Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA) and related techniques, exploring their foundational principles, diverse applications in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical research, and current methodological...

Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis: Advanced Techniques and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA) and related techniques, exploring their foundational principles, diverse applications in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical research, and current methodological advancements. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers key applications from drug delivery system characterization and nanoparticle biodistribution to stability testing and impurity detection. The content also addresses troubleshooting common challenges, explores optimization strategies leveraging AI and automation, and offers a comparative analysis of spectroscopic methods to guide appropriate technique selection. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge trends, this resource aims to be an essential guide for leveraging electron spectroscopy in advancing drug development and materials science.

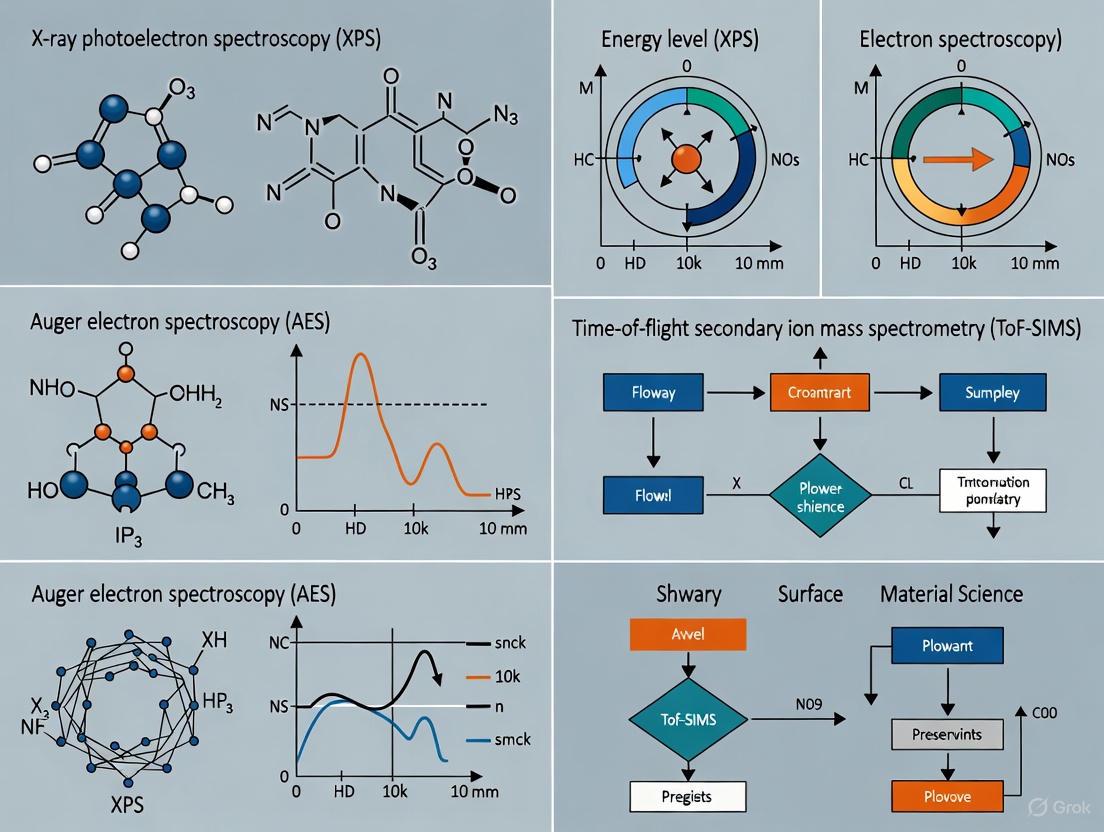

Understanding Electron Spectroscopy: Core Principles and Techniques for Chemical Analysis

Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA/XPS)

Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), more commonly known as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), is a powerful surface analysis technique that provides both elemental and chemical state information from the top 0 to 10 nanometers of a solid material [1] [2]. This technique is based on the photoelectric effect, where a sample is irradiated with X-rays, causing the ejection of photoelectrons from core atomic energy levels. The kinetic energy of these emitted photoelectrons is characteristic of the element from which they originated, enabling precise elemental identification [1]. The surface sensitivity of XPS stems from the short distance that photoelectrons can travel through a material without losing kinetic energy; typically, only electrons originating from the top 1-10 nm contribute to the characteristic photoelectron peaks [1].

The binding energy (BE) of a photoelectron is related to its measured kinetic energy (KE) through the fundamental equation: BE = hν - KE, where hν represents the energy of the incident X-ray photon [1]. Small shifts in binding energy (chemical shifts) occur due to changes in the chemical environment of the atom, providing crucial information about chemical bonding, oxidation states, and molecular structure [1] [2]. This chemical shift phenomenon is what enables XPS to serve as a true "Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis," distinguishing it from mere elemental analysis techniques [3].

XPS has become the most widely used surface-analysis method across numerous scientific fields, including materials science, chemistry, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical development [4]. Its versatility allows for the analysis of a broad range of materials, including surface coatings, thin films, polymers, metals, ceramics, and biological specimens [5] [2]. The technique detects all elements except hydrogen and helium, making it particularly valuable for characterizing organic and inorganic materials where surface composition critically influences performance and functionality [2].

Fundamental Principles

The Photoemission Process

The underlying physical principle of XPS is the photoelectric effect. When an X-ray photon of known energy (typically Al Kα at 1486.6 eV or Mg Kα at 1253.6 eV) interacts with an atom in the sample, it may eject a core-level electron if the photon energy exceeds the electron's binding energy [3]. The kinetic energy of this ejected photoelectron is measured by the spectrometer, allowing calculation of its original binding energy within the atom [2].

Each element produces a characteristic set of photoelectron peaks corresponding to its electronic energy levels (1s, 2s, 2p, etc.), creating a unique "fingerprint" that enables elemental identification [2]. The intensity of these peaks relates to the concentration of the element within the sampling volume, while the precise binding energy position reveals the chemical state of the element [3].

Chemical Shifts and Chemical State Information

The binding energy of a core electron is influenced by the chemical environment of the atom. Changes in oxidation state, molecular structure, and bonding partners cause small shifts in binding energy (typically 0.1-10 eV) known as chemical shifts [1] [2]. For example, the carbon 1s peak appears at approximately 285 eV in hydrocarbons but shifts to 289 eV in carboxylic acids, and to 287 eV in carbonyl compounds. Similarly, metals show significant binding energy increases when oxidized compared to their metallic state [2].

These chemical shifts occur because changes in the valence electron distribution affect the electrostatic screening of core electrons. Electron-withdrawing groups decrease screening and increase binding energy, while electron-donating groups have the opposite effect. By measuring these precise energy positions, XPS can identify specific functional groups and oxidation states, providing molecular-level information beyond simple elemental composition [3].

Analytical Capabilities and Limitations

XPS provides several key analytical capabilities, each with specific strengths and limitations that researchers must consider when designing experiments:

Table: Analytical Capabilities of XPS/ESCA

| Capability | Typical Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Elemental Detection | All elements except H and He [2] | Hydrogen and helium cannot be detected directly |

| Detection Limits | ~0.1 atomic % (element-dependent) [4] | Varies with element, cross-section, and background |

| Depth Resolution | 0.5-10 nm (information depth) [1] | Limited by electron escape depth; varies with kinetic energy |

| Lateral Resolution | 1 μm to >100 μm (instrument dependent) [1] | Highest resolution requires specialized equipment |

| Chemical State Identification | Oxidation states, functional groups [2] | Requires reference data and careful interpretation |

| Quantitative Accuracy | ±5-20% (material dependent) [3] | Most accurate for homogeneous polymers; less for transition metals |

The technique is particularly surface-sensitive due to the short inelastic mean free path of electrons in solids, which limits the sampling depth to typically 1-10 nm, depending on the kinetic energy of the photoelectrons and the material being analyzed [1]. This extreme surface sensitivity means that sample handling, preparation, and environmental exposure critically influence results, as contamination layers of just one nanometer can completely obscure the underlying substrate [4].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Guidelines

Proper sample preparation is essential for obtaining meaningful XPS data. The appropriate method depends on the sample properties and analytical questions:

Solid Samples: Flat, smooth surfaces (typically ≥ 5mm × 5mm) provide the most reliable quantitative data. Samples should be cleaned appropriately to remove surface contamination—common methods include solvent cleaning, plasma cleaning, or gentle abrasion. Samples must be compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (<10⁻⁸ mbar), meaning they should have low vapor pressure to avoid outgassing [4].

Powdered Samples: Can be pressed into indium or gold foil, sprinkled onto double-sided adhesive tape, or compacted into pellets. Care must be taken to avoid excessive charging in non-conductive powders [5].

Specialized Preparations: For bulk analysis of air-sensitive materials, preparation in an inert atmosphere glove box attached to the XPS introduction chamber is necessary. Fracturing, cleaving, or scribing samples under UHV can expose clean surfaces for analysis [3].

Liquid Samples: Require specialized near-ambient pressure (NAP) XPS systems, such as the EnviroESCA, which can analyze liquids and samples under controlled atmospheres up to 50 mbar [5].

Data Collection Workflow

A systematic approach to data collection ensures comprehensive and reproducible results:

Survey Spectrum: Collect a wide energy range scan (typically 0-1200 eV binding energy) to identify all elements present. Use pass energy of 80-160 eV for optimal sensitivity. This guides subsequent high-resolution analysis [1] [2].

High-Resolution Regional Scans: Acquire detailed spectra of each identified element's principal peaks with higher energy resolution (pass energy 20-40 eV). These scans provide precise chemical state information and enable accurate quantification [4].

Charge Compensation: For insulating samples, use low-energy electron flood guns or charge neutralization systems to counteract surface charging. Charge referencing may be necessary using adventitious carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV) or known internal references [4].

Specialized Measurements:

- Angle-Resolved XPS (ARXPS): Vary the emission angle between sample surface and analyzer to obtain non-destructive depth profiling information [4].

- XPS Imaging: Map the spatial distribution of elements and chemical states across the surface with micron-scale resolution [1].

- Depth Profiling: Combine XPS with ion sputtering (typically Ar⁺ clusters) to progressively remove surface layers and analyze composition as a function of depth [3].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard XPS data collection and analysis process:

Instrument Calibration and Performance Verification

Regular verification of instrument performance is essential for reproducible, reliable data:

Energy Scale Calibration: Verify using standard reference materials such as clean gold (Au 4f₇/₂ at 84.0 eV), silver (Ag 3d₅/₂ at 368.3 eV), or copper (Cu 2p₃/₂ at 932.7 eV) [4].

Intensity Response: Check using standard samples with known intensity ratios to ensure quantitative accuracy.

Spatial Resolution: Verify imaging capabilities using appropriate resolution test patterns.

Performance verification should be conducted regularly according to manufacturer specifications and documented for quality assurance purposes [4].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Peak Identification and Chemical State Analysis

The first step in XPS data interpretation is identifying elements from their characteristic binding energies:

Table: Characteristic Binding Energies of Common Elements

| Element | Principal Peak(s) | Binding Energy (eV) | Chemical State Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | C 1s | 284.8 (adventitious) | Chemical shifts of 1-4 eV distinguish hydrocarbons, alcohols, carbonyls, carboxylates |

| Oxygen (O) | O 1s | 530-533 | Metal oxides (~530 eV), organic oxygen (~532-533 eV) |

| Nitrogen (N) | N 1s | 398-402 | Amines (~399 eV), amides (~400 eV), quaternary nitrogen (~402 eV) |

| Silicon (Si) | Si 2p | 99-104 | Elemental Si (99 eV), SiO₂ (103-104 eV) |

| Gold (Au) | Au 4f₇/₂ | 84.0 | Metallic gold (reference standard) |

| Copper (Cu) | Cu 2p₃/₂ | 932.7 | Metallic copper, Cu⁺ (~932.5 eV), Cu²⁺ (~933.5 eV with strong satellites) |

Chemical state identification requires comparison with reference databases and literature values. Distinct spectral features beyond simple peak position include:

- Peak shape changes: Asymmetry in metal peaks indicates metallic character, while symmetric peaks often suggest insulating compounds.

- Spin-orbit splitting: The intensity ratio and separation between doublet components (e.g., 2p₁/₂ and 2p₃/₂) should follow theoretical predictions.

- Satellite features: "Shake-up" satellites appear in certain transition metal compounds and aromatic systems, providing additional chemical state information [3].

Quantification Methods

Quantitative analysis in XPS involves measuring peak intensities and correcting for elemental sensitivity factors. The atomic concentration of an element is calculated as:

[ Cx = \frac{Ix / Sx}{\sum(Ii / S_i)} ]

Where:

- (C_x) = Atomic concentration of element x

- (I_x) = Measured peak intensity for element x

- (S_x) = Sensitivity factor for element x

- The denominator sums over all detected elements

Two primary approaches exist for determining sensitivity factors:

- Theoretical Sensitivity Factors (t-RSF): Based on calculated photoionization cross-sections, inelastic mean free paths, and instrument transmission functions [3].

- Empirical Sensitivity Factors (e-RSF): Derived from measurements on standard compounds with known composition [3].

For homogeneous materials containing only first-row elements (Li to F), quantification accuracy of ±4% is achievable. For transition metals, lanthanides, and actinides with complex spectra featuring strong satellite structure, accuracy may be limited to ±20% [3].

Spectral Processing and Peak Fitting

Proper spectral processing is essential for accurate chemical state identification and quantification:

Background Subtraction: Remove inelastically scattered electrons using appropriate methods (Shirley, Tougaard, or linear backgrounds).

Peak Fitting: Deconvolve overlapping peaks using synthetic components with appropriate:

- Line shapes (Gaussian-Lorentzian mixes)

- Peak positions based on chemical shift expectations

- Full width at half maximum (FWHM) constraints

- Appropriate spin-orbit splitting ratios and separations

Validation: Ensure fitted models are chemically and physically reasonable, with appropriate constraints based on sample knowledge.

The following diagram illustrates the XPS data interpretation workflow:

Advanced Applications and Complementary Techniques

Specialized XPS Applications

Thin Film Analysis: XPS provides exceptional characterization of thin films (1-100 nm) commonly used in pharmaceutical coatings and medical devices. It can measure layer thickness, uniformity, and surface chemistry non-destructively [2]. Angle-resolved XPS can determine stratification in multilayer films with nanometer-scale depth resolution [4].

Contamination Analysis: Surface contaminants such as processing residues, adventitious carbon, or unwanted oxides can be identified and quantified with high sensitivity (~0.1 atomic %) [2]. For example, chromium residue on polyimide substrates was identified as the cause of haze formation in electronic components [2].

Passivation Layer Verification: XPS can verify the integrity of passivation layers on stainless steel and other alloys by measuring the chromium-to-iron ratio in oxide layers. A Cr/Fe ratio >2 indicates proper passivation for corrosion resistance [2].

Nanoparticle Characterization: Surface composition of nanoparticles critical for drug delivery systems can be analyzed, though special considerations for quantification apply due to curvature effects and non-uniform emission [3].

Complementary Techniques

XPS provides comprehensive surface chemical information but is often enhanced when combined with complementary techniques:

Table: Techniques Complementary to XPS

| Technique | Information Provided | Complementary Value to XPS |

|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) | Valence electronic structure, work function measurements [1] | Extends chemical bonding information to valence levels |

| Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES) | Bulk-sensitive chemical information (up to 20 nm depth) [1] | Probes beyond surface region accessed by conventional XPS |

| Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) | Elemental composition with higher spatial resolution (~10 nm) [4] | Provides superior lateral mapping for heterogeneous samples |

| Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) | Molecular speciation, trace detection, imaging [4] | Identifies molecular species that XPS cannot resolve |

| Near-Ambient Pressure XPS (NAP-XPS) | Analysis under realistic environmental conditions [5] | Enables studies of liquids, biological samples, and operational catalysts |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful XPS analysis requires appropriate standards, reagents, and materials throughout the analytical process:

Table: Essential Materials for XPS Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Gold, silver, copper foils | Energy scale calibration and instrument performance verification [4] |

| Charge Reference Materials | Adventitious carbon, vapor-deposited gold nanoparticles | Charge referencing for insulating samples [4] |

| Sample Substrates | Indium foil, double-sided conductive tape, silicon wafers | Mounting powders and irregular samples [5] |

| Cleaning Reagents | HPLC-grade solvents, argon gas cluster sources | Removal of surface contamination without damaging underlying chemistry [4] |

| Sputter Sources | Argon ion guns, C₆₀ cluster sources | Depth profiling through sequential surface removal [3] |

| Reference Databases | NIST XPS Database, commercial libraries | Chemical shift identification and validation [4] |

XPS/ESCA provides unparalleled capability for surface chemical analysis with both elemental specificity and chemical state information. Its extreme surface sensitivity makes it indispensable for characterizing thin films, coatings, and interfaces where surface composition dictates material performance. When properly applied with careful attention to sample preparation, instrument calibration, and data interpretation protocols, XPS delivers valuable insights for research and quality control across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, materials science, and biotechnology.

The technique continues to evolve with advancements in instrumentation, such as near-ambient pressure capabilities for analyzing liquids and biological specimens, and improved data analysis methods for extracting more detailed chemical information. As surface science plays an increasingly critical role in technology development, XPS remains a cornerstone analytical technique for understanding and optimizing material interfaces at the molecular level.

Electron spectroscopy techniques are indispensable tools in modern materials science, chemistry, and drug development research, providing critical information about elemental composition, chemical states, and electronic structure. This article focuses on three principal methods: X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES), and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), also known as Electron Spin Resonance (ESR). These techniques are united by their ability to probe interactions between electrons and matter, yet each offers unique capabilities. XPS is renowned for its surface sensitivity and quantitative chemical state analysis, while AES provides high-resolution elemental mapping and depth profiling. EPR/ESR specializes in detecting species with unpaired electrons, such as free radicals and transition metal ions. Within the broader context of electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis (ESCA) research, understanding the principles, applications, and protocols for these techniques is fundamental for advancing research in material characterization, catalytic processes, and pharmaceutical development.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

Working Principle

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), also known as Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), is a surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopic technique that probes the outermost 5–10 nm (approximately 50–60 atomic layers) of a material [6] [7]. Its operation is based on the photoelectric effect, where a sample irradiated with X-rays emits photoelectrons [8]. The kinetic energy ((E{\text{kinetic}})) of these emitted electrons is measured by the instrument, and the core-level electron binding energy ((E{\text{binding}})) is calculated using the fundamental equation [6] [7]: [ E{\text{binding}} = E{\text{photon}} - (E{\text{kinetic}} + \phi) ] where (E{\text{photon}}) is the energy of the incident X-ray photon, and (\phi) is the spectrometer work function [6]. Since the binding energy is unique to each element and is influenced by its chemical environment, XPS can identify both the elemental composition and the chemical state of the elements present on the surface [6] [7].

Fig. 1: The workflow of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS).

Key Applications and Protocols

Application 1: Surface Compositional Analysis of a Polymer Material

- Objective: To determine the surface elemental composition and identify chemical functional groups in an as-received polymer sample, such as Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) [7].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the PET sample on a standard holder using double-sided conductive tape. Do not clean the surface to analyze it in its "as-received" state, which includes adventitious carbon contaminants [7] [8].

- Instrument Setup: Insert the sample into the XPS chamber under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (pressure < 10⁻⁹ Torr). Select an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) and set the analyzer pass energy to a value suitable for survey scans (e.g., 100 eV) [7] [8].

- Data Acquisition:

- Survey Scan: Acquire a broad spectrum over a binding energy range of 0-1100 eV to identify all elements present [7].

- High-Resolution Scans: Perform high-resolution scans over the spectral regions of key elements (e.g., C 1s, O 1s). Use a lower analyzer pass energy (e.g., 20-50 eV) for better energy resolution [7].

- Data Analysis:

- Identify elements from the peak positions in the survey scan.

- For quantitative analysis, calculate atomic concentrations using the formula: ( Cx = (Ix / Sx) / \sum (Ii / S_i) ), where (I) is peak intensity and (S) is the elemental sensitivity factor [6] [7].

- Deconvolute the high-resolution C 1s peak to quantify contributions from different carbon functional groups (e.g., C-C/C-H at 285.0 eV, C-O at 286.5 eV, C=O at 288.0 eV) [7].

Application 2: Depth Profiling of a Thin Film Coating

- Objective: To investigate the composition and chemical state as a function of depth through a thin film coating, such as boron on carbon steel [7].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the coated sample securely to ensure a flat, uniform surface for profiling.

- Instrument Setup: Establish UHV and select a monochromatic X-ray source. Position the ion gun for sputtering.

- Data Acquisition:

- Set up a multiplex routine to monitor the photoelectron peaks of interest (e.g., B, O, Fe).

- Begin by collecting XPS data from the surface.

- Use an Ar⁺ ion gun to sputter the surface for a fixed time (e.g., 30 seconds) to remove a thin layer (e.g., ~2 nm/cycle).

- Collect XPS data from the newly exposed surface.

- Repeat the sputter-and-measure cycle until the substrate signal (Fe) dominates [7].

- Data Analysis: Plot the atomic concentration of each element against sputter time or cycle number to generate a depth profile, revealing layer thickness and interfacial reactions [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for XPS

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for XPS analysis.

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Tape (Double-sided) | Securely mount samples to the stub for electrical contact and stability. | Mounting insulating polymer samples [8]. |

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | Source for the ion gun used for sample cleaning and depth profiling via sputtering [7]. | Removing surface contaminants; depth profiling thin films [7]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration of binding energy scale and verification of instrument performance. | Gold (Au 4f₇/₂ at 84.0 eV), Copper (Cu 2p₃/₂ at 932.7 eV), Adventitious Carbon (C 1s at 284.8 eV) [7]. |

| Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Acetone) | Clean samples to remove volatile and non-volatile organic contaminants without damaging the surface [8]. | Washing metal alloys prior to corrosion studies. |

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES)

Working Principle

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful analytical technique for surface elemental analysis and high-resolution spatial mapping. The process involves three fundamental steps [6]:

- Core Ionization: A high-energy electron beam (typically 3-10 keV) ejects a core-level electron from an atom.

- Electron Relaxation: An electron from a higher energy level falls to fill the core hole.

- Auger Emission: The energy released from the relaxation process is transferred to another electron, which is then ejected—this is the Auger electron.

The kinetic energy of the emitted Auger electron is characteristic of the element from which it was emitted and is largely independent of the incident beam energy, providing a unique fingerprint for elemental identification. AES is highly surface-sensitive, probing the top 5-10 nm of a material, and is particularly valued for its excellent spatial resolution (down to ~10 nm), making it ideal for microanalysis and failure analysis [6].

Fig. 2: The Auger process and spectroscopy workflow.

Key Applications and Protocols

Application: Failure Analysis of a Semiconductor Device

- Objective: To identify and map elemental contaminants causing a short circuit in a microelectronic device.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The device is carefully cross-sectioned to expose the region of interest. It is then mounted in a conductive holder to prevent charging.

- Instrument Setup: The sample is loaded into a UHV chamber. A primary electron beam is focused onto the region of interest. An electron energy analyzer (typically a Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer, CMA) is tuned for optimal Auger electron collection [8].

- Data Acquisition:

- Point Analysis: Obtain an AES spectrum from a specific, suspect location (e.g., a via) to identify unexpected elements like chlorine or sodium.

- Elemental Mapping: Scan the electron beam across a defined area while tracking the intensity of a specific Auger peak. This generates a map showing the spatial distribution of each element.

- Depth Profiling: Combine with an Ar⁺ ion sputtering gun to progressively remove material and create a three-dimensional compositional profile [6].

- Data Analysis: Overlay elemental maps to correlate the location of contaminants with device structures. Depth profiles quantify the extent of contamination.

Research Reagent Solutions for AES

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for AES analysis.

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Source for ion sputtering for depth profiling and surface cleaning. | Creating depth profiles through thin film stacks on a wafer. |

| Conductive Mounting Stubs | Provide a stable, electrically grounded platform for the sample. | Analyzing semiconductor fragments to prevent charging. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Verification of analyzer calibration and sputter rates. | Pure elemental standards like Si, Cu, or Au. |

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) / Electron Spin Resonance (ESR)

Working Principle

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) or Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) is a spectroscopic technique used to study species with unpaired electrons, such as free radicals, transition metal ions, and defects in solids [9] [10]. The fundamental principle relies on the Zeeman effect: in an external magnetic field ((B0)), the energy levels of an electron's magnetic moment, which has two possible spin states ((ms = +1/2) and (ms = -1/2)), split [9]. The energy difference ((\Delta E)) between these states is given by: [ \Delta E = ge \muB B0 ] where (ge) is the electron g-factor (approximately 2.0023 for a free electron), and (\muB) is the Bohr magneton [9]. Resonance occurs when the sample is irradiated with microwave radiation whose energy ((h\nu)) matches this splitting: [ h\nu = ge \muB B_0 ] At resonance, unpaired electrons absorb energy and transition between the spin states. The resulting absorption spectrum provides information on the identity, concentration, and local environment of the paramagnetic species [9] [10]. Parameters like the g-factor, hyperfine coupling (interaction with magnetic nuclei), and zero-field splitting are key to interpreting EPR spectra [9].

Fig. 3: The basic principle of Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy.

Key Applications and Protocols

Application 1: Detection and Identification of Free Radicals in a Chemical Reaction

- Objective: To confirm the formation of a transient hydroxyl radical (•OH) intermediate during a Fenton-like reaction.

- Protocol:

- Spin Trapping: Due to the short lifetime of many radical species, a spin trapping protocol is used. A spin trap molecule, such as 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO), is added to the reaction solution. DMPO rapidly reacts with •OH to form a stable, EPR-detectable nitroxide radical adduct (DMPO-OH) [11].

- Sample Preparation: After a defined reaction time (e.g., 1 minute), withdraw an aliquot of the solution and transfer it to a quartz EPR flat cell. The use of aqueous solutions requires careful cell selection [10].

- Instrument Setup: Place the sample in the resonant cavity of the EPR spectrometer. Set the microwave frequency to the X-band (~9.85 GHz), the center field to ~3500 G, and a sweep width of 100 G. Apply a small high-frequency magnetic field modulation (e.g., 100 kHz) to obtain the first derivative of the absorption signal [9] [10].

- Data Acquisition: Record the spectrum at room temperature or at low temperature (to enhance signal stability) with low microwave power to avoid saturation.

- Data Analysis: Identify the DMPO-OH adduct by its characteristic EPR signature: a 1:2:2:1 quartet pattern of lines [11]. The number of lines, their intensity ratio, and splitting (hyperfine coupling constants) are used for radical identification.

Application 2: Investigating Metal Centers in a Metalloprotein

- Objective: To probe the coordination environment and oxidation state of a Mn²⁺ center in a protein.

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Purify the protein in a suitable buffer. Transfer the solution to an EPR tube. For enhanced resolution, flash-freeze the sample in liquid nitrogen to create a glassy state.

- Instrument Setup: Insert the frozen sample into a pre-cooled cryostat (e.g., 77 K) in the spectrometer.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a spectrum over a wide magnetic field range to capture the full Mn²⁺ signal (typically a six-line pattern centered near g=2.0). Use non-saturating microwave power and modulation amplitude.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the g-factor value, the number of lines, and the hyperfine splitting constants. Compare these parameters with model compounds to deduce the metal's oxidation state and ligand field geometry [9] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for EPR/ESR

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for EPR/ESR analysis.

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Spin Traps (e.g., DMPO) | React with short-lived radicals to form stable, EPR-detectable adducts. | Trapping hydroxyl (•OH) or superoxide (•O₂⁻) radicals in aqueous solutions [11]. |

| Quartz EPR Tubes/Flat Cells | Hold samples in the resonant cavity; quartz is microwave-transparent and does not generate interfering signals. | Analyzing aqueous samples and frozen solutions. |

| Stable Radical Standards (e.g., DPPH) | Used for g-factor calibration and instrument verification. | Calibrating the magnetic field position (DPPH has g ≈ 2.0036) [11]. |

| Cryogenic Coolants (Liquid N₂, He) | Cool samples to increase the population difference between spin states, dramatically enhancing signal intensity [9]. | Studying biological samples or any system with a weak signal. |

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

The selection of an appropriate technique depends on the specific research question, as each method offers distinct capabilities and limitations. The following table provides a direct comparison to guide this decision-making process.

Table 4: Comparative analysis of XPS, AES, and EPR/ESR techniques.

| Parameter | XPS | AES | EPR/ESR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Elemental identity, chemical state, empirical formula [6] [7] | Elemental identity, lateral distribution [6] | Presence of unpaired electrons, oxidation state, coordination geometry [9] [11] |

| Probed Species | All elements except H and He [6] | All elements except H and He [6] | Species with unpaired electrons: free radicals, paramagnetic metal ions, defects [9] |

| Detection Limit | ~0.1-1 at% (1000-10000 ppm); can reach ppm with long times [6] | Similar to XPS | Very high sensitivity for paramagnetic centers; can detect sub-picomole quantities [10] |

| Spatial Resolution | 10-200 µm; down to 200 nm with special sources [6] | Excellent; can be < 10 nm [6] | Typically macroscopic; limited spatial resolution. |

| Sample Environment | UHV (< 10⁻⁹ Torr) [6] [7] | UHV [6] | Vacuum not always required; samples can be in gases, liquids, or solids. |

| Quantification | Excellent semi-quantitative accuracy (90-95% for major elements) [6] | Good semi-quantitative analysis [6] | Can be quantitative for spin concentration with careful calibration. |

| Key Strengths | Superior chemical state information; quantitative; good for insulators [7] | High spatial resolution; excellent for mapping and profiling [6] | Unique sensitivity to unpaired electrons; provides structural and dynamic information [9] |

| Main Limitations | Poor lateral resolution; requires UHV; can damage sensitive materials [6] [8] | Electron beam can damage polymers/organics; requires UHV and conductive samples [6] | Only applicable to paramagnetic systems; complex spectral interpretation [9] |

Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), also known as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), is a surface-sensitive analytical technique crucial for determining the elemental composition, empirical formula, and chemical state of materials. The market is experiencing significant growth, driven by increasing demand across industrial, commercial, and technological segments [12].

Table 1: Projected Market Growth for Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA/XPS)

| Market Segment | Base Year/Value | Projected Year/Value | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States ESCA Market [12] | USD 6.5 Billion (2025) | USD 15.93 Billion (2033) | 16.11% (2026-2033) | Advancements in analytical technologies, demand from material science and semiconductors, stringent quality control standards. |

| Global XPS/ESCA Market [13] | USD 1.83 Billion (2025) | USD 6.34 Billion (2032) | 19.44% (2025-2032) | Rising demand for high-performance materials, integration with AI and machine learning, expanding applications in healthcare and pharmaceuticals. |

| Global ESCA Market [14] | Information Not Provided | ~USD 1.5 Billion (2033) | 6.2% (2025-2033) | Technological advancements in spectroscopy equipment, increased R&D funding in academic and industrial labs. |

| Global ESCA Market (Alternative Estimate) [15] | Information Not Provided | Information Not Provided | 5.7% (2025-2032) | Automation, miniaturization of instruments, and collaborative cross-industry platforms. |

The growth is fueled by several key factors. Technologically, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is optimizing data interpretation, enabling quicker and more precise analysis [13] [15]. There is also a strong trend towards the miniaturization of instruments, making ESCA more accessible and portable for a broader range of users [15]. From an application perspective, increasing complexity in semiconductor devices and the rising demand for advanced material characterization in pharmaceuticals and biomedicine are major drivers [12] [14] [16].

Application in Active Electrochemical Structural Color Research

Experimental Protocol for Electrochemical HCG Analysis

The following protocol is adapted from research on active electrochemical high-contrast gratings (HCGs) as switchable pixels, which utilized XPS/ESCA for surface characterization [17].

1. Substrate Preparation and HCG Fabrication

- Working Electrode (WE) Preparation: Begin with a substrate containing a Pt electrode. Clean the Pt surface using standard plasma cleaning protocols to remove organic contaminants.

- Dielectric Grating Deposition: Deposit a thin film (e.g., 100 nm) of titanium oxide (TiOx) onto the Pt electrode using electron-beam evaporation.

- Patterning High-Contrast Gratings (HCG): Use electron-beam lithography to define 50 × 50 μm² HCG patterns on the TiOx film. The period of the gratings should be designed between 290 nm and 510 nm, with a slit width of approximately 165 nm. Develop the resist and etch the TiOx to form the final grating structure [17].

2. Electrochemical Cell Assembly

- Electrolyte Preparation: Dissolve 1 M copper(II) nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO₃)₂ · 3H₂O) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Ensure complete dissolution and degas the solution if necessary.

- Cell Configuration: Integrate the HCG/Pt substrate as the working electrode. Use an Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) slide as the counter electrode (CE). Assemble a miniature electrochemical cell, ensuring the electrolyte is in contact with both electrodes. A reference electrode may be omitted for miniaturized cells, as potentiostat cyclic voltammetry (CV) characteristics can be sufficiently consistent [17].

3. Electrochemical Operation and Color Switching

- Copper Electrodeposition (Color Tuning): Apply a cathodic bias to the Pt working electrode using a potentiostat. The specific voltage will depend on the cell configuration but should be sufficient to reduce Cu²⁺ ions to metallic Cu (typically ΔV < 3 V). This causes Cu to deposit inside the grating slits, actively tuning the structural color by modifying the modal interference of light [17].

- Copper Dissolution (On/Off Switching): For on/off switching, apply an anodic bias or allow the system to reach an open-circuit potential. This dissolves the deposited Cu, creating a disordered porous structure that scrambles light scattering and increases absorption, effectively switching the pixel "off" with high contrast [17].

4. Optical Characterization and Analysis

- Cross-Polarized Imaging: Configure an optical microscope with cross-polarizers. Rotate the HCG sample at -45° relative to the incident polarized white light. Collect the reflected light through an orthogonal (crossed) polarizer.

- Spectral Data Collection: Use a spectrometer coupled to the microscope to acquire reflection spectra from the active pixel area. Monitor the spectral shifts and intensity changes corresponding to Cu deposition and dissolution.

- Surface Analysis (Post-Experiment): For detailed surface chemical analysis, carefully extract the sample from the electrochemical cell, clean it with a volatile solvent to remove electrolyte residues, and analyze using ESCA/XPS to confirm the chemical states of Cu, Pt, and TiOx before and after electrochemical cycling [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Electrochemical HCG Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Experimental Note |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum (Pt) Substrate | Serves as the working electrode and optically stable back-reflector. Its chemical stability ensures long-term experiment viability [17]. | Pre-cleaning via plasma treatment is critical for uniform electrodeposition and strong adhesion. |

| Titanium Oxide (TiOx) | Forms the high-contrast dielectric grating; its high refractive index is essential for strong optical resonances [17]. | Deposited via e-beam evaporation. The grating height and period are key design parameters for target wavelengths. |

| Copper(II) Nitrate Trihydrate (Cu(NO₃)₂ · 3H₂O) | Source of Cu²⁺ ions for reversible electrodeposition and dissolution within the grating slits [17]. | Used at 1 M concentration in DMSO. The nitrate anion facilitates efficient redox cycling. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Polar aprotic solvent for the electrolyte, providing a stable environment for copper redox reactions [17]. | Offers a wide electrochemical window and good solubility for copper salts. |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) Glass | Acts as a transparent counter electrode, allowing optical access while completing the electrochemical circuit [17]. | Ensure surface conductivity and cleanliness before cell assembly. |

| ESCA/XPS System | Validates the surface chemical composition, oxidation states of Cu (Cu⁰ vs. Cu²⁺), and the condition of the TiOx and Pt surfaces post-experiment [17]. | Critical for confirming the mechanism of color tuning and switching at the molecular level. |

Industrial Adoption Trends and Future Outlook

The adoption of ESCA is expanding across numerous industries, driven by its unparalleled surface sensitivity.

Table 3: Industrial Adoption Trends for ESCA/XPS

| Industry | Primary Applications | Market Influence & Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductors & Electronics [14] [18] | Quality control, material characterization, failure analysis of thin films and interfaces. | A major consumer and driver of market revenue, estimated at ~$100 million annually, due to the increasing complexity of devices [18]. |

| Pharmaceuticals & Biomedicine [13] [14] [16] | Drug development, analysis of drug delivery systems, biomaterial surface characterization, studying protein interactions. | One of the fastest-growing segments, driven by the need for detailed analysis of drug purity, crystallinity, and biocompatibility [13] [14]. |

| Materials Science [12] [14] | Research & development of advanced polymers, alloys, ceramics, and nanomaterials. | A substantial market segment, utilizing ESCA for understanding material properties and behavior at the surface level [14]. |

| Food & Beverage [13] [16] | Quality control, contamination detection, and ensuring product consistency and safety. | Growth is fueled by stringent food safety regulations and the need for non-destructive inspection systems [13]. |

Despite the positive outlook, the market faces challenges. The high initial investment for ESCA instruments and the requirement for specialized expertise to operate them and interpret data can limit accessibility, particularly for smaller organizations [12] [14] [18]. Furthermore, manufacturers must navigate a landscape of stringent regulatory standards (e.g., USP <857>, European Pharmacopoeia), which, while ensuring quality, can also complicate market expansion [13] [16].

Future growth will be catalyzed by cross-industry collaborations and the development of hybrid techniques that combine ESCA with other analytical methods [12] [15]. The ongoing trend towards automation and miniaturization is also expected to make these powerful analytical tools more affordable and accessible, further accelerating their adoption across the global research and industrial landscape [15].

Electron Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis (ESCA), more commonly known as X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), is a surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides quantitative information about the elemental composition, empirical formula, chemical state, and electronic state of elements within a material [19]. The technique is underpinned by the photoelectric effect, a physical phenomenon first discovered by Heinrich Rudolf Hertz in 1887 and later explained by Albert Einstein, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1921 [20]. The development of XPS into a powerful analytical tool was pioneered by Kai Siegbahn, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1981 for his work [20].

The fundamental physical principle of XPS involves irradiating a solid sample with a beam of X-rays, causing the emission of photoelectrons from the surface. The kinetic energy of these emitted electrons is measured, and this energy is directly related to the electrons' binding energy within the parent atom, which is characteristic of the element and its chemical state [21]. The core relationship governing this process is expressed by the equation: Binding Energy = hν - Kinetic Energy - φ where hν is the energy of the incident X-ray photon, and φ is the work function of the spectrometer [20] [19]. Because only electrons generated very near the surface (top 1-10 nm) can escape without significant energy loss, XPS is highly surface-sensitive [2] [21].

Simultaneously, the ionization process can lead to a secondary phenomenon known as Auger electron emission. When a core electron is ejected, the resulting hole can be filled by an electron from a higher energy level. The energy released in this transition can either be emitted as a fluorescent X-ray (Figure 1 (b)) or can cause the ejection of another electron, known as an Auger electron (Figure 1 (c)) [20]. Both photoelectrons and Auger electrons carry valuable information about the chemical elements in material surfaces.

Ionization and Electron Emission Processes

Core Ionization Mechanisms

In the context of electron spectroscopy, two primary ionization mechanisms are of critical importance:

Photoionization (XPS/ESCA): This process occurs when an X-ray photon is absorbed by an atom, transferring its energy to a core-level electron. If this energy exceeds the electron's binding energy, the electron is ejected as a photoelectron [20] [19]. The kinetic energy of this photoelectron is measured, allowing for the calculation of its original binding energy. This mechanism forms the basis for XPS.

Electron Impact Ionization (EI): Now more commonly referred to as Electron Ionization, this is an alternative ionization method where energetic electrons interact with gas-phase atoms or molecules to produce ions [22]. The process can be summarized by the reaction: M + e⁻ → M⁺• + 2e⁻ where M is the analyte molecule and M⁺• is the resulting molecular ion [22]. EI is considered a "hard" ionization method because it uses highly energetic electrons (typically 70 eV), leading to extensive fragmentation of molecules, which can be useful for structural determination.

Quantitative Aspects of Electron Emission

The efficiency and yield of electron emission are critical parameters in spectroscopy. The secondary electron yield is defined as the ratio of emitted electrons to incident electrons or ions [23]. The electron emission process can be quantitatively described by several key equations and concepts, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Electron Emission and Ionization

| Parameter | Formula/Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Photoelectron Binding Energy [20] | ( E{\text{binding}} = h\nu - E{\text{kinetic}} - \phi ) | Determines elemental identity and chemical state. |

| Auger Electron Kinetic Energy [20] | ( E{\text{kinetic}} \approx EB - E_C ) (Approx., for shells B and C) | Used for elemental identification independent of the excitation source. |

| Ionization Cross Section (EI) [22] | ( I^+ = \beta Qi L[N]Ie ) | Measures the rate of ion formation in Electron Ionization; depends on sample concentration and instrument parameters. |

| Mean Transverse Energy (MTE) [24] | ( \text{MTE} = \frac{\langle px^2 \rangle}{2m} = \frac{\sigma{p_x}^2}{2m} ) | Describes the transverse momentum spread of an electron beam, critical for source brightness. |

| Transverse Coherence Length [24] | ( L{\perp} = \frac{\hbar}{\sigma{p_x}} ) | Must be larger than the lattice constant for clear diffraction patterns in techniques like UED. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental ionization and relaxation processes that occur in XPS, highlighting the competing pathways of photoelectron and Auger electron emission.

Experimental Protocols for XPS Analysis

Sample Preparation and Handling

Proper sample preparation is paramount for obtaining reliable XPS data. The following protocol outlines the essential steps:

- Sample Compatibility Check: Ensure the sample is compatible with an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environment (~10⁻⁹ mbar). The sample must be solid and stable under vacuum. Outgassing materials (e.g., certain polymers, biological samples) may require special handling or cryo-cooling [19].

- Sample Cleaning: Remove any surface contamination that is not intrinsic to the analysis. This can be done using solvents, plasma cleaning, or in-situ methods such as argon ion sputtering [25] [21]. The cleaning method must be chosen to avoid altering the surface chemistry of interest.

- Mounting: Mount the sample securely on a suitable holder using conductive tape (for insulating samples to aid charge compensation) or by clamping (for conducting samples). The goal is to ensure good electrical and thermal contact with the sample stage [21].

- Loading into UHV: Transfer the mounted sample into the fast-entry load-lock chamber of the XPS instrument. Pump down the load-lock to a high vacuum before transferring the sample into the main analysis chamber.

Data Acquisition Workflow

A standard XPS analysis follows a systematic workflow to comprehensively characterize a sample's surface.

Survey Scan (Wide Scan):

- Purpose: To identify all elements present on the surface (except hydrogen and helium) [2] [19].

- Protocol: Set the analyzer to a wide energy range (typically 0-1200 eV binding energy) and a high pass energy (e.g., 100-160 eV) to maximize sensitivity. Acquire the scan over several minutes to ensure good signal-to-noise for all detectable elements.

High-Resolution Regional Scans:

- Purpose: To determine the chemical state and bonding environment of the elements identified in the survey scan [2] [19].

- Protocol: For each element of interest, set the analyzer to a narrow energy window (covering the specific core-level peaks, e.g., C 1s, O 1s) and a lower pass energy (e.g., 20-50 eV) to achieve high energy resolution. Acquire the scan with a higher number of sweeps to obtain detailed peak shape information.

Charge Compensation (for Insulating Samples):

- Purpose: To neutralize positive charge buildup on non-conductive samples, which can shift peak positions and distort spectra [21].

- Protocol: Activate the instrument's low-energy electron flood gun and/or argon ion source. Adjust the flux of low-energy electrons/ions until the peak positions of a known adventitious carbon (C-C/C-H) peak are stable and align with the standard binding energy of 284.8 eV [21].

Depth Profiling (Optional):

- Purpose: To analyze compositional changes as a function of depth [21] [19].

- Protocol:

- Destructive Profiling: Use an ion gun (e.g., Ar⁺ clusters) to sputter away the surface layer by layer. After each sputtering cycle, acquire survey and/or high-resolution scans from the newly exposed surface. Repeat until the desired depth is reached.

- Non-Destructive Profiling (ARXPS): Tilt the sample relative to the analyzer to change the take-off angle of the photoelectrons. A higher emission angle increases surface sensitivity. Acquire spectra at multiple angles to probe the composition of ultra-thin films (1-5 nm) without sputtering [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for XPS Analysis

| Item/Material | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Conductive Tapes (e.g., Cu, C) | Used to mount powder or insulating samples; provides a path for charge dissipation. Choice of tape material is critical to avoid interfering spectral lines. |

| Standard Reference Samples (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu) | Used for energy scale calibration and instrument performance checks. Clean, sputtered foils are typically used. |

| Argon Gas (Ultra-High Purity) | Used for ion sputtering for sample cleaning and depth profiling. Cluster ion sources enable profiling of organic materials [21]. |

| Monochromatic X-ray Source (Al Kα, Mg Kα) | The photon source for exciting photoelectrons. Monochromatization improves energy resolution and reduces background radiation [21]. |

| Low-Energy Electron Flood Gun | Essential for charge compensation on insulating samples (e.g., polymers, ceramics, glasses) to obtain meaningful data [21]. |

| UHV-Compatible Sample Holders | Platforms designed to hold various sample geometries while maintaining thermal and electrical contact in the vacuum chamber. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Fundamentals of Spectral Interpretation

Interpreting XPS spectra involves analyzing the position, shape, and intensity of photoelectron peaks.

- Peak Position (Binding Energy): The binding energy of a photoelectron peak is characteristic of an element and its orbital (e.g., Si 2p, O 1s). A chemical shift—a change in the binding energy—occurs due to the chemical environment of the atom. For example, the carbon 1s peak in a C-C bond appears at ~284.8 eV, while in a C-F bond, it shifts to a significantly higher binding energy (~290 eV) [2] [19].

- Peak Intensity: The area under a photoelectron peak is proportional to the concentration of that element within the sampled volume. This allows for quantitative analysis of surface composition [2].

- Peak Shape and Width: The full width at half maximum (FWHM) and the asymmetry of a peak can provide information about the chemical state homogeneity, conducting vs. insulating nature of the sample, and the presence of multiple, unresolved chemical states.

Protocol for Peak Fitting and Deconvolution

Peak fitting is used to separate overlapping spectral features from different chemical states of the same element.

- Background Subtraction: Remove the inelastic background signal from the spectrum. The Shirley or Tougaard background methods are commonly used.

- Identify Component Peaks: Based on the element and its possible chemical states, hypothesize the number of component peaks present. For example, the Si 2p spectrum of silicon dioxide (SiO₂) may require a doublet (Si 2p₃/₂ and Si 2p₁/₂) separated by ~0.6 eV with an area ratio of 2:1.

- Choose Line Shape: Use a combination of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions (Voigt profile) to model the peaks. The ratio is often determined by the instrument and sample properties.

- Constrain the Fit: Apply sensible constraints to the fitting parameters, such as fixed spin-orbit splitting, fixed area ratios for doublets, and similar FWHM for peaks from similar chemical environments.

- Iterate and Validate: Perform the fit and assess the quality using the residual (difference between data and fit) and the chi-squared (χ²) value. The residual should be a flat line with minimal structure, indicating a good fit.

Quantitative Analysis and Data Reporting

The atomic concentration of an element is calculated using the formula: Atomic % (A) = (Iₐ / Sₐ) / Σ (Iₙ / Sₙ) × 100% where Iₐ is the integrated peak area of the element, Sₐ is the element's relative sensitivity factor (provided by the instrument manufacturer), and the sum is over all detected elements [19]. A final report should include the survey spectrum, high-resolution spectra with fits for key elements, a table of atomic concentrations, and a discussion of the chemical state assignments.

Applications in Research and Industry

XPS is a versatile technique with broad applications across multiple fields, particularly in drug development and materials science.

- Surface Contamination Analysis: XPS is ideal for identifying the source of stains, discolorations, or unexplained residues on product surfaces, such as hazes on polyimide films in electronics, which can be traced to elements like chromium [2] [19].

- Thin Film and Coating Characterization: The technique is used to measure the thickness and chemical composition of thin films (e.g., oxides, lubricants, functional coatings) and to analyze interfaces between different material layers via depth profiling [21] [19].

- Polymer Surface Modification: XPS can quantify changes in surface functionality, such as the introduction of oxygen or nitrogen-containing groups after plasma treatment, which is critical for improving the biocompatibility or adhesion properties of medical devices [19].

- Corrosion and Passivation Studies: XPS can determine the composition and thickness of passive oxide layers on metals. For instance, it can measure the chromium-to-iron ratio in stainless steel passivation layers to verify their corrosion resistance [2].

ESCA in Action: Methodologies and Pharmaceutical Applications from Drug Delivery to Quality Control

The efficacy and reliability of modern drug delivery systems (DDS) are fundamentally governed by their physicochemical properties. Microviscosity, polarity, and acidity (pH/pKa) are critical parameters that dictate drug release kinetics, stability, and ultimate biological performance [26] [27]. Within the broader context of electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis (ESCA) research, these measurements provide a complementary suite of characterization tools that probe the bulk and microenvironment of DDS, offering insights that are often beyond the surface-sensitive scope of ESCA [25]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for accurately determining these essential parameters, enabling researchers to optimize DDS for targeted therapeutic outcomes.

Measurement of Microviscosity

Theoretical Background

Microviscosity refers to the resistance to diffusion at a molecular level within a formulation's microstructure. Unlike bulk viscosity, it affects the mobility of drug molecules and colloids directly, thereby controlling the drug release rate [27]. In gel-based DDS, for instance, the drug release is governed by both the thermodynamic activity of the drug and the microviscosity of the gel matrix.

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for Microviscosity

Principle: The microviscosity of a gel or colloidal system can be probed by monitoring the Brownian motion of dispersed tracer particles of known size. The diffusion coefficient is inversely related to the microviscosity of the immediate microenvironment [27].

Materials:

- Carbopol gel or other polymer matrix of interest

- Model drug (e.g., a salicylate)

- Monodisperse polystyrene latex beads (e.g., 100 nm diameter)

- Dynamic light scattering instrument

- Thermostatic water bath

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Incorporate a small quantity (e.g., 0.1% w/w) of monodisperse polystyrene latex beads into the gel matrix during formulation. Ensure homogeneous dispersion using gentle stirring to avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Temperature Equilibration: Place the sample in a DLS cuvette and allow it to equilibrate in the instrument's thermostated chamber at the desired temperature (e.g., 25°C, 32°C, 37°C) for at least 15 minutes.

- Data Acquisition: Measure the intensity autocorrelation function of the scattered light at a fixed angle (e.g., 90°). Perform a minimum of ten measurements per sample.

- Data Analysis: The software calculates the hydrodynamic size of the beads via the Stokes-Einstein equation: D = kT / 6πηr, where D is the diffusion coefficient, k is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, η is microviscosity, and r is the particle radius. Since r is known, the apparent microviscosity (η) of the gel can be derived.

Applications: This protocol is exemplified in a study investigating Carbopol gels, where the effect of gel concentration and temperature on microviscosity was directly related to the release profiles of a series of salicylates [27].

Table 1: Effect of Gel Concentration and Temperature on Microviscosity and Drug Release

| Gel Concentration (%w/w) | Temperature (°C) | Microviscosity (cP) | Drug Release Rate (μg/cm²/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 25 | 45.2 | 15.8 |

| 0.5 | 37 | 28.7 | 24.3 |

| 1.0 | 25 | 118.5 | 8.5 |

| 1.0 | 37 | 75.6 | 14.1 |

| 2.0 | 25 | 350.9 | 3.2 |

| 2.0 | 37 | 205.4 | 6.9 |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: DLS microviscosity measurement workflow.

Measurement of Polarity and Partitioning

Theoretical Background

The polarity of a drug's microenvironment is a dominant factor influencing its partitioning and passive diffusion across biological barriers like the plasma membrane [28]. A drug's partition coefficient (log P) and its pH-dependent counterpart (log D) are key descriptors of lipophilicity and membrane permeability. The "Rule of 5" highlights the importance of lipophilicity and polarity for orally administered drugs [29]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that account for polarization effects can provide atomistic insights into the permeation behavior of drugs like 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), revealing that the protonation state and a delicate balance with entropic contributions critically govern its membrane partitioning [28].

Experimental Protocol: Determining log D via Shake-Flask Method

Principle: The distribution coefficient (log D) is the ratio of the concentration of a compound in an organic phase (typically n-octanol) to its concentration in an aqueous buffer at a specified pH, usually the physiological pH of 7.4 [29].

Materials:

- n-Octanol (saturated with buffer)

- Aqueous buffer solution (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, saturated with n-octanol)

- Compound of interest

- Centrifuge tubes

- Analytical instrument for quantification (e.g., HPLC-UV)

Procedure:

- Phase Saturation: Pre-saturate the n-octanol and aqueous buffer phases by mixing them in a separatory funnel overnight. Allow the phases to separate and use them for the experiment.

- Partitioning: Add a known amount of the drug compound to a centrifuge tube containing precisely measured volumes of the aqueous and organic phases (e.g., 1:1 ratio). Vortex the mixture for 10-30 minutes to reach partitioning equilibrium.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge the tubes at high speed (e.g., 3000 rpm for 15 minutes) to achieve complete phase separation.

- Quantification: Carefully separate the two phases. Analyze the concentration of the drug in each phase using a validated analytical method like HPLC-UV.

- Calculation: Calculate log D7.4 using the formula: log D = log₁₀ ([Drug]octanol / [Drug]aqueous).

Computational Protocol: MD Simulation for Membrane Permeation

Principle: Free energy calculations from MD simulations can predict the permeation pathway and partition behavior of drugs in lipid bilayers, explicitly considering the polarization effect of the membrane environment [28].

Procedure:

- System Setup: Construct a simulation system of a hydrated lipid bilayer (e.g., POPC) and insert the drug molecule in different protonation states at various starting positions along the bilayer normal.

- Polarizable Force Field: Employ a polarizable force field (e.g., CHARMM with Drude oscillator or AMOEBA) or an implicit polarizable model to account for electronic polarization.

- Free Energy Calculation: Perform unbiased simulations or use enhanced sampling methods (e.g., Umbrella Sampling) to compute the potential of mean force (PMF) or transfer free energy as a function of the drug's position in the membrane.

- Data Analysis: Identify the preferred location (free energy minimum) and the energy barrier for translocation from the PMF profile. Decompose the free energy into entropic and enthalpic contributions.

Applications: This approach was successfully used to show that 2-APB likely switches protonation states along its permeation pathway and that its partition is critically dependent on this polarity, a finding that was extended to 54 analogous compounds [28].

Table 2: Key Parameters from MD Simulation of 2-APB Permeation in POPC Bilayer

| Protonation State | Preferred Location in Membrane | Free Energy Min. (kcal/mol) | Key Interaction/Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral (deprotonated) | Region 4 (Low-density tail region) | -5.2 | Hydrophobic phenyl ring insertion |

| Positively Charged | Region 2 (Head-group region) | -3.1 | Electrostatic interaction with phosphate groups |

Diagram 2: Polarity and partitioning analysis pathways.

Measurement of Acidity (pKa)

Theoretical Background

The acid dissociation constant (pKa) of a drug molecule determines the proportion of its ionized and unionized species at a given pH, directly influencing solubility, lipophilicity (log D), and absorption [29]. A pKa shift in the micro-environment of a DDS, such as within a degrading polymer, can dramatically alter release kinetics. Accurate pKa determination is therefore crucial, though the accuracy is highly dependent on the precision of pH measurement [30].

Experimental Protocol: Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) for pKa Determination

Principle: The electrophoretic mobility (μeff) of an ionizable compound is dependent on its charge, which varies with the pH of the background electrolyte. A plot of μeff versus pH yields a sigmoidal curve from which the pKa can be derived [30].

Materials:

- Capillary electrophoresis system with UV/Vis detector

- Fused-silica capillary

- Series of background electrolytes (BGE) covering a wide pH range (e.g., 2-12)

- Standard compound of known pKa for internal calibration (e.g., FITC)

- Test compound

Procedure:

- Capillary Conditioning: Flush a new capillary sequentially with 1M NaOH (30 min), deionized water (15 min), and running buffer (15 min). Between runs, flush with BGE for 2-3 minutes.

- Mobility Measurement: Dissolve the analyte in each BGE. For each pH, perform CE analysis. Record the migration time of the analyte and a neutral marker (e.g., mesityl oxide) to correct for electroosmotic flow (EOF).

- Data Processing: Calculate the effective electrophoretic mobility (μeff) at each pH using the formula: μeff = (LdLt/V) * (1/ta - 1/teo), where Ld is the detector length, Lt is the total capillary length, V is the voltage, ta is the analyte migration time, and teo is the EOF marker migration time.

- pKa Fitting: Plot μeff against the pH of the BGE. Fit the data to a theoretical mobility-pH model (e.g., using non-linear regression) to determine the pKa value.

Accuracy Consideration: The accuracy of the determined pKa is directly dependent on the accuracy of the pH measurement of the BGE. A pH error of ±0.1 units can lead to a significant pKa error [30]. Using an internal standard (IS-CE) is recommended to mitigate this.

Table 3: Impact of pH Measurement Error on Determined pKa Value

| Actual pH of BGE | Measured pH of BGE | Resulting pKa Error |

|---|---|---|

| 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

| 4.00 | 4.05 | +0.04 |

| 4.00 | 3.95 | -0.05 |

| 7.00 | 7.10 | +0.12 |

| 7.00 | 6.90 | -0.15 |

Diagram 3: Capillary electrophoresis pKa determination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DDS Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Monodisperse Polystyrene Latex Beads | Tracer particles for microviscosity measurement via DLS | Probing the internal microstructure of Carbopol gels [27] |

| n-Octanol (Buffer-Saturated) | Organic phase for experimental determination of log D/log P | Shake-flask method to measure lipophilicity at pH 7.4 [28] [29] |

| POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) | Lipid for constructing model biological membranes in MD simulations | Studying drug permeation and partition behavior [28] |

| Carbopol Polymers | Gel-forming polymer for creating model topical drug delivery systems | Studying the relationship between microviscosity and drug release [27] |

| Internal Standard (e.g., FITC) | Reference compound for calibrating and improving accuracy in CE pKa determination | Correcting for pH measurement inaccuracies in pKa assays [30] |

| Polarizable Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM/Drude, AMOEBA) | Computational models for molecular dynamics simulations | Accurately simulating drug behavior in heterogeneous environments like membranes [28] |

Quantifying Nanoparticle Biodistribution with EPR Spectroscopy

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, also known as Electron Spin Resonance (ESR), is a powerful magnetic resonance technique that selectively detects species with unpaired electrons [31]. In the field of nanomedicine, EPR spectroscopy has emerged as a particularly valuable analytical method for quantifying the biodistribution of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems [31]. This technique provides detailed insights into the structural and dynamic properties of nanoparticles, enabling researchers to track their fate in biological systems with high sensitivity and specificity [31]. The fundamental principle of EPR involves measuring the absorption of microwave radiation by unpaired electrons when a sample is placed in an external magnetic field [31]. For biodistribution studies, this capability allows for the precise quantification of nanoparticle accumulation in various tissues and organs, providing critical data for evaluating targeting efficiency and potential off-target toxicity [32].

The application of EPR spectroscopy is especially relevant for characterizing magnetic nanoparticles (MNP), which contain paramagnetic components that can be directly detected without the need for additional labels [32]. Compared to other analytical techniques, EPR offers significant advantages in sensitivity and specificity, particularly in distinguishing exogenous nanoparticles from endogenous iron species present in biological tissues [32]. This technical note provides a comprehensive overview of EPR protocols for nanoparticle biodistribution quantification, including experimental methodologies, data analysis procedures, and practical considerations for researchers in pharmaceutical development.

Principles of EPR Spectroscopy

Fundamental Theory and Parameters

The underlying principle of EPR spectroscopy is analogous to the more familiar nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), but instead detects the magnetic moments of unpaired electrons rather than atomic nuclei [31]. When placed in an external magnetic field (B~0~), the magnetic moment of an unpaired electron aligns either parallel or antiparallel to the field direction, creating two distinct energy states (M~s~ = -½ and M~s~ = +½) [31]. Continuous-wave EPR spectroscopy involves irradiating the sample with microwave energy at a fixed frequency while systematically varying the magnetic field strength. When the energy difference between the two electron spin states matches the microwave energy, resonance occurs, resulting in absorption of microwave radiation [31].

This energy relationship is described by the fundamental EPR equation: ΔE = hν = gμ~B~B~0~ Where h is Planck's constant, ν is the microwave frequency, g is the g-factor (approximately 2.0023 for a free electron), and μ~B~ is the Bohr magneton [31]. The g-factor is a dimensionless parameter that characterizes the magnetic moment of an unpaired electron in a paramagnetic substance and provides information about the electronic environment, allowing identification of specific radical species [31]. For researchers familiar with NMR, the g-factor is conceptually comparable to the chemical shift parameter.

Additional critical information comes from hyperfine splitting (hfs), which occurs when the unpaired electron interacts with neighboring nuclei that have non-zero nuclear spin (I ≠ 0) [31]. The number of resulting EPR lines follows the relationship: Number of lines = 2nI + 1 Where n represents the number of coupling nuclei and I is the nuclear spin [31]. For example, interaction with a nitrogen atom (^14^N, I = 1) produces a characteristic three-line spectrum, as commonly observed with nitroxide spin labels [31]. Other essential parameters derived from EPR spectra include peak-to-peak linewidth (ΔB~pp~) and signal amplitude (I), with the latter calculated through double integration of the first-derivative EPR spectrum [31].

EPR Spectral Response to Microenvironment

The line shape of an EPR spectrum is highly sensitive to the local environment surrounding the paramagnetic species, providing valuable information about the nanoparticle's microenvironment [31]. For rapidly tumbling species in solution, such as nitroxide radicals, the EPR spectrum displays three narrow lines of nearly equivalent intensity [31]. As molecular motion becomes restricted, such as when nanoparticles accumulate in viscous environments or become internalized by cells, the tumbling rate decreases, leading to line broadening and spectral asymmetry [31]. This effect is particularly evident in the high-field line, which shows decreased amplitude with increasing microviscosity [31]. With further rigidification, such as in solid-state environments, the asymmetry becomes more pronounced [31]. These spectral changes can be quantified to estimate rotational correlation times (τ~c~), providing insights into nanoparticle localization and binding status within biological systems.

Table 1: Key EPR Spectral Parameters and Their Interpretation in Biodistribution Studies

| Parameter | Description | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| g-factor | Dimensionless parameter measuring splitting of energy levels | Identifies specific paramagnetic species and their electronic environment |

| Hyperfine splitting constant (a~N~) | Measure of electron-nuclear interaction | Provides information on microenvironment polarity; increases in polar solvents |

| Linewidth (ΔB~pp~) | Peak-to-peak width of spectral lines | Indicates microviscosity and rotational mobility; broadens with restricted motion |

| Signal amplitude (I) | Intensity of EPR signal | Quantifies concentration of paramagnetic species after double integration |

| Spectral asymmetry | Ratio of low-field to high-field line intensities | Reveals degree of molecular immobilization and environmental rigidity |

Comparative Analytical Techniques

EPR vs. ICP-OES for Nanoparticle Quantification

When evaluating nanoparticle biodistribution, researchers must select appropriate analytical methods based on sensitivity requirements, tissue types, and the specific nanoparticles under investigation. Inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) represents one of the most commonly employed techniques for quantifying metal-containing nanoparticles in biological tissues [32]. However, a critical comparative study has revealed significant differences in performance between ICP-OES and EPR spectroscopy for biodistribution assessment [32].

ICP-OES measures total tissue iron content without distinguishing between exogenous nanoparticles and endogenous iron species such as hemoglobin, transferrin, and ferritin [32]. This lack of specificity becomes problematic in organs with high endogenous iron content, where the background signal can mask the presence of low concentrations of nanoparticles [32]. In contrast, EPR spectroscopy demonstrates greater sensitivity per weight of iron for magnetic nanoparticles compared to endogenous iron-protein complexes, enabling more accurate detection of low nanoparticle concentrations [32].

Validation studies in 9L-glioma bearing rats administered with starch-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (fluidMAG-D) under magnetic targeting revealed distinct correlation patterns between EPR and ICP-OES measurements depending on the level of nanoparticle accumulation [32]. In organs with high MNP accumulation (liver and spleen), results from both techniques showed strong correlation (r = 0.97 and 0.94, respectively), demonstrating methodological equivalency for high concentration ranges (>1000 nmol Fe/g tissue) [32]. However, significant discrepancies emerged in tissues with lower MNP accumulation, including brain, kidney, and tumor tissues [32]. While EPR reliably detected MNP concentrations as low as 10-55 nmol Fe/g tissue, ICP-OES failed to detect nanoparticles in these low-accumulation organs due to masking by endogenous iron背景 [32].

Table 2: Comparison of EPR Spectroscopy and ICP-OES for Nanoparticle Biodistribution Studies

| Characteristic | EPR Spectroscopy | ICP-OES |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Detection of unpaired electrons in paramagnetic species | Measurement of total elemental composition |

| Specificity for Nanoparticles | High specificity for MNP over endogenous iron | Low specificity; measures total iron |

| Sensitivity Range | 10-55 nmol Fe/g tissue (lower range) | >1000 nmol Fe/g tissue (higher range) |

| Sample Processing | Cryogenic handling required | Acid digestion necessary |

| Tissue Compatibility | Challenging for high-iron tissues (liver) | Reliable for high-iron tissues |

| Correlation with EPR | - | Strong in high-accumulation organs (r=0.97 liver) |

| Key Advantage | Superior sensitivity in low-accumulation organs | Established, widely available technique |

Technical Considerations for Method Selection

The choice between EPR and alternative analytical methods depends on several factors, including the nature of the nanoparticles, required sensitivity, and target organs for biodistribution assessment. EPR spectroscopy exhibits particular advantage for studying tissues with naturally low iron content or for tracking low nanoparticle concentrations resulting from targeted delivery strategies [32]. The technique's ability to distinguish nanoparticle-specific signals from biological background interference makes it invaluable for quantifying tumor accumulation, where delivery efficiency is often limited [32].