Electrospinning Synthesis of Stable Perovskite Quantum Dot Composites: Strategies for Biomedical and Drug Delivery Applications

This article comprehensively explores the synthesis of stable perovskite quantum dot (PQD) composites via electrospinning, a versatile technique for creating nanofibrous scaffolds.

Electrospinning Synthesis of Stable Perovskite Quantum Dot Composites: Strategies for Biomedical and Drug Delivery Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the synthesis of stable perovskite quantum dot (PQD) composites via electrospinning, a versatile technique for creating nanofibrous scaffolds. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of PQDs and electrospinning, detailing methodologies for composite fabrication and integration. The content addresses critical challenges in PQD stability and offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it examines the validation of composite performance and compares different material systems for advanced applications in drug delivery, biosensing, and tissue engineering, providing a roadmap for developing next-generation biomedical devices.

Understanding the Building Blocks: Principles of Electrospinning and Perovskite Quantum Dots

Electrospinning is a versatile and efficient technique for the fabrication of micro- and nanoscale fibers, distinguished by its ability to produce structures with high surface area, interconnected porosity, and tunable morphology [1] [2]. Since its initial development in the 1930s and resurgence in the late 20th century, electrospinning has garnered significant interest in fields ranging from biomedical engineering to advanced materials science [1] [3]. Its capacity to create fiber architectures that mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) makes it particularly valuable for developing biomimetic materials [2] [4].

This protocol outlines the fundamental principles and practical methodologies for electrospinning, with specific emphasis on the synthesis of stable perovskite quantum dot (PQD) composites. The integration of PQDs into electrospun nanofibers represents a promising strategy to enhance PQD stability while maintaining their exceptional optical properties, enabling applications in advanced anti-counterfeiting, LED devices, and biomedical imaging [5] [6].

Theoretical Foundations

The Electrospinning Process: Core Principles

Electrospinning operates on the principle of electrostatic force overcoming surface tension to create ultrafine fibers. The standard apparatus consists of four primary components: a high-voltage power supply, a solution storage unit (typically a syringe), an ejection device (needle), and a collection device [1] [2] [7].

The process initiates when a high voltage (typically several thousand to tens of thousands of volts) is applied to the polymer solution, creating a voltage differential between the needle and collector. This induces charge accumulation within the solution, forming a Taylor cone—a conical meniscus at the needle tip where electrostatic repulsion counteracts surface tension [1] [2]. Once the critical voltage is exceeded, a charged polymer jet is ejected from the Taylor cone apex and undergoes rapid, unstable whipping motions en route to the collector. This stretching and thinning action, coupled with solvent evaporation, produces solid micro- or nanoscale fibers that accumulate on the collector as a non-woven mat [1] [7].

Mechanism Visualization

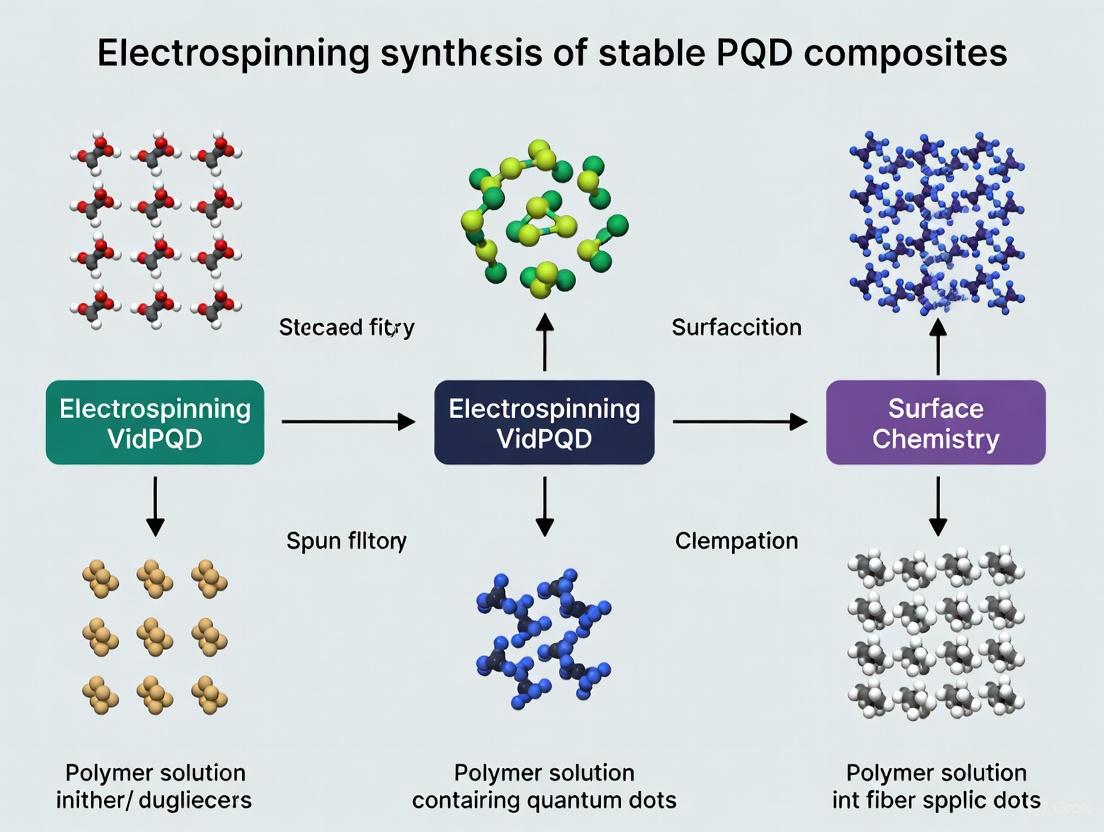

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental electrospinning process and the in-situ synthesis mechanism for PQD composites:

Factors Influencing Electrospinning

Electrospinning outcomes are governed by multiple interdependent parameters which can be categorized into solution properties, process parameters, and environmental conditions [1] [3] [2]. Understanding and optimizing these factors is crucial for producing fibers with desired characteristics for PQD encapsulation.

Key Processing Parameters

Table 1: Critical Electrospinning Parameters and Their Effects on Fiber Morphology

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Impact on Fiber Formation | Typical Range for PQD Composites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Properties | Polymer Concentration | Determines spinnability; affects fiber diameter and morphology [3] | Varies by polymer (e.g., 10-20% PAN) [6] |

| Viscosity | Influences jet stability and fiber diameter; too low causes bead formation, too high inhibits flow [3] | 1-20 Poise (dependent on polymer) [3] | |

| Conductivity | Affects jet elongation and fiber diameter; higher conductivity produces thinner fibers [1] | Adjust with salts or ionic additives | |

| Solvent Volatility | Impacts drying rate and fiber morphology; controls PQD crystallization [6] | DMF, DMF/DMSO mixtures [6] | |

| Process Parameters | Applied Voltage | Controls jet initiation and stretching force; affects fiber diameter [1] [2] | 10-25 kV [6] |

| Collection Distance | Influences solvent evaporation and fiber deposition; shorter distances may yield wet fibers [1] | 10-20 cm [6] | |

| Flow Rate | Determines solution feed rate; affects fiber diameter and morphology [2] | 0.5-3 mL/h [6] | |

| Collector Type | Controls fiber alignment and mat structure [1] [2] | Static plate, rotating drum | |

| Environmental Conditions | Temperature | Affects solvent evaporation rate and solution viscosity [2] | 20-30°C |

| Humidity | Influences solvent evaporation and fiber morphology; high humidity may cause pore formation [2] | 30-50% |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Electrospinning Protocol for PQD/PAN Composite Fibers

Based on: In Situ Synthesis of CsPbX₃/Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers [6]

Materials Preparation

- Precursor Solution: Dissolve 0.5 mmol PbX₂ and 0.5 mmol CsX (X = Cl, Br, I) in 10 mL DMF

- Polymer Addition: Add 1.0 g polyacrylonitrile (PAN, Mw ≈ 150,000) to the precursor solution under continuous stirring

- Solvent Adjustment: For chloride-containing precursors, use 5 mL DMSO with 5 mL DMF to enhance solubility

- Mixing Protocol: Stir the mixture for 6-12 hours at room temperature until a homogeneous, viscous solution forms

Electrospinning Procedure

Setup Configuration:

- Load the prepared solution into a syringe with a 20G stainless steel needle (0.51 mm diameter)

- Set needle-to-collector distance to 15 cm

- Use aluminum foil or rotating drum as collector

Process Execution:

- Apply fixed voltage of 15 kV to the needle

- Set solution flow rate to 2 mL/h using a syringe pump

- Maintain electrospinning duration for 2.5 hours to achieve uniform fiber mat

Post-Processing:

- Dry collected fibers in an oven at 60°C for 1 hour to remove residual solvents

- For enhanced PQD crystallization, additional heat treatment may be applied (80-100°C)

Advanced Protocol: Triple-Strand Conjugate Electrospinning for Multifunctional Composites

Based on: Fluorescent-Magnetic-Conductive Tri-Functional Nanofibrous Yarns [5]

This advanced technique enables integration of multiple functionalities while preventing detrimental interactions between different components:

Separate Solution Preparation:

- Fluorescent Strand: CsPbBr₃ PQDs/PAN solution (as in protocol 4.1)

- Magnetic Strand: CoFe₂O₄ nanoparticles (5-15% w/w) in PAN solution

- Conductive Strand: Polyaniline (PANI, 3-8% w/w) in PAN solution

Multi-Spinneret Configuration:

- Arrange three separate syringes in triangular configuration

- Apply synchronized voltage (12-18 kV) to all spinnerets

- Maintain individual flow control (1-3 mL/h per syringe)

Yarn Collection:

- Use rotating mandrel collector with controlled rotation speed (100-500 rpm)

- Apply slight twisting during collection to integrate three fiber types into unified yarn

- Adjust collector distance to 15-20 cm based on solvent system

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials for electrospinning PQD composite fibers:

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Electrospinning PQD Composites

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) | Primary fiber matrix; provides water stability and processability [6] | Excellent UV/weather resistance; Mw ≈ 150,000 recommended [6] |

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) | Water-soluble polymer for biomedical applications [7] | 8-16 wt% in aqueous solutions [7] | |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Biodegradable polymer for drug delivery [8] [7] | 4 wt% in appropriate solvents [7] | |

| PQD Precursors | Cesium Halides (CsBr, CsI, CsCl) | Cesium source for perovskite formation [6] | 0.5 mmol in 10 mL solvent typical [6] |

| Lead Halides (PbBr₂, PbI₂, PbCl₂) | Lead source for perovskite crystal structure [6] | Maintain 1:1 ratio with cesium precursors [6] | |

| Solvents | N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Primary solvent for precursor dissolution [6] | High boiling point (153°C) allows controlled crystallization |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Co-solvent for enhanced halide solubility [6] | Particularly useful for chloride-containing perovskites | |

| Functional Additives | CoFe₂O₄ Nanoparticles | Magnetic functionality [5] | 5-15% w/w in polymer solution [5] |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Conductive functionality [5] | 3-8% w/w in polymer solution [5] | |

| Oleic Acid/Oleylamine | Surface ligands for PQD stabilization [5] | Added during precursor preparation [5] |

Characterization and Performance Metrics

Structural and Optical Properties of PQD Composite Fibers

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of Electrospun PQD Composites

| Characterization Method | Key Findings | Performance Significance |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Distinct peaks matching CsPbBr₃ crystal structure (PDF#18-0364) [6] | Confirms successful PQD formation within fiber matrix |

| SEM/TEM Analysis | Uniform fiber morphology with diameter 746.56±13.12 nm [5] | Demonstrates process control and fiber uniformity |

| Photoluminescence (PL) | Strong green emission (520 nm) under UV excitation; 33× higher intensity than blended composites [5] | Validates spatial separation strategy for enhanced fluorescence |

| Water Stability Test | Retention of ~93.5% PL intensity after 100 days in water [6] | Critical for practical applications; demonstrates superior encapsulation |

| Lifetime Measurement | Tunable decay lifetimes dependent on halide composition [6] | Reflects PQD quality and environmental protection |

| Conductivity | Two orders of magnitude higher than blended composites [5] | Maintained conductive pathways through spatial separation of functions |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Experimental Challenges

The following workflow outlines systematic troubleshooting for typical electrospinning issues:

Optimization Strategies for PQD Composites

- Enhancing PQD Crystallinity: Optimize precursor concentration and thermal treatment conditions (60-100°C) to promote nanocrystal growth while maintaining spatial confinement [6]

- Improving Fiber Uniformity: Control environmental conditions (humidity 30-50%, temperature 20-30°C) to ensure consistent solvent evaporation rates [2]

- Increasing Production Yield: Scale-up using multi-needle configurations or free-surface electrospinning while maintaining fiber quality [1] [2]

- Enhancing Composite Stability: Employ core-shell designs or cross-linking strategies to improve mechanical integrity and environmental resistance [5] [6]

Applications and Future Directions

Electrospun PQD composite fibers demonstrate exceptional potential in multiple advanced applications. In lighting technology, CsPbBr₃/PAN composite films combined with K₂SiF₆:Mn⁴⁺ on blue LED chips produce stable white LEDs with color temperatures around 6000K and CIE coordinates of (0.318, 0.322) [6]. For anti-counterfeiting, the color-tunable luminescence across visible spectra enables sophisticated security patterns [6]. Advanced biomedical applications include multifunctional systems integrating fluorescence, magnetism, and conductivity for imaging and drug delivery [5].

Future developments will likely focus on intelligent processing techniques that combine electrospinning with 3D printing and microfluidics for precise spatial control [1] [2]. Green electrospinning approaches using benign solvents and melt processes address toxicity concerns while improving scalability [1] [2]. Multifunctional integration strategies, such as the triple-strand conjugate method, enable complex material systems with spatially separated functionalities for advanced optoelectronic and biomedical applications [5].

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly lead halide perovskites with the general formula APbX₃ (where A = Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺ and X = Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻), represent an emerging class of semiconductor nanomaterials that have revolutionized optoelectronics and biomedical research [9] [10]. These materials exhibit exceptional photophysical properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) approaching 99% in optimized samples, narrow emission linewidths (as low as 16-27 nm), and widely tunable emission spectra across the entire visible range (450-688 nm) through quantum confinement effects and compositional engineering [11] [12] [13]. Their unique crystal structure combines organic and inorganic components in a three-dimensional framework, enabling remarkable charge carrier mobility and optical absorption coefficients [9].

Despite their exceptional properties, PQDs face significant challenges in practical applications due to inherent structural instability under environmental stressors such as moisture, oxygen, heat, and UV irradiation [11]. This instability has prompted extensive research into encapsulation strategies, with electrospinning emerging as a powerful technique for creating stable PQD-polymer composites [14] [12] [15]. The integration of PQDs within electrospun polymer fibers not only shields them from environmental degradation but also enables the fabrication of flexible, lightweight, and functional materials for advanced optoelectronic and biomedical applications [13] [15].

Optoelectronic Properties and Tunability

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of PQDs stem from their unique electronic band structure and quantum confinement effects. The table below summarizes key optoelectronic parameters reported for various PQD systems:

Table 1: Optoelectronic Properties of Perovskite Quantum Dots

| PQD Composition | Emission Range | FWHM | PLQY | Stability Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsPbBr₃ | 507-517 nm | 16-27 nm | Up to 99% | Stable luminescence for 2.5 years | [15] [16] |

| CsPbX₃ (X=Cl,Br,I) | 450-688 nm | 22-27 nm | 53.8-82.3% | >90 days in water; UV, thermal stable | [11] [13] |

| FAPbX₃ (X=Cl,Br,I) | 450-625 nm | Narrow | Up to 82.3% | Improved stability in core-shell fibers | [11] |

| MAPbI₃ | ~780 nm | - | - | Thermal instability issues | [14] |

Bandgap engineering in PQDs is achieved through two primary approaches: compositional modulation (halide mixing, A-site cation substitution) and quantum confinement (size control) [9] [10]. Compositional tuning of the X-site halides (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) enables precise adjustment of the bandgap across the entire visible spectrum, with chloride-rich compositions emitting in the blue region and iodide-rich compositions emitting in the red and near-infrared [11] [13]. Simultaneously, varying the A-site cation (Cs⁺, MA⁺, FA⁺) influences the crystal stability and tolerance factor, with all-inorganic CsPbX₃ demonstrating superior thermal stability compared to hybrid organic-inorganic counterparts [14] [10].

Quantum confinement effects become prominent when the PQD size falls below the Bohr exciton diameter (approximately 7-12 nm for lead halide perovskites) [10]. This enables continuous tuning of the emission wavelength while maintaining narrow emission profiles, which is crucial for high-color-purity displays and lighting applications [13] [16]. Recent advances in synthesis have yielded CsPbBr₃ QDs with near-unity PLQY (99%) and extremely narrow FWHM (22 nm), representing state-of-the-art performance for green-emitting nanomaterials [16].

Electrospinning Synthesis of Stable PQD Composites

Electrospinning Methodology for PQD Encapsulation

Electrospinning has emerged as a versatile and scalable technique for encapsulating PQDs within polymer matrices to enhance their environmental stability while maintaining their exceptional optoelectronic properties [14] [12] [15]. This process utilizes high-voltage electrostatic fields to create fine fibers from polymer solutions containing PQD precursors or pre-synthesized PQDs [14]. The rapid solvent evaporation during fiber formation facilitates in situ crystallization of PQDs within the polymer matrix, effectively isolating them from environmental degradants [11] [15].

Table 2: Electrospinning Configurations for PQD-Polymer Composites

| Electrospinning Method | Polymer Matrix | PQD System | Key Advantages | Applications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-nozzle | PVP, PAN, PS | CsPbBr₃, MAPbI₃ | Simple setup, rapid fabrication | Fluorescent sensors, membranes | [14] [12] |

| Microfluidic core-shell | PS/PMMA | FAPbX₃ | Enhanced stability, tunable emission | Display technology, light conversion | [11] |

| Two-nozzle conjugate | PAN | CsPbX₃ | Continuous filament production | Weavable textiles, wearable devices | [13] |

| Triple-strand conjugate | PAN | CsPbBr₃/CoFe₂O₄/PANI | Multifunctional partitions | EMI shielding, smart textiles | [5] |

The electrospinning process involves several critical parameters that influence the resulting fiber morphology and PQD properties. Electrical voltage (typically 10-25 kV) determines the jet formation and fiber stretching, with higher voltages producing smaller fiber diameters but potentially increasing bead formation [14]. Collector type (planar vs. rotary) and rotation speed (500-750 rpm optimal for mechanical properties) control fiber alignment and orientation [14]. Solution parameters including polymer concentration (8-15%), viscosity, and solvent volatility significantly impact fiber morphology and PQD distribution within the fibers [14] [13].

Electrospinning Workflow for PQD-Polymer Composite Fibers

Protocol: Microfluidic Electrospinning of Core-Shell PQD Fibers

Objective: To fabricate stable, color-tunable FAPbX₃ (X = Cl, Br, I) PQDs embedded in polystyrene (core)-poly(methyl methacrylate) (shell) nanofibers with high quantum yield and environmental stability [11].

Materials:

- Precursor salts: Formamidinium halides (FACl, FABr, FAI), Lead halides (PbCl₂, PbBr₂, PbI₂)

- Polymers: Polystyrene (PS, Mw ~200,000), Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, Mw ~120,000)

- Solvents: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous), Tetrahydrofuran (THF)

- Ligands: Oleic acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm)

- Equipment: Microfluidic electrospinning setup, Syringe pumps (2), High-voltage power supply, Collector plate

Procedure:

- Core Solution Preparation: Dissolve PS (15% w/v) in DMF:THF (3:1 v/v) mixture. Add stoichiometric ratios of FABr (0.2 M) and PbBr₂ (0.2 M) to the polymer solution. Add OA (100 μL) and OAm (50 μL) as stabilizers. Stir vigorously for 4 hours at 60°C until fully dissolved.

- Shell Solution Preparation: Dissolve PMMA (12% w/v) in DMF alone to create a higher surface tension solution.

- Microfluidic Electrospinning Setup: Load core and shell solutions into separate syringes mounted on syringe pumps. Connect syringes to coaxial spinneret with core solution through inner needle (22G) and shell solution through outer needle (18G).

- Electrospinning Parameters: Set flow rates: core solution at 0.8 mL/h, shell solution at 1.2 mL/h. Apply voltage of 18 kV with working distance of 15 cm between spinneret and collector. Maintain temperature at 25°C and relative humidity below 30%.

- Fiber Collection: Collect fibers on aluminum foil-covered rotating mandrel (200 rpm). Anneal fibers at 80°C for 30 minutes to complete in situ crystallization of FAPbBr₃ PQDs at the core-shell interface.

- Characterization: Verify PQD formation by photoluminescence spectroscopy (emission ~520 nm for FAPbBr₃). Measure PLQY using integrating sphere (typically 70-82%).

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If bead formation occurs: Increase polymer concentration or reduce flow rate.

- If PQDs show broad emission: Optimize annealing temperature and precursor ratios.

- If fibers exhibit poor mechanical properties: Adjust core-to-shell flow rate ratio or increase molecular weight of polymer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Electrospinning Research

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Precursors | CsX (X=Cl, Br, I), PbX₂, MAX, FAX | Forms perovskite crystal structure | High purity (>99.9%) essential for optimal performance |

| Polymer Matrices | PVP, PAN, PS, PMMA, PVA | Encapsulates and stabilizes PQDs | Must be soluble in polar solvents; affects mechanical properties |

| Solvents | DMF, DMSO, THF, Toluene | Dissolves precursors and polymers | Anhydrous conditions critical for controlling crystallization |

| Ligands | Oleic Acid, Oleylamine, 2-Hexyldecanoic acid | Controls PQD growth and passivates surface | Affects PQD size, stability, and quantum yield |

| Additives | Acetate salts, n-Octylamine | Enhances precursor conversion, passivates defects | Improves reproducibility and optoelectronic properties |

Optoelectronic Applications

Light-Emitting Devices and Displays

PQD-embedded electrospun fibers have demonstrated exceptional potential for light-emitting applications, particularly in displays and solid-state lighting [11] [13]. The core-shell fiber architecture enables precise color tuning from blue to red emission (450-625 nm) with narrow FWHM (16-27 nm), achieving wide color gamuts exceeding 125% of NTSC standards [11]. The encapsulation of PQDs within polymer fibers significantly enhances operational stability, with PS/FAPbBr₃/PMMA core-shell nanofibers maintaining >79% fluorescence retention after 60 hours of continuous UV illumination and demonstrating excellent water resistance [11].

Recent advances in two-nozzle electrospinning have enabled the continuous production of CsPbX₃@PAN luminescent filaments suitable for weaving and knitting operations [13]. These filaments exhibit high PLQY (53.8%), exceptional stability in water (>90 days), and mechanical robustness (tensile strength up to 14.37 N after twisting), making them ideal for wearable displays and smart textiles [13]. The enhanced stability stems from the complete isolation of PQDs from environmental oxygen and moisture through the polymer matrix, effectively suppressing non-radiative recombination pathways [13] [15].

Photonic Memory and Neuromorphic Computing

PQDs have emerged as promising materials for next-generation memory technologies, including memristors and photonic memory devices [10]. The resistive switching behavior in PQD-based memory devices originates from ionic migration and charge trapping phenomena within the perovskite crystal structure [10]. When configured in cross-point arrays, these devices can simulate synaptic functions, implementing neuromorphic computing principles that transcend conventional von Neumann architecture limitations [10].

The quantum confinement effect in PQDs enables precise bandgap engineering, allowing optimization of the ON/OFF ratio in memristive devices [10]. Devices utilizing 2D perovskite (C₄H₉NH₃)₂PbI₄ with a larger bandgap (2.43 eV) demonstrated significantly higher ON/OFF ratios (10⁷) compared to 3D MAPbI₃ (10²) due to enhanced Schottky barrier formation [10]. Electrospun PQD-polymer composites offer additional advantages for flexible memory devices, combining the switching characteristics of perovskites with the mechanical flexibility and environmental stability of polymer matrices [10].

Biomedical Applications and Protocols

Fluorescent Sensors and Biosensing

Electrospun PQD composite fibers have demonstrated remarkable capabilities as fluorescent sensors for biomedical detection applications [12]. The high quantum yield (~91%), narrow emission linewidth (~16 nm), and excellent photostability of these materials enable ultrasensitive detection based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) mechanisms [12].

Protocol: FRET-based Biosensor Using CPBQDs/PS Fiber Membrane

Objective: To fabricate an ultrasensitive fluorescent sensor for detection of biomolecules using CsPbBr₃ QDs encapsulated in polystyrene (PS) fiber membranes [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrospinning apparatus with high-voltage power supply

- Polystyrene (Mw ~350,000)

- CsPbBr₃ precursor solution (CsBr, PbBr₂ in DMF)

- Aluminum foil collector

- Target analyte solutions (e.g., Rhodamine 6G, protein conjugates)

Procedure:

- Electrospinning Solution: Dissolve PS (20% w/v) in anhydrous DMF. Add CsBr (0.15 M) and PbBr₂ (0.15 M) to the polymer solution. Add 100 μL oleic acid and 50 μL oleylamine as stabilizers. Stir for 6 hours at 50°C until a homogeneous solution is obtained.

- Fiber Fabrication: Load solution into 5 mL syringe with 21G stainless steel needle. Set flow rate to 1.0 mL/h and apply voltage of 20 kV. Maintain working distance of 15 cm between needle and collector. Collect fibers on aluminum foil at ambient conditions (25°C, 30% RH).

- Post-treatment: Anneal fibers at 100°C for 10 minutes to complete CsPbBr₃ crystallization. Verify green emission under UV lamp (365 nm).

- Sensor Implementation: Cut fiber membrane into 1×1 cm pieces. Immerse in analyte solutions of varying concentrations. Measure fluorescence intensity changes using spectrofluorometer with 365 nm excitation.

- FRET Efficiency Calculation: Calculate FRET efficiency using the formula: E = 1 - (F_DA/F_D), where F_DA is donor fluorescence in presence of acceptor and F_D is donor fluorescence alone.

Performance Metrics: The CPBQDs/PS fiber membrane sensor demonstrated an ultralow detection limit of 0.01 ppm for Rhodamine 6G with FRET efficiency of 18.80% in 1 ppm R6G solution [12]. The sensor maintained 79.80% fluorescence retention after 60 hours of UV illumination and nearly 100% retention after 10 days in water [12].

FRET-based Sensing Mechanism in PQD-Composite Fibers

Photodynamic Therapy and Drug Delivery

The integration of PQDs within electrospun fibers has shown significant promise for photodynamic therapy (PDT) applications, leveraging their excellent light-harvesting capabilities and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation efficiency [17]. While most research has focused on porphyrin-based photosensitizers, preliminary studies indicate that perovskite materials exhibit similar potential for ROS generation upon light activation [17].

Protocol: PQD-Embedded Fibers for Potential Photodynamic Therapy

Objective: To develop PQD-incorporated core-shell fibers for localized ROS generation and drug delivery in biomedical applications [17].

Materials:

- Biocompatible polymers: PVA, Gelatin, PLGA

- CsPbBr₃ PQD solution (pre-synthesized)

- Model therapeutic agents (e.g., doxorubicin, curcumin)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- ROS detection reagents (e.g., Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green)

Procedure:

- Core Solution: Dissolve PVA (10% w/v) in deionized water at 80°C. Add pre-synthesized CsPbBr₃ PQDs (5 mg/mL) and therapeutic agent (1 mg/mL). Stir until homogeneous.

- Shell Solution: Dissolve gelatin (15% w/v) in acetic acid/water (80:20 v/v) mixture.

- Coaxial Electrospinning: Use coaxial spinneret with core flow rate 0.5 mL/h and shell flow rate 1.0 mL/h. Apply voltage 15 kV with collection distance 12 cm.

- Cross-linking: Expose fibers to glutaraldehyde vapor for 12 hours to cross-link gelatin shell.

- ROS Generation Testing: Immerse fibers in PBS containing Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (5 μM). Irradiate with blue light (450 nm, 100 mW/cm²) for varying durations. Measure fluorescence intensity at 525 nm (excitation 480 nm).

- Drug Release Profiling: Place fibers in PBS at 37°C with gentle shaking. Collect aliquots at predetermined time points and analyze drug concentration via HPLC.

Expected Outcomes: The core-shell structure provides sustained release of therapeutic agents while maintaining PQD stability and ROS generation capability. The system enables localized treatment with higher efficacy and reduced systemic toxicity compared to conventional administration [17].

The integration of perovskite quantum dots within electrospun polymer matrices represents a powerful strategy for overcoming the stability limitations of PQDs while leveraging their exceptional optoelectronic properties. The protocols and applications outlined in this document demonstrate the tremendous potential of these composite materials across optoelectronic and biomedical domains. Current research continues to address challenges in scalability, lead toxicity, and long-term stability under operational conditions. Future developments will likely focus on lead-free perovskite alternatives, advanced polymer matrices with enhanced barrier properties, and multifunctional systems combining sensing, therapy, and imaging capabilities within a single platform. As electrospinning methodologies advance toward continuous production and greater precision in fiber architecture, PQD-embedded composites are poised to enable transformative technologies in wearable optoelectronics, point-of-care diagnostics, and targeted therapeutic interventions.

Perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), particularly halide perovskite variants such as CsPbBr₃, have emerged as a revolutionary class of semiconducting nanomaterials with exceptional optoelectronic properties. Their high photoluminescence quantum yield, tunable emission wavelengths, and superior charge transport characteristics make them ideal for advanced applications in biosensing, light-emitting devices, and energy harvesting [18]. The stability challenge forms the central paradox of PQD technology: these materials exhibit phenomenal performance in controlled environments yet remain notoriously vulnerable to degradation under operational conditions.

The core instability issues stem from their inherent ionic crystal structure and high surface energy. PQDs are particularly susceptible to moisture, oxygen, light, and heat, which can rapidly degrade their crystalline structure and quench their optical properties [18]. Furthermore, lead-based PQDs face additional complications due to potential lead ion (Pb²⁺) leakage, raising significant toxicity concerns that create regulatory barriers for clinical applications, particularly in biomedical settings such as drug development or in vivo diagnostics [18]. These vulnerabilities necessitate the development of robust protective matrices that can shield PQDs from environmental stressors while maintaining their exceptional functionality, forming the critical research focus this application note addresses.

The Stability Challenge: A Systematic Analysis

The degradation pathways of PQDs are multifaceted and interconnected. Understanding these mechanisms is prerequisite to designing effective protective strategies.

Primary Degradation Pathways

- Aqueous-Phase Degradation: The ionic nature of perovskite crystals makes them highly susceptible to hydrolysis. Water molecules rapidly penetrate the crystal lattice, displacing halide anions and organic cations, leading to complete crystal dissolution over time [18]. Even brief exposure to ambient humidity can initiate this irreversible process.

- Photo-oxidation and Thermal Degradation: Under illumination, especially in the presence of oxygen, PQDs undergo a photo-catalyzed oxidation process that creates surface defects acting as non-radiative recombination centers [18]. Thermal stress similarly accelerates ion migration within the crystal lattice, destabilizing the quantum-confined structure.

- Ion Leaching and Toxicity: For lead-based PQDs like CsPbBr₃, the release of toxic Pb²⁺ ions presents a dual problem: it degrades the material's optical properties and creates environmental and health hazards [18]. This leaching phenomenon occurs particularly in aqueous environments and acidic conditions, severely limiting biomedical applications.

Quantifying the Stability Deficit

Table 1: Key Stability Limitations of Unprotected PQDs

| Stability Parameter | Typical Performance | Impact on Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Stability | Degradation within hours to days [18] | Limits biomedical, environmental sensing |

| Lead Leaching | Typically exceeds permitted levels for parenteral administration [18] | Barriers to clinical translation, toxicity concerns |

| Thermal Stability | Degradation above 60-80°C | Restricts processing conditions, device operation |

| Ambient Light Stability | Significant decay over days to weeks | Shortens device lifespan, reduces reliability |

The Electrospinning Solution: Encapsulation Strategies for PQDs

Electrospinning has emerged as a powerful and versatile technique for creating advanced composite materials that directly address PQD stability challenges. This electrohydrodynamic process creates continuous polymer fibers with diameters ranging from nanometers to micrometers, forming an ideal scaffold for PQD encapsulation [19] [20] [21].

Electrospinning Fundamentals for PQD Encapsulation

The basic electrospinning apparatus consists of high-voltage power supply, syringe pump with spinneret, and grounded collector [20] [21]. When a high voltage (typically 5-60 kV) is applied to the polymer solution containing dispersed PQDs, the electrostatic forces overcome surface tension to form a "Taylor cone" from which a charged jet is ejected. This jet undergoes stretching and whipping motions before solidifying into continuous fibers that deposit on the collector [21].

The core advantage for PQD protection lies in the complete encapsulation within the polymer matrix, creating a physical barrier that shields the quantum dots from environmental stressors while potentially allowing functional interaction with the environment through controlled porosity [19] [20].

Table 2: Electrospinning Parameters for Optimizing PQD-Polymer Composites

| Parameter Category | Key Variables | Influence on PQD Composite Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Parameters | Polymer concentration, viscosity, conductivity, PQD loading ratio [20] [22] | Determines fiber morphology, PQD distribution, and encapsulation efficiency |

| Process Parameters | Applied voltage, flow rate, needle-to-collector distance [21] [22] | Affects fiber diameter, alignment, and PQD degradation during processing |

| Environmental Parameters | Temperature, humidity [20] | Influences solvent evaporation rate and fiber solidification |

| Collector Design | Stationary plate, rotating drum [21] | Controls fiber alignment and mat morphology |

Material Selection for Protective Matrices

The choice of polymer matrix significantly influences both the protective capability and application functionality:

- Polyurethane (PU): Offers excellent flexibility, tear resistance, and biocompatibility, making it suitable for wearable sensors and biomedical applications [19].

- Polycaprolactone (PCL): A biodegradable polyester with good processability and biocompatibility, ideal for implantable devices and environmentally benign applications [23].

- Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA): Water-soluble, biodegradable polymer with high tensile strength, often blended with other polymers to modify properties [22].

- Lead-Free Alternatives: Bismuth-based PQDs (e.g., Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) demonstrate superior compatibility with biological systems and already meet current safety standards without additional coating requirements [18].

Experimental Protocols: Fabrication and Characterization of PQD-Composite Nanofibers

Protocol 1: Electrospinning of PQD-Polymer Composite Nanofibers

This protocol describes the fabrication of CsPbBr₃ PQD-polyurethane composite nanofibers for biosensing applications, adapted from established methodologies with PQD-specific modifications [19] [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Perovskite Quantum Dots: CsPbBr₃ PQDs synthesized via hot-injection method (10 mg/mL in toluene)

- Polymer Matrix: Polyurethane (PU) pellets (10% w/v in DMF/THF mixture)

- Solvent System: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) and tetrahydrofuran (THF) (7:3 v/v)

- Stabilization Additive: Oleic acid (0.1% v/v) and oleylamine (0.1% v/v) for surface passivation

Procedure:

- PQD Surface Functionalization: Pre-treat CsPbBr₃ PQDs with oleic acid and oleylamine (1:1 ratio) to enhance compatibility with the polymer matrix. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes and redisperse in minimal THF.

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve PU pellets in DMF/THF solvent system to achieve 10% w/v concentration. Stir continuously at 50°C for 6 hours until complete dissolution.

- Composite Solution Formulation: Slowly add functionalized PQD dispersion (final concentration: 2% w/w relative to polymer) to the polymer solution under gentle stirring. Maintain stirring for 2 hours at room temperature to achieve homogeneous dispersion.

- Electrospinning Parameters:

- Voltage: 15-18 kV

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/h

- Needle-to-collector distance: 15-20 cm

- Collector: Rotating drum (2000 rpm)

- Ambient conditions: 25°C, 40-50% relative humidity

- Fiber Collection: Collect composite nanofibers on aluminum foil-covered drum. Maintain electrospinning for 4-6 hours to achieve sufficient mat thickness (50-100 µm).

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If bead formation occurs, increase polymer concentration or reduce flow rate.

- If PQD aggregation is observed, enhance surface functionalization or reduce PQD loading.

- If fiber diameter is inconsistent, optimize humidity control and ensure stable temperature.

Protocol 2: Stability Assessment of PQD-Composite Nanofibers

This protocol provides standardized methods for evaluating the protective efficacy of electrospun matrices against environmental stressors [18].

Accelerated Aging Tests:

- Thermal Stability Assessment:

- Place composite samples in oven at 60°C, 80°C, and 100°C

- Measure photoluminescence (PL) intensity and full-width half-maximum (FWHM) at 24-hour intervals

- Compare with unprotected PQDs under identical conditions

Aqueous Stability Testing:

- Immerse composite mats in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C

- Measure PL quantum yield (PLQY) daily using integrating sphere

- Analyze supernatant for lead ion concentration via ICP-MS (for lead-based PQDs)

Photostability Evaluation:

- Subject samples to continuous illumination (450 nm, 100 mW/cm²)

- Monitor PL decay and color coordinate shifts over time

- Compare half-lives of protected versus unprotected PQDs

Characterization Techniques:

- SEM/TEM Imaging: Assess fiber morphology, diameter distribution, and PQD dispersion within fibers [24] [23]

- XRD Analysis: Monitor crystal structure changes before and after stress tests

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Detect chemical degradation or surface ligand displacement

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Quantify optical performance retention under various stressors

Application Performance and Validation

The practical efficacy of electrospun protective matrices is demonstrated through enhanced performance in real-world applications, particularly in biosensing and detection platforms.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Protected vs. Unprotected PQDs

| Application Context | Unprotected PQDs | Electrospun Matrix-Protected PQDs |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensing in Serum | Rapid degradation within hours [18] | Stable performance for weeks with appropriate polymer matrix [18] |

| Lead Leaching (CsPbBr₃) | Exceeds permitted levels for clinical use [18] | Below detection limits in PCL/PU matrices [18] [23] |

| Photoelectrochemical Sensing | Signal decay >80% in 24 hours | Maintains >90% initial sensitivity after 1 week [18] |

| Mechanical Flexibility | Brittle, prone to cracking | Excellent flexibility and durability in PU composites [19] |

Advanced material engineering has yielded particularly promising results:

- Dual-Mode Detection Systems: Electrospun composites incorporating PQDs have enabled lateral-flow assays combining fluorescence and electrochemiluminescence for sensitive Salmonella detection in food samples [18].

- Lead-Free Formulations: Bismuth-based PQDs (Cs₃Bi₂Br₉) incorporated in electrospun fibers demonstrate sub-femtomolar sensitivity for miRNA detection with extended serum stability, addressing both performance and toxicity concerns [18].

- Multiplexed Detection Platforms: Machine-learning-assisted fluorescent arrays using stabilized PQD-polymer composites achieve complete discrimination of multiple bacterial pathogens in complex matrices like tap water [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PQD-Composite Development

| Reagent/Category | Representative Examples | Function in PQD-Composite Development |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Polyurethane (PU), Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) [19] [23] [22] | Provides structural backbone, encapsulation, and mechanical properties |

| Solvent Systems | DMF, THF, Chloroform, DMAc [24] [23] | Dissolves polymer, enables PQD dispersion, controls evaporation rate |

| PQD Systems | CsPbBr₃, Cs₃Bi₂Br₉, MAPbI₃ [18] | Functional component providing optical/electronic properties |

| Surface Ligands | Oleic acid, Oleylamine, Polyacrylic acid [18] | Enhances PQD-polymer compatibility, reduces aggregation |

| Stabilization Additives | Silica precursors, Crosslinkers, Antioxidants | Improves environmental resilience, mechanical integrity |

| Conductive Fillers | Carbon nanotubes, Graphene, Metallic nanoparticles [19] [24] | Enhances electrical conductivity for sensing applications |

The integration of PQDs within electrospun polymer matrices represents a paradigm shift in addressing the fundamental stability challenges that have hindered the practical deployment of these exceptional nanomaterials. By creating tailored microenvironments that shield PQDs from environmental stressors while permitting functional interactions with target analytes, electrospun composites successfully balance the seemingly contradictory requirements of stability and functionality.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas:

- Advanced Material Systems: Development of multi-functional polymers that actively contribute to sensing mechanisms while providing protection.

- Scalable Manufacturing: Optimization of electrospinning parameters for industrial-scale production of PQD-composite materials.

- Accelerated Validation: Establishment of standardized testing protocols for rapid assessment of long-term stability under application-relevant conditions.

- Bio-Integration: Enhanced compatibility with biological systems through sophisticated surface engineering and biodegradable matrix materials.

As these developments progress, electrospun PQD composites are poised to enable a new generation of robust, sensitive, and reliable detection platforms that fully leverage the extraordinary optoelectronic properties of perovskite quantum dots while overcoming their historical limitations.

PQD Stabilization via Electrospinning

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), particularly cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX₃), have emerged as exceptional luminescent materials with superior optoelectronic properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission spectra, and tunable bandgaps [25] [26]. However, their widespread commercial application is severely hampered by intrinsic instability under environmental stressors such as moisture, heat, and oxygen. The susceptibility of PQDs to degradation leads to rapid fluorescence quenching, limiting their practical implementation in sensing, displays, and lighting technologies.

Electrospinning technology presents a sophisticated solution to this stability challenge through the encapsulation of PQDs within a protective polymer fiber matrix. This technique utilizes high-voltage electrostatic forces to draw polymer solutions into continuous micro- to nanoscale fibers, creating a three-dimensional porous network with high surface area [27] [1] [3]. When PQDs are incorporated into these fibers, the polymer matrix acts as a physical barrier, shielding the quantum dots from environmental degradation while preserving their exceptional optical properties. The synergistic combination of PQDs and electrospun fibers yields composite materials with enhanced environmental stability, mechanical integrity, and functionality for advanced applications in sensing, energy harvesting, and wearable technologies [28] [26].

Mechanisms of Stabilization and Encapsulation

The stabilization of PQDs within electrospun fibers occurs through multiple synergistic mechanisms that collectively preserve their optical functionality and structural integrity. The encapsulation process begins with the strategic integration of PQDs into the polymer solution prior to electrospinning. As the polymer jet travels toward the collector under high voltage (typically 10-30 kV), rapid solvent evaporation occurs, leading to the formation of solid fibers with PQDs uniformly distributed and securely embedded within the polymer matrix [26]. This physical confinement is crucial as it isolates individual PQDs, preventing aggregation and creating a barrier against penetrating moisture and oxygen molecules.

A critical advancement in PQD encapsulation involves surface ligand engineering to enhance compatibility between the quantum dots and the polymer matrix. Research demonstrates that exchanging native oleic acid ligands with methacrylic acid (MAA) significantly improves the dispersion stability of CdSe QDs in styrene-methyl methacrylate co-polymer systems [26]. The methacrylic acid ligands facilitate stronger interfacial interactions with the polymer chains and can potentially participate in polymerization reactions, leading to covalent anchoring of PQDs within the fiber matrix. This robust integration prevents PQD leaching and enhances overall composite stability.

The electrospinning process itself contributes to stabilization through the formation of a dense polymer skin around PQDs during fiber solidification. The rapid solvent evaporation and polymer chain alignment under electrostatic stretching create a compact microstructure with reduced permeability to environmental gases and vapors. This protective function is evidenced by the exceptional stability of CdSe@P(S+MMA) hybrid fibers, which maintain their photoluminescence output below 120°C and demonstrate excellent moisture and salt resistance [26]. The polymer matrix not only acts as a physical barrier but also reduces the mobility of PQD surfaces, effectively suppressing surface ion migration and associated degradation pathways.

Table 1: Stabilization Mechanisms of PQDs in Electrospun Fibers

| Mechanism | Process Description | Stabilization Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Encapsulation | Embedding PQDs within polymer fiber matrix during electrospinning | Creates barrier against moisture, oxygen, and thermal degradation |

| Ligand Engineering | Exchanging native ligands with polymer-compatible functional groups | Enhances dispersion and interfacial adhesion; prevents aggregation |

| Matrix Restriction | Polymer chains limiting PQD surface mobility and ion migration | Suppresses non-radiative recombination pathways; reduces PL quenching |

| Architectural Design | Engineering fiber porosity, diameter, and packing density | Controls analyte diffusion for sensing; balances protection and accessibility |

Quantitative Analysis of Stability Enhancement

Rigorous experimental investigations have quantified the stability enhancements achieved through electrospinning encapsulation. Comparative studies between bare PQDs and their electrospun composites reveal dramatic improvements in environmental resilience across multiple stress conditions.

Under thermal stress, CdSe@P(S+MMA) hybrid fibers maintain 79% of their initial photoluminescence intensity at 120°C, a temperature that would completely quench most unprotected PQDs [26]. While fluorescence signals decrease to 40%, 28%, 20%, and 13% at 140°C, 160°C, 180°C, and 200°C respectively due to chemical degradation of CdSe QDs, these values still represent significant protection compared to unencapsulated counterparts. The thermal protection mechanism arises from the high glass transition temperature of polymers like P(S+MMA) which form a rigid matrix that suppresses PQD decomposition pathways.

In humid environments, electrospun fibers provide exceptional moisture barrier properties. Research on CdSe QDs encapsulated in styrene-co-methyl methacrylate fibers demonstrated maintained luminescence and structural integrity even under high humidity conditions, a notable achievement given the extreme susceptibility of perovskite materials to hydrolysis [26]. The hydrophobic nature of many electrospinning polymers (e.g., PVDF, polystyrene, PMMA) creates a non-polar environment that repels water molecules and prevents hydration of the PQD crystal structure.

Chemical stability is similarly enhanced, with electrospun PQD composites showing resistance to salt solutions and other ionic environments that would typically degrade unprotected quantum dots [26]. The polymer matrix acts as an ion diffusion barrier, preventing corrosive species from reaching the encapsulated PQDs. This is particularly valuable for biomedical and environmental sensing applications where complex chemical environments are encountered.

Table 2: Quantitative Stability Performance of Electrospun PQD Composites

| Stress Condition | Performance Metric | Electrospun Composite | Unprotected PQDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal (120°C) | PL Intensity Retention | 79% [26] | Near complete quenching |

| Thermal (200°C) | PL Intensity Retention | 13% [26] | Complete degradation |

| Moisture Resistance | Structural integrity in humidity | Maintained [26] | Rapid decomposition |

| Chemical Stability | Resistance to salt solutions | Excellent [26] | Variable to poor |

| Operational Lifetime | Duration of functional performance | Weeks to months [26] | Hours to days |

Experimental Protocols for PQD Encapsulation

PQD Synthesis and Ligand Exchange Protocol

Materials Required:

- Cadmium oxide (CdO, 99.99%) and Selenium powder (Se, 99.99%)

- Oleic acid (OA, 90%) and Oleylamine (OAm, 80-90%)

- 1-octadecene (1-ODE, 90%) and Trioctylphosphine (TOP)

- Methacrylic acid (MAA) for ligand exchange

Synthesis Procedure:

- Cadmium Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 2.4 mmol CdO in 2.5 mL 1-ODE and 2.5 mL OA in a three-neck flask. Heat to 100°C under vacuum for 20 minutes, then increase temperature to 250°C under nitrogen atmosphere for 5 minutes to obtain cadmium oleate [26].

Selenium Precursor Preparation: Dissolve 1.2 mmol Se powder in 1 mL TOP under ultrasonic treatment at room temperature under inert atmosphere [26].

QD Synthesis: In a separate three-neck flask, combine 0.4 mL TOP-Se solution, 0.6 mL TOP, and 9 mL OAm. Degas under vacuum at 100°C for 20 minutes with stirring. When temperature reaches 275°C, rapidly inject 1 mL cadmium oleate solution under N₂ atmosphere. Stir for 4 minutes then cool immediately to room temperature [26].

Purification: Precipitate obtained CdSe QDs with methanol, centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 5 minutes, and dry under inert atmosphere [26].

Ligand Exchange: Dissolve 6.65 mmol dry CdSe QDs in 20 mL monomer mixture (e.g., styrene:methyl methacrylate). Add 70 μL methacrylic acid and maintain for 12 hours to complete oleic to methacrylic acid ligand exchange [26].

Diagram 1: PQD Synthesis and Functionalization Workflow

Electrospinning Encapsulation Protocol

Polymer Solution Preparation:

- Monomer Selection: Prepare a mixture of styrene and methyl methacrylate with varying volume ratios (10:0, 9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 6:4) to optimize polymer matrix properties [26].

In-situ Polymerization: Add 0.055 mmol AIBN initiator and 10 mL methyl acetate as solvent to the functionalized PQD-monomer solution. Heat on oil bath at 100°C for 2 hours for pre-polymerization, followed by 12 hours at 130°C to complete polymerization [26].

Solution Optimization: Adjust polymer concentration to achieve viscosity between 300-700 mPa·s, which is critical for successful electrospinning and optimal fiber morphology [27].

Electrospinning Parameters:

- Equipment Setup: Utilize a standard electrospinning apparatus with high-voltage power supply (0-30 kV), syringe pump, and grounded collector [1] [3].

Process Conditions:

Fiber Collection: Use aluminum foil as collector for random fiber orientation, or rotating drum for aligned fibers [1].

Diagram 2: Electrospinning Setup and Fiber Formation Process

Characterization and Validation Methods

Morphological Analysis:

- SEM Imaging: Characterize fiber diameter, surface morphology, and PQD distribution using scanning electron microscopy [26].

- TEM Analysis: Examine internal structure and PQD localization within fibers using transmission electron microscopy [26].

- Elemental Mapping: Confirm uniform PQD distribution using STEM-EDS elemental mapping [26].

Optical Performance:

- Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Measure emission spectra, quantum yield, and stability under environmental stress [26].

- UV-Vis Absorption: Record absorption characteristics of PQD solutions and composite fibers [26].

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Visualize spatial distribution of luminescence within fiber mats [26].

Stability Assessment:

- Thermal Testing: Monitor PL intensity retention at elevated temperatures (25-200°C) over time [26].

- Environmental Testing: Evaluate performance under controlled humidity (20-90% RH) and salt exposure [26].

- Long-term Stability: Measure optical properties over 30+ days under ambient and stressed conditions [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PQD Electrospinning

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium Oxide (CdO) | 99.99%, trace metals basis | PQD precursor for high-quality crystallization | Sigma-Aldrich [26] |

| Cesium Bromide (CsBr) | 99.9%, anhydrous | Perovskite component for CsPbBr₃ synthesis | Sigma-Aldrich [25] |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Technical grade, 90% | Native surface ligand for PQD stabilization | Aladdin [26] |

| Oleylamine (OAm) | 80-90% | Co-ligand for PQD synthesis and stabilization | Aladdin [26] |

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | 99% with stabilizer | Ligand exchange for polymer compatibility | Aladdin [26] |

| Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) | Mw = 150,000 g/mol | Polymer matrix for carbon nanofiber conversion | Merck [25] |

| Styrene (St) | Distilled under reduced pressure | Polymer matrix component | Aladdin [26] |

| Methyl Methacrylate (MMA) | 99% | Polymer matrix co-monomer | Aladdin [26] |

| Azodiisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | 98% | Radical initiator for polymerization | Sinopharm [26] |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Anhydrous, 99.8% | Solvent for electrospinning solutions | Sigma-Aldrich [25] |

Application Perspectives in Advanced Sensing Technologies

The enhanced stability of electrospun PQD composites enables their implementation in sophisticated sensing platforms across multiple domains. In healthcare monitoring, the exceptional luminescence properties of stabilized PQDs facilitate the development of highly sensitive biosensors. Research demonstrates that PQD-integrated composites can achieve detection limits as low as 0.03 fg mL⁻¹ for target analytes, showcasing their potential for diagnostic applications requiring extreme sensitivity [28] [25]. The porous fibrous architecture enhances analyte accessibility while maintaining protection of the sensing elements.

For environmental and wearable sensing, electrospun PQD composites offer mechanical flexibility alongside environmental resilience. The incorporation of CdSe QDs in styrene-methyl methacrylate co-polymer fibers has yielded materials with excellent moisture, heat, and salt resistance, enabling their use in protective clothing with sensing capabilities [26]. The thermal-induced photoluminescence quenching of these composites provides a measurable response to environmental changes, creating opportunities for smart textile applications.

In advanced analytical systems, the combination of electrospun PQD composites with electrochemical detection methods creates multimodal sensing platforms. The integration of PQDs with covalent organic frameworks (COFs) in nanofibrous structures enables both fluorescence and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) detection, significantly enhancing measurement reliability and reducing false positives [25]. This approach has demonstrated femtogram-level sensitivity for neurotransmitter detection in complex biological matrices like human serum, highlighting the translational potential of stabilized PQD composites in clinical diagnostics.

Electrospinning technology provides a robust and versatile platform for encapsulating and stabilizing Perovskite Quantum Dots, effectively addressing their primary limitation of environmental sensitivity. Through multiple synergistic mechanisms—including physical confinement, ligand engineering, and matrix restriction—electrospun polymer fibers preserve the exceptional optical properties of PQDs while imparting remarkable resistance to thermal, moisture, and chemical degradation. The standardized protocols presented herein enable reproducible fabrication of PQD-composite fibers with quantum yields up to 27% and operational stability under demanding conditions.

Future research should focus on expanding the library of compatible polymer matrices, developing scaled-up manufacturing processes, and exploring novel application paradigms in energy harvesting, advanced diagnostics, and smart materials. The continued refinement of interfacial engineering strategies and the integration of electrospinning with complementary nanofabrication techniques will further enhance performance and open new frontiers for PQD-based technologies in both academic research and industrial applications.

Electrospinning has emerged as a versatile and efficient technique for fabricating polymer nanofibers with diameters ranging from nanometers to several micrometers. These nanofibers exhibit remarkable characteristics, including very large surface area-to-volume ratios, flexibility in surface functionalities, and superior mechanical performance compared to other material forms [29]. When integrated with functional nanoparticles such as perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), these composite materials unlock transformative potential for advanced applications in drug delivery, sensing, and energy technologies. The electrospinning process utilizes a high-voltage electric field to draw charged threads from polymer solutions or melts, producing continuous fibers with tunable morphology, porosity, and composition [30] [2]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for material selection and experimental protocols for developing electrospun polymer-PQD composites, specifically contextualized within thesis research on synthesizing stable PQD composites.

The convergence of polymer science and quantum dot technology through electrospinning enables the creation of multifunctional materials with tailored optical, electronic, and biological properties. PQDs offer exceptional photoluminescence quantum yields, size-tunable emission wavelengths, and narrow emission bands, making them ideal for photonic applications. However, PQDs face challenges with environmental stability and aggregation that can be mitigated through proper encapsulation within polymer nanofibers. This document establishes standardized protocols for selecting appropriate polymer matrices, incorporating PQDs, and characterizing the resulting composites to achieve enhanced stability and performance for drug development and biomedical applications.

Polymer Selection for Electrospun Composites

Polymer Classification and Properties

The selection of an appropriate polymer matrix is fundamental to the successful fabrication of electrospun PQD composites. Polymers serve as the structural scaffold that determines the mechanical integrity, degradation profile, and processing parameters of the final composite material. Based on their origin and behavior, polymers for electrospinning can be categorized into natural, synthetic, and biodegradable classes, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications [2].

Natural polymers such as collagen, chitosan, and gelatin provide inherent biocompatibility and bioactive cues that support cellular interactions, making them ideal for tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. However, they often exhibit batch-to-batch variability and limited mechanical strength. Synthetic polymers including polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polyamide (PA) offer superior mechanical properties, tunable degradation rates, and reproducible manufacturing characteristics. Biodegradable polymers like polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and their copolymers (PLGA) provide temporary support with controlled resorption profiles, making them suitable for implantable drug delivery systems [30] [2].

The polymer selection must align with the intended application of the PQD composite. For drug delivery systems, polymers with tunable erosion rates and compatibility with therapeutic payloads are essential. For sensing applications, polymers with appropriate conductivity, optical properties, and stability under operating conditions are critical. The molecular weight of the polymer significantly influences solution viscosity and spinnability, with optimal concentrations typically yielding solutions with viscosities between 1-20 Pa·s for successful fiber formation [29] [2].

Table 1: Classification of Polymers for Electrospun Composites

| Polymer Category | Examples | Key Properties | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, Chitosan, Gelatin, Silk Fibroin | Excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, cellular recognition sites | Tissue engineering, wound healing, drug delivery | Batch variability, limited mechanical strength, complex processing |

| Synthetic Non-degradable | PVDF, PAN, Polyamide (PA), Polystyrene (PS) | Superior mechanical strength, chemical resistance, reproducible properties | Filtration, protective textiles, sensors, reinforcement | Non-degradable, potential chronic inflammation if implanted |

| Synthetic Biodegradable | PCL, PLA, PGA, PLGA | Tunable degradation rates, good mechanical properties, FDA approval for some formulations | Controlled drug delivery, temporary implants, tissue scaffolds | Acidic degradation products (for some), limited functional groups |

| Stimuli-Responsive | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), Chitosan derivatives | Response to pH, temperature, light, or magnetic fields | Smart drug delivery, sensors, actuators | Complex synthesis, potential toxicity of responsive units |

Quantitative Polymer Selection Guidelines

Selecting the optimal polymer for electrospinning requires careful consideration of multiple parameters that influence fiber morphology, composite performance, and processing feasibility. The following table provides quantitative data on key polymers used in electrospinning composites, particularly focusing on properties relevant to PQD incorporation and stability.

Table 2: Electrospinning Parameters and Performance of Selected Polymers

| Polymer | Typical Solvent System | Concentration Range (wt%) | Fiber Diameter Range (nm) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Degradation Time | Compatability with PQDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL | Chloroform/DMF (3:1) | 10-15 | 100-800 | 20-35 | 2-3 years | High - hydrophobic protection |

| PLA | Chloroform/DMF (4:1) | 8-12 | 200-1000 | 50-70 | 12-24 months | Medium - may cause quenching |

| PLGA | Chloroform/DMF (3:1) | 10-15 | 150-900 | 30-50 | 1-6 months (ratio dependent) | High - tunable compatibility |

| PAN | DMF | 8-12 | 150-600 | 100-250 | Non-degradable | Excellent - precursor for carbonization |

| PVDF | DMF/Acetone (3:2) | 15-20 | 200-1000 | 90-150 | Non-degradable | Medium - requires surface modification |

| Polyamide-6 | Formic Acid/Acetic Acid (1:1) | 18-22 | 100-500 | 200-400 | Non-degradable | High - good mechanical stability |

| Chitosan | Aqueous acetic acid (1-5%) | 2-7 | 80-400 | 50-100 | 1-3 months | Low - hydrophilic, may degrade PQDs |

When selecting polymers for PQD composites, consider the compatibility between the polymer's solubility and the PQD surface ligands. Polymers processed in non-polar solvents often provide better compatibility with oleic acid/oleylamine-capped PQDs, while hydrophilic polymers may require ligand exchange or surface modification of PQDs. Additionally, the polymer's optical properties should be considered—UV-absorbing polymers may interfere with PQD photoluminescence, while transparent polymers allow optimal light emission.

Perovskite Quantum Dot (PQD) Integration Strategies

PQD Selection and Stabilization

Perovskite quantum dots, particularly lead halide perovskites (CsPbX₃, where X = Cl, Br, I), offer exceptional optical properties including high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), narrow emission bandwidth, and easily tunable emission wavelengths across the visible spectrum. However, their susceptibility to moisture, oxygen, and heat presents significant challenges for practical applications. Successful integration into electrospun composites requires careful PQD selection and stabilization strategies.

The stability of PQDs can be enhanced through several approaches prior to electrospinning: (1) Surface ligand engineering using longer-chain ligands or mixed ligand systems to enhance binding affinity; (2) Ion doping with elements such as Mn²⁺, Zn²⁺, or Cu²⁺ to improve crystallinity and environmental stability; (3) Surface encapsulation with oxides (SiO₂, Al₂O₃) or polymers to create protective barriers; and (4) Compositional engineering using mixed halide or cation systems to achieve phase stability [31].

For biomedical applications, particularly drug delivery, additional considerations include reducing potential lead leakage through lead-free alternatives (such as CsSnX₃, Cs₂AgBiX₆ double perovskites) or implementing encapsulation strategies that completely isolate PQDs from the biological environment. The emission characteristics should be selected based on the application requirements—blue-emitting PQDs for optogenetics, green-red emitting for imaging, and near-infrared for deep tissue penetration.

PQD-Polymer Composite Fabrication Methods

Several electrospinning techniques can be employed to create polymer-PQD composites, each offering distinct advantages for different application requirements:

Blend Electrospinning: PQDs are uniformly dispersed in the polymer solution before electrospinning. This method offers simplicity and high loading capacity but may expose PQDs to solvent interactions and result in heterogeneous distribution. Optimal dispersion is achieved through probe sonication (30-60 seconds at 20-30% amplitude) followed by magnetic stirring (2-4 hours). Solvent selection is critical—non-polar solvents like toluene or hexane may be required for PQD stability, though they limit polymer choices.

Coaxial Electrospinning: Utilizes a specialized spinneret with concentric nozzles to create core-shell fibers where PQDs can be localized in either the core or shell layer [30]. This technique provides superior protection for PQDs, especially when encapsulated in the core, and enables controlled release kinetics for drug delivery applications. Core-shell fibers typically require precise control of flow rates (core: 0.1-0.5 mL/h, shell: 0.5-1.5 mL/h) and voltage parameters (15-25 kV).

Emulsion Electrospinning: PQDs are suspended in an immiscible polymer solution to create an emulsion that is subsequently electrospun [30]. This method is particularly useful for hydrophilic PQDs in hydrophobic polymer matrices and can enhance the distribution control of multiple components (drugs, imaging agents).

Post-processing Integration: PQDs are incorporated into pre-formed electrospun fibers through infiltration, dip-coating, or in-situ growth. This approach completely avoids exposing PQDs to harsh processing solvents but may result in surface-loaded composites with potential leaching issues.

Table 3: Comparison of PQD Incorporation Methods in Electrospun Composites

| Method | PQD Loading Efficiency | Distribution Control | PQD Protection | Process Complexity | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blend Electrospinning | High (70-90%) | Limited - random dispersion | Moderate - solvent exposure | Low | Rapid screening, high throughput |

| Coaxial Electrospinning | Medium (50-80%) | High - precise compartmentalization | Excellent - complete encapsulation | High | Biomedical applications, controlled release |

| Emulsion Electrospinning | Medium-High (60-85%) | Medium - domain-specific localization | Good - limited solvent contact | Medium | Multi-functional composites |

| Post-processing Integration | Low-Medium (30-70%) | Low - surface accumulation | Poor - surface exposure | Low-Medium | Heat-sensitive PQDs |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Blend Electrospinning of PLGA-PQD Composite Fibers for Drug Delivery

This protocol describes the preparation of composite fibers containing poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and perovskite quantum dots for theranostic applications (combined therapy and imaging).

Materials:

- PLGA (50:50 LA:GA ratio, MW 50,000-75,000)

- CsPbBr₃ PQDs (10 mg/mL in toluene)

- Chloroform (anhydrous, ≥99%)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous)

- Model drug compound (e.g., doxorubicin hydrochloride)

- Deionized water

Equipment:

- Electrospinning apparatus with high-voltage power supply (0-30 kV)

- Syringe pump

- Stainless steel spinneret (21-25 gauge)

- Grounded collector (stationary or rotating)

- Environmental control chamber (optional)

- Ultrasonic processor

Procedure:

Polymer Solution Preparation

- Dissolve PLGA in chloroform:DMF (3:1 v/v) at 12% w/v concentration

- Stir magnetically at 400 rpm for 4-6 hours until complete dissolution

- For drug-loaded fibers, add model drug (5-10% w/w relative to polymer) and stir for additional 2 hours

PQD Incorporation

- Add PQD solution (0.5-2% w/w relative to polymer) to the polymer solution

- Use probe sonication at 25% amplitude for 30 seconds to disperse PQDs

- Continue magnetic stirring at 300 rpm for 2 hours in dark conditions

Electrospinning Parameters

- Load solution into syringe with metallic needle (21G)

- Set flow rate: 0.8-1.2 mL/h

- Apply voltage: 15-20 kV

- Collection distance: 12-18 cm

- Use rotating mandrel (500-1000 rpm) for aligned fibers or static collector for random orientation

- Maintain environmental conditions at 25±2°C and 40±5% relative humidity

Fiber Collection and Storage

- Carefully peel fibers from collector

- Store in desiccator under nitrogen atmosphere at 4°C

- Shield from light to prevent PQD degradation

Troubleshooting:

- Bead formation: Increase polymer concentration or reduce flow rate

- PQD aggregation: Reduce PQD concentration or increase sonication time

- Inconsistent fiber diameter: Maintain stable temperature and humidity

Protocol 2: Coaxial Electrospinning for Core-Shell PQD Composites

This protocol enables the fabrication of core-shell fibers with PQDs localized in the core region, providing enhanced protection against environmental degradation.

Materials:

- Core polymer: PCL (MW 70,000-90,000)

- Shell polymer: PVDF (MW 275,000)

- PQDs (CsPbI₃ or mixed halide for tunable emission)

- Solvent systems: DMF/acetone for shell, chloroform for core

Equipment:

- Coaxial electrospinning setup with specialized spinneret

- Dual-channel syringe pump

- Humidity and temperature control system

Procedure:

Solution Preparation

- Shell solution: Dissolve PVDF (17.5% w/v) in DMF:acetone (3:2) with 0.01% LiCl

- Core solution: Dissolve PCL (10% w/v) in chloroform with dispersed PQDs (1-3% w/w)

Coaxial Electrospinning

- Load core and shell solutions into separate syringes

- Set core flow rate: 0.3 mL/h

- Set shell flow rate: 1.0 mL/h

- Apply voltage: 20-25 kV

- Collection distance: 15-20 cm

- Use rotating collector (200-500 rpm)

Characterization

- Confirm core-shell structure using TEM

- Evaluate PQD distribution using confocal microscopy

- Test encapsulation efficiency through leaching studies

Diagram 1: Coaxial Electrospinning Workflow for Core-Shell PQD Composites

Characterization Methods for Polymer-PQD Composites

Structural and Morphological Characterization

Comprehensive characterization is essential to validate the successful integration of PQDs within polymer nanofibers and to assess composite properties. The following table outlines key characterization techniques and their applications for polymer-PQD composites.

Table 4: Characterization Techniques for Polymer-PQD Composites

| Technique | Information Obtained | Sample Preparation | Typical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Fiber morphology, diameter, surface texture, bead formation | Sputter coating with Au/Pd (5-10 nm) | Acceleration voltage: 5-15 kV, working distance: 5-10 mm |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | PQD distribution, localization, core-shell structure, particle size | Ultramicrotomy (50-100 nm sections) or direct deposition on grid | Acceleration voltage: 80-200 kV, STEM mode for elemental mapping |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Surface roughness, mechanical properties, fiber topography | None required | Tapping mode, scan rate: 0.5-1 Hz, silicon cantilevers |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface composition, chemical states, PQD encapsulation efficiency | None required | Monochromatic Al Kα source, spot size: 200-500 μm, charge neutralization |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Chemical interactions, functional groups, polymer-PQD interfaces | KBr pellet or ATR attachment | Resolution: 4 cm⁻¹, scans: 32-64, range: 4000-400 cm⁻¹ |

Optical and Functional Characterization

The optical properties of PQDs within the composite fibers must be carefully evaluated to ensure retention of functionality after the electrospinning process.

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy:

- Measure emission spectra, quantum yield, and lifetime

- Compare free PQDs versus incorporated PQDs to assess matrix effects

- Evaluate photostability under continuous illumination

- Map distribution using confocal laser scanning microscopy

Stability Assessment:

- Environmental testing: expose to controlled humidity (40-90% RH) and temperature (25-60°C)

- Accelerated aging studies to predict long-term performance

- Leaching tests: immerse in aqueous solutions and measure PQD release over time

- Mechanical stability: evaluate optical properties under strain

Drug Release Profiling (for therapeutic applications):

- Use UV-Vis spectroscopy or HPLC to quantify drug release

- Evaluate release kinetics under physiological conditions

- Correlate release profiles with composite morphology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Electrospun PQD Composites

| Category | Item | Specification | Function | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers | PLGA | 50:50 or 75:25 LA:GA ratio, MW 50,000-100,000 | Biodegradable matrix for drug delivery | Sigma-Aldrich, Lactel, Corbion |

| PCL | MW 70,000-90,000 | Flexible, slow-degrading core polymer | Sigma-Aldrich, Perstorp | |

| PVDF | MW ~275,000 | Piezoelectric shell polymer | Sigma-Aldrich, Arkema | |

| Solvents | DMF | Anhydrous, 99.8% | Polar aprotic solvent for electrospinning | Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific |

| Chloroform | Anhydrous, ≥99% | Non-polar solvent for PQD dispersion | Sigma-Aldrich, Merck | |

| DCM | Anhydrous, ≥99.8% | Volatile solvent for rapid drying | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI | |

| PQD Precursors | Cs₂CO₃ | 99.9% trace metals basis | Cesium source for PQD synthesis | Sigma-Aldrich, Strem Chemicals |

| PbBr₂ | 99.999% trace metals basis | Lead source for PQD synthesis | Sigma-Aldrich, Alfa Aesar | |

| Oleic Acid | Technical grade, 90% | Surface ligand for PQD stabilization | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI | |

| Stabilizers | LiCl | Anhydrous, 99% | Solution conductivity enhancer | Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific |

| FAS | 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane, 97% | Hydrophobicity enhancer | Sigma-Aldrich, Gelest | |

| Characterization | TEM Grids | Copper, 300 mesh | Sample support for electron microscopy | Ted Pella, Electron Microscopy Sciences |