Charge Trapping Phenomena at Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces: Mechanisms, Modulation, and Biomedical Applications

This article comprehensively explores the charge trapping phenomena at the surfaces of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical factor governing their performance in advanced technologies.

Charge Trapping Phenomena at Perovskite Quantum Dot Surfaces: Mechanisms, Modulation, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the charge trapping phenomena at the surfaces of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs), a critical factor governing their performance in advanced technologies. It covers the fundamental mechanisms, including ionic migration and defect-mediated trapping, and details innovative methodologies like surface ligand engineering for controlling these effects. The review further addresses stability challenges and optimization strategies, such as ionic liquid treatments and heterostructure design, to enhance device reliability. Finally, it examines the validation of these concepts in functional devices like memristors and synaptic transistors, highlighting their significant potential for transforming biosensing, imaging, and neuromorphic computing in biomedical research.

Unraveling the Fundamentals: Mechanisms and Origins of Charge Trapping in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Fundamental Structure of Perovskite Quantum Dots

Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs), particularly all-inorganic halide perovskites like CsPbX₃ (where X = Cl, Br, I), are nanocrystals characterized by a unique crystal structure and size-dependent quantum confinement effects. These materials exhibit a defect-tolerant electronic structure and highly tunable optical properties, making them pivotal for next-generation optoelectronic and photocatalytic technologies [1].

The general crystal structure of PQDs is an extended network of corner-sharing [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedra, with Cs⁺ cations occupying the interstitial spaces. This arrangement creates a three-dimensional framework that dictates their exceptional optoelectronic characteristics. Several vital properties stem from this structure:

- Size- and Composition-Dependent Bandgap: The bandgap of CsPbX₃ PQDs can be tuned by controlling their physical dimensions (typically between 3 nm and 15 nm) and by varying the halide anion composition, allowing precise control over absorption and emission profiles from blue to red wavelengths [2].

- Defect Tolerance: The electronic structure of lead-halide perovskites is characterized by a valence band formed primarily from Pb 6s and I 5p orbitals and a conduction band from Pb 6p orbitals. This unique configuration means that common point defects often form shallow trap states that do not strongly promote non-radiative recombination, leading to high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) that can approach 100% in well-passivated systems [1] [3].

- High Surface-to-Volume Ratio: As quantum dots, PQDs possess an ultrahigh surface-area-to-volume ratio, making their surface chemistry and ligand interactions critically important to their stability and electronic properties [4].

Table 1: Key Structural Characteristics and Property Relationships in CsPbX₃ PQDs

| Structural Feature | Impact on Properties | Typical Range/Values |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Structure | Cubic phase stabilized at nanoscale [2] | Defect-tolerant electronic transport [1] |

| QD Size | Determines quantum confinement strength [2] | 3-15 nm diameter [2] |

| Halide Composition (X) | Directly tunes bandgap and emission wavelength [1] | Cl (blue), Br (green), I (red) mixtures [2] |

| A-site Cation | Affects crystal stability & trap formation [3] | Cs⁺, Formamidinium (FA⁺) [3] |

| Surface-to-Volume Ratio | Dominates chemical reactivity & stability [4] | Extremely high, dictates ligand requirements [4] |

The Critical Role of Surface Chemistry

The surface chemistry of PQDs governs their electronic coupling, dispersibility, environmental stability, and ultimately, their performance in optoelectronic devices. The "soft" ionic nature of perovskite materials and the dynamic equilibrium at their surfaces present both challenges and opportunities for engineering their properties [4].

Ligand Dynamics and Surface Passivation

Colloidally synthesized PQDs are initially capped with long, insulating ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA), which ensure high colloidal stability and near-unity PLQYs. However, these native ligands impede charge transport between neighboring QDs in solid films. Consequently, a ligand exchange process is essential for fabricating functional devices, replacing long ligands with more compact species like halides or pseudohalides [3] [4].

This exchange process profoundly impacts the electronic landscape of the PQDs. Studies on CsPbI₃ PQDs reveal that the ligand exchange introduces a high background free charge carrier concentration and creates electronic traps approximately 150 meV below the conduction band. This explains why the PLQY can drop from over 57% in solution to below 0.1% in ligand-exchanged films, directly limiting the achievable open-circuit voltage (VOC) in solar cells [3].

Impact of A-site Cation Engineering

Replacing a portion of the Cs⁺ with formamidinium (FA�+) represents a powerful surface chemistry strategy. This cation substitution maintains the beneficial high background carrier concentration but reduces the electronic trap density by up to a factor of 40. This reduction in trap-assisted non-radiative recombination directly translates to a lower VOC deficit, pushing device performance closer to the thermodynamic limit [3].

Table 2: Surface Chemistry Effects on Optoelectronic Properties of PQDs

| Surface Modification | Impact on PLQY | Impact on VOC/VOC deficit | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Long Ligands (OA/OLA) | Very High (>57%) [3] | High potential VOC (~1.46 V), not realizable [3] | Excellent surface passivation, poor charge transport [3] |

| Compact Ligand Exchange | Drops significantly (<0.1%) [3] | Realizable VOC ~1.24 V, sets upper limit [3] | Introduces traps but enables charge transport [3] |

| A-site FA+ Incorporation | Improved relative to Cs-only exchanged films [3] | Reduces VOC deficit [3] | Lowers trap density by up to 40x [3] |

| Advanced Stabilization | >95% retention after 30 days under stress [1] | Improves long-term operational stability [1] | Matrix encapsulation, surface passivation [1] |

Advanced Characterization and Experimental Protocols

Understanding charge trapping phenomena at PQD surfaces requires a suite of sophisticated characterization techniques. Photoluminescence-based spectroscopy is particularly powerful for non-contact assessment of recombination losses.

Protocol: Absolute Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) Measurement for QFLS Determination

Objective: To determine the quasi-Fermi level splitting (QFLS), which represents the maximum achievable VOC, by measuring the absolute PLQY of a PQD film at 1 sun equivalent illumination [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Integrating sphere coupled to a calibrated spectrometer

- Continuous-wave laser source with energy above the PQD bandgap

- Neutral density filters

- Samples: PQD films on inert substrates (e.g., glass) at various processing stages

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a set of CsPbI₃ PQD samples:

- Sample A: As-synthesized PQDs in solution (high ligand density).

- Sample B: PQDs spin-cast into a film prior to ligand exchange.

- Sample C: PQD film after solid-state ligand exchange with Pb(NO₃)₂/MeOAc solution.

- Measurement: Place each sample inside the integrating sphere. Illuminate with the laser source, adjusting the intensity using neutral density filters to achieve standard 1 sun conditions (100 mW/cm²).

- Data Collection: Measure the total emitted photoluminescence spectrum and the scattered excitation light from the sample. The absolute PLQY (η) is calculated as the number of photons emitted divided by the number of photons absorbed.

- Data Analysis: The QFLS (or maximum VOC) is calculated from the measured PLQY (η) and the bandgap (Eg) using the following relation, which derives from the fundamental detailed balance principle: QFLS = Eg + kT ln(η) where k is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature.

Interpretation: This protocol allows researchers to pinpoint the stage in processing where the greatest VOC losses occur. For CsPbI₃, the drastic PLQY drop from 5.3% (before exchange) to 0.02% (after exchange) directly identifies the ligand exchange as the primary source of non-radiative recombination, setting a QFLS limit of ~1.24 V [3].

Protocol: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL) for Trap State Analysis

Objective: To characterize carrier recombination dynamics and quantify the density of defect trap states in PQD films [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Pulsed laser source (e.g., Ti:Sapphire)

- Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) module

- High-speed detector

- Temperature-controlled sample stage

Methodology:

- Excitation: Excite the PQD film with a short pulsed laser (e.g., <100 fs pulse width) at a repetition rate suitable for the expected decay dynamics.

- Decay Tracking: Record the photoluminescence intensity as a function of time after the excitation pulse.

- Data Fitting: Fit the resulting decay curve to a multi-exponential model or the stretched-exponential function: I(t) = I₀ exp[-(t/τ)^β], where τ is the decay time and β is the dispersion factor.

- Trap Density Estimation: The average decay time and the dispersion factor (β < 1 indicates a distribution of decay rates, often due to trap states) can be correlated with trap density. A significantly reduced decay time in ligand-exchanged films compared to as-synthesized QDs indicates enhanced non-radiative recombination via traps.

Interpretation: TRPL on ligand-exchanged CsPbI₃ PQDs reveals short carrier lifetimes, confirming the presence of electronic traps. Furthermore, by analyzing the temperature dependence of the TRPL, the trap depth can be determined, which for these systems is found to be circa 150 meV below the conduction band [3].

Synthesis, Stabilization, and Surface Engineering Protocols

Green Synthesis and Ligand Exchange Protocol

Objective: To synthesize CsPbCl₃ PQDs via a hot-injection method and perform a solid-state ligand exchange to create charge-transport-friendly films, reducing environmental impact [1] [2].

Materials:

- Cesium Source: Cs₂CO₃

- Lead Source: PbCl₂ or other Pb-halide salts

- Chloride Source: Specified chloride precursor [2]

- Solvents: 1-Octadecene (ODE)

- Ligands: Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OLA)

- Ligand Exchange Solution: Lead nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) in Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) [3]

Synthesis Procedure:

- Preparation: Load ODE, OA, OLA, and PbX₂ into a flask. Degas and dry under vacuum at 100-120°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Injection: Under inert atmosphere, raise the temperature to the injection temperature (140-200°C). Swiftly inject the Cs-oleate solution.

- Reaction and Quenching: Let the reaction proceed for 5-60 seconds, then cool rapidly in an ice-water bath.

- Washing: Centrifuge the crude solution. Discard the supernatant and re-disperse the pellet in a non-polar solvent (e.g., hexane). Repeat this washing step twice to obtain device-ready PQDs [3] [2].

Solid-State Ligand Exchange:

- Film Casting: Spin-cast a film of the washed PQDs onto a substrate.

- Treatment: While the film is still wet, dynamically spin-cast the Pb(NO₃)₂/MeOAc solution over it.

- Rinsing: Rinse with pure MeOAc to remove byproducts and excess ligands, leaving a compact, conductive PQD film [3].

Advanced Stabilization Strategies

Long-term stability is critical for applications. Advanced strategies have demonstrated retention of over 95% of the initial photoluminescence quantum yield after 30 days under stress conditions (60% relative humidity, 100 W cm⁻² UV light, ambient temperature) [1]. Key approaches include:

- Compositional Engineering: Mixing halides (Br/I) and A-site cations (Cs/FA) to enhance lattice stability [1] [3].

- Surface Passivation: Employing multifunctional ligands (e.g., zwitterions, polymers) that strongly bind to surface sites, reducing desorption and mitigating ion migration [4].

- Matrix Encapsulation: Embedding PQDs within robust inorganic matrices (e.g., oxides) or stable polymer networks to create a physical barrier against moisture and oxygen [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PQD Synthesis and Surface Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Technical Notes & Role in Surface Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Carbonate (Cs₂CO₃) | Cs⁺ cation precursor for all-inorganic PQDs [2] | Forms Cs-oleate upon reaction with OA. The A-site cation influences trap formation [3]. |

| Lead Halides (PbCl₂, PbBr₂, PbI₂) | Pb²⁺ and halide anion source for the perovskite lattice [2] | Stoichiometry and choice of halide determine the final bandgap and stability [1]. |

| 1-Octadecene (ODE) | High-boiling, non-coordinating solvent for hot-injection synthesis [2] | Provides a reaction medium without interfering with the surface ligand binding dynamics. |

| Oleic Acid (OA) | Surface ligand (carboxylic acid) and reaction agent [2] | Binds to surface Pb atoms; initial long ligand providing steric stabilization and high PLQY [3]. |

| Oleylamine (OLA) | Surface ligand (amine) and reaction agent [2] | Binds to surface halide vacancies; works synergistically with OA. Its removal is key for conductivity [4]. |

| Lead Nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) | Agent for solid-state ligand exchange [3] | Provides Pb²⁺ ions to compensate for stripped Pb from the surface, helping to passivate vacancies and introducing halides [3]. |

| Methyl Acetate (MeOAc) | Polar, non-solvent for washing and ligand exchange [3] | Preferentially dissolves and removes long, insulating OA/OLA ligands without dissolving the PQD core, enabling the ligand exchange process [3]. |

Emerging Frontiers: AI and Advanced Surface Design

The field is increasingly leveraging machine learning (ML) to navigate the complex parameter space of PQD synthesis and surface optimization. ML models, including Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Nearest Neighbour Distance (NND), have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting the size, absorbance, and photoluminescence properties of CsPbCl₃ PQDs based on synthesis inputs like injection temperature, precursor amounts, and ligand volumes [2]. This data-driven approach is invaluable for rationally designing surface chemistries that minimize charge trapping.

Future directions focus on developing self-healing ligands and integrating artificial intelligence to facilitate the mass production of PQDs with tailored surface properties. The goal is to reach power conversion efficiencies beyond 20% in PVs by mastering surface chemical design, transforming laboratory breakthroughs into scalable, eco-friendly technologies [1] [4].

Ionic Migration and Defet Dynamics as Primary Trapping Mechanisms

In the pursuit of high-performance optoelectronic devices, organic-inorganic metal halide perovskites (OIMHPs) have emerged as a leading class of materials due to their exceptional photo-physical properties, including strong optical absorption, high photoluminescence quantum yields, and long charge carrier diffusion lengths [5]. Despite rapid advancements in device efficiency, the widespread technological deployment of perovskite quantum dot (PQD)-based devices faces significant challenges related to performance stability and operational consistency. At the heart of these challenges lie two interconnected phenomena: ionic migration and defect dynamics.

These charge trapping mechanisms fundamentally influence the electrical transport properties, recombination pathways, and ultimate device performance across various applications including light-emitting diodes, memory devices, and sensors [5] [6]. In mixed halide hybrid perovskites, the transient ionic dynamics significantly impact steady-state current-voltage characteristics, while thermally activated processes govern the transition of trapped ions into mobile species that participate in conduction mechanisms [5]. Understanding these fundamental processes is thus critical for advancing perovskite quantum dot technologies toward their full commercial potential.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Charge Trapping

Ionic Migration Pathways and Dynamics

Ionic migration in perovskite quantum dots represents a primary trapping mechanism that directly influences charge carrier transport and recombination dynamics. Temperature-dependent dielectric spectroscopy studies on mixed halide perovskites (FAPbBr₂I) have revealed two distinct regimes of ionic conduction with different activation energies [5]. In the low-temperature regime (305-381 K), ionic conductivity depends primarily on hopping frequency, with activation energies for ionic conduction (Eₐ) and hopping migration (Eₘ) both measuring approximately 0.30 ± 0.05 eV [5].

In the high-temperature regime (395-454 K), a significant divergence emerges with Eₐ = 0.74 ± 0.05 eV and Eₘ = 0.50 ± 0.05 eV, indicating an additional energy barrier for mobile charge carrier formation (Ef = Eₐ - Eₘ = 0.24 ± 0.05 eV) [5]. This thermally activated process releases trapped ions, substantially increasing mobile ion concentration and altering the fundamental conduction mechanisms in the material.

Table 1: Activation Energies for Ionic Processes in FAPbBr₂I Single Crystals

| Temperature Regime | Activation Energy Ionic Conduction (Eₐ) | Activation Energy Hopping Migration (Eₘ) | Mobile Carrier Formation Energy (Ef) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Temperature (305-381 K) | 0.30 ± 0.05 eV | 0.30 ± 0.05 eV | Not applicable |

| High Temperature (395-454 K) | 0.74 ± 0.05 eV | 0.50 ± 0.05 eV | 0.24 ± 0.05 eV |

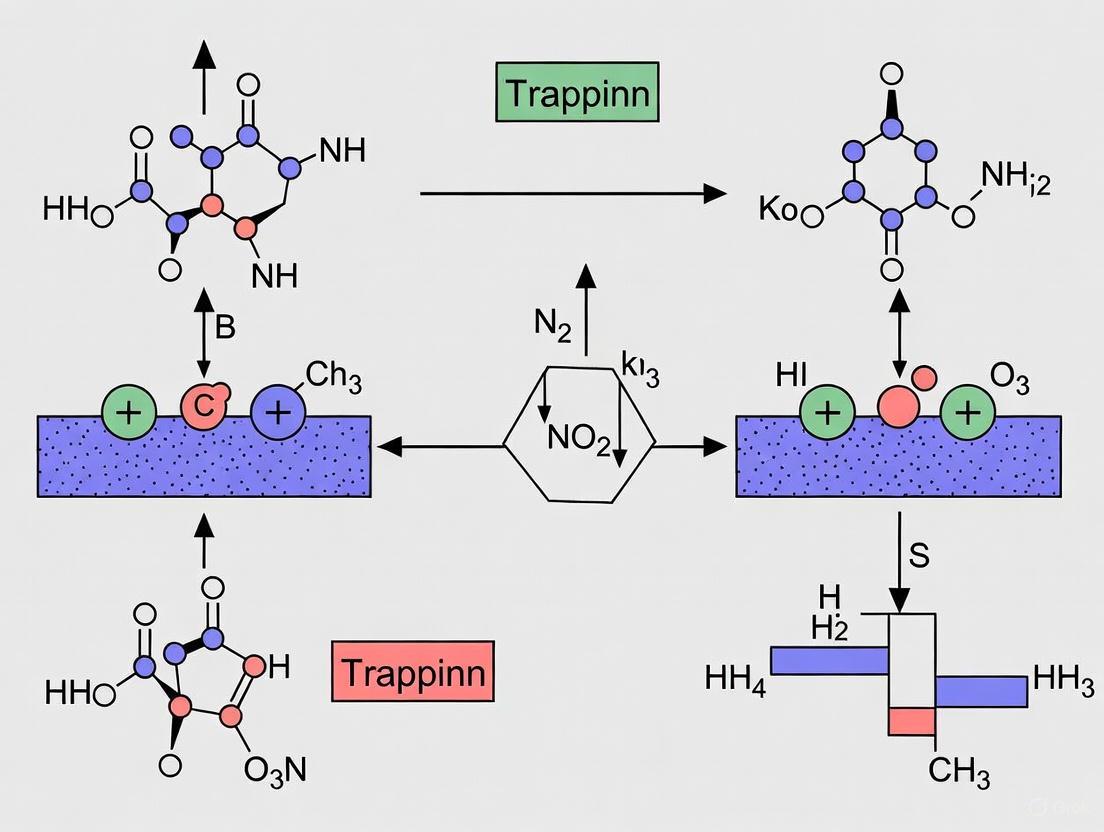

The diagram below illustrates the charge trapping and ionic migration pathways in perovskite quantum dots under electrical bias:

Defect-Mediated Trapping Phenomena

Defect dynamics in perovskite quantum dots create trapping sites that directly capture charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination and reduced device efficiency. PQDs with insulating and defective surfaces exhibit hindered charge injection and massive charge trapping, resulting in slow electroluminescence response times that limit their application in ultra-high refresh rate displays [7]. The presence of these surface defects is particularly problematic in quantum dot systems due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, where surface states can dominate the overall electronic properties.

The intrinsic photosensitivity of perovskite quantum dots further complicates these defect-mediated processes, as photoexcitation can modify the charge state of defects and alter ionic migration barriers [6]. In memory device applications, these defects contribute to resistive switching phenomena through charge trap generation and filling mechanisms [6]. Advanced characterization techniques including temperature-dependent space charge limited current (SCLC) measurements and dielectric spectroscopy have been essential in quantifying these trap states and understanding their dynamic behavior under operational conditions [5].

Experimental Methodologies for Trap Characterization

Temperature-Dependent Dielectric Spectroscopy

Dielectric spectroscopy serves as a powerful, non-destructive technique for probing ionic conduction and relaxation mechanisms in perovskite quantum dots. The experimental protocol for temperature-dependent dielectric characterization involves several critical steps [5]:

Device Fabrication: Synthesize FAPbBr₂I single crystals using the inverse temperature crystallization (ITC) method by dissolving formamidinium iodide (FAI) and lead(II) bromide (PbBr₂) in gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) at 60°C until a clear solution forms [5].

Electrode Deposition: Deposit symmetric Ag electrodes on opposite faces of the single crystal to create an Ag/FAPbBr₂I/Ag device configuration suitable for impedance measurements [5].

Temperature Control: Place the device in a temperature-controlled stage with precise regulation from 305 K to 454 K to investigate thermally activated processes.

Impedance Measurement: Apply an AC voltage signal across the frequency range of 20 Hz to 10 MHz using an impedance analyzer to measure the complex impedance (Z* = Z' - jZ″).

Data Analysis: Analyze Bode plots using the Maxwell-Wagner equivalent circuit model to separate contributions from grain and grain boundary resistance and capacitance. Fit electric modulus loss spectra with Havriliak-Negami (HN) and Kohlrausch-Williams-Watts (KWW) models to understand relaxation mechanisms.

Conductivity Analysis: Process AC conductivity spectra using modified Jonscher's power law to determine hopping frequencies and carrier concentrations in different temperature regimes.

Table 2: Key Parameters from Temperature-Dependent Dielectric Spectroscopy

| Measurement Type | Temperature Range | Key Parameters Extracted | Analytical Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impedance Spectroscopy | 305-454 K | Grain resistance, Grain boundary capacitance | Maxwell-Wagner equivalent circuit |

| Electric Modulus Analysis | 305-454 K | Relaxation times, Activation energies | Havriliak-Negami (HN), Kohlrausch-Williams-Watts (KWW) |

| AC Conductivity | 305-454 K | Hopping frequency, Mobile carrier concentration | Modified Jonscher's power law |

| Space Charge Limited Current | 305-454 K | Trap density, Trap-filled limit voltage | Child's law, Trap-limited conduction models |

Electroluminescence Response Time Measurements

The characterization of electroluminescence (EL) response time provides critical insights into how ionic migration and defect dynamics impact device performance, particularly for display applications requiring fast switching [7]:

Device Fabrication: Fabricate PeLEDs with a structure incorporating [BMIM]OTF-treated perovskite quantum dots as the emissive layer to enhance crystallinity and reduce surface defects [7].

Pulse Voltage Application: Apply long pulse voltage signals to the devices to measure steady-state EL response, defined as the duration from voltage initiation until the EL intensity reaches 90% of its stable value [7].

Light-Emitting Unit Optimization: Reduce the capacitance effect by minimizing the light-emitting unit area to achieve faster response times [7].

Time-Resolved Detection: Use high-speed photodetectors and oscilloscopes to capture the transient EL response with nanosecond resolution.

Data Processing: Analyze rise time characteristics and quantify improvements resulting from surface passivation strategies, with reported reductions of over 75% in rise time after [BMIM]OTF treatment [7].

The experimental workflow for investigating ionic migration and defect dynamics is summarized below:

Mitigation Strategies and Performance Enhancement

Surface Passivation and Interface Engineering

Effective management of ionic migration and defect dynamics requires sophisticated material engineering approaches. Surface passivation has emerged as a particularly powerful strategy, with ionic liquids demonstrating remarkable efficacy in reducing defect-mediated trapping. The introduction of 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) during quantum dot synthesis enhances crystallinity and reduces the surface area ratio of QDs, effectively decreasing defect states and injection barriers at interfaces [7].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations reveal the mechanistic basis for this improvement, showing that the binding energy between OTF− and Pb²⁺ on QD surfaces is -1.49 eV, significantly stronger than the -0.95 eV binding energy of native octanoic acid (OTAC) ligands [7]. This stronger passivation effect suppresses surface defect generation during crystallization, leading to increased photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) from 85.6% to 97.1% and extended exciton recombination lifetime from 14.26 ns to 29.84 ns [7].

Table 3: Performance Enhancement Through Surface Passivation with [BMIM]OTF

| Performance Parameter | Control QDs | [BMIM]OTF-Treated QDs | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | 85.6% | 97.1% | +11.5% |

| Exciton Recombination Lifetime (τₐᵥ𝑔) | 14.26 ns | 29.84 ns | +109% |

| External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) | 7.57% | 20.94% | +176% |

| Device Lifetime (T₅₀ at L₀ = 100 cd/m²) | 8.62 h | 131.87 h | +1430% |

| EL Response Rise Time | Baseline | ~75% reduction | Significant |

Compositional Engineering and Structural Optimization

Compositional manipulation represents another critical strategy for controlling ionic migration and defect dynamics. Mixed halide compositions such as FAPbBr₂I demonstrate enhanced structural stability compared to their single-halide counterparts, effectively arresting ion migration pathways that lead to phase segregation and performance degradation [5]. The partial substitution of iodide with bromide in formamidinium-based perovskites not only increases bandgap but also stabilizes the cubic α-phase structure under ambient conditions for extended periods [5].

Quantum dot dimensionality control further enables optimization of charge trapping behavior. Bandgap engineering through size control and compositional tuning allows manipulation of resistive properties, with larger bandgap PQDs exhibiting higher resistivities beneficial for memory applications [6]. Studies comparing 2D (C₄H₉NH₃)₂PbI₄) and 3D (MAPbI₃) perovskite structures have demonstrated that the larger bandgap 2D material (2.43 eV vs 1.5 eV) reduces leakage current in the high resistance state from 10⁻⁵ A to 10⁻⁹ A, increasing the ON/OFF ratio from 10² to 10⁷ in memory devices [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating Ionic Migration and Defect Dynamics

| Reagent/Material | Chemical Formula/Description | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate | [BMIM]OTF | Ionic liquid additive for surface passivation; enhances crystallinity, reduces defect states, improves carrier injection [7] |

| Formamidinium Iodide | FAI | Organic cation precursor for mixed halide perovskite synthesis; improves thermal stability compared to methylammonium-based perovskites [5] |

| Lead(II) Bromide | PbBr₂ | Metal cation source for perovskite crystal structure; provides Pb²⁺ for [PbX₆]⁴⁻ octahedral framework [5] |

| Gamma-Butyrolactone | C₄H₆O₂ | Solvent for inverse temperature crystallization; enables rapid growth of high-quality single crystals [5] |

| Oleylamine | C₁₈H₃₇N | Surface ligand for quantum dot synthesis; passivates surface defects, modulates charge transfer interactions [8] |

| [2-(9H-carbazol-9-yl) ethyl] phosphonic acid | 2PACZ | Self-assembled monolayer material; reduces interface transport barrier, decreases response time [7] |

| Octanoic Acid | C₈H₁₆O₂ | Native ligand for quantum dots; provides baseline surface coordination with binding energy of -0.95 eV to Pb²⁺ [7] |

Ionic migration and defect dynamics fundamentally govern charge trapping phenomena in perovskite quantum dots, directly influencing device performance across optoelectronic applications. Through advanced characterization techniques including temperature-dependent dielectric spectroscopy and electroluminescence response analysis, researchers have established comprehensive frameworks for understanding these complex processes. The development of effective mitigation strategies—particularly surface passivation using ionic liquids like [BMIM]OTF and compositional engineering in mixed halide systems—has enabled remarkable performance enhancements, including nanosecond response times in light-emitting devices and improved stability in memory applications. As research continues to elucidate the intricate relationship between material structure, ionic transport, and defect behavior, further advances in controlling these primary trapping mechanisms will accelerate the commercialization of perovskite quantum dot technologies.

The Role of Quantum Confinement and Bandgap Tunability

Quantum confinement is a fundamental effect observed in semiconductor nanocrystals, or quantum dots (QDs), when their physical size is reduced to a scale smaller than the Bohr exciton radius. This confinement forces charge carriers (electrons and holes) to exist in discrete energy levels, fundamentally altering the electronic and optical properties of the material from its bulk form [9]. A direct and technologically vital consequence of this effect is bandgap tunability: the ability to precisely control the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands by varying the physical dimensions of the QD [10]. Smaller dots exhibit a wider bandgap, while larger dots have a narrower bandgap [11].

This tunability is a powerful tool for designing optoelectronic devices. However, the high surface-to-volume ratio of QDs means that their surfaces are a dominant source of electronic defects, or charge traps [10] [12]. These traps are localized electronic states that can capture charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination, which diminishes luminescence efficiency, reduces charge carrier mobility, and ultimately degrades device performance and stability [7] [12]. Therefore, understanding and mitigating charge trapping is a central challenge in advancing perovskite QD applications, making surface engineering a critical area of research.

Fundamental Principles of Quantum Confinement

The Physics of Confinement and Tunable Bandgaps

In bulk semiconductors, charge carriers are free to move in all three dimensions, resulting in continuous energy bands. As the semiconductor crystal size decreases to the nanoscale (typically 2–10 nm), the carriers become spatially confined in all three directions [9]. This confinement quantizes the energy levels, analogous to a "particle in a box." The bandgap energy (E_g) of the QD becomes size-dependent and can be described by models such as the Brus equation:

[ Eg(QD) = Eg(bulk) + \frac{\hbar^2 \pi^2}{2 R^2} \left( \frac{1}{me} + \frac{1}{mh} \right) - \frac{1.8 e^2}{4 \pi \varepsilon R} ]

where Eg(bulk) is the bulk bandgap, ħ is the reduced Planck's constant, R is the radius of the QD, me and m_h are the effective masses of the electron and hole, respectively, e is the electron charge, and ε is the dielectric constant [10].

This relationship demonstrates that the bandgap increases as the radius R decreases. This allows for precise tuning of the light absorption and emission wavelengths of QDs simply by controlling their size during synthesis [11] [10]. For example, in CsPbI₃ perovskite QDs, this property enables the stabilization of a photoactive cubic phase that is metastable in bulk form, showcasing how quantum confinement can be leveraged to access new material phases [10].

Visualizing Quantum Confinement and Bandgap Tuning

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of quantum confinement and its effect on the density of states and bandgap energy.

Figure 1: Quantum Confinement Effect on Electronic Structure. As the quantum dot size decreases, the continuous energy bands of the bulk material transition into discrete energy levels, and the bandgap (E_g) widens.

Charge Trapping Phenomena in Perovskite Quantum Dots

Origins and Nature of Surface Traps

The exceptional optoelectronic properties of lead halide perovskite QDs are often tempered by charge trapping at their surfaces. The origins of these traps can be categorized as follows:

- Intrinsic Surface Defects: These arise from imperfect atomic coordination on the QD surface. Common examples include lead (Pb²⁺) cations and halide anions (I⁻, Br⁻) that are not fully passivated by ligands, creating unsaturated "dangling bonds." These sites introduce electronic states within the bandgap that can capture charge carriers [10] [12].

- Extrinsic Surface Defects: These are related to the chemical and physical environment of the QD. They include:

- Unoptimized Surface Ligands: The dynamic binding of long-chain insulating ligands (e.g., oleic acid, oleylamine) can create defects if they desorb, leaving under-coordinated surface atoms. Furthermore, steric hindrance from bulky ligands can prevent complete surface coverage, leaving gaps for trap formation [10] [13].

- Environmental Factors: Exposure to moisture, oxygen, and light can induce surface degradation and create new trap states [12].

A critical distinction is made between shallow traps (ΔE ≤ kBT), which only temporarily localize carriers, and deep traps (ΔE > kBT), which strongly localize charges and act as efficient centers for non-radiative recombination, severely degrading device performance [12].

Impact of Traps on Optoelectronic Properties

Charge traps directly impact key performance metrics of QD devices:

- Reduced Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY): Trap-mediated non-radiative recombination provides an alternative pathway for excitons to decay without emitting a photon, drastically reducing PLQY [7] [13]. For instance, poorly passivated QD inks can have PLQYs as low as 6%, while effective passivation can raise this value to over 97% [7] [13].

- Limited Carrier Diffusion Length (LD): Traps reduce the mobility (μ) and lifetime (τ) of charge carriers. Since LD ∝ √(μτ), a high trap density leads to poor charge extraction in devices like solar cells and slow response times in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [13].

- Slow Response Speed: In light-emitting devices, traps hinder efficient charge injection and lead to a slow rise in electroluminescence (EL) response, which is a critical barrier for high-refresh-rate displays and visible light communication [7].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics Affected by Surface Traps

| Metric | Definition | Influence of Surface Traps | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield (PLQY) | Ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed. | Trap states provide non-radiative recombination pathways, significantly reducing PLQY [7] [13]. | Measured using an integrating sphere. |

| Carrier Diffusion Length (L_D) | Average distance a carrier moves before recombining. | Traps reduce carrier mobility and lifetime, shortening L_D and impairing charge extraction [13]. | Determined from structural and electronic analysis of devices or using the SCLC method [13]. |

| EL Response Time | Time for electroluminescence to reach 90% of its steady-state value. | Traps hinder charge injection and cause a slow rise to steady-state EL, critical for display response speed [7]. | Measured by applying a voltage pulse and monitoring the transient EL output. |

Surface Engineering Strategies to Mitigate Charge Trapping

Surface engineering is the primary strategy for suppressing charge trapping. The following diagram outlines a general workflow for the surface modification of QDs.

Figure 2: Workflow for Surface Modification of Quantum Dots. A multi-step process transforms as-synthesized QDs with long ligands into fully passivated, functional inks.

Ligand Engineering and Exchange

This is the most common technique for tailoring QD surface properties.

Protocol: Standard Solution-Phase Ligand Exchange

- Synthesis: Synthesize QDs (e.g., CsPbBr₃) via hot-injection or ligand-assisted re-precipitation (LARP) methods, stabilized by long-chain ligands like oleic acid (OA) and oleylamine (OLA) [10].

- Purification: Precipitate the QDs from the crude solution using a non-solvent (e.g., acetone or ethyl acetate) and isolate via centrifugation.

- Ligand Exchange: Re-disperse the purified QD pellet in a solvent (e.g., octane) and add a large excess of the desired short-chain ligand (e.g., halide salts like PbI₂ for halogenation, or thiols like 1-thioglycerol for p-type doping). Vigorous stirring is applied to facilitate the displacement of original ligands [13].

- Isolation: Precipitate and centrifuge the QDs to remove the reaction by-products and excess ligands. The final QD pellet can be dispersed in an appropriate solvent for film deposition [13].

Advanced Strategy: Cascade Surface Modification (CSM) The CSM strategy overcomes the limitations of single-step exchange by ensuring complete surface passivation. It involves a two-step process [13]:

- Initial Halogenation: Treat QDs with lead halide anions (e.g., from PbI₂) to achieve a foundational passivation of surface sites, creating n-type CQD inks.

- Surface Reprogramming: Subsequent exchange with functional thiol ligands (e.g., cysteamine) to control doping and solubility, resulting in p-type CQD inks. This method has been shown to triple the PLQY of QD inks compared to conventional methods, from 6% to 18% [13].

Ionic Liquid and Chemical Passivation

Ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as powerful co-passivants due to their dual ionic functionality and high thermal stability.

- Protocol: In-situ Ionic Liquid Treatment for Enhanced Crystallinity [7]

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve the ionic liquid, such as 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF), in chlorobenzene (CB).

- In-situ Addition: Add the IL/CB solution to the lead bromide (PbBr₂) precursor before the QD synthesis reaction.

- Synthesis: Proceed with the standard synthesis (e.g., LARP). The [BMIM]+ cations coordinate with [PbBr₃]− octahedra, slowing nucleation and promoting the growth of larger, more crystalline QDs with a lower surface area ratio.

- Characterization: Use TEM to confirm increased average grain size (e.g., from 8.84 nm to 11.34 nm) and XRD to verify enhanced crystallinity. This treatment can boost the PLQY of QD solutions from 85.6% to 97.1% [7].

Substrate Surface Modification

Ensuring the substrate interface is trap-free is crucial for printed electronics.

- Protocol: Chlorine Passivation of Substrates [14]

- Surface Activation: Clean the substrate (e.g., SiO₂/Si) and treat it with oxygen plasma to create a surface rich in hydroxyl groups and dangling bonds.

- Chlorination: Immerse the activated substrate in an aqueous solution of ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl) for 30 minutes. Other chloride sources like NaCl or tetrabutylammonium chloride can also be used.

- Rinsing and Drying: Rinse the substrate thoroughly with deionized water and dry under a nitrogen stream.

- Verification: Use X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to confirm the presence of a Cl 2p peak, indicating successful passivation. Contact angle measurement will show a significant reduction (e.g., water contact angle of 20° on Cl-modified SiO₂ vs. 96° on OTS-modified SiO₂), confirming a hydrophilic surface suitable for polar QD inks [14].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Surface Trap Passivation

| Reagent / Material | Chemical Formula / Example | Primary Function in Trap Passivation |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Halide Salts | PbI₂, PbBr₂ | Provides halide anions to passivate under-coordinated Pb²⁺ sites, a common deep trap. Used in initial halogenation steps [13]. |

| Bifunctional Thiol Ligands | Cysteamine (HS-(CH₂)₂-NH₂), 1-Thioglycerol | The thiol (-SH) group binds strongly to the QD surface, while the other functional group (-NH₂, -OH) controls solubility and doping character [13]. |

| Ionic Liquids | [BMIM]OTF | Enhances QD crystallinity during growth and passivates surface defects via coordination of both cation ([BMIM]+) and anion (OTF-) to the QD surface [7]. |

| Chloride Compounds | NH₄Cl, NaCl | Passivates trap sites on substrate surfaces (e.g., SiO₂) by terminating dangling bonds, creating a hydrophilic and trap-free interface for QD deposition [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Traps

Accurate characterization of trap density and their impact is essential for evaluating passivation strategies.

Probing Trap Density with Space Charge-Limited Current (SCLC)

The SCLC method is widely used to estimate the density of deep traps (n_trap) in a semiconductor film.

- Detailed Protocol: SCLC Measurement for Trap Density [13]

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a hole-only or electron-only device.

- Hole-only device structure: ITO / PEDOT:PSS / QD Film / MoO₃ / Au.

- Electron-only device structure: ITO / ZnO / QD Film / Al.

- Current-Voltage (I-V) Measurement: Measure the dark I-V characteristics of the device using a semiconductor parameter analyzer.

- Data Analysis: Plot the log(I)-log(V) curve. Identify three distinct regions:

- Ohmic Region (I ∝ V) at low voltages.

- Trap-Filled Limit (TFL) Region where current increases sharply.

- Child's Law Region (I ∝ V²) at high voltages, where all traps are filled.

- Calculation: The trap density ntrap can be calculated from the voltage at the onset of the TFL region (VTFL) using: [ n{trap} = \frac{2 \varepsilon \varepsilon0 V_{TFL}}{e L^2} ] where ε is the relative dielectric constant of the QD solid, ε₀ is the vacuum permittivity, e is the electron charge, and L is the thickness of the QD film.

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate a hole-only or electron-only device.

Evaluating Passivation Efficacy through Photoluminescence

Steady-state and time-resolved photoluminescence provide a rapid, non-destructive assessment of trap states.

- Protocol: Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL)

- Sample Preparation: Deposit a thin, uniform film of the passivated QDs on a clean substrate (e.g., glass).

- Excitation: Excite the sample with a pulsed laser source (e.g., a picosecond diode laser) at a wavelength above the bandgap.

- Detection: Use a single-photon avalanche diode or a streak camera to record the temporal decay of the photoluminescence signal.

- Data Fitting: Fit the decay curve with a multi-exponential function (e.g., tri-exponential). The average lifetime (τavg) is calculated. An increase in τavg after passivation indicates a reduction in non-radiative recombination centers (traps) [7]. For example, the addition of [BMIM]OTF increased the average exciton recombination lifetime of CsPbBr₃ QDs from 14.26 ns to 29.84 ns [7].

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Surface Engineering Strategies

| Surface Engineering Strategy | Key Performance Improvement | Reported Values | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cascade Surface Modification | Increased PLQY of p-type CQD inks | 6% (control) → 18% (CSM) | [13] |

| Ionic Liquid ([BMIM]OTF) Treatment | Increased average exciton lifetime (τ_avg) | 14.26 ns → 29.84 ns | [7] |

| Ionic Liquid ([BMIM]OTF) Treatment | Increased PLQY of QD solution | 85.6% → 97.1% | [7] |

| Halide Passivation + Ligand Reprogramming | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) of CQD solar cell | Record PCE of 13.3% | [13] |

| Cl-passivation of SiO₂ substrate | Reduced contact angle for DMF | 51° (OTS-modified) → 11° (Cl-modified) | [14] |

Quantum confinement provides the foundational ability to precisely tune the bandgap of quantum dots, making them extraordinarily versatile for optoelectronics. However, this very property necessitates a high surface-to-volume ratio, which makes charge trapping at perovskite quantum dot surfaces a central challenge. The research community has developed a sophisticated toolkit of surface engineering strategies—from advanced ligand exchanges and ionic liquid treatments to substrate modifications—to successfully mitigate these traps. As evidenced by the quantitative data, effective passivation leads to dramatic improvements in PLQY, carrier lifetime, and overall device efficiency and stability. Future research will continue to refine these strategies, pushing the performance of QD-based devices toward their theoretical limits and enabling their commercialization in next-generation displays, photovoltaics, and light-communication systems.

Impact of Surface Defects and Grain Boundaries on Charge Retention

In the field of perovskite optoelectronics, charge retention is a critical performance parameter that dictates the efficiency and stability of devices such as solar cells, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and photodetectors. Surface defects and grain boundaries (GBs) in metal halide perovskites (MHPs) and perovskite quantum dots (QDs) serve as primary sites for charge trapping and non-radiative recombination, significantly influencing charge carrier dynamics [15] [16]. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on charge trapping phenomena, provides an in-depth analysis of how these structural imperfections impact charge retention. It further synthesizes advanced passivation strategies and characterization methodologies, presenting consolidated quantitative data and experimental protocols to guide researchers and scientists in developing next-generation perovskite-based devices.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Charge Trapping

Nature and Origin of Defects

The polycrystalline nature of solution-processed perovskite films and the high surface-area-to-volume ratio of QDs inherently lead to the formation of defects. Under-coordinated ions (e.g., Pb²⁺ cations and I⁻ anions) at surfaces and GBs act as charge trapping sites [17] [16]. These sites create energy states within the bandgap, which can be categorized as either shallow traps or deep traps.

- Shallow Traps: Characterized by a low energy depth (typically < 100 meV), shallow traps can temporarily localize charge carriers but re-emit them back to the band edges, thereby extending the apparent carrier recombination lifetime without causing significant non-radiative losses [16].

- Deep Traps: Possessing a larger energy depth, deep traps permanently capture charge carriers, leading to non-radiative recombination and energy loss, which directly diminishes device performance and operational stability [16].

The density and nature of these traps are profoundly influenced by local microstrain at surfaces and GBs. Recent studies indicate that intentionally introduced surface strain can enhance the density of beneficial shallow traps by over 100 times, suggesting these traps are predominantly located at the material's surface [16].

The Dual Role of Grain Boundaries

Historically, GBs were viewed negatively, as regions with high defect density that impede charge transport and promote recombination [15]. However, advanced sub-micrometer characterization of operational devices reveals a more nuanced picture.

In high-efficiency, high-quality perovskite films, GBs can facilitate charge transport. The presence of a built-in electric field in the vicinity of GBs promotes charge separation and establishes channels for rapid carrier transport, leading to locally enhanced photocurrent compared to the grain interiors [15]. Conversely, in low-quality films with a high density of deep traps, GBs continue to act as detrimental sites that quench photoluminescence and trap carriers, resulting in performance degradation [15]. This highlights that the quality of the perovskite film is paramount in determining the ultimate role of its GBs.

Diagram 1: Charge Trapping and Re-emission Pathways. This diagram illustrates the dynamics of free charges, shallow traps within the grain, and deep traps at the grain boundary. The built-in electric field present in high-quality films can enhance charge transport at the grain boundary.

Quantitative Impact on Device Performance

The presence of surface and GB defects directly correlates with key performance metrics in optoelectronic devices. The following tables summarize quantitative data from recent studies, demonstrating the efficacy of various passivation strategies.

Table 1: Impact of Defect Passivation on Perovskite Solar Cell (PSC) Performance

| Passivation Strategy | Device Architecture | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Open-Circuit Voltage (VOC) | Key Performance Change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core-shell PQDs (in antisolvent) | n-i-p PSC | Control: 19.2%Passivated: 22.85% | Control: 1.120 VPassivated: 1.137 V | JSC increased from 24.5 to 26.1 mA/cm²; FF increased from 70.1% to 77% | [18] |

| Graphene QDs (GQDs) in perovskite film | Mesoscopic PSC | Control: ~16.3%Passivated: 17.62% | - | 8.2% relative enhancement in PCE | [19] |

| PQDs at grain boundaries (Capillary effect) | Inverted PSC | Control: 19.27%Passivated: 22.47% | - | - | [20] |

| Surface strain-induced shallow traps | p-i-n PSC | - | - | VOC loss reduced to 317 mV (best-in-class) | [16] |

Table 2: Impact of Defect Passivation on Light-Emitting and Photodetection Devices

| Device Type | Passivation Strategy | Key Performance Metrics | Key Performance Change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite QD LED (PeLED) | Ionic Liquid [BMIM]OTF | EQE: Increased from 7.57% to 20.94%Lifetime (T50): Increased from 8.62 h to 131.87 hResponse Time: Reduced by >75% to 700 ns | Enabled ultra-high resolution of 9072 PPI; Brightness >170,000 cd/m² | [7] |

| Perovskite Photodetector (PD) | CsPbI₃ QD Interlayer | Dark Current: Decreased by 94% (2.04×10⁻⁹ A to 1.17×10⁻¹⁰ A)Specific Detectivity (D*): Increased by 420% to 8.9×10¹² Jones | Responsivity improved by 27% to 0.37 A/W at 605 nm | [21] |

| Perovskite Phototransistor | Fc–β-CD Supramolecular Gate | Rise/Fall Time: 0.18 s / 2.1 sCurrent Stability: Prolonged to 10⁴ s (extrapolated to 10⁹ s) | Low dark current (~10⁻¹¹ A) for low-power operation | [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Defect Analysis and Passivation

Protocol 1: In Situ Passivation of Perovskite QDs with Ionic Liquid

This protocol, adapted from a study achieving nanosecond EL response in PeLEDs, details the use of an ionic liquid to enhance crystallinity and passivate surface defects during QD synthesis [7].

- Synthesis Setup: Conduct all procedures in a nitrogen-filled glovebox.

- Precursor Preparation:

- Prepare a lead bromide (PbBr₂) precursor solution in chlorobenzene (CB).

- Dissolve the ionic liquid 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) in CB at varying concentrations (e.g., to create [BMIM]OTF-1, -2, -3).

- In Situ Crystallization:

- Add the [BMIM]OTF solution to the PbBr₂ precursor to control the nucleation process. The [BMIM]+ cations coordinate with [PbBr₃]− octahedra, slowing nucleation and promoting larger, more crystalline QDs.

- QD Purification: Isolate the resulting QDs via standard centrifugation and redispersion steps.

- Device Fabrication: Spin-cast the passivated QD ink onto substrates for LED fabrication. To achieve ultra-fast response, reduce the device's active area to minimize capacitance effects [7].

Protocol 2: Nanocapillary-Assisted QD Assembly at Grain Boundaries

This protocol describes a method for selectively depositing QDs into the GBs of a polycrystalline perovskite film to passivate interfacial defects [20].

- Film Preparation: Fabricate a polycrystalline perovskite film (e.g., MAPbI₃) using a standard two-step spin-coating procedure.

- QD Ink Formulation: Prepare a colloidal solution of perovskite QDs (e.g., CsPbBrI₂) in a solvent with carefully tuned surface tension (γ) and viscosity (η). The choice of solvent is critical to control capillary action according to the Lucas-Washburn equation.

- Directed Assembly:

- Deposit the QD ink onto the perovskite film.

- During spin-coating, the nanocapillary effect draws the QD solution into the gaps between perovskite grains, leading to the conformal assembly of QDs along the GBs.

- Characterization: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to confirm the selective distribution of QDs at the GBs.

Protocol 3: Characterizing Shallow Traps via Charge Detrapping Measurements

This advanced protocol characterizes the density and impact of shallow traps in working solar cell devices [16].

- Device Biasing: Place the perovskite solar cell under a specified bias voltage in the dark to fill available trap states.

- Stimulus Application: Apply a small voltage pulse or light pulse to the device.

- Current Transient Measurement: Use a high-precision source measure unit to record the subsequent current transient. The current profile contains components from:

- Instantly extracted free charges.

- Charges re-emitted from shallow traps after a temporary delay.

- Permanently trapped charges (deep traps).

- Data Analysis: Deconvolute the transient signal to quantify the proportion of charges that were trapped and then re-emitted, which provides a direct measure of the shallow trap density.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Defect Analysis. This flowchart outlines a comprehensive approach for synthesizing passivated materials and characterizing their structural, optical, and electronic properties to understand defect-charge retention relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Defect Passivation and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Key Consideration / Property |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [BMIM]OTF) | In situ passivation during QD synthesis; enhances crystallinity, reduces surface defects, and improves charge injection [7]. | Positively charged moiety (e.g., imidazolium) coordinates with anionic species on QD surface. |

| Imide Derivatives (e.g., Caffeine) | Surface ligand passivation for QDs; carbonyl group binds to under-coordinated Pb²⁺, suppressing trap states [17]. | Atomic charge of the carbonyl oxygen is proportional to passivation efficacy. |

| Perovskite Quantum Dots (PQDs) | Serve as passivating agents themselves when assembled at GBs of perovskite films; patch charge trapping sites [20] [21]. | Lattice matching with the bulk perovskite film enables effective defect passivation. |

| Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) | Incorporated into perovskite films to passivate GBs and facilitate electron extraction [19]. | Conductivity and functional groups on GQDs contribute to dual passivation and transport role. |

| Core-Shell PQDs (e.g., MAPbBr₃ / tetra-OAPbBr₃) | In situ epitaxial passivation during film formation; shell layer isolates the core and passivates surface defects of the host matrix [18]. | Epitaxial compatibility between core and shell (and host) is critical. |

| Host-Guest Supramolecules (e.g., Fc–β-CD) | Form a structured floating gate in phototransistors; provides uniform charge trapping sites, enhancing stability and response [22]. | Host-guest preorganization creates homogeneous film morphology. |

| Diamine-Terminated Molecules | Introduce controlled surface microstrain in perovskite films; dramatically increases the density of charge-emitting shallow traps [16]. | Amine terminals react with formamidinium (FA+) cations on the perovskite surface. |

Surface defects and grain boundaries in perovskite quantum dots and polycrystalline films are critical factors determining charge retention capabilities. While deep traps at these interfaces are a primary source of performance degradation, emerging research reveals the complex and sometimes beneficial roles of shallow traps and built-in electric fields at GBs in high-quality films. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit summarized in this whitepaper provide a roadmap for advancing the understanding and control of charge trapping phenomena. The strategic passivation of deep traps and the potential engineering of shallow traps present a promising path toward breaking current efficiency and stability barriers in perovskite optoelectronics, aligning with the overarching goals of thesis research in this domain.

Dynamic Fluctuations of Defect Energy Levels at Ambient Temperatures

Charge trapping at the surfaces of perovskite quantum dots (PQDs) is a dominant factor influencing the performance and stability of ensuing optoelectronic devices. Within the context of a broader thesis on this phenomenon, this article addresses a critical and dynamic aspect: the significant fluctuation of defect energy levels at ambient temperatures. Traditional semiconductor physics often treats trap states as static entities, classified simply as "shallow" or "deep." However, emerging research reveals that in soft, ionic materials like metal halide perovskites (MHPs), defect levels are not static but undergo substantial, spontaneous energy shifts due to intense thermal lattice vibrations [23]. These fluctuations, which can span up to 1 eV, fundamentally alter charge carrier dynamics, enabling novel processes like sub-bandgap charge harvesting and energy up-conversion, while also complicating the predictability of device performance [23]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the origins, characterization, and implications of these dynamic defect fluctuations, offering researchers a modern framework for understanding charge trapping in next-generation quantum dot technologies.

Theoretical Foundations and Atomic Origins

The pronounced fluctuation of defect energy levels in MHPs is primarily a consequence of their unique material properties. Unlike conventional semiconductors such as silicon, MHPs are characterized by a low Young's modulus, indicating inherent softness [23]. This mechanical softness translates into strong electron-phonon interactions and significant thermal lattice vibrations, even at ambient temperatures.

Mechanism of Level Fluctuation

At the atomistic level, the energy position of a defect state within the bandgap is intimately tied to the local ionic configuration. The following Dot script illustrates the fundamental difference between static and dynamic defect behavior:

The dynamic bonding environment at the PQD surface, particularly the interaction with surface ligands, plays a crucial role. Ligands like oleylamine (OLA) and oleic acid (OA) dynamically bind to and dissociate from the NC surface, causing transient unpassivated surface sites that can act as temporary trap states [24]. Furthermore, ion migration within the ionic perovskite lattice leads to the creation and annihilation of vacancies, which are primary sources of trap states [24]. The combination of these factors results in a defect energy landscape that is inherently fluid, with trap states that can transiently shift toward or away from band edges, thereby alternating between benign shallow states and detrimental deep traps.

Quantitative Analysis of Defect Dynamics

The scale and impact of these fluctuations have been quantified through advanced computational and experimental methods. Table 1 summarizes the fluctuation characteristics of common defects in MAPbI₃, as revealed by machine-learning-accelerated atomistic simulations [23].

Table 1: Fluctuation Characteristics of Defects in MAPbI₃ at 300 K

| Defect Type | Static (0 K) Position (eV from band edge) | Fluctuation Amplitude (eV) | Proximity to Band Edge | Primary Dynamic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAI (MA replaced by I) | ~0.5 below CBM | ~0.9 | Frequently becomes degenerate with CBM | Enables charge escape and energy up-conversion |

| Pb Interstitial (Pbᵢ) | ~0.5 below CBM | ~0.5 | Never approaches CBM closely | Remains a recombination center |

| I Interstitial (Iᵢ) | ~0.1 above VBM | Small | Remains close to VBM | Facilitates thermal escape to VBM |

| I Vacancy (Iv) | No mid-gap state (at 6.05 Å Pb-Pb distance) | Up to ~1.0 | Forms deep states upon Pb-Pb dimerization | Creates transient deep traps; enables IR absorption |

A critical consequence of these large fluctuations is the blurring of the traditional distinction between shallow and deep traps. A defect that appears deep in a static calculation can transiently become shallow, allowing trapped charges to thermally escape back into the band—a process foundational to energy up-conversion [23]. Conversely, a nominally shallow state can momentarily deepen, capturing a passing charge carrier. The Iodine Vacancy (Iᵥ) exemplifies this dynamic nature, where the spontaneous formation of a Pb-Pb dimer across the vacancy, occurring on a 100 ps timescale, can create a mid-gap state over 1 eV below the conduction band minimum (CBM) [23].

Experimental Manifestations and Measurement Techniques

The dynamic fluctuation of defect levels manifests directly in several experimental observables, most notably in photoluminescence (PL) studies at the single-particle level.

Photoluminescence Fluctuation Patterns

Single-particle PL trajectories reveal distinct patterns, or "signatures," of the underlying charge trapping and detrapping dynamics [24]. The following Dot script maps the relationship between observed PL patterns and their physical origins:

- Blinking: Characterized by abrupt, binary switching between ON (high intensity) and OFF (low intensity) states. This is often attributed to Auger recombination induced by a charged state. When a charge carrier is trapped deeply, the resulting charged NC sees newly generated excitons undergoing non-radiative Auger recombination, quenching PL [24].

- Flickering: Exhibits gradual, multi-state intensity fluctuations. Two primary models explain this:

- Hot Carrier (HC) Trapping: A hot carrier is captured by a shallow trap before relaxing to the band edge, leading to non-radiative recombination. This reduces intensity without significantly altering the PL lifetime [24].

- Non-radiative Band-edge Carrier (NBC) Recombination: The activation/deactivation of multiple shallow recombination centers (e.g., from dynamic ligand binding) varies the non-radiative rate, competing with fixed radiative recombination. This leads to flickering and a positive correlation between PL intensity and lifetime in FLID diagrams [24].

Advanced Measurement Protocols

To accurately characterize these dynamic defects, researchers employ sophisticated protocols that combine sensitive measurement with robust environmental control.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Probing Dynamic Defects

| Protocol Step | Technical Specifications | Purpose & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Disperse PQDs in apolar solvent; mix with polymer (e.g., PMMA, TOPAS); spin-coat onto substrate. | Protects PQDs from ambient moisture/O₂ [24]. Polymer matrix must be soluble in apolar solvents and have low autofluorescence. |

| Single-Particle Spectroscopy | Confocal microscope; pulsed or continuous-wave laser; single-photon avalanche diode (SPAD) detectors; time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC). | Isolates individual PQDs to avoid ensemble averaging, enabling observation of fluctuation heterogeneity [24]. |

| Data Acquisition | Collect PL intensity time traces (ms time bins); simultaneously record photon arrival times for lifetime calculation. | Generates raw data for constructing intensity-time traces and FLID diagrams [24]. |

| Data Analysis | Generate FLID diagrams (2D histograms of PL Intensity vs. Lifetime); categorize fluctuation patterns (blinking/flickering); analyze transition kinetics. | Correlates intensity and lifetime to identify underlying recombination mechanism (e.g., Auger vs. NBC) [24]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful research into dynamic defects requires a carefully selected set of materials and tools. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Defect Fluctuations in PQDs

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Technical Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CsPbX₃ or MAPbX₃ QDs | The primary subject of study; synthesized with controlled size, composition, and surface states. | Bandgap tunable via halide composition (X = Cl, Br, I); defect density is highly synthesis-dependent [25] [24]. |

| Oleylamine (OLA) / Oleic Acid (OA) | Standard surface ligands for colloidal synthesis and stabilization. | Dynamic binding/dissociation can create transient surface traps, contributing to PL flickering [24]. |

| Passivation Ligands (e.g., Didodecyldimethylammonium Bromide - DDAB) | Surface defect passivators; reduce non-radiative recombination centers. | Aims to suppress PL fluctuations by permanently coordinating under-coordinated surface Pb²⁺ ions [24]. |

| Polymer Matrices (PMMA, TOPAS) | Encapsulation medium for single-particle studies. | Protects against environmental degradation; extends measurement duration; must be optically transparent and have low fluorescence [24]. |

| Ab Initio Software (e.g., DFT, TDDFT) | Computational modeling of electronic structure and defect formation energies. | Used to simulate defect properties and their response to lattice distortions [23]. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | Accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. | Enables nanosecond-scale simulations of thermal fluctuations and their effect on defect levels [23]. |

Implications for Device Performance and Stability

The dynamic nature of defect levels has profound and dual-faced implications for PQD-based devices.

Positive Implications: Novel Functionality

- Sub-Bandgap Charge Harvesting & Energy Up-Conversion: The transient shallowing of deep traps allows them to absorb low-energy (infrared) photons. The trapped charge can then thermally escape into the band, contributing to photocurrent. This effectively up-converts sub-bandgap light into usable electronic energy, potentially enhancing the efficiency of solar cells and photodetectors [23].

- Extended Spectral Response: Defect fluctuations can lead to a broadening of the absorption profile, as evidenced by the extension of absorption tails into the infrared for systems with Iᵥ, Pbᵢ, and MAI defects [23].

Negative Implications: Performance Instability

- PL Fluctuations and Efficiency Droop: In light-emitting diodes (LEDs), blinking and flickering directly translate to unstable light output at the nanoscale, which can limit the maximum achievable luminescence efficiency and uniformity [24].

- Memristor Variability: In memory devices, charge trapping and de-trapping due to fluctuating defect levels can lead to stochastic switching behavior and device-to-device variability, posing a significant challenge for the reliability of PQD-based resistive random-access memory (RRAM) and neuromorphic computing systems [25].

The paradigm of dynamic defect energy levels fundamentally reshapes our understanding of charge trapping in perovskite quantum dots. The classification of traps as strictly "shallow" or "deep" is insufficient for these soft, ionic materials; a more accurate description must account for their time-dependent energy landscape. This dynamic behavior explains key experimental observations like PL flickering and enables groundbreaking phenomena such as energy up-conversion.

Future research efforts should focus on several key areas:

- Advanced Passivation Strategies: Developing ligands that not only bind strongly to surface sites but also dampen the local lattice fluctuations responsible for energy level shifts.

- Material Stabilization: Engineering composite structures or alloyed compositions that suppress ion migration, a primary driver of dynamic disorder.

- Exploitation of Dynamics: Intentionally harnessing these fluctuations for novel device concepts, such as energy-up-converting solar cells or neuromorphic sensors that mimic adaptive biological functions.

Grasping the principles outlined in this whitepaper is essential for researchers aiming to push the boundaries of PQD-based optoelectronics, quantum information processing, and neuromorphic computing. The path to more stable and efficient devices lies not only in eliminating defects but also in learning to control and live with their dynamic nature.

Harnessing and Controlling Trapping: Synthesis, Engineering, and Functional Applications

Advanced Synthesis Techniques for Low-Defect PQDs

In the rapidly evolving field of perovskite quantum dot (PQD) research, the control of surface defect states represents a fundamental challenge with far-reaching implications for optoelectronic device performance. Charge trapping phenomena at PQD surfaces directly compromise carrier transport, quantum efficiency, and operational stability across applications ranging from photovoltaics to light-emitting diodes and memory technologies [25] [7]. The synthesis process itself serves as the primary determinant of defect density, with specific reaction pathways governing the formation of surface vacancies, coordinatively unsaturated sites, and structural disorder that facilitate non-radiative recombination [26] [27].

This technical guide examines advanced synthesis methodologies specifically engineered to suppress defect formation at its origin. By addressing the fundamental chemical processes underlying defect generation—particularly amidation side reactions and incomplete precursor conversion—these approaches achieve unprecedented control over PQD surface chemistry and electronic structure. The strategies detailed herein are contextualized within the broader research on charge carrier dynamics, where reduced trap densities directly correlate with enhanced device performance and longevity [27] [7] [28].

Advanced Synthesis Techniques: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Amidation-Retarded Synthesis Strategy

The amidation-retarded synthesis approach directly addresses a primary source of defect generation in conventional PQD synthesis: the unavoidable amidation-induced PbX₂ precipitation at elevated reaction temperatures [27]. This side reaction depletes the ligand pool essential for proper surface passivation and generates defective sites that serve as charge traps.

Core Mechanism: The introduction of covalent metal halides effectively interrupts the amidation pathway by reacting with deprotonated oleic acid and protonated oleylamine. This intervention preserves the free acids/amines necessary to coordinate with PbX₂ and facilitates the formation of regular lead-halide octahedra during nucleation and growth [27].

Experimental Protocol for CsPbI₃ PQDs:

- Precursor Preparation: Combine Cs₂CO₃ with octadecene (ODE) and oleic acid (OA) in a three-neck flask. Heat to 150°C under inert atmosphere until complete dissolution of cesium oleate is achieved.

- Reaction Initiation: In a separate flask, dissolve PbI₂ in ODE at 100°C with continuous stirring under nitrogen flow. Add stoichiometric amounts of covalent metal halides (specific compositions proprietary to the method) to the lead precursor.

- Nucleation and Growth: Rapidly inject the cesium oleate precursor into the lead halide solution maintained at 140°C. The covalent metal halides competitively bind to reactive species that would otherwise initiate amidation.

- Purification: Cool the reaction mixture immediately in an ice bath. Purify the quantum dots through centrifugation with anti-solvents (typically ethyl acetate/acetone mixtures).

- Characterization: The resulting CsPbI₃ PQDs exhibit a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 92% with a significantly reduced defect density of 5.1 × 10¹⁷ cm⁻³ [27].

This method demonstrates universal applicability across red/green/blue emitting PQDs, with corresponding LED devices achieving a maximum external quantum efficiency of 28.71% and solar cells reaching 16.20% power conversion efficiency [27].

Optimized Cesium Precursor with Dual-Functional Ligands

Batch-to-batch inconsistency represents a significant challenge in PQD synthesis, primarily stemming from incomplete precursor conversion and variable surface ligand coverage. This approach utilizes a novel cesium precursor formulation to enhance reproducibility while simultaneously reducing defect-mediated recombination [26].

Core Mechanism: A dual-functional acetate (AcO⁻) moiety serves both to improve cesium salt conversion completeness and act as a surface passivating ligand. When combined with 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as a short-branched-chain ligand, this approach achieves near-complete precursor conversion (98.59% purity versus 70.26% in conventional methods) while providing robust surface coordination [26].

Experimental Protocol for CsPbBr₃ QDs:

- Precursor Engineering: Formulate the cesium precursor by combining cesium carbonate with acetate-containing compounds and 2-hexyldecanoic acid in specific molar ratios (exact proportions optimized for target QD size).

- Reaction Conditions: Inject the optimized precursor into lead bromide solution at room temperature, a significant advantage over high-temperature methods.

- Size Control: Precisely control nanocrystal size through manipulation of the acetate-to-lead ratio and reaction temperature modulation.

- Purification: Isolate QDs through standard centrifugation protocols with minimal ligand loss due to strong binding affinities.

- Performance Metrics: The resulting CsPbBr₃ QDs exhibit uniform size distribution, green emission at 512 nm, 99% PLQY, narrow emission linewidth (22 nm), and enhanced amplified spontaneous emission with a 70% reduction in threshold (from 1.8 μJ·cm⁻² to 0.54 μJ·cm⁻²) [26].

The significantly reduced relative standard deviations for size distribution (9.02% to 0.82%) and PLQY confirm enhanced reproducibility across batches [26].

Ionic Liquid-Assisted Crystallization Control

Ionic liquids provide powerful modulation of crystallization kinetics and surface passivation in PQD synthesis. The method described below utilizes 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate ([BMIM]OTF) to enhance crystallinity and reduce surface area ratio, effectively diminishing defect states and injection barriers [7].

Core Mechanism: The positively charged N+ ions coordinate with Br⁻ ions while the imidazole ring imposes steric hindrance that delays the combination of Cs⁺ cations with [PbBr₃]⁻ octahedra. This moderated nucleation rate promotes growth of larger, more crystalline QDs with lower surface area ratios requiring less ligand passivation [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- In-situ Crystallization: Dissolve [BMIM]OTF in chlorobenzene (CB) and add to the lead bromide precursor solution before cesium injection.

- Concentration Optimization: Systematically vary [BMIM]OTF concentration (Control, [BMIM]OTF-1, [BMIM]OTF-2, [BMIM]OTF-3) to balance nucleation control and final crystal size.

- Size Selection: The average grain size increases progressively from 8.84 nm (Control) to 11.34 nm ([BMIM]OTF-3) with corresponding PL peak red-shift from 517 nm to 520 nm.

- Structural Analysis: XRD confirms maintained monoclinic structure with significantly enhanced (200) crystal plane intensity, indicating directed crystallographic orientation.

- Performance Outcomes: PLQY increases from 85.6% to 97.1% with exciton recombination lifetime (τₐᵥ_g) increasing from 14.26 ns to 29.84 ns, confirming reduced trap-assisted recombination [7].

Density Functional Theory calculations verify the mechanistic basis, showing stronger binding energy of OTF⁻ with Pb²⁺ (-1.49 eV) compared to conventional octanoic acid (-0.95 eV), explaining the enhanced passivation efficacy [7].

Comparative Analysis of Advanced Synthesis Techniques

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Low-Defect PQD Synthesis Techniques

| Synthesis Technique | Defect Density (cm⁻³) | PLQY (%) | Key Advantages | Device Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amidation-Retarded Synthesis [27] | 5.1 × 10¹⁷ | 92% | Suppresses primary defect source; Universal across RGB spectra | LED EQE: 28.71%; PCE: 16.20% |

| Optimized Cs Precursor [26] | Not specified | 99% | Excellent reproducibility; Room temperature synthesis | ASE threshold: 0.54 μJ·cm⁻² |

| Ionic Liquid-Assisted [7] | Significantly reduced | 97.1% | Directed crystallization; Strong ligand binding | LED EQE: 20.94%; Response time: 700 ns |

| Conventional Method | ~10¹⁸ [27] | 70-85% | Established protocol; Simple implementation | Variable performance |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Advanced Low-Defect PQD Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Compounds | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium Precursors | Cs₂CO₃, Cs-Oleate | Quantum dot A-site cation source; Acetate-modified precursors enhance conversion [26] |

| Lead Sources | PbBr₂, PbI₂ | B-site metal cation provision; Halide counterion source [27] |

| Ligands | Oleic Acid (OA), Oleylamine (OAm), 2-Hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) | Surface passivation; Size and morphology control [26] [27] |

| Reaction Modifiers | Covalent metal halides, [BMIM]OTF ionic liquid | Suppress side reactions; Control crystallization kinetics [27] [7] |

| Solvents | Octadecene (ODE), Chlorobenzene (CB) | High-boiling point reaction medium; Precursor dissolution [7] |

Experimental Workflows and Charge Trapping Mitigation Mechanisms

Amidation-Retarded Synthesis Workflow

Diagram 1: Amidation-retarded synthesis prevents defect formation by blocking harmful side reactions during PQD growth.

Ionic Liquid-Mediated Crystallization Pathway

Diagram 2: Ionic liquid modification directs crystallization kinetics toward larger, better-passivated PQDs with reduced charge trapping.

The advanced synthesis techniques detailed in this guide represent significant progress in addressing the fundamental challenge of charge trapping in perovskite quantum dots. By targeting the specific chemical pathways that generate defect states—whether through amidation retardation, precursor engineering, or crystallization control—these methodologies achieve unprecedented reductions in non-radiative recombination centers while enhancing carrier transport properties.