A Comprehensive Guide to Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) Surface Analysis in Materials and Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a detailed exploration of the Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) experimental procedure, a powerful surface analysis technique crucial for characterizing the elemental composition and chemistry of material surfaces.

A Comprehensive Guide to Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) Surface Analysis in Materials and Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of the Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) experimental procedure, a powerful surface analysis technique crucial for characterizing the elemental composition and chemistry of material surfaces. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content covers foundational principles, from the Auger effect and instrumentation to advanced methodological applications like depth profiling and chemical state analysis. It further addresses practical challenges, including sample preparation for insulating materials and data interpretation, and offers a comparative analysis with techniques like XPS. The guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to effectively implement AES in R&D for optimizing materials, including those used in pharmaceutical development and nanodevices.

Understanding the Core Principles of Auger Electron Spectroscopy

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides information about the chemical composition of the outermost material layers of a solid surface [1] [2]. The technique relies on the Auger effect, a physical phenomenon discovered independently by Lise Meitner and Pierre Auger in the 1920s [1]. AES has evolved into a fundamental characterization method in materials science, offering exceptional spatial resolution (<1µm), surface sensitivity (typically 0.5-5 nm), and excellent detection capabilities for light elements [2] [3] [4].

The surface sensitivity of AES stems from the low kinetic energy (50 eV to 3 keV) of the emitted Auger electrons, which limits their escape depth to within a few nanometers of the target surface due to short mean free path in solids [1]. This extreme surface sensitivity requires AES instruments to operate under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions (<1×10⁻⁹ Torr) to prevent electron scattering off residual gas atoms and minimize surface contamination [1] [2] [4]. Modern AES systems, often called Scanning Auger Microscopes (SAMs), can produce high-resolution, spatially resolved chemical images by stepping a focused electron beam across a sample surface [1] [3].

Fundamental Principles of the Auger Process

The Auger Effect and Electron Transitions

The Auger process involves a series of internal relaxation events in an excited atom, resulting in the emission of an energetic electron known as an Auger electron [1] [5]. This process can be described in three distinct steps:

- Excitation: A high-energy electron beam (typically 3-25 keV) ejects a core-shell electron from a sample atom, creating a vacancy and forming an excited state ion [5] [3] [4].

- Relaxation: An electron from a higher-energy outer shell fills the core vacancy, releasing energy equal to the difference in orbital energies [1] [5].

- Auger Emission: The transition energy is transferred to another outer-shell electron, which is ejected from the atom if the transferred energy exceeds its binding energy [1] [5].

The kinetic energy of the emitted Auger electron is characteristic of the element from which it was emitted and can be approximated by the equation:

[E{ABC} = EA(Z) - 0.5[EB(Z) + EB(Z+1)] - 0.5[EC(Z) + EC(Z+1)]]

where (EA(Z)) represents the core-level energy of the initial vacancy, and (EB(Z)), (EB(Z+1)), (EC(Z)), and (E_C(Z+1)) represent the energy levels of the participating electrons [1].

Auger Transition Notation

Auger transitions are denoted using X-ray notation levels corresponding to the atomic orbitals involved in the process [1] [5]. The notation follows the pattern WXY, where:

- W indicates the energy level where the initial core hole was created

- X represents the energy level of the electron that fills the initial hole

- Y signifies the energy level of the ejected Auger electron [5]

For example, a KLL transition involves an initial vacancy in the K-shell, filled by an electron from the L-shell, with subsequent ejection of another electron from the L-shell [1]. The specific transitions available depend on the element and its electronic structure, with different transition series dominating for various atomic number ranges [5].

Auger Transition Probability and Yield

Competition Between Auger and Radiative Processes

During the de-excitation process of an excited atom, two competing pathways exist for relaxation: Auger transition (non-radiative) and X-ray fluorescence (radiative) [1] [5]. The total transition rate (ω) is the sum of non-radiative (Auger) and radiative (X-ray fluorescence) processes, with the Auger yield (ωₐ) defined as:

[ωA = 1 - ωX = 1 - \frac{WX}{WX + W_A}]

where (WX) represents the radiative transition rate and (WA) represents the Auger transition rate [1]. The probability of each process depends on the atomic number, with Auger transitions dominating for lighter elements and X-ray fluorescence becoming more significant for heavier elements [5].

Atomic Number Dependence

The relationship between Auger transition probability and atomic number follows a well-defined trend that explains the exceptional sensitivity of AES for light elements [5]. For elements with atomic numbers less than 19, the Auger transition probability exceeds 90%, making it the dominant de-excitation pathway [5]. This probability remains high until atomic number 33, where Auger and fluorescence probabilities become approximately equal [5].

Table 1: Auger Transition Probability vs. Atomic Number

| Atomic Number Range | Dominant Transition Series | Auger Transition Probability | Fluorescence Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z < 15 | KLL | >90% | <10% |

| 16 ≤ Z ≤ 41 | LMM | High (decreasing with Z) | Low (increasing with Z) |

| Z > 41 | MNN and higher | Approximately 50% at Z=33 | Approximately 50% at Z=33 |

This atomic number dependence directly correlates with Auger electron yield, which remains high for light elements where Auger transitions are favored over X-ray emission [5]. The high transition probability for light elements means that when these atoms are excited, they are far more likely to emit an Auger electron than an X-ray photon, resulting in stronger AES signals and superior detection sensitivity [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Auger Yield

Factors Influencing Auger Electron Intensity

The intensity of Auger electrons forms the basis for quantitative elemental analysis in AES and depends on several key factors [5]:

- Elemental concentration: The number of target atoms per unit volume

- Ionization cross-section (σ): The probability of core-level ionization by incident electrons

- Auger yield (ωₐ): The probability of Auger emission versus X-ray fluorescence

- Escape depth (λ): The distance Auger electrons can travel without energy loss

- Analyzer transmission (T): The efficiency of the electron energy analyzer

The total Auger electron yield can be expressed as:

[Y(t) = Nx × δt × σ(E,t)[1 - ωX]\exp\left(-t\cos\frac{θ}{λ}\right) × I(t) × T × \frac{d(Ω)}{4π}]

where (N_x) represents the number of x atoms per volume, λ the electron escape depth, θ the analyzer angle, T the transmission of the analyzer, I(t) the electron excitation flux at depth t, dΩ the solid angle, and δt the thickness of the layer being probed [1].

Light Element Sensitivity

The high Auger yield for light elements directly translates to enhanced detection sensitivity in this atomic number range [5]. Detection limits for most elements in AES range from 0.01 to 0.1 atomic% (100-1000 ppm), with variations depending on the specific element and experimental conditions [2] [3] [4]. The exceptional sensitivity for light elements arises from their high Auger transition probabilities, which can exceed 90% for elements with Z < 19 [5].

Table 2: AES Detection Capabilities for Selected Light Elements

| Element | Atomic Number | Dominant Transition | Approximate Detection Limit (atomic%) | Auger Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | 3 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

| Beryllium | 4 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

| Boron | 5 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

| Carbon | 6 | KLL | 0.05-0.1 | >90% |

| Nitrogen | 7 | KLL | 0.05-0.1 | >90% |

| Oxygen | 8 | KLL | 0.05-0.1 | >90% |

| Sodium | 11 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

| Magnesium | 12 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

| Aluminum | 13 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

| Silicon | 14 | KLL | 0.1 | >90% |

Experimental Protocols for AES Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful AES analysis, particularly when investigating light elements:

- Sample Size Requirements: Samples should not exceed 18 mm × 12 mm × 12 mm to fit standard AES holders [2] [4]. Oversized samples may require cutting or sectioning.

- Electrical Conductivity: Samples must be electrically conductive or properly grounded to prevent charging effects [2] [4]. Non-conductive samples may require coating with a thin conductive layer (typically carbon), though this may interfere with light element detection.

- Surface Cleaning: Remove surface contaminants through solvent cleaning, plasma cleaning, or in-situ ion sputtering to ensure accurate surface composition analysis [5] [4].

- Handling Procedures: Use powder-free gloves and clean tools to prevent contamination, especially for light elements like carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen that are common in contaminants [4].

- Vacuum Compatibility: Ensure samples are compatible with ultra-high vacuum conditions and do not outgas significantly, which could compromise the vacuum integrity [2] [4].

Instrumentation and Operating Conditions

AES instrumentation typically includes several key components that must be optimized for light element analysis [1] [5]:

- Electron Gun: Tungsten filament or field emission sources providing primary electron beams of 3-25 keV energy [3] [4]. Field emission guns offer superior spatial resolution (<10 nm) for high-resolution mapping [3].

- Electron Energy Analyzer: Typically a Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CMA) or hemispherical analyzer for energy discrimination of emitted electrons [1].

- Ion Gun: Argon ion source (500 eV to 5 keV) for sample cleaning and depth profiling through controlled sputtering [5] [3].

- Detection System: Electron multiplier or channel electron multiplier for signal detection [1].

- UHV System: Maintaining pressure <1×10⁻⁹ Torr to minimize electron scattering and surface contamination [1] [2].

For optimal light element analysis, specific operating conditions should be employed:

- Primary Beam Energy: 3-10 keV for optimal excitation of light element K-shell electrons [3] [4].

- Beam Current: 1-100 nA, adjusted to maximize signal while minimizing sample damage [3].

- Analysis Area: <1 µm diameter for high spatial resolution analysis [2] [4].

- Spectral Acquisition: Often performed in derivative mode (dN(E)/dE) to enhance visibility of small Auger peaks against the background [1].

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis Protocols

Qualitative Analysis Protocol:

- Survey Spectrum Acquisition: Collect spectrum from 0-2000 eV to identify all detectable elements [5] [4].

- Peak Identification: Compare peak positions with standard elemental spectra, focusing on characteristic Auger transitions for light elements (KLL series) [5].

- Chemical State Assessment: Examine peak shapes and energy shifts for chemical state information, particularly for elements like Al, Mg, and Si [2] [4].

- Spatial Distribution: Perform element mapping or line scans to determine lateral distribution of identified elements [3] [4].

Semi-Quantitative Analysis Protocol:

- Peak Intensity Measurement: Measure peak-to-peak heights in derivative spectra or integrate areas under peaks in direct spectra [5] [4].

- Sensitivity Factors: Apply relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) to convert intensity to atomic concentration using the formula:

[Cx = \frac{Ix/Sx}{\sum(Ii/S_i)}]

where (Cx) is the atomic concentration of element x, (Ix) is the measured intensity, and (S_x) is the relative sensitivity factor [5].

- Matrix Effects Correction: Account for matrix-dependent effects such as electron backscattering and mean free path variations [1] [5].

- Standards Comparison: When available, use standard samples with similar composition for improved quantification accuracy [5].

Depth Profiling Protocol

Depth profiling through sputtering enables determination of elemental distribution as a function of depth [5] [3]:

- Sputtering Conditions Optimization: Select appropriate Ar⁺ ion energy (500 eV-5 keV) and current based on desired depth resolution and sputtering rate [5] [3].

- Analysis-Sputtering Cycles: Alternate between AES analysis and ion sputtering, or use continuous sputtering with simultaneous analysis [5].

- Depth Calibration: Convert sputtering time to depth using calibrated sputtering rates or measure crater depth with profilometry after analysis [3] [4].

- Data Interpretation: Account for preferential sputtering effects and ion-induced compositional changes when interpreting depth profiles [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for AES Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Considerations for Light Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Adhesives | Sample mounting and electrical grounding | Carbon tape, silver paste, copper tape | Carbon tape preferred for carbon analysis; silver paste may interfere with silver detection |

| Reference Standards | Quantification and instrument calibration | Pure elemental standards, well-characterized compounds | Certified standards with similar matrix to unknowns improve quantification accuracy |

| Sputtering Gas | Depth profiling and surface cleaning | High-purity argon (99.999+%) | Higher purity reduces incorporation of impurities during sputtering |

| Sample Stubs | Sample mounting and positioning | Standard sizes (e.g., 12mm, 18mm diameter) | Material composition (typically stainless steel) should not interfere with elements of interest |

| Charge Neutralization | Analysis of insulating samples | Low-energy electron flood gun, argon ion beam | Essential for insulating samples; may reduce sensitivity for some light elements |

| Cryogenic Cooling | Analysis of volatile samples | Liquid nitrogen cooling stages | Prevents desorption of volatile species under UHV conditions |

| Fracture Stage | In-situ exposure of interfaces | Custom stages for fracturing samples in UHV | Preserves clean interfaces for analysis of grain boundaries and interphases |

Applications Highlighting Light Element Sensitivity

The exceptional sensitivity of AES for light elements enables numerous applications across materials science and engineering:

- Microelectronic Failure Analysis: Identification of carbonaceous contamination on integrated circuits and measurement of thin oxide layers on semiconductor devices [2] [4]. AES can detect sub-monolayer contamination that affects device performance.

- Corrosion Science: Analysis of passive oxide film composition and thickness on metals and alloys, particularly beneficial for studying early-stage oxidation involving light elements [3] [4].

- Thin Film Technology: Characterization of thin film composition and interface chemistry, including measurement of carbon and oxygen at interfaces [3] [4].

- Polymer Surface Modification: Analysis of surface functionalization and treatment effects on polymer surfaces, where light elements (C, O, N) dominate the composition [3].

- Nanoparticle Characterization: Determination of surface composition and coating chemistry of nanoparticles, where the high spatial resolution of AES enables analysis of individual particles [2] [3].

The combination of excellent light element sensitivity, high spatial resolution, and surface specificity makes AES particularly valuable for these applications where traditional techniques like EDX struggle with light element detection and surface sensitivity.

Auger Electron Spectroscopy excels in the analysis of light elements due to the fundamental physics of the Auger process, specifically the high transition probability for elements with low atomic numbers. The dominance of Auger transitions over X-ray fluorescence for elements with Z < 19 results in superior detection sensitivity, with detection limits typically ranging from 0.01 to 0.1 atomic% for light elements [2] [5] [4]. This intrinsic advantage, combined with excellent spatial resolution and extreme surface sensitivity, establishes AES as a powerful technique for surface analysis of light elements across diverse applications in materials science, microelectronics, and interfacial engineering. Proper experimental design, including optimized sample preparation, instrument parameters, and data interpretation protocols, ensures researchers can fully leverage the exceptional capabilities of AES for light element characterization.

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that utilizes a high-energy electron beam to excite atoms within the top 3-10 nm of a material [6]. The resulting relaxation process emits "Auger" electrons with kinetic energies characteristic of elements present at the sample surface, creating a unique spectral "fingerprint" for elemental identification [6] [7]. This application note details the methodologies for interpreting AES spectra, focusing on the use of characteristic energies for qualitative elemental analysis within the broader context of AES surface analysis experimental procedure research. For researchers in drug development and materials science, AES provides crucial surface composition data with high spatial resolution (≥10 nm) and sensitivity to all elements except hydrogen and helium [6].

The fundamental principle of AES analysis involves measuring the kinetic energy of emitted Auger electrons, which is characteristic of the elements from which they originated and their electronic environment [7]. Unlike techniques that rely on photon excitation, AES uses an electron beam (typically 3-25 keV) to eject core electrons, initiating a cascade process where higher-energy electrons fill the vacancies, simultaneously ejecting tertiary (Auger) electrons [6] [7]. Since the kinetic energy of these Auger electrons depends on the element-specific binding energies of the orbitals involved, each element produces a distinctive spectrum that serves as the basis for qualitative identification.

Fundamental Principles of AES

The Auger Process

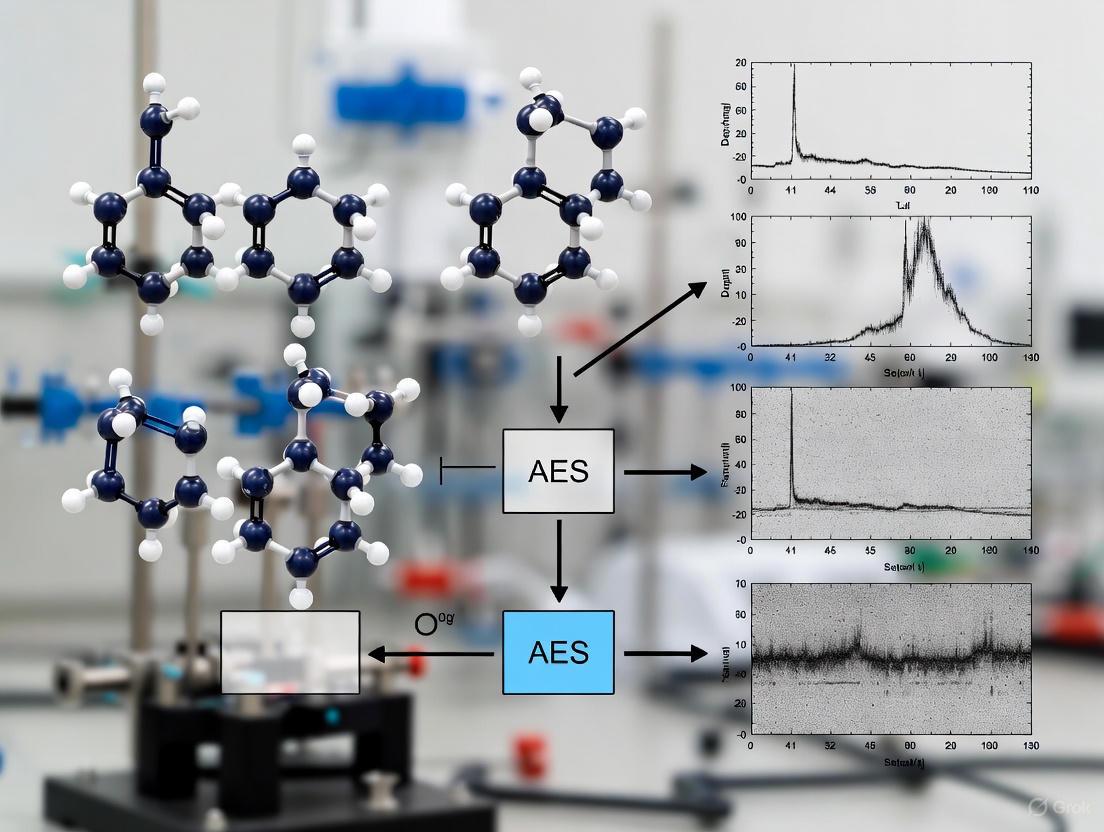

The Auger emission process involves a precise three-step sequence occurring within the atom. Figure 1 illustrates this cascade of events, which begins when an incident high-energy electron from the primary beam ejects a core-level electron (e.g., from the K-shell), creating a vacancy and leaving the atom in a highly excited, unstable state [7]. Subsequently, an electron from a higher-energy level (e.g., the L₁-shell) relaxes and fills the core-level vacancy. The energy released during this relaxation process is transferred to a third electron (e.g., from the L₂,₃-shell), which is then ejected from the atom as an Auger electron [7]. This ejected electron is the analytical signal measured in AES.

The kinetic energy of the emitted Auger electron is approximately given by Eₖ = Eₖ - Eₗ₁ - Eₗ₂,₃, where E represents the binding energy of the respective electron shells. This energy is characteristic of the specific atomic energy levels involved and is largely independent of the incident electron beam energy, making it a reliable fingerprint for elemental identification [7]. The entire process is labeled according to the electron shells involved in the transition. For example, a KLL transition involves an initial vacancy in the K-shell, an L-shell electron filling that vacancy, and the ejection of another L-shell electron.

Figure 1: The Three-Stage Auger Electron Emission Process

Spectral Data Presentation

AES spectra can be presented in two primary forms: direct (N(E) vs. E) and differentiated (dN(E)/dE vs. E) [7]. The direct spectrum plots the number of electrons (N) detected at each energy level (E), revealing the elemental composition through peak positions. However, the differentiated spectrum, which mathematically enhances small changes in the slope of the direct spectrum, is often preferred for qualitative analysis because it better resolves overlapping peaks and enhances visibility of small peaks against the background [7]. This differentiation is particularly valuable for identifying elements present in low concentrations or distinguishing between elements with closely spaced Auger transitions.

Characteristic AES Energies for Elemental Identification

Elemental Fingerprint Library

Qualitative elemental analysis in AES relies on comparing the kinetic energies of peaks in an unknown spectrum with reference data from known elements. Each element exhibits characteristic Auger transitions at specific energy ranges, creating a unique spectral fingerprint. Table 1 presents characteristic AES transition energies for selected elements, demonstrating the elemental-specific nature of these measurements [7].

Table 1: Characteristic AES Transitions and Kinetic Energies for Selected Elements

| Atomic Number | Element | AES Transition | Kinetic Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Li | KLL | 43 |

| 4 | Be | KLL | 104 |

| 5 | B | KLL | 179 |

| 6 | C | KLL | 272 |

| 7 | N | KLL | 379 |

| 8 | O | KLL | 508 |

| 9 | F | KLL | 647 |

| 11 | Na | KLL | 990 |

| 12 | Mg | KLL | 1186 |

| 13 | Al | LMM | 68 |

| 14 | Si | LMM | 92 |

| 15 | P | LMM | 120 |

| 16 | S | LMM | 152 |

| 17 | Cl | LMM | 181 |

| 19 | K | KLL | 252 |

| 20 | Ca | LMM | 291 |

| 21 | Sc | LMM | 340 |

| 22 | Ti | LMM | 418 |

| 23 | V | LMM | 473 |

| 24 | Cr | LMM | 529 |

| 25 | Mn | LMM | 589 |

| 26 | Fe | LMM | 703 |

The pattern of transitions follows predictable trends across the periodic table. Lighter elements (atomic number < 14) typically exhibit KLL transitions, while medium and heavier elements show LMM and MNN transitions respectively [7]. The specific kinetic energies increase with atomic number within transition series, providing a systematic framework for element identification. Modern AES instruments include comprehensive digital libraries containing characteristic spectra for most elements, enabling automated peak identification, though researcher verification remains crucial for accurate interpretation, particularly for complex samples with multiple overlapping peaks.

Chemical State Information

While AES is primarily used for elemental identification rather than detailed chemical state analysis (unlike XPS), subtle shifts in Auger peak positions and shapes can provide some chemical information [6] [7]. Changes in the oxidation state of an element can cause measurable shifts in Auger peak energies due to alterations in the binding energies of the electrons involved in the Auger process. For example, the energy required to remove an electron from Fe³⁺ is greater than from Fe⁰, resulting in a lower kinetic energy for the Fe³⁺ Auger peak compared to the metallic iron peak [7]. These chemical shifts, while typically smaller than in XPS, can still provide valuable insights into surface chemistry, oxidation states, and chemical environment when interpreted carefully by experienced analysts.

Experimental Protocols for AES Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful AES analysis. The following protocol ensures optimal results:

- Sample Cleaning: Remove surface contaminants using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol, acetone) with lint-free wipes or through plasma cleaning. Avoid touching the analysis area with bare hands.

- Mounting: Secure samples onto appropriate holders using conductive tape or clips. Ensure electrical contact for conducting samples to prevent charging.

- Non-Conductive Samples: For insulating materials, apply a thin carbon tape path to the analysis area or use a miniature electron flood gun if available.

- Size Considerations: Ensure samples conform to instrument stage specifications, typically ≤1 cm thick for standard systems. EAG laboratories report capability to analyze wafers up to 300mm [6].

- Vacuum Compatibility: Verify samples are compatible with high vacuum conditions (typically 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹⁰ Torr) and will not outgas significantly.

- Reference Materials: Include well-characterized standard materials when performing quantitative analysis to verify instrument calibration.

Instrument Calibration and Data Acquisition

Figure 2 illustrates the complete workflow for AES spectral acquisition and interpretation, from sample loading through elemental identification. The following protocol ensures proper instrument setup:

- Energy Calibration: Calibrate the electron energy analyzer using standard reference materials with known Auger peaks, such as pure silver (Ag MNN peak at 356 eV) or copper (Cu LMM peak at 920 eV).

- Electron Beam Parameters: Set primary beam energy typically between 3-25 keV based on sample properties and analysis requirements [6]. Higher beam energies provide greater excitation but may increase sample damage risk.

- Beam Current Optimization: Adjust beam current (typically 0.1-100 nA) to balance signal intensity with spatial resolution and sample damage considerations.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect survey spectra from 0-2000 eV to identify all detectable elements. Use step sizes of 0.5-1 eV for survey scans and 0.1-0.2 eV for high-resolution regional scans.

- Differentiated Spectra: Acquire spectra in differentiated mode (dN(E)/dE) for enhanced peak visibility, particularly for minor elements [7].

- Spatial Mapping: For heterogeneous samples, acquire elemental maps by rastering the electron beam across regions of interest and recording AES signal intensity at characteristic energies.

Figure 2: AES Spectral Acquisition and Interpretation Workflow

Peak Identification Methodology

The following step-by-step protocol ensures systematic identification of elements in AES spectra:

- Major Peak Identification: Identify the most intense peaks in the spectrum and match them with characteristic transitions of likely elements based on sample composition.

- Secondary Peak Verification: Confirm identifications by locating less intense Auger transitions for the same elements, following expected transition series (KLL, LMM, MNN).

- Spectral Library Comparison: Compare unknown spectra with reference spectra from standardized databases, ensuring acquisition parameters match as closely as possible.

- Peak Overlap Resolution: For overlapping peaks, use high-resolution scanning or mathematical deconvolution to separate contributions from different elements.

- Chemical State Assessment: Note peak position shifts that may indicate chemical state differences, comparing with reference data for known compounds when available.

- Quantitative Analysis: Apply sensitivity factors to determine atomic concentrations for identified elements when quantitative analysis is required.

Advanced Applications and Complementary Techniques

Research Applications

AES provides critical analytical capabilities for diverse research applications, particularly where surface composition and nanoscale features determine material performance:

- Defect and Particle Analysis: Identify sub-µm particles and surface defects to determine contamination sources and investigate failure causes in electronic devices [6]. The high spatial resolution (≥10 nm) enables analysis of features inaccessible to many other techniques.

- Thin Film Characterization: Determine composition and thickness of thin films and multilayer structures, particularly valuable for films too thin for EDS analysis [6].

- Interface Analysis: Investigate interfacial composition and reactions using depth profiling combined with ion sputtering, revealing elemental distributions as a function of depth.

- Corrosion and Oxidation Studies: Analyze surface oxide layers, including determination of oxide layer thickness on electro-polished medical devices [6].

- Grain Boundary Analysis: Identify grain boundary segregation and contamination in metal fractures, fatigues, and failures [6].

Complementary Techniques

While AES provides powerful surface analysis capabilities, it is often combined with complementary techniques for comprehensive materials characterization:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): The electron column in AES systems typically provides high-resolution SEM imaging, enabling precise location of analysis features [6].

- Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS): Combined AES-EDS systems provide simultaneous surface (AES) and bulk (EDS) compositional information [8].

- Focused Ion Beam (FIB): Integrated FIB systems enable in situ cross-sectioning for subsurface AES analysis of buried interfaces and defects [8].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): While both are surface-sensitive, XPS provides more detailed chemical state information, complementing AES elemental analysis [6].

Technical Specifications and Limitations

AES Capabilities and Constraints

Table 2 summarizes the key technical specifications and limitations of AES for research applications. Understanding these parameters is essential for appropriate experimental design and interpretation of results.

Table 2: AES Technical Specifications and Analytical Capabilities

| Parameter | Specification | Notes/Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Elements Detected | Li to U | Cannot detect H or He [6] |

| Detection Limits | 0.1-1 at% (sub-monolayer) | Varies by element and matrix [6] |

| Lateral Resolution | ≥10 nm | High spatial resolution for small features [6] |

| Analysis Depth | 3-10 nm | Extreme surface sensitivity [6] |

| Depth Profiling | 2-20 nm resolution | With sputtering capability [6] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Semi-quantitative | Requires standards for improved accuracy [6] |

| Chemical State Information | Limited | Less detailed than XPS [6] |

| Sample Requirements | Vacuum compatible | No outgassing, typically solid conductors [6] |

| Mapping Capability | Yes | Elemental distribution imaging [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for AES Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Conductive Adhesive Tapes | Mounting samples to holders while maintaining electrical conductivity |

| Reference Standard Materials | Instrument calibration and quantitative analysis verification (e.g., pure Cu, Ag, Si) |

| Sputter Ion Source (Ar⁺) | Surface cleaning and depth profiling through controlled material removal |

| Electron Flood Gun | Charge compensation for analysis of insulating samples |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning Solvents | Sample surface preparation (high-purity acetone, methanol, isopropanol) |

| Specialized Sample Holders | Accommodation of various sample geometries and sizes |

| Focused Ion Beam (FIB) System | In situ cross-sectioning for subsurface analysis [8] |

| Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer | Complementary bulk elemental analysis [8] |

Auger Electron Spectroscopy remains an indispensable technique for surface elemental analysis, offering unique capabilities for nanoscale characterization with high spatial resolution and surface sensitivity. The interpretation of AES spectra through characteristic kinetic energies provides reliable elemental identification when performed following systematic protocols. For researchers in drug development, materials science, and semiconductor technology, AES delivers crucial information about surface composition, contamination, and thin film structures that directly impact material performance and reliability. As AES continues to evolve with advancements in automation, spatial resolution, and integration with complementary techniques like FIB and EDS, its applications in both fundamental research and industrial problem-solving continue to expand, solidifying its position as a cornerstone of modern surface analysis.

Executing AES Analysis: From Sample to Data in the Lab

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful, surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides quantitative elemental information from the top 3-10 nm of solid materials [9] [8]. It is based on the analysis of low-energy electrons emitted during the Auger process, which follows the ionization of an atom by a high-energy electron beam. Due to the limited escape depth of these electrons, AES is exceptionally well-suited for investigating surface composition, thin films, and nanoscale features, making it indispensable in materials science, semiconductor development, and corrosion studies [10] [9]. This protocol details the complete experimental workflow within the context of advanced surface analysis research.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

The AES effect occurs when a high-energy electron beam (typically 2-10 keV) ejects a core-level electron from a sample atom [10] [9]. An electron from a higher energy level then fills this vacancy, and the excess energy is released by emitting a second electron—the Auger electron. The kinetic energy of this Auger electron is characteristic of the emitting element, providing a fingerprint for elemental identification [9].

A modern AES instrument, essentially an advanced Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), integrates several key components to perform this analysis [9]:

- Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) System: Operates at pressures <10⁻⁹ torr. This is critical to prevent scattering of Auger electrons by gas molecules and to protect the clean sample surface from contamination [9].

- Electron Source: A field emission electron gun that produces a highly focused beam, enabling spatial resolution down to ~8-25 nm [10] [9].

- Electron Energy Analyzer: A Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CMA) is commonly used to measure the kinetic energy of emitted electrons with high collection efficiency and energy resolution [9].

- Ion Sputter Gun: A focused beam of argon ions (Ar⁺) used for cleaning the sample surface and for depth profiling by sequentially removing atomic layers [9].

- Secondary Detectors: Many systems are equipped with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) and Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) detectors for complementary bulk compositional and crystallographic analysis [9].

Table 1: Core Instrumental Components of an AES System

| Component | Function | Typical Operational Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Gun | Generates the primary excitation beam for sample ionization. | Energy: 2-10 keV; Beam Diameter: > ~25 nm [10] [9] |

| Cylindrical Mirror Analyzer (CMA) | Separates and counts emitted electrons by their kinetic energy. | Varies to achieve desired energy resolution [9]. |

| Ion Sputter Gun | Removes surface contaminants and performs depth profiling. | Ar⁺ ions; sputter rate calibrated with standards (nm/sec) [9]. |

| UHV System | Maintains a contamination-free environment for analysis. | Pressure < 10⁻⁹ torr [9]. |

Experimental Protocols: A Step-by-Step Workflow

Sample Preparation Protocol

Objective: To prepare a sample compatible with UHV and suitable for AES analysis.

- Step 1: Sample Selection and Sizing. Use small, solid samples (a few mm). Flat surfaces are preferred to minimize charging and improve spatial resolution in elemental maps [9].

- Step 2: Cleaning. If possible, clean the sample with solvents (e.g., ethanol, acetone) in an ultrasonic bath to remove organic contaminants. Dry with inert gas.

- Step 3: Mounting. Mount the sample on a suitable holder using conductive adhesives (e.g., colloidal graphite paint) or indium foil to ensure electrical and thermal contact [9].

- Step 4: Handling. Use powder-free gloves and clean tweezers to avoid introducing surface contaminants.

Sample Loading and Vacuum Stabilization Protocol

Objective: To safely introduce the sample into the UHV chamber without compromising the vacuum.

- Step 1: Transfer. Place the mounted sample into the UHV introduction chamber.

- Step 2: Pump-Down. Close the introduction chamber and begin pumping. Gradually pump down from atmospheric pressure to the UHV range (<10⁻⁹ torr). This process may take several hours.

- Step 3: Transfer to Analysis Stage. Once the UHV in the main chamber is stable, transfer the sample from the introduction chamber to the analytical stage.

In-Situ Surface Cleaning Protocol

Objective: To remove native oxide layers and adventitious carbon from the analysis area.

- Step 1: Ion Gun Setup. Align the ion sputter gun with the sample surface. Use a rastered beam over an area larger than the region of interest to ensure uniform cleaning [9].

- Step 2: Sputtering. Sputter the surface with Ar⁺ ions. Typical parameters include an accelerating voltage of 0.5-5 keV and a calibrated sputter rate. The duration depends on the contaminant thickness [9].

- Step 3: Verification. Acquire a wide-scan Auger survey spectrum (see Section 3.4) to confirm the reduction of carbon and oxygen peaks.

Data Acquisition and Analysis Protocols

Protocol 3.4.1: Auger Survey Scan Objective: To identify all elements present on the sample surface (except H and He).

- Setup: Position the electron beam on the region of interest. Set the electron beam energy to 10 keV.

- Analyzer Settings: Configure the CMA for a wide energy range scan (e.g., 0-2000 eV).

- Acquisition: Acquire the spectrum, which plots the differentiated signal (dN(E)/dE) versus electron kinetic energy. Identify elements by the positions of their characteristic Auger peaks [9].

Protocol 3.4.2: High-Resolution Multiplex Scan Objective: To determine the chemical state or obtain more precise elemental quantification.

- Setup: Based on the survey scan, select the specific energy window for a core-level transition of the element of interest (e.g., the Carbon KLL transition around 270 eV).

- Acquisition: Acquire a high-resolution, non-differentiated spectrum over this narrow energy window.

- Analysis: Use peak fitting routines to deconvolute chemical shifts, which can indicate different bonding states [9].

Protocol 3.4.3: AES Elemental Mapping Objective: To visualize the lateral distribution of elements on the surface.

- Setup: Define the analysis area on the SEM image.

- Tuning: Set the CMA to the kinetic energy of the primary Auger peak for the element of interest.

- Rastering: Raster the focused electron beam across the selected area.

- Data Collection: At each pixel, record the intensity of the Auger peak. Construct a 2D map where brightness corresponds to elemental concentration [10] [8].

Protocol 3.4.4: Depth Profiling Objective: To determine the elemental composition as a function of depth.

- Setup: Select a sample area for analysis.

- Cycling: Alternate between two processes:

- Sputter Cycle: Remove a thin layer of material using the Ar⁺ ion gun for a predetermined time.

- Analysis Cycle: Acquire Auger survey spectra or multiplex scans from the newly exposed surface [9].

- Repetition: Repeat this cycle until the desired depth is reached.

- Data Processing: Plot elemental concentrations (from peak-to-peak heights in differentiated spectra) versus sputter time or calibrated depth.

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

AES data is semi-quantitative, and concentrations can be calculated using relative sensitivity factors. The atomic concentration of an element A is given by:

C_A = (I_A / S_A) / Σ(I_n / S_n)

Where I_A is the measured Auger peak intensity for element A, S_A is its relative sensitivity factor, and the sum is over all detected elements n.

Table 2: Key Analytical Capabilities and Performance Metrics of AES

| Analytical Feature | Performance Metric | Notes & Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | ~0.1 at% (for elements Z≥3/Li and heavier) [9]. | Varies by element and matrix. |

| Surface Sensitivity | ~3-10 nm (0.4-10 atomic monolayers) [9] [8]. | Due to the short escape depth of Auger electrons. |

| Lateral Resolution | < 25 nm with field emission source [10] [9]. | Allows for sub-micron mapping of small features. |

| Elements Detected | All except H and He [9]. | Light element analysis is a particular strength. |

| Quantitative Analysis | Semi-quantitative using sensitivity factors [9]. | Can be more accurate with standard samples. |

| Sample Requirements | Solid, UHV-compatible, vacuum-stable. | Volatile or beam-sensitive samples (epoxies, organics) are unsuitable [9]. |

Visualizing the AES Workflow and Process

The Auger Emission Process

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental physical process that generates an Auger electron.

AES Experimental Workflow

This flowchart outlines the end-to-end operational procedure for a standard AES analysis, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for AES Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Conductive Adhesives (e.g., Colloidal Graphite Paint, Silver Paste) | Ensures electrical and thermal contact between the sample and holder, mitigating charging effects on insulating samples [9]. |

| Indium Foil/Substrate | A malleable, conductive mounting medium, especially useful for pressing and securing small or powdered samples [9]. |

| Argon (Ar) Gas | The source gas for the ion sputter gun, used for in-situ surface cleaning and depth profiling [9]. |

| Silicon Wafer Substrates | A clean, flat, and conductive substrate often used for mounting powdered or irregular samples [9]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., oxide-coated metal standards) | Used for calibrating the sputter rate of the ion gun, converting sputter time to accurate depth measurements [9]. |

| Solvents (e.g., High-Purity Isopropanol, Acetone) | For preliminary cleaning of samples to remove gross organic contamination prior to insertion into the UHV chamber. |

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique used for elemental identification and compositional analysis of solid surfaces. Within the broader context of AES surface analysis experimental procedure research, mastering qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis is fundamental. AES excels at providing high-lateral-resolution compositional information, capable of identifying all elements except hydrogen and helium with a sensitivity down to approximately 0.5 atomic percent (at.%) [10] [11]. The core principle of AES involves bombarding a sample surface with a focused beam of high-energy (2-10 kV) electrons. This incident beam causes the emission of "Auger electrons," which possess discrete kinetic energies characteristic of the elements from which they originated [10]. By analyzing the kinetic energies of these electrons, a qualitative identification of the surface elements is achieved. Quantitative and semi-quantitative analysis then builds upon this by interpreting the intensities of the measured Auger signals [11].

A key challenge in AES, particularly when analyzing insulating materials, is the accumulation of surface charge, which can distort results. The severity of this effect is governed by the Total Secondary Electron Yield (TSEY), defined as the ratio of the number of outgoing electrons to the number of incident electrons (σ = Iₒ/Iᵢ) [11]. A stable analysis condition is theoretically achieved when σ = 1, meaning the incident and outgoing electron currents are balanced, thus preventing charge build-up. The ability to control this parameter is critical for obtaining reliable data from non-conductive samples, such as ceramics or polymers, which are increasingly important in various industrial and research fields [11].

Key Analytical Parameters for Quality Assessment

The quality of information obtained from AES, whether qualitative or semi-quantitative, depends on a set of key analytical parameters. Ensuring the reliability of determination results requires the identification and management of factors that could cause measurement deviations [12] [11]. Among these, selectivity and the limits of detection are paramount.

Selectivity refers to the method's ability to accurately identify and quantify a specific element in the presence of other substances within the sample matrix [12] [11]. In AES, while the characteristic Auger peaks allow for identification, overlapping peaks from different elements or matrix effects can complicate this process. Unlike techniques prone to isobaric or polyatomic interferences, AES spectra can be affected by peak shape changes and background contributions, which must be accounted for to ensure accurate qualitative analysis.

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest concentration of an element that can be reliably detected by the technique. For AES, the detection limits are typically in the range of tenths of a weight percent [12]. This makes AES exceptionally powerful for surface analysis but less suited for detecting trace elements at very low concentrations compared to other elemental analysis techniques.

Table 1: Key Parameters Affecting AES Analysis Quality

| Parameter | Impact on Qualitative/Semi-Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|

| Selectivity | Determines the accuracy of element identification in a complex matrix; affected by peak overlap and chemical state shifts [12]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | ~0.5 at.% sensitivity; defines the lowest elemental concentration that can be detected [12] [10]. |

| Spatial Resolution | The size of the smallest feature that can be analyzed; can be as high as ~70 nm for insulating samples and even better for conductors [10] [11]. |

| Surface Charging | Can cause energy shifts, peak broadening, and deformation, severely impacting both identification and quantification, especially on insulators [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Analysis

Obtaining high-quality AES data requires careful experimental procedures. The following protocols outline the critical steps for both qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis, with specific considerations for challenging insulating samples.

Protocol for Qualitative Elemental Identification and Mapping

This protocol is designed for the initial identification of elements present on a sample surface and for visualizing their spatial distribution.

- Sample Preparation (Insulating Samples):

- Charge Compensation Method (Bulk Samples): Metallize the sample surface with a thin, conductive coating (e.g., Au, C). This facilitates surface charge dissipation [11].

- Thin Film Method: Thin the insulating sample to less than 100 nm. Analyze it with a high-energy primary electron beam to penetrate the sample and reduce charge accumulation [11].

- Instrument Setup:

- Mount the sample securely on the holder, ensuring good electrical contact if possible.

- For bulk insulating samples, implement charge compensation by flooding the analysis area with low-energy Ar⁺ ions to neutralize surface charge [11].

- Optimize the primary electron beam parameters. To minimize charging, use a reduced beam current and adjust the beam energy and incident angle to favor a TSEY (σ) value near or above 1 [11].

- Survey Analysis:

- Acquire a wide-energy-range Auger survey spectrum (e.g., 0-1000 eV or higher) from a representative area.

- Identify all elements present by matching the kinetic energies of the major peaks in the spectrum to standard reference databases.

- High-Resolution Mapping:

- Define the elements of interest based on the survey spectrum.

- Select a specific Auger transition peak for each element and set the electron energy analyzer to measure the intensity at that energy.

- Raster the focused electron beam across the region of interest to generate an elemental map, demonstrating the lateral distribution of each element with high resolution (e.g., 70 nm) [11].

Protocol for Semi-Quantitative Analysis

This protocol describes a method for estimating the relative atomic concentrations of elements identified on the surface.

- Peak Acquisition:

- Following qualitative identification, acquire high-resolution, multiplex spectra for the specific Auger peaks of each identified element.

- Ensure the spectral acquisition parameters are consistent across all measurement points.

- Data Processing:

- Measure the peak-to-peak height (or integrated peak area) in the derivative spectrum for each elemental peak.

- This measured intensity (I) for an element 'X' is proportional to its concentration.

- Concentration Calculation:

- Calculate the atomic concentration (Cₓ) of each element using a relative sensitivity factor (RSF) approach. The formula for the semi-quantitative estimate is:

Cₓ = [ (Iₓ / Sₓ) / Σ (Iᵢ / Sᵢ) ] * 100%where:Iₓis the measured peak intensity of element X.Sₓis the relative sensitivity factor for element X.Σ (Iᵢ / Sᵢ)is the sum of the intensity/RSF ratios for all elements detected.

- Use RSFs derived from standard reference materials measured under identical analytical conditions for the most accurate results [11].

- Calculate the atomic concentration (Cₓ) of each element using a relative sensitivity factor (RSF) approach. The formula for the semi-quantitative estimate is:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful AES analysis requires specific materials and standards to ensure accurate and reproducible results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for AES

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Conductive Coatings (Gold, Carbon) | Sputter-coated onto insulating samples to provide a path for charge dissipation during the Charge Compensation Method [11]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., Si₃N₄, Al₂O₃ bulk) | Well-characterized materials used to determine element-specific Relative Sensitivity Factors (RSFs) for accurate semi-quantification [11]. |

| Low-Energy Ar⁺ Ion Gun | Provides a flux of positive ions to neutralize negative charge build-up on the surface of insulating samples during analysis [11]. |

| Focus Ion Beam (FIB) / Ultramicrotome | Equipment used for the precise preparation of ultrathin sample sections (<100 nm) required for the Thin Film Method of analyzing insulators [11]. |

| High-Purity Polishing Materials | Used to prepare a flat, smooth, and uncontaminated surface on solid samples, which is critical for reproducible and quantitative analysis. |

Workflow and Data Analysis Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting a complete AES analysis, from sample preparation through to qualitative and semi-quantitative results.

Comparative Analysis with Other Elemental Techniques

AES is one of several powerful tools for elemental bioimaging and analysis. Its capabilities and limitations become clear when compared to other common techniques. The choice of technique depends on the specific requirements of the analysis, such as the needed spatial resolution, detection limits, and whether the sample is conductive or insulating.

Table 3: Comparison of Elemental Analysis and Imaging Techniques

| Feature | AES | XRF | SEM-EDS | LA-ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Auger Electron Spectroscopy | X-ray Fluorescence | Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray | Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| Spatial Resolution | ~70 nm (for insulators) to ~25 nm [10] [11] | ~0.05-100 µm [12] | ~1 µm [12] | 5-100 µm [12] |

| Detection Limit (LOD) | ~0.5 at.% [10] | mg/kg [12] | Tenths of weight % [12] | µg/kg [12] |

| Quantification | Semi-Quantitative [11] | Yes [12] | Semi-Quantitative [12] | Yes (Fully Quantitative) [12] |

| Sample Destruction | Semi-non-destructive | No | No | Semi-non-destructive [12] |

| Key Advantage | Excellent lateral resolution for surface elemental analysis; depth profiling. | Good for bulk analysis; minimal sample prep. | Widely available; combined with high-resolution imaging. | Excellent sensitivity (low LODs); fully quantitative. |

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides exceptional insights into the elemental composition and chemical environment of material surfaces. Based on the Auger effect, discovered independently by Lise Meitner and Pierre Auger in the 1920s, AES has evolved into an indispensable tool for characterizing the outermost atomic layers (typically 2-5 nm) of solid surfaces [1]. The fundamental Auger process occurs when an electron beam (typically 3-20 keV) strikes a sample, ejecting a core-level electron. This creates an unstable ion that relaxes through a radiationless process where an electron from a higher energy level fills the core hole, simultaneously transferring energy to a third electron (the Auger electron) that is emitted from the atom [1].

The kinetic energy of the emitted Auger electron is characteristic of the specific atomic transition and is approximately given by the relationship: EABC = EA - EB - EC, where EA, EB, and EC represent the binding energies of the atomic levels involved in the transition [1]. This fundamental relationship makes AES highly sensitive to chemical state variations, as changes in the chemical environment alter the effective binding energies of the participating electrons, resulting in measurable shifts in Auger peak positions and changes in lineshapes. Chemical state analysis through AES enables researchers to identify oxidation states, characterize chemical bonding environments, detect surface contaminants, and investigate interfacial reactions in diverse materials systems ranging from catalysts to semiconductors [13] [14].

Theoretical Foundation of AES Chemical Shifts

The Auger Process and Energy Considerations

The Auger effect involves a three-electron process that produces characteristic electrons whose energies are independent of the incident beam energy, making AES particularly valuable for chemical analysis. When an atom is excited by an external mechanism (electron beam, photons, or ions), a core-level electron is removed, creating a hole in an inner orbital. During the subsequent relaxation process, an electron from a higher energy level fills this vacancy, and the transition energy is transferred to a third electron that is emitted from the atom [1]. The kinetic energy of this emitted Auger electron can be calculated using the formula:

Ekin = ECore State - EB - EC'

Where ECore State is the energy of the core level where the initial vacancy was created, EB is the binding energy of the electron that fills the core hole, and EC' is the binding energy of the emitted electron in the presence of the core hole [1]. The presence of the core hole significantly influences the energy levels, making Auger transitions particularly sensitive to the chemical environment.

Chemical Influences on Auger Spectra

Chemical state information in AES is derived primarily from two spectral features: peak energy shifts and lineshape modifications. When an atom undergoes a change in its chemical environment (such as oxidation, formation of compounds, or coordination changes), the electron density distribution around the atom is altered. This affects the binding energies of the electrons involved in Auger transitions, leading to measurable shifts in peak positions [14]. The lineshape changes occur because the valence band density of states, which often participates in Auger transitions, is directly modified by chemical bonding.

For example, when analyzing semiconductor surfaces like GaP and Si, researchers have observed significant differences in the Auger signals between atomically clean surfaces and those exposed to the atmosphere. The clean surfaces exhibit characteristic Auger transitions, while oxidized surfaces show modified peak positions and intensities due to the formation of oxide species [14]. These chemical effects are particularly pronounced in Auger transitions involving valence electrons (such as LVV transitions), making them more sensitive to chemical state variations than core-core-core transitions.

Table 1: Types of Chemical Information Obtainable from AES Spectra

| Spectral Feature | Chemical Information | Example Transitions |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Position Shift | Oxidation state, electronegativity effects | Si LVV, P LVV, O KLL |

| Lineshape Modification | Chemical bonding, valence band structure | CVV transitions in metals and semiconductors |

| Peak Intensity Changes | Compound formation, overlayer growth | Elemental ratios during thin film growth |

| Peak Width Changes | Lifetime effects, multiple environments | Transition metals in different coordination spheres |

Quantitative Data and Reference Values

The interpretation of chemical state information in AES requires reference to established data from well-characterized standards. The following tables summarize key quantitative information essential for chemical state analysis.

Table 2: Characteristic AES Peak Shifts for Common Elements

| Element | Chemical State | Transition | Peak Energy (eV) | Shift (eV) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon (Si) | Elemental Si | LVV | 92 | Reference | Clean semiconductor surfaces [14] |

| SiO₂ | LVV | 78 | -14 | Oxide layer characterization [14] | |

| Phosphorus (P) | Elemental P | LVV | 120 | Reference | GaP surfaces [14] |

| P₂O₅ | LVV | ~115 | ~-5 | Surface oxidation [14] | |

| Carbon (C) | Graphite | KLL | 272 | Reference | Reference carbon |

| Carbide | KLL | ~262 | ~-10 | Metal carbide identification | |

| Hydrocarbon | KLL | ~268 | ~-4 | Contamination layers | |

| Oxygen (O) | Metal oxides | KLL | 503-510 | Variable | Oxide characterization [14] |

Table 3: Experimental Parameters Affecting AES Spectral Resolution

| Parameter | Effect on Chemical Shift Resolution | Optimal Values for Chemical State Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Beam Energy | Ionization cross-section, damage potential | 3-10 keV (balance between signal and damage) [14] |

| Beam Current | Signal-to-noise ratio, spatial resolution | 10-100 nA (higher for better SNR) |

| Modulation Voltage | Peak resolution, derivative spectrum quality | 2-5 V (lower for better peak separation) [1] |

| Scan Rate | Peak position accuracy, signal quality | Slow scans (0.1-0.5 eV/s) for high resolution [15] |

| Time Constant | Signal filtering, distortion minimization | 0.1-0.3 s (matched to scan rate) [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Chemical State Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocol

Objective: To prepare contamination-free surfaces suitable for reproducible AES chemical state analysis.

Materials Required:

- UHV-compatible sample holder

- Metal tweezers (stainless steel or tantalum)

- Solvent cleaning supplies (isopropanol, acetone)

- Glove box or transfer system for air-sensitive samples

Procedure:

- Initial Cleaning: Begin by ultrasonically cleaning samples in sequential solvent baths (acetone followed by isopropanol) for 5 minutes each to remove gross organic contamination.

- UHV Transfer: Mount the sample on a UHV-compatible holder using minimal-contact techniques to prevent surface damage.

- In-situ Cleaning: Inside the UHV system, employ one or more of the following cleaning methods based on sample compatibility:

- Ar⁺ Ion Sputtering: Use 0.5-4 keV Ar⁺ ions at current densities of 1-10 μA/cm² for 1-30 minutes, depending on contamination thickness. Follow with mild annealing if necessary to restore surface order.

- Annealing: Resistively heat the sample to temperatures appropriate for the material (typically 400-800°C for metals, lower for semiconductors) to desorb surface contaminants.

- In-situ Cleaving: For brittle materials like semiconductors, use a precision cleaving system to create fresh, atomically clean surfaces [14].

- Cleanliness Verification: Acquire a survey AES spectrum (0-1000 eV) to confirm the absence of carbon, oxygen, and other contaminants before proceeding with chemical state analysis.

AES Data Acquisition for Chemical Shift Analysis

Objective: To acquire high-quality AES spectra suitable for chemical state identification with minimal beam-induced damage.

Materials Required:

- AES spectrometer with cylindrical mirror analyzer (CMA) or hemispherical analyzer

- Electron gun with adjustable energy and current

- Sample holder with precise positioning capabilities

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration:

- Energy calibrate the analyzer using standard reference materials (Au, Ag, or Cu).

- Verify energy resolution using a known sharp peak (e.g., Cu MVV at 61 eV) with full width at half maximum (FWHM) typically <0.5 eV.

- Preliminary Survey Scan:

- Acquire a broad survey spectrum (0-1000 eV) using: Primary energy: 10 keV, Beam current: 100 nA, Modulation voltage: 5 Vₚₚ, Scan rate: 5 eV/s.

- Identify all elements present and their approximate concentrations.

- High-Resolution Regional Scans:

- For each element of interest, acquire high-resolution regional scans around the relevant Auger transitions:

- Set primary energy to 3-5 keV to minimize damage while maintaining sufficient signal.

- Reduce beam current to 10-20 nA for beam-sensitive materials.

- Use lower modulation voltage (1-2 Vₚₚ) for direct spectrum acquisition.

- Implement slow scan rates (0.1-0.5 eV/s) with multiple scans averaged for improved signal-to-noise.

- For each element of interest, acquire high-resolution regional scans around the relevant Auger transitions:

- Derivative Spectrum Acquisition (optional):

- For enhanced peak visibility, acquire derivative spectra by applying a small AC modulation (1-2 Vₚₚ) to the analyzer and using lock-in amplification.

- Note that derivative spectra can complicate quantitative lineshape analysis but are excellent for peak identification.

- Damage Minimization:

- Continuously monitor peak shapes and positions during acquisition to detect beam-induced damage.

- For sensitive materials, use rastered beam acquisition or frequently move to fresh sample areas.

Chemical Shift Measurement and Interpretation Protocol

Objective: To accurately measure and interpret chemical shifts in AES spectra for chemical state identification.

Materials Required:

- Reference materials with known chemical states

- Spectral analysis software with peak fitting capabilities

- Database of standard AES spectra

Procedure:

- Energy Referencing:

- Reference all spectra to a well-established internal standard (e.g., adventitious carbon C KLL at 272 eV) or external standard.

- Apply consistent energy calibration across all samples in a study.

- Background Subtraction:

- Apply appropriate background subtraction (typically Shirley or Tougaard background) to remove inelastic scattering contributions.

- Use consistent parameters for all comparable samples.

- Peak Position Determination:

- For direct spectra: Identify peak positions as the maximum intensity point after background subtraction.

- For derivative spectra: Identify peak positions as the most negative excursion points.

- Use peak fitting with appropriate functions (Gaussian, Lorentzian, or mixed) for overlapping features.

- Chemical Shift Calculation:

- Calculate chemical shifts relative to the elemental reference state: ΔE = Esample - Eelemental

- Compare measured shifts with database values (see Table 2) for chemical state identification.

- Lineshape Analysis:

- Analyze the complete lineshape of Auger transitions, particularly for CVV transitions that reflect the local density of states.

- Compare with theoretical calculations or reference spectra for definitive chemical state assignment.

- Multivariate Analysis (for complex systems):

- Employ factor analysis or principal component analysis for samples with multiple chemical states.

- Use linear least-squares fitting with reference spectra for quantitative chemical state determination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for AES Chemical State Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function in AES Analysis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Energy calibration, spectral comparison | Au, Ag, Cu for energy calibration; pure elements and well-characterized compounds for chemical shift references |

| Ar⁺ Ion Sputter Source | Surface cleaning, depth profiling | Essential for removing native oxides and contamination; use low energies (0.5-2 keV) for minimal damage |

| UHV-Compatible Sample Holders | Sample mounting and positioning | Materials: Ta, Mo, or stainless steel; must maintain electrical contact for conducting samples |

| In-situ Cleaving System | Creating atomically clean surfaces | Critical for standard preparation; especially important for semiconductor and ceramic materials [14] |

| Electron Gun | Primary excitation source | Field emission guns provide superior spatial resolution; LaB₆ guns offer higher current for better SNR |

| Hemispherical Analyzer | High-energy resolution analysis | Preferred for chemical state analysis due to superior energy resolution compared to CMA |

| Charge Neutralization System | Analysis of insulating samples | Low-energy electron flood gun or Ar⁺ beam for charge compensation on insulators |

Applications in Materials Research

Catalyst Surface Analysis

AES has proven particularly valuable in catalysis research, where surface composition directly influences activity and selectivity. When studying catalyst materials such as supported metal nanoparticles, bimetallic systems, and metal oxides, AES enables researchers to correlate catalytic performance with surface chemical states [13]. For example, the oxidation state of metal nanoparticles (e.g., Pt⁰ vs. Pt²⁺) significantly impacts catalytic activity in oxidation reactions, and these states can be distinguished through careful analysis of AES peak positions and lineshapes. AES also facilitates the investigation of promoter elements and their chemical states, providing insights into their mode of action in complex catalyst formulations.

In catalyst deactivation studies, AES can identify carbonaceous deposits (coking) and distinguish between different types of carbon species (graphitic vs. amorphous carbon) through analysis of the C KLL lineshape. Similarly, poison accumulation (e.g., S, Cl) can be detected and quantified, guiding regeneration protocol development. The extreme surface sensitivity of AES makes it ideal for investigating the initial stages of catalyst preparation, such as the decomposition of precursor compounds on support materials, enabling rational catalyst design through understanding of fundamental surface processes [13].

Semiconductor Surface Characterization

Semiconductor surfaces and interfaces represent another major application area for AES chemical state analysis. As demonstrated in studies of GaP and Si surfaces, AES can effectively characterize native oxides, contamination layers, and intentional surface modifications [14]. When semiconductor surfaces are exposed to the atmosphere, they rapidly develop contamination layers containing carbonaceous species and oxides, which can be quantitatively analyzed using AES. The chemical state information is crucial for understanding electronic properties, as different oxidation states (e.g., SiO vs. SiO₂ on silicon) significantly impact interface states and device performance.

AES studies have revealed that electron irradiation during analysis can itself induce chemical changes on certain semiconductor surfaces. For instance, GaP surfaces show much greater susceptibility to electron beam effects compared to Si, with significant carbon and oxygen species deposition observed after just 3 hours of irradiation [14]. This highlights the importance of controlling acquisition parameters during AES analysis of beam-sensitive materials. For semiconductor device fabrication, AES chemical state analysis provides critical information about cleaning efficiency, interface reactions, and thin film properties, enabling process optimization and yield improvement.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: AES Chemical State Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the complete experimental procedure for chemical state analysis using AES, highlighting critical acquisition parameters that influence spectral quality and chemical shift resolution.

Chemical state analysis through Auger Electron Spectroscopy provides a powerful approach for investigating the surface chemistry of materials with exceptional sensitivity to the local chemical environment. By carefully analyzing peak shifts and lineshape modifications in AES spectra, researchers can extract detailed information about oxidation states, chemical bonding, and surface reactions that directly influence material properties and performance. The protocols and reference data presented in this application note establish a framework for reproducible, high-quality AES chemical state analysis across diverse materials systems. When implemented with appropriate controls and validation, AES chemical shift analysis serves as an indispensable tool in surface science, enabling advances in catalyst design, semiconductor technology, and functional materials development.

Overcoming Common AES Challenges and Optimizing Data Quality

Auger Electron Spectroscopy (AES) is a powerful surface-sensitive analytical technique that provides information about the chemical composition of the outermost layers of a material, typically the top 2-3 nm [4] [5]. The principal advantages of AES include excellent spatial resolution (< 1 µm), high surface sensitivity (~20 Å), and superior detection of light elements, with detection limits for most elements ranging from about 0.01 to 0.1% (atomic) [4]. However, the technique faces significant limitations when analyzing insulating materials due to sample charging effects that can compromise data quality and integrity.

The fundamental operating principle of AES involves using a primary electron beam to excite the sample surface. When an inner-shell electron is ejected from a sample atom through interaction with a primary electron, an electron from an outer shell fills the vacancy. The energy released from this transition leads to the emission of an Auger electron, whose energy is characteristic of the element from which it was emitted [4] [16]. AES requires an ultrahigh vacuum environment to minimize the interception of Auger electrons by gas molecules between the sample and detector [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Limitations of AES Analysis

| Parameter | Typical Specification | Impact on Insulating Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Depth | ~2-3 nm [4] | Unaffected by sample conductivity |

| Spatial Resolution | < 1 µm [4] | Degraded by charging effects |

| Detection Limits | 0.01-0.1% (atomic) [4] | Compromised by unstable surface potential |

| Sample Environment | Ultrahigh vacuum (<1×10⁻⁹ Torr) [4] | Applicable to all sample types |

| Primary Probe | Electron beam (typically 2-25 keV) [17] | Primary source of charging |

The Sample Charging Phenomenon in Insulating Materials

The charging of insulators under electron beam irradiation presents a fundamental challenge for AES analysis. This phenomenon occurs due to the imbalance between incident electron beam current and emitted secondary electron emission current. When the total secondary electron emission yield (TSEEY, denoted as σ) is unity, an exact charge balance occurs. However, if σ is greater than unity, the surface charges positively, while σ less than unity leads to negative charging [17].

Charging manifests as both a near-instantaneous effect governed by secondary electron emission and a time-dependent effect governed by implanted charge and dynamically changing secondary electron emission. For insulating materials, the incident electron beam implants negative charge in a layer approximately 1 μm deep, while surface secondary emission may lead to either positive or negative surface charge depending on the experimental conditions [17].

The materials exhibiting the most significant charging effects, in order of increasing severity, are typically: MgO, Al₂O₃, Si₃N₄, NaCl, and SiO₂. However, this order depends significantly on the precise form and purity of the specific materials being analyzed [17]. Excessive charging can completely deflect the primary electron beam, preventing analysis entirely, or cause significant peak shifts and distortions that render quantitative analysis impossible.

Diagram 1: Charge formation mechanism and impacts on AES data.

Charge Control Strategies and Methodologies

Primary Charge Mitigation Techniques

Several practical strategies have been developed to mitigate charging effects during AES analysis of insulating materials. These approaches can be implemented individually or in combination, depending on the severity of charging and the specific instrument configuration available.

Table 2: Primary Charge Control Strategies for AES Analysis of Insulators

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Implementation Parameters | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Beam Defocusing | Reduces current density, minimizing localized charge buildup | Increase beam diameter by 2-10x; raster over larger area [17] | High for moderate charging |

| Beam Energy Reduction | Shifts operation to E | Reduce beam energy to <1.5 keV; optimize using EC⁰·⁶ cos θ = constant [17] | Material-dependent |

| Sample Tilting | Increases effective σ, promoting positive surface charge | Increase angle of incidence to 30-60° from normal [17] | High for materials with high σm |

| Reduced Exposure Time | Limits total charge implantation | Work quickly; use pulsed beam techniques [17] | Essential for all analyses |

| Conductive Coating | Provides path for charge dissipation | Apply 2-10 nm carbon or metal films [16] | Very high, but alters surface |

The most effective strategy often involves a combination of these approaches. The relationship between beam energy (EC) and angle of incidence (θ) follows approximately EC⁰·⁶ cos θ = constant for low-dose studies. The constant value ranges from above 4.0 for MgO to 1.85 for SiO₂, defining a zone of low charging in EC,θ space [17]. For high-dose studies, this zone of low charging contracts, with the constant value reducing to below 0.88 of the low-dose value for SiO₂ and below 0.55 for Si₃N₄ [17].

Advanced Charge Control Methodologies

For materials exhibiting severe charging, more advanced methodologies may be required. These include the use of low-energy flood guns (electrons of ~400 eV) to stabilize surface potential, flooding the surface with low-energy He⁺ or Ar⁺ ions, exposure to UV radiation, or controlled heating of the sample [17]. Gaseous environments at specific pressures (e.g., 1×10⁻⁴ Torr Ar) can also effectively discharge samples, though this may lead to contamination for certain materials [17].

Diagram 2: Decision workflow for charge mitigation strategies.

Experimental Protocols for Insulating Samples

Pre-analysis Assessment Protocol

Material Characterization: Determine sample composition, purity, and physical form through prior characterization techniques. Document any known electrical properties or previous analysis history.

Conductivity Screening: Perform preliminary conductivity assessment using a multimeter or by observing secondary electron imaging behavior in the AES instrument.

Morphology Evaluation: Examine surface topography using secondary electron imaging at low beam currents (≤1 nA) and energies (3-5 keV) to identify optimal analysis regions.

Charge Propensity Prediction: Calculate expected charging behavior using the relationship EC⁰·⁶ cos θ = K, where K is material-specific (K ≈ 4.0 for MgO, 1.85 for SiO₂) [17].

Optimized AES Acquisition Protocol for Insulators

Initial Conditions: Begin analysis with reduced beam energy (2-3 keV), defocused beam (≥1 µm diameter), and sample tilted to 45-60° from normal incidence.

Progressive Optimization:

- Acquire initial survey scan and assess peak shape and stability

- If charging observed, further reduce beam energy in 0.5 keV increments

- Increase tilt angle incrementally up to 60° maximum

- Defocus beam to spread charge over larger area

- Reduce beam current to minimum acceptable for adequate signal-to-noise

Time-management: Limit exposure of single area to essential acquisition time only. For multiplex scans or depth profiling, monitor for time-dependent charging effects.

Validation: Compare acquired spectra with standard reference materials when possible. Verify that peak positions remain stable during acquisition.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Charging Artifacts in AES Analysis