted crystallization step, they become embedded within the evolving perovskite matrix, creating coherent interfaces and strong interfacial bonding [8] [13]. This integration mechanism facilitates more efficient charge transport and significantly reduces ion migration, addressing two critical challenges in perovskite photovoltaics. Research demonstrates that this advanced passivation strategy enables remarkable improvements in both power conversion efficiency and operational lifetime, positioning it as a promising development for next-generation perovskite optoelectronics [8].

Performance Data and Quantitative Analysis

The implementation of in-situ epitaxial quantum dot passivation yields substantial improvements across multiple photovoltaic parameters. The following table summarizes key performance enhancements achieved through this approach in perovskite solar cells:

Table 1: Photovoltaic performance parameters of PSCs with and without core-shell PQD passivation

| Performance Parameter | Control Device | PQD-Passivated Device | Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | 19.2% | 22.85% | +19.0% | [8] [7] [13] |

| Open-Circuit Voltage (Voc) | 1.120 V | 1.137 V | +0.017 V | [8] [13] |

| Short-Circuit Current Density (Jsc) | 24.5 mA/cm² | 26.1 mA/cm² | +1.6 mA/cm² | [8] [13] |

| Fill Factor (FF) | 70.1% | 77.0% | +6.9% | [8] [13] |

| Stability (PCE retention after 900h) | ~80% | >92% | +12% | [8] [7] |

The enhancement in photovoltaic performance originates from fundamental improvements in the material properties. Devices incorporating core-shell PQDs exhibit reduced trap-state density and prolonged carrier recombination lifetimes, indicating effective suppression of non-radiative recombination pathways [28]. Spectral response analysis via incident photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE) reveals enhanced photoresponse across the 400-750 nm wavelength range, contributing to the increased Jsc [8] [13].

Beyond conventional lead-based perovskites, passivation strategies applied to lead-free alternatives also demonstrate significant benefits. For instance, Cs₃Bi₂Br₉ PQDs passivated with didodecyldimethylammonium bromide (DDAB) and SiO₂ coating show remarkable stability retention, maintaining over 90% of their initial efficiency after 8 hours under ambient conditions [29]. This highlights the broad applicability of surface passivation approaches across different perovskite compositions.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Core-Shell Perovskite Quantum Dots

Objective: To synthesize MAPbBr₃@tetra-OAPbBr₃ core-shell PQDs for in-situ passivation of perovskite solar cells [8] [13].

Materials:

- Methylammonium bromide (MABr, 80 wt%)

- Lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂)

- Tetraoctylammonium bromide (t-OABr, 20 wt%)

- Dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Oleylamine

- Oleic acid

- Toluene

- Isopropanol

- Chlorobenzene

Procedure:

- Core Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 0.16 mmol MABr and 0.2 mmol PbBr₂ in 5 mL DMF under continuous stirring. Add 50 μL oleylamine and 0.5 mL oleic acid to form the final core precursor solution [8] [13].

- Shell Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 0.16 mmol t-OABr in 5 mL DMF following the same protocol used for the core precursor solution [8] [13].

- Quantum Dot Synthesis: Heat 5 mL toluene to 60°C in an oil bath under continuous stirring. Rapidly inject 250 μL of the core precursor solution into the heated toluene, initiating the formation of MAPbBr₃ nanoparticles [8] [13].

- Shell Formation: Inject a controlled amount of the t-OABr-PbBr₃ precursor solution into the reaction mixture. The development of core-shell nanoparticles is indicated by the emergence of a green color. Allow the reaction to proceed for 5 minutes [8] [13].

- Purification: Transfer the solution to a centrifuge tube. Centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes, discard the precipitate, and collect the supernatant. Perform additional centrifugation with isopropanol at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes [8] [13].

- Storage: Redisperse the final precipitate in chlorobenzene to ensure nanoparticle stability for subsequent applications [8] [13].

Quality Control: The successful formation of core-shell PQDs can be verified through optical characterization (photoluminescence emission peak), structural analysis (XRD), and morphological assessment (TEM) [8].

Fabrication of PQD-Passivated Perovskite Solar Cells

Objective: To integrate core-shell PQDs during the fabrication of perovskite solar cells for in-situ passivation [8] [13].

Materials:

- Fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrates

- TiO₂ paste (18NRT)

- PbI₂, FAI, PbBr₂, MACl, MABr

- Dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)