Addressing Surface Contamination in Biomedical Settings: Detection, Challenges, and Advanced Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of surface contamination challenges in biomedical and pharmaceutical environments, with a focus on cytotoxic drug handling.

Addressing Surface Contamination in Biomedical Settings: Detection, Challenges, and Advanced Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of surface contamination challenges in biomedical and pharmaceutical environments, with a focus on cytotoxic drug handling. It explores the foundational risks to health and product integrity, details current and emerging methodological standards for detection, offers strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing decontamination procedures, and discusses validation and comparative analysis of monitoring technologies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes the latest research, standards, and practical insights to enhance safety protocols, ensure regulatory compliance, and mitigate exposure risks in critical work environments.

Understanding the Spectrum and Impact of Surface Contaminants

Surface contamination represents a significant, yet often invisible, threat to experimental integrity, product safety, and occupational health in research and drug development environments. This threat spans multiple domains, from the palpable risk of cytotoxic drug exposure in hospital pharmacies to the subtle interference of trace elements in ultra-sensitive analytical procedures. Contaminants can be defined as any biological, chemical, or radiological substance unintentionally present on a surface that can compromise research results, harm personnel, or damage equipment. The central thesis of modern contamination control is that effective management requires a holistic strategy integrating advanced engineering controls, rigorous administrative procedures, and appropriate personal protective equipment. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to help researchers and scientists identify, troubleshoot, and prevent contamination issues, thereby safeguarding both their work and their well-being.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

### FAQ: Cytotoxic Drug Handling

Q: What is the primary objective of a cytotoxic drug safety program? A: The main objective is to reduce the likelihood of accidental exposure to cytotoxic agents within the entire medication circuit, from the point the drugs enter the institution until they are administered to the patient or disposed of as waste [1]. The fundamental method for protecting workers follows a hierarchy of controls: elimination, substitution, engineering controls, administrative controls, and finally, personal protective equipment (PPE) [1].

Q: What personal protective equipment (PPE) is required for preparing solid oral cytotoxic drugs? A: For counting solid oral forms, personnel must wear a single pair of appropriate gloves. The risk of contamination with oral medications is considered minimal, but consistency in safety practices is crucial [1].

Q: Are there special considerations for pregnant staff handling cytotoxics? A: Yes. All staff should be fully informed of the potential reproductive hazards of cytotoxic drugs. The facility should strongly consider offering alternative duties for women who are pregnant or breast-feeding [1].

### FAQ: General Laboratory Contamination

Q: What are the most common sources of contamination in trace-level elemental analysis (e.g., ICP-MS)? A: The most frequent sources of contamination are [2]:

- Water: Impure water is a major source of ionic contamination.

- Acids and Reagents: Low-purity acids can introduce significant levels of trace elements.

- Labware: Glassware can leach boron, silicon, and sodium; improperly cleaned pipettes retain residues; and tubing can be a source of specific elemental contaminants.

- Laboratory Environment: Airborne dust, particulates from HVAC systems, and shedding from building materials.

- Personnel: Cosmetics, lotions, perfumes, jewelry, and even skin and hair can introduce contaminants.

Q: What is the difference between cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization? A: These represent different levels of decontamination [3] [4]:

- Cleaning: The necessary first step, which is the physical removal of organic matter, salts, and visible soils. This renders a surface safe to handle and is a form of decontamination.

- Disinfection: The process of inactivating most pathogenic microorganisms, but not necessarily all bacterial spores. Levels include high-level, intermediate-level, and low-level disinfection, based on the spectrum of microbes inactivated.

- Sterilization: The complete elimination or destruction of all forms of microbial life, including bacterial spores.

Q: How can I monitor the cleanliness of my surfaces? A: There is no single ideal method, and an integrated approach using trend analysis is recommended. Methods include [5]:

- Visual Inspection: Can be useful as part of an integrated approach but is ineffective in isolation.

- Non-microbial Methods: Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence is highly effective at monitoring residual organic soil.

- Microbial Methods: Traditional microbial swabbing and contact plates indicate residual microbial contamination but not general surface soil.

### Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Cell Culture Contaminants

The following table provides a quick-reference guide for identifying common biological contaminants in cell culture [6].

Table 1: Identification of Common Cell Culture Contaminants

| Contaminant | Visual & Microscopic Signs | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Sudden pH change; cloudiness in medium; sometimes a slight whitish film. Under microscope (100x), granular appearance or small black dots between cells. | Can show motility. Can be distinguished from serum protein precipitates by their regular, particulate morphology. |

| Fungus (Mold) | Filamentous mycelia (thin, thread-like structures); denser clumps of spores. Overtakes a culture as a fuzzy white or black growth visible to the naked eye. | Usually slow-growing but can overwhelm a culture in advanced stages. |

| Yeast | Round or ovoid particles that are smaller than mammalian cells. Often seen as particles "budding" from each other in chains. | In advanced stages, can appear as multi-branched chains of particles. |

| Mycoplasma | No change visible to the naked eye or by standard light microscopy. | Requires specific detection methods (e.g., PCR, specialized agar cultivation showing "fried egg" colonies). |

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Assessment & Control

### Protocol 1: Assessing Surface Contamination by Cytotoxic Drugs

This protocol is adapted from a study evaluating contamination in hospital pharmacies and the efficacy of a closed-system drug-transfer device (CSTD) [7].

1. Objective: To establish baseline levels of surface contamination from intravenous cytotoxic drugs and to assess the effectiveness of an intervention (e.g., a CSTD) in reducing such contamination.

2. Materials:

- Berner International sampling kit or equivalent [7].

- Solvents for wiping (as per analytical method requirements).

- Sample vials and labels.

- Personal protective equipment (PPE) as defined in [1].

- Access to a validated analytical laboratory (e.g., using LC-MS/MS).

3. Sampling Methodology (Wipe Sampling):

- Sampling Time: Collect samples at the end of the day, before routine decontamination of the surfaces [7].

- Sampling Locations: Obtain wipe samples from defined critical surfaces. The European Society of Oncology Pharmacy (ESOP) protocol suggests [7]:

- Inside the biosafety cabinet (BSC)

- Floor in front of the BSC

- Gloves of personnel working under the BSC

- Door handle/knob inside the cleanroom

- Transportation box for ready-to-administer infusions

- Sampling Technique:

- Use a standard template to sample a defined area (e.g., 35 cm x 35 cm = 1225 cm²). If the surface is smaller, record the actual area [7].

- Moisten the wipe with an appropriate solvent.

- Wipe the defined area systematically in three different directions (e.g., horizontal, vertical, and diagonal) to maximize recovery [7].

- Fold the wipe, place it in a vial, seal, and freeze until analysis.

4. Experimental Design:

- Baseline Measurement: Perform wipe sampling across all designated locations before implementing any intervention.

- Post-Intervention Measurement: Implement the intervention (e.g., introduce a CSTD for all cytotoxic drug manipulations). After a predefined period (e.g., 2 weeks or 1 month), repeat the wipe sampling protocol in the exact same locations [7].

- Analysis: Samples are analyzed by a qualified laboratory (e.g., via LC-MS/MS) for a panel of target cytotoxic drugs (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, etc.). Results are typically reported in nanograms per square centimeter (ng/cm²).

5. Data Interpretation:

- Compare the baseline and post-intervention levels for each drug and each surface using statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon test for paired samples) [7].

- A significant reduction in contamination levels post-intervention demonstrates the efficacy of the control measure.

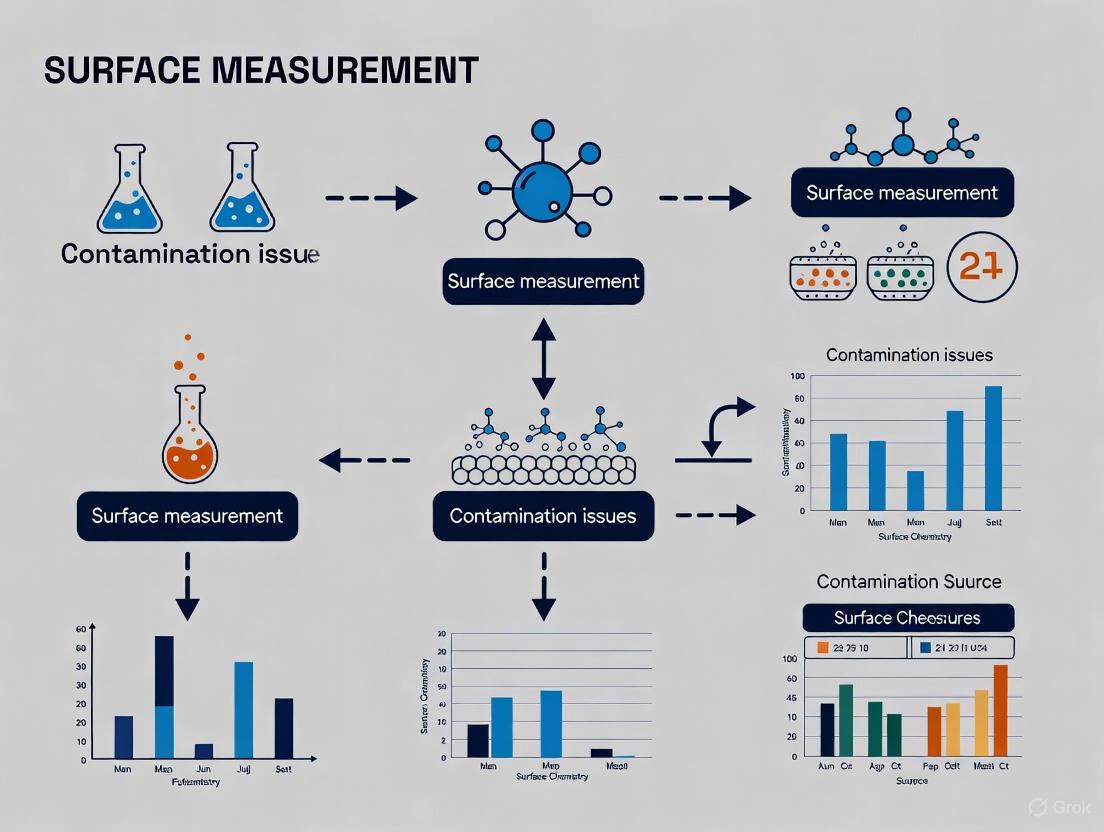

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental process.

### Protocol 2: Controlling Contamination in Trace Element Analysis (ICP-MS)

This protocol outlines best practices for minimizing background contamination during the preparation of samples and standards for ultra-trace elemental analysis [2].

1. Objective: To prepare samples and standards for ICP-MS analysis with minimal introduction of trace elemental contaminants from the laboratory environment, reagents, or labware.

2. Materials:

- Water: ASTM Type I or better ultrapure water [2].

- Acids: High-purity (e.g., ICP-MS grade) acids (nitric acid is relatively clean; hydrochloric acid often has higher impurities) [2].

- Labware: Fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) or quartz containers. Avoid borosilicate glass for analyses of B, Si, Na, etc. [2].

- Environment: Class 100 (or better) clean hood or cleanroom with HEPA filtration is ideal [2].

- Pipettes: Use dedicated, rigorously cleaned pipettes (automated pipette washers are highly effective) [2].

3. Methodology:

- Labware Preparation:

- Sample/Standard Preparation:

- Work in a clean hood whenever possible [2].

- Rinse the outside of all standard and sample containers with ultrapure water before opening to remove surface contamination [2].

- Recap all containers quickly after use to reduce environmental contamination [2].

- Prepare dilutions in FEP or other metal-free plastics [2].

- Use standard addition to compensate for complex sample matrices [2].

- Personnel Practices:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Closed-System Drug-Transfer Device (CSTD) | A drug transfer device that mechanically prohibits the transfer of environmental contaminants into the system and the escape of hazardous drug or vapor concentrations outside the system. It is a critical engineering control for handling cytotoxic drugs [7]. |

| HEPA-Filtered Clean Hood / Biosafety Cabinet (BSC) | Provides a ISO Class 5 clean air environment for manipulating samples and standards, protecting them from airborne particulate contamination. A BSC also provides personnel and product protection for biohazardous work [1] [2]. |

| ASTM Type I Ultrapure Water | Water with the lowest possible levels of ionic and organic contaminants. It is essential for preparing blanks, standards, and samples in trace analysis to prevent contamination from the water itself [2]. |

| ICP-MS Grade Acids | Acids (e.g., HNO₃) certified to have extremely low levels of trace metal impurities. Using lower purity acids can introduce significant contamination that invalidates ultra-trace (ppb/ppt) measurements [2]. |

| Fluoropolymer (FEP) Labware | Containers and vessels made of FEP or similar plastics are inert and minimize leaching of trace elements and adsorption of analytes compared to glass or lower-quality plastics [2]. |

| Wipe-Sampling Kit | A standardized kit (e.g., Berner International kit) used for systematic surface sampling to quantify chemical contamination. Ensures consistent sampling area and technique for reliable data [7]. |

The decision-making process for selecting a decontamination method is guided by the nature of the contaminant and the required safety level, as shown in the following logic diagram.

Table 3: Efficacy of a Closed-System Drug Transfer Device (CSTD) in Reducing Cytotoxic Drug Contamination

This table summarizes quantitative results from a study conducted in 13 hospital pharmacies, showing the reduction in surface contamination (ng/cm²) after implementing a CSTD for a period of 2 weeks to 1 month [7].

| Cytotoxic Drug | Baseline Contamination Level | Post-Intervention Contamination Level | Efficacy of CSTD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) | Detected | Reduced | Significantly Decreased |

| Cyclophosphamide | Detected | Reduced | Significantly Decreased |

| Docetaxel | Detected | Reduced | Significantly Decreased |

| Gemcitabine | Detected | Reduced | Significantly Decreased |

| Paclitaxel | Detected | Reduced | Significantly Decreased |

| Ifosfamide | Detected | Reduced | Significantly Decreased |

| Etoposide | Detected | Reduced | Data available in source [7] |

| Methotrexate | Detected | Reduced | Data available in source [7] |

Note: The study concluded that the use of the CSTD significantly decreased the contamination for 6 of the 8 compounds investigated. The level of contamination was generally higher at baseline than after the intervention [7].

Table 4: Impact of Laboratory Environment on Acid Purity (Contamination in ppb)

This table demonstrates the dramatic effect of the laboratory environment on the purity of reagents, comparing the levels of elemental contaminants in nitric acid distilled in a regular laboratory versus a HEPA-filtered cleanroom [2].

| Elemental Contaminant | Contamination in Regular Lab (ppb) | Contamination in Cleanroom (ppb) |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (Al) | High | Significantly Lower |

| Calcium (Ca) | High | Significantly Lower |

| Iron (Fe) | High | Significantly Lower |

| Sodium (Na) | High | Significantly Lower |

| Magnesium (Mg) | High | Significantly Lower |

Note: The study showed that the acid distilled in the regular laboratory had high amounts of contamination, while the acid distilled in the clean room showed significantly lower amounts of most contaminants [2].

Hospitals are among the most hazardous places to work, with U.S. hospitals recording 221,400 work-related injuries and illnesses in 2019 alone—a rate nearly double that of private industry as a whole [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals investigating surface contamination, understanding the risks posed by Hazardous Medicinal Products (HMOs) is critical. These substances, including antineoplastic drugs, immunosuppressants, and antiviral medicines, present significant carcinogenic, mutagenic, and reprotoxic risks to healthcare workers during preparation, administration, and cleanup [9]. Recent regulatory updates, including the expanded EU Directive 2004/37/EC, now explicitly address these risks with an indicative list of HMPs and mandated safety protocols [9]. This technical support center provides methodologies, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs to support your research into detecting and measuring these hazardous contaminants on surfaces.

Experimental Protocols: Detection of Surface Contamination

Multiplexed Fluorescence Covalent Microbead Immunosorbent Assay (FCMIA)

The FCMIA technique enables simultaneous detection and semi-quantitative measurement of multiple antineoplastic drugs from surface samples, providing a cheaper and faster alternative to traditional LC-MS/MS methods [10].

The diagram below illustrates the FCMIA experimental workflow for detecting surface contamination of antineoplastic drugs:

Detailed Methodology

Surface Sampling Protocol

- Wipe the test surface with a swab wetted with wash buffer (phosphate buffered saline [PBS], 138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, containing 0.05% Tween 20)

- Extract the swab in storage/blocking buffer (PBS, 1% BSA, 0.05% NaN3, pH 7.4)

- Analyze the extract using FCMIA [10]

Microsphere Preparation

- Use 5.6μm carboxylate-modified microspheres with internal red and infrared fluorochromes

- Activate carboxylate groups with EDC and NHS in activation buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, pH 6.2)

- Couple drug-BSA conjugates (5-fluorouracil-BSA, doxorubicin-BSA, paclitaxel-BSA) to unique microsphere sets in coupling buffer (0.05 M MES, pH 5.0) [10]

Multiplexed Assay Procedure

- Perform competitive assay in 1.2μm filter membrane microtiter plates

- Incubate with primary anti-drug monoclonal antibodies

- Add biotin-labeled anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody

- Bind streptavidin R-phycoerythrin fluorescent label

- Analyze using LUMINEX 100 instrument, collecting data from 100 microspheres per analyte

- Determine median fluorescence intensity (MFI) for quantification [10]

Standard Curves and Quantification

Prepare standard solutions at 8 concentrations for calibration as shown in the table below:

Table 1: Standard Solution Concentrations for FCMIA Calibration

| Standard Solution | 5-Fluorouracil (ng/mL) | Paclitaxel (ng/mL) | Doxorubicin (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1000 | 100 | 2 |

| 2 | 500 | 50 | 1 |

| 3 | 250 | 25 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 125 | 12.5 | 0.25 |

| 5 | 62.5 | 6.25 | 0.125 |

| 6 | 31.25 | 3.125 | 0.0625 |

| 7 | 15.6 | 1.5625 | 0.0312 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Construct standard curves using four-parameter logistic-log fits for quantification of unknown samples [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Antineoplastic Drug Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylate-modified microspheres | Solid support for covalent attachment of biomolecules; enable multiplexing through internal fluorochromes | Luminex Corporation |

| Drug-BSA conjugates (5-fluorouracil-BSA, doxorubicin-BSA, paclitaxel-BSA) | Capture antigens for competitive immunoassay | Saladax Biomedical |

| Monoclonal anti-drug antibodies | Primary antibodies for specific drug detection | Saladax Biomedical, Lampire Biological Laboratories |

| EDC and Sulfo-NHS | Activation of carboxylate groups on microspheres for biomolecule coupling | Pierce Biotechnology, Inc. |

| Biotin-labeled anti-mouse IgG | Secondary antibody for signal amplification | Pierce Biotechnology, Inc. |

| Streptavidin R-phycoerythrin | Fluorescent label for detection | Molecular Probes |

| Filter membrane microtiter plates | Platform for assay with built-in wash capabilities | Millipore Corp. (MABVN1250) |

Safety Protocols and Regulatory Framework

Recent EU OSHA updates (Directive 2004/37/EC) establish significant new requirements for handling Hazardous Medicinal Products (HMPs) with carcinogenic, mutagenic, or reprotoxic properties [9].

Employer Responsibilities and Safety Systems

The diagram below outlines the comprehensive safety approach required for HMP handling:

Key Regulatory Changes

Addition of Reprotoxic Substances: Reprotoxic substances are now fully recognized under the CMR framework, amplifying protection for workers handling substances linked to fertility issues, birth defects, or developmental disorders [9]

Indicative List of HMPs: First EU-endorsed indicative list includes antineoplastics, immunosuppressants, and antiviral medicines classified as Category 1A or 1B carcinogens, mutagens, or reprotoxic agents [9]

Expanded Employer Obligations: Mandates for robust safety protocols including regular worker training, detailed risk assessments, substitution of hazardous substances where feasible, and use of closed systems to prevent exposure [9]

Performance Data and Detection Limits

Table 3: FCMIA Detection Limits for Antineoplastic Drugs

| Antineoplastic Drug | Limit of Detection (LOD) (ng/cm²) | Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) (ng/cm²) | Commercial Preparation Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Fluorouracil | 0.93 | 2.8 | 50 mg/mL |

| Paclitaxel | 0.57 | 2.06 | 6 mg/mL |

| Doxorubicin | 0.0036 | 0.013 | 2 mg/mL |

The extreme sensitivity of the FCMIA method is particularly valuable given the high concentration of commercial drug preparations, where even minimal spillage can cause significant contamination [10].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges

Q: We're observing high background signal in our FCMIA results. What could be causing this and how can we address it?

A: High background often stems from incomplete washing steps or nonspecific antibody binding. Ensure thorough washing between assay steps using appropriate wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20). Optimize antibody concentrations and include appropriate controls. Verify that your storage/blocking buffer (PBS, 1% BSA, 0.05% NaN3) is fresh and properly prepared [10].

Q: Our surface recovery rates for antineoplastic drugs are inconsistent. How can we improve sampling reliability?

A: Standardize your swabbing technique using consistent pressure and pattern. Ensure swabs are adequately wetted with wash buffer but not oversaturated. For porous surfaces, increase sampling area. Extract swabs immediately after collection and analyze promptly to prevent degradation. Validate your recovery efficiency for different surface types [10].

Q: What are the critical safety thresholds for surface contamination of antineoplastic drugs in healthcare settings?

A: While regulatory standards for surface contamination are still evolving, your research should aim for detection of less than 1 ng/cm² and measurement of less than 5 ng/cm² for multiple antineoplastic drugs. These levels are useful in assessing contamination to control exposure, particularly given that studies show workplace contamination persists despite safe handling practices [10].

Regulatory and Compliance FAQs

Q: How do the recent EU OSHA updates affect our research on surface contamination of HMPs?

A: The 2025 EU OSHA update establishes an indicative list of HMPs and emphasizes closed systems for exposure prevention. Your research should align with these guidelines by validating detection methods for the listed HMPs and evaluating the effectiveness of engineering controls like Closed System Transfer Devices (CSTDs). Reference the official indicative list (COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION, C/2025/1150) in your methodology [9].

Q: What health surveillance data should we collect to correlate with surface contamination findings?

A: Studies reveal nurses handling cytotoxic drugs are three times more likely to develop malignancies compared to those not exposed. Collect data on short-term health effects (skin irritation, respiratory issues) and long-term outcomes (cancer incidence, reproductive issues) while maintaining participant confidentiality. Correlate this with both personal exposure monitoring and surface contamination data [9].

The detection and measurement of surface contamination by hazardous drugs represents a critical component of protecting healthcare workers from carcinogenic, mutagenic, and reproductive hazards. The FCMIA methodology provides researchers with a sensitive, specific, and practical approach for simultaneous detection of multiple antineoplastic drugs. As regulatory frameworks evolve to address these risks, your research plays a vital role in establishing evidence-based safety protocols and contamination control measures. By implementing these methodologies and troubleshooting guides, you contribute to the broader thesis of addressing contamination problems in surface measurements research while enhancing workplace safety for healthcare professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What do recent surveillance data indicate about respiratory virus activity in healthcare settings? Recent data from England (May 2025) shows respiratory viruses circulating at baseline levels. COVID-19 PCR positivity in hospital settings was 5.6%, influenza positivity was 1.5%, and RSV positivity was 0.2%. These figures help researchers contextualize the background prevalence of viruses that could potentially contaminate surfaces in medical environments [11].

Q2: How sensitive are modern methods for detecting surface contamination by antineoplastic drugs? Fluorescence Covalent Microbead Immunosorbent Assay (FCMIA) can simultaneously detect multiple drugs with high sensitivity. Limits of Detection (LOD) for common agents are:

- Doxorubicin: 0.0036 ng/cm²

- Paclitaxel: 0.57 ng/cm²

- 5-Fluorouracil: 0.93 ng/cm² This sensitivity is crucial for monitoring hazardous drug residues on work surfaces [10].

Q3: What is a cost-effective approach for ongoing surveillance of pathogen prevalence? Studies comparing surveillance systems found that lower-cost methods like the Virus Watch study (costing £4.89 million) can effectively track positivity and incidence rates, showing strong synchrony (Spearman ⍴: 0.90-0.92) with more expensive, gold-standard systems like the ONS COVID-19 Infection Survey (costing £988.5 million). This demonstrates that robust surveillance is possible in resource-limited settings [12].

Table 1: Recent Respiratory Virus Positivity Rates in Hospital Settings (England, May 2025)

| Virus | Positivity Rate | Trend | Hospital Admission Rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 5.6% (PCR) | Stable | 1.38 |

| Influenza | 1.5% (weekly mean) | Decreasing | 0.37 |

| RSV | 0.2% | Stable | Reporting concluded |

| Rhinovirus | 12.1% | Stable | Not specified |

| Adenovirus | 3.8% | Decreasing slightly | Not specified |

| hMPV | 1.7% | Decreasing | Not specified |

Source: UK Health Security Agency National Flu and COVID-19 Surveillance Report [11]

Table 2: Detection Limits for Antineoplastic Drug Surface Contamination Using FCMIA

| Antineoplastic Drug | Limit of Detection (LOD)(ng/cm²) | Limit of Quantitation (LOQ)(ng/cm²) | Commercial Preparation Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | 0.0036 | 0.013 | 2 mg/ml |

| Paclitaxel | 0.57 | 2.06 | 6 mg/ml |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 0.93 | 2.8 | 50 mg/ml |

Source: Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice [10]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiplexed Surface Detection of Antineoplastic Drugs Using FCMIA

Purpose: Simultaneous detection and semi-quantitative measurement of multiple antineoplastic drugs on workplace surfaces [10].

Materials:

- Carboxylate-modified microspheres (5.6 μm diameter)

- Drug-BSA conjugates (5-fluorouracil-BSA, doxorubicin-BSA, paclitaxel-BSA)

- Monoclonal antibodies specific to each drug

- Biotin-labeled anti-mouse IgG

- Streptavidin R-phycoerythrin

- EDC and sulfo-NHS in activation buffer (0.1 M NaH₂PO₄, pH 6.2)

- Coupling buffer (0.05 M MES, pH 5.0)

- Storage/blocking buffer (PBS, 1% BSA, 0.05% NaN₃, pH 7.4)

Methodology:

- Surface Sampling: Wipe the measured surface area with a swab wetted with wash buffer.

- Sample Extraction: Extract the swab in storage/blocking buffer.

- Microsphere Preparation: Activate carboxylate groups on microspheres with EDC/NHS mixture. Covalently couple each drug-BSA conjugate to unique microsphere sets.

- Multiplexed Assay: Perform competitive assay where drugs in sample extracts compete with microsphere-bound drug-BSA conjugates for anti-drug antibodies.

- Detection: Incubate with biotin-labeled secondary antibody followed by streptavidin R-PE.

- Analysis: Analyze using Luminex instrument; measure median fluorescence intensity (MFI). Decreased signal indicates higher drug concentration.

Typical Analysis Time: <15 minutes from sampling to results [10].

Protocol 2: Low-Cost Community Surveillance for Pathogen Positivity Rates

Purpose: Estimate community positivity and incidence rates using a cost-effective methodology [12].

Materials:

- Online survey platform (e.g., REDCap)

- Access to national testing data (where available)

- Participant recruitment materials

- Data linkage agreements with health authorities

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: Enroll households with internet access and ability to complete regular surveys (English proficiency required).

- Data Collection: Collect self-reported symptom data, test results, and demographic information through regular surveys.

- Data Linkage: Where possible, link participant data to national COVID-19 testing, vaccination, and hospital admission records.

- Rate Calculation: Calculate positivity rates from both self-reported and linked national testing data.

- Validation: Compare rate estimates with gold-standard surveillance systems using Spearman correlation for global and local synchrony.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Surface Contamination Analysis Workflow

Surveillance System Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Surface Contamination Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylate-Modified Microspheres | Solid support for covalent attachment of biomolecules; internally dyed for spectral addressability | Multiplexed detection of multiple analytes simultaneously in FCMIA [10] |

| Drug-BSA Conjugates | Immobilized antigens that compete with sample analytes for antibody binding | Critical for competitive immunoassay format used in surface contamination detection [10] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Specific recognition elements that bind target analytes with high affinity | Enable specific detection of individual antineoplastic drugs in complex samples [10] |

| Biotin-Labeled Secondary Antibodies | Amplification reagents that bind primary antibodies | Signal enhancement in immunochemical detection methods [10] |

| Streptavidin R-Phycoerythrin | Fluorescent reporter for detection and quantification | Provides measurable signal proportional to analyte concentration in FCMIA [10] |

| EDC and Sulfo-NHS | Cross-linking agents for covalent immobilization | Activation of carboxylate groups on microspheres for biomolecule conjugation [10] |

| Linked National Testing Data | Validation and enhancement of self-reported infection data | Improves accuracy of positivity rate estimates in surveillance studies [12] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Surface Contamination Research

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in surface contamination measurement, framed within a broader thesis on amending contamination problems in surface measurements research.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Our surface sampling for antineoplastic drugs shows inconsistent results between replicates. What are the potential causes?

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Inconsistent Swab Technique: The pressure, pattern, and wetness of the swab during surface sampling must be standardized. A common method is to wipe the entire surface with a swab wetted with wash buffer, using a consistent, overlapping "S" pattern while applying firm, even pressure [10].

- Incomplete Surface Extraction: After sampling, the swab must be properly extracted in an appropriate storage/blocking buffer to ensure the analyte is fully released for measurement [10].

- Cross-Contamination of Samples: Ensure that fresh swabs are used for each sample and that gloves are changed between replicates to prevent carry-over contamination [13].

- Degraded Reagents: Check the expiry dates of all reagents, including antibodies, fluorescent labels, and buffer solutions. Using reagents past their expiry can lead to diminished assay signals and unreliable data [13].

FAQ 2: We are detecting microbial contamination on surfaces that appear visually clean. How should we interpret this, and what are the next steps?

- Interpretation & Next Steps:

- Interpretation: Visually clean surfaces can still be heavily contaminated. Low or undetectable pathogen concentrations on high-touch surfaces should not be interpreted as an absence of pathogen spread via surface touch. These surfaces can act as key nodes with high 'flux,' facilitating microbial transmission despite moderate contamination levels [14].

- Next Steps:

- Review Cleaning Protocols: Ensure that cleaning is always performed before disinfection, as dirt and organic matter can shield microorganisms [13] [15].

- Validate Disinfectant Contact Time: Confirm that the disinfectant remains wet on the surface for the entire manufacturer-recommended contact time to achieve effective kill [13] [15].

- Evaluate Sporicidal Use: In critical environments, incorporate a sporicidal agent into the disinfection rotation to control resilient pathogens like C. difficile [13] [16].

FAQ 3: Our environmental monitoring in a cleanroom is consistently failing due to airborne particulate matter. What areas should we investigate?

- Investigation Checklist:

- Gowning Procedures: Re-train personnel on aseptic gowning practices. Failure to don gowns, gloves, and hair covers correctly is a primary source of human-shed particulates [13].

- Material Transfer: Verify that all materials entering the cleanroom are properly disinfected at the point of transition from a lower-classified area to a higher-classified area [13].

- Facility Integrity: Inspect the room for insanitary conditions, including unsealed or loose ceiling tiles, damaged wall panels, and standing water, all of which can contribute to particulate shedding and microbial growth [13].

- Equipment: Audit equipment brought into the cleanroom to ensure it is non-porous, non-particle-generating, and easy to clean [13].

Experimental Protocols for Surface Measurement

Protocol: Multiplexed Measurement of Surface Contamination by Antineoplastic Drugs using FCMIA

This protocol enables simultaneous detection and semi-quantitative measurement of multiple antineoplastic drugs (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, paclitaxel, doxorubicin) from surfaces [10].

1. Principle A fluorescence covalent microbead immunosorbent assay (FCMIA) is used. In this competitive immunoassay, drug residues extracted from a surface compete with drug-protein conjugates immobilized on color-coded microspheres for a limited amount of anti-drug antibody. The signal detected is inversely proportional to the amount of drug present on the surface [10].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Drug-BSA Conjugates: 5-fluorouracil-BSA, doxorubicin-BSA, paclitaxel-BSA.

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Specific to each target drug.

- Carboxylated Microspheres: Different sets with unique internal fluorescent signatures.

- Coupling Buffers: Activation buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, pH 6.2) and coupling buffer (0.05 M MES, pH 5.0).

- Assay Buffers: Wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) and storage/blocking buffer (PBS with 1% BSA and 0.05% NaN3).

- Detection Reagents: Biotin-labeled anti-mouse IgG and Streptavidin R-Phycoerythrin (Streptavidin R-PE).

- Sampling Kit: Swabs and containers for surface sampling.

- Luminex Instrumentation: A flow-based system, such as a LUMINEX 100, for reading the multiplexed assay.

3. Procedure

- Surface Sampling: Wipe the target surface systematically with a swab wetted with wash buffer. Extract the swab in storage/blocking buffer [10].

- Microsphere Coupling (if required): Covalently couple each drug-BSA conjugate to a unique set of activated microspheres using EDC and NHS chemistry [10].

- Multiplexed Assay Execution:

- Incubate the sample extract with a mixture of conjugated microspheres and primary anti-drug antibodies.

- Wash to remove unbound components.

- Incubate with biotin-labeled secondary antibody.

- Wash again.

- Incubate with Streptavidin R-PE.

- Perform a final wash and resuspend the microspheres for reading.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: The Luminex instrument reads the internal fluorescence of each microsphere to identify it and measures the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the surface-bound R-PE. Standard curves are generated from known drug concentrations, and sample concentrations are interpolated from these curves [10].

4. Expected Results and Limits of Detection The following limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) have been achieved for this method on the surfaces studied [10]:

Table 1: Assay Sensitivity for Key Antineoplastic Drugs

| Drug | Limit of Detection (LOD) (ng/cm²) | Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) (ng/cm²) |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Fluorouracil | 0.93 | 2.8 |

| Paclitaxel | 0.57 | 2.06 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.0036 | 0.013 |

Workflow Visualization: FCMIA for Surface Contamination

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and principle of the FCMIA for detecting surface contamination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Surface Contamination Research via FCMIA

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Drug-BSA Conjugates | Conjugated proteins immobilized on microspheres to capture specific antibodies in the competitive FCMIA [10]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Bind specifically to target drug analytes; the key reagent determining assay specificity [10]. |

| Carboxylated Microspheres | Solid support with internal color-coding for multiplexing and surface carboxyl groups for biomolecule conjugation [10]. |

| Biotin-labeled Anti-IgG | Secondary antibody that binds to the primary drug-specific antibody, enabling signal amplification via streptavidin [10]. |

| Streptavidin R-Phycoerythrin | Fluorescent reporter that binds to biotin, producing the measurable signal for quantification [10]. |

| Sporicidal Disinfectant | A disinfectant effective against bacterial spores (e.g., chlorine-based) used to decontaminate surfaces and control pathogens like C. difficile in experimental settings [13] [16]. |

| High-Touch Surface Markers | Not a reagent, but a critical reference. Common high-touch surfaces (bed rails, IV poles, bedside tables) are key study targets for contamination mapping and sampling [17] [16]. |

Implications for Product Integrity and Cross-Contamination in Sensitive Manufacturing

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

What are the most common root causes of cross-contamination in a manufacturing environment?

The most common root causes can be categorized by their origin [18] [19]:

- Human Handling: Operators can transfer contaminants via dirty hands or contaminated clothing [18].

- Shared Equipment: Using the same machine or utensils for different products without proper cleaning is a frequent cause [18].

- Ineffective Cleaning: This includes inefficient use of cleaning agents, ineffective application of sanitation principles, and the presence of difficult-to-clean "niche environments" in equipment where bacteria can thrive [20].

- Environmental Factors: Airborne particles can transport contaminants, and work surfaces not disinfected between batches pose a risk [18].

- Raw Materials: Ingredients can be a source of contamination if stored together without proper separation or received from non-compliant suppliers [18].

Why might our current cleaning protocols be failing, even when followed?

Your protocols might be failing due to several subtle reasons [20]:

- Niche Environments: Bacteria can establish in sites like hollow conveyor rollers, cracked seals, or between close-fitting parts that are impossible to reach with normal cleaning [20].

- Biofilms: Bacteria can form slime layers on surfaces that protect them from conventional cleaning and sanitizing methods. Adequate physical cleaning to remove biofilms prior to sanitation is crucial [20].

- Ineffective Training: Training may be too generic, language barriers may exist, or the wrong personnel may be trained, reducing the effectiveness of cleaning execution [20].

- Poor Equipment Design: Equipment that lacks sanitary design, with materials that are not easily cleanable or parts that are not readily accessible, can undermine cleaning efforts [20].

We regularly test high-touch surfaces and find low pathogen levels. Does this mean the risk of contamination spread is low?

Not necessarily. A key node in microbial dissemination can exhibit moderate or even low contamination levels because they are frequently touched [14]. The high frequency of touch means these surfaces have a high "flux"—they can either contaminate a clean hand or be "cleaned" by a clean hand. Therefore, undetectable or low pathogen concentrations on high-touch surfaces should not be interpreted as an absence of risk for pathogen spread via surface touch [14].

What advanced methods can detect contamination that is invisible to the human eye?

Optical imaging methods using safe visible light, such as hyperspectral scanning, show promise. This technique can reveal human-eye invisible stains by utilizing the intrinsic fluorescence properties of biological contaminants and organic soils [21]. These systems use algorithms, including machine learning, to detect contamination "fingerprints" in the electromagnetic spectrum, allowing for real-time cleanliness evaluation [21].

Contaminant Types and Control Measures

The table below summarizes the primary categories of contaminants and methods to control them, drawing from food and pharmaceutical manufacturing principles [22].

| Contaminant Type | Common Examples | Primary Control Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Pesticides, cleaning agents, lubricants, allergen residues [20] [22] | Regular equipment checks and maintenance; proper rinsing/cleaning validation; supplier verification and ingredient testing [22]. |

| Physical | Metal fragments, plastic, wood, pest-related matter [22] | Use of X-rays, metal detectors, sifting; Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs); a food defense plan [22]. |

| Microbial | Pathogenic bacteria (e.g., L. monocytogenes), viruses, molds [20] [22] | Comprehensive sanitation protocols; employee hygiene training; environmental monitoring; product testing [22]. |

| Allergenic | Unintended transfer of allergenic ingredients (e.g., peanuts, milk) [22] | Segregation of processing environments and utensils; proper sanitization between production runs [22]. |

Experimental Protocol: Hyperspectral Imaging for Surface Cleanliness Monitoring

This protocol is adapted from a study conducted in a real-life hospital environment to detect organic dirt and biological contamination on touch surfaces [21].

Objective

To utilize hyperspectral imaging to detect visible and invisible stains on touch surfaces, correlating findings with culturable bacteria and ATP counts.

Materials and Equipment

- Hyperspectral imaging system (e.g., AutoDet) operating in the visible light spectrum (e.g., 420–720 nm) [21].

- Sterile swabs for microbiological sampling.

- ATP monitoring system (e.g., Ultrasnap swabs and luminometer) [21].

- Trypticase Soy Agar plates and selective agar plates for indicator bacteria [21].

- Surfaces for testing (e.g., chair armrests, door handles, lock knobs).

Methodology

- Sampling Site Selection: Identify diverse high-touch and low-touch surfaces in the facility. Sample on days representing a "worst-case scenario" (e.g., before the first cleaning of the week) [21].

- Optical Measurement: Use the hyperspectral imager to scan the target surface. Perform scans on both dirty and subsequently cleaned surfaces for comparison.

- Manual Algorithm: Use threshold levels for intensity and clustering analysis with specific excitation lights (e.g., green, red) and bandpass filters (e.g., λ = 500 nm) [21].

- Automatic Algorithm: Employ machine vision algorithms like k-means clustering on data from the entire visible light spectrum (red, green, blue) and filters from 420 to 720 nm at 20 nm increments [21].

- Microbiological Validation:

- Perform swap wiping on the same surface area.

- Analyze for Total Plate Count (TPC) using Trypticase Soy Agar.

- Test for specific indicator bacteria (e.g., S. aureus, Enterococci, Gram-negatives) using selective agar plates and enrichment steps [21].

- Organic Soil Validation:

- Collect a dry swab sample for ATP measurement.

- Express results in Relative Light Units (RLU) per unit area [21].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the optical imaging results with the microbiological and ATP data. A successful detection is confirmed when the imaging system reveals a stain that correlates with high TPC or ATP counts, even if it was invisible to the naked eye [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item or Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Monitoring System | Provides a rapid estimate of total organic soil (both microbial cells and food/residues) on a surface. It is fast but unspecific for pathogens [21]. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging System | Allows for non-contact, real-time monitoring of surface cleanliness by detecting the unique spectral "fingerprints" of organic and biological contaminants, including those invisible to the eye [21]. |

| Selective Culture Media | Used to isolate and identify specific indicator bacteria (e.g., Enterococcosel Agar for Enterococci, Mannitol Salt Agar for S. aureus), confirming the type of microbial contamination [21]. |

| Validated Cleaning Agents & Disinfectants | Chemical solutions whose efficacy against target microbes has been confirmed for specific soil types, contact times, and concentrations in the given environment [20]. |

| Microbiological Swabs | Tools for aseptically collecting samples from surfaces for subsequent cultivation or molecular analysis, enabling the quantification and identification of viable microbes [21]. |

Contamination Spread and Control Workflow

Cross-Contamination Control Strategy

Advanced Techniques and Standards for Contamination Detection and Monitoring

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How Can I Improve the Sensitivity of My LC-MS/MS Method?

Answer: Sensitivity in LC-MS/MS is a function of the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). Improvements can be made by boosting the analyte signal and by reducing background noise and contaminants. Key strategies involve optimizing the mass spectrometer's source parameters, carefully selecting mobile phases and additives, and employing rigorous sample preparation to minimize matrix effects [23].

Critical MS Source Parameters for ESI Optimization: The following parameters should be optimized for your specific analyte, mobile phase, and flow rate [23].

| Parameter | Influence on Sensitivity | Optimization Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Capillary Voltage | Maintains stable spray; affects ionization efficiency [23]. | Set to match analytes, eluent, and flow rate; incorrect settings cause variable ionization and poor precision [23]. |

| Nebulizing Gas Flow & Temperature | Affects droplet size and charge accumulation [23]. | Increase for faster flow rates or highly aqueous mobile phases [23]. |

| Desolvation Gas Flow & Temperature | Critical for producing gas-phase ions [23]. | Increase for effective desolvation; use caution with thermally labile analytes to prevent degradation [23]. |

| Capillary Tip Position | Impacts ion plume density and transmission into the MS [23]. | Place further from orifice at high flow rates; closer at slower flow rates to increase ion plume density [23]. |

FAQ: Why is There High Background Noise or Unidentified Peaks in My Chromatograms?

Answer: High background signals are frequently caused by contaminants introduced from solvents, additives, samples, or the analyst themselves. These contaminants increase baseline noise, can interfere with the detection of target analytes, and cause ion suppression or enhancement, leading to quantitative inaccuracies [24].

Common Contaminant Sources and Solutions:

| Source Category | Examples of Contaminants | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents & Additives | Microbial growth, solvent impurities, leachates from filters, residual detergents [24]. | Use HPLC-MS grade solvents; avoid unnecessary filtering; dedicate solvent bottles; test different additive sources [24]. |

| Samples & Preparation | Keratins (skin, hair), lipids, plasticizers from tubes/vials, sample carryover [24]. | Wear nitrile gloves; use high-quality consumables; employ thorough cleaning protocols [24]. |

| Instrumentation | Compounds from inlet filters/lines, leachates from polymer seals [24]. | Handle solvent lines with care; use instrument-specific components; flush with organic solvent during extended idle periods [24]. |

FAQ: How Can I Better Detect Low-Abundance Compounds or Handle Non-Ideal Peak Shapes?

Answer: Traditional methods relying on intensity thresholds or rigid mathematical peak-shape models often miss low-abundance compounds or those with non-ideal distributions. A modern solution is to use deep learning-based feature detection algorithms, such as SeA-M2Net, which treat feature detection as an image-based object detection task. This method learns the distribution difference between compounds and noise directly from 2D pseudo-color images of the LC-MS data, allowing it to detect low-abundance and overlapping compounds with high robustness without pre-defined shape assumptions [25].

Experimental Protocol for Deep Learning Feature Detection (SeA-M2Net):

- Data Transformation: Convert raw LC-MS data into a 2D data matrix based on retention time (RT) and mass-to-charge (m/z) dimensions [25].

- Image Generation: Generate a 2D pseudo-color image from the data matrix, where the color intensity represents the abundance of the ions. This integrates visual features like LC elution, charge state, and isotope distribution [25].

- Model Application: Process the image using the pre-trained SeA-M2Net deep convolutional neural network. The network uses a deep multilevel and multiscale structure to estimate the probability of a compound's presence [25].

- Output: The algorithm provides probability outputs (compound vs. noise) and precise locations (m/z, RT, intensity) for all candidate compounds detected in the data [25].

Deep Learning Feature Detection Workflow

Advanced Methodologies

Sum of MRM (SMRM) for Large Biomolecule Quantification

Challenge: Large biomolecules (e.g., proteins, peptides) exist in multiple charged forms in ESI, distributing the total analyte signal across several ion peaks. Selecting a single precursor ion for traditional Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) reduces signal intensity and can compromise sensitivity [26].

Solution: The Sum of MRM (SMRM) approach sums the intensities of MRM transitions from multiple precursor charge states of the same molecule. This boosts the detection signal and expands the dynamic range while maintaining analytical specificity [26].

Experimental Protocol for SMRM:

- Infusion Analysis: Directly infuse the large molecule standard into the mass spectrometer to acquire a full scan mass spectrum [26].

- Identify Charge States: Identify the 3-5 most abundant precursor charge states from the mass spectrum [26].

- Select Product Ions: For each precursor charge state, select 1-3 of the most intense and specific product ions generated via Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID) [26].

- Method Setup: Program the LC-MS/MS method to include all selected precursor ion → product ion transitions for the target analyte.

- Data Processing: Sum the peak areas or heights of all these MRM transitions to generate a combined chromatographic peak for quantification [26].

Validated Method for Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Quantification

The following table summarizes a validated LC-MS/MS method for the gut-derived metabolite TMAO, demonstrating key principles of a sensitive and specific assay [27].

| Method Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Analyte | Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) |

| Matrix | Human Blood Plasma |

| Sample Prep | Simple protein precipitation with a non-deuterated internal standard [27]. |

| LC-MS System | Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer |

| Quantification | Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) of 0.25 µM [27]. |

| Validation | Per EMA/FDA guidelines; intra- and inter-assay precision and trueness within limits [27]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol) are essential to minimize chemical background noise and prevent ion suppression [24] [23]. |

| LC-MS Grade Additives | High-quality acids (e.g., formic acid) and buffers (e.g., ammonium acetate) free of polymeric contaminants are critical for stable ionization and consistent performance [24]. |

| Nitrile Gloves | Worn during all handling steps to prevent contamination of samples, solvents, and surfaces with keratins, lipids, and other biomolecules from the skin [24]. |

| High-Quality Consumables | Use vials, pipette tips, and solid-phase extraction (SPE) plates from reputable manufacturers to minimize leachables like plasticizers and polyethylene glycols (PEG) [23]. |

| Dedicated Glassware | Use solvent bottles dedicated to specific instruments and solvents. Avoid washing with detergent to prevent introducing residual surfactants [24]. |

Contamination Sources and Effects

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Issue 1: High Background Fluorescence / Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Q1: What causes uniformly high background fluorescence across all my bead sets, including negative controls?

- A: This is a classic sign of non-specific binding or contamination. Common causes include:

- Insufficient Blocking: The blocking buffer is inadequate or the incubation time was too short, leaving reactive sites on the bead surface.

- Contaminated Buffers or Reagents: Bacterial or particulate contamination in assay buffers can bind dyes non-specifically.

- Improper Wash Steps: Incomplete washing leaves unbound fluorescent detection antibody in the solution.

- Carryover Contamination: Contamination from previous runs or from improperly cleaned labware.

- A: This is a classic sign of non-specific binding or contamination. Common causes include:

Q2: My signal-to-noise ratio is poor for a specific analyte, while others are fine. What should I investigate?

- A: This points to an issue specific to that analyte's immunocomplex.

- Antibody Cross-Reactivity: The capture or detection antibody for that analyte may be cross-reacting with another protein or component in the sample matrix.

- Matrix Interference: Components in the sample (e.g., lipids, heterophilic antibodies, biotin) are interfering with the specific binding for that analyte.

- Degraded Reagents: The specific capture beads or detection antibody for that analyte may have degraded or been compromised.

- A: This points to an issue specific to that analyte's immunocomplex.

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Decontamination and Optimization

Objective: To identify and eliminate the source of high background fluorescence.

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Buffer Screening | Prepare fresh assay buffer and blocking buffer from new stock solutions. Filter all buffers through a 0.22 µm filter. | Eliminates contamination from old or particulate-laden buffers. |

| 2 | Alternative Blocking | Test a different, more robust blocking agent (e.g., 1% BSA + 5% Normal Serum from the host species of the detection antibody). | Saturates non-specific binding sites more effectively. |

| 3 | Increased Wash Stringency | Increase the number of wash cycles from 3 to 5. Add a mild detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20) to the wash buffer. | Removes loosely bound proteins and reduces non-specific interactions. |

| 4 | Sample Pre-Clearance | Pre-incubate the sample with plain magnetic beads (no antibody) or a commercial heterophilic blocking reagent. | Removes components that bind non-specifically to the bead matrix or assay antibodies. |

Issue 2: Low Signal Intensity / Poor Assay Sensitivity

Q3: My positive controls are showing very low signal, indicating low assay sensitivity. What are the primary culprits?

- A: This indicates a failure in the formation of the detection immunocomplex.

- Antibody Titer: The concentration of the detection antibody is too low.

- Reaction Kinetics: The incubation time for the sample or detection antibody is insufficient for optimal binding.

- Fluorophore Degradation: The fluorescent dye conjugated to the detection antibody has been degraded by exposure to light or repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Instrument Calibration: The flow-based detector (e.g., Luminex scanner) is out of calibration.

- A: This indicates a failure in the formation of the detection immunocomplex.

Q4: The signal is low only for my high-plex panel, but single-plex assays work well. Why?

- A: This suggests "bead-bead" interference or antibody cross-talk in a multiplexed setting.

- Antibody Cross-Linking: Antibodies from different bead sets may be interacting with each other, forming large aggregates that quench signal or are lost during washing.

- Spectral Overlap: In highly multiplexed panels, the fluorescence emission spectra of different dyes may overlap, requiring compensation that can diminish perceived signal.

- A: This suggests "bead-bead" interference or antibody cross-talk in a multiplexed setting.

Experimental Protocol: Signal Amplification and Verification

Objective: To diagnose and correct causes of low signal intensity.

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antibody Titration | Perform a checkerboard titration of the detection antibody against a fixed concentration of the analyte to find the optimal concentration. | Identifies the ideal antibody concentration for maximum signal without increasing background. |

| 2 | Incubation Kinetics | Increase the incubation time for the sample and detection antibody steps (e.g., from 1 hour to 2 hours at room temperature). | Allows more time for the binding equilibrium to be reached. |

| 3 | Fluorophore Integrity Check | Run the detection antibody alone on the instrument to verify its fluorescence intensity has not dropped compared to a new aliquot. | Confirms the fluorescent conjugate is still viable. |

| 4 | Bead Count Verification | Ensure a sufficient number of beads (e.g., >50 per region) are being acquired for analysis. Low bead counts can lead to unreliable and apparently low signals. | Validates the fundamental input for the assay. |

Issue 3: Poor Reproducibility and High Inter-Assay Variability

Q5: My replicate samples within the same plate show high variability (%CV > 20%). What steps can I take?

- A: This is often related to inconsistent liquid handling or reagent preparation.

- Pipetting Error: Manual pipetting of small volumes is a major source of error.

- Incomplete Resuspension: Magnetic beads settle quickly. Inconsistent vortexing or mixing leads to uneven bead distribution across wells.

- Edge Effects: Evaporation in outer wells of the microplate during incubations can alter reagent concentrations.

- A: This is often related to inconsistent liquid handling or reagent preparation.

Q6: The same sample gives different results when run on different days. How can I stabilize my assay?

- A: This inter-assay variability points to environmental or reagent batch issues.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Assay performance is sensitive to room temperature changes.

- Reagent Aliquot Variability: Using new aliquots of critical reagents (especially detection antibody) that have different storage histories.

- Operator Technique: Differences in technique between users or by the same user over time.

- A: This inter-assay variability points to environmental or reagent batch issues.

Experimental Protocol: Standardization for Reproducibility

Objective: To minimize technical variability within and between experiments.

| Step | Procedure | Purpose | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Automate Liquid Handling | Use an automated microplate washer and a repeater pipette for adding reagents. | Minimizes human error in volume dispensing. |

| 2 | Standardize Bead Handling | Implement a fixed vortexing protocol (e.g., 30 seconds at medium speed) before each bead transfer. | Ensures a homogeneous bead suspension for every well. |

| 3 | Control for Evaporation | Use a plate sealer during all incubation steps and run samples in non-edge wells or randomize sample placement. | Prevents concentration changes due to evaporation. |

| 4 | Implement Rigorous QC | Include a standardized QC sample (e.g., a pool of known positives) in every assay run. Track its results over time using a Levey-Jennings chart. | Allows for monitoring of inter-assay performance and early detection of drift. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: FCMIA Workflow

Diagram 2: FCMIA Signal Generation

Diagram 3: Contamination Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| MagPlex / Magnetic Microspheres | Polystyrene beads impregnated with a precise ratio of two fluorescent dyes, giving each bead set a unique spectral signature (region) for multiplexing. The magnetic core enables efficient washing. |

| Carboxylated Bead Surface | Allows for stable, covalent coupling of capture antibodies via carbodiimide chemistry (e.g., EDC/Sulfo-NHS), which is more resistant to displacement and contamination than passive adsorption. |

| Biotinylated Detection Antibodies | Bind specifically to the captured analyte. The biotin moiety provides a universal binding site for the final fluorescent reporter, enabling signal amplification. |

| Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin (SA-PE) | The fluorescent reporter. Streptavidin binds with extremely high affinity to biotin, while Phycoerythrin is a bright, naturally fluorescent protein that provides a strong signal. |

| Phosphonate Buffer (for coupling) | A clean, amine-free buffer used during the antibody-bead coupling step. Contaminating amines (e.g., from Tris buffer) would compete with the antibody and reduce coupling efficiency. |

| Assay Buffer / Blocking Buffer | Typically a protein-based buffer (e.g., containing BSA or serum) used to block non-specific binding sites on the beads and to dilute samples/reagents, preventing high background. |

| Magnetic Plate Washer | Provides consistent and efficient washing of beads in a 96-well microplate format, which is critical for removing unbound material and reducing background signal. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers working to address contamination problems in surface measurements. It provides targeted solutions for common and complex issues encountered during Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFIA) development and optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My LFIA strip shows no control line. What could be the cause? A missing control line indicates an invalid test. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Insufficient Sample Volume: Ensure the absorbent pad has adequate capacity to wick the entire sample volume. Increasing the thickness or length of the absorbent pad can resolve backflow and ensure complete sample migration [28].

- Improper Conjugate Release: Check if the conjugate pad is overly hydrophobic or if the release kinetics are too slow. Pre-treatment of the conjugate pad with surfactants like Tween-20 (<0.05%) or blockers like BSA can improve release [28] [29].

- Inactive Reagents: Verify the functionality of the antibodies used in the control line. The control line typically uses an anti-species antibody to capture labeled antibodies from the conjugate pad. Ensure these reagents have not degraded [30].

Q2: I am observing high background noise on the nitrocellulose membrane. How can I reduce it? High background, or "matrix effect," is often due to non-specific binding.

- Optimize Blocking Agents: Pre-treat the sample pad with blockers such as BSA (1%), casein (0.1–0.5%), or gelatin (0.05–0.1%) to occupy non-specific binding sites on the membrane and pads [28].

- Adjust Surfactant Concentration: Incorporate surfactants like Tween-20 or Triton X-100 (<0.05%) into the sample pad treatment buffer to reduce hydrophobic interactions and improve sample flow [28] [29].

- Purify Biological Reagents: Ensure that your detection and capture antibodies are highly purified to minimize cross-reactivity and non-specific binding [28] [29].

Q3: The test line is too faint for reliable visual interpretation. How can I enhance the signal? A faint test line indicates low sensitivity.

- Optimize Antibody Concentration: The amount of capture antibody spotted on the test line is critical. While typical ranges are 50–500 ng per strip (3–4 mm width), fine-tuning this concentration is necessary. Too much antibody can cause a "hook effect," while too little yields a weak signal [28] [31].

- Check Conjugation Efficiency: The pH of the conjugation buffer must be optimized to ensure complete binding of detector antibodies to colloidal gold nanoparticles. Perform a salt aggregation test to find the pH where nanoparticles remain stable upon salt addition, indicating successful antibody coating [28].

- Review Membrane Characteristics: A membrane with a smaller pore size (e.g., 8-10 µm) increases the wicking time, allowing more time for the antigen-antibody interaction to occur, which can enhance the signal [28] [29].

Q4: My assay for a small molecule contaminant (e.g., a mycotoxin) shows a positive result as the absence of a line. How can I make the result more user-friendly? You are using a competitive format, which is standard for small molecules [29] [32].

- Alternative Competitive Format: Some competitive assays are designed so that the labeled conjugate only binds to the test line in the presence of the analyte. This creates a familiar "line for positive" result. This often requires designing the strip with the analyte (or an analog) immobilized on the test line to capture the labeled antibody only if the sample is negative [29].

- Adopt a SERS-based Readout: Transition from a visual readout to a Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) readout. A SERS-LFIA provides a quantitative, instrumental output that is less ambiguous than interpreting the absence of a line. The intensity of the SERS signal is inversely proportional to the analyte concentration [33] [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common LFIA Issues and Solutions

Table 1: A summary of common problems, their potential causes, and recommended corrective actions.

| Problem | Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Control Line | Control line fails to develop. | Insufficient sample volume; Inactive control line antibody; Conjugate not released. | Check absorbent pad capacity [28]; Validate antibody activity [30]; Optimize conjugate pad treatment [28]. |

| High Background | Entire membrane is discolored, reducing contrast. | Non-specific binding; Sample matrix interference. | Use blockers (BSA, casein) in sample pad [28]; Include surfactants in buffer [29]; Purify antibodies [29]. |

| Faint Test Line | Weak signal, poor sensitivity. | Low antibody affinity; Suboptimal conjugation; Fast flow rate. | Titrate capture antibody concentration [31]; Optimize conjugation pH [28]; Use membrane with smaller pore size [28]. |

| False Positive | Test line appears with negative sample. | Cross-reactivity from impure antibodies. | Use monoclonal antibodies with distinct epitopes; Epitope mapping for capture/detector antibodies [28]. |

| Slow Flow Rate | Sample migrates too slowly. | Membrane with too small pore size; High viscosity sample. | Select membrane with larger pore size or faster capillary flow time [31]; Dilute or pre-treat sample to reduce viscosity [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of LFIA Components

This protocol provides a methodology for selecting and optimizing the core physical components of an LFIA strip [31].

Optimize the Nitrocellulose Membrane:

- Objective: Select a membrane that provides the best compromise between flow rate and sensitivity.

- Method: Test different membranes (e.g., Whatman FF80HP, FF120HP, FF170HP) with varying capillary flow rates (e.g., 60-100 s/4cm, 90-150 s/4cm, 140-200 s/4cm). Spray a visible protein (e.g., BSA) onto each membrane and assess the line continuity and sharpness. Apply your sample-conjugate mixture and evaluate the test line intensity. Slower flow rates (higher wicking time) generally enhance sensitivity by allowing more interaction time [28] [31].

Optimize the Absorbent Pad:

- Objective: Ensure complete sample wicking and prevent backflow.

- Method: Assemble strips with the optimized membrane and different absorbent pads (e.g., Whatman CF5, CF6, CF7). Measure the time taken for the sample front to travel the entire strip length. Select the pad that allows complete and consistent flow without backflow [31].

Optimize the Conjugate Pad:

- Objective: Ensure efficient release of the labeled conjugate.

- Method: Test different conjugate pad materials (e.g., Fusion 5, Standard 17, Standard 14) on the assembled strip. Assess which pad provides the strongest test line signal with the lowest background, indicating good release kinetics and low non-specific binding [31].

Optimize the Sample Pad:

- Objective: Ensure uniform sample application and effective filtration.

- Method: Compare different sample pads (e.g., Whatman CF1, CF3) for their ability to draw the sample consistently into the strip and filter out particulates if using complex samples like whole blood [31].

Titrate Capture Antibody:

- Objective: Determine the optimal amount of antibody for the test line.

- Method: Immobilize different concentrations of the capture antibody (e.g., 0.5, 1, and 2 µg per strip) onto the optimized membrane. Run positive and negative samples. Select the lowest concentration that yields a strong positive signal with a clean background [31].

Protocol 2: Conjugation of Antibodies to Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

This is a critical step for preparing the detector reagent [28].

- Prepare Colloidal Gold: Synthesize 20-40 nm colloidal gold nanoparticles using the trisodium citrate reduction method (Turkevich-Frens method). The size can be customized by altering the citrate concentration [28] [32].

- pH Optimization: Adjust the pH of the colloidal gold solution using 0.1-0.2 M K₂CO₃. The optimal pH is typically slightly above the isoelectric point of the antibody. Determine this by adding 2 M NaCl to gold-antibody mixtures at different pHs; the optimum is the highest pH that prevents aggregation (no color change from red to blue) [28].

- Conjugation: Add the purified antibody to the pH-adjusted colloidal gold solution under constant stirring. The typical antibody concentration ranges from 2 to 20 µg per mL of gold sol.

- Stabilization: After 15-30 minutes, add a stabilizing agent (e.g., 1% BSA) to block any remaining reactive surfaces on the nanoparticles.

- Purification: Centrifuge the conjugate to remove unbound antibodies and re-suspend in a storage buffer containing sucrose, BSA, and surfactants.

- Application: The final conjugate is dispensed onto the optimized conjugate pad and dried, ready for strip assembly [28].

LFIA Workflow and Signal Generation

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of an LFIA, from sample application to result interpretation, which is fundamental for troubleshooting.

Diagram 1: Lateral Flow Immunoassay Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and their functions in LFIA development for contamination analysis.

| Item | Function in the Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrocellulose Membrane | The porous matrix where capture antibodies are immobilized and the test/control lines form [28] [29]. | Pore size (1-20 µm) dictates flow rate and sensitivity. Smaller pores increase interaction time [28]. |

| Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles | The most common visual label, conjugated to detector antibodies. Produces a red color upon accumulation [28] [32]. | 20-40 nm particles offer a good balance of color intensity and stability. Conjugation is pH-sensitive [28]. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Highly specific capture and detection reagents that bind to a single epitope on the target analyte [29] [30]. | Essential for specificity. For sandwich assays, ensure capture and detector antibodies bind distinct, non-competing epitopes [28]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein) | Proteins used to block non-specific binding sites on the membrane and pads, reducing background noise [28] [29]. | Concentration must be optimized (e.g., BSA 1%, Casein 0.1-0.5%) to prevent signal suppression [28]. |

| Surfactants (Tween-20) | Added to buffers to modify surface tension, ensuring uniform sample flow and aiding conjugate release from the pad [28] [29]. | Used at low concentrations (<0.05%). Critical for controlling wicking rates and preventing non-specific binding [28]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting USP Chapter <800> Implementation

Problem: Inconsistent Pressure Differentials in Containment Areas

- Symptom: Unable to maintain the required negative pressure of 0.01 to 0.03 inches of water column relative to adjacent areas [35].

- Potential Cause: Airflow imbalances, room door left open, or leaks in the ventilation system.

- Solution:

- Verify that all doors to the buffer room and ante-room are closed properly.

- Conduct a smoke test to visualize airflow and identify leaks.

- Rebalance the HVAC system to ensure proper air supply and exhaust.

- Check the integrity of room seals around pipes, conduits, and ceiling panels [35].

Problem: CSTD Leakage During Administration

- Symptom: Visible liquid or vapor escape when using a Closed-System Transfer Device (CSTD).

- Potential Cause: Incompatible components, improper connection technique, or a defective device.

- Solution:

- Confirm that all CSTD components are from the same manufacturer and are designed to work together.

- Retrain personnel on the correct technique for making and breaking connections.

- Perform a pressure decay test or similar validation check on the CSTD before use.

- Replace any device that fails validation or shows signs of damage [35].

Troubleshooting SEMI Protocol Implementation

Problem: Intermittent SECS/GEM Communication Failure

- Symptom: Host system randomly loses connection to the manufacturing equipment.

- Potential Cause: Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attack sending a "separate" request, network instability, or incorrect HSMS (High-Speed SECS Message Services) parameters.

- Solution:

- Inspect network architecture for unauthorized devices and implement strict access control lists (ACLs).

- Use a network monitoring tool to detect anomalous "separate" requests.

- Verify and match the HSMS communication parameters (e.g., T3, T5, T6, T7 timeouts) between the host and equipment [36].

- Utilize solutions that provide continuous traffic monitoring and anomaly detection [36].

Problem: SECS/GEM Interface Becomes Unresponsive

- Symptom: Equipment data collection stops; the interface does not respond to commands.

- Potential Cause: Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack from a high volume of messages, or a system resource leak in the interface software.

- Solution:

- Deploy an Intrusion Prevention System (IPS) with rate-limiting capabilities to filter excessive SECS/GEM traffic.

- Restart the interface service or application to clear resource leaks.

- Analyze communication logs to identify the source of the message flood.

- Implement granular security controls to filter commands based on operational context [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of USP Chapter <800>? A1: USP <800> provides standards for the safe handling of hazardous drugs (HDs) to protect healthcare personnel, patients, and the environment from exposure risks. It covers the entire lifecycle of an HD, from receipt and storage to preparation, administration, and waste disposal [37] [35].

Q2: Which drugs are considered "hazardous" under USP <800>? A2: A drug is considered hazardous if it exhibits one or more of these characteristics: carcinogenicity, teratogenicity or developmental toxicity, reproductive toxicity, organ toxicity at low doses, genotoxicity, or has a structure and toxicity profile similar to existing hazardous drugs. The primary reference list is the NIOSH List of Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare Settings [37].